Abstract

Spectacular advances in the throughput of DNA sequencing have allowed genome-wide analysis of epigenetic features such as methylation, nucleosome position and post-translational modification, chromatin accessibility and connectivity, and transcription factor binding. However, for rare or precious biological samples, input requirements of many of these methods limit their application. In this review we discuss recent advances for low-input genome-wide analysis of chromatin immunoprecipitation, methylation, DNA accessibility, and chromatin conformation.

Keywords: epigenome, high-throughput sequencing, single cell, methylation, chromatin

The advent of cost effective massively-parallel short-read sequencing has led to the sequencing of thousands of human genomes1,2 providing a glimmer of the much vaunted “personalized genomics revolution.” But perhaps more importantly, high-throughput sequencing has brought about a sea change in the types of mechanistic biological questions that can be addressed, at genome-wide scale. Any biological question that might be transformed into DNA fragments may now be investigated with hundreds of millions to billions of individual measurements, providing a powerful window into genome-wide molecular functions. Arguably, nowhere has this fundamental methodological change been more apparent than in the field of epigenomics3,4.

For the purposes of this review, we will define the epigenome as the set of chemical and physical modifications of the genome that do not comprise changes in the primary sequence of the DNA. These changes encompass a diverse set of transformations, from DNA methylation5,6, to changes in positions and chemical composition of nucleosomes1,7, to the binding of transcription factors3,8, to higher-order changes in the manner in which the genome is folded and or made accessible within the nucleus5,6,9,10.

Substantial insight into the epigenetic information coded within the nucleoprotein structure of chromatin have come from molecular biological methods that then couple into high-throughput sequencing5,11. Chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing (ChIP-seq) protocols have enabled investigation of nucleosome modifications and their correlation with functional elements genome-wide, as well as an more comprehensive understanding of binding sites of transcription factors11,12. Methods to sequence fragments generated from the digestion of chromatin with MNase have allowed comprehensive cataloging of nucleosome position in human cells13,14. A number of strategies for assessing the methylation state of bases within the genome, either in a defined subset of genomic loci, or genome wide, have also transformed our understanding of the dynamics of methylation changes in early development, during differentiation, and in cancer1,15-21. Finally, chromatin “openness” – the accessibility of DNA to transcription factors, RNA polymerases, and other components involved in gene expression – has been explored by coupling DNase I hypersensitivity assays and high throughput sequencing. The assay of DNA accessibility in particular has proven an information-rich, genome-wide analysis tool, allowing identification of areas of active transcription factor binding, active transcription start sites, enhancers, microRNA expression, and insulators in a wide variety of cell lines and tissue samples22-26. To determine how these regulatory regions, or even all regions in the genome, fold and interact with other regions, a number of methods capable of recording the conformation of chromatin have been employed to link regions that have a high probability of interaction27-32. In sum, these methods, when amplified by their application by scientific consortia such as the ENCODE project33 and the Roadmap Epigenomics Project34, have clearly demonstrated that the physical position, compaction, and chemical modifications of histone particles encode a complex and dynamic molecular “state machine” of the cell, defining cell type specific functional regions of the genome.

Despite these substantial insights, current methods for assaying chromatin structure and composition are often substantially limited by cell input requirements. These methods often require on the order of tens to hundreds of millions of cells as starting material3,12,35-38, and these input requirements are limiting in a number of ways. First, these methods average out or drown out both dynamic heterogeneity and standing variation in cellular populations. In this way, fine-scale, subpopulation-level variability in epigenomic structure that may be crucial to understanding the drivers of phenotype in complex samples is lost to ensemble averaging over cellular populations. Second, cells must often be grown and expanded in culture to obtain sufficient starting material. These ex vivo methods of cellular propagation may well modulate the epigenetic state in unknown ways. Indeed, for many dynamic and transient cellular populations, the time required to expand cultures in vitro to the degree necessary for genome-wide investigations will allow the dynamic state of the sorted population to interconvert, frustrating ensemble genome-wide assays. Finally, the requirements of large amounts of input material, especially when coupled with relatively complex workflows that often accompany methods for generating genome-wide epigenomic information, make application of these powerful methods more difficult in primary tissues, complicating possible clinical applications. Indeed, as our mechanistic understanding of epigenetic drivers of phenotypic change grows, the application of these methods to a broad diversity of human samples, both normal and diseased, promises to provide valuable, and potentially clinically actionable insights.

Thus while powerful genome-wide epigenome analysis methods would provide a picture of epigenomic composition within phenotypically isolated, homogenous, and/or rare primary cells, these ensemble methods still wash out the single-cell variability that may be present within the population.. As an ultimate goal, we might hope these genome-wide techniques to be adapted for the fundamental limit of input material–the single cell39,40. Indeed single cell methods might be applied to two important classes of problem. The first where individual cells might be selected from a group of relatively abundant cells to unravel fine-scale epignomic variation, and the second wherein a small group of rare cells might be profiled to increase the sensitivity of assessing epignomic state of the selected population. Such capabilities will provide a never before seen window into cellular epigenomic and gene-regulatory variation, and adding this crucial dimension of analysis to the lists of single cell genome-scale investigation, which currently include genome sequencing and gene expression analysis. Recent work has begun to apply a variety of methodologies, from microfluidics to novel enzymes to clever molecular biological manipulations, to drive the input requirements of these methods while, ideally, maintaining data quality. This review will focus on four methodological areas that have seen recent developments on this front: ChIP-seq, methyl-seq, DNA accessibility, and chromosome conformation capture.

ChIP-seq

While a number of reports have detailed protocols for low-input (i.e. < 100,000 cells) ChIP-qPCR and ChIP-chip assays41-44, a smaller subset have been demonstrated compatible with a high-throughput sequencing output. Two notable papers from the laboratory of Bradley Bernstein have described ChIP-seq data generated from as few as 10,000 cells45,46. This protocol, referred to as nano-ChIP-seq, relies on a workflow fairly similar to a standard ChIP-seq workflow, coupled with well-calibrated sonication dosage and antibody concentrations, as well as two separate PCR amplification steps, to extend the sensitivity of the ChIP-seq assay for post-translationally modified nucleosomes to the level of 10,000 input cells. This methodology was initially applied to hematopoietic progenitors, providing evidence that developmental regulators in these HSC cell types are enriched for bivalent domains. While the reduction in cell number from ~2 × 107 to ~104 reduces overall signal intensity, peak calls of H3K4me3 modifications from nano-ChIP were highly concordant with calls from a standard ChIP-seq protocol45.

A distinct approach from the same laboratory involves the direct single molecule sequencing of ChIP fragments using the Helicos single molecule sequencing methodology47. In this approach a standard protocol for ChIP of three types of modified histones, as well as CTCF, was carried out, and the DNA fragments obtained were then poly(A)-tailed and annealed onto a HeliScope instrument for single molecule sequencing. This technique allows for sequencing with no PCR amplification, thereby allowing a better sampling of fragments independent of GC content. Overall the method is compatible with as little as ~50 pg (or approximately 25-50,000 cell equivalents) of input DNA, and while using this limiting input material reduced the number of over all reads, the correlation with larger input data sets was extremely high47. While Helicos sequencing has become harder to come by in recent years, it is likely that this direct-sequencing approach may be translatable to the single-molecule sequencing platforms of other providers such as Pacific Biosciences, or Oxford Nanopore.

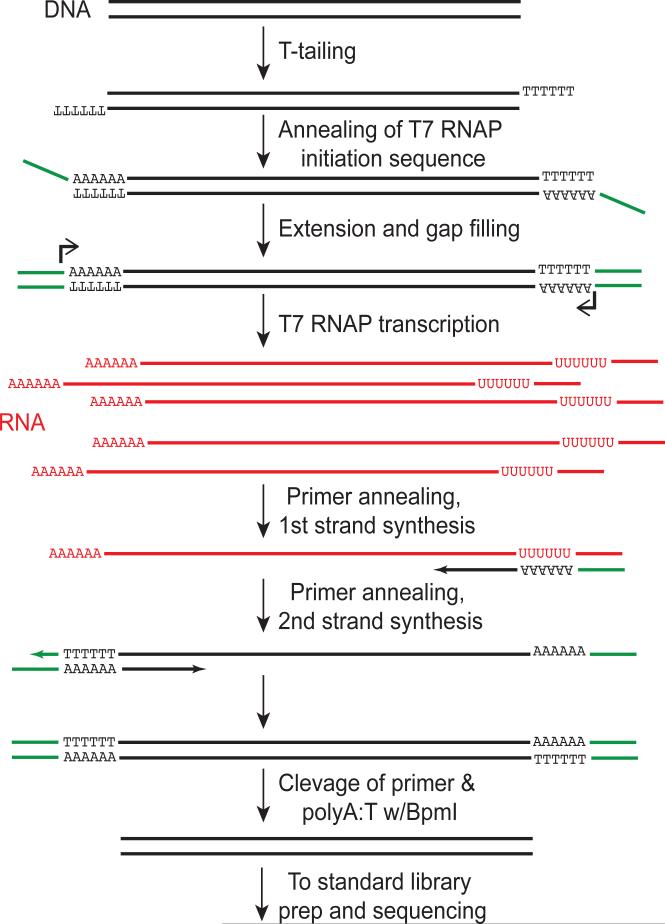

Another pair of papers describing an approach from the Gronemeyer lab rely on distinct molecular biological mechanisms to generate ChIP-seq library compatible with small input requirements48,49. Amplification of ChIP-seq fragments in this protocol was carried out with linear amplification of DNA (linDA), which relies on the T7 RNA polymerase to linearly amplify DNA fragments. In short, fragments generated from standard cross-linking based ChIP-seq protocol are amplified by 1) poly-A tailing, 2) addition of bidirectional T7-initiation promoter, and 3) the transcription of RNA from ChIPed DNA fragments (Fig. 1). All of these initial steps can occur in a single tube. After RNA generation, cDNA is then generated from the RNA, and then this DNA can be used in the standard sequencing library preparation protocol for high-throughput sequencing. While this linear amplification methodology is suitable for T7-RNAP-based linear pre-amplification of any fragment library, it has been successfully applied to produce ChIP-seq maps of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) from as few as 5,000 cells49. In principle, this protocol might be applied to the linear amplification and subsequent sequencing library generation for any set of nucleic acid fragments, making it potentially broadly applicable to genome-wide assays of with limiting input materials. The concept of linear pre-amplification leading to a more faithful representation of the initial fragment distribution has also been used in whole-genome amplification methods50.

Figure 1. Linear amplification of DNA fragments with T7 RNA polymerase.

DNA fragments to be amplified are first poly-T tailed, then a primer (including a BmpI recognition sequence and T7 RNA polymerase (RNAP) transcription initiation site (green)) are annealed, and added via primer annealing , extension and gap filling. Then in vitro transcription generates linearly amplified copies of the DNA (red). These strands are then re-converted to DNA via primer annealing, 1st strand synthesis, 2nd primer (identical to primer 1) annealing and 2nd strand synthesis. Finally, the sequences added are cleaved off via BpmI digestion. Adapted from 48.

Finally, another approach that relies on an indexing-first approach for profiling both post-translational modifications of nucleosomes, as well as transcription factors in scarce cell populations5. In this iChIP methodology, cells are fixed, sorted and then sheared, then immobilized on beads loaded with antibody against histone H3. Fixed on this surface, the fragments that are still associated to the nucleosomes are indexed via ligation of indexing oligos unique to the specific cell type of interest, then the indexed chromatin is released and pooled with other samples. This multiplexed pool of indexed chromatin is then divided among a variety of ChIP experiments (i.e. to assess H3K4me1, H3K4me2, H3K4me3, H3K27Ac, and PU.1 binding). After sequencing, the ChIP-seq data is demultiplexed using the cell-specific barcode. When applied to a variety of cell types within the hematopoetic lineage, this methodology provided excellent signal-to-noise and reproducibility when starting with as few as 500 cells per individual sorted population. This technique is especially powerful when assessing a large cohort of potentially related cell populations, as the pooling of indexed samples allows for increased total amount of material for each distinct ChIP-seq experiment.

Methyl-seq

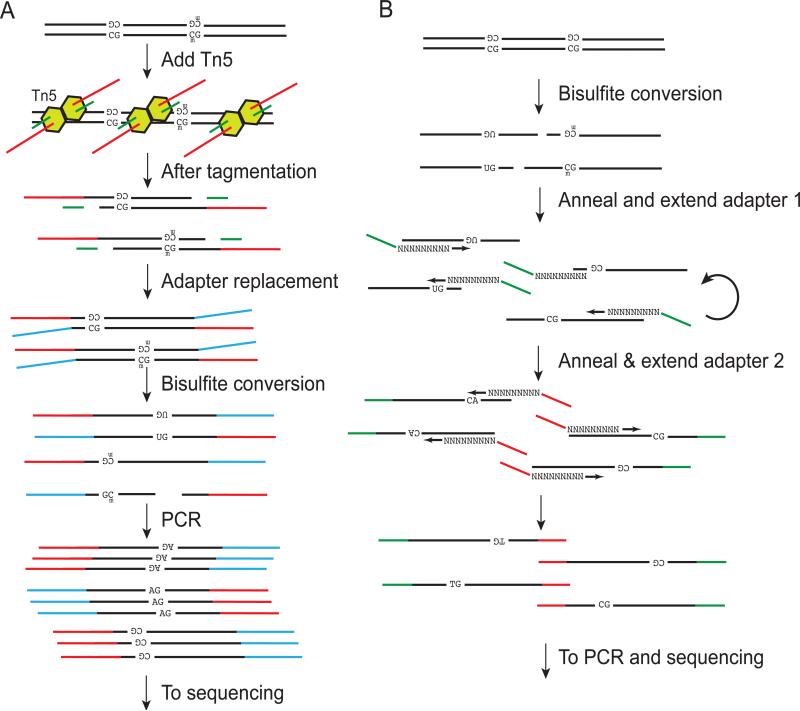

5-methylcytosine is one of the most extensively studied epigenetic features, and differential, or variable, methylation has been detected in a variety of disease states including cancer1. A number of recent directions for decreasing the requirements for input material for these methods have led to improvement in sensitivity of core method of sequencing-based methylation detection51, but here we focus on genome-wide methods. The laboratory of Jay Shendure and Dieter Weichenhan has described a tagmentation-based approach for ultra-low-input whole-genome bisulfite sequencing52,53. This method relies on the Tn5 transposase to simultaneously tag and fragment the genome of interest (Fig. 2A). This Tn5 transposase uses a “cut and paste” mechanism to deliver its DNA payload into the genome, generating PCR-amplifiable fragments rapidly from genomic DNA. To generate a bisulfite sequencing library, the transposase is loaded with specially protected adapter segments (with methylated CpGs) such that these adapters are unreactive to bisulfite treatment. After an adapter-replacement and gap repair step, which allows PCR amplifiable fragments to be generated after the transposition reaction, the fragments are bisulfite-converted, and then PCR amplified, and sequenced using Illumina chemistry. In these steps, harsh bisulfite treatment might cleave the DNA backbone of some members of the library, leaving the fragments incapable of amplification in subsequent PCR steps, whereas full-length fragments that have been chemically converted will be competent for amplification. Thus instead of ligating adapters to DNA fragments and bisulfite converting the libraries, this protocol eliminates a potentially inefficient and time consuming ligation step, improving the number of sequenceble fragments per input cell. This strategy allows for a reported ~100-fold improvement in the input requirements for bisulfite whole-genome sequencing, allowing for high-quality bisulfite maps to be generated from ~2000 cells.

Figure 2. Strategies for small-sample methylation analysis.

A) Genomic DNA is exposed to Tn5 transposase (yellow), generating fragments. Then adapter fragments are replaced and added to the strand, generating independently amplifiable fragments from each strand of the DNA. Bisulfite conversion then transforms un-methylated Cs to Us, which are read as As during PCR. Bisulfite treatment breaks some fragments, which are not amplified in subsequent steps. B) Genomic DNA is sheared, then bisulfite converted, transforming un-methylated Cs to Us. Primers are added by sequential extensions of random primers. In ref 56 this first step is repeated multiple times, whereas in ref 55 these steps are carried out on beads attached through biotynlated primers. After addition of the second primer, optional pre-sequencing PCR converts Us to As and generated a final sequencing library.

The laboratory of Takashi Ito has also reported a genome-wide sequencing based assay of 5-methylcytosine by reordering crucial steps in the sequencing library construction procedure. Instead of ligating adapters prior to bisulfite conversion, bisulfite conversion is instead carried out as the first step (thus the technique is named Post-Bisulfite Adaptor Tagging or PBAT). Unlike standard bisulfite library preparation methods that add adapters to dsDNA prior to conversion, any fragmentation occurring during the bisulfite conversion does not render these fragments non-amplifiable because these fragments may still serve as substrates for subsequent steps that sequentially add adapters to the now single stranded DNA fragments (Fig 2B). To add adapters to these post-bisulfite treated ssDNA fragments, two rounds of sequential primer annealing and extension are employed. In addition, biotinylated primers were used to simplify purification steps. This purification strategy can allow DNA libraries to be directly sequenced with no PCR steps, improving the representation of regions of the genome. Alternately, libraries can be made from even smaller amounts of input material with a smaller number of global PCR steps prior to sequencing. Overall, a whole genome bisulfite map of methyl-C positions was generated without subsequent amplification at an average depth of 21-fold on the mouse genome from 100 ng of astrocyte DNA54. Methylation maps generated with the PBAT process are highly concordant with standard methylC-seq methods.

Other work has described a reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) approach for assaying methylation state genome-wide at the level of individual cells55. While RRBS provides a picture of a subset of genomic methylation37, this technique has proven useful in providing a deep and targeted picture of methylation in genomic subregions17. Guo et al55 show a one-pot RRBS approach that involves isolation and lysis of and individual cell, followed by MSPI digestion, end repair and terminal-A addition, then standard Y-adapter ligation followed by bisulfite conversion and PCR. The approach can assay the methylation state of up to 1.5M CpG sites in the genome. They also applied this technique to haploid cells (sperm and pronuclei).

Finally, very recent work from the labs of Wolf Feik and Gavin Kelsey has described true single cell genome-wide bisulfite sequencing, applying the method to study embryonic stem cell heterogeneity56. This single-cell bisulfite sequencing method (scBS-seq) is able to measure DNA methylation of up to 48% (10.1M) CpG sites within a single cell. This procedure also relies on a efficiency gains obtained by carrying out the bisulfite conversion prior to construction of the sequencing library by using a modified PBAT procedure (Fig. 2B), allowing DNA fragments that are cleaved by bisulfite treatment to be competent for generation of sequencing library in later steps. With these data, the variance in methylation state of within specific genomic regions (as distinct from the mean methylation state, as observed in the bulk) could be assessed. The variance of regions associated with enhancer marks were higher than the genome average, consistent with the presumption that these distal regulatory elements may be showing the first signs of development-specific methylation. Overall, these synergistic works have opened the door to single-cell analysis of methylation variation, blazing a trail that will be further reinforced by further improvements in recovery efficiency of fragments from individual cells, and methods for highly multiplexed single-cell methylation analysis.

DNA Accessibility

DNAse hypersensitivity has been used for more than 30 years to identify regions of the genome that are capable of interacting with DNA binding proteins57,58. Recent work coupling this method to high-throughput sequencing59 has produced genome-wide maps of chromatin accessibility that have transformed our understanding of gene regulation22,23,26. Such assays can identify portions of the genome accessible to the machinery of transcription and to transcription factor binding within different cell types, thereby highlighting phenotype-specific regulatory regions22,23. However, protocols for DNAse-seq generally require tens of millions of reads to generate deep data sets3,35, making exploration of rare or precious samples difficult.

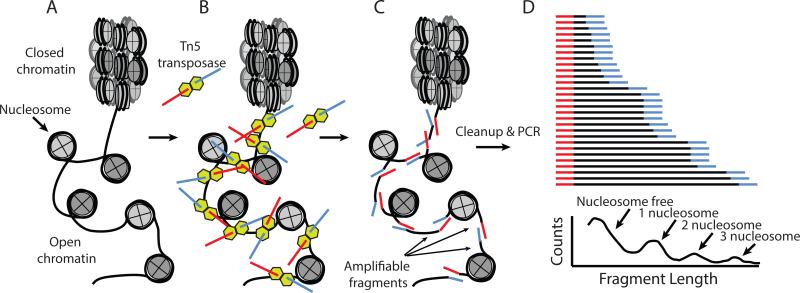

To address these input requirements, recent work has described a transposase-based method for probing the accessibility of chromatin60. Instead of relying upon DNase I to create nicks in accessible regions of DNA, this assay of transposase accessible chromatin, or ATAC-seq, relies on the Tn5 transposome to simultaneously fragment and insert sequencing adapters into the genome (Fig. 3A-C). In this manner, the complex, multi-day protocol for generating DNAse-seq libraries3 is reduced to a workflow for generating sequencing library comprising the steps of 1) isolating native chromatin, 2) exposing this chromatin to purified transposase loaded with sequencing adapters, and 3) amplifying and quantitating library for sequencing. The procedure generates complex (~50 M fragment) libraries from approximately 50,000 cells, and allows the identification of a subset of DNAse-seq peaks from as few as 500 cells60. Furthermore, by sequencing both ends of the DNA fragments generated from the ATAC-seq assay, the fragment size distribution of ATAC-seq fragments can be bioinformatically separated into fragments originating from nucleosome free regions, and reads likely originating from nucleosomes (Fig. 3D). These different sized fragments can then be used to call regions that appear nucleosome free, as well as nucleosomal regions, generating data akin to MNase-seq data13,61,62 within regulatory regions. In a similar manner to DNAse-seq, the insertion pattern of the Tn5 transposome can be used to infer the presence of proteins that interact with DNA60. The workflow simplification coupled with reduction in sample requirements enables the possibility of functional investigations of gene regulation from clinical tissues, or from fluorescently-sorted sub-populations of cells60. While the field has already begun to implement ATAC-seq in the context of limited samples, for example in the hematopoietic niche5, ATAC-seq remains to be applied broadly to a wide variety of different cell types, and the specific sensitivity of ATAC-seq data as compared to DNAse-seq data for determining regulatory elements or inferring TF binding remains to be broadly assessed.

Figure 3. Assaying accessible chromatin with Tn5 transposase.

To map accessible DNA within chromatin, A) native chromatin is isolated, then B) exposed to Tn5 transposase loaded with sequencing adapters. Tn5 can only insert its adapter payload into regions of the genome that are accessible. Fragments generated C) can be amplified after primer extension steps. D) The distribution of fragments comprises short fragments generated from nucleosome free regions of the genome, as well as fragments generated from protection of integer multiples of individual nucleosomes. Adapted from 60

Chromatin connectivity

A full two meters of DNA is folded into a 5 micron cell nucleus within every human cell. The topology of the packaging of chromatin is expected to play a role in gene regulation – from setting the background abilities of different enhancers to interact with promoters to drive expression, to partitioning highly expressed regions and less expressed genomic regions28. A variety of methods for understanding these interactions, including 3-C, 4-C, 5-C, Hi-C, and ChIA-pet have been developed to probe these types of interactions at varying levels of generality 29. The most general, Hi-C28, uses a library preparation whereby two distal regions of the genome that were in close proximity are fragmented and ligated together to produce one chimeric read. When each end of this read is aligned to the genome, the distant alignments provide a pairwise, genome-wide contact map. Initial implementations of the Hi-C protocol required millions of input cells,28 thereby producing a ensemble average picture of the sorts of interactions that occurred with the population of cells of interest.

An recent study described method to generate Hi-C data sets from individual cells to asses the variability of this higher order genome organization from cell to cell63. To achieve this substantial improvement, many aspects of the bulk Hi-C protocol, including the crosslinking of chromatin, restriction enzyme digestion, biotin fill-in and ligation to generate chimeric reads, were all done within the nuclei of the cells of interest. These nuclei were then hand selected and placed into individual tubes, where the rest of the standard Hi-C protocol (i.e. reversion of crosslinks, purification of ligation junctions, and the rest of library preparation) was carried out. The resulting libraries generated more than 1,000 distinct Hi-C read pairs in 37 of the 74 cells that were investigated. While relatively modest number of reads per cell, extensive analysis of these data demonstrated substantial cell-to-cell stochasticity in the structure of condensed DNA – however some global organizational aspects, including the localization of active gene domains to the boundaries of chromosome territories, remained constant63. Future improvements in the efficiency of this single-cell investigation promise an even higher-resolution view of the intricacies of DNA folding, and how this folding varies in larger numbers of cells.

Conclusion

The development of methods capable of interrogating epigenomic components of small numbers of cells—even to the level of individual cells—are enabling the epigenomic profiling of precious or rare tissue samples. However, further thought must also be given to making these methods highly quantitative when input material reaches such very low levels. Unlike RNAseq methodologies, where transcript abundance can reach into the thousands per cell, the dynamic range associated with assessment of epigenomic features often ranges between 0 to ~2 reads per genomic locus per cell. Fundamentally, then, limiting input materials substantially blunts the dynamic range of assessment, a problem further magnified at the level single cell analysis. This problem also manifests itself as a fundamental limit to the complexity of the sequencing library – i.e. the number of unique fragments that can be sequenced. The library complexity per cell unit is often the most relevant figure of merit, along with sensitivity of signal-to-noise ratio to input amount, for small-sample epigenomic methods. Indeed, the complexity limitations inherent in small-sample assays make identification of reads originating from PCR duplicates (using methods such as molecular barcoding strategies64-67) all the more important.

Because of these issues of dynamic range and library complexity, substantial work remains for algorithm development that might take these relatively sparse data sets and extract maximally biologically meaningful insights from these promising methodologies. Alternately, this problem of dynamic range might be addressed by highly parallel methods for the probing of many individual cells, allowing per-cell technical noise to be combated by large numbers of observations. In short, the future of small-sample epigenomic analysis is bright, with a number of recent innovative methodological solutions poised to diffuse to the epigenomics community at large, unlocking exciting new directions of investigation.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Jason Buenrostro for critical reading, and Viviana Risca for components of the figures. The author acknowledges support as a Rita Allen Foundation Young Scholar, and as a Baxter Foundation Faculty Fellow, and NIH grant P50HG007735 and U19AI057266.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hansen KD, et al. Increased methylation variation in epigenetic domains across cancer types. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:768–775. doi: 10.1038/ng.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.1000 Genomes Project Consortium et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature . 2012;491:56–65. doi: 10.1038/nature11632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.John S, et al. Genome-scale mapping of DNase I hypersensitivity. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2127s103. Chapter 27, Unit 21.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park PJ. Epigenetics meets next-generation sequencing. Epigenetics-Us. 2008;3:318–321. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.6.7249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lara-Astiaso D, et al. Immunogenetics. Chromatin state dynamics during blood formation. Science. 2014;345:943–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1256271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith ZD, Meissner A. DNA methylation: roles in mammalian development. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spitz F, Furlong E. Transcription factors: from enhancer binding to developmental control. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nrg3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell O, Tiwari VK, Thomä NH, Schübeler D. Determinants and dynamics of genome accessibility. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2011;12:554–564. doi: 10.1038/nrg3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hargreaves DC, Crabtree GR. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling: genetics, genomics and mechanisms. Cell Res. 2011 doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Consortium EP. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature .. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landt SG, et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome research. 2012;22:1813–1831. doi: 10.1101/gr.136184.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valouev AA, et al. Determinants of nucleosome organization in primary human cells. Nature. 2011;474:516–520. doi: 10.1038/nature10002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaffney DJ, McVicker G, Pai AA, Fondufe-Mittendorf YN. Controls of nucleosome positioning in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bock C, et al. DNA methylation dynamics during in vivo differentiation of blood and skin stem cells. Molecular cell. 2012;47:633–647. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith ZD, et al. A unique regulatory phase of DNA methylation in the early mammalian embryo. Nature. 2012;484:339–344. doi: 10.1038/nature10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meissner A, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meissner A. Epigenetic modifications in pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1079–1088. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziller MJ, et al. Charting a dynamic DNA methylation landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2013;500:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mack SC, et al. Epigenomic alterations define lethal CIMP-positive ependymomas of infancy. Nature. 2014;506:445–450. doi: 10.1038/nature13108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hovestadt V, et al. Decoding the regulatory landscape of medulloblastoma using DNA methylation sequencing. Nature. 2014;510:537–541. doi: 10.1038/nature13268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neph S, et al. An expansive human regulatory lexicon encoded in transcription factor footprints. Nature. 2012;489:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neph S, et al. Circuitry and Dynamics of Human Transcription Factor Regulatory Networks. Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.John S, et al. Chromatin accessibility pre-determines glucocorticoid receptor binding patterns. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:264–268. doi: 10.1038/ng.759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stergachis AB, et al. Developmental fate and cellular maturity encoded in human regulatory DNA landscapes. Cell. 2013;154:888–903. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thurman RE, et al. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nature11232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miele A, Gheldof N, Tabuchi TM, Dostie J, Dekker J. Mapping chromatin interactions by chromosome conformation capture. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2006 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2111s74. Chapter 21, Unit 21.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lieberman-Aiden E, et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science. 2009;326:289–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1181369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Wit E, de Laat W. A decade of 3C technologies: insights into nuclear organization. Genes Dev. 2012;26:11–24. doi: 10.1101/gad.179804.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dekker J. The three ‘C’ s of chromosome conformation capture: controls, controls, controls. Nature methods. 2006;3:17–21. doi: 10.1038/nmeth823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanyal A, Lajoie BR, Jain G, Dekker J. The long-range interaction landscape of gene promoters. Nature. 2012;489:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature11279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dixon JR, et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. 2012;485:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature11082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ENCODE Project Consortium A user's guide to the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE). PLoS biology. 2011;9:e1001046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernstein BE, et al. The NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1045–1048. doi: 10.1038/nbt1010-1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song LL, Crawford GEG. DNase-seq: a high-resolution technique for mapping active gene regulatory elements across the genome from mammalian cells. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 20102010:pdb–prot5384. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furey TS. ChIP-seq and beyond: new and improved methodologies to detect and characterize protein-DNA interactions. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2012;13:840–852. doi: 10.1038/nrg3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meissner A, et al. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing for comparative high- resolution DNA methylation analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5868–5877. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bock C, et al. Quantitative comparison of genome-wide DNA methylation mapping technologies. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:1106–1114. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalisky T, Quake SR. Single-cell genomics. Nature methods. 2011;8:311–314. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0411-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nawy T. Epigenetics: Single-cell epigenetics. Nature methods. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu AR, et al. Automated microfluidic chromatin immunoprecipitation from 2,000 cells. Lab Chip. 2009;9:1365–1370. doi: 10.1039/b819648f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dahl JA, Collas P. A rapid micro chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (microChIP). Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1032–1045. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dahl JA, Collas P. MicroChIP--a rapid micro chromatin immunoprecipitation assay for small cell samples and biopsies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dahl JA, Reiner AH, Collas P. Fast genomic muChIP-chip from 1,000 cells. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-2-r13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adli M, Zhu J, Bernstein BE. Genome-wide chromatin maps derived from limited numbers of hematopoietic progenitors. Nature methods. 2010;7:615–618. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adli M, Bernstein BE. Whole-genome chromatin profiling from limited numbers of cells using nano-ChIP-seq. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:1656–1668. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goren A, et al. Chromatin profiling by directly sequencing small quantities of immunoprecipitated DNA. Nature methods. 2010;7:47–49. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shankaranarayanan P, Mendoza-Parra M-A, van Gool W, Trindade LM, Gronemeyer H. Single-tube linear DNA amplification for genome-wide studies using a few thousand cells. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:328–338. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shankaranarayanan P, et al. Single-tube linear DNA amplification (LinDA) for robust ChIP- seq. Nature methods. 2011;8:565–567. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zong C, Lu S, Chapman AR, Xie XS. Genome-wide detection of single-nucleotide and copy-number variations of a single human cell. Science. 2012;338:1622–1626. doi: 10.1126/science.1229164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lorthongpanich C, et al. Single-cell DNA-methylation analysis reveals epigenetic chimerism in preimplantation embryos. Science. 2013;341:1110–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.1240617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adey AA, Shendure JJ. Ultra-low-input, tagmentation-based whole-genome bisulfite sequencing. Genes Dev. 2012;22:1139–1143. doi: 10.1101/gr.136242.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Q, Gu L, Adey A, Radlwimmer B, Wang W. Tagmentation-based whole-genome bisulfite sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miura F, Enomoto Y, Dairiki R, Ito T. Amplification-free whole-genome bisulfite sequencing by post-bisulfite adaptor tagging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:e136. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guo H, et al. Single-cell methylome landscapes of mouse embryonic stem cells and early embryos analyzed using reduced representation bisulfite sequencing. Genome research. 2013;23:2126–2135. doi: 10.1101/gr.161679.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smallwood SA, et al. Single-cell genome-wide bisulfite sequencing for assessing epigenetic heterogeneity. Nature methods. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3035. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu C. The 5′ ends of Drosophila heat shock genes in chromatin are hypersensitive to DNase I. Nature. 1980;286:854–860. doi: 10.1038/286854a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu C. Two protein-binding sites in chromatin implicated in the activation of heat-shock genes. Nature. 1984;309:229–234. doi: 10.1038/309229a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hesselberth JR, et al. Global mapping of protein-DNA interactions in vivo by digital genomic footprinting. Nature methods. 2009;6:283–289. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA- binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nature methods. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zaret K. Micrococcal nuclease analysis of chromatin structure. Current protocols in molecular biology. 2005 doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2101s69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cui K, Zhao K. Genome-wide approaches to determining nucleosome occupancy in metazoans using MNase-Seq. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;833:413–419. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-477-3_24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nagano T, et al. Single-cell Hi-C reveals cell-to-cell variability in chromosome structure. Nature. 2013;502:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature12593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shiroguchi K, Jia TZ, Sims PA, Xie XS. Digital RNA sequencing minimizes sequence- dependent bias and amplification noise with optimized single-molecule barcodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:1347–1352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kivioja T, et al. Counting absolute numbers of molecules using unique molecular identifiers. Nature methods. 2012;9:72–74. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kinde I, Wu J, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Detection and quantification of rare mutations with massively parallel sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:9530–9535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105422108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fu GK, Hu J, Wang P-H, Fodor SPA. Counting individual DNA molecules by the stochastic attachment of diverse labels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:9026–9031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017621108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]