Abstract

Objective To compare the annual prevalence of the autism symptom phenotype and of registered diagnoses for autism spectrum disorder during a 10 year period in children.

Design Population based study.

Setting Child and Adolescent Twin Study and national patient register, Sweden.

Participants 19 993 twins (190 with autism spectrum disorder) and all children (n=1 078 975; 4620 with autism spectrum disorder) born in Sweden over a 10 year period from 1993 to 2002.

Main outcome measures Annual prevalence of the autism symptom phenotype (that is, symptoms on which the diagnostic criteria are based) assessed by a validated parental telephone interview (the Autism-Tics, ADHD and other Comorbidities inventory), and annual prevalence of reported diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder in the national patient register.

Results The annual prevalence of the autism symptom phenotype was stable during the 10 year period (P=0.87 for linear time trend). In contrast, there was a monotonic significant increase in prevalence of registered diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder in the national patient register (P<0.001 for linear trend).

Conclusions The prevalence of the autism symptom phenotype has remained stable in children in Sweden while the official prevalence for registered, clinically diagnosed, autism spectrum disorder has increased substantially. This suggests that administrative changes, affecting the registered prevalence, rather than secular factors affecting the pathogenesis, are important for the increase in reported prevalence of autism spectrum disorder.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder comprises a group of disorders characterised by deficits in social communication interaction and behavioural flexibility.1 From the 1970s and onwards the reported prevalence of autism spectrum disorder has increased substantially. The condition was considered rare, affecting fewer than 0.05% of the population,2 3 4 5 but it is now generally agreed that the lifetime prevalence is at least 1% in both young people and adults.6 7 Several of the most recent studies report an even higher prevalence; researchers in South Korea estimated the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder or pervasive developmental disorder in 7-12 year olds to be 2.6% using a screening procedure followed up by a clinical assessment.8 In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported a monotonic increase of autism spectrum disorder in school aged children, peaking at 2% in 2012.9 This figure was obtained by a telephone survey where parents were asked if they had ever been told by a healthcare provider that their child had an autism spectrum disorder, and if their child currently had an autism spectrum disorder. Finally, a record linkage study in Sweden, using a multisource approach of all trajectories to a diagnosis of an autism spectrum disorder in Stockholm county, reported that 2.5% of all teenagers had received a clinical diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.10

Despite the increase in reported prevalence of autism spectrum disorder, there is no direct evidence that this corresponds to an increase in the prevalence of the autism phenotype—that is, the symptoms on which the diagnostic criteria are based. This is due to several factors. Firstly, the increase in the prevalence was reported during a period of repeated modifications and often broadening of diagnostic criteria,4 which clearly affects the reported prevalence.11 12 Secondly, increasing awareness of autism spectrum disorder is associated with diagnostic substitution across categories. It has been estimated that one third of the prevalence increase of autism spectrum disorder between 1996 and 2004 could be attributed to diagnostic substitution,13 and the increase in autism spectrum disorder has been suggested to parallel a decrease in learning disabilities and mental retardation.14 15 Thirdly, prevalence is also sensitive to referral patterns and availability of services.16 Finally, methodological differences in case ascertainment and assessment alter prevalence—for instance, the availability of, and discrepancies within, official records give rise to large variations between measured and actual prevalence in similar geographical regions.17 Consequently, the reported increase in prevalence of autism spectrum disorder remains difficult to interpret. Determining if the prevalence is actually increasing has major public health implications, such as in the allocation of adequate health resources and research efforts to find the causes of autism spectrum disorder.

We monitored the annual prevalence of the autism symptom phenotype in children born between 1993 and 2002 in a Swedish total population twin sample using the same validated instrument, and contrasted these data with the annual prevalence of clinical diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder according to data held in the national patient register in Sweden. By comparing a standardised measure in an assessed and defined population sample with clinical service diagnostic records by services for the same area, we hoped to clarify whether differences in diagnostic rates represent the population prevalence measured independently of services.

Methods

Participants

We used two sources to estimate the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden and the Swedish national patient register. These studies have ethical approval from the Karolinska Institutet ethical review board (Dnr 02-289 and 2010/507-31/1).

Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden

Beginning in 2004 the parents of all Swedish twins born since July 1992 are contacted in connection with the twins’ ninth or 12th birthday; twins born from 1 July 1992 to 31 June 1995 were included at age 12. After that (those born from 1 July 1995 onwards) only 9 year olds are included and asked to participate in the ongoing Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden. The study has a response rate of 75% and is described in detail elsewhere.18 In the present study we included 19 993 twins born in the 10 year period from 1 January 1993 to 31 December 2002 whose parents had responded to the Autism-Tics, ADHD and other Comorbidities inventory.

The Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden contains a psychiatric telephone interview, the Autism-Tics, ADHD and other Comorbidities inventory,19 which is a fully structured interview and was designed for use by laymen over the telephone. It consists of 96 questions, of which 17 correspond to an autism spectrum disorder domain, with an α of 0.86,18 and are scored 1 for “yes,” 0.5 for “yes, to some extent,” and 0 for “no.” Out of the 17 items, six correspond to a language and communication module, six to a social interaction module, and five to a restricted and repetitive behaviour module. We used a clinically validated cut-off for autism spectrum disorder of ≥8.5 to define the autism symptom phenotype. This cut-off has a Cohen’s κ value of 1.0,20 sensitivity of 0.71, and specificity of 0.95 for autism spectrum disorder when cases are compared cross sectionally with controls, and 0.61 and 0.91, respectively, when compared with a community sample.21 In addition, a clinical longitudinal follow-up assessment yielded a sensitivity of 0.30 and specificity of 0.99 for autism spectrum disorder.22 The domain has also been independently validated by other researchers, and excellent psychometric properties have been reported.23

The 17 questions constituting the basis for the autism spectrum disorder domain have been the same since the start of the study. They were modelled around the pervasive developmental disorder (autistic disorder, 299.00) phenotype of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition.24 To increase reliability and validity, the Autism-Tics, ADHD and other Comorbidities inventory was constructed so as not to disclose which questions pertain to which disorder, to be administered by laymen over the phone and thus be independent of clinical preference or knowledge, to avoid adherence to mutually exclusive criteria, and to evaluate lifetime presence of symptoms and behaviours. Taken together, this structure removes biases resulting from increased public and professional awareness, diagnostic substitution, changes in diagnostic concepts, and age at referral, making the Autism-Tics, ADHD and other Comorbidities inventory suitable for the identification of real changes in the prevalence of proxy diagnoses for autism spectrum disorder over time. The inventory is freely available as an appendix.21

National patient register

At birth, or on receiving Swedish citizenship, all individuals living in Sweden are assigned a personal identification number, which enables linkage across health and service registers. The Swedish national patient register25 provided data on all inpatient psychiatric care from 1987-2009 and includes best estimate specialist diagnoses assigned according to ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes (international classification of diseases, ninth and 10th revisions, respectively).26 27 Since 2001 the national patient register also includes information from outpatient consultations with specialists. To estimate the population prevalence of reported diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder we used data from the national patient register on 1 078 975 children born from 1 January 1993 to 31 December 2002. Diagnostic codes retrieved were: ICD-9 299A and ICD-10 f84.0, f84.1, f84.5, and f84.9. The validity of the national patient register is continuously monitored; in a validation study that included the national patient register,28 the agreement for a registered diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder with diagnosis made after careful scrutiny of the medical records on which the registered diagnosis was made was reported to be 96.0% (confidence interval 92.0% to 98.4%).28 In the current study we evaluated the correctness of the diagnosis of cases listed in the register but did not estimate false negative results. Therefore although the positive predictive value is high, the prevalence can increase without affecting the positive predictive value.

Comparison between the register and the twin study

To allow comparability with data from the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden we only included children who had been born between 1 January 1993 and 31 December 2002, had been given a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, and appeared in the national patient register before their 10th birthday. Given that the register currently includes diagnostic data up to 31 December 2009, children born during 2000-02 had only 7-9 years of follow-up, whereas those born before 2000 had a follow-up of 10 years. We then merged the data from the twin study with that from the national patient register. (See supplementary table 1 on bmj.com for a description of the annual agreement between Autism-Tics, ADHD and other Comorbidities inventory and the national patient register in people screen positive for an autism spectrum disorder.) The sensitivity and specificity for a diagnosis based on the Autism-Tics, ADHD and other Comorbidities inventory in the national patient register was 0.51 and 0.99, respectively. Finally, we compared the annual prevalence of diagnoses in the national patient register in all twins born in Sweden between 1993 and 2002, including non-responders in the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden (n=26 953, see supplementary table 2 on bmj.com) with the overall population in the national patient register data.

Statistical analysis

We grouped the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder on an annual basis separately for the autism symptom phenotype in the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden (cut-off ≥8.5) and the national patient register (clinical diagnosis) samples; we used Wald type 95% confidence intervals. To carry out the Cochrane-Armitage test for trend, we used the PROC FREQ procedure in SAS to model time trends in prevalence across birth years and for the autism symptom phenotype and clinical diagnosis separately. The PROC REG procedure was used to conduct a linear regression with the mean annual prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (symptom phenotype and clinical diagnosis separately) as the dependent variable, and year of birth as the independent variable.

Sensitivity analyses were also conducted for a broader cut-off of screening symptom score (≥4.5, sensitivity 0.91, specificity 0.8021), applying the same analyses as described previously. In addition we applied the analysis of variance model using PROC ANOVA in SAS to test for differences between birth years in the continuous autism score derived from the 17 items constituting the autism spectrum disorder domain. TUKEY’s test was used for paired comparisons.

We aimed to detect if there was a trend towards non-responders being more likely to be given a diagnosis throughout the years. To do this we conducted a logistic regression using PROC LOGISTIC in SAS with the annual prevalence of autism spectrum disorder from the national patient register as the dependent variable and year of birth, response in the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden, and their interaction as predictors (as1995 included no national patient register diagnoses in the non-responders we combined this category with that of 1994). The interaction effect captures whether the ratio of national patient register diagnoses in responders versus non-responders changes significantly by year of birth; the interaction was non-significant (Wald χ2 test 7.71, degrees of freedom 8, P=0.46). (See supplementary table 4 on bmj.com for descriptive statistics.)

Patient involvement

There was no patient involvement in this study.

Results

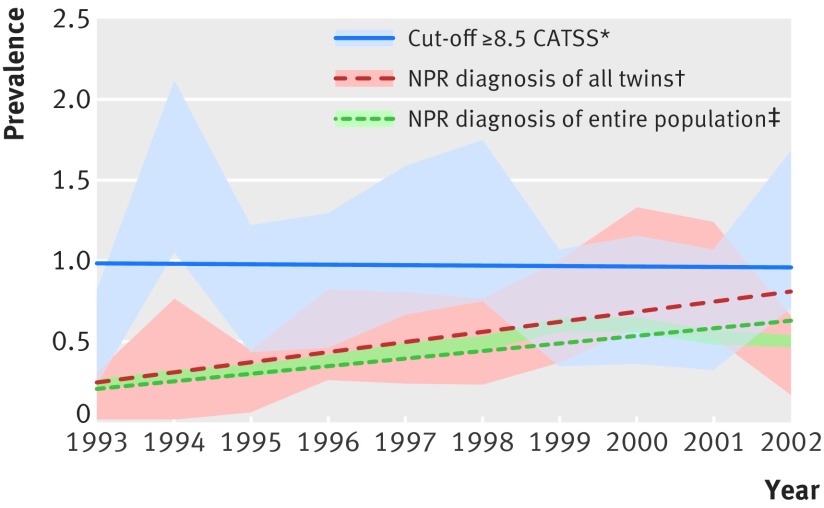

Tables 1 and 2 present descriptive statistics and the prevalence for each birth year from the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden and the national patient register as well as the sensitivity analyses. In the twin study the population prevalence of the autism symptom phenotype was 0.95% and the estimates for the 10 time points ranged from 0.52-1.59% (figure), with overlapping confidence intervals at all time points (except 1993 v 1994). The effect of time was not significant (P=0.85 for test of time trend) and the regression analysis showed no effect of birth year (R2=0.003, F0.023, P=0.882). The categorical sensitivity analyses (cut-off ≥4.5) revealed no time trend in the trend analyses (P=0.55) nor in the regression analysis (R2=0.019, F0.154, P=0.705). However, the continuous analyses on the autism score differed significantly (P=0.002) although with overlapping confidence intervals at all time points. In supplementary table 3 the means of the three modules (language or communication, social interaction, and restricted and repetitive behaviour) constituting the autism score are presented on an annual basis.

Table 1.

Descriptive data on children born 1 January 1993 to 31 December 2002 in Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden, and in the national patient register

| Cut-off | ASD/non-ASD per birth year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | |

| ≥8.5 | 12/2286 | 34/2100 | 17/2053 | 17/1926 | 23/2025 | 23/1835 | 14/1979 | 14/1826 | 13/1863 | 23/1910 |

| ≥4.5 | 68/2230 | 95/2039 | 66/2004 | 49/1894 | 68/1980 | 59/1799 | 71/1922 | 54/1786 | 61/1815 | 81/1852 |

| Registered diagnosis | 303/129 710 | 375/1 23 386 | 361/114 121 | 409/105 626 | 454/100 673 | 472/99 100 | 592/97 786 | 600/99 825 | 532/100 076 | 522/104 052 |

ASD=autism spectrum disorder.

Table 2.

Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder for each birth year from Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden and national patient register

| Data sources | Prevalence (95% CI) per birth year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | |

| Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden | ||||||||||

| Cut-off scores: | ||||||||||

| ≥8.5 | 0.52 (0.23 to 0.82) | 1.59 (1.06 to 2.12) | 0.82 (0.43 to 1.21) | 0.87 (0.46 to 1.29) | 1.12 (0.67 to 1.58) | 1.24 (0.74 to 1.74) | 0.70 (0.34 to 1.07) | 0.76 (0.36 to 1.16) | 0.69 (0.32 to 1.07) | 1.19 (0.71 to 1.67) |

| ≥4.5 | 2.96 (2.27 to 3.65) | 4.45 (3.58 to 5.33) | 3.19 (2.43 to 3.95) | 2.52 (1.82 to 3.22) | 3.32 (2.62 to 4.19) | 3.18 (2.38 to 3.97) | 3.56 (2.75 to 4.83) | 2.93 (2.16 to 3.71) | 3.25 (2.45 to 4.05) | 4.19 (3.30 to 5.08) |

| Autism score* | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.79) | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.91) | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.84) | 0.72 (0.65 to 0.78) | 0.73 (0.66 to 0.80) | 0.79 (0.71 to 0.86) | 0.77 (0.71 to 0.84) | 0.67 (0.61 to 0.74) | 0.74 (0.67 to 0.80) | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.93) |

| National patient register | ||||||||||

| Registered diagnosis | 0.23 (0.21 to 0.26) | 0.30 (0.27 to 0.33) | 0.32 (0.28 to 0.35) | 0.39 (0.35 to 0.42) | 0.45 (0.41 to 0.49) | 0.47 (0.43 to 0.52) | 0.60 (0.55 to 0.65) | 0.60 (0.55 to 0.65) | 0.53 (0.48 to 0.57) | 0.50 (0.46 to 0.54) |

*Based on same number of participants as for cut-offs scores of ≥8.5 and ≥4.5.

Annual prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden (CATSS), national patient register (NPR), and NPR diagnoses in Swedish twins. *Prevalence calculated on 19 993 people responding in twin study born 1993-2002. †Prevalence calculated on all twins, irrespective of response in CATTS (n=26 953). Diagnosis in NPR was ascribed before the children’s 10th birthday. ‡Prevalence calculated on all births in Sweden 1993-2002 (n=1 078 975). Diagnosis in NPR was ascribed before the children’s 10th birthday. Regression lines are depicted within 95% confidence intervals

In the national patient register the population prevalence was 0.42% (n=4620) and the estimates ranged from 0.23-0.60%. There was an almost linear increase over the examined years (except for children born during 2000-02, where the follow-up was <10 years) and the test for time trend was significant (P<0.001). The effect of birth year was further supported by the results of the linear regression analysis (R2=0.778, F28.00, P=0.001).

Estimates of population prevalence were similar in twins in the national patient register, irrespective of participation in the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden; 0.54%, albeit with some variation in point estimates. At each time point the confidence intervals overlapped between twins in the national patient register and those in the general population. The test for the time trend was significant (P<0.001) and the regression analysis showed an effect of birth year (R2=0.401 F5.35, P=0.049 (figure, also see supplementary table 2 on bmj.com).

Discussion

Using unique, large Swedish population based resources, we found that the annual prevalence of the autism symptom phenotype was stable over a 10 year period when investigating 9 and 12 year old children, while simultaneously the annual prevalence of clinically diagnosed autism spectrum disorder in a service based register steadily increased. In summary, our data do not support a secular increase in the rate of the autism symptom phenotype, suggesting that administrative factors that affect the registered prevalence may account for much of the rise in the reported prevalence of autism spectrum disorder.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The main strengths of this study include the large sample sizes, the high response rate in a nationwide study, and the use of a validated instrument for assessment, which removes biases of increased public and professional awareness, diagnostic substitution, changes in diagnostic concepts, and age at referral.

Our findings must be seen in the light of some limitations. The Autism-Tics, ADHD and other Comorbidities inventory does not have perfect sensitivity or specificity, meaning that some degree of “diagnostic misclassification” should be expected. However, the fact that the autism symptom phenotype appeared to be constant over time argues strongly against this being a major limiting factor. If autism spectrum disorder had really increased in the population, the prevalence of the symptomatic phenotype would have been expected to increase in a similar way. Also, clinical examinations, which in an ideal study might have been preferred, are not feasible in a nationwide study sample and might be prone to the aforementioned biases. Twinning has been suggested to be associated with an increased risk for autism spectrum disorder.29 30 Large epidemiological studies, including the results from this study, have found no or only a slight increase in the risk of autism spectrum disorder among twins.31 32 33 It is therefore unlikely that twinning explains the findings from this study. Finally, the comparison between the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden and the national patient register should take into account differences in age and follow-up time. Parents of twins born during 1993-95 were interviewed when the twins were 12 years old, and those born during 2000-02 only had 7-9 years of follow-up in the national patient register. As a consequence there was a seeming decrease in the annual prevalence of autism spectrum disorder for those born in 2000-02. However, when only including those who had been registered with a diagnosis in the national patient register before the age of 7 years, and thus having had exactly the same length of follow-up, a monotonic increase from 0.07% (1993) to 0.43% (2002, P<0.001) was observed.

Comparison with other studies

The prevalence of 0.95% (95% confidence interval 0.82% to 1.08%) for the autism symptom phenotype reported here should not be taken to be directly comparable to that of other epidemiological studies, given methodological differences in case ascertainment and assessment. However, there is accumulating evidence that the prevalence may have been historically underestimated in children. The prevalence of the autism symptom phenotype—that is, a triad of social, communication or language, and behavioural problems was already reported to be 0.7% in the early 1980s3 when a population based sample of children born in 1971 were assessed at early school age. Many of the children identified with this triad of difficulties were later shown to meet the—then newly formulated—criteria for Asperger syndrome,34 suggesting that the autism symptom phenotype may actually have been largely stable for the past three to four decades. Children with what currently would be labelled as autism spectrum disorder were in the past given other diagnoses or descriptions, including developmental language disorder35 and schizophrenia or psychotic behaviour36 37 as well as borderline personality disorder.38 These diagnostic substitutions probably reflect the zeitgeist in professional knowledge and the overlap in symptoms between disorders.

Even though it is not possible to completely rule out the effect of secular environmental changes related to the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder, the results indicate that their effect over the past decade may be marginal. This conclusion is supported by the results from two cross sectional studies employing a screening followed by clinical follow-up of children born in the same geographical area between 1992 and 199539 and 1996 and 1998,40 where no difference in prevalence over time was found. A recent study, using data from official registries from 1982-2006, found steady rates of relative recurrence risks in family members, irrespective of population prevalence.41 This argues against secular environmental factors of large impact.

Conclusions and policy implications

We believe that our findings indicate that the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder is not increasing in childhood. The research and clinical resources currently devoted to dealing with these problems relate to the possibly mistaken notion that there is an actual increase. This allocation of specific resources to study “the epidemic of autism” should not be allowed to spiral out of proportion. Other developmental disorders, such as intellectual developmental disorder, language disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder may recently have become overshadowed and seem to be missed diagnoses in many instances, where now only autism spectrum disorder is diagnosed (even perhaps when the autism symptomatology is relatively mild). There is growing evidence that these other developmental disorders are at least as good as or perhaps even better indicators of outcome (and hence, sometimes, need for intervention) as autism spectrum disorder in itself.42 Research and clinical practice need to refocus on the child’s overall clinical situation and to acknowledge that autism is but one of the many Early Symptomatic Syndromes Eliciting Neurodevelopmental Clinical Examinations (ESSENCE).43 Children who are clinically impaired at an early age and who meet the criteria for autism spectrum disorder almost always have other developmental disorders and problems that need to be tackled.44 Clinics specialising in autism spectrum disorder are unlikely to be able to cater to all the needs of affected children and their families.

What is already known on this topic

Numerous studies have suggested that the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder has increased substantially, and some recent studies have reported a population prevalence that exceeds 2%

Much of the prevalence increase can be explained by a broadening of the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder, although studies are biased by increased public and professional awareness, diagnostic substitution, and age at referral

Thus it is unclear if the increase in prevalence reflects an actual increase in the autism symptom phenotype

What this study adds

Our findings do not support a secular increase in the rate of the autism symptom phenotype

Administrative factors that affect the registered prevalence may therefore account for much of the increase in the reported prevalence of autism spectrum disorder

Contributors: SL, PL, and CG designed the study. SL performed all the analyses. SL and CG wrote the manuscript. HA, AR, and PL critically edited the manuscript. SL is guarantor of this work and had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: The Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden study was supported by the Swedish Council for Working Life, funds under the ALF agreement, the Söderström-Königska Foundation, and the Swedish Research Council (Medicine and SIMSAM). The current study received no specific funding. The funding sources had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the decision to submit this paper for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years, no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The data collection in the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden and the usage of the national patient register has ethical approval from the Karolinska Institutet ethical review board (Dnr 02-289 and 2010/507-31/1). No independent approval for any type of epidemiological study utilising this data is necessary.

Data sharing: The statistical code and datasets are available from the corresponding author at sebastian.lundström@gnc.gu.se.

Transparency: The lead author (SL) affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Cite this as: BMJ 2015;350:h1961

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Supplementary tables 1-4

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. APA, 2013.

- 2.Fombonne E. Epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr Res 2009;65:591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gillberg C. Perceptual, motor and attentional deficits in Swedish primary school children. Some child psychiatric aspects. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1983;24:377-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wing L, Potter D. The epidemiology of autistic spectrum disorders: is the prevalence rising? Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 2002;8:151-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wing L, Yeates SR, Brierley LM, et al. The prevalence of early childhood autism: comparison of administrative and epidemiological studies. Psychol Med 1976;6:89-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baird G, Simonoff E, Pickles A, et al. Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Lancet 2006;368:210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brugha TS, McManus S, Bankart J, et al. Epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders in adults in the community in England. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011;68:459-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YS, Leventhal BL, Koh YJ, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in a total population sample. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:904-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blumberg SJ, Bramlett MD, Kogan MD, et al. Changes in prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder in school-aged U.S. children: 2007 to 2011-2012. National health statistics reports. National Center for Health Statistics, 2013. [PubMed]

- 10.Idring S, Lundberg M, Sturm H, et al. Changes in prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in 2001-2011: findings from the Stockholm Youth Cohort. J Autism Dev Disord 2014; published online 5 Dec. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Hansen SN, Schendel DE, Parner ET. Explaining the increase in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorders: the proportion attributable to changes in reporting practices. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:56-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wazana A, Bresnahan M, Kline J. The autism epidemic: fact or artifact? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46:721-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coo H, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Lloyd JE, et al. Trends in autism prevalence: diagnostic substitution revisited. J Autism Dev Disord 2008;38:1036-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King M, Bearman P. Diagnostic change and the increased prevalence of autism. Int J Epidemiol 2009;38:1224-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shattuck PT. The contribution of diagnostic substitution to the growing administrative prevalence of autism in US special education. Pediatrics 2006;117:1028-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shattuck PT, Grosse S, Parish S, et al. Utilization of a Medicaid-funded intervention for children with autism. Psychiatr Serv 2009;60:549-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blenner S, Augustyn M. Is the prevalence of autism increasing in the United States? BMJ 2014;348:g3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anckarsater H, Lundstrom S, Kollberg L, et al. The Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden (CATSS). Twin Res Hum Genet 2011;14:495-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansson SL, Svanstrom Rojvall A, Rastam M, et al. Psychiatric telephone interview with parents for screening of childhood autism- tics, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and other comorbidities (A-TAC): preliminary reliability and validity. Br J Psychiatry 2005;187:262-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larson T, Kerekes N, Selinus EN, et al. Reliability of Autism-Tics, AD/HD, and other Comorbidities (A-TAC) inventory in a test-retest design. Psychol Rep 2014;114:93-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larson T, Anckarsater H, Gillberg C, et al. The autism-tics, AD/HD and other comorbidities inventory (A-TAC): further validation of a telephone interview for epidemiological research. BMC Psychiatry 2010;10:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson T, Lundstrom S, Nilsson T, et al. Predictive properties of the A-TAC inventory when screening for childhood-onset neurodevelopmental problems in a population-based sample. BMC Psychiatry 2013;13:233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cubo E, Saez Velasco S, Delgado Benito V, et al. [Psychometric attributes of the Spanish version of A-TAC screening scale for autism spectrum disorders]. An Pediatr (Barc) 2011;75:40-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. APA, 2000.

- 25.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, ninth revision (ICD-9). WHO, 1979.

- 27.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision (ICD-10). WHO, 1992.

- 28.Idring S, Rai D, Dal H, et al. Autism spectrum disorders in the Stockholm Youth Cohort: design, prevalence and validity. PLoS One 2012;7:e41280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Betancur C, Leboyer M, Gillberg C. Increased rate of twins among affected sibling pairs with autism. Am J Hum Genet 2002;70:1381-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenberg DA, Hodge SE, Sowinski J, et al. Excess of twins among affected sibling pairs with autism: implications for the etiology of autism. Am J Hum Genet 2001;69:1062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Croen LA, Grether JK, Selvin S. Descriptive epidemiology of autism in a California population: who is at risk? J Autism Dev Disord 2002;32:217-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hallmayer J, Glasson EJ, Bower C, et al. On the twin risk in autism. Am J Hum Genet 2002;71:941-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hultman CM, Sparen P, Cnattingius S. Perinatal risk factors for infantile autism. Epidemiology 2002;13:417-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillberg C, Steffenburg S, Schaumann H. Is autism more common now than ten years ago? Br J Psychiatry 1991;158:403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bishop DV, Whitehouse AJ, Watt HJ, et al. Autism and diagnostic substitution: evidence from a study of adults with a history of developmental language disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol 2008;50:341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perlman L. Adults with Asperger disorder misdiagnosed as schizophrenic. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2000;31:221-5. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unenge Hallerback M, Lugnegard T, et al. Is autism spectrum disorder common in schizophrenia? Psychiatry Res 2012;198:12-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petti TA, Vela RM. Borderline disorders of childhood: an overview. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1990;29:327-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chakrabarti S, Fombonne E. Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children. JAMA 2001;285:3093-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chakrabarti S, Fombonne E. Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children: confirmation of high prevalence. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1133-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandin S, Lichtenstein P, Kuja-Halkola R, et al. The familial risk of autism. JAMA 2014;311:1770-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gillberg C, Fernell E. Autism plus versus autism pure. J Autism Dev Disord 2014;44:3274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gillberg C. The ESSENCE in child psychiatry: Early Symptomatic Syndromes Eliciting Neurodevelopmental Clinical Examinations. Res Dev Disabil 2010;31:1543-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lundstrom S, Reichenberg A, Melke J, et al. Autism spectrum disorders and coexisting disorders in a nationwide Swedish twin study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014, published online 3 Oct. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables 1-4