Abstract

The embryonic mammalian metanephric mesenchyme (MM) is a unique tissue because it is competent to generate the nephrons in response to Wnt signaling. An ex vivo culture in which the MM is separated from the ureteric bud (UB), the natural inducer, can be used as a classic tubule induction model for studying nephrogenesis. However, technological restrictions currently prevent using this model to study the molecular genetic details before or during tubule induction. Using nephron segment-specific markers, we now show that tubule induction in the MM ex vivo also leads to the assembly of highly segmented nephrons. This induction capacity was reconstituted when MM tissue was dissociated into a cell suspension and then reaggregated (drMM) in the presence of human recombinant bone morphogenetic protein 7/human recombinant fibroblast growth factor 2 for 24 hours before induction. Growth factor–treated drMM also recovered the capacity for organogenesis when recombined with the UB. Cell tracking and time-lapse imaging of chimeric drMM cultures indicated that the nephron is not derived from a single progenitor cell. Furthermore, viral vector-mediated transduction of green fluorescent protein was much more efficient in dissociated MM cells than in intact mesenchyme, and the nephrogenic competence of transduced drMM progenitor cells was preserved. Moreover, drMM cells transduced with viral vectors mediating Lhx1 knockdown were excluded from the nephric tubules, whereas cells transduced with control vectors were incorporated. In summary, these techniques allow reproducible cellular and molecular examinations of the mechanisms behind nephrogenesis and kidney organogenesis in an ex vivo organ culture/organoid setting.

Keywords: kidney development, nephron segmentation, ex vivo organogenesis, organ, reconstruction, renal primary cells, viral RNAi

The mammalian metanephric kidney develops mainly from the epithelial ureteric bud (UB) cells, and the Six2+ nephron assembling and Foxd1+ stromal mesenchymal precursor cells.1–3 The kidney provides an excellent developmental model organ because the early morphogenetic and cell differentiation steps noted in vivo are recapitulated ex vivo in organ culture conditions.4 Moreover, the metanephric mesenchyme (MM) provides a way to target the mechanisms of nephrogenesis induced by Wnt signaling (for a review, see references 1–3, 5–11).

By around midgestation in the mouse (E10.0), the MM cells have become competent for nephrogenesis.3 The nephrogenic potential of the MM can be maintained even if the MM cells are dissociated and reaggregated.12–14 The caveat of this classic approach is that nephrogenesis has to be induced before the dissociation step to prevent the evident apoptosis.3,15 Dissociation strategies were again recently applied.16–20 However, it is currently still impossible to target the cellular and molecular genetic details before or during the transmission and transduction of the inductive signals.21–24

We show here that the dissociated and reaggregated kidney mesenchyme (drMM) survives and remains competent at least for 24 hours in the presence of human recombinant bone morphogenetic protein 7 (hrBMP7) and human recombinant fibroblast growth factor 2 (hrFGF2), and can assemble segmented nephrons when induced ex vivo. These findings provide a novel efficient method for the viral transduction of competent MM cells. Finally, we show that, unlike the control MM cells, the Lhx1 knockdown cells fail to enter the tubules as in vivo.25–27 Thus, the technology should be applicable for renal gene discovery ex vivo.

Results

Tubule Induction of the Kidney Mesenchyme Progenitor Cells Leads to Assembly of Well Segmented Nephrons Ex Vivo

The value of the ex vivo kidney induction model depends on how well the process recapitulates the in vivo nephrogenesis. We targeted this question by studying to what extent a panel of nephron segment-specific markers24 would become induced ex vivo.

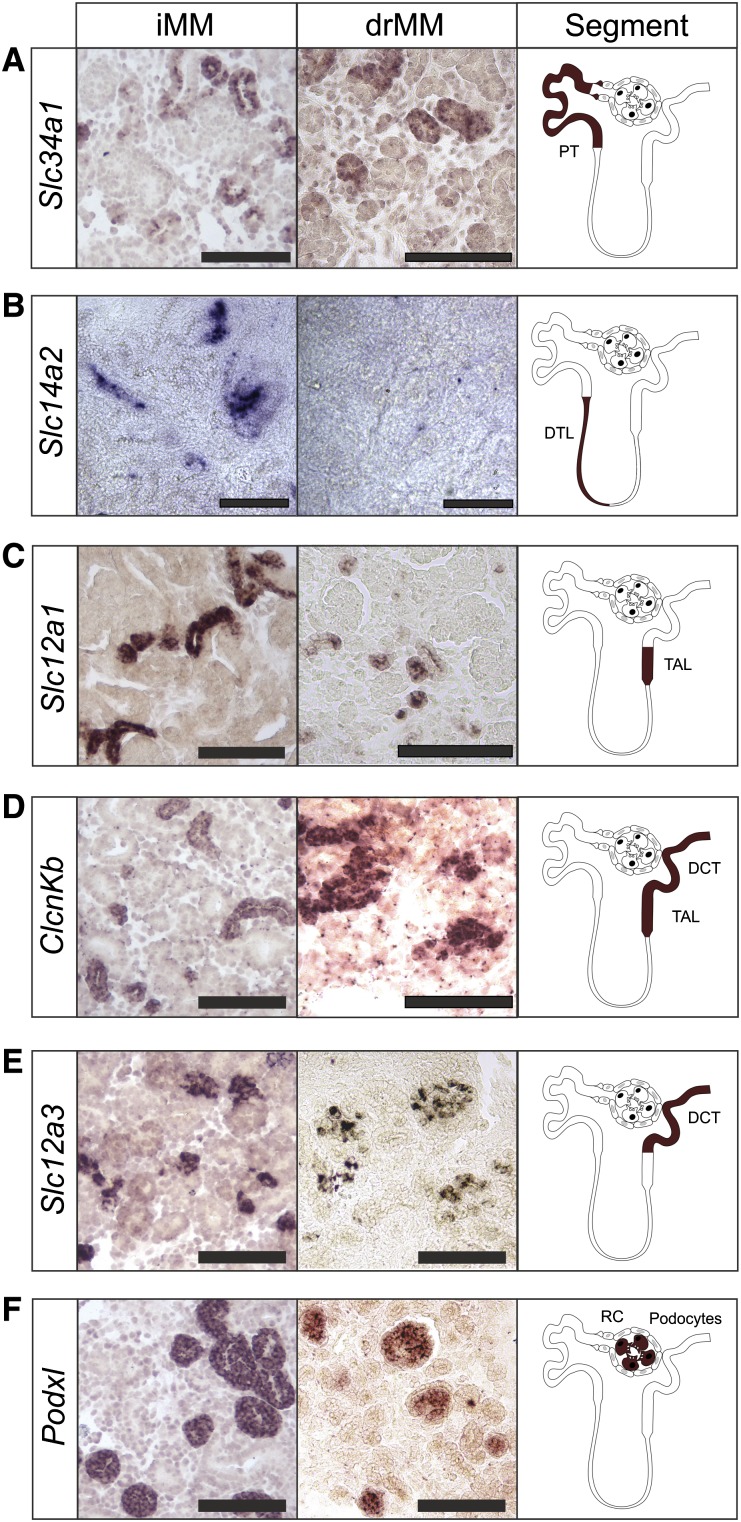

The embryonic metanephric kidney rudiment was dissected at E11.5 and the UB was removed from the MM. The classic transfilter tubule induction model was then set by conjugating an intact kidney mesenchyme (iMM) with the dorsal piece of an E11.5 embryonic spinal cord (eSC) and the conjugate was cultured for 9 days (Figure 1, steps 1 and A4).3 In the explants, Pecam1+ endothelial cells, Pax2+ epithelial tubules resembling proximal and distal tubules, and renal corpuscle structures were formed (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B). The explants expressed also the type II Na/Pi cotransporter NaPi-IIa Slc34a1 for the brush border membrane in the proximal tubule,28 the Slc14a2 for the descending thin limb of Henle’s loop,29 the Na-K-Cl transporter Slc12a1 (nkcc2) for the thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop,30 the voltage-gated chloride channel ClcnKb for the thick ascending limb of Henle’s loop and the distal convoluted tubules,31 the thiazide-sensitive sodium chloride cotransporter Slc12a3 (NCC) for the distal convoluted tubules,32,33 and finally Podxl for the glomerular podocytes in the renal corpuscle34 (Figure 2, iMM). Thus, the induced MM also assembles well segmented nephric tubules ex vivo.

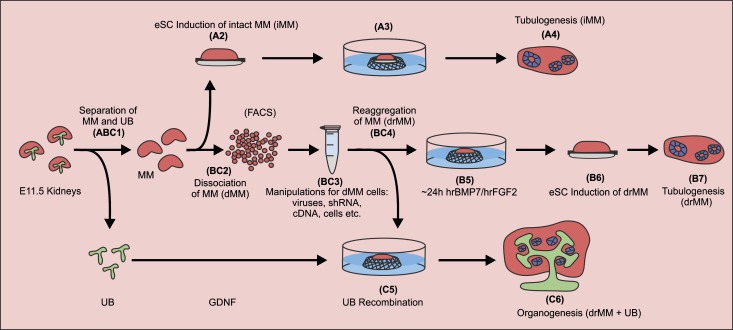

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the experimental systems developed for addressing kidney development in organ culture setting. In all of the experiments, mouse embryonic kidney rudiments were dissected at E11.5 and processed for culture as illustrated in steps 1–7. (Step ABC1) The MM (in red) containing the nephron progenitor cells is mechanically separated from the UB (in green). (Steps A2 and A3) The iMM is placed on a 1.0-µm pore size Nuclepore filter. A piece of eSC is placed under the MM in a transfilter culture setup. (Step BC2) In the other approach, the iMM is dissociated into a suspension of single cells (dMM) via enzyme treatment and mechanical cell separation. At this point, the cells can be FACS sorted. (Step BC3) The cells are manipulated further or mixed with homotypic cells. (Step BC4) These cells are then aggregated by gentle centrifugation and allowed to recover for some time in the presence of the GFs hrBMP7 and hrFGF2. In some of the experiments, the dissociated cells are supplemented with recombinant viruses before reaggregation. (Step B5) The reaggregated and recovered MM is placed on a Nuclepore filter in the presence (or absence of the GFs) and cultured for 24 hours. (Step B6) The GFs are removed and the inducer tissue (eSC, in gray) is placed on the opposite side of the filter. (Step C5) In a third approach, the UB that is separated from the MM is incubated with GDNF and recombined with the drMM. The resulting tissue conjugate is cultured without GFs. (Steps A4, B7, and C6) The explants are cultured for up to 9 days and the degree of tubular nephron formation (in blue) is analyzed from sections by histologic inspection and with specific markers.

Figure 2.

Ex vivo tubule induction in embryonic kidney mesenchymal progenitor cells leads to the formation of a well segmented nephron in intact tissue, and also even after dissociation and reaggregation. RNA in situ hybridization is used to assess the degree of tubulogenesis induction of the eSC in the iMM or drMM. After 8 days of culture, the results indicate that the tubule inductive signaling promotes expression of marker genes Scl34a1+ for proximal tubule (A), Slc14a2+ for descending thin limb of Henle’s loop (B), Slc12a1+ (C) and ClcnKb+ (D) for thick ascending loop of Henle, ClcnKb+ (D) and Slc12a3+ (E) for distal tubule and distal convoluted tubule, and Podxl+ for podocyte in the renal corpuscle (F). It is noteworthy that the nephron segmentation and differentiation potential, except the descending thin limb of Henle’s loop, is restored after the drMM steps, as judged by expression of the segment-specific markers A–F. PT, proximal tubule; DTL, descending thin limb of Henle’s loop; TAL, thick ascending loop of Henle; DCT, distal convoluted tubule; RC, renal corpuscle. Bar, 100 µm.

Competence of Kidney Mesenchyme to Form Segmented Nephrons Is Maintained with BMP7/FGF2 Even after Dissociation and Reaggregation of the Constituent Cells

Although embryonic kidneys can be cultured and the developmental steps are recapitulated, the setup still provides only limited opportunity to study the molecular foundations of nephrogenesis.35 To try to improve the setup, we applied both the classic iMM tubule induction model and a model in which the MM was dissociated and reaggregated12,14 (drMM) (Figure 1, steps BC2–BC4). The caveat of the traditional drMM technology is that the MM degenerates unless tubulogenesis is induced before the MM dissociation step.3,15

The next step was to study the potential of hrBMP7 and hrFGF2 to maintain the nephrogenic competence in the uninduced, dissociated, and reaggregated MM (drMM) (Figure 1, steps 1–B7), because these growth factors (GFs) promote the survival of the intact kidney mesenchyme in vitro15,36 (Figure 1, step A2).

When the uninduced MM was dissociated into a cell suspension, scored by microscopic inspection (Supplemental Figure 1C), reaggregated (drMM), and cultured for 24 hours with hrBMP7/hrFGF2, the MM cell survival was promoted notably (Supplemental Figure 1D). When the drMM was induced, numerous epithelial tubules, endothelial cells, and renal corpuscle-like assemblies appeared as seen by the Pax2 and Pecam1 expression and histology (Supplemental Figure 1, E and F, insert).

The analysis of the stromal, nephron progenitor, and nephron segment-specific markers indicated that the GF-treated drMM can well reconstitute the capacity for nephrogenesis. The induced drMM expressed Six2, Foxd1, Pax2, Nephrin, Aquaporin1, and NCC depicting tubulogenic, interstitial mesenchyme, renal epithelium, podocytes, and proximal and distal tubules, respectively (Supplemental Figure 2), and all of the characterized nephron segment markers but not of loop of Henle Slc14a2 (Figure 2, compare drMM with iMM).

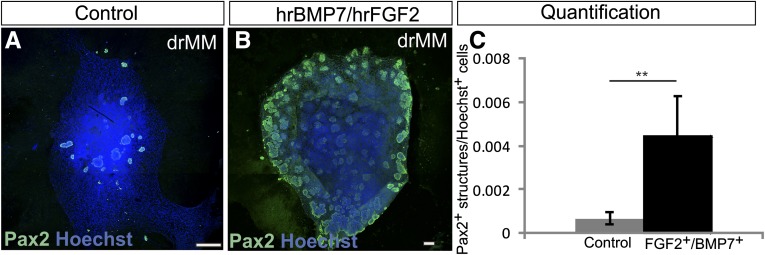

The positive influence of hrBMP7/hrFGF2 GFs was quantified by counting the number of Pax2+ foci in the control explants not treated with these GFs at all before the induction (Figure 3A) and comparing the results with those of the explants cultured with the hrBMP7/hrFGF2 GFs for 24 hours before induction (Figure 3B). Significantly more Pax2+ foci were present in the GF-treated drMMs than in controls. Thus, hrBMP7/hrFGF2 promotes survival and nephrogenesis competence in the drMM as well (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Supplementation of hrFGF2 and hrBMP7 to dissociated and reaggregated embryonic kidney mesenchymal progenitor cells maintains nephrogenesis competence. The embryonic kidneys are prepared and treated as depicted in Figure 1 (steps 1–7). (A) If the nephron progenitor cells containing embryonic kidney mesenchyme are dissociated and reaggregated (drMM) without hrBMP7 and hrFGF2 and induced to differentiate, then only very few tubules appear after culture. (B) However, if the hrBMP7 and hrFGF2 GFs are added to the drMM during generation and maintained during the subsequent 24-hour culture period before the tubule induction step, this leads to the formation of numerous nephrons depicted with the Pax2 immunostaining (in green). (C) Quantification of the positive influence of hrBMP and hrFGF2 to maintain the nephrogenesis competence in the drMM. Counting of the number of induced drMM Pax2+ cells in relation to total number of cells (Hoechst) in the presence or absence of hrBMP7 and hrFGF2 highlights the positive influence of these GFs in the maintenance of the nephrogenesis competence in the drMMs. Hoechst depicted the nuclei (in blue). **P<0.05. Bar, 100 µm.

We then used time-lapse microscopy and bright-field monitoring to study how the drMM precursor cells become reorganized as a result of tubule induction. Close inspection of the movies revealed that cell motility was induced and several translucent cell aggregates formed representing the nephron primordia14,37 (Supplemental Movie 1). To summarize, the presence of hrBMP7/hrFGF2 before tubule induction preserves the competence of drMM for 24 hours and enables robust induction of tubulogenesis.

Generation of Chimeric Kidney Mesenchymal Aggregates Indicate That the Nephron Is Not Formed from a Single Progenitor Cell

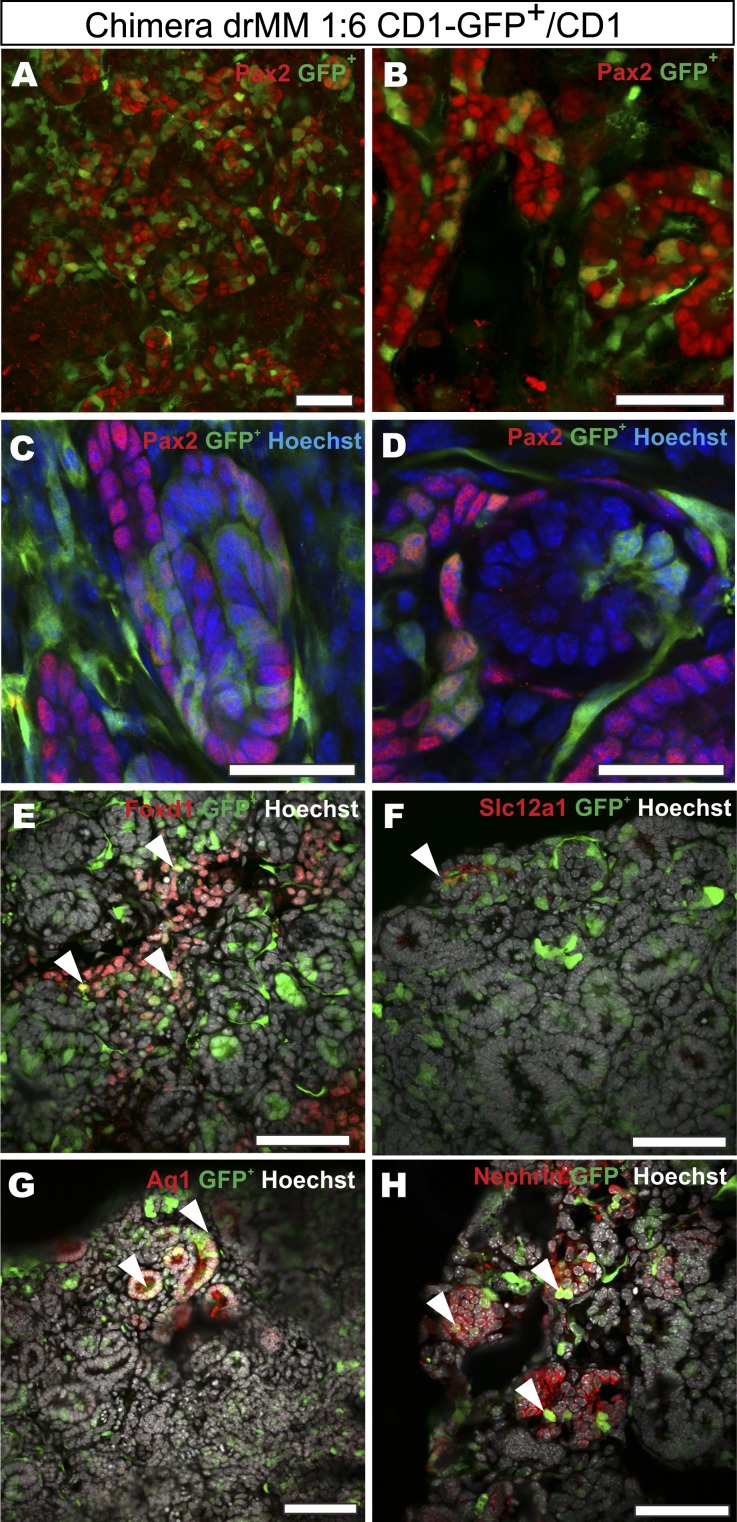

We then examined whether the ex vivo model would enable the construction of chimeric MM composed of green fluorescent protein (GFP+) and normal progenitor cells to study the foundations of nephrogenesis. The MMs were prepared from stage-matched CD-1GFP+38 and wild-type CD-1 mouse embryos, mixed in a 1:6 ratio, reaggregated, and induced with eSC. In the CD-1GFP+ mouse model, the GFP expression is controlled by a constitutively active β-actin/cytomegalovirus promoter.38 Therefore, the setup provides a gene loci-independent system to map cell fates in the kidney.

As expected, the GFP+ MM cells within the cultured chimeric explants had the capacity to incorporate to the epithelial tubules (Figure 4, A–D) and among the Foxd1+ (stromal cells), Aquaporine1+ (AQ1, proximal tubules), Slc12a1+ (distal tubules), and Nephrin+ (podocytes) cells (Figure 4, E–H). It is noteworthy that we failed to find nephrons composed exclusively of the GFP+ cells (Figure 4). This suggests a nonclonal cellular origin of the renal vesicles. Counting of the GFP+/GFP− cell ratios in the chimeric MM indicated that the original 1:6 ratio was maintained during the MM culture (Figure 4, A–D). Inspection of the video records of such MMs demonstrated the highly migratory nature of the GFP+ MM cells during the repatterning process (Supplemental Movie 2). It appears that the chimeric MM serves as a faithful approach to examine the details of renal cell-fate control mechanisms. The results also show that the nephron is not formed from a single precursor cell, which is in accordance with the data in vivo.39

Figure 4.

Chimeric reaggregated embryonic kidney mesenchymal progenitor cell cultures indicate that a single nephron does not originate from a single cell. A MM is microsurgically prepared from the kidney primordia of constitutively GFP-expressing mouse embryos at E11.5 (in green), dissociated, and mixed in a 1:6 ratio with nonlabeled, wild-type MM cells. These chimeras are reaggregated and induced with eSC, cultured as illustrated in Figure 1, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. (A and B) The chimeric explants reveal a wealth of GFP+ cells within the cell aggregates that have undergone mesenchyme to epithelium transition and are expressing Pax2 (in red), a tubulogenesis marker. (C and D) Higher magnifications of A and B are shown and depict the presence of GFP+ cells also within tubules (C, in green) and as ingrowth of cells in a renal corpuscle-like structure (D, in green). (E–H) The micrographs also highlight the specific renal cell types and indicate that the GFP+ MM-derived renal progenitors have generated (arrowheads) Foxd1+ stromal cells (E), Slc12a1+ distal tubuli (F), Aquaporin 1+ proximal tubuli (G), and Nephrin+ podocyte cells (H) as depicted with specific antibody-mediated staining. The Hoechst staining (in blue or gray) highlights the nuclei of the cells. Bar, 50 µm.

Foxd1+ Stromal Progenitor Cells in Kidney Mesenchyme Are Critical for the Expansion of Primitive Vasculature and the Advancement of Nephrogenesis

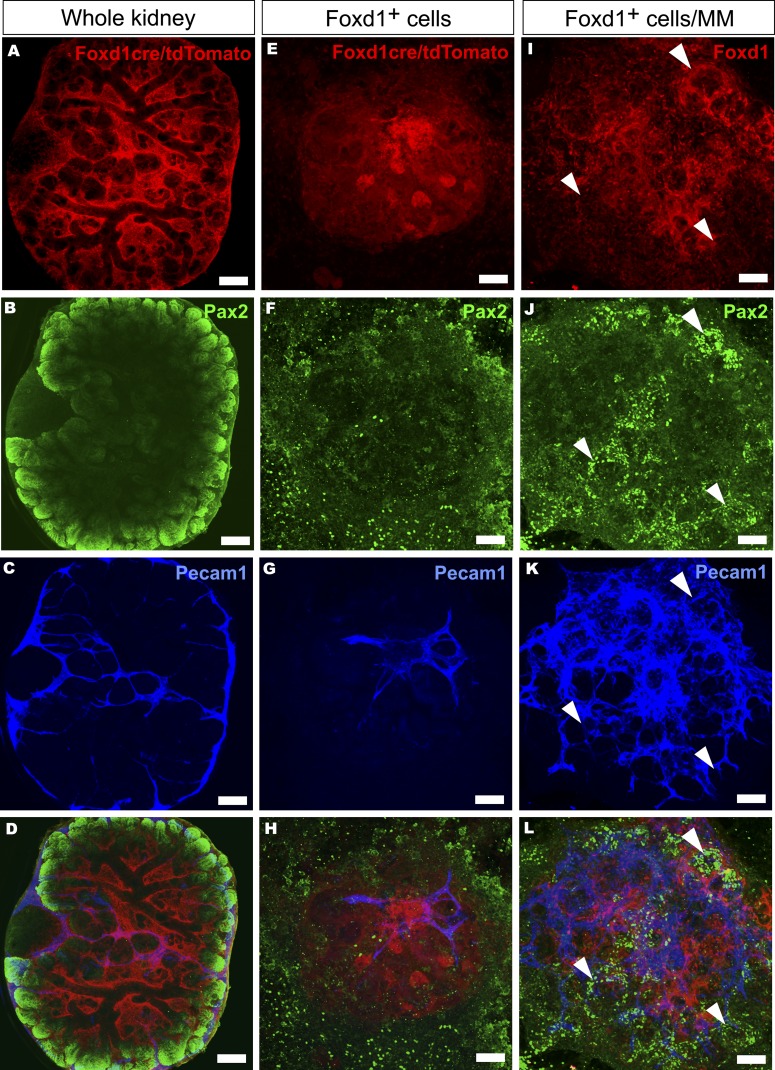

The capacity to dissociate and reaggregate the MM and still obtain well segmented nephrons was considered as a technology also allowing the extraction of specific cells from the MM. We tested this possibility for the Foxd1+ stromal progenitor cell with the aid of the Foxd1cre+; floxed Rosa26tdTomato+ mice40,41 and FACS. In the organ culture condition, the Foxd1+ cells also remain distinct from the Pax2+ ones representing the nephron precursors (Figure 5, A–D).

Figure 5.

Interaction of Foxd1+-derived stromal cells with embryonic kidney mesenchymal progenitor cells is critical for endothelial network and nephron development. (A–D) The fate of the Foxd1cre+/floxed Rosa26tdTomato-marked stromal progenitor cells (in red), the kidney tubular cells (in green, Pax2+), and endothelial cells (in blue, Pecam1+) is mapped in whole-kidney time-lapse organ culture in the embryonic kidney mesenchyme (MM). (E–L) Alternatively, the stromal cell behavior is addressed in FACS-purified, homotypic Foxd1+ cells aggregates (E–H) or when the extracted Foxd1+ cells were recombined with the rest of the embryonic kidney MM cells (I–L). The Foxd1cre-marked tdTomato+ cells (in red) are found around the nonstained ureteric tree (A and D) and the developing nephrons are depicted with Pax2 staining (B and D, in green), resembling the situation in vivo. The endothelial cells establish a network within and around the kidney as highlighted by Pecam1 expression (C, in blue). (E–H) The FACS-purified dMM-derived Foxd1cre-marked tdTomato+ cells are aggregated for homotypic cultures and subjected to the eSC tubule inducer. In such a setting, the FoxD1+ cell aggregates survive (E) but no tubules appear, as illustrated by the failure in epithelial tubular organization and weak Pax2 expression (F, in green). Endothelial Pecam1 expression (G, in blue) is also limited in these cells. (J and K) The presence of the Foxd1+ cells (in red) with the rest of the MM cells promoted both Pax2 expression (J, in green; arrowheads) and differentiation of the Pecam1+ endothelial network (K, in blue). Culture time is 5 days. Bar, 200 µm.

The FACS separated Foxd1+ cells were cultured either as homotypic cell aggregates or together with the rest of the MM cells in the presence of hrBMP7/hrFGF2 for 24 hours. After this period, these factors were removed and the explants were induced with the eSC. In the first mentioned conditions, the Foxd1+ cells survived, but the Pax2 and Pecam1 marker expressions remained weak (Figure 5, E–H). When these cells were conjugated with the rest of the MM cells and processed as above, a robust expression of these markers was noted (Figure 5, I–L). The data indicate that the developed setups provide new ways to study the roles of specific progenitor cell types, their interactions, and expressed factors during nephrogenesis.

The Capacity for Kidney Development Can Be Reconstituted by Combining Reaggregated and Induced Kidney Mesenchymal Cells with the UB

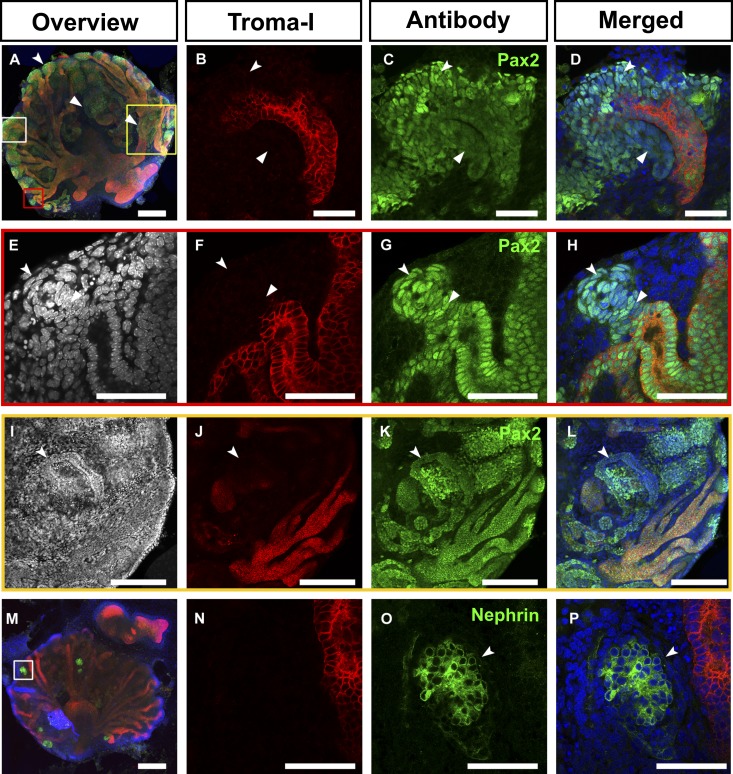

Given the capacity of the induced drMM to reconstitute nephron segmentation, we decided to study whether the reciprocal and sequential tissue interactions with the UB would be recovered in the conjugates as well. Freshly separated UB was exposed to Glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) before MM recombination42 (Figure 1, step C5) and the explants were cultured for 9 days to evaluate the potential for kidney organogenesis.

Interestingly, the drMM, combined with the GDNF-treated UB, recovered kidney organogenesis based on the degree of formed UB branches (Figure 6, A and B). The UB also recovered the potential for tubule induction because early nephron marker Pax2-expressing MM cells around the UB tips were present (Figure 6, C–H, in green). Pax2+ renal vesicle-like structures and some UB connecting tubules had formed as well43 (Figure 6, E–H, arrowheads). A juxtamedullary-like region expressed also Pax2 (Figure 6, I–L) and the renal corpuscle-like structures expressed the podocyte marker Nephrin (Figure 6, M–P). Thus, the induced drMM recovers the reciprocal signaling with the UB to some extent, suggesting that the setup allows targeting of the UB molecular biology as well.

Figure 6.

Transiently GDNF-stimulated separated UB recombined with dissociated and reaggregated embryonic kidney mesenchymal progenitor cells reconstitutes the organogenesis. The embryonic kidney is prepared at E11.5 and the UB and kidney mesenchyme (MM) are separated from each other (Figure 1, step 1). The MM is further dissociated (Figure 1, step B2) and then reaggregated (drMM) with freshly dissected, transiently GDNF-dipped UB for culture (Figure 1, steps C4–6). (A–D) The developing UB (in red) has induced nephrogenesis, illustrated by Pax2 expression in the MM (in green, arrowheads). B–D are high magnifications of the white box in A. (E–H) High-magnification micrographs of the red boxed region of A. One representative tubule (concave arrowhead) being in a process of fusion with the UB in the ex vivo setting (arrowheads), similarly to how it occurs in vivo.43 (I–L) High-magnification micrographs of the yellow boxed region of A depicting epithelialized and elongated Pax2+/Troma-1− tubules (in green) formed from the cap mesenchyme (concave arrowheads). (M–P) Recombination of the UB to the drMM has led to UB branching (M, in red) and induction of Nephrin+ renal corpuscle-like structures (insert in M) depicted in higher magnification in O and P (in green, concave arrowheads). The nuclei are depicted in blue. Bar, 200 µm in A, I–M; 50 µm in B–H and N–P.

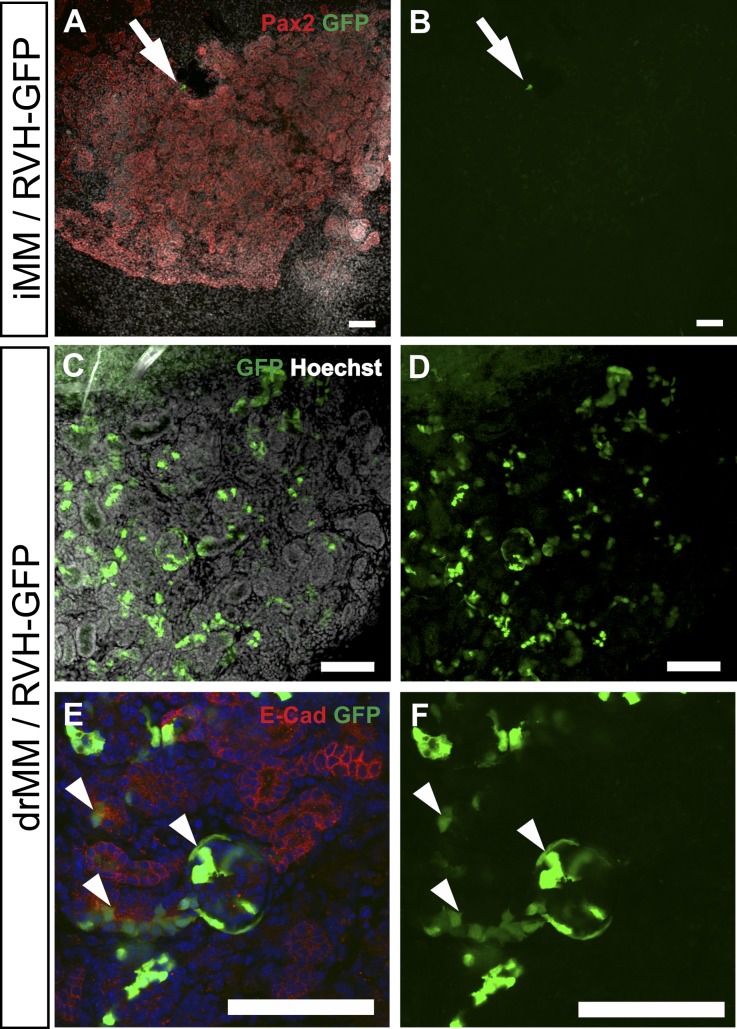

Dissociated Kidney Mesenchymal Cells Can Be Transduced Efficiently, and Such Cells Remain Competent for Nephrogenesis Enabling Targeting of the Regulatory Genes

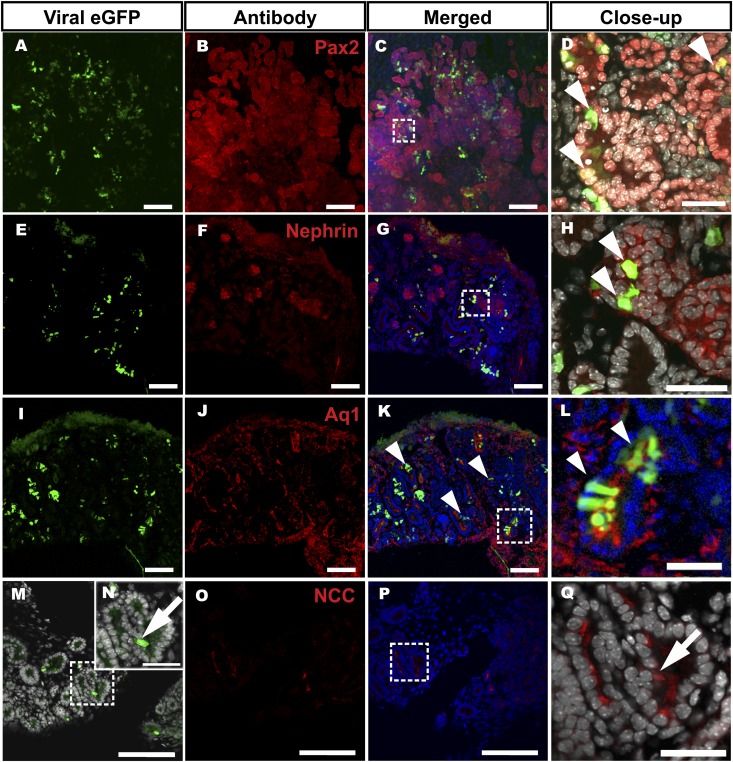

The recombinant viruses are useful to target molecular mechanisms in cell culture models, but they are less useful to study organogenesis due to their poor penetration into tissues.35 Consistent with the above, the GFP+ retro viruses transduced only few superficial cells in the iMM as can be seen from the GFP expression (Figure 7, A and B). However, when the dissociated MM cells were transduced with the GFP+ retroviruses (Figure 1, step BC3) instead, this lead to GFP expression showing efficient transduction (Figure 7, C–F). Staining of the explants with a panel of nephron segment markers showed that the GFP+ cells still differentiated into Pax2+ (Figures 8, A–D, and 9A), Nephrin+ (Figure 8, E–H), AQ1+ (Figure 8, I–L), and NCC+ (Figure 8, M–Q) cells. We conclude that the retrovirus-transduced drMM progenitor cells remain competent to differentiate into the distinct nephron segments and renal corpuscle-like structures.

Figure 7.

Dissociation of embryonic kidney mesenchymal progenitor cells enables their efficient viral transduction so that they are still competent for nephrogenesis when reaggregated and induced. The microdissected and UB separated iMM (A and B) or drMM (C–F) are transduced with GFP cDNA-containing recombinant retroviruses (in green). The cells are then reaggregated, induced to undergo tubulogenesis, and cultured as illustrated in Figure 1 (steps 1–B7). (A and B) A micrograph of a confocal fluorescent section of an iMM that is poorly transduced with the GFP+ virus (arrows). Only few superficial cells have become infected. (C and D) However, infection of the dissociated MMs with the GFP+ virus leads to marked transduction of the drMM cells. Note that the cells inside the drMM explant also express GFP. The ex vivo infection of the iMM with the GFP virus results in poor transduction, but the drMM considerably enhances the transduction efficiency. (E and F) The most important feature is that the viral transduction still allows mesenchyme to epithelium transition of the nephron progenitors, which allows the nephron assembly process to take place as can be seen from the expression of E-cadherin in the epithelial tubules and the presence of GFP in such cells (compare red color with green, see also Figure 8). Note that GFP is expressed in the renal corpuscle-like structure as well (arrowhead on the right). Bar, 100 µm.

Figure 8.

Viral transduction of embryonic kidney mesenchymal progenitor cells does not disturb their competence to assemble a well segmented nephron. The MM is separated and dissociated into a single cell suspension. The cells are transduced with the GFP+ virus (in green). The experimental steps are illustrated in Figure 1 (steps 1–B7). Confocal microscopic inspection of explants shows that the transduced drMM cells expressing the virus-derived GFP have maintained their capacity to differentiate into different nephron segments: the Pax2+ tubular epithelial structures (A–D), Nephrin+ podocytes (E–H), Aquaporin1+ proximal tubule structures (I–L), and NCC+ distal tubule structures (all in red) (M–R). (C, G, K, and P) Merged images simultaneously revealing the GFP, nephron marker expression, and nuclei (Hoechst, in blue). (M and O) The boxed areas depict high-power micrographs in D, H, L, N, and Q. It is of importance that the GFP virus-transduced cells are double positive for the nephron differentiation markers (D, H, and L, arrowheads). (Q and N) Two serial sections depicting the NCC+ cells (Q) and GFP+ (N) (compare Q with N, arrows). Bar, 100 µm; insert, 30 µm.

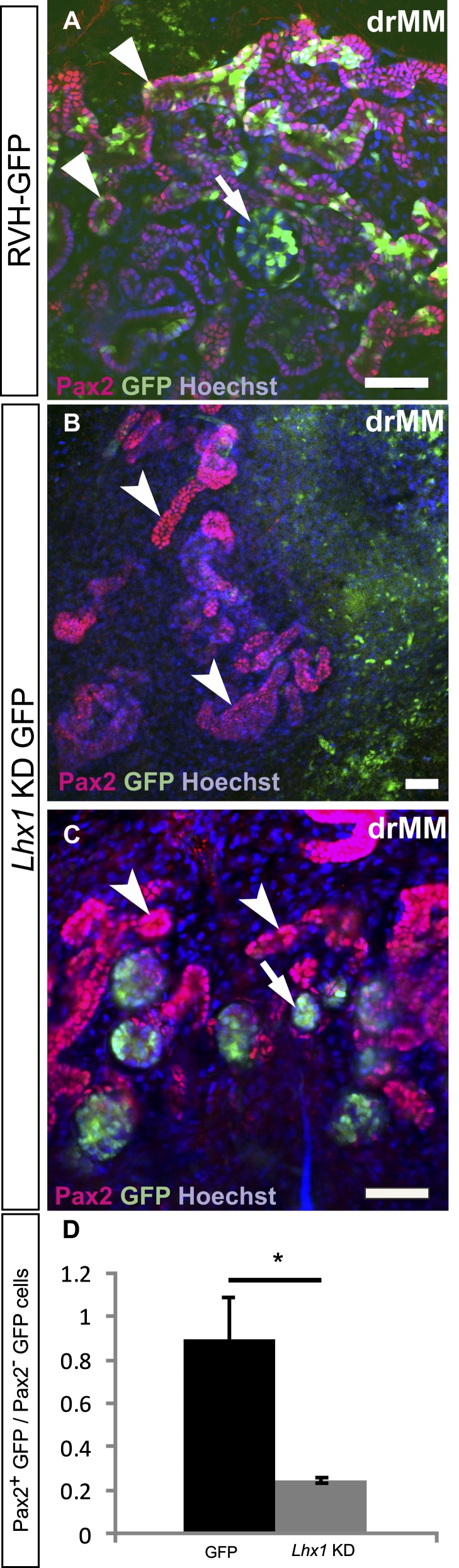

Figure 9.

Virus-mediated knockdown of critical nephrogenesis control gene Lhx1 in embryonic kidney mesenchymal progenitor cells perturbs their integration into nephrons. The dissociation and reaggregation of embryonic kidney mesenchyme (drMM) is conducted as illustrated in Figure 1 (steps 1–B7). The drMM cells are transduced with GFP encoding retroviruses (RVH-GFP), serving as the control, or GFPLhx1shRNA sequences and cultured. The knockdown efficiency of the viral shRNA sequence is estimated at 69%±8.2% in embryonic kidney-derived mK4 cells. (A) Transduction of the drMM with GFP+ control virus and subsequent induction and culture leads to the formation of Pax2+ epithelial tubules with integrated GFP+ cells. (B and C) When the drMM is transduced with the GFP-Lhx1KD sequences containing viruses, the GFP+ Lhx1KD cells are excluded from the MM-derived Pax2+ epithelial tubules (in red, concave arrowheads). The GFP+ cells remain competent to contribute the renal corpuscle-like structures with Bowman’s-like space (arrow). (D) The ratio between the cells expressing the GFP+ either in the Pax2+ or negative tubular cells (GFP+Pax2+/GFP+Pax2−) between control and knockdown drMM is counted. This suggests a statistically significant (*P<0.10) limitation in contribution of Lhx1KD cells into Pax2+ nephric structures. The Hoechst depicts nuclei. Bar, 50 µm.

The next question in our assessment of the ex vivo model is whether it can be used to target the functions of nephrogenesis control genes. To address this question, we selected Lhx1 as a proof-of-principle gene because the Lhx1-deficient nephron progenitor cells initiate differentiation but degenerate later.25,27,44,45 The dissociated MM cells were transduced with the GFP-Lhx1-shRNA (GFP-Lhx1KD) viruses, which silenced Lhx1 expression by 69%±8.2% from control values in model cells. These viruses were introduced to the dMM cells in the presence of hrBMP7/hrFGF2. The MM cells were reaggregated and cultured for 24 hours, after which tubulogenesis was induced as described above (Figure 1, steps 3–B7).

In line with earlier in vivo findings25,26 and compared to the control GFP+ virus infected (Figures 8 and 9A), the GFP-Lhx1KD virus-infected and reaggregated GFP-positive Lhx1-KD cells failed to integrate into the epithelialized nephrons composed mainly from GFP-negative cells (Figure 9, compare B and C with A). Although the nephron tubular development was devoid of the GFP-Lhx1KD+ cells, some GFP+ cells were sufficient to incorporate the renal corpuscle-like structures (Supplemental Figure 3) in line with in vivo25–27 data. The nephron progenitors transduced with the GFP+ retrovirus remain competent for nephrogenesis, but shRNA-mediated silencing of a critical gene can compromise this. The virus vector-based shRNA or cDNA approaches should provide novel opportunities to explore the functions of candidate nephrogenesis control genes in the MM progenitor cells of the reconstituted embryonic kidney ex vivo.

Discussion

Although the kidney MM can be subjected to ex vivo culture and the nephrogenesis inducer was identified to be a Wnt signal triggering signal transduction, the functions of the regulatory genes behind the induced nephrogenesis cannot yet be examined in detail comparable to the embryonic stem cells when generating in vivo renal disease models. To develop the ex vivo and organoid models for functional studies, we took advantage of the classic approach in which the MM is dissociated into progenitor cell suspension and reaggregated afterward.12,14,46 A significant limitation of this approach is that the nephrogenesis has to be induced before the dissociation step of the MM to prevent concurrent apoptosis of the uninduced MM cells.15 The kidney dissociation approach was also recently applied by others16–20 but with respect to the MM, the means to conduct critical gene function studies before or during the tubule induction process17,19 are lacking. A further problem is the impossibility of targeting gene functions in the ex vivo setups, so that long-term cultures and inducible functional studies would be possible.

The results show that mammalian kidney MM progenitor cells can be maintained uninduced for an extended period of time without evident cell apoptosis. Of particular importance is the experimental evidence that the MM cells can be transduced efficiently upon dissociation. The infected cells also remain competent for nephrogenesis. We showed with markers and histology that the integrated provirus and the associated viral promoter-directed GFP expression do not disturb the nephrogenesis, which is critical for the applicability of the adopted ex vivo technology.

To our knowledge, the presented dissociation and reaggregation technique is the first technique that allows the manipulation of MM cells before the activation of the nephrogenesis program. In the current setup, the viruses are provided 24 hours to be inserted as a provirus in the MM cells and begin to express the respective genes, in this case GFP and shRNA, before the nephrogenic induction. The developed renal tissue engineering provides at least the following capabilities: (1) the efficient cellular manipulation of the drMM by BMP7/FGF2, which promotes the survival of uninduced drMM; (2) an examination of the molecular nature of nephrogenesis competence; (3) the creation of chimeric MMs by applying FACS-purified and genetically modified MM cells; (4) a lag period, which enables the genome integration of a transduced gene; and (5) a detailed study of the early molecular events before and during tubule induction.

Another useful approach is the Cre virus-mediated recombination for conditional gain and loss-of-function studies of early but also later stages of nephrogenesis in the ex vivo model. In addition, it should be highlighted that with the provided means, the gene functions can be addressed practically in any specific MM cell type and also in the presence or absence of UB influence. We conclude that the improvement in primary tissue viral transduction in combination with the novel tissue engineering technologies provide diverse opportunities to design the conditional, transient, or more permanent cellular and genetic manipulation of MM cells.

Concise Methods

Dissociation of the MM, Its Reaggregation, and Recombination with the UB

The metanephric kidneys (E11.5) were prepared from wild-type CD-1 mice, CD-1GFP+ mice38 (a gift from Andras Nagy), or Foxd1cre mice bred with GT Rosa CAG reporter mice (tdTomato).47 The MMs were separated and dissociated with Collagenase III (Worthington), reaggregated by centrifugation in the presence of 50 ng/ml of hrBMP7 (Insight Biotechnology) and 100 ng/ml of hrFGF2 (PeproTech), and cultured for 24 hours in the same medium. The MM was induced with a small piece of eSC in a transfilter setup and subcultured for up to 9 days without hrBMP7 or hrFGF2.

For embryonic kidney reconstitution, UBs treated with hrGDNF (PeproTech) were aggregated with the MM pellet and cultured for 4–8 days. For details, see the Supplemental Materials and Methods. Tens of separate dissociation and reaggregation explants were performed, and a minimum of three explants per experiment were assembled for each assay type.

Flow Sorting

The Foxd1+ cells from E11.5 embryos were purified according to cre-activated floxed tdTomato by FACS as previously described.47

Time-Lapse Microscopy

Time-lapse images were captured at 20-minute intervals in a microscope stage incubator (OkoLab) by means of the TControl Basic 2.3 program coupled to an Olympus IX81 inverted microscope with an Olympus XM10 digital camera and the Cell^P software.

Cloning of shRNA Constructs, Virus Production, and Infection of MM Cells

The Lhx1shRNA constructs were inserted into a BglII/XhoI-digested pRVH1-GFP retroviral vector as previously described.48 The function of the shRNA sequences was validated in mK4 cells49 using quantitative PCR. The shRNAs, oligos, and the quantitative PCR are described in detail in the Supplemental Materials and Methods. A human Phoenix gag-pol packaging cell line (http://www.stanford.edu/group/nolan/retroviral_systems/phx.html; American Type Culture Collection, CA) was used to produce the retroviruses, which were introduced into the dMM cells before their reaggregation (see the Supplemental Materials and Methods).

Immunohistochemistry, RNA In Situ Hybridization, and Histologic Staining

The in situ hybridization was performed essentially as previously described.50 The histology, staining, antibodies, and RNA probes are described in the Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Paula Haipus, Hannele Härkman, Johanna Kekolahti-Liias, Jaana Kujala, Kaisa Pulkkinen, and Jaana Träskelin (BCO Virus Core Laboratory) for technical assistance; Ilkka Pietilä for the graphical illustrations; Timo Pikkarainen for comments; Andras Nagy for the GFP+ transgenic mice; Shinji and Ritsuko Takada for the nephron segment probes; and Karl Tryggvason for the Nephrin antibody. The mouse anti-Troma-1 mAb developed by Philippe Brulet and Rolf Kemler was obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and maintained by the University of Iowa Department of Biology.

This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (Grants 206056, 250900, and FiDiPro 263246, and 2012–2017 Centre of Excellence Grant 251314), the Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (to S.J.V.), the European Commission (FP7/2007-2013 FP7-HEALTH-F5-2012-INNOVATION-1 EURenOmics 305608 to A.W.B. and S.J.V.), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK096996 to S.S.-L.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013060584/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dressler GR: The cellular basis of kidney development. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22: 509–529, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vainio S, Lin Y: Coordinating early kidney development: Lessons from gene targeting. Nat Rev Genet 3: 533–543, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saxén L: Organogenesis of the Kidney, Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekblom P, Miettinen A, Virtanen I, Wahlström T, Dawnay A, Saxén L: In vitro segregation of the metanephric nephron. Dev Biol 84: 88–95, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roelink H, Nusse R: Expression of two members of the Wnt family during mouse development—restricted temporal and spatial patterns in the developing neural tube. Genes Dev 5: 381–388, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parr BA, Shea MJ, Vassileva G, McMahon AP: Mouse Wnt genes exhibit discrete domains of expression in the early embryonic CNS and limb buds. Development 119: 247–261, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzlinger D, Qiao J, Cohen D, Ramakrishna N, Brown AM: Induction of kidney epithelial morphogenesis by cells expressing Wnt-1. Dev Biol 166: 815–818, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kispert A, Vainio S, Shen L, Rowitch DH, McMahon AP: Proteoglycans are required for maintenance of Wnt-11 expression in the ureter tips. Development 122: 3627–3637, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kispert A, Vainio S, McMahon AP: Wnt-4 is a mesenchymal signal for epithelial transformation of metanephric mesenchyme in the developing kidney. Development 125: 4225–4234, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itäranta P, Lin Y, Peräsaari J, Roël G, Destrée O, Vainio S: Wnt-6 is expressed in the ureter bud and induces kidney tubule development in vitro. Genesis 32: 259–268, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll TJ, Park JS, Hayashi S, Majumdar A, McMahon AP: Wnt9b plays a central role in the regulation of mesenchymal to epithelial transitions underlying organogenesis of the mammalian urogenital system. Dev Cell 9: 283–292, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auerbach R, Grobstein C: Inductive interaction of embryonic tissues after dissociation and reaggregation. Exp Cell Res 15: 384–397, 1958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grobstein C: Tissue disaggregation in relation to determination and stability of cell type. Ann N Y Acad Sci 60: 1095–1107, 1955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vainio S, Jalkanen M, Bernfield M, Saxén L: Transient expression of syndecan in mesenchymal cell aggregates of the embryonic kidney. Dev Biol 152: 221–232, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koseki C, Herzlinger D, al-Awqati Q: Apoptosis in metanephric development. J Cell Biol 119: 1327–1333, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joraku A, Stern KA, Atala A, Yoo JJ: In vitro generation of three-dimensional renal structures. Methods 47: 129–133, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unbekandt M, Davies JA: Dissociation of embryonic kidneys followed by reaggregation allows the formation of renal tissues. Kidney Int 77: 407–416, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosines E, Johkura K, Zhang X, Schmidt HJ, Decambre M, Bush KT, Nigam SK: Constructing kidney-like tissues from cells based on programs for organ development: Toward a method of in vitro tissue engineering of the kidney. Tissue Eng Part A 16: 2441–2455, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ganeva V, Unbekandt M, Davies JA: An improved kidney dissociation and reaggregation culture system results in nephrons arranged organotypically around a single collecting duct system. Organogenesis 7: 83–87, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ranghini E, Fuente Mora C, Edgar D, Kenny SE, Murray P, Wilm B: Stem cells derived from neonatal mouse kidney generate functional proximal tubule-like cells and integrate into developing nephrons in vitro. PLoS ONE 8: e62953, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dressler GR: Genetic control of kidney development. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp 26: 1–17, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stuart RO, Bush KT, Nigam SK: Changes in gene expression patterns in the ureteric bud and metanephric mesenchyme in models of kidney development. Kidney Int 64: 1997–2008, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwab K, Patterson LT, Aronow BJ, Luckas R, Liang HC, Potter SS: A catalogue of gene expression in the developing kidney. Kidney Int 64: 1588–1604, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raciti D, Reggiani L, Geffers L, Jiang Q, Bacchion F, Subrizi AE, Clements D, Tindal C, Davidson DR, Kaissling B, Brändli AW: Organization of the pronephric kidney revealed by large-scale gene expression mapping. Genome Biol 9: R84, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi A, Kwan KM, Carroll TJ, McMahon AP, Mendelsohn CL, Behringer RR: Distinct and sequential tissue-specific activities of the LIM-class homeobox gene Lim1 for tubular morphogenesis during kidney development. Development 132: 2809–2823, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakai S, Sugitani Y, Sato H, Ito S, Miura Y, Ogawa M, Nishi M, Jishage K, Minowa O, Noda T: Crucial roles of Brn1 in distal tubule formation and function in mouse kidney. Development 130: 4751–4759, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopan R, Cheng HT, Surendran K: Molecular insights into segmentation along the proximal-distal axis of the nephron. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2014–2020, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magagnin S, Werner A, Markovich D, Sorribas V, Stange G, Biber J, Murer H: Expression cloning of human and rat renal cortex Na/Pi cotransport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90: 5979–5983, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olivès B, Martial S, Mattei MG, Matassi G, Rousselet G, Ripoche P, Cartron JP, Bailly P: Molecular characterization of a new urea transporter in the human kidney. FEBS Lett 386: 156–160, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan MR, Plotkin MD, Lee WS, Xu ZC, Lytton J, Hebert SC: Apical localization of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter, rBSC1, on rat thick ascending limbs. Kidney Int 49: 40–47, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kobayashi K, Uchida S, Mizutani S, Sasaki S, Marumo F: Intrarenal and cellular localization of CLC-K2 protein in the mouse kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1327–1334, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loffing J, Loffing-Cueni D, Valderrabano V, Kläusli L, Hebert SC, Rossier BC, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ, Kaissling B: Distribution of transcellular calcium and sodium transport pathways along mouse distal nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F1021–F1027, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Câmpean V, Kricke J, Ellison D, Luft FC, Bachmann S: Localization of thiazide-sensitive Na(+)-Cl(-) cotransport and associated gene products in mouse DCT. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F1028–F1035, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kerjaschki D, Sharkey DJ, Farquhar MG: Identification and characterization of podocalyxin—the major sialoprotein of the renal glomerular epithelial cell. J Cell Biol 98: 1591–1596, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee WC, Berry R, Hohenstein P, Davies J: siRNA as a tool for investigating organogenesis: The pitfalls and the promises. Organogenesis 4: 176–181, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dudley AT, Godin RE, Robertson EJ: Interaction between FGF and BMP signaling pathways regulates development of metanephric mesenchyme. Genes Dev 13: 1601–1613, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vainio S, Lehtonen E, Jalkanen M, Bernfield M, Saxén L: Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions regulate the stage-specific expression of a cell surface proteoglycan, syndecan, in the developing kidney. Dev Biol 134: 382–391, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hadjantonakis AK, Gertsenstein M, Ikawa M, Okabe M, Nagy A: Generating green fluorescent mice by germline transmission of green fluorescent ES cells. Mech Dev 76: 79–90, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mugford JW, Sipilä P, McMahon JA, McMahon AP: Osr1 expression demarcates a multi-potent population of intermediate mesoderm that undergoes progressive restriction to an Osr1-dependent nephron progenitor compartment within the mammalian kidney. Dev Biol 324: 88–98, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hyink DP, Tucker DC, St John PL, Leardkamolkarn V, Accavitti MA, Abrass CK, Abrahamson DR: Endogenous origin of glomerular endothelial and mesangial cells in grafts of embryonic kidneys. Am J Physiol 270: F886–F899, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sequeira Lopez ML, Pentz ES, Robert B, Abrahamson DR, Gomez RA: Embryonic origin and lineage of juxtaglomerular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 281: F345–F356, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin Y, Zhang S, Rehn M, Itäranta P, Tuukkanen J, Heljäsvaara R, Peltoketo H, Pihlajaniemi T, Vainio S: Induced repatterning of type XVIII collagen expression in ureter bud from kidney to lung type: Association with sonic hedgehog and ectopic surfactant protein C. Development 128: 1573–1585, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Georgas K, Rumballe B, Valerius MT, Chiu HS, Thiagarajan RD, Lesieur E, Aronow BJ, Brunskill EW, Combes AN, Tang D, Taylor D, Grimmond SM, Potter SS, McMahon AP, Little MH: Analysis of early nephron patterning reveals a role for distal RV proliferation in fusion to the ureteric tip via a cap mesenchyme-derived connecting segment. Dev Biol 332: 273–286, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shawlot W, Behringer RR: Requirement for Lim1 in head-organizer function. Nature 374: 425–430, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsang TE, Shawlot W, Kinder SJ, Kobayashi A, Kwan KM, Schughart K, Kania A, Jessell TM, Behringer RR, Tam PP: Lim1 activity is required for intermediate mesoderm differentiation in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol 223: 77–90, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saxen L, Toivonen S: The two-gradient hypothesis in primary induction. The combined effect of two types of inductors mixed in different ratios. J Embryol Exp Morphol 9: 514–533, 1961 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sims-Lucas S, Schaefer C, Bushnell D, Ho J, Logar A, Prochownik E, Gittes G, Bates CM: Endothelial progenitors exist within the kidney and lung mesenchyme. PLoS ONE 8: e65993, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schuck S, Manninen A, Honsho M, Füllekrug J, Simons K: Generation of single and double knockdowns in polarized epithelial cells by retrovirus-mediated RNA interference. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101: 4912–4917, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valerius MT, Patterson LT, Witte DP, Potter SS: Microarray analysis of novel cell lines representing two stages of metanephric mesenchyme differentiation. Mech Dev 112: 219–232, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Breitschopf H, Suchanek G, Gould RM, Colman DR, Lassmann H: In situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled probes: Sensitive and reliable detection method applied to myelinating rat brain. Acta Neuropathol 84: 581–587, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.