Abstract

Context

Low serum IGF-1 levels have been linked to increased risk for development of type 2 diabetes. However, the physiological role of IGF-1 in glucose metabolism is not well characterized.

Objective

Our objective was to explore glucose and lipid metabolism associated with variations in serum IGF-1 levels.

Design, Setting and Participants

IGF-1 levels were measured in healthy, nonobese male volunteers aged 18 to 50 years from a biobank (n = 275) to select 24 subjects (age 34.8 ± 8.9 years), 12 each in the lowest (low-IGF) and highest (high-IGF) quartiles of age-specific IGF-1 SD scores. Evaluations were undertaken after a 24-hour fast and included glucose and glycerol turnover rates using tracers, iv glucose tolerance test to estimate peripheral insulin sensitivity (IS) and acute insulin and C-peptide responses (indices of insulin secretion), magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure intramyocellular lipids (IMCLs), calorimetry, and gene expression studies in a muscle biopsy.

Main Outcome Measures

Acute insulin and C-peptide responses, IS, and glucose and glycerol rate of appearance (Ra) were evaluated.

Results

Fasting insulin and C-peptide levels and glucose Ra were reduced (all P < .05) in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects, indicating increased hepatic IS. Acute insulin and C-peptide responses were lower (both P < .05), but similar peripheral IS resulted in reduced insulin secretion adjusted for IS in low-IGF subjects (P = 0.044). Low-IGF subjects had higher overnight levels of free fatty acids (P = .028) and β-hydroxybutyrate (P = .014), increased accumulation of IMCLs in tibialis anterior muscle (P = .008), and a tendency for elevated fat oxidation rates (P = .058); however, glycerol Ra values were similar. Gene expression of the fatty acid metabolism pathway (P = .0014) was upregulated, whereas the GLUT1 gene was downregulated (P = .005) in the skeletal muscle in low-IGF subjects.

Conclusions

These data suggest that serum IGF-1 levels could be an important marker of β-cell function and glucose as well as lipid metabolic responses during fasting.

Increasing evidence suggests that IGF-1 plays an important role in glucose metabolism (1). IGF-1 shares structural homology and downstream pathways with insulin, and exogenous administration of recombinant human (rh)IGF-1 increases insulin sensitivity (IS) (1). Furthermore, β-cell–specific IGF-1 receptor knockout (KO) and β-cell–specific IGF-1 expression in GH receptor KO mouse models documented a vital role of IGF-1 signaling in maintaining β-cell function (1, 2). Associations of IGF-1 gene polymorphisms with fasting insulin levels and IS reported in genome-wide association studies also suggest a direct effect of IGF-1 on glucose metabolism (3). However, physiological roles of IGF-1 in glucose metabolism in humans are not well characterized (1).

Low IGF-1 levels are associated with impaired glucose intolerance and type 2 diabetes (T2D) (4, 5) and predicted an increased risk for development of these conditions in 2 large prospective cohorts (6, 7). However, it is not clear whether these associations are related to underlying impairments in β-cell function because portal insulin is an important promoter of hepatic IGF-1 synthesis (8). Therefore, evaluation of healthy adults is useful to delineate the physiological roles of IGF-1.

GH is the primary regulator of circulating IGF-1 levels (1). The GH/IGF-1 axis plays a central role in adapting to fasting by directing the substrate metabolism away from carbohydrate utilization to mobilization of lipids from adipose tissue and oxidation, particularly in skeletal muscles (9). We hypothesized that variations in circulating IGF-1 levels will be associated with alterations in glucose as well as lipid metabolism during fasting. In this study, we evaluated healthy adults with IGF-1 levels at the extreme quartiles of normal distribution during a 24-hour fast and employed a frequently sampled iv glucose tolerance test (IVGTT) and stable isotope techniques to assess glucose and lipid metabolism. The skeletal muscle metabolism was studied by evaluating magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS)-derived measures of intramyocellular lipid (IMCL) and in vivo mitochondrial function and gene expression related to glucose and lipid metabolism in muscle biopsy specimens.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Healthy, nonobese, Caucasian male volunteers, 18 to 50 years of age, who have contributed a serum sample were identified in the Cambridge BioResource (CBR), and IGF-1 levels were measured in the stored sera (n = 275). Cambridge BioResource (www.cambridgebioresource.org.uk/) is a resource from which individuals with a particular genotype or phenotype can be identified and invited to participate in research studies (10). Age-specific IGF-1 SD scores (SDS) were estimated using population-derived normative data (11). The IGF-1 levels showed good reproducibility over time (Supplemental Methods). Age-matched volunteers in the lowest (n = 12) and the highest (n = 12) quartiles of IGF-1 SDS were recruited into the study. Volunteers with diabetes or on medications were excluded. The Cambridge BioResource team selected the volunteers based on IGF-1 levels and kept the investigators and volunteers blinded to the levels. The study was approved by the Cambridge Local Research Ethics Committee and conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization standards for Good Clinical Practice. Informed consent was obtained before recruitment.

Study outline

The study involved fasting for 30 hours from 8:00 am on day 1 to 2:00 pm on day 2 (Figure 1). The subjects abstained from alcohol and vigorous physical activity and were on their normal diet for 3 days before the study. The evening meal on the previous day and the breakfast on day 1 were standardized based on one-third of the recommended daily intake of energy and contained approximately 50% carbohydrate, 30% fat, and 20% protein. The meals were prescribed by a dietician based on a retrospective food diary and were prepared at home. The participants ate the evening meal on the previous day at 7:30 pm and the breakfast on day 1 at 7:30 am and subsequently remained fasted for 30 hours.

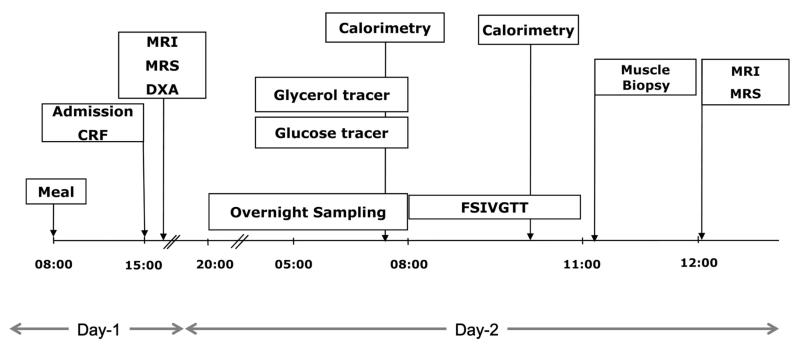

Figure 1.

Study design. Abbreviations: CRF, clinical research facility; DXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; FSIVGTT, frequently sampled IVGTT.

The subjects were admitted to the Clinical Research Facility (Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK) at 2:00 pm on day 1 (Figure 1), and the body composition was assessed using a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan. At 7:30 pm, an iv cannula was inserted into each antecubital fossa; one for sampling and the other for infusions. Overnight blood sampling was undertaken from 8:00 pm to 8:00 am for GH at 15-minute intervals and for glucose, C-peptide, and insulin at hourly intervals. Free fatty acids (FFAs) and triglycerides were measured at 4-hour intervals, whereas β-hydroxybutyrates were evaluated at 8:00 pm and 8:00 am. Primed infusions of [6,6-d2] glucose (4 mg/kg followed by 0.04 mg/kg/min) and [1,1,2,3,3-d5] glycerol (0.15 mg/kg followed by 0.01 mg/kg/min) tracers were administered between 5:00 and 8:00 am. At 8:00 am, a frequently sampled IVGTT was undertaken, which involved administering a glucose bolus (270 mg/kg glucose spiked with 30 mg/kg [6,6-d2] glucose) followed by an insulin bolus (0.02 IU insulin/kg) at 8:20 am, as described in detail elsewhere (12). Adiponectin levels were measured at 8:00 am, whereas IGF binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) levels were evaluated at 8:00 and 11:00 am. At 11:30 am, a muscle biopsy was obtained from left vastus lateralis muscle using a Bergström biopsy needle as an optional procedure (Supplemental Methods). The study was completed at 2:00 pm, and the participants were given a meal before discharge.

Other study procedures

Indirect calorimetry

The respiratory quotient (RQ) and resting energy expenditure (REE) were estimated by indirect calorimetry (GEM; GEM Nutrition Ltd, UK) performed before (07:30 am) and 2 hours after (10:00 am) IVGTT. Carbohydrate and fat oxidation rates were calculated based on a fixed contribution (10%) from protein oxidation to REE (13).

Magnetic resonance imaging and MRS evaluations

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/MRS evaluations were undertaken at 8 and 28 hours of fasting (4:00 pm on day 1 and noon on day 2) on a whole-body Siemens 3T Verio scanner in the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre. The voxels were carefully positioned in the second scanning to ensure accurate relocalization as in the first evaluation. The IMCL was measured from the right soleus and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles (Supplemental Methods) and quantified as the ratio relative to creatine resonance at 3.0 ppm. Hepatic fat is measured using methods described previously and expressed as the methylene peak at 1.3 ppm relative to the water peak (14). In vivo mitochondrial function was assessed from phosphocreatine recovery kinetics in the right quadriceps muscle after a standardized exercise using established methods (15) and expressed as t1/2. Abdominal visceral and sc fat was estimated from a transaxial T1-weighted image acquired at the level of the L4 vertebral body and analyzed using methods described previously (14).

Assays

Serum IGF-1 concentrations were determined using the Immulite 2000 assay (Diagnostic Products Corporation), with an interassay coefficient of variation of 5.9% (11). Glucose and glycerol isotope enrichments were measured by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry using the Agilent GCMS 5973N mass spectrometer system, as described in detail elsewhere (16). Commercially available kits are used for other assays (Supplemental Methods).

Microarray hybridization and analysis of muscle biopsy

Single-stranded cDNA was generated from the RNA extracted from skeletal muscle and hybridized onto Human Affymetrix Gene ST 1.0 array (17) (Supplemental Methods). The data from each chip was normalized to the 50th centile of the measurements from that chip (GEO accession number GSE2075). Genes significantly upregulated or downregulated by at least 1.10-fold compared with the high-IGF subjects were considered differentially regulated. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-sample Student’s t test, looking for differentially expressed genes in the low-IGF subjects. The test was applied to the mean of each normalized value against the baseline value of 1, at which the genes do not show any differential expression with respect to the high-IGF subjects. We considered P < .05 to be significant, and the genes that met the above criteria were taken forward for pathway analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Ingenuity Systems) (17). The microarray results were validated using quantitative PCR on 4 genes (ACOX2, MYLCD, CPT1A, and SLC2A1) (Supplemental Methods).

Calculations

The homeostatic model assessment (HOMA)-IS was estimated from the average of 3 glucose and C-peptide concentrations obtained at 5-minute intervals before the IVGTT using the HOMA-2 calculator (11, 18). The isotope enrichment is expressed as the tracer to tracee ratio, and the glucose and glycerol rate of appearance (Ra) at 24 hours fasting (07:30 to 8:00 am on day 2) were calculated as the quotient of the infusion rate and the steady-state suprabasal tracer to tracee ratio. During the IVGTT, the whole-body IS (insulin sensitivity index, SI) and glucose effectiveness were calculated from the minimal model using Min-Mod Millenium version 6.02 (Richard N. Bergman, Los Angeles, CA). The equivalent indices for the stable isotope data were calculated using a custom-designed spreadsheet (Excel version 14.0; Microsoft), using nonlinear optimization to obtain the model parameters. The area under the curve (AUC) of insulin and C-peptide during the first 10 minutes of the IVGTT above basal levels and adjusted for glucose excursion provided acute insulin and C-peptide responses, the proxies for first-phase insulin secretion. The product of the acute C-peptide response and IS (SI) provided a measure of adequacy of insulin secretion for the degree of IS, the disposition index. Overnight GH secretion was analyzed by the Fourier transform analysis for oscillatory secretion (12) and probit analysis of the observed concentrations (OCs) (12). The OC gives an estimate of the baseline (OC-5), mean (OC-50), and peak concentrations (OC-95), which are the thresholds below which the concentrations are measured 5%, 50%, and 95% of the time, respectively.

Statistics

The nonnormally distributed variables were log transformed before analysis (insulin, C-peptide, IS, disposition index, β-hydroxybutyrate, FFAs, and GH). The groups were compared using Student’s t test. Changes in IMCL from 8 to 28 hours of fasting were compared in a multivariate model using the baseline measurement as a covariate (SPSS version 18). Data are expressed as mean ± SE if not otherwise stated.

Results

The low-IGF and high-IGF subjects were similar in anthropometric measurements and body composition (Table 1). Six volunteers were overweight (body mass index, 25–30 kg/m2), but were equally distributed between the groups. None of the participants were vegans or on calorie restricted diets.

Table 1.

Details of the Subjectsa

| Low-IGF, n = 12 | High-IGF, n = 12 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 35.0 ± 2.7 | 34.8 ± 2.5 | .95 |

| Weight, kg | 75.0 ± 2.0 | 77.4 ± 2.8 | .49 |

| Height, cm | 181.1 ± 2.5 | 179.9 ± 1.7 | .69 |

| Hip circumference, cm |

98.5 ± 1.4 | 98.3 ± 2.5 | .96 |

| Waist circumference, cm |

85.1 ± 2.7 | 86.2 ± 2.7 | .76 |

| Waist hip ratio | 0.86 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.02 | .61 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 |

23.1 ± 0.8 | 23.9 ± 0.7 | .38 |

| Lean mass, kg | 56.6 ± 1.2 | 58.0 ± 1.7 | .50 |

| Fat mass, % | 18.4 ± 2.4 | 20.2 ± 2.1 | .58 |

| Visceral fat, cm2 | 41.4 ± 8.0 | 50.2 ± 8.0 | .77 |

| Abdominal sc fat, cm2 |

117.1 ± 13.4 | 149.1 ± 20.0 | .19 |

| IGF-1, ng/mL | 156.3 ± 12.4 | 268.1 ± 20.1 | <.0001 |

| IGF-1 SDS | −0.83 ± 0.09 | +1.13 ± 0.14 | <.0001 |

| Range | −1.32 to −0.46 | +0.71 to +2.4 |

Unless indicated otherwise, results are shown as mean ± SE.

Glucose metabolism

Overnight evaluation (8:00 pm to 8:00 am, 12–24 hours of fasting)

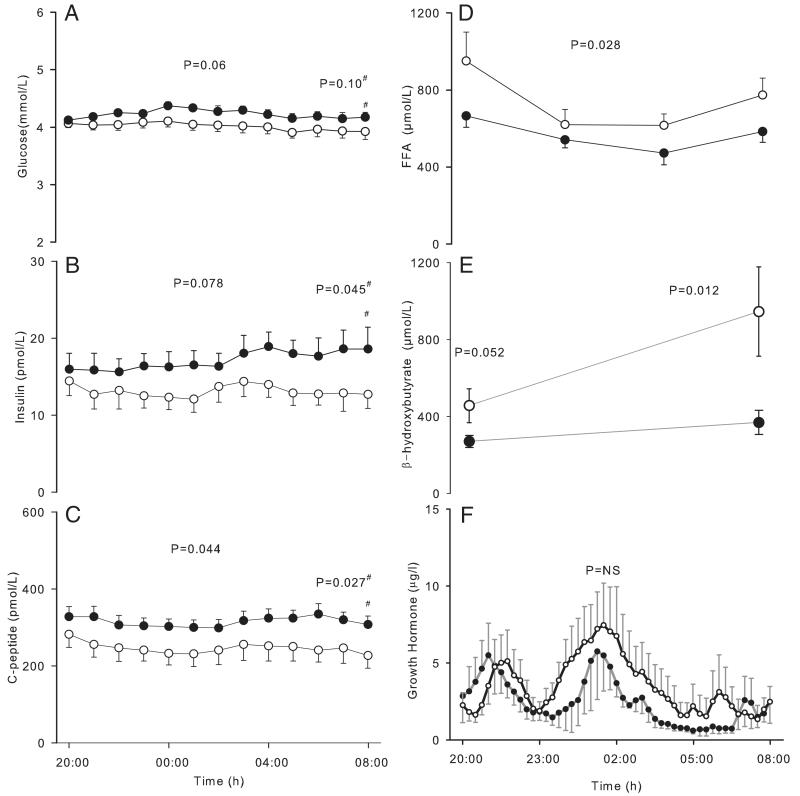

The glucose levels were within normal ranges (range, 3.62–4.42 mmol/L) at 12 hours of fasting. Overnight glucose and insulin levels tended to be lower, and the C-peptide levels were significantly reduced (P = .044) in the low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects (Figure 2 and Table 2). At 24 hours of fasting, both insulin (12.5 ± 1.72 vs 18.61 ± 2.11 pmol/L, P = .045) and C-peptide levels (229.9 ± 34.9 vs 311.8 ± 21.2 pmol/L, P = .027) were significantly reduced, whereas the glucose levels tended to be lower (3.9 ± 0.14 vs 4.16 ± 0.18 mmol/L, P = .093) in the low-IGF group. HOMA-IS was increased (P = .019), and endogenous glucose production estimated using glucose Ra adjusted for insulin levels was reduced (P = .043) in the low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects at 24 hours of fasting.

Figure 2.

Overnight concentrations of hormones and metabolites (12–24 hours of fasting). A, Glucose; B, insulin; C, C-peptide; D, FFAs; E, β-hydroxybutyrate; F, GH (○, low-IGF subjects; ●, high-IGF subjects). Error bars show SEs. #, P values obtained by comparing the average of 3 measurements obtained at 5-minute intervals before the IVGTT.

Table 2.

Metabolic Parameters During 12 to 24 Hours of Fasting and IVGTTa

| Low-IGF | High-IGF | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overnight evaluations | |||

| Glucose, mmol/L | 4.01 ± 0.10 | 4.24 ± 0.05 | .060 |

| Insulin, pmol/L | 13.1 ± 1.57 | 17.1 ± 1.47 | .078 |

| C-peptide, pmol/L | 246.4 ± 34.0 | 316.7 ± 19.9 | .044 |

| HOMA-IS, % | 272.5 ± 38.4 | 167.03 ± 16.70 | .019 |

| Free fatty acid, μmol/L | 740 ± 66.7 | 565 ± 31.7 | .028 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 0.77 ± 0.07 | 0.94 ± 0.09 | .14 |

| β-Hydroxybutyrate, μmol/L | 700.9 ± 152.7 | 319.8 ± 40.2 | .014 |

| IGFBP-1, ng/mL | 66.0 ± 15.18 | 26.09 ± 5.11 | .030 |

| Adiponectin, μg/mL | 5.07 ± 2.18 | 6.10 ± 2.34 | .27 |

| Glucose Ra, μmol/kg/min | 7.39 ± 0.25 | 7.59 ± 0.32 | .65 |

| Glucose Ra adjusted for insulin levels, (μmol/kg/min) · (pmol/L) | 91.73 ± 12.40 | 141.01 ± 16.82 | .043 |

| Glycerol Ra, μmol/kg/min | 4.25 ± 0.55 | 3.9 ± 0.37 | .61 |

| GH, μg/L | |||

| Overnight AUC | 3.50 ± 1.16 | 2.19 ± 0.31 | .31 |

| Basal (OC-5) | 0.27 ± 0.19 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | .81 |

| Mean (OC-50) | 1.68 ± 0.85 | 0.91 ± 0.20 | .75 |

| Maximal (OC-95) | 18.00 ± 5.50 | 10.62 ± 1.42 | .76 |

| IVGTT | |||

| AUC glucose (first 10 min), mmol/L · min | 65.91 ± 3.89 | 55.67 ± 4.13 | .060 |

| Acute insulin response, [pmol/L · min]/[mmol/L] | 160.5 ± 16.6 | 225.4 ± 24.0 | .037 |

| Acute C-peptide response, [pmol/L · min]/[mmol/L] | 756 ± 65 | 999 ± 94 | .027 |

| IS (SI), 104 pmol−1 min−1 | 0.75 ± 0.09 | 0.80 ± 0.08 | .68 |

| Glucose effectiveness, 10−3 min−1 | 8.65 ± 1.40 | 6.72 ± 1.40 | .34 |

| Disposition index | 5.23 ± 0.66 | 7.56 ± 0.90 | .044 |

| Stable isotope-derived measures | |||

| IS, 104 pmol−1 min−1 | 0.64 ± 0.12 | 0.71 ± 0.15 | .68 |

| Glucose effectiveness, min−1 | 0.065 ± 0.008 | 0.048 ± 0.01 | .54 |

Mean overnight (8:00 pm to 8:00 am) concentrations of glucose, insulin, C-peptide, free fatty acids, triglycerides, and β-hydroxybutyrates. HOMA-IS, IGFBP-1, and adiponectin concentrations were assessed at 8:00 am, and glucose and glycerol Ra between 7:30 and 8:00 am. Results are shown as mean ± SE.

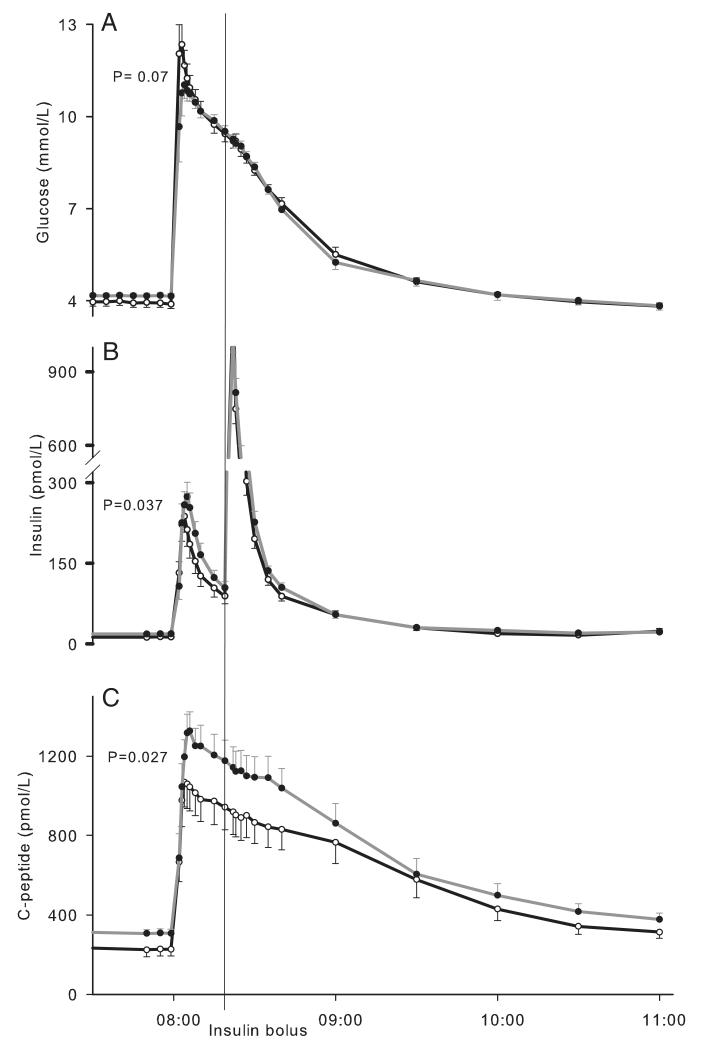

IVGTT

The AUC of glucose levels during the first 10 minutes of IVGTT tended to be higher in low-IGF subjects (Figure 3 and Table 2). Acute insulin and C-peptide responses were lower in the low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects (P = .037 and 0.027, respectively), whereas the whole-body IS (SI) was similar in both groups. This resulted in a lower disposition index in low-IGF subjects (P = .044). Peripheral IS and glucose effectiveness derived from cold isotope methods were similar between the groups.

Figure 3.

Glucose metabolism during the IVGTT. A, Glucose; B, insulin; C, C-peptide (○, low-IGF subjects; ●, high-IGF subjects). Error bars represent SEs. P values were derived from comparing AUC of glucose above baseline during the first 10 minutes of the IVGTT (A), acute insulin response (B), and acute C-peptide response (C).

Lipid metabolism

During the overnight period, levels of FFA and β-hydroxybutyrate (Figure 2 and Table 2) were higher in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects (P = .028 and 0.014, respectively). However, glycerol Ra and serum triglyceride levels were similar in both groups. Suppression of FFA levels at 1 hour after the IVGTT was similar between the groups (low-IGF vs high-IGF, 77.23% ± 3.63% vs 71.91% ± 3.14%, P = .28), whereas an increased suppression of triglyceride levels was observed in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects (19.77% ± 2.44% vs 12.39% ± 2.00%, P = .029).

Indirect calorimetry

After 24 hours of fasting, the REE was similar in both groups (Supplemental Figure 1); however, the RQ tended to be reduced (P = .085), indicating a trend for higher fat oxidation rates (P = .058) and lower carbohydrate oxidation rates (P = .079) in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects. The low-IGF subjects continued to have a tendency for lower RQ (P = .077) after the IVGTT; however, the substrate oxidation rates were similar.

GH secretion

No differences were observed in the overnight AUC and the basal, mean, and peak GH levels between the groups (Table 2 and Figure 2). The AUC of the oscillatory amplitude of the GH (low-IGF, 2.1 ± 0.06, vs high-IGF, 2.1 ± 0.12) and the pulse periodicity on the Fourier transformation were also similar.

IGFBP-1 and adiponectin levels

IGFBP-1 levels were higher in low-IGF subjects after 24 hours of fasting compared with high-IGF subjects (P = .030) (Table 2); however, the degree of suppression after the IVGTT was similar. Serum adiponectin levels at 24 hours of fasting were similar between the groups.

MRS evaluations

Intramyocellular lipids

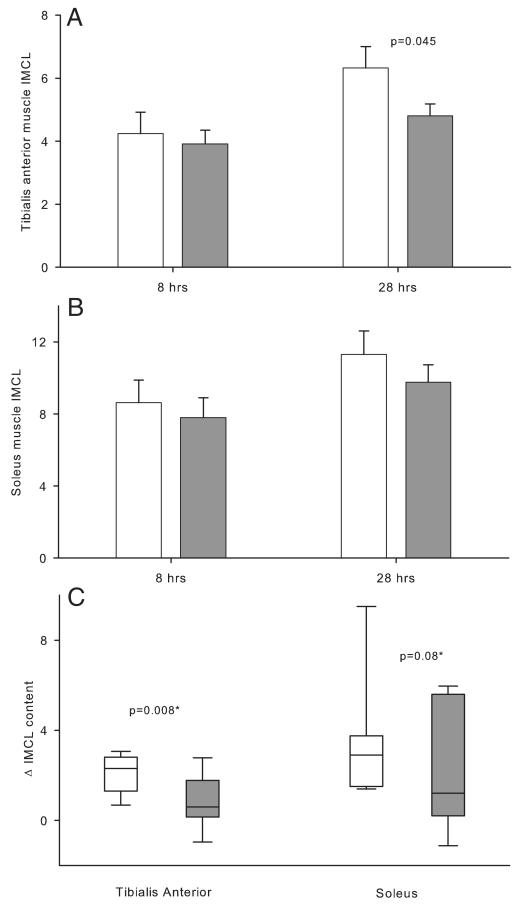

Six of the 48 spectra could not be interpreted due to interference from the extramyocellular lipids. With all of the study subjects, prolongation of fasting from 8 to 28 hours was associated with increases in the IMCLs in TA muscle (4.48 ± 0.48 vs 5.80 ± 0.46, P < .0001) and soleus muscle (8.22 ± 0.81 vs 10.44 ± 0.78, P = .0004). At 8 hours of fasting, the IMCLs in TA and soleus muscles were similar in both groups (Figure 4). However, at 28 hours of fasting, IMCLs in TA muscle were higher in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects (P = .045), whereas soleus muscle IMCLs were similar. The increases in IMCLs from 8 to 28 hours of fasting was significantly greater in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects in the TA muscle (P = .008) and tended to be higher in the soleus muscle (P = .08). The IMCL in either muscle group was not associated with IS derived from the HOMA model or the IVGTT.

Figure 4.

IMCLs during fasting. A, TA muscle; B, soleus muscle; C, changes in IMCL from 8 to 28 hours of fasting. IMCL is expressed as a ratio relative to creatine resonance. White bars/box plots represent low-IGF subjects; gray bars/box plots represent high-IGF subjects. Error bars show SEs (A and B) or interquartile ranges (C). *, P values derived from a univariate model accounting for the baseline measurements.

Hepatic fat

The hepatic fat content was similar in both groups at 8 hours (low-IGF vs high-IGF 1.00% ± 0.34% vs 0.90% ± 0.25%, P = .80), and no significant increases were observed from 8 to 28 hours of fasting.

Mitochondrial function

In vivo mitochondrial function was similar in both groups (low-IGF vs high-IGF, 16.82 ± 1.88 vs 17.97 ± 1.66 seconds, P = .90).

Microarray analysis of muscle biopsy

Muscle biopsies were obtained from 9 subjects in each group. Compared with high-IGF subjects, we found upregulation of 129 genes and downregulation of 144 genes in the low-IGF subjects (Supplemental Table 1). The Ingenuity pathway analysis categorized the groups of functionally related annotated genes into functions and pathways. Focusing on genes related to glucose and lipid metabolism, we found that lipid metabolism function (14 genes, P = 1.21 × 10−4), energy production function (6 genes, P = 1.21 × 10−4), and fatty acid metabolism pathway (5 genes, P = .0014) were upregulated in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects (Supplemental Table 2). When specific genes were mapped on the pathway for lipid metabolism, consistent changes in the same direction were observed in several genes involving FFA transport, β-oxidation, and ω-oxidation of lipids (Supplemental Figure 2). In relation to glucose metabolism, the GLUT1 gene (SLC2A1) was downregulated in the low-IGF group (fold change 1.17, P = .005). The quantitative PCR validation of 4 genes showed significant changes (MYLCD, CPT1A, and SLC2A1) or trends (ACOX2) in the same direction as in the microarray analysis (Supplemental Figure 3).

Discussion

The main findings of the study are the reduced insulin secretion and increased hepatic IS in healthy adult males with serum IGF-1 levels in the lowest quartile compared with those in the highest quartile. Enhanced lipid metabolism, increased accumulation of IMCLs, and upregulation of genes for fat oxidation pathways in skeletal muscle were also observed in low-IGF subjects.

Both genetic factors and environmental influences such as diet are associated with variations in IGF-1 levels in adults (19, 20). However, nutrition is unlikely to be a confounding factor in this study because the body composition was similar in the groups. Adults born small for gestational age (SGA) also have low IGF-1 levels (21), suggesting a role for developmental programming in modulating the GH/IGF-1 axis.

Our observations of reduced insulin secretion in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects support similar associations between IGF-1 levels and the insulin secretion derived from oral glucose tolerance tests reported in children and adults (6, 22). Higher HOMA-IS and lower endogenous glucose production suggest increased hepatic IS in low-IGF subjects. Greater suppression of triglyceride levels after the insulin bolus during the IVGTT in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects despite similar reductions in FFA levels may also reflect enhanced IS for inhibiting hepatic triglyceride synthesis (23). Yet, the whole-body IS assessed during the IVGTT and the peripheral IS measured using tracer techniques were similar. Prolongation of fasting from 12 to 24 hours decreases the whole-body IS by 50% (12) and could have reduced the power of the study in detecting changes in peripheral IS. Nevertheless, reduced expression of the GLUT1 gene, which mediates basal glucose transport into skeletal muscle and is upregulated by IGF-1 (24, 25), may explain the trend for higher glucose levels during the IVGTT in low-IGF subjects and supports an effect of IGF-1 on peripheral glucose disposal.

Population studies have reported a conflicting relationship between circulating IGF-1 levels and IS ranging from none (26) to U-shaped (4) and positive associations (5, 27). The inconsistent associations in heterogeneous populations could be due to the strong inverse relationship between adiposity and IGF-1 levels (27). However, in selected populations such as lean SGA children, lower IGF-1 levels are associated with increased HOMA-IS (11, 28). Higher IGFBP-1 levels presumably related to lower insulin levels (29) in low-IGF subjects may result in even further reductions in free IGF-1 levels and bioactivity. Our findings suggest that in contrast to the pharmacological effects of rhIGF-1, the relationship between circulating IGF-1 levels and hepatic IS in healthy adults is not direct but possibly dependent on the overall effect of the GH/IGF-1 axis. We speculate that the increased hepatic IS in low-IGF subjects is a compensatory mechanism for the reduced insulin secretion. Increased insulin receptor numbers in liver as reported in lean growth-restricted or GH receptor KO mouse models (30, 31), which have enhanced IS but reduced insulin secretion, may explain the greater IS in low-IGF subjects. However, the levels of adiponectin, a mediator of increased IS associated with GH receptor mutations (31), were similar in the study groups.

Elevated FFA and β-hydroxybutyrate levels and trends for increased fat oxidation suggest enhanced mobilization and utilization of lipids in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects and is supported by the upregulation of relevant genes and metabolic pathways in skeletal muscle. Genes for the key regulators of β-oxidation were either significantly upregulated (malonyl coenzyme A decarboxylase [MYLCD] and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A [CPT1A]) or showed directional changes (hydroxyacyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase [HADH], acyl coenzyme A synthetase 1 [ACSL1], and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 [ALDH1]) (32, 33). A pronounced increase in β-hydroxybutyrate levels suggests upregulation of hepatic ketogenic pathways in low-IGF subjects. Although upregulation of the genes could reflect greater substrate availability (34), hormonal regulation of transcription and posttranscriptional modifications may also be important. Despite these differences between study groups, the absence of changes in glycerol Ra could be related to the inability of the technique to detect changes in splanchnic lipolysis (35).

IMCLs constitute a highly active storage pool and the main source of lipids for oxidation in skeletal muscle (36). Higher IMCLs in low-IGF subjects may reflect increased FFA levels (36, 37). Increased IMCLs in obesity and T2D is associated with reduced IS and is proposed to result from defective fat utilization related to impaired mitochondrial function (36). However, the trends for higher fat oxidation and upregulation of the related mitochondrial genes but no reductions in vivo mitochondrial function or peripheral IS suggest that increased IMCLs in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects signify enhanced lipid utilization in skeletal muscle during fasting.

Although GH is the key hormone driving metabolic responses to fasting (9, 38), significant differences in secretion were not observed. Although our study was underpowered to detect differences in pulsatile GH secretion, alterations in GH sensitivity could also be important in determining the metabolic responses. Whereas exogenous GH administration is associated with enhanced fat utilization, but reduced hepatic IS (38), the low-IGF subjects who showed increased fat metabolism had higher hepatic IS. We did not evaluate catecholamines, cortisol, or glucagon, which may also augment lipid metabolism during fasting. However, these hormones are less likely to be related to the metabolic changes we observed in low-IGF subjects because they reduce IS (38). We speculate that lower insulin levels resulting from reduced insulin secretion mediate an enhanced fasting response in low-IGF subjects.

The differences in substrate metabolism (12, 38) suggest a more efficient switching from glucose to fat metabolism in low-IGF compared with high-IGF subjects. These changes are consistent with physiological responses during fasting and may improve the tolerance of fasting (9). Furthermore, increased IMCL deposition provides an immediate energy source for skeletal muscles and is a potentially important adaptive mechanism during fasting (37). Yet, the reduced β-cell function could predispose the low-IGF subjects for early metabolic decompensation when exposed to nutrient overload and may underlie the associations between low IGF-1 levels and increased risk for T2D (6, 7).

Alterations in the GH/IGF-1 system have been proposed as a mechanism for the developmental programming which underlie the reduced statural growth and increased metabolic risks in low-birth-weight individuals (39). Changes similar to low-IGF subjects such as reduced insulin secretion but increased IS are reported in young growth-restricted animals, whereas worsening of glucose tolerance occurs later with increasing adiposity (30). SGA compared with normal-birth-weight children and neonates also have lower IGF-1 levels; higher FFA, β-hydroxybutyrate, and IGFBP-1 levels; and increased IS (40). Our findings that metabolic responses to fasting are linked to IGF-1 levels support the hypothesis that the GH/IGF-1 axis may be a mediator of adaptive programming during early life.

Whereas we have argued that low a IGF-1 level is a marker of reduced insulin secretion based on the observational data, the converse may be true (8). Further intervention studies using rhIGF-1 or a low GH dose may help to address the questions of reverse causality. Follow-up studies including assessment of insulin secretion and IS after an overnight fast would also be useful to characterize the subjects further because these parameters decrease with a prolonged fast (41).The main advantages of the study are selection of healthy subjects in the extremes of serum IGF-1 concentrations from a bioresource and blinded evaluation. However, our findings would need to be replicated in other studies, which should include females.

Conclusion

The associations of low IGF-1 levels with reduced insulin secretion but increased hepatic IS and enhanced fat metabolism during a fast suggest that IGF-1 levels could be an important marker of β-cell function and glucose as well as lipid metabolic responses during fasting. The potentially adaptive metabolic changes associated with low IGF-1 levels may result in increased risk for abnormal glucose metabolism when exposed to an excessive nutrient load and may reflect a thrifty phenotype.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to the study participants and the staff in the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research facility, Addenbrooke’s Hospital. We thank the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge BioResource and S. Nutland, the study coordinator in facilitating the recruitment. We gratefully acknowledge the participation of all NIHR Cambridge BioResource volunteers and thank the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre for the funding for the BioResource. We also thank A. Watts and K. Whitehead for the technical support and the Core Biochemical Assay Laboratory, NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre Laboratory for analysis of the samples. We are extremely grateful for the support of P. Raymond-Barker, P. R. Murgatroyd in body composition and calorimetry evaluations and M. K. Cheung for quantitative PCR evaluations. We thank Dr Ian Macfarlane (Genomics Core Lab, Cambridge NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK) for the microarray analysis, and Jo Weston for providing dietary advice.

A.T. received salary support from NIHR, Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and from Pfizer through an investigator-initiated research grant. The study was supported by research grants from Addenbrookes Charitable Trust and the British Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes.

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under the curve

- FFA

free fatty acid

- HOMA

homeostatic model assessment

- IGFBP-1

IGF binding protein-1

- IMCL

intramyocellular lipid

- IS

insulin sensitivity

- IVGTT

iv glucose tolerance test

- KO

knockout

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- OC

observed concentration

- Ra

rate of appearance

- rh

recombinant human

- REE

resting energy expenditure

- RQ

respiratory quotient

- SDS

SD score

- SGA

small for gestational age

- SI

insulin sensitivity index

- TA

tibialis anterior

- T2D

type 2 diabetes

Footnotes

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.LeRoith D, Yakar S. Mechanisms of disease: metabolic effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2007;3:302–310. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kulkarni RN, Holzenberger M, Shih DQ, et al. β-Cell-specific deletion of the Igf1 receptor leads to hyperinsulinemia and glucose intolerance but does not alter β-cell mass. Nat Genet. 2002;31:111–115. doi: 10.1038/ng872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet. 2010;42:105–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedrich N, Thuesen B, Jørgensen T, et al. The association between IGF-I and insulin resistance: a general population study in Danish adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:768–773. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sesti G, Sciacqua A, Cardellini M, et al. Plasma concentration of IGF-I is independently associated with insulin sensitivity in subjects with different degrees of glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:120–125. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandhu MS, Heald AH, Gibson JM, et al. Circulating concentrations of insulin-like growth factor-I and development of glucose intolerance: a prospective observational study. Lancet. 2002;359:1740–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08655-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajpathak SN, He M, Sun Q, et al. Insulin-like growth factor axis and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes. 2012;61:2248–2254. doi: 10.2337/db11-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shishko PI, Kovalev PA, Goncharov VG, Zajarny IU. Comparison of peripheral and portal (via the umbilical vein) routes of insulin infusion in IDDM patients. Diabetes. 1992;41:1042–1049. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.9.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Møller N, Jørgensen JO. Effects of growth hormone on glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism in human subjects. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:152–177. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dendrou CA, Plagnol V, Fung E, et al. Cell-specific protein pheno-types for the autoimmune locus IL2RA using a genotype-selectable human bioresource. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1011–1015. doi: 10.1038/ng.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen RB, Thankamony A, O’Connell SM, et al. Baseline IGF-I levels determine insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity during the first year on growth hormone therapy in children born small for gestational age. Results from a North European Multicentre Study (NESGAS) Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;80:38–46. doi: 10.1159/000353438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salgin B, Marcovecchio ML, Humphreys SM, et al. Effects of prolonged fasting and sustained lipolysis on insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in normal subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E454–E461. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90613.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elia M, Livesey G. Energy expenditure and fuel selection in biological systems: the theory and practice of calculations based on indirect calorimetry and tracer methods. World Rev Nutr Diet. 1992;70:68–131. doi: 10.1159/000421672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semple RK, Sleigh A, Murgatroyd PR, et al. Postreceptor insulin resistance contributes to human dyslipidemia and hepatic steatosis. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:315–322. doi: 10.1172/JCI37432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sleigh A, Raymond-Barker P, Thackray K, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in patients with primary congenital insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2457–2461. doi: 10.1172/JCI46405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salgin B, Marcovecchio ML, Williams RM, et al. Effects of growth hormone and free fatty acids on insulin sensitivity in patients with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3297–3305. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jovanovic Z, Tung YC, Lam BY, O’Rahilly S, Yeo GS. Identification of the global transcriptomic response of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus to fasting and leptin. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:915–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.02026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fontana L, Weiss EP, Villareal DT, Klein S, Holloszy JO. Long-term effects of calorie or protein restriction on serum IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 concentration in humans. Aging Cell. 2008;7:681–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrela M, Koistinen H, Kaprio J, et al. Genetic and environmental components of interindividual variation in circulating levels of IGF-I, IGF-II, IGFBP-1, and IGFBP-3. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:2612–2615. doi: 10.1172/JCI119081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verkauskiene R, Jaquet D, Deghmoun S, Chevenne D, Czernichow P, Levy-Marchal C. Smallness for gestational age is associated with persistent change in insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) and the ratio of IGF-I/IGF-binding protein-3 in adulthood. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5672–5676. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ong KK, Petry CJ, Emmett PM, et al. Insulin sensitivity and secretion in normal children related to size at birth, postnatal growth, and plasma insulin-like growth factor-I levels. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1064–1070. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chirieac DV, Chirieac LR, Corsetti JP, Cianci J, Sparks CE, Sparks JD. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion suppresses hepatic triglyceride-rich lipoprotein and apoB production. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279:E1003–E1011. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.5.E1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ciaraldi TP, Mudaliar S, Barzin A, et al. Skeletal muscle GLUT1 transporter protein expression and basal leg glucose uptake are reduced in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:352–358. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Díaz M, Vraskou Y, Gutiérrez J, Planas JV. Expression of rainbow trout glucose transporters GLUT1 and GLUT4 during in vitro muscle cell differentiation and regulation by insulin and IGF-1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R794–R800. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90673.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parekh N, Roberts CB, Vadiveloo M, Puvananayagam T, Albu JB, Lu-Yao GL. Lifestyle, anthropometric, and obesity-related physiologic determinants of insulin-like growth factor-1 in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988–1994) Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:182–193. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Succurro E, Andreozzi F, Marini MA, et al. Low plasma insulin-like growth factor-1 levels are associated with reduced insulin sensitivity and increased insulin secretion in nondiabetic subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19:713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibáñez L, López-Bermejo A, Díaz M, Marcos MV, Casano P, de Zegher F. Abdominal fat partitioning and high-molecular-weight adiponectin in short children born small for gestational age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1049–1052. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Semple RK, Cochran EK, Soos MA, et al. Plasma adiponectin as a marker of insulin receptor dysfunction: clinical utility in severe insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:977–979. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gosby AK, Maloney CA, Caterson ID. Elevated insulin sensitivity in low-protein offspring rats is prevented by a high-fat diet and is associated with visceral fat. Obesity. 2010;18:1593–1600. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.List EO, Sackmann-Sala L, Berryman DE, Funk K, et al. Endocrine parameters and phenotypes of the growth hormone receptor gene disrupted (GHR−/−) mouse. Endocr Rev. 2011;32:356–386. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watt MJ, Hoy AJ. Lipid metabolism in skeletal muscle: generation of adaptive and maladaptive intracellular signals for cellular function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;302:E1315–E1328. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00561.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziouzenkova O, Orasanu G, Sharlach M, et al. Retinaldehyde represses adipogenesis and diet-induced obesity. Nat Med. 2007;13:695–702. doi: 10.1038/nm1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cameron-Smith D, Burke LM, Angus DJ, et al. A short-term, high-fat diet up-regulates lipid metabolism and gene expression in human skeletal muscle. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:313–318. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen MD. Regional glycerol and free fatty acid metabolism before and after meal ingestion. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:E863–E869. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.5.E863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coen PM, Goodpaster BH. Role of intramyocelluar lipids in human health. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stannard SR, Johnson NA. Insulin resistance and elevated triglyceride in muscle: more important for survival than “thrifty” genes? J Physiol. 2004;554:595–607. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.053926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nørrelund H. The metabolic role of growth hormone in humans with particular reference to fasting. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2005;15:95–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hofman PL, Cutfield WS, Robinson EM, et al. Insulin resistance in short children with intrauterine growth retardation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:402–406. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.2.3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bazaes RA, Salazar TE, Pittaluga E, et al. Glucose and lipid metabolism in small for gestational age infants at 48 hours of age. Pediatrics. 2003;111:804–809. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salgin B, Marcovecchio ML, Humphreys SM, et al. Effects of prolonged fasting and sustained lipolysis on insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in normal subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E454–E461. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90613.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.