Abstract

Background:

Bosnia and Herzegovina became an independent state (6th April 1992) after referendum for the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina which was held on 29 February and 1 March 1992. On the referendum voted total 2,073,568 voters (63.6% turnout) and 99.7% were in favor of independence, and 0.3% against. According to the provisions of the peace agreement, particularly in Annex IV of the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the country continues to exist as an independent state. Like all others institutions, even the health-care system was separated between Federation and the other part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The right to social and medical services in Bosnia and Herzegovina is realized entities level and regulated by entity laws on social and health-care.

Aims:

The aim was to explore how immigrants born in Bosnia and Herzegovina and living as refugees in their own country experience different institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina with the special focus on the health-care system. We also investigated the mental health of those immigrants.

Patients and Methods:

Focus-group interviews, with 21 respondents born in Bosnia and Herzegovina and living as refugees in their own country, were carried out. Content analysis was used for interpretation of the data.

Results:

The analysis resulted in two categories: the health-care in pre-war period and the health-care system in post-war period. The health-care organization, insurance system, language differences, health-care professional’s attitude and corruption in health-care system were experienced as negative by all respondents. None of the participants saw a way out of this difficult situation and saw no glimmer of light in the tunnel. None of the participants could see any bright future in the health-care system.

Conclusion:

Health-care system should be adjusted according to the needs of both the local population born as well as the immigrants. Health-care professionals must be aware of the difficulties of living as immigrants in one’s own country. In order to provide health-care on a high level of quality, health-care professionals must meet all the expectations of the patients, and not to expect that patients should fulfil the expectations of the health-care professionals. Different educational activities, such as lectures, seminars and conferences, are needed with the purpose of the optimal use of the health-care system for people that have been forced to become refuges in their own country.

Keywords: Health-care system, Qualitative research, Experiences, Difficulties, Immigrants, War

1. INTRODUCTION

Until 1991 Bosnia and Herzegovina was geographically and politically a part of the former Yugoslavia, having 4 377 033 inhabitants. There were 43.5% Bosnians, 31.2% Serbs, 17.4% Croats, 5.5% Yugoslavs and 2.4% of others (1). As a result of the conflict or war, many people from Bosnia and Herzegovina were forced to go into exile. During the war, violence and ethnic cleansing were deliberately used to drive people from their home where they were born and had lived for generations (2). Because of the war, the whole social networking system and the infrastructure as well as the economic structure were destroyed and there was no hope for support in this context. During the war a large number of civilians were treated brutally by the former Yugoslavia army and were exposed to extreme threats and intense feelings of powerlessness (3, 4). Thousands of people experienced the traumatic events during this conflict. As a result of the war (1992-1995) in Bosnia and Herzegovina 103,000 inhabitants were killed, of which 60% civilians, 30,000 were missing, 170,000 were wounded, over 20,000 raped and over 2 million (1 300 000 in other countries all over the world and 870 000 in Bosnia and Herzegovina) became refugees or displaced persons, most of them driven from their homes in pogroms of ethnic cleansing (5, 6). Many of them still suffer from the effects of violence done by the enemy during this war (7). The traumatic effect of violence has significant negative impact on their life and their psychosocial well-being in resettlement places (8). Bosnia and Herzegovina became an independent state (6th April 1992) after referendum for the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina which was held on 29 February and 1 March 1992. On the referendum voted total 2,073,568 voters (63.6% turnout) and 99.7% were in favor of independence, and 0.3% against. According to the provisions of the peace agreement in Dayton (14th December 1995 in Paris) particularly in Annex IV of the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the country continues to exist as an independent state. The territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina consists of two entities; the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republic of Serbs. A subsequent decision of the commission for arbitration was to establish a separate administrative unit of the Brcko district of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This agreement also regulates the jurisdiction of the central government and government entities. Sarajevo remains as the capital city. The official languages are Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian. Return to Bosnia and Herzegovina began immediately after the signing of the Dayton Agreement. Since the signing by 31.12.2001, a total number of 822,779 returnees were in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the area of the Federation 628,705 or 76.4% people returned in the area of RS 183,604 people-22.3% and in Brcko district 10,470 persons, or 1.27%. At the end of year 2001 there were 3 364 825 inhabitants in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the Federation there were 2 298 501 and in the other part of the country there were 1 066 324 inhabitants. There were 48.3% Bosnians, 34.0% Serbs, 15.4% Croats, and 2.3% others (1). The data for the last census in Bosnia and Herzegovina (October 2013) have not been completed yet, but there are still around one million refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina in many countries in the world and 113 000 refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina that are refugees in their own country. Like all other institutions, even the health-care system was separated between the Federation and the other part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The right to social and medical services in Bosnia and Herzegovina is realized entities level and regulated by entity laws on social and health-care. The realization of these rights is impeded by the lack of funds in the budgets of the entities and cantons / counties that are required to provide funds for this purpose. The laws governing this area are still not in accordance with the conventions that Bosnia and Herzegovina is bound to apply. Previous studies in orthopedics around the world show significant ethnic differences in its utilization, which is not explained by differences in prevalence. Over the past two decades numerous studies have showed that African Americans receive THA less often than white Americans (9, 10). There are probably many reasons for these reported differences in use- including patient-level factors (e.g. beliefs about health), system-level factors (e.g. access to specialist care), and provider-level factors (e.g. physician bias) (11-14). Previous studies about discrimination and segregation exist, too. There is a Swedish study about differences in living conditions between South European labour migrants and Latin American refugees and those who were repatriated to Latin America. This study shows a clear ethnic segregation in housing and other living conditions between Swedes and immigrants, where Latin American refugees and repatriated Latin Americans were most vulnerable. All immigrants had increased self-rated poor health compared with those born in Sweden. Being an immigrant was a risk factor for poor health (15). There are documented findings in previous studies about the difficulties the immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina meet in the health-care systems around the world. Participants in these studies were critical about several core issues: confusion about insurance coverage, personalized quality of care, and access to primary and special care. Participants compared their experience with pre-war Bosnian health-care along these dimensions. The difficulties were present even about the language and communication (16, 17). The previous studies about immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina living as refugees in their own country were mostly about their mental health and the postwar period. (18-20).

We aimed to explore how immigrants born in Bosnia and Herzegovina who are refugees in their own country experience different institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina with the special focus on the health-care system. We also investigated the mental health of those immigrants.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Design

The study was designed as a prospective, qualitative study using data from interviews with participants from four different cities in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The immigrants were born in Kotor Varos, Travnik and Banja Luka and living in the North-West part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The data were collected through three focus group discussions (McLafferty, 2004) (21) with 7 participants in each group (four men and three women in each group).

2.2. Participants

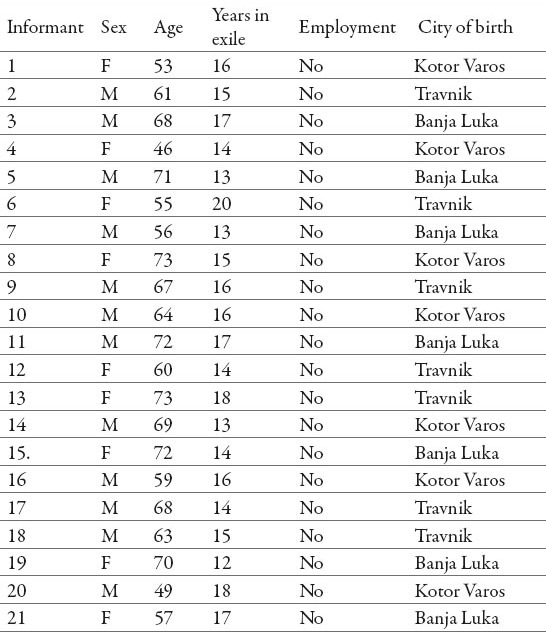

The present study is based on a qualitative design, as the study aimed to describe and analyses how immigrants and their family members experience the utilization of the institutions in Bosnia and Herzegovina with a special focus on the health-care system. Inclusion criteria were participants who were not born in their places of residence, who were more than 30 years old, had lived as refugees more than 10 years and together with their family have experiences related to the health-care system in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Twenty one persons were invited to participate in the study and all of them agreed to participate. Accordingly, twenty one persons participated in the study: twelve men and nine women, aged between 46 and 73 years (on average 63.1 years). The men in the present study were older 49-71 (on average 63.9 years) than women 46-73 (on average 62.1 years). All participants had lived as refugees between 13 and 20 years (Table 1). The first author of the study made appointments for all the interviews.

Table 1.

Demographic data of participants

2.3. Data collection

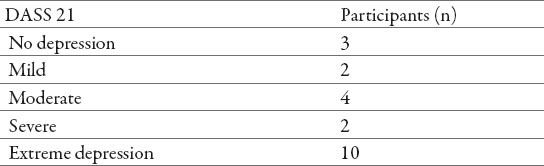

Data were collected through focus group interviews by the first author using open-ended questions, following an interview guide inspired by Kvale (22). The interviews were performed between June and August 2014. They began with small talk. The opening question was “Can you please describe your meeting with the health-care professionals? What was good and less good in the meeting? The initial questions were supplemented with other short questions like “Could you please tell me more about this? or “What do you mean with this? All contacts with the informants were arranged in collaboration with one key person in the North-West part of country located close to the place where the participants lived. Information concerning the aim and background of the study was printed and distributed to the informants, and repeated to them orally before the interview. The interviews were in group of seven persons, participants were encouraged to speak freely using their own words and the interviewer encouraged the informants to respond to questions as comprehensively as possible. The interviews were carried out in Bosnian language. The interviewer only interrupted for questions or for following-up the information given. The interviews lasted between 90 and 180 minutes and were taped, transcribed and transcribed verbatim. In order to obtain the participants’ mental health, a few minutes after the interview was finished, the participants completed the DASS 21 scale (23). The first author of the study translated the scale into Bosnian because the participants could not understand English. Categories in the scale were: No depression 0–9, mild 10–13, moderate 14–20, severe 21–27 and extremely severe 28+. Nearly half of all the respondents in the present study had extreme depression (Table 3).

Table 3.

DASS 21 Scale (Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale)

2.4. Analysis

A qualitative content analysis method, in accordance with Graneheim and Lundman (2004) was chosen for analysis and interpretation of the collected data. This method is capable of condensing a large amount of data to a limited number of themes, categories, subcategories and codes. Furthermore, interpretations of a latent content can be included. The transcripts were read carefully in order to identify the informants’ experiences and conceptions. Then, the analysis proceeded by extracting meaning units consisting of one or several words, sentences, or paragraphs containing aspects related to each other and addressing a specific topic in the material. Then meaning units that related to each other through their content and context were abstracted and grouped together into a condensed meaning unit, with a description close to the original text. The condensed text was further abstracted and labelled with a code. Thereafter, codes that referred to similar issues were grouped together, resulting in subcategories. Subcategories that focused on the same problem were brought together, in order to create more extensive conceptions which refer to an obvious issue (24). The results are presented with direct quotes from the interviews.

2.5. Ethical approval

The study conformed to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (25). Participants were informed that participation was voluntary and that confidentiality would be maintained. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the present study.

3. RESULTS

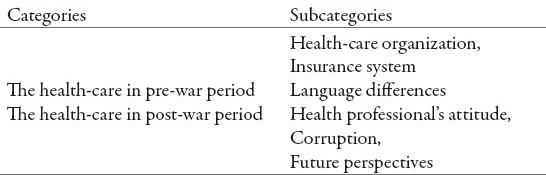

The analysis of the interviews resulted in two categories and five subcategories based on how the participants described their experiences about the health-care system. These categories, together with the subcategories, are presented in Table 2. The categories were; The health-care system in pre-war period and as well as in post-war period.

Table 2.

Overview of the categories and subcategories

3.1. The health-care in pre-war period

Despite fact that the focus of this study was on the current state of health-care system of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the majority of the participants in the present study based their answers on the period before the war started in 1992. They describe the pre-war period and the beauty of life: beautiful and economically ordered life, travelling to different places, meeting various needs, education and other wonderful things were described by all participants. All the subjects in this study described sadness and sorrow for those past times.

3.1.1. Health-care organization

The majority of the participants had different opinion about the organization and functioning of the health-care system in Bosnia and Herzegovina. They made parallels between the health-care system before the war and the health-care system of the cities where they were born as well as the parallels between their whole life before the war and the present time. The common conclusion of all the participants was that everything was better and more coherent before the war than now, eighteen and a half years later.

Regarding the pre-war health-care system, a participant said:

“Before the war we have got an equable right and there were not so many questions, but now at the hospital they ask first; have you insurance and where you’re from”.

One interviewee compared the health-care system in her home city and in her place of residence as follows:

“I was born in another city and I am living in Kljuc, I think if I am going back and asked for help in my hometown, I would get better service than here”

Some of the participants were very disappointed. One of them said: “This is a disaster, this does not exist anywhere else…. there are no words to describe how hard it is in the country’s health-care system…. no one does something to change the situation”.

3.1.2. Insurance system

Health-care insurance for participants in the present study was another difficult problem the participants meet every day. All the participants in the study were unemployed, which complicated the situation much more in terms of health-care insurance. The majority of the participants in this study described that it was hard to get a job in the places where they lived as refugees and that the reason for that was that they had another cities as born place.

One elderly man said:

“I’m unemployed and have no health insurance, I must not be sick because I cannot pay for medical services …. if you do not have insurance and you have no money, you can die.”

One woman said:

“I was born in Kotor Varos and I sought all possible jobs here that I am living. When I was on employment interview, the employers start message is, there is no work for me….. weird, isn’t it? “

3.1.3. Language differences

Even though all the participants in the present study share to the same culture, belief the same religious and living in the same system, the majority of them stated that the language barriers is an obvious problem for them in their daily live in the resettlement place. Differences in dialect and different places the participants were born could mentioned as an additional reason for this.

One participant stated:

“I might talk differently than people who were born in the city where I live, but that’s not the reason to be treated differently.”

Another participant said:

“I was at the doctor clinic with a patient from Banja Luka and there were ten other patients who were born in this city. They went to the doctor before us, despite that many of them come after, and we waited all day…. I do not know why.”

There were more serious expressions, one participant spoke through tears:

“We are from the same country, have the same language and got the same problems, but so many differences in the health care service. I do not understand what’s going on.”

3.2. The health-care system in post-war period

The participants in the present study described the health care system in the post-war period as significantly different from the health care system in the pre-war period. All the beautiful things that the participants claimed to have experienced before the war did not exist anymore. The participants talked about the health system in the post-war period with a lot of sadness, pain, fear, uncertainty, the concern for themselves and their families. Most participants agreed that the situation in the health care system is alarming and that the general situation is very difficult. The majority of them also indicated that the general situation in the country is difficult and it is hard to find a correct solution to all those problems.

3.2.1. Health-care professional’s attitude

Participants in the present study described health-care professionals as extremely arrogant, unprofessional and having a low level of competence. Participants did not know how to behave in health institutions in order to get health-care service.

A participant said the following about the unprofessional attitude:

“I was at surgeon clinic and then I was supposed to go to the lab. The surgeon said I should tell the nurse that laboratory tests have to be done, which I did, and she said:” I know, I have gone to school”.

One patient expressed as follow concerning the level of competence:

“I was at the doctor’s ten months ago. When I saw the doctor, he asked me angrily:”Are you still alive?” I did not know I could replay”?

3.2.2. Corruption in health-care system

Corruption at the state level in all segments of the society was told to exist by all the participants in this study. All of them emphasized that the most difficult situation regarding corruption is in the health care system because it directly has impact on their health, sometimes their lives as well as the lives of their family members. Their words about corruption were accompanied by anger, frustration, disappointment and uncertainty.

A participant said following about the corruption:

“They are all corrupt-from cleaners to directors.”

Another said this:

“If you have money to pay the doctor, then you’ll get better care and medication …. but what about those that have no money, what should they do?”

A participant said the following about discrimination:

“If you do not give money to the doctor, there is no dialogue …. we that are refugees pay much more than those who were born here…..very sad and pathetic.”

One of the participants had a more sensible attitude to corruption:

“I understand that to obtain doctors degree is a long education of 6-10 years but have a small salary, but that’s no reason to ask patients for money …. let them fight for their rights through other institutions.

3.2.3. Future perspectives

The majority of participants finished their descriptions in tears and expressed a certain level of fear and anxiety. None of the participants saw a way out of this difficult situation and saw no glimmer of light in the tunnel. None of them could see bright future of Bosnia and Herzegovina or of the health-care system. Some of them only cried in the last part of the interview.

One older interviewee said:

“It’s hard when you live in another city and so close to your home, it is difficult without the neighbors … it is difficult in general.”

Another described the situation as follows:

“Living in another city is like having a mother and living with a stepmother…. it is hard and I do not know how it will all turn out to be for us …. for the old everything went fine, but what about the youth…. what will they do?”

One participant said angrily:

“We must not be sick …. if you’re sick and you have no money, you do not need to go to hospital…. you can just wait for death.”

4. DISCUSSION

Ongoing global migration and globalization over the world have as a result not only the fact that many societies have become multi ethnic and multicultural, but also that many countries which have become rich with many national immigrants. Generally, immigration is a process which causes an enormous amount of stress for the individuals who are involving since they leave their native cities and seek for new homes in other cities throughout the home country. Once they arrive to other cities of refuge, they need to get used to completely new conditions of living which include cultural, language and social aspect although they still live in their own country. These new circumstance are usually quite different from the ones they were used to in the cities they were born. Apart from these difficulties, there are many other aspects that might be more or less obvious. During the immigration process many changes occur that might affect greatly both mental and physical condition of involved individuals (15, 17, 26). Among many issues, it is the health-care system in the new city that is expectably quite different from the one they were used to in their own cities and in addition, it includes quite different framework of reference and the values of health-care professionals. The life as refugees in their own state was described by the participants in the present study in two ways. One of the ways was that the participants in our study felt very well and without any problems while talking about the time before the war. That time was filled with variety of beauty. It was a wonderful life, the participants were economically independent, travelling with their families, visiting different parts of the former country and the world, and they had one stable life and they felt healthy and happy. However, the picture of life from the postwar period was completely different. Participants described the events in other cities in post-war period as generally difficult. Meeting the health-care professionals in the health care system in Bosnia and Herzegovina was described by the participants in the present study as being difficult and with a lot of problems. The biggest problems were in terms of insurance system, linguistic dialect, health-care professional’s attitude, as well as corruption. The findings in the present study that the participants live in the time eighteen and a half years after the war and still think of and miss the period before the war are very important and interesting. This can depend on many wonderful memories from this period and difficulties to forget them. Our finding is in the line with another study with immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina living in America. Like in the present study, the author showed that the participants voiced a combination of frustration, confusion and anxiety about the American health insurance system. They compared the insurance system in America with the same system in pre-war Bosnia and Herzegovina and found that Americans paid directly for their health insurance (16). One interesting finding in the present study was that participants described language difficulties due to the dialect. This finding was in the same line with two others studies and about use of interpreters for those who did not speak Arabic language. The authors of those studies (27, 28), showed that although the participants spoke the same language, there might have been some differences related to dialects that were not commonly understood as Arabic speaking participants show their social class, country of origin, geographic origin and education through the pronunciation of words. The authors also showed that differences in Arabic dialects were great enough to create major misunderstandings in a health-care encounter, which made it difficult to use a professional interpreter service broadly (27, 28).

When talking about health-care professional’s attitude, as well as corruption, the findings in the present study showed that it was the most difficult problem the participants meet in the health-care system in Bosnia and Herzegovina. All the participants were critical about this issue and found no justification for it. A similar study from Scotland, Sweden and America had to aim to explore the attitudes of nurses and nursing students towards working with older people using MAQ score. Scottish participants had the highest (positive) and Swedish participants the lowest average MAQ score. Most participants gave positive responses, but agreed that negative attitudes towards working with older people infiltrate among peers due to working conditions, poor career prospects and a perceived lack of professional respect (29).

Depressive disorders were the problem for almost half of the participants in the present study. Their previous life experiences, unemployment, difficulties caused by different dialects, missing of neighbors and their home cities might be the reason for this. On the other hand, all participants in the present study were born in Bosnia and Herzegovina, but have a high level of extreme depression. In another study by the first author, the patients who received total hip arthroplasty operation showed a high level of anxiety/depression in the EQ-5D score before and one year after the surgery (30). However, all the patients were international immigrants, which was not the case in the present study. Hopefully, this study provides important new knowledge on issues about the difficulties that refugees meet in their own country every day, and is probably the first study in Bosnia and Herzegovina that deals with those issues.

5. CONCLUSION

The quality of health-care services and patient satisfaction in the health-care system in Bosnia and Herzegovina may depend on several factors. On the one hand, patients who were born in the country of their residence and are forced to live as refugees in their own country, and on the other hand, there are health-care professionals who are dissatisfied with the system and they search for the solution to their problems in their patients. Nowadays, the whole world has become one big company with about 231 million international and 745 million national refugees, health-care professionals are exposed to daily challenges in order to provide adequate support and care to patients. Health-care system must be adjusted to the needs of both the participants born in the cities of their residence as well as those born in other cities and health-care professionals must be aware of the difficulties that the patients have when they live as refugees in their own country. In order to provide health-care on a high level, health-care professionals must meet all the expectations of the patients, and not to expect the patients to fulfil the expectations of the health-care professionals. Different educational activities, such as lectures, seminars and conferences, aimed the health-care at large, are needed to optimize the use of health-care system for participants who are refugees in their own country.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: NONE DECLARED.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNHCR (United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees). Global Refugees trends. Statistics/Statistical Yearbook, September. 2004. Available from http://www.unhcr.org/cgi-bin/texis/vtx/home .

- 2.Lundh C, Ohlsson R. 2nd ed. Stockholm: SNS Publishing; 1999. Från arbetskraftsimport till flyktinginvandring (From import of labour migrants to immigration of refugees) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandbacka C. Helsinki: Acta Philosophica Fennica; 1987. Understanding other Cultures. Studies in the Philosophical Problems of Cross-Cultural Interpretation. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang S. The Third Balkan War: Red Cross Bleeding. Croat Med J. 1993;34:5–20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kravic N, Pajevic I, Hasanovic M. Surviving genocide in Srebrenica during the early childhood and adolescent personality. Croat Med J. 2013;54:55–64. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2013.54.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasanovic M, Haracic E, Ahmetspahic Š, Kurtovic S. Haracic Poverty and Psychological Disturbances of War-Traumatized Adolescents from Rural and Urban Areas in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In: Mallory E, Weinstein, editors. Encyclopedia of Psychology Research. Vol. 2. New York: Nova Publishers; 2011. pp. 863–888. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgetts G, Broers T, Godwin M, Bowering E, Hasanovic M. Post-traumatic Stress disorder among family physicians in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Fam Pract. 2003;20:489–491. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer D, Ward K. “Lost”: Listening to the voices and mental health needs of Forced migrants in London. Med Confl Surviv. 2007;23:198–212. doi: 10.1080/13623690701417345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahomed N N, Barrett J A, Katz J N, Phillips C B, Losina E, Lew RA, Guadagnoli E. Rates and outcomes of primary and revision total hip replacementin the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003;85:27–32. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrahim SA. Racial variations in the utilization of knee and hip joint replacement: an introduction and review of the most recent literature. Curr Orthop Pract. 2010;21:126–131. doi: 10.1097/BCO.0b013e3181d08223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawker GA. The quest for explanations for race/ethnic disparity in rates ofuse of total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1811–1818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suarez-Almazor ME, Souchek J, Kelly PA, O’Malley K, Byrne M, Richardson M, Pak C. Ethnic variation in knee replacement: patient preferences oruninformed disparity? Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1117–1124. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.10.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krupic F, Garellick G, Gordon M, Kärrholm J. Different patient-reported outcomes in immigrants and patients born in Sweden: 18,791 patients with 1 year follow-up in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Registry. Acta Orthop. 2014;85(3):221–228. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.919556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grandahl M, Tydén T, Gottvall M, Westerling R, Oscarsson M. Immigrant women's experiences and views on the prevention of cervical cancer: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2012 Dec 16; doi: 10.1111/hex.12034. doi: 10.1111/hex.12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundquist J. Living conditions and health. A population-based study of labour migrants and Latin American refugees in Sweden and those who were repatriated. Scandinavian J Prim Health Care. 1995;13:128–134. doi: 10.3109/02813439508996749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Searight HR. Bosnian immigrants’ perceptions of the United States health care system: a qualitative interview study. J Immigr Health. 2003;5(2):87–93. doi: 10.1023/a:1022907909721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seffo N, Krupic F, Grbic K, Fatahi N. From Immigrant to Patient: Experiences of Bosnian Immigrants in the Swedish Healthcare System. Materia Sociomed. 2014;26:84–89. doi: 10.5455/msm.2014.26.84-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasanović M, Sinanović O, Pajević I, Avdibegović E, Sutović A. Post-war mental health promotion in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Psychiatr Danub. 2006;18:74–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasanović M, Herenda S. Post traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety among family medicine residents after 1992-95 war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Psychiatr Danub. 2008;20(3):277–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasanović M, Pajević I, Avdibegović E, Kravić N, Moro L, Frančišković T, Gregurek R, Tocilj G. Group analysis training for Bosnia-Herzegovina mental health professionals in the aftermath of the 1992-1995 war. Acta Med Acad. 2012;41:226–227. doi: 10.5644/ama2006-124.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mc Lafferty I. Focus group interviews as a data collecting strategy. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(2):187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kvale S. The qualitative Research Interview. Lund, Sweden (In Swedish): Studentliteratur; 1997. Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. 2nd edition. Sydney: Psychology Foundation; 1995. Manual for the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitive content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measurres to achieve trustworthinnes. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edinburgh: World Medical Association; 2005. The World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Code of Ethics 1964 (Revised) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fatahi N. The impact of the migration on psychosocial wellbeing: A study of Kurdish refugees in resettlement country. J Community Med Health Education. 2014;4:2. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tribe R, Raval H. Hove: Brunner-Routledge; 2003. Working With Interpreters in Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purnell LD, Paulanka BJ. 3rd edition. Philadelphia: FA. Davis; 2008. Transcultural Health Care: A Culturally Competent Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kydd A, Touhy T, Newman D, Fagerberg I, Engström G. Attitudes towards caring for older people in Scotland, Sweden and the United States. Nurs Older People. 2014;26(2):33–40. doi: 10.7748/nop2014.02.26.2.33.e547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krupic F, Eisler T, Garellick G, Kärrholm J. Influence of ethnicity and socioeconomic factors on outcome after total hip replacement. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(1):139–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]