Abstract

Objectives

This article describes physical function in Puerto Rican older adults and examines associations between health status and physical function. It also assesses relationships between physical function and disability.

Method

This study uses a cross-sectional study of Puerto Ricans 45 to 75 years in Boston (N = 1,357). Measures included performance-based physical function (handgrip strength, walking speed, balance, chair stands, foot tapping), health conditions (obesity, diabetes, depressive symptomatology, history of heart disease, heart attack, stroke, and arthritis), and self-reported disability (activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living).

Results

Older women (60-75 years) had the poorest physical function. Poor physical function was associated with obesity, diabetes, depression, history of heart attack, stroke, and arthritis, after adjusting for age, sex, education, income, and lifestyle (p < .05). Physical function and disability were correlated (p < .01).

Discussion

Health status among Puerto Ricans appears to contribute to poor physical function. Targeted interventions to improve strength, endurance, and balance are needed to combat physical frailty and its consequences in this population.

Keywords: Puerto Ricans older adults, physical function, physical frailty, health status

Poor physical function is the hallmark of physical frailty and an important component in the disablement process (Nagi, 1976). Nagi (1976) described the epidemiology of this process as a sequence of events starting with acquisition of pathology (disease, injury), followed by impairment and poor physical function (mobility and balance) leading to disability (Nagi, 1976). Often, self-reported disability is used to predict adverse outcomes, institutionalization, and death (Guralnik, Ferrucci, Simonsick, Salive, & Wallace, 1995). However, performance-based measures of physical function can objectively capture physical abilities and can identify declines in function and impairment in people who may not yet be disabled. In fact, data from the Cardiovascular Health Study in well-functioning older community-dwelling adults showed that 7% of these individuals have poor physical function and are therefore considered frail (Fried et al., 2001).

Factors associated with poor physical function include age-related declines in muscle mass and muscle function (or sarcopenia; Rosenberg, 1997), advanced age, female sex, physical inactivity, low socioeconomic status (Fried et al., 2001), and minority status (Baldwin, 2003). Hispanics, the fastest growing population in the United States, bear a disproportionate burden of disability (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2004). Data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) in persons above 60 years of age showed significantly higher prevalence of self-reported disability among non-Hispanic Black and Mexican American men and women than in non-Hispanic Whites (NHW; Ostchega, Harris, Hirsch, Parsons, & Kington, 2000). Most recently, data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) showed that adults with both mobility limitations (defined as self-reported difficulty walking and moving around) and minority status experienced the greatest disparities in disability. This includes difficulty with activities of daily living (ADL; 42.7%) and with instrumental activities of daily living (IADL; 27.7%; Jones & Sinclair, 2008). The ancestral origin self-reported by Hispanics in the NHIS included Mexican (53%), Puerto Rican (12%), Cuban (7%), and Other (28%; Jones & Sinclair, 2008).

Most epidemiologic information on any one component of the disablement process among Hispanics has focused on Mexican Americans, due to their majority as a subgroup. However, evidence suggests that health outcomes vary significantly by Hispanic ethnic subgroup (Barcelo, Gregg, Pastor-Valero, & Robles, 2007). We are particularly interested in the Puerto Rican population living in the Northeast part of the United States because it is the largest Hispanic subgroup of that region (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004) with documented health disparities (Baldwin, 2003). National data show that 21% of older Puerto Ricans reported having an activity limitation, compared with 15% of Cuban or Mexican Americans (Hajat, Lucas, & Kington, 2000). In a representative sample of Puerto Rican adults 60 years of age and older living in Massachusetts, 73% of Puerto Rican women reported difficulty with at least one ADL, compared to 64% of NHW women living in the same neighborhoods (Tucker, Falcon, Bianchi, Cacho, & Bermudez, 2000). This important finding, however, leads to the question of whether subjective reporting of one’s physical abilities may be influenced by self-perceived general health, access to health care, and/or health inequalities—issues that have been shown to particularly influence Mexican American (Angel, Angel, & Markides, 2003) and African American (Ferraro & Koch, 1994) populations. Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to (a) describe physical function (ascertained by objective performance-based measures) in Puerto Rican women and men between 45 to 75 years of age, (b) examine the independent associations between health status and physical function in this population, and (c) determine the relationships between measured physical function and self-reported disability.

Method

Study Population

This analysis used data from the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal study funded by the National Institutes of Health as part of the Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities. Detailed study methods are reported elsewhere (Tucker et al., 2010). Briefly, participants were recruited from the Greater Boston and surrounding areas using door-to-door enumeration to identify Hispanics between 45 to 75 years of age. More than 17,250 doors were approached and visited at least three times and up to six times on different days of the week, weekends, and at varying times of day in an attempt to reach those who were not at home during initial enumeration. Households with at least one eligible adult were identified and one participant per qualified household was invited to participate. The majority (80.4%) of participants were identified through door-to-door enumeration. However, participants were also identified during major community festivals/ fairs and events (8.9%), through referrals from participants and ineligible individuals (6.1%), and through calls to the study office from flyers distributed at community locations (4.6%). Individuals who were unable to answer questions due to serious health conditions planned to move away from the area within 2 years or who had a low mini mental state examination (MMSE) score (≤10) were excluded from participation. A total of 1,742 Puerto Rican adults (45-75 years) agreed to participate, 9 were excluded due to low MMSE, 14 dropped out, 37 were lost to follow up, and 5 failed to complete the interview despite continued agreement to do so. A total of 1,432 completed the interview. Of these, 1,357 participants had double data entered and cleaned data and were included in this analysis. Written informed consent approved by the Institutional Review Board at Tufts Medical Center was obtained in the language of preference (Spanish or English) before study participation.

Measures

Physical function, the main outcome of this investigation, refers to objective performance-based measures of physiological domains, including strength, balance, mobility, and motor coordination (Guralnik et al., 1995; Seeman et al., 1994). Poor physical function refers to impairment or inability to perform any of these physiological domains (Ferrucci et al., 2004). Physical disability was ascertained with the ADL (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffee, 1963) and the IADL (Lawton & Brody, 1969) questionnaires.

Performance-based measures of physical function include the following: Handgrip strength was measured using a dynamometer (Smedley Hand Dynamometer, Stoelting Co, Wood Dale, IL). Three trials on each hand were performed and the average of these measures from the dominant hand was used for analysis. Lower-extremity physical function was determined by four timed tests, including walking, standing balance, chair stands, and foot-tapping coordination, adapted from the MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging (Guralnik et al., 1995; Seeman et al., 1994). Two timed 10-ft walking tests were performed, first at a normal and then at a faster pace. Participants needing more than 15 s to complete the 10-ft walk or unable to walk were assigned a value of 16 s. For balance, participants were asked to maintain their feet in the tandem position for 10 s with their eyes open. They were given a score of 1 if they could hold the tandem position for 10 s or 0 if they were unable. For the timed chair stand, participants were asked to fold their arms across their chest and stand up from a chair once. If they successfully rose from the chair, they were asked to stand up and sit down five times as quickly as possible and the time this took in seconds was recorded. Participants whose time score was >30 s, and those who were unable to do five chair stands, were assigned a value of 31 s. The foot-tapping coordination test assessed the time in seconds it took to complete 10 foot taps (tapping one foot back and forth 10 times between two circles 12 in apart on a mat placed in front of the participant while seated). The test was assessed separately for each foot and the slowest time was used for analysis. Participants unable to complete this task with either foot, or those needing more than 30 s to complete this task, were assigned a value of 31 s.

Poor physical function was defined by the following impairments or inabilities: handgrip strength impairment—strength measures falling within the lower two tertiles (ascertained separately for men and women; Rantanen et al., 2003); poor walking speed—slowest time walked equivalent to <0.4 m/s (Rolland et al., 2004); poor balance—a score <10 s while maintaining a tandem stand; poor chair stand time—a score ≥11.2 s (Guralnik et al., 1995; Seeman et al., 1994); poor foot tapping coordination—a score ≥9.8 s (above the median time it took to complete the 10-ft taps).

Self-reported ability to perform 12 ADL tasks (Katz et al., 1963) and 6 IADL tasks (Lawton & Brody, 1969) were ascertained from a series questions, each with four possible responses depending on the level of difficulty (from 0 = for no difficulty, 1 = for some difficulty, 2 = for a lot of difficulty, and 3 = unable to do). Summary scores were also calculated separately for ADL and IADL from the sum of the responses on each questionnaire. Best and worst possible summary scores for ADL are 0 and 36 and for IADL 0 and 18, respectively.

Health status was ascertained by the prevalence of health conditions as follows: obesity—body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2 (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI], 2001); abdominal obesity—waist circumference >88 cm in men and >102 cm in women (NHLBI, 2001); type 2 diabetes— fasting plasma glucose ≥126mg/dl or use of diabetes medications (American Diabetes Association, 2002); depressive symptomatology—score ≥16 on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Questionnaire (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). Finally, history of heart disease, heart attack, stroke, and arthritis were ascertained by self-report in response to questions asking whether they have ever been diagnosed with each condition by a physician.

Covariates

Age, sex, education, poverty level, smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity were assessed by self-report. Poverty status was determined using the yearly poverty thresholds released by the U.S. Census Bureau (U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). Each participant’s total annual household income was compared to the threshold, based on the age of the head of household, participant’s family size, and year of interview. If total household income was less than this threshold, the participant was considered to live in poverty. Smoking was categorized past or current versus never. Alcohol consumption was classified as nondrinker or light (<1 drink/day), moderate (up to 1 drink/day for women and 2 drinks/day for men), or heavy drinkers (>2 drinks/day; Krauss et al., 2000). Physical activity was estimated using a modified version of the Harvard Alumni Physical Activity Questionnaire (Paffenbarger, Hyde, Wing, & Hsieh, 1986). Participants were asked for the hours per day (week and weekend days) spent in sleep, sedentary (sitting), and light, moderate, and heavy (vigorous) activities, each multiplied by the weighting factors 1.0, 1.1, 1.5, 2.4, and 5.0, respectively. Tertiles of physical activity levels from none/ little (lowest tertile) to some (highest tertile) activity were calculated from physical activity scores. These tertiles were used for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) with a two-tailed p ≤ .05 for statistical significance. Data are presented as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Participant characteristics, performance-based physical function measures, and self-reported ADL and IADL disability per age group (45-59 and 60-75 years) were compared by sex. Comparisons were made using t tests for normally distributed continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Associations between physical function measures and health conditions were assessed by multivariable regression models using binary logistic regression for handgrip strength impairment (strength in kilograms in the bottom two tertiles of performance), poor walking speed (<0.4 m/s), and poor balance (tandem stand maintained <10 s) or by linear regression for the time it took to raise from a chair five times and to perform the foot-tapping coordination test, both measured in seconds. Each model was adjusted for covariates (age group, sex, education, poverty level, tertiles of physical activity level from none/little [lowest tertile] to some [highest tertile], smoking status [current, past, never], and alcohol consumption [moderate, heavy, light/nondrinker]). Covariates were forced into each model. Health conditions (obesity, abdominal obesity, type 2 diabetes, depressive symptomatology, heart disease, heart attack, stroke, and arthritis) were entered into a forward stepwise regression if they met the .05 significance level. Finally, we examined the relationship between performance-based physical function measures (handgrip strength in kg and 10-ft walk, poor balance, chair stand, and foot taps [all in seconds]) and self-reported ADL and IADL disability summary scores by age group, using partial correlation coefficients adjusted for covariates, as listed above.

Results

Participant characteristics

Mean ages were 57.4 ± 7.5 years for women and 56.7 ± 7.9 years for men and 70% of the sample were women. Compared to men, more women in the younger (45-59 years) and older (60-75 years) age groups fell below the poverty level and fewer of them reported past or current smoking history or moderate or heavy alcohol consumption (Table 1). Physical activity scores in this sample ranged from 24.3 (none/little) to 62.6 (some) with approximately 50% reporting none or little physical activity level, as shown by scores <30. Mean physical activity scores were 31 ± 4 for women and 32 ± 6 for men. Older women were significantly more sedentary than men in the same age group (Table 1). Health status was compromised in this population, as seen by the high prevalence of several health conditions. Prevalent obesity (overall or abdominal), depressive symptomatology, and arthritis were significantly higher in younger and older women than their men counterparts, whereas heart attack was significantly higher in younger men than younger women (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Sex

| Characteristic | Women (n = 956) | Men (n = 401) | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years; %) | .56 | ||

| 45-59 | 69.9 | 30.1 | |

| 60-75 | 71.4 | 28.6 | |

| Education (% ≤eighth grade) | |||

| 45-59 | 39.3 | 34.8 | .22 |

| 60-75 | 65.5 | 61.0 | .33 |

| Below poverty level (%) | |||

| 45-59 | 58.2 | 49.6 | .03 |

| 60-75 | 68.1 | 52.5 | .001 |

| Smoking (%) | |||

| 45-59 | <.0001 | ||

| 60-75 | <.0001 | ||

| Never | |||

| 45-59 | 48.5 | 29.4 | |

| 60-75 | 57.2 | 33.8 | |

| Past | |||

| 45-59 | 25.8 | 32.3 | |

| 60-75 | 30.0 | 38.6 | |

| Current | |||

| 45-59 | 25.7 | 38.3 | |

| 60-75 | 12.8 | 27.6 | |

| Alcohol consumption (%) | |||

| 45-59 | <.0001 | ||

| 60-75 | <.0001 | ||

| None/light | |||

| 45-59 | 59.0 | 48.2 | |

| 60-75 | 75.9 | 52.5 | |

| Moderate | |||

| 45-59 | 36.7 | 35.5 | |

| 60-75 | 22.2 | 36.4 | |

| Heavy | |||

| 45-59 | 4.3 | 16.3 | |

| 60-75 | 1.9 | 11.2 | |

| Physical activity tertile (%)b | |||

| 45-59 | .20 | ||

| 60-75 | .02 | ||

| Lowest | |||

| 45-59 | 28.3 | 25.5 | |

| 60-75 | 46.5 | 33.3 | |

| Mid | |||

| 45-59 | 33.3 | 29.5 | |

| 60-75 | 34.0 | 38.8 | |

| Highest | |||

| 45-59 | 38.4 | 45.0 | |

| 60-75 | 19.6 | 27.9 | |

| Health conditions (%) | |||

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) | |||

| 45-59 | 61.7 | 44.0 | <.0001 |

| 60-75 | 62.4 | 42.5 | <.0001 |

| Abdominal obesity (waist circumference > reference)c | |||

| 45-59 | 79.7 | 43.0 | <.0001 |

| 60-75 | 84.1 | 45.6 | <.0001 |

| Type 2 diabetesd | |||

| 45-59 | 33.9 | 37.2 | .37 |

| 60-75 | 50.7 | 45.0 | .25 |

| Depressive symptomatologye | |||

| 45-59 | 67.9 | 50.0 | <.0001 |

| 60-75 | 58.8 | 43.5 | .002 |

| Heart diseasef | |||

| 45-59 | 11.8 | 10.4 | .55 |

| 60-75 | 16.6 | 15.0 | .64 |

| Heart attack | |||

| 45-59 | 5.3 | 9.2 | .04 |

| 60-75 | 11.8 | 15.0 | .32 |

| Stroke | |||

| 45-59 | 2.4 | 0.8 | .12 |

| 60-75 | 5.5 | 9.5 | .09 |

| Arthritis | |||

| 45-59 | 48.6 | 27.9 | <.0001 |

| 60-75 | 69.2 | 46.3 | <.0001 |

Sex differences in participant characteristics by age group were tested using chi-square.

Tertiles of physical activity level from none/little (lowest tertile) to some (highest tertile).

Waist circumference >88 cm for men and >102 cm for women (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2001).

American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines (American Diabetes Association, 2002).

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression questionnaire (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). A score ≥16 is considered as depressive symptomatology.

Self-report.

Performance-based measures of physical function

Both younger and older women had significantly poorer handgrip strength (<22 kg; Rantanen, 2003) and walking speed than men in the same age groups. In addition, a significantly greater proportion of older women had poor balance, and, on average, older women took longer to perform the chair stand and foot-tapping tests than older men (Table 2).

Table 2.

Physical Function Among Puerto Rican Older Adults by Sex

| Variable | Women (n = 956) | Men (n = 401) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Handgrip (kg)a | |||

| 45-59 | 20.8 ± 6.1 | 35.9 ± 8.6 | <.0001 |

| 60-75 | 18.5 ± 5.1 | 31.9 ± 7.8 | <.0001 |

| Handgrip strength impairment (kg)a,b | |||

| 45-59 | 16.9 ± 4.0 | 30.4 ± 5.9 | <.0001 |

| 60-75 | 16.6 ± 4.0 | 29.2 ± 5.9 | <.0001 |

| 10-ft walk (sec)a | |||

| 45-59 | 7.9 ± 2.4 | 7.3 ± 2.2 | .002 |

| 60-75 | 9.2 ± 2.8 | 8.3 ± 2.8 | .001 |

| Poor walking speed (<0.4 m/s) % | |||

| 45-59 | 42.5 | 33.8 | .02 |

| 60-75 | 66.8 | 46.8 | <.0001 |

| Poor balance (<10 s) % | |||

| 45-59 | 15.8 | 12.8 | .26 |

| 60-75 | 30.9 | 22.5 | .05 |

| Chair stand time (s)a | |||

| 45-59 | 14.1 ± 5.4 | 13.8 ± 5.4 | .43 |

| 60-75 | 16.2 ± 5.9 | 15.0 ± 6.1 | .05 |

| Foot tapping (s)a | |||

| 45-59 | 9.4 ± 5.6 | 9.1 ± 6.1 | .45 |

| 60-75 | 12.0 ± 6.9 | 10.3 ± 6.0 | .006 |

Note: Sex differences in physical function and disability variables by age group were tested using t test for continuous variables or chi-square for categorical variables.

M ± SD.

Handgrip strength impairment was defined as strength following in the bottom two tertiles and ascertained separately for men and women. Handgrip strength impairment cutoff values were ≤37.9 kg for men and <22.5 kg for women. Mean values shown are for those who are impaired.

Associations between health status and physical function

Participants with depressive symptomatology, stroke, or arthritis were significantly more likely to have impaired handgrip muscle strength than their counterparts, independently of sociodemographics and lifestyle factors known to be associated with impairment. In contrast, however, greater abdominal obesity was associated with less likelihood of low handgrip strength (Table 3). Obesity and depressive symptomatology were significantly associated with likelihood of having mobility disability. Poor balance was associated with obesity and history of heart attack, stroke, and arthritis. Obesity, depressive symptomatology, history of heart attack, and arthritis were positively correlated with longer chair stand times, suggestive of poor performance. Finally, participants with diabetes and depressive symptomatology were more likely to have poor foot tap coordination than those without these respective conditions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of Health Status With Physical Function Among Puerto Rican Older Adults

| Low handgrip strength (bottom two tertiles) |

Low walking speed (<0.4 m/s) |

Poor balance (<10 s) |

Chair stand time (s) |

Foot-tapping time (s) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 1,216) |

(n = 1,190) |

(n = 1,232) |

(n = 1,171) |

(n = 1,215) |

||||||

| Health conditions | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | Beta estimate |

SE | Beta estimate |

SE |

| Obesity | 1.75**** | 1.35, 2.28 | 1.78*** | 1.28, 2.48 | 1.53**** | 0.33 | ||||

| Abdominal obesity | 0.51**** | 0.37, 0.70 | ||||||||

| Type 2 diabetes | 1.23*** | 0.35 | ||||||||

| Depressive symptomatology |

1.46** | 1.11, 1.90 | 1.63*** | 1.25, 2.13 | 0.81* | 0.33 | 0.88* | 0.35 | ||

| Heart attack | 1.96** | 1.23, 3.11 | 1.84** | 0.57 | ||||||

| Stroke | 3.61* | 1.24, 10.53 | 4.56**** | 2.33, 8.92 | ||||||

| Arthritis | 1.61*** | 1.23, 2.10 | 1.56** | 1.13, 2.16 | 1.29*** | 0.34 | ||||

Note: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. OR and 95% CI are shown, except for continuous variables of chair stand and foot-tapping coordination for which beta estimates and standard errors are shown. Handgrip strength impairment was defined as strength following in the bottom two tertiles and ascertained separately for men and women. Handgrip strength impairment cutoff values were ≤37.9 kg for men and <22.5 kg for women. Multivariable binary logistic regression (impairment, mobility disability, and poor balance) or linear regression (chair stand and foot tapping coordination) models adjusted for age group (45-59 vs. 60-75 years), sex, education, poverty level, tertiles of physical activity level from none/little (lowest tertile) to some (highest tertile), smoking status (current, past, never), and current alcohol consumption (moderate, heavy, light/nondrinker), with each health condition entered in a forward stepwise manner if they met the .05 significance level.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

p < .0001.

ADL and IADL disability

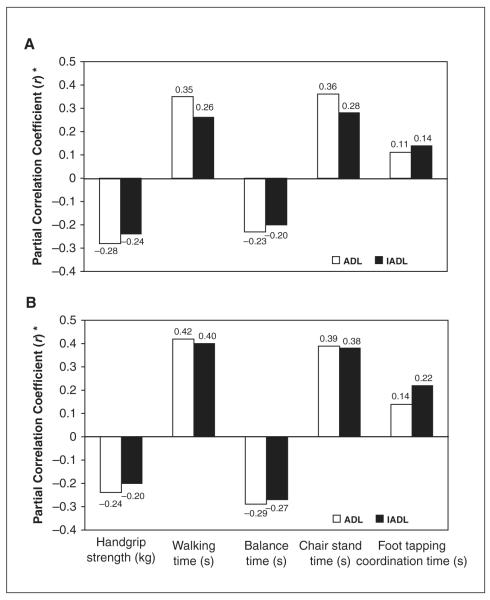

ADL summary scores were significantly higher in younger and older women than in their male counterparts, whereas IADL summary scores were significantly higher for older women only. A greater proportion of younger and older women reported some difficulty in performing ADLs and IADLs compared to men in the same age groups. Interestingly, slightly more young men than young women reported inability to perform ADLs, although these percentages were very small (Table 4). Poor physical function was strongly and significantly associated with self-reported ADL and IADL disability for both younger and older adults (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Self-Report Physical Disability Among Puerto Rican Older Adults by Sex

| Variablea | Women (n = 951) | Men (n = 398) | p valueb |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADL level of difficulty (%) | |||

| 45-59 | <.0001 | ||

| 60-75 | <.0001 | ||

| No difficulty | |||

| 45-59 | 27.4 | 45.0 | |

| 60-75 | 19.7 | 33.8 | |

| Some difficulty | |||

| 45-59 | 67.2 | 49.0 | |

| 60-75 | 66.7 | 57.8 | |

| A lot of difficulty | |||

| 45-59 | 5.3 | 5.2 | |

| 60-75 | 13.1 | 2.7 | |

| Unable to do | |||

| 45-59 | 0.2 | 0.8 | |

| 60-75 | 0.6 | 0.7 | |

| ADL summary scorec | |||

| 45-59 | 3.8 ± 4.6 | 3.0 ± 5.0 | .02 |

| 60-75 | 5.5 ± 5.9 | 2.9 ± 4.7 | <.0001 |

| IADL level of difficulty (%) | |||

| 45-59 | .006 | ||

| 60-75 | <.0001 | ||

| No difficulty | |||

| 45-59 | 52.0 | 64.9 | |

| 60-75 | 41.5 | 64.6 | |

| Some difficulty | |||

| 45-59 | 42.6 | 29.9 | |

| 60-75 | 46.2 | 29.9 | |

| A lot of difficulty | |||

| 45-59 | 5.1 | 4.8 | |

| 60-75 | 10.4 | 4.1 | |

| Unable to do | |||

| 45-59 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| 60-75 | 1.9 | 1.4 | |

| IADL summary scorec | |||

| 45-59 | 1.6 ± 2.5 | 1.4 ± 2.6 | .27 |

| 60-75 | 2.6 ± 3.5 | 1.3 ± 2.8 | <.0001 |

Note: ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living.

Level of difficulty (0 = no difficulty, 1 = some difficulty, 2 = a lot of difficulty, and 3 = unable to do) to perform 12 ADL and 6 IADL were ascertained. Summary scores represent the sum of the responses on each questionnaire. Best and worst possible summary scores for ADL are 0 and 36, and for IADL 0 and 18, respectively.

Sex differences in ADL and IADL level of difficulty and summary scores by age group were tested using chi-square for categorical variables and t test for continuous variables, respectively.

M ± SD.

Figure 1.

Partial correlations between measures of physical function and self-reported ADL (n = 1,118) and IADL (n = 1,119) summary scores are shown by age group (A = 45-59 years and B = 60-75 years of age)

ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living. Correlations were adjusted for sex, education, poverty level, tertiles of physical activity level from none/little (lowest tertile) to some (highest tertile), smoking status (current, past, never), and current alcohol consumption (moderate, heavy, light/nondrinker). Higher handgrip strength in kg and balance time in second, and lower times in second for all other measures indicate better performance in physical function. *All p values were <.01.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, Puerto Rican women between 60 and 75 years of age exhibited the poorest physical function. This was shown by impaired handgrip strength and poor lower extremity physical function, as determined by a slow walking speed, poor balance, and poor performance in chair stands and foot-tapping coordination. Performance-based measures of physical function were significantly associated with the presence of prevalent health conditions, including obesity (overall and abdominal), type 2 diabetes, depressive symptomatology, and history of heart attack, stroke, or arthritis, independently of sociodemographic and lifestyle factors known to affect physical function. Performance-based measures of physical function were strongly and significantly correlated with self-reported ADL and IADL disability.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe objective performance-based measures of physical function in Puerto Rican older adults. Impairment in the physiological domains of physical function, including strength, balance, mobility, and motor coordination, is an important intermediary component of the disablement process (Nagi, 1976). We measured these domains and found clear evidence of poor physical function, suggestive of frailty in Puerto Rican older adults. Specifically, handgrip strength impairment was shown to be markedly reduced among younger and older women, with strength measures below the recommended 22 kg seen in other populations (Rantanen et al., 2003). Adequate muscle strength translates to reserve capacity needed to perform daily motor tasks such as walking or rising from a chair (Fried et al., 2001). Low levels of handgrip strength have been shown to predict poor physical function and subsequent disability in healthy older adults 45 to 68 years of age 25 years later (Rantanen et al., 1999). In addition, older people with poor lower extremity physical function are more likely to become institutionalized than those with better function (Fried et al., 2001; Guralnik et al., 1994; Guralnik et al., 1995; Guralnik et al., 2000). Recent data from the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study showed that poor lower extremity function was associated with increased hospitalization and death in a well-functioning nondisabled population of persons aged 70 to 79 years (Cesari et al., 2009). We found high prevalence of poor walking speed in both younger and older women, whereas poor balance and ability to perform chair stands and foot taps were primarily observed in older women compare to men in the same age groups. Mobility disabilities in older adults are considered early markers of the disablement process and predictive of severe disability, institutionalization, and mortality (Guralnik et al., 2000). Studies in middle-aged adults have also shown that mobility difficulties are present at an earlier age (Iezzoni, McCarthy, Davis, & Siebens, 2001; Melzer, Gardener, & Guralnik, 2005). More importantly, these studies have shown that health conditions commonly associated with mobility limitations are similar in both middle age and older groups.

We found that prevalent health conditions in this population represented a significant burden to their physical functioning, independently of sociodemographic and lifestyle factors known to affect functional abilities. This is of significance because acquisition of pathology is an upstream component of the disablement process (Nagi, 1976). Our findings of associations between prevalent health conditions and performance-based measures of physical function support those seen in the Massachusetts Hispanic Elders Study. In that study, self-reported ADL scores were significantly associated with obesity, diabetes, depressive symptomatology, and history of stroke, heart disease, and arthritis in Puerto Rican elders (Tucker et al., 2000). The association of obesity and physical disability has been observed in the general population and in other Hispanic subgroups (Weil et al., 2002). Men 60 to 79 years of age in the upper range of the overweight category were found to be 50% more likely to report mobility disability than normal weight men in these age range and the odds of obese elderly men were two times greater than those with normal weight (Goya Wannamethee, Gerald Shaper, Whincup, & Walker, 2004). This is consistent with reports showing twice the risk of mobility-related disability for men in the highest quintile of body weight or fat mass compared to the lowest quintile (Visser et al., 1998). Given the expected increase in life expectancy and the steady increase in the prevalence of obesity, interventions aimed at reducing this epidemic are needed to reduce its effect on functional decline and disability. Our finding of lower risk of low handgrip strength with abdominal obesity was unexpected and requires further investigation. It should be noted that this finding was seen when all health conditions were candidates in a forward regression model. In addition to abdominal obesity, depressive symptomatology and history of stroke and arthritis were associated with handgrip strength impairment. However, unlike abdominal obesity, the presence of these factors resulted in an increased risk of handgrip strength impairment.

Arthritis and depressive symptomatology were also associated with impairment and poor lower-extremity physical function in the present study. Self-reported arthritis is highly prevalent among Hispanic and Mexican American elderly and represents a significant cause of disability in this ethnic group (Song et al., 2007). Arthritis affects the musculoskeletal system and the ability to perform tasks expected of an independent person. However, ways to reduce musculoskeletal impairment to improve function due to arthritis remain a challenge. Depressive symptomatolgy has been reported to predict decline in physical function in community-dwelling older adults (Penninx et al., 1998). Data from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES; Vera et al., 1991) and the Massachusetts Hispanic Elders Study (Falcon & Tucker, 2000) underline the high prevalence of depressive symptomatology among Puerto Rican older adults compared to non-Hispanic White older adults. Depressive symptomatology in Puerto Ricans may be associated with health care access (Rodriguez-Galan & Falcon, 2009) as well as with psychosocial distress (Falcon, Todorova, & Tucker, 2009). Finally, history of heart attack and stroke were significantly associated with poor lower extremity physical function. These findings emphasize the need to better understand the multiple pathologies that may lead to impairment and functional decline, and subsequent disability in older adults with an increased burden of health conditions like the Puerto Rican population.

A limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which precludes our ability to examine the continuum of the disablement process (Nagi, 1976). However, the observed high prevalence of poor physical function, a component of this process, is of concern particularly in this rapidly growing, under-studied minority population in the United States. A major strength of this study is the inclusion of a large community-dwelling Puerto Rican older adult population for which performance-based measures of physical function were described for the first time. Furthermore, the strong relationships we found between performance-based measures of physical function and self-reported ADL and IADL disability are similar to those reported in other populations of community-dwelling older adults (Jette, Assmann, Rooks, Harris, & Crawford, 1998). These associations suggest that components of the disablement process upstream from overt disability develop as early as in middle age and that reverting poor physical function may contribute to prevention of disability progression.

In conclusion, poor physical function and self-reported ADL and IADL disability were prevalent and highly correlated in this Puerto Rican population of older adults. Younger and older women showed the poorest physical function. Prevalent health conditions (obesity, type 2 diabetes, depressive symptomatology, heart attack, stroke, and arthritis) were independently associated with poor physical function. Targeted interventions aimed at improving domains of physical function (strength, balance, mobility, and motor coordination) and managing prevalent health conditions are needed to improve physical function and prevent frailty and disability in this high risk population.

Acknowledgments

Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture or any of the funding sources. The findings from this analysis were presented in part in the 2007 Experimental Biology Meeting in Washington, DC.

Funding The authors disclosed that they received the following support for their research and/or authorship of this article: work supported by the Boston Puerto Rican Center on Population Health and Health Disparities, National Institute of Aging (NIH, P01-AG02339); the General Clinical Research Center at Tufts Medical Center in Boston, NIH Division of Research Resources (M01-RR00054); and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service under agreement 58-1950-7-707.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- American Diabetes Association Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:S5–S20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angel R, Angel J, Markides K. La Salud Física y Mental de los Mexicanos Migrantes Mayores en los Estados Unidos. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública; Cuernavaca, Morelos, México: 2003. Mental and physical health among elderly Mexican immigrants in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin DM. Disparities in health and health care: Focusing efforts to eliminate unequal burdens. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing. 2003;8(1):2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcelo A, Gregg EW, Pastor-Valero M, Robles SC. Waist circumference, BMI and the prevalence of self-reported diabetes among the elderly of the United States and six cities of Latin America and the Caribbean. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2007;78:418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health disparities experienced by racial/ethnic minority populations. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2004;53(33):755. [Google Scholar]

- Cesari M, Kritchevsky S, Newman A, Simonsick E, Harris T, Penninx B, et al. Added value of physical performance measures in predicting adverse health-related events: Results from the health, aging and body composition study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57:251–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon LM, Todorova I, Tucker KL. Social support, life events, and psychological distress among the Puerto Rican population in the Boston area of the United States. Aging and Mental Health. 2009;13:863–873. doi: 10.1080/13607860903046552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon LM, Tucker KL. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among Hispanic elders in Massachusetts. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2000;55:S108–S116. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.2.s108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro K, Koch J. Religion and health among Black and White adults: Examining social support and consolation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1994;33:362–375. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, Fried LP, Cutler GB, Jr., Walston JD. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: A consensus report. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. Journals of Ger-ontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goya Wannamethee S, Gerald Shaper A, Whincup PH, Walker M. Overweight and obesity and the burden of disease and disability in elderly men. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders. 2004;28:1374–1382. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, Leveille SG, Markides KS, Ostir GV, et al. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: Consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2000;55:M221–231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332:556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49:M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajat A, Lucas JB, Kington R. Health outcomes among Hispanic subgroups: Data from the National Health Interview Survey, 1992-95. Advance Data. 2000;310(310):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni LI, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Siebens H. Mobility difficulties are not only a problem of old age. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:235–243. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016004235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jette AM, Assmann SF, Rooks D, Harris BA, Crawford S. Interrelationships among disablement concepts. Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 1998;53:M395–M404. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.5.m395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones GC, Sinclair LB. Multiple health disparities among minority adults with mobility limitations: San application of the ICF framework and codes. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2008;30:901–915. doi: 10.1080/09638280701800392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffee MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1963;185:914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, Appel LJ, Daniels SR, Deckelbaum RJ, et al. AHA Dietary Guidelines: Revision 2000: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000;102:2284–2299. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzer D, Gardener E, Guralnik JM. Mobility disability in the middle-aged: Cross-sectional associations in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age and Ageing. 2005;34:594–602. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagi SZ. An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly: Health and Society. 1976;54:439–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute . Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III, or ATP III) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ostchega Y, Harris TB, Hirsch R, Parsons VL, Kington R. The prevalence of functional limitations and disability in older persons in the US: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48:1132–1135. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paffenbarger RS, Hyde RT, Wing AL, Hsieh CC. Physical activity, all-cause mortality, and longevity of College Alumni. New England Journal of Medicine. 1986;314:605–613. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198603063141003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BW, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Deeg DJ, Wallace RB. Depressive symptoms and physical decline in community-dwelling older persons. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;279:1720–1726. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A new self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T. Muscle strength, disability and mortality. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 2003;13:3–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Foley D, Masaki K, Leveille S, Curb JD, et al. Midlife hand grip strength as a predictor of old age disability. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:558–560. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen T, Volpato S, Ferrucci L, Heikkinen E, Fried LP, Guralnik JM. Handgrip strength and cause-specific and total mortality in older disabled women: Exploring the mechanism. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:636–641. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0579.2003.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Galan MB, Falcon LM. Perceived problems with access to medical care and depression among older Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, other Hispanics, and a comparison group of non-Hispanic Whites. Journal of Aging and Health. 2009;21:501–518. doi: 10.1177/0898264308329015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland YM, Cesari M, Miller ME, Penninx BW, Atkinson HH, Pahor M. Reliability of the 400-m usual-pace walk test as an assessment of mobility limitation in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:972–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. Journal of Nutrition. 1997;127(Suppl. 5):S990–S991. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.5.990S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Charpentier PA, Berkman LF, Tinetti ME, Guralnik JM, Albert M, et al. Predicting changes in physical performance in a high-functioning elderly cohort: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49:M97–108. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.3.m97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Chang HJ, Tirodkar M, Chang RW, Manheim LM, Dunlop DD. Racial/ethnic differences in activities of daily living disability in older adults with arthritis: A longitudinal study. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007;57:1058–1066. doi: 10.1002/art.22906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker KL, Falcon LM, Bianchi LA, Cacho E, Bermudez OI. Self-reported prevalence and health correlates of functional limitation among Massachusetts elderly Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and non-Hispanic White neighborhood comparison group. Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2000;55:M90–M97. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.2.m90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker KL, Noel SE, Mattei J, Collado B, Mendez J, Nelson J, et al. The Boston Puerto Rican Health Study, a longitudinal cohort study on health disparities in Puerto Rican adults: Challenges and opportunities. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(107) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-107. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-1110-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau [Retrieved April 7, 2010];U.S.interim projections by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin. 2004 from http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj.

- U.S. Census Bureau . Poverty thresholds. U.S. Department of Commerce; [Retrieved April 7, 2010]. 2009. from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/threshld.html. [Google Scholar]

- Vera M, Alegria M, Freeman D, Robles RR, Rios R, Rios CF. Depressive symptoms among Puerto Ricans: Island poor compared with residents of the New York City area. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1991;134:502–510. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser M, Langlois J, Guralnik JM, Cauley JA, Kronmal RA, Robbins J, et al. High body fatness, but not low fat-free mass, predicts disability in older men and women: The Cardiovascular Health Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1998;68:584–590. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.3.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil E, Wachterman M, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, O’Day B, Iezzoni LI, et al. Obesity among adults with disabling conditions. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1265–1268. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.10.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]