Abstract

Schizophrenia is one of the major psychiatric disorders. It is a disorder of complex inheritance, involving both heritable and environmental factors. DNA methylation is an inheritable epigenetic modification that stably alters gene expression. We reasoned that genetic modifications that are a result of environmental stimuli could also make a contribution.

We have performed 26 high-resolution genome-wide methylation array analyses to determine the methylation status of 27,627 CpG islands and compared the data between patients and healthy controls. Methylation profiles of DNAs were analyzed in six pools: 220 schizophrenia patients; 220 age-matched healthy controls; 110 female schizophrenia patients; 110 age-matched healthy females; 110 male schizophrenia patients; 110 age-matched healthy males. We also investigated the methylation status of 20 individual patient DNA samples (eight females and 12 males.

We found significant differences in the methylation profile between schizophrenia and control DNA pools. We found new candidate genes that principally participate in apoptosis, synaptic transmission and nervous system development (GABRA2, LIN7B, CASP3). Methylation profiles differed between the genders. In females, the most important genes participate in apoptosis and synaptic transmission (XIAP, GABRD, OXT, KRT7), whereas in the males, the implicated genes in the molecular pathology of the disease were DHX37, MAP2K2, FNDC4 and GIPC1. Data from the individual methylation analyses confirmed, the gender-specific pools results.

Our data revealed major differences in methylation profiles between schizophrenia patients and controls and between male and female patients. The dysregulated activity of the candidate genes could play a role in schizophrenia pathogenesis.

Keywords: DNA methylation, Schizophrenia, Whole genome arrays

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a severe psychiatric disorder, characterized by debilitating behavioral abnormalities, delusions, hallucinations and negative symptoms [1]. It is an etiologically complex disorder, involving both heritable and non heritable factors, with heritability estimates of up to 81.0% [2]. It is believed that the disorder is due to early neurodevelopmental factors, imbalances in neurotransmitter signaling, together with obstetric complications, infections, stress and trauma [3,4]. In the absence of established diagnostic biological markers, diagnosis of schizophrenia relies on examination of mental state by a clinical interview [5]. DNA methylation is a basic epigenetic modification, important for normal development in higher organisms. It alters the gene expression without modification of the primary DNA sequence and is heritable through the cell [6]. It involves conversion of the cytosine to 5-methylcytosine by means of DNA methyltransferases [6]. In eukaryotes, methylation is most commonly found in CG rich areas of DNA, called CpG islands [7]. The epigenetic processes are dynamic and allow the cells to respond reversibly and in a precise way to environmental stimuli, but also preserve cell type specific gene programs. Epigenetic changes over time display familial clustering [8]. This could explain the clustering of some common diseases in families, so the epigenetic pattern could be implicated in transmitting “predisposition” over generations.

DNA methylation can be associated with the transcription start sites of genes or can be found in the gene bodies, intergenic or in distant regulatory regions. The position of the methylation affects its relationship to gene expression level. Methylation in the immediate vicinity of the transcription start site blocks initiation, while methylation inside the gene stimulates transcription elongation. So it is suggested that gene body methylation may have an effect on splicing. It is supposed that the methylation in repetitive regions is important for chromosomal and genomic stability, and probably represses transposable element expression. Yet the role of DNA methylation in modifying the action of regulatory elements such as enhancers is not well established [9,10].

There is evidence of DNA methylation aberrations in a wide variety of brain disorders such as mental retardation, Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes, fragile X syndrome, gliomas and neuroectodermal tumors. Yet there are no conclusive studies about DNA methylation in major psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [11,12].

Studies of the Bulgarian schizophrenia population have implicated common and rare genetic factors [13–16]. Here we use the same large clinical cohort and propose a role of epigenetic modifiers of gene expression in the development and progression of the disease and use cohort.

Epidemiological data as variable age of onset between males and females, advanced paternal age, in utero nutritional deficiency, viral exposure and hypoxia, support the importance of “epigenetic” modifications. Because of the dynamic nature and potential reversibility of DNA methylation, the study of its mechanisms is very important for clinical psychiatry and for identifying new targets for prevention and intervention. The aim of our study was to investigate the whole genome methylation profile to find specific differentially methylated regions (DMRs) for schizophrenia patients. We tried to find gender-specific differences in methylation pattern. Here we report our best candidate genes with DMRs for association with schizophrenia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We have examined the methylation status of Bulgarian patients with schizophrenia compared to sex - and age-matched healthy controls. We analyzed methylation profiles of DNAs in six pools, consisting of: 1) general pool of 220 schizophrenia patients [110 males with a mean age of 42 years, standard deviation (SD) = 11, and 110 females, aged 45, SD = 11 years]; 2) general pool of 220 healthy controls (110 males aged 50 years, SD = 14 and 110 females aged 51 years. SD = 14); 3) a pool of 110 female cases (the same female patients from the general pool); 4) a pool of 110 healthy females (the same female controls from the general pool); 5) a pool of 110 male cases (the same male patients from the general pool); 6) a pool of 110 healthy males (the same male controls from the general pool).

We also investigated methylation status of 20 individual schizophrenia patient DNA samples (eight females and 12 males). Informed consent was obtained from all investigated subjects and the relevant Ethics Committees of the hospitals where subjects were recruited gave approval for the use of these samples in genetic studies. The diagnosis of schizophrenia was made by experienced psychiatrists, according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV) criteria on the basis of extensive clinical interviews [15].

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood by the phenol-chloroform extraction method. Concentration and purity were determined on all DNA samples (NanoDrop 2000C; Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). All samples were tested electrophoretically to verify the integrity of DNA. Six DNA pools were constructed using equal amount of DNA (at 100 ng/μL) from each patient/control samples and placing them in a single tube-pool [17]. We based our DNA methylation profiling strategy on a recently developed technique, methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP), which utilizes a monoclonal antibody against 5-methylcytosine to enrich the methylated fraction of a genomic DNA sample [18,19].

Genome-wide DNA methylation was assessed using the Agilent Human DNA Methylation Microarray (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) platform. We used oligonucleotide microarrays (1 × 244K, density 237,227 sequences covering 27,627 CpG). All included arrays passed standard quality control metrics. Agilent methylation microarrays were scanned, using Agilent High-Resolution Microarray Scanner G2505 with a resolution of 2 μm. Scans were performed with 532 nm wavelength of green laser and 635 nm for red laser. The resulting .tif images were processed with the Agilent Feature Extraction 11.0.1.1 and Agilent Workbench 6.5.0.18 software, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. These software products gave the position of the CpG island in the gene structure: promoter, intragenic, downstream, divergent promoter.

Since such studies are still new there are no universally accepted algorithms for analysis of results. According to the latest data, the most suitable algorithm for the methylation analysis of immunoprecipitated DNA is the Bayesian tool for methylation analysis (BATMAN) [20]. BATMAN enabled the estimation of absolute methylation levels from immunoprecipitation-based DNA methylation profiles. This parameter can have the following values: −1 (hypomethylation), 1 (hypermethylation) or 0 (uninterpretable) [20]. For further analysis, we developed a software program to interpret the obtained methylation profiles data. It was designed to estimate the methylation status of one CpG island at a time and to compare island methylation status across arrays in search for differently methylated regions. The methylation status is based on the percentage of methylated probes in the island. The differently methylated islands list is generated in a separate table. Genes with uninterpretable results were excluded from the analysis. According to the literature, when over 60.0% of a CpG island is methylated, it is defined as “methylated” and if <40.0% of a CpG island is methylated, it is considered as “unmethylated.” CpG islands with a methylation status in the range 40.0–60.0% are considered as “intermediate” and were excluded from further analysis [20]. For further analysis of all genes with DMRs revealed from pool analysis (726) we used online data mining service (Biograph; http://biograph.be/). It was very helpful in identification of susceptibility genes, because it used different databases and analyses functional relations in order to rank the genes according to their relevance in disease etiopathogenesis [21]. There are literature data for some of the genes about association with the disease so they are defined as “known.” For other genes, the relation to the disease was not proved, so they were defined as “inferred.”

RESULTS

The threshold between hypo - or hypermethylated islands was 60.0% of the oligonucleotide sequences with BATMAN, call −1 or 1, respectively. By comparing data from the pool analysis of patients and controls (220 each) we obtained 394 DMRs. We found 170 DMRs in the pooled analysis of male patients and controls (110 each) and 162 DMRs in the pooled analysis of female patients and controls (110 each). The results of DMRs pool analysis between patients and controls are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of differentially methylated regions according to methylation status and location of the CpG island in three patient pools and three control pools.

| Description of DMRs | General Pool (n = 394 DMRs) | Female Pool (n = 162 DMRs) | Male Pool (n = 170 DMRs) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of all DMRs | n | % of all DMRs | n | % of all DMRs | |

| Hypermethylated CpG Island | ||||||

| Promoter | 96 | 24.4 | 52 | 32.1 | 24 | 14.1 |

| Intragenic | 112 | 28.4 | 86 | 53.1 | 40 | 23.5 |

| Downstream | 10 | 2.5 | 6 | 3.7 | 6 | 3.5 |

| Divergent promoter | 12 | 3.0 | 12 | 7.4 | 3 | 1.8 |

| Hypomethylated CpG Island | ||||||

| Promoter | 50 | 12.7 | 3 | 1.9 | 33 | 19.4 |

| Intragenic | 99 | 25.1 | 2 | 1.2 | 57 | 33.5 |

| Downstream | 9 | 2.3 | 1 | 0.6 | 4 | 2.4 |

| Divergent promoter | 6 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.8 |

DMRs: differentially methylated regions.

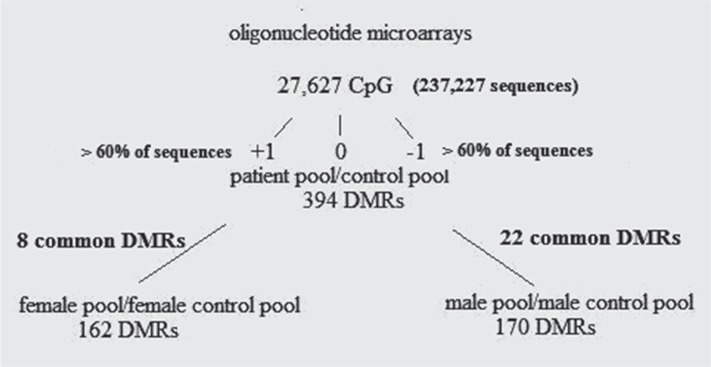

Comparing the 394 DMRs of the general pool with the 170 DMRs in the male pool we found a coincidence of 36 DMRs. Twentytwo of them a were methylated in the same direction, while the other 14 were methylated in different directions. Ten of the 22 DMRs were situated in the gene promoter region, while the other 12 were intragenic. The comparison of the general (394 DMRs) to the female pool (162 DMRs) showed 25 common DMRs. Eight of them were methylated in the same direction (two in the promoters and six intragenic) and 17 had a different methylation status (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sequential analysis of array data by comparing general pool to male and female pools.

There are multiple reports in the literature confirming the negative effect of hypermethylation of CpG islands in the promoter regions on gene expression level. So far, the effect of methylation of CpG islands inside the gene or within other regulatory regions has not been considered and should be interpreted on a case-by-case basis. According to some authors this should be considered as a suppressing signal, while others propose that it is an activating function. We found that in the three groups, location of most of the DMRs were defined as intragenic. Very interestingly, in the female pool, the number of hypermethylated CpG islands was considerably greater than that of hypomethylated CpG islands (96.3 vs. 3.7%).

Using the Biograph software, we prioritized the genes that could be related to schizophrenia. Table 2 shows the top 10 genes with different methylation profiles in the general pool.

Table 2.

Top 10 differentially methylated regions, chosen by Biograph software in schizophrenia patients.

| Top 10 DMRs in Schizophrenia Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Name | CpG Island | Chromosome | Cytoband | Localization | Methylation Status (%) |

| HRH1 | CpG: 83 | chromosome 3 | p25.3 | promoter | hyper (60.0) |

| GABRA2 | CpG: 65 | chromosome 4 | p12 | promoter | hyper (67.0) |

| LIN7B | CpG: 115 | chromosome 19 | q13.33 | promoter | hyper (60.0) |

| MYLIP | CpG: 113 | chromosome 6 | p22.3 | promoter | hyper (63.0) |

| NXPH3 | CpG: 32 | chromosome 17 | q21.33 | promoter | hyper (67.0) |

| HMOX1 | CpG: 34 | chromosome 22 | q12.3 | promoter | hypo (75.0) |

| CRMP1 | CpG: 137 | chromosome 4 | p16.2 | promoter | hypo (60.0) |

| FGFR1 | CpG: 170 | chromosome 8 | p11.22 | intragenic | hyper (63.0) |

| CASP3 | CpG: 59 | chromosome 4 | q35.1 | intragenic | hyper (60.0) |

| MACF1 | CpG: 78 | chromosome 1 | p34.3 | intragenic | hypo (60.0) |

DMRs: differentially methylated regions.

Our data showed that most of the CpG islands were situated in the gene promoter region (seven out of 10 CpG islands). Five of the islands in promoter region were hypermethylated, while two were hypomethylated. It is believed that hypermethylation in the promoter region leads to expression inhibition, whereas hypomethylation leads to expression activation [9]. Thus, it appears that most of the top hit genes were repressed. Only three gene CpG islands were located intragenically. Two of them were hypermethylated, while one was hypomethylated. The real function of methylation in areas other than promoters is uncertain [9,10]. So we can only speculate about its effect on gene expression. In the general pool, only two genes (HRH1 and FGFR1) from 394 with DMRs are of known relation with schizophrenia according to data in the Biograph software and the others are inferred. The GABRA2 gene plays a role in inhibitory neuro-transmission but is defined as inferred in regards to schizophrenia according to the Biograph software [22].

It is known that there are gender differences in methylation [23,24]. So we decided to study DMRs in sex-separated patient and control pools. Table 3 shows the top 10 DMRs, chosen by Biograph software, from 170 genes with a different methylation profile in pool analysis of male patients vs. male controls and Table 4 shows the top 10 genes with a different methylation profile in schizophrenia females.

Table 3.

Top 10 differentially methylated regions, chosen by Biograph software in schizophrenia male patients and distribution in individual samples.

| Top 10 DMRs in 110 Male Schizophrenia Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 10 Genes with DMRs in Male Pool | DMRs in Individual Male Patients (n) | % | CpG Island | Localization | Methylation Status (%) |

| GABRA2 | 3 | 25.0 | CpG: 65 | promoter | hyper (83.0) |

| LIN7B | 6 | 50.0 | CpG: 115 | promoter | hyper (60.0) |

| MIR193B | 2 | 17.0 | CpG: 123 | promoter | hyper (63.0) |

| MIR181C | 6 | 50.0 | CpG: 117 | promoter | hypo (63.0) |

| DNMT3A | 5 | 42.0 | CpG: 61 | intragenic | hyper (60.0) |

| CASP3 | 3 | 25.0 | CpG: 59 | intragenic | hyper (60.0) |

| DHX37 | 7 | 59.0 | CpG: 35 | intragenic | hypo (80.0) |

| GIPC1 | 7 | 59.0 | CpG: 59 | intragenic | hypo (67.0) |

| MAP2K2 | 8 | 67.0 | CpG: 83 | intragenic | hypo (60.0) |

| FNDC4 | 7 | 59.0 | CpG: 59 | intragenic | hypo (60.0) |

DMRs: differentially methylated regions.

Table 4.

Top 10 differentially methylated regions, chosen by Biograph software in schizophrenia female patients and distribution in individual samples.

| Top 10 DMRs in 110 Female Schizophrenia Patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top 10 Genes with DMRs in Female Pool | DMRs in Individual Female Patients (n) | % | CpG Island | Localization | Methylation Status (%) |

| GABRD | 5 | 63.0 | CpG: 117 | promoter | hyper (60.0) |

| GNAQ | 2 | 25.0 | CpG: 167 | promoter | hyper (60.0) |

| PTK2 | 1 | 13.0 | CpG: 170 | promoter | hyper (63.0) |

| XIAP | 7 | 88.0 | CpG: 70 | promoter | hyper (80.0) |

| PRKACA | 4 | 50.0 | CpG: 80 | promoter | hypo (60.0) |

| CASP3 | 1 | 13.0 | CpG: 59 | intragenic | hyper (60.0) |

| OXT | 5 | 63.0 | CpG: 105 | intragenic | hyper (75.0) |

| MACF1 | 4 | 50.0 | CpG: 78 | intragenic | hyper (80.0) |

| PPP2R2A | 3 | 38.0 | CpG: 56 | intragenic | hyper (60.0) |

| KRT7 | 5 | 63.0 | CpG: 89 | downstream | hyper (60.0) |

DMRs: differentially methylated regions.

Four of the genes show differential methylation in the promoter CpG islands. Three of them were hypermethylated and one was hypomethylated. The other six gene CpG islands were intragenic. Three of the top hits in the male pool were identical with the genes in the general pool and also hypermethylated: GABRA2, LIN7B, CASP3.

Five of all CpG islands were located in the promoter areas, four were intragenic and one was downstream of the promoter. Most of the CpG islands in the female pool were hypermethylated (nine of 10). Two of those were identical with the genes from the general pool: CASP3, MACF1. However, the MACF1 gene had a DMR that was hypermethylated in females and hypomethylated in the general pool and was therefore not a consistently implicated one. In the male patient pool, this gene did not show differently methylated regions in comparison with the male control pool. In the female pool, the GABRD gene was of known relevance to schizophrenia [25]. The CASP3 gene was found to be in the top 10 genes from the three pools.

For confirmation of data from gender-specific pools, we performed individual analyses on eight female and 12 male schizophrenia samples. The patient samples were compared to the control pool of the corresponding gender.

In the individual analysis of seven female samples, we found the entire top 10 DMRs from the female pool analysis differentially methylated in the same direction in between one and seven patients (Table 3). The most frequent XIAP promoter DMR was found in seven of the eight patients. Another three DMRs in GABRD, OXT and KRT7 genes are found in five of the eight analyzed patients. Therefore, we propose that these genes are strong candidates for schizophrenia biomarkers. These results confirm the data received from pool analysis and enabled the usage of pools as a tool for epigenetic analysis.

In the 12 male patients, we detected all top 10 DMRs specific for the male pool, present in between two and eight patients (Table 4). The CpG islands had the same localization and methylation status. One of the top 10 genes (MAP2K2) was found in eight of 12 patients. Three of these genes with different methylated regions, DHX37, GIPC1 and FNDC4, occurred in seven of the 12 patients (7). Another two genes, MIR181C and LIN7B, were found in six of the 12 analyzed patients [6].

These data confirm our pool results in a subset of individual patients included in the pool. We therefore propose that gender-specific pools are more informative than general pools and that these can be used for determination of new biomarkers.

DISCUSSION

The aim of our study was to perform microarray-based genome-wide methylation analysis of blood DNA samples to search for new specific biomarkers for schizophrenia in the Bulgarian population. There are very few articles regarding whole-genome methylation analysis [26,27]. Most of the differentially methylated genes in our study were involved in synaptic transmission and nervous system development. The HRH1 and FGFR1 genes have been implicated in schizophrenia, whereas the remaining genes were novel candidates [28–31].

The MYLIP, CRMP1 and FGFR1 genes are involved in nervous system development [32–37]. A comparison between the general and male pool found three genes in common: GABRA2, LIN7B, CASP3, while the comparison of the general and female pool found two common genes (CASP3, MACF1) but one was methylated in the opposite direction (MACF1). These could represent candidate genes and biomarkers for schizophrenia. All of them are involved in synaptic transmission. Among the top 10 genes from the three pools, one is common to all three: CASP3. The CASP3 gene participates in cell apoptosis. It is hypermethylated inside, so we propose that it is activated. Thus, our results can explain the apoptotic mechanism in schizophrenia pathophysiology [38–40]. The CASP3 gene participates in serotonin and glutamate neurotransmission regulation [41,42].

For finding gender-specific differences, we compared the top 10 genes in gender-specific pools and corresponding individual samples. We found all of the top 10 genes being differentially methylated in at least some of the individual patients. The most convincing candidates were those found in around half or more of the patients.

The top 10 genes from the female pool were involved in apoptosis, synaptic transmission, neuron development and axon guidance. Four of them showed different methylation regions in more than half of the patients: XIAP, GABDR, OXT and KRT7.

In our study, the CpG island of the XIAP gene was hypermethylated in the promoter region and maybe it was suppressed. Inactivation of the XIAP gene activates CASP3 and apoptosis [43]. The GABRD gene is of known relation to schizophrenia [25]. We found hypermethylation in the promoter region, which was a possible mechanism for involvement of GABRD inactivation in the disease pathogenesis. The CpG island of OXT was hypermethylated intragenically. Previous findings showed significantly increased mRNA in melancholic patients [44]. We supposed that OXT hypermethylation activates the gene and could play a role in schizophrenia. It is difficult to interpret the connection between KRT7 expression and downstream hypermethylation, moreover data in the literature were insufficient.

Four genes from the top 10 in the male pool were found to be differentially methylated in over 50.0% of individual male patients: DHX37, MAP2K2, FNDC4 and GIPC1, therefore these were considered the best candidates. They had CpG islands with different methylation regions that were hypomethylated.

Their methylation status was difficult to interpret. The function of FNDC4 is still unknown. The MAP2K2 gene belongs to the MAP kinase kinase family. It activates MAPK1/ERK2 and MAPK2/ERK3 that are related to synaptic plasticity, cell survival, learning and memory [45]. The DHX37 gene showed helicase activity [21]. The GIPC1 gene participates in BDNF-mediated neurotransmission and neurite outgrowth [46,47]. There are no data in the literature about the role of these four genes in schizophrenia. We hypothesized that they are new candidate genes for schizophrenia in males due to their different methylation profiles.

CONCLUSIONS

In our study, we performed genome-wide methylation analyses, based on pool and individual samples. As a result we proposed several new schizophrenia candidate genes that principally participate in synaptic transmission and nervous system development. The most likely candidate gene is CASP3, which is involved in apoptosis and plays a role in the regulation of neurotransmission.

As there could be gender-specific differences, we tested the genders separately and found the XIAP, GABRD, OXT and KRT7 genes to be the most likely candidates in the female group. In the male pool, the main genes of interest were DHX37, MAP2K2, FNDC4 and GIPC1. According to these data we extended the hypothesis that there are differences in the mechanism of disease development in males and females.

Our data revealed major differences in methylation profile between schizophrenia patients and controls and between male and female patients. The dysregulated activity of revealed candidate genes could play a critical role in schizophrenia pathogenesis.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest. This study was funded by the Bulgarian National Science Fund (BNSF) grant DMY O3/36-12.12.2011, DO02-12/10.02.2009 and DTK 02/76-21.12.2009. The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsuang MT, Faraone SV, Glatt SJ. Schizophrenia. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan PF, Kendler KS, Neale MC. Schizophrenia as a complex trait: evidence from a meta-analysis of twin studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(12):1187–1192. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stilo SA, Murray RM. The epidemiology of schizophrenia: replacing dogma with knowledge. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2010;12(3):305–315. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2010.12.3/sstilo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Os J, Kapur S. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2009;374(9690):635–645. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turck CW, Maccarrone G, Sayan-Ayata E, Jacob AM, Ditzen C, Kronsbein H, et al. The quest for brain disorder biomarkers. J Med Invest. 2005;52(Suppl):231–235. doi: 10.2152/jmi.52.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bird A. Perceptions of epigenetics. Nature. 2007;447(7143):396–398. doi: 10.1038/nature05913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bird AP. CpG-rich islands and the function of DNA methylation. Nature. 1986;321(6067):209–213. doi: 10.1038/321209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjornsson HT, Sigurdsson MI, Fallin MD, Irizarry RA, Aspelund T, Cui H, et al. Intra-individual change over time in DNA methylation with familial clustering. JAMA. 2008;299(24):2877–2883. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.24.2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones PA. Functions of DNA methylation: Islands, start sites, gene bodies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13(7):484–492. doi: 10.1038/nrg3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA Methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):23–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rakyan VK, Down TA, Thorne NP, Flicek P, Kulesha E, Graf S, et al. An integrated resource for genome-wide identification and analysis of human tissue-specific differentially methylated regions (tDMRs) Genome Res. 2008;18(9):1518–1529. doi: 10.1101/gr.077479.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor CM, Akbarian S. DNA methylation changes in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Epigenetics. 2008;3(2):55–58. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.2.5938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betcheva ET, Mushiroda T, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Karachanak SK, Zaharieva IT, et al. Case-control association study of 59 candidate genes reveals the DRD2 SNP rs6277 (C957T) as the only susceptibility factor for schizophrenia in the Bulgarian population. J Hum Genet. 2009;54(2):98–107. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2008.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Consortium TIS. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460(7256):748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirov G, Pocklington AJ, Holmans P, Ivanov D, Ikeda M, Ruderfer D, et al. De novo CNV analysis implicates specific abnormalities of postsynaptic signalling complexes in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(2):142–153. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raychaudhuri S, Korn JM, McCarroll SA, Altshuler D, Sklar P, Purcell S, et al. Accurately assessing the risk of schizophrenia conferred by rare copy-number variation affecting genes with brain function. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(9):e1001097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaharieva I, Georgieva L, Nikolov I, Kirov G, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, et al. Association study in the 5q31-32 linkage region for schizophrenia using pooled DNA genotyping. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weber M, Davies JJ, Wittig D, Oakeley EJ, Haase M, Lam WL, et al. Chromosome-wide and promoter-specific analyses identify sites of differential DNA methylation in normal and transformed human cells. Nat Genet. 2005;37(8):853–862. doi: 10.1038/ng1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia J, Pekowska A, Jaeger S, Benoukraf T, Ferrier P, Spicuglia S. Assessing the efficiency and significance of Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP) assays in using in vitro methylated genomic DNA. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:240. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Down TA, Rakyan VK, Turner DJ, Flicek P, Li H, Kulesha E, et al. A Bayesian deconvolution strategy for immunoprecipitation-based DNA methylome analysis. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(7):779–785. doi: 10.1038/nbt1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liekens AM, De Knijf J, Daelemans W, Goethals B, De Rijk P, Del-Favero J. BioGraph: unsupervised biomedical knowledge discovery via automated hypothesis generation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6):R57. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe M, Kanbara K. GABA and GABA Receptors in the Central Nervous System and Other Organs, vol. 213. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Morgan M, Hutchison K, Calhoun VD. A study of the influence of sex on genome wide methylation. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canuso CM, Pandina G. Gender and schizophrenia. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2007;40(4):178–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bullock WM, Cardon K, Bustillo J, Roberts RC, Perrone-Bizzozero NI. Altered expression of genes involved in GABAergic transmission and neuromodulation of granule cell activity in the cerebellum of schizophrenia patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(12):1594–1603. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07121845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishioka M, Bundo M, Koike S, Takizawa R, Kakiuchi C, Araki T, et al. Comprehensive DNA methylation analysis of peripheral blood cells derived from patients with first-episode schizophrenia. J Hum Genet. 2013;58(2):91–97. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2012.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dempster EL, Pidsley R, Schalkwyk LC, Owens S, Georgiades A, Kane F, et al. Disease-associated epigenetic changes in monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Hum Molec Genet. 2011;20(24):4786–4796. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakai T, Kitamura N, Hashimoto T, Kajimoto Y, Nishino N, Mita T, et al. Decreased histamine H1 receptors in the frontal cortex of brains from patients with chronic schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 1991;30(4):349–356. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee ST, Ryu S, Kim SR, Kim MJ, Kim S, Kim JW, et al. Association study of 27 annotated genes for clozapine pharmacogenetics: validation of preexisting studies and identification of a new candidate gene, ABCB1, for treatment response. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(4):441–448. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31825ac35c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vehof J, Risselada AJ, Al Hadithy AF, Burger H, Snieder H, Wilffert B, et al. Association of genetic variants of the histamine H1 and muscarinic M3 receptors with BMI and HbA1c values in patients on antipsychotic medication. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2011;216(2):257–265. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2211-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaughran F, Payne J, Sedgwick PM, Cotter D, Berry M. Hippocampal FGF-2 and FGFR1 mRNA expression in major depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Brain Res Bull. 2006;70(3):221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bader V, Tomppo L, Trossbach SV, Bradshaw NJ, Prikulis I, Leliveld SR, et al. Proteomic, genomic and translational approaches identify CRMP1 for a role in schizophrenia and its underlying traits. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(20):4406–4418. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bornhauser BC, Olsson PA, Lindholm D. MSAP is a novel MIR-interacting protein that enhances neurite outgrowth and increases myosin regulatory light chain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(37):35412–35420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306271200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamajima N, Matsuda K, Sakata S, Tamaki N, Sasaki M, Nonaka M. A novel gene family defined by human dihydropyrimidinase and three related proteins with differential tissue distribution. Gene. 1996;180(1–2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsson PA, Korhonen L, Mercer EA, Lindholm D. MIR is a novel ERM-like protein that interacts with myosin regulatory light chain and inhibits neurite outgrowth. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(51):36288–36292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soundararajan P, Fawcett JP, Rafuse VF. Guidance of postural motoneurons requires MAPK/ERK signaling downstream of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. J Neurosci. 2010;30(19):6595–6606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4932-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamashita N, Uchida Y, Ohshima T, Hirai S, Nakamura F, Taniguchi M, et al. Collapsin response mediator protein 1 mediates reelin signaling in cortical neuronal migration. J Neurosci. 2006;26(51):13357–13362. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4276-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarskog LF, Glantz LA, Gilmore JH, Lieberman JA. Apoptotic mechanisms in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(5):846–858. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerns D, Vong GS, Barley K, Dracheva S, Katsel P, Casaccia P, et al. Gene expression abnormalities and oligodendrocyte deficits in the internal capsule in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;120(1–3):150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Catts VS, Catts SV, McGrath JJ, Féron F, McLean D, Coulson EJ, et al. Apoptosis and schizophrenia: A pilot study based on dermal fibroblast cell lines. Schizophr Res. 2006;84(1):20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boston-Howes W, Gibb SL, Williams EO, Pasinelli P, Brown RH, Trotti D. Caspase-3 cleaves and inactivates the glutamate transporter EAAT2. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(20):14076–14084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600653200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sari Y, Zhou FC. Prenatal alcohol exposure causes long-term serotonin neuron deficit in mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28(6):941–948. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128228.08472.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Riedl SJ, Renatus M, Schwarzenbacher R, Zhou Q, Sun C, Fesik SW, et al. Structural basis for the inhibition of Caspase-3 by XIAP. Cell. 2001;104(5):791–800. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meynen G, Unmehopa UA, Hofman MA, Swaab DF, Hoogendijk WJ. Hypothalamic oxytocin mRNA expression and melancholic depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(2):118–119. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kyosseva SV. The role of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway in cerebellar abnormalities in schizophrenia. Cerebellum. 2004;3(2):94–99. doi: 10.1080/14734220410029164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin DC, Quevedo C, Brewer NE, Bell A, Testa JR, Grimes ML, et al. APPL1 Associates with TrkA and GIPC1 and is required for nerve growth factor-mediated signal transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(23):8928–8941. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00228-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yano H, Ninan I, Zhang H, Milner TA, Arancio O, Chao MV. BDNF-Mediated neurotransmission relies upon a myosin VI motor complex. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(8):1009–1018. doi: 10.1038/nn1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]