Abstract

Background

Ischemic stroke and other vascular outcomes occur in 10–20% of patients in the 3 months following a TIA or minor ischemic stroke, and many are disabling. The highest risk period for these outcomes is the early hours and days immediately following the ischemic event. Aspirin is the most common antithrombotic treatment used for these patients.

Aim

The aim of POINT is to determine whether clopidogrel plus aspirin taken <12 hours after TIA or minor ischemic stroke symptom onset is more effective in preventing major ischemic vascular events at 90 days in the high-risk, and acceptably safe, compared to aspirin alone.

Design

POINT is a prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial in patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke. Subjects are randomized to clopidogrel (600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg/day) or matching placebo, and all will receive open-label aspirin 50–325 mg/day, with a dose of 162 mg daily for 5 days followed by 81 mg daily strongly recommended.

Study Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome is the composite of new ischemic vascular events: ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction or ischemic vascular death, by 90 days. The primary safety outcome is major hemorrhage, which includes symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage.

Discussion

Aspirin is the most common antithrombotic given to patients with a stroke or TIA as it reduces the risk subsequent of stroke. This trial expects to determine whether more aggressive antithrombotic therapy with clopidogrel plus aspirin, initiated acutely, is more effective than aspirin alone.

Introduction and Rationale

Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) are common and often harbingers of disabling ischemic strokes. Between 200,000–500,000 TIAs are diagnosed each year in the US(1, 2), while approximately 795,000 patients experience a new or recurrent stroke(3).

Rapid recovery of cerebral ischemia is a defining characteristic of TIA and distinguishes it from completed stroke(1, 4–9). This recovery delineates a distinct pathophysiologic feature that generally indicates the presence of previously ischemic tissue still at risk, a characteristic that may be responsible for greater instability(9, 10). The same is true for patients with minor ischemic strokes. The distinction between minor ischemic stroke and TIA is unimportant in terms of prognosis as both groups are at high short-term risk for new, and often disabling, ischemic stroke and other vascular events(11–13). These serious vascular outcomes occur in 10–20% of patients in the 3 months following a TIA or minor ischemic stroke and the highest risk period for these outcomes is the early hours and days immediately following the ischemic event(11–13). Platelet aggregation is an important contributing factor in cerebral ischemia, as in other forms of atherothrombotic ischemia. Antiplatelet drugs reduce the risk of ischemic stroke in this setting. Aspirin is the most common antithrombotic given to patients with a history of stroke or TIA as it reduces the risk subsequent of stroke. More aggressive antithrombotic therapy, especially dual antiplatelet drugs, in patients with prior ischemic stroke is commonly associated with a higher risk of intracranial and other major hemorrhages(14–20). Yet, more aggressive therapies may be effective in TIA and minor stroke patients who are at high short-term risk for thrombosis and have minimal ischemic brain damage that could increase their risk for bleeding. Aggressive antithrombotic therapy could significantly reduce the overall burden of stroke if initiated immediately. The FASTER pilot trial(21) showed a trend towards benefit for this approach. The CHANCE trial is a large-scale trial evaluating an acute intervention in patients with TIA or non-disabling stroke(22) and the results should be published soon.

The purpose of the POINT study is to determine whether clopidogrel, when initiated acutely, is more effective than placebo in preventing major ischemic vascular events in patients with TIA or minor ischemic stroke, on a background of aspirin. This article describes the POINT trial design.

Methods

Design and Patient Population

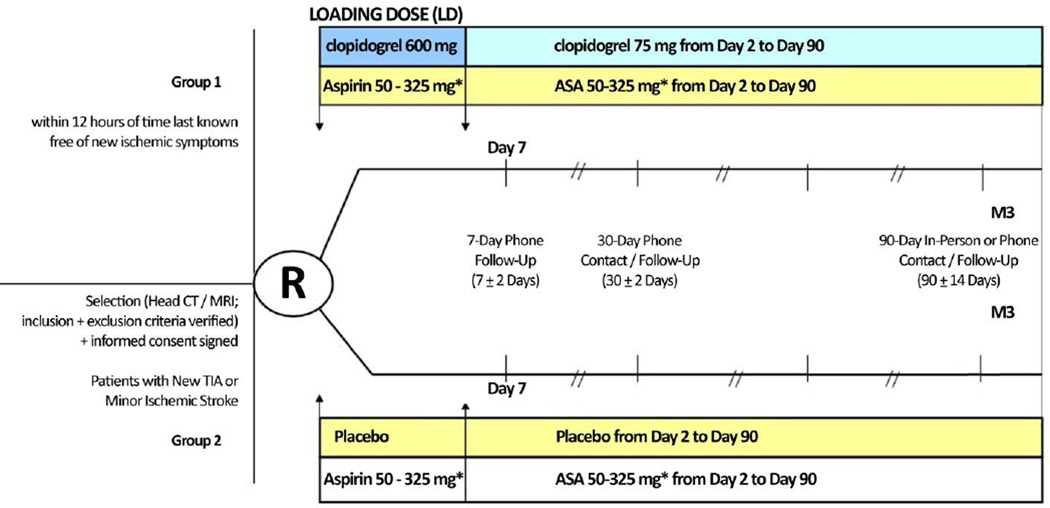

The design of POINT is shown in Figure 1. The trial enrolls subjects 18 years of age or older with high-risk TIAs, defined as an ABCD2 score(23) ≥4, or minor ischemic stroke, with an National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)(24) score ≤3, who can be randomized within 12 hours of the time last known free of new ischemic symptoms. Table 1 lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Study Flowchart

* Open label aspirin (at the discretion of the investigator) with dose of 162 mg daily for 5 days, followed by 81 mg daily for the remaining 85 days, strongly recommended

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion Criteria

|

Exclusion Criteria

|

The study is conducted in accordance with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Code of Federal Regulations (CFR 21), and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines.

Prior to initiating the study, each site obtains Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for the protocol, informed consent document and materials used to recruit subjects. All changes to the protocol are submitted to each site’s IRB for review and approval as appropriate. The trial has received an IND waiver from the FDA.

Each eligible patient who wishes to participate is required to give written informed consent. The consent document explains the risks and potential benefits of the therapy, the procedures for the trial, and alternatives to participation. In addition, a video explanation of the study on an iPad will be provided for potential enrollees. There is no surrogate consent in the study.

The maximum total sample size for the study is 4,150 subjects from up to a total of 210 investigational sites in the United States and worldwide.

Face-to-face study visits occur on the day of randomization, after a possible stroke or MI, and at Day 90. Visits are encouraged when Serious Adverse Events (SAEs) occur. Telephone calls occur on days 7 and 30. Details of the information collected are available in Table 2 in the Supporting Information of the online version of this article.

Randomization

Randomization takes place centrally and electronically via the WebDCU™ clinical trials management system housed at the POINT Statistics and Data Coordinating Center at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). Subjects are randomized 1:1 (clopidogrel: placebo), balanced within clinical centers using the blocked-urn method. The randomization computer program makes the treatment assignment based on the current status of treatment group distribution within each clinical center as well as overall balance of treatment assignment.

Treatment

Patients will be randomized into 2 groups. The first group will receive a 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel, followed by 75 mg/d from Day 2 to Day 90. The second group will receive 8 placebo tablets, matched in appearance and taste to the clopidogrel tablets, followed by 1 placebo tablet daily from Day 2 to Day 90. Both groups will be given open-label aspirin 50–325 mg/day: a dose of 162 mg daily for 5 days, then followed by the recommended 81 mg daily dose. The first dose of study medication is given as soon after randomization as possible, but no later than 12 hours from symptom onset. Each subject is followed for 90 days from randomization. The trial is expected to complete in 7 years.

Outcomes

The primary efficacy outcome is the composite of new ischemic vascular events: ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction or ischemic vascular death, up to 90 days. POINT uses the tissue-based definition of stroke and TIA(25). If a subject has rapid resolution of symptoms, and no brain imaging suggesting tissue infarction, he/she is considered to have had a TIA. Any brain imaging evidence of infarction or clinical evidence (such as symptoms persisting beyond 24 hours) qualifies the event as a stroke. Any patient initially diagnosed with stroke that does not have further brain imaging with evidence of infarction, but who has complete resolution of symptoms within 24 hours is considered TIA.

It often is difficult to determine whether new neurologic deficits that develop after enrollment are due to stroke recurrence, or stroke progression or infarct growth.(26) Since the likely pathophysiology of these events is additional thrombosis, and potentially amenable to prompt antithrombotic treatment, POINT does not distinguish between recurrence and progression.

The primary safety outcome is major hemorrhage. The definition of major bleeding is adapted from the protocol and the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis(27) and PRoFESS Trial(18) definitions. Major hemorrhage is one that results in symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, intraocular bleeding causing loss of vision, need for transfusion of 2 or more units of red cells or equivalent amount of whole blood, need for hospitalization or prolongation of an existing hospitalization or causing death. This may include bleeding events related to surgical procedures. The adjudication committee evaluates all components of the primary efficacy and safety outcomes.

Several secondary analyses will be performed as described under Statistical Considerations including death (all cause), intracerebral hemorrhage, and minor hemorrhage.

Data Safety and Monitoring Board

The NINDS appointed a Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) is advisory to the NINDS. The NINDS is responsible for reviewing the DSMB recommendations to decide whether to continue or terminate the trial, and to determine whether amendments to the protocol or changes in study conduct are required.

Sample Size

The maximum total sample size for the study is 4,150 subjects. With a sample size of 4,150 patients, with 530 events, the study has 90% power to detect a relative risk reduction of 23% with a two-sided alpha of 0.05. The sample size was estimated based on a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.75 (equivalent to RRR of 23%) under the exponential survival distribution (assuming the proportion of patients with events in the placebo group is 15% at Day 90), with inflation to account for two interim analyses for efficacy using O'Brien-Fleming type stopping boundaries. The intent-to-treat (ITT) principle will be applied to the primary outcome analysis, and therefore, the sample size was inflated to safeguard against 5% lost-to-follow-up and/or crossover in the actual treatment received, which may dilute the effect size.

Statistical Analyses

Complete details can be found in the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP), available in Supporting Information of the online version of this article. A final SAP will be issued by the SDMC prior to database lock and before code breaking. The SAP defines all “pre-specified, planned analyses.” The primary null hypothesis of the trial is that in subjects with TIA or minor ischemic stroke treated with aspirin 50–325 mg/day, there is no difference in the event-free survival at the Day 90 follow-up in those treated with clopidogrel (600 mg loading dose then 75 mg/day) compared to placebo when subjects are randomized within 12 hours of time last known free from new ischemic symptoms. The primary outcome is a composite consisting of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, or ischemic vascular death. The primary efficacy hypothesis is tested with the log-rank test for equality of survival curves. This hypothesis is tested with a two-sided 0.05 level of significance. The primary analysis is intention to treat, with inclusion and treatment group defined per the randomization assignment. Subjects missing Day 90 follow-up visits are censored at the last follow-up assessment date. The primary safety outcome is major hemorrhage.

A number of other secondary outcomes are planned to be evaluated separately, including risk of ischemic stroke, all-cause mortality, intracranial hemorrhage, and major hemorrhage, and the composite of the primary outcome and major hemorrhage. The influence of index event type (TIA vs. minor stroke), sex, and race/ethnicity will be evaluated in subgroup analyses.

The analysis strategy outlined for the primary outcome will be used for most of the secondary analyses. Secondary analyses will be tested at the two-sided alpha of 0.05 without accounting for multiplicity. These analyses will be viewed as exploratory hypotheses that may or may not support the results of the primary analysis.

After 1/3 and 2/3 of events occur, formal interim analyses of the primary outcome will be conducted to consider stopping the trial for overwhelming efficacy or for futility. The criterion for determination of futility is as follows: if the conditional power (defined as the probability of rejecting the null hypothesis at the final analysis given the data accumulated so far) falls below 20%, then the DSMB evaluates all study information (such as overall recruitment rate and secondary outcome assessment data) to consider stopping the study for futility. Conditional power is computed under two assumptions: assuming the alternative is true and assuming the current trend is true. At the time of the first interim analysis, the sample size may be re-estimated solely based on the placebo event rate. If the one-sided upper 99% confidence limit around the observed placebo rate does not overlap with those of the assumed rate 15.24% with a 95% CI (13.63%, 16.85%) based on a sample of 1,907 TIA patients from KPNC(12), then the maximum sample size will be re-estimated based on the observed placebo event rate (assuming the original treatment effect, HR=0.75).

Study Organization and Funding

The principal investigator, who has ultimate responsibility for all activities and products of the trial, and oversees all functions, directs the trial.

The trial management is a partnership of the (University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Clinical Coordinating Center (UCSF CCC) based in the Stroke Sciences Group (SSG), the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials (NETT) Network, which is responsible for statistical analyses, data management and oversight of NETT sites, and the POINT CRC, supported by The EMMES Corporation, which manages the non-NETT sites, including the sites outside the United States.

The NINDS NETT Network, through its Statistical and Data Management Center (SDMC), provide statistical support and data management services, including reports to the DSMB and Clinician Events Coordinator, and shielding of the UCSF CCC, NETT-CCC and POINT CRC from access to unblinded data during the trial. The Director of the NETT SDMC is responsible for the randomization protocol, statistical analysis plan, and final data analysis.

The NINDS funds the POINT. Sanofi contributes clopidogrel and its placebo at no cost and with no restrictions. The principal investigator and executive committee will have full access to the entire dataset at trial completion and are responsible for analysis and publication in collaboration with the sponsor.

Discussion

People who experience a TIA or minor ischemic stroke are at substantial risk for a major stroke and other ischemic events in the subsequent hours and days. They are most often given aspirin for anti-atherothrombotic treatment. Others are treated with clopidogrel or aspirin plus dipyridamole. Recently, more of these patients are treated with clopidogrel plus aspirin for several days or weeks, especially if they experience a cerebral ischemic event while on aspirin. It is not known whether this latter treatment is efficacious or safe. The POINT trial will evaluate whether clopidogrel plus aspirin is more effective, and acceptably safe, than aspirin alone in preventing ischemic stroke and other vascular outcomes in the high-risk period after TIA or minor ischemic stroke when the risk for thrombosis is high and the risk for serious hemorrhage should be low. Whether the trial result is positive or negative, it will provide valuable clarification of the appropriate treatment for these patients in whom the best treatment is currently uncertain.

Statements

The authors are solely responsible for the design and conduct of this study, study analyses, and the drafting and editing of the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

S.C. Johnston is funded by NIH grants 1U01 NS062835 and UL1 RR024131; has received research support from the American Heart Association; is coeditor of Journal Watch Neurology and Vice Editor of the Annals of Neurology; is a coholder of a patent on an RNA panel to identify and risk stratify TIA; indirectly receives research support from Sanofi (drug and placebo for this NIH-sponsored trial); receives research support from AstraZeneca; J.D. Easton is funded by NIH grant 1U01 NS062835; is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb; receives research support from AstraZeneca; is on Data Monitoring Boards for Daiichi-Sankyo, Schering-Plough Research Institute, Novartis, Cerevast Therapeutics, Acorda Therapeutics, and Johnson and Johnson, Inc.; Mary Farrant- none; William Barsan is funded by NIH grants 2U01NS056975-06, 2U01NS056975-06, U01NS073476-01, U01 NS 062835, 1U01NS062778, 1-U01-NS-069498-01; Holly Battenhouse- none; Robin Conwit- none; Catherine Dillon- none; Jordan Elm- none; Anne Lindblad is an owner of The EMMES Corporation and through her employment at EMMES is supported by grants and contracts from the DoD, NEI, NINDS, and Acucela; Lewis Morgenstern is funded by U01 NS062835, R01 HL098065, R01 NS070941, R18 HS017690, R01 NS38916, R01 NS062675, U01 NS056975; Sharon N. Poisson- none; Yuko Palesch- none.

References

- 1.Johnston SC, Fayad PB, Gorelick PB, et al. Prevalence and knowledge of transient ischemic attack among US adults. Neurology. 2003;60(9):1429–1434. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063309.41867.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleindorfer D, Panagos P, Pancioli A, et al. Incidence and short-term prognosis of transient ischemic attack in a population-based study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2005;36(4):720–723. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158917.59233.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL, Go AS, et al. Writing Group Members. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2012 Update. Circulation. 2012;125(1):e2–e220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexandrov AV, Felberg RA, Demchuk AM, et al. Deterioration following spontaneous improvement : sonographic findings in patients with acutely resolving symptoms of cerebral ischemia. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2000;31(4):915–919. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aslanyan S, Weir CJ, Johnston CS, Krams M, Grieve AP, Lees KR. The association of post-stroke neurological improvement with risk of subsequent deterioration due to stroke events. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14(1):1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aslanyan S, Weir CJ, Johnston SC, Lees KR. Poststroke neurological improvement within 7 days is associated with subsequent deterioration. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2004;35(9):2165–2170. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000136554.03470.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grotta JC, Welch KM, Fagan SC, et al. Clinical deterioration following improvement in the NINDS rt-PA Stroke Trial. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2001;32(3):661–668. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.3.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard G, Toole JF, Frye-Pierson J, Hinshelwood LC. Factors influencing the survival of 451 transient ischemic attack patients. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1987;18(3):552–557. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston SC, Leira EC, Hansen MD, Adams HP., Jr Early recovery after cerebral ischemia risk of subsequent neurological deterioration. Annals of neurology. 2003;54(4):439–444. doi: 10.1002/ana.10678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston SC, Easton JD. Are Patients With Acutely Recovered Cerebral Ischemia More Unstable? Stroke. 2003;34(10):2446–2450. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000090842.81076.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giles MF, Rothwell PM. Risk of stroke early after transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(12):1063–1072. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2901–2906. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothwell PM, Warlow CP. Timing of TIAs preceding stroke: Time window for prevention is very short. Neurology. 2005;64(5):817–820. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152985.32732.EE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antman EM, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, et al. Early and late benefits of prasugrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a TRITON-TIMI 38 (TRial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet InhibitioN with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction) analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(21):2028–2033. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatt DL, Flather MD, Hacke W, et al. Patients with prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the CHARISMA trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49(19):1982–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Management of atherothrombosis with clopidogrel in high-risk patients with recent transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke (MATCH): study design and baseline data. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;17(2–3):253–261. doi: 10.1159/000076962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrow DA, Braunwald E, Bonaca MP, et al. Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;366(15):1404–1413. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(12):1238–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The ACTIVE Investigators. Effect of Clopidogrel Added to Aspirin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009;360(20):2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The SPS3 Investigators. Secondary Prevention of Small Subcortical Strokes Trial (SPS3) ClinicalTrialsgov Identifier: NCT00059306. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, Eliasziw M, Demchuk AM, Buchan AM. Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. The Lancet Neurology. 2007;6(11):961–969. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Johnston SC. Rationale and design of a randomized, double-blind trial comparing the effects of a 3-month clopidogrel-aspirin regimen versus aspirin alone for the treatment of high-risk patients with acute nondisabling cerebrovascular event. American heart journal. 2010;160(3):380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.05.017. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283–292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyden P, Brott T, Tilley B, et al. Improved reliability of the NIH Stroke Scale using video training. NINDS TPA Stroke Study Group. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1994;25(11):2220–2226. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.11.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40(6):2276–2293. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coutts SB, Hill MD, Campos CR, et al. Recurrent events in transient ischemic attack and minor stroke: what events are happening and to which patients? Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2008;39(9):2461–2466. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.513234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulman S, Kearon C. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.