Abstract

Dipyridamole anti-platelet therapy has previously been suggested to ameliorate chronic tissue ischemia in healthy animals. However, it is not known if dipyridamole therapy represents a viable approach to alleviating chronic peripheral tissue ischemia associated with type 2 diabetes. Here we examine the hypothesis that dipyridamole treatment restores reperfusion of chronic hind limb ischemia in the murine B6.BKS-Leprdb/db diabetic model. Dipyridamole therapy quickly rectified ischemic hind limb blood flow to near pre-ligation levels within three days after starting therapy. Restoration of ischemic tissue blood flow was associated with increased vascular density and endothelial cell proliferation observed only in ischemic limbs. Dipyridamole significantly increased total nitric oxide metabolite levels (NOx) in tissue that were not associated with changes in eNOS expression or phosphorylation. Interestingly, dipyridamole therapy significantly decreased ischemic tissue superoxide and protein carbonyl levels identifying a dominant antioxidant mechanistic response. Dipyridamole therapy also moderately reduced diabetic hyperglycemia and attenuated development of dyslipidemia over time. Together, these data reveal that dipyridamole therapy is an effective modality for the treatment of chronic tissue ischemia during diabetes and highlights the importance of dipyridamole antioxidant activity in restoring tissue NO bioavailability during diabetes.

Keywords: superoxide, type 2 diabetes, nitric oxide, endothelial cell, peripheral artery disease

Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a chronic arterial occlusive disease of the extremities caused by atherosclerosis, characterized by high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [1]. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) are frequently afflicted with PAD and DM is associated with a 2–4 fold increase in the incidence of PAD compared to non-diabetics [2]. It is well known that type 2 DM causes amplification of the atherosclerotic process, endothelial cell dysfunction, glycosylation of extracellular matrix proteins and vascular denervation. These complications lead to impairment of vascular remodeling and collateral formation that would normally follow ischemic insult as a reparative response [3], and delineates diabetes as the most common cause of non-traumatic amputation [2]. Revascularization of ischemic tissue via therapeutic angiogenesis could play an important role in the management of diabetic patients with PAD when traditional therapies (e.g. cilostazol, exercise regimen, dietary modifications, etc) prove ineffective. However, few agents or modalities have been shown to be clinically effective for stimulating therapeutic angiogenesis during PAD or critical limb ischemia (CLI). Thus, there is a continuing need for identifying effective therapeutic agents which augment ischemic tissue angiogenic activity during diabetes.

Therapeutic angiogenesis remains an attractive treatment modality for chronic ischemic disorders including PAD [4]. The establishment of patent blood vessel networks is a complex process that requires several factors and signaling pathways to stimulate vessel sprouting and remodeling of established vascular structures [5]. Although experimental treatments with numerous mediators including growth factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), transcription factors, and signaling molecules (e.g. endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)) have been effective in healthy animals; successful clinical translation has been substantially limited in patients, possibly due to the lack of rigorous evaluation in representative animal models of disease [6, 7].

Dipyridamole is an antithrombotic and vasodilating agent effective in secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease [8]. Dipyridamole therapy could improve tissue perfusion through several mechanisms including antiplatelet effects, action as a vasodilatory agent potentiating NO bioavailability, or possibly through its antioxidant properties via scavenging peroxyl radicals [9, 10]. Reports have suggested that dipyridamole could be effective in increasing capillary density in both a rat and rabbit heart following myocardial ischemia and augment collateral vessel growth via adenosine action in local ischemic tissues [11, 12]. Recent work in our lab has shown that dipyridamole augments ischemia-induced arteriogenesis through an endocrine nitric oxide-dependent pathway [10]. Importantly, diabetes impairs both nitric oxide synthase activity and NO bioavailability leading to vascular dysfunction with concomitant enhanced oxidative stress [13–15]. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that dipyridamole therapy is beneficial for diabetic chronic tissue ischemia and report here that dipyridamole robustly augments ischemic tissue reperfusion and angiogenic activity in diabetic mice by decreasing oxidative stress and replenishing NO bioavailability. These data suggest that dipyridamole may be a useful agent in alleviating diabetic vascular dysfunction and tissue ischemia.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Dipyridamole was supplied by Boehringer-Ingelheim, Germany. Total and phospho-Ser1176 eNOS antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Ki67 antibody was purchased from Abcam Inc. and CD31 antibody was obtained from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ). Vectashield plus DAPI was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Secondary antibodies conjugated to fluorophores were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Inc (West Grove, PA). VEGF ELISA kit was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). All other chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO).

Animals

B6.BKS-Leprdb/db diabetic mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). 20 week old B6.BKS-Leprdb/db (Db/Db) diabetic mice were used for all experiments. Mice were housed at the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International accredited Louisiana Health Science Center-Shreveport animal resource facility, and maintained in accordance with the National Research Council’s Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animal procedures and experiments were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

Dipyridamole therapy and surgical model

Dipyridamole was administered at a previously determined optimal dose of 200 mg/kg in Db/Db mice to obtain a steady state plasma therapeutic level between 0.8–1.2 µg/ml as we have reported [10, 16]. Unilateral chronic hind limb ischemia was induced by ligation, transection, and removal of the left common femoral artery proximal to the origin of the profunda artery and its collateral branches as we have previously reported [10, 16]. Dipyridamole or vehicle control (acid water with 10% glycofurol) therapy was administered by a gavage of either formulation (500 µl volume) twice a day for the duration of the study.

Blood Chemistry Measurements

Blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus three times during the course of the study: prior to beginning dipyridamole therapy, three days after beginning therapy immediately prior to ligation, and 7 days post ligation. The collected blood was then sent to the LSUHSC clinical lab where blood glucose, cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL, and LDL levels were measured. Body weight was also recorded at these time points.

Laser Doppler Measurements

Laser Doppler blood flows were measured using a Vasamedics Laserflo BPM2 device as we have previously reported in the gastrocnemius pre-ligation, post-ligation and on days 3, 5, and 7 post-ligation [10, 16]. Blood vessels visible through the skin were avoided to ensure readings indicative of muscle blood flow. Measurements were recorded as milliliter of blood flow per 100 grams of tissue per minute. Percent blood flows were calculated as: where a = ischemic limb average flow and b = non-ischemic limb average flow.

Vascular Density Measurement

Vascular density measurements were performed as we have previously reported [10, 16]. Briefly the gastrocnemius muscles from ischemic and non-ischemic hind limbs were removed, dissected, and embedded in OCT freezing medium. Frozen tissue blocks were cut into 5 µm sections and slides prepared. A primary antibody against CD31 was added at a 1:200 dilution and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Slides were then washed and a Cy3 conjugated secondary antibody was added at a 1:250 dilution and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. Slides were once again washed and mounted with coverslips using Vectashield DAPI. A minimum of four slides per hind limb with three sections per slide were prepared for vascular density analysis. A minimum of two fields were acquired per section of muscle. Images were captured using a Hamamatsu digital camera in conjunction with a Nikon TE-2000 epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Corporation, Japan) at 200× magnification for CD31 and DAPI staining. Simple PCI software version 6.0 (Compix Inc., Sewickly, PA, USA) was used to determine the area CD31 and DAPI positive staining. Tissue vascular density was determined as the ratio between CD31 positive areas and DAPI positive regions.

Cellular proliferation Measurement

Immunofluorescent staining of the nuclear cell proliferation protein Ki67 was used to identify proliferating cells (anti-Ki67 1:350 dilution) from other cells (DAPI staining) as we have previously reported [10, 16]. Frozen tissue sections were simultaneously stained for Ki67, CD31, and DAPI to identify colocalized markers indicating endothelial cell proliferation. Images were acquired as described above. Cellular proliferation was determined as the ratio between regions positive for Ki67 and DAPI positive areas.

Tissue NOx measurement and eNOS western blotting

Tissue total NOx levels were measured using a chemiluminescent NO analyzer (GE Healthcare) as we have previously published [10, 16]. Briefly, vehicle control or dipyridamole treated mice were euthanized at day 7 and gastrocnemius non-ischemic and ischemic muscle tissue harvested and cut in a mid-sagittal manner resulting in two proportional specimens. One half was added to a 500 µl solution containing 800 mM potassium ferricyanide, 17.6 mM N-ethylmaleimide, and 6% nonidet P40. Tissue was then homogenized and allowed to incubate at room temperature for 5 minutes. Tissue vials were then snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 until chemiluminescent analysis with vanadium chloride. The remaining tissue specimen was homogenized in RIPA buffer with proteinase and phosphatase inhibitors, and spun down to obtain tissue protein supernatants. Total eNOS, phospho-Ser1176 eNOS, and GAPDH westerns were performed as we have previously reported [10, 16].

Tissue superoxide, protein carbonyl, and VEGF measurements

Tissue superoxide production was measured using the hydroethidine (HE) HPLC method as previously published by Zielonka et al [17]. On day 7, Db/Db mice were injected i.p. with 300 µl of HE (1 µg/µl). HE injected animals were sacrificed one hour later and gastrocnemius muscle tissue from non-ischemic and ischemic hind limbs were isolated and cut in a mid-sagittal manner resulting in two equal portions of gastrocnemius tissue. Tissue proteins from one half were precipitated using acidified methanol and 2-OH-E+ enriched using a micro-column preparation of Dowex 50WX-8 cation exchange resin and eluted with 10 N HCl. 2-OH-E+ product was then measured using fluorescence detection (ex: 490; em: 567) with a Shimadzu UFLC HPLC system. 2-OH-E+ superoxide production was normalized to total protein and reported as pmol/mg of protein. Tissue protein carbonyls were measured from the remaining muscle half using a Protein Carbonyl ELISA from Cell Biolabs Inc (San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein carbonyl formation was normalized to total protein and reported as nmols/mg of protein. Tissue levels of VEGF, at days 3 and 7 post ligation, were measured using a VEGF ELISA from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. VEGF concentrations were normalized to total protein and reported as pg/mg of tissue protein.

Statistical Analysis

Student’s t-test (unpaired) was used to analyze differences between dipyridamole treatment and vehicle control groups. A p<0.05 value was used to indicate significance. Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0 software.

Results

Dipyridamole increases blood flow in a diabetic model of chronic hind limb ischemia

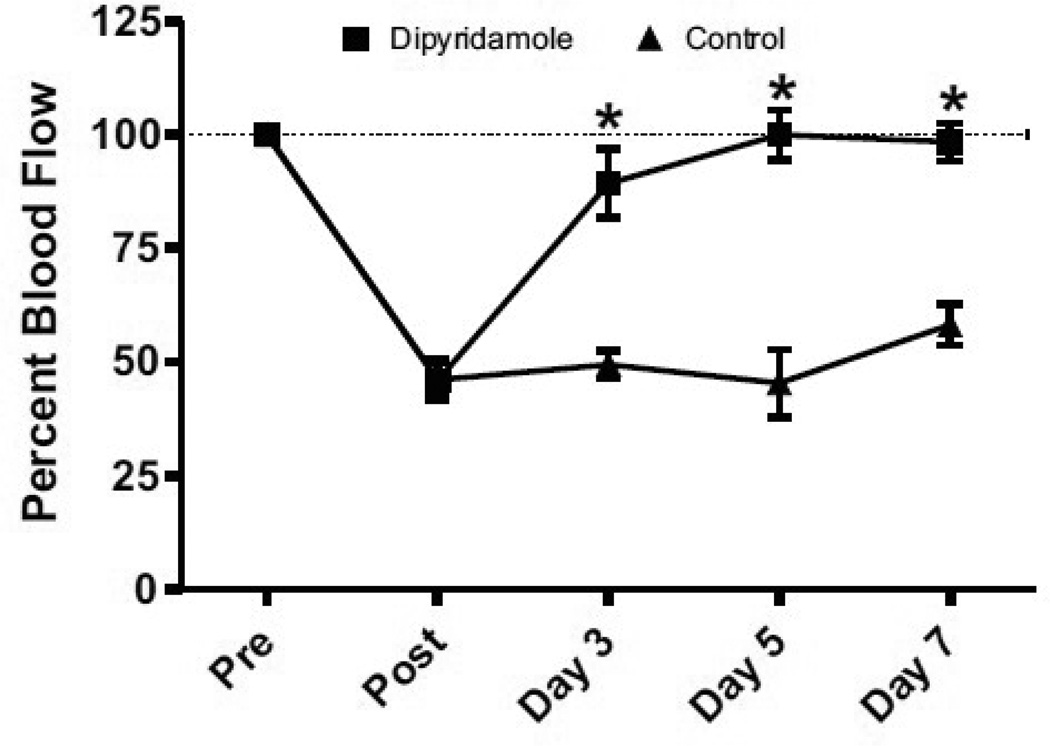

Diabetes is one of the largest risk factors for development of PAD, which is further influenced age as well as sex, and is largely associated with type 2 diabetes [18, 19]. Therefore, we tested the efficacy of dipyridamole therapy in a type-2 diabetic murine model of PAD. Figure 1 shows that dipyridamole treatment resulted in a rapid restoration of ischemic hind limb blood flow which was significantly increased by day 3 post ligation and maintained long term compared to vehicle control. These data demonstrate that dipyridamole therapy is highly effective in restoring ischemic limb reperfusion in a diabetic PAD model.

Figure 1.

Dipyridamole therapy restores diabetic ischemic hind limb blood flow as measured by laser Doppler. Dipyridamole treatment (200 mg/kg) significantly increases and maintains ischemic hind limb blood flow by day 3 post-ischemia compared to vehicle control therapy. n=8 per cohort, *p<0.05.

Dipyridamole increases vascular density in a model of chronic ischemia

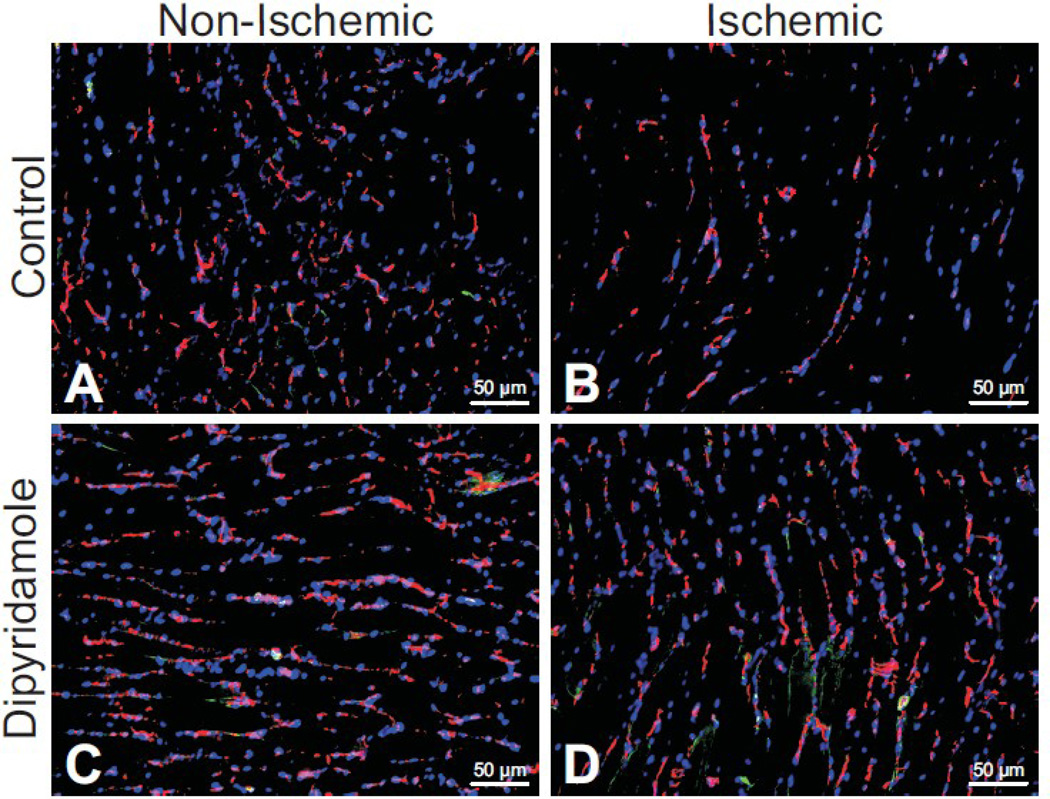

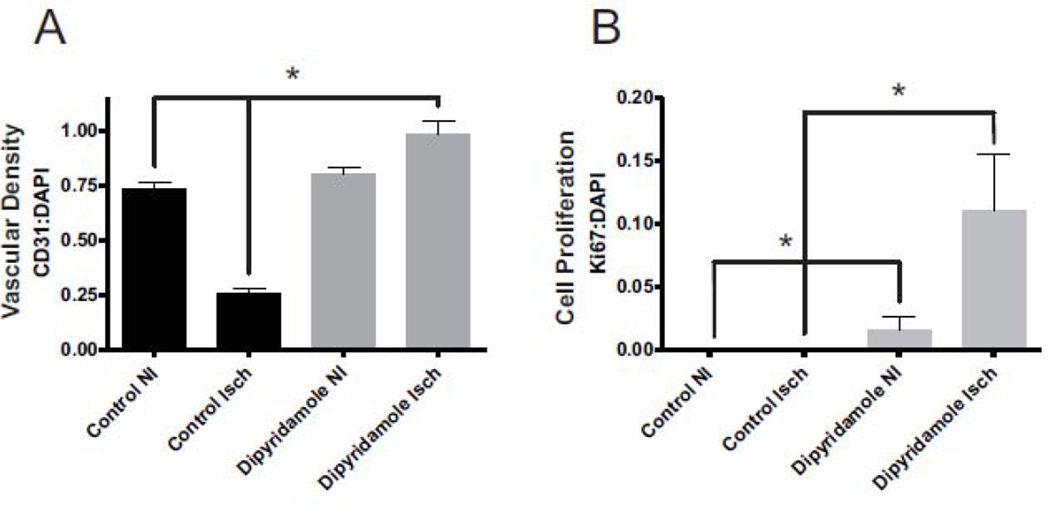

We have recently reported that dipyridamole can augment arteriogenesis and vascular remodeling in chronically ischemic tissue of healthy mice [10]. However, it is not known whether dipyridamole influences ischemia induced angiogenesis under diabetic conditions. Figure 2 illustrates vascular density (anti-CD31-red) and cell proliferation (anti-Ki67-green) staining of vehicle control treated non-ischemic and ischemic gastrocnemius muscle tissue (Figure2A and 2B) at day 7 post-ligation. Likewise, figure2C and 2D illustrate vascular density and cell proliferation staining of dipyridamole treated non-ischemic and ischemic gastrocnemius muscle, respectively. Dipyridamole treatment significantly increased both vascular density staining and cell proliferation staining (Figure 2D) compared to vehicle control treated ischemic tissue (Figure 2E). Importantly, vascular endothelial CD31 and Ki67 staining is colocalized in dipyridamole treated ischemic tissue which was not apparent in other tissue groups. Figure 3 reports quantitative immunohistochemical measurement of vascular density (CD31:DAPI ratio- Figure 3A) and cell proliferation (Ki67:DAPI- Figure 3B) indices confirming that dipyridamole therapy significantly and selectively increases ischemic limb vascular density concomitant with increased cell proliferation. Interestingly, dipyridamole therapy slightly increased Ki67 staining of non-ischemic gastrocnemius tissue; however, this was not associated with a change in vascular density compared to vehicle control treated non-ischemic tissue.

Figure 2.

Dipyridamole therapy promotes ischemic angiogenesis in the diabetic hind limb. Panels A and B illustrate CD31 (endothelial stain; red), Ki67 (proliferating cell stain; green), and DAPI (nuclear stain; blue) staining of non-ischemic and ischemic gastrocnemius tissue at day 7 from vehicle control treated mice. Panels C and D show CD31 (endothelial stain; red), Ki67 (proliferating cell stain; green), and DAPI (nuclear stain; blue) staining of non-ischemic and ischemic gastrocnemius tissue at day 7 from dipyridamole treated mice. Images are representative of 30 sections per tissue and treatment.

Figure 3.

Quantitative measurement of dipyridamole mediated vascular density and cell proliferation. Panel A reports the quantitative measurement of vascular density (CD31:DAPI ratio) from images of ischemic (Isch) and non-ischemic (NI) vehicle control and dipyridamole treated diabetic mice at day 7. Panel B shows the quantitative measurement of cell proliferation (Ki67:DAPI) ratio from images of Isch and NI vehicle control and dipyridamole treated diabetic mice at day 7. n=20 per cohort, *p<0.05.

To determine if dipyridamole increased VEGF164 levels, tissues were isolated at day 7 post ligation to perform VEGF164 ELISA’s (Table 2). No statistical difference was observed between treatment groups at day 7. However, Hazarika et al. has reported in a diet induced model of type 2 diabetes that hind limb ligation resulted in an increase in VEGF164 concentrations at 3 days post ligation but not at day 10 post ligation [20]. Based on this report we repeated the ELISA at day 3 post ligation (Table 2) and found an increase in VEGF164 concentrations between the ischemic and non-ischemic limbs, but no statistical difference was found between the treatment groups.

Table 2.

At day 3 post ligation VEGF levels are increased in the ischemic limb of both dipyridamole and control treatment groups compared to their respective non-ischemic limbs. At day 7 VEGF levels are not significantly different.

| Control VEGF Concentrations | Dipyridamole VEGF Concentrations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Ischemic Limb [pg/mg protein] |

Ischemic Limb [pg/mg protein] |

Non-Ischemic Limb [pg/mg protein] |

Ischemic Limb [pg/mg protein] |

|

| 3 Days Post Ligation | 12.26 ± 1.15 | 17.46 ± 3.85* | 12.07 ± 1.71 | 21.86 ± 4.85* |

| 7 Days Post Ligation | 7.78 ± 2.66 | 10.15 ± 0.51 | 12.05 ± 1.15 | 7.41 ± 0.75 |

n=5 per cohort.

p<0.05 versus non-ischemic limb, n=5

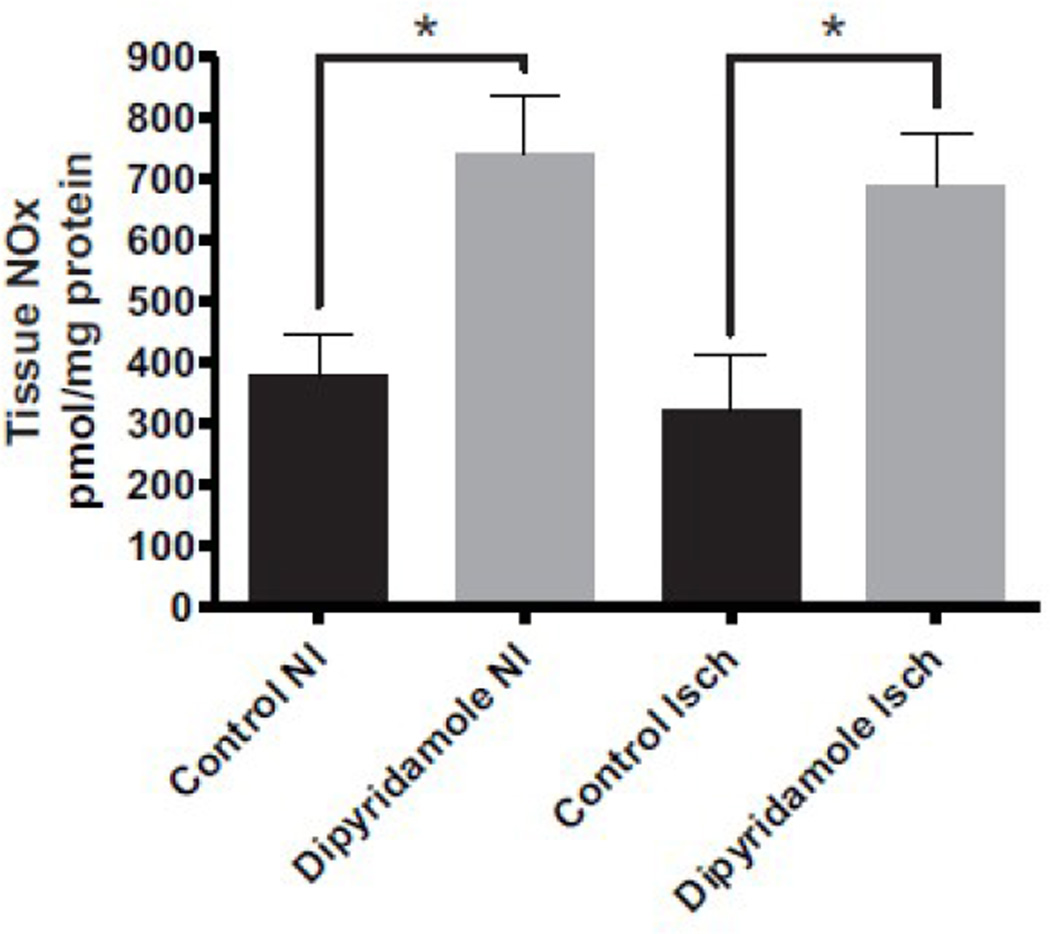

Dipyridamole treatment increases tissue NO bioavailability

Patients with diabetes experience a reduction in the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO), contributing to endothelial cell dysfunction which also influences endothelial cell angiogenic activity [18, 21]. It is proposed that increased ROS production during diabetes enhances aldose reductase activity leading to cellular depletion of antioxidant reserves which ultimately diminishes NO bioavailability due to increased oxidative stress [19]. Since diabetes is associated with a reduction in bioavailable NO, we next measured total tissue NOx levels in both vehicle control and dipyridamole treated diabetic mice at day 7. Dipyridamole therapy significantly increased tissue NOx levels in ischemic and non-ischemic limbs compared to vehicle treatment (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Dipyridamole therapy increases diabetic tissue NOx levels. Tissue NOx levels were measured from vehicle control and dipyridamole treated ischemic (Isch) and non-ischemic (NI) limbs at day 7. n=8 per cohort, *p<0.05.

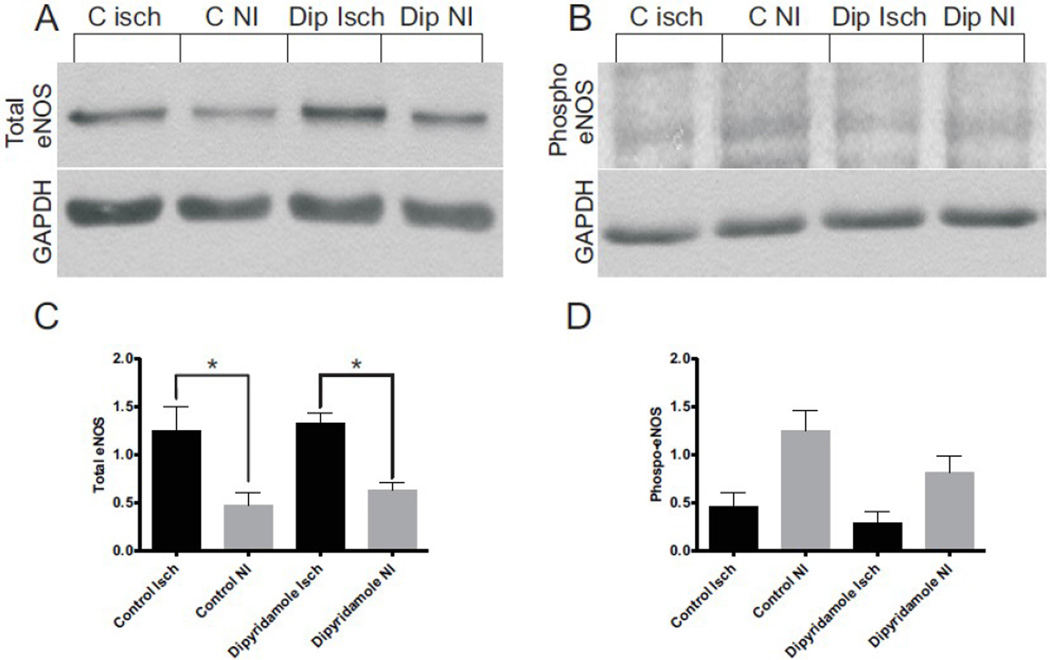

We next examined whether dipyridamole therapy altered eNOS protein expression or phosphorylation in non-ischemic or ischemic gastrocnemius tissue. Figure 5A illustrates that dipyridamole treatment did not significantly alter the amount of total eNOS expression in ischemic versus non-ischemic tissue compared to vehicle control treatment. Likewise, figure 5B shows eNOS Ser1177 phosphorylation differences in ischemic and non-ischemic tissues from dipyridamole and vehicle control treatments. In both vehicle and dipyridamole treatments, eNOS phosphorylation was greater in non-ischemic versus ischemic tissue. Moreover, dipyridamole treatment did not significantly alter eNOS phosphorylation in ischemic tissue. However, there was a slight, insignificant decrease in eNOS phosphorylation in dipyridamole treated non-ischemic tissue. Panels 5C and 5D report western blot densitometry measurements for total and Ser1177 phospho-eNOS, respectively. These data demonstrate that dipyridamole therapy does not significantly alter eNOS expression or phosphorylation in diabetic muscle tissue.

Figure 5.

Dipyridamole therapy does not alter diabetic total eNOS or eNOS phospho-Ser 1177 levels. Panel A illustrates a representative western blot of total eNOS between vehicle control and dipyridamole tissues compared to GAPDH. Panel B shows a representative phospho-eNOS Ser1177 western blot between vehicle control and dipyridamole treatments compared to GAPDH. Panel C reports western blot densitometry for total eNOS expression normalized to GAPDH. Panel D reports the western blot densitometry for phospho-eNOS expression normalized to GAPDH. n=6 per cohort, *p<0.05.

Dipyridamole treatment decreases oxidative stress

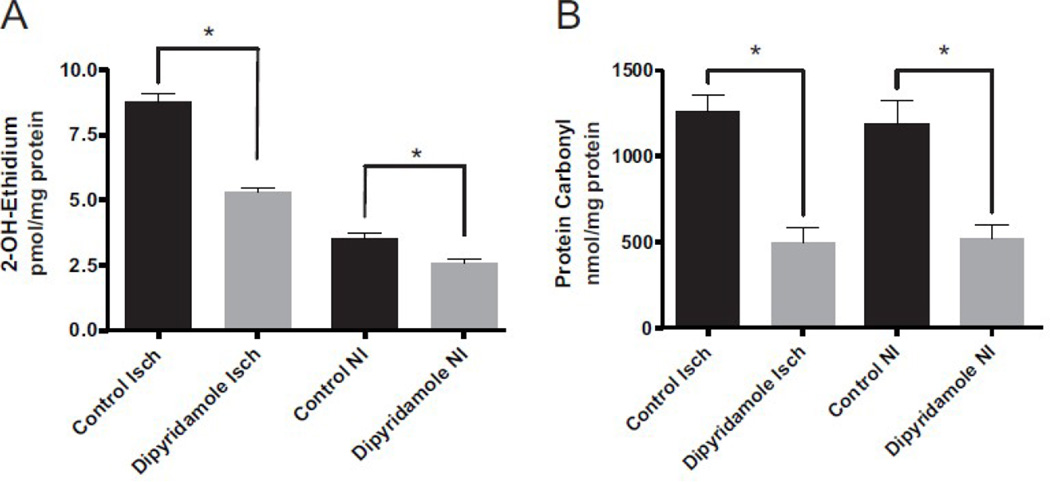

ROS generation is a prominent factor in the pathology of diabetes, which can lead to diminished eNOS function and NO bioavailability thus further enhancing ROS production and tissue dysfunction [21, 22]. Dipyridamole has previously been reported to contain antioxidant properties which can spare endogenous antioxidant pools of vascular cells in vitro [23, 24]. Therefore, we examined whether dipyridamole therapy diminished oxidative stress in vivo which would facilitate restoration of bioavailable NO and vascular health in ischemic tissue. Figure 6A illustrates HPLC measurement of the superoxide specific 2-OH E+ product in vehicle control and dipyridamole treated tissues. Superoxide generation was significantly increased in ischemic tissues of vehicle control treated diabetic mice compared to non-ischemic tissue. Importantly, dipyridamole therapy significantly decreased superoxide production in ischemic diabetic tissue compared to vehicle controls and also blunted superoxide production in non-ischemic tissue. Figure 6B further illustrates that dipyridamole therapy significantly decreased diabetic tissue protein carbonyl levels in both ischemic and non-ischemic gastrocnemius tissue. These data demonstrate that dipyridamole therapy exerts a potent antioxidant effect in diabetic ischemic tissue.

Figure 6.

Dipyridamole therapy decreases diabetic tissue superoxide formation and protein oxidation. Panel A reports tissue superoxide production in ischemic (Isch) and non-ischemic (NI) limbs of dipyridamole and vehicle control treated diabetic mice. Panel B shows tissue protein carbonyl levels in Isch and NI limbs of dipyridamole or vehicle control treated diabetic mice. n=6 per cohort, *p<0.05.

Dipyridamole therapy lowers blood glucose and attenuates hypercholesterolemia

Type 2 diabetes associated cardiometabolic syndrome is characterized by both hyperglycemia as well as dyslipidemia (e.g. increased cholesterol and LDL levels and decreased HDL) which both contribute to vascular dysfunction. We next examined whether dypridamole treatment might alter metabolic parameters of diabetes including body weight, blood glucose, cholesterol, triglyceride, HDL and LDL levels prior to treatment, 3 days after beginning treatment, and again at day 7. Body weight and triglyceride levels did not significantly change in either treatment group (dipyridamole or vehicle control, data not shown). Blood glucose in the dipyridamole treatment group was significantly decreased by day 7 post-ligation; however, the end glucose reading of 299.2 ± 90.6 is still considered hyperglycemic. Interestingly, cholesterol and LDL levels in the dipyridamole treatment group did not vary over time; whereas vehicle control treated cholesterol and LDL levels progressively increased (Table 1). These data demonstrate that dipyridamole therapy moderately alters metabolic dysfunction in this Db/Db diabetic hind limb ischemia model.

Table 1.

Dipyridamole therapy lowers blood glucose levels and stabilizes dyslipidemia in Db/Db mice.

| Control | Dipyridamole | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Glucose (mg/dL) |

Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

HDL (mg/dL) |

LDL (mg/dL) |

Blood Glucose (mg/dL) |

Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

HDL (mg/dL) |

LDL (mg/dL) |

|

| Baseline | 507.4 ± 97.1 | 152.8 ± 19.2 | 77 ± 10 | 54 ± 6.9 | 427.8 ± 53.8 | 166.4 ± 4.2 | 79 ± 1.9 | 68 ± 6.5 |

| Day 3 Treatment | 477.0 ± 80.1 | 197.0 ± 22.1* | 95 ± 7.3* | 77 ± 14* | 384.8 ± 49.2 | 174.0 ± 14.9 | 87 ± 3.6 | 64 ± 13 |

| Day 7 Treatment | 438.3 ± 39.9 | 202.0 ± 20.3* | 94 ± 7.9* | 92 ± 13* | 299.2 ± 90.6* | 163.4 ± 15.9 | 74 ± 4.1 | 72 ± 14 |

n=5 per cohort, values compared to respective pre-treatment levels,

p<0.05

Discussion

Reperfusion of ischemic tissues through therapeutic angiogenesis and arteriogenesis has been long pursued due to limited efficacy and duration of current surgical revascularization and pharmacological approaches. Moreover, as the incidence of both diabetes and PAD continues to increase, there is a growing need to identify novel and more effective ways to treat diabetic ischemic vascular disease.

Dipyridamole has historically been used as an anti-platelet agent that is currently formulated with aspirin for hemostasis management after initial ischemic stroke, which confers significant protection against recurrent stroke [25], although mechanisms of action for these combined therapies are largely unknown in patients with peripheral vascular disease [26]. Dipyridamole has also been suggested to augment coronary collateral perfusion and development which could augment cardiac function after ischemia/reperfusion injury [12, 27, 28]. Moreover, we have recently reported that dipyridamole therapy stimulates arteriogenesis during chronic hind limb ischemia involving the endocrine NO/nitrite system [10]. Despite these compelling observations, no studies have been performed directly examining the effect of dipyridamole on reperfusion of diabetic chronic hind limb ischemia. Here we demonstrate that dipyridamole therapy selectively and rapidly augments restoration of ischemic hind limb blood flow in the Db/Db diabetic mouse.

Diabetic vascular disease is known to encompass defective angiogenic responses during wound healing and tissue ischemia [29]. This defective angiogenesis response has been attributed to several pathophysiological mediators such as hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, oxidative stress, and decreased NO bioavailability which all contributes to endothelial dysfunction [30]. We found that dipyridamole therapy selectively enhanced vascular density in ischemic tissue in the diabetic setting demonstrating that endothelial cell dysfunction associated with the Db/Db murine model of type 2 diabetes could be corrected. We also observed that dipyridamole preferentially increased endothelial cell proliferation in ischemic tissues along with a moderate but significant increase in cell proliferation in non-ischemic tissue. We also observed a small amount of colocalization between endothelial and proliferation markers in non-ischemic tissue sections suggesting the interesting possibility that dipyridamole might possibly alter diabetic microvascular rarefaction. Together, our findings clearly demonstrate that dipyridamole rapidly stimulates robust vascular growth in the diabetic ischemic hind limb.

Increased oxidative stress and decreased NO bioavailability are hallmark traits of endothelial cell dysfunction and cardiovascular pathology during diabetes in both humans and animals [22, 31]. Moreover, previous experimental studies suggest that repletion of NO through different approaches (e.g. eNOS overexpression, increased substrate or co-factor availability, or NO donors) could be beneficial for ischemic tissue reperfusion during diabetes [32–35]. On the other hand, few studies have directly identified the importance of oxidative stress in mediating defective angiogenesis and reperfusion of chronically ischemic diabetic tissue [36]. Our findings clearly demonstrate that increased superoxide production in Db/Db diabetic tissues is a critical determinant of tissue NO bioavailability that is independent of changes in eNOS expression or phosphorylation. This observation is consistent with a recent report by Lavi et al that shows decreased NO bioavailability concomitant with decreased superoxide dismutase activity and increased F2 isoprostane formation that is independent of inflammatory markers [37]. Diabetic mice are known to have depressed levels of NO bioavailability due to oxidation of tetrahdyrobiopterin [38], suggesting that our diabetic mice also have depressed levels of NO when compared to wild type mice. In the event that this is true it is possible that dipyridamole therapy may be beneficial itself by restoring cellular NO bioavailability in the diabetic mouse model, making further study of treatment time course effects necessary in the future. Dipyridamole could be mitigating oxidative stress through several possible mechanisms including but not limited to direct anti-oxidant effects, decreased generation of reactive oxygen species from various sources, induction of different antioxidant enzymes or pathways, or a combination of these possibilities. While future studies are clearly needed to address these possibilities, our data are the first to identify dipyridamole reduction of oxidative stress as a primary protective mechanism of ischemia induced angiogenesis during diabetes.

Nakagawa et al has suggested that VEGF could act through two pathways one NO dependent, the other NO independent [39]. In a diabetic model VEGF acted through an NO independent pathway and resulted in over activation of endothelium and resulted in a poor outcome [39]. Expanding this idea to our current manuscript, it is entirely possible that the protective effect dipyridamole exerts on NO bioavailability may also act to restore VEGF homeostasis. In table 2 at day 7 the control ischemic limb has slightly elevated levels of VEGF compared to the ischemic limb of the dipyridamole treated animal. While not statistically significant this suggests, when combined with elevated angiogenesis, that endothelial cell dysfunction may be exacerbated in the control treated animal and this could be due to NO independent VEGF action as suggested by Nakagawa.

Dipyridamole therapy not only preserved NO bioavailability and mitigated oxidative stress, but surprisingly affected cholesterol and blood glucose levels. The effect on cholesterol is consistent with a previous report from Garcia-Fuentes et al. demonstrating that coconut-oil induced hypercholesterolemia was blunted with dipyridamole therapy; however, our study is the first to demonstrate this effect in a model of diabetes [40]. Few studies have revealed that dipyridamole therapy alters blood glucose levels. However, Araujo et al demonstrated that dipyridamole enhanced myocardial glucose uptake in areas with stenotic arteries [41]. It is possible that dipyridamole therapy could alter blood glucose levels in our model by increasing muscle NO bioavailability which regulates skeletal muscle glucose uptake [42–45]. Future studies are needed to better understand the interesting effect of dipyridamole on metabolic parameters during diabetes and whether they depend on restoring tissue NO bioavailability.

In summary, our findings show that dipyridamole effectively restores ischemic tissue reperfusion, angiogenic activity, and decreases oxidant stress in a diabetic model of femoral artery ligation emulating PAD. These data are encouraging as dipyridamole has a good clinical safety profile along with well understood pharmacokinetics. Our findings suggest that dipyridamole therapy for diabetic PAD represents an attractive clinical approach to stimulate ischemic angiogenesis and restore tissue blood flow. However, it is currently not known how dipyridamole therapy would affect other diabetic vascular disorders such as diabetic retinopathy which requires further study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Wolfgang Eisert for helpful comments and insight. We would also like to thank Mr. Sawyer Bonsib for editorial assistance.

This work was supported by NIH grants HL080482, HL094021, and a Boehringer Ingelheim research award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aronow WS. Peripheral arterial disease in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2:645–654. doi: 10.2147/cia.s2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukherjee D. Peripheral and cerebrovascular atherosclerotic disease in diabetes mellitus. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;23:335–345. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaper NC, Nabuurs-Franssen MH, Huijberts MS. Peripheral vascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000;16(Suppl 1):S11–S15. doi: 10.1002/1520-7560(200009/10)16:1+<::aid-dmrr112>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tirziu D, Simons M. Angiogenesis in the human heart: gene and cell therapy. Angiogenesis. 2005;8:241–251. doi: 10.1007/s10456-005-9011-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao R, Brakenhielm E, Pawliuk R, Wariaro D, Post MJ, Wahlberg E, Leboulch P, Cao Y. Angiogenic synergism, vascular stability and improvement of hind-limb ischemia by a combination of PDGF-BB and FGF-2. Nat Med. 2003;9:604–613. doi: 10.1038/nm848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higashi Y, Nishioka K, Umemura T, Chayama K, Yoshizumi M. Oxidative stress, endothelial function and angiogenesis induced by cell therapy and gene therapy. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2006;7:109–116. doi: 10.2174/138920106776597658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lekas M, Lekas P, Latter DA, Kutryk MB, Stewart DJ. Growth factor-induced therapeutic neovascularization for ischaemic vascular disease: time for a re-evaluation? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21:376–384. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000231409.69307.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diener HC, Cunha L, Forbes C, Sivenius J, Smets P, Lowenthal A. European Stroke Prevention Study. 2. Dipyridamole and acetylsalicylic acid in the secondary prevention of stroke. J Neurol Sci. 1996;143:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(96)00308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedulli GF, Lucarini M, Marchesi E, Paolucci F, Roffia S, Fiorentini D, Landi L. Medium effects on the antioxidant activity of dipyridamole. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:295–302. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Venkatesh PK, Pattillo CB, Branch B, Hood J, Thoma S, Illum S, Pardue S, Teng X, Patel RP, Kevil CG. Dipyridamole enhances ischaemia-induced arteriogenesis through an endocrine nitrite/nitric oxide-dependent pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:661–670. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattfeldt T, Mall G. Dipyridamole-induced capillary endothelial cell proliferation in the rat heart--a morphometric investigation. Cardiovasc Res. 1983;17:229–237. doi: 10.1093/cvr/17.4.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Picano E, Michelassi C. Chronic oral dipyridamole as a 'novel' antianginal drug: the collateral hypothesis. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:666–670. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barradas MA, Gill DS, Fonseca VA, Mikhailidis DP, Dandona P. Intraplatelet serotonin in patients with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 1988;18:399–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1988.tb01030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baynes JW. Role of oxidative stress in development of complications in diabetes. Diabetes. 1991;40:405–412. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin KY, Ito A, Asagami T, Tsao PS, Adimoolam S, Kimoto M, Tsuji H, Reaven GM, Cooke JP. Impaired nitric oxide synthase pathway in diabetes mellitus: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine and dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circulation. 2002;106:987–992. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027109.14149.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar D, Branch BG, Pattillo CB, Hood J, Thoma S, Simpson S, Illum S, Arora N, Chidlow JH, Jr, Langston W, Teng X, Lefer DJ, Patel RP, Kevil CG. Chronic sodium nitrite therapy augments ischemia-induced angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7540–7545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711480105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zielonka J, Vasquez-Vivar J, Kalyanaraman B. Detection of 2-hydroxyethidium in cellular systems: a unique marker product of superoxide and hydroethidine. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:8–21. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jude EB, Eleftheriadou I, Tentolouris N. Peripheral arterial disease in diabetes-a review. Diabet Med. 2010;27:4–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishikawa T, Edelstein D, Brownlee M. The missing link: a single unifying mechanism for diabetic complications. Kidney Int Suppl. 2000;77:S26–S30. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hazarika S, Dokun AO, Li Y, Popel AS, Kontos CD, Annex BH. Impaired angiogenesis after hindlimb ischemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus: differential regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1. Circulation research. 2007;101:948–956. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statement ADAC. Peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3333–3341. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang PL. eNOS, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakrabarti S, Vitseva O, Iyu D, Varghese S, Freedman JE. The effect of dipyridamole on vascular cell-derived reactive oxygen species. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:494–500. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.089987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kusmic C, Picano E, Busceti CL, Petersen C, Barsacchi R. The antioxidant drug dipyridamole spares the vitamin E and thiols in red blood cells after oxidative stress. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47:510–514. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00058-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bath PM, Cotton D, Martin RH, Palesch Y, Yusuf S, Sacco R, Diener HC, Estol C, Roberts R. Effect of Combined Aspirin and Extended-Release Dipyridamole Versus Clopidogrel on Functional Outcome and Recurrence in Acute, Mild Ischemic Stroke. PRoFESS Subgroup Analysis. Stroke. 2010 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.564906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiatt WR. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;344:1608–1621. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105243442108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Symons JD, Firoozmand E, Longhurst JC. Repeated dipyridamole administration enhances collateral-dependent flow and regional function during exercise. A role for adenosine. Circulation research. 1993;73:503–513. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.3.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tornling G, Unge G, Skoog L, Ljungqvist A, Carlsson S, Adolfsson J. Proliferative activity of myocardial capillary wall cells in dipyridamole--treated rats. Cardiovasc Res. 1978;12:692–695. doi: 10.1093/cvr/12.11.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waltenberger J. Impaired collateral vessel development in diabetes: potential cellular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Cardiovascular Research. 2001;49:554–560. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Versari D, Daghini E, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Taddei S. Endothelial dysfunction as a target for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 2):S314–S321. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Napoli C, Ignarro L. Nitric oxide and pathogenic mechanisms involved in the development of vascular diseases. Arch Pharm Res. 2009;32:1103–1108. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo JD, Wang YY, Fu WL, Wu J, Chen AF. Gene therapy of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and manganese superoxide dismutase restores delayed wound healing in type 1 diabetic mice. Circulation. 2004;110:2484–2493. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000137969.87365.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Riad A, Westermann D, Van Linthout S, Mohr Z, Uyulmaz S, Becher PM, Rutten H, Wohlfart P, Peters H, Schultheiss HP, Tschope C. Enhancement of endothelial nitric oxide synthase production reverses vascular dysfunction and inflammation in the hindlimbs of a rat model of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:2325–2332. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tie L, Li XJ, Wang X, Channon KM, Chen AF. Endothelium-specific GTP cyclohydrolase I overexpression accelerates refractory wound healing by suppressing oxidative stress in diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E1423–E1429. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00150.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yan J, Tie G, Park B, Yan Y, Nowicki P, Messina L. Recovery from hind limb ischemia is less effective in type 2 than in type 1 diabetic mice: roles of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and endothelial progenitor cells. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2009;50:1412–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paravicini TM, Touyz RM. NADPH oxidases, reactive oxygen species, and hypertension: clinical implications and therapeutic possibilities. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(Suppl 2):S170–S180. doi: 10.2337/dc08-s247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lavi S, Yang EH, Prasad A, Mathew V, Barsness GW, Rihal CS, Lerman LO, Lerman A. The interaction between coronary endothelial dysfunction, local oxidative stress, and endogenous nitric oxide in humans. Hypertension. 2008;51:127–133. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pannirselvam M, Verma S, Anderson TJ, Triggle CR. Cellular basis of endothelial dysfunction in small mesenteric arteries from spontaneously diabetic (db/db −/−) mice: role of decreased tetrahydrobiopterin bioavailability. British journal of pharmacology. 2002;136:255–263. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakagawa T. Uncoupling of the VEGF-endothelial nitric oxide axis in diabetic nephropathy: an explanation for the paradoxical effects of VEGF in renal disease. American journal of physiology. 2007;292:F1665–F1672. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00495.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Fuentes E, Gil-Villarino A, Zafra MF, Garcia-Peregrin E. Dipyridamole prevents the coconut oil-induced hypercholesterolemia. A study on lipid plasma and lipoprotein composition. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2002;34:269–278. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(01)00120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Araujo LI, McFalls EO, Lammertsma AA, Jones T, Maseri A. Dipyridamole-induced increased glucose uptake in patients with single-vessel coronary artery disease assessed with PET. J Nucl Cardiol. 2001;8:339–346. doi: 10.1067/mnc.2001.113615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Balon TW, Nadler JL. Evidence that nitric oxide increases glucose transport in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1997;82:359–363. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.82.1.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim JA, Montagnani M, Koh KK, Quon MJ. Reciprocal relationships between insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction: molecular and pathophysiological mechanisms. Circulation. 2006;113:1888–1904. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.563213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McConell GK, Wadley GD. Potential role of nitric oxide in contraction-stimulated glucose uptake and mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology. 2008;35:1488–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2008.05038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tousoulis D, Tsarpalis K, Cokkinos D, Stefanadis C. Effects of insulin resistance on endothelial function: possible mechanisms and clinical implications. Diabetes, obesity & metabolism. 2008;10:834–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]