Abstract

Prohibitins are members of a highly conserved protein family containing the stomatin/prohibitin/flotillin/HflK/C (SPFH) domain (also known as the prohibitin [PHB] domain) found in unicellular eukaryotes, fungi, plants, animals, and humans. Two highly homologous members of prohibitins expressed in eukaryotes are prohibitin (PHB; B-cell receptor associated protein-32, BAP-32) and prohibitin 2/repressor of estrogen receptor activity (PHB2, REA, BAP-37). Both PHB and REA/PHB2 are ubiquitously expressed and are present in multiple cellular compartments including the mitochondria, nucleus, and the plasma membrane. Multiple functions have been attributed to the mitochondrial and nuclear PHB and PHB2/REA including cellular differentiation, anti-proliferation, and morphogenesis. One of the major functions of the prohibitins are in maintaining the functional integrity of the mitochondria and protecting cells from various stresses. In the present review, we focus on the recent research developments indicating that PHB and PHB2/REA are involved in maintaining cellular survival through the Ras-Raf-MEK-Erk pathway. Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which the intracellular signaling pathways utilize prohibitins in governing cellular survival is likely to result in development of therapeutic strategies to overcome various human pathological disorders such as diabetes, obesity, neurological diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, and cancer.

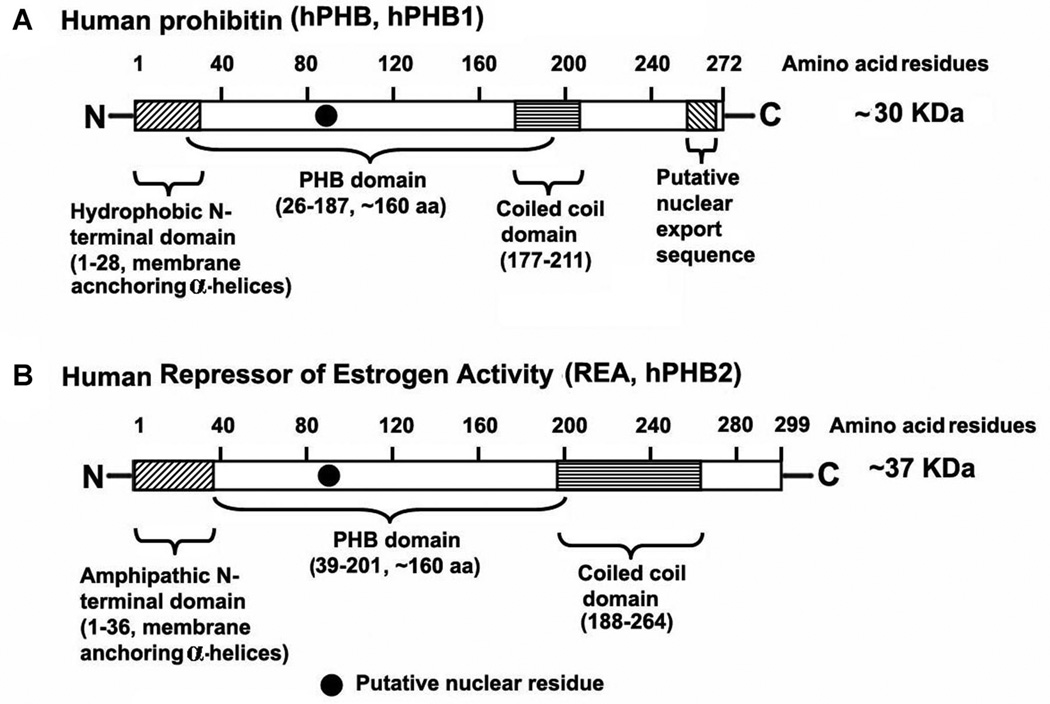

Prohibitins are members of an extensive evolutionarily conserved family of proteins which includes stomatins, plasma membrane proteins of Escherichia coli (HflKC), flotillins, the human insulin receptor (HIR) proteins and plant defense proteins (Nadimpalli et al., 2000). The two highly homologous members of prohibitins expressed in eukaryotes are prohibitin (PHB; B-cell receptor associated protein-32, BAP-32) and prohibitin 2/repressor of estrogen receptor activity (PHB2, REA, BAP-37). Although, initially associated with inhibition of cell proliferation (hence the name “prohibitin”), PHB and REA appear to have an increasing array of functional cellular roles that include cellular differentiation, anti-proliferation, and morphogenesis (Chowdhury et al., 2012). Prohibitins are composed of an N-terminal transmembrane domain consisting of a hydrophobic membrane-anchoring alpha helix, an evolutionarily conserved PHB domain that is common to several other scaffold proteins (including stomatin, flotillin, and HflK/C; and called SPFH domain) and are important for lipid raft associations and protein–protein interactions; and a C-terminal coiled-coil domain that is involved in protein–protein interactions between PHB and REA. In humans, the PHB gene (hPhb) maps to chromosome 17q21.1 and spans ~11 kb with 7 exons (Sato et al., 1992). The human and rodent Phb genes are similar except for introns 2 and 3, which are ~1 kb larger in the rat gene (Altus et al., 1995). The human and rodent Phb gene encode ~30 kDa proteins that have a single amino acid difference (Fig. 1) (Chowdhury et al., 2012). The human Phb2 gene (Terashima et al., 1994; He et al., 2008) is located on chromosome 12p13 (Ansari-Lari et al., 1997) and spans ~5.3 kb with 10 exons, have smaller introns than Phb, and codes a protein of ~37 kDa (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Schematic domain representation of human prohibitin 1 (hPHB1) and human repressor of estrogen activity (REA/hPHB2) proteins. N, amino terminal; C, carboxylic terminal.

The PHB and REA proteins are 54% homologous in amino acid sequence (Chowdhury et al., 2012) and are found to be associated a high molecular weight regulatory complex (Nuell et al., 1991; Montano et al., 1999; Steglich et al., 1999; Martini et al., 2000; Nijtmans et al., 2000, 2002; Wang et al., 2002; Kurtev et al., 2004) (Fig. 1). Orthologues of the prohibitin gene have been identified in several organisms including bacteria (Edman and Sogin, 1994; Narasimhan et al., 1997; de Monbrison and Picot, 2002), plants (Snedden and Fromm, 1997; Takahashi et al., 2003), Trypanosoma brucei (Welburn and Murphy, 1998), yeast (Berger and Yaffe, 1998; Kirchman et al., 2003; Tatsuta et al., 2005), and Drosophila (Eveleth and Marsh, 1986). While studies have shown that PHB and REA null yeast strains have reduced lifespan, it appears that null mutations are lethal in higher eukaryotes which are more dependent upon expression of their Phb and Phb2/REA genes, suggesting they are involved in enhanced biological functions. The Phb orthologues in Drosophila are essential for normal development and differentiation during larvae to pupae metamorphosis (Eveleth and Marsh, 1986). Genetic deletion of the Phb and Phb2/REA genes in mice are lethal before embryonic day 6.5, however, heterozygous mice show no appreciable defects in fertility (Park et al., 2005), implying that these proteins play a critical role in the early stages of development in vertebrates. A number of diverse cellular functions have also been attributed to both PHB and REA in different cellular compartments. These include roles in cell cycle progression, the regulation of transcription, cellular differentiation, and in cell surface signaling (Chowdhury et al., 2012; Mishra et al., 2006; Thuaud et al., 2013). Extensive and rapidly accumulating evidence suggests that both prohibitins function primarily within mitochondria (Chowdhury et al., 2007, 2011, 2012, 2013; Artal-Sanz and Tavernarakis, 2009; Merkwirth and Langer, 2009). Here we review the evidence indicating that the prohibitins regulate cellular survival through interactions with the Ras-Raf-MEK-Erk pathway.

Prohibitins Localization in Mitochondria

PHB and REA are present in multiple cellular compartments including mitochondria and nucleus, suggesting that they play additional roles to the chaperone proteins that are present in these compartments (Nijtmans et al., 2000, 2002; Chowdhury et al., 2012), and by their ability to target to lipid rafts. In the nucleus, both PHB and REA can modulate transcriptional activity by interacting with various transcription factors, either directly or through their interactions with chromatin remodeling proteins (Montano et al., 1999; Wang et al., 1999, 2002; Martini et al., 2000; Kurtev et al., 2004). Both PHB and REA are highly expressed in cells that depends heavily on mitochondrial function, including neurons, muscle, heart, liver, renal tubules, adrenal cortex, adipocytes, pancreatic islet cells, testis, and ovary (Thuaud et al., 2013) suggesting a strong supportive role in metabolically active cells. Similarly, both PHB and REA are expressed at higher levels in mammalian proliferating cells, including neoplastic tissues (Czarnecka et al., 2006) and granulosa cells (Chowdhury et al., unpublished work; Thompson et al., 2004). In the mitochondrial inner membrane (IM) both PHB and REA are associated to form a macromolecular structure of approximately 1 MDa. This high molecular weight complex has been identified in yeast, Caenorhabditis elegans and mammals (Steglich et al., 1999; Nijtmans et al., 2000; Artal-Sanz et al., 2003). Both PHB and REA bind to each other to form a heterodimeric building block (Back et al., 2002). About 12 to 16 prohibitin heterodimers then associate to form a ring-like structure at the mitochondrial IM (Back et al., 2002) with a diameter of 20–25 nm (Tatsuta et al., 2005). This prohibitin complex is anchored in the mitochondrial IM through N-terminal hydrophobic regions present in both PHB and REA. Although PHB is considered to be membrane-associated (Back et al., 2002), the homologous helical region at the N-terminus of PHB is shorter and is not likely to fulfill the requirements for a membrane-spanning domain. Furthermore, complex formation depends on both PHB and REA subunits, since depletion of either PHB or REA results in the absence of the complex, indicating interdependence at the level of protein complex formation (Artal-Sanz et al., 2003; He et al., 2008; Merkwirth et al., 2008; Chowdhury et al., 2012). Interestingly, prohibitin homodimers have not been detected (Tatsuta et al., 2005) and detailed high resolution structural studies are still lacking.

Prohibitin and Mitochondrial Dynamics

Subcellular fractionation studies of rat ovarian granulosa cells (GCs) preformed in our laboratory followed by two-dimensional (2-D) Western blot analyses showed that PHB is present as two isoforms (Thompson et al., 1997, 1999, 2001, 2004). In the mitochondrial fraction, two PHB 30-kDa protein spots were detected with isoelectric points of 5.6 and 5.8, whereas only one 30-kDa protein spot with an isoelectric point of 5.8 was observed in the nuclear fraction (Thompson et al., 1997, 2001, 2004). These studies suggested that phosphorylation of PHB played a significant role in mitochondria.

Mitochondria play critical role(s) in cell physiology and are highly dynamic structures that fuse continuously and divide to adjust the shape and distribution of the mitochondrial network depending on cell type and their energy demands. Conserved protein complexes located in the outer and inner membrane of mitochondria regulating fusion and fission events and include several dynamin-like GTPases (Detmer and Chan, 2007 Chowdhury and Bhat, 2010). Among these, mitofusins (Mfn1, Mfn2) and optic atrophy 1 protein (OPA1) are required for mitochondrial fusion, and dynamin-related protein (DRP1) is required for mitochondrial fission.

Studies have shown that abnormal mitochondria accumulate in the nematode C. elegans after RNA-interference (RNAi)-mediated depletion of prohibitins (Artal-Sanz et al., 2003). Lack of cristae were observed in plant mitochondrial depleted of prohibitins (Ahn et al., 2006). In normal muscle cells, mitochondria appear tubular, elongated, and well-structured, running parallel to the body axis and often to the myofibrils, however, upon prohibitin depletion, mitochondria appear fragmented and disorganized (Artal-Sanz et al., 2003). A similar observation was made in prohibitin-deficient yeast cells (Berger and Yaffe, 1998; Matikainen et al., 2001; Osman et al., 2009). In mammalian cells (HeLa cells or GCs) RNAi-mediated knockdown of either PHB orREA/PHB2 expression resulted in fragmentation of the mitochondrial network (Kasashima et al., 2006; Chowdhury et al., 2013). In addition, fragmented mitochondria were also observed in prohibitin-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs), suggesting that fusion of mitochondrial membranes are impaired in the absence of prohibitins (Merkwirth et al., 2008; Chowdhury et al., 2013). Furthermore, prohibitins are required for cristae morphogenesis, as revealed by an ultrastructural analysis of mitochondria in prohibitin-deficient MEFs (Merkwirth et al., 2008). Disrupted cristae morphology most likely facilitates the release of cytochrome c from the intracristal space, thereby explaining the increased sensitivity of prohibitin-deficient MEFs or GCs to apoptotic stimuli. Ross et al. (2008) have demonstrated that both PHB and PHB2/REA are up-regulated during T cell activation and functions to maintain mitochondrial integrity and regulate T cell activation, differentiation, viability, and function.

The aberrant mitochondrial morphology observed in the absence of prohibitins can be explained by an altered processing of OPA1 (Merkwirth et al., 2008), a large dynamin-like GTPase found in the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS) that regulates both mitochondrial fusion and cristae morphogenesis (Hoppins et al., 2007). Studies have shown that mutations in OPA1 gene cause degeneration of retinal ganglion cells in autosomal dominant optic atrophy (Alexander et al., 2000; Delettre et al., 2000). Furthermore, proteolytic processing of OPA1 splice variants, which are expressed in a tissue-specific manner (Delettre et al., 2001; Akepati et al., 2008), results in the accumulation of long and short OPA1 isoforms (two long isoforms, L-OPA1; and three short isoforms, S-OPA1) (Delettre et al., 2001; Satoh et al., 2003; Ishihara et al., 2006). Normal mitochondrial fusion depends on expression of both long and short OPA1 isoforms (Satoh et al., 2003; Ishihara et al., 2006). Indeed, ectopic expression of a non-cleavable long OPA1 isoform was able to restore tubular mitochondrial network, cristae morphogenesis, and apoptotic resistance in Phb2−/− MEFs (Merkwirth et al., 2008). Similar results were found in GCs when PHB was depleted or the cells were treated with PKC inhibitor staurosporine (STS) (Chowdhury et al., 2013). Moreover, the mitochondrial fragmentation and highly disorganized cristae of PHB2-depleted MEFs strikingly resembles the mitochondrial morphology observed after OPA1 down-regulation (Griparic et al., 2004; Merkwirth et al., 2008).

Recent studies have also shown that ablation of PHB2/REA in mouse β-cells sequentially resulted in impairment of mitochondrial function and insulin secretion, loss of β-cells, progressive alteration of glucose homeostasis, and, ultimately, severe diabetes (Supale et al., 2013). At the molecular level, deletion of PHB2/REA caused mitochondrial abnormalities, including reduction of mitochondrial DNA copy number and respiratory chain complex IV levels, altered mitochondrial activity, cleavage of L-optic atrophy 1, and mitochondrial fragmentation (Supale et al., 2013). Collectively, these experiments confirm that functional interactions occurring between OPA1 and prohibitins are most likely the key events that govern the stabilization of mitochondria.

Several additional published studies have supported the notion that prohibitins participate in mitochondrial dynamics through interaction with other membrane proteins. A mitochondrial stomatin-like protein (SLP-2/Stoml2) has been shown to interact with prohibitins in the mitochondrial IM (Da Cruz et al., 2008). Stomatins contain an erythrocyte band-7 motif and belong to the SPFH family of proteins (Tavernarakis et al., 1999). Depleting HeLa cells of SLP-2 results in increased proteolysis of PHB, PHB2/REA, and subunits of respiratory chain complexes I and IV. The stability of prohibitins upon mitochondrial stress partially depends on SLP-2 (Da Cruz et al., 2008), and PHB expression was shown to increase following mitochondrial stress (Nijtmans et al., 2000, 2002; Coates et al., 2001; Artal-Sanz et al., 2003; Chowdhury et al., 2007, 2011, 2013). Recent studies have also shown that the major domains of the Mfns are orientated toward the cytoplasm, and interact indirectly with Mfns and OPA1 at the mitochondrial IM through associations with SLP-2/Stoml2 and/or prohibitins (Hájek et al., 2007; Guillery et al., 2008; Ichishita et al., 2008).

Prohibitins Role in Cellular Survival and Cytoprotection

A major function of the prohibitins is to protect cells from various stresses including oxidative stress (Jones, 2008). These stresses are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and are an important component of the etiology of cancers, diabetes mellitus, inflammatory, cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases, and reproductive dysfunction. Studies have demonstrated that during oxidative stress both PHB and REA/PHB2 are up-regulated to promote cell survival. PHB expression is enhanced in neurons by various stressors, including electrical stimulation, hypoxia ischemia, oxygen–glucose deprivation (Zhou et al., 2012), exercise-induced neuroplasticity (Ding et al., 2006), injection of the neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine (Park et al., 2010), and schizophrenia-induced oligodendrocyte dysfunction (Bernstein et al., 2012). PHB is also up-regulated in the liver of steatohepatitis patients (Tsutsumi et al., 2009), in fetal rabbit lung after exposure to hyperoxic conditions (Henschke et al., 2006), in pancreatic β-cells after ethanol intoxication (Lee et al., 2010a), and in cardiac cells after ischemic–hypoxic preconditioning (Kim et al., 2006; Muraguchi et al., 2010) or chronic restraint stress (Liu et al., 2004). This cytoprotective response involves the translocation of PHB from the nucleus and the cytoplasm to mitochondria in pancreatic β-cells (Lee et al., 2010a), in the retina and retinal epithelium (Lee et al., 2010a), and in ovarian GCs (Chowdhury et al., 2007, 2011, 2013; Wang et al., 2013). Sripathi et al. (2011) suggested that the localization and trafficking of PHBs are determined by the modulation of their binding activities to specific lipids. Indeed, strong binding of PHB to cardiolipin was shown to correlate with the localization of PHB within mitochondria in transformed epithelial cells after an oxidative stress. In contrast, under normal conditions in these cells, PHB binds strongly to PIP3 but not to cardiolipin. Over-expression of PHB protects pancreatic β-cells, ovarian GCs, and cardiomyocytes from apoptosis induced by ethanol, ceramide, staurosporine, serum withdrawal, and oxidative stress-induced injury, and is consistent with PHB having a cytoprotective role (Chowdhury et al., 2007, 2011; Liu et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2010b; Wang et al., 2013).

A wide range of studies performed in cancer cells also demonstrated that increased expression of PHB supports cellular survival (Wu et al., 2007; Gregory-Bass et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2008; Ummanni et al., 2008; Patel et al., 2010). However, no consensus currently exists on the functional role of PHB in cancer cells. In A549 lung cancer cells, increased expression of surface-PHB prevents the apoptosis of these cancer cells and renders them more resistant to paclitaxel (Patel et al., 2010). Although, PHB is required for cancer-cell proliferation, over-expression of PHB inhibits growth of breast-cancer and androgen-dependent prostate cancer cells (Peng et al., 2006; Dart et al., 2009; Sievers et al., 2010).

In support of cytoprotective role of PHB, interleukin-6 (IL-6) has shown to increase PHB levels through phosphorylation of the transcription factor STAT3 that subsequently promoted the survival of intestinal cells and cardiomyocytes (Theiss et al., 2007, 2009; Gratia et al., 2012). In intestinal epithelial cells in vivo, PHB interacts with STAT3 to modulate STAT3-mediated apoptosis (Kathiria et al., 2012). In cardiomyocytes, IL-6-induced up-regulation of PHB is central to the cardioprotective effects of IL-6 against oxidative stress (Theiss et al., 2009; Gratia et al., 2012). Importantly, phosphorylated STAT3 protects cardiomyocytes against oxidative stress by stimulating respiration and inhibiting the PTP within mitochondria, but not through a transcriptional effect (Boengler et al., 2010).

In contrast to PHB, detail studies on cytoprotective role of REA/PHB2 are lacking. Recent studies by Merkwirth et al. (2012) have shown that REA/PHB2 also plays critical role in the survival of neurons. Neuron-specific deletion of REA/PHB2 in the mouse forebrain impaired mitochondrial architecture, leading to tau hyperphosphorylation and filament formation. This phenotype was accompanied by severe behavioral and cognitive dysfunctions that were reminiscent of Alzheimer’s disease (Merkwirth et al., 2012). The molecular details of the mechanisms of this cytoprotection remain to be further investigated. The only other cellular components that have been identified as being involved are S1P and STAT3. S1P protects the heart from ischemia-reperfusion damage by directly activating PHB2, thereby regulating respiration and cytochrome oxidase subunit IV assembly and decreasing the heart’s susceptibility to opening of the permeability transition pore (PTP; Gomez et al., 2011). Published studies by Supale et al. (2013) have also suggested that PHB2/REA is essential for metabolic activation of mitochondria and, as a consequence, for function and survival of β-cells.

Anti-Apoptotic Role of Prohibitins Through BCL Family of Proteins

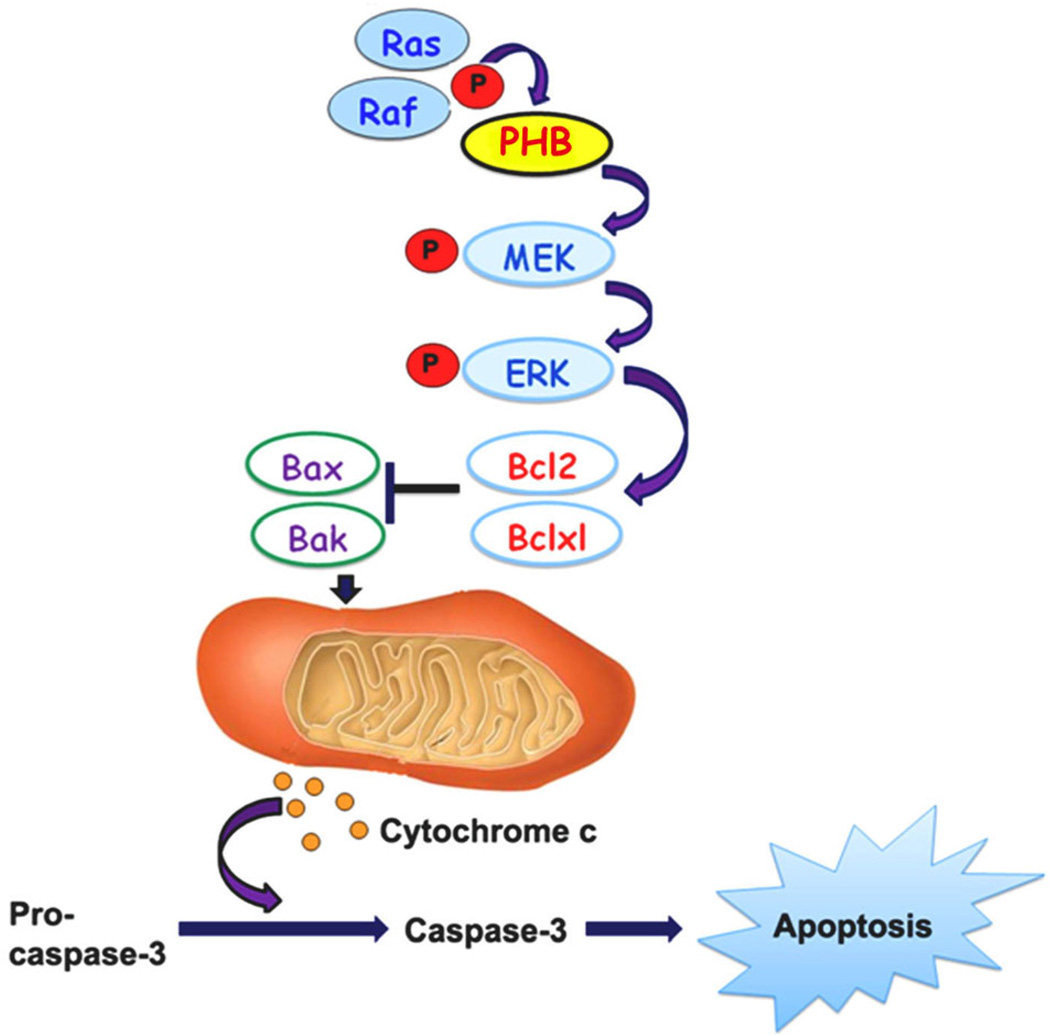

In general, two partly interdependent routes lead to apoptosis. One of them is initiated by ligation of the death receptors at the cell surface in the so-called extrinsic pathway, the other one is induced by DNA damage or endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress leading to apoptosis by the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria is called intrinsic pathway (Chowdhury et al., 2006). In the intrinsic pathway, the three distinct mitochondrial compartments (the intermembrane space or IMS, intracristal space, and matrix are defined by the three membrane systems namely, outer, inner boundary, and cristae) that are separate but are functionally involved in the apoptotic process. In response to apoptotic cues, the apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) along with other key pro-apoptotic factors such as cytochrome c, SMAC/DIABLO (Second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase/Direct IAP-binding protein with low pI) and Omi from the IMS elicits a cascade of events in the cytosol that lead to the activation of intracellular proteases of the caspase family and eventually, and loss of mitochondrial function with self-digestion of the cell (Chowdhury et al., 2006, 2008). A decisive role in this process is played by the mitochondrial PTP which initiates Bax/Bak-mediated mitochondrial outer-membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and cristae remodeling (Chowdhury and Bhat, 2010). From our studies (Chowdhury et al., 2007, 2011, 2013) it appears that the action of PHB in GCs is dependent on the stage of differentiation. For instance, infection of undifferentiated GCs isolated from preantral follicles with a Phb adenoviral construct resulted in over-expression of PHB that markedly attenuated ceramide-, staurosporine (STS)-, campothecine-, and serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis via the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Chowdhury et al., 2007, 2011, 2013). Furthermore, we confirmed that over-expression of PHB maintained the mitochondrial transmembrane potential by inhibiting cytochrome c release and activation of caspase-3 (Chowdhury et al., 2007, 2011, 2013) (Fig. 2). Similar results have also been shown by Wang et al. (2013). Studies by Zhou et al. (2012) have indicated that less expression of PHB is associated with increased caspase-3 expression/cell apoptosis in renal interstitial fibrosis (RIF) rats, a hallmark of common progressive chronic diseases that lead to renal failure. Other studies in mice have shown that lower level of expression of PHB promotes apoptosis through cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2)-mediated pathway during inflammation (Kim et al., 2009).

Fig. 2.

A schematic model showing the protective mechanisms of PHB/PHB1 against staurosporine (STS)-induced apoptosis in granulosa cells (GCs). STS induces up-regulation of Bax and Bak with inhibition of Bcl2 and Bcl-xl, leading to alteration in the permeability of mitochondria as reflected by release of mitochondrial cytochrome c, which causes activation of caspase-3, and eventually execution of the apoptotic program. PHB/PHB1 blocks up-regulation of Bax and Bak through up-regulation of pErK, Bcl2 and Bclxl, and consequently suppresses downstream apoptotic events by preventing the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c and activation of caspases-3.

In addition, studies performed by our group have shown that over-expression of PHB in undifferentiated GCs isolated from preantral follicle delayed accelerated apoptosis by enhancing the transcription and translation of anti-apoptotic genes (Bcl2, Bclxl) in STS-treated GCs (Chowdhury et al., 2006, 2013). The apoptosis-preventing effect of Bcl2 and Bclxl are counteracted by the proapoptotic protein Bax and Bak (Chowdhury et al., 2013) (Fig. 2). An imbalance of the Bax and Bak versus Bcl2 and Bclxl ratios tilts the scales toward cell death and sensitized cells to a wide variety of cell death stimuli. However, ectopic PHB over-expression in GCs prevented apoptosis triggered by apoptotic stimuli, thereby supporting the role of the Bax/Bcl2, Bax/Bclxl, Bak/Bcl2, and Bak/Bclxl as key checkpoint rheostat (Chowdhury et al., 2013). Anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL) or pro-apoptotic (Bax, Bak) Bcl2 proteins are the prototype of a large family of proteins (more than 30 members), which share a high degree of homology although they exert different functions in the apoptotic pathway (Chowdhury and Bhat, 2010). In healthy cells, Bax and Bak are mainly located in the cytosol as monomers with a minor pool loosely attached to mitochondria. Apoptotic stimuli induces structural changes in Bax and Bak which oligomerize in the OMM to result in MOMP formation and the release of inter-membrane space proteins including cytochrome c. In contrast, the anti-apoptotic Bcl2 and Bclxl proteins are able to neutralize pro-apoptotic proteins and thus inhibit Bax/Bak activity and MOMP formation. Our molecular studies that were designed to elucidate the mechanisms involved in this regulatory process suggest that upon induction of apoptosis by STS, mitochondrial PHB through phosphorylated PHB (phospho-PHB, pPHB) mediate activation of pMEK–pERK expression. This result in enhancement of the Bcl/Bcl-xL pathway and inhibition of Bax-Bak directly by inhibiting the release of cytochrome c from the inter-mitochondrial space and inhibition of the downstream activation of cleaved caspase 3 (Chowdhury et al., 2013). A similar observation was made in hypoxia by Muraguchi et al. (2010). These investigators showed that over-expression of PHB inhibited a decrease of mitochondrial membrane potential levels, resulting in decreased Bcl-2 levels in mitochondria and cytochrome c release to cytosol from mitochondria induced by hypoxia. Studies have also shown that PHB induces apoptosis in cells with DNA damage during inflammation through inhibition of STAT3-induced Bcl-xL and Bcl-2 and induction of p53 signaling via activation of Bax and PUMA (Kathiria et al., 2012). Reduced PHB expression in inflamed tissues is likely to make genetically compromised intestinal epithelial cells more resistant to cell death, thereby promoting tumorigenesis (Kathiria et al., 2012). These studies suggest that PHB is likely to be a key factor in cell survival pathway acting through the Bcl family of proteins. However, similar detailed molecular studies on REA/PHB2 in relation to cellular survival are lacking.

Prohibitins Phosphorylation and Ras-Raf-MEK-Erk Pathway

The experimental evidence in support of the relationship between prohibitin phosphorylation and activation of the Ras-Raf-MEK-Erk pathway in cellular survival has been provided by other research groups including ours. Our original experimental observation in 1997 suggested that PHB is phosphorylated in GCs under in vitro physiological conditions. However, detailed studies to determine how PHB phosphorylation is regulated in these cells have been performed recently (Thompson et al., 1997; Chowdhury et al., 2007, 2013). These studies have shown that when GCs are cultured in presence of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) plus testosterone (T) (our unpublished work) or PKC inhibitor staurosporine (STS) (Chowdhury et al., 2012, 2013), PHB is phosphorylated (Chowdhury et al., 2007, 2013). Furthermore, PHB phosphorylation was not inhibited by phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) inhibitor (LY294002) and protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitor (H89) suggesting that PHB is not a substrate for PKB/AKT or PKA under these experimental conditions. In addition, studies using the selective p38 MAPK (SB203580) and MEK1 (PD98059) inhibitors revealed that PHB is a likely substrate for MEK1 and possibly for p38 MAPK during GC differentiation and survival. In contrast, silencing of PHB expression by adenoviral small interfering RNA (shRNA) or inhibiting ERK phosphorylation through MEK, sensitized GCs to STS-induced apoptosis (Chowdhury et al., 2007, 2013).

PHB/Raf interactions have previously been reported to be essential for activation of the Ras-Raf-MEK1-ERK1/2 pathway (Rajalingam et al., 2005). In support of this observation, our laboratory has consistently observed that, depletion of PHB had a negative impact on STS or FSH-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 without changes in its protein expression levels. These studies show that, in addition to PHB being required for MEK1 activity, PHB is also a potential target of MEK1, suggesting that a possible novel regulatory loop is activated during GC differentiation and survival that is mediated by PHB and affects the Ras-Raf-MEK1-ERK1/2 pathway. These are novel findings and indicate that there is a mutual hierarchical relationship between PHB and the Ras-Raf-MEK1-ERK1/2 pathway (Chowdhury et al., 2013; our unpublished work) and that PHB plays an indispensable role in the activation of the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway (Rajalingam et al., 2005) (Fig. 2).

Molecular studies from other research groups demonstrated that c-Raf activation needs a direct interaction with PHB, whereas, c-Raf kinase fails to interact with the active Ras induced by epidermal growth factor (EGF) in the absence of PHB. Ras is an important proto-oncogene expressed in normal cells and activated Ras may regulate cellular proliferation, migration, invasion via several important downstream effector-signaling pathways, notably Raf-1/MAPK (ERK), PI3K/Akt, and RalGEF/Ral cascades (Karnoub and Weinberg, 2008; Matallanas et al., 2011). Among these downstream pathways, Raf-1 was the first bona fide mammalian Ras effector that was identified (Dhillon et al., 2002). Ras may bind directly to Raf-1, however, it has been shown that full activation of Raf-1 requires PHB (Rajalingam and Rudel, 2005). PHB directly interacts with Raf-1 and is required for the displacement of 14-3-3 (cofactor) from Raf-1 by active Ras to facilitate membrane localization, phosphorylation at S338 and full activation of Raf-1 that regulates epithelial cell adhesion and migration (Rajalingam et al., 2005). Currently, however, whether specific IM localization of PHB has any role in the activation of Raf-1 by Ras is unknown. PHB contains multiple phosphorylation sites and it has been reported that insulin phosphorylates PHB at Y114 and Y259 (Ande et al., 2009), whereas Akt phosphorylates PHB at T258 (Han et al., 2008). Further studies are required to determine whether phosphorylated PHB (phospho-PHB) plays a critical role in the activation or inactivation of Raf-1.

Published studies performed in cancer cell lines have further demonstrated that the level of phospho-PHB in the plasma membrane correlates with the invasiveness of human cancer cells (Chiu et al., 2013). Stable expression of phospho-PHB in the plasma membrane of HeLa and CL1-0 human cancer-cell lines enhanced epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), as well as invasiveness, and promoted in vivo cancer metastasis in a xenograft murine model. Further, by using PHB phosphorylation site mutants, it has been demonstrated that the phosphorylation of PHB at T258 plays critical role in the association of PHB with Raf-1, as well as the enhancement of Raf-1 activation and the invasive capability of cancer cells (Chiu et al., 2013). The phosphorylation of PHB at Thr258 in the plasma membrane of cancer cells activates PI3K/Akt and C-Raf/ERK pathways, which promote proliferation and metastasis (Chiu et al., 2013). In contrast, insulin-receptor-induced phosphorylation of PHB at Tyr114 promotes its heterodimerization with the phosphatase Shp1 and blocks Akt signaling (Ande and Mishra, 2009; Ande et al., 2009; Strub et al., 2011). Interestingly, Akt induced phosphorylation of PHB at Thr258, blocks its interaction with Shp1/2 and facilitates Akt signaling and enhances insulin signaling (Ande and Mishra, 2009).

Additional studies in prostate cancer cells have suggested that binding of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) to its receptor triggers the C-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway to activate protein kinase C δ (PKC-δ), which leads to the phosphorylation of PHB and, consequently, cell survival and invasion (Zhu et al., 2010). In contrast, TGF-β can also cause the opposite effect by activating Smad 2/3 or Smad 1/5, and up-regulating 14-3-3 protein, which then inhibits PKC-δ, leading to a hypophosphorylation of PHB that promotes apoptosis (Zhu et al., 2010). In the early stage of tumorigenesis, therefore, TGF-β acts as a tumor suppressor, but it can subsequently promote metastatic spread during cancer progression. Since, posttranslational modifications of the PHBs have substantial effects on cellular survival pathway, these studies support the hypothesis that phosphorylation of PHB is the active event that is responsible for up-regulation of MEK/ERK activity in a feed-forward loop that potentiate of the signal during cellular survival and differentiation.

Conclusions

Several of the studies on the prohibitins performed so far suggest that prohibitin can function as a “molecular switch” that control cell fate and, thereby, determine the progress of cellular development and differentiation by regulating cellular survival. The survival functions of prohibitins are now only beginning to be elucidated, however, it is clear that these molecular studies on the prohibitins will provide new avenues for the development of clinical applications for cancer, diabetes and obesity. Depending upon the disease state, changes in the levels of PHB expressed in affected cells, such as in diabetes or inflammation, alter the subcellular localization of PHB expression. Despite the current advances in the application of novel molecular techniques and approaches, our grasp of the molecular action of prohibitins and its complexes in cellular survival are poorly understood, and many questions still remain to be answered. The prohibitins exist as both phosphorylated (acidic) and unphosphorylated (basic) forms, and can differentially localize to a number of subcellular compartments, thus suggesting the important multifunctional nature and role that these proteins play in mammalian cells. How PHB and REA individually interact with different kinases other than MEK–ERK pathway under diverse physiological conditions to play a role in cellular survival remains to be further investigated. In addition, how differential multiple sites phosphorylation on PHB are regulated in response to different stimuli have also not been exhaustively investigated to date. Analyses of the PHB and PHB2/REA protein sequences reveal the presence of multiple kinase consensus sequences, however, which kinases are responsible for prohibitins phosphorylation in response to different stimuli remain to be elucidated by future studies.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants 1RO1HD057235, HD41749 and G12-RR03034. This investigation was conducted in a facility constructed with support from Research Facilities Improvement Grant #C06 RR18386 from NIH/NCRR.

Literature Cited

- Ahn CS, Lee JH, Reum Hwang A, Kim WT, Pai HS. Prohibitin is involved in mitochondrial biogenesis in plants. Plant J. 2006;46:658–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akepati VR, Müller EC, Otto A, Strauss HM, Portwich M, Alexander C. Characterization of OPA1 isoforms isolated from mouse tissues. J Neurochem. 2008;106:372–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C, Votruba M, Pesch UE, Thiselton DL, Mayer S, Moore A, Rodriguez M, Kellner U, Leo-Kottler B, Auburger G, Bhattacharya SS, Wissinger B. OPA1, encoding a dynamin-related GTPase, is mutated in autosomal dominant optic atrophy linked to chromosome 3q28. Nat Genet. 2000;26:211–215. doi: 10.1038/79944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altus MS, Wood CM, Stewart DA, Roskams AJ, Friedman V, Henderson T, Owens GA, Danner DB, Jupe ER, Dell’Orco RT, Keith McClung J. Regions of evolutionary conservation between the rat and human prohibitin-encoding genes. Gene. 1995;158:291–294. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ande SR, Mishra S. Prohibitin interacts with phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) and modulates insulin signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:1023–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ande SR, Gu Y, Nyomba BL, Mishra S. Insulin induced phosphorylation of prohibitin at tyrosine 114 recruits Shp1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:1372–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari-Lari MA, Shen Y, Muzny DM, Lee W, Gibbs RA. Large-scale sequencing in human chromosome 12p13: Experimental and computational gene structure determination. Genome Res. 1997;7:268–280. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artal-Sanz M, Tavernarakis N. Prohibitin couples diapause signalling to mitochondrial metabolism during ageing in C. elegans. Nature. 2009;461:793–797. doi: 10.1038/nature08466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artal-Sanz M, Tsang WY, Willems EM, Grivell LA, Lemire BD, van der Spek H, Nijtmans LG. The mitochondrial prohibitin complex is essential for embryonic viability and germline function in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:32091–32099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back JW, Sanz MA, De Jong L, De Koning LJ, Nijtmans LG, De Koster CG, Grivell LA, Van Der Spek H, Muijsers AO. A structure for the yeast prohibitin complex: Structure prediction and evidence from chemical crosslinking and mass spectrometry. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2471–2478. doi: 10.1110/ps.0212602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger KH, Yaffe MP. Prohibitin family members interact genetically with mitochondrial inheritance components in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;8:4043–4052. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein HG, Smalla KH, Dürrschmidt D, Keilhoff G, Dobrowolny H, Steiner J, Schmitt A, Kreutz MR, Bogerts B. Increased density of prohibitin-immunoreactive oligodendrocytes in the dorsolateral prefrontal white matter of subjects with schizophrenia suggests extraneuronal roles for the protein in the disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2012;14:270–280. doi: 10.1007/s12017-012-8185-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boengler K, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Heusch G, Schulz R. Inhibition of permeability transition pore opening by mitochondrial STAT3 and its role in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Basic Res Cardiol. 2010;105:771–785. doi: 10.1007/s00395-010-0124-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu CF, Ho MY, Peng JM, Hung SW, Lee WH, Liang CM, Liang SM. Raf activation by Ras and promotion of cellular metastasis require phosphorylation of prohibitin in the raft domain of the plasma membrane. Oncogene. 2013;32:777–787. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury I, Bhat GK. Mitochondria—In cellular life and death, Chapter 5. In: Svensson OL, editor. In mitochondria structure, functions and dysfunctions. USA: NOVA Publishers; 2010. pp. 247–376. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury I, Tharakan B, Bhat GK. Current concepts in apoptosis: The physiological suicide program revisited. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2006;11:506–525. doi: 10.2478/s11658-006-0041-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury I, Xu W, Stiles JK, Zeleznik A, Yao X, Matthews R, Thomas K, Thompson WE. Apoptosis of rat granulosa cells after staurosporine and serum withdrawal is suppressed by adenovirus-directed overexpression of prohibitin. Endocrinology. 2007;148:206–217. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury I, Tharakan B, Bhat GK. Caspases—An update. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;151:10–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury I, Branch A, Olatinwo M, Thomas K, Matthews R, Thompson WE. Prohibitin (PHB) acts as a potent survival factor against ceramide induced apoptosis in rat granulosa cells. Life Sci. 2011;89:295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury I, Garcia-Barrio M, Harp D, Thomas K, Matthews R, Thompson WE. The emerging roles of prohibitins in folliculogenesis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2012;4:690–699. doi: 10.2741/410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury I, Thompson WE, Welch C, Thomas K, Matthews R. Prohibitin (PHB) inhibits apoptosis in rat granulosa cells (GCs) through the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) and the Bcl family of proteins. Apoptosis. 2013;18:1513–1525. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0901-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates PJ, Nenutil R, McGregor A, Picksley SM, Crouch DH, Hall PA, Wright EG. Mammalian prohibitin proteins respond to mitochondrial stress and decrease during cellular senescence. Exp Cell Res. 2001;265:262–273. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecka AM, Campanella C, Zummo G, Cappello F. Mitochondrial chaperones in cancer: From molecular biology to clinical diagnostics. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:714–720. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.7.2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Cruz S, Parone PA, Gonzalo P, Bienvenut WV, Tondera D, Jourdain A, Quadroni M, Martinou JC. SLP-2 interacts with prohibitins in the mitochondrial inner membrane and contributes to their stability. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:904–911. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dart DA, Spencer-Dene B, Gamble SC, Waxman J, Bevan CL. Manipulating prohibitin levels provides evidence for an in vivo role in androgen regulation of prostate tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:1157–1169. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Monbrison F, Picot S. Introducing antisense oligonucleotides into Pneumocystis carinii. J Microbiol Methods. 2002;50:211–213. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(02)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delettre C, Lenaers G, Griffoin JM, Gigarel N, Lorenzo C, Belenguer P, Pelloquin L, Grosgeorge J, Turc-Carel C, Perret E, Astarie-Dequeker C, Lasquellec L, Arnaud B, Ducommun B, Kaplan J, Hamel CP. Nuclear gene OPA1, encoding a mitochondrial dynamin-related protein, is mutated in dominant optic atrophy. Nat Genet. 2000;26:207–210. doi: 10.1038/79936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delettre C, Griffoin JM, Kaplan J, Dollfus H, Lorenz B, Faivre L, Lenaers G, Belenguer P, Hamel CP. Mutation spectrum and splicing variants in the OPA1 gene. Hum Genet. 2001;109:584–591. doi: 10.1007/s00439-001-0633-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon AS, Meikle S, Yazici Z, Eulitz M, Kolch W. Regulation of Raf-1 activation and signalling by dephosphorylation. EMBO J. 2002;21:64–71. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.1.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, Vaynman S, Souda P, Whitelegge JP, Gomez-Pinilla F. Exercise affects energy metabolism and neural plasticity-related proteins in the hippocampus as revealed by proteomic analysis. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;24:1265–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edman JC, Sogin ML. Molecular phylogeny of Pneumocystis carinnii. In: Walzer PD, editor. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1994. pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Eveleth DD, Jr, Marsh JL. Sequence and expression of the Cc gene, a member of the dopa decarboxylase gene cluster of Drosophila: Possible translational regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:6169–6183. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.15.6169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez L, Paillard M, Price M, Chen Q, Teixeira G, Spiegel S, Lesnefsky EJ. A novel role for mitochondrial sphingosine-1-phosphate produced by sphingosine kinase-2 in PTP-mediated cell survival during cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol. 2011;106:1341–1353. doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0223-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratia S, Kay L, Potenza L, Seffouh A, Novel-Chatè V, Schnebelen C, Sestili P, Schlattner U, Tokarska-Schlattner M. Inhibition of AMPK signalling by doxorubicin: At the crossroads of the cardiac responses to energetic, oxidative, and genotoxic stress. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95:290–299. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory-Bass RC, Olatinwo M, Xu W, Matthews R, Stiles JK, Thomas K, Liu D, Tsang B, Thompson WE. Prohibitin silencing reverses stabilization of mitochondrial integrity and chemoresistance in ovarian cancer cells by increasing their sensitivity to apoptosis. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:1923–1930. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griparic L, van der Wel NN, Orozco IJ, Peters PJ, van der Bliek AM. Loss of the intermembrane space protein Mgm1/OPA1 induces swelling and localized constrictions along the lengths of mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18792–18798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400920200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery O, Malka F, Landes T, Guillou E, Blackstone C, Lombès A, Belenguer P, Arnoult D, Rojo M. Metalloprotease-mediated OPA1 processing is modulated by the mitochondrial membrane potential. Biol Cell. 2008;100:315–325. doi: 10.1042/BC20070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hájek P, Chomyn A, Attardi G. Identification of a novel mitochondrial complex containing mitofusin 2 and stomatin-like protein 2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5670–5681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han EK, McGonigal T, Butler C, Giranda VL, Luo Y. Characterization of Akt overexpression in MiaPaCa-2 cells: Prohibitin is an Akt substrate both in vitro and in cells. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:957–963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He B, Feng Q, Mukherjee A, Lonard DM, DeMayo FJ, Katzenellenbogen BS, Lydon JP, O’Malley BW. A repressive role for prohibitin in estrogen signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:344–360. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henschke P, Vorum H, Honoré B, Rice GE. Protein profiling the effects of in vitro hyperoxic exposure on fetal rabbit lung. Proteomics. 2006;6:1957–1962. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppins S, Lackner L, Nunnari J. The machines that divide and fuse mitochondria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:751–780. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.071905.090048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichishita R, Tanaka K, Sugiura Y, Sayano T, Mihara K, Oka T. An RNAi screen for mitochondrial proteins required to maintain the morphology of the organelle in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biochem. 2008;143:449–454. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara N, Fujita Y, Oka T, Mihara K. Regulation of mitochondrial morphology through proteolytic cleavage of OPA1. EMBO J. 2006;25:2966–2977. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DP. Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C849–C868. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00283.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang X, Zhang L, Sun J, Ni Z, Ma Y, Chen X, Sheng X, Chen T. Prohibitin: A potential biomarker for tissue-based detection of gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:618–625. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnoub AE, Weinberg RA. Ras oncogenes: Split personalities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:517–531. doi: 10.1038/nrm2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasashima K, Ohta E, Kagawa Y, Endo H. Mitochondrial functions and estrogen receptor-dependent nuclear translocation of pleiotropic human prohibitin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36401–36410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathiria AS, Neumann WL, Rhees J, Hotchkiss E, Cheng Y, Genta RM, Meltzer SJ, Souza RF, Theiss AL. Prohibitin attenuates colitis-associated tumorigenesis in mice by modulating p53 and STAT3 apoptotic responses. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5778–5789. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim N, Lee Y, Kim H, Joo H, Youm JB, Park WS, Warda M, Cuong DV, Han J. Potential biomarkers for ischemic heart damage identified in mitochondrial proteins by comparative proteomics. Proteomics. 2006;6:1237–1249. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Lee H, Kim TY, Hwang HR, Lee SC. Differential expression of prohibitin and regulation of apoptosis in wild-type and COX-2 null mouse embryonic fibroblasts. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;53:157–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchman PA, Miceli MV, West RL, Jiang JC, Kim S, Jazwinski SM. Prohibitins and Ras2 protein cooperate in the maintenance of mitochondrial function during yeast aging. Acta Biochim Pol. 2003;50:1039–1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtev V, Margueron R, Kroboth K, Ogris E, Cavailles V, Seiser C. Transcriptional regulation by the repressor of estrogen receptor activity via recruitment of histone deacetylases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24834–24843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Nguyen KH, Mishra S, Nyomba BL, et al. Prohibitin is expressed in pancreatic beta-cells and protects against oxidative and proapoptotic effects of ethanol. FEBS J. 2010a;277:488–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Arnouk H, Sripathi S, Chen P, Zhang R, Bartoli M, Hunt RC, Hrushesky WJ, Chung H, Lee SH, Jahng WJ, et al. Prohibitin as an oxidative stress biomarker in the eye. Int J Biol Macromol. 2010b;47:685–690. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XH, Qian LJ, Gong JB, Shen J, Zhang XM, Qian XH. Proteomic analysis ofmitochondrial proteins in cardiomyocytes from chronic stressed rat. Proteomics. 2004;4:3167–3176. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Ren Z, Zhan R, Wang X, Wang X, Zhang Z, Leng X, Yang Z, Qian L. Prohibitin protects against oxidative stress-induced cell injury in cultured neonatal cardiomyocyte. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2009;14:311–319. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0086-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini PG, Delage-Mourroux R, Kraichely DM, Katzenellenbogen BS. Prothymosin alpha selectively enhances estrogen receptor transcriptional activity by interacting with a repressor of estrogen receptor activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:6224–6232. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.17.6224-6232.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matallanas D, Birtwistle M, Romano D, Zebisch A, Rauch J, von Kriegsheim A, Kolch W. Raf family kinases: Old dogs have learned new tricks. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:232–260. doi: 10.1177/1947601911407323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matikainen T, Perez GI, Zheng TS, Kluzak TR, Rueda BR, Flavell RA, Tilly JL. Caspase-3 gene knockout defines cell lineage specificity for programmed cell death signaling in the ovary. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2468–2480. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkwirth C, Langer T. Prohibitin function within mitochondria: Essential roles for cell proliferation and cristae morphogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkwirth C, Dargazanli S, Tatsuta T, Geimer S, Löwer B, Wunderlich FT, von Kleist-Retzow JC, Waisman A, Westermann B, Langer T. Prohibitins control cell proliferation and apoptosis by regulating OPA1-dependent cristae morphogenesis in mitochondria. Genes Dev. 2008;22:476–488. doi: 10.1101/gad.460708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merkwirth C, Martinelli P, Korwitz A, Morbin M, Brönneke HS, Jordan SD, Rugarli EI, Langer T. Loss of prohibitin membrane scaffolds impairs mitochondrial architecture and leads to tau hyperphosphorylation and neurodegeneration. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1003021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Murphy LC, Murphy LJ. The prohibitins: Emerging roles in diverse functions. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:353–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montano MM, Ekena K, Delage-Mourroux R, Chang W, Martini P, Katzenellenbogen BS. An estrogen receptor-selective coregulator that potentiates the effectiveness of antiestrogens and represses the activity of estrogens. Proc Natl Acad SciUSA. 1999;96:6947–6952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraguchi T, Kawawa A, Kubota S. Prohibitin protects against hypoxia-induced H9c2 cardiomyocyte cell death. Biomed Res. 2010;31:113–122. doi: 10.2220/biomedres.31.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadimpalli R, Yalpani N, Johal GS, Simmons CR. Prohibitins, stomatins and plant disease response genes compose a superfamily that controls cell proliferation, ion channels regulation and death. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29579–29586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002339200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasimhan S, Armstrong M, McClung JK, Richards FF, Spicer EK. Prohibitin, a putative negative control element present in Pneumocystis carinii. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5125–5130. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5125-5130.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijtmans LG, de Jong L, Artal Sanz M, Coates PJ, Berden JA, Back JW, Muijsers AO, van der Spek H, Grivell LA. Prohibitins act as a membrane-bound chaperone for the stabilization of mitochondrial proteins. EMBO J. 2000;19:2444–2451. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijtmans LG, Artal SM, Grivell LA, Coates PJ. The mitochondrial PHB complex: Roles in mitochondrial respiratory complex assembly, ageing and degenerative disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:143–155. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8411-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuell MJ, Stewart DA, Walker L, Friedman V, Wood CM, Owens GA, Smith JR, Schneider EL, Dell’ Orco R, Lumpkin CK, Danner DB, McClung JK. Prohibitin, an evolutionarily conserved intracellular protein that blocks DNA synthesis in normal fibroblasts and HeLa cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1372–1381. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman C, Merkwirth C, Langer T. Prohibitins and the functional compartmentalization of mitochondrial membranes. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3823–3830. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SE, Xu J, Frolova A, Liao L, O’Malley BW, Katzenellenbogen BS. Genetic deletion of the repressor of estrogen receptor activity (REA) enhances the response to estrogen in target tissues in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1989–1999. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1989-1999.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park B, Yang J, Yun N, Choe KM, Jin BK, Oh YJ. Proteomic analysis of expression and protein interactions in a 6-hydroxydopamine-induced rat brain lesionmodel. Neurochem Int. 2010;57:16–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N, Chatterjee SK, Vrbanac V, Chung I, Mu CJ, Olsen RR, Waghorne C, Zetter BR. Rescue of paclitaxel sensitivity by repression of Prohibitin1 in drug-resistant cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:2503–2508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910649107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X, Mehta R, Wang S, Chellappan S, Mehta RG. Prohibitin is a novel target gene of vitamin D involved in its antiproliferative action in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7361–7369. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajalingam K, Rudel T. Ras-Raf signaling needs prohibitin. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1503–1505. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.11.2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajalingam K, Wunder C, Brinkmann V, Churin Y, Hekman M, Sievers C, Rapp UR, Rudel T. Prohibitin is required for Ras-induced Raf-MEK-ERK activation and epithelial cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:837–843. doi: 10.1038/ncb1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JA, Nagy ZS, Kirken RA. The PHB1/2 phosphocomplex is required for mitochondrial homeostasis and survival of human T cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4699–4713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708232200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Saito H, Swensen J, Olifant A, Wood C, Danner D, Sakamoto T, Takita K, Kasumi F, Miki Y, Skolnick M, Nakamura Y. The human prohibitin gene located on chromosome 17q21 is mutated in sporadic breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1992;52:1643–1646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh M, Hamamoto T, Seo N, Kagawa Y, Endo H. Differential sublocalization of the dynamin-related protein OPA1 isoforms in mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:482–493. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02874-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers C, Billig G, Gottschalk K, Rudel T. Prohibitins are required for cancer cell proliferation and adhesion. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12735. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedden WA, Fromm H. Characterization of the plant homologue of prohibitin, a gene associated with antiproliferative activity in mammalian cells. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;33:753–756. doi: 10.1023/a:1005737026289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sripathi SR, He W, Atkinson CL, Smith JJ, Liu Z, Elledge BM, Jahng WJ. Mitochondrial-nuclear communication by prohibitin shuttling under oxidative stress. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8342–8351. doi: 10.1021/bi2008933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steglich G, Neupert W, Langer T. Prohibitins regulate membrane protein degradation by the m-AAA protease in mitochondria. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3435–3442. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strub GM, Paillard M, Liang J, Gomez L, Allegood JC, Hait NC, Maceyka M, Price MM, Chen Q, Simpson DC, Kordula T, Milstien S, Lesnefsky EJ, Spiegel S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate produced by sphingosine kinase 2 in mitochondria interacts with prohibitin 2 to regulate complex IV assembly and respiration. FASEB J. 2011;25:600–612. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-167502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supale S, Thorel F, Merkwirth C, Gjinovci A, Herrera PL, Scorrano L, Meda P, Langer T, Maechler P. Loss of prohibitin induces mitochondrial damages altering β-cell function and survival and is responsible for gradual diabetes development. Diabetes. 2013;62:3488–3499. doi: 10.2337/db13-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A, Kawasaki T, Wong HL, Suharsono U, Hirano H, Shimamoto K. Hyperphosphorylation of a mitochondrial protein, prohibitin, is induced by calyculin A in a rice lesion-mimic mutant cdr1. Plant Physiol. 2003;132:1861–1869. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.021733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuta T, Model K, Langer T. Formation of membrane-bound ring complexes by prohibitins in mitochondria. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:248–259. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-09-0807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavernarakis N, Driscoll M, Kyrpides NC. The SPFH domain: Implicated in regulating targeted protein turnover in stomatins and other membrane-associated proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:425–427. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01467-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima M, Kim KM, Adachi T, Nielsen PJ, Reth KG, Lamers MC. The IgM antigen receptor of B lymphocytes is associated with prohibitin and a prohibitin-related protein. EMBO J. 1994;13:3782–3792. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theiss AL, Idell RD, Srinivasan S, Klapproth JM, Jones DP, Merlin D, Sitaraman SV. Prohibitin protects against oxidative stress in intestinal epithelial cells. FASEB J. 2007;21:197–206. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6801com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theiss AL, Vijay-Kumar M, Obertone TS, Jones DP, Hansen JM, Gewirtz AT, Merlin D, Sitaraman SV. Prohibitin is a novel regulator of antioxidant response that attenuates colonic inflammation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:199–208. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WE, Sanbuissho A, Lee GY, Anderson E. Steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein (p25) and prohibitin (p28) from cultured rat ovarian granulosa cells. J Reprod Fertil. 1997;109:337–348. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1090337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WE, Powell JM, Whittaker JA, Sridaran R, Thomas KH. Immunolocalization and expression of prohibitin, a mitochondrial associated protein within the rat ovaries. Anat Rec. 1999;256:40–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990901)256:1<40::AID-AR6>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WE, Branch A, Whittaker JA, Lyn D, Zilberstein M, Mayo KE, Thomas K. Characterization of prohibitin in a newly established rat ovarian granulosa cell line. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4076–4085. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WE, Asselin E, Branch A, Stiles JK, Sutovsky P, Lai L, Im G-S, Prather RS, Isom SC, Rucker E, III, Tsang B. Regulation of prohibitin expression during follicular development and atresia in the mammalian ovary. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:282–290. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.024125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuaud F, Ribeiro N, Nebigil CG, Désaubry L. Prohibitin ligands in cell death and survival: Mode of action and therapeutic potential. Chem Biol. 2013;20:316–331. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi T, Matsuda M, Aizaki H, Moriya K, Miyoshi H, Fujie H, Shintani Y, Yotsuyanagi H, Miyamura T, Suzuki T, Koike K. Proteomics analysis of mitochondrial proteins reveals overexpression of a mitochondrial protein chaperon, prohibitin, in cells expressing hepatitis C virus core protein. Hepatology. 2009;50:378–386. doi: 10.1002/hep.22998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ummanni R, Junker H, Zimmermann U, Venz S, Teller S, Giebel J, Scharf C, Woenckhaus C, Dombrowski F, Walther R. Prohibitin identified by proteomic analysis of prostate biopsies distinguishes hyperplasia and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Nath N, Fusaro G, Chellappan S. Rb and prohibitin target distinct regions of E2F1 for repression and respond to different upstream signals. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7447–7460. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Zhang B, Faller DV. Prohibitin requires Brg-1 and Brm for the repression of E2F and cell growth. EMBO J. 2002;21:3019–3028. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Leader A, Tsang BK. Follicular stage-dependent regulation of apoptosis and steroidogenesis by prohibitin in rat granulosa cells. J Ovarian Res. 2013;6:23. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-6-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welburn SC, Murphy NB. Prohibitin and RACK homologues are up-regulated in trypanosomes induced to undergo apoptosis and in naturally occurring terminally differentiated forms. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:615–622. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu TF, Wu H, Wang YW, Chang TY, Chan SH, Lin YP, Liu HS, Chow NH. Prohibitin in the pathogenesis of transitional cell bladder cancer. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:895–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou TB, Qin YH, Zhou C, Lei FY, Zhao YJ, Chen J, Su LN, Huang WF. Less expression of prohibitin is associated with increased caspase-3 expression and cell apoptosis in renal interstitial fibrosis rats. Nephrology (Carlton) 2012;17:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2011.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B, Zhai J, Zhu H, Kyprianou N. Prohibitin regulates TGF-beta induced apoptosis as a downstream effector of Smad-dependent and -independent signaling. Prostate. 2010;70:17–26. doi: 10.1002/pros.21033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]