Abstract

A set of fluorophenoxyanilides, designed to be simplified analogues of previously reported ω-conotoxin GVIA mimetics, were prepared and tested for N-type calcium channel inhibition in a SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma FLIPR assay. N-type or Cav2.2 channel is a validated target for the treatment of refractory chronic pain. Despite being significantly less complex than the originally designed mimetics, up to a seven-fold improvement in activity was observed.

Keywords: N-type calcium channel, Cav2.2, channel blocker, pain, FLIPR

1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain, which results from nerve damage caused by surgery, trauma, infection or disease, often does not respond to existing therapies [1,2]. Various estimates put the proportion of the world’s population afflicted by this condition to be at least 3%, with up to 5% of postoperative patients being affected. Safe and effective therapies for neuropathic pain are therefore a major unmet medical need. N-Type calcium channels (Cav2.2 channels) are strongly implicated in chronic and neuropathic pain and their inhibitors have been widely pursued [1,2,3,4]. This approach has been best validated by Ziconotide (Prialt®), a synthetic version of the peptide ω-conotoxin MVIIA found in the venom of a fish-hunting marine cone snail Conus magnus. This peptide selectively targets Cav2.2 channels and is one of the very few effective drugs used to treat intractable chronic pain [5]. However, its intrathecal mode of delivery and narrow therapeutic window make it less than ideal as a treatment option.

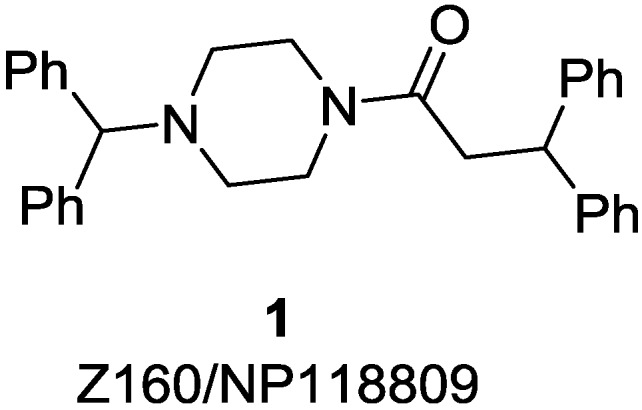

We as well as others have been developing small-molecule inhibitors of Cav2.2 channels as possible alternatives to Ziconotide [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Recently clinical development of Z160 (1, Figure 1), a reformulated form of NP118809 [8], was discontinued after Z160 (1) failed to meet the primary endpoint in Phase II clinical studies [30]. As a result there is only one compound that targets Cav2.2 channels currently in clinical trials for the treatment of chronic pain, CNV2197944, the structure of which is yet to be disclosed [24].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of Z160/NP11809 (1).

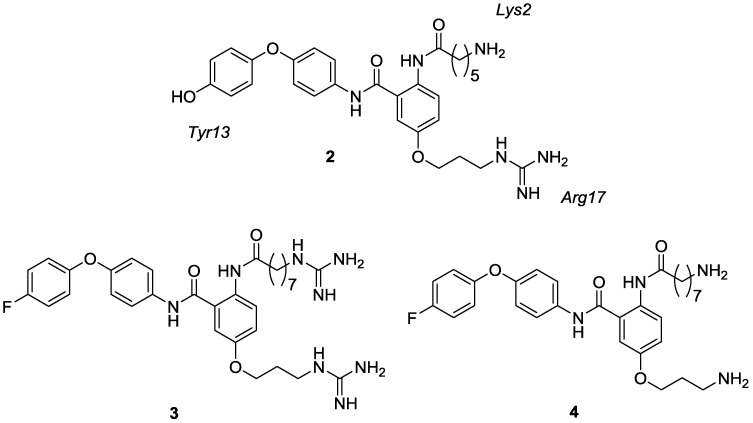

As part of an ongoing program to develop new small-molecule inhibitors of Cav2.2 channels, the pharmacophore of ω-conotoxin GVIA, a 27 residue peptide present in the venom of the cone snail Conus geographus, has been investigated. This peptide binds essentially irreversibly to the Cav2.2 channel, making it unattractive as a therapeutic, however its well-defined structure has facilitated the development of peptidomimetics. A number of such mimetics have been disclosed [25,26,27,28,29], developed using the α,β-bond vector strategy described by Bartlett and Lauri [31], combined with interactive de novo design [32]. In these mimetics the biologically relevant tyrosine, lysine and arginine side chain mimics are projected from a central scaffold, as illustrated by the anthranilamide derivative (2) (Figure 2) [27,32]. Guided by the results of a radioligand-displacement assay, it has been concluded that with these anthranilamide-based mimetics (Compounds 2–4, Figure 2) the optimum length of the alkyl side chains is n = 7 for the lysine mimic and n = 3 for the arginine mimic. It was also found that the replacement of the phenol functionality with fluorine is well tolerated [25]. The most potent fluorinated analogue in this series was found to be the diguanidino compound (3) while the corresponding diamino compound (4) had comparatively weak activity. This is consistent with previous results where truncation of the arginine side chain mimic to an amine in ω-conotoxin GVIA mimetics is typically detrimental to activity at the N-type channel [25,26,27,28,29].

Figure 2.

Structures of previously synthesised anthranilamide-based ω-conotoxin GVIA mimetics (2–4) [25,27].

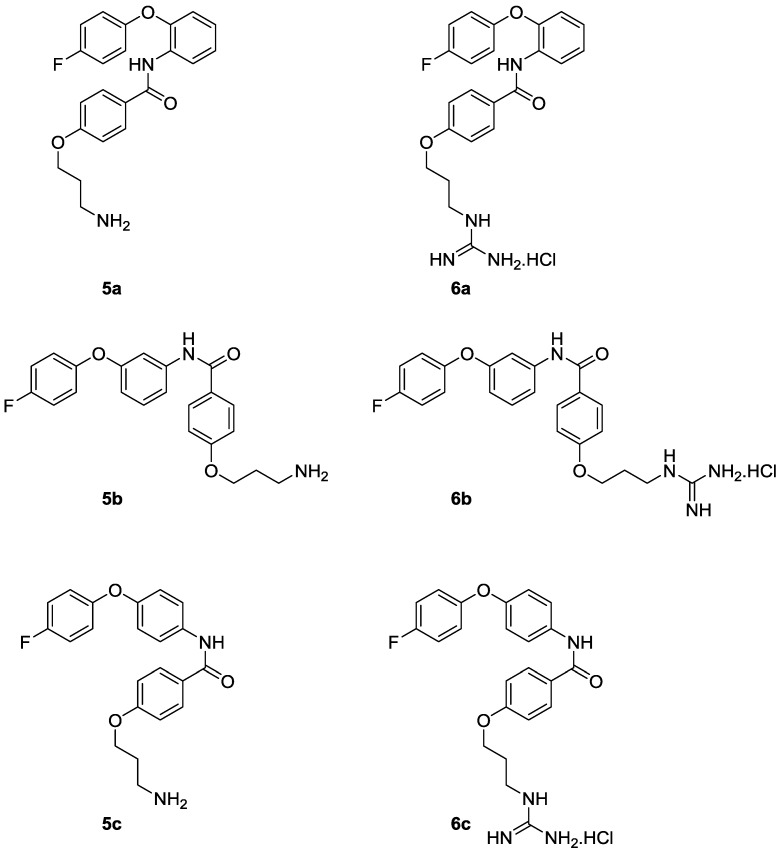

In order to transition conotoxin mimics towards more drug-like compounds, a number of their physiochemical properties need to be adjusted. Marketed central nervous system (CNS) active drugs, for example, tend to have much lower molecular weights, percentage polar surface areas, total number of nitrogen and oxygen atoms, and hydrogen bond acceptors and donors than are found in mimetics like 2. We have therefore embarked on a program of molecular modifications aimed at improving the physiochemical properties of this class of conotoxin mimics while retaining activity at the N-type calcium channel. A major priority has been to reduce overall molecular weight. Encouraged by favourable results obtained with the simplification of a benzothiazole class of mimetics, which involved the deletion of one of the amino acid side chain mimics [28], a similar strategy has been pursued with the anthranilamides. Thus, in the study described here, the effect on activity of the deletion of the lysine side chain mimic in compounds 2–4 has been investigated, together with the SAR related to the substitution pattern of the central aromatic ring (ortho, meta or para). The amino analogues and their corresponding monoguanidino analogues that were synthesised and tested in this study are shown in Figure 3, compounds 5a–c and 6a–c.

Figure 3.

Analogues 5a–c and 6a–c targeted in this study.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

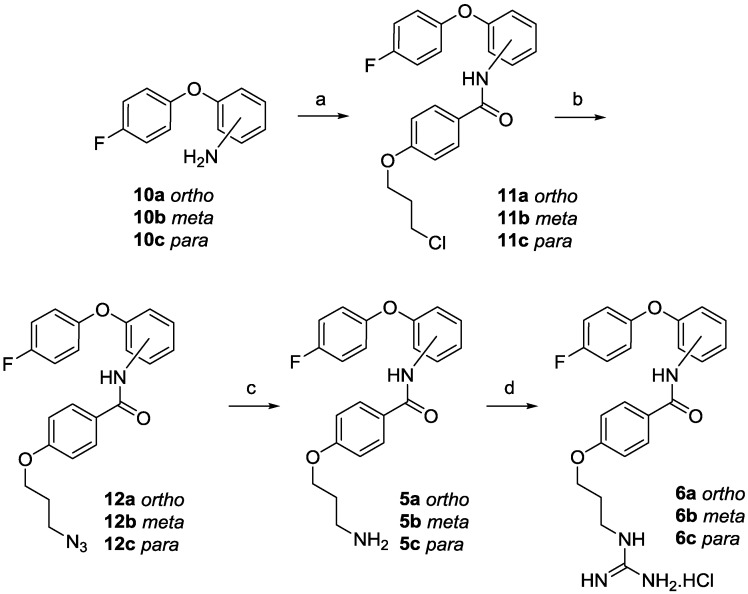

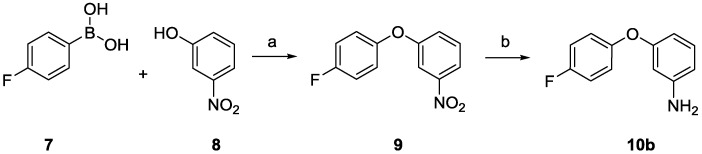

The previously described synthetic route to the anthranilamide-based mimics (3 and 4) [25] was modified to allow incorporation of the chloropropoxybenzamide moiety and its subsequent derivatisation. The ortho and para phenoxyl anilines (10a [33,34] and 10c [25]) were readily available and the required meta phenoxyl aniline (10b) was synthesized in two steps from 4-fluorophenyl boronic acid (7) and meta-nitrophenol (8) via the intermediate phenoxynitrobenzene (9) (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of meta-(4-fluorophenoxy)aniline (10b). Reagents and conditions: (a) Cu(OAc)2, Et3N, air, 4 Å molecular sieves, dichloromethane (DCM), room temperature (RT), 24 h 83%; (b) Pd/C, NH2NH2·H2O, EtOH, RT, 4 h, 95%.

With the required 4-fluorophenoxyanilines (10a–c) in hand, the desired ortho, meta and para amino phenoxy anilides (5a–c) and monoguanidino phenoxy anilides (6a–c) were synthesised, as outlined in Scheme 2. Reaction of the phenoxyl aniline (10a–c) with 4-(3-chloropropoxy)benzoic acid [35,36], using either carbodiimide activation [37] or formation of the acid chloride, gave the desired chloro compounds (11a–c). Subsequent conversion to the azide (12a–c) with sodium azide, followed by a transfer-hydrogenation reaction provided the corresponding amines (5a–c). Treatment of amines (5a–c) with 1H-pyrazole-carboxamidine [38] furnished the phenoxy anilides (6a–c) as hydrochloride salts.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of phenoxy anilides (5a–c and 6a–c). Reagents and conditions: (a) 4-(3-chloropropoxy)benzoic acid, 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC·HCl), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), Et3N, DCM/tetrahydrofuran (THF), (11a) 47%, (11b) 81% or 4-(3-chloropropoxy)benzoyl chloride, THF, (11c) 70%; (b) NaN3, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 70 °C, (12a) 95%, (12b) 99%, (12c) 92%; (c) Pd/C, NH2NH2·H2O, MeOH, (5a–c) quant.; (d) 1H-pyrazole-1-carboximidine hydrochloride, N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), dimethylformamide (DMF), (6a–c) quant.

2.2. Biology

It has been shown that SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells endogenously expressing human Cav2.2 channels allow the rapid screening of potential channel blockers by means of a FLIPR assay [39]. The synthesised compounds, the amino (5a–c) and the guanidinium (6a–c) analogues, as well as the anthranilamide-based mimetic (3), were evaluated for their ability to inhibit Cav2.2 calcium responses in SH-SY5Y cells in the presence of the L-type calcium channel blocker nifedipine. It was found that Ca2+ ion channel responses elicited by KCl-mediated depolarization were inhibited in a dose-dependent manner (Table 1). Compound 3 only partially inhibited responses at a concentration of 1 mM, resulting in an estimated IC50 value of 1452 µM. In contrast, 5a and 5b fully blocked KCl-induced Ca2+ responses with IC50s of 46 µM and 35 µM, respectively. In the guanidinium series, 6a and 6b retained weaker activity with IC50 values of 124 µM and 185 µM respectively. [40] Both para substituted compounds, 5c and 6c, were only weakly active and partially inhibited responses with IC50 values of 764 µM and 723 µM, respectively.

Table 1.

Functional inhibition of calcium channels by compounds 3, 5a–c, 6a–c.

| Compound | logIC50 | SEM | IC50 (µM) | 95% CI (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 a | ~–2.84 | 0.29 | 1452 b | 380–5550 |

| 5a | –4.34 | 0.01 | 46 | 44–48 |

| 6a | –3.90 | 0.03 | 124 c | 107–150 |

| 5b | –4.45 | 0.01 | 35 | 33–37 |

| 6b | –3.73 | 0.02 | 185 | 169–203 |

| 5c | ~–3.12 | 0.06 | 764 d | 575–1020 |

| 6c | –3.14 | 0.10 | 723 e | 447–1170 |

a This compound gave an IC50 of 6 µM in a radioligand displacement assay with 125I-GVIA [25] but it has since been established that it is less potent in an assay of functional activity at Cav2.2. [29]; b% Max inhibition, 15% at 300 µM; c% Max inhibition, 65% at 300 µM; d% Max inhibition, 30% at 300 µM; e% Max inhibition, 19% at 300 µM.

Compared to compound 3, compounds 5a–c and 6a–c are significantly less complex and have molecular weights reduced by 33%–45%. It is encouraging, therefore, to find that all but 5c and 6c are considerably more active than 3. A relationship between the substitution pattern around the central aromatic ring and biological activity can also be clearly seen, with the ortho and meta analogues showing considerably stronger activity than the para analogues. It is also interesting to note that the amino compounds 5a–b are three to five fold more active than the guanidino compounds 6a–b.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. General Experimental Procedures

Starting materials and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Sydney, Australia) and used without purification. Solvents were dried, when necessary, using standard methods. Normal phase flash chromatography was performed on Merck silica gel No. 9385. Spectra were recorded on a Bruker Av400 or Av600 spectrometer (Fallanden, Switzerland). NMR spectra were referenced to residual solvent peak [chloroform (δH 7.26, δC 77.2), methanol (δH 4 .87, 3.30, δC 49.0)]. The units for all coupling constants (J) are in hertz (Hz). ‡Denotes signals only observed in 2D NMR. Mass spectrometry (APCI) was performed on a Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive FTMS. High-resolution mass spectra were recorded on a Waters Q-TOF II (Manchester, UK) or Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive FTMS mass spectrometer (Bremen, Germany). Melting points were recorded on a Stuart Scientific Melting Point Apparatus SMP3. Infrared spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer RXI FTIR Spectrometer as thin films. Preparative HPLC was performed on a Waters Prep LC 4000 System using an Alltima C18 column (22 × 250 mm, 5 micron), detection at 237 nm. Mobile phase 12 mL/min 30% CAN/H2O/0.2% TFA isocratic for 135 min then 115 min gradient to 100% ACN containing 0.2% TFA.

3.1.2. Synthesis

4-(3-Chloropropoxy)-N-(2-(4-fluorophenoxy)phenyl)benzamide (11a)

Alkyl chloride 11a was synthesised using a modified procedure outlined by Altin et al. [37]. A solution of 4-(3-chloropropoxy)benzoic acid [36] (1.27 g, 5.91 mmol) in dry THF (50 mL) was stirred under N2 at room temperature. Triethylamine (0.80 mL, 600 mg, 6.22 mmol) and DMAP (340 mg, 2.79 mmol) were added to the reaction mixture, followed by EDC·HCl (867 mg, 4.54 mmol). After 15 min a solution of the 2-(4-fluorophenoxy)aniline 10a [33,34] (800 mg, 3.94 mmol) in dry DCM (20 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred under N2 atmosphere at room temperature. After 48 h the THF was removed in vacuo before the residue was taken up in DCM (50 mL). The organic layer was washed with saturated NaHCO3 (3 × 50 mL), dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated to afford a brown oil. Purification by column chromatography (hexanes: EtOAc; 7:2) yielded the alkyl chloride 11a as a colourless solid (711 mg, 47%). Mp: 101.5–103.5 °C. IR (ATR): 3333 s, 3113 w, 2942 w, 1653 s, 1600 s, 1497 s, 1446 s, 1310 m, 1250 s, 1196 s, 1173 s, 1036 m, 829 m, 764 m cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.59 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.41 (br s, 1H), 7.81–7.77 (m, 2H), 7.19–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.09–7.01 (m, 5H), 6.97–6.94 (m, 2H), 6.83 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.5 Hz), 4.17 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.75 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.26 (quin, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): 165.0, 161.9, 159.4 (d, J = 241.3 Hz), 152.3, 146.4, 130.0, 129.2, 127.5, 124.3, 124.1, 121.1, 120.5 (d, J = 8.3 Hz), 117.3, 116.8 (d, J = 23.5 Hz), 114.7, 64.7, 41.4, 32.2. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3): δ −119.4. LRMS (APCI): m/z 400.1 [M + H]+ (100%), 288.1 [M − C6H4FO]+ (48%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. For C22H1935ClFNO3 [M + H]+•: 399.1032, found: 399.1032.

4-(3-Azidopropoxy)-N-(2-(4-fluorophenoxy)phenyl)benzamide (12a)

The azide 12a was synthesised according to a procedure outlined by Alvarez et al. [41] Sodium azide (95 mg, 1.5 mmol) was added to a solution of alkyl chloride 11a (0.45 g, 1.1 mmol) in DMSO (3 mL) and stirred under N2 atmosphere at 70 °C. After 48 h, the reaction mixture was allowed to cool and DCM (30 mL) was added. (CAUTION: It is recommended that DCM be substituted with diethyl ether for larger scale reactions, to avoid the formation of hazardous side products such as azido-chloromethane and diazidomethane) The organic layer was washed with brine (5 × 50 mL), dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated to provide azide 12a as a pale brown solid (377 mg, 95%). 1H NMR spectroscopy deemed this solid to be pure enough to use in the next step. Mp: 69.2–71.2 °C. IR (ATR): 3430 s, 3071 w, 2935 w, 2093 s, 1668 s, 1602 s, 1499 s, 1442 s, 1309 m, 1244 s, 1194 s, 1036 w, 841 m, 758 m cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.59 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.41 (br s, 1H), 7.81–7.77 (m, 2H), 7.18–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.09–7.00 (m, 5H), 6.96–6.93 (m, 2H), 6.83 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 4.10 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.52 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.07 (quin, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 164.9, 161.7, 159.3 (d, J = 241.4 Hz), 152.3, 146.4, 129.9, 129.1, 127.5, 124.3, 124.1, 121.0, 120.4 (d, J = 8.3 Hz), 117.2, 116.7 (d, J = 23.3 Hz), 114.6, 64.9, 48.2, 28.8. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3): δ −119.4. LRMS (APCI): m/z 407.2 [M + H]+ (100%), 204.1 [M − C10H8N3O2]+ (39%), 381.2 [M − N2 + 3H]+ (26%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. For C22H19FN4O3 [M]+•: 406.1436, found: 406.1438.

4-(3-Aminopropoxy)-N-(2-(4-fluorophenoxy)phenyl)benzamide (5a)

A solution of azide 12a (100 mg, 0.25 mmol), 10% Pd/C (12 mg) and hydrazine monohydrate (30 µL, 30 mg, 0.62 mmol) in MeOH (3 mL) was vigorously stirred under N2 at room temperature. After 20 min, the reaction mixture was filtered through Celite™ and concentrated to provide the amino compound 5a as yellow oil in a quantitative crude yield. A small amount was purified by reversed-phase HPLC to give a sample for biological testing. IR (ATR): 3432 br, 3071 w, 2942 w, 2873 w, 1653 s, 1601 s, 1493 s, 1378 m, 1248 s, 1203 s, 1173 s, 838 m, 758 m cm−1. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.90–7.89 (m, 1H), 7.76–7.74 (m, 2H), 7.18–7.17 (m, 2H), 7.05–6.99 (m, 7H), 4.08 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.81 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 1.95–1.91 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD): δ 168.2, 163.5, 160.7 (d, J = 238.9 Hz), 154.3, 150.8, 130.5, 130.4, 127.6, 127.4, 126.7, 125.0, 120.8 (d, J = 7.8 Hz), 120.0, 117.2 (d, J = 23.6 Hz), 115.3, 67.3, 39.6, 33.3. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CD3OD): δ −120.5. LRMS (APCI): m/z 381.2 [M + H]+ (50%), 380.2 [M]+ (100%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. For C22H21FN2O3 [M]+•: 380.1531, found: 380.1532.

N-(2-(4-Fluorophenoxy)phenyl)-4-(3-guanidinopropoxy)benzamide hydrochloride (6a)

The guanidinylated compound 6a was synthesized according to a modified procedure by Bernatowicz et al. [38]. Amine 5a (102 mg, 0.24 mmol), DIPEA (42 µL, 31 mg, 0.24 mmol), 1H-pyrazole-1-carboximidine hydrochloride (35 mg, 0.24 mmol) and DMF (2 mL) were combined and stirred vigorously under N2 atmosphere at room temperature. After 18 h TLC analysis revealed that starting material remained, additional 1H-pyrazole-1-carboximidine hydrochloride (9 mg, 0.06 mmol) and DIPEA (10 µL, 8 mg, 0.06 mmol) were added. After a further 24 h the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield the guanidinylated compound 6a as crystalline product. This solid was dissolved in MeOH (1 mL) and the product precipitated by addition of Et2O (10 mL). After removal of the residual solvent the product was obtained as a crystalline solid (47 mg, 39%) IR (ATR): 3307 br s, 3251 br s, 3139 br s, 1643 s, 1601 s, 1497 s, 1443 s, 1245 s, 1196 s, 1174 s, 840 m, 759 m cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.88–7.85 (m, 1H), 7.78–7.76 (m, 2H), 7.21–7.18 (m, 2H), 7.07–6.98 (m, 6H), 6.97–6.94 (m, 1H), 4.13 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 3.41 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.11-2.05 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 168.2, 163.2, 160.2 (d, J = 239 Hz), 158.7, 154.4, 151.0, 130.5, 130.4, 127.9, 127.6, 126.9, 125.0, 120.8 (d, J = 8.3 Hz), 120.1, 117.2 (d, J = 23.4 Hz), 115.4, 66.3, 39.5, 29.5. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CD3OD): δ −120.6. LRMS (APCI): m/z 422.2 [M]+ (62%), 380.15 [M − CH2N2]+ (100%). HRMS (ESI): m/z calcd. For C23H23FN4O3 [M]+•: 422.1749, found: 422.1750.

1-(4-Fluorophenoxy)-3-nitrobenzene (9)

The fluoro diaryl ether 9 was synthesised according to a general procedure outlined by Evans et al. [42] 4-Fluorophenyl boronic acid 7 (300 mg, 2.16 mmol), m-nitrophenol 8 (200 mg, 1.44 mmol), Cu(OAc)2 (260 mg, 1.44 mmol) and freshly activated powdered 4 Å molecular sieves were added to dry DCM (15 mL). Et3N (1.0 mL, 730 mg, 7.19 mmol) was then added to the reaction mixture. The reaction left open to air through a drying tube and stirred at room temperature, and reaction progress was monitored by TLC (hexanes: EtOAc; 30:1). After 24 h, the resulting slurry was filtered through Celite™ and concentrated to give a brown oil. The crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (hexanes: EtOAc; 30:1) to give the fluoro diaryl ether 9 as a yellow oil (280 mg, 83%). IR (ATR): 1526 s, 1497 s, 1473 s, 1352 s, 1212 s, 1187 s, 811 s, 734 s cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.93 (ddd, J = 8.2, 2.3, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (t, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H) 7.29 (ddd, J = 8.2, 2.3, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.13–7.08 (m, 2H), 7.07–7.02 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 159.8 (d, J = 242.4 Hz), 159.0, 151.3, 149.5, 130.5, 123.8, 121.7 (d, J = 8.4 Hz), 117.8, 117.1 (d, J = 23.2 Hz), 112.4. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3): δ −118.1. LRMS (APCI): m/z 234.1 [M + H]+ (100%), 204.1 [M − O2 + 2H]+ (32%), 188.1 [M − NO2]+ (24%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. for C12H10FNO3 [M + H]+: 234.0561, found: 234.0562.

3-(4-Fluorophenoxy)aniline (10b)

The m-aniline 10b was prepared following a procedure similar to that of Bavin et al. [43] Hydrazine monohydrate (790 mg, 0.77 mL, 16 mmol) was added to a deoxygenated mixture of the nitroarene 9 (0.50 g, 2.1 mmol), 10% Pd/C (50 mg) and EtOH (25 mL). This reaction mixture was then refluxed under N2 until TLC analysis (hexanes:EtOAc; 4:1) showed no starting material (typically 4 h). The reaction mixture was allowed to cool, filtered through Celite™, concentrated in vacuo and the colourless residue purified by column chromatography (hexanes: EtOAc; 4:1) to yield the m-aniline 10b as a colourless oil (410 mg, 95%). All spectral data was in accordance with that in the literature [44]. IR (ATR): 3462 s, 3317 s, 1619 m, 1584 m, 1485 s, 1282 m, 1193 s, 1141 s, 832 m, 772 m cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.08 (t, J = 8.0, 1H) 7.04–6.96 (m, 4H) 6.42 (ddd, J = 8.0, 2.2, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 6.35 (ddd, J = 8.0, 2.2, 0.8, 1H), 6.30 (t, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (bs, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.0, 158.7 (d, J = 239.8 Hz), 152.9, 148.2, 130.5, 120.8 (d, J = 8.3 Hz), 116.3 (d, J = 23.1 Hz), 110.1, 108.3, 105.0. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3): δ −120.5. LRMS (APCI): m/z 204.1 [M + H]+ (100%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. for C12H10FNO [M + H]+: 204.0819, found: 204.0820.

4-(3-Chloropropoxy)-N-(3-(4-fluorophenoxy)phenyl)benzamide (11b)

The alkyl chloride 11b was synthesised using a modified procedure outlined by Altin et al. [37]. A solution of 4-(3-chloropropoxy)benzoic acid [33,34] (910 mg, 4.24 mmol), in dry THF (50 mL) was stirred under N2 at at room temperature. Et3N (0.87 mL, 630 mg, 6.22 mmol), and DMAP (340 mg, 2.79 mmol) were then added to the reaction mixture, followed by EDC·HCl (867 mg, 4.53 mmol). After 15 min, a solution of the 3-(4-fluorophenoxy)aniline 10b (575 mg, 2.83 mmol) in dry DCM (20 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred under a N2 atmosphere at room temperature. After 48 hours the THF was removed in vacuo before being taken up into DCM (50 mL). The organic layer was then washed with NaHCO3 (3 × 50 mL), dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated to afford a light brown oil. Purification by column chromatography (hexanes: EtOAc; 7:2) yielded the alkyl chloride 11b as a colourless solid (917 mg, 81%). Mp: 116.5–117.0 °C. IR (ATR): 3366 s, 1652 s, 1601 s, 1528 m, 1500 s, 1442 s, 1267 m, 1246 s, 1196 s, 846 m, 773 s cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.82–7.89 (m, 2H), 7.75 (bs, 1H), 7.35–7.27 (m, 3H), 7.06–7.00 (m, 4H), 6.98–6.94 (m, 2H), 6.74 (dt, J = 7.2, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.18 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.76 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.27 (quin, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 165.2, 161.9, 159.1 (d, J = 240.4 Hz), 158.5, 152.7, 139.7, 130.3, 129.1, 127.3, 121.0 (d, J = 8.3 Hz), 116.5 (d, J = 23.0 Hz), 114.8, 144.7, 114.1, 110.2, 64.7, 41.4, 32.2. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3): δ −120.2. LRMS (APCI): m/z 400.1 [M + H]+ (100%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. for C22H20ClFNO3 [M + H]+: 400.1110, found: 400.1113.

4-(3-Azidopropoxy)-N-(3-(4-fluorophenoxy)phenyl)benzamide (12b)

The azide 12b was synthesised according to a procedure outlined by Alvarez et al. [41]. Sodium azide (219 mg, 3.38 mmol) was added to a solution of the alkyl chloride 11b (900 mg, 2.25 mmol) in DMSO (4 mL) and stirred under N2 at 70 °C. After 48 h, the reaction was allowed to cool and DCM (40 mL) was added. (CAUTION: It is recommended that DCM be substituted with diethyl ether for larger scale reactions, to avoid the formation of hazardous side products, such as azido-chloromethane and diazidomethane) The organic layer was washed with brine (5 × 100 mL), dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated to provide the azide 12b as a colourless solid (902 mg, 99%), which was deemed sufficiently pure by 1H NMR spectroscopy for use in the next step. Mp: 104.6–106.2 °C. IR (ATR): 3366 s, 2104 s, 1640 s, 1593 s, 1499 s, 1441 s, 1248 s, 1199 s, 848 m, 770 m cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.82–7.79 (m, 2H), 7.76 (bs, 1H), 7.35–7.27 (m, 3H), 7.06–7.00 (m, 4H), 6.97–6.93 (m, 2H), 6.74 (dt, J = 7.0, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 3.53 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.08 (quin, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 165.3, 161.9, 159.1 (d, J = 240.5 Hz), 158.6, 152.7, 139.7, 130.3, 129.1, 127.3, 121.0 (d, J = 8.4 Hz), 116.5 (d, J = 23.2 Hz), 114.8, 114.7, 114.2, 110.2, 65.0, 48.3, 28.9. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3): δ −120.2. LRMS (APCI): m/z 407.2 [M + H]+ (100%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. For C22H20FN4O3 [M + H]+: 407.1514, found: 407.1514.

4-(3-Aminopropoxy)-N-(3-(4-fluorophenoxy)phenyl)benzamide (5b)

A solution of the azide 12b (100 mg, 0.25 mmol), 10% Pd/C (12 mg) and hydrazine monohydrate (30 µL, 30 mg, 0.62 mmol) in MeOH (3 mL) were vigorously stirred under a N2 atmosphere at room temperature. After 20 mins, the reaction mixture was filtered through Celite™ and concentrated to provide the amino compound 5b as a colourless oil in a quantitative crude conversion. IR (ATR): 3280 br s, 1647 s, 1597 m, 1540 m), 1484 s, 1244 s, 1195 s, 837 s, 779 s, 760 s, 684 s cm−1.1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.90–7.87 (m, 2H), 7.45 (t, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (ddd, J = 8.0, 2.1, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.13–7.01 (m, 6H), 6.73 (ddd, J = 8.0, 2.1, 1.0 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.84 (br t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 1.96 (quin, 6.6 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 168.4, 163.5, 160.3 (d, J = 238.9 Hz), 159.5, 154.3, 141.6, 130.9, 130.6, 128.0, 121.9 (d, J = 8.3 Hz), 117.3 (d, J = 23.5 Hz), 116.7, 115.3, 114.9, 112.0, 67.3, 39.6, 33.0. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CD3OD): δ −120.5. LRMS (APCI): m/z 380.2 [M]+ (100%), 381.2 [M + H]+ (41%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. For C22H21FN2O3 [M]+: 380.1532, found: 380.1531.

N-(3-(4-Fluorophenoxy)phenyl)-4-(3-guanidinopropoxy)benzamide hydrochloride (6b)

The guanidinylated compound 6b was synthesised according to a modified procedure by Bernatowicz et al. [38]. The amine 5b (47 mg, 0.12 mmol), DIPEA (35 µL, 26 mg, 0.20 mmol), 1H-pyrazole-1-carboximidine hydrochloride 27 (25 mg, 0.17 mmol) and DMF (2 mL) were added to a flask and stirred vigorously under a nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature. After 18 h, the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield the guanidinylated compound 6b as a colourless solid in quantitative conversion. IR (ATR): 3244 br s, 3150 br s, 1651 s, 1592 s, 1503 s, 1479 s, 1249 s, 1210 m, 1171 s, 826 m, 791 m, 692 m cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.92–7.88 (m, 2H), 7.47 (t, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (ddd, J = 8.1, 2.2, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 7.30 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.11–7.01 (m, 6H), 6.72 (ddd, J = 8.1, 2.2, 0.9 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 3.42 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H), 2.09 (quin, J = 6.3 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): 168.3, 163.2, 160.3 (d, J = 239.0 Hz), 159.9, 158.8, 154.3, 141.6, 130.9, 130.7, 128.4, 121.9 (d, J = 8.4 Hz), 117.3 (d, J = 23.3 Hz), 116.7, 115.3, 115.0, 112.0, 66.3, 39.6, 29.6. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CD3OD): δ −120.5. LRMS (APCI): m/z 422.2 [M]+ (32%), 381.2 [M − CHN2]+ (35%), 380.2 [M − CH2N2]+ (100%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. For C23H23FN4O3 [M]+: 422.1749, found: 422.1749.

4-(3-Chloropropoxy)-N-(4-(4-fluorophenoxy)phenyl)benzamide (11c)

4-(3-Chloropropoxy)benzoic acid (790 mg, 3.68 mmol) was taken up into SOCl2 (2.00 mL, 3.28 g, 27.5 mmol) and the reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min. Excess SOCl2 was removed under a stream of N2 to provide an acid chloride intermediate. A solution of 4-(4-fluorophenoxy)aniline 10c (650 mg, 3.20 mmol) in dry THF (35 mL) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 18 h. The THF was removed in vacuo, and the resultant solid was taken up into EtOAc (60 mL) and washed with sat. NaHCO3 (3 × 100 mL). The organic layer was dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated to afford the crude alkyl chloride 11c as a brown solid. The solid was recrystallised from hot EtOAc to give the desired alkyl chloride 11c as a colourless solid (900 mg, 70%). Mp: 147.3–148.1 °C. IR (ATR): 3338 s, 1642 s, 1607 m, 1496 s, 1259 s, 852 s, 833 s, 816 s, 761 s cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.88–7.84 (m, 2H), 7.71 (br s, 1H), 7.61–7.58 (m, 2H), 7.07–6.97 (m, 8H), 4.22 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.79 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.30 (quin, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 165.3, 161.9, 158.9‡ (d, J = 239.7 Hz), 154.2, 153.4‡, 133.7, 129.1, 127.4, 122.2, 120.2 (d, J = 8.2 Hz), 119.3, 116.4 (d, J = 23.1 Hz), 114.7, 64.7, 41.5, 32.2. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3): δ −120.8. LRMS (APCI): m/z 400.1 [M + H]+ (75%), 399.1 [M]+ (100%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. for C22H19ClFNO3 [M]+: 399.1032, found: 399.1032.

4-(3-Azidopropoxy)-N-(4-(4-fluorophenoxy)phenyl)benzamide (12c)

The azide 12c was synthesised according to a procedure outlined by Alvarez et al. [41]. Sodium azide (63 mg, 0.97 mmol) was added to a solution of the alkyl chloride 11c (300 mg, 0.752 mmol) in DMSO (4 mL) and stirred under N2 at 70 °C. After 48 h, the reaction mixture was cooled and DCM (40 mL) was added. (CAUTION: It is recommended that DCM be substituted with diethyl ether for larger scale reactions, to avoid the formation of hazardous side products, such as azido-chloromethane and diazidomethane) The organic layer was washed with brine (5 × 100 mL), dried with Na2SO4 and concentrated to provide the azide 12c as a colourless solid (279 mg, 92%), which was deemed sufficiently pure by 1H NMR spectroscopy for use in the next step. Mp: 120.7–122.0 °C. IR (ATR): 3325 s, 2099 s, 1648 s, 1605 m, 1494 s, 1250 s, 1208 s, 828 s, 764 m cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.86–7.82 (m, 2H), 7.68 (br s, 1H), 7.60–7.56 (m, 2H), 7.05–6.95 (m, 8H), 4.13 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 3.54 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 2.09 (quin, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 165.3, 161.8, 158.8‡ (d, J = 261.0 Hz), 154.3, 153.4‡, 133.7, 129.1, 127.4, 122.2, 120.2 (d, J = 8.3 Hz), 119.3, 116.4 (d, J = 23.2 Hz), 114.7, 65.0, 48.3, 28.9. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3): δ −120.8. LRMS (APCI): m/z 406.1 [M]+ (100%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. for C22H19FN4O3 [M]+: 406.1436, found: 406.1438.

4-(3-Aminopropoxy)-N-(4-(4-fluorophenoxy)phenyl)benzamide (5c)

A solution of the azide 11c (100 mg, 0.25 mmol), 10% Pd/C (12 mg) and hydrazine monohydrate (30 µL, 30 mg, 0.62 mmol) in MeOH (3 mL) were vigorously stirred under a N2 atmosphere at room temperature. After 20 mins, the reaction mixture was filtered through Celite™ and concentrated to provide the amino compound 5c as a yellow oil in a quantitative crude conversion. IR (ATR): 3307 m, 3282 m, 1632 s, 1606 m, 1494 s, 1248 m, 1208 s, 820 s, 758 s cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.92–7.89 (m, 2H), 7.66–7.62 (m, 2H), 7.10–6.95 (m, 8H), 4.14 (t, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H), 2.84 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.00–1.93 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD): δ 168.3, 163.5, 160.1 (d, J = 238.7 Hz), 155.5, 154.9, 135.5, 130.5, 128.1, 124.2, 121.2 (d, J = 8.1 Hz), 119.8, 117.2 (d, J = 23.3 Hz), 115.3, 67.3, 39.6, 33.3. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CD3OD): δ −121.0. LRMS (APCI): m/z 381.2 [M + H]+ (28%), 380.2 [M + H]+ (100%), 323.1 [M − C3H7N]+ (34%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. for C22H21FN2O3 [M]+: 380.1531, found: 380.1533.

N-(4-(4-Fluorophenoxy)phenyl)-4-(3-guanidinopropoxy)benzamide hydrochloride (6c)

The guanidinylated compound 6c was synthesised according to a modified procedure by Bernatowicz et al. [38]. The amine 5c (47 mg, 0.12 mmol), DIPEA (35 µL, 26 mg, 0.20 mmol), 1H-pyrazole-1-carboximidine hydrochloride (25 mg, 0.17 mmol) and DMF (2 mL) were added to a flask and stirred vigorously under a nitrogen atmosphere at room temperature. After 18 h, the solvent was removed in vacuo to yield the guanidinylated compound 6c as a yellow oil with quantitative conversion. IR (ATR): 3272 m, 3185 m, 1631 s, 1601 s, 1495 s, 1437 s, 1393 s, 1247 s, 1208 s, 1177 s, 839 m, 759 m. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD3OD): δ 7.94–7.92 (m, 2H), 7.65–7.63 (m, 2H), 7.10–6.99 (m, 6H), 6.98–6.95 (m, 2H), 4.16 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H), 3.43 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 2H), 2.13–2.07 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (150 MHz, CD3OD): δ 168.2, 163.1, 159.5 (d, J = 240.9 Hz), 158.7, 155.5, 154.9, 135.4, 130.6, 128.3, 124.2, 121.2 (d, J = 8.0 Hz), 119.8, 117.2 (d, J = 24.1 Hz), 115.3, 66.3, 39.5, 29.6. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CD3OD): δ −120.9. LRMS (APCI): m/z 422.2 [M]+ (14%), 381.2 [M − CN2H] + (30%), 380.2 [M − CH2N2]+ (100%), 323.1 [M-C3H9N3]+ (31%). HRMS (APCI): m/z calcd. for C23H23FN4O3 [M]+: 422.1749, found: 422.1750.

3.2. Biology

Fluorescence Measurement of Calcium Responses

SH-SY5Y cells were plated at a density of 30,000–50,000 cells/well on 384-well black-walled imaging plates and loaded for 30 min at 37 °C with Calcium 4 no-wash dye (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) diluted in physiological salt solution (PSS; composition: 140 mM NaCl, 11.5 mM glucose, 5.9 mM KCl, 1.4 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM NaH2PO4, 5 mM NaHCO3, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), pH 7.4). Calcium responses, elicited by addition of 90 mM KCl and 5 mM CaCl2 in the presence of 10 µM nifedipine, were measured using a FLIPRTETRA fluorescent plate reader (excitation, 470–495 nm; emission, 515–575 nm) after 5 min pre-treatment with test compounds. Fluorescent responses were plotted as response over baseline using ScreenWorks (Molecular Devices, version 3.1.1.4). Concentration-response curves of Calcium responses, normalized to control responses, were generated using GraphPad Prism (Version 4.00, San Diego, CA, USA) using a 4-parameter Hill equation with variable Hill slope and bottom >0 fitted to the data.

4. Conclusions

Despite being significantly less complex than the originally designed anthranilamide ω-conotoxin GVIA mimetics (e.g., 2), the simplified fluorophenoxyanilides described here (5a–c and 6a–c) show enhanced activity in the SH-SY5Y FLIPR assay. The compounds with para-substitution around the central ring (5c and 6c) were found to have the weakest activity, suggesting that some type of pre-organisation through restricted rotation might enhance the activity of the ortho and meta analogues (5a, 5b, 6a and 6b). It is also unusual for the amines to be more active than the guanidines in this class of channel blocker. While primary amines typically do not make good drugs, this observation does open the possibility of developing N-type channel blockers capable of crossing the blood brain barrier. Compounds bearing very strongly basic functional groups like guanidine are unlikely to cross the blood brain barrier [45] whereas there are many CNS-active drugs that bear tertiary amines. The mode of action of the compounds reported here is currently being investigated in patch clamp electrophysiology experiments, the results of which will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

The Monash-CSIRO Collaborative Research Support Scheme, Monash University and CSIRO are acknowledged for funding, as well as Monash University for providing J.E.G., with a Monash Graduate Scholarship and CSIRO for providing J.E.G., a scholarship top-up. This work was also supported by a NHMRC Program Grant (569927), NHMRC Australian Biomedical Postdoctoral Fellowship (569918, IV) and NHMRC Fellowship (APP1019761, RJL).

Author Contributions

E.C.G. synthesised compounds 5a–c and 6a–c, J.E.G contributed to the initial synthetic strategy for compounds 5a and 6a, S.S. synthesised compound 6a, I.V. performed the FLIPR experiments and assisted with drafting of the manuscript, R.J.L. assisted with the FLIPR experiments and with drafting of manuscript, P.J.D. jointly conducted the channel blocker development, synthetic design, drafting of manuscript, K.L.T. jointly conducted the channel blocker development, synthetic design, drafting of manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Vink S., Alewood P.F. Targeting voltage-gated calcium channels: Developments in peptide and small-molecule inhibitors for the treatment of neuropathic pain. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;167:970–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altier C., Zamponi G.W. Targeting Ca2+ channels to treat pain: T-type versus N-type. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;25:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee M.S. Chapter four—Recent progress in the discovery and development of N-type calcium channel modulators for the treatment of pain. In: Lawton G., Witty D.R., editors. Progress in Medicinal Chemistry. Volume 53. Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 2014. pp. 147–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perret D., Luo Z.D. Targeting voltage-gated calcium channels for neuropathic pain management. NeuroRX. 2009;6:679–692. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pope J.E., Deer T.R. Ziconotide: A clinical update and pharmacologic review. Exp. Opin. Pharmacother. 2013;14:957–966. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.784269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bear B., Asgian J., Termin A., Zimmermann N. Small molecules targeting sodium and calcium channels for neuropathic pain. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 2009;12:543–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto T., Takahara A. Recent updates of N-type calcium channel blockers with therapeutic potential for neuropathic pain and stroke. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2009;9:377–395. doi: 10.2174/156802609788317838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamponi G.W., Feng Z.-P., Zhang L., Pajouhesh H., Ding Y., Belardetti F., Pajouhesh H., Dolphin D., Mitscher L.A., Snutch T.P. Scaffold-based design and synthesis of potent N-type calcium channel blockers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:6467–6472. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abbadie C., McManus O.B., Sun S.-Y., Bugianesi R.M., Dai G., Haedo R.J., Herrington J.B., Kaczorowski G.J., Smith M.M., Swensen A.M., et al. Analgesic effects of a substituted N-triazole oxindole (Trox-1), a state-dependent, voltage-gated calcium channel 2 blocker. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010;334:545–555. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.166363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pajouhesh H., Feng Z.-P., Ding Y., Zhang L., Pajouhesh H., Morrison J.-L., Belardetti F., Tringham E., Simonson E., Vanderah T.W., et al. Structure-activity relationships of diphenylpiperazine N-type calcium channel inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:1378–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyagarajan S., Chakravarty P.K., Park M., Zhou B., Herrington J.B., Ratliff K., Bugianesi R.M., Williams B., Haedo R.J., Swensen A.M., et al. A potent and selective indole N-type calcium channel (Cav2.2) blocker for the treatment of pain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:869–873. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto T., Ohno S., Niwa S., Tokumasu M., Hagihara M., Koganei H., Fujita S.-I., Takeda T., Saitou Y., Iwayama S., et al. Asymmetric synthesis and biological evaluations of (+)- and (−)-6-dimethoxymethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3-carboxylic acid derivatives blocking N-type calcium channels. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:3317–3319. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beebe X., Darczak D., Henry R.F., Vortherms T., Janis R., Namovic M., Donnelly-Roberts D., Kage K.L., Surowy C., Milicic I., et al. Synthesis and SAR of 4-aminocyclopentapyrrolidines as N-type Ca2+ channel blockers with analgesic activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:4128–4139. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott V.E., Vortherms T.A., Niforatos W., Swensen A.M., Neelands T., Milicic I., Banfor P.N., King A., Zhong C., Simler G., et al. A-1048400 is a novel, orally active, state-dependent neuronal calcium channel blocker that produces dose-dependent antinociception without altering hemodynamic function in rats. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012;83:406–418. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subasinghe N.L., Wall M.J., Winters M.P., Qin N., Lubin M.L., Finley M.F.A., Brandt M.R., Neeper M.P., Schneider C.R., Colburn R.W., et al. A novel series of pyrazolylpiperidine N-type calcium channel blockers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:4080–4083. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shao P.P., Ye F., Chakravarty P.K., Varughese D.J., Herrington J.B., Dai G., Bugianesi R.M., Haedo R.J., Swensen A.M., Warren V.A., et al. Aminopiperidine sulfonamide Cav2.2 channel inhibitors for the treatment of chronic pain. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:9847–9855. doi: 10.1021/jm301056k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pajouhesh H., Feng Z.-P., Zhang L., Pajouhesh H., Jiang X., Hendricson A., Dong H., Tringham E., Ding Y., Vanderah T.W., et al. Structure-activity relationships of trimethoxybenzyl piperazine N-type calcium channel inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:4153–4158. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.04.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beebe X., Yeung C.M., Darczak D., Shekhar S., Vortherms T.A., Miller L., Milicic I., Swensen A.M., Zhu C.Z., Banfor P., et al. Synthesis and SAR of 4-aminocyclopentapyrrolidines as orally active N-type calcium channel inhibitors for inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:4857–4861. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.06.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borzenko A., Pajouhesh H., Morrison J.-L., Tringham E., Snutch T.P., Schafer L.L. Modular, efficient synthesis of asymmetrically substituted piperazine scaffolds as potent calcium channel blockers. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:3257–3261. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shao P.P., Ye F., Chakravarty P.K., Herrington J.B., Dai G., Bugianesi R.M., Haedo R.J., Swensen A.M., Warren V.A., Smith M.M., et al. Improved Cav2.2 channel inhibitors through a gem-dimethylsulfone bioisostere replacement of a labile sulfonamide. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:1064–1068. doi: 10.1021/ml4002612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu J., Chu K.L., Zhu C.Z., Niforatos W., Swensen A., Searle X., Lee L., Jarvis M.F., McGaraughty S. A mixed Ca2+ channel blocker, A-1264087, utilizes peripheral and spinal mechanisms to inhibit spinal nociceptive transmission in a rat model of neuropathic pain. J. Neurophysiol. 2014;111:394–404. doi: 10.1152/jn.00463.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhu C.Z., Vortherms T.A., Zhang M., Xu J., Swensen A.M., Niforatos W., Neelands T., Milicic I., Lewis L.G., Zhong C., et al. Mechanistic insights into the analgesic efficacy of A-1264087, a novel neuronal Ca2+ channel blocker that reduces nociception in rat preclinical pain models. J. Pain. 2014;15:387.e1–387.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.01.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mollica A., Costante R., Novellino E., Stefanucci A., Pieretti S., Zador F., Samavati R., Borsodi A., Benyhe S., Vetter I., et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of two opioid agonist and Cav2.2 blocker multitarget ligands. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2014 doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duggan P.J., Faber J.M., Graham J.E., Lewis R.J., Lumsden N.G., Tuck K.L. Synthesis and Cav2.2 binding data for non-peptide mimetics of ω-conotoxin GVIA based on a 5-amino-anthranilamide core. Aust. J. Chem. 2008;61:11–15. doi: 10.1071/CH07327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersson A., Baell J.B., Duggan P.J., Graham J.E., Lewis R.J., Lumsden N.G., Tranberg C.E., Tuck K.L., Yang A. ω-Conotoxin GVIA mimetics based on an anthranilamide core: Effect of variation in ammonium side chain lengths and incorporation of fluorine. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:6659–6670. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baell J.B., Duggan P.J., Forsyth S.A., Lewis R.J., Lok Y.P., Schroeder C.I. Synthesis and biological evaluation of nonpeptide mimetics of ω-conotoxin GVIA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:4025–4037. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baell J.B., Duggan P.J., Forsyth S.A., Lewis R.J., Lok Y.P., Schroeder C.I., Shepherd N.E. Synthesis and biological evaluation of anthranilamide-based non-peptide mimetics of ω-conotoxin GVIA. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:7284–7292. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.05.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duggan P.J., Lewis R.J., Lok Y.P., Lumsden N.G., Tuck K.L., Yang A. Low molecular weight non-peptide mimics of ω-conotoxin GVIA. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:2763–2765. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.03.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tranberg C.E., Yang A., Vetter I., McArthur J.R., Baell J.B., Lewis R.J., Tuck K.L., Duggan P.J. ω-Conotoxin GVIA mimetics that bind and inhibit neuronal Cav2.2 ion channels. Mar. Drugs. 2012;10:2349–2368. doi: 10.3390/md10102349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Press release investors and media—zalicus. [(accessed on 30 January 2015)]. Available online: http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=148036&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=1874737&highlight=

- 31.Lauri G., Bartlett P. Caveat: A program to facilitate the design of organic molecules. J. Comput. -Aided. Mol. Des. 1994;8:51–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00124349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baell J., Forsyth S., Gable R., Norton R., Mulder R. Design and synthesis of type-III mimetics of ω-conotoxin GVIA. J. Comput. -Aided. Mol. Des. 2001;15:1119–1136. doi: 10.1023/A:1015930031890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aguilar M.-I., Purcell A.W., Devi R., Lew R., Rossjohn J., Smith A.I., Perlmutter P. β-amino acid-containing hybrid peptides-new opportunities in peptidomimetics. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007;5:2884–2890. doi: 10.1039/b708507a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wen F., Zhang H., Yu Z., Jin H., Yang Q., Hou T. Design, synthesis and antifungal/insecticidal evaluation of novel nicotinamide derivatives. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2010;98:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2010.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertrand I., Capet M., Lecomte J.-M., Levoin N., Ligneau X., Poupardin-Olivier O., Robert P., Schwartz J.-C., Labeeuw O. Preparation of pyrrolidinyl- and piperidinylpropoxyarenes as histamine H3 receptor ligands. WO2006117609 A2. France: 2006 Nov 9;

- 36.Genzer J.D., Huttrer C.P., Wessem G.C.V. Phenoxy- and benzyloxyalkyl thiocyanates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1951;73:3159–3162. doi: 10.1021/ja01151a047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Altin J.G., Banwell M.G., Coghlan P.A., Easton C.J., Nairn M.R., Offermann D.A. Synthesis of NTA3-DTDA—A chelator-lipid that promotes stable binding of His-tagged proteins to membranes. Aust. J. Chem. 2006;59:302–306. doi: 10.1071/CH06112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernatowicz M.S., Wu Y., Matsueda G.R. 1H-Pyrazole-1-carboxamidine hydrochloride an attractive reagent for guanylation of amines and its application to peptide synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 1992;57:2497–2502. doi: 10.1021/jo00034a059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sousa S.R., Vetter I., Ragnarsson L., Lewis R.J. Expression and pharmacology of endogenous Cav channels in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e59293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McArthur J.R., Adams D.J. (RMIT University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia). Personal Communication. 2015. The SH-SY5Y FLIPR assay has previously been shown to be a good predictor of Cav activity in other functional assays such as whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology measurements. Correspondingly, compound 6a was tested for its ability to block calcium currents in HEK293 cells stably expressing human Cav2.2 channels, giving an IC50 of 36.3 ± 2.4 µM (n = 4–7)

- 41.Alvarez S.G., Alvarez M.T. A practical procedure for the synthesis of alkyl azides at ambient temperature in dimethyl sulfoxide in high purity and yield. Synthesis. 1997;1997:413–414. doi: 10.1055/s-1997-1206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans D.A., Katz J.L., West T.R. Synthesis of diaryl ethers through the copper-promoted arylation of phenols with arylboronic acids. An expedient synthesis of thyroxine. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:2937–2940. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(98)00502-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bavin P.M.G. The preparation of amines and hydrozo compounds using hydrazine and palladized charcoal. Can. J. Chem. 1958;36:238–241. doi: 10.1139/v58-032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maiti D., Buchwald S.L. Orthogonal Cu- and Pd-based catalyst systems for the O- and N-arylation of aminophenols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17423–17429. doi: 10.1021/ja9081815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pajouhesh H., Lenz G. Medicinal chemical properties of successful central nervous system drugs. Neurotherapeutics. 2005;2:541–553. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.4.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]