Abstract

The sarcomeric M-region anchors thick filaments and withstands the mechanical stress of contractions by deformation, thus enabling distribution of physiological forces along the length of thick filaments. While the role of the M-region in supporting myofibrillar structure and contractility is well established, its role in mediating additional cellular processes has only recently started to emerge. As such, M-region is the hub of key protein players contributing to cytoskeletal remodeling, signal transduction, mechanosensing, metabolism, and proteasomal degradation. Mutations in genes encoding M-region related proteins lead to development of severe and lethal cardiac and skeletal myopathies affecting mankind. Herein, we describe the main cellular processes taking place at the M-region, other than thick filament assembly, and discuss human myopathies associated with mutant or truncated M-region proteins.

1. Introduction

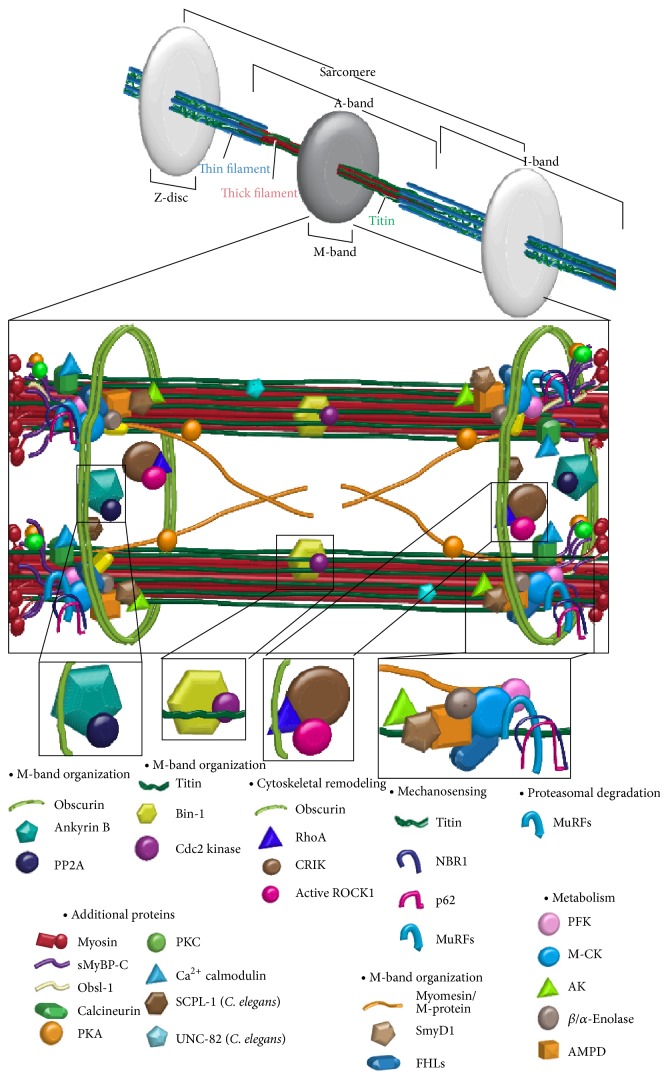

The M-band is a dense protein-packed structure at the center of the A-band of cardiac and skeletal muscle cells (Figure 1 and Table 1). Under the electron microscope, M-band appears as a series of dark transverse lines spanning ~500–750 Å, depending on fiber type and species [1]. Named for the German word “mittelscheibe,” which means “central disc,” the M-band lies at the center of the bare zone, which is devoid of myosin heads and cross-bridges [2] but encompasses overlapping arrays of antiparallel myosin rods [3]. Adjacent myosin rods are connected via M-bridges, forming a regular hexagonal lattice [4]. The M-bridges are necessary to maintain thick filament alignment and aid in the controlled distribution of mechanical stress across the sarcomere during active contraction [5].

Figure 1.

Sarcomeric M-region road map and cellular processes. Schematic representation of the sarcomeric M-region depicting key proteins and highlighting cellular processes.

Table 1.

Properties of M-region proteins.

| Protein | Localization | Muscle specificity | Residency | PDB ID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M-band organization | |||||

| Complex 1 | Obscurins (ABD) | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | NA |

| Ankyrin-B (Exon 43′) | Periphery | Cardiac | Permanent | NA | |

| PP2A (B56α) | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | NA | |

|

| |||||

| Complex 2 | Titin (Mis4) | Periphery/interior | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | NA |

| Bin-1 | Interior | Cardiac/skeletal (developmental) | Transient | 1MV3 | |

| Cdc2 Kinase | Interior | Cardiac/skeletal (developmental) | Transient | NA | |

|

| |||||

| Myomesin | Periphery/interior | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 3RBS, 2Y23, 2R15, 2Y25 | |

| SmyD1 | Periphery | Cardiac/fast skeletal | Permanent | 3N71 | |

| FHLs | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 2EGQ, 2D8Z | |

|

| |||||

| Cytoskeletal remodeling | |||||

| Obscurins (RhoGEF) | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | NA | |

| RhoA | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Transient | 1LB1, 3KZ1 | |

| CRIK | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Transient | NA | |

| Active ROCK1 | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Transient | 2ETR | |

|

| |||||

| Mechanosensing | |||||

| Titin (Titin Kinase) | Periphery/interior | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 4JNW, 1TKI | |

| NBR1 | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 4OLE | |

| P62 | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 2KTR, 3B0F, 2MGW | |

| MuRFs | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 4M3L, 3Q1D | |

|

| |||||

| Metabolism | |||||

| PFK | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 4OMT | |

| M-CK | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 1I0E | |

| AK | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 2C95 | |

| Enolases | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 3B97, 2XSX | |

| AMPD | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 2Y2C | |

|

| |||||

| Proteasomal degradation | |||||

| MuRFs | Periphery | Cardiac/skeletal | Permanent | 4M3L, 3Q1D | |

Note: protein domains mediating complex formation or participating in cellular processes are shown in parenthesis when known. Acronyms of proteins are described in the text; ABD: ankyrin binding domain; NA: not available. The PDB files of proteins in Complex 1 and Complex 2, as well as obscurins (RhoGEF) and titin (titin kinase), are associated with the specific domains that mediate binding within the complex; in all other cases, the available PDB files for the entire protein are provided.

In addition to the rod region of myosin, the M-band is “home” to several other proteins (Figure 1 and Table 1). As such, the COOH-termini of titin molecules from half sarcomeres converge in an antiparallel fashion at the M-band [6]. Composed of immunoglobulin (Ig) domains and unique sequences, the COOH-terminus of titin is located downstream of its kinase domain, which is found at the junction of A- and M-bands.

The M-band also contains myomesin, M-protein, and myomesin-3, which share similar domain architectures and are primarily composed of Ig and fibronectin type III (FnIII) domains, but contain distinct NH2-terminal heads [7, 8]. These proteins are the principal components of M-bridges forming the backbone of the M-band filamentous system, which cross-links neighboring thick filaments [6, 8].

Also localizing at the level of the M-region are additional sarcomeric and membrane associated proteins, including obscurins, select variants of Myosin Binding Protein-C Slow, ankyrins, and spectrins [9–12]. These contribute to the assembly and stabilization of the M-region and its linkage with the sarcomeric cytoskeleton, the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), and the sarcolemma [13].

Within the last decade, our knowledge of the sarcomeric M-region has steadily expanded. To date, there are several excellent reviews on protein complexes mediating the assembly and organization of the entire M-region encompassing the M-band core as well as its periphery, and its role in thick filament assembly and integration into A-bands [5, 14]. Herein, we focus on key protein mediators of additional cellular processes occurring at the M-region. In addition, we highlight skeletal and cardiac myopathies that are linked to mutations in genes encoding M-region related proteins.

2. Cellular Processes at the M-Region

M-region is the hub for multiple cellular processes including signal transduction, metabolism, mechanosensing, and proteasomal degradation. Such processes support cellular homeostasis, myofibrillar organization, and contractile activity by maintaining sarcomeric integrity, meeting the energy demand during active contraction, and enabling adaptation to different biochemical and biomechanical stimuli. Below we will address these important processes occurring at the M-region and discuss key proteins.

2.1. Signal Transduction via Posttranslational Modifications

Two main types of posttranslational modifications, phosphorylation and sumoylation, have been described at the M-region. These mediate proper protein localization, regulate protein-protein interactions, and relay signals in response to biochemical or biomechanical stimuli.

2.1.1. Phosphorylation

Several M-region proteins possess active kinase domains and/or are regulated by phosphorylation. Below we discuss such proteins.

Titin (~3-4 MDa). The giant protein titin extends longitudinally across a half-sarcomere, with its NH2-terminus anchored to the Z-disc, and its COOH-terminus localized at the center of the M-band [15]. The M-band portion of titin (~200 kDa) is composed of ten Ig CII type domains, which are interspersed with unique nonmodular segments, termed M-insertions [13, 16, 17]. The insertion between Ig CII-5 and Ig CII-6 contains tandem lysine-serine-proline (KSP) repeats, which are heavily phosphorylated by Cdc2 kinase in developing, but not in differentiated muscle cells [16]. The phosphorylated KSP repeats interact in vitro with the SH3 domain of the tumor suppressor bridging integrator protein 1 (Bin1) [18]. Bin1 is a negative regulator of c-Myc activation that is preferentially expressed in differentiating, but not mature, myotubes [18]. Transgenic mice overexpressing the SH3 domain of Bin1 exhibit dramatic disarray in myofiber size and structure [18]. Conversely, mouse C2C12 skeletal myoblasts fail to differentiate following downregulation of Bin1 [19, 20], and Bin1 homozygous knock-out mice develop hypertrophic cardiomyopathy leading to perinatal lethality, although skeletal muscles do not exhibit any apparent abnormalities at this stage [21]. It is therefore possible that disruption of the interaction between the phosphorylated KSP repeats of titin and Bin1 at the M-band may result in deregulated myofibrillar assembly, loss of differentiation, and aberrant fiber size.

In addition to being phosphorylated within its M-band portion, titin may regulate different sarcomeric processes via its kinase domain, residing at the periphery of the M-band [6, 13, 22, 23]; one of these processes is mechanosensing, which will be discussed in a later section of this review.

Obscurin (720–890 kDa). Incorporated early during development into the periphery of the sarcomeric M-band, obscurin is an important player of thick filament assembly and stabilization [24]. Downregulation of obscurin using siRNA technology leads to selective disorganization of M- and A-bands in developing skeletal and cardiac myocytes, indicating its scaffolding role [24–26]. Importantly, recent studies have demonstrated that the two Ser/Thr kinase domains, which are present at the COOH-terminus of giant obscurin-B are catalytically active and can directly bind major components of the M-band, including titin and four and a half LIM domains 2 (FHL2) protein [27, 28]. Examining if these proteins are catalytic substrates of the obscurin kinase domains at the M-band will be the next challenge.

Obscurin is also involved in dephosphorylation events at the M-band. Ankyrin-B (Ank-B), fulfilling its role as an anchoring protein, binds directly to both obscurin and the regulatory subunit, B56α, of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) at the M-band [29, 30]. Overexpression of the obscurin-binding region of Ank-B in isolated adult cardiomyocytes results in displacement of B56α from the M-band [29]. Moreover, UNC-89, the obscurin homologue in C. elegans, directly binds to small C-terminal domain (CTD) phosphatase-like 1 (SCPL-1) at the M-band [28, 31]. However, the cellular processes that PP2A and SCPL-1 mediate at the M-band are still unknown.

Myomesin (178–188 kDa). Spanning the entire M-region by residing in the interior yet extending to the periphery of the M-band, myomesin serves as a cross-linker between myosin, titin, and obscurin [32, 33]. It consists of tandem Ig and FnIII domains, along with a nonmodular NH2-terminus [32–35]. While the NH2-terminus of myomesin interacts with sarcomeric myosin [36], the region encompassing Ig domains 4 and 5 (My4-My5) directly interacts with titin Ig4 within its M-band portion (MIg4) [32, 34]. Phosphorylation of the linker region between myomesin domains My4 and My5 by protein kinase A (PKA) abolishes its binding to titin MIg4 [32]. Importantly, the linker region also interacts with two other M-band proteins, obscurin, and obscurin-like 1, but these interactions are not modulated by phosphorylation [33]. Thus, a ternary complex of regulated and potentially constitutive interactions between myomesin and titin, and myomesin and obscurin, or obsl-1 occurs at the M-band [33].

M-Protein (~165 kDa). Similar to myomesin, M-protein also consists of tandem Ig and FnIII domains, which are preceded by a unique NH2-terminus [6, 37, 38]. Unlike myomesin though, which is expressed ubiquitously in all striated muscles, M-protein is only expressed in cardiac and fast-twitch skeletal muscles [39–41]. Phosphorylation at S76, present in the nonmodular NH2-terminus of M-protein, by PKA abolishes its binding to myosin [42].

Thus, the PKA-mediated phosphorylation of both myomesin and M-protein may modulate thick filament integration, organization, and stability at the M-band during myofibrillogenesis or myofilament turnover.

Myomesin-3 (~162 kDa), also composed of a nonmodular NH2-terminus and tandem Ig and FnIII domains, is present at the M-band, too [8]. Unlike myomesin, which is ubiquitously present in all striated muscles and M-protein that is preferentially expressed in cardiac and fast-twitch skeletal muscles, myomesin-3 is selectively expressed in slow-twitch skeletal muscles [8, 43]. Whether myomesin-3 is subjected to posttranslational modifications, however, remains to be investigated. Along the same lines, select variants of Myosin binding protein-C slow (MyBP-C slow), FHL1, and FHL2 and obscurin-like 1 also localize at the M-region [10, 33, 44–48]. Out of these proteins, at least MyBP-C slow is modulated via phosphorylation mediated by PKA and PKC [49]. Moreover, the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase, calcineurin (also known as protein phosphatase 2B, PP2B), is also present at the M-band and may mediate dephosphorylation events of M-band proteins [47]. At this time though, the physiological significance of the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events involving these proteins remains speculative.

In addition to the phosphorylation events discussed above, which have been mainly studied in mammalian striated muscles, additional protein players involved in posttranslational modification events within the M-region have been reported in C. elegans. Unlike the cross-striated muscles of mammals, myofilaments of body muscles in C. elegans are arranged in oblique striations. Therefore, both the protein composition and the functional role(s) of individual proteins at the M-region of body muscles of C. elegans may differ from those of mammalian striated muscles. Below, we provide such an example.

UNC-82 (33–203 kDa). Recently identified as a Ser/Thr kinase that localizes at or near the M-band in C. elegans, UNC-82 is closely related to mammalian proteins AMPK-related protein kinase 5 (ARK5) and sucrose nonfermenting AMPK-related kinase (SNARK) (also known as NUAK1 and NUAK2, resp.), which are members of the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) family of Ser/Thr kinases [50]. While the enzymatic activity and substrates of UNC-82 remain to be determined, mutant C. elegans embryos containing either a missense mutation presumably abolishing its kinase activity or a nonsense mutation resulting in truncated UNC-82 exhibit disorganized A- and M-bands [50]. Interestingly, its closely related mammalian counterparts, ARK5 and SNARK, have been implicated in glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle [51, 52]; however the localization of ARK5 and SNARK has yet to be examined.

2.1.2. SUMOylation

In addition to phosphorylation, proteins at the M-region undergo sumoylation. While less studied compared to phosphorylation, sumoylation has been implicated as a possible mechanism for targeting proteins to the M-region.

Myomesin (178–188 kDa). In addition to being regulated via phosphorylation, myomesin is also subjected to sumoylation, possibly at K228, in adult rat cardiomyocytes [53]. Moreover, in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVM), where myomesin is localized to the nucleus, overexpression of the SUMO peptide mediates its translocation to the cytoplasm and promotes sarcomeric organization [54]. Sumoylation of myomesin is mediated by myofibrillogenesis regulator-1 (MR-1), which is highly expressed in both skeletal and cardiac muscles [54, 55]. While overexpression of MR-1 in mice enhances cardiac hypertrophy stimulated by angiotensin II, overexpression of MR-1 in NRVM induces sarcomeric organization and translocation of myomesin from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, similar to SUMO overexpression [54, 56]. Consistent with this, downregulation of MR-1 abolishes SUMO-induced translocation of myomesin to the cytoplasm and sarcomeric organization [54].

SET and MYND Domain Containing-1 (SmyD1) (~54–56 kDa). SmyD1 is another M-band protein whose localization is modulated by sumoylation [57, 58]. Also known as Bop, SmyD1 is a histone methyltransferase that is abundantly expressed in striated muscles with its methyl transferase activity attributed to its Su(var)3-9, enhancer-of-zeste, and trithorax (SET) domain [59–63]. In mouse, the smyd1 locus encodes two alternatively spliced isoforms, SmyD1_tv1, and SmyD1_tv2 (also known as skm-Bop1 and skm-Bop2, resp.) [60, 61, 63]. SmyD1_tv1 and SmyD1_tv2 localize at the M-band and the nucleus in both cardiac and skeletal muscles [57, 60]. Homozygous deletion of smyd1 in mice results in embryonic lethality at E10.5 due to disrupted ventricular formation, which is accompanied by loss of right ventricles [61]. Recently, skeletal muscle- and heart-specific α nascent polypeptide-associated complex, skNAC, was shown to mediate the sumoylation of SmyD1 proteins and thus regulate their nuclear export and translocation to the M-band during sarcomerogenesis [58, 64]. Thus, sumoylation mediates SmyD1 targeting to the M-band, where it potentially regulates the activities of major M-band proteins, such as myosin and muscle-type creatine kinase, via its methyl transferase activity.

Proteins at the M-region undergo additional posttranslational modifications, such as acetylation, methylation, and neddylation. For instance, small ankyrin 1.5 (sAnk1.5) is subjected to acetylation and neddylation [65, 66], while muscle-type creatine kinase and myosin are subjected to acetylation and methylation [66, 67]. However, the functional significance and the identity of the relevant enzymes carrying out these posttranslational modifications at the M-band remain to be further investigated.

2.2. Cytoskeletal Remodeling via Small GTPases

Small GTPases play important roles in diverse cellular and developmental processes, including cytoskeletal remodeling, actomyosin contractility, vesicle transport, growth, and proliferation [68–72]. Small GTPases are regulated via repeating cycles of GTP binding and hydrolysis. Three accessory proteins contribute to their regulation: (i) GTPase activating proteins (GAP), which hydrolyze GTP to GDP, inactivating small GTPases, (ii) guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEF), which mediate the exchange of GDP to GTP activating small GTPases, and (iii) guanosine nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDI), which prevent the exchange of GDP for GTP by sequestering GTPases and preventing them from binding to downstream effectors [73, 74]. Ras homolog gene family, member A protein, RhoA, localizes at the M-band in adult skeletal and cardiac muscles [66, 75]. While RhoA mediates several cellular processes, the discussion below will mainly focus on its roles in cytoskeletal remodeling at the M-band.

2.2.1. RhoA Signaling in Skeletal Muscle

Inactive RhoA preferentially localizes to the M-band of adult skeletal myofibers, whereas active RhoA exhibits a dual distribution, at both M-bands and Z-disks [75]. RhoA activity is significantly increased following overexpression of the obscurin RhoGEF motif in adult rat tibialis anterior (TA) muscle and after injury induced by large-strain lengthening contractions [75]. Consistent with this, the RhoGEF/Pleckstrin homology cassette of Unc-89, the C. elegans obscurin homologue, activates Rho-1, the RhoA C. elegans homologue [76]. In mammalian skeletal muscle, active RhoA leads to loss of citron rho-interacting kinase (CRIK), which is involved in the regulation of cytokinesis in proliferating cells, from M- and A-bands [75, 77, 78]. Moreover, active RhoA leads to translocation of Rho-associated protein kinase 1 (ROCK1) from the Z-disk to the I-band, the Z/I junction, and the M-band [75]. Although the functional ramifications of the concurrent loss of CRIK from the M-band and the translocation of ROCK1 to the M-band are still elusive, it is likely that they mediate the activation of stretch-response genes leading to cytoskeletal remodeling or the development of hypertrophy following injury. Consistent with this, activation of the RhoA/ROCK pathway in dystrophin/utrophin double knockout mice has been implicated with heterotopic ossification, while inhibition of the RhoA/ROCK pathway has been associated with improved myogenic potential [79, 80].

RhoA localizes at both M-bands and Z-disks in cardiac muscle, too, although its distribution has not been correlated with its state of activation [66]. Extensive studies have focused on the diverse processes that RhoA mediates in the developing and adult myocardium, emphasizing its roles in the regulation of actin filament assembly and stress fiber formation, sarcomeric organization, induction of a hypertrophic response, tolerance to ischemia/reperfusion, survival, and apoptosis [81–88]. Given that it is currently unknown whether RhoA contributes to these processes through its interactions at the Z-disk or the M-band, we will refrain from presenting such studies in detail.

2.3. Mechanosensing

In addition to biochemical stimuli, muscle cells respond to biomechanical stimuli by modulating protein expression through activation of signaling pathways [89, 90]. Consistent with this, both the Z-disk [91, 92] and the M-band [92] contain mechanosensors that may transform biomechanical stimuli to biochemical signals. At the M-band, the kinase domain of titin is a major player mediating cell responses to mechanical stress.

2.3.1. Titin Kinase

Use of atomic force microscopy (AFM) has demonstrated that the kinase domain of titin is activated upon exertion of mechanical force, leading to unfolding of its regulatory autoinhibitory tail and phosphorylation of Y170, allowing ATP binding to the catalytic aspartate [93]. It is therefore likely that activation of the titin kinase via mechanical force may result in regulation of its proximal substrates via phosphorylation. This is exemplified in the case of the direct interaction between the titin kinase domain and the muscle-specific ring finger (MuRF) complex, consisting of NBR1 (neighbor of BRCA1 gene 1 protein)/p62/MURF-2, which has been suggested to regulate protein turnover in response to mechanical force [23]. Both NBR1 and p62 are substrates of titin kinase [23] and are required in autophagosome-mediated protein degradation by serving as receptors for ubiquitinated proteins [94–96]. Since NBR1 can only bind to the semiopened conformation of the titin kinase that is likely induced by exertion of mechanical force during stretching, it is possible that MuRF-2 is anchored to the M-band via the interaction of NBR1 with the kinase domain of titin [23]. Consistent with this, denervation of skeletal myofibers or mechanical arrest of neonatal cardiomyocytes leads to dissociation of the MuRF-2/NBR1/p62 complex, with MuRF-2 translocating to the nucleus in both skeletal and cardiac cells where it suppresses serum response factor- (SRF-) mediated expression of hypertrophic genes, and p62 accumulating at intercalated disks in cardiac cells [23]. It is noteworthy to mention, however, that a recent study indicated that the kinase domain of titin is not enzymatically active but serves as a scaffold for other proteins that localize to the M-region [97]. Additional studies are warranted to resolve these opposing results.

2.4. Metabolism

Sarcomeric M-band is strategically located in close proximity to where significant amounts of energy are consumed during repeating cycles of actomyosin contractility [98–100]. Maintaining the ATP and ADP levels at optimal concentrations in the sarcoplasm is essential in sustaining muscle activity, as depletion of ATP or accumulation of ADP would attenuate contractility [101]. Below we discuss several proteins localized at the M-band, which play key roles in metabolism by maintaining the ATP/ADP ratio at optimal levels within the sarcoplasm.

2.4.1. Muscle-Type Creatine Kinase (M-CK)

Creatine kinase (CK) catalyzes the phosphate transfer from phosphocreatine to ADP, generating ATP and creatine (Phosphocreatine2− + MgADP− + H+↔ MgATP2− + creatine) [102]. In the mammalian genome, there are four gene loci encoding the different CK isoenzymes: muscle-type CK (M-CK), brain-type CK (B-CK), ubiquitous mitochondrial CK (uMtCK), and sarcomeric mitochondrial CK (sMtCK) [103]. While both M-CK and sMtCK are readily expressed in striated muscles, only M-CK is present within the sarcomere [103–105]. M-CK functions as a dimer and localizes at the M-band by interacting with myomesin, M-protein, and FHL-2 [46, 106]. Homozygous null M-CK mice exhibit decreased voluntary running capability, which is accompanied by a significant reduction in force production during initial contractions due to inadequate supply of local ATP [105, 107–109]. Interestingly, malignant transformation of skeletal muscle to sarcoma results in reduction of M-CK levels, indicating that M-CK supports the specific metabolic needs of skeletal myofibers, which gradually lose their differentiation status and contractile properties during sarcoma development [110].

2.4.2. Adenylate Kinase (AK)

Similar to M-CK, AK is also present at the M-band [46]. AK catalyzes the transfer of a phosphate from ADP to another ADP to generate AMP and ATP and vice versa (MgADP− + ADP2−↔ MgATP2− + AMP−), thus maintaining myofibrillar ATP and ADP concentrations at optimal levels [111, 112]. There are nine AK isoenzymes in mammals, referred to as AK1-AK9 [113]. While the majority of AKs localize to mitochondria, AK1 and AK7 are primarily present in the sarcoplasm [113]. At rest, skeletal muscles of homozygous AK1 knockout mice contain increased levels of AMP, without any other pathological phenotype [112]. However, upon induction of high frequency (90–120 tetani/min) contractions, gastrocnemius, plantaris, and soleus AK1 null muscles exhibit increased levels of ADP, accompanied by slower relaxation rate, although the magnitude of the generated force is unaltered [112, 114, 115]. The slower relaxation rate is likely due to reduced Gibbs-free energy in response of the increased ADP : ATP ratio, resulting in compromised sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) activity and decreased Ca2+ uptake by the SR [112]. Moreover, exposure of AK1 deficient mice to ischemia/reperfusion results in accelerated loss of cardiac contractility and reduced ATP and ADP levels during reperfusion, underscoring the importance of AK1 in supporting myocardial function by regulating energy metabolism [116]. The presence of AK in the sarcomere is therefore essential for meeting the high-energy demands of muscle cells and protecting them from insults.

2.4.3. Adenosine Monophosphate Deaminase (AMPD)

Three genes encoding AMPD proteins have been identified: AMPD1, AMPD2, and AMPD3 (reviewed in [117]). AMPD1 encodes an AMPD form that is preferentially expressed in striated muscles, M-AMPD [118, 119]. M-AMPD at the M-band is coupled with M-CK and AK to modulate the ATP, ADP, and AMP levels [101, 120]. AMPD catalyzes the removal of an amine group from AMP, giving rise to ammonia and IMP (AMP− → IMP− + NH3) [101]. In conjunction with AK, AMPD maintains constant intracellular ADP levels, therefore preventing AMP accumulation and favoring the formation of ATP by AK [101].

2.4.4. Phosphofructokinase (PFK)

The fourth metabolic enzyme residing at the M-band, PFK, mediates the transfer of a phosphate group from ATP to fructose-6-phosphate to yield fructose-1, 6-bisphosphate (Fructose-6-P− + MgATP2− → Fructose-1,6-P2 2− + MgADP−), and is a rate-limiting enzyme of the glycolytic pathway [121, 122]. There are three PFK isoenzymes in mammals, PFK-M (muscle), PFK-L (liver), and PFK-P (platelet). Skeletal muscles express exclusively PFK-M, whereas cardiac muscle expresses all three isoenzymes, with PFK-M being the predominant one [123]. Fully activated PFK exists in tetrameric or a more complex oligomeric form, while dimeric PFK confers minimal activity [124]. PFK's activity is modulated by allosteric regulators (e.g., adenosine phosphates and fructose-2, 6-bisphosphate), interacting partners (e.g., F-actin and calmodulin), or posttranslational modifications (e.g., acylation and phosphorylation) [122, 124–126]. Thus, AMP and ADP stabilize PFK in a tetrameric conformation, whereas ATP and citrate stabilize PFK in a dimeric conformation [121, 124, 127–132]. Enhanced binding to F-actin in response to insulin stimulation also stabilizes the tetrameric form of PFK and maintains it in an active conformation [133–135]. Alternatively, PFK may be regulated by a complex mechanism in response to calcium fluctuation in the sarcoplasm [136]. Given the presence of two calmodulin binding sites in PFK, it has been proposed that PFK activity is strongly inhibited when both sites are occupied [124, 137]. However, occupation of only one calmodulin site may abrogate the inhibitory effect mediated by ATP- and citrate-binding via induction of a dimeric conformation that is fully active [124, 138]. Intriguingly, phosphorylation mediated by calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK) results in increased sensitivity to ATP inhibition [129]. Since calmodulin binding is modulated by Ca2+, the activity of PFK may be modulated by the Ca2+ levels in the sarcoplasm, especially during contractions. PFK-M homozygous null mice (PFKM−/−) exhibit high mortality at weaning (60%), reduced life-span (~3–6 months), and decreased ATP concentration in skeletal muscles, accompanied by increased glycogen content and exercise intolerance [139]. Notably, the small number of PFKM null animals that survive beyond 6 months of age develops cardiac hypertrophy by year one [139]. The reduced viability of the PFKM deficient mice is consistent with PFK being the rate-limiting enzyme in the glycolytic pathway and underscores its key role in energy production.

2.4.5. Enolase

In addition to PFK, enolase is another glycolytic enzyme that resides at the M-band [140, 141]. Three gene loci encode the three known enolase isozymes, which are expressed in different tissues: nonneuronal enolase, α (NNE), muscle-specific enolase, β (MSE), and neuronal-specific enolase, γ (NSE) [142, 143]. Both α- and β-isozymes are expressed in cardiac and skeletal muscles, localize at the M-band, and may form homo- or heterodimers [140, 141, 144, 145]. Dimeric enolase converts the glycolytic intermediate 2-phospho-D-glycerate to phosphoenolpyruvate (2-phospho-D-glycerate2−↔ phosphoenolpyruvate2− + H2O) [146]. While ββ-enolase homodimers are predominantly expressed in skeletal muscle, especially in Type II muscle fibers [141, 147, 148], αα-, αβ-, and ββ-dimers are present in cardiac muscle [145, 148, 149]. The relative expression of α and β isozymes in the heart is important in fine-tuning metabolic activity. Consistent with this, in a rat hypertrophy model induced by aortic stenosis, where the rate of glycolysis is increased [150], the ratio of the α- to β-isozymes is increased in the heart, due to reduced expression of β-enolase, although the levels of α-enolase are unaltered [149]. Conversely, in the spontaneous hypertensive (SHR) rat model, the hypertrophied heart expresses increased levels of the α-isozyme, which is also hyperphosphorylated [149, 151, 152]. While the α- and β-enolases exhibit comparable enzymatic kinetics, the hyperphosphorylated α-isozyme performs slower catalysis [152, 153]. Overexpression of α-enolase in response to ischemia/reperfusion in a rat model confers improved contractility of affected cardiomyocytes [154]. Consistent with its protective role in the heart, α-enolase is significantly upregulated in mouse skeletal muscle, which predominately expresses β-enolase, in response to muscle injury induced by cardiotoxin; interestingly, the expression of β-enolase is drastically decreased after the first day but recovers a week later [155]. Similarly, in rat skeletal muscles subjected to denervation, the levels of the αα dimer are modestly increased, while the levels of the ββ-dimer are decreased [148]. It is noteworthy to mention that since α-enolase may also serve as a heat-shock protein or a plasminogen receptor involved in cardiac remodeling and muscle regeneration, it is possible that the protective role of α-enolase may not only be related to its glycolytic activity [152, 156].

Regulation of energy metabolism may also be mediated through proteasomal degradation. Muscle-specific RING finger proteins (MuRFs) present at the M-band ubiquitinate metabolic enzymes, which are subsequently targeted for proteasomal degradation [157–159]. Along these lines, oxidized muscle-type creatine kinase is rapidly ubiquitinated by MuRF-1 and subsequently targeted to the proteasome [159, 160]. In addition, MuRF-1 also interacts with adenylate kinase [157], although the effects of this interaction are still elusive. The importance of MuRFs at the M-band is further discussed in the following section.

2.5. Proteasomal Degradation

MuRFs. The MuRF family consists of three members, MuRF-1, MuRF-2, and MuRF-3, which are E3 ubiquitin ligases, and preferentially expressed in striated muscles [161–163]. They contain a RING finger domain at their NH2-terminus and transfer ubiquitin-chains to the proteins destined for proteasomal degradation [158, 162]. The poly-ubiquitinated proteins are recognized by the proteasome, subjected to deubiquitination, unfolding, and hydrolysis in its proteolysis core [164]. While MuRF-3 is ubiquitously expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscles, MuRF-1 is preferentially expressed in cardiac and fast-twitch skeletal muscles, and MuRF-2 is predominantly expressed in slow-twitch skeletal muscles, with minimal expression in cardiac and fast-twitch skeletal muscles [165, 166]. All three MuRFs localize to the M-band and the nucleus [167]. Additionally, MuRF-1 and MuRF-3 are also present at the Z-disc [167].

2.5.1. MuRF-1

MuRF-1 interacts with the Ig168/Ig169 domains within the A-band portion of titin, while the presence of the adjacent titin kinase domain enhances this interaction [97, 163]. Overexpression of MuRF-1 disrupts the organization of M- and A-bands, but not of Z-disks and I-bands, in chick cardiomyocytes [168], indicating that increased protein turnover rate at M- and A-bands results in dissolution of these structures. Interestingly, MuRF-1 deficient mice exhibit no major alterations in the levels of ubiquitination within the myocardium, suggesting redundant functionality among MuRFs in cardiac muscle [157].

2.5.2. MuRF-2

MuRF-2 anchors to the M-band via its association with p62 and NBR1 [23, 94]. Downregulation of MuRF-2 results in disrupted M-bands, in addition to perturbed intermediate filament and microtubule networks [169]. Consistent with the notion that MuRFs may have redundant functions in striated muscles, MuRF-2 deficient mice exhibit no apparent phenotype in the absence of physiological stress [157, 170]. Interestingly though, homozygous MuRF-1/MuRF-2 double knock-out mice exhibit loss of Type II fibers in soleus muscle as well as severe cardiac and modest skeletal muscle hypertrophy due to increased protein synthesis, although proteasomal degradation is unaffected [165, 171]. This suggests additional roles for MuRFs, possibly in transcriptional regulation and protein synthesis, which is consistent with their nuclear localization [23, 171].

2.5.3. MuRF-3

MuRF-3 localizes to the M-band by heterodimerizing with MuRF-1 or MuRF-2 [163]. Homozygous deletion of MuRF-3 in mice reveals its role in sarcomeric organization, as evidenced by increased sarcomeric length and upregulation of select proteins, including FHL-2 [172]. In spite of the increased sarcomeric length, MuRF-3 null mice do not exhibit cardiac hypertrophy in the absence of stress [172]. However, MuRF-3 null hearts are more prone to rupture following myocardial infarction [172]. Moreover, double knock-out mice of MuRF-1 and MuRF-3 exhibit skeletal myopathy and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, as shown by accumulation of myosin at the subsarcolemma region, myofiber fragmentation, and reduced muscle contractility [158]. Interestingly, Z-disks, but not M-bands, are disrupted in the MuRF-1/MuRF-3 double knock-out mice [158]. Since MuRF-2 is present at M-bands, but not Z-disks, it is possible that it may compensate for the loss of MuRF-1 and MuRF-3 with regards to protein turnover, thus contributing to the maintenance of M-band organization. This is consistent with MuRF proteins having redundant functions, at least partially, and highlights the importance of regulated proteasomal degradation in myofilament organization and contractility.

In addition to the MuRF family, another E3 ubiquitin ligase, cullin-3, is involved in the proteasomal degradation of small Ankyrin 1 (sAnk1), an integral membrane protein of the network sarcoplasmic reticulum that overlies M-bands and Z-disks [66]. However, since cullin-3 is localized at Z-disks rather than M-bands [66], it is highly possible that this process takes place at the former rather than the latter structure.

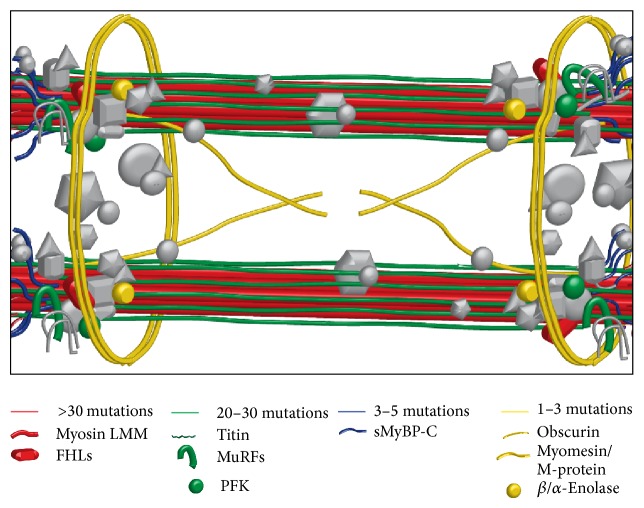

3. Cardiac and Skeletal Myopathies Associated with M-Band Proteins

A significant percentage of skeletal and cardiac myopathies are linked to genetic mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric, metabolic, and enzymatic proteins [173–176], many of which are localized to the M-region (Figure 2). Herein, we present a comprehensive overview of mutations associated with sarcomeric proteins of the M-region. In particular, we summarize early and current literature on genes encoding M-region related proteins that are heavily mutated (referring the reader to focused reviews) (Tables 2 and 3) and emphasize the emerging roles of genes recently implicated in the development of skeletal and cardiac myopathies.

Figure 2.

M-region proteins associated with skeletal and cardiac myopathies. Schematic representation of sarcomeric M-region proteins linked to the development of skeletal and cardiac myopathies. Proteins exhibiting no known disease-linked mutations are shown in grey color.

Table 2.

Disease-causing mutations in genes encoding structural proteins of the M-region.

| Protein | Mutation | Region on protein | Effect | Disease | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHL-1 | K45SfsX1 | LIM domain 1 | Unknown | HCM | [177] |

| FHL-1 | R95W | Linker region between LIM domain 1 and 2 | Unknown | RBM | [178] |

| FHL-1 | C101F | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | RBM | [179] |

| FHL-1 | 102–104 del KFC | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | RBM | [179] |

| FHL-1 | C104R/Y | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | RBM | [179, 180] |

| FHL-1 | 111–229 del ins G | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | EDMD | [181] |

| FHL-1 | N112FfsX51 | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | EDMD | [181] |

| FHL-1 | W122S/C | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | SPM | [182, 183] |

| FHL-1 | H123Y/Q/L/R | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | RBM | [178, 184–186] |

| FHL-1 | K124RfsX6 | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | EDMD | [181] |

| FHL-1 | F127 ins 128I | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | XMPMA | [187] |

| FHL-1 | C132F | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | RBM | [186] |

| FHL-1 | C150Y/R/S | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | RBM | [179, 185, 188] |

| FHL-1 | 151–153 del VTC | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | RSS | [179] |

| FHL-1 | C153Y/R/S/W | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | RBM | [186] |

| FHL-1 | 153Stop | LIM domain 2 | Unknown | HCM | [177] |

| FHL-1 | Delete exon 6 ins 84 bp | LIM domain 3 | Loss of full length FHL-1A, increase in FHL-1C | EDMD | [189] |

| FHL-1 | K157VfsX36 | LIM domain 3 | Unknown | EDMD | [181] |

| FHL-1 | A168GfsX195 | LIM domain 3 | Unknown | XMPMA | [187] |

| FHL-1 | 194Stop | LIM domain 3 | Premature stop codon and truncated protein corresponding to FHL-1C | XMPMA | [190] |

| FHL-1 | 198Stop | LIM domain 3 | Unknown | HCM | [191] |

| FHL-1 | F200fs32X | LIM domain 3 | Unknown | HCM | [192] |

| FHL-1 | C209R | LIM domain 3 | Unknown | EDMD/HCM | [181, 193] |

| FHL-1 | C224W | LIM domain 4 | Unknown | XMPMA | [187] |

| FHL-1 | H246Y | LIM domain 4 | Unknown | XMPMA | [190] |

| FHL-1 | C273LfsX11 | LIM domain 4 | Unknown | EDMD | [181] |

| FHL-1 | C276Y | LIM domain 4 | Unknown | EDMD | [181] |

| FHL-1 | C276S | LIM domain 4 | Unknown | HCM | [177] |

| FHL-1 | V280M | NLS of FHL-1B | Unknown | XMPMA | [190] |

| FHL-1 | E281Stop | Extreme COOH-terminus | Unknown | EDMD | [181] |

| FHL-2 | G48S | LIM domain 1 | Loss of titin binding | DCM | [194] |

| sMyBP-C | W236R | M-motif | Loss of actin and myosin binding | DA-1 | [195] |

| sMyBP-C | R318Stop | IgC2 | Premature stop codon and truncated protein | LCCS4 | [196] |

| sMyBP-C | Y856H | IgC8 | Loss of myosin binding | DA-1 | [195] |

| MyH 3 | 841-841 del L | LMM | Reduced catalytic activity | DA Sheldon-Hall syndrome | [197] |

| MyH 6 | A1004S E1457K |

LMM | Unknown | DCM | [198] |

| MyH 6 | Q1065H | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [198] |

| MyH 6 | R1116S A1366D A1443D R1865Q |

LMM | Unknown | CHD | [199] |

| MyH 7 | 847-847 del K | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | M852T | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [201] |

| MyH 7 | R858C | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | R869G | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [201] |

| MyH 7 | R870H | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [202] |

| MyH 7 | 883-883 del E | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [201] |

| MyH 7 | E894G | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | D906G | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [203] |

| MyH 7 | L908V | LMM | Unknown | HCM with CCD | [204] |

| MyH 7 | E921K | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | E924K E949K |

LMM | Unknown | HCM | [205] |

| MyH 7 | D928V | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [206] |

| MyH 7 | E931K | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | E935K | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [207] |

| MyH 7 | D953H | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | T1019N | LMM | Unknown | DCM | [208] |

| MyH 7 | R1053Q | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [209] |

| MyH 7 | G1057S | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | L1135R |

LMM | Unknown | HCM | [201] |

| MyH 7 | R1193S | LMM | Unknown | DCM | [208] |

| MyH 7 | E1218Q | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [201] |

| MyH 7 | N1327K | LMM | Reduced α-helical content of the rod domain | HCM | [210] |

| MyH 7 | E1356K | LMM | Reduced α-helical content of the rod domain | HCM | [211] |

| MyH 7 | E1377M A1379T R1382W |

LMM | Unknown | HCM | [201] |

| MyH 7 | R1420W | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | E1426K | LMM | Unknown | DCM | [208] |

| MyH 7 | A1439P | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [212] |

| MyH 7 | K1459N | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | L1467V | LMM | Unknown | Congenital myopathy | [213] |

| MyH 7 | L1481P | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [214] |

| MyH 7 | R1500W | LMM | Reduced α-helical content of the rod domain | DCM | [215] |

| MyH 7 | R1500P 1617-1617 del K |

LMM | Unknown | Laing distal myopathy | [216] |

| MyH 7 | 1508-1508 del E | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [217] |

| MyH 7 | T1513S | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | Q1541P | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [214] |

| MyH 7 | E1555K | LMM | Reduced α-helical content of the rod domain | HCM | [218] |

| MyH 7 | R1588P | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [213] |

| MyH 7 | L1591P | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [219] |

| MyH 7 | L1597R | LMM | Unknown | Axial myopathy, contractual myopathy | [220] |

| MyH 7 | T1599P | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [214] |

| MyH 7 | A1603P | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [217] |

| MyH 7 | R1608P | LMM | Unknown | Congenital myopathy, HCM | [214] |

| MyH 7 | L1612P | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [214] |

| MyH 7 | 1617-1617 del K | LMM | Unknown | MPD1, DCM | [214, 216] |

| MyH 7 | R1634S | LMM | Unknown | DCM | [208] |

| MyH 7 | A1636P L1646P R1662P |

LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [214] |

| MyH 7 | A1663P | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [216] |

| MyH 7 | 1669-1669 del E | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [214] |

| MyH 7 | V1691M | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [201] |

| MyH 7 | L1706P | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [216] |

| MyH 7 | R1712W | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [210] |

| MyH 7 | L1723P | LMM | Unknown | CCD | [221] |

| MyH 7 | 1729-1729 del K | LMM | Unknown | Laing distal myopathy | [216] |

| MyH 7 | E1753K | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [210] |

| MyH 7 | A1766T | LMM | Unknown | LVNC | [222] |

| MyH 7 | E1768K | LMM | Increased α-helical content of the rod domain | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | S1776G | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [223] |

| MyH 7 | A1777T | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [201] |

| MyH 7 | 1784-1784 del K | LMM | Unknown | MPD1, MSM | [219, 224] |

| MyH 7 | L1793P | LMM | Destabilization of the thick filaments | HCM with MSD | [225, 226] |

| MyH 7 | 1793-1793 del L | LMM | Unknown | MPD1 | [214] |

| MyH 7 | E1801K | LMM | Unknown | MPD1, DCM, HCM | [214, 217] |

| MyH 7 | T1834M | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | R1845W | LMM | Alters interactions between filaments | MSM | [227] |

| MyH 7 | E1856K | LMM | Unknown | Late onset myopathy with cardiac involvement | [228] |

| MyH 7 | E1883K | LMM | Destabilization of the thick filaments | HCM | [226, 229] |

| MyH 7 | H1901L | LMM | Alters interactions between filaments | MSM | [230] |

| MyH 7 | E1914K | LMM | Unknown | DCM | [214] |

| MyH 7 | N1918K | LMM | Unknown | LVNC | [231] |

| MyH 7 | T1929M | LMM | Unknown | HCM | [200] |

| MyH 7 | Stop1936W | LMM | Unknown | MSM | [232] |

| Myomesin | Aberrant splicing of exon 17a | EH-motif | Premature stop codon and truncated protein | MD1 | [233] |

| Myomesin | V1490I | Ig12 | Reduced dimerization | HCM | [234] |

| Obscurin | R4344Q | Ig58 | Loss of titin binding | HCM | [235] |

| Titin | S33705LfsX4 | TK | Unknown | LGMD2J | [236] |

| Titin | N34020TfsX9 | TK | Increased structural stability of TK, loss of interactions with proteins partners of TK | MmD-HD | [175] |

| Titin | R34091W | TK | Unknown | HMERF | [23] |

| Titin | R34175Stop | MIg1 | Unknown | MmD-HD | [175] |

| Titin | 32664-32665 del ins K | MIg2 | Unknown | HCM | [237] |

| Titin | P34617QinsX3 | MIs2 | Unknown | CNM | [238] |

| Titin | R34637Q | MIg4 | Unknown | DCM | [239] |

| Titin | A32606fsX7 | MIg5 | Unknown | DCM | [240] |

| Titin | Q35176HfsX9 | MIg5 | Truncated titin | MmD-HD (EOMFC) | [241] |

| Titin | Q35278Stop | MIs4 | Unknown | MmD-HD | [175] |

| Titin | G35340VfsX65 | MIg6 | Unknown | CNM | [238] |

| Titin | 33710-33711 del ins K | MIg6 | Unknown | HCM | [237] |

| Titin | S35469SfsX11 | MIg7 | Unknown | MmD-HD | [175] |

| Titin | K35524RfsX22 | MIs6 | Unknown | MmD-HD (EOMFC) | [241] |

| Titin | 32986-32987 del ins K | MIg8 | Unknown | DCM | [240] |

| Titin | M35859T | MIs7 | Unknown | ARVC | [242] |

| Titin | S35883QfsX10 | MIs7 | Unknown | TMD | [243] |

| Titin | Q35927–35931W del ins VKQK | MIg10 | Truncated titin | TMD, LGMD2J, MD | [236, 244, 245] |

| Titin | H35946P | MIg10 | Unknown | TMD | [246] |

| Titin | I35947N | MIg10 | Unknown | TMD | [247] |

| Titin | L35956P | MIg10 | Unknown | TMD | [244] |

| Titin | K35963NfsX9 | MIg10 | Unknown | TMD, CNM | [238, 243] |

| Titin | Q35964Stop | MIg10 | Truncated titin | TMD | [243] |

Note: nomenclature refers to the canonical full-length human isoforms; FHL-1, NP_001153174.1, sMyBP-C, AAI43503.1, MyH 3, NP_002461.2, MyH 6, NP_002462.2, MyH 7, NP_000248.2, myomesin, CAF18565.1, obscurin, CAC44768.1, titin, NP_001254479.2. HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, RBM: reducing body myopathy, XMPMA: X-linked myopathy with postural muscle atrophy, SPM: scapuloperoneal myopathy, RSS: rigid spine syndrome, EDMD: Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy, DA-1: distal arthrogryposis type 1, LCCS4: lethal congenital contracture syndrome type 4, MPD1: Laing distal myopathy, CHD: congenital heart defect, CCD: central core disease, MSM: myosin storage myopathy, LVNC: left ventricular noncompaction, MD1: myotonic dystrophy type 1, LGMD2J: limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2J, MmD-HD: multiminicore disease with heart disease, HMERF: hereditary myopathy with early respiratory failure, CNM: centronuclear myopathy, EOMFC: early-onset myopathy with fatal cardiomyopathy, ARVC: arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, TMD: tibial muscular dystrophy, MD: muscle disease, NLS: nuclear localization sequence, TK: titin kinase, MIgX: titin M-band IgX, MyH: myosin heavy chain, and LMM: light meromyosin.

Table 3.

Proteins with enzymatic activity at the M-region and related diseases.

| Protein | Mutation | Effect | Disease | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Enolase | G156N G374E |

Unknown | GSD XIII | [248] |

| MuRF1 | S5L | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF1 | F73S | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF1 | R86C/H | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF1 | I101F | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF1 | T232M | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF1 | E299Stop | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF1 | M305I | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF1 | A318D | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | C50Y | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | P79A | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | Q187fs | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | L241M | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | S252F | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | E371fs | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | P392T | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | K425N | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | A488T | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | T506S | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | H523W | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF2 | F538fs | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF3 | P9L | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF3 | G94C | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF3 | P115S | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF3 | L163P | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF3 | A221V | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF3 | R249Q | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF3 | R269H | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF3 | K270N | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF3 | P346T | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| MuRF3 | G373D | Unknown | HCM | [249] |

| PFK | R39P/L | Unknown | GSD VII | [250, 251] |

| PFK | G57V | Unknown | GSD VII | [252] |

| PFK | G80fs4X | Unknown | GSD VII | [252] |

| PFK | R95Stop | Unknown | GSD VII | [253] |

| PFK | R100Q | Unknown | GSD VII | [254] |

| PFK | S108C | Unknown | GSD VII | [252] |

| PFK | G209D | Unknown | GSD VII | [254] |

| PFK | N309G | Unknown | GSD VII | [255] |

| PFK | D543A | Unknown | GSD VII | [250] |

| PFK | D591A | Unknown | GSD VII | [252] |

| PFK | P668Q | Unknown | GSD VII | [251] |

| PFK | W686C | Unknown | GSD VII | [254] |

| PFK | R696H | Unknown | GSD VII | [251] |

| PFK | 78 bp del exon 5 | Unknown | GSD VII | [254] |

| PFK | 5 or 12 bp del exon 7 | Unknown | GSD VII | [250] |

| PFK | 75 bp del exon 15 | Unknown | GSD VII | [256] |

| PFK | Retention of intron 13, truncated protein | Unknown | GSD VII | [257] |

| PFK | Retention of intron 16, truncated protein | Unknown | GSD VII | [257] |

| PFK | 169 bp del exon 19 | Unknown | GSD VII | [258] |

Note: nomenclature refers to the canonical full-length human isoforms; beta-enolase, NP_001967.3, MuRF1, NP_115977.2, MuRF2, Q9BYV6.2, MuRF3, NP_912730.2, PFK, and NP_000280.1. HCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; GSD: glycogen storage disease.

3.1. Cytoskeletal Proteins and M-Band Myopathies

3.1.1. Light Meromyosin

Hereditary myosin myopathies are a group of diseases caused by mutations in the heavy chain of myosin (MyHC) [259]. Mutations have been reported in the genes encoding three muscle-specific MyHC isoforms, including MYH7, which is expressed in slow-twitch skeletal and cardiac muscles, MYH3, which is abundantly expressed in embryonic skeletal muscles, and MYH6, which is selectively expressed in cardiac muscle [98]. Although multiple mutations have been identified along the entire length of MyHC [174, 214, 259], we only note those associated with the light meromyosin (LMM) portion of myosin that localizes to the M-band (Table 2). Over 86 disease-causing LMM mutations have been linked to the development of different skeletal and cardiac myopathies. Of those mutations, 78 map to MYH7 with 68 being missense mutations, 9 being insertions and/or deletions, and 1 being a nonsense mutation. Currently, the molecular alterations underlying the majority of these mutations are elusive.

3.1.2. Titin

Due to the development of next-generation sequencing, routine analysis of the giant titin gene (TTN) has been made possible. Consequently, TTN has emerged as a “hot spot” for inherited skeletal and cardiac myopathies affecting mankind [175]. Over 120 disease-causing titin mutations have been reported in patients with different skeletal and cardiac myopathies [175]. Of those mutations, 23 map to the M-band region of titin, a significant percentage given the relatively small size of titin's M-band region (~200 kDa) compared to the rest of the molecule (~2-3 MDa). Of these 23 mutations, 9 are frameshift, 3 are nonsense, 6 are missense, and 5 are insertions and/or deletions (Table 2). While the mutations associated with the development of cardiomyopathies affect several domains throughout the M-band portion of titin, the ones that are linked to skeletal myopathies are mainly contained within the last Ig domain of titin, MIg10 [260].

3.1.3. Obscurin

Mutations in OBSCN, the gene encoding giant obscurins, have been linked to the development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) [13, 261]. Specifically, the presence of a missense mutation results in an R4344Q substitution within the Ig58 domain of obscurin [235]. In vitro studies have shown that the R4344Q mutation results in decreased binding of obscurin Ig58/Ig59 domains to the titin Ig9/Ig10 domains, which localize at the Z/I junction. However, the pathological effects of this mutation on sarcomeric assembly or Ca2+ homeostasis are still unknown.

3.1.4. Myosin Binding Protein-C Slow

MYBPC1 encodes the slow isoform of MyBP-C and has been directly implicated in the development of severe and lethal skeletal myopathies [10, 195, 196]. Two autosomal dominant missense mutations have been identified to date, W236R and Y856H, which are linked to the development of distal arthrogryposis type-1 (DA1), a severe skeletal myopathy selectively affecting distal muscles [195]. Recent work from our group has demonstrated that the W236R and Y856H mutations abolish the ability of the NH2 and COOH termini, respectively, to bind native actin and/or myosin and to regulate the formation of actomyosin cross-bridges in vitro [262]. Moreover, MYBC1 has been causally associated with the development of lethal congenital contractual syndrome type-4 (LCCS4), a neonatal lethal form of arthrogryposis myopathy [196] that most likely results in a null phenotype. A homozygous nonsense mutation in the C2 domain of sMyBP-C (R318Stop) consists of the molecular basis of LCCS4. Given that all three mutations are encoded by exons that are constitutively expressed, they are present in all sMyBP-C variants, including those that carry a unique COOH-terminal insertion and preferentially localize to the periphery of the M-band [10, 263].

3.1.5. Myomesin

The gene that encodes myomesin, MYOM1, has been directly linked to the development of HCM [234]. Specifically, a missense mutation resulting in V1490I substitution within the COOH-terminal Ig12 domain reduces the ability of myomesin to homodimerize (Table 2). Although the molecular etiology of HCM due to the V1490I substitution is still unknown, it is likely that mutant myomesin fails to cross-link myosin thick filaments at the M-band [234].

In addition, myomesin has been associated with myotonic dystrophy type 1 (DM1), a multisystem disease characterized by myotonia, muscle weakness, cardiac conduction defects, insulin resistance, and mental retardation. DM1 is caused by expansion of a CTG repeat present in the 3′ UTR region of dystrophia myotonica-protein kinase, DMPK [264], resulting in aggregation of muscle blind-like (MBNL) protein. MBNL is an RNA binding protein that regulates the alternative splicing of the MYOM1 gene [233]. Specifically, exon 17a encoding the EH-motif that links the third and fourth FnIII domains of myomesin is developmentally regulated. In normalcy, exon 17a is expressed in embryonic heart, while in heart failure it is also expressed in adult myocardium, as a compensatory mechanism to render the heart muscle more compliant [265, 266]. In the case of DM1 patients, loss of MBNL function leads to inclusion of exon 17a in adult cardiac muscle resulting in expression of a myomesin form that compromises the ability of the afflicted muscles to withstand stress and generate force [233].

3.1.6. Four and a Half LIM (FHL) Domain Proteins

FHL-1 and FHL-2 have been directly linked to the development of skeletal and cardiac myopathies [176, 267]. Mutations in the FHL1 gene, encoding FHL-1, have been linked to the development of five distinct skeletal muscle diseases, including reducing body myopathy (RBM), X-linked myopathy with postural muscle atrophy (XMPMA), scapuloperoneal myopathy (SPM), rigid spine syndrome (RSS), and Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD) [176]. Since a number of thorough reviews on FHL-1 associated myopathies have been published prior to 2011 [176, 184, 267], we will focus our discussion on new information, originating after 2011. For consistency purposes, a complete listing of all known FHL-1 mutations to date is listed in Table 2.

Since 2011, six additional mutations in FHL-1 have been linked to the development of RBM and EDMD, increasing the total number of FHL-1 skeletal myopathy linked mutations from 29 prior to 2011 to 35 after 2011. Specifically, RBM linked mutation R95W is located within the linker region between LIM domains 1 and 2, while C104Y, H123R, C126Y, and C153S/W substitutions are present in LIM domain 2 [178, 180, 268]. Moreover, deletion of exon 6 resulting in loss of full length FHL-1 was linked to the development of EDMD [189]. Recently, Binder et al. demonstrated that patients, who presented with XMPMA due to mutations in the FHL1 gene, also suffer from reduced cardiac function [269]. This was observed in hemizygote males as well as heterozygote females carrying one of the following mutations, C224W, H246Y, V280M, and A168fsX195 [269].

Furthermore, six novel mutations in FHL-1 have been directly linked with the development of HCM, by generating truncated or deleterious FHL-1 proteins. These include 2 frameshift mutations at residues 45 and 200 within LIM domains 1 and 3, respectively, 2 nonsense mutations generating premature termination codons at residues 153 and 198 within LIM domains 2 and 3, respectively, and 2 missense mutations, C209R and C276S, both located within LIM domain 3 [177, 191, 192]. In addition to the expression of truncated or poisonous forms of FHL-1, the levels of FHL-1 are also altered in cardiomyopathies. In particular, patients with HCM exhibit ~2-fold increased expression of FHL1, with a subsequent increase in protein levels of FHL-1 [270], while patients diagnosed with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) show a ~3.5-fold decrease in the levels of FHL-1 transcripts resulting in reduced protein expression [271].

Although mutations in FHL-1 protein are commonly linked to the development of skeletal and cardiac myopathies, we are just beginning to unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of these myopathies. Recently, Wilding et al. showed that select RBM (H123Y, C132F, and C153Y), SPM (W122S), and XMPMA (F127 ins 128I and C224W) FHL-1 mutants accumulate in reducing bodies or protein aggregates when overexpressed in C2C12 cells [272]. These reducing bodies are phenotypically similar to those found in patients suffering from the corresponding diseases. In addition, these same mutations result in impaired myoblast differentiation when overexpressed in C2C12 cells, consistent with the loss of normal FHL-1 function [272]. Conversely, select EDMD (K157VfsX36, C273LfsX11, C276Y, and E281Stop) and EDMD/HCM (C209R) FHL-1 mutations result in reduced protein expression when overexpressed in C2C12 cells, suggesting impaired transcriptional regulation and/or protein stability and degradation [272]. Thus, these studies are the first to suggest potential molecular alterations that underlie the different FHL-1 linked myopathies.

FHL-2 has also been associated with heart failure progression and the development of DCM. A missense mutation, G48S, in the first LIM domain of FHL-2 has been identified in a patient with familial DCM [194] (Table 2). The presence of this mutation reduces the ability of mutant FHL-2 protein to bind titin, suggesting a structural role for FHL-2 at the M-band.

3.2. Metabolic Enzymes and M-Band Myopathies

In addition to alterations in genes encoding cytoskeletal proteins, mutations in the metabolic enzymes PFK, β-enolase, and AMPD that localize at the M-band have been linked to the development of skeletal and cardiac myopathies; this group of diseases is collectively classified as “metabolic myopathies.” Affected individuals present with muscle weakness, occasionally triggered by exercise, chronic respiratory failure, muscle rigidity, and decreased voluntary contractions [273]. Tarui disease, also referred to as glycogen storage disease (GSD) type VII, is a rare disorder involving impaired glycogen metabolism due to PFK deficiency and is characterized by exercise intolerance, myalgias, muscle cramps, and episodic myoglobinuria [252]. To date, 21 mutations in the PFK gene have been linked to the development of Tarui/GSD type VII disease (Table 3) [252, 255] (for a thorough discussion on Tarui disease and the molecular details of the identified mutations, please see [252]). Another form of GSD, referred to as GSD type XIII, is linked to defects in β-enolase. Two missense mutations (G156N and G374E) in the β-enolase gene have been linked to the development of GSD type XIII. These mutations result in decreased protein levels leading to a dramatic reduction (~95%) in cellular enolase activity [248] (Table 3).

Lastly, missense and truncation mutations in the human AMPD1 gene have been linked with AMPD deficiency in skeletal muscle [274–277]. Specifically, the Q12X nonsense mutation gives rise to a premature stop codon leading to the generation of truncated mRNA and loss of AMPD-1 protein [275]. In addition, the P48L, Q156H, K287I, R388W, and R425H missense mutations result in expression of mutant AMPD-1 proteins with negligible enzymatic activity [274, 276, 277], while a deletion mutation (IVS2 del CTTT) leads to expression of multiple inactive spliced forms of the protein [277]. While loss of AMPD-1 may be partially compensated by isoforms encoded by AMPD3 [278], the importance of AMPD-1 in maintaining optimal AMP levels is underscored by the severe effects of many of these disease-linked mutations.

3.3. Ubiquitin Ligases and M-Band Myopathies

3.3.1. MuRFs

It is only very recently that mutations in members of the MuRF family have been linked to the development of hypertrophic cardiomyopathies. Su et al. recently identified 8, 12, and 10 mutations in MuRF-1, MuRF-2, and MuRF-3 genes, respectively (Table 3) [249]. Interestingly, these mutations are suggested to modify the severity of the HCM phenotype but not cause it per se. Moreover, select HCM linked MuRF-1 and MuRF-2 mutations cosegregate with mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins, that is, MYH7, MYBPC3, MYC2, and MYL3. However, the contribution of these MuRF-1 and MuRF-2 mutations in the pathogenesis of HCM is still unknown.

In addition, the expression profile of MuRF-1 is differentially regulated in response to pathophysiological processes, such as aging, atrophy, and senescence. Specifically, the levels of MuRF-1 are significantly increased in the initial phases of muscle disuse and atrophy in humans; this is consistent with a decrease in muscle fiber size [279]. Conversely, in aged skeletal muscle, the levels of MuRF-1 are decreased, coinciding with slowing of muscle atrophy [279]. Moreover, muscle loss is often associated with chronic diseases, such as cirrhosis and heart failure. Muscle biopsies obtained from malnourished cirrhotic patients exhibiting muscle atrophy contain increased amounts of MuRF-1 [280]. Similarly, MuRF-1's expression is upregulated in skeletal muscles of patients with chronic heart failure [281]. However, this trend is reversed in the same patients following exercise training [281].

Although the molecular etiologies underlying the differential expression of the MuRF proteins in skeletal and cardiac myopathies are yet to be defined, it is apparent that they play key roles in regulating muscle fiber size and muscle loss [282].

4. Perspectives and Future Directions

Throughout the last decade, it has become clear that in addition to its structural role, the M-region also acts as a mechanosensor, signal transduction center, and metabolic hub (Figure 1 and Table 1). Distinct mutations or alterations in the expression levels of M-band proteins have been implicated in the development of skeletal and cardiac muscle diseases. To date, more than 210 distinct mutations affect proteins that localize to the M-region. Notably, a striking 163 missense and nonsense mutations, 21 frameshift mutations, and 26 deletions/insertions within genes encoding M-region related proteins (Figure 2 and Tables 2 and 3) have been associated with the development of different forms of skeletal and cardiac myopathies. The severity of these diseases can vary dramatically, depending on the nature of the mutation and the role of the affected protein. Our current understanding of the molecular pathophysiology of individual mutations is still incomplete and only just emerging in most cases. Deciphering how these mutations alter M-band structure, contractile activity, signaling networks, posttranslational modifications, and energy production will aid in improving clinical diagnosis and developing individualized therapeutic approaches for affected individuals.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants to Li-Yen R. Hu (NIH, 5 T32AR7592), Maegen A. Ackermann (NIH, K99 KHL116778A), and Aikaterini Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos (AHA, 14GRNT20380360).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Eppenberger H. M., Perriard J.-C. Developmental Processes in Normal and Diseased Muscle. Basel, Switzerland: S. Karger AG; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjöström M., Squire J. M. Cryo-ultramicrotomy and myofibrillar fine structure: a review. Journal of Microscopy. 1977;111(3):239–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1977.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AL-Khayat H. A., Kensler R. W., Morris E. P., Squire J. M. Three-dimensional structure of the M-region (bare zone) of vertebrate striated muscle myosin filaments by single-particle analysis. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2010;403(5):763–776. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luther P., Squire J. Three dimensional structure of the vertebrate muscle M region. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1978;125(3):313–324. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90405-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarkova I., Ehler E., Lange S., Schoenauer R., Perriard J.-C. M-band: a safeguard for sarcomere stability? Journal of Muscle Research and Cell Motility. 2003;24(2-3):191–203. doi: 10.1023/a:1026094924677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obermann W. M. J., Gautel M., Steiner F., van der Ven P. F. M., Weber K., Fürst D. O. The structure of the sarcomeric M band: localization of defined domains of myomesin, M-protein, and the 250-kD carboxy-terminal region of titin by immunoelectron microscopy. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1996;134(6):1441–1453. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.6.1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenny P. A., Liston E. M., Higgins D. G. Molecular evolution of immunoglobulin and fibronectin domains in titin and related muscle proteins. Gene. 1999;232(1):11–23. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schoenauer R., Lange S., Hirschy A., Ehler E., Perriard J.-C., Agarkova I. Myomesin 3, a novel structural component of the M-band in striated muscle. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2008;376(2):338–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A., Jones E. M., van Rossum D. B., Bloch R. J. Obscurin is a ligand for small ankyrin 1 in skeletal muscle. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2003;14(3):1138–1148. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e02-07-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackermann M. A., Hu L.-Y. R., Bowman A. L., Bloch R. J., Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A. Obscurin interacts with a novel isoform of MyBP-C slow at the periphery of the sarcomeric M-band and regulates thick filament assembly. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2009;20(12):2963–2978. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-12-1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bagnato P., Barone V., Giacomello E., Rossi D., Sorrentino V. Binding of an ankyrin-1 isoform to obscurin suggests a molecular link between the sarcoplasmic reticulum and myofibrils in striated muscles. Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;160(2):245–253. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flick M. J., Konieczny S. F. The muscle regulatory and structural protein MLP is a cytoskeletal binding partner of betaI-spectrin. Journal of Cell Science. 2000;113, part 9:1553–1564. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.9.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A., Ackermann M. A., Bowman A. L., Yap S. V., Bloch R. J. Muscle giants: molecular scaffolds in sarcomerogenesis. Physiological Reviews. 2009;89(4):1217–1267. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarkova I., Perriard J.-C. The M-band: an elastic web that crosslinks thick filaments in the center of the sarcomere. Trends in Cell Biology. 2005;15(9):477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fürst D. O., Osborn M., Nave R., Weber K. The organization of titin filaments in the half-sarcomere revealed by monoclonal antibodies in immunoelectron microscopy: a map of ten nonrepetitive epitopes starting at the Z line extends close to the M line. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1988;106(5):1563–1572. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.5.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gautel M., Leonard K., Labeit S. Phosphorylation of KSP motifs in the C-terminal region of titin in differentiating myoblasts. The EMBO Journal. 1993;12(10):3827–3834. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06061.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labeit S., Kolmerer B., Linke W. A. The giant protein titin: emerging roles in physiology and pathophysiology. Circulation Research. 1997;80(2):290–294. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.2.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernando P., Sandoz J. S., Ding W., et al. Bin 1 Src homology 3 domain acts as a scaffold for myofiber sarcomere assembly. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(40):27674–27686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m109.029538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wechsler-Reya R. J., Elliott K. J., Prendergast G. C. A role for the putative tumor suppressor Bin1 in muscle cell differentiation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1998;18(1):566–575. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mao N.-C., Steingrimsson E., Duhadaway J., et al. The murine Bin1 gene functions early in myogenesis and defines a new region of synteny between mouse chromosome 18 and human chromosome 2. Genomics. 1999;56(1):51–58. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller A. J., Baker J. F., DuHadaway J. B., et al. Targeted disruption of the murine Bin1/Amphiphysin II gene does not disable endocytosis but results in embryonic cardiomyopathy with aberrant myofibril formation. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2003;23(12):4295–4306. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.12.4295-4306.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Labeit S., Gautel M., Lakey A., Trinick J. Towards a molecular understanding of titin. The EMBO Journal. 1992;11(5):1711–1716. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lange S., Xiang F., Yakovenko A., et al. Cell biology: the kinase domain of titin controls muscle gene expression and protein turnover. Science. 2005;308(5728):1599–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.1110463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A., Catino D. H., Strong J. C., et al. Obscurin modulates the assembly and organization of sarcomeres and the sarcoplasmic reticulum. The FASEB Journal. 2006;20(12):2102–2111. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5761com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A., Catino D. H., Strong J. C., Randall W. R., Bloch R. J. Obscurin regulates the organization of myosin into A bands. American Journal of Physiology—Cell Physiology. 2004;287(1):C209–C217. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00497.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borisov A. B., Sutter S. B., Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A., Bloch R. J., Westfall M. V., Russell M. W. Essential role of obscurin in cardiac myofibrillogenesis and hypertrophic response: evidence from small interfering RNA-mediated gene silencing. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 2006;125(3):227–238. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu L.-Y. R., Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A. The kinase domains of obscurin interact with intercellular adhesion proteins. The FASEB Journal. 2013;27(5):2001–2012. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-221317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiong G., Qadota H., Mercer K. B., McGaha L. A., Oberhauser A. F., Benian G. M. A LIM-9 (FHL)/SCPL-1 (SCP) complex interacts with the C-terminal protein kinase regions of UNC-89 (obscurin) in Caenorhabditis elegans muscle. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2009;386(4):976–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cunha S. R., Mohler P. J. Obscurin targets ankyrin-B and protein phosphatase 2A to the cardiac M-line. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(46):31968–31980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m806050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhasin N., Cunha S. R., Mudannayake M., Gigena M. S., Rogers T. B., Mohler P. J. Molecular basis for PP2A regulatory subunit B56alpha targeting in cardiomyocytes. The American Journal of Physiology—Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2007;293(1):H109–H119. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00059.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qadota H., McGaha L. A., Mercer K. B., Stark T. J., Ferrara T. M., Benian G. M. A novel protein phosphatase is a binding partner for the protein kinase domains of UNC-89 (obscurin) in Caenorhabditis elegans . Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2008;19(6):2424–2432. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-01-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Obermann W. M. J., Gautel M., Weber K., Fürst D. O. Molecular structure of the sarcomeric M band: mapping of titin and myosin binding domains in myomesin and the identification of a potential regulatory phosphorylation site in myomesin. The EMBO Journal. 1997;16(2):211–220. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuzawa A., Lange S., Holt M., et al. Interactions with titin and myomesin target obscurin and obscurin-like 1 to the M-band-Implications for hereditary myopathies. Journal of Cell Science. 2008;121(11):1841–1851. doi: 10.1242/jcs.028019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auerbach D., Bantle S., Keller S., et al. Different domains of the M-band protein myomesin are involved in myosin binding and M-band targeting. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1999;10(5):1297–1308. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.5.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tskhovrebova L., Trinick J. Making muscle elastic: the structural basis of myomesin stretching. PLoS Biology. 2012;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001264.e1001264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obermann W. M. J., Plessmann U., Weber K., Furst D. O. Purification and biochemical characterization of myomesin, a myosin-binding and titin-binding protein, from bovine skeletal muscle. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1995;233(1):110–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.110_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noguchi J., Yanagisawa M., Imamura M., et al. Complete primary structure and tissue expression of chicken pectoralis M-protein. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1992;267(28):20302–20310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steiner F., Weber K., Fürst D. O. Structure and expression of the gene encoding murine M-protein, a sarcomere-specific member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Genomics. 1998;49(1):83–95. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grove B. K., Cerny L., Perriard J. C., Eppenberger H. M. Myomesin and M-protein: expression of two M-band proteins in pectoral muscle and heart during development. Journal of Cell Biology. 1985;101(4):1413–1421. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grove B. K., Holmbom B., Thornell L. E. Myomesin and M protein: differential expression in embryonic fibers during pectoral muscle development. Differentiation. 1987;34(2):106–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1987.tb00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carlsson E., Grove B. K., Wallimann T., Eppenberger H. M., Thornell L.-E. Myofibrillar M-band proteins in rat skeletal muscles during development. Histochemistry. 1990;95(1):27–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00737225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Obermann W. M. J., van der Ven P. P. M., Steiner F., Weber K., Fürst D. O. Mapping of a myosin-binding domain and a regulatory phosphorylation site in M-protein, a structural protein of the sarcomeric M band. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1998;9(4):829–840. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.4.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Drexler H. C. A., Ruhs A., Konzer A., et al. On marathons and Sprints: an integrated quantitative proteomics and transcriptomics analysis of differences between slow and fast muscle fibers. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2012;11(6) doi: 10.1074/mcp.m111.010801.M111.010801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]