Abstract

Extensive studies of the physiological protein—protein electron-transfer (ET) complex between yeast cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP) and cytochrome c (Cc) have left unresolved questions about how formation/dissociation of binary and ternary complexes influence ET. We probe this issue through study of the photocycle of ET between Zn-ProtoporphyrinIX-substituted CcP(W191F) (ZnPCcP) and Cc. Photoexcitation of ZnPCcP in complex with Fe3+Cc, initiates the photocycle: charge-separation ET [3ZnPCcP, Fe3+Cc]→[ZnP+CcP, Fe2+Cc] followed by charge recombination, [ZnP+CcP, Fe2+Cc] → [ZnPCcP, Fe3+Cc]. The W191F mutation eliminates fast hole hopping through W191, enhancing accumulation of charge-separated intermediate and extending the timescale for binding/dissociation of the charge-separated complex. Both triplet quenching and the charge-separated intermediate were monitored during titrations of ZnPCcP with Fe3+Cc, Fe2+Cc, and redox-inert CuCc. The results require a photocycle that includes dissociation/recombination of the charge-separated binary complex and a charge-separated ternary complex, [ZnP+CcP, Fe2+Cc, Fe3+Cc]. The expanded kinetic scheme formalizes earlier proposals of “substrate-assisted product dissociation” within the photocycle. The measurements yield the thermodynamic affinity constants for binding the first and second Cc: KI = 10−7 M−1, KII = 10−4 M−1. However, two-site analysis of the thermodynamics of formation of the ternary reveals that Cc binds at the weaker-binding site with much greater affinity than previously recognized, and places upper bounds on the contributions of repulsion between the two Cc of the ternary complex. In conjunction with recent NMR studies, the analysis further suggests a dynamic view of the ternary complex, wherein neither Cc necessarily faithfully adopts the crystal-structure configuration because of Cc-Cc repulsion.

The complex between the physiological protein—protein electron-transfer (ET) partners, yeast cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP) and cytochrome c (Cc) was the first ET-active complex to be crystallized, and remains a paradigm for ET within a well-defined complex.1 Despite extensive studies of this pair by NMR,2–4 crystallography,5, 6 photo-induced kinetic measurements,7–9 and other spectroscopic techniques,10–12 there nonetheless remain fundamental questions about how ET between them is modulated by the formation and dissociation of the complex on the ET timescale, and about the possible role of a ternary complex in reactivity.4 The pair has been particularly amenable to study because the heme-iron of either partner can be substituted by Zn (or Mg) to form a complex that exhibits an ET photocycle.8 When the Fe of CcP is substituted to form ZnPCcP and is in complex with the iron form of the partner protein, Fe3+Cc, the complex can undergo a laser-initiated ET photocycle comprised of ‘forward’ charge-separation (CS) ET (3ZnPCcP;Fe3+Cc→ZnP+CcP;Fe2+Cc), rate constant kf, to produce the charge-separated intermediate protein pair, ZnP+CcP and Fe2+Cc—denoted I representing all states involving ZnP+CcP—followed by ‘back’ charge-recombination (CR) ET to regenerate the initial state (ZnPCcP;Fe3+Cc←ZnP+CcP;Fe2+Cc) with rate constant kb,13 a process analogous to physiological ET wherein Fe2+Cc reduces CcP Compound ES.

The CR process in the complex formed with ZnP-substituted, wild-type CcP is extremely rapid, kb ~3500s−1 ≫ kf, because CcP residue tryptophan 191 on the proximal side of the heme ‘short-circuits’ direct heme-heme ‘back’ ET via ‘hole hopping’ in which the ZnP+ oxidizes W191 and the W191+• cation radical oxidizes Fe2+Cc. This process makes it difficult to examine the behavior of the CS intermediate, I, and altogether precludes examination of the dynamic processes within I on longer timescales.8, 14–17 To fully explore the role of complex formation/dissociation dynamics in the ET photocycle, we employ CcP W191F; this mutation negligibly perturbs the overall structure of CcP18 and does not impact the ability of Fe3+Cc to quench 3ZnPCcP, but prevents the short-circuit and slows CR.9 The [ZnPCcP(W191F), Fe3+Cc] complex thus is well-suited for studying direct interprotein heme-heme ET, and its use enables us to monitor I over a wide range of timescales.9

In the present study, the charge separated intermediate was monitored through titrations of ZnPCcP by Fe3+Cc, Fe2+Cc, and redox-inert CuCc.19 These studies allow a detailed examination of the dynamics of formation/dissociation of the binary [CcP, Cc] complex, revealing the importance of the charge-separated ternary complex, I3(2+/3+) ≡ [ZnP+CcP, Fe2+Cc, Fe3+Cc].20 These findings are incorporated into an extended kinetic mechanism for the ET photocycle between ZnPCcP(W191F) and yeast Iso-1 Fe3+Cc that formalizes and enhances earlier proposals of “substrate-assisted product dissociation”,21 by incorporation of a dynamic ternary complex.22

The measurements of CS further yield the consensus values of the thermodynamic affinity constants for binding the first and second Cc. However, a two-site analysis of the thermodynamics of formation of the ternary that explicitly incorporates repulsion between the two Cc, reveals that Cc binds at the weaker-binding site with much greater affinity than previously recognized, and places upper bounds on the free energy of repulsion between the two Cc of the ternary complex. In conjunction with recent descriptions of the equilibrium between encounter and docked complexes,23, 24 the analysis further suggests a modified view of the ternary complex’s structure, as a dynamic association of CcP and two Cc wherein neither Cc necessarily adopts the crystal-structure configuration because of Cc-Cc repulsion.

Materials and Methods

Protein preparation

Recombinant yeast cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP) W191F mutant based on the MKT construct and recombinant yeast Iso-1 cytochrome c (Cc) were isolated and purified using previously published protocols.25, 26 Holoenzyme CcP purity was assayed using a 408nm/282nm ratio of 1.3 and SDS-PAGE. ApoCcP was prepared and subsequently reconstituted with Zn-protoporphyrinIX in the dark as previously described27 and purity was assayed using a 432nm/282nm ratio greater than 3 and SDS-PAGE. To prepare metal-free Cc, in a chemical hood, 3–10mL pyridine-HF were added to ~100mg lyophilized FeCc in a polyethylene beaker and gently stirred in the dark with a magnetic stirrer for 10 minutes with a stream of nitrogen blowing over the surface. The reaction was quenched with 10mL of 50mM Acetate buffer, pH 5 and allowed to gently stir for 30 minutes with nitrogen blowing over the surface. Appropriate HF respirators, gloves, laboratory coats, and aprons were used at all times when HF was in use. Excess Fe and pyridine were removed using a short Sephadex G-50 column. Metal-free Cc was diluted by half with water and loaded onto a short Whatman CM52 column equilibrated with 25mM Acetate buffer, pH 5. The column was washed extensively with buffer to remove pyridine and eluted with 25mM Acetate 500mM NaCl buffer, pH 5. CuCc was prepared from metal-free Cc as previously described.28

Kinetic Measurements

Transient absorption kinetics measurements were performed on a laser flash-photolysis apparatus described elsewhere. Wild type and mutant FeCc were freshly oxidized with at least 10-fold excess potassium ferricyanide the day of experiments. Excess potassium ferricyanide was removed by passing the Fe3+Cc and potassium ferricyanide solution through a 2mL CM-52 column preequilibrated with water. Fe3+Cc was eluted using 500mM NaCl, 25mM KPi buffer, pH 7. Proteins were exchanged into potassium phosphate buffers and concentrated using ultracentrifugation. Protein stocks were flushed with argon using a Schlenk line prior to addition and transferred to sample cuvettes using Hamilton gastight syringes 30 minutes before experiments to allow for further oxygen scrubbing. For all samples, the day before experiments, 2.00mL buffer in an airtight quartz cuvette was flushed with argon for 1 hour using a Schlenk line after which a catalase oxygen-scavenging system was added to ensure complete deoxygenation (final concentrations: 10μM catalase, 10μM glucose oxidase, 10μM glucose). Concentrations were determined using ε432nm = 196mM−1cm−1 for ZnPCcP, ε409nm = 106mM−1cm−1 ε416nm = 129mM−1cm−1 for Fe3+Cc and Fe2+Cc respectively, and ε422nm = 138mM−1cm−1 for CuCc.

Model Simulation and Fitting

Global fits of titration kinetic traces to analytical expressions and numerical fits to the set of kinetic differential equations were calculated with MATLAB using routines written in-house. Numerical integration of the set of differential equations for Scheme 1 employed the MATLAB ode45 solver (which uses the explicit Runge-Kutta (4,5) formula, Dormand-Prince pair). The 95% confidence intervals for the kinetic parameters were calculated with the built-in nlparci function in MATLAB. Details of the differential equations and global fitting equations are presented in SI.

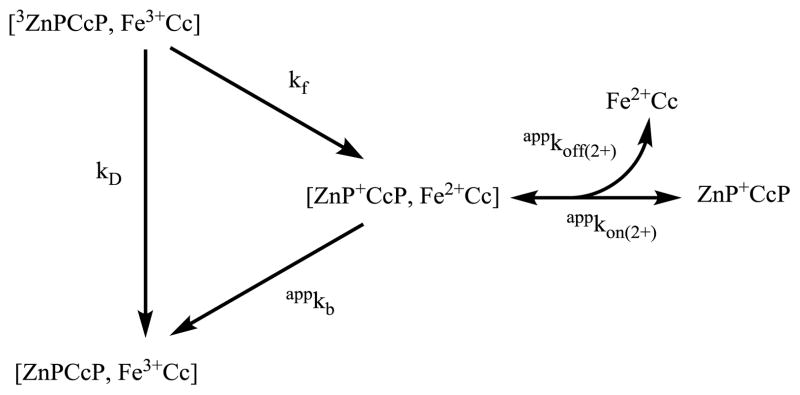

Scheme 1.

Results

Low salt (10mM KPi) Fe3+Cc titration

ET Quenching

Fe3+Cc was titrated into a sample of ~5μM ZnPCcP(W191F) in 10mM KPi buffer, pH 7 at 20 C. In the absence of Fe3+Cc, 3ZnPCcP decays exponentially with k1 ≈ 90s−1. With further additions of Fe3+Cc, the triplet state decay traces can be described with a double exponential function with decay constants, k1 ≈ 90s−1 and k2 ≈ 320s−1 and respective fractions, f1 and f2 with initial amplitude A0.29 As long as 0 < Fe3+Cc < [ZnPCcP]0, k1 and k2 are nearly unchanging while f2 increases nearly linearly, as appropriate for a tightly-bound 1:1 complex in slow exchange with its dissociated components;30 at the titration endpoint, when [Fe3+Cc] ≈ [ZnPCcP]0, and the formation of a binary is roughly complete (f2 ≈ 1), the triplet decay is approximately exponential with k2 ~ 320s−1. However, past this point, when [Fe3+Cc] >[ZnPCcP]0, the triplet decay again becomes biexponential with the appearance of a faster phase, decay constant k3, associated with the formation of a 2:1 complex in slow exchange with the 1:1 complex, with enhanced quenching in the ternary: ternary quenching rate constant, k3 > k2. A correlation between the yield of charge-separated intermediate (see below) and the rate constant for quenching suggests than much of the quenching in the ternary is by energy transfer.

To incorporate both binary and ternary complexes, the triplet decay traces were fit with a triple exponential function, Fig S1, which corresponds to a model in which equilibrium populations of free, 1:1, and 2:1 complexes are in slow exchange and decay independently. To test this protocol and to further reduce the total number of fit parameters, the entire set of triplet decay traces was also fit globally to rate constants, k1, k2, and k3, and affinity constants, KI and KII. Although the two fitting approaches give comparable values, the confidence intervals for the global approach are better (smaller). The values of the rate constants and affinity constants obtained in this fashion are given in Table 1, and are consistent with previous reports.8, 9

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for global triple exponential fits of the triplet decay traces during a Fe3+Cc titration shown with 95% confidence intervals.

| k1 | 89.7 ± 0.2 s−1 |

| k2 | 297 ± 0.7 s−1 |

| k3 | 1190 ± 63 s−1 |

|

| |

| KI | 2.3 ± 0.2 ×107 M−1 |

| KII | 9.2 ± 0.3 ×103 M−1 |

Charge-Separated Intermediate

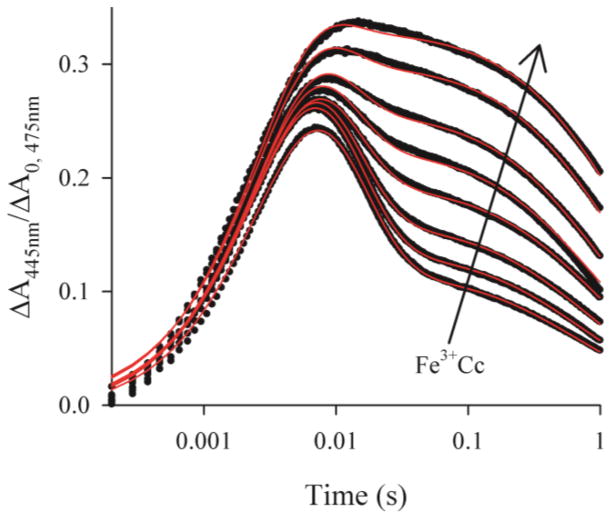

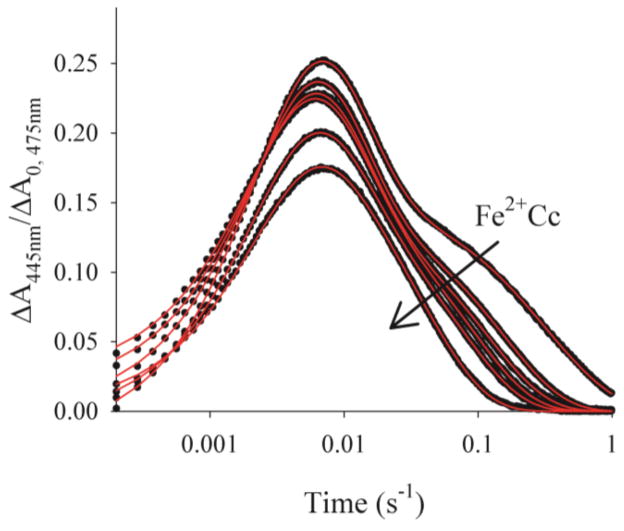

The progress curves of the charge-separated intermediate state (I) were followed through an Fe3+Cc titration by monitoring the transient absorbance upon photolysis at a 3ZnPCcP - ground isosbestic, 445 nm, a wavelength where both the (ZnP+CcP - ZnPCcP) and (Fe2+Cc – Fe3+Cc) absorbance differences contribute to the transient absorbance. As with the quenching measurement, the behavior of I is not consistent with a simple 1:1 stoichiometry in slow exchange. If charge separation and recombination occurred as a simple, intracomplex photocycle, one would expect a simple exponential rise and fall for the absorbance of I, with unchanging rate constants throughout the titration, one corresponding to the intracomplex triplet decay constant, the other to intracomplex CR associated with the return of I to ground; only the signal amplitude would change during a titration.

Instead, although we observe an increase in the maximum accumulation of I31 the shapes of the progress curves for I are complex, with an apparently exponential rise and biphasic fall, one exponential phase decaying within ~50 ms, the other, a second order phase, decaying only over 1 s or longer, with the proportions of the slower phase increasing during the course of the titration, Fig 1. Throughout the titration, plots of the reciprocals of the absorbance-difference are linear at times where it is dominated by the slow component, Fig 2, which shows that this phase of CR is second order. Indeed, any description of the slow phase in the recovery of the ground state must incorporate dissociation and recombination of I: the complex could not remain bound for the duration of the intermediate signal, ~1–2 seconds. For I to remain just 90% bound for at least 1 second, the dissociation rate constant would need to be ≤ 0.1s−1, which is two orders of magnitude smaller than that calculated using the measured binding constant, KI = 2 × 107 M−1, and the reported association rate constant of at least kon ~108M−1s−1.32

Figure 1.

Titration of a sample ~5μM ZnPCcP with Fe3+Cc (5–26μM). Progress curves for the charge-separated intermediate (black) normalized to A0 for the corresponding triplet decay curves with fits to Scheme 1 (red) Conditions: 10mM, pH 7 KPi buffer, 20C.

Figure 2.

Titration of a sample ~5μM ZnPCcP with Fe3+Cc (5–26μM). Reciprocal-absorbance plots of the progress curves for charge separation measured at 445nm.

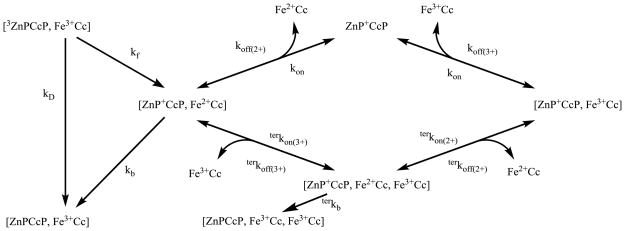

The results to this point indicate that two extensions of the simple photocycle are required. The results of the Fe3+Cc quenching titration clearly indicate the formation of a ternary complex in the triplet state, and thus presumably in I as well; the behavior of the CR shows that the description must furthermore incorporate dissociation and reassociation of the charge-separated intermediate complex, [ZnP+CcP, Fe2+Cc] ≡ I2(2+). However, these ‘simple’ extensions profoundly complicate the kinetic scheme for a photocycle. A full kinetic scheme that incorporates binary and ternary complexes of the triplet state and I, as well as dissociation/reassociation of each species in all possible combinations, is presented in Scheme S1. This scheme includes 18 species, 36 equilibrium processes, and at least six ET processes. Clearly, it is not practicable to determine all the parameters in such a scheme. However, it is possible to assess the roles of dissociation and of the ternary charge-separated complexes on the CR process, and determine key kinetic parameters by considering successively more complex sub-schemes extracted from Scheme S1, beginning with a minimal kinetic sub-scheme described previously,9 Scheme 1, and then including additional kinetic routes as needed to arrive at a core model, Scheme 2 below, that captures the key features needed to describe the progress curve for I.

Scheme 2.

Minimal kinetic scheme

To begin, we recognize that although a full fit to the triplet decay traces requires a 2:1 binding model, the majority of bound 3ZnPCcP exists as the binary complex even at the highest [Fe3+Cc]. Therefore, Scheme 1 includes only the dominant channel for intracomplex photo-initiated CS, [3ZnPCcP, Fe3+Cc]→[ZnP+CcP, Fe2+Cc]. The present measurements cannot yield meaningful parameters values for minor channels, as the small contributions from such channels are overwhelmed by the smallest deviations from the triplet/ground isosbestic, where the measurements must be made, and where the absorbance difference for I is not maximal. Once formed, I2(2+) can undergo intracomplex CR, rate constant appkb, but also is free to dissociate Fe2+Cc with the apparent dissociation rate constant, appkoff(2+), and recombine with the association rate constant, appkon(2+).

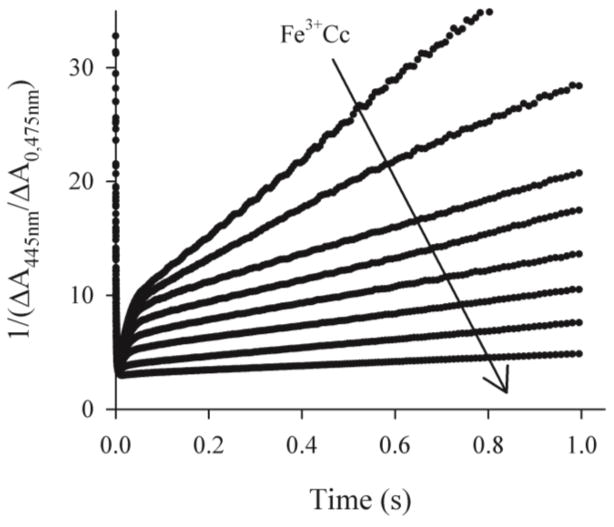

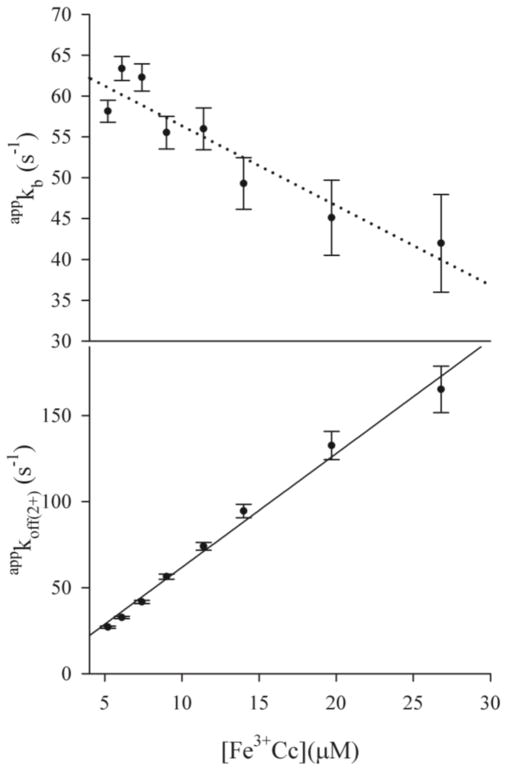

Each individual progress curve for I collected during an Fe3+Cc titration can be well fit to Scheme 1 using numerical integration of the corresponding equations (SI), as shown in Fig 1. Moreover, as required, in the fit of each trace, the rate constant for the appearance of I, krise = 310±12s−1 corresponds to the rate constant, k2, for the decay of the triplet state in the bound complex. However, during a titration up to the addition of five equivalents of Cc per ZnPCcP, the fit parameter appkoff(2+) increases linearly, by a factor of six, while appkb decreases by 1/3, from ~60s−1 to ~40s−1, Fig 3, with the main changes occurring well beyond the point where ZnPCcP is fully bound. The fits to Scheme 1 further yield a systematic decrease in appkon(2+) from ~1.4×107M−1s−1 to ~8×106M−1s−1. However, a large uncertainty introduced by the limitation of data collection to 1 s, before all the intermediate has recombined, precludes detailed analysis. If Scheme 1 were adequate to describe the behavior of I, all three rate constants, appkb, appkoff(2+), and appkon(2+), would remain invariant during the titration—only the amplitude of the signal would change, rising with the fraction of bound complex, and this would reach an unchanging maximum when all ZnPCcP is complexed. The progress curves for I show none of these characteristics.

Figure 3.

Titration of a sample ~5μM ZnPCcP with Fe3+Cc (5–26μM). (Top) appkb through the titration. Dotted line to guide the eye. (Bottom) appkoff(2+) through the titration with fit of to eq 2 (black line). Conditions: 10mM, pH 7 KPi buffer, 20C.

The changes in CR rate constants beyond complete formation of the 1:1 complex instead reflect the presence of a ternary charge-separated complex, and thus complement the finding that a description of triplet quenching requires the presence of a ternary photoexcited complex. To understand how to incorporate a ternary charge-separated complex into Scheme 1, it is important to consider all the processes that the binary charge-separated complex, I2(2+), can undergo following its formation through the dominant CS process. If this complex dissociates before CR can occur, the free ZnP+CcP thus formed must rebind Fe2+Cc in order to undergo CR, but instead it can bind Fe3+Cc, which acts as an ‘inhibitor’ of charge recombination by taking the place of the Fe2+Cc (the equilibrium binding constants for the association of Fe3+Cc and Fe2+Cc with WT CcP are similar33). Such an inhibited complex can further bind a second Fe3+Cc to form a ‘doubly-inhibited’ ternary inhibitor [ZnP+CcP, (Fe3+Cc)2] ≡ I3(3+/3+); it is the progressive accumulation of these species with increasing [Fe3+Cc] that acts to slow CR.

In addition to undergoing CR or dissociating, I2(2+) also can bind an Fe3+Cc to form the I3(2+/3+) ternary complex. There are multiple possible alternative structures of such a ternary complex. Depending on the CR pathways within such a ternary, and on the probabilities of releasing Fe3+Cc to reform I2(2+), or of releasing Fe2+Cc to form I2(3+), formation of I3(2+/3+) could either enhance or a suppress CR as revealed by changes in appkoff(2+) and appkb beyond one equivalent of [Fe3+Cc]. To address these issues, two types of ‘competition’ titrations were performed.

Fe2+Cc Titration

Assignment of the slower decay phase of I to accumulation of the ‘inhibited’ complex I2(3+), which cannot undergo CR, implies that addition of excess Fe2+Cc should enhance the regeneration of the ET-active I2(2+), thereby speeding CR and decreasing the lifetime of I. To examine this prediction, Fe2+Cc was titrated into a 1:1 mixture of ~5μM ZnPCcP, ~5μM Fe3+Cc (pH 7 KPi buffer, 20C), to a final concentration of 22μM added Fe2+Cc. The fraction of photoexcited 3ZnPCcP bound in complex with Fe3+Cc, Fig S2, as determined from biexponential fits of the triplet decay traces with rate constants k1 and k2, Fig S3, decreased throughout the titration, establishing that Fe3+Cc and Fe2+Cc bind to ZnPCcP/3ZnPCcP with similar affinities.

The excess Fe2+Cc also alters the time course for the I, Fig 4. The trace for I generated without addition of Fe2+Cc, which reproduces the corresponding trace of Fig 1 above, exhibits a slow phase of roughly 50% of the signal. As expected, progressive additions of Fe2+Cc decrease the intensity of the signal for I, but have little effect on its rate of appearance, krise = 370 ± 16s−1 which corresponds to the unvarying rate constant for triplet decay, k2. However, added Fe2+Cc obviously suppresses the slow component of CR, as anticipated.34

Figure 4.

Titration of a sample ~5μM ZnPCcP, ~5μM Fe3+Cc with 0–17μM Fe2+Cc. Progress curves for the charge-separated intermediate, I, normalized to A0 of the corresponding decay at 475nm (black) with fits to Scheme 1 (red). Conditions: pH 7.0, 10mM KPi, 20C.

In fits of these curves to Scheme 1 the ‘intracomplex’ CR rate constant appkb, associated with the more rapidly decaying phase decreases by ~ 1/3 (from ~60s−1 to <40s−1, Fig S4), while the suppression of the slow component is manifest as a speeding up of decay with the result being that the more slowly decaying component coalesces with the other, Fig 4. The observation that increasing [Fe2+Cc] speeds up CR confirms the basic tenet of Scheme 1, that I2(2+) dissociates, and that the slow CR phase is rate-limited by recombination of Fe2+Cc with ZnP+CcP. Likewise, the apparent decrease in the intracomplex CR rate constant appkb with increasing Fe2+Cc suggests that I2(2+) can bind a second Fe2+Cc, forming a ternary I3(2+/2+) ≡ [ZnP+CcP, (Fe2+Cc)2] complex. Apparently as a paradox, the binding of the second Fe2+Cc electron donor acts to decrease the net rate constant associated with Fe2+Cc → ZnP+CcP charge-recombination ET. This, however, simply implies that neither Fe2+Cc in I3(2+/2+) adopts the favorable bound conformation of the ET-active I2(2+) binary complex, while the observation that the fast phase that decays exponentially indicates that I2(2+) and I3(2+/2+) are in rapid exchange. As discussed in more detail below, a parallel decrease of appkoff(2+) with [Fe2+Cc], Fig S5, in contrast to an increase with [Fe3+Cc] (see above) and [CuCc] (below), is further evidence of the inhibiting effect of the latter two Cc. As with the Fe3+Cc titration, the appkon(2+) values could not be further analyzed.

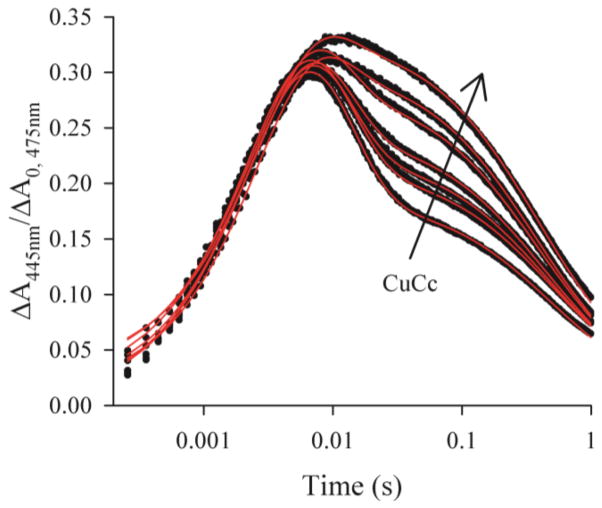

CuCc Titration

To test whether the increases in appkoff(2+) during the titration with Fe3+Cc and Fe2+Cc are caused exclusively by formation of the ternary complex through binding of an inert Cc, and not in some part through a self-exchange between bound Fe3+Cc and Fe2+Cc, we performed an analogous titration with redox-inert CuCc.19 CuCc was titrated into a sample ~5μM ZnPCcP, ~7μM Fe3+Cc (pH 7, KPi buffer, 20C), to a final concentration of ~16μM CuCc. Inspection of the triplet decay traces, Fig S6, shows a small increase in the lifetime of 3ZnPCcP, an indication that the inert CuCc was replacing Fe3+Cc in the photoexcited complex, but the effect is too small to precisely quantify. The overall behavior of I during a titration with CuCc, Fig 5, is similar to that during the Fe3+Cc titration, Fig 1, with krise = 300 ± 20s−1. However, fits of the I time courses with Scheme 1 reveal that as with the Fe3+Cc, appkoff(2+) increases linearly with progressive additions of CuCc, Fig S7, establishing the formation of the ternary complex, I3(2+/Cu) ≡ [ZnP+CcP, Fe2+Cc, CuCc]; again appkon(2+) values were not further analyzed. We observe a modest, but significant decrease in appkb with increasing CuCc, Fig S8, directly confirming that in the ternary complex the presence of the second, nonreactive Cc makes the Fe2+Cc less reactive. We return to this finding in Discussion.

Figure 5.

Titration of a sample ~5μM ZnPCcP, ~7uM Fe3+Cc with 0–16μM CuCc. Progress curves for the charge-separated intermediate, I, normalized to A0 of the corresponding decay at 475nm (black) with fits to Scheme 1 (red). Conditions: pH 7.0, 10mM KPi, 20C.

Core Kinetic Scheme

The experiments described above yield mechanistic constraints to guide expanding Scheme 1 to develop a core kinetic model of the ET photocycle for Fe3+Cc and ZnPCcP(W191F) as these proteins form dynamic binary and ternary complexes whose dissociation and combination occurs on the long timescale of direct heme-heme ET in the CcP(W191F), FeCc complexes. These constraints and the modification that follow may be summarized:

Dissociation/reassociation competes with ET during charge recombination; Scheme 1 includes dissociation of the binary CS intermediate, I2(2+).

The ZnP+CcP liberated upon dissociation of I2(2+), can bind Fe3+Cc to form the ‘inhibited’ complex, I2(3+), slowing the second order recombination process of the slow CR component;. Scheme 1 must be extended to include formation of I2(3+) ≡ [ZnP+CcP, Fe3+Cc].

An MCc (M=Fe2+, Fe3+, Cu) can interact with I2(2+) to form a ternary complex whose structure is less suited for ET than is that of the binary complex; to describe the ‘normal’ titration of ZnPCcP by Fe3+Cc, Scheme 1 must be modified to include the formation of the ternary complex, I3(2+/3+), which is allowed to dissociate either one of the Cc to form one of two binary complexes, I2(2+) or I2(3+).

Scheme 2 presents a core kinetic model for the ZnPCcP(W191F) and Fe3+Cc ET photocycle that incorporates these features, and in fact represents a subset of Scheme S1: kon and koff(2+/3+) are the association and dissociation rate constants, respectively, for the binary complexes; terkon(2+/3+) and terkoff(2+/3+) are rate constants for formation and dissociation of the ternary complex; all are provisionally taken to be identical for the photoexcited and charge-separated complexes but unique for each Fe2+Cc and Fe3+Cc. Again, the CR rate constant for the binary is kb; in principle the ternary can also undergo CR, rate constant terkb. The scheme does not explicitly include the I3(3+/3+) complex because it is not kinetically differentiable from the ‘inhibitor’ complex, I2(3+). Analogous schemes for the Fe2+Cc and CuCc titration ET photocycles are given by Schemes S2 and S3.

In Scheme 2, I2(2+) can dissociate after photoinitiated CS ET, with rate constant, koff(2+), and the liberated ZnP+CcP is free to bind nonreactive Fe3+Cc molecules, thereby forming the ‘inhibitor’ complex, I2(3+),35 and given that [Fe3+Cc] ≫ [ZnP+CcP], we infer that ZnP+CcP spends the majority of the time in complex. Alternatively, I2(2+) can bind a second Fe3+Cc molecule to generate the ternary complex, I3(2+/3+), which can dissociate either Cc, reforming I2(2+) or the inhibited binary complex, I2(3+). This process effectively enhances the apparent rate of dissociation of Fe2+Cc from I2(2+) by providing an additional route to form the inhibited complex, I2(3+), and it causes the concentration-dependent increase of the apparent rate constant, appkoff(2+), for CuCc and Fe3+Cc, but decrease for Fe2+Cc, as noted above, amplifying the slow phase of CR.

Even an attempt to fit titration data with Scheme 2, a sub-scheme of the full kinetic Scheme S1, presents formidable difficulties because of the large number of parameters and the impossibility of independently monitoring the individual ZnP+CcP species within Scheme 2: transient absorbance spectroscopy monitors only the sum of the charge-separated species. However, we can obtain parameters partially describing Scheme 2 by identifying them with the parameters obtained by fitting the progress curves to Scheme 1. The two critical parameters in Schemes 2, S2, and S3 are koff(2+) and terkon(M), (M = Fe2+, Fe3+, Cu), the rate constants for the processes that form the species, ZnP+CcP and [ZnP+CcP, Fe2+Cc, MCc] ≡ I3(2+/M) respectively, which represent the slower decay phase. Perhaps surprisingly both a dissociation and an association constant can be obtained from the two parameters that describe the linear dependence of the apparent rate constant for the dissociation of I2(2+) of Scheme 1 (denoted appkoff(2+),) on the concentration of added titrant, [MCc]0, as found in the fits to Scheme 1. The correlation can be written as follows.

| (1) |

Firstly, the concentration of titrant MCc is much greater than the concentration of I2(2+) at all times during a photocycle, [MCc] ≫ I2(2+), so one may equate the instantaneous value of free [MCc] with the total concentration, [MCc] ≈ [MCc]0. As a result, within Scheme 2 the formation of the ternary complex, I2(2+) + MCc → I3(2+/M), is pseudo-first order. Secondly, this formation of I3(2+/M) manifests itself through the description of the titrations with Scheme 1 as a contribution to the apparent rate constant for I2(2+) dissociation that increases with [MCc]0 during a titration, Δappkoff(2+) = terkon(M)[MCc]0. Addition of this contribution to the true rate constant for dissociation, koff(2+), leads to eq 1.36.

The variations of appkoff(2+) with [MCc]0 obtained through analysis of the Fe3+Cc and CuCc titrations with Scheme 1 and their description with eq 1 yields the values of terkon(M) shown in Table 2. These dissociation rate constants for the ternary complexes are approximately the same, confirming that the formation of a ternary complex is the cause of the concentration dependence of the apparent dissociation of the binary complex, appkoff(2+).

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for linear fits of appkoff(2+) values from fits using Scheme 1 with 95% confidence intervals

| Protein titrant | terkon(M) (M−1s−1) |

|---|---|

| Fe3+Cc | 6.6 ± 0.7 × 106 |

| CuCc | 6.9 ± 0.2 × 106 |

Discussion

Introduction of the W191F mutation greatly slows the CR ‘half’ of the ET photocycle associated with the [ZnPCcP, Fe3+Cc] complex by eliminating fast hole-hopping from Fe2+Cc to the ZnP cation radical in ZnP+CcP through W191.9 This mutation both enhances the accumulation of the CS intermediate, I, and greatly extends the timescales over which binding/dissociation of this paradigmatic protein-protein ET pair can be probed through ET photocycle measurements. This study reports progress curves for the triplet decay and charge-separated intermediate curves of the titration of ZnPCcP(W191F) with Fe3+Cc, as well as titrations of the [ZnPCcP, Fe3+Cc] complex at fixed concentration with Fe2+Cc and with CuCc. The results of these experiments require an expansion of the CR branch of the simple photocycle for intracomplex ET between ZnPCcP(W191F) and Fe3+Cc (Scheme 1) to incorporate (i) dissociation/recombination of the charge-separated intermediate state; (ii) two types of binary intermediate complex, the reactive intermediate, I2(2+), and the ‘inhibited’ complex, I2(3+); (iii) the ternary intermediate complex in which ZnP+CcP binds both Fe2+Cc and Fe3+Cc, I3(2+/3+), Scheme 2. Incorporation of this expanded CR scheme within the ET photocycle formalizes and expands earlier proposals to explain apparently anomalous kinetic and binding measurements,21, 37 and further allows us to introduce a distinctive perspective on the structure of the ternary CS complex.

An early proposal suggested that “substrate-assisted product dissociation” added a concentration-dependent term to the dissociation of Cc from CcP.21 Such a term offered an explanation for observed steady-state turnover rates at high protein concentrations that were greater than the dissociation rate constants reported at low concentrations. Those results yielded a [Cc]-dependent, second order dissociation rate constant in agreement with an earlier proton NMR study37 that observed concentration-dependent exchange rates between free Cc and Cc bound to CcP: an increase in absolute protein concentration at constant CcP:Cc ratio shifted the exchange from slow-exchange on the NMR timescale, to fast-exchange.37 The present measurements of the CS recombination kinetics show a corresponding concentration-dependent increase of the apparent rate of dissociation of the binary CS complex, I2(2+)

Stopped-flow measurements22, 38 also were interpreted in terms of a concentration-dependence of the apparent dissociation of the binary complex, caused by transient formation of the ternary complex in which binding at the reactive site is decreased by repulsion between bound Cc. The detailed kinetic Scheme 2 correspondingly incorporates the reaction between I2(2+) and an additional Fe3+Cc to form the weakly bound ternary complex, I3(2+/3+), which is free to release either Fe2+Cc or Fe3+Cc. When the kinetics of charge recombination are interpreted within the contracted kinetic Scheme 1, which does not explicitly include the I3(2+/3+), the influence of the additional channel for liberating Fe2+Cc by dissociation from the ternary complex is manifest as an enhancement of the apparent dissociation constant of I2(2+), and leads to the appearance of “substrate-assisted product dissociation”.21 However, to understand these results and most especially the the strength and effects of Cc repulsion within the ternary complex, it is necessary to incorporate the contributions of repulsion into the thermodynamics of binding within a two site binding model.

Thermodynamics of Two-Site Binding

It is well-known that binding measurements for a system that includes binary and ternary complexes provide only two thermodynamic affinity constants.39 These can be formulated as one constant for the binding to CcP of one Cc to form a binary, KI, the second constant for the binding of a second Cc to form the ternary, KII with corresponding free energies ΔGI and ΔGII, respectively.

| (2) |

| (3) |

Alternatively, the second constant can be defined as that for the direct binding of two Cc by CcP, affinity constant KT = KIKII, a formulation that is seen below to be particularly useful for the present discussion.

| (4) |

It is also well known that the two constants KI and KII of eqs 2 and 3 are not site binding constants,39 nor do they imply any specific binding model. Nonetheless, it is also well known that the thermodynamic formulation formally corresponds to independent binding at two pre-existing sites, 1 and 2, with binding constants, K1 and K2, where KI = K1 + K2 and KII = K1K2/(K1+K2)40 whether or not the system is physically represented by this model. In fact, calculations and experiments have confirmed that the two Cc cannot bind independently, and that the stability of the ternary is diminished by electrostatic repulsions between the two positively charged Cc (anti-cooperative binding).41, 42

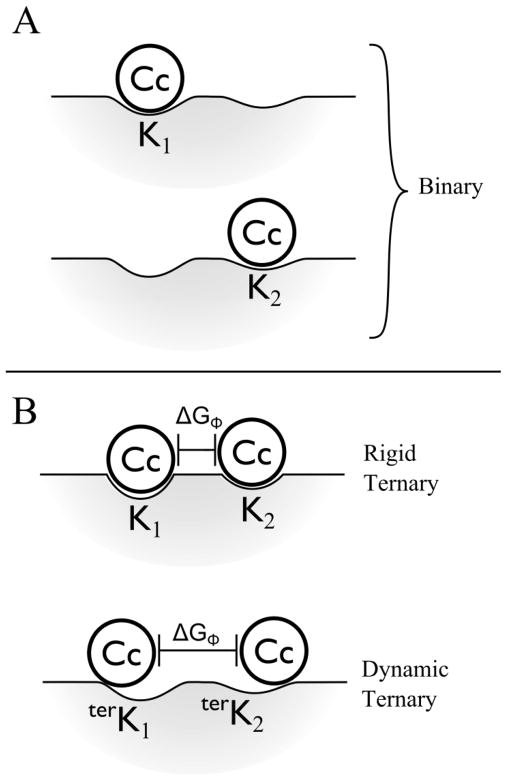

To describe the thermodynamics of two-site binding of two Cc by Ccp we consider two CcP binding sites, 1 and 2, where Cc can bind to form alternative binary complexes with true site constants, K1 and K2 respectively, and with binding free energies ΔG1 and ΔG2,

| (5) |

as illustrated in Fig 6A. Regarding the formation of the ternary. (i) Electrostatic repulsion between the two bound Cc molecules of the ternary complex necessarily causes the binding to be ‘anti-cooperative’ and can be captured by explicitly introducing a free energy of repulsion (ΔGΦ>0) into the free energy for formation of the ternary complex from its unbound components (Eq 6, ΔGT).

Figure 6.

Representations of Cc bound to the surface of CcP within the binary and ternary complexes. A) Two unique binary complexes with equilibrium affinity constants, K1 and K2. B) Rigid and dynamic models of the ternary complex with incorporated free energy of repulsion, ΔGΦ.

| (6) |

(ii) The free energies of binding a Cc to the CcP surface at each site within the ternary complex need not have the same values as for the two binary complexes, namely, in general ΔGi ≠ terΔGi. This is so because upon binding of a second Cc to CcP, the binding geometries at both sites and even the protein charges can adjust so as to create the most stable ternary complex: in minimizing the total free energy of the ternary, ΔGT, a diminution in binding free energies to the CcP surface can be more than compensated by mitigation of the repulsion, as shown in Fig 6B. Stated differently, the ternary can lose free energy of interfacial binding interactions, but benefit overall by a more than compensating decrease in repulsion.

To understand the role of repulsions in the ternary complex between CcP and Cc quantitatively, it is nonetheless useful to first consider anti-cooperative binding in the rigid limit of the two-site model, where the site binding constants, K1 and K2, are assigned as being unchanged upon binding of a second Cc, and thus the site-binding free energies within the ternary complex (terΔGi, I = 1, 2) are assigned to equal those within the binary complexes, ΔGi = terΔG,I, Fig 6B. Anticooperativity is introduced by repulsion between the two Cc, decreasing KII, through the incorporation of a repulsion factor Φ = e−ΔGΦ/RT. In this limit, the relationship between the measured affinity constants, KI and KT, and the site-affinity constants, K1 and K2, and the free energy for forming the ternary complex from its components, then become

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

Kinetic measurements and mutagenesis, both in our laboratory8, 43–45 and others’12, 46–48 generally arrived at measured affinity constants for the ‘first’ and ‘second’ Cc, which correspond to thermodynamic constants of KI ~ 107 M−1, KII ~ 104 M−1 at 10mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7 20C, values corroborated in the present study. Use of these consensus values permits us to discuss the actual site constants and to set limits on the repulsion free energy.

That the crystal and NMR49–51 structures reveal a 1:1 CcP/Cc complex with similar conformations would seem to suggest that one binding site (site 1) is overwhelmingly more favorable that any second site. However, in the extreme case of this rigid limit, if the site constants were equal to the measured thermodynamic affinity constants (K1 ≈ KI and K2 ≈ KII), then repulsion would be zero, and this is ruled out by the measurements of Erman and coworkers,42 as noted above. This requires that the actual site-binding constant K2 must be larger than the measured value of KII = 104, although still enough smaller than K1 that the binary is predominantly in the tightly-binding form in accordance with the NMR studies.50 We propose that if K2 were merely 10-fold less than K1, rather than the 103-fold that would apply if one inappropriately assigned K2 = KII, then it is likely that the binary complex with binding at site 1, the ‘tight’ site, would dominate both the crystallization process that led to the X-ray structure, as well as the solution structures. If we then use this assumption within eqs 7 and 8 for concreteness, yielding the plausible value, K2 ~ 106, then one arrives at a calculated repulsion constant of Φ≈10−2, corresponding to ΔGΦ = 2.7 kCal/mol. If one further relaxes the rigid limit two-site model, allowing the Cc at each site within the ternary complex to adjust its binding conformation relative to that of the binary, this further lowers the possible influence of repulsions. Such relaxation leads to the inequalities, terK1 < K1 and/or terK2 < K2; through eq 7 this in turn would correspondingly reduce the free energy of repulsion, ΔGΦ < 2.7 kCal/mol.

We may conclude this discussion by noting that eq 7 places an upper limit to the affinity at the weaker-binding site, K2 = K1 = KI/2 = 5×106. This limiting value in turn leads to an absolute upper bound to the repulsion free energy in any two site model, through use of eq 8. Use of the consensus measured thermodynamic affinity constants and this upper bound to K2 within the rigid-limit two-site model gives an upper bound to the repulsion free energy at 10mM KPi buffer, pH 7, 20C: ΔGΦ ≤ 3.3kCal/mol; this is an absolute upper bound, as relaxation of the rigid limit would only lower this value. The experiments designed to probe the repulsion free energy, which employed a ternary that constrains the movement of one Cc, yielded a free energy for the repulsion between the two Cc of ΔGΦ = 6 kCal/M, roughly twice the actual upper limit for the non-covalent ternary revealed by the present thermodynamic analysis.42 However those experiments were conducted at lower ionic strength, and higher pH and temperature (10mM ionic strength KPi buffer, pH 7.5 and 25C), all of which differences would enhance repulsion. Thus, we suggest that the two measurements are satisfactorily supportive.

The Nature of Binary and Ternary Complexes

Despite the beautiful visualization of complementary docking between CcP and Cc provided by the crystal structure, there is good reason to believe that this structure is actually a member of an ensemble of solution binding configurations, as suggested long ago by Brownian dynamics simulations.46 Such a situation was supported by the “Velcro” model in which a large surface region, or charged patch, on CcP participates in complex formation.52 and most persuasively, has recently been underscored by the NMR studies of Ubbink and co-workers, who found that within the binary complex, Cc spends up to 30% of the time in an encounter complex with CcP as a collection of non-specific binding configurations around the ‘tight’ site.23 Consistent with this view, small and subtle changes in the binding surfaces of Cc and CcP introduced by point mutations significantly change the structure of the docked complex.6 Collectively, these measurements lead to an expanded, more dynamic view of the association between CcP and a single Cc in solution. The present thermodynamic analysis of binding extends such ideas by showing that the second binding site has a much greater affinity than previously recognized. Stronger second-site binding would in turn contribute to a broader ensemble of binary structures.

Combining the analysis of affinities with the kinetic measurements of the charge-recombination process, further contributes to our understanding of the structure of the ternary, and to the view that it is even more dynamic than the binary, and that the most-probable binding sites/geometries for the two Cc not necessarily identical to those most characteristic of the alternative binaries. This picture is supported by the present experimental observation that increasing concentrations of MCc not only increase appkoff(2+), but also decrease appkb. If the two Cc within the ternary complex, I3(2+/3+) or I3(2+/Cu), were situated as in the corresponding binary complexes, the value appkb would remain constant, contrary to observation; only appkoff(2+) (and possibly appkon) would change. Instead, the presence of both binary and ternary complexes (I2(2+) and I3(2+/3+)) in rapid exchange generates an observed appkb that is a weighted average of kb and terkb. The finding that appkb decreases with increasing concentration of the ternary indicates that the presence of the second Cc forces the Fe2+Cc to bind in a less-reactive conformation than in the binary complex, and the inequality, 0 < terkb < kb. 53

In conclusion, we have developed a generalized kinetic scheme for the ET photocycle of the complex between ZnPCcP(W191F) and Fe3+Cc that formalizes, expands, and revises the picture of the kinetic behavior and structure of the charge-separated intermediate. The resulting kinetic Scheme 2 incorporates binary complexes in two different redox states, I2(2+), I2(3+), along with a ternary complex, I3(2+/3+), and accounts for the dynamics of complex interconversion over timescales from μsec to sec. In formalizing and enhancing earlier proposals of “substrate-assisted product dissociation”, we have developed a thermodynamic description of two-site binding which reveals that Cc binds at the weaker-binding site with much greater affinity than previously recognized, and places upper bounds on the contributions of repulsion between the two Cc of the ternary complex. In conjunction with recent NMR studies, the analysis further suggests a dynamic view of the ternary complex, wherein neither Cc necessarily faithfully adopts the crystal-structure configuration because of Cc-Cc repulsion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Institute of Health (HL 63203)

We thank Dr. Judith Nocek and Dr. Diana Mayweather for many useful discussions and Dr. John Magyar for providing protocols used in the preparation of CuCc. We further acknowledge two anonymous reviewers, whose incisive comments and suggestions directly led to major improvements in this report.

Abbreviations

- ET

Electron Transfer

- CcP

Cytochrome c Peroxidase

- Cc

Cytochrome c

- ZnPCcP

Zn-ProtoporphyrinIX-substituted CcP

- CS

Charge-Separation

- CR

Charge-Recombination

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Triplet decay curves with fits for the Fe3+Cc titration, fit parameters for Fe2+Cc and CuCc intermediate progress curves to Scheme 1, extended and modified kinetic schemes used to analyze Fe2+Cc and CuCc titration intermediate curves, comparisons of triplet decay rate constants for the Fe2+Cc titration, and details of equations for the global triple exponential equation and the system of differential equations used in Schemes 1 are provided in the supplementary information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Bendall DS. Protein electron transfer. BIOS Scientific Publishers; Oxford: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satterlee JD, Moench SJ, Erman JE. A proton nmr study of the non-covalent complex of horse cytochrome {ic} and yeast cytochrome-{ic} peroxidase and its comparison with other interacting protein complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1987;912:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(87)90251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yi Q, Erman JE, Satterlee JD. {+1}h nmr evaluation of yeast isozyme-1 ferricytochrome {ic} equilibrium exchange dynamics in noncovalent complexes with two forms of yeast cytochrome {ic} peroxidase. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:1981–1987. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkov AN, Nicholls P, Worrall JA. The complex of cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase: The end of the road? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:1482–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pelletier H, Kraut J. Crystal structure of a complex between electron transfer partners, cytochrome c peroxidase and cytochrome c. Science. 1992;258:1748–1755. doi: 10.1126/science.1334573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang SA, Crane BR. Effects of interface mutations on association modes and electron-transfer rates between proteins. PNAS. 2005;102:15465–15470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505176102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goodin DB, Mauk AG, Smith M. The peroxide complex of yeast cytochrome c peroxidase contains two distinct radical species, neither of which resides at methionine 172 or tryptophan 51. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:7719–7724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nocek JM, Zhou JS, De Forest S, Priyadarshy S, Beratan DN, Onuchic JN, Hoffman BM. Theory and practice of electron transfer within protein-protein complexes: Application to the multi-domain binding of cytochrome c by cytochrome c peroxidase. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2459–2489. doi: 10.1021/cr9500444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seifert JL, Pfister TD, Nocek JM, Lu Y, Hoffman BM. Hopping in the electron-transfer photocycle of the 1:1 complex of zn-cytochrome c peroxidase with cytochrome c. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5750–5751. doi: 10.1021/ja042459p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hildebrandt P, English AM, Smulevich G. Cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase complex as studied by resonance raman spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1992;31:2384–2392. doi: 10.1021/bi00123a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox T, Hazzard JT, Edwards SL, English AM, Poulos TL, Tollin G. Rate of intramolecular reduction of ferryl iron in compound i of cytochrome c peroxidase. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7426–7428. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kornblatt JA, English AM. The binding of porphyrin cytochrome c to yeast cytochrome c peroxidase. A fluorescence study of the number of sites and their sensitivity to salt. Eur J Biochemistry. 1986;155:505–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman BM, Natan MJ, Nocek JM, Wallin SA. Long-range electron transfer within metal-substituted protein complexes. Structure and Bonding. 1991;75:85–108. Long-Range Electron Transfer Biol. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho PS, Hoffman BM, Kang CH, Margoliash E. Control of the transfer of oxidizing equivalents between heme iron and free radical site in yeast cytochrome c peroxidase. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:4356–4363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erman JE, Vitello LB. Cytochrome c peroxidase: A model heme protein. J Biochem Mol Biol. 1998;31:307–327. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mei H, Wang K, Peffer N, Weatherly G, Cohen DS, Miller M, Pielak G, Durham B, Millett F. Role of configurational gating in intracomplex electron transfer from cytochrome c to the radical cation in cytochrome c peroxidase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6846–6854. doi: 10.1021/bi983002t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wallin SA, Stemp EDA, Everest AM, Nocek JM, Netzel TL, Hoffman BM. Multiphasic intracomplex electron transfer from cytochrome c to zn cytochrome c peroxidase: Conformational control of reactivity. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:1842–1844. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Mauro JM, Edwards SL, Oatley SJ, Fishel LA, Ashford VA, Xuong N-h, Kraut J. X-ray structures of recombinant yeast cytochrome c peroxidase and three heme-cleft mutants prepared by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7160–7173. doi: 10.1021/bi00483a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou JS, Nocek JM, DeVan ML, Hoffman BM. Inhibitor-enhanced electron transfer: Copper cytochrome c as a redox-inert probe of ternary complexes. Science. 1995;269:204–207. doi: 10.1126/science.7618081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.For brevity when discussing the various forms of I, we include additional descriptors. Thus, I2 refers to a binary complex, I3 to a ternary, and the state of the Cc(s) bound is further specified within parentheses. Thus, I2(2+) refers to the binary complex, [ZnP+CcP, Fe2+Cc], while I3(2+/Cu) refers to the ternary complex, [ZnP+CcP, Fe2+Cc, CuCc]

- 21.Zhang Q, Wallin SA, Miller RM, Billstone V, Spears KG, Hoffman BM, McLendon G. Thermodynamic and kinetic aspects of binding and recognition in the cytochrome c cytochrome c peroxidase complex. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:3665–3669. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mei H, Wang K, McKee S, Wang X, Waldner JL, Pielak GJ, Durham B, Millett F. Control of formation and dissociation of the high-affinity complex between cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase by ionic strength and the low-affinity binding site. Biochemistry. 1996;35:15800–15806. doi: 10.1021/bi961487k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bashir Q, Volkov AN, Ullmann GM, Ubbink M. Visualization of the encounter ensemble of the transient electron transfer complex of cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:241–247. doi: 10.1021/ja9064574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Volkov AN, Ubbink M, van Nuland NAJ. Mapping the encounter state of a transient protein complex by pre nmr spectroscopy. Journal of Biomolecular NMR. 2010;48:225–236. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9452-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teske JG, Savenkova MI, Mauro JM, Erman JE, Satterlee JD. Yeast cytochrome c peroxidase expression in escherichia coli and rapid isolation of various highly pure holoenzymes. Protein Expression and Purification. 2000;19:139–147. doi: 10.1006/prep.2000.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pollack WBR, Rosell FI, Twitchett MB, Dumont ME, Mauk AG. Bacterial expression of a mitochondrial cytochrome. cTrimethylation of lys72 in yeast iso-1-cytochrome c and the alkaline conformational transition. Biochemistry. 1998;37:6124–6131. doi: 10.1021/bi972188d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yonetani T. Studies on cytochrome {ic} peroxidase. X. Crystalline apo- and reconsituted holoenzymes. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:5008–5013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Findlay MC, Dickinson LC, Chien JCW. Copper-cytochrome c. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:5168–5173. doi: 10.1021/ja00457a043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The decay with rate constant k2 represents both electron (kf) and energy transfer. We roughly estimate that the quenching is up to 85% energy transfer based on empirical absorbance measurements.

- 30.Ho PS, Sutoris C, Liang N, Margoliash E, Hoffman BM. Species specificity of long-range electron transfer within the complex between zinc-substituted cytochrome c peroxidase and cytochrome c. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:1070–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 31.From empirical analysis of previous data (not shown) we roughly estimate the maximum concentration of ZnP+CcP to be ~0.2μM when [Fe3+Cc]0=[ZnPCcP]0 = 5μM

- 32.Northrup SH, Reynolds JCL, Miller CM, Forrest KJ, Boles JO. Diffusion-controlled association rate of cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase in a simple electrostatic model. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:8162–8170. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mauk MR, Ferrer JC, Mauk AG. Proton linkage in formation of the cytochrome c-cytochrome c peroxidase complex: Electrostatic properties of the high- and low-affinity cytochrome binding sites on the peroxidase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:12609–12614. doi: 10.1021/bi00208a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.With progressive additions of [Fe2+Cc], the slowly decaying phase of the intermediate progress curve becomes pseudo-first order, as expected when [Fe2+Cc] ≫ [ZnP+CcP], and it can be fit with an analytical function with an exponential rise and fall. However, to maintain comparisons with the analysis of the other titrations, we have chosen to continue to use Scheme 1.

- 35.Increasing accumulation of I2(3+) with added Fe3+Cc, which is unavailable for CR, is expected to cause a decrease in appkon(2+) as observed.

- 36.Since the concentration of the ternary I3(2+/3+) is roughly an order of magnitude lower than that of the binary, and it is shown above that CR in the ternary is slower than in the binary, terkb < kb, we may ignore CR within the ternary to obtain a semi-quantitative analysis of appkoff(2+).

- 37.Moench SJ, Chroni S, Lou B, Erman JE, Satterlee JD. Proton nmr comparison of noncovalent and covalently cross-linked complexes of cytochrome c peroxidase with horse, tuna, and yeast ferricytochromes c. Biochemistry. 1992;31:3661–3670. doi: 10.1021/bi00129a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller MA, Geren L, Han GW, Saunders A, Beasley J, Pielak GJ, Durham B, Millett F, Kraut J. Identifying the physiological electron transfer site of cytochrome c peroxidase by structure-based engineering. Biochemistry. 1996;35:667–673. doi: 10.1021/bi952557a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nocek JM, Leesch VW, Zhou JS, Jiang M, Hoffman BM. Multi-domain binding of cytochrome c peroxidase by cytochrome c: Thermodynamic vs. Microscopic binding constants. Israel Journal of Chemistry. 2000;40:35–46. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wyman J. Regulation in macromolecules as illustrated by haemoglobin. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics I. 1968:35–80. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Northrup SH, Thomasson KA. Electrostatic calculations of 2:1 complexes of cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase. The FASEB Journal. 1992;6:A474. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakani S, Vitello LB, Erman JE. Characterization of four covalently-linked yeast cytochrome c/cytochrome c peroxidase complexes: Evidence for electrostatic interaction between bound cytochrome c molecules. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14371–14378. doi: 10.1021/bi061662p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stemp EDA, Hoffman BM. Cytochrome c peroxidase binds two molecules of cytochrome c: Evidence for a low-affinity, electron-transfer-active site on cytochrome c peroxidase. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10848–10865. doi: 10.1021/bi00091a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou JS, Hoffman BM. Stern-volmer in reverse: 2:1 stoichiometry of the cytochrome c cytochrome c peroxidase electron-transfer complex. Science. 1994;265:1693–1696. doi: 10.1126/science.8085152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leesch VW, Bujons J, Mauk AG, Hoffman BM. Cytochrome c peroxidase:Cytochrome c complex: Locating the second binding domain on cytochrome c peroxidase with site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10132–10139. doi: 10.1021/bi000760m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Northrup SH, Boles JO, Reynolds JCL. Brownian dynamics of cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase association. Science. 1988;241:67–70. doi: 10.1126/science.2838904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang CH, Ferguson-Miller S, Margoliash E. Steady state kinetics and binding of eukaryotic cytochromes c with yeast cytochrome c peroxidase. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:919–926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mei H, Geren L, Miller MA, Durham B, Millett F. Role of the low-affinity binding site in electron transfer from cytochrome c to cytochrome c peroxidase. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3968–3976. doi: 10.1021/bi016020a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo M, Bhaskar B, Li H, Barrows TP, Poulos TL. Crystal structure and characterization of a cytochrome c peroxidase-cytochrome c site-specific cross-link. PNAS. 2004;101:5940–5945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306708101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Volkov AN, Worrall Jonathan AR, Holtzmann E, Ubbink M. From the cover: Solution structure and dynamics of the complex between cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase determined by paramagnetic nmr. PNAS. 2006;103:18945–18950. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603551103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bashir Q, Volkov AN, Ullmann GM, Ubbink M. Visualization of the encounter ensemble of the transient electron transfer complex of cytochrome c and cytochrome c peroxidase. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;132:241–247. doi: 10.1021/ja9064574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McLendon G. Control of biological electron transport via molecular recognition and binding: The “velcro” model. Structure and Bonding. 1991;75:159–174. [Google Scholar]

- 53.A more restrictive limit on terkb could not be established, give the available range of [Fe3+Cc].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.