Abstract

Hypertension awareness, treatment and control are lower among uninsured than insured adults. Time trends in differences and underlying modifiable factors are important for informing strategies to improve health equity. National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1988–1994, 1999–2004, 2005–2010 data in adults 18–64 years were analyzed to explore this opportunity. The proportion of adults with hypertension who were uninsured increased from 12.3% in 1988–1994 to 17.4% in 2005–2010. In 1988–1994, hypertension awareness, treatment and control to <140/<90 millimeters mercury (30.1% versus 26.5, p=0.27) were similar in insured and uninsured adults. By 2005–2010, the absolute gap in hypertension control between uninsured and insured adults of 21.9% (52.5% versus 30.6%, p<0.001]) was explained approximately equally by lower awareness (65.2% versus 80.7%), fewer aware adults treated (75.2% versus 88.5%,and fewer treated adults controlled (63.1% versus 73.5% [all p<0.001]). Publicly insured and uninsured adults had similar income. Yet, hypertension control was similar across time periods in publicly and privately insured adults, despite lower income and education in the former. In multivariable analysis, hypertension control in 2005–2010 was associated with visit frequency (odds ratio 3.4, 95% confidence interval [2.4–4.8]), statin therapy (1.8 [1.4–2.3]) and healthcare insurance (1.6 [1.2–2.2]) but not poverty index (1.04 [0.96–1.12]). Public or private insurance linked to more frequent healthcare, greater awareness and effective treatment of hypertension, and appropriate statin use could reverse a long-term trend of growing inequity in hypertension control between insured and uninsured adults.

Keywords: Hypertension, Healthy People 2020, health insurance, uninsured, health disparities

Introduction

Hypertension impacts approximately 30% of U.S. adults and is a major risk factor for coronary heart disease, stroke, and heart failure.1 Hypertension treatment and control reduce clinical complications.2 Given its prevalence and health impact, hypertension is a major public health topic included in Healthy People and Million Hearts goals.3,4

Uninsured adults are less likely to be aware of and treated for hypertension than insured adults, less likely to be controlled when treated, and more likely to experience clinical complications.5-11 In 2005–2008, hypertension control among adults 20–64 years old was 28.7% in the uninsured, 53.4% in publicly insured and 48.2% in privately insured groups.10 Differences in control were partially explained by more undiagnosed hypertension in the uninsured group.10

While the extant literature provides substantial information, addressing several knowledge gaps could better inform strategies to improve hypertension control in uninsured adults. For example, time trends are important as a widening gap in hypertension control between uninsured and insured adults would suggest greater need for change than a declining gap. Similarly, if the proportion of adults with hypertension who are uninsured is growing, then more resources are required than if the proportion is declining or unchanged. The uninsured adult population was growing prior to the 2008 financial crisis and increased subsequently.12,13 Even with healthcare reform, the number of uninsured in the U.S. is projected at 31 million.14

Previous studies did not quantify the contribution of lower awareness (undiagnosed hypertension) or differences in the proportion of aware patients treated or treated patients controlled to lower hypertension control in uninsured than insured adults. If lower hypertension awareness in the uninsured is the main contributor,10 then strategies for addressing the gap are simpler than iflower proportions of aware patients treated and treated patients controlled are also contributing importantly.5–9 And, if hypertension control is higher in adults with public than private insurance,10 and not explained by other differences between the two groups, then public insurance could be a better option for improving hypertension control in uninsured adults.

To address the knowledge gaps, analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey(s) (NHANES) data for 1988–1994 and 1999–2010 was conducted in adults 18–64 years old with hypertension. Findings were compared in adults with and without healthcare insurance and with public or private healthcare insurance. The analyses also sought to identify modifiable factors that could improve equity in control between insured and uninsured adults.

Methods

NHANES assess a representative sample of the U.S. civilian population. All adults provided written consent approved by the National Center for Health Statistics.

Participants included adults 18–64 years old in NHANES 1988–1994, 1999–2004, and 2005–2010. Race/Ethnicity was determined by self-report and separated into non-Hispanic white (white) and non-Hispanic black (black) race, Hispanic ethnicity, and other.

Insurance during the past 12 months is defined by positive answer to “Are you covered by health insurance or some other kind of healthcare plan?” Private Insurance was defined by positive response to “Are you covered by private insurance?” and/ or “Are you covered by Medi-Gap?” Medicaid Insurance was defined by positive response to “Are you covered by Medicaid” and/or “Are you covered by State Children's Health Insurance program (SCHIP)?” Medicare Insurance was defined by response to “Are you covered by Medicare?” Other government insurance was defined by response to one or more questions, “Are you covered by CHAMPUS/VA/military health care?”, “Are you covered by Indian Health Service?”, “Are you covered by state-sponsored health plan?”, “Are you covered by other government insurance?”

Public Insurance includes Medicaid, Medicare and other government.

Poverty index was calculated by dividing family income by the poverty guidelines according to family size, appropriate year and state.15 Educational status was determined by the highest grade or level of school completed or highest degree received.

Prescription Medications

NHANES participants were asked if they had taken prescription medications in the past 30 days. Those answering “yes” were asked to show containers for all medications taken during that time, and medication names were recorded. If no container was available, participants were asked to verbally report medication name.

Blood pressure (BP) was measured and reported per NHANES guidelines.5,16

Prevalent hypertension was defined by: (a) systolic BP ≥140 and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg and/or (b) positive response to “Are you currently taking prescribed medication to lower your BP?” Awareness, treatment, proportion of treated hypertension controlled and hypertension control(<140/<90 for all adults) were defined previously.2,5,16

Diabetes, including diagnosed and undiagnosed, and statin medication use weredefined.16,17 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/1.73 m2/min and/or urine albumin:creatinine ≥300 mg/g, i.e.,18 values used to define a lower BP target, rather than ≥30mg/g.19 Serum creatinine was adjusted across surveys.20 Cardiovascular disease including (a) coronary heart disease121 (b) stroke22 (c) congestive heart failure22 were defined. Medical visit frequency and cigarette smoker status were described.16

Data analysis

SAS v9.4 (Cary, NC) survey procedures were used to account for NHANES complex sampling design. NHANES data were analyzed and reported using recommended guidelines.23–25 Data for hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment and control were age-adjusted to the U.S. 2010 census.26 Among adults 18–64 years old in 2010, the proportion who were 18 to 44 was 0.58 and 45 to 64 years was 0.42. For age-adjusting hypertension awareness, treatment, and control across time, additional weights were calculated since prevalent hypertension varies by age. The proportion of adults in each age group that were hypertensive was multiplied by their respective year 2010 weight for all adults. Weights were calculated by dividing the product for each age group by the sum of products for both groups in each survey.15 PROC SURVEYMEANS was used to generate means and confidence intervals. PROC SURVEYFREQ was used to estimate proportions and confidence intervals. PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC was used to assess association between clinical variables and BP control. In each of these procedures, the appropriate weight was used in the analysis. Taylor Series Linearization was used for variance estimation and domain analysis for subpopulations of interest. For within survey between group (uninsured vs. insured, private vs. public insured) comparisons at each of three NHANES time periods, Rao-Scott Chi-Square Tests were used to assess differences in distributions of categorical variables and Wald F-tests for differences in continuous variables. To assess the contribution of lower awareness, treated/aware, and control/treated to lower BP control in uninsured adults, hypertension control was re-calculated for uninsured adults with these three variables adjusted individually and sequentially to values in insured adults. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant except within group comparisons across three time period wherein p-values <0.017 (.05/3 [Bonferroni correction]) were accepted as significant.

Results

The process for deriving the 18–64 years old population with hypertension is depicted in Supplemental Figure S1; 1,563 adults were without and 6,067 (4,390 private, 1,377 public, 300 insurance unspecified or both public and private) adults had healthcare insurance.

Uninsured and insured adults (Table 1)

Table 1.

Adults with hypertension grouped by uninsured versus insured status in 3 NHANES time periods.

| NHANES | 1988 – 1994 | 1999 – 2004 | 2005 – 2010 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | Uninsured | Insured | Uninsured | Insured | Uninsured | Insured |

| Sample, N | 408 | 1962 | 463 | 1828 | 692 | 2277 |

| Pop., N | 2,821,809 | 20,171,596 | 5,145,276 | 28,743,951 | 6,697,422 | 31,785,809 |

| Group % | 12.39.7-14.8 | 87.785.2-90.3 | 15.213.1-17.3 | 84.882.7-86.9 | †17.4 15.4-19.4 | †82.6 80.6-84.6 |

| Age, years | 44.4‡ 42.7-46.1 | 48.948.2-49.6 | †45.1‡43.9-46.3 | 49.648.9-50.3 | †48.0‡ 46.7-49.2 | †50.6 49.9-51.2 |

| Sex Male, % | 47.8* 41.1-54.6 | 55.352.1-58.5 | 56.251.3-61.1 | 51.849.0-54.6 | 56.251.7-60.8 | 52.149.6-54.6 |

| Race | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | |||

| White, % | 54.842.6-67.0 | 75.172.3-78.0 | 51.939.8-63.9 | 71.667.6-75.5 | 51.744.1-59.3 | 71.566.9-76.2 |

| Black, % | 21.115.9-26.3 | 17.115.0-19.2 | 20.113.6-26.6 | 15.312.0-18.6 | 22.016.7-27.4 | 16.212.8-19.6 |

| Hispanic, % | *10.6 7.7-13.5 | ‡3.3 2.6-3.9 | 21.213.4-29.0 | 8.25.7-10.7 | *21.4 15.0-27.9 | ‡6.7 5.0-8.4 |

| Other, % | 13.5 4.6-22.4 | 4.53.0-6.0 | 6.8 2.6-11.1 | 4.93.3-6.5 | 4.8 2.2-7.4 | 5.54.0-7.0 |

| HC visits/yr | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | |||

| 0-1 | 52.545.5-59.5 | ‡33.1 30.1-36.1 | 47.140.9-53.2 | 22.920.5-25.2 | 45.640.4-50.9 | ‡20.3 17.9-22.7 |

| ≥2 | 47.540.5-54.5 | ‡66.9 63.9-69.9 | 52.946.8-59.1 | 77.174.8-79.5 | 54.449.1-59.6 | ‡79.7 77.3-82.1 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.729.1-32.2 | 30.329.7-30.9 | 31.030.0-31.9 | *31.1 30.6-31.6 | 31.0* 30.2-31.7 | ‡32.0 31.6-32.4 |

| ≥30 | 44.736.4-52.9 | 44.740.3-49.0 | 44.338.5-50.1 | 51.048.2-53.9 | 48.844.3-53.3 | ‡55.2 52.4-58.0 |

| SBP, mmHg | 138.9135.9-141.9 | 138.1136.8-139.5 | 142.0‡139.4-144.6 | ‡136.2135.1-137.2 | 140.3‡138.1-142.4 | ‡132.0131.2-132.8 |

| DBP, mmHg | 85.083.0-86.9 | ‡84.8 83.9-85.7 | 83.6*81.7-85.5 | ‡81.280.4-82.0 | *81.9‡80.5-83.3 | ‡77.476.5-78.3 |

| Statin, % | 6.81.8-11.8 | ‡2.41.5-3.3 | 8.0†3.2-12.8 | ‡17.815.2-20.3 | *12.8‡10.4-15.3 | ‡27.9 25.7-30.1 |

| Diabetes, %, | 14.1 7.7-20.5 | 9.8 8.4-11.3 | 13.4 9.6-17.1 | ‡12.0 10.5-13.5 | 15.7 12.0-19.4 | ‡17.0 15.1-19.0 |

| CVD, % | 13.6 9.7-17.6 | 11.7 9.6-13.8 | 12.9 8.1-17.7 | 13.0 10.7-15.4 | 12.5 9.0-15.9 | 13.9 12.0-15.8 |

| CKD, % | 5.4 1.6-9.2 | 5.6 4.1-7.1 | 7.9 4.6-11.3 | 6.2 5.2-7.2 | 8.7 5.9-11.6 | 7.3 5.6-9.0 |

| Smoking, % | 36.4‡ 29.2-43.6 | 23.9 21.1-26.6 | 35.5‡ 30.0-41.0 | 21.4 19.0-23.7 | 38.4‡ 31.4-45.3 | 20.5 18.2-22.7 |

| Poverty index | 1.6‡ 1.3-1.8 | 3.2 3.0-3.3 | 1.8‡ 1.7-2.0 | 3.4 3.3-3.5 | 1.9‡ 1.7-2.1 | **3.4 3.3-3.6 |

| Poverty index | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | |||

| Below 100% | †41.8 31.2-52.4 | 9.7 7.4-12.1 | 25.8 21.3-30.4 | 9.9 8.2-11.7 | *27.6 22.9-32.3 | 9.1 7.7-10.5 |

| 100%-<200% | 33.6 23.9-43.3 | 14.8 12.7-16.9 | 42.7 36.3-49.0 | 14.6 12.0-17.3 | 36.8 31.7-42.0 | 14.5 12.2-16.9 |

| 200% or more | 24.6 16.2-33.0 | 75.5 72.0-79.0 | 31.5 25.4-37.7 | 75.5 72.4-78.5 | 35.6 28.7-42.5 | 76.4 73.5-79.3 |

| Education | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | |||

| ≥Some college,% | 24.0 16.4-31.5 | ‡37.7 34.2-41.2 | 34.6 28.7-40.5 | *53.4 50.1-56.8 | 32.4 27.1-37.7 | ‡59.6 56.0-63.2 |

| High School, % | 35.2 26.3-44.2 | ‡38.7 35.1-42.3 | 27.7 20.9-34.6 | 27.5 25.0-30.1 | 32.8 28.5-37.1 | ‡24.6 21.6-27.7 |

| <High School, % | 40.8 31.3-50.3 | *23.6 20.5-26.7 | 37.6 30.8-44.5 | 19.1 17.5-20.6 | 34.8 30.0-39.6 | ‡15.7 13.3-18.2 |

Data = mean, 95% confidence intervals. Data in italics indicate relative standard errors >30% which exceed NHANES reporting guideline limits and are provided for information only; N=number; HC = healthcare; S = systolic; D = diastolic; BP = blood pressure. CVD=cardiovascular disease; CKD=chronic kidney disease.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

Poverty index reflects family income divided by the federal poverty level (100%), i.e., higher values reflect greater income. Symbols to the right of the number represent comparisons between groups within NHANES time period. Symbols to the left represent comparisons within group between NHANES time periods. Symbols in column 1 compare to column 2, column 2 with column 3 and column 3 with column 1. Symbols above the number indicate differences in distribution of values within time period for race and healthcare visits/year, poverty index and education.

In adults 18–64 years old with hypertension, the estimated number and percentage in the U.S. population of uninsured grew from 2.82 million (12.3%) in 1988–1994 to 6.70 million (17.4%) in 2005–2010. The insured population grew numerically but decreased as a percentage of all hypertensive adults from 20.2 (87.7%) to 31.8 million (82.6%). In 1988–1994, uninsured adults were ∼4.5 years younger than insured adults and more likely to be women. In 2005–2010, the age difference declined to 2.6 years and percentages of uninsured men increased. Across time, uninsured adults were less likely to be white, although the majority was white. The percentage of uninsured Hispanic adults doubled between 1988–1994 and 2005–2010. Uninsured adults were more likely to have 0–1 and less likely to have ≥2 health care visits/year than insured adults.

BP was similar in uninsured and insured adults in 1988–1994, but higher in uninsured adults in 1999–2010. Statin use increased with time in insured and uninsured adults and was lower in 1999–2010 in the uninsured. Across time, prevalent CVD and CKD were not different between uninsured and insured adults. The uninsured were more likely to smoke cigarettes.

Mean family incomes were more than three times the federal poverty level among insured adults but less than twice the federal poverty level in uninsured adults. In general, <10% of insured adults had family incomes below the federal poverty level vs. ≥25% of uninsured adults. Conversely, ≥75% of insured adults had family incomes of ≥200% of the federal poverty level vs. <40% of uninsured. Educational attainment was higher in the insured than uninsured.

Hypertensive adults with private vs. public health insurance (Table 2)

Table 2. Insured hypertensive adults subdivided by private versus public insurance in 3 NHANES time periods.

| 1988 – 1994 | 1999 – 2004 | 2005 – 2010 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Variable | Private | Public | Private | Public | Private | Public |

| Sample, N | 1496 | 340 | 1382 | 361 | 1512 | 676 |

| Pop., N | 17,040,331 | 2,195,746 | 23,244,360 | 4,342,700 | 24,494,750 | 6,381,747 |

| Group, % | 88.6 85.8-91.4 | 11.4 8.6-14.2 | 84.3 81.8-86.7 | 15.7 13.3-18.2 | †79.3 77.0-81.7 | †20.7 18.3-23.0 |

| Age, year | 48.6 47.9-49.3 | 48.9 46.5-51.2 | 49.2* 48.4-50.0 | 50.7 49.2-52.3 | †50.3 49.6-50.9 | 50.9 49.7-52.1 |

| Sex, Male, % | *57.4‡ 54.3-60.4 | 40.1 33.1-47.0 | 51.9 48.6-55.1 | 49.9 44.1-55.7 | 53.3 50.6-55.9 | 48.6 42.9-54.2 |

| Race, W:B:H:O | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | |||

| White, % | 79.1 76.4-81.8 | 48.8 39.0-58.6 | 74.2 70.4-78.0 | 57.6 49.5-65.8 | 76.2 72.0-80.4 | 54.3 46.6-62.1 |

| Black, % | 14.2 12.2-16.2 | †34.9 27.0-42.7 | 14.0 10.8-17.2 | 20.9 15.4-26.5 | 12.9 10.0-15.8 | 27.4 21.1-33.7 |

| Hispanic, % | †2.9 2.3-3.6 | *6.1 3.7-8.5 | 7.4 5.2-9.5 | 14.3 7.7-20.9 | †5.8 4.3-7.2 | 10.6 7.0-14.2 |

| Other, % | 3.8 2.3-5.3 | 10.2 2.7-17.8 | 4.5 2.9-6.0 | 7.2 2.4-12.0 | 5.1 3.4-6.8 | 7.6 4.7-10.6 |

| HC visits/yr | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | |||

| 0-1 | ‡35.5 31.9-39.1 | *17.6 11.6-23.6 | 25.7 22.7-28.6 | 7.9 4.5-11.2 | †23.3 20.3-26.3 | 10.6 7.1-14.0 |

| ≥2 | ‡64.5 60.9-68.1 | *82.4 76.4-88.4 | 74.3 71.4-77.3 | 92.1 88.8-95.5 | ‡76.7 73.7-79.7 | 89.4 86.0-92.9 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 30.2 29.6-30.8 | 31.1 29.3-32.9 | 31.0 30.5-31.5 | 32.2 31.0-33.4 | ‡31.6‡ 31.2-32.0 | *33.4 32.4-34.3 |

| ≥30 | *43.8 39.2-48.5 | 50.5 39.3-61.8 | 50.1 46.6-53.5 | 56.5 48.6-64.4 | †52.9† 49.4-56.3 | *62.4 56.9-68.0 |

| SBP, mmHg | 137.8* 136.4-139.3 | 140.4 138.2-142.7 | ‡136.0 135.0-137.1 | ‡136.7 133.8-139.6 | ‡132.0 131.0-133.0 | ‡1311 129.7-132.5 |

| DBP, mmHg | ‡85.1 84.1-86.0 | †84.1 82.2-85.9 | ‡81.6 80.7-82.5 | *79.3 77.3-81.4 | ‡77.8 76.7-78.8 | ‡76.3 75.0-77.6 |

| Statin, % | ‡2.1 1.0-3.1 | 5.4 0-13.4 | ‡16.9* 14.1-19.7 | 22.8 18.0-27.6 | ‡26.6 23.7-29.5 | ‡32.0 26.9-37.0 |

| Diabetes, %, | 8.1‡ 6.4-9.7 | 17.2 11.9-22.6 | †9.8‡ 8.2-11.4 | 20.1 15.6-24.6 | ‡14.4‡ 12.3-16.5 | 24.1 20.5-27.6 |

| CVD, % | 9.2‡ 6.7-11.6 | 25.9 18.2-33.5 | 10.4‡ 8.1-12.7 | 26.8 20.8-32.8 | 9.7‡ 7.9-11.4 | 28.3 23.4-33.2 |

| CKD, % | 4.5‡ 2.9-6.0 | 12.8 7.2-18.4 | 5.0‡ 4.0-6.1 | 11.5 7.5-15.5 | 5.6‡ 3.9-7.3 | 12.9 9.7-16.2 |

| Smoking, % | 22.3‡ 19.1-25.4 | 36.2 29.6-42.8 | 17.9‡ 15.1-20.6 | 36.7 29.9-43.5 | *17.3‡ 14.8-19.7 | 33.0 27.9-38.1 |

| Poverty Index | †3.4‡ 3.3-3.6 | 1.3 1.0-1.6 | 3.7‡ 3.6-3.8 | 1.6 1.4-1.9 | ‡3.8‡ 3.7-3.9 | ‡2.1 1.8-2.3 |

| Poverty index | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | |||

| Below 100% | 3.5 1.9-5.1 | *56.6 45.8-67.4 | ‡4.6 3.6-5.6 | 40.2 31.9-48.5 | 2.4 1.8-3.1 | ‡34.8 29.6-40.0 |

| 100%-<200% | 12.9 10.6-15.2 | 26.4 19.0-33.7 | 10.7 8.5-12.9 | 34.0 25.4-42.6 | 10.7 8.3-13.1 | 28.8 24.1-33.5 |

| 200% or more | 83.6 80.5-86.6 | 17.0 8.7-25.3 | 84.7 82.2-87.2 | 25.9 17.8-34.0 | 86.9 84.4-89.4 | †36.4 29.8-43.0 |

| Education | ‡ | ‡ | ‡ | |||

| ≥Some college,% | ‡41.7 37.9-45.4 | †12.4 5.8-19.0 | 58.3 54.9-61.8 | ‡28.3 22.3-34.4 | ‡62.8 58.7-66.9 | ‡49.2 42.9-55.6 |

| High school, % | ‡39.7 36.0-43.4 | 28.3 21.2-35.4 | 27.2 24.3-30.2 | 29.7 23.9-35.5 | ‡25.3 21.8-28.7 | 21.6 17.5-25.7 |

| <High school, % | 18.6 15.0-22.3 | *59.3 49.1-69.5 | 14.4 12.8-16.1 | *42.0 35.1-48.9 | †11.9 9.8-14.1 | ‡29.2 22.5-35.8 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

Abbreviations, symbols and significance are the same as Table 1.

Means and 95% confidence intervals in italics exceed the variance allowed in NHANES reporting guidelines, i.e., relative standard errors >30%; data provided as information only

Among insured adults, the group with public insurance grew numerically and proportionately from 2.2 (11.4%) million in 1988–1994 to 6.4 million (20.7%) in 2005–2010, while the privately insured rose numerically but declined proportionately from 17.0 (88.6%) to 24.5 million (79.3%). Adults with unspecified insurance type or both public and private insurance were not counted as publicly or privately insured. The estimated number of U.S. adults 18–64 years with private or public insurance is ∼900,000 less than the total insured number. Age was similar in both groups. Privately insured adults were generally more likely to be male, white and have 0–1 healthcare visits/year than publicly insured adults. Self-reported statin use was comparable in publicly and privately insured adults and increased over time in both groups. Diagnosed diabetes, CKD and cigarette smoking were greater in the publicly than privately insured.

Mean family incomes were higher among privately insured, with a mean of 3.4–3.8 times the federal poverty level over the three NHANES time periods, than publicly insured adults, with a mean of 1.3–2.1 times the federal poverty level. Consistent with the differences in family incomes, privately insured adults were less likely to have family incomes below or between 100–199% of the federal poverty level and more likely to have incomes ≥200% of the federal poverty level. Educational attainment was also greater in privately than publicly insured adults. Income and educational were not different in uninsured and privately insured adults (widely overlapping 95% confidence intervals), except higher education among publicly insured in 2005–2010.

Clinical epidemiology of hypertension in uninsured and insured adults

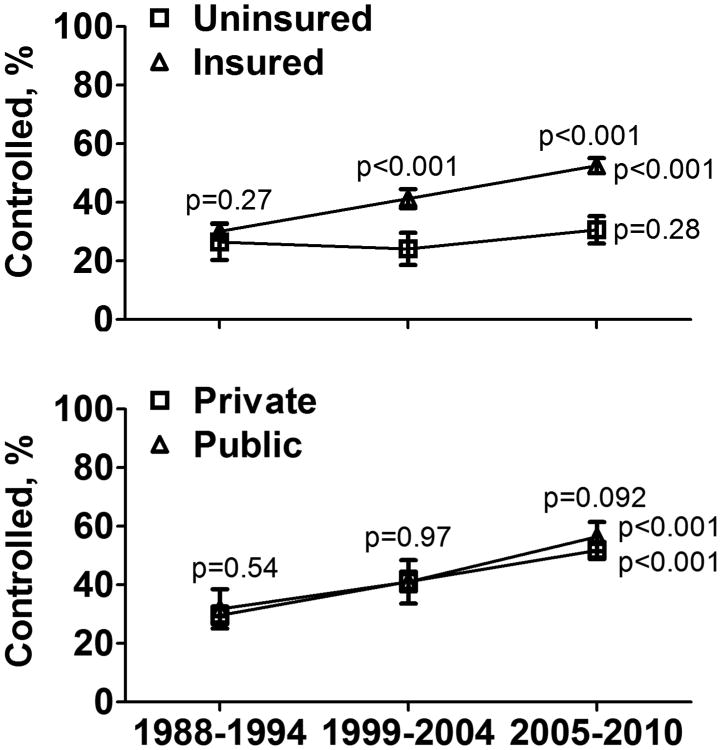

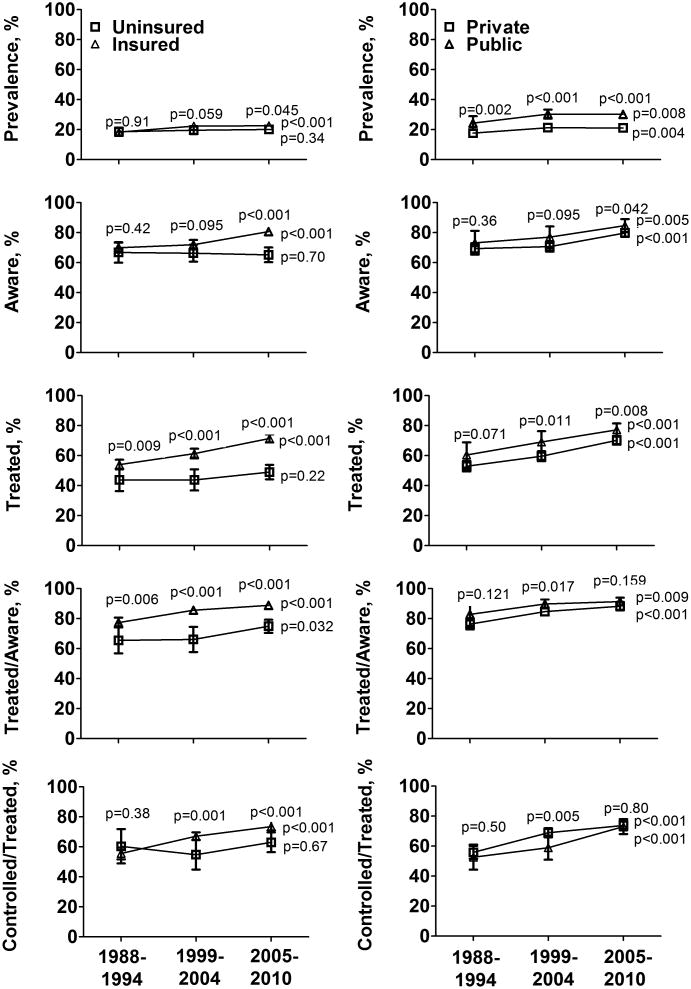

Hypertension control was similar in insured and uninsured adults in 1988–1994 (Figure 1). Hypertension control improved over time in insured but not uninsured adults and was higher among insured in 1999–2004 and 2005–2010.Prevalent hypertension and awareness were higher among insured than uninsured in 2005–2010 (Figure 2). Percentages of aware patients treated were higher in insured than uninsured in all time periods. Percentages of treated adults controlled were greater among insured than uninsured in 1999–2004 and 2005–2010. Hypertension awareness, treatment and proportion of treated patients controlled improved over time among insured but not uninsured adults. The percentage of aware patients treated rose over time in both groups. In treated adults, the number and classes of BP medications reportedly taken in the prior 30 days were not different in insured than uninsured (S1 Table).

Figure 1.

Hypertension control is shown for the three NHANES time periods in uninsured and insured patients (left) and for publicly and privately insured patients (right).P-values over time periods compare the two groups during that time interval. P-values to the right of 2005–2010, indicate a significant change for the group designated over the 3 NHANES time periods.

Figure 2.

The prevalence of hypertension and the percentages of patients with hypertension that are aware, treated, aware adults treated, and treated adults controlled are shown. On the left hand side, comparative data are provided for uninsured and insured patients. On the right hand side, comparative data are provided for patients with private or public insurance. P-values over time periods indicate differences between the two groups during that time interval. P-values to the right of the group symbol for 2005–2010, indicate a significant change for the group designated over the 3 NHANES time periods.

Clinical epidemiology of hypertension in publicly and privately insured adults

Hypertension control improved over time in adults with public and private insurance but was not different between groups (Figure 1). Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, aware adults treated and treated adults controlled increased with time in the publicly and privately insured (Figure 2). Prevalent hypertension was greater in publicly insured adults across time. Hypertension awareness was greater in publicly than privately insured in 2005–2010. The percentage of aware adults treated for hypertension was greater in publicly insured adults in 1999–2004, whereas the reverse was true for percentages of treated adults controlled.

The contribution of three factors individually and cumulatively to lower BP control in the uninsured in 2005–2010 is provided in S2 Table. If hypertension awareness in uninsured equaled insured adults, then BP control in the uninsured would have been 38.3% rather than 30.6%. The 21.9% absolute gap (30.6% vs. 52.5%) would have been 14.1%, a 34.9% reduction. Raising percentages of aware adults treated or treated adults controlled to values in the insured, increased BP control from 30.6% to 36.4% and 36.0%, or 26.5% and 24.7% of the control gap, respectively. When the three variables were raised sequentially, the hypertension control gap between insured and insured closed, and each variable had a nearly equal contribution to the gap.

Clinical variables associated with hypertension control in multivariable regression analysis among adults 18–64 years old are depicted in S3 Figure. Hypertension control improved with advancing age, increasing BMI, diabetes mellitus, and clinical cardiovascular disease but was lower in adults who were male, black, and Hispanic. Hypertension control was higher in adults with ≥2 than those with 0–1 healthcare visits/year and those taking statins and with health insurance than those without. Only in 2005–2010, adults with at least some college education had higher BP control rates than adults with less than high school education.

Discussion

Hypertension control is lower and cardiovascular outcomes less favorable in uninsured than insured U.S. adults.5–10 Our NHANES study was designed to address several gaps in the literature, which could better inform strategies to improve hypertension control and outcomes for this population. Prior studies reported lower hypertension control in uninsured than insured adults during limited but not longer time periods. Constructing a longitudinal perspective from extant literature is confounded by differing definitions of hypertension and variable approaches to age adjustment. In our study, hypertension was consistently defined as BP ≥140/≥90 and/or on treatment. All survey periods were adjusted to the U.S. 2010 census. Hypertension control was not different between uninsured and insured adults in 1988–1994. A significant gap in hypertension control, with lower rates in uninsured than insured was present in 1999–2010.

Prior studies did not address changes in the proportion of adults with hypertension who were uninsured. In this report, the percentage of uninsured adults with hypertension grew from 12.3%, or roughly one in eight, in 1988–1994, to 17.4%, or approximately one in six, in 2005–2010 (Table 1). Our first two findings indicate that the gap in hypertension control between the uninsured and insured grew as the proportion of adults with hypertension who were uninsured increased. These observations suggest that previous strategies to improve healthcare and outcomes for uninsured adults, e.g., federally qualified and rural health centers,27,28 while important have not been sufficient to improve equity in hypertension control.

Previous studies did not quantify the impact of differences in percentages of awareness, aware adults treated, or treated adults controlled to the gap in hypertension control between insured and uninsured adults. When these three variables were raised individually in uninsured to levels in insured adults, BP control rose but remained <40% in the uninsured. Strategies to improve equity in hypertension control require attention to all three variables (S2 Table).

The proportion of treated adults controlled was reportedly lower in uninsured than insured adults6 and confirmed in our report. Persistence on antihypertensive medication is reportedly lower in uninsured than insured adults,29 which could account for this observation (Figure 2).6 Yet, in insured and uninsured adults on treatment, the number and classes of antihypertensive medications reportedly taken in the prior month were not different (S1 Table). NHANES does not assess pill splitting or missed doses, which may be greater among uninsured.

Modifiable and non-modifiable variables related to hypertension control were also examined (S3 Figure). Among fixed variables, increasing age, diabetes and clinical cardiovascular disease were associated with better hypertension control, whereas male sex, black race and Hispanic ethnicity were associated with lower control. While increasing age across the adult lifespan is associated with a decline in hypertension control, hypertension control increases with age up to 60 years but then declines with advancing age ≥60 years.30 Thus, the positive associated between age and BP control in adults 18–64 years of age is not unexpected.

Hypertension control improved modestly but significantly with increasing BMI, although obesity is associated with treatment resistant hypertension.31,32 Our finding is consonant with a previous NHANES report that hypertension control improved more over time in obese than non-obese individuals.33 Hypertension control was also higher in patients with than without diabetes, although diabetes is associated with treatment resistant hypertension.31,32 From 1997 through 2013,18,34 the systolic goal for patients with diabetes was <130 mmHg, which likely improved control to <140 mmHg. NHANES data (S3 Figure) are consistent with the conclusion that clinicians treat hypertension more aggressively when cardiovascular risk is higher.30,32

Infrequent healthcare was linked to lower hypertension control and awareness. The uninsured use less healthcare than insured, differences transcending income,35 and in frequent health care is a significant barrier to better hypertension control.6,30,36,37

In multivariable analysis, insured adults 18–64 years old were more likely to attain hypertension control than uninsured in 1999–2010. As one potentially modifiable factor, uninsured adults were less likely to report taking statins in 1999–2010, when their hypertension control remained flat and fell behind insured adults. Statins were positively related to hypertension control in adults 18–64 years. In a meta-analysis of 40 randomized, placebo-controlled trials, systolic BP was 2.6 mmHg lower in adults randomized to statins than placebo.38 In ASCOT,39 hypertensive patients randomized to atorvastatin were less likely to have treatment resistant hypertension than patients on placebo. The observations are insufficient to support statin prescriptions for BP control. Yet, current cholesterol guidelines, which increase the number of hypertensive adults eligible for statins by about 8 million,40 could potentially improve BP control and reduce the control gap if applied equally to the uninsured and insured.

Another objective was to assess hypertension control in publicly and privately insured adults as this might influence recommendations for insurance plans to improve health in the uninsured.10,41,42 Hypertension control was similar in adults with public and private insurance, although publicly insured adults were more likely to be black or Hispanic, factors negatively associated with hypertension control.3,16,29 Publicly insured adults had more obesity and diabetes than privately insured adults, two factors associated with BP control. Two factors restraining hypertension control in privately insured adults were the higher proportion of males and less frequent healthcare, which are linked to poorer hypertension control among adults 18–64 years. Men, even with healthcare insurance, are less likely than women to use healthcare services.43

Adults with public insurance had lower incomes and educational attainment than those with private insurance. Poverty index was similar in uninsured and publicly insured adults across time. Yet, hypertension control improved in publicly insured but not uninsured adults, which is consistent with the finding that the poverty index was not associated with BP control. Educational attainment was also greater in privately than publically insured patients across time. At least some college education was associated with better hypertension control than less than a high school education only in 2005–2010, which coincided with the only time period that publically insured adults were more likely to have some college education than uninsured adults.

Study limitations include the NHANES design with repeated, representative cross-sectional samples of a very small percentage of the U.S. population. Confidence intervals are often large, which may mask real differences that might be seen with larger population samples. NHANES relies on one examination to define prevalent hypertension and control. Classification as hypertensive or non-hypertensive for untreated adults and control status in treated adults could change with repeated BP measurements on different days. The definition of hypertension based on national guidelines was consistently ≥140/≥90 mmHg during the period of this report, i.e., 1988 to 2010.18,34,44 Yet, goal systolic BP for patients with diabetes mellitus and/or CKD was <130 from 1997 to 2013.18,34 Direct comparisons of prevalence, treatment and control between 1988–1994 and 1999–2010 may be impacted by different control goals for selected populations.

Perspective

The percentage of uninsured among adults with hypertension grew from 12.3% in 1988–1994 to 17.5% in 2005–2010. Uninsured adults did not participate in the substantial improvement in hypertension control over time documented among insured adults. In the uninsured, lower percentages of awareness, aware adults treated and treated adults controlled contribute approximately equally to the disparity in hypertension control. Our analysis suggests that providing public or private healthcare insurance to uninsured adults and promoting appropriate health care utilization to diagnose, treat and control hypertension and guideline-based statin therapy could promote equity in hypertension control and vascular outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

Blood pressure (BP) control was similar in adults with and without healthcare insurance in 1988 to 1994

Uninsured adults did not experience the large rise in BP control observed in insured adults between 1988–1994 and 2005–2010

What Is Relevant?

BP control was similar in adults with public and private healthcare insurance from 1988 to 2010, although income and education were similar in uninsured and publicly insured adults and lower than privately insured adults

Healthcare insurance, at least two healthcare visits yearly and statin medications were linked with better BP control

“Summary” To improve hypertension control in uninsured adults, healthcare insurance, regular healthcare, and guideline-based treatment for BP and cholesterol could be helpful

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding Sources: The work was supported in part by NIH HL105880; United States Army, W81XWH-10-2-0057, Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, GA (Community Transformation Grant thru the South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control [SC DHEC]), and the State of South Carolina, Columbia, SC.

During the previous three years, Dr. Egan received income as a consultant to Blue Cross Blue Shield South Carolina, Daiichi-Sankyo, Medtronic, Novartis and research support from Daiichi-Sankyo, Medtronic, Novartis, and Takeda.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None of the other authors has any disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Kannel WB. Hypertension: Reflections on risks and prognostication. Med Clin North Am. 2009;93:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults. Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311:507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Healthy People 2020 hypertension control goal (HDS-12) [accessed 28 April 2014]; http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=21.

- 4.Frieden TR, Berwick DM. The “Million Hearts” initiative—preventing heart attacks and strokes. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:e27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1110421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN. US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:2043–2050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Ginsburg JA, Zalavsky AM. Unmet health needs of uninsured adults in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284:2061–2069. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.16.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duru OK, Vargas RB, Kermah D, Pan D, Norris KC. Health insurance status and hypertension monitoring and control in the United States. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks EL, Preis SR, Hwang SJ, Murabito JM, Benjamin EJ, Kelly-Hayes M, Sorlie P, Levy D. Health insurance and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Am J Med. 2010;123:741–747. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fowler-Brown A, Corbie-Smith G, Garrett J, Lurie N. Risk of cardiovascular events and death—Does insurance matter? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:502–507. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0127-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decker SL, Kostova D, Kenney GM, Long SK. Health status, risk factors, and medical conditions among persons enrolled in Medicaid vs. uninsured low-income adults potentially eligible for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2013;309:2579–2586. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schober SE, Makuc DM, Zhang C, Kennedy-Stepehenson J, Burt V. Health insurance affects diagnosis and control of hypercholesterolemia and hypertension among adults aged. United States: 2005–2008. pp. 20–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holahan J, Cook A. The U.S. economy and changes in health insurance coverage, 2000–2006. Health Affairs. 2008;27:w135–w144. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.w135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hellander I, Bhargavan R. Report from the United States: The U.S. health crisis deepens amid rising inequality—A review of data, fall 2011. Internat J Health Serv. 2012;42:161–175. doi: 10.2190/HS.42.2.a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banthin J, Masi S. CBOs estimate of net budgetary impact of the affordable care act's health insurance coverage provision has not changed much over time. [accessed 28 April 2014];Congressional Budget Office. Publication #44176, posted, May 14, 2013 ( http://www.cbo.gov/publication/44176.

- 15.Prior HHS Poverty Guidelines and Federal Register References. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. [Accessed July 14, 2014];US Department of Health and Human Resources. http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/figures-fed-reg.cfm.

- 16.Egan BM, Li J, Qanungo S, Wolfman TE. Blood pressure and cholesterol control in hypertensive hypercholesterolemic patients: A report from NHANES 1988–2010. Circulation. 2013;128:29–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes 2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S11–S66. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–2446. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.21.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Kidney Disease Education Program. Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) in evaluating patients with diabetes for chronic kidney disease. 2010 Mar; NIH Publication No. 10-6286. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Selvin E, Manzi J, Stevens LA, Van Lente F, Lacher DA, Levey AS, Coresh J. Calibration of serum creatinine in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 1988–1994, 1999–2004. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:918–926. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rose GA, Blackburn H, Gillium RF, Prineas RJ. Cardiovascular Survey Methods. 2nd. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muntner P, DeSalvo KB, Wildman RP, Raggi P, He J, Whelton PK. Trends in the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of cardiovascular disease risk factors among non-institutionalized patients with a history of myocardial infarction and stroke. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:913–920. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Analytic and Reporting Guidelines: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, NHANES III (1988–94, October 1996. National Center for Health Statistics; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Hyattsville, Maryland: [accessed April 9, 2014]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes3/nh3gui.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Analytic and Reporting Guidelines. [accessed April 9, 2014];The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) Last Update: December, 2005. Last Correction, September 2006. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_03_04/nhanes_analytic_guidelines_dec_2005.pdf.

- 25.Analytic note regarding 2007–2010 survey design changes and combining data across other survey cycles. [accessed April 9, 2014]; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/analyticnote_2007-2010.pdf.

- 26.U.S. Census Bureau. Population by sex and selected age groups: 2000–2010. [accessed 21 March 2014]; http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-03.pdf.

- 27.Katz AB, Felland LE, Hill I, Stark LB. A long and winding road: Federally qualified health centers, community variation and prospects under reform. Res Brief. 2011;21:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Access to health care for the uninsured in rural and frontier America. [accessed 14 July 2014];National Rural Health Association, May 1999. www.ruralhealthweb.org/index.cfm.

- 29.Gai Y, Gu NY. Association between insurance gaps and continued antihypertensive medication usage in a US national representation population. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:1276–1280. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egan BM, Li J, Shatat IF, Fuller JM, Sinopoli A. Closing the gap in hypertension control between younger and older adults: NHANES 1988 to 2010. Circulation. 2014;129:2052–2061. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.007699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, Goff DC, Murphy TP, Toto RD, White A, Cushman WC, White W, Sica D, Ferdinand K, Giles TD, Falkner B, Carey RM American Heart Association Professional Education Committee. Resistant hypertension: Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2008;51:1403–1419. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.189141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN, Brzezinski WA, Ferdinand KD. Uncontrolled and apparent treatment resistant hypertension in the U.S. 1988–2008. Circulation. 2011;124:1046–1058. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cutler JA, Sorlie PD, Wolz M, Thom T, Fields LE, Roccella EJ. Trends in the hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control rates in United States adults between 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Hypertension. 2008;52:818–827. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.113357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross JS, Bradley EH, Busch SH. Use of health care services by lower income and higher-income uninsured adults. JAMA. 2006;295:2027–2036. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ostchega Y, Hughes JP, Wright JD, McDowell MA, Louis T. Are demographic characteristics, health care access and utilization, and comorbid conditions associated with hypertension among adults? Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:159–165. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2007.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahluwalia JS, McNagny SE, Rask KJ. Correlates of controlled hypertension in indigent, inner-city hypertensive patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:7–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.12107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Briasoulis A, Agarwal V, Valachis A, Messerli FH. Antihypertensive effects of statins: A meta-analysis of prospective controlled studies. J Clin Hypertens. 2013;15:310–320. doi: 10.1111/jch.12081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta AK, Nasothimiou EG, Chang CL, Sever PS, Dahlöf B, Poulter NR. Baseline predictors of resistant hypertension in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcome Trial (ASCOT): a risk score to identify those at high-risk. J Hypertension. 2011;29:2014–2013. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834a8a42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pencina MJ, Mavar-Boggan AM, D'Agostino RB, Williams K, Neely B, Sniderman AD, Peterson ED. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1422–1431. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zalavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Use of health services by previously uninsured Medicare beneficiaries. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:143–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa067712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McWilliams JM, Meara E, Zalavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Health of previously uninsured adults after acquiring Medicare coverage. JAMA. 2007;298:2886–2894. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.24.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Putting men's health care disparities on the map: Examining racial and ethnic disparities at the state level. [accessed 28 April 2014];Access and Utilization Highlights: The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation, September 2012, publication #8366. http://kff.org/disparities-policy/report/putting-mens-health-care-disparities-on-the/

- 44.The 1984 Report of the Joint National Committee on detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1045–1057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.