Abstract

Purpose

To systematically review the scientific level of evidence for the ‘Top 3’ risk factors, screening tests and preventative exercises identified by a previously published survey of 44 premier league football (soccer) teams. Also, to provide an overall scientific level of evidence and graded recommendation based on the current research literature.

Methods

A systematic literature search (Pubmed [MEDLINE], SportDiscus, PEDRO and Cochrane databases). The quality of the articles was assessed and a level of evidence (1++ to 4) was assigned. Level 1++ corresponded to the highest level of evidence available and 4, the lowest. A graded recommendation (A: strong, B: moderate, C: weak, D: insufficient evidence to assign a specific recommendation) for use in the practical setting was given.

Results

Fourteen studies were analysed. The overall level of evidence for the risk factors previous injury, fatigue and muscle imbalance were 2++, 4 and ‘inconclusive’, respectively. The graded recommendation for functional movement screen, psychological questionnaire and isokinetic muscle testing were all ‘D’. Hamstring eccentric had a weak graded ‘C’ recommendation, and eccentric exercise for other body parts was ‘D’. Balance/proprioception exercise to reduce ankle and knee sprain injury was assigned a graded recommendation ‘D’.

Conclusions

The majority of perceptions and practices of premier league teams have a low level of evidence and low graded recommendation. This does not imply that these perceptions and practices are not important or not valid, as it may simply be that they are yet to be sufficiently validated or refuted by research.

Keywords: prevention, exercise

Introduction

We surveyed the current perceptions and practices of 44 premier league football (soccer) teams from around the world regarding non-contact injuries.1 The three most important perceived risk factors were previous injury, fatigue and muscle imbalance. Additionally, the three most utilised screening tests to detect injury risk were functional movement screen (FMS), questionnaires and isokinetic muscle testing. Furthermore, the preventative exercises deemed the most important to prevent non-contact injuries were eccentric exercises and balance/proprioception. Specifically, eccentric exercise for the hamstring was independently ranked as the third most important exercise (table 1).

Table 1.

A summary of the key risk factors, screening tests and preventive exercises identified in 44 premier league football (soccer) teams.1

| Approach | Top 3 responses |

|---|---|

| Risk factors | Previous injury |

| Fatigue | |

| Muscle imbalance | |

| Screening tests | Functional movement screen |

| Questionnaire | |

| Isokinetic muscle testing | |

| Preventative exercises | Eccentric exercise |

| Balance/proprioception | |

| Hamstring eccentric |

There is, to our knowledge, no systematic review concerning injury prevention and professional football that has yet assigned a specific level of evidence for the consideration of risk factors and/or use of specific screening tests and preventative exercises based on the quality of studies. It is imperative that research can successfully guide practitioners and it is important they are provided with a level of evidence and recommendations so that they can be confident that they are implementing the current best evidence-based practice. Furthermore, researchers should be guided to concentrate on future research that ultimately will help guide practice.

The aim of the present article therefore was to systematically review the research literature for the aforementioned ‘Top 3’ risk factors, screening tests and preventative exercises and to provide a graded recommendation for their use and consideration in practice.

Methods

Literature search and selection process

This systematic review was performed following the guidelines of Harris et al.2 A systematic search of the scientific literature was performed via the PubMed (MEDLINE) and SportDiscus databases. Various combinations of the following keywords were used: ‘soccer, football, injury, risk, non-contact, prediction, prevention, test, muscle, strain, sprain, eccentric, balance, proprioception, stability, isokinetic, functional movement screen, fatigue, muscle imbalance, hamstring, groin, adductor, knee, ankle, calf, quadriceps’. This search was performed between 2 and 8 February 2014. Additionally, two research experts external to the present research group in the fields of ‘injury risk’, ‘injury risk testing’ and ‘injury prevention’ were contacted to reduce the risk of missing relevant articles.

An identical database search was performed again during 1 and 3 September 2014 (in response to journal reviewer comments). Two further databases (PEDRO and Cochrane) were added to further minimise the risk of missing important articles. Two of the principal authors independently performed the literature search on both occasions. For inclusion, the population had to consist of only elite male ‘Association football’ (ie, soccer) players ≥18 years. Association football was chosen in order to maximise correspondence with the previously published survey.1 An ‘elite’ player was defined as a player playing professionally in at least the top 3 divisions of any country. This was to account for differences in playing level of different countries as seen in the original survey.1 Prospective and retrospective studies published in any language were considered.

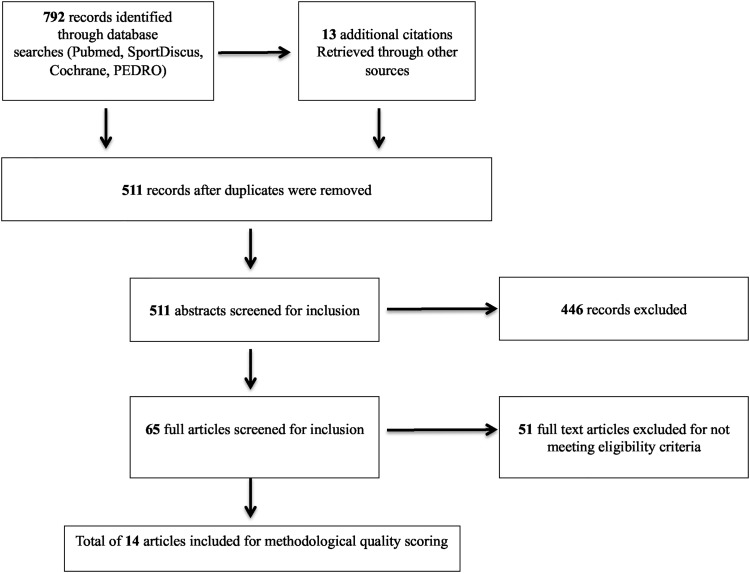

Studies were excluded if they contained non-professional players, females, other sports or focused on players <18 years. Returned abstracts were screened for inclusion. Full articles were then retrieved and included or excluded based on the criteria set out above. Reference lists of included articles were screened for additional papers. A ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ (PRISMA) flow chart was used to illustrate the study's identification, screening, eligibility, inclusion and analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

A ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses’ (PRISMA) flow chart outlining the study identification, screening, eligibility, inclusion and analysis for the present systematic review.

Methodological quality and level of evidence

The methodological quality of studies was assessed using a validated checklist for retrospective and prospective studies3 assessing aspects of 1: ‘reporting’, 2: ‘external validity’, 3: ‘internal validity—bias’, 4: ‘internal validity—confounding’ and 5: ‘power’. For analysis of risk factors and screening tests, questions not appropriate to cohort and descriptive epidemiology studies were excluded. Questions excluded were appropriate only for intervention studies. In this instance, questions included were 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 18, 20, 21, 22, 25 as previously used.4 For the quality check of preventative exercise articles (ie, intervention studies), all questions were included. Two principal authors (AM and CC) independently performed this quality check. Any disagreements were sent to corresponding author GD whose decision was final. A percentage score was awarded for each article. Articles were then assigned a ‘level of evidence’ following the procedure for grading recommendations in evidence-based guidelines from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN).5 Scientific levels of evidence range from 1 to 4 according to the type of study, for example, RCT, high-quality systematic review and meta-analysis are level 1; well-conducted systematic reviews, plus cohort and case–control studies are level 2; non-analytic studies are level 3 and expert opinion has a level of evidence of 4. Levels of 1 and 2 can score an additional mark of ‘++’, ‘+’ and ‘–’, according to the specific quality and risk of bias of the study. The percentage cut-off scores to determine if a paper was either (1) of high quality with very low risk of bias, (2) well conducted with low risk of bias or (3) low quality with high risk of bias were ≥75%, =50–74% and <50%, respectively.

Graded recommendation

Following the assignment of a level of evidence, a graded recommendation for each of the top 3 screening tests and preventative exercises was given following the SIGN guidelines.5 Graded recommendations involved assessment of the body of evidence (ie, all of the articles in that area) and their respective levels of evidence in conjunction with a considered subjective judgement by professionals. Graded recommendations were considered as A: Strong recommendation, B: Moderate recommendation, C: Weak recommendation or D: Insufficient evidence to make a specific recommendation. A graded recommendation was not assigned for the top 3 risk factors, as risk factors cannot be recommended. Instead, an ‘overall’ level of evidence was assigned for these. The considered judgement and graded recommendation/overall level of evidence were assigned during a round table of four researchers, all of whom were qualified with a PhD (2× sport scientists and 2× sports medicine doctors currently working in professional premier league football clubs).

Results

Search results

Fourteen articles were included for methodological quality assessment. The total number of articles assessed for ‘risk factors’ was previous injury (6 articles), fatigue (0 articles identified) and muscle imbalance (4). The ‘screening tests’ section included papers on functional movement screen (0 articles identified), questionnaire (1) and isokinetic muscle testing (4). Finally, the section concerning ‘preventative based exercises’ included studies on eccentric exercises (4) and balance/proprioception (1).

Overall graded recommendation

The overall level of evidence for risk factors and graded recommendations for screening tests and preventative exercises utilised are outlined in table 2.

Table 2.

Overall scientific level of evidence for the ‘top 3’ risk factors and graded recommendation for the ‘top 3’ screening tests and preventative exercises as rated by premier league teams

| Risk factor | Level of evidence |

| Previous injury | 2++ |

| Fatigue | 4 |

| Muscle imbalance | Inconclusive |

| Screening test | Graded recommendation |

| Functional movement screen | D |

| Questionnaire: Psychological evaluation | D |

| Isokinetic muscle testing | D |

| Preventative exercise | Graded recommendation |

| Hamstring eccentric | C |

| Other eccentric | D |

| Balance and proprioception: Knee and Ankle | D |

Methodological quality and characteristics of the studies

The quality score (%) and corresponding level of evidence are displayed in tables 3–9. The quality of risk factor articles ranged from 80% to 100%; screening test articles from 80% to 100%; and preventative exercises ranged from 54% to 74%. The individual breakdown of scoring of articles is shown in appendix A.

Table 3.

The quality score and scientific level of evidence for articles investigating previous injury as a risk factor for injury in professional footballers

| Study name | Study design | Participant details | Playing level | Main finding | Quality score (%) | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nordstrom et al6 | Prospective cohort | 1665 players from 46 teams over 10 countries | UEFA Champions League | Supports previous injury as a risk factor | 88 | 2++ |

| Hagglund et al7 | Prospective cohort | 1401 players from 26 teams over 10 countries | UEFA Champions League | Supports previous injury as a risk factor | 100 | 2++ |

| *Fousekis et al8 | Prospective cohort | 100 players from 4 teams | Greek 3rd Division | Does not support previous injury as a risk factor | 80 | 2++ |

| Walden et al9 | Prospective cohort | 310 players from 14 teams | Swedish Premier League | Supports previous injury as a risk factor | 100 | 2++ |

| Hagglund et al10 | Prospective cohort | 197 players from 12 teams | Swedish Premier League | Supports previous injury as a risk factor | 100 | 2++ |

| Arnason et al11 | Prospective cohort | 306 from 20 teams | Iceland Top 2 Divisions | Supports previous injury as a risk factor | 100 | 2++ |

*Articles used in more than 1 section.

Table 4.

The quality score and scientific level of evidence for articles investigating muscle imbalance as a risk factor for injury in professional footballers

| Study name | Study design | Participant details | Playing level | Main finding | Quality score (%) | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Fousekis et al12 | Prospective cohort | 100 players from 4 teams | Greek 3rd Division | Supports muscle imbalance as an injury risk factor and ankle injury | 87 | 2++ |

| *Fousekis et al8 | Prospective cohort | 100 players from 4 teams | Greek 3rd Division | Supports muscle imbalance and hamstring injury | 80 | 2++ |

| *Croisier et al13 | Prospective cohort | 462 players (n of teams not specified) | Brazilian, Belgian and French leagues (Specific level not specified) | Supports muscle imbalance and hamstring injury | 87 | 2++ |

| *Dauty et al14 | Prospective and Retrospective cohort | 28 players (n of teams not specified) | French League 1 | Does not support muscle imbalance and hamstring injury | 100 | 2++ |

*Articles used in more than 1 section.

Table 5.

The quality score and scientific level of evidence for articles investigating questionnaire as a screening test to identify injury risk in professional footballers

| Study name | Study design | Participant details | Playing level | Main finding | Quality score (%) | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devantier15 | Prospective cohort | 83 players from 5 teams | Danish Super League and 1st Division | Coping with adversity associated with injury | 87 | 2++ |

Table 6.

The quality score and scientific level of evidence for articles investigating isokinetic muscle testing as a screening test to identify injury risk in professional footballers

| Study name | Study design | Participant details | Playing level | Main finding | Quality score (%) | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| *Fousekis et al12 | Prospective cohort | 100 players from 4 teams | Greek 3rd Division | Supports isokinetic testing to identify ankle injury | 87 | 2++ |

| *Fousekis et al8 | Prospective cohort | 100 players from 4 teams | Greek 3rd Division | Supports isokinetic testing and hamstring injury | 80 | 2++ |

| *Croisier et al13 | Prospective cohort | 462 players (n of teams not specified) | Brazilian, Belgian and French leagues (Specific level not specified) | Supports isokinetic testing and hamstring injury | 87 | 2++ |

| *Dauty et al14 | Prospective and Retrospective cohort | 28 players (n of teams not specified) | French League 1 | Does not support isokinetic testing and hamstring injury | 100 | 2++ |

*Articles used in more than 1 section.

Table 7.

The quality score and scientific level of evidence for articles investigating hamstring eccentric exercise as a preventative exercise to prevent injury in professional footballers

| Study name | Study design | Participant details | Playing level | Main finding | Quality score (%) | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnason et al16 | Non-randomised controlled trial | 18 to 24 players per team: 24 to 31 teams | Icelandic Premier League and 1st Division Norwegian Premier League |

Supports hamstring eccentric exercise to prevent injuries | 54 | 2+ |

| *Croisier et al13 | Prospective cohort | 462 players (n of teams not specified) | Brazilian, Belgian and French leagues (Specific level not specified) | Supports hamstring eccentric exercise | 71 | 2+ |

| Askling et al17 | Randomised controlled trial | 30 players from 2 teams | Swedish Premier League | Supports hamstring eccentric exercise | 69 | 1+ |

*Article used in more than 1 section.

Table 8.

The quality score and scientific level of evidence for articles investigating ‘other’ eccentric exercise as a preventative exercise to prevent injury in professional footballers

| Study name | Study design | Participant details | Playing level | Main finding | Quality score (%) | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fredberg et al18 | Randomised-controlled trial | 209 players from 8 teams | Danish Super League | Does not support eccentric exercise for Achilles and patellar tendons to prevent injuries | 74 | 1++ |

Table 9.

The quality score and scientific level of evidence for investigating articles balance/proprioception exercise as a preventative exercise to prevent injury

| Study name | Study design | Participant details | Playing level | Main finding | Quality score (%) | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mohammadi19 | Randomised-controlled trial | 80 players (n of teams not specified) | 1st Division (country and league not specified) | Supports balance/proprioception exercise to prevent ankle injury | 57 | 1+ |

Injury risk factors

Previous injury

The level of evidence for each article assessing previous injury as a risk factor is reported in table 3. The overall level of evidence for previous injury as a risk factor for both injuries of the same type and/or another location is ‘2++’.

Fatigue

No articles met the inclusion criteria for investigation of fatigue as a risk factor in professional footballers. Therefore, the overall level of evidence is ‘4’ (expert opinion).

Muscle imbalance

The quality score and level of evidence for articles regarding muscle imbalance and injury risk are shown in table 4. There is insufficient research with contradictory results, which prevents an overall level of evidence being assigned for muscle imbalance and hamstring injury. Additionally, there is insufficient research to give an overall level of evidence for muscle imbalance and injury to other body parts.

Screening tests

Functional movement screen

No articles met the inclusion criteria for functional movement screen as a screening test to identify professional football players at risk of injury. Therefore, the graded recommendation for functional movement screen in elite football players is ‘D’.

Questionnaire

Only one article met the criteria for ‘Questionnaire’ and injury risk. The quality score and level of evidence for this article is provided in table 5. Questionnaires, as a tool for effectively determining previous injury, were not included. We have focused on ‘specifically themed’ questionnaires. The sole article identified was a psychological questionnaire. The graded recommendation for psychological questionnaires to identify injury risk is ‘D’.

Isokinetic muscle testing

The quality score and level of evidence for articles investigating isokinetic muscle testing as a tool to identify injury risk in professional footballers can be found in table 6. The current research findings for isokinetic muscle testing to identify hamstring strain risk in professional footballers are limited and inconclusive. Additionally, there is insufficient evidence for isokinetic muscle testing and injury risk in other body parts. Therefore, the graded recommendation for isokinetic muscle testing to identify injury in professional footballers is currently ‘D’.

Preventative exercises

Eccentric exercise

The quality score and level of evidence for articles concerning eccentric exercise and injury prevention are presented in tables 7 and 8. The graded recommendation for hamstring eccentric exercise to prevent hamstring injury in professional footballers is ‘C’. The graded recommendation for eccentric exercise to prevent injuries other than hamstrings is ‘D’.

Balance/proprioception

Only one study met the criteria to be included in the section concerning balance/proprioception exercise as a preventative exercise (table 9). The level of evidence for this single study is 1+. The graded recommendation for balance/proprioception exercise to prevent ankle sprain injury is ‘D’. No study checked the effects of balance/proprioception exercise in professional footballers on the incidence of knee injuries. The graded recommendation for balance/proprioception exercise and knee injuries is also ‘D’.

Discussion

We aimed to analyse the gap between science and practice by systematically reviewing common injury prevention perceptions and practices. We assigned a level of evidence and graded recommendation to help guide practitioners to make the best decisions and use the best evidence-based practices in the practical setting. We also aimed to provide direction for researchers in regard to where to concentrate future research into risk factors, screening tests and preventative exercises for professional footballers based on what is actually performed in practice.

Risk factors

Previous injury

The level of evidence for previous injury as a risk factor is ‘2++’. According to the grading guidelines used, a level of evidence 2++ is the highest available for cohort studies.

Previous injury in professional footballers can increase the risk of injury of the same type and on the same side.6 7 9–11 Interestingly, previous injuries do not necessarily have to be anatomically related to increase the risk of injury of another type.6 7 Although one study8 found that previous hamstring injury reduced the risk of future hamstring injury, it should be noted that in this study a players’ previous injury status was determined through a player questionnaire. Recall bias may affect the accuracy of previous injury history.

Although previous injury is a non-modifiable risk factor, knowledge of non-modifiable risk factors may be used to target intervention measures in those at risk.20

In regard to directions for future research, the specific risk factors involved in the recurrence of injury have not been clearly established but may relate to the factors that were associated with the initial injury7 and therefore warrant further investigation. In addition, factors related to modifications after the initial injury (tightness, muscle weakness, presence of scar tissue, biomechanical alterations and neuromuscular inhibition) may predispose a player to another injury.7 Thus, research should determine what consequences are associated with previous injury, how these can be validly measured and what interventions can reverse or reduce these consequences.

Fatigue

The overall level of evidence for fatigue as a risk factor is ‘4’ (expert opinion). Fatigue during a football match is a potential cause of injuries in professional football.21 Note that injuries are more common at the end of halves of professional football matches.21–23 Such observations are reported alongside studies reporting a concomitant reduction in muscle force production at the end of matches, for example, reduced hamstring force in response to football specific exercise.24 25 In addition to the acute/transient fatigue occurring at various time points during a match (following intense bouts of high-intensity activity) and the cumulative fatigue suggested to occur throughout the course of a match, another type of cumulative fatigue has been postulated as a potential risk factor.26 This third type of fatigue has been suggested due to studies showing a higher injury incidence when playing two matches compared to one match per week, where recovery time is reduced.27 28 Despite this common belief and studies suggesting indirectly that ‘fatigue’ may be associated with injury, no scientific evidence supports this theory.

The evaluation of fatigue as a risk factor in football is complex and problematic. In part, an issue with ascribing a relationship between ‘fatigue’ and injury is the lack of an appropriate definition of fatigue in the first place, that is both appropriate and measurable in a field-based setting. One definition of fatigue is the repeated intense use of muscles, which leads to a decline in performance.29 There are, however, many different activities that lead to fatigue, and an important challenge is to identify the various mechanisms that contribute under different circumstances.29 Before even contemplating to begin to quantify fatigue in football, it is imperative that consensus is achieved on the definition of fatigue and how to identify the different mechanisms in a variety of situations, for example, during match-play or as a result of fixture congestion.

Muscle imbalance

The overall level of evidence for muscle imbalance is inconclusive as research findings are limited and contradictory. In one study, professional footballers with untreated strength imbalance had greater risk of injury than players whose muscle imbalances were corrected to within 5%.13 However, the specific muscle imbalances were not specified. Eccentric hamstring asymmetry (>15%) was a significant predictor of injury.8 However, a mixed hamstring (eccentric) : quadriceps (concentric) ratio detected previous hamstring injury but did not predict recurrent or new injuries.14

There is a dearth of data on whether imbalance of other muscle groups is associated with injury risk. One study exists on professional footballers,12 which reported that eccentric asymmetry (≥15%) of ankle dorsal and plantar flexors predicted ankle sprain. Thus, at present, it is not known whether muscle imbalance is a risk factor for injury in professional football.

As is the case of ‘fatigue’, ‘muscle-imbalance’ is a term used ambiguously—it has no specific definition. A consensus on the definition of muscle imbalance and its adoption, would be a useful advance.

Screening tests

Functional movement screen

The overall level of evidence for functional movement screen is ‘4’ (expert opinion) with a graded recommendation ‘D’. This screening test is the most commonly used by premier league teams.1 Practitioners should be aware of the potential limitations of using functional movement screening. Specifically, caution should be used with this test as the scores have been shown to change when performers are made aware of the grading criteria.30 Additionally, adequate training for the FMS tester should be ensured to improve the reliability of this testing modality.31 Interestingly, some premier league teams use their own ‘adapted’ version of the FMS.1 It is imperative that research investigates reliability and validity of the functional movement screen as test to identify players who possess one or more risk factor for injury in addition to determining its sensitivity to detect changes in response to injury prevention training interventions.

It would also be worthwhile to investigate which modifications to the functional movement screen practitioners are implementing and the reasons why in order for research to determine the reliability, validity and sensitivity of these ‘in-house’ tests and whether they can identify players who may possess one or more risk factors. Unfortunately, such information may, however, be difficult to obtain from teams.

Questionnaire

The only questionnaire in the research literature that met the inclusion criteria concerned a psychological evaluation. The level of evidence for the single article using a psychological evaluation is ‘2++’ with ‘psychological questionnaire’ as a screening test scoring an overall graded recommendation ‘D’. ‘Coping with adversity’ was associated with injury.15 Psychological factors should be studied further in order to determine which psychological factors constitute a risk factor and to guide potential future questionnaires that may identify players who exhibit psychological risk factors. Additionally, it is necessary to determine the specific questionnaires that teams are currently implementing, that is, what questions they are asking before being able to direct future research to validate or refute their use in the practical setting.

Isokinetic muscle testing

The level of evidence for isokinetic muscle testing is ‘inconclusive’ and therefore is assigned a graded recommendation ‘D’. Isokinetic muscle testing does not necessarily imply that muscle imbalance must be the outcome measure. It is possible to assess other strength qualities such as strength endurance, resistance to fatigue, peak strength and/or optimal angle of peak strength, however, there are no studies investigating these parameters and injury risk in elite footballers. Additionally, with no consensus on what muscle imbalance actually is defined as and what measures actually constitute a significant risk factor (if at all) in professional players it is impossible to validate or refute isokinetic muscle testing as a screening test to identify players possessing a potential injury risk related to strength. It is important to also point out that there are other methods that can be used to measure muscle strength qualities. Previous studies have used a sphygmomanometer,32 33 force plate34 and non-motorised treadmill.35

Preventative exercises

Eccentric exercise

The overall level of evidence for articles investigating eccentric exercise and hamstring injury is ‘2+’. The graded recommendation for hamstring eccentric exercise specifically to prevent hamstring injury in professional footballers is ‘C’. Despite the considerable importance placed on hamstring eccentric exercises in premier league football teams,1 to the authors’ surprise their graded recommendation is currently weak. Despite the inclusion of three studies suggesting that eccentric hamstring overload can be effective to reduce hamstring strains, it cannot be determined conclusively if it is in fact the eccentric component that is responsible. In two studies13 16 the eccentric exercise was performed in conjunction with other exercise types. In another investigation17 the intervention exercise also included a considerable concentric component in which eccentric and concentric knee flexor strength both increased (19% and 15%, respectively). However, prevention programmes in the practical setting involve a multidimensional approach with the combination of various exercises, therefore these exercises should be recommended to remain a part of a team’s programme.

The level of evidence for eccentric exercise for other body locations is ‘4’ (expert opinion) and graded recommendation ‘D’. There is currently no scientific evidence for their use in this population. Importantly, in addition to finding no significant beneficial effect of eccentric exercise for the Achilles or patellar tendons,18 this type of exercise increased the risk of developing symptoms of jumper’s knee from 5% to 24% in players with ultrasonographically severely abnormal patellar tendons. As eccentric exercise is considered the most important exercise in a team’s injury prevention programme,1 practitioners need to be aware of the potential adverse effects of eccentric exercise for other parts of the body before incorporating them into their programme.

Owing to the importance that sports medicine and science practitioners from elite football teams place on eccentric exercises,1 research must determine their contribution in preventing injuries in this setting. Also, the question of whether such exercises may be contraindicated needs answering. In addition, guidelines for the optimal programming of such exercises in a multifaceted injury prevention programme should be investigated. Future research should also include measures to determine the implementation strategies and compliance of prevention programmes as these factors appear to be essential for maximum effectiveness.

Balance/proprioception

The level of evidence for the single study concerning balance/proprioception exercise to prevent ankle sprain is ‘1+’ with a graded recommendation ‘D’. Mohammadi19 found that proprioception training resulted in significantly lower ankle injury rates compared to other preventative strategies: (1) ankle strength training, (2) using orthoses and (3) control group. Regarding knee injuries, the level of evidence was ‘4’ (expert opinion) with a graded recommendation ‘D’. Future research is required to determine the effectiveness and optimal protocol for balance/proprioception exercises for the prevention of ankle and knee injuries in professional footballers.

Despite the low level of evidence and weak graded recommendation for these exercises, no adverse effects of a structured balance/proprioception exercise programme have, to our knowledge, been reported and, as such, practitioners can continue to incorporate these safely in the overall prevention programme. Researchers should be encouraged to validate or refute this perception of the importance of balance/proprioception exercise to effectively reduce injury rates.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, the specificity of analysing only articles from ‘Association Football’ may have diluted the overall findings. It may be possible that there can be some extrapolation from studies relating to other football codes and/or athletic populations. However, our objective was to follow-up the responses of practitioners from our previously published survey in association football1 and this specificity could arguably be deemed essential. Our study generally highlights the scarcity of publications and research in the professional football setting.36

Second, there is no clear definition in the research literature on what is an ‘elite’ or ‘sub-elite’ player. The definition used for the purpose of this systematic review was a player playing professionally in one of the top 3 divisions of a country. It may be that the definition of ‘elite’ player corresponds to those competing in the major competitions such as UEFA Champions League and in the top countries of the FIFA confederations; below that level, players could be considered subelite. However, due to the variation in playing level of premier league teams surveyed previously,1 the current systematic review used the above definition to take into account differences between the teams.

Conclusion

The present systematic review analysed the gap between what is perceived and performed in practice in professional football regarding risk factors, screening tests and preventative exercises for non-contact injuries, with the published evidence. The relation between practice and science can be analysed in two ways: the application of scientific recommendations by practitioners (from science to practice) and the scientific validation of practices by the researchers (from practice to science). Our systematic review shows that most of the perceptions and practices of practitioners are not supported by scientifically validated recommendations from research. Further investigation is required by researchers to validate or refute the perceptions and practices used in the practical setting to close the gap between science and practice.

What are the new findings?

- We have determined the scientific level of evidence of the following injury risk factors for professional football players:

- Previous injury

- Fatigue

- Muscle imbalance

- We have provided a graded recommendation for use of screening tests to identify injury risk in professional football players:

- Functional movement screen

- Psychological questionnaire

- Isokinetic muscle testing

- We have also provided a graded recommendation for use in the field of exercises to aid injury prevention:

- Hamstring eccentric

- ‘Other’ eccentric

- Balance/proprioception

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AM and GD conceived of the idea for the systematic review. AM and CC performed the literature search. AM and CC conducted the methodological quality check. GD had final decision on quality check when not agreed on by AM and CC. MD, MN, SB and FLG performed further literature search to ensure no articles were missing. AM contacted three authors in each category to ensure no important articles were missed. AM wrote the initial draft of the article. All coauthors contributed to final draft of the article. AM, GD, CC and MD prepared the manuscript to be submitted. AM submitted the article. All authors contributed to the revised manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.McCall A, Carling C, Nedelec M, et al. Risk factors, testing and preventative strategies for non-contact injuries in professional football: current perceptions and practices of 44 teams from various premier leagues. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1352–7. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris JD, Quatman CE, Manring MM, et al. How to write a systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:2761–8. 10.1177/0363546513497567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downs SH and Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:377–84. 10.1136/jech.52.6.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freckleton G, Pizzari T. Risk factors for hamstring muscle strain injury in sport: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2012;47:351–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harbour R, Miller J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ 2001;323:334–6. 10.1136/bmj.323.7308.334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordstrom A, Nordstrom P, Ekstrand J. Sports-related concussion increases the risk of subsequent injury by about 50% in elite male football players. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1447–50. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagglund M, Walden M, Ekstrand J. Risk factors for lower extremity muscle injury in professional soccer: the UEFA Injury Study. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:327–35. 10.1177/0363546512470634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fousekis K, Tsepis E, Poulmedis P, et al. Intrinsic risk factors of noncontact quadriceps and hamstring strains in soccer: a prospective study of 100 professional players. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:709–14. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.077560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walden M, Hagglund M, Ekstrand J. High risk of new knee injury in elite footballers with previous anterior cruciate ligament injury. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:158–62. 10.1136/bjsm.2005.021055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagglund M, Walden M, Ekstrand J. Previous injury as a risk factor for injury in elite football: a prospective study over two consecutive seasons. Br J Sports Med 2006;40:767–72. 10.1136/bjsm.2006.026609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnason A, Sigurdsson SB, Gudmundsson A, et al. Risk factors for injuries in football. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:5S–16. 10.1177/0363546503258912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fousekis K, Tsepis E, Vagenas G, et al. Intrinsic risk factors of noncontact ankle sprains in soccer: a prospective study of 100 professional players. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:1842–50. 10.1177/0363546512449602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croisier JL, Ganteaume S, Binet J, et al. Strength imbalances and prevention of hamstring injury in professional soccer players: a prospective study. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:1469–75. 10.1177/0363546508316764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dauty M, Potiron-Josse M, Rochcongar P. Consequences and prediction of hamstring muscle injury with concentric and eccentric isokinetic parameters in elite soccer players. Ann Readapt Med Phys 2003;46:601–6. 10.1016/j.annrmp.2003.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devantier C. Psychological predictors of injury among professional soccer players. Sport Sci Rev 2012;20:5–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnason A, Andersen TE, Holme I, et al. Prevention of hamstring strains in elite soccer: an intervention study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2008;18:40–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00634.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Askling C, Karlsson J, Thorstensson A. Hamstring injury occurrence in elite soccer players after preseason strength training with eccentric overload. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2003;13:244–50. 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.00312.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fredberg U, Bolviig L and Andersen NT. Prophylactic training in asymptomatic soccer players with ultrasonographic abnormalities in Achilles and patellar tendons: the Danish Super League Study. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:451–60. 10.1177/0363546507310073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohammadi F. Comparison of 3 preventative methods to reduce the recurrence of ankle inversion sprains in male soccer players. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:922–6. 10.1177/0363546507299259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bahr R, Van Mechelen W, Kannus P. Prevention of sports injuries. In: MacAuley D ed. Basic Science and Clinical Aspects of Sports Injury and Physical Activity. Oxford: Blackwell Science 2002:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ekstrand J, Hagglund M, Walden M. Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football: the UEFA injury study. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:553–8. 10.1136/bjsm.2009.060582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods C, Hawkins RD, Maltby S, et al. The Football Association Medical Research Programme: an audit of injuries in professional football-analysis of hamstring injuries. Br J Sports Med 2004;38:36–41. 10.1136/bjsm.2002.002352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawkins RD, Hulse MA, Wilkinson C, et al. The association football medical research programme: an audit of injuries in professional football. Br J Sports Med 2001;35:43–7. 10.1136/bjsm.35.1.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Small K, McNaughton L, Greig M, et al. The effects of multidirectional soccer-specific fatigue on markers of hamstring injury risk. J Sci Med Sport 2010;13:120–5. 10.1016/j.jsams.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greig M. The influence of soccer-specific fatigue on peak isokinetic torque production of the knee flexors and extensors. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:1403–9. 10.1177/0363546508314413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nédélec M, McCall A, Carling C, et al. Recovery in soccer; part I—post-match fatigue and time course of recovery. Sports Med 2012;42:997–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bengtsson H, Ekstrand J, Hagglund M. Muscle injury rates in professional football increase with fixture congestion: an 11 year follow up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:743–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dupont G, Nedelec M, McCall A, et al. Effect of 2 soccer matches a week on physical performance and injury rate. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:1752–8. 10.1177/0363546510361236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allen DG, Lamb GD, Westerblad H. Skeletal muscle fatigue: cellular mechanisms. Physiol Rev 2008;88:287–332. 10.1152/physrev.00015.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frost DM, Beach TA, Callaghan JP, et al. FMS™ scores change with performers' knowledge of the grading criteria – Are general whole-body movement screens capturing “dysfunction”? capturing ‘dysfunction’? J Strength Cond Res. Published Online First: 20 Nov 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shultz R, Anderson SC, Matheson GO, et al. Test-retest and interrater reliability of the functional movement screen. J Athl Train 2013;48:331–6. 10.4085/1062-6050-48.2.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nedelec M, McCall A, Carling C, et al. The influence of playing actions on the recovery kinetics after a soccer match. J Strength Cond Res 2014;28:1517–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schache AG, Crossley KM, Macindoe IG, et al. Can a clinical test of hamstring strength identify football players at risk of hamstring strength? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:38–41. 10.1007/s00167-010-1221-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verdera F, Champavier L, Schmidt C, et al. Reliability and validitiy of a new device to measure isometric strength in polyarticular exercises. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 1999;39:113–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brughelli M, Cronin J, Mendiguchia J, et al. Contralateral leg deficits in kinetic and kinematic variables during running in Australian rules football players with previous hamstring injuries. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:2539–44. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b603ef [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ekstrand J, Dvorak J, D'Hooghe M. Sports medicine research needs funding: the international football federations are leading the way. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:726–8. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.