Abstract

Nearly 20% of the 208 million pregnancies that occur annually are aborted. More than half of these (21.6 million) are unsafe, resulting in 47,000 abortion-related deaths each year. Accurate reports on the prevalence of abortion, the conditions under which it occurs, and the experiences women have in obtaining abortions are essential to addressing unsafe abortion globally. It is difficult, however, to obtain accurate and reliable reports of attitudes and practices given that abortion is often controversial and stigmatized, even in settings where it is legal. To improve the understanding and measurement of abortion, specific considerations are needed throughout all stages of the planning, design, and implementation of research on abortion: Establishment of strong local partnerships, knowledge of local culture, integration of innovative methodologies, and approaches that may facilitate better reporting. This paper draws on the authors’ collaborative research experiences conducting abortion-related studies using clinic- and community-based samples in five diverse settings (Poland, Zanzibar, Mexico City, the Philippines, and Bangladesh). The purpose of this paper is to share insights and lessons learned with new and established researchers to inform the development and implementation of abortion-related research. The paper discusses the unique challenges of conducting abortion-related research and key considerations for the design and implementation of abortion research, both to maximize data quality and to frame inferences from this research appropriately.

Introduction

Approximately 35% of the 208 million pregnancies that occurred worldwide in 2008 (74 million) were unintended, and 41 million were aborted (Singh, Wulf, Hussain, Bankole, & Sedgh, 2009). More than half of these abortions (21.6 million) were unsafe, resulting in 47,000 abortion-related deaths (Shah & Ahman, 2010), and 8 million women experienced complications requiring medical attention (Singh et al., 2009).

Accurate reports of abortion prevalence, the conditions under which it occurs, and women’s access to abortion are essential to address unsafe abortion globally. It is difficult to obtain reliable reports, however, because abortion is often controversial and stigmatized, even where it is legal (Jones & Kost, 2007; Sedgh, Henshaw, Singh, Ahman, & Shah, 2007). The recent increase in medication abortion further complicates the collection of accurate data, because it is often administered outside of formal health care settings. To improve the understanding and measurement of abortion, specific considerations are needed throughout all stages of the planning, design, and implementation of abortion research: Establishment of strong local partnerships, knowledge of local culture, integration of innovative methodologies, and approaches that may facilitate better reporting.

This paper draws on the authors’ collaborative research experiences conducting abortion-related studies with clinic- and community-based samples in five diverse research settings (Poland, Zanzibar, Mexico City, the Philippines, and Bangladesh). The paper discusses the design and implementation of research on abortion in international settings, both to ensure data quality and to appropriately frame inferences from this research. Although the challenges of research on abortion are widely recognized, little has been published on how best to conduct such research (Barzelatto & World Health Organization, 1996; Coeytaux, Leonard, & Royston, 1989; Rasch, Muhammad, Urassa, & Bergstrom, 2000). Our purpose here is to share insights and lessons learned with new and established researchers to inform the development and implementation of abortion-related research. We believe that the particular challenges of this research and the difficulties of collaborating in international settings create unique obstacles, and we propose strategies to overcome these obstacles.

Methods

Research Settings

This paper draws on the authors’ collaborative research experiences from five studies conducted in locations with disparate reproductive health policies and laws governing abortion. Table 1 provides the projects’ geographic locations, methodologies, and study populations. All five studies used in-depth interviews; additional methods included surveys, focus groups, and analysis of secondary survey data.

Table 1.

Research Settings and Studies

| Research Setting |

Study Objectives | Methods and Sample Size | Study Population | Family Planning and Abortion Policies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | To determine incidence of pregnancy outcomes and explore perceptions of fertility regulation | Secondary analysis of quantitative data (n = 1,066); in-depth interviews (n = 83) | Reproductive-aged couples in rural communities | Government promotion of family planning since 1971; menstrual regulation* legal since 1979 |

| Mexico City | To assess patient perceptions of the quality of care of newly legalized, public sector abortion services. | Surveys (n = 402); in-depth interviews (n = 30) | Adult women (aged ≥18) who had abortions at 3 public sector sites | National family planning program started in 1977; first-trimester abortion legalized in Mexico City in 2007; abortion remains highly restricted in other Mexican states |

| Philippines | To explore perceptions of unintended pregnancy, abortion, and abortion decision making | Focus group discussions (n = 9); in-depth interviews (n = 66) | Reproductive-aged adults (aged ≥ 21) living in a metropolitan area | Catholic Church and former president (Arroyo) oppose modern contraception; limited government support for and subsidization of contraceptives; abortion is illegal, with limited exceptions† |

| Poland | To understand contraceptive use and the knowledge and perceptions of clandestine abortion | In-depth interviews (n = 55); surveys (n = 458) | Adult women (age 18–40) living in a metropolitan area | Catholic Church opposes modern contraception; state has eliminated contraceptive subsidies; abortion is illegal with limited exceptions |

| Zanzibar | To understand contraceptive use and consequences of unwanted pregnancy | In-depth interviews (n = 50); surveys (n = 200); focus group discussions (n = 15) | Women (age ≥16) who had induced or spontaneous abortions; men and women ≥18 | Government promotion of family planning since 1985; abortion is illegal with limited exceptions |

Menstrual regulation uses manual vacuum aspiration to evacuate the uterus during the first 12 weeks after a delayed menses, often times without the confirmation of pregnancy status (Amin, 2003).

Abortion may be obtained legally in the Philippines “if it is necessary to save a woman’s life”; however, many doctors are unwilling to perform the procedure, given the potential for severe penalties (Singh et al., 2006).

Establishment of Local Collaborations

The politics and legal status of abortion inevitably influence the way research endeavors are undertaken. Collecting data on abortion may not be routine or supported by academic or research institutions, even where it is legal. The historical failure to collect abortion data may not indicate that this information is unwanted. Rather, it may be due to lack of funding or political will to focus on a sensitive, politicized issue.

Research on abortion may be more feasible in some settings when framed within a broader continuum of women’s (and family’s) health and well-being. International research cannot often be framed in terms of advocating for safe abortions because of local legal restrictions, although there are important exceptions (e.g., Mexico City). Finding a receptive local research collaborator may be particularly difficult in legally restricted settings. Advocacy groups may not be appropriate collaborators if they are perceived as too biased to conduct objective research. Large nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and government agencies may be potential collaborators on research related to family planning or postabortion care, but may hesitate to conduct research that directly addresses women’s experience with abortion if their funding restricts this kind of work. International NGOs, faculty at local universities, health care workers, and health care organizations are other potential partners.

Potential collaborators may be more open to cooperation after one-on-one meetings in which the researcher communicates her/his qualifications as well as motivations for and purpose of the study. These discussions can assuage fears of using the data to advocate for changes with which the collaborators may not be comfortable (e.g., changes in the legal status of abortion). Although most in-country collaborators recognize that abortion is an important public health and social issue, they may still face significant challenges in conducting research on abortion, particularly in more restrictive settings. There may be interest and openness to exploring this topic in some settings. In Zanzibar, for example, the collection of new data on abortion was specifically requested by the local Ministry of Health; research was conducted in collaboration with the Ministry’s Programme for Reproductive and Child Health and local obstetrician-gynecologists to improve access to family planning and to understand unsafe abortion. The research in Mexico was a collaboration between the University of California, San Francisco, the Mexico City Ministry of Health, the Research Center in Population and Health at the National Institute of Public Health, and the Population Council, Mexico. The latter two institutions have long-standing research relationships with the Mexico City Ministry of Health that were critical to the success of the study. In Bangladesh, the International Centre for Health and Population Research, a local NGO, provided access to previously collected quantitative data and facilitated the collection of primary qualitative data on pregnancy termination.

Involving local collaborators should be integral to designing the methods, obtaining informal and formal permissions, bolstering credibility or legitimacy, collecting data, and analyzing and disseminating the findings—regardless of the impetus for the research. These partnerships are also crucial in minimizing suspicion and distrust, especially if the researcher is from another country and the research is on a sensitive topic (Freier et al., 2005; Rashid, 2007).

Recruitment, Training, and Supervision of Field Team

The training and supervision of data collection staff is integral to the safety of research participants and staff, the validity of the data, and the overall success of the research effort, especially when examining such sensitive and potentially stigmatizing topics as abortion.

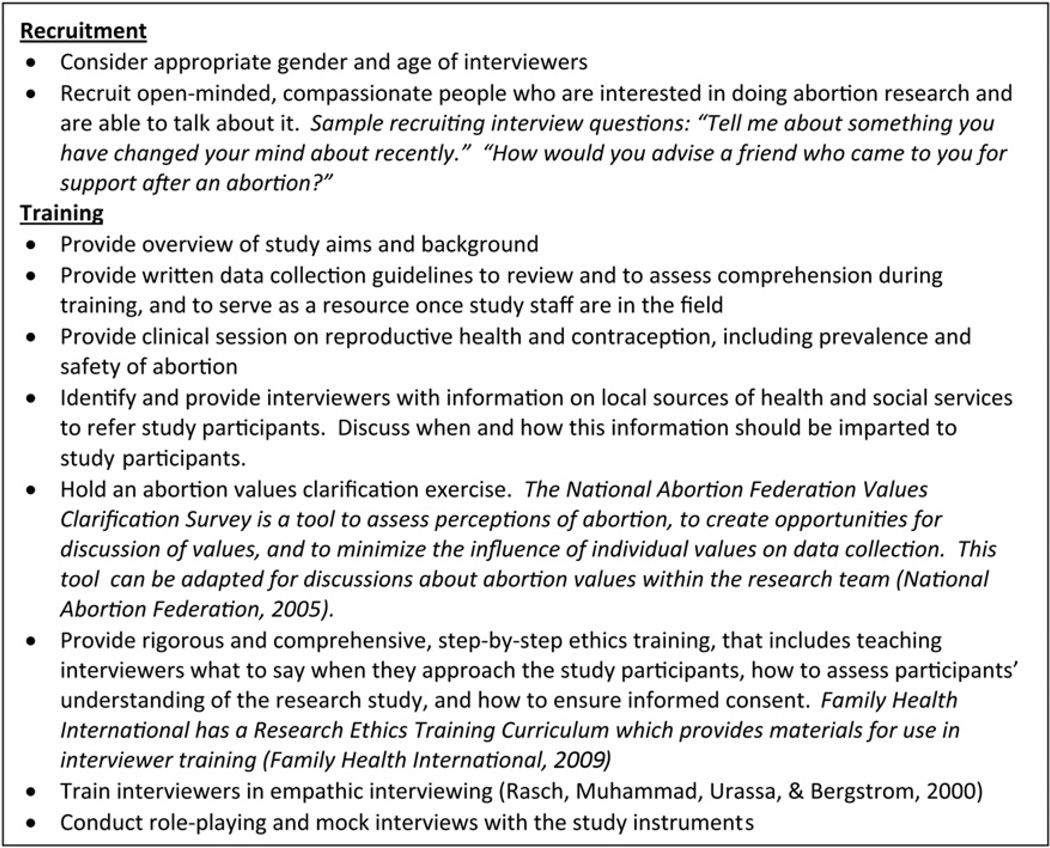

Figure 1 highlights factors to consider when hiring and training research staff. Although some training components are most applicable to data collection, involving the entire staff in selected aspects of the training is important. It is imperative that data collectors receive comprehensive training with practical, hands-on practice with the study instruments as well as feedback on their performance before and during implementation of the study.

Figure 1.

Checklist and suggestions for research staff recruitment and training recruitment.

Desired characteristics of the interviewers should be carefully considered as a first step in recruitment. Differences in socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, age, language, and gender may affect the participants’ responses, especially given the intimate nature of abortion (Molyneux et al., 2009). It may be difficult to find interviewers with all the desired characteristics. Some cultural differences may be minimized through dress, how interviewers introduce themselves to study participants, and how they integrate local terms and colloquialisms into their interactions with study participants.

Training should provide overviews on reproductive health and contraception as well as on study objectives to frame the research for the interviewers, instill motivation for collecting information on these difficult yet important topics, and provide correct reproductive health information, because this is an area in which misconceptions and misinformation are rife, even among educated professionals. Written guidelines for data collection (e.g., a standard operating procedures manual) are critical in ensuring that study procedures are explicitly communicated to the staff and can serve as a resource in the field.

Role playing, mock interviews, and training in empathic interviewing are particularly important, regardless of the interviewer’s experience or skill (Rasch et al., 2000). Empathic interviewing involves approaching participants gently and respectfully, avoiding judgmental language (including nonverbal language), supporting a participant through strong emotions, and listening actively. Empathic interviewing promotes a humane and respectful interaction with research participants, while also promoting a safe and confidential space in which they may be more likely to share personal thoughts and experiences.

It is essential that interviewers feel adequately supported during data collection, with respect to both the research process and their own well-being. Ongoing supervision is critical in providing feedback on the feasibility and implementation of the study design, procedures, and study instruments. Continual monitoring also ensures that any emergent questions, unexpected difficulties, or adverse events are immediately addressed. These components are integral to ensuring that research and ethical guidelines are followed, as well as to maximizing the quality of the data.

Interviewers are often exposed to difficult stories (e.g., rape, violence, depression) and need to be equipped to deal with distressed participants (Jewkes, Watts, Abrahams, Penn-Kekana, & Garcia-Moreno, 2000). The research team should prepare a list of resources in the community to which participants may turn for additional support; such a list may also help the staff to feel they are able to actively do something to help participants. Collecting data on abortion may also cause interviewers to revisit their own experiences with abortion (positive or negative). Interviewers may be reluctant or unable to talk with friends or family members about their work if it is negatively perceived. Thus, it is important to give interviewers a chance to talk about their reactions to data collection and their field experiences to protect their well-being and to prevent burnout. Although periodic meetings were included in all of the research studies reviewed here, the Mexico City study had special considerations owing to the controversy over the recent legalization of abortion. There, because interviewers faced anti-choice protestors, it was critical to prepare and train the interviewers in handling these situations and to provide a venue in which to discuss their experiences and unanticipated events.

Ethical Considerations

Ensuring and maintaining confidentiality and privacy are crucial in the study of abortion, especially given potential legal or social consequences. Privacy can be difficult to achieve and may require some creativity and persistence to identify a secure space in which to conduct data collection and minimize the number of interruptions. It is also important, especially in clinical settings, to establish procedures for protecting privacy, given that perceptions of privacy and confidentiality can differ cross-culturally. Additional questions to consider are whether children (of any or specific ages) can be present during data collection and whether study participants might feel more comfortable in another setting altogether. If data are collected in a clinic, for example, participants may be concerned that their responses will affect the care they receive. The Zanzibar study collected data in a setting adjacent to the main market so that any participant could come to the office without having to explain why she was in that location.

Informed consent was ascertained through oral consent in all of the studies. The reasons for oral consent varied based on the literacy of the study population, concerns about having paper documentation of participation in an illegal or stigmatizing behavior (via signed consent form), and local history or norms in which signed consent forms may cause distrust. It is essential that the study is conducted in a locally appropriate way to protect research participants. In some situations, researchers may need to inform their institutional review boards of local norms and laws and may need to include collaborators’ past studies to justify the use of oral consent. Assurance of confidentiality includes not only the collection, but also the maintenance of the data. Institutional review board protocols stipulate that all data associated with the project are stored securely and destroyed within a finite period after the project’s completion. The Mexico City study avoided collecting personal identifiers altogether through a reminder card system. Because a subsample of women from the clinic was also asked to participate in in-depth interviews, a system was designed to avoid collecting personal identifiers while still allowing women the option of returning on different days: Each woman was given a reminder card with the date of her interview, the place, and the telephone number of the interviewer in case she wanted to cancel her appointment. The interviews took place at the same care site and were conducted with the same interviewer. Seven of the 30 interviews were done with women who came back on different days (23%). Most women, however, seemed to prefer the option of doing the interview immediately after the survey.

The informed consent process involves a discussion of the risks and benefits of participation in the research. Although existing research indicates substantial underreporting of abortion owing to fear of legal consequences or stigmatization, these studies found that women often welcomed the opportunity to discuss their experiences with an empathic interviewer and to ask important questions, especially for those women who had few (if any) people with whom they could share their experience. In fact, some women in the Mexico City study asked if the interview was provided as psychological support for them.

Data Collection Methods

The choice of data collection methods for abortion-related research should be directly informed by the research questions, study design, and population(s) of interest. These choices may also be influenced by the local collaborator, the populations to which the researcher and collaborator have access, and the time and cost limitations of the study. For example, although one may be interested in the population-level impacts of unsafe abortion, a community-based study may not be feasible or ethical. A clinic-based study may be a more resource-effective way in which to identify women with unsafe abortion complications, although the selectivity of this sample (women treated at a health care facility) may limit the external validity or generalizability of the findings. These trade-offs should be weighed carefully by the researcher(s) and collaborator.

Qualitative research methods can be an important first step in determining how abortion is defined locally, the terms used to describe abortion, and the most appropriate ways to seek information on abortion. Using innovative and multiple data collection methods can provide a more holistic understanding than a single approach or than more traditional approaches (Sieber, 1973). Each of the studies used multiple data collection methods (and sometimes data sources) and several used innovative methodologies, including vignettes. Vignettes were used during focus group discussions in Zanzibar and the Philippines to explore situational acceptance of abortion and to elicit community perceptions of women who have abortions. Like studies conducted in other settings (Whittaker, 2002), these vignettes were jointly developed with collaborators to reflect locally relevant situations in which decisions about abortion are made. After reading the vignettes, participants were asked to discuss the circumstances and reasons for which abortion may or may not be warranted. Evidence from these and other studies point to the value of multiple data collection methods when researching sensitive topics (Helitzer-Allen, Makhambera, & Wangel, 1994). Although focus group discussions are a powerful method for gaining insight into social norms surrounding abortion, they are inappropriate if the interest is in personal experiences. Using both approaches allows a researcher to gain insights into both social norms and personal experiences.

Innovative methods may help to facilitate participation and result in the best data collection, given the sensitive, and in many settings, legally restricted nature of abortion. The “three-closestfriends” methodology, in which proxy questions are used to explore threatening or illegal practices, was used in Poland (Sudman, Blair, Bradburn, & Stocking, 1977). In Poland, where abortion is criminalized and women pursue these services clandestinely, this methodology proved valuable in gaining insight into women’s knowledge of how to pursue such care. Asking women to report directly on their personal experiences seeking illegal abortions may have reduced willingness to participate. Attempts to learn about induced abortion by recruiting women at a hospital for postabortion care in Zanzibar proved difficult because some women were unwilling to talk about their experiences. The study complemented this approach with participant-driven sampling, whereby participants were asked to identify other women who had had abortions and who might be willing to talk with researchers about their experiences. This latter approach was much more successful. Most participants had no trouble discussing their experience with abortion when they knew in advance they had been asked to join the study specifically for this reason. Although participant-driven sampling is an effective sampling and recruiting strategy, especially for hard-to-reach or marginalized populations, the utility of this approach should be evaluated in light of study objectives and potential bias resulting from the fact that participants with a shared social network may also be more homogeneous in other characteristics.

Implications of Study Results and Dissemination of Findings

The implications of study findings differ depending on the original purpose and investment in the research by local organizations and governments. Results in Mexico City and Zanzibar are being shared with the Ministry of Health and clinical sites so that improvements can be made. The study findings can also be made available to local or international advocates in their efforts to support safe and ethical provision of abortion and post-abortion care.

Research can draw attention to attitudes and practices regarding abortion and to the impact of program or policy efforts on unsafe abortion. Such attention may provide feedback to organizations working in this area and bolster fundraising and advocacy efforts. Researchers should take care because dissemination of research findings may draw negative or unwanted attention to collaborators, study sites, or participants. It may be necessary to mask the identity of the countries, research sites, or collaborators. Data collection may also reveal that safe abortion options do exist, even where abortion is illegal or restricted. The masking of clinic or community information is imperative in such cases to avoid any possible legal repercussions for providers and women.

It is important to keep participant data anonymous regardless of the research setting. This is especially important when using in-depth research methods, because narratives constitute the data collected and verbatim quotes are the key evidence with which researchers present their findings. The use of emblematic quotes that omit identifying names, words, or phrases can convey important findings while maintaining participants’ confidentiality.

Conclusion

Conducting research on abortion is difficult in any setting and may be particularly challenging in settings where abortion is restricted or highly stigmatized. These difficulties can be surmounted, however, through careful planning, implementation, and collaboration. This presentation of lessons learned from five global case studies will, ideally, help to shape and inform subsequent research on abortion and to facilitate ethical and methodologically sound investigations into this important social and public health issue.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding and support of the Charlotte Ellertson Social Science Postdoctoral Fellowship in Abortion and Reproductive Health. Jessica Gipson acknowledges funding from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and The Johns Hopkins Endowed Student Support for the Bangladesh fieldwork. Alison Norris acknowledges funding from the Society for Family Planning.

Biographies

Jessica D. Gipson, MPH, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Public Health. Her research focuses on sexual and reproductive health decision-making and outcomes.

Davida Becker, PhD, is a Research Scholar at the Center for the Study of Women at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research focuses on the accessibility and quality of reproductive health services and disparities in reproductive health outcomes.

Joanna Z. Mishtal, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Central Florida. Her current research, situated in Ireland and at the European Union, examines the role of conscience-based objection in the provision of reproductive health services.

Alison H. Norris, MD, PhD, was an Ellertson Fellow from 2008–2010. At the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, MD, she pursues multi-method research on sexual and reproductive health epidemiology in under served women and men.

References

- Amin S. Menstrual regulation in Bangladesh. In: Basu AM, editor. The sociocultural and political aspects of abortion. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Barzelatto J the World Health Organization, Maternal and Newborn Health/ Safe Motherhood Unit. Studying unsafe abortion: A practical guide. Geneva: Maternal and Newborn Health/Safe Motherhood Unit, Division of Reproductive Health (Technical Support), World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Coeytaux F, Leonard A, Royston E, editors. Methodological issues in abortion research. New York: Population Council; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Freier MC, McBride D, Hopkins G, Babikian T, Richardson L, Helm H. The process of research in international settings: From risk assessment to program development and intervention. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(Suppl. 4):vi9, 15. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helitzer-Allen D, Makhambera M, Wangel A-M. Obtaining sensitive information: The need for more than focus groups. Reproductive Health Matters. 1994;2:75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Watts C, Abrahams N, Penn-Kekana L, Garcia-Moreno C. Ethical and methodological issues in conducting research on gender-based violence in Southern Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 2000;8:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(00)90010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RK, Kost K. Underreporting of induced and spontaneous abortion in the United States: An analysis of the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Studies in Family Planning. 2007;38:187–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneux C, Goudge J, Russell S, Chuma J, Gumede T, Gilson L. Conducting health-related social science research in low income settings: Ethical dilemmas faced in Kenya and South Africa. Journal of International Development. 2009;21:309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Rasch V, Muhammad H, Urassa E, Bergstrom S. Self-reports of induced abortion: An empathetic setting can improve the quality of data. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:1141–1144. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid SF. Accessing married adolescent women: The realities of ethnographic research in an urban slum environment in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Field Methods. 2007;19:369–383. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgh G, Henshaw S, Singh S, Ahman E, Shah IH. Induced abortion: Estimated rates and trends worldwide. The Lancet. 2007;370:1338–1345. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61575-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah I, Ahman E. Unsafe abortion in 2008: Global and regional levels and trends. Reproductive Health Matters. 2010;18:90–101. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber SD. The integration of fieldwork and survey methods. American Journal of Sociology. 1973;78:1335–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Wulf D, Hussain R, Bankole A, Sedgh G. Abortion worldwide: A decade of uneven Progress. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Juarez F, Cabigon J, Ball H, Hussain R, Nadeau J. Unintended pregnancy and induced abortion in the Philippines: Causes and consequences. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sudman S, Blair E, Bradburn N, Stocking C. Estimates of threatening behavior based on reports of friends. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1977;41:261–264. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker A. ‘The truth of our day by day lives’: Abortion decision making in rural Thailand. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 2002;4:1–20. [Google Scholar]