Abstract

The experience of minority stress is often named as a cause for mental health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth, including higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation. The processes or mechanisms through which these disparities occur are understudied. The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide posits two key mechanisms for suicidal ideation: perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness (Joiner, 2009). The aim of the current study is to assess the mental health and adjustment among LGB youth emphasizing the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003) and the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (Joiner et al., 2009). With a survey of 876 LGB self-identified youth, levels of coming-out stress, sexual orientation victimization, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, depression, and suicidal ideation were examined. The results of a multigroup mediation model show that for all gender and sexual identity groups, the association of sexual orientation victimization with depression and suicidal ideation was mediated by perceived burdensomeness. For gay, lesbian, and bisexual girls coming-out stress was also found to be related to depression and suicidal ideation, mediated by perceived burdensomeness. The results suggest that feeling like a burden to “people in their lives” is a critical mechanism in explaining higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation among LGB youth. These results have implications for community and social support groups, many of which base their interventions on decreasing social isolation rather than addressing youths' beliefs of burdensomeness. Implications for future research, clinical and community settings are discussed.

Keywords: LGB youth, minority stress, interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide, depression, suicidal ideation, suicide, victimization, burdensomeness, belonging

Among U.S. youth, suicide is the third leading cause of death (CDC, 2010). Suicide attempts are nearly two and a half times more likely to occur among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth than among heterosexual peers (King et al., 2008; McDaniel, Purcell, & D'Augelli, 2001). Although studies have been criticized for methodological limitations (Savin-Williams, 2001a,b), higher levels of suicidality and depression have been documented for sexual minority youth compared to heterosexual peers using multiple methods and for youth in multiple countries (e.g., King et al., 2008; Marshal et al., 2013; Russell & Joyner, 2001). Moreover, adolescence and young adulthood are times when suicidality among sexual minority people is most common (Marshal et al., 2013). Although stress and victimization related to sexual identity have been shown to predict decreased well-being and mental health among sexual minority individuals (Cochran, Sullivan, & Mays, 2003; Meyer, 2003), the mechanisms through which these occur are understudied. In the current study we employ two theories: first, the minority stress model describes stressors that many lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals experience (Kelleher, 2009; Meyer, 2003), and second, the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide identifies key mechanisms for suicidality (Joiner et al., 2009). Together these provide a compelling framework examining mental health and adjustment among LGB youth.

Minority Stress Model

The minority stress model identifies processes through which minority stress influences mental health for sexual minority people (Meyer, 2003). Mechanisms include experiences of prejudice events, expectation of rejection or discrimination, concealment of one's sexual orientation, and internalized homophobia. Minority stress related to one's sexual identity is unique to sexual minority people and reflects society's negative reactions and attitudes toward them (Meyer, 2003; Rosario, Rotheram-Borus, & Reid, 1996). The experience of these stressors is related to lower well-being and higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation (Cochran et al., 2003; Meyer, 2003). In the current study, LGB coming-out stress and sexual orientation victimization are operationalized as aspects of minority stress that may be particularly prevalent among adolescents and young adults.

The experience of stress associated with “coming out” is often related to actual or expected negative reactions from friends, family, and peers. For example, sexual minority youth may face victimization, exclusion, and unfair treatment in school (Horn, 2007; Meyer, 2003). Thus, being out to others is a key factor that may shape the social relations of LGB youth; and coming out is often paired with a high level of stress, which is often associated with higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation (Cochran et al., 2003; Meyer, 2003).

In addition to stressors associated with coming out, LGB youth frequently experience verbal and physical victimization because of their actual or perceived sexual identity. Results from the 2011 National School Climate Survey showed that over 80% percent of LGB and over 60% of transgender students reported being verbally harassed, and almost 40% reported having experienced physical violence at school during the past year (Kosciw, Greytak, Bartkiewicz, Boesen, & Palmer, 2012). Experiences such as being threatened or injured are directly related to health-risk behaviors among sexual minority youth such as increased suicidality, substance use, and sexual risk behavior (Bontempo & D'Augelli, 2002). In general, victimization across the life span occurs more often among sexual minority than among heterosexual people (Balsam, Rothblum, & Beauchaine, 2005).

Gender and sexual identity are essential sources of variation in mental health and health behaviors among LGB. Several studies (e.g., Jorm, Korten, Rodgers, Jacomb, & Christensen, 2002) found poorer mental health and higher levels of internalized homophobia (Kuyper & Fokkema, 2011; Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, & Gwadz, 2002) among bisexual individuals compared to lesbian and gay peers. Given the potential differences between gender and sexual identities in levels of depression and suicidal ideation, and their correlates, we explored differences among LGB youth based on gender and sexual identities.

Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide

Over the past few decades studies have confirmed the impact of coming-out stress and victimization on depression and suicidal ideation (e.g., Cochran et al., 2003; Meyer, 2003). The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (IPT; Joiner et al., 2009) may shed some light on the mechanisms that drive these associations. According to this theory, suicidal ideation results from the presence of two interpersonal states: perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness.

Perceived burdensomeness is one of the two theorized predictors of depression and suicidal ideation in the IPT: It is best explained by the person's perception of himself or herself as being a burden to others. In prior studies, some informed by IPT, perceived burdensomeness has been found to predict suicidal ideation (DeCatanzaro, 1995; Joiner et al., 2002; Joiner et al., 2009; Ribeiro et al., 2012; Van Orden, Lynam, Hollar, & Joiner, 2006). For sexual minority individuals, some scholars have described feelings of being a burden to friends and family (e.g., Diaz, 1998; Diaz, Ayala, Bein, Henne, & Marin, 2001), specifically related to their “coming out” process (Hilton & Szymanski, 2011; Oswald, 1999). Two prior studies have documented an association between perceived burdensomeness and suicidal ideation for LGB college students (Hill & Pettit, 2012) and sexual minority adults (Woodward, Wingate, Gray, & Pantalone, 2014).

The second mechanism central to the IPT is thwarted belongingness, explained as alienation from friends and family—not feeling like a part of a community (Joiner et al., 2009; Ribeiro & Joiner, 2009). Social isolation seems to be one of the largest contributions to suicidal risk (Roberts, Roberts, & Chen, 1998). Among sexual minority people, social isolation is a predictor of psychologic symptoms (Diaz et al., 2001) and suicidal ideation (Hill & Pettit, 2012). Further, there is an extensive body of research (e.g., Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009; Hatzenbuehler, Phelan, & Link, 2013; Pachankis, 2007) that points to the ways that social isolation is produced for sexual minority people. Belongingness is often thwarted for LGB youth through LGBT-related victimization and bullying experiences (e.g., Kosciw et al., 2012), which have been linked to suicide risk (Bontempo & D'Augelli, 2002).

Although originally it was thought that both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness should both be present for suicidal ideation to develop (Joiner et al., 2009), several studies have found that thwarted belongingness operates primarily in conjunction with perceived burdensomeness (Joiner et al., 2009; Van Orden et al., 2008). Therefore, to examine the impact of both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness on suicidality and depression it is best to study these concepts jointly in one model.

To our knowledge, there are only two studies that have explicitly applied the IPT in examining suicide risk among sexual minority people. The first was a study of college students, 50 of whom were LGB. Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness were related to suicidal ideation; this relation was conditional on the level of perceived or anticipated rejection due to sexual identity (Hill & Pettit, 2012). The second was a study among 210 sexual minority adults: Only perceived burdensomeness was related to suicidal ideation, and not thwarted belongingness (Woodward et al., 2014).

Minority Stress, Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide, and LGB Youth

Over the last two decades scholars have identified minority stressors associated with suicidality among sexual minority individuals, including stressors associated with coming out, as well as (potentially related) experiences of family rejection, victimization, and homophobic persecution (e.g., Friedman, Koeske, Silvestre, Korr, & Sites, 2006; Russell & Joyner, 2001; Ryan, Huebner, Diaz, & Sanchez, 2009). Such sexual identity-specific stressors may be distal predictors of depression and suicidal ideation through the mediation of general risk factors such as rumination (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). As such, LGB youth may be at an increased risk of experiencing thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness due to LGB-specific stressors (Hill & Pettit, 2012). For example, LGB-victimization may explain school social isolation that is often reported by sexual minority youth (Galliher, Rostosky, & Hughes, 2004); such a lack of belonging has been found to predict suicidal ideation, particularly among LGB youth (Hill & Pettit, 2012). Alternatively, stressors associated with coming out could lead to perceived burdensomeness; many gay and bisexual Latino men report feelings of hurt and embarrassment for family members due to their gay identity, and such feelings are associated with suicidal ideation (Diaz et al., 2001).

Based on prior theoretical and empirical studies, we expect both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness to be associated with higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation for LGB youth. To our knowledge, there is currently no study that assesses the concepts from the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness) as mediators of the relation between minority stressors and mental health among LGB youth. There is especially strong evidence that LGB youth experience thwarted belongingness through minority stressors (for example, peer victimization (Bontempo & D'Augelli, 2002) and family rejection (Ryan et al., 2009), and that such minority stress predicts suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Therefore, the present study advances our knowledge on both the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide and the minority stress model, applied in a large group of LGB youth.

Present Study

The objective of the current project is to test hypotheses derived from the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003) and the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (Joiner et al., 2009). We hypothesized that: (1) stress related to coming out as LGB and sexual orientation victimization are related to higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation, and (2) these relations are mediated by perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. We examined the hypothesized relations in a sample of 876 LGB youth, aged 15-21 years old (M = 18.31, SD = 1.82).

Method

Participants and design

Data come from the first of four waves in a longitudinal panel study of the risk and protective factors of suicide among 1061 lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans*, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth and participants with same-sex attraction in three cities in the northeast, southwest, and west coast of the United States. The majority of the youth were recruited from community-based agencies (35.6% were a member of one of these organizations) or college groups for LGBTQ youth, and other participants were referred by earlier participants.

Participants received a cash incentive for their participation in the first panel of the study. Approval of all procedures was granted by the IRB's of both U.S.-based universities involved. Because seeking parental consent could put youth at risk of exposure of their sexual orientation or gender identity and could lead to verbal or physical harm, parental consent was not required, and a federal certificate of confidentiality was obtained.

Trans* and questioning participants were not included in the current analysis. Of the included participants (N = 876, ages 15-21 at time of recruitment, M = 18.31, SD = 1.82), 30.7% identified as gay men, 21.8% as lesbian or gay-identified women, 15.5% as bisexual men, 31.9% as bisexual women. Most participants currently attended school (73.2%), and most participants were in, or had left, high school(47.4%; grades 6 through 12) or college/university (34.1%). A smaller group of participants had graduated high school (14.2%).

Using current federal reporting guidelines, 39.3% of the LGB youth were of Hispanic or Latino background. Regarding race, 20.3% were White, 24.9% Black or African-American, 4.9% Asian, 2.9 % American Indian or Alaskan Native, 0.8% Native Hawaii or Other Pacific Islander, 22.5% more than one race, and 23.7% did not report their race.

Measures

Background characteristics

Age, ethnicity, birth sex, and sexual identity were asked. Birth sex could be reported as “male,” “female,” or “intersex.” Sexual identity could be reported as “gay,” “lesbian,” “bisexual, but mostly gay or lesbian,” “bisexual, equally gay/lesbian and heterosexual/straight,” “bisexual, but mostly heterosexual/straight,” “heterosexual/straight,” or “questioning/uncertain, don't know for sure.” The three bisexual categories were combined for these analyses.

LGB coming-out stress

An expanded version of the gay-related stress scale (Rosario et al., 1996) was used to assess stress related to coming out as LGB—the scale comprised the mean score of 10 items (α = .90 for the current sample). An example item is “For each event listed below, we would like you to rate how stressful the situation was for you. When you told your parents for the first time that you were LGB,” participants could answer on 5-point scales (0 = no stress and 4 = extremely stressful).

Sexual orientation victimization

The frequency of life-time sexual orientation victimization (D'Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006) was assessed with six items (i.e., verbal, physical, sexual).Prompted by an open-ended question, participants were asked the frequency with which they had experienced various types of sexual orientation victimization in their life-time. An example item is “Punched, kicked, or beaten,” Responses were coded on a 4-point scale (0 = never and 3 = three or more times). For the current analysis, we used a sum score of the six items (α = .84 for the current sample).

Perceived burdensomeness

Perceived burdensomeness was assessed with a seven-item subscale of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (Van Orden et al., 2008). An example item is “These days, I think the people in my life wish they could be rid of me.” Participants could answer on 7-point scales (1 = not at all true for me and 7 = very true for me). A mean score of these items was used; internal reliability was high (α = .88 for the current sample).

Thwarted belongingness

Thwarted belongingness was measured as the mean of five-item subscale of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (Van Orden et al., 2008; α = .75 for the current sample). An example item is “These days, I feel disconnected from other people,” participants could answer on 7-point scales (1 = not at all true for me and 7 = very true for me).

Depression

Depression level was measured as the mean of twenty items assessing how the youth thought or felt, especially in the last two weeks (Beck Depression Inventory - Youth (BDI-Y), Beck, Beck, & Jolly, 2001; α = .95 for the current sample). An example item is “I have trouble doing things”; participants could answer on 4-point scales (0 = never and 3 = always).

Suicidal ideation

We assessed negative suicidal ideation as the mean of the eight item Negative suicide ideation subscale of the Positive and Negative Suicide Inventory (Muehlenkamp et al., 2005; α = .94 for the current sample). An example item is “During the past two weeks, including today, how often have you seriously considered killing yourself because you could not live up to the expectations of other people”; participants could answer on 5-point scales(1 = none of the time and 5 = most of the time).

Others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity

Participants reported whether their friends and family knew about their sexual identity with six items (D'Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2008; mean score, α = .88 for the current sample). An example item is “Do the people listed below know that you are LGB? Mother (adoptive mother, foster mother, stepmother, etc.)”; participants could answer on 4-point scales (1 = definitely not and 4 = definitely).

Statistical Analyses

To test the hypothesized relations we first checked Pearson correlations. To examine group differences based on biological sex/gender (and because they are congruent for the youth in the analytic sample we refer to “gender” in our written results), sexual identity and ethnic backgrounds we used several multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) with follow-up univariate analyses of variance and post hoc group comparisons (Bonferroni). The software package Mplus (Muthen & Muthen, 2010) was used to conduct multigroup bootstrap mediation analyses, controlling for age, others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity, and membership in a community-based organization. Further, we included the direct relation between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness and the direct relation between depression and suicidal ideation. Indirect effects were tested using the MODEL INDIRECT option in Mplus. We used three goodness-of-fit indices: CFI, TLI, and RMSEA (Brown & Cudeck, 1993) to compare constrained, partially constrained, and unconstrained models. CFI and TLI values above .95 and RMSEA less than or equal to .06 usually indicate acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Given the large sample size in the current study, chi-square statistics were not suitable.

Results

Associations Between Key Variables

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and the correlations between the key variables for the overall group of participants. As expected, there were positive associations for LGB coming-out stress and sexual orientation victimization with depression and suicidal ideation. Perceived burdensomeness was found to be positively related to levels of LGB coming-out stress, sexual orientation victimization, depression, and suicidal ideation. Thus, participants with higher levels of LGB coming-out stress and victimization also showed higher levels of perceived burdensomeness, depression and suicidal ideation. The direct relation between sexual orientation victimization and thwarted belongingness was not significant, however, thwarted belongingness was significantly related to higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation.

Table 1. Pearson Correlations Between Key Variables and Means, Standard Deviations, and Range of Key variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | M (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. LGB coming-outstress | -- | 1.49 (1.08) | 0-4 | |||||||

| 2. Sexual orientationvictimization | .22*** | -- | 3.79 (4.29) | 0-18 | ||||||

| 3. Perceived burdensomeness | .09* | .10** | -- | 2.54 (1.34) | 1-7 | |||||

| 4. Thwarted belongingness | .10** | .06 | .53*** | -- | 3.04 (1.39) | 1-6.60 | ||||

| 5. Depression | .21*** | .15*** | .66*** | .43*** | -- | 0.81 (0.63) | 0-32.90 | |||

| 6. Suicidal ideation | .15*** | .16*** | .57*** | .34*** | .62*** | -- | 1.55 (0.83) | 1-5 | ||

| 7. Others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity | .00 | .13*** | -.16*** | -.15*** | -.17*** | -.11** | -- | 3.18 (0.89) | 1-4 | |

| 8. Age | .17*** | .14*** | -.13*** | .00 | -.12*** | -.03 | .09* | -- | 18.31 (1.82) | 15-21 |

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Older participants reported higher levels of LGB coming-out stress, sexual orientation victimization, and others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity, but lower levels of perceived burdensomeness and depression. Finally, others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity was related to higher levels of sexual orientation victimization, but lower levels of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, depression, and suicidal ideation.

To examine differences between gender and sexual identity groups in the key variables, we conducted several MANOVAs (see Table 2). Mean levels of LGB coming-out stress and sexual orientation victimization differed across gender and sexual identities (Pillai's Trace = .08, F(6, 1658) = 12.15, p < .001, η2p = .042). Bisexual girls reported lower levels of LGB coming-out stress than gay boys, bisexual boys, and lesbian and gay girls, 95% CIs [-0.57, -0.07], [-0.73, -.11], and [-0.55, -0.00], respectively. Bisexual girls also reported lower levels of sexual orientation victimization than gay boys, bisexual boys, and lesbian and gay girls, 95% CIs [-3.85, -1.92], [-3.52, -1.11], and [-2.59, -0.46], respectively. Further, gay boys reported more LGB victimization compared to gay and lesbian girls, 95%CI [0.29, 2.42].

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for the Key Variables Across Gender and Sexual Identity Groups and Results of the Preliminary Analyses.

| Boys | Girls | Gender and sexual identity group differences | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Gay | Bisexual | Lesbian and Gay | Bisexual | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | df | F | p value | η2p | |

| LGB coming-out stress | 1.58 (1.06)a | 1.68 (1.14) a | 1.54 (1.08) a | 1.26 (1.08) | 3, 829 | 6.05 | < .001 | .021 |

| Sexual orientation victimization | 5.21 (4.62) a,b | 4.64 (4.60) a | 3.85 (4.26) a | 2.32 (3.36) | 22.35 | < .001 | .075 | |

| Perceived burdensomeness | 2.39 (1.31) a | 2.60 (1.28) | 2.44 (1.22) | 2.74 (1.44) | 3, 869 | 6.40 | .013 | .012 |

| Thwarted belongingness | 2.88 (1.42) | 3.18 (1.35) | 3.13 (1.37) | 3.07 (1.39) | 1.86 | .134 | .006 | |

| Depression | 0.69 (0.63) a | 0.85 (0.57) | 0.74 (0.60) a | 0.96 (0.65) | 3, 864 | 9.38 | < .001 | .032 |

| Suicidal ideation | 1.45 (0.73) | 1.67 (0.87) | 1.50 (0.84) | 1.62 (0.88) | 3.01 | .029 | .010 | |

| Age | 18.83 (1.66) a | 18.34 (1.79) a | 18.43 (1.69) a | 17.71 (1.88) | 3, 872 | 8.78 | < .001 | .061 |

| Others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity | 3.39 (0.88) a,c | 2.93 (0.87) b | 3.44 (0.74) a | 2.92 (0.90) | 3, 867 | 23.46 | < .001 | .075 |

Significant post-hoc group comparison to bisexual girls (ps < .05)

Significant post-hoc group comparison to gay or lesbian girls (ps < .05)

Significant post-hoc group comparison to bisexual boys (ps < .05)

Mean levels of perceived burdensomeness also differed across gender and sexual identities (Pillai's Trace = .02, F(6, 1738) = 2.80, p = .010, η2p = .010). Gay boys reported lower levels of perceived burdensomeness than bisexual girls, 95%CI [-0.65, -0.05]. Further, mean levels of depression differed across gender and sexual identities (Pillai's Trace = .04, F(6, 1728) = 5.32, p < .001, η2p = .018). Bisexual girls reported higher levels of depression than gay and lesbian girls and gay boys, 95% CIs [-0.37, -0.06], and [0.13, 0.41], respectively.

Finally, age and level of others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity differed across gender and sexual identities. Bisexual girls were youngest compared to gay boys, lesbian and gay girls, and bisexual boys, 95% CIs [-1.51, -0.72], [-1.16, -0.28], and [-1.11, -0.14], respectively.

Further, bisexual girls reported the lowest levels of others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity compared to gay boys, and compared to lesbian and gay girls, 95% CIs [-0.66, -0.27], and [0.31, 0.73], respectively. Bisexual boys also reported lower levels of others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity compared to gay boys, 95% CIs [-0.70, -0.22], and [-0.77, -0.26], respectively.

Levels of depression differed across different ethnic backgrounds (F(6, 861) = 5.41, p < .001, η2p = .036]). Black or African American youth reported lower levels (M = 0.62, SD = 0.56) compared to White youth (M = 0.96, SD = 0.61), 95%CI [-0.52, -0.14. Mean levels of LGB coming-out stress, sexual orientation victimization, perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and suicidal ideation did not differ across different ethnic backgrounds (ps > .05).

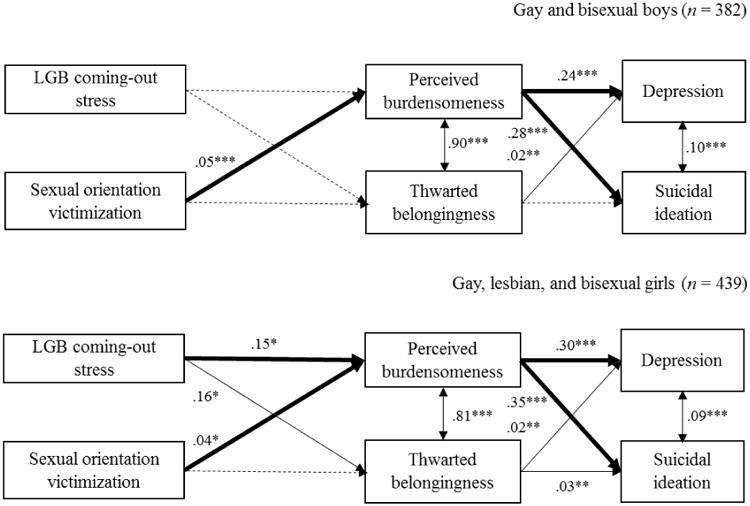

Mediating Role of Perceived Burdensomeness and Thwarted Belongingness

Considering the small but consistent differences in mean levels of LGB coming-out stress, victimization, perceived burdensomeness, depression, age and others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity across the different gender and sexual identities, we tested a multigroup mediation model across groups (gay boys, bisexual boys, gay and lesbian girls, bisexual girls) controlling for age, others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity, and membership in a community-based organization. For these models, a two-group model showed the best fit, compared to a fully constrained and unconstrained model (see Table 3). The best-fitting model was defined by differences in gender rather than by differences in sexual identity. The two-group models consisted of (1) gay boys and bisexual boys, and (2) lesbian girls, and bisexual girls. The percentage of variance explained by this indirect model across the four gender and sexual identity groups, ranged from 43% to 54% for depression and from 30% to 38% for suicidal ideation (see Figure 1).

Table 3. Fit Statistics for Unconstrained, Constrained, and Partially Constrained Models.

| RMSEA | CFI | TLI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constrained | .048 | .985 | .963 |

| Partially constrained | .049 | .988 | .961 |

| Unconstrained | .063 | .995 | .936 |

Note. In the partially constrained model, all paths are constrained for (1) gay and bisexual boys, (2) and gay, lesbian, and bisexual girls.

Figure 1.

Partially constrained multigroup mediation model of depression and suicidal ideation. Controlling for age, others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity, and membership to a community-based organization. Indirect mediation effects are presented in solid bold arrows. Direct significant relations are presented in solid arrows, direct non-significant relations are presented in dashed arrows. Unstandardized regression coefficients are shown. *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05

For gay and bisexual boys, the results showed that the links between sexual orientation victimization and depression and suicidal ideation were mediated by perceived burdensomeness (specific indirect effect for depression, 95%CI [.007, .020], p= .002; for suicidal ideation, 95%CI [.007, .015], p = .003). For lesbian and bisexual girls, the results are largely similar—the links between sexual orientation victimization and depression and suicidal ideation were mediated by perceived burdensomeness (specific indirect effect for depression, 95%CI [.003, .020], p = .025; for suicidal ideation, 95%CI [.004, .024], p = .029). Only among lesbian and bisexual girls, perceived burdensomeness also mediated the relations between LGB coming-out stress and depression and suicidal ideation (specific indirect effect for depression, 95%CI [.015, .074], p = .015; for suicidal ideation, 95%CI [.004, .024], p = .029). For no group was mediation through thwarted belongingness significant (ps > .05).

We also tested the interactions between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness in predicting depression and suicidal ideation. The interactions were not significant (ps > .05), however, the direct relations between perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness were significant (gay and bisexual boys: B = .81, p < .001; gay, lesbian, and bisexual girls: B = .90, p < .001).

Discussion

Our study brings together the minority stress model (Meyer, 2003) and interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (Joiner et al., 2009) in an effort to understand the mechanisms associated with minority stress and its association with depression and suicidal ideation in a sample of LGB youth. For all LGB youth in the study, we found that sexual orientation victimization negatively impacts levels of depression and suicidal ideation, and this relation can be explained by the experience of feeling like a burden to others in their lives. The benefit of combining the minority stress model and IPT is that both have been crucial for studies of minority stress and suicidality. Bringing them together has significant potential to advance understanding of mental health and suicide among LGB youth.

Our findings indicate, regardless of gender or sexual identity, the link between sexual orientation victimization and depression and suicidal ideation was mediated by perceived burdensomeness. These findings are consistent with literature on suicidal behavior (Joiner et al., 2009; Hill & Pettit, 2012; Van Orden et al., 2008; Woodward et al., 2014)as well as the impact of minority stressors (Meyer, 2003). Although both “preconditions” of the IPT are individually correlated with depression and suicidal ideation, several studies have shown that the feeling of being a burden to others (perceived burdensomeness) is the key mechanism when both are included in multivariate analyses (Hill & Pettit, 2012; Van Orden et al., 2008; Woodward et al., 2014). Thus, the results are consistent with emerging research on the mechanisms of the IPT theory. However, of these two risk factors, the LGB mental health literature has emphasized factors consistent with thwarted belongingness explanations over perceived burdensomeness: The dominant discourse in the literature on LGB youth mental health has focused on social isolation, family rejection, and victimization or lack of belonging in school as the key mechanisms for understanding mental health risk (e.g., Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013; Meyer, 2003; Mustanksi, Birkett, Greene, Hatzenbuehler, & Newcomb, 2014). With few yet notable exceptions (Diaz, 1998; Diaz et al., 2001), much less attention in the LGB mental health literature has focused on perceptions of feeling like a burden to other people in their lives. Minority stress may not have its greatest function through thwarted belonging, but through the ways it makes LGB young people feel that they are a burden to their loved ones due to their stigma and victimization.

Patterns in the indirect pathways showed distinct differences based on gender and sexual identity groups. First, it is only for girls that stressors associated with coming out are mediated for depression and suicidal ideation by perceived burdensomeness. Notably, both groups of girls (especially bisexual, but also lesbian and gay girls) reported lower average coming-out stress compared to boys. Further, for both boys and girls, the relation between sexual orientation victimization and depression and suicidal ideation is mediated by perceived burdensomeness. Interestingly, although experiencing sexual orientation victimization has a negative impact on perceived burdensomeness, depression, and suicidal ideation for both boys and girls, gay boys report the highest mean levels of sexual orientation victimization. It may be that for boys, experiences of victimization matter to the extent that they simply overpower the role of coming-out stress, whereas girls may be more attuned to others' reactions to their coming out, so that stressors associated with coming out play a stronger role in the effect of perceived burdensomeness on depression and suicidal ideation. These findings indicate gender and sexual identity differences both in average levels of these concepts, but more importantly also in the mechanism that helps explain the development of health disparities. One of the explanations for these differences in mechanism may be the different attitudes toward male and female same-sex attraction, or different expressions of these attitudes. Although attitudes toward gay men are thought to be more hostile than attitudes toward lesbian women (Herek, 2000; LaMar & Kite, 1998), much is unknown about the different forms of victimization that they may experience. In general adolescent research, boys are found to be more likely to experience direct aggression than girls, whereas gender differences in indirect victimization are less obvious (Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008). Further, indirect aggression seems to be the best predictor of internalizing problems, whereas direct aggression is more strongly linked to externalizing problems (Card et al., 2008).

Although research has shown that rejection or discrimination of same-sex attracted men and women may differ in intensity and form, the current study shows that victimization negatively impacts LGB youths' notion of being a burden to others, and their levels of depression and suicidal ideation among both boys and girls. An in-depth study of the different kinds of victimization, intensity, and differential impact, would allow further exploration of these gender and sexual identity differences.

The current study includes several strengths and limitations. We obtained data from a relatively large sample of LGB youth; however, all the data were obtained through self-report rather than objective measures (e.g., others' perceived knowledge of sexual identity). Further, the analyses in the current study were done on cross-sectional data. Mediational models, as tested in the current study, assume a causal process and this may result in some bias when used to analyze cross-sectional data (Maxwell, Cole, & Mitchell, 2011). Additionally, the data were obtained from self-identified LGB youth in three metropolitan areas in the U.S.; and the data may not generalize to similar youth outside of these areas in the U.S. or in other countries (due cultural contexts, especially related to sexuality and youth).

Implications

Consistent with previous research we found different patterns for LGB boys and girls in levels of minority stress and depression and suicidal ideation (D'Augelli et al., 2005; Kuyper & Fokkema, 2011; Rosario et al., 2002). Girls seem to experience lower levels of LGB coming-out stress and victimization, but higher levels of depression and suicidal ideation compared to boys. Although girls experience lower levels of stress related to their coming out, these stressful experiences are related to feelings of thwarted belongingness and of being a burden to friends and family, and in turn to depression and suicidal ideation. Stressful experiences concerning coming out may play a distinct role for LGB girls compared to GB boys. This raises several suggestions for future research and implications for potential interventions.

First, several recent studies point to the ways that discriminatory victimization undermines youth well-being (Russell, Sinclair, Poteat, & Koenig, 2012) and our findings further underline the role of discriminatory victimization in depression and suicide ideation among LGB youth. Advocates should identify contexts where victimization occurs and implement strategies and policies to reduce victimization. Community programs can emphasize support and resources for victimized youth, and in particular may address feelings of being a burden to others that may result when a youth must seek help following discriminatory victimization. Further, schools can implement LGB-inclusive curricula and in-school bullying and harassment policies that specifically address LGB identities (Kosciw et al., 2012; Toomey, McGuire, & Russell, 2012).

Second, the current findings suggest that specific attention to stress related to “coming out” or disclosure of sexual identity for girls may be warranted. Although girls experienced lowest levels of coming-out stress, this affected their sense of being of burden to others and increased their level of depression and suicidal ideation. Girls, and especially bisexual girls, appear to experience coming-out stress differently than boys. Perhaps the rejection of lesbian and bisexual girls differs from the rejection of gay and bisexual boys. The current emphasis on victimization and overt rejection in policies, programs, and support groups, may not validate girls' experiences of stress. Bisexual girls may experience different forms of stress and discrimination (biphobia versus homophobia) and perhaps more covert forms of rejection that affect their mental health and suicidality, but were not captured in our measure of coming-out stress.

Finally, our results strongly indicate that it is the notion of being a burden to others that is underlying the adverse effects of minority stress on depression and suicidal ideation among LGB youth. Perceived burdensomeness is considered both an interpersonal experience and an intrapersonal belief, and previous research suggests that the interpersonal cognitions of burdensomeness take precedence over the intrapersonal beliefs (Joiner et al., 2002). It follows that people may have a general need to contribute, which may be more important than the need to belong in the development of depression and suicidal ideation. While decreasing victimization, discrimination, and providing social support is important, added attention should be given to ways of reducing the experience of feeling like a burden. Not only does it aid clinicians in suicide risk assessment (Joiner et al., 2009), it may also offer room for intervention; behavioral approaches have been suggested to decrease feelings of burdensomeness (Joiner et al., 2009). Although intervening in risk factors is important to eliminating suicidal behaviors among LGB youth, clinicians also must enhance resilience and protective factors.

Conclusions

Despite the significant additions to the field of LGB-health, further study will enable an understanding of how the mechanisms of suicide risk may operate over the course of adolescence for LGB youth: Future longitudinal studies may allow identification of potential developmental trajectories of both stress and victimization, and subsequent depression and suicidal ideation. Although longitudinal studies have shown that stress and victimization impact sexual minority youths' health (e.g., Rosario et al., 2006), it would be relevant to investigate the dynamic, longitudinal interplay of these domains in association with feelings of burdensomeness and belonging. In a broader model, it would also be possible to include potential protective factors, such as school safety (Eisenberg & Resnick, 2006), and involvement in the LGB community (Meyer, 2003).

The current study provides new knowledge about the negative impact of sexual orientation-victimization and coming-out stress, and related health disparities. Further, the current study is one of the first to look at the mechanism that may help explain the development of depression and suicidal ideation. In doing so, we have brought together two theories (minority stress and IPT) that provide new insight into the negative and harmful experiences of some LGB youth.

Acknowledgments

This research uses data from the Risk and Protective Factors for Suicide among Sexual Minority Youth study, designed by Arnold H. Grossman and Stephen T. Russell, and supported by Award Number R01MH091212 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. This work was done with financial assistance from a Fulbright visiting scholar grant.

Contributor Information

Laura Baams, Developmental Psychology; Utrecht University.

Arnold H. Grossman, Department of Applied Psychology; NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development.

Stephen T. Russell, Norton School of Family & Consumer Sciences; College of Agriculture and Life Sciences; University of Arizona.

References

- Balsam KF, Rothblum ED, Beauchaine TP. Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:477–487. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS, Beck AT, Jolly JB. Beck youth inventories. San Antonio, TX, USA: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo DE, D'Augelli AR. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths' health risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:364–374. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Stucky BD, Sawalani GM, Little TD. Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development. 2008;79:1185–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) 2010 Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/ncipc/wisqars.

- Cochran SD, Sullivan JG, Mays VM. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:53–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Salter NP, Vasey JJ, Starks MT, Sinclair KO. Predicting the suicide attempts of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35:646, 660. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.6.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT. Families of gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth: What do parents and siblings know and how do they react? Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2008;4:95–115. doi: 10.1080/15504280802084506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeCatanzaro D. Reproductive status, family interactions, and suicidal ideation: Surveys of the general public and high-risk groups. Ethology & Sociobiology. 1995;16:385–394. doi: 10.1016/0162-3095(95)00055-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM. Latino gay men and HIV: Culture, sexuality, and risk behavior. New York, NY: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz RM, Ayala G, Bein E, Henne J, Marin BV. The impact of homophobia, poverty and racism on the mental health of gay and bisexual Latino men: Findings from 3 US cities. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:927–932. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9905-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Resnick MD. Suicidality among gay, lesbian and bisexual youth: The role of protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:662–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman MS, Koeske GF, Silvestre AJ, Korr WS, Sites EW. The impact of gender-role nonconforming behavior, bullying, and social support on suicidality among gay male youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:621–623. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galliher RV, Rostosky SS, Hughes HK. School belonging, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms in adolescents: An examination of sex, sexual attraction status, and urbanicity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2004;33:235–245. doi: 10.1023/B:JOYO.0000025322.11510.9d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological bulletin. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103:813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Sexual prejudice and gender: Do heterosexuals' attitudes toward lesbians and gay men differ? Journal of Social Issues. 2000;56:251–266. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, Pettit JW. Suicidal ideation and sexual orientation in college students: the roles of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and perceived rejection due to sexual orientation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2012;42:567–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton AN, Szymanski DM. Family dynamics and changes in sibling of origin relationship after lesbian and gay sexual orientation disclosure. Contemporary Family Therapy. 2011;33:291–309. doi: 10.1007/s10591-011-9157-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS. Leaving lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender students behind: Schooling, sexuality, and rights. In: Wainryb C, Smetana J, Turiel E, editors. Social development, social inequalities & social justice. Mahwaw, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2007. pp. 131–153. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T, Pettit JW, Walker RL, Voelz ZR, Cruz J, Rudd MD, et al. Perceived burdensomeness and suicidality: Two studies on the suicide notes of those attempting and those completing suicide. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 2002;21:531–545. doi: 10.1521/jscp.21.5.531.22624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Selby EA, Ribeiro JD, Lewis R, et al. Main predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:634–646. doi: 10.1037/a0016500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, Korten AE, Rodgers B, Jacomb PA, Christensen H. Sexual orientation and mental health: results from a community survey of young and middle-aged adults. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;180:423–427. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher C. Minority stress and health: Implications for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2009;22:373–379. doi: 10.1080/09515070903334995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, Nazareth I. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC psychiatry. 2008;8:70–97. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Bartkiewicz MJ, Boesen MJ, Palmer NA. The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation's schools. New York: GLSEN; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper L, Fokkema T. Minority stress and mental health among Dutch LGBs: Examination of differences between sex and sexual orientation. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:222–233. doi: 10.1037/a0022688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMar L, Kite M. Sex differences in attitudes toward gay men and lesbians: A multidimensional perspective. Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35:189–196. doi: 10.1080/00224499809551932. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dermody SS, Cheong J, Burton CM, Friedman MS, Aranda F, et al. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and suicidality among heterosexual and sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:1243–1256. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9970-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA, Mitchell MA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: Partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2011;46:816–841. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.606716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel JS, Purcell D, D'ugelli AR. The relationship between sexual orientation and risk for suicide: Research findings and future directions for research and prevention. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2001;31:84–105. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.1.5.84.24224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Gutierrez PM, Osman A, Barrios FX. Validation of the Positive and Negative Suicide Ideation (PANSI) Inventory in a diverse sample of young adults. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:431–45. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Birkett M, Greene GJ, Hatzenbuehler ML, Newcomb ME. Envisioning an America without sexual orientation inequities in adolescent health. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:218–225. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user's guide. 6th. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Oswald RF. Family and friendship relationships after young women come out as bisexual or lesbian. Journal of Homosexuality. 1999;38:65–83. doi: 10.1300/J082v38n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:328–345. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Joiner TE. The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: current status and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1291–1299. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Pease JL, Gutierrez PM, Silva C, Bernert RA, Rudd, et al. Sleep problems outperform depression and hopelessness as cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation and behavior in young adults in the military. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2012;136:743–750. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR. Suicidal thinking among adolescents with a history of attempted suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37:1294–1300. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199812000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Reid H. Gay-related stress and its correlates among gay and bisexual male adolescents of predominantly Black and Hispanic background. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:136–159. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6629(199604)24:2<136∷AID-JCOP5>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Gwadz M. Gay related stress and emotional distress among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:967–975. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1276–1281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.8.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Sinclair KO, Poteat VP, Koenig B. Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:493–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. A critique of research on sexual-minority youths. Journal of Adolescence. 2001a;24:5–13. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Suicide attempts among sexual-minority youths: Population and measurement issues. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001b;69:983. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.69.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, McGuire JK, Russell ST. Heteronormativity, school climates, and perceived safety for gender nonconforming peers. Journal of Adolescence. 2012;35:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Lynam ME, Hollar D, Joiner TE., Jr Perceived burdensomeness as an indicator of suicidal symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30:457–467. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9057-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, Joiner TE., Jr Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:72–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward EN, Wingate L, Gray TW, Pantalone DW. Evaluating thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as predictors of suicidal ideation in sexual minority adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2014;1:234–243. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]