Abstract

Purpose of review

To discuss the changing landscape of home dialysis in the United States over the past decade, including recent research on clinical outcomes in patient undergoing peritoneal dialysis (PD) and home hemodialysis (HHD), and to describe the impact of recent payment reforms for patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD).

Recent findings

Accumulating evidence supports that clinical outcomes for patients treated with PD or HHD are as good as or better than for patients treated with conventional in-center hemodialysis (ICHD). The recent implementation of the Medicare expanded prospective payment system (PPS) for the care of ESRD patients has resulted in substantial growth in the utilization of PD in the United States. Utilization of HHD has also grown, but the contribution of the expanded PPS to this growth is less certain.

Summary

Home dialysis, including PD and HHD represent important alternatives to ICHD that are effective and patient-centered. Over the coming decade, growth in the number of ESRD patient treated with home dialysis modalities should prompt further comparative and cost effectiveness research, increased attention to racial and ethnic disparities, and investments in home dialysis education for both patients and providers.

Keywords: end stage renal disease, peritoneal dialysis, home hemodialysis, health policy

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, more than 110,000 individuals with end stage renal disease (ESRD) initiate renal replacement therapy each year, and the prevalent U.S. dialysis population currently exceeds 430,000 patients.[1] While many patients with ESRD have access to a range of dialysis modalities, more than 90% of patients undergoing maintenance dialysis use conventional in-center hemodialysis (ICHD).[1] Home dialysis modalities, including both peritoneal dialysis (PD) and home hemodialysis (HHD), represent important alternatives to conventional ICHD for patients with ESRD. Over the past decade, growing evidence supports that outcomes for patients undergoing both PD and HHD are as good or better than those for patient undergoing ICHD.[2–6]

Historically, annual per-person Medicare expenditures for ICHD have exceeded those for PD, the dominant home dialysis modality.[7] In 2009, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released a proposed rule for an expanded prospective payment system (PPS) for the Medicare ESRD program, a rule ultimately adopted and implemented on January 1, 2011.[8] Under the expanded PPS, financial incentives to dialysis providers for home dialysis services were enhanced; subsequently, the trend for a historically low growth rate in the adoption of home dialysis modalities in the U.S. seems to have now reversed.[1] In this review, we discuss the changing landscape of home dialysis in the United States over the past decade, highlight recently published studies on home dialysis modalities and patient outcomes, and describe the recent policy and payment reforms that affect delivery of home dialysis treatment to patients with ESRD.

HISTORICAL TRENDS IN UTILIZATION OF HOME DIALYSIS IN THE UNITED STATES

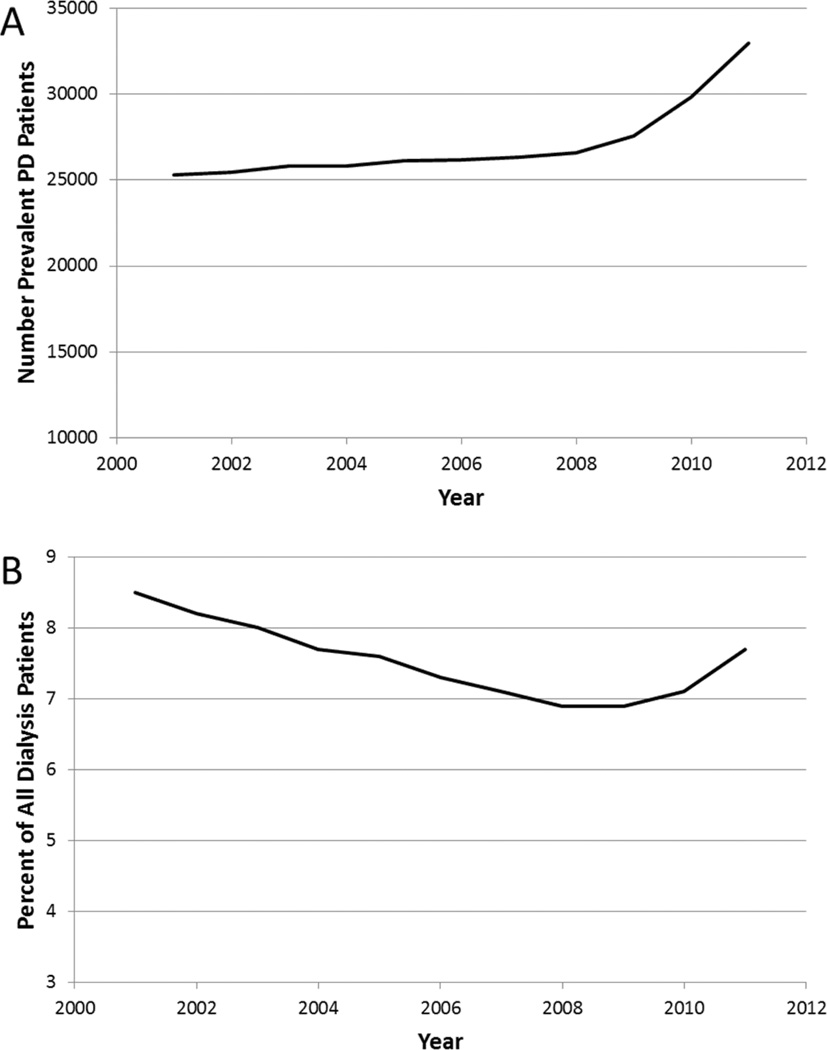

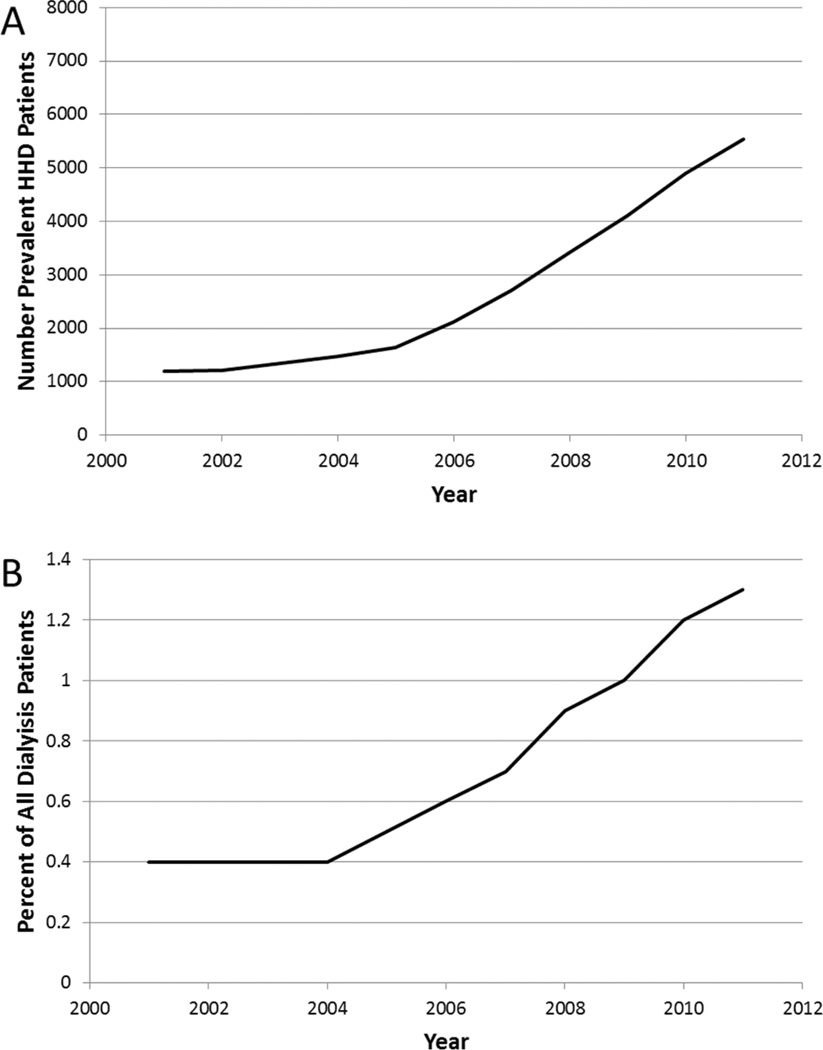

In the decade prior to introduction of the expanded PPS, the growth in the U.S. ESRD patient population was due almost exclusively to an exponential increase in the ICHD population. From 2001 through 2008, the total dialysis population in the U.S. grew from 294,731 to 383,337 patients.[1] Of this total change in the dialysis population, only 1.4% of the growth represented PD patients (Figure 1), and only 2.4% of the growth represented HHD patients (Figure 2). As of 2008, only 6.9% of the total prevalent dialysis population was being treated with PD, and <1% were being treated with HHD. Over this same time period, annual costs per patient for ICHD increased from $59,368 to $82,274. In contrast, annual costs pre patient for PD increased from $46,447 to only $62,166.[1] There are no robust cost estimates for HHD treatment in the United States, though recent data from other developed countries suggests that depending on treatment failure rates and training times, HHD can be an economically attractive option compared with ICHD.

Figure 1. Prevalent U.S. ESRD patients undergoing maintenance dialysis with peritoneal dialysis (PD), 2001 – 2011.

Panel (A) Total count; Panel (B) Percent of total dialysis patients. Data from USRDS Annual Data Report, 2013.

Figure 2. Prevalent U.S. ESRD patients undergoing maintenance dialysis with home hemodialysis (HHD), 2001 – 2011.

Panel (A) Total count; Panel (B) Percent of total dialysis patients. Data from USRDS Annual Data Report, 2013.

Prospective evaluations of dialysis modality eligibility in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease have revealed that as many as 85% of patients are medically eligible for home dialysis, particularly PD.[9] However, only one-third of ESRD patients beginning maintenance dialysis are presented with PD as an option, and only 12% of patients are presented with HHD as an option.[10] Additionally, 25 – 40% of patients would choose a home dialysis modality if the option of home therapy was presented to them.[11,12] Furthermore, the percentage of African-American and Hispanic U.S. ESRD patients treated with PD has been consistently 20–40% lower than that of Caucasian dialysis patients over the past decade.[1] Given these findings, the secular trend of dialysis modality distribution prior to implementation of the expanded PPS challenged modern standards of care quality in health care, including goals for care to be patient-centered, efficient, and equitable.

HOME DIALYSIS AND PATIENT OUTCOMES

The relationship between dialysis modality and clinical outcomes has been the subject of extensive research.[13] In general, the majority of published studies from contemporary cohorts have demonstrated either no difference in overall survival when comparing ICHD to home dialysis modalities, in particular PD, or in some cases a lower risk for death for patients treated with home dialysis.[3,5] Such findings have led to recent calls to promote a “PD First” approach when preemptive kidney transplantation is not an option, as a way to achieve benefit for not only patients, but also for providers and the larger healthcare system.[14]

Peritoneal dialysis

Given its higher prevalence relative to HHD, there are a large number of studies supporting the equivalence of PD to ICHD with respect to clinical outcomes including all-cause and cause-specific mortality, hospitalizations, infection-related complications, and quality of life. Prior to the last decade, many observational studies of the association between dialysis modality and subsequent clinical outcomes suggested a higher risk for death for patients treated with PD over the long term. The large majority of these studies used data from patients undergoing dialysis prior to 2000; the applicability of such historical data in the present era had been questioned and has prompted comparative effectiveness studies using more recent data. Mehrotra et al. used data from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) to analyze survival data for patients initiating either HD or PD in 2002–2004. Using a marginal structural model analysis, they demonstrated no significant overall difference in mortality risk in PD patients compared to HD patients, and found improvement in outcomes in PD patients in multiple subgroups of patients.[3] Yeates et al. analyzed data from the Canadian Organ Replacement Register and compared outcomes for patient initiating PD as compared to HD in Canada from 1991 to 2004.[15] Though analysis of the entire cohort found that HD had higher overall survival after 36 months of treatment, for patients entering the cohort between 2001 and 2004, risk for death was lower for PD patients during the first 2 years, and was equivalent thereafter irrespective of dialysis modality. Similarly, Weinhandl et al. used a matched pair cohort study design to study patients initiating dialysis in 2003, and found improved overall survival in patients initiating PD compared to HD.[6] Similar data are available from nationally representative data from Australia and New Zealand, Brazil, and Taiwan. Patients on PD also appear to have greater satisfaction with their overall care as well as on the impact of dialysis on their quality of life relative to patients undergoing HD.[16,17]

Home hemodialysis

Over the past decade, there has been a resurgence in interest in HHD, both because of the advent of the simple-to-operate systems such as the NxStage System One machine, but also because of growing evidence that patients undergoing HHD have similar or better outcomes relative to patients undergoing ICHD.[18] The NxStage machine uses low dialysate volumes with slow dialysate flow rates, and has been shown to have solute kinetics that compare favorably with conventional HD.[19] The NxStage machine can be used both for home short daily hemodialysis, as well as for home nocturnal hemodialysis.

Only two published randomized clinical trials have compared outcomes in patients undergoing frequent HHD and conventional ICHD. It is important to note that neither of these two clinical trials used the NxStage system; instead they used conventional hemodialysis plaftorms. Culleton et al. randomized 52 patients at 2 Canadian academic medical centers to conventional ICHD versus frequent nocturnal HHD, and found significant improvements in left ventricular mass, systolic blood pressure, and markers of mineral metabolism, as well as a greater reduction in antihypertensive medications in the HHD group compared to the conventional ICHD group.[20] Rocco et al. randomized 87 patients to three times weekly conventional ICHD or to nocturnal home hemodialysis size times per week as part of the Frequent Hemodialysis Network Nocturnal Trial.[21] Over the study follow-up, patients assigned to frequent HHD had improved control of hypophosphatemia and hypertension, but had similar findings for the co-primary outcomes of death or left ventricular mass change, and death or change in the RAND Physical Health Composite score. There have been no published randomized trials of patients undergoing short daily home hemodialysis in the United States, though multiple observational studies have shown lower risk for death compared to patients undergoing conventional ICHD.[2,5,22,23] These studies have many limitations, as do all observational studies, including concerns regarding residual confounding and various biases. Further clinical trials are needed to clarify whether HHD is robustly associated with improved clinical outcomes compared to ICHD or PD.

THE PPS AND HOME DIALYSIS INCENTIVES

Historically, the Medicare ESRD Program has incentivized home dialysis through a number of different mechanisms. First, payment to both physicians and dialysis providers for inpatient HD and PD services is identical, though costs for delivery of dialysis are lower for PD treatment compared with HD treatment.[24] Second, for new uninsured Medicare-eligible but uncovered ESRD patients, insurance coverage begins after a 90-day waiting period for patients initiating ICHD. This waiting period is waived for patients initiated on home dialysis modalities, with coverage retroactively applied to the first day of the month. Third, nephrologists receive a one-time additional payment from Medicare for oversight of training of home dialysis patients, a payment which is not provided to physicians for patients initiating ICHD. Additionally, physician reimbursement from Medicare for a single monthly face-to-face visit with a home dialysis patient is equal to the payment for 2–3 monthly visits for ICHD patients. Furthermore, this one visit requirement can be waived by Medicare fiscal intermediaries on a case-by-case basis, provided that the patient’s physician has documented that he or she has "actively and adequately managed" the patient's care. However, even with these payment incentives, numerous factors have been identified as potential reasons for the low utilization of home dialysis modalities.[25,26] First, ICHD patients require greater frequency and/or dose injectable medications such as erythropoiesis stimulating agents than those treated at home. In a system in which payments and hence profits depended upon a greater use of injectable medications, the profitability for providers from patients undergoing ICHD was greater. Second, given fixed overhead costs for ICHD dialysis chairs, profitability is maximized when all open slots are filled with dialyzing patients. Third, home dialysis training reimbursement to facilities may have been inadequate to cover the actual costs of such training. Fourth, graduating nephrology fellows often have not been adequately trained in provision of home dialysis, and thus may preferentially encourage patients to use ICHD.[27] And finally, many patients do not undergo dialysis modality education, and in many cases are not offered PD or HHD as options.

With the implementation of the expanded Medicare ESRD program PPS on January 1st, 2011, multiple new incentives were created to promote expansion of home dialysis services in the U.S. Overall the ESRD PPS replaced a mixed payment system that combined a bundled composite rate payment for narrow dialysis-treatment related services with separately billed fee-for-service payments for injectable medications and additional laboratory services. The expanded PPS now includes these previously separately billable items (including erythrypoesis-stimulating agents, or ESAs), and uses a case-mix adjustment, as well as adjustments for outlier cases, facility size, and geographic wage variation. There were several key stated rationales for the expanded PPS from the Medicare perspective.[8] First, the expanded PPS eliminated the incentive to overuse profitable separately billable drugs, such as ESAs, vitamin D receptor activators, and iron compounds. Second, the expanded PPS was meant to promote operational efficiency and enhance overall quality of care delivered to the ESRD Medicare population. Third, the new PPS was intended to encourage the use of home dialysis by removing the incentive to use separately billable medications as a revenue source and by standardizing payments across modalities.

The expanded PPS incentivizes home dialysis for dialysis facilities in different ways. Injectable drugs such as ESAs are now included in bundled payments, and thus the expanded PPS created a financial incentive to reduce utilization and doses of these medications. Given that patients undergoing home dialysis, particularly PD, tend to receive substantially lower ESA doses for the same achieved hemoglobin levels, this translates into an incentive for dialysis facilities to encourage patients to choose PD.[28] Though at least one study has shown that frequent hemodialysis does not result in lower ESA dose requirements, further research is needed regarding potential cost savings with respect to injectable drugs for HHD patients.[29] In addition to potential cost savings from lower utilization of injectable drugs, dialysis facility payments include a 51% add-on payment for the first 120 days of treatment. While Medicare coverage of currently eligible but previously uncovered patients starts only 90 days after date of first dialysis, coverage for patients who chose to dialyze at home begins on the first day of the month of start of dialysis. This waiver for home dialysis hence, has become a stronger financial incentive for home dialysis than it had been in the past. Furthermore, in 2013, a 50 percent increase to the home dialysis training add-on adjustment payment was announced, effective in 2014.[30]

The economic implications for dialysis facilities to the changing landscape of financial incentives around home dialysis are complex. Hornberger and Hirth recently assessed the implications for modality choice of the expanded PPS on monthly revenue and costs to dialysis facilities.[25] In their analysis, they modeled the incentives under the expanded PPS by applying the new rule to a hypothetical dialysis facility with 20 HD stations, running six shifts with 80 patients (including open capacity), along with a 16 PD patients and one PD nurse (also with open capacity). Assuming an average of 2.8 paid treatments per week, under the old composite rate payment system, they found that an additional ICHD patient would generate an operating margin of $76, compare to -$185 for PD, and -$964 for HHD. In contrast, under the new PPS, one additional ICHD patient would generate a margin of $86, compared to $201 for PD and -$796 for HD. Thus, the new PPS is expected to result in better operating margins for dialysis facilities for all modalities, but with PD having the most substantial gain and leading to a clear financial advantage to provision of PD services. Additional analyses showed that potential profitability of HHD was dependent on the number of treatments paid for by the fiscal intermediary, a number which varies considerably across the country, ranging from 3.2–4.8 treatments per week.

LOOKING FORWARD: EMERGING TRENDS IN UTILIZATION OF HOME DIALYSIS

The latest data regarding incident and prevalent ESRD patients reported in the 2013 Annual Data Report of the United States Renal Data System (USRDS) is for 2011, the year of implementation of the expanded PPS. However, analyses of modality distribution have noted that substantial growth in the use of home dialysis in, particularly in patients in their first year or two of dialysis treatment, immediately prior to implementation of the bundle.[31] Of all prevalent dialysis patients, the percentage of patients treated with PD remained constant at 6.9% from 2008–2009 (Figure 1). In 2010, this percentage climbed to 7.2%, before jumping to 7.7% in 2011. The total number of prevalent PD patients grew from 26,595 in 2008 to 32,944 in 2011, representing a substantial 24% growth. That an increase in PD growth occurred immediately prior to implementation of the PPS may have represented a shift in anticipation of favorable financial incentives for dialysis facilities, though this has not been well studied. Unpublished reports seem to suggest the rate of growth in the PD population in the United States has only accelerated.

In contrast to PD, there was a slow steady climb in the number of prevalent HHD patients between 2008 (3,415) and 1011 (5,535), without an inflection point or significant change in the growth rate either immediately preceding or coincident with the implementation of the expanded PPS (Figure 2). However, the proportional use of HHD continues to increase relative to all dialysis patients, with 1.3% of prevalent patient using HHD in 2011 compared to 0.9% in 2008. Ongoing monitoring is needed to assess the continued impact of the expanded PPS on dialysis modality distribution.

CONCLUSIONS

The growth of home dialysis in the United States has the potential to enhance patient-centeredness of threapy for patients with ESRD, while maintaining clinical effectiveness, and potentially offering substantial cost savings. Going forward, further research on comparative effectiveness of dialysis modalities, as well as health services research around patient preferences and values regarding dialysis modality choices, will be critical to understanding which patients will beneft best from home dialysis therapy. To achieve safe and maximally effective growth in home dialysis, it will be critical to adequately train the next generation of nephrologists through improvements in training in home dialysis for nephrology fellows. Additionally, determining appropriate health care quality metrics for home dialysis will be an important challenge in the coming years, given that the existing Medicare ESRD Quality Incentive Program has been designed for ICHD, with only a subset of measures applicable to home dialysis patients. New platforms for delivery of home dialysis, such as the Wearable Artifical Kidney (WAK, Blood Purificiation Technologies Inc., Beverly Hills, CA) are actively being developed, and will provide exciting new possibilities over the coming decade to improve the lives of patients living with ESRD.

In summary, the expanded PPS has already had a significant impact on the utilization of PD in the United States; while HHD utilization has grown, the contribution of the expanded PPS to this growth is less certain. There is a need to maintain continued oversight of clinical effectiveness, racial and ethnic disparities, and differential costs with the changing landscape of delivery of dialysis therapy.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

M.B.R is supported by NIH/NIDDK grant 5T32DK007467-30.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:

M.B.R. reports no conflicts of interest. R.M. has received grant support and/or honoraria from Baxter Healthcare.

Contributor Information

Matthew B. Rivara, Email: mbr@uw.edu.

Rajnish Mehrotra, Email: rmehrotr@uw.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2013 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johansen KL, Zhang R, Huang Y, et al. Survival and hospitalization among patients using nocturnal and short daily compared to conventional hemodialysis: a USRDS study. Kidney Int. 2009;76(9):984–990. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra R, Chiu Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Bargman J, Vonesh E. SImilar outcomes with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(2):110–118. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pauly RP, Maximova K, Coppens J, et al. Patient and Technique Survival among a Canadian Multicenter Nocturnal Home Hemodialysis Cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(10):1815–1820. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00300110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinhandl ED, Liu J, Gilbertson DT, Arneson TJ, Collins AJ. Survival in Daily Home Hemodialysis and Matched Thrice-Weekly In-Center Hemodialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(5):895–904. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011080761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinhandl ED, Foley RN, Gilbertson DT, Arneson TJ, Snyder JJ, Collins AJ. Propensity-Matched Mortality Comparison of Incident Hemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(3):499–506. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tina Shih Y-C, Guo A, Just PM, Mujais S. Impact of initial dialysis modality and modality switches on Medicare expenditures of end-stage renal disease patients. Kidney Int. 2005;68(1):319–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program; end-stage renal disease prospective payment system. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2010;75(155):49029–49214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mendelssohn DC, Mujais SK, Soroka SD, et al. A prospective evaluation of renal replacement therapy modality eligibility. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(2):555–561. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehrotra R, Marsh D, Vonesh E, Peters V, Nissenson A. Patient education and access of ESRD patients to renal replacement therapies beyond in-center hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2005;68(1):378–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacson E, Jr, Wang W, DeVries C, et al. Effects of a Nationwide Predialysis Educational Program on Modality Choice, Vascular Access, and Patient Outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(2):235–242. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maaroufi A, Fafin C, Mougel S, et al. Patients’ preferences regarding choice of end-stage renal disease treatment options. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37(4):359–369. doi: 10.1159/000348822. In this prospective single-center cohort study, 42% of patients with advanced chronic kidney disease expressed a preference for PD, but less than one quarter of patients were ultimately treated with PD.

- 13.Vonesh EF, Snyder JJ, Foley RN, Collins AJ. Mortality studies comparing peritoneal dialysis and hemodialysis: what do they tell us? Kidney Int Suppl. 2006;(103):S3–S11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ghaffari A, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Lee J, Maddux F, Moran J, Nissenson A. PD First: Peritoneal Dialysis as the Default Transition to Dialysis Therapy. Semin Dial. 2013;26(6):706–713. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12125. This excellent review summarizes evidence on clinical outcomes, health-related quality of life, cost, and patient preferences regarding peritoneal dialysis. The authors argue for a “PD First” approach, where PD is offered as the default dialysis modality for new ESRD patients.

- 15.Yeates K, Zhu N, Vonesh E, Trpeski L, Blake P, Fenton S. Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis are associated with similar outcomes for end-stage renal disease treatment in Canada. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(9):3568–3575. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juergensen E, Wuerth D, Finkelstein SH, Juergensen PH, Bekui A, Finkelstein FO. Hemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis: Patients’ Assessment of Their Satisfaction with Therapy and the Impact of the Therapy on Their Lives. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1191–1196. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01220406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown EA, Johansson L, Farrington K, et al. Broadening Options for Long-term Dialysis in the Elderly (BOLDE): differences in quality of life on peritoneal dialysis compared to haemodialysis for older patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(11):3755–3763. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tennankore KK, Chan CT, Curran SP. Intensive home haemodialysis: benefits and barriers. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(9):515–522. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohn OF, Coe FL, Ing TS. Solute kinetics with short-daily home hemodialysis using slow dialysate flow rate. Hemodial Int Symp Home Hemodial. 2010;14(1):39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2009.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Culleton BF, Walsh M, Klarenbach SW, et al. Effect of frequent nocturnal hemodialysis vs conventional hemodialysis on left ventricular mass and quality of life: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(11):1291–1299. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.11.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocco MV, Lockridge RS, Beck GJ, et al. The effects of frequent nocturnal home hemodialysis: the Frequent Hemodialysis Network Nocturnal Trial. Kidney Int. 2011;80(10):1080–1091. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kjellstrand C, Buoncristiani U, Ting G, et al. Survival with short-daily hemodialysis: Association of time, site, and dose of dialysis. Hemodial Int. 2010;14(4):464–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4758.2010.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nesrallah GE, Lindsay RM, Cuerden MS, et al. Intensive Hemodialysis Associates with Improved Survival Compared with Conventional Hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(4):696–705. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011070676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee H, Manns B, Taub K, et al. Cost analysis of ongoing care of patients with end-stage renal disease: The impact of dialysis modality and dialysis access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40(3):611–622. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.34924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hornberger J, Hirth RA. Financial Implications of Choice of Dialysis Type of the Revised Medicare Payment System: An Economic Analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(2):280–287. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young BA, Chan C, Blagg C, et al. How to Overcome Barriers and Establish a Successful Home HD Program. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(12):2023–2032. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07080712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berns JS. A Survey-Based Evaluation of Self-Perceived Competency after Nephrology Fellowship Training. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(3):490–496. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08461109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duong U, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Molnar MZ, et al. Mortality Associated with Dose Response of Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents in Hemodialysis versus Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. Am J Nephrol. 2012;35(2):198–208. doi: 10.1159/000335685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ornt DB, Larive B, Rastogi A, et al. Impact of frequent hemodialysis on anemia management: results from the Frequent Hemodialysis Network (FHN) Trials. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc. 2013;28(7):1888–1898. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program; end-stage renal disease prospective payment system, quality incentive program, and durable medical equipment, prosthetics, orthotics, and supplies. Fed Regist. 2013;78(231):72155–72253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirth RA, Turenne MN, Wheeler JRC, et al. The Initial Impact of Medicare’s New Prospective Payment System for Kidney Dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(4):662–669. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.