Abstract

The threat of varicella and herpes zoster in immunocompromised individuals necessitates the development of a safe and effective varicella-zoster virus (VZV) vaccine. The immune responses of guinea pigs to the intradermal (i.d.) or subcutaneous (s.c.) administration of a heat-inactivated or live VZV vaccine were investigated. Relative to nonimmunized animals, a single 399-PFU dose of vaccine induced nonsignificant increases in gamma interferon (IFN-γ), granzyme B, and perforin mRNA expression in the splenocytes of all groups, while two i.d. administrations of the inactivated vaccine increased IFN-γ mRNA expression significantly (P < 0.005). A single 1,995-PFU dose significantly increased the expression of IFN-γ mRNA in the groups receiving the vaccine either i.d. (P < 0.005) or s.c. (P < 0.05), that of granzyme B mRNA in the groups immunized i.d. with the inactivated (P < 0.005) or live (P < 0.005) vaccine, and that of perforin mRNA in the animals that received the inactivated vaccine i.d. (P < 0.005). Importantly, increases in the expression of IFN-γ (P = 0.025), granzyme B (P = 0.004), and perforin (P > 0.05) mRNAs were observed in the animals immunized i.d. with 1,995 PFU of inactivated vaccine relative to those immunized s.c. with the same dose. The proportion of animals expressing IFN-γ mRNA mirrored the proportion expressing IFN-γ protein (correlation coefficient of 0.88). VZV glycoprotein-specific and virus-neutralizing antibodies were produced with no significant intergroup differences. A booster i.d. administration of the 399-PFU dose of heat-inactivated vaccine enhanced the antibody responses. These results demonstrate that i.d. administration of an inactivated VZV vaccine can be an efficient mode of immunization against VZV.

INTRODUCTION

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) causes varicella by primary infection and herpes zoster by reactivation of the latent virus in the sensory ganglia of infected individuals. After primary infection, the immune response comprises VZV-specific antibody and T cell-mediated immunity (CMI), which are important for recovery from varicella. T cell responses are necessary to control latent VZV in the sensory ganglia. A lack or a declining level of CMI to VZV has been associated with a higher risk of development of herpes zoster (1).

A varicella vaccine consisting of live, attenuated strain OKA (vOKA) has been developed in Japan and licensed for mass vaccination in Japan, South Korea, the United States, and several European countries or recommended for only selected groups of the population in other countries (2, 3). To prevent herpes zoster, a zoster vaccine containing 14 times as many PFU of vOKA than the varicella vaccine was developed and licensed for the vaccination of immunocompetent subjects older than 60 years in the United States in 2006 (4). Varicella and zoster vaccines are administered by the subcutaneous (s.c.) route. However, vaccination of immunocompromised individuals with live VZV vaccines can be problematic and different strategies for safe immunization need to be explored (5).

Several clinical studies have indicated that the use of a heat-inactivated VZV vaccine is an alternative mode of immunization of immunocompromised individuals. Triple vaccination of bone marrow transplant patients with a heat-inactivated varicella vaccine administered s.c. decreased the severity of herpes zoster (6) and four s.c. doses of a heat-inactivated zoster vaccine proved safe and immunogenic in patients with tumor malignancy, HIV-infected individuals, or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients (7). When healthy elderly subjects were immunized s.c. with a single dose of either live or heat-inactivated varicella vaccine, there were no differences in antibody responses or IFN-γ production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (8). These data indicated that a heat-inactivated VZV vaccine might be useful in preventing herpes zoster. However, protection against herpes zoster following immunization with either a live or heat-inactivated vaccine is not optimal and a more potent antigenic stimulus is needed to improve the efficacy of the vaccine in high-risk patients (9).

The skin is a highly immunogenic organ (10). Noninvasive, needle-free liquid jet injection of liquid or powder into the skin has been used in clinical trials for immunization against viral infections (11–13). The barrier structure and thickness of the stratum corneum, the outermost layer of the skin, are similar in guinea pigs and humans (18.6 and 18.2 μm, respectively) (14), and thus, the i.d. route of immunization and the effectiveness of a potential i.d. delivery device for humans can be tested in guinea pigs. Moreover, the parental OKA strain is attenuated in human and guinea pig fibroblast cells and vOKA is replicated in guinea pig cells (3). The i.d. injection of guinea pigs with VZV resulted in the infection of neurons in the dorsal root ganglia and gut, indicating viral transport and replication (15). Similarities or differences between the immune responses induced by a live or heat-inactivated VZV vaccine can therefore be tested in guinea pigs.

We investigated the VZV-specific immune responses of guinea pigs to the i.d. or s.c. administration of a live or heat-inactivated VZV vaccine. The expression of IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNAs and IFN-γ protein production in the splenocytes of the immunized animals were measured. The antibody responses in the sera were compared by VZV glycoprotein-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (gpELISA) and virus neutralization assay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

All protocols were approved by the Laboratory Animal Care Committee of the NCE. Guinea pigs were immunized with the 1/5 or full human dose of Varilrix VZV vaccine (i.e., 399 or 1,995 PFU, respectively) in live or heat-inactivated form administered i.d. or s.c. To ensure that equivalent amounts of vaccine were administered into the skin by the device, designed at the National Center for Epidemiology (NCE), in the first set of experiments, the VZV DNA contents of skin biopsy specimens obtained at different times after i.d. administration of the vaccine were determined by real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR). In the second series of experiments, guinea pigs were immunized with the 399- or 1,995-PFU dose of the vaccines, in live or heat-inactivated form, administered i.d. or s.c., and for CMI responses, IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNA expression in the VZV-stimulated splenocytes was determined by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR assay (qRT-PCR). IFN-γ protein levels in the supernatants of the splenocytes were measured by ELISA, and the correlation between the expression of IFN-γ mRNA and the production of IFN-γ protein was investigated. VZV-specific antibody production was measured by gpELISA and virus neutralization assay. Nonimmunized animals were used as controls.

Vaccines.

The VZV vaccine (Varilrix, GlaxoSmithKline, Rixensart, Belgium) contains 103.3 PFU/0.5 ml of live attenuated VZV (vOKA) propagated in MRC5 human diploid cells. Varilrix is for s.c. administration only. We prepared the heat-inactivated vaccine by treatment of the live vaccine at 56°C for 30 min. To confirm the loss of infectivity on heat inactivation, MRC5 cells (Medical Research Council, London, United Kingdom) were infected with the heat-inactivated or live vaccine and the expression of VZV antigens was tested by immunofluorescence assay with a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for VZV nucleocapsid (LifeSpan BioSciences Inc., Seattle, WA) and VZV-positive human sera obtained from the Herpes Diagnostics Laboratory of the NCE and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–anti-mouse (Trinity Biotech, Wicklow, Ireland) or –anti-human (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) antibody conjugate, respectively. The cells infected with the heat-inactivated virus were completely negative for VZV antigens, while the cells infected with the live vaccine expressed these antigens abundantly.

Vaccine administration by the i.d. route.

A needle-free liquid jet injection-based device that administers liquid into the skin under pressure was developed at the NCE (NCE device). Hartley guinea pigs 6 to 8 weeks old were used for the experiments (LAB-ÁLLBt, Budapest, Hungary).

qPCR detection of VZV DNA in guinea pig skin biopsy specimens.

Thirteen animals received 0.1 ml of the Varilrix vaccine (399 PFU) by the i.d. route, and 11 animals received the heat-inactivated vaccine similarly. Skin punch biopsy samples (5 mm in diameter) from the site of vaccine administration were obtained from two or three animals/time point immediately after vaccination (day 0) and 2, 4, 7, and 14 days later and processed for DNA extraction and qPCR. Briefly, the skin biopsy specimen was pulverized with liquid nitrogen with a mortar and pestle and 600 μl of RLT-plus buffer was added to this powder. The homogenate was vortexed for 1 min and then centrifuged for 3 min at 12,000 × g. DNA was isolated from the supernatant according to the manufacturer's instructions (Allprep DNA/RNA kit; Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The qPCRs were carried out in a 10-μl final volume with a LightCycler 480 II thermocycler (Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). The PCR mixture contained 2.5 μl of a DNA sample and 7.5 μl of a combination of 0.4 μl (100 μM) each of the forward and reverse primers, 0.2 μl (200 μM) of the probe, 5 μl of PCR master mix, and 1.5 μl of RNase-free distilled water. The PCR conditions were as follows: 95°C hot start for 15 min, followed by 50 amplification cycles of 95°C for 10 s, annealing at 50°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 10 s. The data were analyzed by the LightCycler 480 II system. DNA content was taken as the cycle threshold (CT) value, i.e., the number of PCR cycles at which the amount of amplified target was detected above the threshold value. The VZV primers used amplified open reading frame 29 (early DNA binding protein) of the VZV genome with sense primer 5′-CGT ACA CGT ATT TTC AGT CCT CTT-3′, antisense primer 5′-GGC TTA GAC GTG GAG TTG ACA-3′, and probe 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)–CCC GTG GAG CGC GTC GAA A–6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) (16). The primers and probe for the reference housekeeping RNase P gene (GenBank accession no. XM_005000167.1) were designed at the NCE (sense primer, 5′-GGA TTT AGA CCT AAG AGC G-3′; antisense primer, 5′-GAG CGG CAG TTT CCA CCA TT-3′; probe, FAM-TTC TGA TCT GAA GGC TTT GCG TG-TAMRA). Primer efficiencies and the dynamic range of the target gene assay were determined in triplicate with serial dilutions of DNA isolated from biopsy samples obtained immediately after the vaccination of a guinea pig. ΔCT (CT VZV minus CT RNase P) was calculated for each DNA dilution, and the log DNA dilution was plotted versus ΔCT. The slope of the line was close to zero; hence, the efficiencies of the target and reference genes were similar. The 2−(ΔΔCT) calculation ΔΔCT = (CTTarget − CTRNase P)Time x − (CTTarget − CTRNase P)Time zero was used for relative quantification (17). The mean value of the samples obtained immediately (time zero) after i.d. administration of the vaccine was used as a reference.

Immunization of guinea pigs.

Four to six animals per group were immunized i.d. or s.c. with either the 399-PFU or the 1,995-PFU dose of the live or heat-inactivated vaccine. The animals were sacrificed 4 weeks after vaccine administration, and blood and splenocytes were obtained. Nonimmunized guinea pigs served as controls. Six guinea pigs vaccinated i.d. with the 399-PFU dose of heat-inactivated vaccine received an i.d. booster with the same vaccine preparation 23 weeks later. Blood and splenocytes were obtained 4 weeks after the booster administration.

VZV antigen preparation and stimulation of splenocytes.

The VZV antigen for the stimulation of splenocytes was prepared as described earlier (18), with some modifications. Briefly, guinea pig embryonic fibroblast cells from 28-day-old embryos of Hartley guinea pigs, grown in tissue culture flasks, were infected with the live vaccine and incubated in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) containing 10% heat-inactivated serum obtained from healthy guinea pigs. On day 5 after infection, cells were scraped into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–sucrose–glutamate buffer containing 10% heat-inactivated guinea pig serum. A few drops of this suspension was processed for immunofluorescence testing with VZV-positive human serum to ensure the presence of VZV antigens in the guinea pig cells, and the cells expressed VZV antigens. The remaining suspension was sonicated on ice with a Vibracell 72434 (Bioblock Scientific, Illkirch, France) ultrasonic disintegrator (3 × 15 s) and clarified by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was aliquoted and frozen at −80°C until use. For splenocyte stimulation, immunized and nonimmunized guinea pigs were sacrificed and splenocyte suspensions were prepared. Splenocytes (2 × 106 per 0.6 ml) were stimulated with a VZV antigen preparation at 10 μg/ml protein for 24 h.

Total RNA isolation and RT.

Total RNA was extracted from stimulated splenocytes with the RNeasy Plus minikit and treated with the RNase-Free DNase set to remove genomic DNA contamination according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The total RNA was eluted with 50 μl of RNase-free water, and the mRNA was reverse transcribed with the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA synthesis kit in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The resulting cDNA was stored at −80°C until qRT-PCR assay.

Detection of mRNA expression by qRT-PCR assay.

IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNAs were quantified by qRT-PCR assay. The qRT-PCRs were carried out as described for qPCR but with 2.5 μl of cDNA sample in the reaction mixture at an annealing temperature of 60°C. The primers and probes for IFN-γ were as described earlier (sense primer, 5′-CAT GAA CAC CAT CAA GGA ACA AAT-3′; antisense primer, 5′-TTT GAA TCA GGT TTT TGA AAG CC-3′; probe, FAM-TTC AAA GAC AAC AGC AGC AAC AAG GTG C-TAMRA) (19). The primers and probes for granzyme B (GenBank accession no. XM_003460665.1) and perforin (GenBank accession no. XM_003473749.1) target genes were designed at the NCE (granzyme B sense primer, 5′-TCC AGA GGG AAC ATA CCC AG-3′; antisense primer, 5′-GTA AGA GTT CCT CAC ACT TCTC-3′; probe, FAM-CAC TGC AGG AAG TGG AGA TGA TAGT-TAMRA; perforin sense primer, 5′-CAG CAG AAG AGG CCC AAT GA-3′; antisense primer, 5′-TGG ACA ATG GTC ACC GTC AG-3′; probe, FAM-TGC CAC GGC TCA GCA GTC ATC ACC-TAMRA). The RNase P primers and probe are described for qPCR. The product size was <150 bp for each amplicon. Each measurement was performed in triplicate. Primer efficiencies and the dynamic range of each target gene assay (IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin) were determined in triplicate with serial dilutions of cDNA reverse transcribed from total RNA isolated from splenocytes of a VZV live-vaccine-immunized guinea pig. The ΔCT values of target genes were calculated as described for qPCR. Log cDNA dilution was plotted versus ΔCT. The slopes of the lines were close to zero. Relative quantification was performed by the 2−(ΔΔCT) method [ΔΔCT = (CTTarget − CTRNase P)Immunized animal − (CTTarget − CTRNase P)Nonimmunized animal]; i.e., the relative expression of the target gene was calculated as the ratio of the mean CT value of the target gene (IFN-γ, granzyme B or perforin) to that of the housekeeping gene (RNase P) in each sample in relation to a reference sample (the mean of the samples obtained from nonimmunized animals).

ELISA to test the IFN-γ protein level and its correlation with the expression of IFN-γ mRNA.

Splenocyte supernatants were assayed in duplicate with an ELISA kit (Guinea Interferon γ ELISA kit; BlueGene Biotech, Shanghai, China) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Optical densities (ODs) at 450 nm of samples were read with an ELISA plate reader (PR 3100; Bio-Rad, Budapest, Hungary). The correlation between the expression of IFN-γ mRNA in stimulated splenocytes and the IFN-γ protein level in the supernatant of the splenocyte cultures was determined. A guinea pig was considered IFN-γ mRNA reactive if the mRNA expression level was ≥10-fold higher than that of nonimmunized animals. IFN-γ protein reactivity was considered to exist when the IFN-γ concentration (pg/ml) of the supernatant of splenocyte cultures from immunized animals was higher plus 3 interquartile ranges (IQRs) than that of nonimmunized animals.

VZV-specific antibodies in the sera of immunized animals as determined by VZV gpELISA and virus neutralization assay.

VZV glycoprotein-specific IgG antibodies were determined in duplicate in serial dilutions of the sera of four to six guinea pigs per group with ELISA microplates coated with highly purified VZV glycoproteins (EUROIMMUN anti-VZV glycoprotein ELISA [IgM] kit; EUROIMMUN Ag, Lübeck, Germany), horseradish peroxidase–anti-guinea pig IgG conjugate (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark), and tetramethylbenzidine-H2O2 substrate from the EUROIMMUN ELISA kit. ODs at 450 and 620 nm were measured. The serum titers were determined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution at which the OD value exceeded 0.2 after subtraction of the no-serum blank value. The mean negative test OD plus 3 standard deviations was used to establish a cutoff value by repeated testing of sera from 10 nonimmunized animals. The negative-control sera produced an OD reading of <0.05 in each test.

For the determination of neutralization antibody titers, a plaque reduction neutralization assay was used (20), with some modifications. Briefly, serially diluted guinea pig sera were mixed with an equal volume of vOKA vaccine in the presence of 10% complement and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The test was set up such that 45 to 50 PFU was added per well. The antibody-virus mixture was inoculated onto the monolayers of MRC5 cells grown on eight-well tissue culture plates (Asahi Glass Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The plaques were counted on day 5 with the aid of immunofluorescence with a mouse monoclonal antibody specific for VZV nucleocapsid and an FITC–anti-mouse antibody conjugate as described above for the preparation of heat-inactivated vaccine. The antibody titer was calculated as the reciprocal of the dilution that reduced the number of plaques by 50%. Before the ELISA and neutralization assay, the sera from the immunized animals were absorbed with MRC5 cells to eliminate potential anticellular antibodies.

Statistical analysis.

All statistics were calculated with the Microsoft Excel 2007 software package; differences were determined by the Mann-Whitney test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. Correlation coefficients were determined by the Pearson test.

RESULTS

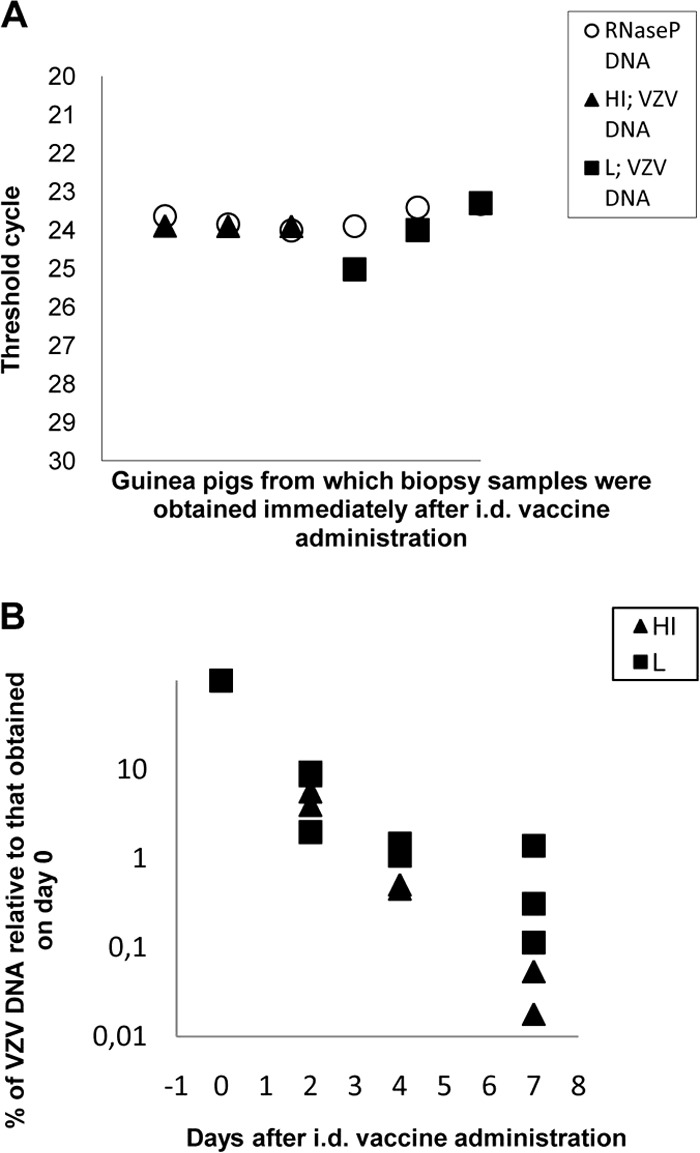

VZV DNA in guinea pig skin biopsy specimens at different times after i.d. vaccine administration.

To test the accuracy of i.d. administration of the VZV vaccine by the NCE device and to determine the duration of VZV DNA detectability in the skin, 399-PFU doses of the live and heat-inactivated forms of the vaccine were administered i.d. and skin biopsy specimens were obtained immediately (day 0) and 2, 4, 7, and 14 days later. The contents of VZV DNA and the housekeeping RNase P DNA in samples obtained immediately after administration of the live (three animals) or heat-inactivated (three animals) vaccine were very similar, with a difference of <2 threshold cycles between the samples (Fig. 1A). In two or three samples per group of animals on the days indicated, the VZV DNA content declined in time after vaccine administration. On days 4 and 7, the DNA content was higher in the biopsy samples obtained from the animals that received the live vaccine than in those from animals that received the heat-inactivated vaccine (P > 0.05) (Fig. 1B). On day 14, the DNA contents were similar and very low in the samples from both groups of guinea pigs (not shown). These results demonstrated that use of the NCE device ensured reliable vaccine administration by the i.d. route and indicated low-level replication of VZV DNA on days 4 to 7 in the skin of the animals receiving the live VZV vaccine.

FIG 1.

VZV DNA in biopsy samples from individual guinea pigs. (A) VZV and RNase P DNA contents of skin biopsy samples obtained immediately (day 0) after administration of the 399-PFU dose of live (L) or heat-inactivated (HI) vaccine. (B) VZV DNA contents of biopsy samples at different times after vaccine administration. Data are expressed as percentages of the values obtained immediately after vaccine administration. The difference between the percentages of VZV DNA contents in biopsy samples from animals receiving HI or L vaccine was not significant at any time point (P > 0.05).

Expression of IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNAs in guinea pig splenocytes after a single administration of a 399-PFU dose of the live or heat-inactivated VZV vaccine and the booster effect of a second 399-PFU dose of the heat-inactivated vaccine given i.d.

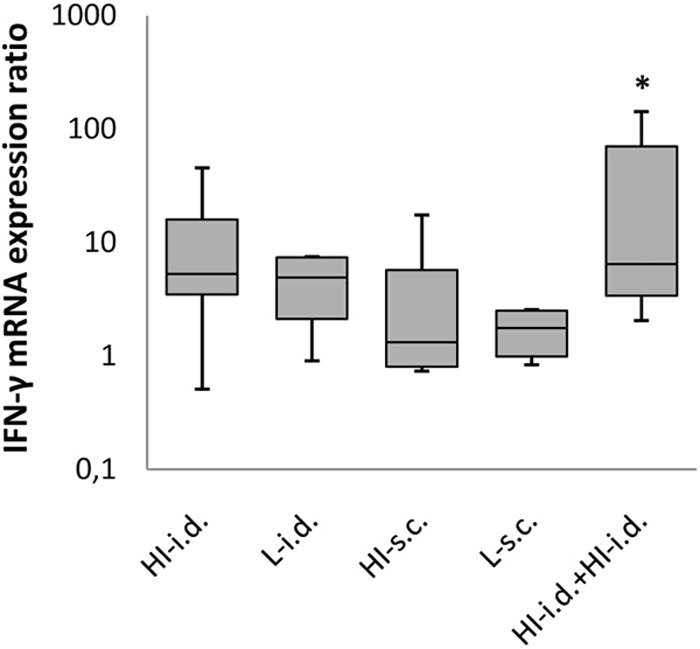

Since the CMI responses have an important role in protection against reactivation of the latent virus in the sensory ganglia, we tested the expression of the IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNAs in splenocytes after a single i.d. or s.c. administration of the live or heat-inactivated vaccine. The results revealed that the differences in IFN-γ mRNA expression between the animals immunized with either form of the vaccine by either administration route and the nonimmunized animals were not significant. To test the effectiveness of a booster administration of the 399-PFU dose of heat-inactivated vaccine given i.d., six guinea pigs were given a second dose of the same vaccine i.d. and a significant increase in IFN-γ mRNA expression was observed in the splenocytes compared with that in the nonimmunized animals (P = 0.004), but the increase over that in animals receiving one dose of the vaccine was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Fig. 2). The granzyme B and perforin mRNA expression was similar in the animals that received one or two doses of the vaccine and did not differ significantly from that in nonimmunized animals (not shown).

FIG 2.

IFN-γ mRNA expression in stimulated splenocytes from guinea pigs immunized with the 399-PFU dose of VZV vaccine administered in different forms and by different routes. The median fold increases (solid lines in boxes) in mRNA expression, the 25-to-75% response ranges (top and bottom lines of boxes), and the minima and maxima (whiskers) are shown. The asterisk indicates that the IFN-γ mRNA expression after a booster 399-PFU dose of heat-inactivated (HI) vaccine administered i.d. was statistically significantly different from that of nonimmunized animals (P = 0.004). L, live.

Expression of IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNAs in guinea pig splenocytes after a single i.d. or s.c. administration of the 1,995-PFU dose of the live or heat-inactivated VZV vaccine.

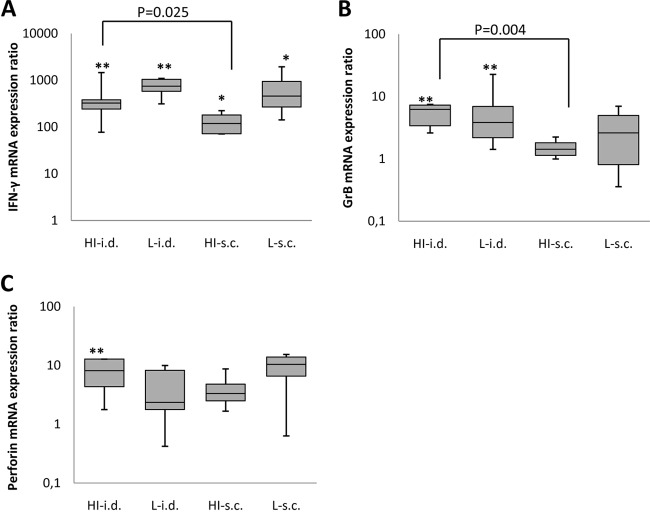

The expression of IFN-γ mRNA was significantly higher in splenocytes obtained from animals immunized with either the heat-inactivated or the live form i.d. (P < 0.005) or s.c. (P < 0.05) than in those from nonimmunized animals. The live vaccine induced a stronger response than the heat-inactivated vaccine by either route of administration, but the difference was not statistically significant. Importantly, the expression of IFN-γ mRNA by splenocytes obtained from animals immunized i.d. with the heat-inactivated form was significantly higher than that by splenocytes from animals immunized with the same vaccine s.c. (P = 0.025) (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNA expression in stimulated splenocytes from guinea pigs immunized with the 1,995-PFU dose of VZV vaccine given in different forms and by different routes. IFN-γ (A), granzyme B (B), and perforin (C) mRNA expression in splenocytes from immunized animals relative to that in splenocytes from nonimmunized animals is shown. HI, heat inactivated; L, live; *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005.

The expression of granzyme B mRNA in the animals immunized i.d. with the live or heat-inactivated vaccine was significantly higher than that in nonimmunized animals (P < 0.005), while the increase in animals that received these vaccines s.c. was not significant. Importantly, the expression of granzyme B mRNA in animals immunized with the heat-inactivated form of the vaccine i.d. was significantly higher than that in animals immunized with the same form of the vaccine s.c. (P = 0.004) (Fig. 3B).

The expression of perforin mRNA was significantly higher only in animals that received the heat-inactivated vaccine i.d. than that in nonimmunized animals (P < 0.005) (Fig. 3C).

IFN-γ protein production of guinea pig splenocytes after a single i.d. or s.c. administration of a 1,995-PFU dose of the heat-inactivated or live vaccine s.c.

mRNA expression does not necessarily indicate protein expression. We therefore used an ELISA to test the IFN-γ protein production of splenocytes from animals immunized with the heat-inactivated form of the vaccine i.d. or s.c. and compared the results with those of splenocytes obtained from guinea pigs immunized with the live vaccine s.c., the currently accepted form and route of VZV vaccination (Table 1). The content of IFN-γ protein (P < 0.05) and the fold increase in the expression of IFN-γ mRNA were significantly higher in animals immunized by the i.d. route (P < 0.005) or by the s.c. route (P < 0.05) than in nonimmunized animals. Whereas the fold increase in IFN-γ mRNA in animals that received the heat-inactivated vaccine by the i.d. route was significantly higher than that in animals that received this vaccine s.c. (P = 0.025) (see also Fig. 3A), the difference between the IFN-γ protein contents in the supernatants was not significant. Nevertheless, the animals classified as mRNA reactive mirrored the animals classified as IFN-γ protein reactive and the correlation coefficient of the median fold increase in mRNA expression and IFN-γ protein production was 0.88.

TABLE 1.

Correlation between IFN-γ mRNA expression and IFN-γ protein production by stimulated splenocytes from guinea pigs vaccinated with the 1,995-PFU dose of heat-inactivated vaccine administered i.d. or s.c. or with the live vaccine given s.c.a

| Vaccine and routeb | IFN-γ protein pg/ml median (range, IQR) | No. of IFN-γ protein-reactive/total no. of animals | IFN-γ mRNA fold increase median (range, IQR) | No. of IFN-γ mRNA-reactive/total no. of animals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HI i.d. | 291 (264–328, 18)c | 5/5 | 326 (77–1,461, 137)d | 6/6 |

| HI s.c. | 273 (209–300, 73)c | 5/5 | 119 (71–223, 109)c,e | 5/5 |

| L s.c. | 353 (273–401, 42)c | 4/4 | 461 (142–1,941, 674)c | 4/4 |

| N | 154 (145–163, 9) | NAf | 1 | NA |

Criteria for animals reactive for IFN-γ mRNA or for IFN-γ protein are described in Materials and Methods.

HI, heat inactivated; L, live; N, nonimmunized animals.

P < 0.05 compared with nonimmunized animals.

P < 0.005 compared with nonimmunized animals.

P < 0.05 compared with i.d. administration.

NA, not applicable.

VZV glycoprotein-specific and virus-neutralizing antibody levels after VZV vaccination by the i.d. or s.c. route with the live or heat-inactivated form.

The antibody production in all groups of guinea pigs immunized with the 399- or 1,995-PFU dose and in the groups immunized with the 399-PFU dose of heat-inactivated vaccine given twice i.d. was tested by a gpELISA (Table 2). The 1,995-PFU dose of vaccine proved to induce similar VZV glycoprotein-specific IgG antibody titers in guinea pigs immunized with the live or heat-inactivated vaccine either i.d. or s.c., with the nonsignificantly highest level in the animals immunized with the live vaccine s.c. The heat-inactivated vaccine induced a stronger antibody response when administered i.d. than when given s.c., but the difference was not significant. The 399-PFU dose of heat-inactivated vaccine administered i.d. induced a significantly lower titer of glycoprotein-specific IgG antibodies than the 1,995-PFU dose given similarly once (P < 0.05). The i.d. booster inoculation with the 399-PFU dose of heat-inactivated vaccine produced an antibody response significantly greater than that of the animals immunized with one dose of the same vaccine (P < 0.005). The neutralization titers showed no intergroup differences in animals immunized with the 1,995- or 399-PFU dose of the vaccines. No neutralization activity was observed in the animals receiving the 399-PFU dose of heat-inactivated vaccine i.d. once, while the animals receiving the same vaccine i.d. two times developed a neutralization titer of 1:32.

TABLE 2.

VZV gpELISA and virus neutralizing-antibody titers in the sera of immunized guinea pigsa

| Dose (PFU), vaccine, and route | Endpoint titer of antibody to VZV glycoproteins | Neutralizing-antibody titer |

|---|---|---|

| 399 | ||

| HI i.d. | 200 | <4 |

| HI s.c. | 168 | <4 |

| L i.d. | 159 | <4 |

| L s.c. | 425 | 4 |

| HI i.d + HI i.d. | 21,544b | 32 |

| 1,995 | ||

| HI i.d. | 131,950c,d | 128 |

| HI s.c. | 83,255 | 64 |

| L i.d. | 100,000 | 80 |

| L s.c. | 263,901 | 138 |

VZV glycoprotein-specific IgG antibody titers are expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum in which the OD exceeded 0.2. Neutralization titers are expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution that reduced the number of plaques by 50%. Geometric mean values are shown.

P < 0.005 compared with HI i.d.

P < 0.05 compared with HI i.d + HI i.d.

P < 0.005 compared with HI i.d.

DISCUSSION

In humans, the i.d. route is routinely used for Mycobacterium bovis BCG and recommended for rabies vaccination in some countries, and influenza vaccines for i.d. administration are commercially available. Clinical trials with various other viral vaccines administered i.d. yielded promising data (11, 12, 21). However, poor immune responses have also been reported after i.d. rather than intramuscular administration of the hepatitis B surface antigen vaccine (22). We are not aware of investigations of immune responses to VZV vaccines delivered i.d.

A VZV-specific skin test representing delayed-type hypersensitivity was introduced earlier for testing of CMI in humans with past VZV infection or in humans and guinea pigs after VZV immunization, and the results were compared with those of other assays of immune responses (23–25). The accumulation of CD4+ T cells and CD4+ regulatory T cells at the site of VZV antigen challenge in the skin has recently been described (26). VZV-specific CMI assays have also determined the IFN-γ protein production of immune cells, i.e., the VZV responder cell frequency by enzyme-linked immunospot assays, flow cytometry (7, 27), or IFN-γ ELISA of supernatants of ex vivo-stimulated lymphocytes (28). The qRT-PCR assay allows highly sensitive testing of the mRNA expression of selected genes of importance in humans (29) and animals (30). Measurements of the expression of the mRNAs for IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin, which are encoded by the important cellular genes controlling CMI, do not appear to have been utilized in evaluations of CMI responses to VZV vaccine candidates administered in various forms and by various routes.

In our study, qRT-PCR proved to be a highly sensitive method for the determination of IFN-γ mRNA expression. Importantly, the i.d. delivery of a 1,995-PFU dose of heat-inactivated VZV vaccine induced a significantly higher level of IFN-γ mRNA in stimulated splenocytes than the same vaccine given s.c. Splenocytes from all animals expressing IFN-γ mRNA produced IFN-γ protein with a correlation coefficient similar to that obtained in subjects with active tuberculosis (31) or animals infected with M. bovis (30).

The available data concerning the role of VZV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) or granzyme B production by immune cells in VZV infections are controversial. NK cells and possibly primed CD8+ cells produced higher levels of granzymes A and B in some children with severe varicella disease than in children with a mild or moderate form of the disease (32). CTL responses were detected in healthy adults immunized with live attenuated varicella vaccine; the CTL recognition of VZV proteins was mediated by CD4+ and CD8+ cells (33).

On the other hand, granzyme B and CD8+ immunohistochemical analysis of tissue sections demonstrated that human trigeminal-ganglion-infiltrating CD8+ T cells expressed granzyme B; these T cells, however, were not reactive to the latency-associated VZV proteins, despite the neuronal expression of these proteins (34). In some studies, CD8+ T cells were either undetected or present at low frequencies following VZV infection or vaccination in healthy subjects, in contrast to the more abundantly and frequently detected VZV-specific CD4+ T cells (1). A VZV glycoprotein E vaccine induced VZV-specific CD4+ T cell and antibody responses, but VZV-specific CD8+ T cell responses were not detected in VZV-primed mice (35).

No data appear to have been reported concerning the production of perforin in the course of varicella, herpes zoster, or immunization with a VZV vaccine. However, perforin mRNAs were detected by RT-PCR in human CD4+ CTLs specific for herpes simplex virus (36).

Our results revealed an increased expression of granzyme B mRNA in immunized guinea pigs, as suggested by earlier studies with humans (32, 33). In addition, we demonstrated for the first time an increased expression of perforin mRNA after immunization with live or heat-inactivated vaccine, indicating the activation of VZV-specific CTLs. Interestingly, the expression of IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNAs was not significantly higher in splenocytes obtained from live-virus-immunized animals than in those immunized with heat-inactivated vaccine by the same route. VZV peptides from the heat-inactivated vaccine were probably phagocytosed by antigen-presenting cells in the guinea pig skin and cross-presented to T lymphocytes in the lymph nodes, resulting in the activation of lymphocytes to express IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNAs.

Since outbred Hartley guinea pigs were used in the immunization studies, the CMI responses of some of the animals may have been weak because of the inability of certain major histocompatibility complex (MHC) types of antigen-presenting cells to recognize the VZV stimulus composition and to activate CD8+ lymphocytes. In some cases, no significant difference was observed because of the broad range of cellular immune responses in a given group of animals, perhaps owing to their outbred nature. MHC restriction of T cell responses to VZV in guinea pigs was reported earlier (37). Nevertheless, VZV vaccination is destined for the outbred human population and similar experiments with inbred animal strains would therefore not be helpful.

VZV-specific antibodies have negligible roles in protection against reactivation of the latent virus in the ganglia and the development of zoster. However, VZV-specific antibody production seems important in protection against infection. Maternal antibodies and the passive transfer of VZV-specific antibodies, for instance, can prevent or mitigate the development or severity of varicella after exposure to VZV (38, 39). Thus, the production of a high antibody level by VZV vaccination is desirable in either healthy or immunocompromised individuals. The VZV gpELISA method seems to perform comparably to the virus neutralization assay (40), and the presence of neutralizing antibodies is associated with a positive fluorescent antibody to membrane antigen test result, which has been shown to correlate with protection against clinical varicella (41). We have demonstrated that VZV glycoprotein-specific antibodies are produced in guinea pigs following i.d. or s.c. administration of a 399- or 1,995-PFU dose of heat-inactivated vaccine, the 1,995-PFU dose being significantly more effective (P < 0,005). The antibody level was significantly increased after an i.d. booster inoculation with the 399-PFU dose of heat-inactivated vaccine (P < 0,005). The results showed a concordance between the titers in the gpELISA and the neutralization assay, as was observed previously (40). The mechanism by which the i.d. administration of the heat-inactivated vaccine at a dose of 1,995 PFU induces a significantly higher level of CMI but nonsignificantly higher titers of antibodies than the same vaccine given s.c. is not clear.

A heat-inactivated vaccine administered i.d. might be efficient and safe in immunocompromised children and adults. This mode of VZV vaccination may also be relevant in the case of elderly immunocompetent individuals, who currently receive an expensive vaccine that contains a large dose of live virus. The boost of immunity in the elderly to prevent zoster by the i.d. route with a heat-inactivated vaccine might be preferable because it uses less virus and gives stronger cellular responses.

Our study has limitations. (i) The expression of IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNAs may follow different kinetics after immunization or after the VZV-specific stimulation of splenocytes, and the expression level may even differ in different tissues of the immune system. Marked diversity has been reported in the perforin, granzyme B, and IFN-γ mRNA expression profiles of activated CD8 T cells from influenza virus-infected mice, with different frequencies in CD8+ populations obtained from the lungs, lymph nodes, and spleen (42). We determined mRNA expression at one time point after immunization and harvested splenocytes at one time point after stimulation to determine IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNA expression. Thus, it is possible that the conditions in our experiments were not optimal for each mRNA tested. Nevertheless, we could determine the expression of the mRNAs of these immune effector molecules in guinea pigs immunized with VZV vaccines, including the heat-inactivated vaccine given i.d. (ii) We did not test the kinetics of IFN-γ mRNA and protein expression after the in vitro stimulation of splenocytes with a VZV antigen preparation. A time difference in IFN-γ mRNA expression and IFN-γ protein synthesis has been reported after in vitro stimulation of human blood samples with Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen (31). Further studies are needed to determine the kinetics, levels, and correlations of the expression of mRNAs and proteins of cellular genes involved in the CMI of VZV-immunized individuals. However, the physiological significance of small mRNA or protein level changes is not clear. (iii) We did not carry out intracellular cytokine staining assays to immunophenotype the IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin responder cells. CD4+ proliferative responses are believed to correlate with protection against zoster (43), but CD4+, CD8+, and NK cells may be involved differentially in the production of IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin in individuals immunized i.d. or. s.c. with the live or heat-inactivated vaccine.

In conclusion, our data show that (i) the guinea pig is a suitable species in which to test the i.d. route of immunization; (ii) IFN-γ, granzyme B, and perforin mRNA expression is a highly sensitive measure of VZV-specific CMI; (iii) a heat-inactivated VZV vaccine administered i.d. can induce a higher level of cellular anti-VZV responses in guinea pigs than the same vaccine given s.c.; and (iv) the VZV glycoprotein-specific IgG antibody responses and the virus-neutralizing activity of the sera are similar in animals immunized i.d. or s.c. with live or heat-inactivated vaccine. The findings following the use of a heat-inactivated VZV vaccine administered i.d. warrant further investigation. The optimal dose of the vaccine should be determined. Information on the duration of the immune response to a single or booster i.d. or s.c. heat-inactivated VZV vaccine administration would be important. Moreover, a favorable effect of adjuvants is to be expected and should be explored.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the FastVac consortium funded by the Health Programme of the European Union and the participating member states for their support.

We thank Elisabeth Barcsay and the Herpes Diagnostics Laboratory, NCE, for providing the VZV-specific human sera. We acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Ilona Kormendi, Zsolt Czira, Gabor Nemeth, Gyula Csabai, and the staff of the Animal Facility at the NCE.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weinberg A, Levin MJ. 2010. VZV T-cell mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 342:341–357. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi M, Otsuka T, Okuno Y, Asano Y, Yazaki T. 1974. Live vaccine used to prevent the spread of varicella in children in hospital. Lancet 304:1288–1290. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(74)90144-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvin AM. 2001. Varicella vaccine: genesis, efficacy, and attenuation. Virology 284:153–158. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.0918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitka M. 2006. FDA approves shingles vaccine: herpes zoster vaccine targets older adults. JAMA 296:157–158. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen JI. 2008. Strategies for zoster vaccination in immunocompromised patients. J Infect Dis 197:S237–S241. doi: 10.1086/522129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redman RL, Nader S, Zerboni L, Liu C, Wong RM, Brown BW, Arvin AM. 1997. Early reconstitution of immunity and decreased severity of herpes zoster in bone marrow transplant recipients immunized with inactivated varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis 176:578–585. doi: 10.1086/514077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mullane KM, Winston DJ, Wertheim MS, betts RF, Poretz DM, Camacho LH, Pergam SA, Mullane MR, Stek JE, Sterling TM, Zhao Y, Manoff SB, Annunziato PW. 2013. Safety and immunogenicity of heat-treated zoster vaccine (ZVHT) in immunocompromised adults. J Infect Dis 208:1375–1385. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine MJ, Ellison MC, Zerbe GO, Barber D, Chan C, Stinson D, Jones M, Hayward AR. 2000. Comparison of a live attenuated and an inactivated varicella vaccine to boost the varicella-specific immune response in seropositive people 55 years of age and older. Vaccine 18:2915–2920. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00552-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doerr HW. 2013. Progress in VZV vaccination? Some concerns. Med Microbiol Immunol 202:257–258. doi: 10.1007/s00430-013-0298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Romani N, Thurnher M, Idoyaga J, Steinman RM, Flacher V. 2010. Targeting of antigens to skin dendritic cells: possibilities to enhance vaccine efficacy. Immunol Cell Biol 88:424–430. doi: 10.1038/icb.2010.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson EA, Lam HS, Choi KC, Ho WC, Fung LW, Cheng FW, Sung RY, Royals M, Chan PK. 2013. A pilot randomized study to assess immunogenicity, reactogenicity, safety and tolerability of two human papillomavirus vaccines administered intramuscularly and intradermally to females aged 18–26 years. Vaccine 31:3452–3460. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soonawala D, Verdijk P, Wijmenga-Monsuur AJ, Boog CJ, Koedam P, Visser LG, Rots NY. 2013. Intradermal fractional booster dose of inactivated poliomyelitis vaccine with a jet injector in healthy adults. Vaccine 31:3688–3694. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAllister L, Anderson J, Werth K, Cho I, Copeland K, Le Cam Bouveret N, Plant D, Mendelman PM, Cobb DK. 2014. Needle-free jet injection for administration of influenza vaccine: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 384:674–681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60524-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnusson BM, Walters KA, Roberts MS. 2001. Veterinary drug delivery: potential for skin penetration enhancement. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 50:205–227. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(01)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JJ, Gershon AA, Li Z, Cowles RA, Gershon MD. 2011. Varicella zoster virus (VZV) infects and establishes latency in enteric neurons. J Neurovirol 17:578–589. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0070-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pevenstein SR, Williams RK, McChesney D, Mont EK, Smialek JE, Straus SE. 1999. Quantitation of latent varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus genomes in human trigeminal ganglia. J Virol 73:10514–10518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-delta delta CT method. Methods 25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harper DR, Mathieu N, Mullarkey J. 1998. High-titre, cryostable cell-free varicella zoster virus. Arch Virol 143:1163–1171. doi: 10.1007/s007050050364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawahara M, Nakasone T, Honda M. 2002. Dynamics of gamma interferon, interleukin-12 (IL-12), IL-10, and transforming growth factor β mRNA expression in primary Mycobacterium bovis BCG infection in guinea pigs measured by a real-time fluorogenic reverse transcription-PCR assay. Infect Immun 70:6614–6620. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6614-6620.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keller PM, Neff BJ, Ellis RW. 1984. Three major glycoprotein genes of varicella-zoster virus whose products have neutralization epitopes. J Virol 52:293–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leonardi S, Pratico AD, Lionetti E, Spina M, Vitaliti G, La Rosa M. 2012. Intramuscular vs intradermal route for hepatitis B booster vaccine in celiac children. World J Gastroenterol 18:5729–5733. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gomber S, Sharma R, Ramachandran VG. 2004. Immunogenicity of low dose intradermal hepatitis B vaccine and its comparison with standard dose intramuscular vaccination. Indian Pediatr 41:922–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamiya H, Ihara T, Hattori A, Iwasa T, Sakurai M, Izawa T, Yamada A, Takahashi M. 1977. Diagnostic skin test reactions with varicella virus antigen and clinical application of the test. J Infect Dis 136:784–788. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.6.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takahashi M, Okada S, Miyagawa H, Amo K, Yoshikawa K, Asada H, Kamiya H, Torigoe S, Asano Y, Ozaki T, Terada K, Muraki R, Higa K, Iwasaki H, Akiyama M, Takamizawa A, Shiraki K, Yanagi K, Yamanishi K. 2003. Enhancement of immunity against VZV by giving live varicella vaccine to the elderly assessed by VZV skin test and IAHA, gpELISA antibody assay. Vaccine 21:3845–3853. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shiraki K, Yamanishi K, Takahashi M, Dohi Y. 1984. Delayed-type hypersensitivity and in vitro lymphocyte response in guinea pigs immunized with a live varicella vaccine. Biken J 27:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Sandhu D, Sobande TO, Agius E, Lacy KE, Riddell N, Montez S, Dintwe OB, Scriba TJ, Breuer J, Nikolich-Zuglich J, Ogg G, Rustin MH, Akbar AN. 2013. Varicella zoster specific CD4+Fox3+ T cells accumulate after cutaneous antigen challenge in humans. J Immunol 190:977–986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svahn A, Linde A, Thorstensson R, Karlén K, Andersson L, Gaines H. 2003. Development and evaluation of a flow-cytometric assay of specific cell-mediated immune response in activated whole blood for the detection of cell-mediated immunity against varicella-zoster virus. J Immunol Methods 277:17–25. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1759(03)00111-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otani N, Yamanishi K, Sakaguchi Y, Imai Y, Shima M, Okuno T. 2012. Varicella-zoster virus-specific cell-mediated immunity in subjects with herpes zoster. J Immunol Methods 377:53–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nolan T, Hands RE, Bustin SA. 2006. Quantification of mRNA using real-time RT-PCR. Nat Protoc 1:1559–1582. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrington NP, Surujballli OP, Waters WR, Prescott JF. 2007. Development and evaluation of a real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for quantification of gamma interferon mRNA to diagnose tuberculosis in multiple animal species. Clin Vaccine Immunol 14:1563–1571. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00263-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S, Kim YK, Lee H, Cho JE, Kim HY, Uh Y, Kim YM, Kim H, Cho SN, Jeon BY, Lee H. 2013. Interferon gamma mRNA quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis: a novel interferon gamma release assay. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 75:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vossen MT, Biezeveld MH, de Jong MD, Gent MR, Baars PA, von Rosenstiel IA, van Lier RA, Kuijpers TW. 2005. Absence of circulating natural killer and primed CD8+ cells in life-threatening varicella. J Infect Dis 191:198–206. doi: 10.1086/426866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharp M, Terada K, Wilson A, Nader S, Kinchington PE, Ruyechan WT, Hay J, Arvin AM. 1992. Kinetics and viral protein specificity of the cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in healthy adults immunized with live attenuated varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis 165:852–858. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.5.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verjans GM, Hintzen RQ, van Dun JM, Poot A, Milikan JC, Laman JD, Langerak AW, Kinchington PR, Osterhouse AD. 2007. Selective retention of herpes simplex virus-specific T cells in latently infected human trigeminal ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:3496–3501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610847104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dendouga N, Fochesato M, Lockman L, Mossman S, Glannini SL. 2012. Cell-mediated immune responses to a varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein E vaccine using both a TLR agonist and QS21 in mice. Vaccine 30:3126–3135. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yasukawa M, Ohminami H, Yakushijin Y, Arai J, Hasegawa A, Ishida Y, Fujita S. 1999. Fas-independent cytotoxicity mediated by human CD4+ CTL directed against herpes simplex virus-infected cells. J Immunol 162:6100–6106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayward AR, Burger R, Scheper R, Arvin AM. 1991. Major histocompatibility complex restriction of T-cell responses to varicella-zoster virus in guinea pigs. J Virol 65:1491–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinquier D, Lecuyer A, Levy C, Gagneur A, Pradat P, Soubeyrand B, Grimprel E, Pediatricians Working Group. 2011. Inverse correlation between varicella severity and level of anti-varicella zoster virus maternal antibodies in infants below one year of age. Hum Vaccin 7:534–538. doi: 10.4161/hv.7.5.14820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koren G, Money D, Boucher M, Aoki F, Petric M, Innocencion G, Wolosk M, Remple V, Pelland F, Geist R, Ho T, Bar-Oz B, Loebstein R. 2002. Serum concentrations, efficacy, and safety of a new, intravenously administered varicella zoster immune globulin in pregnant women. J Clin Pharmacol 42:267–274. doi: 10.1177/00912700222011283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krah DL, Cho I, Schofield T. 1997. Comparison of gpELISA and neutralizing antibody responses to OKA/Merck live varicella vaccine (Varivax) in children and adults. Vaccine 15:61–64. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(96)00107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Breuer J, Schmid DS, Gerson AA. 2008. Use and limitation of varicella-zoster virus-specific serological testing to evaluate breakthrough disease in vaccines and to screen for susceptibility to varicella. J Infect Dis 197:S147–151. doi: 10.1086/529448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson BJ, Costelloe EO, Fitzpatrick DR, Haanen JB, Schumacher TN, Brown LE, Kelso A. 2003. Single-cell perforin and granzyme expression reveals the anatomical localization of effector CD8+ T cells in influenza virus-infected mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:2657–2662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538056100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plotkin SA. 2010. Correlates of protection induced by vaccination. Clin Vaccine Immunol 17:1055–1065. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00131-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]