Abstract

Purpose

The available scientific research regarding injury prevention practices in international football is sparse. The purpose of this study was to quantify current practice with regard to (1) injury prevention of top-level footballers competing in an international tournament, and (2) determine the main challenges and issues faced by practitioners in these national teams.

Methods

A survey was administered to physicians of the 32 competing national teams at the FIFA 2014 World Cup. The survey included 4 sections regarding perceptions and practices concerning non-contact injuries: (1) risk factors, (2) screening tests and monitoring tools, (3) preventative strategies and (4) reflection on their experience at the World Cup.

Results

Following responses from all teams (100%), the present study revealed the most important intrinsic (previous injury, accumulated fatigue, agonist:antagonist muscle imbalance) and extrinsic (reduced recovery time, training load prior to and during World Cup, congested fixtures) risk factors during the FIFA 2014 World Cup. The 5 most commonly used tests for risk factors were: flexibility, fitness, joint mobility, balance and strength; monitoring tools commonly used were: medical screen, minutes/matches played, subjective and objective wellness, heart rate and biochemical markers. The 5 most important preventative exercises were: flexibility, core, combined contractions, balance and eccentric.

Conclusions

The present study showed that many of the National football (soccer) teams’ injury prevention perceptions and practices follow a coherent approach. There remains, however, a lack of consistent research findings to support some of these perceptions and practices.

Keywords: Football, Risk factor, Testing, Soccer

Introduction

Injury prevention in top-level football is of utmost importance given the negative outcomes borne out in reduced performance,1 2 financial impact3 and long-term health of players.4 To overcome the significant cost due to injuries as well as reduce the early onset of degenerative changes, sports medicine and science should ideally assist practitioners in the identification of important risk factors for injury occurrence and aid in the provision of evidence-based preventative recommendations. However, scientific investigations and information from the elite echelons of world football are sparse and much remains unknown in this domain.5 6

Two studies5 6 have started the process of quantifying the actual practices of top-level football organisations in order to provide recommendations on how to align injury risk factors with preventative practices in professional club settings. The first5 surveyed the perceptions and practices of premier league clubs worldwide and revealed the most important perceived risk factors (previous injury, fatigue, muscle imbalance), alongside the most commonly used screening tests (functional movement screen, questionnaires, isokinetic muscle testing) and preventative exercises (eccentric, specific hamstring eccentric focused, balance/proprioception) included in their injury prevention programmes. The second study6 systematically reviewed the scientific evidence underpinning these most important perceptions and practices. The authors showed that the majority of these perceptions and practices did not possess a strong level of scientific evidence or graded recommendation for use in the practical setting. Regardless, these studies represent football in the specific context of professional clubs where the training programmes, logistical demands and available facilities differ from those in competitions involving national teams, such as at the FIFA World Cup. While injury rates in the FIFA World Cups have significantly declined in each subsequent tournament since 1998,7 the time-loss match injury rates remain higher in comparison to those reported as per professional club standards (40.0/1000 h vs 26.7/1000 h, respectively).7 8 The differences in injury rates could be explained by several factors; accumulated fatigue as the World Cups are contested following a full competitive club season, changes in training style and the high level of player competitiveness at the most important tournament worldwide.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to quantify current practice with regard to (1) injury prevention of top-level footballers competing in the FIFA 2014 World Cup, and (2) determine the challenges faced by practitioners in implementing their injury prevention programmes.

Methods

Participants

National team physicians of the 32 teams competing at the FIFA 2014 World Cup in Brazil were invited to participate in this structured survey. An invitation was emailed to the physicians of all 32 national team federations on 20 December 2014 introducing the concept and objectives of the survey, and provided a web link to access the survey.

Physicians were asked to submit their response online. If a question was unanswered, it was excluded from the analysis. Data were collected retrospectively between 20 December 2014 and 1 February 2015. All physicians ‘consented to participate’. The list of participating national teams is presented in table 1. When there was more than one physician in a team, both physicians were asked to complete one survey with collaborative input.

Table 1.

The 32 national teams competing at the FIFA 2014 World Cup (according to FIFA confederation)

| AFC | CAF | CONCACAF | CONMEBOL | UEFA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Algeria | Costa Rica | Argentina | Belgium |

| Iran | Cameroon | Honduras | Brazil | Bosnia-Herzegovina |

| Japan | Ghana | Mexico | Chile | Croatia |

| South Korea | Ivory Coast | USA | Colombia | England |

| Nigeria | Ecuador | France | ||

| Uruguay | Germany | |||

| Greece | ||||

| Italy | ||||

| Netherlands | ||||

| Portugal | ||||

| Russia | ||||

| Spain | ||||

| Switzerland |

AFC, Asian Football Confederation; CAF, Confederation Africaine de Football; CONCACAF, Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football; CONMEBOL, Confederación Sudamericana de Fútbol, UEFA, Union of European Football Associations.

Survey

The survey was constructed in English, French and Spanish and administered via an online survey software (Survey Monkey, http://www.surveymonkey.net) and consisted of 27 questions (17 closed ended and 10 open ended; see online supplementary appendix A) with four sections: (1) perceived risk factors for non-contact injuries, (2) screening tests and monitoring tools used to identify non-contact injury risk, (3) non-contact injury prevention strategies used, perceived effectiveness and implementation strategies, and (4) reflection on the effectiveness of injury prevention strategies, challenges faced and future directions for research. The questions were designed by six experts—three sport scientists, two physicians and a sports medicine specialist. The design of questions took into consideration their combined knowledge and experience of sports medicine, and the science in professional and international football, in addition to their work in peer-reviewed research and implementing survey-based research. The survey was pilot tested with two national team physicians before the official invitations were sent. Following the pilot survey, four questions pertaining to ‘psychological strategies’ were added.

Survey analysis

The raw data was exported from Survey Monkey to Microsoft excel and analysed independently by the research team. To calculate the overall importance of risk factors, points were awarded based on a scale developed for previous survey research.5 Each time a physician rated a risk factor ‘very important’, it was awarded 3 points; ‘important’—2 points; ‘somewhat important’—1 point; ‘not sure’—0.5 points and ‘not important’—0 point. Points were then summed up and risk factors ranked in order of highest summed points to the lowest. A similar method was used to determine the ‘5 most important preventative exercises’. Physicians were asked to rank in order of importance (1st to 5th) the preventative exercises they considered the most important in their injury prevention programme. Points were awarded based on a scale developed for the previous survey research:5 exercises rated in first position were given 5 points, second—4 points, third—3 points, fourth—2 points; and fifth—1 point. Points for each exercise were summed and ranked in order, from highest to lowest. Regarding open-ended questions, individual responses were subjectively analysed for similarities and were grouped by the lead author (AM) into the appropriate overall category.

Results

Survey

Background information

All (100%) physicians submitted survey responses. Thirty-two surveys based on the perceptions and practices of 37 physicians were included for analysis (5 teams with 2 physicians).

Perceived non-contact injury risk factors

As based on national team physicians’ perceived rating of importance, the five most important ‘intrinsic’ and ‘extrinsic’ risk factors for non-contact injury are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Top five most importantly perceived intrinsic and extrinsic non-contact injury risk factors according to physicians of 32 national teams

| Rank | Intrinsic Risk Factor | Accumulated points of importance |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | Previous Injury | 85 |

| 2nd | Accumulated fatigue (i.e. throughout season / congested fixtures) | 77 |

| 3rd | Muscle imbalance (Agonist:Antagonist) | 76 |

| 4th | Physical fitness | 70 |

| 5th | Balance / coordination | 69 |

| Rank | Extrinsic Risk Factor | Accumulated points of importance |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | Reduced recovery time between matches | 76 |

| 2nd | Training load in clubs prior to the World Cup | 73 |

| Joint 3rd | Training load during World Cup Congested match schedule |

66 |

| Joint 4th | Number of matches played during club season Poor pitch quality |

65 |

| 5th | Recovery facilities | 64 |

Assessment and monitoring of injury risk

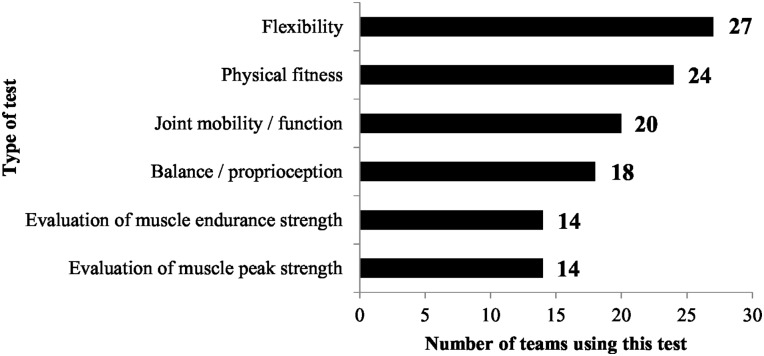

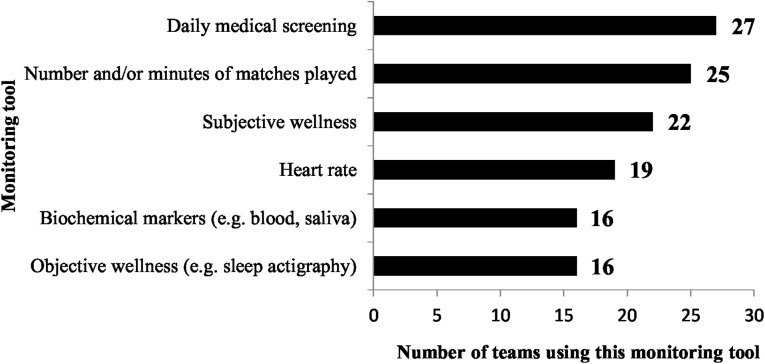

All 32 teams confirmed undertaking testing and monitoring of their players during both the pre-training camp and World Cup tournament. A total of 30 (94%) teams confirmed that they assessed and determined injury risk based on an ‘individual player risk profile’. The five most commonly used injury-screening tests and monitoring tools are presented in figures 1 and 2 (respectively).

Figure 1.

Top five most common injury risk screening tests used by national teams.

Figure 2.

Top five most commonly used monitoring tools for national teams.

Injury prevention strategies

Twenty-nine (91%) teams implemented an exercise-based injury prevention programme. Twenty-eight (97%) of these teams individualised the exercise programme according to players’ individual injury risk profile determined from testing conducted prior to their World Cup camp. Of the teams implementing an exercise prevention programme, 24 (83%) did so in both the training camp leading up to the World Cup and during the World Cup tournament, while only 4 (14%) teams implemented their exercise programme solely during the training camp.

Difference in exercise programming variables between training camp and World Cup tournament

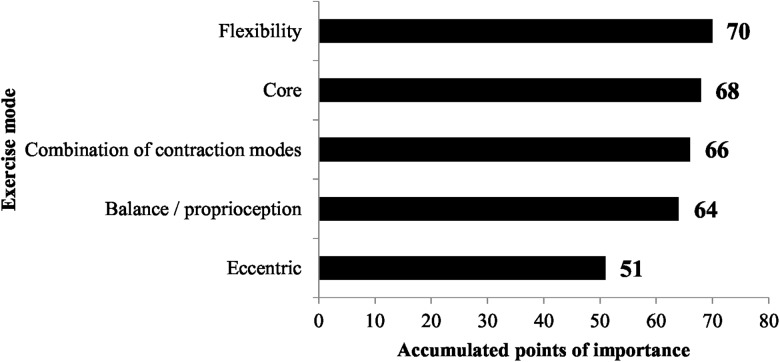

The variables selected by physicians (and % selected) explaining modifications made by teams to their exercise programme during the World Cup tournament were; (1) modifying the exercise type (76%), (2) reducing the external load (76%), (3) reducing the frequency (68%), and (4) reducing the sets and repetitions (60%). In addition to the above exercise prescription adjustments, physicians also listed the five most important injury prevention exercises used (figure 3). Altogether, 14 (44%) teams implemented strategies to reduce injuries by addressing the psychology of the player. Psychologically focused preventative strategies specifically targeted anxiety (93% of teams), motivation (64%), coping (57%), and stress (50%).

Figure 3.

Top five injury prevention exercises used by national teams.

Compliance to injury assessment and prevention

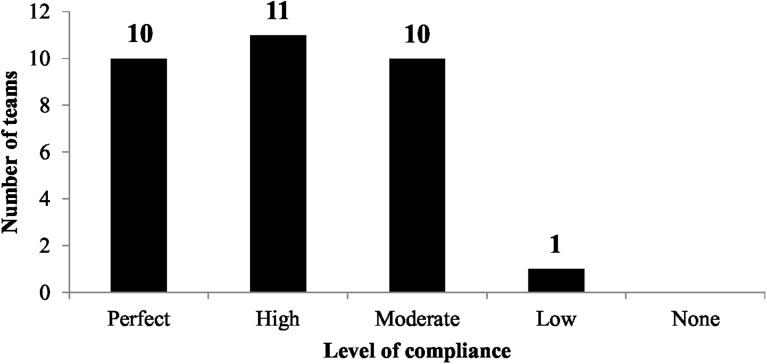

Physicians’ perceived ‘importance’ of coach compliance to their injury prevention practices is detailed in table 3. Furthermore, figure 4 shows the level of coach compliance to the individualisation of players’ training programme and recommendations for injury prevention as rated by physicians.

Table 3.

National team physicians’ perceptions of the importance of coach compliance in successfully preventing injuries

| Importance of ‘coach compliance’ | Number of teams |

|---|---|

| Essential (we cannot prevent injuries without it) | 15 (47%) |

| Very important (but we can still prevent some injuries) | 17 (53%) |

| Somewhat important (it can help but it is not essential) | 0 |

| Not important (it does not make any difference to preventing injuries) | 0 |

Figure 4.

Coaches level of compliance to individualisation of player programmes.

Efficacy of and challenges to preventative strategies

Twenty-six (81%) national teams stated that they perceived their injury prevention strategies to be ‘effective at reducing/limiting injuries, however, could have been better’, while five (16%) stated that they ‘could not have done better’ and one team was ‘not sure’. Thirty (94%) national teams responded to the question ‘What were the main challenges faced in preventing injuries?’ These responses are grouped into nine main categories and listed in table 4.

Table 4.

Main challenges faced in regards to preventing injuries at the FIFA 2014 World Cup

| Main challenges faced in preventing injuries | Percentage of responding national teams stating this as a main challenge (%) |

|---|---|

| Optimising the individualisation of player programmes | 47 |

| Compliance of and between staff | 35 |

| Limited time to obtain adaptation from a prevention programme | 29 |

| Frequent travel | 24 |

| Frequent climate change and acclimatisation | 18 |

| Congested match fixtures and limited recovery time | 12 |

| Acceptance of players to use different methods | 12 |

| Coach realisation that he is integral to preventing injuries | 6 |

| Psychological repercussions of poor results | 6 |

Future sports medicine and science research to prevent injuries in a national team context?

Twenty-eight (88%) national teams responded to the question “How can future Sports Medicine & Science research help you in terms of preventing injuries in the national team context?”. These responses are categorised into six main responses (table 5).

Table 5.

Responses of national team physicians’ on where future sports medicine and science research should be targeted to provide meaningful applications to practitioners

| Area of research | Percentage of responding national teams stating this as an area for future research (%) | Specific comments |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention studies on preventative strategies | 35 | Specifically at the elite football level Randomised controlled trials |

| Develop tests that identify significant risk factors | 25 | At the elite level. That are simple and quick That require little equipment/facilities |

| Identify significant risk factors | 18 | Specifically at the elite football level |

| Provide educational resources for national teams on injury prevention | 11 | Congress, conference, seminars Traditional format, web based, videos Workshops Roundtables of national teams to share experiences |

| Determine the optimal recovery strategies | 7 | Must be applicable to International tournament context Easy and practical to implement in national team context |

| Investigations on how to maximise compliance and awareness in coaches and players | 7 | Specifically how to educate coaches, staff and players |

Discussion

The perceptions and practices of the physicians from the 32 national teams competing in the FIFA 2014 World Cup were surveyed with regards to risk factors, screening tests and preventative strategies for non-contact injuries in addition to their main challenges faced in preventing injuries. This study revealed the five most importantly perceived intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors, the five most commonly used tests and monitoring tools, and the five exercises with the greatest perceived importance in the injury prevention programmes.

Non-contact injury risk factors

In sport, the risk of injury experienced by an athlete is affected by a combination of their intrinsic (ie, athlete dependent) factors and the way in which these interact with the sports environment (extrinsic risk factors),9–11 some of which are modifiable and others which are non-modifiable.11

Intrinsic risk factors

The first 4 of the ‘Top 5’ intrinsic risk factors for non-contact injury, identified by the present survey, are reflective (in the same rank order) of those reported in a previous survey of premier league clubs5 (1st—previous injury, 2nd—fatigue, 3rd—muscle imbalance and 4th—physical fitness). While fatigue (inter-related with physical fitness) and muscle imbalance have been rated of identical importance in both surveys, the current survey has provided new information by revealing accumulated fatigue (as experienced throughout the course of a season or congested match fixtures) and agonist:antagonist muscle imbalance are deemed of particular importance in the national team context. Currently, previous injury as a risk factor in top-level footballers has a strong level of scientific evidence, whereas fatigue has a low level of evidence and muscle imbalance findings are too inconclusive to assign any specific level of evidence.6 Nevertheless, the present findings suggest that future research on national teams should focus efforts on these aforementioned intrinsic risk factors.

Extrinsic risk factors

In line with the perceptions of the physicians in this survey, reduced recovery time (1st) and a congested match schedule (3rd) are supported risk factors for injury in top-level footballers.12 13 Three of the other perceived extrinsic risk factors, namely, training load prior to the World Cup (2nd), training load during the World Cup (joint 3rd place) and the number of matches played during the club season (joint 4th place) can be considered specific to national team concerns and are under the umbrella term of ‘workload’ imposed on the player (ie, physical and mental loads from training and matches). Previous research has shown that 60% of players who played in more than one match per week during the 10 weeks prior to the World Cup 2002 incurred injuries or underperformed during that World Cup.14 Although not currently shown in top-level footballers, workloads from training and matches have been associated with injury in other football codes.15–19 Investigations into the association between workload and injury in top-level football players are, therefore, highly pertinent.

Assessment and monitoring of injury risk

In sport, each athlete has a unique risk value9 and it is important to examine those intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors that interact to make an athlete susceptible to injury, ideally before the injury inciting event occurs.10 Ninety-four per cent of teams at the FIFA 2014 World Cup assessed their players’ individual injury risk profiles with the common tests and monitoring tools outlined below.

The ‘5’ most commonly used injury risk screening tests

The ‘5’ most commonly used screening tests used by national teams were flexibility (dynamic and static), physical fitness, joint mobility, balance/proprioception and evaluation of both muscle endurance and peak strength.

Tests of physical fitness, balance/proprioception and muscle strength are in line with their similarly ranked importance as risk factors outlined earlier. Accordingly, there appears to be a coherent approach of practitioners in terms of implementing screening tests that potentially identify what they consider to be among the most important intrinsic risk factors for their players. In contrast, as risk factors, joint mobility/function and flexibility were ranked as 11th (58/96 points) and 12th (56/96 points) out of 18 ranks, respectively. Despite this lower ranking and conflicting research about these as risk factors for professional footballers,20–23 91% of physicians rated joint mobility/function and flexibility as having at least some importance. The fact that these tests are generally easy to implement may explain why these are among the most widely used by national teams.

The ‘5’ most commonly used monitoring tools

The ‘5’ most commonly used monitoring tools were daily medical screens, tracking of number of matches/minutes played, subjective and objective wellness, heart rate and biochemical markers (biochemical and objective wellness jointly share 5th rank). These monitoring tools are consistent with national team physicians’ perceptions of injury risk factors in that they can provide a range of outcome measures of how the player is ‘coping with the workload’, whether physically (medical screen, heart rate, biochemical and objective markers of physical state) or mentally (subjective scales). Interestingly, recovery of muscle force was monitored in only nine (28%) teams. This may be due to lack of valid, reliable and sensitive monitoring tools that are easy to implement and require little equipment in such logistically demanding settings.

Exercise-based injury prevention strategies

Top five exercises

The key preventative exercises used by national teams were similar to those reported for premier league clubs,5 albeit in a slightly different order of importance. For example, core, balance/proprioception and eccentric exercise also feature in the ‘Top 5’ of national teams’ exercises. At the time of the present survey there is still no direct scientific evidence that core exercises can reduce injury risk in top-level footballers, although evidence from other top-level football codes suggest some preventative capacity.24 25 Similarly, there remains a lack of scientific evidence for balance/proprioception exercise with only a single study in top-level football26 suggesting reduced ankle injury occurrence. Despite some studies suggesting support for eccentric exercise, it too has a weak level of evidence in the scientific literature6 as it cannot be ascertained that the beneficial effects on injury are specifically from the eccentric component.27–29 Interestingly, in the present survey a ‘combination’ of contraction types was rated the third most important exercise type. Using a combination of contraction types is more reflective of the multidimensional approach to injury prevention programmes in the practical setting. However, in top-level football there is only one study to our knowledge that has investigated the effects of such a programme30 and it reports a reduction in muscle injuries. A limiting factor for extrapolating the findings of this aforementioned study to the national team setting is that the programme was conducted over the period of one season. It is not known if a short duration multidimensional programme can significantly reduce injuries during the constrained timetable of a major international football tournament, particularly given the unknown time course required to achieve reductions in injury risk from such programmes. Finally, while flexibility (2nd) is an important exercise for practitioners, two systematic reviews31 32 have shown that there is no conclusive evidence to support stretching to prevent injuries. Both reviews, however, also highlight that there is no sufficient reason to discontinue using flexibility exercises in the training programme.

Efficacy of and challenges to implementing injury prevention strategies

The majority (81%) of teams that suggested their overall preventative strategies were effective in reducing/limiting non-contact injuries also conceded that these could be improved. This finding is encouraging as it demonstrates that there is a belief among practitioners that there is scope for further significant reductions of non-contact injuries in top-level footballers competing in postseason international tournaments. The challenge now is to find the effective methods and strategies to help national teams to achieve this.

Obtaining compliance from the coaching staff was viewed as one of the main challenges rated by physicians to prevent injuries. While 31% of teams reported perfect compliance from their coaches, there appears to remain room for improving compliance and in turn, further reducing/limiting non-contact injuries. Investigations into coach compliance is a relatively new area of research; however, it appears essential that future studies focus efforts on how to maximise coach integration into the injury prevention programme if such strategies are to be optimised. One suggestion has been to ‘capture the attention of coaches’ by transforming medical statistics into a meaningful context for the coaches; for example, give them specific instances of the negative effect of injury on team selection, performance and results.3 It would be interesting, therefore, to determine what ‘details’ are important to coaches and how these can be implemented in practice to improve coaches’ acceptance of individual injury risk recommendations.

Further, nine specific categories pertaining to ‘challenges faced’ (table 4) in preventing injuries were highlighted in addition to the six areas where practitioners suggest further research (table 5) is necessary to provide meaningful solutions in the practical setting. One overwhelmingly consistent response pertained to the need for research on top-level players. This is qualitatively evidenced by one statement that suggested; “as long as clubs (top level) do not provide access to scientific studies, we will remain in this unsatisfactory status”, that is, where there is little information on preventing injuries at the top level.

A limitation to be recognised is the retrospective nature of the present survey (ie, physicians were surveyed 5 months after the World Cup), and it is acknowledged that such a study design could increase the risk of reporting bias. However, this is a supposition as it is known that a well-designed and conducted retrospective study can be an effective method to guide future prospective work;33 for example, to focus on research questions, clarify hypotheses and identify feasibility issues for the prospective study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study has highlighted the most importantly perceived intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors for non-contact injury in the highest level of international players competing at the FIFA 2014 World Cup. The most commonly used tests and monitoring tools have been identified in addition to the five most important exercises that were incorporated into the injury prevention programme. In a first, the perceived effectiveness of and main challenges faced in the practical setting with regard to preventing non-contact injuries in a major international tournament have been revealed.

Future directions

Future research should concentrate on what is important to practitioners for identifying injury risk (eg, significant risk factors, valid and reliable tests) and the effects of preventative strategies. Also of importance is that future research should investigate aspects related to maximising coach compliance. Practitioners operating at the top level are strongly encouraged to share knowledge, experiences and data (eg, player match and training loads, injury information, individual characteristics) with researchers. The present authors, therefore, respectfully suggest these respective challenges: one to the researchers and one to the practitioners in top-level football. To researchers—carefully consider the perceptions and practices that are important to practitioners (eg, as shown in this study) and focus future investigations to provide the appropriate solutions. To practitioners—form collaborative relationships with applied researchers and/or academic institutions to ensure that future research is directly applicable.

What are the new findings?

- We have revealed the most common perceptions and practices of physicians practicing at the FIFA 2014 World Cup regarding:

- Risk factors for non-contact injuries

- Screening tests and monitoring tools used to develop a players’ individual risk profile

- Preventative strategies used

- Challenges to implementation

We have also provided new information to guide researchers and practitioners to collaboratively contribute to the advancement of injury prevention in elite footballers.

How might it impact clinical practice in the near future?

- The information revealed in this survey may allow a more coherent approach for practitioners in:

- Determining risk factors

- Choosing appropriate tests and monitoring tools

- Implementing prevention strategies

- Exercise based

- Psychology based

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the physicians from the 32 national team federations competing at the FIFA 2014 World Cup who took the time to complete and return the survey. In alphabetical order according to country: Dr Boughlali (Algeria), Dr Daniel Martinez (Argentina), Dr Jones (Australia), Dr Van Crombrugge (Belgium), Dr Karabeg (Bosnia-Herzegovina), Dr Picanco and Dr Runco (Brazil), Dr Ngatchou (Cameroon), Dr Carcuro (Chile), Dr Ulloa Castro (Colombia), Dr Ramirez Elizondo (Costa Rica), Dr Serges Dah and Dr Eirale (Ivory Coast), Dr Bahtijarevic (Croatia), Dr Maldonado (Ecuador), Dr Beasley (England), Dr Le Gall (France), Dr Meyer (Germany), Dr Mutawakilu (Ghana), Dr Christopoulos (Greece), Dr Sierra Zeron (Honduras), Dr Parhan (Iran), Dr Gatteschi and Dr Castellacci (Italy), Dr Ikeda (Japan), Dr Jeong (South Korea), Dr Vázquez (Mexico), Dr Goedhart (Netherlands), Dr Gyaran (Nigeria), Dr Jones (Portugal), Dr Bezuglov (Russia), Dr Celada (Spain), Dr Wetzel and Dr Grosse (Switzerland), Dr Pan and Dr Barbosa (Uruguay), and Dr Chiampas (USA). They would also like to extend their gratitude to Abd-elbasset Abaidia and Veronica Menossi for their valuable help in translating the surveys into French and Spanish, respectively. Finally, the authors express their thanks to Kent Fallon for his technical expertise in constructing the figures.

Footnotes

Contributors: AM, MD, GD and CC came up with the initial idea for the survey. AM, MD, GD, RD and CC contributed to the preparation of an initial survey draft. AM, MD, TEA and IB prepared the final survey draft. All authors contributed to and approved the final survey to be sent to the national teams. TEA and IB piloted the survey. AM made the changes recommended following the pilot survey. All authors approved these changes. AM, MD, TEA, IB and JD were responsible for contacting and recruiting national team physicians. All follow up contact made to national team physicians was performed by AM, MD, IB or JD. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and plan for the manuscript. AM completed the first draft of the injury survey and sent it to MD, TEA, IB, MB, RD and JD. The final manuscript to be submitted was prepared by AM, taking into consideration all authors feedback. AM submitted the study.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hägglund M, Walden M, Magnusson H, et al. Injuries affect team performance negatively in professional football: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:738–42. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eirale C, Tol JL, Farooq A, et al. Low injury rate correlates with team success in Qatari professional football. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:807–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ekstrand J. Keeping your top players on the pitch: the key to football medicine at the professional level. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:723–4. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drawer S, and Fuller CW. Propensity for osteoarthritis and lower limb joint pain in retired professional soccer players. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:402–8. 10.1136/bjsm.35.6.402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCall A, Carling C, Nedelec M, et al. Risk factors, testing and preventative strategies for non-contact injuries in professional football: current perceptions and practices of 44 teams from various premier leagues. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1352–7 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCall A, Carling C, Davison M, et al. Injury risk factors, screening tests and preventative strategies: a systematic review of the evidence that underpins the perceptions and practices of 44 football (soccer) teams from various premier leagues. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:584–90. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dvorak J, Junge A, Derman W, et al. Injuries and illnesses of football players during the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:626–30. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.079905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekstrand J, Hägglund M, Kristenson K, et al. Fewer ligament injuries but no preventive effect on muscle injuries and severe injuries: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:732–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuller CW. Managing the risk of injury in sport. Clin J Sports Med 2007;17: 182–7. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e31805930b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meeuwisse WH, Tyerman H, Hagel B, et al. A dynamic model of etiology in sport injury: the recursive nature of risk and causation. Clin J Sports Med 2007;17:215–19. 10.1097/JSM.0b013e3180592a48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahr R, Holme I. Risk factors for sports injuries—a methodological approach. Br J Sports Med 2003;37:384–92. 10.1136/bjsm.37.5.384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bengtsson H, Ekstrand J Hagglund M. Muscle injury rates in professional football increase with fixture congestion: an 11 year follow up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:743–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dupont G, Nedelec M, McCall A, et al. Effect of 2 soccer matches a week on physical performance and injury rate. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:1752–8. 10.1177/0363546510361236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekstrand J, Walden M, Hagglund M. A congested football calendar and the wellbeing of players: a correlation between match exposure of European footballers before the World Cup 2002 and their injuries and performances during that World Cup. Br J Sports Med 2004;38:493–7. 10.1136/bjsm.2003.009134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabbett T, Jenkins DG. Relationship between training load and injury in professional rugby league players. J Sci Med Sport 2011;14:204–9. 10.1016/j.jsams.2010.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabbett TJ. The development and application of an injury prediction model for noncontact, soft-tissue injuries in elite collision sport athletes. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:2593–603. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181f19da4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabbett T, Domrow N. Relationships between training load, injury, and fitness in sub-elite collision sport athletes. J Sports Sci 2007;25:1507–19. 10.1080/02640410701215066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colby M, Dawson B, Heasman J, et al. Accelerometer and GPS derived running loads and injury risk in elite Australian footballers. J Strength Cond Res 2014;28:2244–52. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogalski B, Dawson B, Heasman J, et al. Training and game loads and injury risk in elite Australian footballers. J Sci Med Sport 2013;16:499–503. 10.1016/j.jsams.2012.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fousekis K, Tsepis E, Poulmedis P, et al. Intrinsic risk factors of noncontact quadriceps and hamstring strains in soccer: a prospective study of 100 professional players. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:709–14. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.077560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley PS, Portas MD. The relationship between preseason range of motion and muscle injury in elite soccer players. J Strength Cond Res 2007;21:1155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Witvrouw E, Danneels L, Asselman P, et al. Muscle flexibility as a risk factor for developing muscle injuries in male professional soccer players. A prospective study. AM J Sports Med 2003;31:41–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arnason A, Sigurdsson SB, Gudmundsson A, et al. Risk factors for injuries in football. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:5S–16S. 10.1177/0363546503258912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hides JA, Stanton WR. Can motor control training lower the risk of injury in professional football players? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:762–8. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hides JA, Stanton WR, Mendis MD, et al. Effect of motor control training on muscle size and football games missed from injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:1141–9. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318244a321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammadi F. Comparison of 3 preventative methods to reduce the recurrence of ankle inversion sprains in male soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:922–6. 10.1177/0363546507299259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnason A, Andersen TE, Holme I, et al. Prevention of hamstring strains in elite soccer: an intervention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2008;18:40–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00634.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Croisier JL, Ganteaume S, Binet J, et al. Strength imbalances and prevention of hamstring injury in professional soccer players: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:1469–75. 10.1177/0363546508316764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Askling C, Karlsson J, Thorstensson A. Hamstring injury occurrence in elite soccer players after preseason strength training with eccentric overload. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2003;13:244–50. 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.00312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Owen AL, Wong Del P, Dellal A, et al. Effect of an injury prevention program on muscle injuries in elite professional soccer. J Strength Cond Res 2013;27:3275–85. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318290cb3a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis J. A systematic review of the relationship between stretching and athletic injury prevention. Orthop Nurs 2014;33:312–20. 10.1097/NOR.0000000000000097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thacker SB, Gilchrist J, Stroup DF, et al. The impact of stretching on sports injury risk: a systematic review of the literature. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36:371–8. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000117134.83018.F7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hees DR. Retrospective studies and chart reviews. Respir Care 2004;49:1171–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.