Abstract

Peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor (PPAR) gene family members exhibit distinct patterns of distribution in tissues and differ in functions. The purpose of this study is to investigate the evolutionary impacts on diversity functions of PPAR members and the regulatory differences on gene expression patterns. 63 homology sequences of PPAR genes from 31 species were collected and analyzed. The results showed that three isolated types of PPAR gene family may emerge from twice times of gene duplication events. The conserved domains of HOLI (ligand binding domain of hormone receptors) domain and ZnF_C4 (C4 zinc finger in nuclear in hormone receptors) are essential for keeping basic roles of PPAR gene family, and the variant domains of LCRs may be responsible for their divergence in functions. The positive selection sites in HOLI domain are benefit for PPARs to evolve towards diversity functions. The evolutionary variants in the promoter regions and 3′ UTR regions of PPARs result into differential transcription factors and miRNAs involved in regulating PPAR members, which may eventually affect their expressions and tissues distributions. These results indicate that gene duplication event, selection pressure on HOLI domain, and the variants on promoter and 3′ UTR are essential for PPARs evolution and diversity functions acquired.

1. Introduction

Peroxisome proliferators-activated receptors (PPARs) are transcription factors belonging to the ligand-activated nuclear receptor superfamily, which play key roles in regulating metabolism, inflammation, and immunity. In vertebrates, the gene family of PPAR consisted of PPARα, PPARβ (also called PPARb/d or PPARδ), and PPARγ [1]. Recently, a considerable number of papers have reviewed their importance in functions within various physiological and biochemistry processes [2–5]. Their special effects and functional manners of depending on a ligand-activated way even have attracted some scientists to consider them as a drug target for therapy of some metabolic disorders, such as the type 2 diabetes mellitus and atherosclerosis [6].

It has been well established that the PPARs can be divided into five distinct functional regions, which include DBD (DNA-binding domain), LBD (ligand-binding domain), AF1 (activation function 1), AF2 (activation function 2), and a variable hinge region. The DBD and LBD consist of a highly conserved DNA-binding domain and a moderately conserved ligand-binding domain, respectively. The AF1 and AF2 are two ligand-independent activation function domains. All these regions except the variable hinge region are highly conserved among PPAR members and are responsible for keeping their functions [3]. Although the PPARs share high similarities with each other in structures, they exhibit distinct patterns of distribution in tissues and differ in functions [7]. It has been summarized that PPARα mainly is involved in the oxidation process of hepatocytes, PPARβ mainly targets within the adipocyte proliferation, and PPARγ plays essential roles in origination and fate determination of preadipocyte. In adult rat, it has shown that PPARs had different expression patterns [8]. Definitely, PPARα is highly expressed in hepatocytes, cardiomyocytes, enterocytes, and the proximal tubule cells of kidney, PPARβ is expressed ubiquitously and often at higher levels than PPARα and PPARγ, and PPARγ is expressed predominantly in adipose tissue and the immune tissues [4].

It is interesting to investigate why PPARs exhibit distinct patterns of distribution in tissues and differ in functions even if they share high similarity of regions. There may be at least two main aspects of molecular reasons accounting for their differences. Firstly, it could be explained by the molecular evolutionary process, for example, the gene duplication event and the selective patterns. PPAR gene family as one of the nuclear hormone receptor (NHR) superfamilies evolves together with other NHR members. It has been demonstrated that a large number of NHR members are likely to result from two waves of gene duplication events. The first wave occurs before the arthropod/vertebrate divergence and has generated the ancestors of the NHR subfamilies, for instance, PPARs, RARs, and RXRs. The second wave of duplication is vertebrate-specific and leads to a diversification inside the subfamilies, with the emergence of the presently known isotypes such as PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ [3, 7]. However, it is still unknown which one is the common ancestor gene in PPAR members, and what the impacts of PPARs divergence on their functions are. Secondly, the special transcriptions factors binging in the promoter regions and the miRNAs target at 3′ UTRs of PPARs may be responsible for the distinct patterns of distribution in tissues. Numerous reports have established the basis for gene expression patterns in distribution by predicting and comprising the transcription factors and miRNAs of interested genes [9].

Therefore, in this present study, we took advantage of the availability of gene sequence data to analyze the PPAR gene family based on a view of molecular evolutionary relationship by deducing the possibility of evolution in PPAR gene family, as well as by predicting and comparing their transcription factors and miRNAs to primarily understand the reasons for diversity functions and distinct patterns of expressions in tissues of PPAR members. These analyses may contribute to a comprehensive understanding for the functions of PPAR gene family.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PPAR Gene Homology Sequence Collection

The Genomic Blast function (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) was used for collecting homologous sequences of PPAR gene family members in species. The parameters were set as the default value. For the minority of the PPAR gene sequences unfound by blast, we separated supplement in the website of Nucleotide database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/) by manually using keywords. Through blasting the homology sequences of PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ on NCBI, we finally obtained 63 homology sequences that belong to 31 species (Table S1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/613910). Most of these sequences were from mammals, and a few of them were obtained from fish and birds. These collected sequences were edited and aligned by the MegAlign in DNAStar (Madison, Wisconsin, USA).

2.2. Search for Protein Domains

The open reading frames (ORF) of PPAR sequences in different species were predicted using online software (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/orfig.cgi). Next, these ORF sequences were confirmed by Pfam (http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/). Only if there were homology amino acid sequences blasted, Pfam would show the ORF sequences being correctly predicted. Furthermore, the correct amino acid sequences were entered into SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) platform for a prediction of protein structure domain.

2.3. Construction of Phylogenetic Tree

The format of each PPAR homologous protein sequence was edited by BioEdit software [10]. Then, the protein sequences were used for constructing phylogenetic tree through a model of maximum likelihood method (ML) by Mega 5.1 [11]. The topological stability of the maximum likelihood tree was evaluated by 1000 bootstrap replications. The Atlantic salmon PPARγ protein sequence (NM_001123546.1) was selected as the outgroup of the protein phylogenetic tree.

2.4. Amino Acid Site Selection Pressure Analysis

The sequences of two conserved protein domains (ZnF_C4 and HOLI domains) were chosen and compared by BioEdit, and then they were classified and merged. According to the analysis of Bayesian tree phylogeny, we used the site model in PAML software package in Codeml program [12] to analyze these two domains.

The site model was constructed to test whether PPAR gene is subjected to positive selection (ω > 1) or negative selection (ω < 1) [13]. This model allows different sites to have different selection pressure, while there is no difference in different branches of the phylogenetic tree. The models named M1a (neutral) and M2a (selection) [13, 14] in the current study were used twice the log-likelihood difference (2ΔL) following χ 2 distribution of likelihood ratio test (LRT), the difference degree of freedom for the two parameters of the model number.

2.5. Analysis of Transcription Factors

By using Gene (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/) of the NCBI, the location of the PPAR gene was determined on the chromosome corresponding species. And then, we confirmed the first exon of the PPAR gene transcription initiation site on a chromosome. Sequence about 1000 bp was selected to use as the predicted promoter regions from the upstream of the first exon. On the TRANSFAC, the Alibaba (http://www.gene-regulation.com/pub/programs/alibaba2/index.html) can estimate transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) in unknown DNA sequences.

2.6. Predictions of miRNAs in 3′ UTR Region of PPAR Members

The miRNAs in 3′ UTR region of PPAR members and their regulatory sites were predicted by TargetScan release (http://www.targetscan.org/). In the TargetScan, the 3′ UTR region of PPAR members of human was searched for miRNAs. The search results were sorted in the miR2Disease Base (http://www.mir2disease.org/) for predicting functions of the predicted conservative miRNAs.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. The Unique Homology and Conserved Domains in PPAR Gene Family

As it was shown in Table S1, the coding regions of all PPAR nucleotides were in average length of about 1400 bp, which encode about 466 amino acids. The average length of nucleotides of PPARα coding domain is 1406 bp, whereas the average length of nucleotides of PPARβ is 1284 bp which is lower than the average value of the entire PPAR family. The nucleotide of PPARγ is 1479 bp which is obviously higher than the average value.

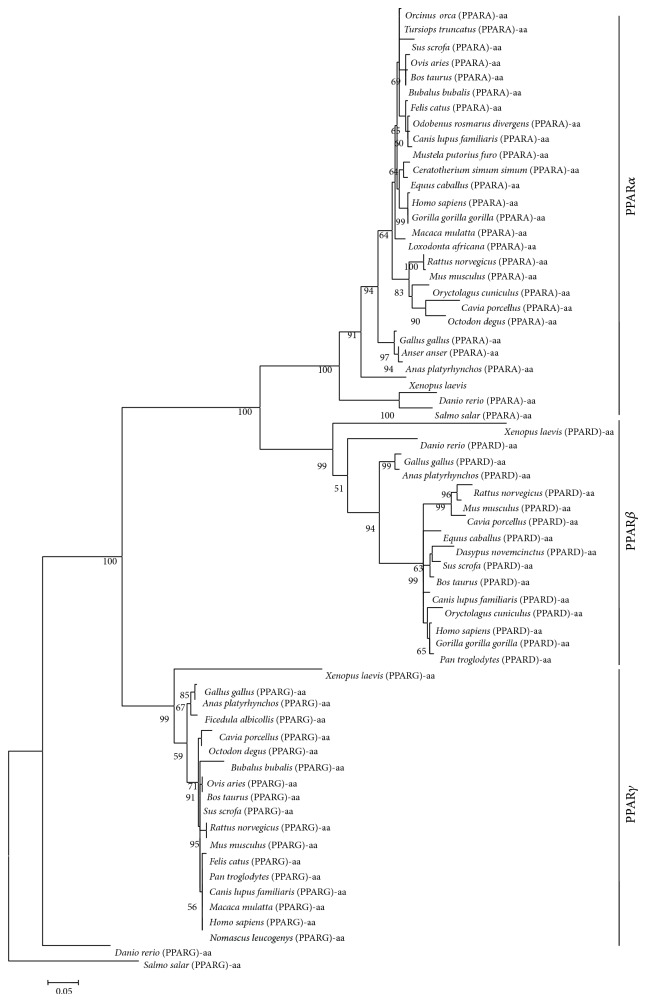

The protein domains were predicted corresponding to each sequence in the coding region through SMART. The PPAR coding domain sequences in 7 representative species including human, xenopus, zebrafish, chicken, dog, pig, and mouse were obtained for a further analysis (Figure 1). The data demonstrated that all PPARs family members contained the ZnF_C4 and HOLI domains, which are conserved among species. In addition to the conserved domains, low complexity 1 and low complexity 2 regions (LCRs) were in great differences among PPAR members and species. In PPARα, it was found that LCR2 widely existed in most species, and LCR1 only existed in mice. It is also worth noticing that more than half of the studied species contained the LCRs domains in PPARβ, except for the absence of LCR2 in xenopus. In PPARγ, the LCR2 domain was only found in zebrafish, whereas the LCR1 domain was absent in all studied species.

Figure 1.

The protein domains of PPARs were predicted in 7 representative species. A box represents a conserved domain. The numerals labeled in the boxes and lines represent the number of amino acid residues. The PPARs coding domain sequences were collected in 7 representative species including human, xenopus, zebrafish, chicken, dog, pig, and mouse.

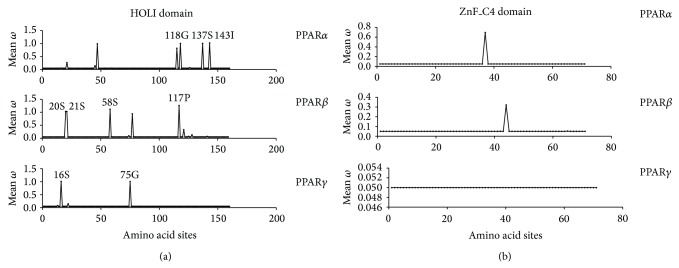

3.2. The Phylogenetic Tree of PPAR Gene Family

In order to investigate the homologous relationships among PPAR gene family members, we constructed phylogenetic tree based on the amino acid level. The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the 63 amino acid sequences from 31 species (Table S1), and the results were shown in Figure 2. The orthologs of PPAR members from fishes were placed at the base of the three branches of the tree. Furthermore, the PPAR genes were spitted into three lineages (support value = 100%). Through the branches and distances of the phylogenetic tree, PPARα and PPARβ were clustered together. The branch of PPARγ stood alone and was closer to the outgroup than the other two branches. PPARγ might be the earliest ancestor form of the PPAR gene family. According to the classification, it suggested that the first independent duplication event may occur in bony fishes before separation from the birds and mammals during the whole evolutionary process of PPAR gene family. And after a second duplication event, the isolated types of PPARα and PPARβ may emerge as the paralogs of PPARγ.

Figure 2.

The phylogenetic tree based amino acid sequences. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by amino acid sequences. The sequences information was provided in Table S1. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the maximum likelihood method with Mega 5.1. The numbers on nodes indicate the support values. It showed the bootstrap values were more than 50%.

3.3. Selection Pressure of Amino Acid Residues in PPAR Gene

To determine the selection states of each amino acid site in conserved structure of PPARs during the evolution process, the tools of selective pressure were used for investigating the different selection patterns based on the conserved motifs of ZnF_C4 domain and HOLI domain, which were widely included and conserved in PPAR gene family. In branch-site models (Table 1), we found the estimated ω value ≥ 1 with the M2a model for HOLI domain and ZnF_C4 domain. It suggests that PPAR genes were under positive selection. By the LRT test, M1a and M2a were compared with their corresponding null models (M0), respectively. The results suggested that M2a (P < 0.05) was more in coincidence with the data than M1a (P > 0.05). What is more, the LRT tests of all PPAR members were different. The HOLI domain could be accepted by M2a, indicating a positive selection pressure of HOLI domain during the molecular evolution process, whereas the ZnF_C4 domain was rejected.

Table 1.

Selection pressure analysis of amino acid sites in PPARs.

| Model | lnL | Parameters estimates | 2ΔL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 0 | |||

| α-HOLI | −4720.995579 | ||

| β-HOLI | −2960.312353 | ||

| γ-HOLI | −2719.120808 | ||

| α-ZnF_C4 | −1050.374116 | ||

| β-ZnF_C4 | −1033.465323 | ||

| γ-ZnF_C4 | −1276.57302 | ||

| Model 1a | |||

| α-HOLI | −4622.51301 | P0 = 0.93383, P1 = 0.06617 | |

| ω0 = 0.01746, ω1 = 1.00000 | |||

| β-HOLI | −2894.97063 | P0 = 0.94599, P1 = 0.05401 | |

| ω0 = 0.02167, ω1 = 1.00000 | |||

| γ-HOLI | −2689.49404 | P0 = 0.97407, P1 = 0.02593 | |

| ω0 = 0.00539, ω1 = 1.00000 | |||

| α-ZnF_C4 | −1062.29037 | P0 = 0.98590, P1 = 0.01410 | |

| ω0 = 0.00862, ω1 = 1.00000 | |||

| β-ZnF_C4 | −1027.39487 | P0 = 0.97625, P1 = 0.02375 | |

| ω0 = 0.00722, ω1 = 1.00000 | |||

| γ-ZnF_C4 | −1276.57373 | P0 = 0.99999, P1 = 0.00001 | |

| ω0 = 0.00168, ω1 = 1.00000 | |||

| Model 2a | |||

| α-HOLI | −4622.51301 | P0 = 0.93383, P1 = 0.03245, P2 = 0.03372 | 196.96513 |

| ω0 = 0.01746, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2 = 1.00000 | |||

| β-HOLI | −2894.97063 | P0 = 0.94599, P1 = 0.04003, P2 = 0.01398 | 130.683442 |

| ω0 = 0.02167, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2 = 1.00000 | |||

| γ-HOLI | −2689.49404 | P0 = 0.97407, P1 = 0.00429, P2 = 0.02163 | 59.253532 |

| ω0 = 0.00539, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2 = 1.00000 | |||

| α-ZnF_C4 | −1044.04256 | P0 = 0.98590, P1 = 0.01410, P2 = 0.00000 | 12.66312 |

| ω0 = 0.00737, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2 = 6.14876 | |||

| β-ZnF_C4 | −1027.39487 | P0 = 0.97625, P1 = 0.00871, P2 = 0.01504 | 12.140902 |

| ω0 = 0.00722, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2 = 1.00000 | |||

| γ-ZnF_C4 | −1276.57302 | P0 = 1.00000, P1 = 0.00000, P2 = 0.00000 | 0.000004 |

| ω0 = 0.00168, ω1 = 1.00000, ω2 = 1.00000 |

Note: selection pressure on amino acid sites of the inspection is based on the calculation of dN/dS (ω), where dN is nonsynonymous coding sequences of each base mutation rate (nonsynonymous substitution rate) and dS is a synonymous mutation rate (synonymous substitution rate). When the ω > 1, the gene is by positive selection; ω = 1, no selection pressure; ω < 1, by purifying selection.

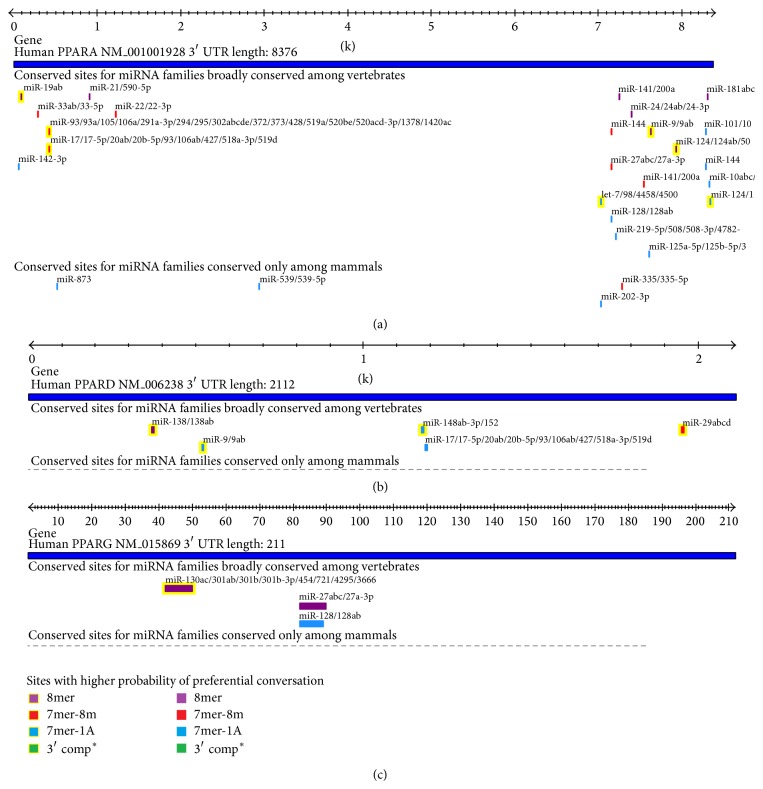

In a 95% posterior probability, the results (Figures 3(a) and 3(b)) showed that the positive selection sites in PPARα HOLI domain were 118G, 137S, and 143I, in PPARβ HOLI domain 20S, 21S, 58S, and 117P, and in PPARγ HOLI domain 16S and 75G, whereas in the ZnF_C4 domain, there were no positive selection sites observed in all PPAR members, except for only one suspected amino acid residue with ω value between 0.5 and 1 observed in ZnF_C4 domain of PPARα and PPARβ, respectively. In PPARγ ZnF_C4 domain, there were no positive selection sites observed either.

Figure 3.

Approximate posterior mean of amino acid sites. There was a list of amino acids in each sequence of the corresponding ω value. The amino acid residue marked on the image represents the ω > 1 with probability of more than 95%.

3.4. Prediction of Transcription Factors

The transcription factors and their binding sites in promoter regions of PPAR gene family were predicted in human and chicken, respectively, and the results were listed in Table S2. In chicken, 45, 44, and 39 transcription factors were predicted and targeted at the promoter regions of PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ, respectively. In human, only a total of 31, 36, and 40 transcription factors have been predicted at promoter regions of PPARα, PPARβ, and PPARγ, respectively, which were different from it in chicken.

Through comparing transcription factors, we found that numerous common transcription factors existed among PPAR members. Then they were compared pairwise among the three PPAR members, and the results were listed in Table 2. The PPARs shared 9 common transcription factors which were targeted at the promoter regions, including Sp1, CPE_bind, CP1, Oct-1, GATA-1, AP-2α, NF-1, GR, and C/EBPα in human, while in chicken, 11 common transcription factors were predicted and targeted at the promoter regions of chicken PPARs, which included CREB, SRF, ICSBP, Ftz, AP-1, Oct-1, GATA-1, AP-2α, NF-1, GR, and C/EBPα. However, the binding sites for each common transcription factor were varied among PPAR members.

Table 2.

The common transcription factors predicted in human and in chicken.

| Transcription factor | Binding sites and position | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken (α) | Human (α) | Chicken (β) | Human (β) | Chicken (γ) | Human (γ) | |

| Oct-1 | TTAT (−205) | TGCAT (−50) | TTAwTTk (−463) | GCTkT (−737) | AATAT (−18) | AATT (−75) |

| C/EBPα | TTGA (−62) | GTTGC (−302) | ACAT (−29) | ATCCCA (−23) | ACTC (−71) | TTGC (−192) |

| AP-2α | GGGG (−84) | GGCyG (−239) | GGCT (−108) | CCCrG (−65) | AGCCTG (−684) | GCCTG (−136) |

| NF-1 | TTTTGG (−457) | TGGCCA (−127) | GCCAA (−140) | TGsC (−15) | TGCCA (−560) | GCCAA (−383) |

| GR | TGTTCT (−137) | ACAA (−185) | AGAACA (−26) | ACAsA (−123) | ACAG (−128) | AGAAC (−679) |

| GATA-1 | TTAT (−205) | GsATT (−51) | GCAGA (−312) | CwGAT (−175) | AGATA (−58) | CTTATC (−438) |

| CREB | GTCA (−942) | CGTCA (−941) | ACrTCA (−432) | |||

| SRF | GCCwT (−385) | TTCCGG (−896) | AnATGG (−174) | |||

| ICSBP | GGAAA (−399) | CCCT (−39) | GTTT (−42) | |||

| Ftz | TAAT (−840) | TTAATT (−463) | TAAwTG (−343) | |||

| AP-1 | TGAsT (−776) | TCAGC (−556) | TGACTC (−69) | |||

| Sp1 | GGAGGG (−12) | GrGG (−38) | TGGG (−139) | |||

| CPE_bind | CrTCA (−74) | TGACGT (−968) | CCCC (−876) | |||

| CP1 | ATTGG (−125) | ATTGG (−913) | AkTGGT (−401) | |||

Finally, we quantified the coexisting transcription factors among PPAR members (Table 3). In human, the amount of the identical transcription factors between PPARα and PPARβ was 18, while the amount between PPARβ and PPARγ is 16. The number of identical transcription factors of PPARα and PPARγ was 12. In chicken, the group of PPARα/γ and PPARα/β shared 20 and 15 identical transcription factors, respectively.

Table 3.

The number of identical transcription factors among PPARs in human and in chicken.

| Human | Chicken | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPARα | PPARβ | PPARγ | PPARα | PPARβ | PPARγ | |

| PPARα | — | 18 | 12 | — | 15 | 20 |

| PPARβ | 18 | — | 16 | 15 | — | 18 |

| PPARγ | 12 | 16 | — | 20 | 18 | — |

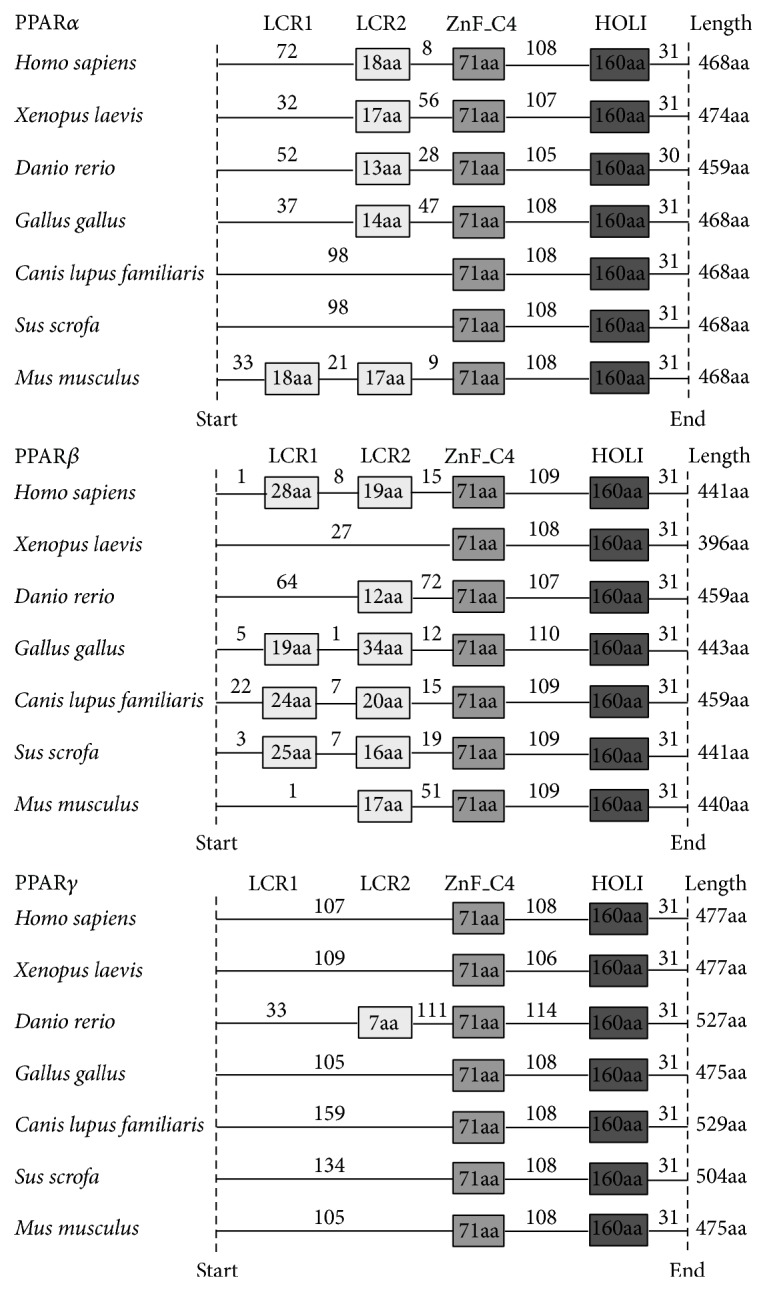

3.5. Prediction of miRNAs Target at the 3′ UTR Region of PPAR Members

The miRNAs in 3′ UTR of PPAR members were predicted in human. The results (Table S3) showed that, in the 3′ UTR region of PPARα, a total of 23 conserved binding sites of miRNAs were predicted in vertebrates, and 4 conserved sites of miRNA families were predicted in mammals. In the 3′ UTR region of PPARβ (Figure 4(b)) and PPARγ (Figure 4(c)), 5 and 3 conserved sites of miRNA families were predicted in vertebrates, respectively. Notably, the miR-17 and miR-9 were predicted in both 3′ UTR regions of PPARα and PPARβ, and the miR-27abc and miR-128 were predicted in both 3′ UTR regions of PPARα and PPARγ (Figure 4(a)).

Figure 4.

The miRNAs predicted and their targets sites in 3′ UTR region of PPAR genes in human. (a) PPARα; (b) PPARβ; (c) PPARγ. The miRNAs targets sites correspond to the 3′ UTR region of PPAR genes. The lower corner is the probability of preferential conservation for sites.

The functions of these miRNAs were enriched in PUBMED online. Among the 27 miRNA families, the vast majority were closely related with cancer. For example, the miR-142-3p [15], miR-19a [16], and miR-124 [17] were reported to be involved in hepatocellular carcinoma; the miR-9 [18] targeting to the 3′ UTR region of PPARα was associated with Hodgkin's lymphoma. In the 3′ UTR region of PPARβ, the miR-138 [19] were reported to be linked to anaplastic thyroid carcinoma; the miR-17 [20] was related to B-cell lymphoma; the miR-29c [21] was interrelated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. In the 3′ UTR region of PPARγ, the miR-128 [22] was associated with glioma.

4. Discussions

One new gene is mainly generated by the gene or genome duplication event [23]. PPARs as one of the NHR superfamilies evolve together with other NHR members, and after it has undergone twice time of gene duplication events, the vertebrate-specific PPAR is eventually diverged into three different isotypes [3, 7]. The phylogenetic tree of PPARs in the present study demonstrated that PPAR gene family may have yielded a gene duplication event, which first occurs in bony fishes before separation from the birds and mammals during the whole evolution process. PPARγ is closer to the outgroup than the other two branches, supporting that PPARγ might be the original ancestor gene in PPAR gene family. After being firstly duplicated in fish, PPAR begins to divide into two subtypes, including the PPARγ and the common ancestor of PPARα and PPARβ. These findings are consistent with the previous studies by Michalik et al., which depicted an evolutionary process of PPARs. Moreover, PPARα and PPARβ were clustered closer than others, supporting that they may originate from a homology ancestor gene, and their divergence may result from another gene duplication event in vertebrates; however, there is no sufficient evidence to support this hypothesis currently.

Following the gene duplication event in PPARs, the newly emerging receptors would have acquired the ligand binding capacities in an independent fashion [24]. Once such capacity was acquired, each receptor of PPARs may begin to further evolve and refine its specificity for a given ligand. Each PPAR isotype may then evolve by mutations, which lead to a more specific range of ligands across species. These hypotheses could be supported by the sequence variants among PPARs across species in the present study. Our results showed that all PPAR members contained the conserved HOLI and ZnF_C4 domains, which are important for keeping the functions of PPAR gene family. HOLI domain located in N-terminal of the PPAR protein is also known as ligand binding domain of hormone receptors [25]. It belongs to the LBD region that acts in response to ligand binding, which caused a conformational change in the receptor to induce a response, thereby acting as a molecular switch to turn on transcriptional activity [26]. In addition, ZnF_C4 domain is also called C4 zinc finger in nuclear hormone receptors. This domain was the DBD region, which recognizes specific sequences, connected via a linker region to a C-terminal LBD. Both HOLI and ZnF_C4 domains are highly conserved among PPAR members and are responsible for keeping their basic functions for PPAR family members.

In addition to the two conserved domains, PPAR family contained low complexity regions (LCRs). LCRs located near the left of ZnF_C4 domain are in great differences among PPAR members across species. Studies suggested that the positions of LCRs within a sequence might be important to both determine their binding properties and maintain biological functions [27]. There are no LCRs existing in PPARγ, suggesting that PPARγ might only keep the basic function of PPAR family. The number of LCRs in PPARα and PPARβ is similar and obviously more than PPARγ, indicating differential functions of PPARα and PPARβ from PPARγ. The results showed that the variants in LCRs might be involved in the diversity functions of PPAR members and supported a common origin of PPARα and PPARβ.

Due to the reason that ZnF_C4 and HOLI domain are important for keeping roles of PPAR members, we used patterns of selection pressure to analyze the adaptive evolution of the conserved protein sequences. The results showed that the HOLI domain was selected under a natural pressure in the evolutionary process, whereas the ZnF_C4 domain was not. It showed that ZnF_C4 domain was more conservative than HOLI domain in PPAR family, supporting a more important role of PPAR zinc finger in keeping PPARs' functions [28]. The HOLI domain in PPARβ with the most amounts of positive selection sites among PPAR members suggested that the variations in these positive selection sites were more beneficial for PPARβ phylogenetic towards diversity functions. Studies have confirmed that these chemical properties of amino acid residues were important to sustain normal protein folding and keep functions [29]. For instance, sulfhydryl groups of the peptide chain of two cysteines (cysteine, referred to as S) form two disulfide linkages with oxidation reaction. Whether it breaks or reshapes into a new one, it also could adjust protein to perform certain function [30]. Therefore, it can be inferred that the nucleotide variants in HOLI domain could be responsible for diversity functions of PPAR members. In a 95% posterior probability, the positive selection sites were 118G, 137S, and 143I in PPARα HOLI domain, were 20S, 21S, 58S, and 117P in PPARβ HOLI domain, and were 16S and 75G in PPARγ HOLI domain. It is interesting to point out that the positive selection sites in HOLI domain of PPARα and PPARβ share more similarity in locations and amino acid residues, supporting a homology function of PPARα and PPARβ.

The regulatory mechanism of gene expressions plays an important role in tissue distribution and distinct biological functions of genes. In eukaryotes, most genes are initiated and transcribed by lots of specific transcription factors targeting at their promoter regions [31]. Through predicting the transcription factors and their binding sites in promoter region of PPARs, we found that the transcription factors were varied among PPAR members in human and chicken, which may account for the specific tissue expression and distinct functions of PPARs. Some of these predicted transcription factors and their regulatory effects on PPARs are consistent with the previous reports; for example, the transcription factors AP1 and NF-kB were proved to enhance the expression of PPARβ activity [32]. Some of these transcription factors are also tissue specific, for example, the SP1 expressed in adenocarcinomas of the stomach [33], CP1 highly expressed in liver, kidney, and intestine but weakly expressed in adrenals and in lactating mammary glands [34, 35], and NF-1 detected in brain, peripheral nerve, lung, colon, and muscle [36], and so forth. It can be speculated that the variants in the promoter regions of PPARα and PPARβ result into differential transcription factors binding on them that eventually influence their expressions and tissues distributions. Additionally, there are 18 common transcription factors between PPARβ and PPARα, whereas the PPARγ shared the least amount of common transcription factors with the other two members, which may contribute to the similarity in expression characteristics between PPARβ and PPARα.

The miRNA can combine with the target mRNA by base pair, which leads to degradation or inhibition of the quantity levels of the target mRNA, thereby regulating gene expressions [37]. The regulation of miRNA on gene expressions is another path shaping gene expression patterns and biological processes [38]. In the present study, the miRNAs and their targets sites in 3′ UTR region of PPARs were predicted, and it was observed that the quantity of miRNAs was obviously differential in PPAR members. The number of miRNAs predicted in PPARα was significantly more than the other two members. Moreover, it was worth noticing that most of the miRNAs were predicted in PPARα, only a minority of them predicted in at least two PPAR isotypes; for example, only miRNA-128 was found in PPARα and PPARγ and miRNA-9 was found in PPARα and PPARβ. These differences may be correlated with the distinct functions of PPAR isotypes, and PPARα may be regulated by miRNAs in a much more complex way than the other two PPARs.

5. Conclusions

In the present study, the evolutionary pattern and regulation characteristics of PPARs were analyzed. The three isotypes of PPAR gene family may emerge from twice times of gene duplication events. PPARγ might be the original ancestor gene in PPAR gene family. The conserved domains of HOLI domain and ZnF_C4 are essential for keeping basic roles of PPAR gene family, and the variant domain of LCRs may be responsible for their divergences in functions. The positive selection sites in HOLI domain are beneficial for PPARs to evolve towards diversity functions. The variants in the promoter regions and 3′ UTR of PPARs resulted into differential transcription factors and miRNAs involved in regulating PPAR members that may eventually influence their expressions and tissue distributions.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: There are 27 sequences for PPARα, 16 sequences for PPARβ and 20 sequences for PPARγ. Each sequence represents a species and its accession number information.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31301964), Chinese Agriculture Research Service (no. CARS-43-6), the Major Project of Sichuan Education Department (13ZA0252), and the Breeding of Multiple Crossbreeding Systems in Waterfowl (2011NZ0099-8).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contribution

Tianyu Zhou and Xiping Yan contribute equally as the co-first authors of the paper.

References

- 1.Tontonoz P., Hu E., Spiegelman B. M. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPARγ2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79(7):1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90006-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark R. B. The role of PPARs in inflammation and immunity. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2002;71(3):388–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daynes R. A., Jones D. C. Emerging roles of PPARs in inflammation and immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2002;2(10):748–759. doi: 10.1038/nri912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiue Y.-L., Chen L.-R., Tsai C.-J., Yeh C.-Y., Huang C.-T. Emerging roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in the pituitary gland in female reproduction. Biomarkers and Genomic Medicine. 2013;5(1-2):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gmbhs.2013.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop-Bailey D., Bystrom J. Emerging roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ in inflammation. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2009;124(2):141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger J. P., Akiyama T. E., Meinke P. T. PPARs: therapeutic targets for metabolic disease. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2005;26(5):244–251. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michalik L., Desvergne B., Dreyer C., Gavillet M., Laurini R. N., Wahli W. PPAR expression and function during vertebrate development. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2002;46(1):105–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braissant O., Foufelle F., Scotto C., Dauça M., Wahli W. Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-α, -β, and -γ in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996;137(1):354–366. doi: 10.1210/en.137.1.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu X., Zou X., Chang Q., et al. The evolutionary pattern and the regulation of stearoyl-CoA desaturase genes. BioMed Research International. 2013;2013:12. doi: 10.1155/2013/856521.856521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall T. A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24(8):1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24(8):1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nielsen R., Yang Z. Likelihood models for detecting positively selected amino acid sites and applications to the HIV-1 envelope gene. Genetics. 1998;148(3):929–936. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.3.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Z., Swanson W. J., Vacquier V. D. Maximum-likelihood analysis of molecular adaptation in abalone sperm lysin reveals variable selective pressures among lineages and sites. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2000;17(10):1446–1455. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gramantieri L., Ferracin M., Fornari F., et al. Cyclin G1 is a target of miR-122a, a MicroRNA frequently down-regulated in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Research. 2007;67(13):6092–6099. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budhu A., Jia H. L., Forgues M., et al. Identification of metastasis-related microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;47(3):897–907. doi: 10.1002/hep.22160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furuta M., Kozaki K. I., Tanaka S., Arii S., Imoto I., Inazawa J. miR-124 and miR-203 are epigenetically silenced tumor-suppressive microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2009;31(5):766–776. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nie K., Gomez M., Landgraf P., et al. MicroRNA-mediated down-regulation of PRDM1/Blimp-1 in Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells: a potential pathogenetic lesion in Hodgkin lymphomas. American Journal of Pathology. 2008;173(1):242–252. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitomo S., Maesawa C., Ogasawara S., et al. Downregulation of miR-138 is associated with overexpression of human telomerase reverse transcriptase protein in human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Science. 2008;99(2):280–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00666.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inomata M., Tagawa H., Guo Y. M., Kameoka Y., Takahashi N., Sawada K. MicroRNA-17-92 down-regulates expression of distinct targets in different B-cell lymphoma subtypes. Blood. 2009;113(2):396–402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-163907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calin G. A., Ferracin M., Cimmino A., et al. A MicroRNA signature associated with prognosis and progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(17):1793–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y., Chao T., Li R., et al. MicroRNA-128 inhibits glioma cells proliferation by targeting transcription factor E2F3a. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2009;87(1):43–51. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prince V. E., Pickett F. B. Splitting pairs: the diverging fates of duplicated genes. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2002;3(11):827–837. doi: 10.1038/nrg928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Escriva H., Bertrand S., Laudet V. The evolution of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Essays in Biochemistry. 2004;40:11–26. doi: 10.1042/bse0400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger J., Moller D. E. The mechanisms of action of PPARs. Annual Review of Medicine. 2002;53:409–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edwards D. P. The role of coactivators and corepressors in the biology and mechanism of action of steroid hormone receptors. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 2000;5(3):307–324. doi: 10.1023/A:1009503029176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coletta A., Pinney J. W., Solís D. Y. W., Marsh J., Pettifer S. R., Attwood T. K. Low-complexity regions within protein sequences have position-dependent roles. BMC Systems Biology. 2010;4, article 43 doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nolte R. T., Wisely G. B., Westin S., et al. Ligand binding and co-activator assembly of the peroxisome proliferator- activated receptor-γ . Nature. 1998;395(6698):137–143. doi: 10.1038/25931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogg P. J. Disulfide bonds as switches for protein function. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2003;28(4):210–214. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wedemeyer W. J., Welker E., Narayan M., Scheraga H. A. Disulfide bonds and protein folding. Biochemistry. 2000;39(15):4207–4216. doi: 10.1021/bi992922o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahman I., MacNee W. Role of transcription factors in inflammatory lung diseases. Thorax. 1998;53(7):601–612. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.7.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delerive P., de Bosscher K., Besnard S., et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α negatively regulates the vascular inflammatory gene response by negative cross-talk with transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(45):32048–32054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Infantino V., Convertini P., Iacobazzi F., Pisano I., Scarcia P., Iacobazzi V. Identification of a novel Sp1 splice variant as a strong transcriptional activator. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2011;412(1):86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schweifer N., Barlow D. P. The Lx1 gene maps to mouse Chromosome 17 and codes for a protein that is homologous to glucose and polyspecific transmembrane transporters. Mammalian Genome. 1996;7(10):735–740. doi: 10.1007/s003359900223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alnouti Y., Petrick J. S., Klaassen C. D. Tissue distribution and ontogeny of organic cation transporters in mice. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 2006;34(3):477–482. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersen L. B., Ballester R., Marchuk D. A., et al. A conserved alternative splice in the von recklinghausen neurofibromatosis (NF1) gene produces two neurofibromin isoforms, both of which have GTPase-activating protein activity. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1993;13(1):487–495. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis B. P., Burge C. B., Bartel D. P. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Appasani K. MicroRNAs: From Basic Science to Disease Biology. Cambridge, Mass, USA: Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: There are 27 sequences for PPARα, 16 sequences for PPARβ and 20 sequences for PPARγ. Each sequence represents a species and its accession number information.