Abstract

Objective

To compare a comprehensive lifestyle intervention for overweight children performed in groups of families with a conventional single-family treatment. Two-year follow-up data on anthropometric and psychological outcome are presented.

Design

Overweight and obese children aged 6–12 years with body mass index (BMI) corresponding to ≥27.5 kg/m2 in adults were randomised to multiple-family (n=48) or single-family intervention (n=49) in a parallel design. Multiple-family intervention comprised an inpatient programme with other families and a multidisciplinary team, follow-up visits in their hometown, weekly physical activity and a family camp. Single-family intervention included counselling by paediatric nurse, paediatric consultant and nutritionist at the hospital and follow-up by a community public health nurse. Primary outcome measures were change in BMI kg/m2 and BMI SD score after 2 years.

Results

BMI increased by 1.29 kg/m2 in the multiple-family intervention compared with 2.02 kg/m2 in the single-family intervention (p=0.075). BMI SD score decreased by 0.20 units in the multiple-family group and 0.08 units in the single-family intervention group (p=0.046). A between-group difference of 2.4 cm in waist circumference (p=0.038) was detected. Pooled data from both treatment groups showed a significant decrease in BMI SD score of 0.14 units and a significant decrease in parent-reported and self-reported Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire total score of 1.9 units.

Conclusions

Two-year outcome showed no between-group difference in BMI. A small between-group effect in BMI SD score and waist circumference favouring multiple-family intervention was detected. Pooled data showed an overall improvement in psychological outcome measures and BMI SD score.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Obesity, Child Psychology, Outcomes research, Comm Child Health, School Health

What is already known on this topic?

Childhood obesity represents a threat to children's health, and comprehensive treatment programmes can reduce the level of overweight 1 year from baseline.

There is a need for evidence of long-term effects of childhood obesity interventions to recommend cost-effective treatment strategies applicable for primary care.

Psychological consequences of obesity can be evident at young age, but few intervention studies report on vital psychological outcomes.

What this study adds?

Two-year outcome of a comprehensive multiple-family intervention did not show any advantageous effects in BMI change compared with a more conventional single-family approach.

A significant between-group effect in waist circumference in favour of the multiple-family approach was observed and needs further investigation.

Pooled data showed significant improvement in overweight and psychological outcome measures after completion of two generally applicable programmes performed in shared care.

Introduction

Obesity is a considerable threat to children's physical and mental health.1 2 Family-based lifestyle programmes focusing on nutrition, physical activity and behavioural change can reduce the level of overweight.3–5 Data on effectiveness of treatment programmes beyond 1 year are however limited. There is little high-quality evidence to recommend one treatment over another, and cost-effective programmes applicable to primary care have been requested.3 5 6 There is further a lack of data on psychological outcomes in intervention studies,3 and this trial aims to address some of these shortcomings.

Consequences of childhood obesity including risk factors of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease are well documented.1 Anxiety, depression and behavioural problems are the most frequently reported psychological symptoms among obese children and adolescents.2 7 8 Childhood obesity is also associated with reduced self-esteem and impaired quality of life.9–11 Weight-based stigmatisation and teasing as well as weight and shape concerns are suggested as mediators for how obesity affects psychological health.2 12 13 Parents participating in treatment for their child's obesity considered children's improved self-esteem and confidence a key outcome, even more important than weight change.14

The northernmost county of Norway, Finnmark, has a high prevalence of childhood obesity.15 Long travelling distances and limited hospital resources stimulated new treatment strategies for childhood obesity based on collaboration between specialised and primary health care, a shared care approach.16 Group-based management of childhood obesity may contribute to interaction between group facilitator and group members towards behavioural change and is considered cost effective.17 Group approach may also affect obese youngsters’ psychological health and is to our knowledge not well studied.

The objective of the Finnmark Activity School trial was to compare a new comprehensive multidisciplinary approach comprising meeting with other families in groups (multiple family intervention (MUFI)) with a more conventional single-family intervention (SIFI) with respect to primary outcome parameters (body mass index (BMI) kg/m2 and BMI SD score) and secondary outcome parameters (anthropometrical, physical activity, metabolic and psychological measures) in a randomised controlled trial (RCT). Methods are fully described in a previous paper.16 This paper presents 24 months’ anthropometrical and psychological outcomes of two treatment programmes for childhood obesity.

Materials and methods

Participants and settings

Altogether 97 overweight and obese children aged 6–12 years with BMI corresponding to ≥27.5 kg/m2 in adults (≥ the 98 centile according to the UK reference)16 18 19 were in 2009–2013 included in an RCT conducted at the Paediatric Department at Hammerfest Hospital. Participants were recruited through media coverage from six municipalities in Finnmark and Tromsø City. They were randomised to MUFI or SIFI in a parallel design. The trial is designed, conducted and reported in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines.20

Interventions

MUFI comprised a 3-day inpatient programme at the hospital with other families and a multidisciplinary team, individual and group-based follow-up visits in their hometown, weekly group-based physical activity and a 4-day family camp (table 1). SIFI comprised clinical examination and individual counselling by paediatric nurse, paediatric consultant, nutritionist at the hospital and follow-up by a local public health nurse.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the two intervention programmes of Finnmark Activity School

| Content of the intervention | Single-family intervention | Multiple-family intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Who is the target | Parents and child | Parents and child |

| Responsible for the intervention | Community and hospital | Community and hospital |

| Start | Outpatient clinic 1 day | Inpatient clinic stay for 3 days |

| Who delivers the intervention | Project nurse, paediatrician and nutritionist at the hospital. Public health nurse in the municipality | Multidisciplinary team at the hospital. Public health nurse, physiotherapist and coach in the municipality |

| How | Every family individually | Families both individually and in groups |

| Physical activity for children | Not arranged | 2 h a week in groups |

| Camp for families | No camp | 4 days 6–8 months from baseline |

| Solution-focused counselling | Yes | Yes |

| Follow-up intervals | 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 12, 18, 24 and 36 months | Equal intervals as the single-family group |

| Hours of contact first 12 months | 8 | 36 |

| Organised physical activity first 12 moths | 0 | 38 |

| Hours of contact 12–24 months | 2.5 | 6.5 |

| Organised physical activity 12–24 months | 0 | 38 |

Both intervention programmes focused on the families’ own resources and aimed to reduce sedentary activity, increase physical activity and increase the intake of healthy food according to national guidelines. Principles from Solution-Focused Brief Therapy, Standardized Obesity Family Therapy and elements from motivational interviewing were applied in both interventions.21–23

Outcomes and blinding

Prescheduled hospital visits at baseline and at 3, 12, 24 and 36 months of follow-up included anthropometric measurements, blood samples, bioelectrical impedance analysis and clinical examinations. Height, weight, waist circumference, skin fold thickness and body composition were measured as described previously.16 Nurses blinded to group allocation performed primary outcome measures. BMI kg/m2 was calculated and BMI SD score extracted from an obesity calculator based on British reference data.19 The following questionnaires were completed at baseline, after 6 months and at 12, 24 and 36 months’ follow-up: (1) the validated Norwegian version of Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) measured mental health.24 Teacher, parents and children ≥11 years of age completed the questionnaire. (2) The Norwegian version of Self-Perception Profile for Children (SPPC) was used to capture self-esteem.25 The questionnaire was completed by all children, with parents interviewing their smaller children. (3) The Norwegian version of the parent-reported and self-reported “Kinder Lebensqualitet Fragebogen” (KINDL) with separate forms for the 8–12 and 13–16 years age groups was used to measure quality of life.26

Sample size and statistical methods

The study was powered to detect a between-group difference in mean change of 0.5 kg/m2 BMI with SD of 0.8 from baseline to 2 years with two-sided α-level of 0.05 and 80% power. Differences between intervention groups at baseline were assessed by two-sample t test and Pearson's χ2 tests. All data were analysed by the intention-to-treat principle. Linear mixed models27 were used to compare time trends in BMI kg/m2 (and secondary anthropometrical outcomes) between the two groups over four time points. The independent variables were group, time (as three indicator variables) and cross-product terms between each indicator variable of time with group. A significant group-by-time interaction indicated different time trends between the intervention groups. In secondary analyses, we adjusted for random differences at baseline. All analyses were performed using Stata V.12.1 (StataCorp 4905 Lakeway Drive College Station, Texas, USA). Two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

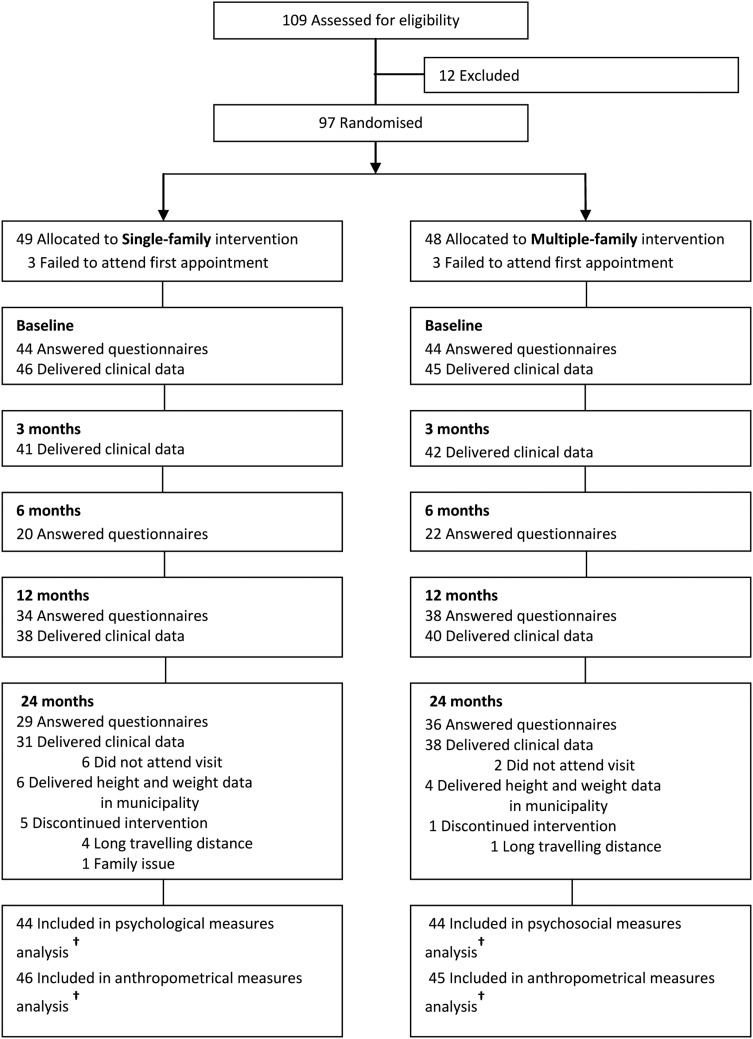

Figure 1 shows participant flow from recruitment to 24 months’ follow-up. Altogether 97 families were randomised and 91 children provided baseline data. Anthropometrical data after 24 months were collected from 69 children. Additionally, height/weight data from 10 children were reported from a local child healthcare centre, adding up to 81% retention for primary end points. No between-group differences in baseline variables were detected (table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants* through 24 months of treatment: Finnmark Activity School. *Siblings are not included in the analysis. †Longitudinal analyses include all available data from every subject through withdrawal or study completion.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of Finnmark Activity School

| Characteristics | Single-family intervention | Multiple-family intervention | Between-group p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 10.5±1.7 | 10.1±1.7 | 0.24 |

| Women/men | 22/24 | 27/18 | 0.24 |

| BMI kg/m2 | 27.6±4.3 | 26.9±4.2 | 0.42 |

| BMI SD score* | 2.81±0.60 | 2.76±0.58 | 0.70 |

| Obesity at baseline† | 36 (78) | 34 (76) | 0.76 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 89.2±11.9 | 87.9±12.0 | 0.62 |

| Waist to height ratio | 0.61±0.06 | 0.61±0.06 | 0.91 |

| Mother BMI kg/m2 (n) | 29.8±6.8 (43) | 29.9±8.1 (41) | 0.95 |

| Father BMI kg/m2 (n) | 29.5±4.3 (20) | 30.3±5.5 (21) | 0.63 |

| SDQ‡ total score self-report | 11.9±6.1 | 11.5±6.2 | 0.85 |

| SDQ total score parent report | 10.2±5.6 | 9.98±6.0 | 0.9 |

| SSPPC§ physical appearance | 2.6±0.9 | 2.6±0.7 | 0.97 |

| SPPC athletic competence | 2.4±0.7 | 2.5±0.6 | 0.68 |

| Quality of life self-report KINDL** | 70.2±13.8 | 70.4±10.3 | 0.94 |

| Quality of life parent-report KINDL | 72.1±10.8 | 70.7±9.3 | 0.53 |

| Proportion mothers with higher education level/n†† | 16 /42 (38) | 11/41 (27) | 0.2 |

| Proportion fathers with higher education level/n†† | 8/39 (21) | 10/40 (25) | 0.9 |

Baseline characteristics are presented as mean±SD for continuous variables and number (%) for binary variables.

*Body mass index SD score according to British reference.19

†Obesity according to Cole et al.18

‡Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire.24

§Self-Perception Profile for Children.25

**Kinder Lebensqualitet Fragebogen.26

††Academy, college, university education; ≥13 years of education.

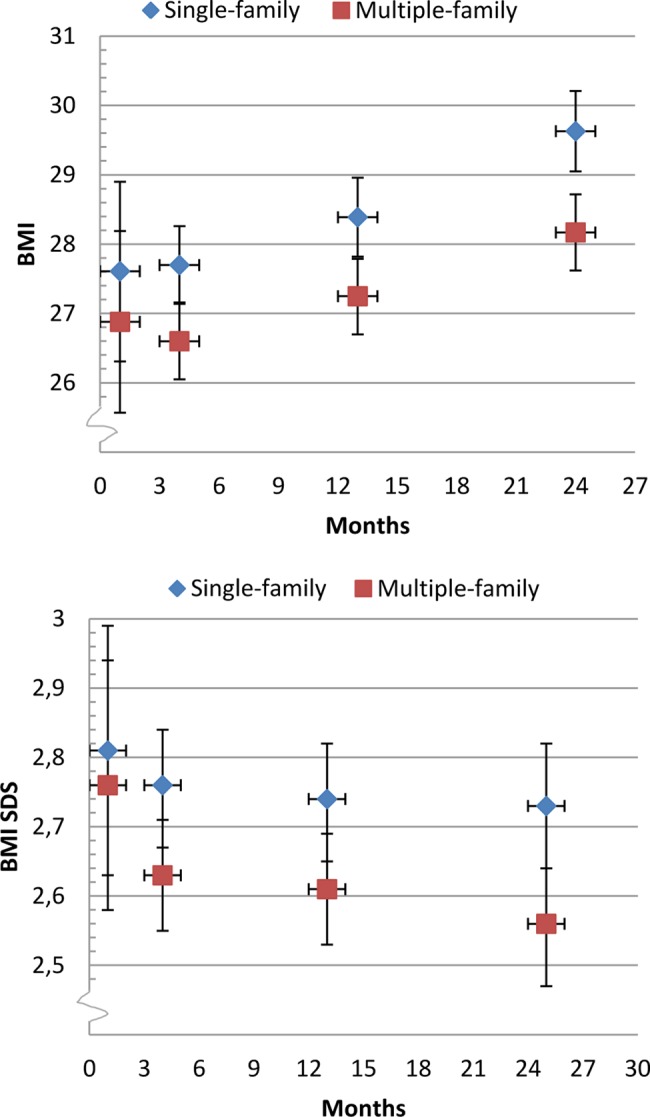

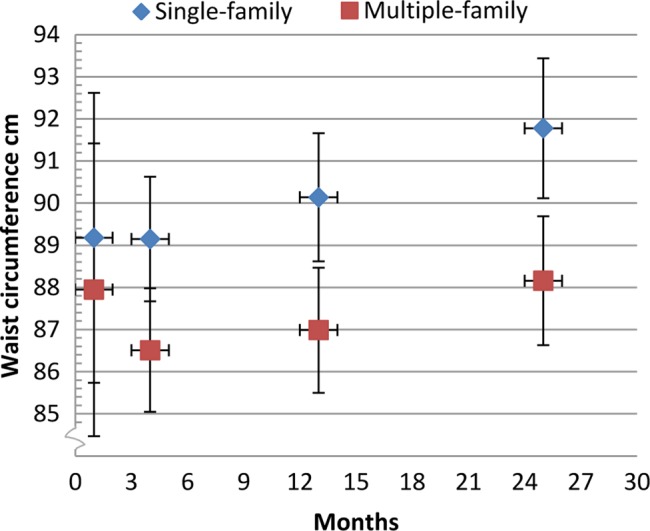

Anthropometrical outcome data are summarised in table 3. At 2 years’ follow-up, BMI had increased by 1.29 kg/m2 in the MUFI group and by 2.02 kg/m2 in the SIFI group, p=0.075. Mean decrease in BMI SD score was 0.20 units in the MUFI group and 0.08 units in the SIFI group (p=0.046) (figure 2). Waist circumference increased by 0.21 cm in the MUFI group and 2.60 cm in the SIFI group (p=0.038) (figure 3). Adjustment for baseline values did not affect the results for BMI SD score or waist circumference. Except for a small between-group difference in skin fold after 3 months, no difference was observed for skin fold or body fat measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis. Pooled data from both treatment groups showed a significant decrease in BMI SD score of 0.14 units.

Table 3.

Changes in BMI, BMI SD score and secondary anthropometrical outcomes through 24 months by treatment group of Finnmark Activity School

| Difference (95% CIs) at follow-up | Between-group difference | p Value* group by time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-family intervention | Multiple-family intervention | Koef (95% CI) | ||

| BMI (months) | ||||

| 3 | 0.09 (−0.47 to 0.65) | −0.28 (−0.83 to 0.28) | −0.37 (−1.15 to 0.42) | 0.358 |

| 12 | 0.78 (0.21 to 1.35) | 0.37 (−0.18 to 0.91) | −0.41 (−1.20 to 0.38) | 0.308 |

| 24 | 2.02 (1.44 to 2.60) | 1.29 (0.74 to 1.84) | −0.73 (−1.53 to 0.07) | 0.075 |

| BMI SDS† (months) | ||||

| 3 | −0.05 (−0.14 to 0.03) | −0.13 (−0.21 to −0.05) | −0.08 (−0.20 to 0.04) | 0.196 |

| 12 | −0.07 (−0.16 to 0.01) | −0.15 (−0.23 to −0.07) | −0.08 (−0.17 to 0.01) | 0.188 |

| 24 | −0.08 (−0.17 to 0.01) | −0.20 (−0.29 to −0.12) | −0.12 (−0.24 to 0.00) | 0.046 |

| Waist circumference (months) | ||||

| 3 | −0.03 (−1.51 to 1.45) | −1.44 (−2.90 to 0.03) | −1.41 (−3.49 to 0.67) | 0.184 |

| 12 | 0.96 (−0.56 to 2.48) | −0.96 (−2.45 to 0.52) | −1.92 (−4.05 to 0.20) | 0.076 |

| 24 | 2.60 (0.95 to 4.26) | 0.21 (−1.32 to 1.74) | −2.39 (−4.64 to −0.14) | 0.038 |

| Waist to height ratio (months) | ||||

| 3 | −0.01 (−0.02 to 0.00) | −0.02 (−0.03 to −0.01) | −0.01 (−0.02 to 0.00) | 0.194 |

| 12 | −0.02 (−0.03 to −0.01) | −0.03 (−0.04 to −0.02) | −0.01 (−0.03 to 0.00) | 0.057 |

| 24 | −0.03 (−0.04 to −0.02) | −0.04 (−0.05 to −0.03) | −0.02 (−0.03 to 0.00) | 0.029 |

| Skin fold (months) | ||||

| 3 | −1.5 (−2.4 to −0.6) | −3.00 (−3.91 to −2.20) | −1.5 (−2.8 to −0.3) | 0.013 |

| 12 | −4.0 (−4.9 to −3.1) | −4.5 (−5.38 to −3.63) | −0.5 (−1.8 to 0.7) | 0.404 |

| 24 | −6.2 (−7.1 to −5.2) | −6.5 (−7.43 to −5.64) | −0.4 (−1.7 to 0.9) | 0.577 |

| Body fat %‡ (months) | ||||

| 3 | 0.51 (−0.89 to 1.90) | −0.35 (−1.73 to 1.03) | −0.85 (−2.82 to 1.11) | 0.393 |

| 12 | 0.39 (−1.04 to 1.83) | −0.05 (−1.45 to 1.36) | −0.44 (−2.45 to 1.56) | 0.665 |

| 24 | 1.87 (0.31 to 3.42) | 0.76 (−0.67 to 2.19) | −1.11 (−3.22 to 1.01) | 0.304 |

| Pooled effects BMI SDS (months) | Both treatment groups pooled (95% KI) | p Value—change from baseline |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | −0.09 (−0.15 to −0.03) | 0.002 |

| 12 | −0.11 (−0.17 to −0.05) | 0.000 |

| 24 | −0.14 (−0.21 to −0.08) | 0.000 |

Data based on mixed models analysis with single-family intervention as reference group.

*p Value for equality between groups, group-by time effect.

†Body mass index SD score according to British reference.19

‡Body composition measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis.

Figure 2.

Body mass index (BMI) kg/m2 and BMI SD score: Finnmark Activity School. Mean (95% CI) changes in body mass index and BMI SD score from baseline to 24 months’ follow-up by intervention group.

Figure 3.

Waist circumference: Finnmark Activity School. Mean (95% CI) changes in waist circumference from baseline to 24 months’ follow-up by intervention group.

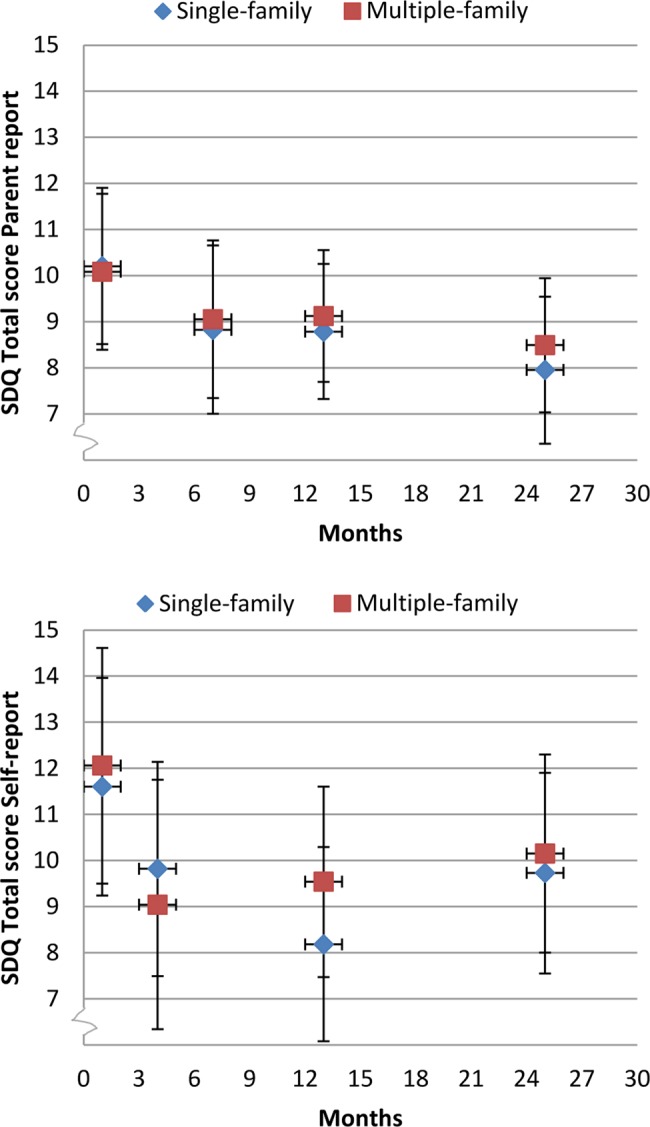

As shown in figure 4, there was no between-group difference in mental health as measured by SDQ from baseline to 24 months. However, pooled data from both intervention groups showed a significant decrease/improvement in parent-reported (n=89) and self-reported (n=66) total difficulty score of 1.9 units (95% KI −2.96 to −0.83, p=0.000 for parent, and 95% KI −3.41 to −0.37, p=0.015 for self-report) (see online supplementary tables A1 and A2, appendices), with significant improvement in the emotional symptoms and peer problem subscales (see online supplementary figures A1 and A2).

Figure 4.

Parent and self-reported mental health Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) total score: Finnmark Activity School. Mean (95% CI) changes in SDQ total score from baseline to 24 months’ follow-up by intervention group.

There was no difference in domain-specific and global self-worth subscales of self-perception between the two intervention groups (see online supplementary table A3). Pooled data from both intervention groups showed a significant improvement in athletic competence of 0.64 units (95% KI 0.48 to 0.80, p=0.000), social acceptance of 0.15 units (95% KI 0.02 to 0.29, p=0.029) and behavioural conduct of 0.16 units (95% KI 0.04 to 0.29, p=0.012) after 12 months. Notably though, only an increase in athletic competence of 0.5 units (95% KI 0.34 to 0.67, p=0.000) was sustained after 24 months (see online supplementary figure A3).

The parent-reported and self-reported quality of life data showed no difference between the intervention groups at any time point (see online supplementary table A4). Pooled data showed a significant increase in self-reported total score after 12 months of 3.39 units (95% KI 0.34 to 6.43, p=0.029) but improvement waned after 24 months. There was no overall change in parent-reported and self-reported total score of quality of life from baseline to 24 months.

Discussion

Two-year follow-up data from this child obesity trial showed no between-group difference in terms of BMI kg/m2 or psychological outcome measures. A small between-group effect in BMI SD score and waist circumference in favour of the MUFI intervention was observed. Pooled data from both intervention groups showed a significant decrease in parent-reported and self-reported SDQ problem scale and an increase in self-reported athletic competence as well as an overall decrease in BMI SD score.

Anthropometrical outcomes

Evidence of long-term effects in family-based treatment of childhood obesity was early observed by Epstein and colleagues.28 However, few recent randomised lifestyle interventions reported between-group difference in BMI or BMI SD score between new comprehensive approaches and control groups (conventional, self-help or no treatment),29 30 whereas other trials showed no between-group differences after 2 years.31 32 Authors evaluating obesity interventions have put forward social facilitation, increased contact and longer duration of treatment combined with a considerate reduction in adiposity during first months of intervention as approaches for improving long-term results.31 These elements are present in the current trial and might explain the modest between-group effects.

Mean treatment effect in the MUFI group did not reach ≥0.25 BMI SD score reduction, which is necessary to improve cardiovascular risk factors in obese adolescents according to a British study.33 Waist circumference is considered a good marker of visceral adipose tissue in children and is associated with cardiovascular risk factors.34 A significant between-group difference in waist circumference as seen in this trial may indicate a favourable development in risk profile.

The findings in this trial may be considered promising compared with other interventions performed in primary care.35 Explanation for the modest group effect might be the fairly high-intensive programme. A review evaluating interventions relevant for primary care pointed out in an association between hours of contact and treatment effect.6

On the other hand, the small improvement in the SIFI group (−0.08 in BMI SD score) in spite of very few hours of contact (8 h first year and 2.5 h second year) is interesting, and we might speculate that the shared care approach in both treatment arms based on collaboration between primary and specialised care has contributed to this finding.

Psychological outcomes

There were no between-group effects in measures of mental health and well-being in the current study. Two obesity trials involving group interventions with children and adolescents reported on improvement in self-esteem and quality of life in the intervention group compared with control.36 37 To the best of our knowledge, psychological outcomes in other group-based trials addressing childhood obesity are lacking.

Authors have raised the concern that too much focus on weight is not only ineffective in order to control obesity but could also have negative effects on mental health and well-being.38 We did not observe adverse effects in psychological outcomes in either intervention group after 2 years. Pooled data from both intervention groups showed an overall improvement in mental health rated by children and parents, as well as a significant improvement in self-reported athletic competence. This finding corresponds with reviews concluding that weight management programmes are not psychologically harmful in children.3 12

Only a few child obesity trials reported on mental health outcome while some studies reported on self-esteem and quality of life.36 37 An overall improvement in these parameters post-treatment was observed in most studies, but long-term effects beyond 1 year are lacking. We applied principles from solution-focused brief method, with non-claiming/neutral therapeutic position, assumptions of motivation and focus on solutions beyond problems.22 This may have contributed to improved provider/family interaction, stronger retention and favourable anthropometrical and psychological long-term results in both treatment groups.

Beneficial psychosocial effect of physical activity is thoroughly documented.39 Provided that the participating children managed to increase their activity levels, this favourable change may have affected their mental health and well-being. The self-reported improvement in athletic competence could imply such a mechanism.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the randomised design, blinding of the primary outcome assessors, sample size determined from power calculation achieved, appropriate statistical methods including intention-to-treat analysis and linear mixed models applied, moderate withdrawal and reporting according to CONSORT guidelines. In addition, an appropriate pilot study was performed.

Limitations include a lower study power than anticipated because of a larger variability in BMI than expected. The pragmatic inclusion criterion corresponding to adult BMI ≥27.5 kg/m2 and the fact that nurses measuring waist circumference were not blinded to group allocation were discussed previously.16

The primary outcome parameter BMI SD score has limitations related to evaluation of treatment trials. Different reference populations for the calculation of BMI SD score make comparisons between studies challenging, and variability of BMI SD score depends on the child's level of adiposity.40

Performing a clinical trial in small municipalities is challenging because of high risk of contamination between treatment groups. SIFI and MUFI appointments were scheduled at different days to minimise contact between groups, but causal meetings between families were inevitable. Due to the small municipalities and shortage of personnel, the same providers were employed in both treatment arms. As a consequence, the outreached guidance and courses for providers reached the SIFI as well as the MUFI groups. This strategy might have attenuated group differences.

In order to assess the natural course of adiposity and psychological outcome in obese children, a true control group would be optimal. However, it is for ethical reasons impossible in long-term studies to randomise obese children to ‘no intervention’ or a waiting list.

Implications

The modest difference between the two treatment groups after 2 years raises the question whether the cost of the MUFI approach can be justified. The between-group effect in waist circumference and effect on cardiovascular risk factors need further investigation.

The overall significant decrease in BMI SD score in both groups suggests that increased awareness and minimal support is sufficient to succeed with lifestyle changes for some families. Future studies should examine subgroup effects. Obesity interventions in children and adolescents should examine health in broad perspective and evaluate mental health and well-being in addition to other health outcomes. The current shared care model can be applicable to other regions and settings.

Conclusion

Two-year results from this trial showed no between-group difference for BMI or psychological outcomes. There was a significant between-group difference in waist circumference in favour of the MUFI approach. Pooled results from both treatment arms showed a significant improvement in parent-reported and self-reported mental health combined with a significant decrease in BMI SD score of 0.14.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participating families, and primary and secondary health care personnel involved in the Finnmark Activity School trial. We also want to thank the families participating in the pilot project, Professor Lars Bo Andersen, University of Southern Denmark, Professor John A Rønning, University of Tromsø, participants in the early Activity School Reference Group, representatives from Finnmark County Authority, County Governor of Finnmark and Finnmark Sport Council, who all contributed with valuable support in the development of this project. We also thank Professor Tom Wilsgaard for advice and quality assurance of the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Contributors: AK designed the study, conducted the study, analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the original manuscript. SG designed the study, involved in conducting the study, data interpretation and edited the manuscript. SS analysed psychological outcome measures, interpreted data and edited the manuscript. TF designed the study and was involved in conducting the study, data interpretation and edited the manuscript. IN designed the study and was involved in conducting the study, interpretation of data and editing the manuscript in addition to statistical advices. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The trial has been supported by Finnmark Hospital Trust, Northern Norway Regional Health Authority, Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation and The Norwegian Directorate of Health. Contributions have also been made by the University of Tromsø, the Ministry of Health and Care Services, SpareBank 1 Nord-Norge and Odd Berg Fund.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Region North. The families gave written informed consent signed by parents and all children ≥12 years.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Reilly JJ. Descriptive epidemiology and health consequences of childhood obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;19:327–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell-Mayhew S, McVey G, Bardick A, et al. . Mental health, wellness, and childhood overweight/obesity. J Obes 2012;2012:281801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, et al. . Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(1):CD001872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canoy D, Bundred P. Obesity in children. Clin Evid (Online) 2011;2011:pii:0325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho M, Garnett SP, Baur L, et al. . Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in child obesity: systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2012;130:e1647–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitlock EP, O'Connor EA, Williams SB, et al. . Effectiveness of weight management interventions in children: a targeted systematic review for the USPSTF. Pediatrics 2010;125:e396–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vila G, Zipper E, Dabbas M, et al. . Mental disorders in obese children and adolescents. Psychosom Med 2004;66:387–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD. Psychiatric comorbidity of childhood obesity. Int Rev Psychiatry 2012;24:241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffiths LJ, Parsons TJ, Hill AJ. Self-esteem and quality of life in obese children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Obes 2010;5:282–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hughes AR, Farewell K, Harris D, et al. . Quality of life in a clinical sample of obese children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:39–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schwimmer JB, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life of severely obese children and adolescents. JAMA 2003;289:1813–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wardle J, Cooke L. The impact of obesity on psychological well-being. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;19:421–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harriger JA, Thompson JK. Psychological consequences of obesity: weight bias and body image in overweight and obese youth. Int Rev Psychiatry 2012;24:247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart L, Chapple J, Hughes AR, et al. . Parents’ journey through treatment for their child's obesity: a qualitative study. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kokkvoll A, Jeppesen E, Juliusson PB, et al. . High prevalence of overweight and obesity among 6-year-old children in Finnmark County, North Norway. Acta Paediatr 2012;101:924–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kokkvoll A, Grimsgaard S, Odegaard R, et al. . Single versus multiple-family intervention in childhood overweight—Finnmark Activity School: a randomised trial. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:225–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nowicka P, Savoye M, Fisher PA. Which psychological method is most effective for group treatment? Int J Pediatr Obes 2011;6(Suppl 1):70–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, et al. . Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000;320:1240–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA. Body mass index reference curves for the UK, 1990. Arch Dis Child 1995;73:25–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. . CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Shazer S, Berg IK, Lipchik E, et al. . Brief therapy: focused solution development. Fam Process 1986;25:207–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nowicka P, Flodmark CE. Family therapy as a model for treating childhood obesity: useful tools for clinicians. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2011;16:129–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behav Cogn Psychother 2009;37:129–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronning JA, Handegaard BH, Sourander A, et al. . The Strengths and Difficulties Self-Report Questionnaire as a screening instrument in Norwegian community samples. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;13:73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wichstrom L. Harter's Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents: reliability, validity, and evaluation of the question format. J Pers Assess 1995;65:100–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jozefiak T, Larsson B, Wichstrom L, et al. . Quality of Life as reported by school children and their parents: a cross-sectional survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Twisk JW, de Vente W. The analysis of randomised controlled trial data with more than one follow-up measurement. A comparison between different approaches. Eur J Epidemiol 2008;23:655–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, et al. . Ten-year outcomes of behavioral family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Health Psychol 1994;13:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang JX, Xia XL, Greiner T, et al. . A two year family based behaviour treatment for obese children. Arch Dis Child 2005;90:1235–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Savoye M, Nowicka P, Shaw M, et al. . Long-term results of an obesity program in an ethnically diverse pediatric population. Pediatrics 2011;127:402–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalavainen M, Korppi M, Nuutinen O. Long-term efficacy of group-based treatment for childhood obesity compared with routinely given individual counselling. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:530–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hystad HT, Steinsbekk S, Odegard R, et al. . A randomised study on the effectiveness of therapist-led v. self-help parental intervention for treating childhood obesity. Br J Nutr 2013;110:1143–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ford AL, Hunt LP, Cooper A, et al. . What reduction in BMI SDS is required in obese adolescents to improve body composition and cardiometabolic health? Arch Dis Child 2010;95:256–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarthy HD. Body fat measurements in children as predictors for the metabolic syndrome: focus on waist circumference. Proc Nutr Soc 2006; 65:385–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wake M, Baur LA, Gerner B, et al. . Outcomes and costs of primary care surveillance and intervention for overweight or obese children: the LEAP 2 randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;339:b3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sacher PM, Kolotourou M, Chadwick PM, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of the MEND program: a family-based community intervention for childhood obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(Suppl 1):S62–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofsteenge GH, Weijs PJ, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, et al. . Effect of the Go4it multidisciplinary group treatment for obese adolescents on health related quality of life: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2013;13:939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bacon L, Aphramor L. Weight science: evaluating the evidence for a paradigm shift. Nutr J 2011;10:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eime RM, Young JA, Harvey JT, et al. . A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013;10:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cole TJ, Faith MS, Pietrobelli A, et al. . What is the best measure of adiposity change in growing children: BMI, BMI %, BMI z-score or BMI centile? Eur J Clin Nutr 2005;59:419–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.