Abstract

Retinal ischemia plays a critical role in multiple vision-threatening diseases and leads to death of retinal neurons, particularly ganglion cells. Oxidative stress plays an important role in this ganglion cell loss. Nrf2 (NF-E2-related factor 2) is a major regulator of the antioxidant response, and its role in the retina is increasingly appreciated. We investigated the potential retinal neuroprotective function of Nrf2 after ischemia-reperfusion (I-R) injury. In an experimental model of retinal I/R, Nrf2 knockout mice exhibited much greater loss of neuronal cells in the ganglion cell layer than wild-type mice. Primary retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) isolated from Nrf2 knockout mice exhibited decreased cell viability compared to wild-type RGCs, demonstrating the cell-intrinsic protective role of Nrf2. The retinal neuronal cell line 661W exhibited reduced cell viability following siRNA-mediated knockdown of Nrf2 under conditions of oxidative stress, and this was associated with exacerbation of increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS). The synthetic triterpenoid CDDO-Im (2-Cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-imidazolide), a potent Nrf2 activator, inhibited ROS increase in cultured 661W under oxidative stress conditions and increased neuronal cell survival after I/R injury in wild-type, but not Nrf2, knockout mice. Our findings indicate that Nrf2 exhibits a retinal neuroprotective function in I-R and suggest that pharmacologic activation of Nrf2 could be a therapeutic strategy.

Keywords: ischemia, oxidative stress, retina, ganglion cell, Nrf2

Introduction

Retinal ischemia plays an important role in the pathogenesis of several vision-threatening diseases, including acute angle-closure glaucoma, retinal vascular occlusions, diabetic retinopathy, and retinopathy of prematurity (Osborne et al. 2004). Retinal neurons, and particularly ganglion cells, are particularly susceptible, and indeed, retinal ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) critically contributes to retinal ganglion cell death and subsequent vision loss in acute glaucoma. The pathogenesis of cellular injury in ischemia-reperfusion is thought to include the generation of reactive oxygen species (McCord 1985, Zweier et al. 1987), which can have a direct damaging effect on cells in addition to generating an inflammatory process (Korthuis & Granger 1993). The importance of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of retinal I/R and ganglion cell death is highlighted by studies demonstrating the beneficial effect of antioxidant gene therapy in abrogating ganglion cell loss (Liu et al. 2012). Indeed, the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is thought to be an important contributor to neurotoxicity in multiple acute and chronic neurodegenerative diseases (Bastianetto & Quirion 2004). As a result, there is urgent need for a greater understanding of the intrinsic retinal mechanisms regulating oxidative stress for the development of new therapies for ischemia-reperfusion injury in the retina as well as the CNS.

Nrf2 (NF-E2-related factor 2) is a transcription factor that plays a major role in cellular protection from endogenous and exogenous stresses (Kensler et al. 2007). Nrf2 is a master regulator of the antioxidant response in multiple tissues and acts as one of the most important cellular pathways in protecting against oxidative stress (Kensler et al. 2007). Under physiological conditions, Nrf2 resides in the cytoplasm bound to its inhibitor, Keap 1, which targets Nrf2 toward proteosomal degradation. Multiple endogenous and exogenous molecules including reactive oxygen species disrupt the interaction of Keap1 with Nrf2, resulting in the nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and its transcriptional activation of an array of cytoprotective and antioxidant genes via binding to the antioxidant response element (ARE) (Kensler et al. 2007). This mode of regulation renders Nrf2 amenable to pharmacologic modulation, as multiple drugs can activate Nrf2.

Nrf2 has been found to play an important role in neurons, and the Nrf2-ARE pathway has been implicated as an important neuroprotective mechanism under certain conditions. Indeed, therapeutic activation of Nrf2 is being actively explored for neurodegenerative diseases of the central nervous system including Parkinson and Alzheimer, given the role of reactive oxygen species in these conditions (Gan & Johnson 2014, Calkins et al. 2009, Johnson et al. 2008). In the retina, Nrf2 is beginning to receive attention for its role in protecting neurons, and especially ganglion cells, particularly in the setting of optic nerve crush. Endogenous Nrf2 activity was found to be protective of retinal ganglion cells in rodents in an optic nerve crush model (Himori et al. 2013). Therapies targeting Nrf2 were found to be beneficial for neuroprotection of ganglion cells after optic nerve crush (Koriyama et al. 2013, Himori et al. 2013, Koriyama et al. 2010).

Our lab previously found evidence for a neuroprotective role in the retina for mouse models of diabetic retinopathy (Xu et al. 2014) and ischemia-reperfusion (Wei et al. 2011). In a diabetic retinopathy model, Nrf2 knockout exhibited greater neuronal dysfunction compared to wild-type (Xu et al. 2014). In the model of retinal I/R, Nrf2 knockout mice exhibited evidence of neurodegeneration at a relatively early time-point (two days post I-R), as compared to wild-type mice, which did not show neurodegeneration. In this setting, Nrf2 knockouts also exhibited an exacerbation of oxidative stress and capillary degeneration in the retina (Wei et al. 2011). We found that treatment with an Nrf2 activator was therapeutic for both oxidative stress and capillary degeneration. In the current study, we explored the role of Nrf2 in retinal ganglion cells and neurons, using both in vivo and in vitro approaches. We also investigated whether pharmacologic activation of Nrf2 with the triterpenoid, CDDO-Im, had a protective role in retinal ganglion cells in vivo as well as in cultured neurons.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Nrf2−/− and Nrf2+/+ mice generated and backcrossed into C57BL/6 background (Yamamoto, 1997, BBRC) were used for all experiments (Wei et al. 2011, Xu et al. 2014). The mice were maintained under standard conditions with free access to water and food and with a 12 hour light to dark cycle. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and conducted in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals and in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Mouse model of retina ischemia reperfusion

Retina ischemia reperfusion was performed as previously described (Wei et al. 2011). After deep anesthesia with an intraperitoneal injection of a cocktail (100 mg/kg ketamine, 10 mg/kg xylazine and 3 mg/kg acepromazine), the anterior chamber of the left eye was cannulated with a 30-gauge blunt needle attached to a line infusing 0.9% sterile saline. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was raised to 90 mm Hg by elevating the saline container for 90 min. The retina was monitored of blanching indicating retina ischemia. After completion of ischemia, the needle was withdrawn from the eye and the IOP was restored. The right eye of the same mouse was used as the control.

Retina whole-mount immunostaining

Surviving neurons in the ganglion cell layer were quantitated by confocal microscopy using the neuronal cell marker NeuN, as previously described (Yokota et al. 2011). Retinal whole-mount staining was performed as previously described (Xu et al. 2012). Briefly, mouse eyes were enucleated and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. After corneas and lens were removed, the eyecups were fixed in 4% PFA for 10 minutes, and retinas were carefully dissected from the eye cup. After one hour of blocking in 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBST (PBS plus 0.3% Triton X-100), retinas were incubated with anti-NeuN antibody (1:600, Millipore, Billerica, MA) at 4°C overnight. Retinas were then washed in PBST for 6 hours and incubated with anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 4°C overnight. After washing with PBST, the retinas were flat-mounted on slides in Fluoromount-G (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). The survival of neuronal cells in ganglion cell layer was analyzed as described (Yokota et al. 2011). Retina whole-mount images were taken using a confocal Zeiss microscope (LSM 710, Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with 20× objective lens. Eight random fields in mid-periphery retina were used for image taking. For each field, 5 images with 1µm interval in ganglion cell layer were taken and then merged to produce well focused images with maximum signal. NeuN-positive cells in GCL were then counted using Image J program (NIH).

Cell culture

Mouse primary ganglion cells were purified from Nrf2 +/+ and Nrf2−/− pups at postnatal day 2 to 4 using immunopanning technique (Welsbie et al. 2013). Primary RGCs were seeded into 96 well plate at a density of 8000 cell per well supplemented with CTGF and BDNF. Cell viability was measured four days after purification. 661W cells, a mouse photoreceptor cell line, were a kind gift from Dr. Muayyad R. Al-Ubaidi (University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) (Tan et al. 2004). 661W cells were cultured in DMEM plus 10% FBS. Sub-confluent 661W cells were transfected with negative control #2 siRNA, Nrf2 siRNA (s9493) (Applied Biosystems, Foster city, CA) using lipofectamine 2000.

Real-time PCR analysis

RNA was isolated using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and single-stranded cDNA was synthesized using MMLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen). qPCR was performed with QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) with StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The qPCR primers were NQO1: (5’- CAGCTCACCGAGAGCCTAGT-3’) and (5’- ACCACCTCCCATCCTTTCTT-3’); GCLC: (5’-ACCATCATCAATGGGAAGGA-3’) and (5’-GCGATAAACTCCCTCATCCA-3’); GCLM: (5’- TGGAGCAGCTGTATCAGTGG-3’) and (5’-AGAGCAGTTCTTTCGGGTCA-3’); HO-1: (5’-ATGACACCAAGGACCAGAGC-3’) and (5’- GTGTAAGGACCCATCGGAGA-3’); : GSTM1: (5’-AGTGGGTGGGAAAGGGTCATTACA-3’ and (5’-TAGCCAAGGCTTCTGCTGGTACTT-3’); TXNRD1: (5’-AACTTTCAGAAGGGCCAGGT-3’) and (5’-GTAGACAGGGGCGAAGACTG-3’). β-actin: (5’- AGAAAATCTGGCACCACACC-3’) and (5’- GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAA-3’) was used for normalization.

Western blot analysis

For analysis of Nrf2 nuclear translocation, nuclear extracts from cell culture were prepared using NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Anti-Nrf2 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology) and anti-Lamin B antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, Texas, USA) were used for Western blot analysis. The intensity of band was quantitated using Image J program (NIH).

DCF assay

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production was quantified by dichlorofluorescein (DCF) assay. 48 h after siRNA transfection, 661W cells were treated with or without different doses of tert-Butyl hydroperoxide (TBH, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 1 h. 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA) (10 µmol/L, Invitrogen) was then added to cells and incubated for 30 min. DCF fluorescence was measured with a spectrophotometer (BMG Labtech Inc., Durham, NC).

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was measured using the Celltiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Promega, Madison, WI), which measures number of viable cells based on the amount of ATP, reflecting metabolically active cells. 100 µL Celltiter-Glo reagent was added to each well containing 100 µL growth medium. After incubation at room temperature for 60 min, luminescence was read with a spectrophotometer (BMG labtech Inc.). Primary ganglion cells were also labeled with calcein-AM (2.3µg/mL, Life Technologies), Hoechst 33342 (2.75µg/mL, Life Technologies) and ethidium bromide homodimer-1 (2µM, Life Technologies) for live cell scanning. The live cells were counted using the Cellomics ArrayScan VTI HCS reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

CDDO-Im treatment

To confirm Nrf2 target gene activation by CDDO-Im in vivo, adult mice were treated with one intraperitoneal injection of 3 µmol/kg of CDDO-Im (dissolved in 10% DMSO, 10% cremphor and 80% PBS) or vehicle for 6 hours. For CDDO-Im’s neuroprotective study in I-R model, mice were pretreated with 3 µmol/kg of CDDO-Im via intraperitoneal injection at 2 days, 1 day, 0 day before I-R (alternatively, for a separate interventional study, mice received their initial intraperitioneal injection immediately after ischemia-reperfusion). After I-R, mice were treated with CDDO-Im daily for 6 days.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± SD. The Student t-test was used for two groups’ comparison. Multiple groups were compared by using one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Exacerbated neuronal cell loss in retinal ganglion cell layer in Nrf2−/− mice after I/R

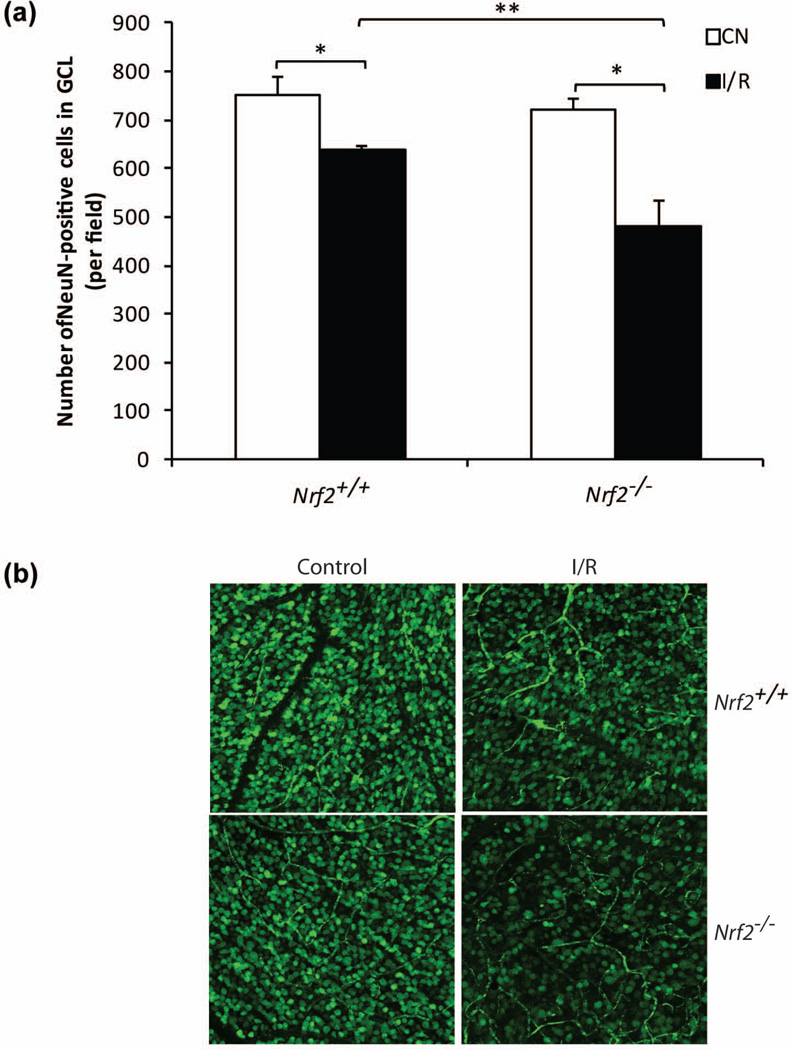

We previously found that cell counts in the ganglion cell layer were significantly reduced in Nrf2−/− mice after 48 hours of ischemia-reperfusion (Wei et al. 2011). In comparison, wild-type mice exhibited no reduction at this time, indicating that Nrf2 deficiency led to earlier onset of neuronal cell death. In order to determine whether Nrf2 has a sustained retinal neuroprotective effect, we performed studies after 7 days of I/R. For quantitation of cell counts in the ganglion cell layer, we used the RGC marker, NeuN, which has previously been utilized for this purpose in retinal ischemia-reperfusion studies (Yokota et al. 2011, Kim et al. 2013). We performed NeuN staining of retina flat-mounts and used confocal image analysis to quantify NeuN-positive cells within the ganglion cell layer, as previously published (Yokota et al. 2011). We observed a significant loss of GCL cell number in wild-type mice (~15%, P < 0.05, n=4) (Fig. 1a and 1b). Strikingly, I/R induced a further 20% loss of NeuN-positive neuronal cell in GCL in Nrf2−/− mice retina (Fig. 1a and 1b). This indicates that Nrf2 has a sustained neuroprotective effect over time in retinal I/R, such that Nrf2 deficiency results in about twice the degree of neurodegeneration.

Figure 1.

Exacerbated neuronal cell loss in ganglion cell layer (GCL) in Nrf2−/− mice after I/R. (a) The number of survived neuronal cells in GCL were counted 7 days after I/R. n=4. *, p<0.05, **, p<0.01. (b) Representative confocal images of NeuN-stained (green) GCL neuronal cells in flat-mount retinas were shown.

Nrf2 is important for primary retinal ganglion cell survival in vitro

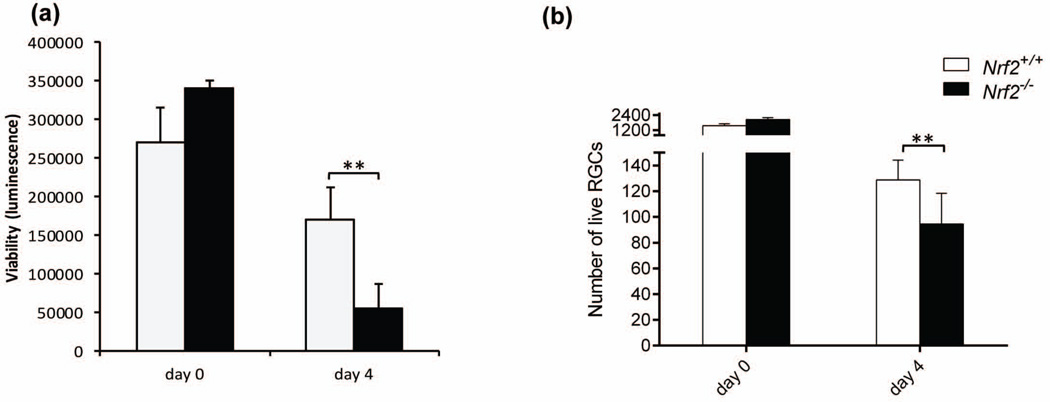

To understand whether Nrf2 has a direct cell-intrinsic role in retinal ganglion cell (RGC) survival, we purified and cultured primary ganglion cells from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− mice retina using an immunopanning technique (Welsbie et al. 2013). This approach necessarily involves axotomy, with consequent cellular stress and injury. We used two different methods to measure ganglion cell survival of ganglion cells, the first quantitating luminescence signal proportional to ATP amount (Fig. 2a) and the second counting Calcein AM-stained live cells (Fig. 2b). RGCs from Nrf2−/− mice exhibited significantly lower survival rate (60% reduction of ATP luminescence and 27% reduction of live cell number) compared with RGCs from Nrf2+/+ retinas under normal conditions (Fig. 2). Conceivably, the larger effect of Nrf2 deficiency measured with the ATP luminescence approach compared to Calcein AM may reflect a markedly diminished metabolic activity in the Nrf2-deficient ganglion cells.

Figure 2.

Nrf2 is critical for RGC survival in vitro. (a) Primary RGCs from Nrf2+/+ and Nrf2−/− were cultured for 4 days, and cell survival were detected using Celltiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay. (b) Calcein AM, hoechst 33342 and ethidium homodimer triple staining of live cells showed decreased cell number of RGCs deficient of Nrf2. n=4–8. *, p< 0.05; **, p<0.01.

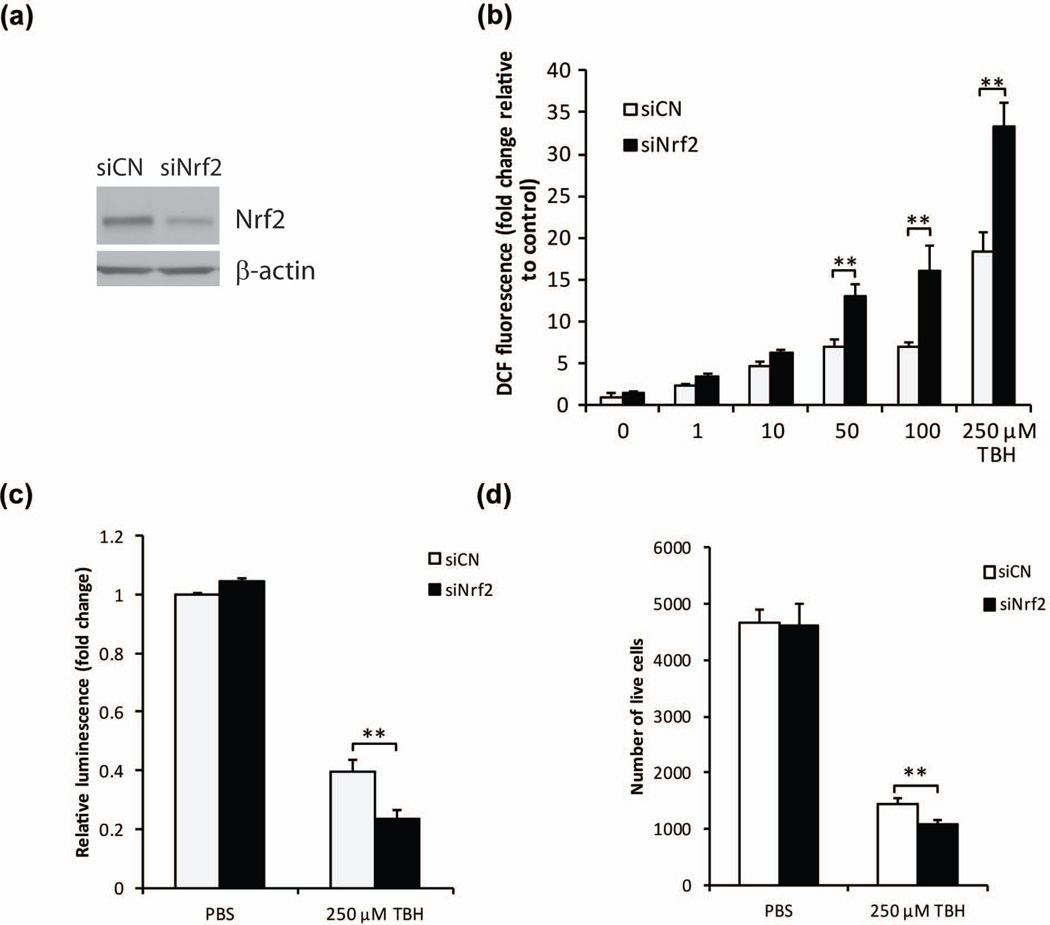

The effect of Nrf2 down-regulation on TBH-induced ROS production and cell survival in 661W cells

Oxidative stress is thought to be a critical cause of neurodegeneration in retinal ischemia-reperfusion (Liu et al. 2012). In order to gain further insights into the cell-intrinsic effects of Nrf2 on retinal neurons in the context of oxidative stress, we performed studies using the 661W retinal neuronal cell line (Tan et al. 2004), which has been a useful model system for insights regarding retinal neuroprotection (Inoue et al. 2014): it should be noted that there currently are no available retinal ganglion cell lines. We first investigated whether the knockdown of Nrf2 expression would affect oxidative stress in this 661W cell line. To achieve knockdown of Nrf2 expression, Nrf2 siRNA was transfected into 661W cells, and decreased Nrf2 protein level was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3a). After incubation with different doses of TBH, cells transfected with control siRNA showed dose-dependent ROS increase (Fig. 3b). Nrf2 siRNA caused two-fold increase of ROS level with 50, 100, and 250 µM TBH treatments (Fig. 3b). We also investigated whether Nrf2 knockdown could affect cell survival. After treating 661W cells with TBH, we found cell survival, measured by ATP amount and reflected by luminescence intensity, was decreased by 250 µM TBH (Fig. 3c). After knocking down Nrf2 by siRNA transfection, the cell survival with 250 µM TBH treatment decreased about 40% compared with control siRNA-transfected cells (Fig. 3c). Calcein AM, Hoechst 33342 and ethidium homodimer triple staining also confirmed a significant 25% cell loss in Nrf2-siRNA transfected cells (Fig 3d)

Figure 3.

Nrf2 protects against oxidant-induced ROS increase and cell survival in 661W cells. (a) Western blot analysis of Nrf2 expression after 48 h of Nrf2 siRNA transfection. (b) Down-regulation of Nrf2 by Nrf2 siRNA affected TBH-induced oxidative stress in 661W cells. 48 h after siRNA transfection, cells were challenged by different doses of TBH for 1 h. ROS levels were determined by DCF assay. n=4, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs control siRNA with TBH treatment. (c) Down-regulation of Nrf2 exacerbates TBH-caused decrease of cell viability. 48 h after siRNA transfection, cells were challenged by TBH for 24 h. n=3, **p < 0.01 vs control siRNA treated with TBH. White bars: control siRNA; black bars: Nrf2 siRNA. (d) Calcein AM, hoechst 33342 and ethidium homodimer triple staining showed further cell loss in Nrf2 siRNA-transfected cells. n=5, **p < 0.01.

Nrf2 activator CDDO-Im protects against TBH-induced ROS production in 661W cells

In light of Nrf2’s important role as an endogenous regulator of oxidative stress, we were interested in determining whether pharmacologic enhancement of Nrf2 could reduce oxidative stress in 661W cells. Synthetic triterpenoids are potent inducers of Nrf2 that act by promoting nuclear translocation of Nrf2 (Liby et al. 2005, Liby et al. 2007) and have been successfully used to activate Nrf2 in the retina (Nagai et al. 2009, Pitha-Rowe et al. 2009, Wei et al. 2011). We investigated whether triterpenoid CDDO-Im has any protective effect against ROS production in 661W cells. We first determined the effective dose of CDDO-Im to activate Nrf2 nuclear translocation. As shown in Fig. 4a and 4b, 100 nM CDDO-Im can efficiently induce Nrf2 nuclear translocation. Many well-known Nrf2 target genes, such as NQO1, GCLC, GCLM and HO1 were also up-regulated by different doses of CDDO-Im, although different target genes required different doses of CDDO-Im to achieve the maximal induction (Fig. 4c). DCF assay showed that CDDO-Im inhibited TBH-induced ROS increase in 661W cells in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 4d), while the same dose range of CDDO-Im did not cause toxicity effect in cells (Fig. 4e).

Figure 4.

The CDDO-Im’s protective effect against TBH-induced oxidative stress in 661W cells. (a) Representative western blot analysis of Nrf2 nuclear translocation showed increased nuclear localization after 24 hours treatment of CDDO-Im. (b) Quantitation of western blot analysis of Nrf2 nuclear translocation by densitometry indicated significant induction by CDDO-Im (n = 3, *p < 0.05) (c) Dose dependent increase of Nrf2-responsive antioxidant gene expression in 661W cells by CDDO-Im (n=4, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01). (d) Dose response effect of CDDO-Im on inhibiting TBH-induced ROS increase. Cells were pretreated with CDDO-Im for 24 hours before challenged by TBH for 1 h. ROS levels were determined by DCF assay. n=3, *p < 0.05 vs PBS group. (e) Same dose range of CDDO-Im did not cause cell toxicity. n=4, *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 vs TBH treatment.

Nrf2 activator CDDO-Im protects against I/R-induced retinal neuronal loss

Next we examined whether Nrf2 activator CDDO-Im possess any neuronal protective effect against I/R injury in vivo. 3 µmol/kg of CDDO-Im significantly increased multiple Nrf2 target gene expression, such as NQO1, HO1, GCLC, GSTM1, TXNRD1 and GCLM in wild-type mice retina, 6 hours after intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection (Fig. 5a–5f). Similar Nrf2 target gene induction was observed after multiple daily injections of CDDO-Im (Supplemental Figure 1). No change on Nrf2 target gene activation was observed in Nrf2−/− mice retina (Fig. 5a–5f). Daily i.p injection of CDDO-Im starting from 2 days before I/R to 6 days after I/R significantly increased GCL neuronal cell survival in Nrf2+/+ mice around 2-fold (67% loss in vehicle group vs 37% loss in CDDO-Im treatment group) (Fig. 5g–5h). Importantly, no neuro-protective effect was found in Nrf2−/− mice (Fig. 5g–5h), indicating that CDDO-Im’s protective effect was through activation of the Nrf2 pathway. We also investigated whether an interventional treatment approach with CDDO-Im would provide a rescue effect on I/R-induced neuronal inury. For this approach, mice received their initial intraperitonal injection of CDDO-Im immediately after I/R injury, with subsequent daily drug administration for 6 days. As shown in Supplemental figure 2, the CDDO-Im treated group exhibited significantly less neuronal cell loss compared to the vehicle-treated group, indicating that intervention with CDDO-Im was also protective.

Figure 5.

CDDO-Im rescues I/R-induced retinal neuronal cell loss in GCL in wild-type mice but not in Nrf2−/− mice. (a–f) Up-regulation of retinal Nrf2 target gene expression by CDDO-Im in wild-type mice but not in Nrf2−/− mice. 6 hours after one intraperitoneal injection of 3 µmol/kg CDDO-Im, RNA was extracted from retinas for q-PCR analysis of Nrf2 target gene expression. n=4–6, **, p < 0.01. (g) The number of NeuN-positive neuronal cells in GCL was counted. White bar: control group; Black bar: I/R group. n=4–6. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.001, NS, not significant. (h) Representative confocal images of NeuN-labelled (green) retina flat-mounts were shown.

Discussion

Although tremendous efforts have been made to develop neuroprotective drugs for both acute and chronic retinal diseases, there is still no clinically approved therapy. In the present study, we investigated the role of Nrf2 in retinal neuroprotection, especially in the context of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Using Nrf2 knockout mice, we found that Nrf2 exerts an endogenously protective effect that is sustained over time. Our studies also suggest that these protective effects are cell-autonomous in retinal ganglion cells and retinal neurons. Therapy with the triterpenoid CDDO-Im, a potent Nrf2 activator, significantly reduces neurodegeneration after I/R, indicating that triterpenoids could be promising as a new class of drugs for retinal neuroprotection. Finally, the Nrf2-dependence of CDDO-Im’s beneficial effects in I/R directly implicates the Nrf2 pathway as a therapeutic target for retinal neuroprotection.

We found that endogenous Nrf2 is important in protecting RGCs from I/R-induced death. We previously reported that Nrf2 deficiency led to an earlier onset of neurodegeneration following I/R which was evident as early as 2 days following I/R (Wei et al. 2011). In the current study, we found that there was a significant exacerbation in neuronal cell loss in the ganglion cell layer in Nrf2 knockout mice 7 days after I/R, as compared to wild-type. There was no difference in the ganglion cell layer thickness under non-stress conditions. This indicates that Nrf2 deficiency exacerbates neuronal injury resulting from the I/R insult, demonstrating that the neuroprotective effect of Nrf2 is sustained in retinal ischemia-reperfusion. This is consistent with the increasing evidence that Nrf2 is active in the retina, suggesting that its antioxidant effects can mitigate the effects of oxidative stress on degeneration of ganglion cells in retinal I/R.

We were interested in further demonstrating that Nrf2 has a direct effect in protecting ganglion cells against oxidative stress under I/R conditions. As a first step, we compared primary retinal ganglion cells isolated from wild-type and Nrf2 knockout mice and found significantly increased survival in wild-type ganglion cells, confirming a ganglion cell-autonomous neuroprotective effect of Nrf2. In order to gain further insights into cell-autonomous role of Nrf2 in neurons, specifically under oxidative stress conditions, we investigated the retinal neuronal cell line 661W, which has been a useful in vitro system for studying retinal neuroprotection. Using siRNA-mediated Nrf2 knockdown, we found a definitive role for Nrf2 in the regulation of reactive oxygen species and cell viability of 661W cells following oxidative stress challenge. Taken together with the studies of primary mouse retinal ganglion cells, this indicates that Nrf2 is operative in retinal ganglion cells and neurons and that endogenous Nrf2 activity has an important neuroprotective effect, mitigating the harmful effects of oxidative stress.

An attractive aspect of Nrf2 is its amenability to pharmacologic activation. Keap1 functions as a critical inhibitor of Nrf2, binding and sequestering Nrf2 in the cytosol, and also targeting it toward proteosomal degradation. This interaction between Keap1 and Nrf2 can be disrupted by endogenous and exogenous cues including reactive oxygen species. This renders Nrf2 highly amenable to modulation by various drugs, including sulforaphane. Triterpenoids are known to be particularly potent activators of Nrf2 (Liby et al. 2007), and our lab has previously demonstrated the efficacy of triterpenoid treatment in the alleviation of oxidative stress and capillary degeneration following retinal I/R (Wei et al. 2011). Therefore, we first explored the effect of the triterpenoid CDDO-Im [22] on cultured 661W cells, and found that CDDO-Im was effective in the induction of Nrf2 target genes in 661W cells, as well as in the protection of these cells against oxidative stress challenge. In mice, treatment with CDDO-Im induced Nrf2 target genes and also significantly reduced loss of cells in the ganglion cell layer following retinal I/R. Importantly, both effects were seen in wild-type, but not Nrf2, knockout mice, demonstrating the Nrf2-dependence of these effects.

Our results highlight pharmacological targeting of Nrf2 for retinal neuroprotection in the setting of retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury, a condition for which there is currently no available treatment. Targeting of Nrf2 may be an important resource in the protection of retinal ganglion cells under multiple disease settings in light of previous studies of Nrf2-mediated neuroprotection of ganglion cells in the optic nerve crush model [12–14]. Since retinal I/R shares similarities regarding pathophysiology with I/R in other tissues, pharmacological targeting of Nrf2 could prove important in I/R injury outside the eye, particularly as a strategy for neuroprotection of the CNS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (EY022383 and EY022683; EJD) and Bright Focus Foundation (ZX) and Core grant (P30EY001765), Imaging and Microscopy Core Module. We thank Cynthia Berlinicke for the help with the Cellomics ArrayScan HCS system and data analysis.

Abbreviations used

- Nrf2

NF-E2-related factor 2

- I/R

ischemia-reperfusion

- RGCs

retinal ganglion cells

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- CDDO-Im

2-Cyano-3,12-dioxooleana-1,9-dien-28-imidazolide

- ARE

antioxidant response element

- IOP

intraocular pressure

- TBH

tert-Butyl hydroperoxide

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Bastianetto S, Quirion R. Natural antioxidants and neurodegenerative diseases. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 2004;9:3447–3452. doi: 10.2741/1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins MJ, Johnson DA, Townsend JA, et al. The Nrf2/ARE pathway as a potential therapeutic target in neurodegenerative disease. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2009;11:497–508. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L, Johnson JA. Oxidative damage and the Nrf2-ARE pathway in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1842:1208–1218. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himori N, Yamamoto K, Maruyama K, Ryu M, Taguchi K, Yamamoto M, Nakazawa T. Critical role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress-induced retinal ganglion cell death. Journal of neurochemistry. 2013;127:669–680. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue Y, Shimazawa M, Nakamura S, Imamura T, Sugitani S, Tsuruma K, Hara H. Protective effects of placental growth factor on retinal neuronal cell damage. Journal of neuroscience research. 2014;92:329–337. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JA, Johnson DA, Kraft AD, Calkins MJ, Jakel RJ, Vargas MR, Chen PC. The Nrf2-ARE pathway: an indicator and modulator of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1147:61–69. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:89–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim BJ, Braun TA, Wordinger RJ, Clark AF. Progressive morphological changes and impaired retinal function associated with temporal regulation of gene expression after retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Molecular neurodegeneration. 2013;8:21. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koriyama Y, Chiba K, Yamazaki M, Suzuki H, Muramoto K, Kato S. Long-acting genipin derivative protects retinal ganglion cells from oxidative stress models in vitro and in vivo through the Nrf2/antioxidant response element signaling pathway. Journal of neurochemistry. 2010;115:79–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koriyama Y, Nakayama Y, Matsugo S, Kato S. Protective effect of lipoic acid against oxidative stress is mediated by Keap1/Nrf2-dependent heme oxygenase-1 induction in the RGC-5 cellline. Brain research. 2013;1499:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthuis RJ, Granger DN. Reactive oxygen metabolites, neutrophils, and the pathogenesis of ischemic-tissue/reperfusion. Clin Cardiol. 1993;16:19–26. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960161307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liby K, Hock T, Yore MM, et al. The synthetic triterpenoids, CDDO and CDDO-imidazolide, are potent inducers of heme oxygenase-1 and Nrf2/ARE signaling. Cancer research. 2005;65:4789–4798. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liby KT, Yore MM, Sporn MB. Triterpenoids and rexinoids as multifunctional agents for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:357–369. doi: 10.1038/nrc2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Tang L, Chen B. Effects of antioxidant gene therapy on retinal neurons and oxidative stress in a model of retinal ischemia/reperfusion. Free radical biology & medicine. 2012;52:909–915. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord JM. Oxygen-derived free radicals in postischemic tissue injury. The New England journal of medicine. 1985;312:159–163. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai N, Thimmulappa RK, Cano M, et al. Nrf2 is a critical modulator of the innate immune response in a model of uveitis. Free radical biology & medicine. 2009;47:300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne NN, Casson RJ, Wood JP, Chidlow G, Graham M, Melena J. Retinal ischemia: mechanisms of damage and potential therapeutic strategies. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2004;23:91–147. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitha-Rowe I, Liby K, Royce D, Sporn M. Synthetic triterpenoids attenuate cytotoxic retinal injury: cross-talk between Nrf2 and PI3K/AKT signaling through inhibition of the lipid phosphatase PTEN. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2009;50:5339–5347. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan E, Ding XQ, Saadi A, Agarwal N, Naash MI, Al-Ubaidi MR. Expression of cone-photoreceptor-specific antigens in a cell line derived from retinal tumors in transgenic mice. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2004;45:764–768. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Gong J, Yoshida T, Eberhart CG, Xu Z, Kombairaju P, Sporn MB, Handa JT, Duh EJ. Nrf2 has a protective role against neuronal and capillary degeneration in retinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Free radical biology & medicine. 2011;51:216–224. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsbie DS, Yang Z, Ge Y, et al. Functional genomic screening identifies dual leucine zipper kinase as a key mediator of retinal ganglion cell death. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:4045–4050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211284110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Gong J, Maiti D, Vong L, Wu L, Schwarz JJ, Duh EJ. MEF2C ablation in endothelial cells reduces retinal vessel loss and suppresses pathologic retinal neovascularization in oxygen-induced retinopathy. The American journal of pathology. 2012;180:2548–2560. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Wei Y, Gong J, et al. NRF2 plays a protective role in diabetic retinopathy in mice. Diabetologia. 2014;57:204–213. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-3093-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota H, Narayanan SP, Zhang W, et al. Neuroprotection from retinal ischemia/reperfusion injury by NOX2 NADPH oxidase deletion. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2011;52:8123–8131. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweier JL, Flaherty JT, Weisfeldt ML. Direct measurement of free radical generation following reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1987;84:1404–1407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.5.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.