Abstract

Although several genetic causes of male infertility are known, the condition in around 60.0–75.0% of infertile male patients appears to be idiopathic. In some, genetic causes may be polygenic and require several low-penetrance genes to produce a phenotype outcome. In others, pleiotropy, when a gene can produce several phenotypic traits, may be involved. We have investigated whether single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the SLC6A14 [solute carrier family 6 (amino acid transporter), member 14] gene are associated with male infertility. This gene has previously been linked with obesity and cystic fibrosis, which are associated with male infertility. It has a role in the transport of tryptophan and synthesis of serotonin that are important for normal spermatogenesis and testicular function. We have analyzed three SNPs (rs2312054, rs2071877 and rs2011162) in 370 infertile men and 241 fertile controls from two different populations (Macedonian and Slovenian). We found that the rs2011162(G) allele and rs2312054(A)-rs2071877(C)-rs2011162(G) haplotype are present at lower frequencies in the infertile rather than the fertile men (p = 0.044 and p = 0.0144, respectively).

We concluded that the SLC6A14 gene may be a population-specific, low-penetrance locus which confers susceptibility to male infertility/subfertility. Additional follow-up studies of a large number of infertile men of different ethnic backgrounds are needed to confirm such a susceptibility.

Keywords: Male infertility, rs2011162, SLC6A14 gene, 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR)

INTRODUCTION

Spermatogenesis is a complex biological process that involves mitosis, meiosis and spermiogenesis, that are under endocrine and paracrine regulation [1]. Many genes are specifically transcribed only during these processes and reduction or absence in their expression could lead to infertility or subfertility. Well-known genetic causes of male infertility include sex chromosome aneuploidies, Y chromosome AZF microdeletions and mutations in the CFTR and AR genes [2,3], but 60.0–75.0% of patients with male infertility appear to be idiopathic [4]. Besides genes that are directly involved and expressed during spermatogenesis in testicular tissue, others are ubiquitously transcribed during normal functioning of cells and genetic variation and impairment in their expression could lead to disruption of spermatogenesis. Pleiotropy, in which a gene has an effect on multiple phenotype traits [5] and variation in the gene could lead to different effects on each of these, is also possible. Moreover, genetic variation in several genes could combine as low-penetrant risk alleles and contribute to the phenotype outcome.

We have previously investigated the association of nine single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in eight different genes with idiopathic male infertility on the basis of one genome-wide association study [6]. Our findings confirmed the association of SNPs rs5911500 in LOC203413, rs3088232 in BRDT and rs11204546 in OR2W3, in oligo-zoospermic and azoospermic men with infertility and of different ethnicity (Macedonians and Albanians) [7]. A minor allele of rs5911500 in LOC203413 retained strong association when we enlarged the group to include Slovenian males. This SNP on the long arm of chromosome X (Xq23) is in close proximity to the SLC6A14 (NM_007231.4) gene, which is a member of the solute carrier family 6 that transports neutral and cationic amino acids in a sodium- and chloride-dependent manner. It contains 14 exons and spans 29 kb [8]. The SNPs in this gene have been associated with obesity [9–11] and meconium illeus (a known clinical manifestation of cystic fibrosis) [12]. There is also evidence of pleiotropic effects of the SLC6A14 gene in other CF-related morbidities [13]. The SLC6A14 gene has high affinity for several amino acids, including tryptophan [8], and could be involved in regulation of tryptophan availability for serotonin synthesis [9]. In fact, serotonin has been shown to be necessary for normal spermatogenesis in prepubertal rats [14]. An association has also been demonstrated between serotonin and testosterone production [15], and between testicular blood flow and vasomotion [16] in rats. This study investigated the possible association of three SNPs (rs2312054, rs2071877 and rs2011162) in the SLC6A14 gene with idiopathic male infertility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Samples

A total of 370 infertile males (247 from Slovenia and 123 from Macedonia) and 237 fertile controls (114 from Slovenia and 127 from Macedonia) were studied. The infertile group consisted of 137 patients with idiopathic azoospermia (87 from Slovenia and 50 from Macedonia) and 243 with oligozoospermia (160 from Slovenia and 73 from Macedonia). Patients with sex chromosome aneuploidies and Y chromosome AZF microdeletions were excluded from the study. Fertile controls have fathered at least one child and their paternity was proven by DNA analysis. Informed consent was obtained from all men and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia.

DNA Isolation

DNA was isolated from peripheral blood using the standard phenol/chloroform protocol.

Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction

The PCR primers were designed to produce different PCR fragment sizes, so as to make their separation by aga-rose gel electrophoresis possible. Primer sequences for PCR amplification of the three SLC6A14 SNPs are as shown in Table 1. Polymerase chain reaction multiplexes were performed in a final volume of 20 μL, containing: 10 × KLA buffer [50 mM Tris base, 16 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 9.2], 25 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM dNTPs, 10 pmol of each primer, Tth DNA polymerase and approximately 100 ng of genomic DNA. The cycling conditions were: 2 min. 95 °C initial denaturation, followed by 28 cycles of 40 seconds at 95 °C, 40 seconds at 59 °C, 45 seconds at 72 °C, and final elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. A rapid thermal ramp at 4 °C followed and the PCR products obtained were analyzed with electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Table 1.

Sequences and sizes of primers used for the polymerase chain reaction.

| SNPs | Primer Name | Sequence (5′>3′) | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs2312054 (A/T) | rs2312054-F rs2312054-R |

GTG GAG GAC CTG AGA GTG GA GGA GGG TTC TTT GGG TCA AT |

296 |

| rs2071877 (C/T) | rs2071877-F rs2071877-R |

TGC ATG TGT GTT TTT GAT GTG AAT CAG GTA ACA AGC CAG AAG A |

396 |

| rs2011162 (C/G) | rs2011162-F rs2011162-R |

GGG GAA CCT TAT TTA TTT GTG TG GCC TCC AAT GTA TTA AAA ATG C |

250 |

Multiplex SNaPshot Analysis

Before performing the SNaPshot reaction, 1 μL of PCR product was treated with 0.6 μL of ExoSAP-IT (Exonuclease I and Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase; USB Corporation, Clevelend, OH, USA) at 37 °C for 2 hours or overnight. The reaction mixture was incubated at 86 °C for 20 min. to inactivate the ExoSAP-IT. The purified PCR products were used as templates to detect the three polymorphic positions in the SLC6A14 gene. The detection primers were mixed with final concentration of 1 pmol/μL each. Multiplex single base extension reactions were performed in a 4.6 μL final volume, combining 1 μL of SNaPshot Multiplex Ready Reaction Mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1 μL of deionized H2O, 1.6 μL of purified PCR product and 1 μL (1 pM) SNaPshot primer cocktail. The minisequencing primers were 5′-tailed with a polyT sequence to produce extension products 25, 30 and 35 nucleotides long to allow separation by capillary electrophoresis (Table 2). Cycling conditions were: 25 cycles of 10 seconds at 96 °C, 10 seconds at 50 °C and 30 seconds at 60 °C, followed by rapid thermal ramp to 4 °C. To remove unincorporated fluorescently-labeled ddNTPs, the final products were incubated with 1 U of shrimp alkaline phosphatase (USB Corporation) for 1 hour at 37 °C (or overnight) and then at 86 °C for 20 min. to inactivate, the enzyme.

Table 2.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature and primers used for the SNaPshot reaction with their sequences and sizes.

| SNPs | HGVS Nomenclature | Oligo Sequence for Base Extension (5′>3′) | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs2312054 (A/T) | NG_021305.2: g.5338A>T | ACC TAT AGA GTA GAG AAG AAA GAA A | 25 |

| rs2071877 (C/T) | NG_021305.2: g25686C>T | (T)3CAT GCT ATT ATA AAT CAA AGT GAA AAG | 30 |

| rs2011162 (C/G) | NG_021305.2: g.27547C>G | (T)7ATA AAA ATG TGA ATC TCT TAA TTC TCA G | 35 |

Capillary Electrophoresis

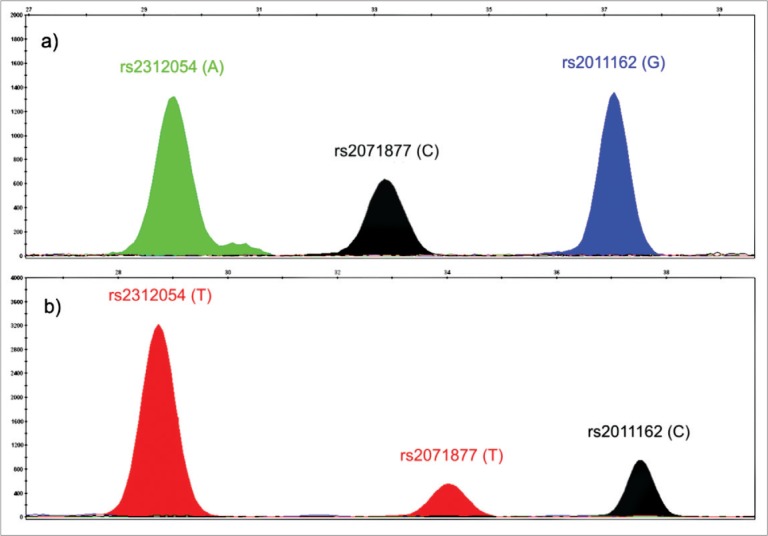

The SNaPshot products were separated by capillary electrophoresis on an ABI PRISM™ 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Life Technologies). Analysis of electropherograms was performed using the GeneMapper software (Life Technologies) and the sizes of the fragments was determined relative to the GeneScan120 LIZ size standard (Life Technologies). Representative electropherograms that show the three SNPs in the SLC6A14 gene in a patient with ACG (a) and a patient with TTC haplotypes (b), are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Electropherograms of two patients with different alleles for the studied SNPs.

Statistical Analysis

Allelic and haplotype frequencies were compared with statistical non parametric tests for categorical variables Pearson c2 using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 19 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Haplotype frequencies were calculated with Haploview 4.2 (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA) [17]. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Analysis of RNA Secondary Structure

Effect of different SNP alleles on RNA secondary structure was analyzed with RNAsnp web tool [18] that is a freely available web tool (http://rth.dk/resources/rnasnp/submit). We used two of the proposed modes of operation, Mode 1 and Mode 2, with default settings for folding window (200 bp) and default associated parameters for each mode. The two modes use different methods of calculation; Mode 1 uses a global folding method RNAfold, while Mode 2 uses a local folding method RNAplfold. Structural changes with a p value of less than 0.2 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Because we studied only male subjects and the SLC6A14 gene is on the X chromosome, we calculated only allelic and haplotype frequencies and compared results within populations. When we analyzed allelic frequencies, only the rs2011162 SNP showed difference in the distribution among infertile patients and fertile men. In both Macedonians and Slovenians, the rs2011162(G) allele was present with lower frequencies in infertile patients (Table 3). However, statistical significance was obtained only for the Macedonian population [p = 0.0439; odds ratio (OR) = 1.69; 95% confidence interval (95% CI) = 1.01–2.81].

Table 3.

Allelic and haplotype frequencies of three SLC6A14 single nucleotide polymorphisms in Macedonian and Slovenian men.

| Macedonian Men | Slovenian Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNPs in the SLC6A14 Gene | Infertile (n=123) | Fertile (n=127) | p Value | Infertile (n=247) | Fertile (n=114) | p Value |

| rs2312054(A/T)-SNP1 | 0.79/0.21 | 0.83/0.17 | NS | 0.79/0.21 | 0.77/0.23 | NS |

| rs2071877(C/T)-SNP2 | 0.63/0.37 | 0.72/0.28 | NS | 0.69/0.31 | 0.72/0.28 | NS |

| rs2011162(C/G)-SNP3 | 0.46/0.54 | 0.34/0.66 | 0.0439a | 0.37/0.63 | 0.36/0.64 | NS |

| Haplotypes of the SNP1, SNP2 and SNP3 | ||||||

| ACG | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.0144a | 0.45 | 0.48 | NS |

| ATC | 0.32 | 0.26 | NS | 0.28 | 0.21 | NS |

| TCG | 0.17 | 0.14 | NS | 0.18 | 0.16 | NS |

| ACC | 0.10 | 0.06 | NS | 0.05 | 0.08 | NS |

| TTC | 0.04 | 0.02 | NS | 0.03 | 0.07 | NS |

NS: not significant.

A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

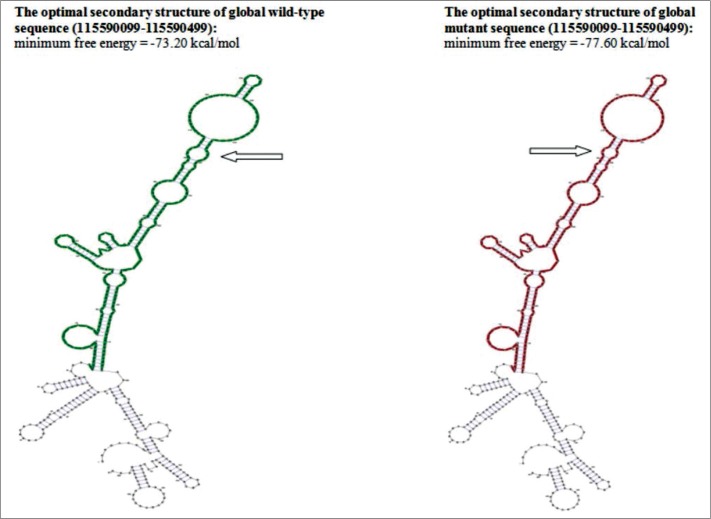

Five different haplotypes for rs2312054, rs2071877 and rs2011162 were observed in both populations: ACG, ATC, TCG, ACC and TTC (Table 3). Only one haplotype (ACG) showed statistically significant difference in distribution, but only in Macedonian men. It was less frequent (36.6%) in infertile Macedonian men than in fertile Macedonian controls (52.0%) [p = 0.0144; OR = 1.87; 95% CI = 1.13–3.11]. Analysis of the effect of the rs2011162 alleles on RNA secondary structure showed significant structural change in the alternative allele in comparison to the wild type allele when using Mode 1 for analysis (p = 0.0783) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The RNA secondary structure, in planar graph representation, of the region that contains the rs2011162, as an output from Mode 1 analysis. Arrows point to the region of putative secondary change in wild type and alternative sequences.

DISCUSSION

We previously showed that rs5911500 SNP, located in the Xq24 region, is associated with male infertility [7]. In close proximity to this SNP is the SLC6A14 gene that has previously been found in association with obesity [9] and cystic fibrosis [12], both of which have been implicated in male infertility. Because men are hemizygous for this gene, any positive or negative effect of a given allele would be expressed directly. For these reasons, we conducted this study to investigate the possible involvement of this gene in male infertilty/subfertility. In order to account for variation in SNP genotype and haplotype frequencies in different populations due to a physical separation and genetic drift, we have matched patients and controls in a population-based (Macedonian and Slovenian) manner from a fixed geographic area.

Of the three studied SNPs, only the rs2011162 differed in allele distribution between infertile and fertile men, and only in the Macedonian population. The alternative G allele for rs2011162 was present with a lower frequency in infertile Macedonian men (54.0%) in comparison to the fertile controls (66.0%). This allele was also a part of a rs2312054(A)-rs2071877(C)-rs2011162(G) haplotype that was present at significantly lower frequencies in infertile than in fertile Macedonian men. For comparison, data from 1000 Genomes showed that the rs2011162(G) allele varies in frequency from 27.0% in Africans to 66.0% in the American population. This means that in some populations, an alternative rs2011162(G) allele could be under selection and more favorable than the ancestral rs2011162 (C) allele. In our study, the alternative G allele was more prevalent in both the Macedonian and the Slovenian populations compared to the ancestral C allele. Based on results of significant association of the rs2011162(G) allele with male fertility, we further investigated the possible influence that this SNP could exhibit on SLC6A14 gene expression. It is localized in the 3′UTR (3′ untranslated region) of the SLC6A14 gene and is not a part of the coding and translated sequence of mRNA. However, the 3′UTR is important because it contains regulatory regions with roles in transcript cleavage, stability and polyadenylation, translation and mRNA localization [19]. Mutations that change the secondary structure of the 3′UTR may result in disruption of expression [19–22]. Our assessment of the possible influence of rs2011162 alleles on secondary structure of the 3′UTR showed a significant (p = 0.0783) structural effect in Mode 1 of analysis and indicated that the SLC 6A14 mRNA with a rs2011162(G) allele might be expressed more efficiently than the mRNA with the rs2011162(C) allele.

In conclusion, an alternative rs2011162(G) allele and the SLC6A14 rs2312054(A)-rs2071877(C)-rs2011162(G) haplotype might exhibit some kind of protective effect on the spermatogenesis. SLC6A14 could be a population-specific, low-penetrance locus that confers susceptibility to male infertility/subfertility. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study addressing the possible association of SLC6A14 with male infertility. More rigorous follow-up studies, involving larger number of infertile men from different populations and eventually, testicular expression studies, are needed in order to confirm this finding.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest. This study was supported by grant CRP/MAC09-01 from ICGEB-Trieste (to D. Plaseska-Karanfilska). The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Kretser DM, Loveland KL, Meinhardt A, Simorangkir D, Wreford N. Spermatogenesis. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(Suppl 1):1–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.suppl_1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlin A, Arredi B, Foresta C. Genetic causes of male infertility. Reprod Toxicol. 2006;22(2):133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plaseska-Karanfilska D, Noveski P, Plaseski T, Maleva I, Madjunkova S, Moneva Z. Genetic causes of male infertility. Balkan J Med Genet. 2012;15(Suppl):31–34. doi: 10.2478/v10034-012-0015-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dohle GR, Colpi GM, Hargreave TB, Papp GK, Jungwirth A, Weidner W, EAU Working Group on Male Infertility EAU guidelines on male infertility. Eur Urol. 2005;48(5):703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sivakumaran S, Agakov F, Theodoratou E, Prendergast JG, Zgaga L, Manolio T, et al. Abundant pleiotropy in human complex diseases and traits. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(5):607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aston KI, Krausz C, Laface I, Ruiz-Castane E, Carrell DT. Evaluation of 172 candidate polymorphisms for association with oligozoospermia or azoospermia in a large cohort of men of European descent. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(6):1383–1397. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plaseski T, Noveski P, Popeska Z, Efremov GD, Plaseska-Karanfilska D. Association study of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in FASLG, JMJDIA, LOC203413, TEX15, BRDT, OR2W3, INSR, and TAS2R38 genes with male infertility. J Androl. 2012;33(4):675–683. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.111.013995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sloan JL, Mager S. Cloning and functional expression of a human Na+ and Cl−-dependent neutral and cationic amino acid transporter B0+ J Biol Chem. 1999;274(34):23740–23745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suviolahti E, Oksanen LJ, Ohman M, Cantor RM, Ridderstrale M, Tuomi T, et al. The SLC6A14 gene shows evidence of association with obesity. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(11):1762–1772. doi: 10.1172/JCI17491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durand E, Boutin P, Meyre D, Charles MA, Clement K, Dina C, et al. Polymorphisms in the amino acid transporter solute carrier family 6 (neurotransmitter transporter) member 14 gene contribute to polygenic obesity in French Caucasians. Diabetes. 2004;53(9):2483–2486. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.9.2483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corpeleijn E, Petersen L, Holst C, Saris WH, Astrup A, Langin D, et al. Obesity-related polymorphisms and their associations with the ability to regulate fat oxidation in obese Europeans: the NUGENOB study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(7):1369–1377. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun L, Rommens JM, Corvol H, Li W, Li X, Chiang TA, et al. Multiple apical plasma membrane constituents are associated with susceptibility to meconium ileus in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Nat Genet. 2012;44(5):562–569. doi: 10.1038/ng.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Soave D, Miller MR, Keenan K, Lin F, Gong J, et al. Unraveling the complex genetic model for cystic fibrosis: Pleiotropic effects of modifier genes on early cystic fibrosis-related morbidities. Hum Genet. 2014;133(2):151–161. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1363-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aragon MA, Ayala ME, Marin M, Aviles A, Damian-Matsumura P, Dominguez R. Serotoninergic system blockage in the prepubertal rat inhibits spermatogenesis development. Reproduction. 2005;129(6):717–727. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tinajero JC, Fabbri A, Ciocca DR, Dufau ML. Serotonin secretion from rat Leydig cells. Endocrinology. 1993;133(6):3026–3029. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.6.8243331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collin O, Damber JE, Bergh A. 5-Hydroxytryptamine – A local regulator of testicular blood flow and vasomotion in rats. J Reprod Fertil. 1996;106(1):17–22. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1060017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: Analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sabarinathan R, Tafer H, Seemann SE, Hofacker IL, Stadler PF, Gorodkin J. The RNAsnp web server: Predicting SNP effects on local RNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Web Server issue):W475–W479. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrett LW, Fletcher S, Wilton SD. Regulation of eukaryotic gene expression by the untranslated gene regions and other non-coding elements. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(21):3613–3634. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0990-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chatterjee S, Pal JK. Role of 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions of mRNAs in human diseases. Biol Cell. 2009;101(5):251–262. doi: 10.1042/BC20080104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas U, Sczakiel G, Laufer SD. MicroRNA-mediated regulation of gene expression is affected by disease-associated SNPs within the 3′-UTR via altered RNA structure. RNA Biol. 2012;9(6):924–937. doi: 10.4161/rna.20497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritz J, Martin JS, Laederach A. Evaluating our ability to predict the structural disruption of RNA by SNPs. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(Suppl 4):S6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-S4-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]