Abstract

Objectives

Caffeine is consumed by more than 85% of adults and little is known about its role on erectile dysfunction (ED) in population-based studies. We investigated the association of caffeine intake and caffeinated beverages with ED, and whether these associations vary among comorbidities for ED.

Material and Method

Data were analyzed for 3724 men (≥20 years old) who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). ED was assessed by a single question during a self-paced, computer-assisted self-interview. We analyzed 24-h dietary recall data to estimate caffeine intake (mg/day). Multivariable logistic regression analyses using appropriate sampling weights were conducted.

Results

We found that men in the 3rd (85-170 mg/day) and 4th (171-303 mg/day) quintiles of caffeine intake were less likely to report ED compared to men in the lowest 1st quintile (0-7 mg/day) [OR: 0.58; 95% CI, 0.37–0.89; and OR: 0.61; 95% CI, 0.38–0.97, respectively], but no evidence for a trend. Similarly, among overweight/obese and hypertensive men, there was an inverse association between higher quintiles of caffeine intake and ED compared to men in the lowest 1st quintile, P≤0.05 for each quintile. However, only among men without diabetes we found a similar inverse association (Ptrend = 0.01).

Conclusion

Caffeine intake reduced the odds of prevalent ED, especially an intake equivalent to approximately 2-3 daily cups of coffee (170-375 mg/day). This reduction was also observed among overweight/obese and hypertensive, but not among diabetic men. Yet, these associations are warranted to be investigated in prospective studies.

Introduction

In the US, the prevalence of erectile dysfunction (ED) in men aged ≥20 years is 18.4% suggesting that more than 18 million are affected [1, 2]. Among older men, these numbers significantly increase affecting their overall quality of life [3]: at age 40, approximately 44% are affected and this number increases nearly to 70% by age of 70 [2, 4]. The economic burden of ED is unclear, yet studies have shown that the cost of treatment could reach $15 billion if all men seek treatment [5, 6].

Cardiovascular risk factors like physical inactivity, alcohol consumption and smoking have been suggested to increase the risk of ED [7, 8]. Yet, little is known about other factors that could have a potential benefit on ED such as caffeine intake [9–12]. It was previously hypothesized that coffee and/or caffeine initiates a series of pharmacological effects that lead to the relaxation of the cavernous smooth muscle and that subsequently could improve ED [13]. Caffeine was recently reported to be consumed by more than 85% of US adults, and it is obtained mainly from dietary fluid sources, such as coffee, tea, soda, and energy/sport drinks. About two thirds of American adults drink coffee on a daily basis, 52% of the US male population drinks at least one glass of soda per day, while over 50% drinks tea on any given day, and 17% consumes energy and sport drinks more than three times per week [14]. Coffee, and its most studied component, caffeine, have been implicated in potential health benefits due to the rich sources of antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds contained in this beverage [14, 15].

The prevalence of overweight/obesity, hypertension and diabetes is increasing dramatically among US men, and previous studies have linked them with ED [16–20]. Yet, there is a paucity of research on the interplay between these comorbidities, caffeine intake and ED. Therefore, the aims of this study are to investigate the association of caffeine intake and caffeinated beverages with ED, and to compare whether these associations vary among overweight/obese, hypertensive and diabetic men in a nationally representative sample of the US adult population.

Methods

Study Population

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a program of studies undertaken by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the US. Continuous NHANES used a multistage, stratified and clustered probability sampling in which Mexican-Americans, non-Hispanic blacks, and the elderly were oversampled to ensure adequate samples sizes and to represent the total US civilian, non-institutionalized population [21]. For the purpose of this study, we combined data from continuous NHANES waves 2001–2002 and 2003–2004 because information on ED was reported only on those years.

Assessment of Erectile Dysfunction

NHANES participants were in a private room using self-paced audio computer-assisted self-interview system that enabled them to both hear questions through earphones and read questions on the computer related to ED. To assess erectile dysfunction, men (≥20 years) were asked the following question that has been previously validated and suggested to be added in large ongoing national epidemiologic surveys to provide needed information related to the prevalence of ED [22], “Many men experience problems with sexual intercourse. How would you describe your ability to get and keep an erection adequate for satisfactory intercourse? The following answers were provided, “would you say that you are… always or almost always able, usually able, sometimes able, or never able? For the purpose of this study, we defined and dichotomized positive ED from the answers “sometime able” or “never able” to keep an erection, and subsequently negative ED was derived from the answers “almost always able” or “usually able” to maintain an erection [2]. In this study we excluded men with the following conditions as they could influence the condition of ED: men who were diagnosed with prostate cancer (n = 94), or underwent surgery/radiation treatment (n = 85) for the same disease. We also excluded men with implausible daily calorie intakes (below 800 kcal or above 5,000 kcal) (n = 285) leaving a total sample size of 3,724 men with valid data on ED.

Assessment of caffeine and dietary data

The U.S. Department of Agriculture developed and validated a multiple-pass dietary recall method for NHANES to collect dietary data [23]. Participants reported all food and beverages consumed in two, 24-h dietary recall periods (midnight to midnight). The first one was conducted by dietary research interviewers face-to-face, and the second one was done 3 to 10 days later by telephone. Because NHANES 2001–2002 only included one recall, our analysis was limited to the first-day dietary recall for both NHANES waves 2001–2002 and 2003–2004, which is considered a population-based estimate of daily caffeine intake. After the dietary interviews, USDA’s Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies 5.0 (2012) was used to code dietary intake data and calculate nutrient intakes [23]. Based on the quantity of food and beverages reported and the corresponding nutrient contents by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), the caloric content and other nutrients derived from each consumed food and beverage item were calculated [23, 24]. Data on caffeine intake (mg/day), plain and tap water (gm), and alcohol (gm) was obtained from the Total Nutrient File, which contains summed nutrients for an individual from all food and beverages provided on the dietary recall [25]. Information on specific caffeinated beverages was obtained from the Individual Foods files [23]. We identified four beverages, coffee, total soda (regular and low-calorie), tea and energy and sport drinks, which were dichotomized (“Yes” / “No”) for their intake on any given day. We examined caffeine intake in quintiles (mg/day), lowest quintile (0–7), 2nd quintile (8–84), 3rd quintile (85–170), 4th quintile (171–303), and highest quintile (304–700). Total water intake categorized and defined by combining plain and tap water and it was included in multivariable models, while alcohol consumption was kept continuous.

Assessment of covariates

Age, race/ethnicity, smoking status, education and physical activity during the past 30 days (moderate and vigorous) were self-reported during the NHANES interview. NHANES categorizes race/ethnicity as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, and other (other Hispanics and all others). Participants were classified as never, former and current smokers from self-reported information; participants were asked if they had smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and if they were current smokers; serum cotinine was measured using high performance liquid chromatography/atmospheric-pressure ionization tandem mass spectrometry [26]. Current smokers consisted of those who self-reported smoking habits, smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, and cotinine was ≥ 10 ng/mL (actively exposed). Vigorous physical activity was obtained from the questions on whether participants did any activity that caused heavy sweating or large increases in breathing or heart rate (e.g., swimming, aerobics, or fast cycling), while moderate physical activity was determined from the questions on whether they did any activities that caused light sweating or a moderate increase in the heart rate, such as playing golf, dancing, bicycling for pleasure, or walking. Three readings of systolic and diastolic blood pressure were obtained from participants who attended the mobile examination center. We used the average of those three measurements (≥140/90 mmHg). We also considered the current use of antihypertensive medication treatment or being “told by a doctor you have hypertension” as an indication of high blood pressure (hypertension). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from measured weight and height (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared). Type 2 diabetes status was defined from ≥126 mg/dl of fasting plasma glucose, medication treatment or being “told by a doctor you have diabetes or sugar diabetes.” Fasting plasma glucose concentration was measured in the morning session after an overnight fast of at least 8 h [27], details related to the laboratory procedures of that is found elsewhere [21].

Statistical analysis

Sampling weights were applied to take into account selection probabilities, over-sampling, non-response, and differences between the sample and the total US population. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for ED using weighted logistic regression models were estimated in relation to quintiles of caffeine intake, binary variables of caffeinated beverages and its combinations. We did not attempt to classify “coffee plus tea” (or any of the beverage combinations) intake according to caffeine intake (mg/day) content due to missing information about specific beverage consumption, missing information on caffeine (mg/day), or discrepancy between caffeine (mg/day) values and reporting of specific beverage consumption. In “Model 1,” we only adjusted for age, while in “Model 2” we included the variables vigorous and moderate physical activity, age (continuous), smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap; continuous), total energy (continuous) and alcohol (continuous).

Stratified analyses were conducted by binary overweight/obesity (BMI ≥25 kg/m2), type 2 diabetes and hypertension because these variables are known to modify ED. Multivariable models included the variables vigorous and moderate physical activity, age, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, intake of total water, total energy, alcohol and obesity (removed when stratified by overweight/obesity). Statistical interaction tests were carried out by using the ordinal variables for caffeine intake, binary variables for caffeinated beverages, binary variables for the potentially modifying factors and their product terms. The statistical significance of the interaction terms was evaluated by the Wald test. All p-values were two-sided; alpha = 0.05 was considered the cut-off for statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 12.0 (College Station, TX).

Results

The distribution of baseline characteristics in the study population after applying samples weights is shown in Table 1. The mean age was 49 years, and the majority of the participants were white (54%). The prevalence of overweight and obesity based on BMI ≥25–29.99 and ≥30 kg/m2, respectively, was 40.9% and 30.7%. Fifty-one percent of the participants were hypertensive and 12.4% were diabetic. Twenty-six percent of the participants had some college and 24.7% had a high school diploma or GED equivalent, 34.6% were current smokers, 49.9% performed moderate physical activity, while a 64.7% reported a vigorous physical activity. Mean value for serum cotinine was 70.0 ng/mL, 1900.7 gm for total water intake, 2434.8 kcal for energy, 15.4 gm for alcohol and 188.3 mg/d for total caffeine intake. Caffeinated beverages showed 55.4% for coffee, 20.6% for tea, 58.5% for total soda, and 3.1% for energy and sport drinks.

Table 1. Selected characteristics of the US population of adult men 20 years or older, NHANES 2001–2004.

| Characteristics | Unweighted sample size | Mean or percentage (SE) † |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 3724 | 49.4 (18.4) |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||

| Mexican-American | 774 | 20.8 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 2016 | 54.1 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 689 | 18.5 |

| Other | 245 | 6.6 |

| Education, % | ||

| Less than 9th grade | 489 | 13.1 |

| 9th- 11th grade | 539 | 14.5 |

| High school grad / GED or equivalent | 920 | 24.7 |

| Some College or associate degree | 979 | 26.3 |

| College Graduate or above | 797 | 21.4 |

| Cigarette smoking, % | ||

| Never | 1371 | 36.8 |

| Former | 1063 | 28.6 |

| Current ‡ | 1287 | 34.6 |

| Serum cotinine, ng/mL | 3579 | 70.9 (137.3) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, % | ||

| <25 | 1040 | 28.4 |

| ≥25–29.99 | 1498 | 40.9 |

| ≥30 | 1124 | 30.7 |

| Type 2 Diabetes, % | ||

| No | 3263 | 87.6 |

| Yes | 461 | 12.4 |

| Hypertension, % | ||

| No | 1809 | 48.6 |

| Yes | 1911 | 51.4 |

| Physical Activity Status, % | ||

| Moderate | ||

| No | 1818 | 50.1 |

| Yes | 1816 | 49.9 |

| Vigorous | ||

| No | 1261 | 35.3 |

| Yes | 2316 | 64.7 |

| Total water intake, gm/day | 2113 | 1900.7 (2192.5) |

| Total energy, kcal/day | 3724 | 2434.8 (910.1) |

| Alcohol, gm/day | 3724 | 15.4 (35.6) |

| Total caffeine intake, mg/day | 3724 | 188.3 (246.6) |

| Coffee consumption, % | ||

| No | 1663 | 44.6 |

| Yes | 2061 | 55.4 |

| Tea consumption, % | ||

| No | 2956 | 79.4 |

| Yes | 768 | 20.6 |

| Total soda consumption, % | ||

| No | 1544 | 41.5 |

| Yes | 2180 | 58.5 |

| Energy and sport drinks, % | ||

| No | 3608 | 96.9 |

| Yes | 116 | 3.1 |

| Coffee plus tea, % | ||

| No | 1315 | 35.3 |

| Yes | 2409 | 64.7 |

| Coffee plus tea and soda, % | ||

| No | 404 | 10.9 |

| Yes | 3320 | 89.1 |

| Coffee plus tea, soda, and energy and sport drinks, % | ||

| No | 381 | 10.2 |

| Yes | 3343 | 89.7 |

SE: standard error

†Sampling weights were applied

‡Self-reported smoking habits, smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime, and cotinine was ≥ 10 ng/mL (actively exposed).

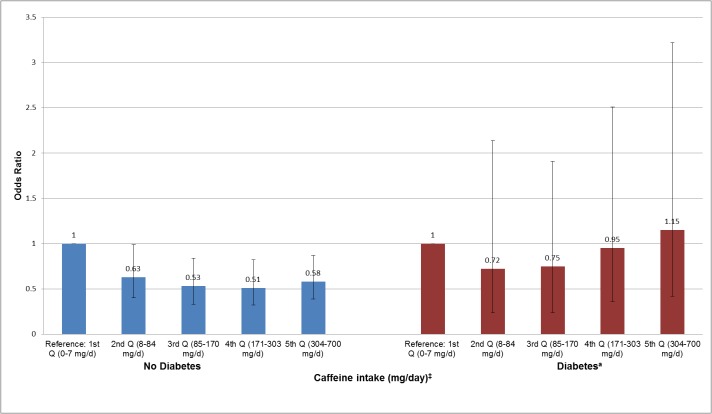

In Fig 1, after adjusting for vigorous and moderate physical activity, age, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity, total water intake, total energy, and alcohol, we found that men in the 3rd quintile (85-170mg/day) and 4th quintile (171–303 mg/day) of total caffeine intake were less likely to report ED compared to men in the 1st quintile (0–7 mg/day) [OR: 0.58; 95% CI, 0.37–0.89; and OR: 0.61; 95% CI, 0.38–0.97, respectively]. Yet, we did not find a trend in this association (P trend = 0.19).

Fig 1. Association of caffeine intake with erectile dysfunction in NHANES 2001–2004 (n = 3724).

†Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. P trend = 0.19. *Erectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. ‡Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee.

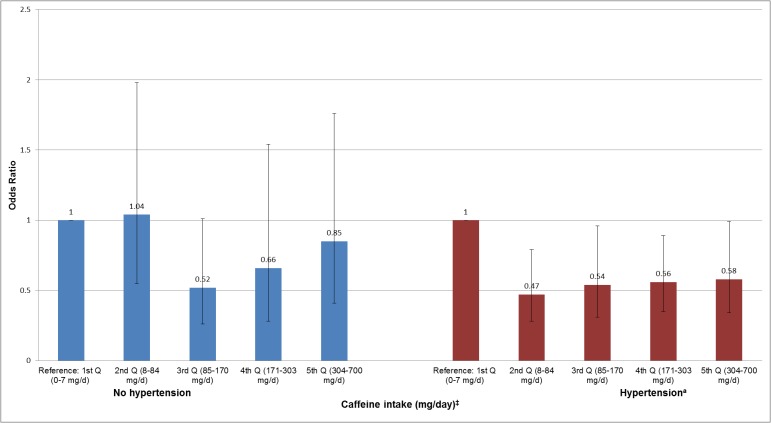

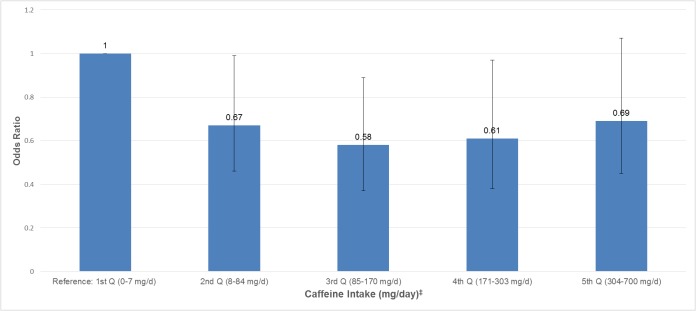

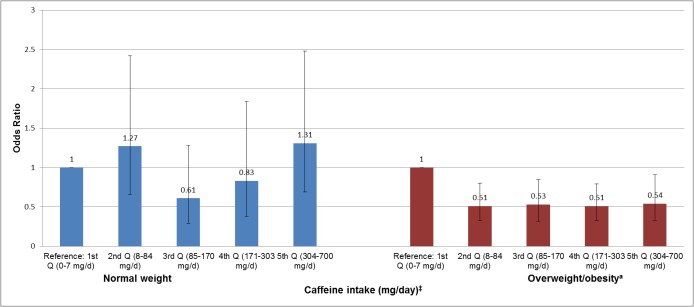

In stratified analyses, we investigated the associations of total caffeine intake with ED among overweight/obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), hypertensive and diabetic men (Figs 2–4). We did not find any significant association among men with normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2), normal blood pressure, and diabetes. However, among overweight/obese and hypertensive men, we found that men in the 2nd (8–84 mg/day), 3rd (85–170 mg/day), 4th (171–303 mg/day) and 5th (304–700 mg/day) quintiles of total caffeine intake had a reduced prevalence of ED than men in the lowest quintile (0–7 mg/day) (P ≤ 0.05 for each quintile) (Figs 2 and 3). Yet, there was no evidence for a statistically significant trend (P trend ≥ 0.05) and interaction effect (P interaction ≥ 0.05) for any of the associations. Among men without diabetes (Fig 4), we found that men in every caffeine intake quintile reported a lower likelihood of prevalent ED showing a significant trend for this association (P trend = 0.01). Yet, the interaction effect did not reach statistical significance (P interaction = 0.65). The association of caffeine intake with ED was also analyzed in age categories (20–39, 40–49, 50–59, and ≥60 years old), however, no statistical significant associations were found (data not shown).

Fig 2. Association of caffeine intake with erectile dysfunction among normal weight and overweight/obese men in NHANES 2001–2004.

†Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. P trend = 0.08 and P interaction = 0.09. *Erectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. ‡ Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. aOverweight/obesity = body mass index ≥ 25 kg/m2.

Fig 4. Association of caffeine intake with erectile dysfunction among men with and without diabetes in NHANES 2001–2004.

†Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. P trend = 0.57 and P interaction = 0.65. *Erectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. ‡ Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. aDiabetes = fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dl, self-reported diagnosis, or medication treatment.

Fig 3. Association of caffeine intake with erectile dysfunction among men with and without hypertension in NHANES 2001–2004.

†Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. P trend = 0.13 and P interaction = 0.30. *Erectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. ‡ Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. aHypertension = systolic/diastolic blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, self-reported diagnosis, or medication treatment.

We also analyzed the association of caffeinated beverages with ED and whether these associations varied by comorbidities for ED. The results are presented in an Online Supplement (S1–S4 Tables). In general, we found few significant, but inconclusive, associations between caffeinated beverages, and its combinations, with ED (S1–S4 Tables).

Discussion

In the present study, our nationally representative sample of men showed that total caffeine intake was associated with a reduced likelihood to report ED in multivariable analyses. This reduced prevalence of ED was mainly observed when the amount of caffeine intake was between 170 and 375 mg/day, which is approximately equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee per day. In addition, total caffeine intake seemed to reduce the odds of ED among men who were overweight/obese, hypertensive and non-diabetic. A few caffeinated beverages were inversely associated with ED, yet they were not consistent when stratified by comorbidities for ED.

Our results are consistent with two population-based studies that showed an inverse association between caffeine intake and ED [9, 10]. The suggested biological mechanism [20] is that caffeine triggers a series of pharmacological effects that lead to the relaxation of the penile helicine arteries, and the cavernous smooth muscle that lines cavernosal spaces, thus increasing penile blood flow [13].

However, our findings differ from two previous studies that showed no association between caffeinated drinks (cross-sectional), coffee consumption (prospective) and ED [11, 12]. Compared to these null studies, our study had a larger sample size for the endpoint of interest. In addition, our exposures (total caffeine intake and caffeinated beverages) were derived from a 24-hour dietary recall period, which method has been developed and validated by the US Department of Agriculture to report population-based estimates of daily caffeine intake. Plus, our multiple linear regression models included more confounders, total water intake and total energy, that could possibly mask an association between caffeine intake and ED.

We did not find a significant inverse association between caffeine intake and ED among diabetic men. In an animal study, we previously showed that caffeine consumption improved the erectile function of diabetic rats by up-regulating cavernous cGMP [20]. Diabetes is one of the strongest risk factors for ED and it remains one of the most difficult medical conditions to treat [28]. Thus, it is possible this is one of the reasons we couldn’t find lower prevalence of ED among men with higher intake of caffeine.

Interestingly, our findings showed a lower prevalence of ED among men with caffeine intake, especially when this is equivalent to 2–3 daily cups of coffee (170–375 mg/day). Previously, a similar caffeine intake amount was associated with beneficial effects on cardiometabolic factors and cardiovascular health [14]. In addition, a recent study reported that American men age 35 to 54 years had a caffeine intake of 336 mg per day, which is close to the amount of caffeine we found having a significantly inverse association with ED [29]. Our findings with caffeinated beverages, or its combination, did not follow a consistent pattern as we observed with total caffeine intake (mg/day). Yet, it is possible that due to its collection (consumption on any given day) and dichotomization (“Yes” / “No”) contributed to the inconsistent results we found.

Strengths of this study is the large sample size with a representative sample of the US men population, and the validated dietary recall methodology from NHANES that allows for measurement of caffeine intake from drinks [23, 24] and report population-based estimates of daily caffeine intake. Yet, our study also has limitations; ED is a multifactorial disease and some of its risk factors were not addressed in this study such as cardiovascular diseases; NHANES is a cross-sectional study, therefore, the association we found between caffeine intake and ED impede us to infer causality or much less suggest any clinical practice change. Plus, there is an inherent bias in the use of surveys for data collection. Thus, these findings should be confirmed in prospective studies.

Conclusion

In general we found a reduced likelihood to report ED among men with caffeine intake, especially with 2–3 daily cups of coffee, which is approximately 170–375 mg/day. Interestingly, we found differences in the inverse associations of caffeine intake and caffeinated beverages among overweight/obese, non-diabetic and hypertensive men.

Supporting Information

βErectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. †Model 1- Adjusted for age only. ‡Model 2- Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). £ Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. a P ≤ 0.05 b P ≤ 0.01

(DOC)

βErectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. ‡Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). £Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. a P ≤ 0.05 b P ≤ 0.01

(DOC)

βErectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. ‡Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). £Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. a P ≤ 0.05 b P ≤ 0.01

(DOC)

βErectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. ‡ Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). £Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. a P ≤ 0.05 b P ≤ 0.01

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

Dr. David S. Lopez was supported by the Division of Urology- The University of Texas- Medical School at Houston.

Data Availability

Data cannot be made publicly available by the authors, because they were obtained from the third party NHANES. The authors used data from two NHANES waves in this study: 2001-2002 and 2003-2004. Datasets can be found in the two folders, “Questionnaire” and “Dietary.” These datasets are freely available at the following URLs: http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/nhanes01_02.aspx; http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/nhanes03_04.aspx.

Funding Statement

Dr. David S. Lopez was supported by the Division of Urology—The University of Texas- Medical School at Houston. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Lue TF (2000). Erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med 342:1802–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA (2007). Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. Am J Med 120:151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Francis ME, Kusek JW, Nyberg LM, Eggers PW (2007). The contribution of common medical conditions and drug exposures to erectile dysfunction in adult males. J Urol 178:591–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guay AT, Spark RF, Bansal S, Cunningham GR, Goodman NF, Nankin HR, et al. (2003). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the evaluation and treatment of male sexual dysfunction: a couple's problem—2003 update. Endocr Pract 9:77–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wessells H, Joyce GF, Wise M, Wilt TJ (2007). Erectile dysfunction. J Urol 177:1675–1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Laumann EO, Waite LJ (2008). Sexual dysfunction among older adults: prevalence and risk factors from a nationally representative U.S. probability sample of men and women 57–85 years of age. J Sex Med 5:2300–2311. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00974.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shamloul R, Ghanem H (2013). Erectile dysfunction. Lancet 381:153–165. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60520-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Janiszewski PM, Janssen I, Ross R (2009). Abdominal obesity and physical inactivity are associated with erectile dysfunction independent of body mass index. J Sex Med 6:1990–1998. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01302.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Diokno AC, Brown MB, Herzog AR (1990). Sexual function in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 150:197–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Akkus E, Kadioglu A, Esen A, Doran S, Ergen A, Anafarta K, et al. (2002) Prevalence and correlates of erectile dysfunction in Turkey: a population-based study. Eur Urol 41:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Berrada S, Kadri N, Mechakra-Tahiri S, Nejjari C (2003) Prevalence of erectile dysfunction and its correlates: a population-based study in Morocco. Int J Impot Res 15 Suppl 1:S3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shiri R, Koskimaki J, Hakama M, Hakkinen J, Huhtala H, Tammela TLJ, et al. (2004) Effect of life-style factors on incidence of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 16:389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Adebiyi A, Adaikan PG (2004). Effect of caffeine on response of rabbit isolated corpus cavernosum to high K+ solution, noradrenaline and transmural electrical stimulation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 31:82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Keefe JH, Bhatti SK, Patil HR, DiNicolantonio JJ, Lucan SC, Lavie CJ (2013) Effects of habitual coffee consumption on cardiometabolic disease, cardiovascular health, and all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol 62:1043–1051. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.06.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Leon-Carmona JR, Galano A (2011) Is caffeine a good scavenger of oxygenated free radicals? J Phys Chem B 115:4538–4546. 10.1021/jp201383y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH (2009) The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 9:88 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang Q, Wang Y, Huang ES (2009) Changes in racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of Type 2 diabetes by obesity level among US adults. Ethn Health 14:439–457. 10.1080/13557850802699155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martin SA, Atlantis E, Lange K, Taylor AW, O'Loughlin P, Wittert GA, et al. (2014) Predictors of sexual dysfunction incidence and remission in men. J Sex Med 11:1136–1147. 10.1111/jsm.12483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walsh TJ, Hotaling JM, Smith A, Saigal C, Wessells H. Men with diabetes may require more aggressive treatment for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res 26: 112–5. 10.1038/ijir.2013.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yang R, Wang J, Chen Y, Sun Z, Wang R, Dai Y (2008) Effect of caffeine on erectile function via up-regulating cavernous cyclic guanosine monophosphate in diabetic rats. J Androl 29:586–591. 10.2164/jandrol.107.004721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Center for Health Statistics 1994. Plan and operation of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–94. Series 1: programs and collection procedures. Vital Health Stat 1: 1–407. 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Donnell AB, Araujo AB, Goldstein I, McKinlay JB (2005). The validity of a single-question self-report of erectile dysfunction. Results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Gen Intern Med 20:515–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahuja JK, Montville JB, Omolewa-Tomobi G, Heendeniya KY, Martin CL, Steinfeldt LC, et al. (2012) USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies, 5.0. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Food Surveys Research Group, Beltsville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bleich SN, Wang YC, Wang Y, Gortmaker SL (2009) Increasing consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages among US adults: 1988–1994 to 1999–2004. Am J Clin Nutr 89:372–381. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2001–2004 Data documentation, codebook, and frequencies. Dietary interview: total nutrient intakes—first day. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2001-2002/DRXTOT_B.htm. Accessed November, 2013.

- 26. Bernert JT, Turner WE, Pirkle JL, Sosnoff CS, Akins JR, Waldrep MK, et al. (1997) Development and validation of sensitive method for determination of serum cotinine in smokers and nonsmokers by liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem 43:2281–2291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ford ES, Giles WH (2003). A comparison of the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome using two proposed definitions. Diabetes Care 26:575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moore CR, Wang R (2006). Pathophysiology and treatment of diabetic erectile dysfunction. Asian J Androl 8:675–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frary CD, Johnson RK, Wang MQ (2005). Food sources and intakes of caffeine in the diets of persons in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc 105:110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

βErectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. †Model 1- Adjusted for age only. ‡Model 2- Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). £ Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. a P ≤ 0.05 b P ≤ 0.01

(DOC)

βErectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. ‡Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). £Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. a P ≤ 0.05 b P ≤ 0.01

(DOC)

βErectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. ‡Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). £Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. a P ≤ 0.05 b P ≤ 0.01

(DOC)

βErectile dysfunction was defined as “sometimes” or “never” able to maintain an erection for satisfactory sexual intercourse. ‡ Adjusted for age, vigorous and moderate physical activity, smoking status, education, race/ethnicity, obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), total water intake (plain and tap), total energy (continuous), alcohol (continuous). £Approximately 170–375 mg/day of caffeine intake is equivalent to 2–3 cups of coffee. a P ≤ 0.05 b P ≤ 0.01

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

Data cannot be made publicly available by the authors, because they were obtained from the third party NHANES. The authors used data from two NHANES waves in this study: 2001-2002 and 2003-2004. Datasets can be found in the two folders, “Questionnaire” and “Dietary.” These datasets are freely available at the following URLs: http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/nhanes01_02.aspx; http://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/search/nhanes03_04.aspx.