Abstract

Information spreads across social and technological networks, but often the network structures are hidden from us and we only observe the traces left by the diffusion processes, called cascades. Can we recover the hidden network structures from these observed cascades? What kind of cascades and how many cascades do we need? Are there some network structures which are more difficult than others to recover? Can we design efficient inference algorithms with provable guarantees?

Despite the increasing availability of cascade-data and methods for inferring networks from these data, a thorough theoretical understanding of the above questions remains largely unexplored in the literature. In this paper, we investigate the network structure inference problem for a general family of continuous-time diffusion models using an -regularized likelihood maximization framework. We show that, as long as the cascade sampling process satisfies a natural incoherence condition, our framework can recover the correct network structure with high probability if we observe O(d3 log N) cascades, where d is the maximum number of parents of a node and N is the total number of nodes. Moreover, we develop a simple and efficient soft-thresholding inference algorithm, which we use to illustrate the consequences of our theoretical results, and show that our framework outperforms other alternatives in practice.

1. Introduction

Diffusion of information, behaviors, diseases, or more generally, contagions can be naturally modeled as a stochastic process that occur over the edges of an underlying network (Rogers, 1995). In this scenario, we often observe the temporal traces that the diffusion generates, called cascades, but the edges of the network that gave rise to the diffusion remain unobservable (Adar & Adamic, 2005). For example, blogs or media sites often publish a new piece of information without explicitly citing their sources. Marketers may note when a social media user decides to adopt a new behavior but cannot tell which neighbor in the social network influenced them to do so. Epidemiologist observe when a person gets sick but usually cannot tell who infected her. In all these cases, given a set of cascades and a diffusion model, the network inference problem consists of inferring the edges (and model parameters) of the unobserved underlying network (Gomez-Rodriguez, 2013).

The network inference problem has attracted significant attention in recent years (Saito et al., 2009; Gomez-Rodriguez et al., 2010; 2011; Snowsill et al., 2011; Du et al., 2012a), since it is essential to reconstruct and predict the paths over which information can spread, and to maximize sales of a product or stop infections. Most previous work has focused on developing network inference algorithms and evaluating their performance experimentally on different synthetic and real networks, and a rigorous theoretical analysis of the problem has been missing. However, such analysis is of outstanding interest since it would enable us to answer many fundamental open questions. For example, which conditions are sufficient to guarantee that we can recover a network given a large number of cascades? If these conditions are satisfied, how many cascades are sufficient to infer the network with high probability? Until recently, there has been a paucity of work along this direction (Netrapalli & Sanghavi, 2012; Abrahao et al., 2013) which provide only partial views of the problem. None of them is able to identify the recovery condition relating to the interaction between the network structure and the cascade sampling process, which we will make precise in our paper.

Overview of results

We consider the network inference problem under the continuous-time diffusion model recently introduced by Gomez-Rodriguez et al. (2011). We identify a natural incoherence condition for such a model which depends on both the network structure, the diffusion parameters and the sampling process of the cascades. This condition captures the intuition that we can recover the network structure if the co-occurrence of a node and its non-parent nodes is small in the cascades. Furthermore, we show that, if this condition holds for the population case, we can recover the network structure using an -regularized maximum likelihood estimator and O(d3 log N) cascades, and the probability of success is approaching 1 in a rate exponential in the number of cascades. Importantly, if this condition also holds for the finite sample case, then the guarantee can be improved to O(d2 log N) cascades. Beyond theoretical results, we also propose a new, efficient and simple proximal gradient algorithm to solve the -regularized maximum likelihood estimation. The algorithm is especially well-suited for our problem since it is highly scalable and naturally finds sparse estimators, as desired, by using soft-thresholding. Using this algorithm, we perform various experiments illustrating the consequences of our theoretical results and demonstrating that it typically outperforms other state-of-the-art algorithms.

Related work

Netrapalli & Sanghavi (2012) propose a maximum likelihood network inference method for a variation of the discrete-time independent cascade model (Kempe et al., 2003) and show that, for general networks satisfying a correlation decay, the estimator recovers the network structure given O(d2 log N) cascades, and the probability of success is approaching 1 in a rate exponential in the number of cascades. The rate they obtained is on a par with our results. However, their discrete diffusion model is less realistic in practice, and the correlation decay condition is rather restricted: essentially, on average each node can only infect one single node per cascade. Instead, we use a general continuous-time diffusion model (Gomez-Rodriguez et al., 2011), which has been extensively validated in real diffusion data and extended in various ways by different authors (Wang et al., 2012; Du et al., 2012a;b).

Abrahao et al. (2013) propose a simple network inference method, First-Edge, for a slightly different continuous-time independent cascade model (Gomez-Rodriguez et al., 2010), and show that, for general networks, if the cascade sources are chosen uniformly at random, the algorithm needs O(Nd log N) cascades to recover the network structure and the probability of success is approaching 1 only in a rate polynomial in the number of cascades. Additionally, they study trees and bounded-degree networks and show that, if the cascade sources are chosen uniformly at random, the error decreases polynomially as long as O(log N) and (d9 log2 d log N) cascades are recorded respectively. In our work, we show that, for general networks satisfying a natural incoherence condition, our method outperforms the First-Edge algorithm and the algorithm for bounded-degree networks in terms of rate and sample complexity.

Gripon & Rabbat (2013) propose a network inference method for unordered cascades, in which nodes that are infected together in the same cascade are connected by a path containing exactly the nodes in the trace, and give necessary and sufficient conditions for network inference. However, they consider a restrictive, unrealistic scenario in which cascades are all three nodes long.

2. Continuous-Time Diffusion Model

In this section, we revisit the continuous-time generative model for cascade data introduced by Gomez-Rodriguez et al. (2011). The model associates each edge j → i with a transmission function, f(ti|tj; αij) = f(ti − tj; αji), a density over time parameterized by αji. This is in contrast to previous discrete-time models which associate each edge with a fixed infection probability (Kempe et al., 2003). Moreover, it also differs from discrete-time models in the sense that events in a cascade are not generated iteratively in rounds, but event timings are sampled directly from the transmission functions in the continuous-time model.

2.1. Cascade generative process

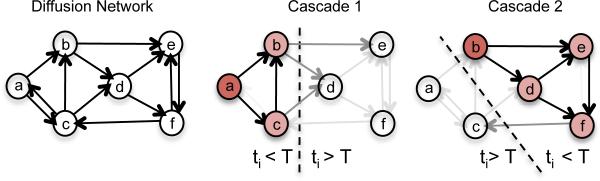

Given a directed contact network, with N nodes, the process begins with an infected source node, s, initially adopting certain contagion at time zero, which we draw from a source distribution . The contagion is transmitted from the source along her out-going edges to her direct neighbors. Each transmission through an edge entails a random transmission time, τ = tj − tj, drawn from an associated transmission function f(τ−; αji). We assume transmission times are independent, possibly discovers tributed differently across edges, and, in some cases, can be arbitrarily large, τ → ∞. Then, the infected neighbors transmit the contagion to their respective neighbors, and the process continues. We assume that an infected node remains infected for the entire diffusion process. Thus, if a node i is infected by multiple neighbors, only the neighbor that first infects node i will be the true parent. Figure 1 illustrates the process.

Figure 1.

The diffusion network structure (left) is unknown and we only observe cascades, which are N-dimensional vectors recording the times when nodes get infected by contagions that spread (right). Cascade 1 is (ta, tb, tc, ∞, ∞, ∞), where ta < tc < tb, and cascade 2 is (∞, tb, ∞, td, te, tf), where tb < td < te < tf. Each cascade contains a source node (dark red), drawn from a source distribution , as well as infected (light red) and uninfected (white) nodes, and it provides information on black and dark gray edges but does not on light gray edges.

Observations from the model are recorded as a set Cn of cascades {t1, . . . , tn}. Each cascade tc is an N-dimensional vector recording when nodes are infected, . Symbol ∞ labels nodes that are not infected during observation window [0, T c] – it does not imply they are never infected. The ‘clock’ is reset to 0 at the start of each cascade. We assume T c = T for all cascades; the results generalize trivially.

2.2. Likelihood of a cascade

Gomez-Rodriguez et al. (2011) showed that the likelihood of a cascade t under the continuous-time independent cascade model is

| (1) |

where A = {αji} denotes the collection of parameters, is the survival function and H(ti|tj; αji) = f(ti|tj; αji)/S(ti|tj; αji) is the hazard function. The survival terms in the first line account for the probability that uninfected nodes survive to all infected nodes in the cascade up to T and the survival and hazard terms in the second line account for the likelihood of the infected nodes. Then, assuming cascades are sampled independently, the likelihood of a set of cascades is the product of the likelihoods of individual cascades given by Eq. 1. For notational simplicity, we define y(ti | tk; αki) := log S(ti|tk; αki), and if ti ≤ T and 0 otherwise.

3. Network Inference Problem

Consider an instance of the continuous-time diffusion model defined above with a contact network and associated parameters . We denote the set of parents of node i as with cardinality and the minimum positive transmission rate as . Let Cn be a set of n cascades sampled from the model, where the source of each cascade is drawn from a source distribution . Then, the network inference problem consists of fin-ding the directed edges and the associated parameters using only the temporal information from the set of cascades Cn.

This problem has been cast as a maximum likelihood estimation problem (Gomez-Rodriguez et al., 2011)

| (2) |

where the inferred edges in the network correspond to those pairs of nodes with non-zero parameters, i.e. .

In fact, the problem in Eq. 2 decouples into a set of independent smaller subproblems, one per node, where we infer the parents of each node and the parameters associated with these incoming edges. Without loss of generality, for a particular node i, we solve the problem

| (3) |

where αi := {αji | j = 1, . . . , N, i ≠ j are the relevant variables, and corresponds to the terms in Eq. 2 involving αi (also see Table 1 for the definition of g(· ; αi)). In this subproblem, we only need to consider a super-neighborhood of i with cardinality , where is the set of upstream nodes from which i is reachable, is the set of nodes which are reachable from at least one node . Here, we consider a node i to be reachable from a node j if and only if there is a directed path from j to i. We can skip all nodes in from our analysis because they will never be infected in a cascade before i, and thus, the maximum likelihood estimation of the associated transmission rates will always be zero (and correct).

Table 1.

Functions.

| Function | Infected node (ti < T) | Uninfected node (ti > T) |

|---|---|---|

| gi(t; α) | log h(t; α) + ∑j:tj < ti y(ti|tj; αj) | ∑j:tj < T y(T|tj; αj) |

| [∇y(t; α)]k | –y′(ti|tk; αk) | –y′(T|tk; αk) |

| [D(t; α)]kk | –y″(ti|tk; αk) – h(t; α)–1 H″(ti|tk; αk) | –y″(T|tk; αk) |

Below, we show that, as n → ∞, the solution, , of the problem in Eq. 3 is a consistent estimator of the true parameter . However, it is not clear whether it is possible to recover the true network structure with this approach given a finite amount of cascades and, if so, how many cascades are needed. We will show that by adding an -regularizer to the objective function and solving instead the following optimization problem

| (4) |

we can provide finite sample guarantees for recovering the network structure (and parameters). Our analysis also shows that by selecting an appropriate value for the regularization parameter λn, the solution of Eq. 4 successfully recovers the network structure with probability approaching 1 exponentially fast in n.

In the remainder of the paper, we will focus on estimating the parent nodes of a particular node i. For simplicity, we will use α = αi, αj = αji, , , , d = di, pi = p and .

4. Consistency

Can we recover the hidden network structures from the observed cascades?

The answer is yes. We will show this by proving that the estimator provided by Eq. 3 is consistent, meaning that as the number of cascades goes to infinity, we can always recover the true network structure.

More specifically, Gomez-Rodriguez et al. (2011) showed that the network inference problem defined in Eq. 3 is convex in α if the survival functions are log-concave and the hazard functions are concave in α. Under these conditions, the Hessian matrix, , can be expressed as the sum of a nonnegative diagonal matrix Dn and the outer product of a matrix Xn(α) with itself, i.e.,

| (5) |

Here the diagonal matrix is a sum over a set of diagonal matrices D(tc; α), one for each cascade c (see Table 1 for the definition of its entries); and Xn(α) is the Hazard matrix

| (6) |

with each column X(tc; α) := h(tc; α)−1∇ αh(tc; α). Intuitively, the Hessian matrix captures the co-occurrence information of nodes in cascades. Then, we can prove

Theorem 1

If the source probability is strictly positive for all , then, the maximum estimator given likelihood by the solution of Eq. 3 is consistent.

Proof

We check the three criteria for consistency: continuity, compactness and identification of the objective function (Newey & McFadden, 1994). Continuity is obvious. For compactness, since L → −∞ for both αij → 0 and αij → ∞ for all i, j so we lose nothing imposing upper and lower bounds thus restricting to a compact subset. For the identification condition, , we use Lemma 9 and 10 (refer to Appendices A and B), which establish that Xn(α) has full row rank as n → ∞, and hence is positive definite.

5. Recovery Conditions

In this section, we will find a set of sufficient conditions on the diffusion model and the cascade sampling process under which we can recover the network structure from finite samples. These results allow us to address two questions:

Are there some network structures which are more difficult than others to recover?

What kind of cascades are needed for the network structure recovery?

The answers to these questions are intertwined. The difficulty of finite-sample recovery depends crucially on an incoherence condition which is a function of both network structure, parameters of the diffusion model and the cascade sampling process. Intuitively, the sources of the cascades in a diffusion network have to be chosen in such a way that nodes without parent-child relation should co-occur less often compared to nodes with such relation. Many commonly used diffusion models and network structures can be naturally made to satisfy this condition.

More specifically, we first place two conditions on the Hessian of the population log-likelihood, , where the expectation here is taken over the distribution of the source nodes, and the density f(tc|s) of the cascades tc given a source node s. In this case, we will further denote the Hessian of evaluated at the true model parameter α* as . Then, we place two conditions on the Lipschitz continuity of X(tc; α), and the boundedness of X(tc; α*) and ∇g(tc; α*) at the true model parameter α*. For simplicity, we will denote the subset of indexes associated to node i's true parents as S, and its complement as Sc. Then, we use to denote the sub-matrix of indexed by S and the set of parameters indexed by S.

Condition 1 (Dependency condition)

There exists constants Cmin > 0 and Cmax > 0 such that and where min (·) and Λmax(·) return the leading and the bottom eigenvalue of its argument respectively. This assumption ensures that two connected nodes co-occur reasonably frequently in the cascades but are not deterministically related.

Condition 2 (Incoherence condition)

There exists ε (0, 1] such that where . This assumption captures the intuition that, node i and any of its neighbors should get infected together in a cascade more often than node i and any of its non-neighbors.

Condition 3 (Lipschitz Continuity)

For any feasible cascade tc, the Hazard vector X(tc; α) is Lipschitz continuous in the domain ,

where k1 is some positive constant. As a consequence, the spectral norm of the difference, n−1/2(Xn(β) − Xn(α)), is also bounded (refer to appendix C), i.e.,

| (7) |

Furthermore, for any feasible cascade tc, D(α)jj is Lipschitz continuous for all ,

where k2 is some positive constant.

Condition 4 (Boundedness)

For any feasible cascade tc, the absolute value of each entry in the gradient of its log-likelihood and in the Hazard vector, as evaluated at the true model parameter α*, is bounded,

where k3 and k4 are positive constants. Then the absolute value of each entry in the Hessian matrix , is also bounded .

Remarks for condition 1

As stated in Theorem 1, as long as the source probability is strictly positive for all , the maximum likelihood formulation is strictly convex and thus there exists Cmin > 0 such that . Moreover, condition 4 implies that there exists Cmax > 0 such that .

Remarks for condition 2

The incoherence condition depends, in a non-trivial way, on the network structure, diffusion parameters, observation window and source node distribution. Here, we give some intuition by studying three small canonical examples.

First, consider the chain graph in Fig. 2(a) and assume that we would like to find the incoming edges to node 3 when T → ∞. Then, it is easy to show that the incoherence condition is satisfied if (P0 + P1)/(P0 + P1 + P2) < 1 − ε and P0/(P0 +P1 +P2) < 1 − ε denotes , where Pi the probability of a node i to be the source of a cascade. Thus, for example, if the source of each cascade is chosen uniformly at random, the inequality is satisfied. Here, the incoherence condition depends on the source node distribution.

Figure 2.

Example networks.

Second, consider the directed tree in Fig. 2(b) and assume that we would like to find the incoming edges to node 0 when T → ∞. Then, it can be shown that the incoherence condition is satisfied as long as (1) P1 > 0, (2) (P2 > 0) or (P5 > 0 and P6 > 0), and (3) P3 > 0. As in the chain, the condition depends on the source node distribution.

Finally, consider the star graph in Fig. 2(c), with exponential edge transmission functions, and assume that we would like to find the incoming edges to a leave node i when T < ∞. Then, as long as the root node has a nonzero probability P0 > 0 of being the source of a cascade, it can be shown that the incoherence condition reduces to the inequalities , which always holds for some ε > 0. If T → ∞, then the condition holds whenever ε < α0i/(α0i + maxj:j≠i α0j). Here, the larger the ratio maxj:j≠i α0j//α0i is, the smaller the maximum value of ε for which the incoherence condition holds. To summarize, as long as P0 > 0, there is always some ε > 0 for which the condition holds, and such ε value depends on the time window and the parameters α0j.

Remarks for conditions 3 and 4

Well-known pairwise transmission likelihoods such as exponential, Rayleigh or Power-law, used in previous work (Gomez-Rodriguez et al., 2011), satisfy conditions 3 and 4.

6. Sample Complexity

How many cascades do we need to recover the network structure?

We will answer this question by providing a sample complexity analysis of the optimization in Eq. 4. Given the conditions spelled out in Section 5, we can show that the number of cascades needs to grow polynomially in the number of true parents of a node, and depends only logarithmically on the size of the network. This is a positive result, since the network size can be very large (millions or billions), but the number of parents of a node is usually small compared the network size. More specifically, for each individual node, we have the following result:

Theorem 2

Consider an instance of the continuous-time diffusion model with parameters and associated edges ε* such that the model satisfies condition 1-4, and let Cn be a set of n cascades drawn from the model. Suppose that the regularization parameter λn is selected to satisfy

| (8) |

Then, there exist positive constants L and K, independent of (n, p, d), such that if

| (9) |

then the following properties hold with probability at least :

For each node , the -regularized network infe rence problem defined in Eq. 4 has a unique solution, and so uniquely specifies a set of incoming edges of node i.

For each node , the estimated set of incoming edges does not include any false edges and include all true edges.

Furthermore, suppose that the finite sample Hessian matrix satisfies conditions 1 and 2. Then there exist positive constants L and K, independent of (n, p, d), such that the sample complexity can be improved to n > Ld2 log p with other statements remain the same.

Remarks

The above sample complexity is proved for each node separately for recovering its parents. Using a union bound, we can provide the sample complexity for recovering the entire network structure by joining these parent-child relations together. The resulting sample complexity and the choice of regularization parameters will remain largely the same, except that the dependency on d will change from d to dmax (the largest number of parents of a node), and the dependency on p will change from log p to 2 log N (N the number of nodes in the network).

6.1. Outline of Analysis

The proof of Theorem 2 uses a technique called primal-dual witness method, previously used in the proof of sparsistency of Lasso (Wainwright, 2009) and high-dimensional Ising model selection (Ravikumar et al., 2010). To the best of our knowledge, the present work is the first that uses this technique in the context of diffusion network inference. First, we show that the optimal solutions to Eq. 4 have shared sparsity pattern, and under a further condition, the solution is unique (proven in Appendix D):

Lemma 3

Suppose that there exists an optimal primal-dual solution to Eq. 4 with an associated subgradient vector ẑ such that . Then, any optimal primal solution must have . Moreover, if the Hessian sub-matrix is strictly positive definite, then is the unique optimal solution.

Next, we will construct a primal-dual vector along with an associated subgradient vector ẑ. Furthermore, we will show that, under the assumptions on (n, p, d) stated in Theorem 2, our constructed solution satisfies the KKT optimality conditions to Eq. 4, and the primal vector has the same sparsity pattern as the true parameter α* , i.e.,

| (10) |

| (11) |

Then, based on Lemma 3, we can deduce that the optimal solution to Eq. 4 correctly recovers the sparsisty pattern of α* , and thus the incoming edges to node i.

More specifically, we start by realizing that a primal-dual optimal solution to Eq. 4 must satisfy the generalized Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) conditions (Boyd & Vandenberghe, 2004):

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

where and z̃ denotes the subgradient of the -norm.

Suppose the true set of parent of node i is S. We construct the primal-dual vector and the associated subgradient vector ẑ in the following way

- We set as the solution to the partial regularized maximum likelihood problem

Then, we set as the dual solution associated to the primal solution .(17) - We set , so that condition (11) holds, and , where μ* is the optimal dual solution to the following problem:

Thus, our construction satisfies condition (14).(18) We obtain from (12) by substituting in the constructed , and ẑS.

Then, we only need to prove that, under the stated scalings of (n, p, d), with high-probability, the remaining KKT conditions (10), (13), (15) and (16) hold.

For simplicity of exposition, we first assume that the dependency and incoherence conditions hold for the finite sample Hessian matrix . Later we will lift this restriction and only place these conditions on the population Hessian matrix . The following lemma show that our constructed solution satisfies condition (10):

Lemma 4

Under condition 3, if the regularization parameter is selected to satisfy

and , then,

as long as . Based on this lemma, we can then further show that the KKT conditions (13) and (15) also hold for the constructed solution. This can be trivially deduced from condition (10) and (11), and our construction steps (a) and (b). Note that it also implies that , and hence .

Proving condition (16) is more challenging. We first provide more details on how to construct mentioned in step (c). We start by using a Taylor expansion of Eq. 12,

| (19) |

where Rn is a remainder term with its j-th entry

and with θj ∈ [0, 1] according to the mean value theorem. Rewriting Eq. 19 using block matrices

and, after some algebraic manipulation, we have

Next, we upper bound using the triangle inequality

and we want to prove that this upper bound is smaller than 1. This can be done with the help of the following two lemmas (proven in Appendices F and G):

Lemma 5

Given ε ∈ (0, 1] from the incoherence condition, we have,

which converges to zero at rate as long as .

Lemma 6

Given ε ∈ (0, 1] from the incoherence condition, if conditions 3 and 4 holds, λn is selected to satisfy

where , and , then, , as long as .

Now, applying both lemmas and the incoherence condition on the finite smaple Hessian matrix , we have

and thus condition (16) holds.

A possible choice of the regularization parameter λn and cascade set size n such that the conditions of the Lemmas 4-6 are satisfied is and .

Last, we lift the dependency and incoherence conditions imposed on the finite sample Hessian matrix . We show that if we only impose these conditions in the corresponding population matrix , then they will also hold for with high probability (proven in Appendices H and I).

Lemma 7

If condition 1 holds for , then, for any δ > 0,

where A1, A2, B1 and B2 are constants independent of (n, p, d).

Lemma 8

If , then,

where K is a constant independent of (n, p, d).

Note in this case the cascade set size need to increase to n > Ld3 log p, where L is a sufficiently large positive constant independent of (n, p, d), for the error probabilities on these last two lemmas to converge to zero.

7. Efficient soft-thresholding algorithm

Can we design efficient algorithms to solve Eq. (4) for network recovery?

Here, we will design a proximal gradient algorithm which is well suited for solving non-smooth, constrained, large-scale or high-dimensional convex optimization problems (Parikh & Boyd, 2013). Moreover, they are easy to understand, derive, and implement. We first rewrite Eq. 4 as an unconstrained optimization problem:

where the non-smooth convex function g(α) = λn ∥α∥1 if α ≥ 0 and +∞ otherwise. Here, the general recipe from Parikh & Boyd (2013) for designing proximal gradient algorithm can be applied directly.

Algorithm 1 summarizes the resulting algorithm. In each iteration of the algorithm, we need to compute (Table 1) and the proximal operator proxLkg(v), where Lk is a step size that we can set to a constant value L or find using a simple line search (Beck & Teboulle, 2009). Using Moreau's decomposition and the conjugate function g* , it is easy to show that the proximal operator for our particular function g(·) is a soft-thresholding operator, (v − λnLk)+, which leads to a sparse optimal solution , as desired.

8. Experiments

In this section, we first illustrate some consequences of Th. 2 by applying our algorithm to several types of networks, parameters (n, p, d), and regularization parameter λn. Then, we compare our algorithm to two different state-of-the-art algorithms: NetRate (Gomez-Rodriguez et al., 2011) and First-Edge (Abrahao et al., 2013).

Experimental Setup

We focus on synthetic networks that mimic the structure of real-world diffusion networks – in particular, social networks. We consider two models of directed real-world social networks: the Forest Fire model (Barabási & Albert, 1999) and the Kronecker Graph model (Leskovec et al., 2010), and use simple pairwise transmission models such as exponential, power-law or Rayleigh. We use networks with 128 nodes and, for each edge, we draw its associated transmission rate from a uniform distribution U(0.5, 1.5). We proceed as follows: we generate a network and transmission rates A*, simulate a set of cascades and, for each cascade, record the node infection times. Then, given the infection times, we infer a network . Finally, when we illustrate the consequences of Th. 2, we evaluate the accuracy of the inferred neighborhood of a node using probability of success , estimated by running our method of 100 independent cascade sets. When we compare our algorithm to NetRate and First-Edge, we use the F1 score, which is defined as 2P R/(P + R), where precision (P) is the fraction of edges in the inferred network present in the true network , and recall (R) is the fraction of edges of the true network present in the inferred network .

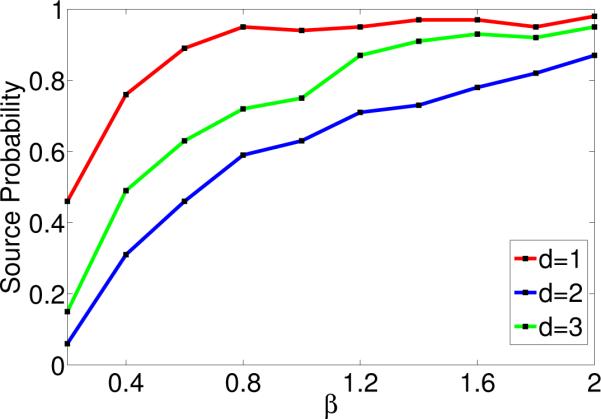

Parameters

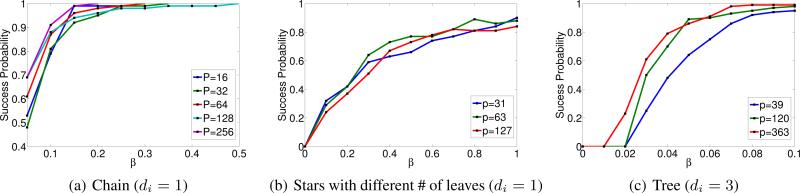

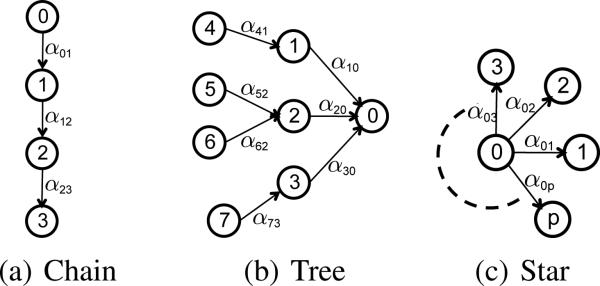

(n, p, d) According to Th. 2, the number of cascades that are necessary to successfully infer the incoming edges of a node will increase polynomially to the node's neighborhood size di and logarithmically to the super-neighborhood size pi. Here, we infer the incoming links of nodes of a hierarchical Kronecker network with the same in-degree (di = 3) but different super-neighboorhod set sizes pi under different scalings β of the number of cascades n = 10βd log p and choose the regularization parameter λn as a constant factor of as suggested by Th. 2. We used an exponential transmission model and T = 5. Fig. 3(a) summarizes the results, where, for each node, we used cascades which contained at least one node in the super-neighborhood of the node under study. As predicted by Th. 2, very different p values lead to curves that line up with each other quite well.

Figure 3.

Success probability vs. # of cascades.

Regularization parameter

λn Our main result indicates that the regularization parameter λn should be a constant factor of . Fig. 3(b) shows the success probability of our algorithm against different scalings K of the regularization parameter for different types of networks using 150 cascades and T = 5. We find that for sufficiently large λn, the success probability flat-tens, as expected from Th. 2. It flattens at values smaller than one because we used a fixed number of cascades n, which may not satisfy the conditions of Th. 2.

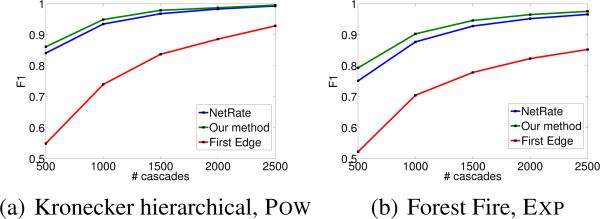

Comparison with NetRate and First-Edge

Fig. 4 compares the accuracy of our algorithm, NETRATE and First-Edge against number of cascades for a hierarchical Kronecker network with power-law transmission model and a Forest Fire network with exponential transmission model, with an observation window T = 10. Our method outperforms both competitive methods, finding especially striking the competitive advantage with respect to First-Edge.

Figure 4.

F1-score vs. # of cascades.

9. Conclusions

Our work contributes towards establishing a theoretical foundation of the network inference problem. Specifically, we proposed a -regularized maximum likelihood inference method for a well-known continuous-time diffusion model and an efficient proximal gradient implementation, and then show that, for general networks satisfying a natural incoherence condition, our method achieves an exponentially decreasing error with respect to the number of cascades as long as O(d3 log N) cascades are recorded.

Our work also opens many interesting venues for future work. For example, given a fixed number of cascades, it would be useful to provide confidence intervals on the inferred edges. Further, given a network with arbitrary pairwise likelihoods, it is an open question whether there always exists at least one source distribution and time window value such that the incoherence condition is satisfied, and, and if so, whether there is an efficient way of finding this distribution. Finally, our work assumes all activations occur due to network diffusion and are recorded. It would be interesting to allow for missing observations, as well as activations due to exogenous factors.

A. Proof of Lemma 9

Lemma 9

Given log-concave survival functions and concave hazard functions in the parameter(s) of the pairwise transmission likelihoods, then, a sufficient condition for the Hessian matrix to be positive definite is that the hazard matrix Xn(α) is non-singular.

Proof

Using Eq. 5, the Hessian matrix can be expressed as a sum of two matrices, Dn(α) and Xn(α)Xn(α)Τ. The matrix Dn(α) is trivially positive semidefinite by log-concavity of the survival functions and concavity of the hazard functions. The matrix Xn(α)Xn(α)Τ is positive definite matrix since Xn(α) is full rank by assumption. Then, the Hessian matrix is positive definite since it is a sum a positive semidefinite matrix and a positive definite matrix.

B. Proof of Lemma 10

Lemma 10

If the source probability is strictly positive for all , then, for an arbitrarily large number of cascades n → ∞, there exists an ordering of the nodes and cascades within the cascade set such that the hazard matrix Xn(α) is non-singular.

Proof

In this proof, we find a labeling of the nodes (row indices in Xn(α)) and ordering of the cascades (column indices in Xn(α)), such that, for an arbitrary large number of cascades, we can express the matrix Xn(α) as [T B], where is an upper triangular with nonzero diagonal elements and . And, therefore, Xn(α) has full rank (rank p). We proceed first by sorting nodes in and then continue by sorting nodes in :

• Nodes in

For each node , consider the set of cascades Cu in which u was2a source R and i got infected. Then, rank each node u according to the earliest position in which node i got infected across all cascades in Cu in decreasing order, breaking ties at random. For example, if a node u was, at least once, the source of a cascade in which node i got infected just after the source, but in contrast, node v was never the source of a cascade in which node i got infected the second, then node u will have a lower index than node v. Then, assign row k in the matrix Xn(α) to node in position k and assign the first d columns to the corresponding cascades in which node i got infected earlier. In such ordering, Xn(α)mk = 0 for all m < k and Xn(α)kk≠ 0.

• Nodes in

Similarly as in the first step, and assign them the rows d + 1 to p. Moreover, we assign the columns d + 1 to p to the corresponding cascades in which node i got infected earlier. Again, this ordering satisfies that Xn(α)mk = 0 for all m < k and Xn(α)kk≠ 0. Finally, the remaining columns n − p can be assigned to the remaining cascades at random.

This ordering leads to the desired structure [T B], and thus it is non-singular.

C. Proof of Eq 7

If the Hazard vector X(tc; α) is Lipschitz continuous in the domain ,

where k1 is some positive constant. Then, we can bound the spectral norm of the difference, , in the domain as follows:

D. Proof of Lemma 3

By Lagrangian duality, the regularized network inference problem defined in Eq. 4 is equivalent to the following constrained optimization problem:

| (20) |

where C(λn) < ∞ is a positive constant. In this alternative formulation, λn is the Lagrange multiplier for the second constraint. Since λn is strictly positive, the constraint is active at any optimal solution, and thus ∥α∥1 is constant across all optimal solutions.

Using that is a differentiable convex function by assumption and {α : αji ≥ 0, ∥αi∥1 ≤ C(λn)} is a convex set, we have that is constant across optimal primal solutions (Mangasarian , 1988). Moreover, any optimal primal-dual solution in the original problem must satisfy the KKT conditions in the alternative formulation defined by Eq. 20, in particular,

where μ ≥ 0 are the Lagrange multipliers associated to the non negativity constraints and z denotes the subgradient of the -norm.

Consider the solution such that and thus . Now, assume there is an optimal primal solution such that for some j ∈ Sc, then, using that the gradient must be constant across optimal solutions, it should hold that where by complementary slackness, which implies . Since by assumption, this leads to a contradiction. Then, any primal solution must satisfy for the gradient to be constant across optimal solutions.

Finally, since for all optimal solutions, we can consider the restricted optimization problem defined in Eq. 17. If the Hessian sub-matrix is strictly positive definite, then this restricted optimization problem is strictly convex and the optimal solution must be unique.

E. Proof of Lemma 4

To prove this lemma, we will first construct a function

whose domain is restricted to the convex set . By construction, G(uS) has the following properties

It is convex with respect to uS.

Its minimum is obtained at . That is G(ûS) ≤ G(uS), ∀uS =ûS.

G(ûS) ≤ G(0) = 0.

Based on property 1 and 3, we deduce that any point in the segment, , connecting ûS and 0 has G(ũS) ≤ 0. That is

Next, we will find a sphere centered at 0 with strictly positive radius , such that function G(uS) > 0 (strictly positive) on . We note that this sphere can not intersect with the segment since the two sets have strictly different function values. Furthermore, the only possible configuration is that the segment is contained inside the sphere entirely, leading us to conclude that the end point is also within the sphere. That is .

In the following, we will provide details on finding such a suitable B which will be a function of the regularization parameter λn and the neighborhood size d. More specifically, we will start by applying a Taylor series expansion and the mean value theorem,

| (21) |

where b ∈ [0, 1]. We will show that G(uS) > 0 by bounding below each term of above equation separately.

We bound the absolute value of the first term using the assumption on the gradient, ,

| (22) |

We bound the absolute value of the last term using the reverse triangle inequality.

| (23) |

Bounding the remaining middle term is more challenging. We start by rewriting the Hessian as a sum of two matrices, using Eq. 5,

Now, we introduce two additional quantities,

and rewrite q as

Next, we use dependency condition,

and proceed to bound T1 and T2 separately. First, we bound T1 using the Lipschitz condition,

Then, we use the dependency condition, the Lipschitz condition and the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality to bound T2,

where we note that applying the Lipschitz condition implies assuming . Next, we incorporate the bounds of T1 and T2 to lower bound q,

| (24) |

Now, we set , where K is a constant that we will set later in the proof, and select the regularization parameter λn to statisfy . Then,

In the last step, we set the constant , and we have

as long as

Finally, convexity of G(uS) yields

F. Proof of Lemma 5

Define and . Now, using the KKT conditions and condition 4 (Boundedness), we have that and , respectively.

Thus, Hoeffding's inequality yields

and then,

G. Proof of Lemma 6

We start by factorizing the Hessian matrix, using Eq. 5,

where,

Next, we proceed to bound each term separately. Since where θj ∈ [0, 1], and (Lemma 4), it holds that . Then, we can use condition 3 (Lipschitz Continuity) to bound .

| (25) |

However, bounding term is more difficult. Let us start by rewriting as follows.

where,

Next, we bound each term separately. For the first term, we first apply Cauchy inequality,

and then use condition 3 (Lipschtiz Continuity) and 4 (Boundedness),

For the second term, we also start by applying Cauchy inequality,

and then use condition 3 (Lipschtiz Continuity),

Last, for third term, once more we start by applying Cauchy inequality,

and then apply condition 1 (Dependency Condition) and condition 3 (Lipschitz Continuity),

Now, we combine the bounds,

where

Finally, using Lemma 4 and selecting the regularization parameter λn to satisfy yields:

H. Proof of Lemma 7

We will first bound the difference in terms of nuclear norm between the population Fisher information matrix and the sample mean cascade log-likelihood . Define and . Then, we can express the difference between the population Fisher information matrix and the sam ple mean cascade log-likelihood as:

Since by condition 4, we can apply Hoeffding's inequality to each zjk,

| (26) |

and further,

| (27) |

where . Now, we bound the maximum eigenvalue of as follows:

where y is unit-norm maximal eigenvector of . Therefore,

and thus,

Reasoning in a similar way, we bound the minimum eigen- value of :

I. Proof of Lemma 8

We start by decomposing as follows:

where,

and . Now, we bound each term separately. The fourth term, A4, is the easiest to bound, using simply the incoherence condition:

To bound the other terms, we need the following lemma:

Lemma 11

For any ≥ 0 and constants K and K′, the following bounds hold:

| (28) |

| (29) |

| (30) |

Proof

We start by proving the first confidence interval. By definition of infinity norm of a matrix, we have:

where and, for the last inequality, we used the union bound and the fact that Sc ≤ p − d. Furthermore,

Thus,

At this point, we can obtain the first confidence bound by using Eq. 26 with β = δ/d in the above equation. The proof of the second confidence bound is very similar and we omit it for brevity. To prove the last confidence bound, we proceed as follows:

Next, we bound each term of the final expression in the above equation separately. The first term can be bounded using Eq. 27:

The second term can be bounded using Lemma 6:

Then, the third confidence bound follows.

Control of A1. We start by rewriting the term A1 as

and further,

Next, using the incoherence condition easily yields:

Now, we apply Lemma 6 with δ = Cmin/2 to have that with probability greater than , and then use Eq. 30 with to conclude that

Control of A2. We rewrite the term A2 as , and then use Eqs. 28 and 29 with to conclude that

Control of A3. We rewrite the term A3 as

We then apply Eq. 28 with to conclude that

and thus,

J. Additional experiments

Parameters

(n, p, d). Figure 5 shows the success probability at inferring the incoming links of nodes on the same type of canonical networks as depicted in Fig. 2. We choose nodes the same in-degree but different super-neighboorhod set sizes pi and experiment with different scalings β of the number of cascades n = 10 βd log p. We set the regularization parameter λn as a constant factor of as suggested by Theorem 2 and, for each node, we used cascades which contained at least one node in the super-neighborhood of the node under study. We used an exponential transmission model and time window T = 10. As predicted by Theorem 2, very different p values lead to curves that line up with each other quite well.

Figure 5.

Success probability vs. # of cascades. Different super-neighborhood sizes pi.

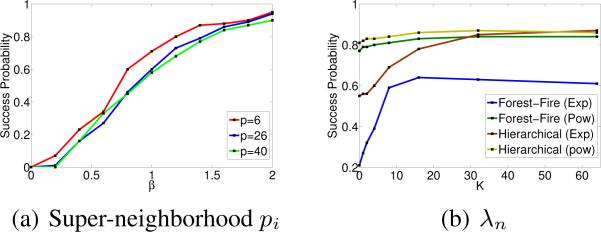

Figure 6 shows the success probability at inferring the incoming links of nodes of a hierarchical Kronecker network with equal super neighborhood size (pi = 70) but different in-degree (di) under different scalings β of the number of cascades n = 10 d log p and choose the regularization parameter λn as a constant factor of as suggested by Theorem 2. We used an exponential transmission model and time window T = 5. As predicted by Theorem 2, in this case, different d values lead to noticeably different curves.

Figure 6.

Success probability vs. # of cascades. Different in-degrees di.

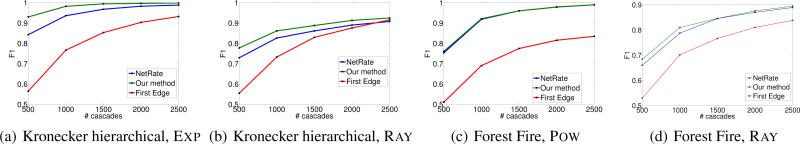

Comparison with NetRate and First-Edge

Figure 7 compares the accuracy of our algorithm, NETRATE and First-Edge against number of cascades for different type of networks and transmission models. Our method typically outperforms both competitive methods. We find especially striking the competitive advantage with respect to First-Edge, however, this may be explained by comparing the sample complexity results for both methods: First-Edge needs O(Nd log N) cascades to achieve a probability of success approaching 1 in a rate polynomial in the number of cascades while our method needs O(d3 log N) to achieve a probability of success approaching 1 in a rate exponential in the number of cascades.

Figure 7.

F1-score vs. # of cascades.

Algorithm 1.

-regularized network inference

| Require: Cn, λn, K, L |

| for all do |

| k = 0 |

| while k < K do |

| k = k + 1 |

| end while |

| end for |

| return |

Acknowledgement

This research was supported in part by NSF/NIH BIG-DATA 1R01GM108341-01, NSF IIS1116886, and a Raytheon faculty fellowship to L. Song.

Footnotes

Proceedings of the 31 st International Conference on Machine Learning, Beijing, China, 2014. JMLR: W&CP volume 32.

Contributor Information

Hadi Daneshmand, Email: HADI.DANESHMAND@TUE.MPG.DE.

Manuel Gomez-Rodriguez, Email: MANUELGR@TUE.MPG.DE.

Le Song, Email: LSONG@CC.GATECH.EDU.

Bernhard Schölkopf, Email: BS@TUE.MPG.DE.

References

- Abrahao B, Chierichetti F, Kleinberg R, Panconesi A. Trace complexity of network inference. KDD. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Adar E, Adamic LA. Tracking Information Epidemics in Blogspace. Web Intelligence. 2005:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Barabási A-L, Albert R. Emergence of Scaling in Random Networks. Science. 1999;286:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Teboulle M. Gradient-based algorithms with applications to signal recovery. Convex Optimization in Signal Processing and Communications. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Boyd SP, Vandenberghe L. Convex optimization. Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Du N, Song L, Smola A, Yuan M. Learning Networks of Heterogeneous Influence. NIPS. 2012a [Google Scholar]

- Du N, Song L, Woo H, Zha H. Uncover Topic-Sensitive Information Diffusion Networks. AISTATS. 2012b [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Rodriguez M, Leskovec J, Krause A. Inferring Networks of Diffusion and Influence. KDD. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Rodriguez M, Balduzzi D, Schölkopf B. Uncovering the Temporal Dynamics of Diffusion Networks. ICML. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Rodriguez Manuel. Ph.D. Thesis. Stanford University & MPI for Intelligent Systems; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gripon V, Rabbat M. Reconstructing a graph from path traces. arXiv. 2013;1301.6916 [Google Scholar]

- Kempe D, Kleinberg JM, Tardos É. Maximizing the Spread of Influence Through a Social Network. KDD. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Leskovec J, Chakrabarti D, Kleinberg J, Faloutsos C, Ghahramani Z. Kronecker Graphs: An Approach to Modeling Networks. JMLR. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Mangasarian OL. A simple characterization of solution sets of convex programs. Operations Research Letters. 1988;7(1):21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Netrapalli P, Sanghavi S. Finding the Graph of Epidemic Cascades. ACM SIGMETRICS. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Newey WK, McFadden DL. Large Sample Estimation and Hypothesis Testing. Handbook of Econometrics. 1994;4:2111–2245. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh Neal, Boyd Stephen. Proximal algorithms. Foundations and Trends in Optimization. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar P, Wainwright MJ, Lafferty JD. High-dimensional ising model selection using l1-regularized logistic regression. The Annals of Statistics. 2010;38(3):1287– 1319. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. fourth edition Free Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Kimura M, Ohara K, Motoda H. Learning continuous-time information diffusion model for social behavioral data analysis. Advances in Machine Learning. 2009:322–337. [Google Scholar]

- Snowsill T, Fyson N, Bie T. De, Cristianini N. Refining Causality: Who Copied From Whom? KDD. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright MJ. Sharp thresholds for high-dimensional and noisy sparsity recovery using l1-constrained quadratic programming (lasso). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 2009;55(5):2183–2202. [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Ermon S, Hopcroft J. Feature-enhanced probabilistic models for diffusion network inference. ECML PKDD. 2012 [Google Scholar]