Abstract

Background

This study examines whether concomitant methotrexate (MTX) use is associated with better biologic persistence and whether self-administered anti-TNF therapies are used at reduced doses in real-world clinical care settings, not just clinical trials.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study among RA patients using Medicare claims data from 2006 to 2012. Subjects were new initiators of etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, abatacept and tocilizumab with at least 12 months of continuous medical and pharmacy coverage after treatment initiation. We examined the association between concomitant MTX use and persistence on biologics using Cox proportional hazard regression adjusting for demographics and baseline co-morbidities. We further identified a subgroup of patients who initiated and were adherent on etanercept or adalimumab for at least 12 months and examined the proportion of patients who subsequently used these therapies at reduced doses continuously for an additional 12, 18, and 24 months.

Results

Of 26,510 eligible RA patients, 10,511 initiated biologic monotherapy. Overall, patients initiated biologic monotherapy were 1.4 (95% CI, 1.3–1.5) times more likely to discontinue at 1-year and 1.8 (95% CI, 1.7–2.0) times more likely if starting infliximab monotherapy. Approximately 10–20% of patients who initiated and adhered to etanercept and adalimumab for ≥ 12 months subsequently used reduced-dose therapy for an 12 additional months and beyond.

Conclusion

In real-world practice, concomitant MTX was associated with improved persistence on biologic therapy, especially for infliximab users; reduced-dose injectable anti-TNF therapy was used by a substantial proportion of RA patients.

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Biologic Persistence, Concomitant Methotrexate, Low-dose Biologic

Introduction

Methotrexate (MTX) is recommended and widely prescribed as the first-line, evidence-based therapy for newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients [1]. For example, data from the Treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid arthritis study showed that MTX monotherapy produced adequate clinical response in up to 30% of recently diagnosed RA patients with high disease activity who were able to achieve low disease activity (DAS28ESR < 3.2) within 6 months[2, 3]. For those with inadequate treatment response to MTX, biologics or multiple non-biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) used in combination with MTX achieve greater clinical efficacy compared to MTX monotherapy [4, 5] and to biologic monotherapy with anti-TNF agents [6, 7] in clinical trials. When used in combination, MTX not only exerts its independent clinical effect but also works synergistically to improve clinical efficacy of monoclonal antibodies, including infliximab and adalimumab, perhaps by suppressing the immunogenicity of these agents and increasing their serum drug levels[6, 8, 9]. Despite these benefits of MTX, we have previously shown that up to one-third of RA patients enrolled in the U.S. Medicare program receive biologic monotherapy[10]. This is consistent with multiple other U.S. and international reports showing between one-fourth and one-third of RA patients receiving biologics as monotherapy [11]. How biologic monotherapy administered not in conjunction with MTX impacts outcomes in real world settings (outside the confines of poorly generalizable randomized controlled trials) among RA patients is unknown.

On the other end of the clinical spectrum, the possibility that biologics might be given at reduced doses to patients doing well (e.g. in remission, or at least low disease activity) is potentially attractive. Indeed, given high costs, tolerability of weekly or bi-monthly injections, and adverse events associated with biologics, use of biologics at reduced doses might be an attractive alternative. A recently-published randomized controlled-trial (RCT) demonstrated that 25 mg etanercept with MTX produced similar clinical response compared to 50 mg etanercept with MTX, the conventional dose of etanercept for RA [12]. There are limited data from routine care settings on the frequency that subcutaneously injected anti-TNF therapies are used at reduced doses compared to the manufacturer recommended doses.

The present study had two aims: 1) to evaluate the association between concomitant MTX use and persistence with biologics; and 2) to examine the use of etanercept and adalimumab at reduced doses (doses lower than the manufacturer-recommended dose) among older RA patients in real world clinical practice in the U.S.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using 100% of Medicare administrative claims data from 2006 to 2012 among beneficiaries diagnosed with RA. Medicare is a U.S. public health plan that insures individuals 65 years of age or older, or younger individuals with certain disabilities (including RA, under certain circumstances) or End-Stage Renal Disease. It provides coverage for care received in hospitals (Part A), in doctor’s offices or outpatient settings (Part B), and prescription medications (Part D) for more than 90% of all U.S. population that are 65 or older [13]. Eligible patients were required to satisfy the following inclusion criteria: 1) initiated etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, abatacept, or tocilizumab after a 12 month ‘baseline’ period free of that agent (but who could have other biologics during that period); 2) had at least two RA diagnoses from a rheumatologist that were at least 7 days apart during the baseline period, and 3) were enrolled in Medicare Part A, Part B, and Part D and not in a Medicare Advantage plan during the baseline period and in the 12 months after treatment initiation. Follow-up started on the date of biologic initiation (defined as the index date) and ended when patients lost Medicare Part A, Part B, or Part D, enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan, died, or at December 31, 2012. These enrollment requirements ensured a complete claims history and records of filled prescriptions.

To examine the use of injectable biologics at reduced doses (Aim 2), we applied additional eligibility criteria: analyses were restricted to patients who initiated either etanercept or adalimumab and were both adherent and persistent (defined below) for at least 12 months. The purposes of these restrictions were to exclude patients who stopped early due to insufficient clinical response or due to safety/tolerability concerns and to identify patients who had been treated long enough that they may have achieved sufficient clinical response such that reduced dosing might be considered appropriate. Golimumab and certolizumab, or newer biologic agents, were not used with a high enough prevalence to contribute to this analysis.

Medication exposure

Exposure to biologics and non-biologic DMARDs (MTX, auranofin, azathioprine, chloroquine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, gold, hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, mercaptopurine, minocycline, mycophenolate, penicillamine, sulfasalazine) was determined based on records of filled prescriptions identified using national drug codes (NDC) for pharmacy-filled medications or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes for infused medications. Abatacept use immediately after approval but prior to assigning of the specific HCPCS code was identified using a validated algorithm developed for use in Medicare data [14], which utilizes non-specific HCPCS codes, RA diagnosis code, number of units dispensed, and submitted or allowable per-unit costs.

For Aim 1, concomitant MTX use was defined as having at least one filled prescription for MTX within 120 days both before and after initiation of biologic therapy, regardless of whether other types of non-biologic DMARD were used. Biologic monotherapy was defined as having no filled prescription for MTX or any other non-biologic DMARDs within the first 120 days after biologic initiation. This definition resulted in the exclusion of patients who concurrently initiated both MTX and biologics at approximately the same time, given that this was expected to be uncommon.

Study outcomes

Persistence, the study outcome for Aim 1, was defined as staying on the biologic therapy without discontinuation or switching to a different biologic. Start of follow-up for the analysis of this outcome began 120 days after the date of biologic initiation in order to identify MTX in this period of time and appropriately categorize patients as biologic monotherapy or combination therapy users. Discontinuation (i.e. non-persistence) was defined by having a >= 90 day gap after the end of the days’ supply, computed from the days supply dispensed or usual dosing interval (i.e. every 8 weeks for infliximab, every 4 weeks for abatacept and tocilizumab). Patients who initiated biologic monotherapy were censored if they added any non-biologic DMARD to their treatment regimen; likewise patients who initiated a combination therapy of biologic with concomitant MTX were censored if they discontinued MTX, using the same definition for persistence as described above.

For Aim 2, we required eligible patients to remain persistent with biologic therapy for 12 months after the index date, and also to have high adherence during this same 12 months, after which follow-up began. High adherence during this 12 month period was defined as a proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥ 80% [15]. We then examined the use of biologics at reduced doses, defined as a PDC < 80%, as compared with manufacturer-recommended dosing (etanercept: 50 mg/week; adalimumab: 40 mg/2 weeks). In a sensitivity analysis, we used a PDC < 70% to defined reduced dose biologics. To help interpret these proportions by way of example, a patient who skipped 1 out of every 4 doses of weekly etanercept would have a PDC = 75%; a patient who lengthened their adalimumab injections from 14 to every 21 days would have a PDC = 66%.

Statistical analysis

For Aim 1, we examined the distribution of patient characteristics measured at the start of follow-up. We plotted Kaplan Meier curves to compare persistence on therapy by the use of concomitant MTX and across 5 different biologics. We used Cox regression to calculate the unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for non-persistence of biologic therapy for users of monotherapy versus combination therapy, overall and separately for users of each biologic agent. We tested for an interaction between persistence and each specific biologic with concomitant MTX use. We adjusted for age, gender, race, receipt of state subsidy (as a proxy for low income), the original reason for enrollment into Medicare (e.g. age >= 65, disability), and factors measured during the baseline period that included the Charlson co-morbidity index and hospitalization (any and for infection), and stratified by the number of prior biologics. We allowed patients to contribute more than one biologic treatment episode and adjusted for clustering using sandwich estimation [16].

For Aim 2, to examine the use of injectable biologics at reduced dose, we divided follow-up time (which began 12 months after initiation of the biologic, during which patients were required to be persistent and adherent) into 6-month intervals and identified patients who remained persistent on their biologic at the end of each interval. Within each interval for these patients, we calculated the PDC as the proportion of days where the patient had drug available, divided by the 183 days in the interval. We examined the proportion of patients who used biologics at reduced doses for 12, 18, and 24 additional and consecutive months. We stratified patients by the length of follow-up available in the data. The purpose of the requirement that a patient must have remained persistent with the biologic at the end of the interval was to ensure that the measurement of reduced dose therapy was not an artifact of measurement among people who had recently discontinued.

All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The study protocol was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board. Data Use Agreements from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) governed use of the data.

Results

A total of 26,510 RA patients were included in the study and remained on their biologics through the first 120 days; 10,511 initiated biologic monotherapy and 15,999 initiated a biologic in combination with MTX. At treatment initiation, mean age (standard deviation) was 66.0 (12.2) and 82.0% were women. At follow-up start, patient characteristics were compared between those using monotherapy or combination therapy. In general, patients who initiated biologic monotherapy had more comorbidities, were more likely to be hospitalized, and more likely to use oral glucocorticoids (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of patient baseline characteristics by treatment regimen, measured at the start of follow-up

| Biologic Combination (with MTX regardless of other non-biologic DMARDs) |

Biologic Monotherapy (no MTX or other non-biologic DMARDs) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABA | ADA | ETA | INF | TOC | ABA | ADA | ETA | INF | TOC | |

| Patients, n | 4,143 | 2,919 | 2,704 | 5,571 | 662 | 3,575 | 1,934 | 2,039 | 2,238 | 725 |

| Age, mean | 68.5 | 62.0 | 63.0 | 68.6 | 66.6 | 68.3 | 61.5 | 62.2 | 67.5 | 66.7 |

| Female, % | 84.0 | 82.3 | 83.6 | 79.4 | 83.4 | 84.0 | 81.5 | 81.0 | 79.2 | 86.3 |

| Race, % | ||||||||||

| White | 85.6 | 73.0 | 75.6 | 85.3 | 87.0 | 85.0 | 73.2 | 75.8 | 80.9 | 85.9 |

| Black | 7.7 | 15.0 | 13.2 | 8.7 | 5.7 | 8.5 | 14.6 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 6.8 |

| Other | 6.7 | 12.0 | 11.2 | 6.0 | 7.3 | 6.5 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 8.1 | 7.3 |

| State Assistance with Medicare Premiums | 27.2 | 62.2 | 56.6 | 24.6 | 24.8 | 28.1 | 61.0 | 57.1 | 31.0 | 28.6 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||||||

| Charlson co-morbidity index[35] | ||||||||||

| ≤1 | 75.6 | 74.8 | 75.4 | 77.1 | 77.2 | 68.3 | 71.2 | 71.6 | 69.1 | 67.7 |

| 2 | 14.4 | 14.8 | 13.9 | 13.6 | 11.9 | 16.0 | 14.3 | 14.7 | 15.9 | 16.8 |

| ≥3 | 11.0 | 10.4 | 10.6 | 9.3 | 10.9 | 15.7 | 14.5 | 13.7 | 15.0 | 15.5 |

| Hospitalization, any, % | 26.6 | 22.6 | 24.4 | 20.9 | 25.5 | 32.0 | 29.8 | 30.5 | 28.7 | 30.9 |

| Hospitalized infection, % | 9.5 | 6.6 | 8.5 | 6.5 | 7.6 | 12.3 | 10.7 | 11.7 | 10.2 | 12.8 |

| Prior biologic use, any, % | 61.1 | 35.8 | 26.7 | 18.2 | 84.1 | 61.9 | 46.9 | 32.6 | 227.2 | 80.3 |

| Other non-biologic DMARD use, any, % | 35.0 | 39.7 | 42.1 | 36.6 | 30.7 | 28.9 | 30.9 | 34.1 | 31.6 | 27.6 |

| Glucocorticoid use, mean daily dose in prior 6 months, % | ||||||||||

| None | 39.3 | 40.8 | 36.7 | 38.1 | 39.4 | 40.3 | 44.4 | 43.9 | 42.6 | 41.7 |

| ≤7.5 mg/d | 46.6 | 45.1 | 47.2 | 47.2 | 43.5 | 45.7 | 41.8 | 41.2 | 44.1 | 42.7 |

| >7.5 mg/d | 14.1 | 14.1 | 16.2 | 14.7 | 17.1 | 14.1 | 13.8 | 14.9 | 13.3 | 15.6 |

ABA = Abatacept; ADA = adalimumab; ETA = etanercept; INF = infliximab; TOC = tocilizumab.

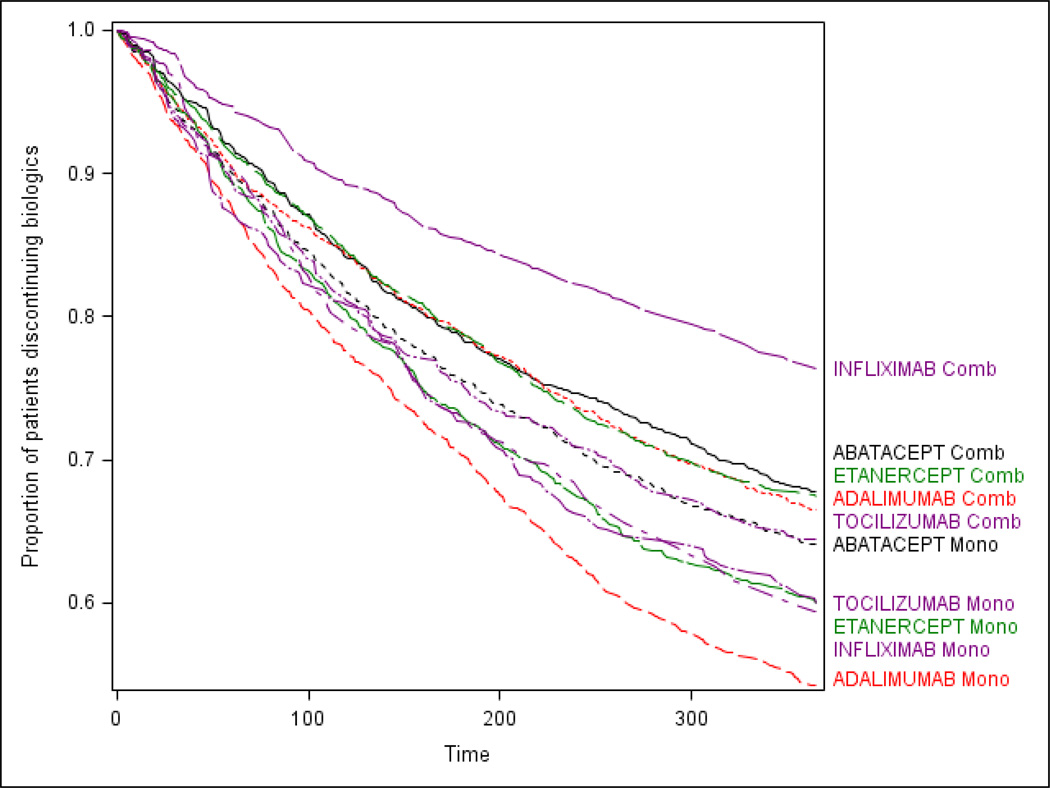

For all biologics examined, RA patients treated with monotherapy were more likely be non-persistent compared to those who initiated the same drug as combination therapy (overall HR for non-persistence: 1.4, 95% CI: 1.3–1.5) [Table 2, middle column, bottom row]. The association between use of concomitant MTX and biologic persistence differed significantly by biologic agent (test for interaction p < .0001). The strongest association was observed for infliximab mono-therapy compared to infliximab + MTX users (HR: 1.8; 95% CI: 1.7–2.0). A significant difference between mono and combination therapy was not observed for abatacept (HR: 1.1; 95% CI: 1.0–1.2) or for tocilizumab users (HR: 1.1; 95% CI: 0.9–1.3). Comparing across different drugs (Table 2, right column), patients on infliximab and MTX combination therapy had the highest persistence, and patients on adalimumab monotherapy had the least. The corresponding survival curve is shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

The association between non-persistence and combination biologic therapy versus monotherapy***

| Treatment regimen |

# Patients |

HR and 95% CI* for each specific biologic§ |

HR and 95% CI between different biologics‡ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abatacept | |||

| Combination | 4,143 | Reference | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) |

| Monotherapy | 3,575 | 1.1 (1.0–1.2) | 1.6 (1.4–1.7) |

| Adalimumab | |||

| Combination | 2,919 | Reference | 1.5 (1.3–1.6) |

| Monotherapy | 1,934 | 1.5 (1.3–1.6) | 2.1 (1.9–2.4) |

| Etanercept | |||

| Combination | 2,704 | Reference | 1.4 (1.3–1.6) |

| Monotherapy | 2,039 | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 1.8 (1.7–2.0) |

| Infliximab | |||

| Combination | 5,571 | Reference | Reference |

| Monotherapy | 2,238 | 1.8 (1.7–2.0) | 1.9 (1.7–2.1) |

| Tocilizumab | |||

| Combination | 662 | Reference | 1.4(1.2–1.7) |

| Monotherapy | 725 | 1.1(0.9–1.3) | 1.6(1.4–2.9) |

| Overall | |||

| Combination | 15,999 | Reference | N/A |

| Monotherapy | 10,511 | 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | N/A |

Note: the middle column provides within-drug comparisons, and the right column provides between-drug comparisons

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, Confidence interval, adjusting for age, gender race, receipt of state subsidy, Charlson co-morbidity index, hospitalization (any and for infection)

Cox regression analyses comparing monotherapy versus combination therapy (2 comparison groups) among all patients and within subgroups of patients by type of biologic

Cox regression analyses comparing non-persistence by type of biologic and by monotherapy versus combination therapy (4×2=8 comparison groups) among all patients

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plot of time to discontinuation by type of biologic therapy and use of concomitant methotrexate

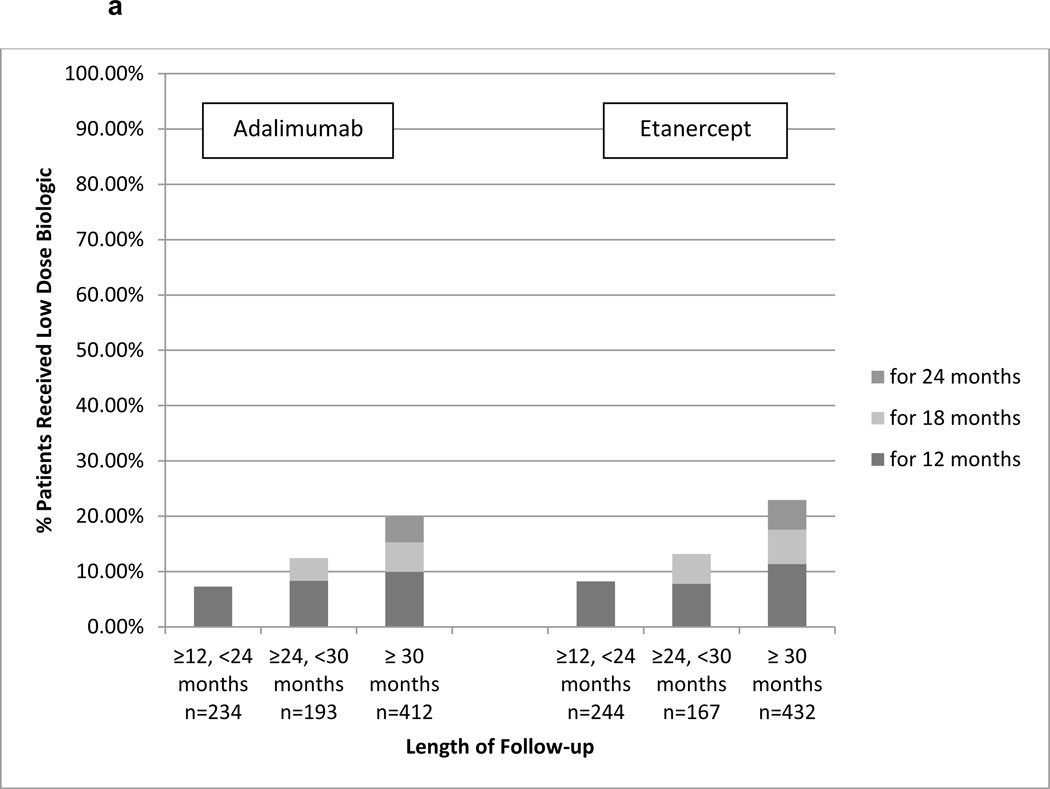

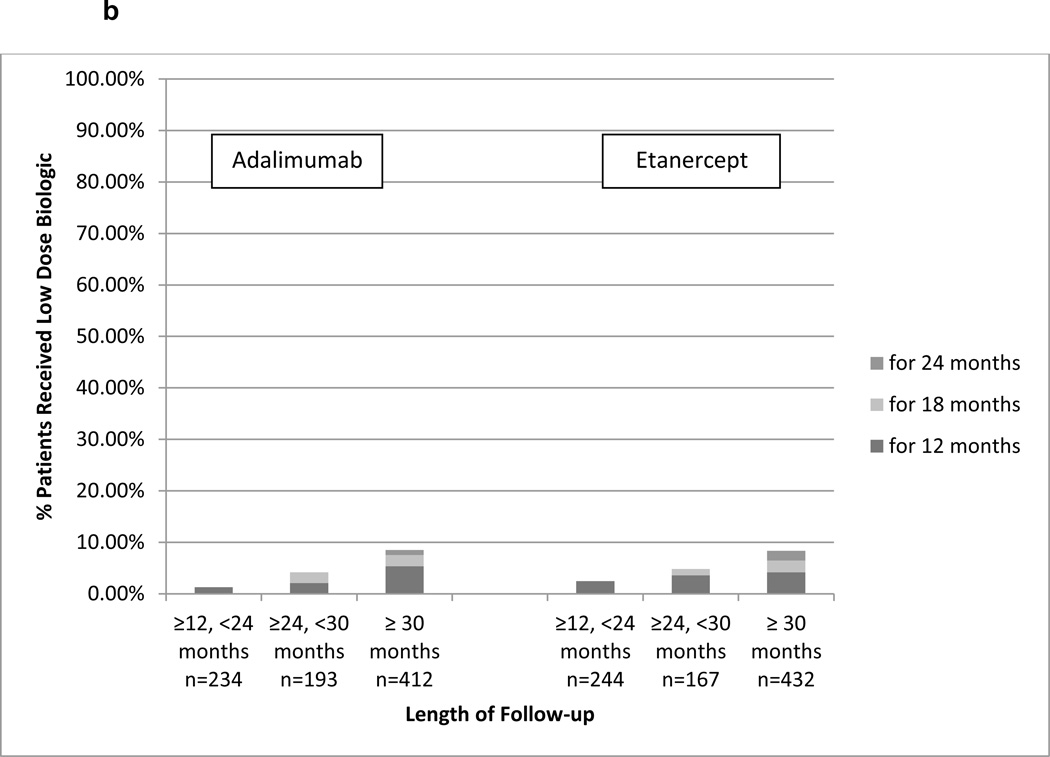

For Aim 2, we identified 3,773 RA patients who initiated etanercept or adalimumab and remained persistent for at least 12 months and were adherent with PDC ≥ 80%. Of these, 1,870 initiated etanercept, 1,903 initiated adalimumab, and 1,682 were persistent for at least another 12 months to contribute data to the analysis. Within 120 days prior to start of follow-up (follow-up started 12 months after treatment initiation), 64.7% of the patients had at least one filled prescription for a non-biologic DMARD. Depending on the length of follow-up available, approximately 10%–20% of patients who remained on etanercept used reduced-dose therapy (Figure 2a). Among adalimumab users, the corresponding proportions were similar although numerically lower. In the sensitivity analysis that used a more stringent definition for reduced dose (PDC < 70%), approximately 5–6% of patients used reduced therapy (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

a. Proportion of RA Patients Who Continuously Used Reduced Dose Injectable Etanercept or Adalimumab By Length of Follow-up (<80% days covered)

a presents data among adherent patient defined as having PDC≥80% for the first 12 months since biologic initiation. Follow-up started on Month 13 and each bar represents the proportion of patients who continuously used reduced dose biologic (PDC < 80%). Results were stratified into the 3 bar graphs based upon the length of follow-up time during which the patients must have remained persistent with therapy.

b. Proportion of RA Patients Who Continuously Used Reduced Dose Injectable Etanercept or Adalimumab using Alternative Definition (<70% days covered)

b presents data among adherent patient defined as having PDC≥70% for the first 12 months since biologic initiation. Follow-up started on Month 13 and each bar represents the proportion of patients who continuously used reduced dose biologic using an alternative definition (PDC < 70%). Results were stratified into the 3 bar graphs based upon the length of follow-up time during which the patients must have remained persistent with therapy.

Discussion

We found an association between use of concomitant MTX and improved persistence with biologic therapy. As might have been predicted from randomized controlled trials, the effect of MTX on biologic persistence was largest in magnitude for infliximab and smallest for abatacept and tocilizumab. We also found that among RA patients who initiated etanercept or adalimumab, up to 10–20% of RA patients received self-injectable biologics at a lower than the recommended dose for an extended period of time.

Concomitant MTX was associated with incrementally greater persistence among infliximab and adalimumab users compared to etanercept, abatacept, or tocilizumab users. Our observations are consistent with those from prior trials. More than 15 years ago, a randomized controlled trial was conducted to examine the effect of concomitant MTX among 101 RA patients treated with infliximab [6]. The investigators postulated that concomitant MTX could reduce the immunogenicity of infliximab after repeated infusions and therefore help maintain long-term clinical response. The study found a dose response relationship between higher doses of concomitant MTX and diminished amount of infliximab antibodies. In the decade that followed, numerous reports observed an association between formation of antibodies against monoclonal antibodies, including infliximab and adalimumab, with reduced serum level of these agents, reduced clinical response, and increased risk of infusion reactions in patients with RA and other inflammatory diseases [17–22]. Prospective cohort studies have also linked the use of concomitant MTX to reduced immunogenicity of adalimumab and infliximab [8, 9]. Indeed, the approved indication for the treatment of RA with infliximab (and other monoclonals such as golimumab) is in combination with MTX, whereas concomitant MTX is not required in the label for some other biologics (e.g. etanercept, adalimumab). In contrast, antibodies against etanercept (a fusion protein) occur less commonly, and thus, concomitant MTX may have a smaller impact for maintaining effectiveness [23–25].

Overall, we found that infliximab, abatacept and tocilizumab users were somewhat more likely to continue their treatment than those who initiated etanercept or adalimumab, which is consistent with findings from an analysis of pharmacy claims in the U.S. [26] and among biologic naïve patients enrolled in a large U.S. cohort [27]. However, other studies reported conflicting outcomes. Data from a U.S. registry of RA patients with 5 year follow-up found that cumulative persistence rates were similar among new users of etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab [28]. However, when persistence was compared among the same three anti-TNF agents among RA patients enrolled in a large Danish rheumatology registry, etanercept users were most likely to persist with their treatment and infliximab users were least likely to do so [29]. The findings were contradictory to the results from our study. A possible explanation of the conflicting observations is presence of factors influencing treatment persistence in the Medicare patient population, which may include higher patient out-of-pocket payments for self-administered biologics, which has been previously associated with poorer adherence to biologics in RA patients in the U.S. [30]. Our patient population consisted of RA patients enrolled in the fee-for-service Medicare program with a prescription drug plan, and many of them may have experienced significant out-of-pocket co-payment for self-injectable biologics. We and others have shown that out-of-pocket co-payment for self-administered medications have potentially strong influence on the treatment decisions among those enrolled in Medicare [10, 31]. Yet another possible explanation for the observed greater persistence among infliximab users is that physicians and patients can elect to dose escalate if the initial response has been suboptimal, or secondary loss of efficacy has occurred. However, it remains unclear whether dose escalation of infliximab meaningfully improves clinical response or merely prolongs the time on treatment with suboptimal response. The effectiveness of dose escalation of other anti-TNF therapies (e.g. etancerpt, certolizumab) for RA is minimal [32, 33].

To further explore the possible reasons for treatment decisions regarding the use of concomitant MTX, we examined patients’ demographics and clinical characteristics by whether they initiated biologic therapy alone or in combination with MTX. We found that while patients were comparable with regard to demographics including age, gender, and race, those who initiated biologic alone had more comorbid diseases, were more likely to have been hospitalized for any reason and for infections, and overall appeared sicker. These differences suggest that patients who are more ill are less likely to use concomitant MTX. Finally, we also observed differences in the distribution of race and receipt of a state subsidy for Medicare premiums between patients who initiated infusion biologics and self-injectable biologic, consistent with previous observations [10].

In light of the recent randomized controlled trial demonstrating the benefit of half-dose etanercept [12], which produced a clinical response comparable to that of the standard dose, we explored how often reduced dose injectable anti-TNF therapy was already occurring in real-world clinical practice. We found significant variability in the proportion of patients who would be considered to be using anti-TNF therapy at reduced doses depending on the definition of low dose used; even with the most stringent definitions that required 12 months or more of persistence with treatment and continuous low-dose use, we found that up to 8 percent of patients were using etanercept or adalimumab at decreased doses. As a limitation of this analysis, we did not know the reasons for use of reduced doses. Potential reasons might be physician-directed dose reduction, patient-directed dose reduction (with or without their physicians’ knowledge) based on their perception that they were doing well or in light of safety concerns, or other reasons (e.g. lack of affordability). While we can only speculate on the reasons underlying low dose use, our requirement for multiple continuous, consecutive 6 month periods of low dose use was intentionally conservative to avoid the possibility that the reduce dose was simply a transient artifact of a short term safety issue (e.g. mild infection) requiring temporary cessation, or an administrative problem in obtaining the medication. If the requirement for continuous periods of low dose use was dropped, the proportion of patients estimated to be using reduced doses presumably would be higher.

Strengths of our study include a study population that consists of 100% RA patients enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service with a prescription drug plan and long-term follow-up with up to 6 years of data. However, we lacked data on RA disease activity, severity, and functional status. As a result, we were unable to control for these factors when assessing the association between concomitant MTX use and biologic persistence. The finding that patient initiated biologic monotherapy had more comorbid diseases suggest the possibility of confounding. These patients likely also had more refractory disease, and were more likely to use glucocorticoid therapy. Lack of clinical data may also limit the understanding of the reasons for the observed use of reduced dose injectable biologics. For example, this might have been medically appropriate because the patient was doing well clinically (e.g. in persistent remission). Finally, we would like to caution against deriving the proportion of monotherapy users from our results as our study population was selected based on their treatment (e.g., use of MTX) and therefore the proportion calculated from the data was artificial.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that concomitant MTX is associated with improved biologic persistence in a non-trial, real-world setting, and that this effect was greater for the monoclonal anti-TNF agents than other biologics. We also found that even prior to the publication of recent clinical trials showing reduced dose anti-TNF therapy was efficacious for many RA patients, self-injected anti-TNF therapy was used at a lower than the recommended dose for many RA patients. Further research should focus on identifying reasons why patients treated with biologics, particularly monoclonal antibodies, do not take concomitant MTX and whether this is known by their physician or something that patients were doing absent their doctor’s knowledge. For patients intolerant to higher MTX doses, a lower dose of MTX (e.g. 7.5–10mg/week) might be tolerated. Recent trial data suggest that even these doses may be sufficient to achieve near-maximal response with combination MTX + anti-TNF therapy [34]. Another important area for research is to identify which patients are the best candidates for use of biologics at reduced doses or as monotherapy, and to better understand the risk and benefits associated with prolonged used of reduced dose biologics.

Significance and Innovation.

Use of concomitant MTX is associated with greater persistence to biologic therapy.

The gradient in the association between concomitant MTX and biologic persistence is consistent with prior mechanistic studies and is strongest for infliximab, a monoclonal antibody.

Approximately 10–20% of RA patients who adhered to injectable anti-TNF therapy for at least 12 months used these biologics at reduced doses for an extended period of time.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (R01 HS018517).

Footnotes

Disclosures: JRC received consulting fees and research grants from Amgen, Abbott, BMS, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Antares, Janssen, UCB, Roche/Genentech, and CORRONA. ED, MLK, HY, NCW receive research support from Amgen. Dr. Lewis has served as a consultant for Amgen, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Prometheus, Lilly, Shire, Nestle, and Abbott. He has served on a Data and Safety Monitoring Board for clinical trials sponsored by Pfizer. He has received research support from Shire, Centocor, and Takeda. ED receives research support from Amgen.

References

- 1.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, Curtis JR, Kavanaugh AF, Kremer JM, Moreland LW, O'Dell J, Winthrop KL, Beukelman T, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64(5):625–639. doi: 10.1002/acr.21641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreland LW, O'Dell JR, Paulus HE, Curtis JR, Bathon JM, William St Clair E, Louis Bridges S, Jr, Zhang J, McVie T, Howard G, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness study of oral triple therapy versus etanercept plus methotrexate in early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 doi: 10.1002/art.34498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Dell JR, Curtis JR, Mikuls T, Cofield S, Bridges SL, Jr, Ranganath VK, Moreland LW. Validation of methotrexate-first strategy in early poor prognosis rheumatoid arthritis: Results from a randomized, double-blind, 2-year trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 doi: 10.1002/art.38012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, Genovese MC, Wasko MC, Moreland LW, Weaver AL, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1586–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Weisman M, Emery P, Feldmann M, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Concomitant Therapy Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(22):1594–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Davis D, Macfarlane JD, Antoni C, Leeb B, Elliott MJ, Woody JN, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of multiple intravenous infusions of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody combined with low-dose weekly methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(9):1552–1563. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199809)41:9<1552::AID-ART5>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP, Gough A, Kalden J, Malaise M, Martin Mola E, Pavelka K, Sany J, Settas L, et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9410):675–681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, Wolbink GJ. Methotrexate reduces immunogenicity in adalimumab treated rheumatoid arthritis patients in a dose dependent manner. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(11):1914–1915. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vermeire S, Noman M, Van Assche G, Baert F, D'Haens G, Rutgeerts P. Effectiveness of concomitant immunosuppressive therapy in suppressing the formation of antibodies to infliximab in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2007;56(9):1226–1231. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.099978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Xie F, Delzell E, Chen L, Kilgore ML, Yun H, Saag KG, Lewis JD, Curtis JR. Trends in the Use of Biologic Therapies among Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Enrolled in the U.S. Medicare Program. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013 doi: 10.1002/acr.22055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emery P, Sebba A, Huizinga TW. Biologic and oral disease-modifying antirheumatic drug monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1897–1904. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smolen JS, Nash P, Durez P, Hall S, Ilivanova E, Irazoque-Palazuelos F, Miranda P, Park MC, Pavelka K, Pedersen R, et al. Maintenance, reduction, or withdrawal of etanercept after treatment with etanercept and methotrexate in patients with moderate rheumatoid arthritis (PRESERVE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9870):918–929. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61811-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medicare Enrollment - Aged Beneficiaries: as of July 2006. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis JR, Xie F, Chen R, Chen L, Kilgore ML, Lewis JD, Yun H, Zhang J, Wright NC, Delzell E. Identifying newly approved medications in Medicare claims data: a case study using tocilizumab. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013 doi: 10.1002/pds.3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, Lee JL, Jan SA, Brookhart MA, Solomon DH. Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(7):457–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(9):915–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, Van Assche G, G DH, Carbonez A, Rutgeerts P. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(7):601–608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolbink GJ, Vis M, Lems W, Voskuyl AE, de Groot E, Nurmohamed MT, Stapel S, Tak PP, Aarden L, Dijkmans B. Development of antiinfliximab antibodies and relationship to clinical response in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(3):711–715. doi: 10.1002/art.21671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radstake TR, Svenson M, Eijsbouts AM, van den Hoogen FH, Enevold C, van Riel PL, Bendtzen K. Formation of antibodies against infliximab and adalimumab strongly correlates with functional drug levels and clinical responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(11):1739–1745. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.West RL, Zelinkova Z, Wolbink GJ, Kuipers EJ, Stokkers PC, van der Woude CJ. Immunogenicity negatively influences the outcome of adalimumab treatment in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(9):1122–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartelds GM, Wijbrandts CA, Nurmohamed MT, Stapel S, Lems WF, Aarden L, Dijkmans BA, Tak PP, Wolbink GJ. Clinical response to adalimumab: relationship to anti-adalimumab antibodies and serum adalimumab concentrations in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):921–926. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bartelds GM, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, van Schouwenburg PA, Lems WF, Twisk JW, Dijkmans BA, Aarden L, Wolbink GJ. Development of antidrug antibodies against adalimumab and association with disease activity and treatment failure during long-term follow-up. JAMA. 2011;305(14):1460–1468. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Vries MK, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Nurmohamed MT, Aarden LA, Stapel SO, Peters MJ, van Denderen JC, Dijkmans BA, Wolbink GJ. Immunogenicity does not influence treatment with etanercept in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(4):531–535. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.089979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jamnitski A, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, Hart MH, Dijkmans BA, Aarden L, Voskuyl AE, Wolbink GJ. Patients non-responding to etanercept obtain lower etanercept concentrations compared with responding patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(1):88–91. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krieckaert CL, Jamnitski A, Nurmohamed MT, Kostense PJ, Boers M, Wolbink G. Comparison of long-term clinical outcome with etanercept treatment and adalimumab treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with respect to immunogenicity. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(12):3850–3855. doi: 10.1002/art.34680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang B, Rahman M, Waters HC, Callegari P. Treatment persistence with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab in combination with methotrexate and the effects on health care costs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther. 2008;30(7):1375–1384. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(08)80063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greenberg JD, Reed G, Decktor D, Harrold L, Furst D, Gibofsky A, Dehoratius R, Kishimoto M, Kremer JM. A comparative effectiveness study of adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab in biologically naive and switched rheumatoid arthritis patients: results from the US CORRONA registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(7):1134–1142. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-150573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markenson JA, Gibofsky A, Palmer WR, Keystone EC, Schiff MH, Feng J, Baumgartner SW. Persistence with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: observations from the RADIUS registry. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1273–1281. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.101142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hetland ML, Christensen IJ, Tarp U, Dreyer L, Hansen A, Hansen IT, Kollerup G, Linde L, Lindegaard HM, Poulsen UE, et al. Direct comparison of treatment responses, remission rates, and drug adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab: results from eight years of surveillance of clinical practice in the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(1):22–32. doi: 10.1002/art.27227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curkendall S, Patel V, Gleeson M, Campbell RS, Zagari M, Dubois R. Compliance with biologic therapies for rheumatoid arthritis: do patient out-of-pocket payments matter? Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(10):1519–1526. doi: 10.1002/art.24114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeWitt EM, Glick HA, Albert DA, Joffe MM, Wolfe F. Medicare coverage of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors as an influence on physicians' prescribing behavior. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(1):57–63. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinblatt ME, Schiff MH, Ruderman EM, Bingham CO, 3rd, Li J, Louie J, Furst DE. Efficacy and safety of etanercept 50 mg twice a week in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had a suboptimal response to etanercept 50 mg once a week: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active drug-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(7):1921–1930. doi: 10.1002/art.23493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Curtis JR, Chen L, Luijtens K, Navarro-Millan I, Goel N, Gervitz L, Weinblatt M. Dose escalation of certolizumab pegol from 200 mg to 400 mg every other week provides no additional efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of individual patient-level data. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(8):2203–2208. doi: 10.1002/art.30387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fleischmann RM, Kivitz A, van Vollenhoven RF, Shaw JW, Florentinus S, Karunaratne M, Kupper H, Dougados M, Burmester G. No differences in patient-reported outcomes by methotrexate dose among early rheumatoid arthritis patients treated concomitantly with adalimumab: results from the CONCERTO trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(Suppl3):580. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]