Abstract

Aim

MiR-375 has been implicated in insulin secretion and exocytosis through incompletely understood mechanisms. Here we aimed to investigate the role of miR-375 in the regulation of voltage-gated Na+ channel properties and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in insulin-secreting cells.

Methods

MiR-375 was overexpressed using double-stranded mature miR-375 in INS-1 832/13 cells (OE375) or downregulated using locked nucleic acid (LNA)-based anti-miR against miR-375 (LNA375). Insulin secretion was determined using RIA. Exocytosis and ion channel properties were measured using the patch-clamp technique in INS-1 832/13 cells and beta-cells from miR-375KO mice. Gene expression was analysed by RT-qPCR, and protein levels were determined by Western blot.

Results

Voltage-gated Na+ channels were found to be regulated by miR-375. In INS-1 832/13 cells, steady-state inactivation of the voltage-gated Na+ channels was shifted by approx. 6 mV to a more negative membrane potential upon down-regulation of miR-375. In the miR-375 KO mouse, voltage-gated Na+ channel inactivation was instead shifted by approx. 14 mV to a more positive membrane potential. Potential targets differed among species and expression of suggested targets Scn3a and Scn3b in INS-1 832/13 cells was only slightly moderated by miR-375. Modulation of miR-375 levels in INS-1-832/13 cells did not significantly affect insulin release. However, Ca2+ dependent exocytosis was significantly reduced in OE375 cells.

Conclusion

We conclude that voltage-gated Na+ channels are regulated by miR-375 in insulin-secreting cells, and validate that the exocytotic machinery is controlled by miR-375 also in INS-1 832/13 cells. Altogether we suggest miR-375 to be involved in a complex multifaceted network controlling insulin secretion and its different components.

Keywords: exocytosis, insulin secretion, microRNA, patch-clamp, Scn3a, voltage-dependent channels

Pancreatic β-cells are electrically active, and it is well-established that insulin release is dependent on action potentials initiated by the influx of glucose through low-affinity glucose transporters in the β-cell membrane. Glucose metabolism leads to an increase in intracellular ATP. The resulting increase in the ATP/ADP ratio causes the closure of ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP-channels). This leads to depolarization of the cell membrane, which in turn activates voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. The resulting intracellular increase in Ca2+ triggers the exocytotic release of insulin-containing vesicles (reviewed in Eliasson et al. 2008, MacDonald 2011, Rorsman & Braun 2013).

Insulin secretion is tightly regulated by several mechanisms including that of microRNAs (miRNAs). MicroRNAs are short (19–25 nt) non-coding RNA molecules, which negatively regulate specific target mRNAs by controlling their stability and/or translation (Winter et al. 2009). In β-cells, it has been shown that processes such as insulin release and cell proliferation are regulated by miRNAs (Kolfschoten et al. 2009, Eliasson & Esguerra 2014). One of the better characterized miRNAs in pancreatic β-cells is miR-375. This miRNA is one of the most abundant miRNAs in primary β-cells and was first discovered as a negative regulator of insulin secretion (Poy et al. 2004). Later, miR-375 was shown to play a role in islet development (Kloosterman et al. 2007) and in maintenance of normal β-cell mass (Poy et al. 2009).

Voltage-gated Na+ channels are required for the initiation of action potentials in neurones and muscle cells, but the role of these channels in pancreatic β-cells is more elusive. In human β-cells, it has been shown that voltage-gated Na+ channels are active at physiologically relevant membrane potentials. Blockage of the channels using the specific voltage-gated Na+ channel inhibitor tetrodotoxin (TTX) reduces the glucose-stimulated insulin secretion markedly (Braun et al. 2008). However, in rodents, the situation is not as clear. Na+ channels in mouse and rat β-cells are half maximally inactivated at membrane potentials of −70 mV or below (Hiriart & Matteson 1988, Plant 1988) indicating that in these cells Na+ channels are not critical to the generation of action potentials. Nonetheless, there are reports stating that treatment with TTX reduces glucose-induced insulin secretion in rat (Hiriart & Matteson 1988, Vidaltamayo et al. 2002).

Voltage-gated Na+ channels consist of a pore-forming α-subunit and one or more β-subunits which modulate channel properties and interact with other proteins (Catterall et al. 2005). It has been shown that knocking out the α-subunit Scn3a (part of the Na+ channel subtype Nav 1.3), or the regulatory subunit Scn1b (part of Nav 1.7) reduces glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mice (Ernst et al. 2009, Zhang et al. 2014). This raises the question whether modulation of the expression of the different subunits of the voltage-gated Na+ channels could have an impact on insulin secretion. Here we have investigated the effects of miR-375 on voltage-gated Na+ channel inactivation properties in rat insulinoma INS-1 832/13 cells and in primary mouse β-cells. In addition, voltage-dependent channel activation, exocytosis and insulin secretion were measured in the cell line after modulation of miR-375 levels.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless otherwise indicated.

Cell culture

INS-1 832/13 pancreatic β-cell line derived from rat insulinoma (kindly provided by Dr. C. Newgaard, Duke university, Durban, USA) was maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 11.1 mm d-glucose (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA), supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat inactivated foetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU mL−1 of penicillin (HyClone), 100 μg mL−1 of streptomycin (HyClone), 10 mm HEPES (HyClone) and 2% (v/v) INS-1 supplement. INS-1 supplement consists of 2 mm l-glutamine (HyClone), 1 mm sodium pyruvate (HyClone) and 50 μm 2-mercaptoethanol. MIN-6 pancreatic β-cell line derived from mouse insulinoma (kindly provided by Dr. Miyazaki, Osaka university, Osaka, Japan) was maintained in DMEM (HyClone) containing 25 mm d-glucose, supplemented with 15% (v/v) heat inactivated FBS, 100 IU mL−1 of penicillin (HyClone), 100 μg mL−1 of streptomycin (HyClone) and 70 μm 2-mercaptoethanol. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Primary mouse β-cells

Islets were isolated from pancreas of 375KO (microRNA-375 knockout) and wild-type male mice at 10 weeks of age by collagenase digestion as previously described (Olofsson et al. 2002). The experimental procedure has been approved by the local ethics committee in Oxford. To obtain single cells, islets were dissociated in Ca2+-free buffer. The dispersed cell suspension was plated on 35-mm plastic Petri dishes and maintained in tissue culture in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10 mm glucose, 5% (v/v) FBS, 100 IU mL−1 of penicillin and 100 μg mL−1 of streptomycin. After patch-clamp experiments, β-cell identity was confirmed by immunocytochemistry.

Transfection

One day prior to transfection approx. 400 000 cells per well were seeded in a 24-well plate in antibiotic-free RPMI 1640. Transfection was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol using Oligofectamine™ Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 50 nm oligonucleotide concentration. Oligonucleotide sequence 5′-TCACGCGAGCCGAACGAACAAA-3′ complementary to the rat miRNA miR-375 contains locked nucleic acid (LNA)-modified bases and was used to downregulate miR-375. As negative control, a similarly LNA-modified scrambled oligonucleotide sequence 5′GTGTAACACGTCTATACGCCCA-3′, without known complementary sequence in the rat genome was used (Exiqon, Vedbaek, Denmark). For transient overexpression, chemically modified double-stranded mature microRNA miR-375 was used, called Pre-miR™ miRNA Precursor (PM10327; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). As negative control, Pre-miR™ miRNA Precursor Negative Control #1 (AM17110; Life Technologies) was used. Transfection was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol using lipofectamine® RNAiMAX Reagent (Invitrogen) at 50 nm oligonucleotide concentration. Cells were transfected 48–72 h prior to experiments.

Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

For insulin secretion, cells were plated in triplicate for each condition. At approx. 100% confluency INS-1 832/13 cells were gently washed with freshly made Secretion Assay Buffer (SAB) pH 7.2, with 2.8 mm glucose (SAB: 114 mm NaCl, 4.7 mm KCl, 1.2 mm KH2PO4, 1.16 mm MgSO4, 20 mm HEPES, 25.5 mm NaHCO3, 2.5 mm CaCl2 and 0.2% BSA). The cells were then pre-incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in fresh SAB supplemented with 2.8 mm glucose and then stimulated for 1 h in 1 mL SAB (containing 2.8 or 16.7 mm glucose as marked in the figures) at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Five hundred microlitre of SAB was collected from each well. Insulin levels were measured according to the manufacturer using Coat-a-Count RIA (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA). Insulin secretion measurements were normalized to total protein from each well.

Protein extraction

INS-1 832/13 cells in 24 well plates were washed in ice-cold PBS and incubated on ice for 15 min in RIPA buffer (Radio Immuno Precipitation Assay; 150 nm NaCl, 1% TritonX-100, 0.1% SDS, 50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8 and EDTA-free protease inhibitor; Roche, Branchburg, NJ, USA). The cells were then loosened by pipetting, transferred to pre-cooled tubes and centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min at 14 000 g. The supernatant was then transferred to new tubes and stored at −20 °C. Analysis of protein content in cell homogenates was made with BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and analysed on the BioRad Model 6870 Microplate Reader (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). The insulin content in the samples was determined using Coat-a-Count RIA (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA).

RNA extraction, RT-PCR and qPCR

Prior to RNA extraction, the cells were washed in ice-cold PBS, lysed in Qiazol (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), loosened by pipetting and transferred to microfuge tubes. The cells were homogenized by vortexing for 1 min and stored at −20 °C until RNA extraction. Total RNA extraction was performed according to miRNeasy®Mini Kit protocol (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). RNA concentration was measured using NanoDrop (ND-1000 Spectrophotometer, Nanodrop technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA), and the integrity was validated using the BioRad Experion™ RNA High Sens kit loaded onto Biorad Experion™ High Sens RNA Chips (#700-71612 and #7007106, respectively; BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA).

RT-PCR of total RNA was performed on the PTC-200 Peltier Thermal Cycler according to the protocol of High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using Random Primers. RT-PCR for miRNA was performed according to protocol of TaqMan®MiRNA Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Life Technologies) using pooled stem-loop primers from TaqMan®MiRNA Assays at 0.3 μL each per 15 μL reaction volume; miR375 (#RT_000564), U6 (#RT_001973) and U87 (#RT_001712).

qPCR was performed on 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) or ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) according to the TaqMan®Universal PCR Master Mix I protocol (Applied Biosystems manufactured by Roche) adding primers from TaqMan®Gene Expression Assays; Scn2b (Rn00563554_m1), Scn3a (Rn01485334_m1), Scn3b (Rn00594710_m1), Scn4b (Rn01418017_m1), Mtpn (Rn02347820_m1), Cav1 (Rn00755834_m1), Aifm1 (Rn00442540_m1), Gphn (Rn00575867_m1) and Cadm1 (Rn00457556_m1). The endogenous control assays used for the mRNAs were Hprt (Rn_01527840) and Ppia (Rn_ 00690933). Stem-loop RT-qPCR was performed according to the TaqMan®Universal PCR Master Mix II No AmpErase®UNG protocol (Applied Biosystems manufactured by Roche) using primers from TaqMan®MiRNA Assays miR-375 (#TM_ 000564) and the small RNA endogenous controls U6 (#TM_004394) and U87 (#TM_001712). In Figure 1a, all samples were run in the same plate to facilitate comparison. Threshold levels of all Ct values were automatically set, and the gene expressions were normalized using the geometric means of two endogenous controls. Relative expressions were calculated using the ΔΔCt method.

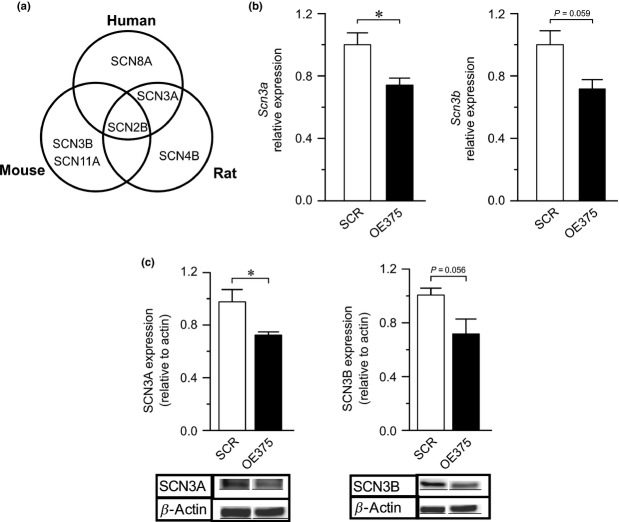

Figure 1.

Analysis of miR-375 expression levels in INS-1 832/13 and MIN-6 cells. (a) MiR-375 levels in INS-1 832/13 and MIN-6 cells displayed relative to levels in INS-1 832/13 cells. (b) Effect of down-regulation of miR-375 using locked nucleic acid (LNA) (LNA375; black bar) and (c) overexpression of miR-375 using chemically modified double-stranded mature miR-375 (OE375; black bar). In both (b) and (c), miR-375 levels in INS-1 832/13 cells after treatment with respective oligonucleotide are measured and then normalized to appropriate scramble controls (SCR; white bars). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three biological experiments, with three technical replicates in each experiment. **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Western blot analysis

Protein was extracted, and protein content was measured approx. 72 h after transfection as described above. Protein samples were separated on 4–15% precast gradient polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The separated proteins were then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% milk and 1% BSA in a buffer consisting of 20 mm Tris, 150 mm NaCl and 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (pH 7.5) for 60 min (4 °C). Proteins were probed with antibodies for SCN3A (1 : 500; #ASC-004; Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) (1 : 1000; #ARP37699_P050; Aviva Systems Biology, Beijing, China) and Beta-actin (1 : 1000; #A5441; Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-rabbit/anti-mouse secondary antibody (1 : 10 000; #7074S; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) and anti-mouse immunoglobulins/HRP antibody (1 : 1000; #P0448; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark).

Bands were visualized using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and AlphaImager (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA, USA). Quantification was made using FluorChem SP software (ProteinSimple).

Electrophysiology

Patch pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries, coated with Sylgard (Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) or with sticky wax (Kemdent, Wiltshire, UK) and fire polished. The pipette resistance was 3–6 MΩ when the pipettes were filled with the intracellular solutions specified below. Experiments were conducted on primary mouse β-cells from 375KO and WT animals and on single INS-1 832/13 cells following transfection of LNA375 (50 nm), OE375 (50 nm) or SCR (control; 50 nm; Exiqon). To be able to visualize transfected cells, we used FAM labelled LNA375 and SCR. Recordings on OE375 cells were performed without visualization of transfected cells. For the latter experiments, transfection efficiency was determined by qPCR. Experiments were performed using the standard whole-cell configuration, applying the first depolarization ≥1 min after establishment of the whole-cell configuration. Changes in membrane capacitance and whole-cell currents were recorded using an EPC-9 or EPC-10 patch-clamp amplifier and the software Pulse (version 8-31; Heka Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany) or Patchmaster (version 2-73; Heka Elektronik). Changes in cell capacitance were measured using the software-based lock-in application that adds sine waves with a frequency of 500 Hz to the holding potential of the amplifier. The standard extracellular solution consisted of (in mm) 118 NaCl, 20 tetraethyl-ammonium chloride (TEA-Cl; to block voltage-gated K+ currents), 5.6 KCl, 2.6 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 5 glucose and 5 HEPES (pH 7.4 using NaOH). The pipette solutions contained (in mm) 125 Cs-Glut, 10 NaCl, 10 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.05 EGTA, 3 Mg-ATP, 5 HEPES (pH 7.15 using CsOH) and 0.1 cAMP.

Data analysis

Data are represented as means ± SEM. Differences between groups were tested using two-tailed Student's t-test.

Results

Expression of miR-375 in INS-1 832/13 and MIN-6 cells

We determined the endogenous expression of miR-375 in INS-1 832/13 cells by qPCR and found it to be highly expressed, albeit approximately twofold lower than those expressed in MIN-6 cells (Fig. 1a).

To investigate the role of miR-375 in INS-1 832/13 cells, we performed either down-regulation or overexpression assays via transfection with LNA anti-miR against miR-375 or with chemically modified double-stranded mature miR-375 sequences, respectively. From now on these transfected cells are referred to as LNA375 and OE375 (overexpressed 375) cells, respectively. Controls are referred to as SCR (scrambled). We verified by qPCR that miR-375 transfection with 50 nm of target specific LNA (LNA375) almost completely suppressed the expression of miR-375 compared to the scrambled control (Fig. 1b). Likewise addition of 50 nm miR-375 double-stranded mimic (OE375) increased miR-375 expression approx. 20-fold (Fig. 1c).

Effect of miR-375 on insulin secretion and exocytosis in INS-1 832/13 cells

We investigated the effects of miR-375 on glucose-induced insulin secretion at 16.7 mm glucose in INS-1 832/13 cells. It has previously been reported that overexpression of miR-375 in MIN-6 cells negatively regulates insulin secretion (Poy et al. 2004). Surprisingly, we found that overexpression of miR-375 in INS-1 832/13 cells did not reduce glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (Fig. 2a). However, insulin content was reduced in the same cells with approx. 20% (Fig. 2b). The same experiment was repeated in LNA375 cells with no significant differences in insulin secretion (data not shown).

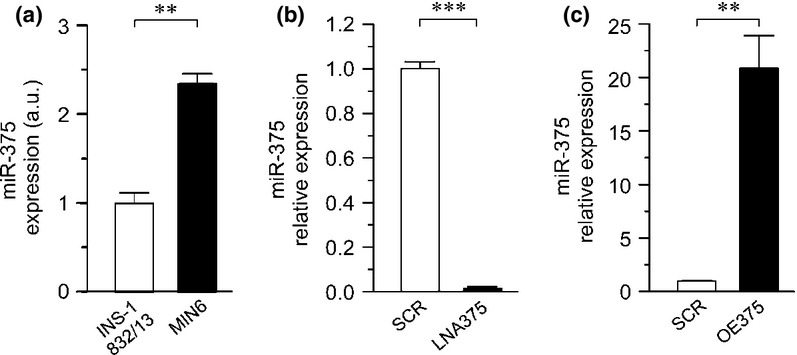

Figure 2.

Effects of miR-375 on insulin secretion and exocytosis in INS-1 832/13 cells. (a) Insulin secretion measured in OE375 (black bars) and SCR (white bars) cells. The cells were incubated for 1 h in low (2.8 mm) or high (16.7 mm) glucose as marked in the figure. (b) Changes in insulin content displayed as fold change after overexpression of miR-375 (OE375; black bar) compared to control (SCR; white bar). (c) Example traces of depolarization-induced exocytosis, measured as changes in cell membrane capacitance, in a OE375 and a SCR cell. Exocytosis was evoked by a train of ten 500 ms depolarizing pulses from −70 to 0 mV. (d) Summary of the total capacitance changes displayed as the sum of the capacitance changes from each of the ten depolarizations during the train. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of three biological experiments, with three technical replicates in each experiment in (a, b) and 23–35 cells in (d). *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

β-cell exocytosis is increased compared to control in the miR-375 KO mouse, although insulin secretion is not affected (Poy et al. 2009). We therefore measured exocytosis in OE375 and LNA375 cells. We utilized the standard whole-cell configuration of the patch-clamp technique and measured exocytosis as changes in membrane capacitance. Exocytosis was elicited by a train of ten 500-ms depolarizing pulses from −70 to 0 mV, a protocol similar to that used in the miR-375 KO mouse (Poy et al. 2009). In OE375 cells, the sum of the increase in membrane capacitance evoked by the 10 depolarizations was 244 ± 30 fF (n = 35) compared to 380 ± 54 fF (n = 23; P < 0.05) in SCR (Fig. 2d). In these experiments, the average cell size did not differ significantly between OE375 and SCR (5.8 ± 0.2 vs. 6.2 ± 0.4 pF).

Above set of experiments was repeated in LNA-375 cells. Here, the summed increase in membrane capacitance evoked by the train amounted to 117 ± 15 fF (n = 8) in LNA-375 and 170 ± 35 fF (n = 12; NS) in SCR. Also here, the average cell size did not differ between the LNA-375 and SCR cells (5.5 ± 0.7 vs. 4.8 ± 0.4 pF).

Effect of miR-375 on voltage-gated channel activity in INS-1 832/13 cells

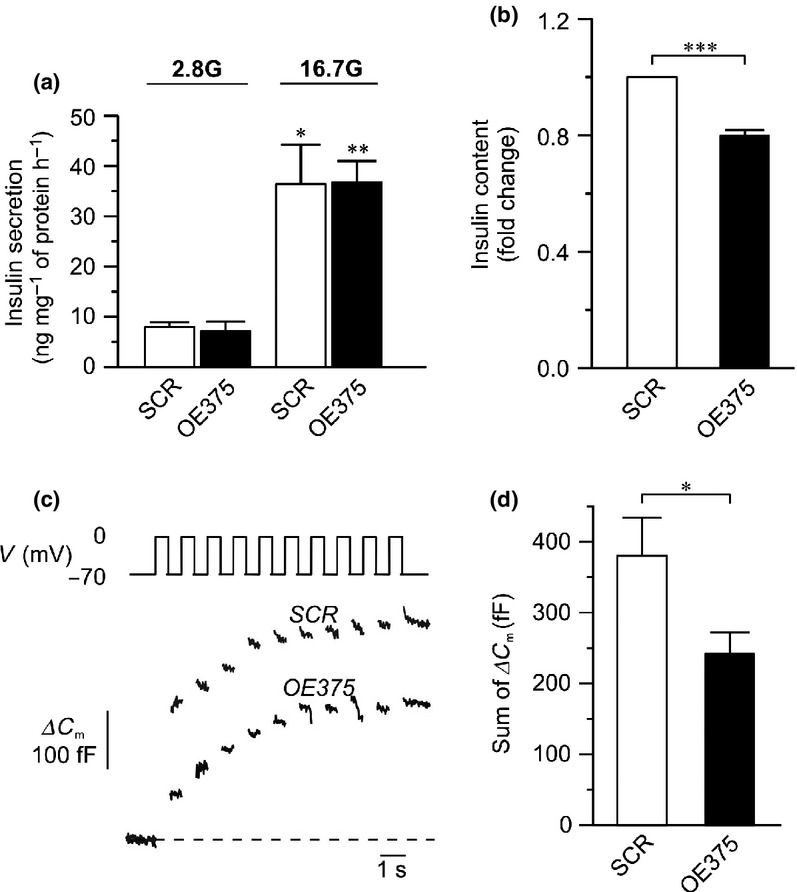

Exocytosis in β-cells is closely linked to the influx of Ca2+ through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Ammala et al. 1993). Therefore, we investigated the current–voltage relationships of the voltage-dependent currents in OE375 cells. Currents were evoked by membrane depolarizations from −70 mV to voltages between −40 and +40 mV. The peak current (Ip) and sustained current (Isus) were measured as illustrated in Figure 3a. The voltage-dependent current is due to ion fluxes through both voltage-gated Na+ and Ca2+ channels. As the Na+ current is larger and more rapidly inactivated, Ip is a reflection of the Na+ current whereas Isus and charge (Q) are related to the Ca2+-current. We verified that we could distinguish between Na+ and Ca2+ currents with these criteria by adding TTX, which selectively inhibits voltage-gated Na+ channels. The presence of TTX completely abolished Ip (data not shown). The maximal Isus at 0 mV amounted to −148 ± 19 pA (n = 33) and −218 ± 28 pA (n = 23; P < 0.05) in OE375 and SCR respectively (Fig. 3b). As can be seen in Figure 3c, charge (Q) was reduced accordingly. The same experiment was repeated in LNA375 cells. Here we saw no difference in the maximal Isus and consistent with this, there was also no difference in Q at any of the voltages tested. Moreover, Ip was unchanged in OE375 (Fig. 3d), and LNA-375 (data not shown) at all voltages measured suggesting that the peak Na+ current is not regulated by miR-375.

Figure 3.

Electrophysiological investigation of voltage-gated ion channels in OE375 and SCR cells. (a) Example traces of ion currents evoked by a depolarization to 0 mV in a single OE375 and SCR cell. Isus and Ip measured in (b) and (d) are highlighted. Charge (Q) displayed in (c) is measured as the area enclosed by the curve, starting 2 ms after the onset of the pulse (to exclude the Na+ current). (b) Sustained current (Isus)–voltage (V) relationship (c) charge (Q)–voltage (V) relationship and (d) peak current (Ip)–voltage (V) relationship measured in single OE375 (black dots) or SCR (white squares) cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of 23–33 cells in each group.

MiR-375 influences Na+ channel inactivation properties in INS-1 832/13 cells and mouse primary β-cells

Inactivation properties of voltage-gated Na+ channels can be measured with patch-clamp technology in the whole-cell configuration using a standard two-pulse protocol. Here we utilized a conditioning pulse from −70 mV to voltages ranging from −130 to 40 mV; a subsequent 1-ms resisting period at −70 mV was followed by a depolarizing pulse to 0 mV during which the Na+ channel response was measured (exemplified in Fig. 4a), and the relationship between the voltage of the conditioning pulse (Vm) and the peak current amplitude was determined (Fig. 4). Conditioning pulses lower than −90 mV have little effect on the subsequent peak current. However, for more positive conditioning pulses, the peak current was reduced in a voltage-dependent manner. To estimate the conditioning voltage when the subsequent peak Na+ current is half maximally inactivated, the data points can be fitted to the equation:

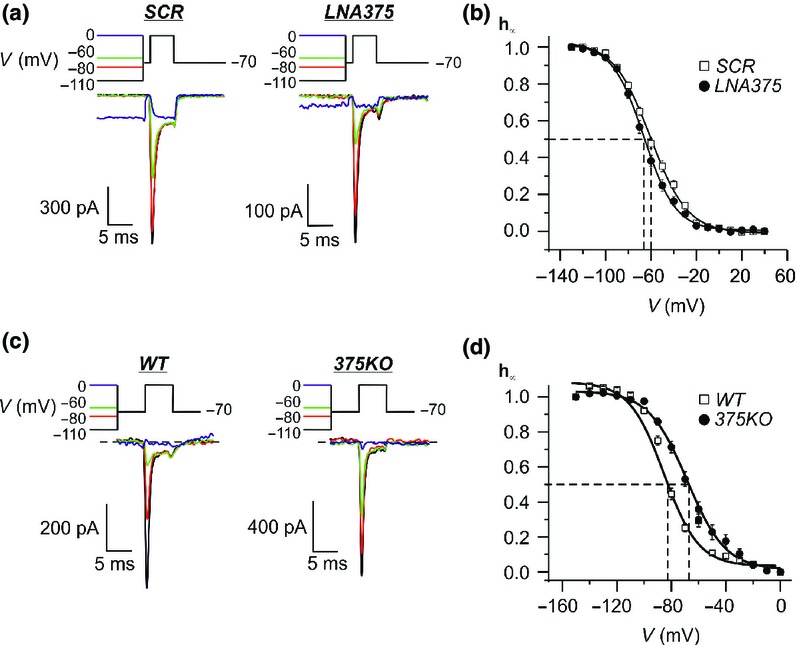

Figure 4.

The influence of miR-375 on voltage-gated Na+ channel properties in INS-1 832/13 and mouse primary β-cells (a) Example traces of ion currents from SCR and LNA375 cells evoked by a two-pulse protocol with a conditioning pulse from −70 to −110 mV (black line), −80 mV (red line), −60 mV (green line) and 0 mV (blue line). After a short resting period at −70 mV, a depolarizing pulse to 0 mV was applied. The Na+ channel response was measured during the latter pulse. (b) Summary of data from (a) presented as the relative Na+ current (h∞) plotted against the voltage (V) for SCR (white squares) and LNA375 (black dots) cells. Marked with dotted lines is the voltage when the Na+ channels are half maximally inactivated (Vh). (c) As in (a) but data are obtained from primary β-cells from wild type (WT) and miR-375 KO (375 KO) mice. (d) As in (b) but plotting the relative Na+ current (h∞)–voltage (V) relationship for WT (white squares) and 375 KO (black dots) primary β-cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM of 16–24 cells in each group.

| (1) |

Here h∞ is the relative Na+ current, Vh is the voltage when the Na+ channels are half maximally inactivated (h∞ = 0.5) and kh is the steepness coefficient. The relative Na+ current h∞ was calculated as (I−Imin)/(Imax−Imin), where I is the peak current recorded following a given conditioning pulse, Imax is the measured peak current following the conditioning pulse to −130 mV and Imin is the measured minimum current (Ca2+ current; left when the Na+ current is inactivated following the conditioning pulse to +40 mV). In a series of 17 experiments, Vh averaged −55 ± 2 mV in SCR cells. This value did not differ in OE375 cells where Vh averaged −54 ± 3 mV (n = 24 cells). Interestingly, Vh was significantly shifted to the left in LNA375 cells and averaged −66 ± 2 mV (n = 16 cells) compared to −60 ± 2 mV in SCR cells (n = 18; P < 0.05) (Fig. 4b).

The same experiment was repeated in dispersed islet β-cells from miR-375 KO mice and their littermate controls (WT). Here we delivered a conditioning pulse ranging from −150 to 0 mV; and a subsequent 5 ms resting period at −70 mV followed by a depolarizing pulse to 0 mV during which the Na+ channel response was measured (Fig. 4c). Interestingly, in these experiments, we detect a right hand shift of the half maximum inactivation Vh from −83 ± 1 mV (n = 21 cells) in WT to Vh −69 ± 2 mV (n = 24 cells; P < 0.001) in the miR-375 KO animals (Fig. 4d).

Putative target of miR-375 in the Na+ channel family

To show similar miR-375-mediated regulation between mouse β-cells and rat INS-1 832/13 cells, we measured the expression of miR-375 targets by qPCR previously validated in mouse β-cells such as Mtpn, Cadm1, Cav1, Aifm1 and Gphn (Poy et al. 2009) in OE375 cells. Except for Mtpn, we found that the other targets were negatively regulated by miR-375 in INS-1 832/13 cells on the mRNA level (Figure S1).

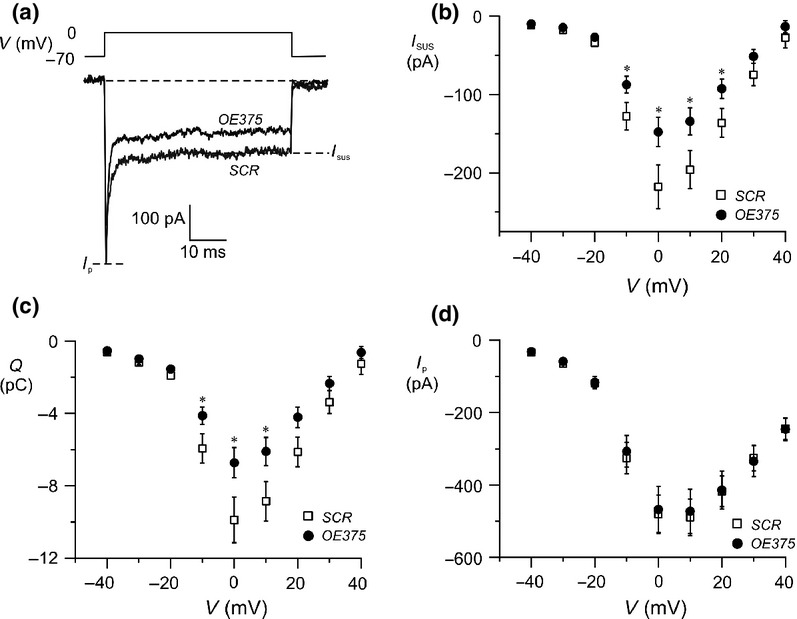

The novel finding that down-regulation of miR-375 has an effect on voltage-gated Na+ channel function prompted us to perform target prediction using TargetScan (Lewis et al. 2005) to determine which isoform(s) of the Na+ channel might be regulated by miR-375. The predicted targets of miR-375 in rat were Scn3a, Scn2b and Scn4b (Fig. 5a). Of these, Scn2b is also predicted as a target of miR-375 in mouse and human. However, qPCR revealed that of the predicted targets, only Scn3a is expressed in INS-1 832/13 cells. We also detected the expression of Scn3b in these cells (Fig. 5b). When evaluating the regulatory subunits SCN3A and SCN3B in OE375 cells, we could detect a decrease on protein level by approx. 30% of the two subunits with a P-value for SCN3A of <0.05 and P = 0.057 for SCN3B (Fig. 5c). In LNA375 cells, Scn3a and Scn3b gene expression was marginally (approx. 10%) but not significantly increased (data nor shown).

Figure 5.

Exploration of potential targets for miR-375 within the voltage-gated Na+ channel family (a) Schematic of TargetScan prediction of putative targets among the subunits forming voltage-gated Na+ channels in human, rat and mouse. (b) The relative expression of the voltage-gated Na+ channel subunits Scn3a and Scn3b in OE375 (black bars) normalized to control (SCR; white bars). (c) Western Blot detecting SCN3A and SCN3B in SCR and OE375 cells (bottom). Above is a summary of 3 experiments where the intensity of the generated bands is related to beta-actin. Data in (b) is mean of three biological experiments with three replicates in each experiment.*P ≤ 0.05.

Discussion

MiR-375 is clearly expressed in INS-1 832/13 cells. However, down-regulation of miR-375 has no effect on vesicle exocytosis, which differ from the increase in exocytosis reported in the β-cells from miR-375 KO mice (Poy et al. 2009). Interestingly, over-expressing miR-375 in INS-1 832/13 cells recapitulates the observed decrease in exocytosis measured in MIN-6 cells and mouse islet β-cells over-expressing miR-375 (Poy et al. 2004). The effect of miR-375 on exocytosis in mouse β-cells has been suggested to go via myotrophin, a rather uncharacterized exocytotic protein (Poy et al. 2004). Myotrophin mRNA is also expressed in INS-1 832/13 cells but unlike the other validated targets in mouse β-cells, the mRNA levels of myotrophin are not affected by miR-375 overexpression (Figure S1). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that myotrophin is down-regulated at protein level in INS-1 832/13 cells upon miR-375 overexpression, the effect of modulating miR-375 on exocytosis cannot be exclusively due to regulation of myotrophin expression.

Another possibility is that the cell line INS-1 832/13 is not as tightly regulated by miR-375 as the other cells tested due to dose effects. This notion is supported by our finding that INS-1 832/13 expresses lower levels of miR-375 compared to MIN-6 cells (Fig. 1a). MiR-375 has been shown to be down-regulated in pancreatic cancer tissue (Zhou et al. 2012), and it is therefore not unlikely that the β-cell line INS-1 832/13 cells, which is a fast dividing cell line mimics this situation. Overexpression of miR-375 overrides this which could explain that we can detect effects on exocytosis in OE375 cells.

Contradictory to what has been previously reported (Poy et al. 2004) overexpression of miR-375 reduced Ca2+ influx trough voltage-gated Ca2+ channels by approx. 30% (Fig. 3). In mouse primary β-cells, it has been reported that a approx. 30% blockage of the Ca2+ current resulted in a <25% reduction in exocytosis (Renstrom et al. 1996). We can therefore not exclude the possibility that although the reduced Ca2+ influx probably explains the majority of the approx. 35% reduction in exocytotic response other factors might be involved (Fig. 2d). It is interesting that down-regulation of the miR-375 had no effect on the Ca2+ current. We can only speculate why this is the case and one interpretation is that if miR-375 functions as a rheostat (Bartel 2009), the voltage-gated Ca2+ channel regulation might be low when the microRNA is expressed at physiological levels or below. However, an overexpression of mir-375 by approx. 20× shifts the levels of the microRNA enough to induce a tighter regulation of the ion channel. Another possibility is that when high levels of the microRNA are induced this might allow for binding to less specific targets of the microRNA. Both scenarios could explain the discrepancy between our current findings and those described previously.

We report the novel finding that inactivation of voltage-gated Na+ channels in both INS-1 832/13 cells and primary mouse β-cells is regulated by miR-375. Pancreatic β-cells are electrically active and generate action potentials which trigger insulin secretion (MacDonald 2011). The role of Na+ channels in action potential firing in β-cells is not fully understood and seems to vary between species. Intracellular ATP has been reported to affect the kinetics of mouse β-cell Na+ channels indicating that glucose plays a role in the regulation of Na+ channels (Zou et al. 2013). Under the right circumstances, small changes in Na+ channel kinetics can cause a considerable change in the number of channels available for generation of action potentials as steady-state inactivation controls the number of channels that can be opened (Van Petegem et al. 2012). Thus, the small shift in the Na+ inactivation curve generated by miR-375 down-regulation (Fig. 4) could in theory lead to changes in insulin secretion. In the miR-375 KO mouse, there is no apparent difference in insulin secretion with the data normalized to insulin content. However, as pointed out in this study, it is possible that the insulin secretion from individual β-cells might be enhanced (Poy et al. 2009). Likewise we detect no significant change in insulin secretion from LNA375 compared to SCR. We conclude that any effect on insulin secretion generated by miR-375 regulation of Na+ channels, and the exocytotic machinery is too small to detect with standard static incubation protocols in mouse islets and INS-1 832/13 cells or is overridden by other confounding effects of miR-375 modulation in INS-1 832-13 cells. In this context, it is interesting to note that in mouse-derived cell lines such as MIN-6 cells and Nit-1 cells overexpression of miR-375 leads to reduced glucose-induced insulin secretion (Poy et al. 2004, Xia et al. 2011). To our knowledge, the same experiment has not been conducted in rat-derived cell lines such as INS-1 832/13 prior to this study.

Whereas down-regulation of miR-375 affects Na+ channel inactivation, overexpression of miR375 does not generate a shift in the Na+ channel inactivation curve. The reason for this is unclear, but one possibility is that the regulation of voltage-gated Na+ channels in our system is already at its maximum and further increasing the miR-375 levels can therefore not increase the regulation further.

This study provides the first report that voltage-gated Na+ channels are regulated by miR-375 in rodent insulin-secreting cells. It is important to establish whether voltage-gated Na+ channels in human β-cells are also regulated by miR-375 and how this might influence action potential firing and insulin secretion. In this context, one should remember that Na+ channels are active in glucose-induced insulin secretion in humans. Moreover, half-maximal inactivation of the Na+ channels in human β-cells occurs at around −40 mV (Braun et al. 2008), which suggests that human β-cells could be expected to be more sensitive to a shift in steady-state inactivation caused by variations in miR-375 levels.

It is surprising that the shift in the steady-state inactivation curve goes in opposite directions in INS-1 832/13 cells compared to primary mouse β-cells. Inactivation properties of the voltage-gated Na+ channels vary between isoforms (Ulbricht 2005), and it is possible that our two cell systems express different subunits of the Na+ channels. In addition, species specificity among targets of conserved miRNAs has previously been reported in the Nodal pathway of human embryonic stem cells and Xenopus laevis (Rosa et al. 2009). In the light of our findings, it is therefore tempting to speculate that the regulation of Na+ channels by miR-375 is at the level of protein target expression. Indeed, predicted targets among the Na+ channel subunits differ between mouse and rat β-cells. We attempted to elucidate which Na+ channel subunit(s) are regulated by miR-375 in INS-1 832/13 cells and found that Scn3a, which was a predicted target by TargetScan, was not affected in LNA375 cells, neither was Scn3b. However, in OE375 cells (that did not display a shift in Na+ channel inactivation properties), we see a approx. 30% reduction of both subunits on protein level. Our interpretation of this is that the target(s) for miR-375 generating the shift in Na+ channel inactivation is still unknown. The 30% down-regulation of SCN3a/b in OE375 cells does not display a phenotype that we can detect with our methods and therefore the significance of this regulation is uncertain.

The generation of action potentials is crucial for insulin secretion. As of yet Na+ channels have largely been overlooked in this process mainly because they half maximally inactivate at potentials at or below the resting membrane potential in rodents. Experiments on human and mouse pancreatic β-cells have taught us that regulation of insulin secretion differs between the two (Rorsman & Braun 2013). In human β-cells, Na+ channels play a vital role for the onset of the action potential and regulation of these channels therefore emerges as a way to manipulate insulin secretion. Whether miR-375 is involved in regulation of Na+ channels in human β-cells remains to be investigated, but we have indications that miR-375 is increased in human islets from glucose intolerant donors (Bolmeson et al. 2011).

Acknowledgments

All authors would like to acknowledge our dear friend and colleague Dr Matthias Braun who sadly passed away during the preparation of this manuscript; he will always be fondly remembered in our hearts. We thank Anna-Maria Veljanovska Ramsay for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (Project grant LE; Linneaus grant LUDC; Strategic Research Area Exodiab), The Swedish Diabetes Association, The Diabetic Wellness Network Sweden, Region Skåne (ALF), The Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, The Albert Påhlsson Foundation and ERC Grant Metabolomirs (MS). LE is a senior researcher at the Swedish Research Council.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1. Exploration of verified mouse beta-cell targets for miR-375 in INS1-832/13 cells.

References

- Ammala C, Eliasson L, Bokvist K, Larsson O, Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Exocytosis elicited by action potentials and voltage-clamp calcium currents in individual mouse pancreatic B-cells. J Physiol. 1993;472:665–688. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolmeson C, Esguerra JL, Salehi A, Speidel D, Eliasson L, Cilio CM. Differences in islet-enriched miRNAs in healthy and glucose intolerant human subjects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;404:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun M, Ramracheya R, Bengtsson M, Zhang Q, Karanauskaite J, Partridge C, Johnson PR, Rorsman P. Voltage-gated ion channels in human pancreatic β-cells: electrophysiological characterization and role in insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2008;57:1618–1628. doi: 10.2337/db07-0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA, Goldin AL, Waxman SG. International Union of Pharmacology. XLVII. Nomenclature and structure-function relationships of voltage-gated sodium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:397–409. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson L, Esguerra JL. Role of non-coding RNAs in pancreatic beta-cell development and physiology. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2014;211:273–284. doi: 10.1111/apha.12285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson L, Abdulkader F, Braun M, Galvanovskis J, Hoppa MB, Rorsman P. Novel aspects of the molecular mechanisms controlling insulin secretion. J Physiol. 2008;586:3313–3324. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst SJ, Aguilar-Bryan L, Noebels JL. Sodium channel beta1 regulatory subunit deficiency reduces pancreatic islet glucose-stimulated insulin and glucagon secretion. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1132–1139. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiriart M, Matteson DR. Na channels and two types of Ca channels in rat pancreatic B cells identified with the reverse hemolytic plaque assay. J Gen Physiol. 1988;91:617–639. doi: 10.1085/jgp.91.5.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman WP, Lagendijk AK, Ketting RF, Moulton JD, Plasterk RH. Targeted inhibition of miRNA maturation with morpholinos reveals a role for miR-375 in pancreatic islet development. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolfschoten IG, Roggli E, Nesca V, Regazzi R. Role and therapeutic potential of microRNAs in diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11(Suppl 4):118–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald PE. Signal integration at the level of ion channel and exocytotic function in pancreatic β-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E1065–E1069. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00426.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson CS, Gopel SO, Barg S, Galvanovskis J, Ma X, Salehi A, Rorsman P, Eliasson L. Fast insulin secretion reflects exocytosis of docked granules in mouse pancreatic B-cells. Pflugers Arch. 2002;444:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-0781-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant TD. Na+ currents in cultured mouse pancreatic B-cells. Pflugers Arch. 1988;411:429–435. doi: 10.1007/BF00587723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, Macdonald PE, Pfeffer S, Tuschl T, Rajewsky N, Rorsman P, Stoffel M. A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature. 2004;432:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature03076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poy MN, Hausser J, Trajkovski M, Braun M, Collins S, Rorsman P, Zavolan M, Stoffel M. miR-375 maintains normal pancreatic alpha- and beta-cell mass. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5813–5818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810550106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renstrom E, Eliasson L, Bokvist K, Rorsman P. Cooling inhibits exocytosis in single mouse pancreatic B-cells by suppression of granule mobilization. J Physiol. 1996;494(Pt 1):41–52. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorsman P, Braun M. Regulation of insulin secretion in human pancreatic islets. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:155–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa A, Spagnoli FM, Brivanlou AH. The miR-430/427/302 family controls mesendodermal fate specification via species-specific target selection. Dev Cell. 2009;16:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulbricht W. Sodium channel inactivation: molecular determinants and modulation. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:1271–1301. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00024.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Petegem F, Lobo PA, Ahern CA. Seeing the forest through the trees: towards a unified view on physiological calcium regulation of voltage-gated sodium channels. Biophys J. 2012;103:2243–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidaltamayo R, Sanchez-Soto MC, Hiriart M. Nerve growth factor increases sodium channel expression in pancreatic beta cells: implications for insulin secretion. FASEB J. 2002;16:891–892. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0934fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter J, Jung S, Keller S, Gregory RI, Diederichs S. Many roads to maturity: microRNA biogenesis pathways and their regulation. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:228–234. doi: 10.1038/ncb0309-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H-Q, Pan Y, Peng J, Lu G-X. Over-expression of miR375 reduces glucose-induced insulin secretion in Nit-1 cells. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:3061–3065. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-9973-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Chibalina MV, Bengtsson M, Groschner LN, Ramracheya R, Rorsman NJ, Leiss V, Nassar MA, Welling A, Gribble FM, Reimann F, Hofmann F, Wood JN, Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Na+ current properties in islet alpha- and beta-cells reflect cell-specific Scn3a and Scn9a expression. J Physiol. 2014;592:4677–4696. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.274209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Song S, Cen J, Zhu D, Li D, Zhang Z. MicroRNA-375 is downregulated in pancreatic cancer and inhibits cell proliferation in vitro. Oncol Res. 2012;20:197–203. doi: 10.3727/096504013x13589503482734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou N, Wu X, Jin Y-Y, He M-Z, Wang X-X, Su L-D, Rupnik M, Wu Z-Y, Liang L, Shen Y. ATP regulates sodium channel kinetics in pancreatic islet beta cells. J Membr Biol. 2013;246:101–107. doi: 10.1007/s00232-012-9506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Exploration of verified mouse beta-cell targets for miR-375 in INS1-832/13 cells.