Abstract

Objectives

Aspirin is an important part of primary cardiovascular disease prevention, but little is known about aspirin use patterns in regional healthcare systems. This study used electronic health records from the Marshfield Clinic to identify demographic, geographic, and clinical predictors of aspirin utilization in central Wisconsin adults without cardiovascular disease.

Methods

A cross-sectional design was employed using 2010-2012 data from patients in the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area. Individuals who took aspirin-containing medication daily or every other day were considered regular aspirin users. There were a total of 6,678 adults in the target region who were clinically indicated for aspirin therapy for primary cardiovascular disease prevention, per national guidelines.

Results

Aspirin was generally underutilized in this population, with 35% of all clinically indicated adults taking it regularly. Adjusted models found that individuals who were younger, female, not covered by health insurance, did not visit a medical provider regularly, smokers, were not obese, or did not have diabetes were least likely to take aspirin. In addition, there was some local variation in that aspirin use was less common in northeastern communities within the regional service area.

Conclusion

Several aspirin use disparities were identified in central Wisconsin adults without cardiovascular disease, with particularly low utilization observed in those without diabetes and/or without regular physician contact. Methods of using electronic health records to conduct primary care surveillance as outlined here can be adopted by other large healthcare systems in the state to optimize future cardiovascular disease prevention initiatives.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the principle driver of mortality in the United States.1

Despite steady reductions in both incidence and mortality2 over recent decades, the overall prevalence of CVD is expected to rise due to an aging population and increased diabetes comordities.3 Without further reductions in new CVD cases, the healthcare resources required to manage CVD are feared to outstrip financial capacity. CVD preventive medical care focuses on risk factor modification, namely control of elevated blood pressure and lipids.4 Control of platelet aggregation via low-dose aspirin is also important for those at high risk of experiencing a CVD event.5, 6 Though aspirin therapy for primary CVD prevention remains controversial,7, 8 meta-analytic evidence suggests that it lowers CVD risk by nearly 15% over seven years.9

Aspirin use has been increasing in the U.S. overall,10, 11 with at least 41% of all U.S. adults over age 40 now taking it regularly.12 Aspirin is routinely recommended and well utilized in Wisconsin's secondary prevention population with active CVD,13 but pharmacoepidemiologic research on aspirin use in primary CVD prevention populations is much less common. The most recent statewide research found that about one third of Wisconsin adults age 35-74 years without CVD or diabetes are clinically indicated for aspirin therapy and, of these, just 31% report taking aspirin regularly.14 Consistent with other previous research, Wisconsinites in older age groups are most likely to use aspirin.

State and national level studies are helpful in detecting broad trends in aspirin utilization, but they are less relevant at local levels where targeted health initiatives are more likely to occur. The recent widespread adoption of electronic health records (EHR) by large healthcare delivery systems presents opportunities to ‘reuse’ clinical data for community-level epidemiologic research. There are at least some burgeoning EHR models that can inform regional CVD risk factor surveillance and pharmacoepidemiology,15-17 but none have specifically examined aspirin at a population level. In order to help regional healthcare systems leverage their ‘own’ data to direct primary care initiatives toward patients most likely to benefit, this is an important research gap to address. The purpose of this study was to characterize regular aspirin use in central Wisconsin adults without CVD (who are clinically indicated for aspirin), as well as to identify regional demographic and clinical disparities in aspirin use.

Methods

Design and setting

A cross-sectional analysis was performed using data extracted from the Marshfield Clinic research data warehouse, which stores medical and administrative information captured within the system EHR during clinical encounters. The target population was the central portion of the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area (i.e., MESA). As described in more detail elsewhere,18 MESA is a regional population-based health research resource that includes patients (and their associated family members) who received care from Marshfield Clinic and reside in one of the ZIP codes that surround primary service area in central Wisconsin. This region is predominantly rural, covering over 1,000 square miles, with about 56,000 total residents who receive over 90% of their inpatient and outpatient healthcare from the Marshfield Clinic.19

Sample

All data were collected over a 3-year timeframe between 01/01/2010 and 12/31/2012. Eligibility criteria for this analysis were, as of December 31, 2012: (1) current living status in MESA Central, (2) ≥1 ambulatory encounter with a Marshfield Clinic medical provider during the study timeframe, (3) no personal history of ischemic vascular disease (i.e., myocardial infarction, angina, ischemic stroke – specific diagnostic codes available upon request), and (4) clinically indicated for aspirin therapy for primary CVD prevention, per the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)6 and, for those with diabetes, the American Diabetes Association (ADA)20 guidelines as detailed below. Because this was a retrospective analysis of existing healthcare data, the study was approved by the Marshfield Clinic Institutional Review Board with a waiver of informed consent.

Indication for aspirin therapy

The clinical indication for aspirin therapy for primary CVD prevention was determined for all subjects based on current USPSTF6 and ADA20 guidelines. Among patients without diabetes, those indicated for aspirin included men in the following age-risk categories for coronary heart disease: 45–59 years and ≥4% risk, 60–69 years and ≥9% risk, and 70–79 years and ≥12% risk. And also women in the following age-risk categories for stroke: 55–59 years and ≥3% risk, 60–69 years and ≥8% risk, and 70–79 years and ≥11% risk. For patients with diabetes, men and women with ≥10% risk of CVD are indicated for aspirin therapy. Assuming no contraindications, the USPSTF and ADA recommends aspirin in these groups because the probability of cardioprotection outweighs that of major gastrointestinal or intracranial hemorrhage. A 10-year risk of CVD, coronary heart disease, or stroke was calculated for each individual using the global CVD risk equation from the Framingham Heart Study.21 This method estimates the risk of all CVD using information on age, sex, smoking, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and diabetes. The global CVD risk score can then be multiplied by a correction factor to determine the specific 10-year risk for coronary heart disease (for men without diabetes) and stroke (for women without diabetes). Those with a known aspirin contraindication are not indicated for aspirin therapy under the USPSTF and ADA guidelines. Comprehensive assessment of aspirin contraindications using administrative data is not well established, however, because clinical judgment is often needed to determine the severity of a given health condition in this context. As such, only select aspirin contraindicative diagnostic codes were screened for in the EHR based on previous recommendations.22, 23 These included a previous history of a salicylate adverse events, gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial bleeding, or severe liver disease. Other, more relative potential contraindications such as concurrent use of anticoagulants or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), poorly controlled hypertension, and/or gastroesophogeal reflux, were not considered in this study.

Measures

Outcome

Based on previous state level methods developed for standard healthcare quality reporting,13, 22 the primary outcome was regular use of aspirin-containing medication. Known initiation/discontinuation dates, dose, and frequency of all patient reported medications were collected in patient interviews conducted as part of the routine workflow during Marshfield Clinic encounters, and stored in the system EHR. There are no known objective validation studies of EHR-derived aspirin use, but one previous study found strong agreement between manual chart-audited and EHR-automated text derived aspirin use in adults with diabetes.16 Another study showed strong agreement between self-reported regular aspirin use and a blood byproduct of salicylates.24

In this study, EHR-derived medications were first linked to the therapeutic classification system of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists.25 All salicylate class medications were reviewed and the generic names of aspirin-containing medications screened for during data extraction, including: ASPIRIN, ASPIRIN/CALCIUM CARB, ASPIRIN/MAGNESIUM CARB/AL AMINOACET, ASPIRIN/MAGNESIUM HYDROX/AL HYDROX, and ASPIRIN/CALCIUM CARB/MAGNESIUM/AL HYDROX. Per standard practice,22 combined aspirin-narcotic medications (e.g., aspirin plus codeine) were not considered due to the transient nature of such therapies. Also, other prescription antiplatelet agents such as Clopidogrel were not considered as they are typically reserved only for secondary CVD prevention. Individuals who took aspirin-containing medication daily or every other day at their most recent encounter within the study timeframe were considered current regular aspirin users. Participants who did not take (or discontinued) aspirin at their most recent encounter, took aspirin pro re nata, or otherwise took aspirin less frequently than every other day were considered irregular aspirin users. Aspirin dose was reported descriptively where available, but could not be considered in the outcome definition due to incomplete data.

Exposures

Several exposures were considered to identify the best independent predictors of regular aspirin use. These included age, sex, race/ethnicity, health insurance status, residential community, number of ambulatory care encounters over the previous three years, smoking, body mass index (BMI), and diabetes. Community was based on the ZIP code of residence within MESA. BMI was calculated as weight in kg divided by height in meters squared. Diabetes was established by the presence of ≥2 diagnostic code in 250.xxx occurring before 12/31/2012. All clinical variables were collected by trained staff following standard Marshfield Clinic office-based physical exam and laboratory procedures.

Analyses

All analytical procedures were conducted with SAS Version 9.3 (Cary, NC). For individuals with missing total or HDL cholesterol, the 10-year CVD risk estimate was calculated using BMI in place of blood lipids, per methods outlined by D'Agostino and colleagues.21 This method provides a reasonable approximation of CVD risk in the absence of laboratory values. Univariate and multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the association between all exposures and regular aspirin use. An initial multicollinearity check between exposures found no issues, thus all exposures were considered simultaneously in a fully adjusted model. Given the exploratory nature of this analysis, no model reduction techniques were applied. Also, because there is near complete capture of medical care data within the target MESA population, no sample weighting techniques were used.

Results

There were 6,678 individuals identified as clinically indicated for aspirin therapy and meeting all study eligibility criteria. Descriptive characteristics of the analytical sample are outlined in Table 1. As expected, the sample was predominantly male and non-Hispanic White, with the majority residing in the Marshfield community. There were 2,346 (35%) individuals who took aspirin regularly. Among regular aspirin users, 98% indicated daily use. Full aspirin dose information was only available on 530 aspirin users, with an average daily dose of 81 mg being most common (77%), followed by ≥325 mg (21%) and 162 mg (2%).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of central Wisconsin adults who were clinically indicated for aspirin therapy for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in 2012, stratified by regular aspirin use.

| Characteristics | Regular aspirin use n=2,346 | Irregular or no aspirin use n=4,332 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 61.6 ±8.5 | 56.5 ±8.0 | <0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 339 (14%) | 364 (8%) | <0.001 |

| Male | 2,007 (86%) | 3,968 (92%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 2,253 (96%) | 4,078 (94%) | 0.001 |

| Non-White, non-Hispanic | 35 (1%) | 64 (1%) | |

| Hispanic | 26 (1%) | 73 (2%) | |

| Unknown | 32 (1%) | 117 (3%) | |

| Health insurance | |||

| Commercial only | 1,456 (62%) | 3,022 (70%) | <0.001 |

| Public assisted | 828 (35%) | 1,042 (24%) | |

| None | 62 (3%) | 268 (6%) | |

| Residential community (ZIP code) | |||

| Dorchester | 52 (2%) | 121 (3%) | 0.097 |

| Abbotsford | 108 (5%) | 200 (5%) | |

| Colby | 113 (5%) | 238 (5%) | |

| Stratford | 202 (9%) | 434 (10%) | |

| Unity | 62 (3%) | 79 (2%) | |

| Spencer | 172 (7%) | 303 (7%) | |

| Hewitt | 45 (2%) | 73 (2%) | |

| Auburndale | 96 (4%) | 207 (5%) | |

| Arpin | 78 (3%) | 166 (4%) | |

| Milladore | 50 (2%) | 81 (2%) | |

| Chili | 45 (2%) | 100 (2%) | |

| Pittsville | 133 (6%) | 217 (5%) | |

| Marshfield | 1,190 (51%) | 2,113 (49%) | |

| Number of ambulatory visits in past 3 years | 12.4 ±9.8 | 9.0 ±8.4 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | |||

| Current | 336 (14%) | 1,000 (23%) | <0.001 |

| Former | 930 (40%) | 1,322 (31%) | |

| Never | 1,080 (46%) | 2,010 (46%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 32.4 ±6.7 | 30.9 ±6.4 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | |||

| Yes | 755 (32%) | 559 (13%) | <0.001 |

| No | 1,591 (68%) | 3,773 (87%) | |

All values are reported as mean ±standard deviation or frequency (% of total). P-value corresponds to the difference between the two groups.

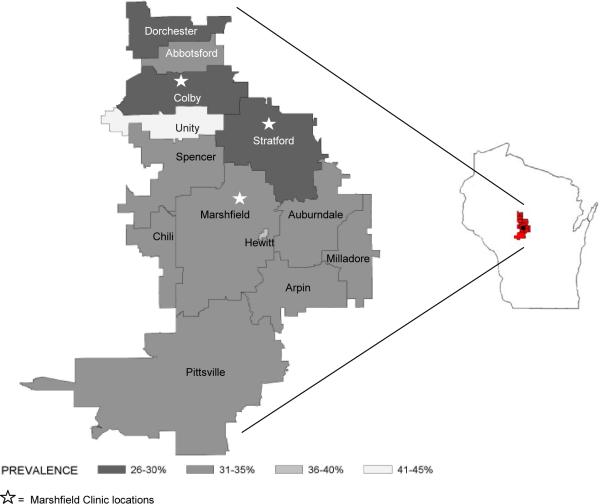

All exposures except residential community were significantly associated with aspirin use in unadjusted models (see Table 1). As described in Table 2, the fully adjusted multivariable model found that adults who were older, male, commercially insured, visited a medical provider regularly, were non-smokers, had a higher BMI, or had diabetes had a significantly higher odds of aspirin use. Residential community was modestly associated with aspirin use (see Figure 1). After adjustment for other exposures, rates of aspirin utilization by community ranged from a low of 29% in Dorchester to a high of 45% in Unity. A sensitivity analysis was also conducted using residential census tract (in lieu of ZIP code) in order to view local variation at a more granular level. Parameter estimates from this analysis were very similar to those observed in the main findings (results not shown).

Table 2.

Multivariable association between patient exposures and regular aspirin use among central Wisconsin adults who were clinically indicated for aspirin therapy for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (n=6,678).

| Exposures | Regular aspirin use (yes vs. no) |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 1.07 (1.06, 1.08) p<0.001 |

| Sex | |

| Female vs. male | 0.56 (0.45, 0.68) p<0.001 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Non-White, non-Hispanic vs. White, non-Hispanic | 1.26 (0.81, 1.97) p=0.307 |

| Hispanic vs. White, non-Hispanic | 0.72 (0.44, 1.17) p=0.185 |

| Unknown vs. White, non-Hispanic | 0.73 (0.48, 1.11) p=0.142 |

| Health insurance | |

| Publicly insured vs. commercially insured | 0.72 (0.63, 0.83) p<0.001 |

| Not insured vs. commercially insured | 0.62 (0.46, 0.83) p=0.001 |

| Residential community | |

| Dorchester vs. Marshfield | 0.77 (0.54, 1.11) p=0.168 |

| Abbotsford vs. Marshfield | 0.88 (0.68, 1.15) p=0.345 |

| Colby vs. Marshfield | 0.85 (0.66, 1.09) p=0.200 |

| Stratford vs. Marshfield | 0.85 (0.70, 1.04) p=0.109 |

| Unity vs. Marshfield | 1.55 (1.08, 2.23) p=0.018 |

| Spencer vs. Marshfield | 1.01 (0.81, 1.25) p=0.952 |

| Hewitt vs. Marshfield | 1.19 (0.80, 1.78) p=0.395 |

| Auburndale vs. Marshfield | 0.86 (0.66, 1.13) p=0.277 |

| Arpin vs. Marshfield | 0.93 (0.69, 1.25) p=0.625 |

| Milladore vs. Marshfield | 1.00 (0.68, 1.48) p=0.982 |

| Chili vs. Marshfield | 0.91 (0.62, 1.33) p=0.628 |

| Pittsville vs. Marshfield | 1.03 (0.81, 1.32) p=0.812 |

| Number of ambulatory visits in past 3 years | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) p<0.001 |

| Smoking | |

| Current vs. former or never | 0.80 (0.69, 0.93) p=0.003 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) p<0.001 |

| Diabetes | |

| Yes vs. no | 2.41 (2.05, 2.82) p<0.001 |

Values are reported as odds ratio (95% confidence interval) of regular aspirin use. Values less than 1 indicate that as the exposure variable increased (or relative to the reference category for categorical exposures), the odds of aspirin use decreased.

Figure 1.

Regular aspirin use among adults clinically indicated for aspirin for primary cardiovascular disease prevention, stratified by residential community within the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area.

Discussion

Aspirin is underutilized in central Wisconsin, with 35% of adults that are clinically indicated to take it for primary CVD prevention actually doing so. Adjusted models found that patients who were younger, female, not covered by health insurance, did not visit a medical provider regularly, smokers, were not obese, or did not have diabetes were least likely to take aspirin. Race had limited influence on aspirin use, unlike one other study.11 Otherwise demographic patterns of aspirin use in this study were largely consistent with other previous findings,10-12 with the overall rate of aspirin use in this study area slightly higher than that observed statewide in 2008-2010.14

Clinical factors were notably strong markers of aspirin use in this study. In particular, adults with diabetes had a 2.4 times greater odds of taking aspirin relative to those without. In addition, those with private health insurance and who visited the clinic frequently were much more apt to take aspirin. Taken collectively, such factors underscore previous observations that, according to patients, a physician conversation where aspirin is recommended is the most motivating factor for taking aspirin regularly.12 It seems logical to conclude that patients who are clinically identified as being in poor health (e.g., diabetes, obese) and have reasonable access to and utilization of healthcare (e.g., insured, regular physician visits) are more likely to receive such medical advice relative to healthy young adults or those without health insurance who cannot visit the clinic often.

There was also a modest degree of local variation in that several communities north and east of the main Marshfield Clinic campus were least likely to take aspirin. Reasons for this were unclear and did not obviously track with socioeconomic factors. U.S. Census data indicate that education and income levels, as well as professional-oriented occupations, predictably drop in all directions further away from the population center of Marshfield. Distance from medical care also did not appear to be a strong factor as has been observed in some previous regional research on care for other health conditions.26 In addition to the main central clinic in Marshfield, there are two satellite clinics that deliver primary care in the northern communities, which serve the lowest aspirin use areas. This may present opportunities to focus specific primary care outreach efforts in those locations in order to improve rates of aspirin use across MESA.

Measurement bias was the main study limitation in that aspirin use was reported during patient interviews as part of usual care and precise dosage information was often lacking, presumably because it could not be recalled by patients. Validation studies are scarce on self-reported aspirin use, but indicate generally good accuracy and correlation with biomarkers.24 The timing of the aspirin assessment at the most recent visit may also be an unstable marker of long-term regular aspirin use for some patients who may only be temporarily using aspirin regularly. More objective and longitudinal sources of medication possession (e.g., pharmacy claims) might help augment gaps in self-reported medication use. Despite the general advantages of EHR data in epidemiologic research, more subjective elements of the medical chart are often difficult to query, including direct physician advice to take aspirin, clinical judgments on some potential aspirin contraindications, and patients’ primary intent of regular aspirin use (e.g., CVD prevention, pain management). Future research would benefit from advancing methods to readily account for this information. Other limitations were the limited racial diversity of the source population relative to other parts of the country, or more urban areas of the state.

This study is the first EHR-based examination of the pharmacoepidemiology of aspirin use for primary CVD prevention in the region. Several aspirin disparities were identified, which may help inform a ‘profile’ of where and for whom future primary CVD care quality improvement initiatives (e.g., academic detailing, clinical decision aids) could be optimally targeted. As EHRs become ubiquitous, primary CVD prevention surveillance methods outlined here could be further refined and adopted by other large healthcare systems, including those with geographically extensive service areas commonly found in Wisconsin and throughout the rural Midwest.27 As part of the coming wave of American healthcare reforms, all healthcare systems will, in addition to providing high quality care for sick patients, experience mounting expectations to monitor and improve the health of the entire populations they serve.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This project was supported by the Marshfield Clinic Celine Seubert Distinguished Physician Endowment in Cardiology Research, as well as the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR000427. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures

The authors have no conflicting financial interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2013 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in US deaths from coronary disease, 1980-2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933–944. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820a55f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu S, Ton VK, Dominique Ashen M, et al. A clinician's guide to the ABCs of cardiovascular disease prevention: The Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Heart Disease and American College of Cardiology Cardiosource approach to the Million Hearts Initiative. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:383–393. doi: 10.1002/clc.22137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hennekens CH, Schneider WR. The need for wider and appropriate utilization of aspirin and statins in the treatment and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6:95–107. doi: 10.1586/14779072.6.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Aspirin for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:396–404. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnett H, Burrill P, Iheanacho I. Don't use aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. BMJ. 2010;340:c1805. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Food and Drug Administration [05/23/2014];Use of Aspirin for Primary Prevention of Heart Attack and Stroke. Available at: www.fda.gov/drugs/resourcesforyou/consumers/ucm390574.htm.

- 9.Bartolucci AA, Tendera M, Howard G. Meta-analysis of multiple primary prevention trials of cardiovascular events using aspirin. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1796–1801. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.02.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ajani UA, Ford ES, Greenland KJ, Giles WH, Mokdad AH. Aspirin use among U.S. adults: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:74–77. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez DR, Diez Roux AV, Michos ED, et al. Comparison of the racial/ethnic prevalence of regular aspirin use for the primary prevention of coronary heart disease from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pignone M, Anderson GK, Binns K, Tilson HH, Weisman SM. Aspirin use among adults aged 40 and older in the United States: Results of a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality [07/08/2013];Ischemic Vascular Disease: Daily Aspirin or Other Antiplatelet Therapy. Available at: www.wchq.org/reporting/results.php?category_id=0&topic_id=27&source_id=0&providerType=0®ion=0&measure_id=156.

- 14.VanWormer JJ, Greenlee RT, McBride PE, et al. Aspirin for primary prevention of CVD: Are the right people using it? J Fam Pract. 2012;61:525–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.VanWormer JJ. Methods of using the electronic health record for population level surveillance of coronary heart disease risk in the Heart of New Ulm project. Diabetes Spectrum. 2010;23:161–165. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pakhomov SV, Shah ND, Hanson P, Balasubramaniam SC, Smith SA. Automated processing of electronic medical records is a reliable method of determining aspirin use in populations at risk for cardiovascular events. Inform Prim Care. 2010;18:125–133. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v18i2.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Persell SD, Dunne AP, Lloyd-Jones DM, Baker DW. Electronic health record-based cardiac risk assessment and identification of unmet preventive needs. Med Care. 2009;47:418–424. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818dce21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeStefano F, Eaker ED, Broste SK, et al. Epidemiologic research in an integrated regional medical care system: The Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;4:643–652. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00008-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenlee RT. Measuring disease frequency in the Marshfield Epidemiologic Study Area (MESA). Clin Med Res. 2003;1:273–280. doi: 10.3121/cmr.1.4.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pignone M, Alberts MJ, Colwell JA, et al. Aspirin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in people with diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association, a scientific statement of the American Heart Association, and an expert consensus document of the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1395–1402. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D'Agostino RB, Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minnesota Community Measurement. Optimal Vascular Care [07/02/2013];Data Collection Guide. 2013 Available at: http://mncm.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Optimal_Vascular_Care_DDS_2013_FINAL_11_27_2012.pdf.

- 23.Miser WF. Appropriate aspirin use for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:1380–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zantek ND, Luepker RV, Duval S, et al. Confirmation of reported aspirin use in community studies: Utility of serum thromboxane B2 measurement. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2014;20:385–392. doi: 10.1177/1076029613486537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists . AHFS Drug Information 2013. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; Bethesda, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onitilo AA, Miskowiak D, Broton M, et al. Geographical access to mammography services and stage of breast cancer at initial diagnosis in Wisconsin.. Poster session presented at: Annual HMO Research Network Conference; San Francisco, CA. 2013 Apr 16. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gabbert JP, Trine RM, Bintz M. Improving a regional outreach program in a large health system using geographic information systems. WMJ. 2012;111:134–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]