Abstract

Dorsal thalamic nuclei have been categorized as either “first order” nuclei that gate the transfer of relatively unaltered signals from the periphery to the cortex, or “higher order” nuclei that transfer signals from one cortical area to another. To classify the tectorecipient lateral posterior (LPN), we examined the synaptic organization of tracer-labeled cortical and tectal terminals, and terminals labeled with antibodies against the type 1 and type 2 vesicular glutamate transporters (vGLUT1 and vGLUT2) within the caudal/lateral LPN of the rat. Within this zone, we found that all tracer-labeled cortical terminals, as well as vGLUT1 antibody-labeled terminals, are small profiles with round vesicles (RS profiles) that innervate small caliber dendrites. Tracer-labeled tecto-LPN terminals, as well as vGLUT2 antibody-labeled terminals, were medium-sized profiles with round vesicles (RM profiles). Tecto-LPN terminals were significantly larger than cortico-LPN terminals, and contacted significantly larger dendrites. These results indicate that within the tectorecipient zone of the rat LPN, cortical terminals are located distal to tectal terminals, and that vGLUT1 and vGLUT2 antibodies may be used as markers for cortical and tectal terminals respectively. Finally, comparisons of the synaptic patterns formed by tracer-labeled terminals with those of vGLUT antibody-labeled terminals suggest that individual LPN neurons receive input from multiple cortical and tectal axons. We suggest that the tectorecipient LPN constitutes a third category of thalamic nucleus (“second order”) that integrates convergent tectal and cortical inputs. This organization may function to signal the movement of novel or threatening objects moving across the visual field.

Keywords: tectothalamic, corticothalamic, vesicular glutamate transporter, superior colliculus, GABA

Introduction

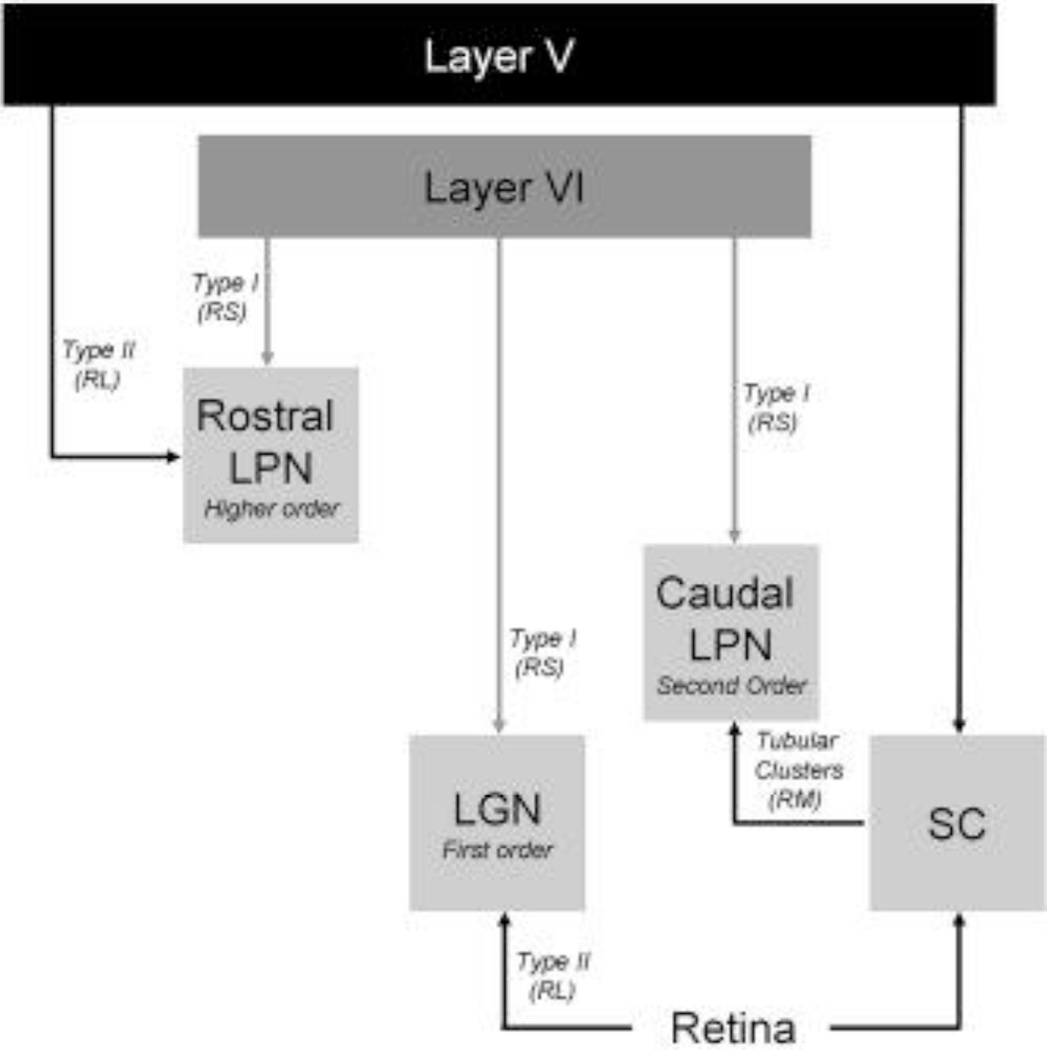

Recent studies suggest that nuclei of the dorsal thalamus fall into two general categories. First order nuclei, such as the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN), receive ascending sensory input (e.g. from the retina) that drives neuronal response properties, and feedback input from cortical layer VI that modulates these responses (Guillery, 1995; Sherman and Guillery, 1998). In contrast, higher order nuclei receive little ascending sensory input, and are innervated by cortical cells located in both layers V and VI. Anatomical and physiological studies suggest that within higher order nuclei, the function of the ascending sensory input is supplanted by inputs from cortical layer V (Ogren and Hendrickson, 1979; Vidnyanszky et al., 1996; Feig and Harting, 1998; Bartlett et al., 2000; Li et al., 2003a; Li et al., 2003c; Reichova and Sherman, 2004; Baldauf et al., 2005), and that this cortically driven circuitry may be involved in corticocortical communication rather than the relay of ascending sensory signals (Guillery, 1995; Sherman and Guillery, 2002).

Previous studies indicate that the rostral regions of the rat lateral posterior nucleus (LPN) can be considered higher order. This region receives few ascending inputs and is innervated by two types of cortical terminals that resemble either corticogeniculate terminals (type I), or retinogeniculate terminals (type II) (Bourassa and Deschenes, 1995; Li et al., 2003a). In addition, stimulation of cortical inputs to the rostral LPN elicits two types of excitatory postsynaptic responses (EPSPs). Type I responses facilitate with increasing stimulation frequency (Li et al., 2003b), similar to corticogeniculate EPSPs (Lindstrom and Wrobel, 1990; Turner and Salt, 1998; von Krosigk et al., 1999; Granseth et al., 2002), while type II responses depress with increasing stimulation frequency (Li et al., 2003a), similar to retinogeniculate responses (Turner and Salt, 1998; Chen et al., 2002; Chen and Regehr, 2003). Thus, it appears that the rostral LPN should be considered higher order in that the morphology and physiology of synaptic terminals that originate from cortical layer 5 are quite similar to the ascending sensory inputs of first order nuclei.

However, a third category may be necessary to describe the organization of thalamic regions that receive input from the superior colliculus (SC). Recent studies of the primate mediodorsal nucleus indicate that inputs from the SC can significantly impact thalamic and cortical activity patterns (Wurtz and Sommer, 2004) yet, where examined, tectothalamic terminals form unique synaptic arrangements that do not fall into driver or modulator categories (Mathers, 1971; Partlow et al., 1977; Crain and Hall, 1980; Ling et al., 1997; Kelly et al., 2003; Chomsung et al., 2008). Furthermore, we previously found that the membrane properties and responses to stimulation of cortical fibers recorded within the caudal LPN of the rat are distinct from those recorded in the rostral LPN (Li et al., 2003b; Li et al., 2003c).

The unique response properties we recorded in the caudal LPN were likely located in the tectorecipient zone of the LPN (Mason and Groos, 1981; Mooney et al., 1984; Takahashi, 1985; Hilbig et al., 2000). However, it is difficult to accurately relate our physiological findings to LPN input zones because precise histological markers for LPN subdivisions are lacking. In addition, the synaptic organization of tecto-LP terminals and their relation to cortico-LP terminals has not previously been examined. Therefore, in preparation for further in vitro studies of the rat LPN, we have characterized the tectorecipient zone of the rat LPN using histochemical markers, tract tracing and electron microscopy.

Methods

A total of 19 hooded rats were used for these experiments. Five rats received injections of Fluorogold (FG, Fluorochrome LLC, Denver, CO) in the LPN to label corticothalamic and tectothalamic cells by retrograde transport. Four rats received injections of biotinylated dextran amine (BDA, 3,000 MW; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in the visual cortex to label corticothalamic terminals by anterograde transport. Three rats received injections of phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin (PHAL, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in the SC to label tectothalamic terminals by anterograde transport. Brains from an additional 4 rats were used for the immunocytochemical localization of the type 1 and type 2 vesicular glutamate transporters (vGLUT1 and vGLUT2). Finally, 3 rats received injections of ibotenic acid (MP Biomedicals, Aurora, OH) in the SC to determine whether vGLUT1 or vGLUT2 staining of the LPN was diminished after the destruction of tectothalamic cells. All procedures conformed to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the University of Louisville Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tract tracing

The rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of sodium pentobarbital (initially 50mg/kg, with supplements injected as needed to maintain anesthesia) or intramuscular injections of ketamine and xylazine (initially 100 mg/kg and 6.7 mg/kg respectively, with supplements to maintain anesthesia). They were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus and prepared for aseptic surgery. BDA (5% in saline) PHAL (2.5% in water), or FG (10% in saline) were injected through a glass micropipette (20–30 µm tip diameter) using 5 µA of continuous positive current for 10–20 minutes. 2 µL of ibotentic acid (2% in saline) was ejected from a glass micropipette (10–20 µm tip diameter) using a PV830 pneumatic PicoPump (WPI, Sarasota, FL). After a survival time of one week, the rats were perfused transcardially with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) or Tyrode solution followed by a fixative solution of 4 % paraformaldehyde, or 2.5–3% paraformaldehyde and 1–1.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 (PB).

The brain was removed from the skull, and the thalamus was sectioned to a thickness of 50 µm using a vibratome and placed in PB. The transported FG was revealed by incubating sections overnight at 4°C in the goat anti-FG antibody diluted 1:10,000. The next day the sections were incubated one hour in a biotinylated rabbit anti-goat antibody (Vector) diluted 1:100, followed by 2 hours in a solution containing a complex of avidin and biotinylated horseradish peroxidase (ABC). The transported PHAL was revealed by incubating sections overnight at 4°C in the biotinylated goat anti-PHAL antibody diluted 1:200, followed by 2 hours in ABC. The transported BDA was revealed by incubating sections overnight at 4°C in ABC solution. Sections containing FG, PHAL or BDA were subsequently reacted with nickel intensified diaminobenzidine (DAB) for five to 10 minutes, and washed in PB. Sections were then mounted on slides for light microscopic examination, or prepared for electron microscopy. Light level photographs were taken using a digitizing camera (Spot RT, Diagnostic Instruments Incorporated, Sterling Heights, MI), and terminal distributions were plotted using a Neurolucida system.

Antibody characterization

The antibodies used in this study are listed in Table 1. Preabsorption of the type 1 and type 2 vesicular glutamate transporter (vGLUT1 and vGLUT2) antiserums with their corresponding immunogen peptides (Chemicon catalogue #AG208 and AG209; 1 µg/ml immunogen peptide added to the diluted antibody) eliminated all terminal staining in tissue sections containing the thalamus and cortex (mouse, rat, tree shrew and cat tissue perfusion fixed with 4 % paraformaldehyde, or 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde for previous studies). Western blot of rat cerebral cortex tissue with the vGLUT1 antibody reveals a single band at approximately 60kDa (Melone et al., 2005). Using the vGLUT1 antibody, the thalamic staining pattern we obtained was similar to that obtained in rat by Kaneko and Fujiyama (2002). Western blot of cultured astrocytes from rat visual cortex with the vGLTU2 antibody reveals a single band at approximately 62kDa (Montana et al., 2004). The vGLUT2 antibody stains terminals in the tectorecipient zones of the tree shrew pulvinar nucleus (Chomsung et al., 2008). As described in the results section, the vGLUT2 antibody revealed a similar pattern in rat tissue.

Table 1.

Primary antibodies used in this study

| Antigen | Dilution | Host species |

Source | Catalogue # | Immunogen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABA | 1:2000 | rabbit | Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO | A2052 | GABA conjugated to bovine serum albumin using glutaraldehyde |

| PHAL | 1:200 | goat | Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA | BA-0224 Lot #F0623 | PHAL |

| vGLUT1 | 1:7500–1:10,000 | guinea pig | Chemicon Temecula, CA | AB5905 | Amino acid residues 541–560 of rat vGLUT1 |

| vGLUT2 | 1:7500 – 1:10,000 | guinea pig | Chemicon Temecula, CA | AB5907 | Amino acid residues 565–582 of rat vGLUT2 |

| Fluoro-Gold | 1:50,000 | rabbit | Fluorochrom, LLC, Denver, CO | Antibody to Fluoro-Gold | Fluoro-Gold |

The gamma amino butyric acid (GABA) antibody shows positive binding with GABA and GABA-keyhole limpet hemocyanin, but not BSA, in dot blot assays (manufacturer’s product information). In rat tissue, the GABA antibody stains most neurons in the thalamic reticular nucleus and a subset of neurons in the dorsal thalamus. This labeling pattern is consistent with other GABAergic markers used in a variety of species (Houser et al., 1980; Oertel et al., 1983; Fitzpatrick et al., 1984; Montero and Singer, 1984, 1985; de Biasi et al., 1986; Rinvik et al., 1987).

All Fluoro-Gold antibody binding was confined to cells that contained Fluoro-Gold (as determined by their fluorescence under ultraviolet illumination). Staining with the PHAL antibody was restricted to injection sites in the SC, and axons and terminals in the pretectum and LPN.

Vesicular glutamate transporter immunohistochemistry

Sections through the caudal LPN were stained with antibodies vGLUT1 or vGLUT2. 4 rats were perfused transcardially with ACSF followed by a fixative solution of 4% paraformaldehyde, or 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in PB. The brains were removed and 50µm thick parasagittal sections were cut on a vibratome and collected in PB. The sections were incubated overnight in a 1:10,000 dilution of either the guinea pig anti-vGLUT1 or guinea pig anti-vGLUT2 antibodies. The following day the sections were incubated in a 1:100 dilution of a biotinylated goat-anti guinea pig antibody (Vector) for 1 hour, followed by incubation in ABC (Vector) for 1 hour, and a reaction with nickel enhanced DAB.

Electron microscopy

Sections were postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in PB for 1 hour and then dehydrated through a graded series of ethyl alcohol (70%–100%) and embedded in Durcupan resin (Ted Pella, Redding, CA) between sheets of Aclar plastic (Ladd Industries Inc., Burlington, VT). A light microscope was used to identify areas of interest which were excised and mounted on resin blocks. A diamond knife was used to cut ultrathin sections which were placed on Formvar-coated nickel slot grids. Selected sections that contained tracer labeled terminals were additionally stained for GABA using previously described postembedding immunocytochemical techniques (Li et al., 2003c). Briefly, we used a rabbit polyclonal antibody against GABA at a dilution of 1:500–1:2000, and a goat-anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 15 nm gold particles at a dilution of 1:25 (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) to reveal the distribution of GABA. All sections were air dried and stained with a 10% solution of uranyl acetate in methanol for 30 minutes before examination with an electron microscope. Labeled terminals involved in synaptic contacts were photographed, or digitally captured, and the size of the pre- and postsynaptic profiles were measured (SigmaScan software; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Profiles were considered GABA-positive if the density of gold particles overlying them exceeded that found in 95% of small profiles with round vesicles. Profile measurements are expressed as means ± SD. Statistical significance was tested using an unpaired T-test.

Computer Generated Figures

Light level photographs were taken using a digitizing camera (Spot RT; Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Sterling Heights, MI). Electron microscopic images were taken using a digitizing camera (SIA-7C; SIA, Duluth, GA) or negatives, which were subsequently scanned and digitized (SprintScan 45i; Polaroid, Waltham, MA). A Neurolucida system (MicroBrightField, Inc., Williston, VT) was used to plot the distribution of labeled cells and terminals, and the figures were composed using Photoshop software (Adobe Systems Inc, San Jose, CA). Photoshop software was also used to adjust the brightness and contrast to optimize the images, and in some cases the images were inverted (Figure 2) or sharpened (Figure 13).

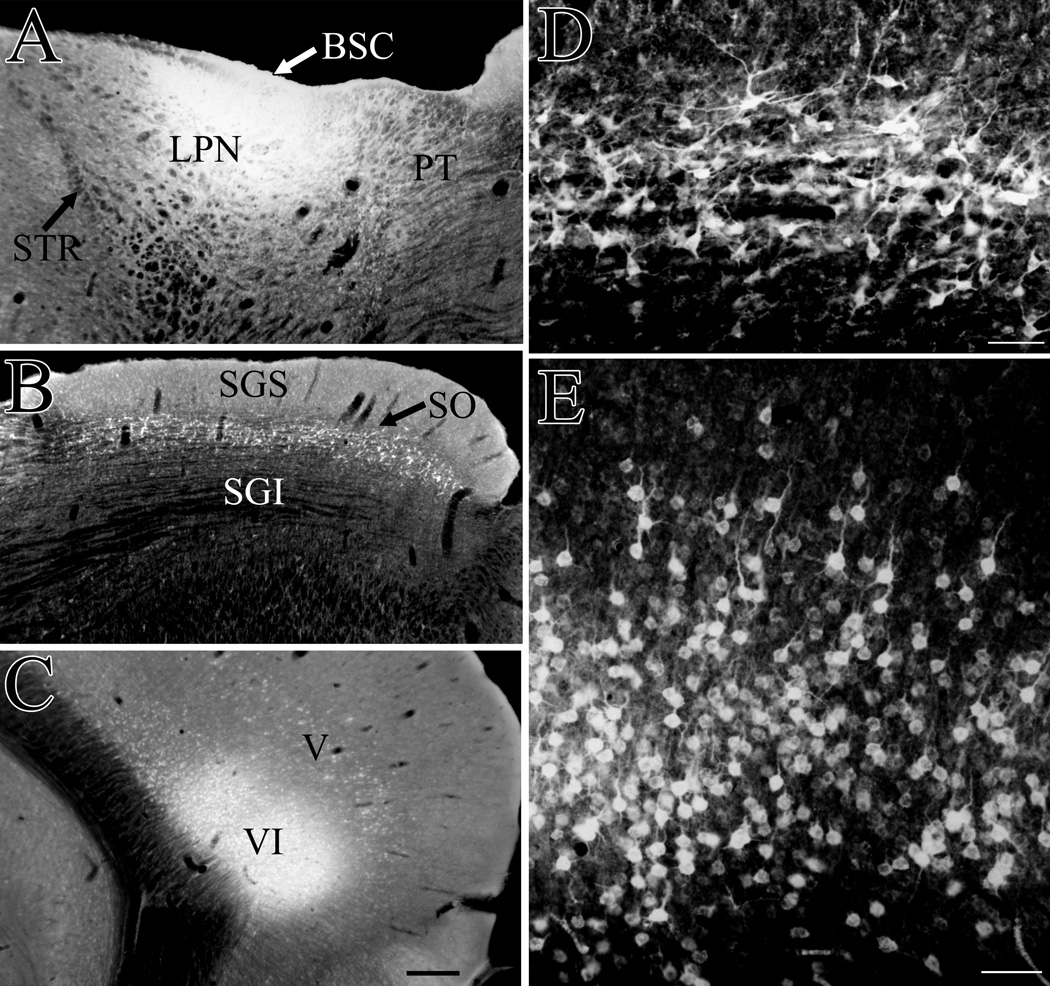

Figure 2.

Following an ionotophoretic injection of fluorogold in the lateral posterior nucleus (LPN, panel A), cells labeled by retrograde transport in the superior colliculus (B, shown at higher magnification in panel D) are primarily distributed in the stratum opticum (SO) and lower stratum grisem superfiale (SGS). Cells labeled by retrograde transport in the visual cortex (C) are primarily distributed in layer VI (shown at higher magnification in panel E), but a smaller band of labeled cells is present in layer V. BSC, brachium of the superior colliculus, PT, pretectum, SGI, stratum griseum intermediale, STR, superior thalamic radiation. Scale bar in C = 300 µm and applies to A and B. Scale bars in D and E = 50 µm.

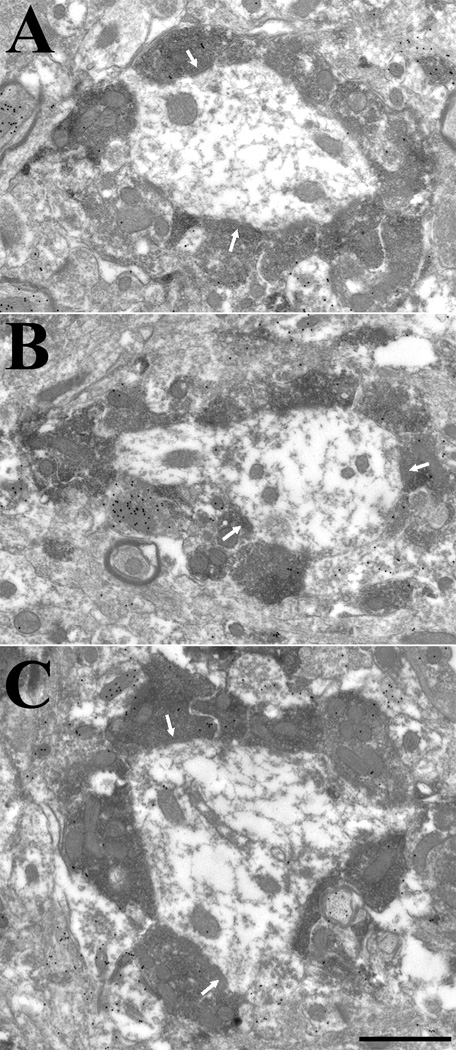

Figure 13.

Terminals in the caudal lateral posterior nucleus against the type 2 vesicular glutamate transporter surround and make multiple contacts (white arrows) with nonGABAergic dendrites (low density of gold particles) of relatively large caliber (A–C). Occasional contacts with GABAergic profiles (+) are observed (panel C). Scale = 1 µm and applies to all panels.

Results

Distribution and morphology of tectal and cortical inputs to the LPN

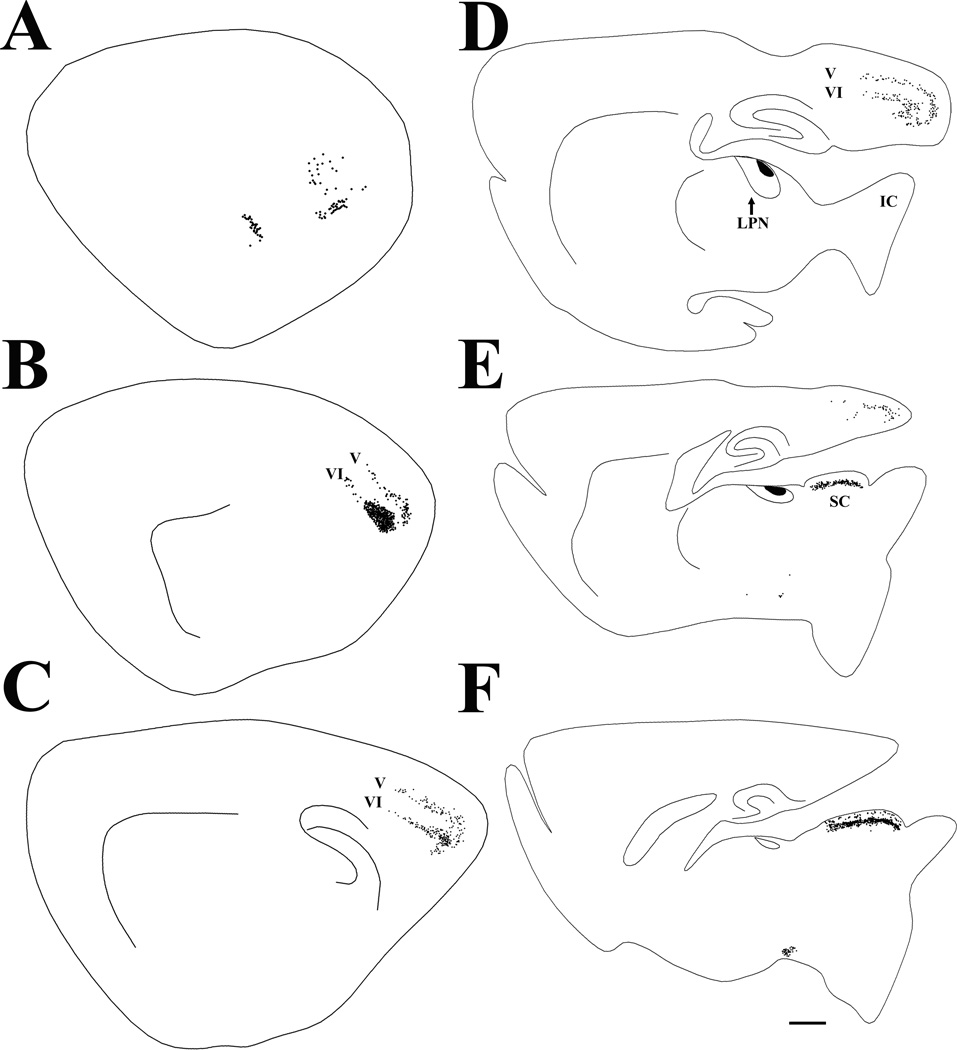

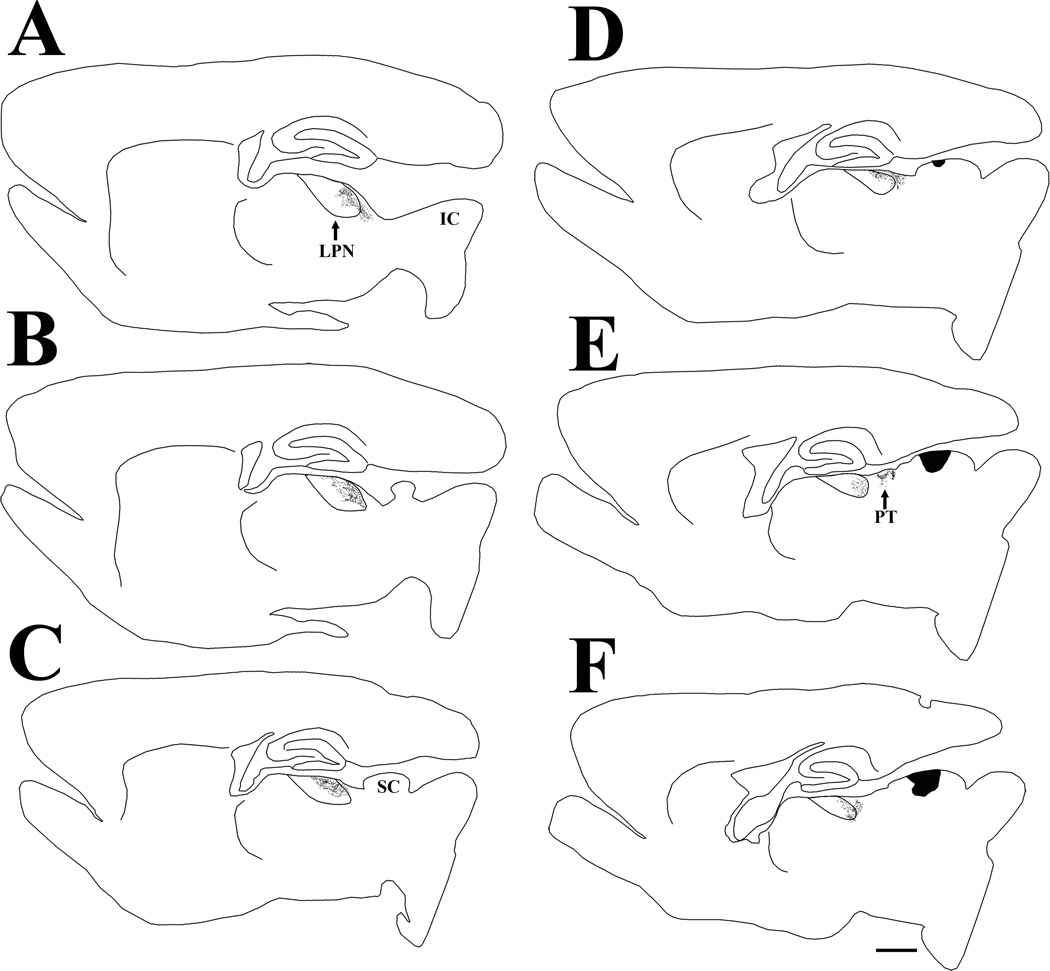

As illustrated in Figures 1 and 2, FG injections in the caudal LPN labeled a dense band of cells in the lower stratum griseum superficiale (SGS) and stratum opticum (SO) of the SC, and a dense cluster of cells in the caudal, lateral cortex, a region corresponding to V2 (Paxinos and Watson, 2007). The majority of cortical cells were distributed in layer VI, but a sparser band of labeled cells was also present in layer V. The labeled cortico-LPN cells, and the vast majority of labeled tecto-LPN cells, were distributed ipsilateral to the injections. As illustrated in Figure 3, PHAL injections into the SGS and SO of the superior colliculus labeled terminals in the caudal/lateral regions of the LPN, as well as the pretectum (PT).

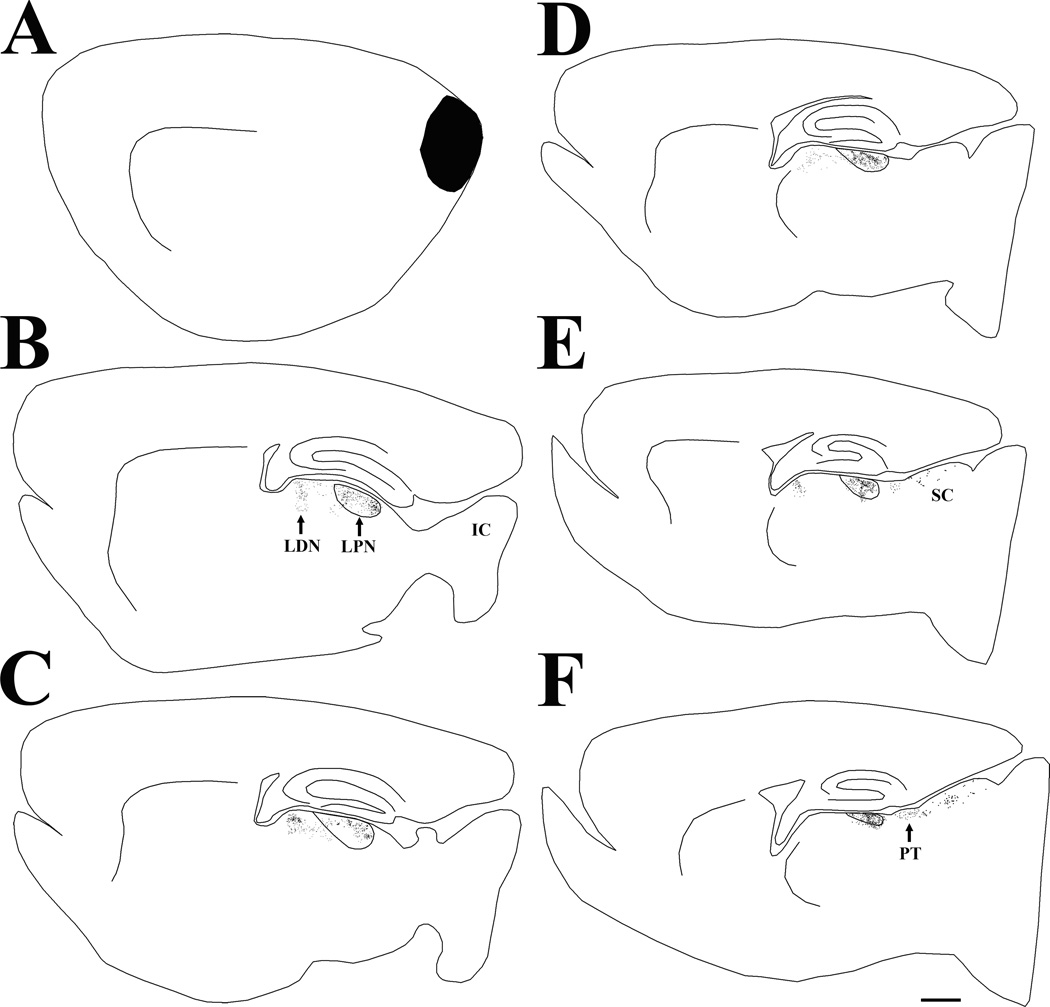

Figure 1.

Following an iontophoretic injection of fluorogold (indicated in black) in the lateral posterior nucleus (LPN), cells labeled by retrograde transport are primarily distributed in the visual cortex (layers V and VI) and the superior colliculus (SC). Each labeled cell is indicated by a black dot in the series of parasagittal sections arranged from lateral (A) to medial (F). Scale bar = 1 mm and applies to all sections. IC, inferior colliculus.

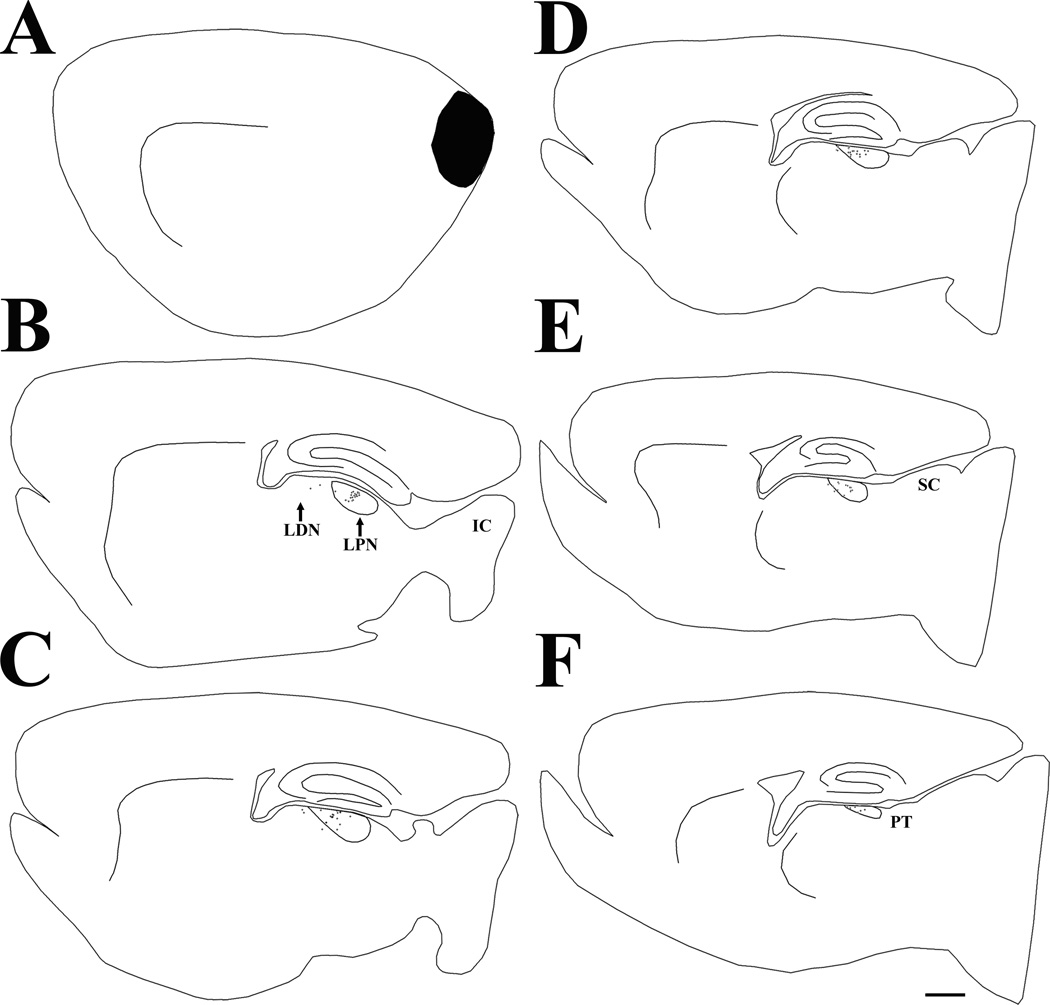

Figure 3.

Following an iontophoretic injection of phaseolus leucoagglutinin in the superior colliculus (SC, indicated in black), terminals labeled by anterograde transport are primarily distributed in pretectum (PT) and the caudal/lateral regions of the lateral posterior nucleus (LPN). The black dots indicate the relative distribution of labeled terminals in the series of parasagittal sections arranged from lateral (A) to medial (F). Scale bar = 1 mm and applies to all sections. IC, inferior colliculus.

As illustrated in Figures 4 and 5, injections of BDA into the lateral cortex (which contained the densest distribution of labeled cells following caudal LPN FG injections) labeled terminals in the LPN, laterodorsal nucleus (LDN), pretectum (PT) and SC. BDA injections into the lateral cortex also labeled cells in the LPN and LDN (by retrograde transport), but for clarity, they are not illustrated. Figure 6 illustrates that injections of BDA in more medial regions of the cortex labeled many terminals in the LDN, LPN, PT, SC, dLGN and vLGN, but very few terminals in the caudal tectorecipient zone of the LPN. This suggests that the caudal LPN FG injections labeled cells in the more medial regions of the cortex via uptake by fibers of passage.

Figure 4.

Following an iontophoretic injection of biotinylated dextran amine in the lateral visual cortex, type I terminals labeled by anterograde transport are distributed throughout the lateral posterior nucleus (LPN), including the caudal tectorecipient zone. The black dots indicate the relative distribution of labeled type I terminals in the series of parasagittal sections arranged from lateral (A) to medial (F). Terminals are also labeled in the laterodorsal nucleus (LDN), pretectum (PT) and superior colliculus (SC). Scale bar = 1 mm and applies to all sections. IC, inferior colliculus.

Figure 5.

Following an iontophoretic injection of biotinylated dextran amine in the lateral visual cortex (same injection as that illustrated in Figure 4), type II terminals labeled by anterograde transport are distributed primarily in the rostral lateral posterior nucleus (LPN) and laterodorsal nucleus (LDN). The black dots indicate the relative distribution of labeled type II terminals in the series of parasagittal sections arranged from lateral (A) to medial (F). Scale bar = 1 mm and applies to all sections. IC, inferior colliculus, PT, pretectum, SC, superior colliculus.

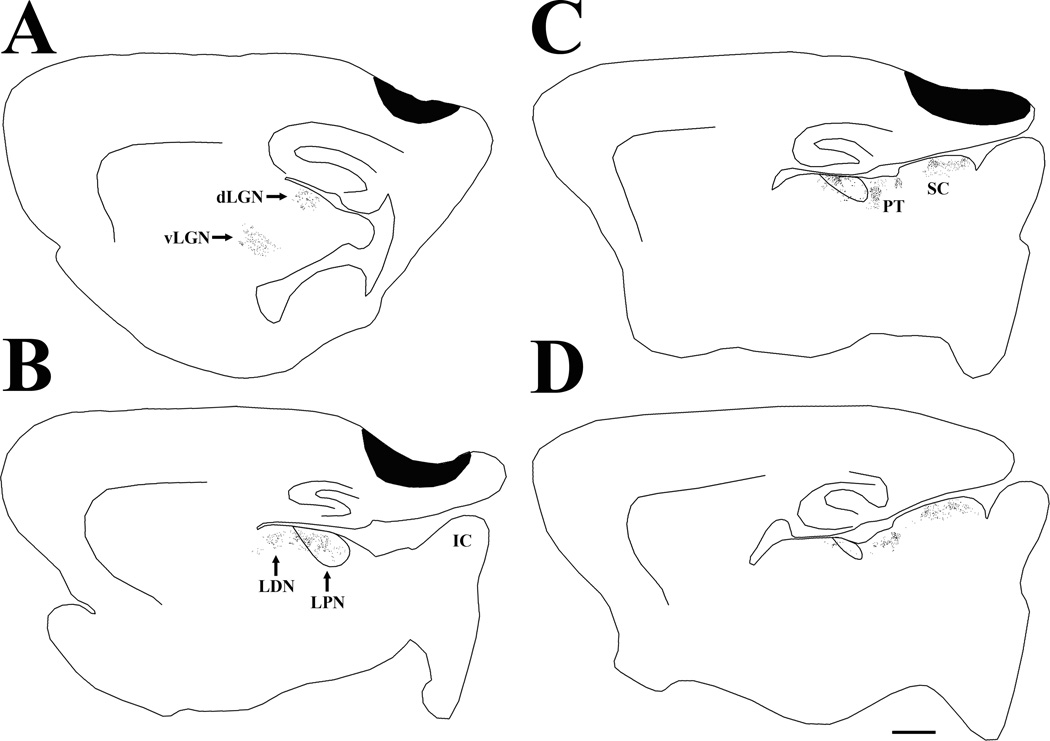

Figure 6.

Following a syringe injection of biotinylated dextran amine in the medial visual cortex, terminals labeled by anterograde transport are distributed in the rostral lateral posterior nucleus (LPN) and laterodorsal nucleus (LDN), but do not extend into the caudal, tectorecipient LPN. The black dots indicate the relative distribution of labeled terminals in the series of parasagittal sections arranged from lateral (A) to medial (D). Labeled terminals are also distributed in the dorsal and ventral lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN, vLGN), as well as pretectum (PT), and superior colliculus (SC). Scale bar = 1 mm and applies to all sections. IC, inferior colliculus.

Figure 7 illustrates the morphology of tecto-LPN and cortico-LPN terminals. Terminals labeled by the anterograde transport of BDA injected into the cortex exhibited two morphologies. The most common type of corticothalamic axon (type I, illustrated in Figure 7A) was thin and gave rise to sparsely distributed small boutons. Occasional en passant boutons were observed, but the most common arrangement was a single bouton at the end of a short axon side branch (“drumstick” ending). More rarely, type II axons (illustrated in Figure 7B) were observed. These were thicker axons that gave rise to large boutons in discrete clusters. As illustrated in Figure 4, type I corticothalamic terminals were distributed throughout the LPN, but type II terminals (Figure 5) were primarily confined to the rostral LPN.

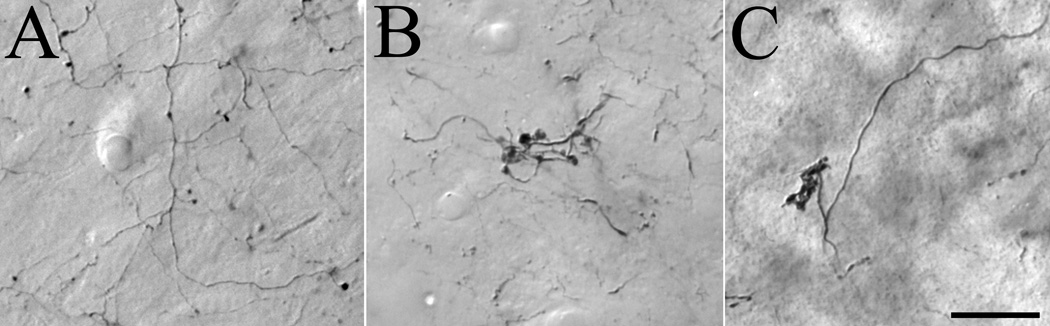

Figure 7.

Three terminal types were identified in the lateral posterior nucleus. Terminals labeled by the anterograde transport of biotinylated dextran amine injected into the cortex exhibited two morphologies. Type 1 terminals (A) are small boutons that are sparsely distributed along relatively thin axons. Type II terminals (B) are large boutons that emanate from thick axons and form discrete clusters. Terminals labeled by the anterograde transport of phaseolus leucoagglutinin injected into the superior colliculus (C) form tubular clusters of medium sized boutons. Scale bar = 20 µm and applies to all panels.

The morphology of terminals labeled by the anterograde transport of PHAL injected into the SC was different than that of either type I or type II cortical terminals. Tecto-LPN boutons were of medium size and often form distinct tubular clusters (illustrated in Figure 7C). Comparison of the distribution of tecto-LPN terminals (Figure 3) to that of cortico-LPN terminals, reveals that the tectal terminal field partially overlaps the distribution of type I terminals (Figure 4), but has virtually no overlap with type II cortical terminals (Figure 5).

Synaptic organization of tecto-LPN terminals

To characterize the synaptic organization of tracer-labeled tecto-LPN terminals, we analyzed electron micrographs of 100 PHAL-labeled terminals involved in synapses by measuring the size of the stained terminals and their postsynaptic partners. The PHAL-labeled terminals were of medium size (0.71 ± 0.32 µm2), in other words larger than our previous measurements of type I cortical terminals in the LPN (0.34 ± 0.11 µm2; Li et al., 2003b), but smaller than our previous measurements of type II cortical terminals in the LPN (2.72 ± 1.27 µm2; Li et al., 2003b). Thus the previous nomenclature of RM (for medium sized terminals that contain round vesicles; Robson and Hall, 1977) is an appropriate classification of rat tecto-LPN terminals.

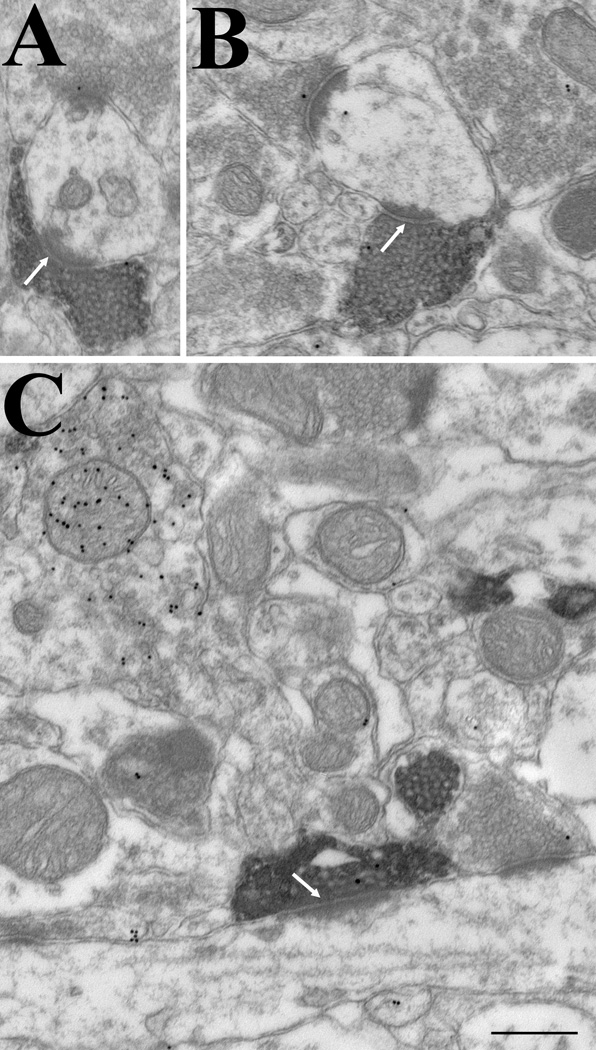

As illustrated in Figure 8, PHAL-labeled tecto-LPN terminals contacted relatively large caliber dendrites (minimum diameter 0.98 µm ± 0.30 µm; n=100). Frequently, several labeled terminals were observed surrounding one dendrite. Using GABA postembedding immunocytochemical techniques, we additionally analyzed the gold particle density overlying 98 tracer labeled terminals and their postsynaptic targets. We found 91% (89/98) of the terminals contacted GABA-negative dendritic shafts (Figure 8 A–E), and 9% (9/98) of the terminals contacted GABA-positive dendrites that contained vesicles (F2 profiles; Figure 8A). In addition, all 98 PHAL-labeled terminals were found to be GABA-negative.

Figure 8.

Terminals in the caudal lateral posterior nucleus labeled by the anterograde transport of phaseolus leucoagglutinin injected into the superior colliculus are nonGABAergic (low density of gold particles) and primarily contact (white arrows) nonGABAergic dendrites of relatively large caliber (A–E). Occasional contacts on GABAergic profiles (+) were observed (panel A). Many dendrites received input from multiple labeled terminals (A, C–E). Scale bar = 1 µm and applies to all panels.

Synaptic organization of corticothalamic terminals in the tecto-recipient LPN

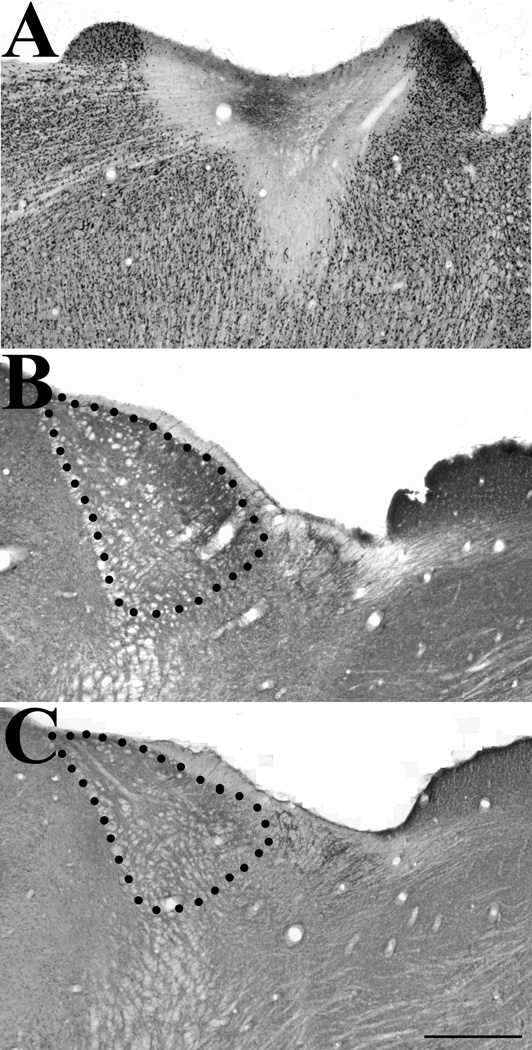

To characterize the synaptic organization of tracer-labeled cortico-LPN terminals, we analyzed electron micrographs of BDA-labeled terminals in the tectorecipient zone of the LPN. We photographed 100 labeled terminals involved in synapses by measuring the size of the stained terminals and their postsynaptic partners. The BDA-labeled terminals were of small size (0.27 ± 0.12 µm2), similar to our previous measurements of type I cortical terminals throughout the LPN (0.34 ± 0.11 µm2; @@Li et al., 2003b). Thus, all cortical terminals in the tectorecipient LPN can be classified as RS profiles (small terminals that contain round vesicles).

As illustrated in Figure 9, BDA-labeled cortico-LPN terminals contacted relatively small caliber dendrites (minimum diameter 0.65 µm ± 0.18 µm; n=100). Multiple labeled terminals were not observed to contact single dendrites. However, multiple unlabeled RS profiles frequently contacted dendrites that were postsynaptic to labeled cortico-LPN terminals (Figure 9 A–C). Using GABA postembedding immunocytochemical techniques, we additionally analyzed the gold particle density overlying 100 tracer labeled terminals and their postsynaptic targets. We found 98% (98/100) of the terminals contacted GABA-negative dendritic shafts (Figure 9 A–E), and 2% (2/100) contacted GABA-positive dendrites. In addition, all 100 BDA-labeled terminals were found to be GABA-negative.

Figure 9.

Terminals in the caudal lateral posterior nucleus labeled by the anterograde transport of biotinylated dextran amine injected into the cortex are small and primarily contact (white arrows) nonGABAergic (low density of gold particles) dendrites of relatively small caliber (A–C). Scale bar = 0.5 µm and applies to all panels.

Distribution of vGLUT1and vGLUT2 in the LPN

Figure 10 illustrates the thalamic staining patterns obtained with antibodies against vGLUT1 or vGLUT2. Terminals stained with the vGLUT1 antibody were densely distributed throughout the entire thalamus, but terminals stained with the vGLUT2 antibody were most densely distributed in the caudal and lateral LPN, overlapping the distribution of tecto-LPN terminals (Figure 3). To determine whether vGLUT2 can be considered a marker for tectal terminals, we injected ibotenic acid into the SC to destroy tecto-LPN cells and then stained the LPN for vGLUT2. As illustrated in Figure 11, vGLUT2 staining was still present in the tectorecipient zone of the contralateral LPN, but was greatly diminished in the ipsilateral LPN. In contrast, vGLUT1 staining was unchanged. This suggests that tecto-LPN terminals contain vGLUT2, but not vGLUT1.

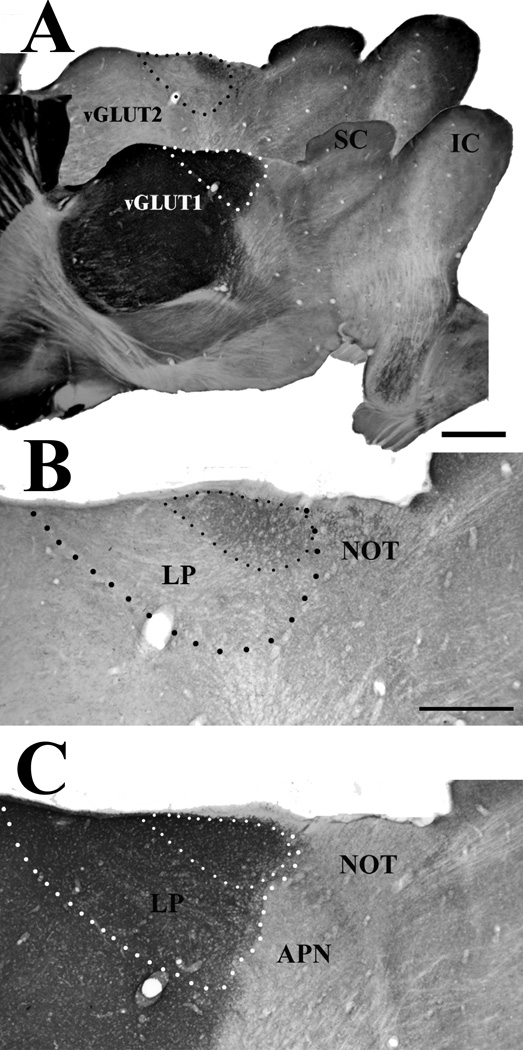

Figure 10.

The caudal part of the lateral posterior nucleus (LPN) stains densely for both the type 1 and type 2 vesicular glutamate transporters (vGLUT1 and vGLUT2). A) The boundaries of the LPN are illustrated in adjacent sections stained for vGLUT1 (white dots) and vGLUT2 (black dots). Scale bar = 1 mm. IC, inferior colliculus, SC superior colliculus. B) Within the LPN, vGLUT2-stained terminals are confined to the caudal LPN, defining the tectorecipient zone (small black dots). vGLUT2-stained terminals are also distributed in the nucleus of the optic tract (NOT). Scale bar = 500 µm and also applies to C. C) Terminals stained for vGLUT1 are densely distributed throughout the LPN (large white dots), but are relatively sparsely distributed in the NOT and anterior pretectal nucleus (APN). Therefore vGLUT1 staining delineates the caudal border of the LPN. The location of the tectorecipient zone of the LPN is indicated with small white dots.

Figure 11.

Immunocytochemical staining for the type 2 vesicular glutamate transporter (vGLUT2) is decreased in the lateral posterior nucleus (LPN) following superior colliculus (SC) lesions. A) An ibotenic acid lesion of the SC is illustrated in a section stained with an antibody against NeuN. B) Contralateral to the SC lesion illustrated in A, vGLUT2 staining is present in the caudal LPN. C) Ipsilateral to the SC lesion illustrated in A, vGLUT2 staining is diminished. Scale bar = 500 µm and applies to all panels.

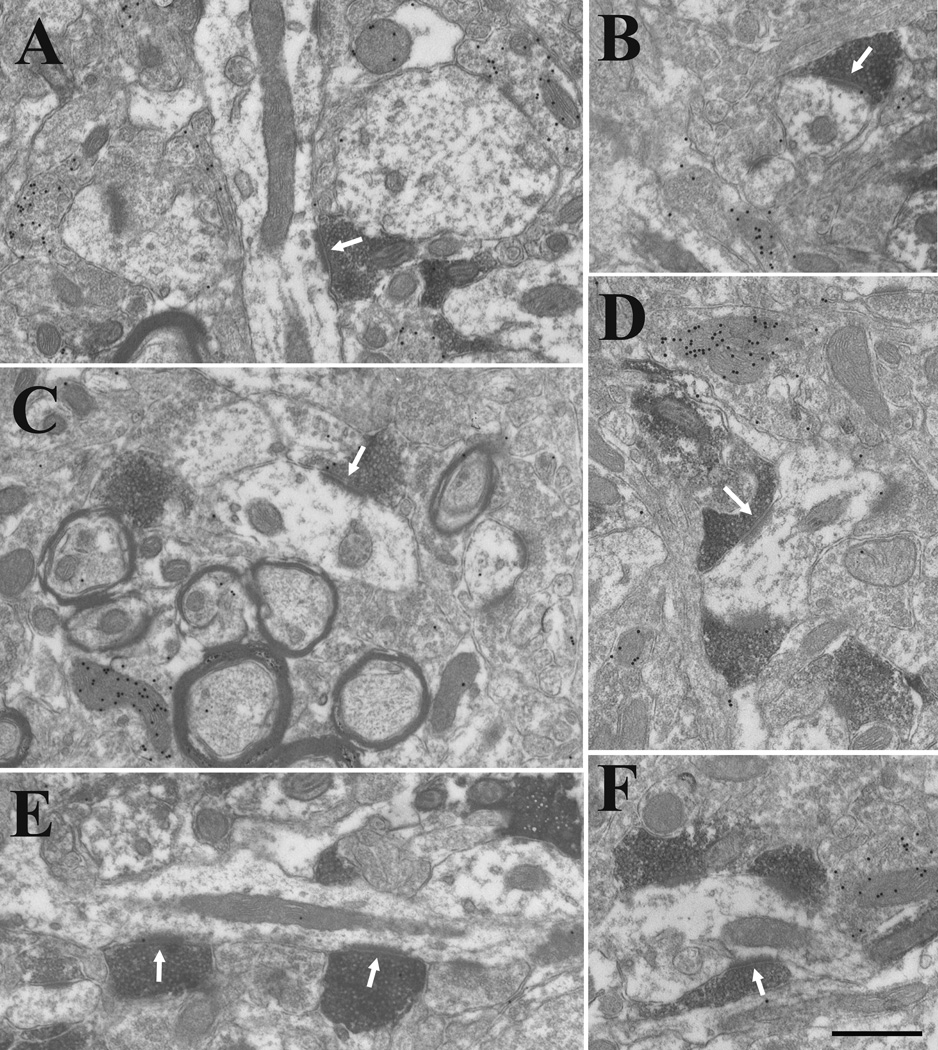

Synaptic organization of vGLUT1- and vGLUT2-stained terminals

To compare the synaptic contacts made by tectal and cortical terminals in the caudal/lateral LPN to those made by vGLUT1 and vGLUT2 stained terminals, we examined tissue stained for vGLUT1 or vGLUT2 using an electron microscope. Examples are illustrated in Figures 12 and 13. We photographed 200 stained terminals involved in synapses (100 stained for vGLUT1 and 100 stained for vGLUT2) and measured the size of the stained terminals and their postsynaptic partners. As illustrated in Figure 14, vGLUT1-stained terminals were smaller (0.33 ± 0.17µm2) than vGLUT2-stained terminals (0.63 ± 0.29µm2), and this difference was significant (P<0.001). In addition, the average minimum diameter of dendrites postsynaptic to vGLUT1 terminals (0.62 µm ± 0.14 µm) was smaller than the average minimum diameter of dendrites postsynaptic to vGLUT2 terminals (0.89 µm ± 0.25 µm), and this difference was significant (P<0.001).

Figure 12.

Terminals in the caudal lateral posterior nucleus labeled with an antibody against the type 1 vesicular glutamate transporter are small and primarily contact (white arrows) nonGABAergic (low density of gold particles) dendrites of relatively small caliber (A–F). Many dendrites are surrounded by multiple labeled terminals (D–F), and labeled terminals form multiple contacts on single dendrites (E). Scale bar = 0.5 µm and applies to all panels.

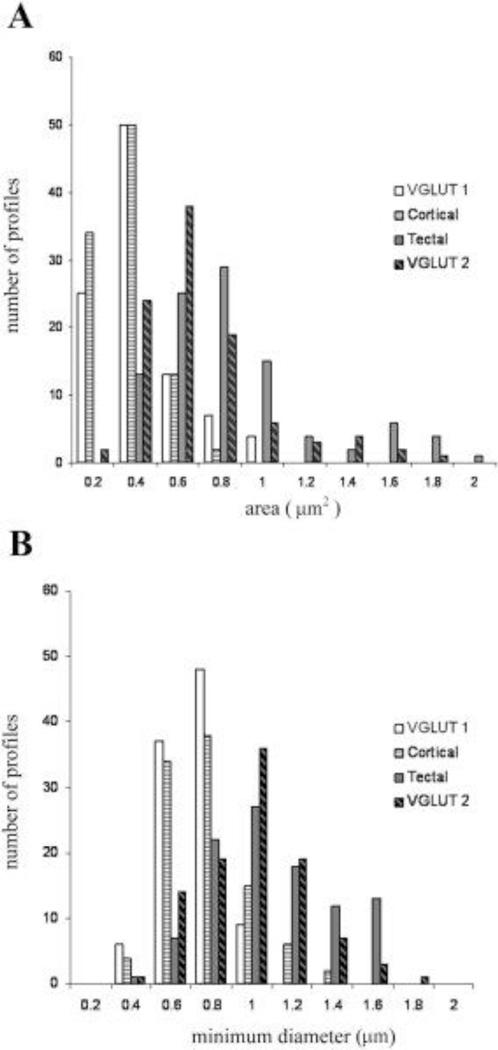

Figure 14.

In the tectorecipient regions of the lateral posterior nucleus, terminals labeled via tracer injections in the superior colliculus (tectal) are larger than terminals labeled via tracer injections in the cortex (cortical), and they contact larger dendrites. Similarly, terminals labeled with an antibody against the type 2 vesicular glutamate transporter (vGLUT2) are larger than terminals labeled with an antibody against the type 1 vesicular glutamate transporter (vGLUT1), and vGLUT2-labeled terminals contact larger dendrites than vGLUT1-labeled terminals. The histogram in A compares the areas of the 4 types of labeled terminals, and the histogram in B compares the minimum diameters of their postsynaptic dendrites.

There was no significant difference between the size of the tecto-LPN terminals labeled by anterograde transport and the size of the vGLUT2-stained terminals (P>0.05), nor was there a significant difference between the sizes of the dendrites they contacted (P>0.05). However, there was a slight difference between the size of cortico-LPN terminals labeled by anterograde transport and the size of vGLUT1-stained terminals (P=0.04), although there was no significant difference between the size of the dendrites they contacted (P>0.05).

Discussion

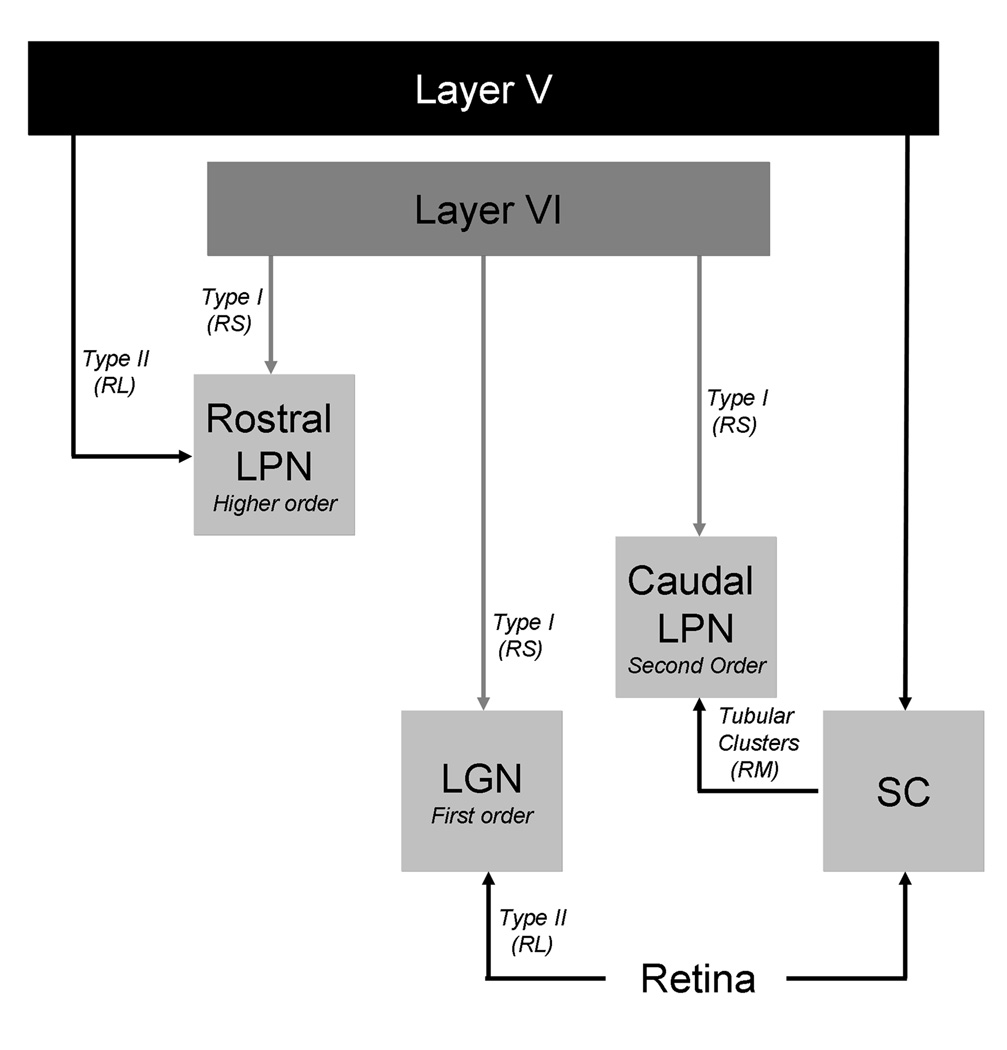

The tectorecipient LPN: “second order” nucleus

Our results indicate that tectal terminals innervate the caudal and lateral LPN, as previously described (Mason and Groos, 1981; Takahashi, 1985), where they form clusters that surround and contact relatively large caliber, nonGABAergic, projection cell dendrites. These observations correlate well with previous anatomical studies of tectothalamic terminals in a variety of other species. Robson and Hall (1977) first described tectothalamic terminals in the grey squirrel pulvinar nucleus as RM profiles, and illustrated the manner in which they encircle relatively large caliber dendrites. Similar patterns have also been observed in the squirrel monkey (Mathers, 1971), Rhesus monkey (Partlow et al., 1977), hamster (Crain and Hall, 1980; Ling et al., 1997), cat (Kelly et al., 2003), and tree shrew (Chomsung et al., 2008).

Our results also indicate that in the caudal/lateral LPN, cortical terminals are small profiles that contact relatively small caliber projection cell dendrites. The size and synaptic location of these terminals suggests that the majority of cortical input to the tectorecipient zones of the LPN arises from layer VI (Bourassa and Deschenes, 1995). In fact, most cells labeled by the retrograde transport of FG injected into the caudal LPN were located in layer VI. However, caudal LPN injections additionally labeled cells in layer V. It seems most likely that, in addition to cortico-LPN cells, our injections labeled corticotectal cells; the axons of corticotectal cells pass through the brachium of the superior colliculus, which was included in most of our injection sites (Figure 2A). The fact that our caudal LPN FG injections labeled cells in both layers V and VI of medial cortical regions that do not project to the tectorecipient LPN (Figure 6) also indicates that FG was taken up by fibers of passage. Alternatively, layer V cells do innervate the caudal LPN, but their axons do not display the type II morphology typically associated with layer V corticothalamic cells (Bourassa and Deschenes, 1995). In either case, we can conclude that cortical terminals are located distal to tectal terminals in the caudal LPN. Similar results have been described in the tectorecipient thalamus of the squirrel monkey (Mathers, 1972), grey squirrel (Robson and Hall, 1977), cat (Li et al., 2000) and tree shrew (Chomsung et al., 2007). Together, these results indicate that the organization of thalamic nuclei innervated by the retinorecipient layers of the SC is different from that observed in either first order or higher order nuclei (summarized in Figure 13).

The organization of the tectorecipient LPN, which we will refer to as a “second order” nucleus, is unique not only because tectal terminals form distinctive tubular clusters, but also because the SC is innervated by the same cortical areas that are targeted by the LPN. Although the precise nature of the signals transmitted by tectothalamic cells is still unclear, their location within the SC suggests that their response properties are created by converging retinal and visual cortical inputs. Thus, caudal LPN activity is influenced directly by layer VI corticothalamic projections, and may be indirectly influenced by layer V corticotectal projections as well. This organization is clearly different from the dLGN, which is innervated directly by retinal ganglion cells, or the rostral LPN which receives little ascending input and is innervated directly by cortical layer V (Bourassa and Deschenes, 1995). It is also clear that tectal inputs do not drive the response properties of LPN cells in a manner similar to retinal inputs to the dLGN. While the response properties of geniculocortical cells are almost identical to the retinal cells that innervate them (Cleland et al., 1971), the receptive fields of tectorecipient LPN cells are much larger than those recorded in the superficial layers of the SC (Chalupa et al., 1983).

vGLUT1 and vGLUT2: markers for corticothalamic and tectothalamic terminals

We found that terminals stained with a vGLUT2 antibody are concentrated in the caudal/lateral LPN, where we found tectothalamic terminals labeled by anterograde transport. Furthermore, lesions of the SC diminished vGLUT2 staining (but not vGLUT1 staining), in the caudal/lateral LPN. Finally, we found no significant difference between the sizes of vGLUT2 stained terminals and tecto-LPN terminals labeled with PHAL, or between the sizes of their postsynaptic dendrites. Together, these results strongly suggest that vGLUT2 is contained within tectothalamic terminals. Tectothalamic terminals in the tree shrew also appear to contain vGLUT2 (Chomsung et al., 2008).

Previous studies have suggested that vGLUT1 can be used as a marker for corticothalamic terminals because vGLUT1 mRNA is found only in the cortex, while vGLUT2 mRNA is found only in subcortical cells (Fremeau et al., 2001; Herzog et al., 2001; Kaneko and Fujiyama, 2002). In addition, vGLUT1 stained terminals are very densely distributed throughout the thalamus, which correlates well with the fact that the majority of terminals in the thalamus are of cortical origin (Erisir et al., 1997). Finally, although we found a slight difference between the sizes of vGLUT1 stained terminals and cortico-LPN terminals labeled with BDA, the majority of the vGLUT1 stained terminals and BDA stained terminals were similar in size. Together, these results suggest that vGLUT1 is contained within corticothalamic terminals, but might also be expressed in a small population of terminals of subcortical origin.

Functional considerations

Robson and Hall (1977) suggested that the clustered arrangements of synaptic terminals in the tectorecipient zone of the grey squirrel pulvinar nucleus allow axons from different areas to converge on single dendrites. This was based on the fact that few terminals in any one cluster degenerated following large lesions of the SC. Similarly, we found that only one or two terminals contacting any one dendrite were labeled by anterograde transport following relatively large injections of PHAL in the SC. In contrast, in material labeled with the vGLUT2 antibody, dendrites were often surrounded by multiple labeled terminals. This suggests that terminals from many tectal axons converge on single dendrites.

This organization is similar to that observed in the pulvinar nucleus of the tree shrew, where we also observed that multiple tectal terminals converge on single dendrites (Chomsung et al., 2008). In the tree shrew, two tectorecipient zones have been identified in the dorsal (Pd) and central (Pc) subdivions of the pulvinar nucleus (Luppino et al., 1988; Lyon et al., 2003). We concluded that both the Pd and Pc receive topographic (specific) projections from the SC, and the Pd receives additional nontopographic (diffuse) projections, possibly arising from convergent axon collaterals (Chomsung et al., 2008).

For this study, the goal of our FG injections was to label all of the inputs to the tectorecipient zone of the LPN. Therefore, we are unable to address the topography of rat tecto-LPN projections. However, a previous study in the hamster concluded that there is a large degree of convergence in the rodent tecto-LPN pathway (Mooney et al., 1984). Thus the available results suggests that individual LPN neurons can be innervated by multiple tectal axons, and each tectal axon can make multiple synaptic connections with LPN cells via dense terminal clusters (Ling et al., 1997; current study Figure 7C).

Our comparison of BDA-labeled cortico-LPN terminals to vGLUT1-labeled terminals also indicates that multiple cortical axons converge to innervate single cells. This is further supported by our in vitro physiological studies. In the caudal LPN, the amplitude of corticothalamic EPSPs gradually increased with increased stimulation currents, suggesting the recruitment of multiple convergent axons (Li et al., 2003a). Together, our results indicate that cells in the tectorecipient LPN receive input from multiple tectal axons on their proximal dendrites, and input from multiple cortical axons on their distal dendrites. Thus, as opposed to the dLGN, where small receptive fields are preserved by restricted retinogeniculate innervation (Cleland et al., 1971), and enhanced by inhibitory circuitry (Hirsch, 2003), the tectorecipient LPN appears to be organized to expand receptive fields (although tectal contacts on interneurons may provide filtering).

In the deep layers of the cat SC, the responses of output cells have been shown to be enhanced by converging visual, auditory and somatosensory signals (Rowland et al., 2007). However, this integration is blocked by cooling of the anterior ectosylvian sulcus (Alvarado et al., 2007), which forms a loop with the SC via connections in the suprageniculate nucleus (Norita and Katoh, 1986; McHaffie et al., 1988; Harting et al., 1992; Benedek et al., 1996). The connections of the tectorecipient LPN may perform a similar function. The relatively large receptive fields of the SC and tectorecipient zones of the thalamus may function to enhance activity related to novel or threatening objects moving across the visual field (Krout et al., 2001).

Supplementary Material

Figure 15.

Summary of synaptic terminal morphology in the rat visual thalamus. Type I terminals are small terminals that emanate from the relatively thin axons of layer VI corticothalamic cells. At the ultrastructural level they are small terminals with round vesicles that innervate distal dendrites (RS profiles). Type II terminals are large terminals that emanate from the relatively thick axons of layer V corticothalamic cells, or from the retina. At the ultrastructural level they are large terminals with round vesicles that innervate more proximal dendrites (RL profiles). Tectothalamic terminals form tubular clusters that surround proximal dendrites. At the ultrastructural level they are medium sized terminals with round vesicles (RM profiles). See text for details.

Acknowledgements

We thank Arkadiusz Slusarczyk and Michael Eisenback for their expert technical assistance. This work was supported by NINDS grants R01NS35377 and F31NS052012.

References cited

- Alvarado JC, Stanford TR, Vaughan JW, Stein BE. Cortex mediates multisensory but not unisensory integration in superior colliculus. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12775–12786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3524-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf ZB, Chomsung RD, Carden WB, May PJ, Bickford ME. Ultrastructural analysis of projections to the pulvinar nucleus of the cat. I: Middle suprasylvian gyrus (areas 5 and 7) J Comp Neurol. 2005;485:87–107. doi: 10.1002/cne.20480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett EL, Stark JM, Guillery RW, Smith PH. Comparison of the fine structure of cortical and collicular terminals in the rat medial geniculate body. Neuroscience. 2000;100:811–828. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00340-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedek G, Fischer-Szatmari L, Kovacs G, Perenyi J, Katoh YY. Visual, somatosensory and auditory modality properties along the feline suprageniculate-anterior ectosylvian sulcus/insular pathway. Prog Brain Res. 1996;112:325–334. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa J, Deschenes M. Corticothalamic projections from the primary visual cortex in rats: a single fiber study using biocytin as an anterograde tracer. Neuroscience. 1995;66:253–263. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalupa LM, Williams RW, Hughes MJ. Visual response properties in the tectorecipient zone of the cat's lateral posterior-pulvinar complex: a comparison with the superior colliculus. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2587–2596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02587.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Regehr WG. Presynaptic modulation of the retinogeniculate synapse. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3130–3135. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03130.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Blitz DM, Regehr WG. Contributions of receptor desensitization and saturation to plasticity at the retinogeniculate synapse. Neuron. 2002;33:779–788. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomsung RD, Petry HM, Bickford ME. Synaptic organization of the projection from the temporal cortex to the tree shrew pulvinar nucleus. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 2007;33:392.10. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsung RD, Petry HM, Bickford ME. Ultrastructural examination of diffuse and specific tectopulvinar projections in the tree shrew. J Comp Neurol. 2008;510:24–46. doi: 10.1002/cne.21763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland BG, Dubin MW, Levick WR. Simultaneous recording of input and output of lateral geniculate neurones. Nat New Biol. 1971;231:191–192. doi: 10.1038/newbio231191a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain BJ, Hall WC. The organization of the lateral posterior nucleus of the golden hamster after neonatal superior colliculus lesions. J Comp Neurol. 1980;193:383–401. doi: 10.1002/cne.901930206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Biasi S, Frassoni C, Spreafico R. GABA immunoreactivity in the thalamic reticular nucleus of the rat. A light and electron microscopical study. Brain Res. 1986;399:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90608-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erisir A, Van Horn SC, Sherman SM. Relative numbers of cortical and brainstem inputs to the lateral geniculate nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1517–1520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig S, Harting JK. Corticocortical communication via the thalamus: ultrastructural studies of corticothalamic projections from area 17 to the lateral posterior nucleus of the cat and inferior pulvinar nucleus of the owl monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395:281–295. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980808)395:3<281::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick D, Penny GR, Schmechel DE. Glutamic acid decarboxylase-immunoreactive neurons and terminals in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. J Neurosci. 1984;4:1809–1829. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-07-01809.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fremeau RT, Jr, Troyer MD, Pahner I, Nygaard GO, Tran CH, Reimer RJ, Bellocchio EE, Fortin D, Storm-Mathisen J, Edwards RH. The expression of vesicular glutamate transporters defines two classes of excitatory synapse. Neuron. 2001;31:247–260. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granseth B, Ahlstrand E, Lindstrom S. Paired pulse facilitation of corticogeniculate EPSCs in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the rat investigated in vitro. J Physiol. 2002;544:477–486. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery RW. Anatomical evidence concerning the role of the thalamus in corticocortical communication: a brief review. J Anat. 1995;187(Pt 3):583–592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting JK, Updyke BV, Van Lieshout DP. Corticotectal projections in the cat: anterograde transport studies of twenty-five cortical areas. J Comp Neurol. 1992;324:379–414. doi: 10.1002/cne.903240308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Gras C, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Bedet C, Gasnier B, Giros B, El Mestikawy S. The existence of a second vesicular glutamate transporter specifies subpopulations of glutamatergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-j0001.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbig H, Bidmon HJ, Ettrich P, Muller A. Projection neurons in the superficial layers of the superior colliculus in the rat: a topographic and quantitative morphometric analysis. Neuroscience. 2000;96:109–119. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00542-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JA. Synaptic physiology and receptive field structure in the early visual pathway of the cat. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13:63–69. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser CR, Vaughn JE, Barber RP, Roberts E. GABA neurons are the major cell type of the nucleus reticularis thalami. Brain Res. 1980;200:341–354. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90925-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T, Fujiyama F. Complementary distribution of vesicular glutamate transporters in the central nervous system. Neurosci Res. 2002;42:243–250. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly LR, Li J, Carden WB, Bickford ME. Ultrastructure and synaptic targets of tectothalamic terminals in the cat lateral posterior nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 2003;464:472–486. doi: 10.1002/cne.10800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krout KE, Loewy AD, Westby GW, Redgrave P. Superior colliculus projections to midline and intralaminar thalamic nuclei of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2001;431:198–216. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20010305)431:2<198::aid-cne1065>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Kelly LR, Carden WB, Bickford ME. Synaptic organization of the cat medial LP nucleus: comparison of tectothalamic and corticothalamic terminals. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts. 2000;26:1469. [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Guido W, Bickford ME. Two distinct types of corticothalamic EPSPs and their contribution to short-term synaptic plasticity. J Neurophysiol. 2003a;90:3429–3440. doi: 10.1152/jn.00456.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Bickford ME, Guido W. Distinct firing properties of higher order thalamic relay neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003b;90:291–299. doi: 10.1152/jn.01163.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Wang S, Bickford ME. Comparison of the ultrastructure of cortical and retinal terminals in the rat dorsal lateral geniculate and lateral posterior nuclei. J Comp Neurol. 2003c;460:394–409. doi: 10.1002/cne.10646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom S, Wrobel A. Frequency dependent corticofugal excitation of principal cells in the cat's dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Exp Brain Res. 1990;79:313–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00608240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling C, Schneider GE, Northmore D, Jhaveri S. Afferents from the colliculus, cortex, and retina have distinct terminal morphologies in the lateral posterior thalamic nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:467–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luppino G, Matelli M, Carey RG, Fitzpatrick D, Diamond IT. New view of the organization of the pulvinar nucleus in Tupaia as revealed by tectopulvinar and pulvinar-cortical projections. J Comp Neurol. 1988;273:67–86. doi: 10.1002/cne.902730107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon DC, Jain N, Kaas JH. The visual pulvinar in tree shrews. I. Multiple subdivisions revealed through acetylcholinesterase and Cat-301 chemoarchitecture. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:593–606. doi: 10.1002/cne.10939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason R, Groos GA. Cortico-recipient and tecto-recipient visual zones in the rat's lateral posterior (pulvinar) nucleus: an anatomical study. Neurosci Lett. 1981;25:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers LH. Tectal projection to the posterior thalamus of the squirrel monkey. Brain Res. 1971;35:295–298. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers LH. The synaptic organization of the cortical projection to the pulvinar of the squirrel monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1972;146:43–60. doi: 10.1002/cne.901460104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHaffie JG, Kruger L, Clemo HR, Stein BE. Corticothalamic and corticotectal somatosensory projections from the anterior ectosylvian sulcus (SIV cortex) in neonatal cats: an anatomical demonstration with HRP and 3H-leucine. J Comp Neurol. 1988;274:115–126. doi: 10.1002/cne.902740111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melone M, Burette A, Weinberg RJ. Light microscopic identification and immunocytochemical characterization of glutamatergic synapses in brain sections. J Comp Neurol. 2005;492:495–509. doi: 10.1002/cne.20743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montana V, Ni Y, Sunjara V, Hua X, Parpura V. Vesicular glutamate transporter-dependent glutamate release from astrocytes. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2633–2642. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3770-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero VM, Singer W. Ultrastructure and synaptic relations of neural elements containing glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) in the perigeniculate nucleus of the cat. A light and electron microscopic immunocytochemical study. Exp Brain Res. 1984;56:115–125. doi: 10.1007/BF00237447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero VM, Singer W. Ultrastructural identification of somata and neural processes immunoreactive to antibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. Exp Brain Res. 1985;59:151–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00237675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney RD, Fish SE, Rhoades RW. Anatomical and functional organization of pathway from superior colliculus to lateral posterior nucleus in hamster. J Neurophysiol. 1984;51:407–431. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norita M, Katoh Y. Cortical and tectal afferent terminals in the suprageniculate nucleus of the cat. Neurosci Lett. 1986;65(1):104–108. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel WH, Riethmuller G, Mugnaini E, Schmechel DE, Weindl A, Gramsch C, Herz A. Opioid peptide-like immunoreactivity localized in GABAErgic neurons of rat neostriatum and central amygdaloid nucleus. Life Sci. 1983;33(Suppl 1):73–76. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogren MP, Hendrickson AE. The morphology and distribution of striate cortex terminals in the inferior and lateral subdivisions of the Macaca monkey pulvinar. J Comp Neurol. 1979;188:179–199. doi: 10.1002/cne.901880113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partlow GD, Colonnier M, Szabo J. Thalamic projections of the superior colliculus in the rhesus monkey, Macaca mulatta. A light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol. 1977;72:285–318. doi: 10.1002/cne.901710302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in steroetaxic coordinates. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Reichova I, Sherman SM. Somatosensory corticothalamic projections: distinguishing drivers from modulators. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2185–2197. doi: 10.1152/jn.00322.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinvik E, Ottersen OP, Storm-Mathisen J. Gamma-aminobutyrate-like immunoreactivity in the thalamus of the cat. Neuroscience. 1987;21:781–805. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(87)90037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson JA, Hall WC. The organization of the pulvinar in the grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis). I. Cytoarchitecture and connections. J Comp Neurol. 1977;173:355–388. doi: 10.1002/cne.901730210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland BA, Quessy S, Stanford TR, Stein BE. Multisensory integration shortens physiological response latencies. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5879–5884. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4986-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW. On the actions that one nerve cell can have on another: distinguishing "drivers" from "modulators". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7121–7126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW. The role of the thalamus in the flow of information to the cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357:1695–1708. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T. The organization of the lateral thalamus of the hooded rat. J Comp Neurol. 1985;231:281–309. doi: 10.1002/cne.902310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JP, Salt TE. Characterization of sensory and corticothalamic excitatory inputs to rat thalamocortical neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 1998;510(Pt 3):829–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.829bj.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidnyanszky Z, Borostyankoi Z, Gorcs TJ, Hamori J. Light and electron microscopic analysis of synaptic input from cortical area 17 to the lateral posterior nucleus in cats. Exp Brain Res. 1996;109:63–70. doi: 10.1007/BF00228627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Krosigk M, Monckton JE, Reiner PB, McCormick DA. Dynamic properties of corticothalamic excitatory postsynaptic potentials and thalamic reticular inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in thalamocortical neurons of the guinea-pig dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Neuroscience. 1999;91:7–20. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtz RH, Sommer MA. Identifying corollary discharges for movement in the primate brain. Prog Brain Res. 2004;144:47–60. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(03)14403-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.