Abstract

Objective

To describe national trends in discretionary calories from sugar sweetened beverage (SSB) and snacks by age-specific body weight categories and by age- and weight-specific race/ethnicity groups. Examining these sub-populations is important as population averages may mask important differences.

Design and Methods

We used 24-hour dietary recall data obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2010 among children aged 2 to 19 (N=14,092). Logistic and linear regression methods were used to adjust for multiple covariates and survey design.

Results

The number of calories from SSBs declined significantly for nearly all age-specific body weight groups. Among overweight or obese children, significant declines in the number of calories from SSBs were observed among Hispanic children aged 2 to 5 (117 kcal vs. 174 kcal) and white adolescents aged 12 to 19 (299 kcal vs. 365 kcal). Significant declines in the number of calories from salty snacks were observed among white children aged 2 to 5 (192 kcal to 134 kcal) and 6 to 11 (273 kcal vs. 200 kcal).

Conclusions

The decrease in SSB consumption and increase in snack consumption observed in prior research are not uniform when children are examined within sub-groups accounting for age, weight and race/ethnicity.

Keywords: SSBs, snacks, body weight

Introduction

Discretionary calories from sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) and snacks make up a considerable portion of children's diet. This consumption has been linked to increased body weight (1, 2), nutrition-related diseases such as type 2 diabetes (3), and other negative health consequences (e.g., dental decay) (4). American youth consume roughly 150 calories daily from SSBs (or 8 percent of daily intake)(5) which is equivalent to about one 12 ounce can of soda. This intake rate is higher than the American Heart Association recommendation of no more than 450 calories (36 ounces) per week from SSBs (based on a 2000 calorie per day diet) and inconsistent with the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans which recommends reducing SSB consumption to achieve a healthy diet (6). While still high (5), consumption of SSBs appears to be declining among children for the first time in decades (7-9). The most recent estimates of youth snack consumption (among children ages 2 to 18), compare data from 1989 to 2006, and find that consumption increased significantly from 22% to 27% of daily calories over the period (10). That study examined the following sweet (cakes, cookies, pies, bars, ice cream, and gelatin desserts) and salty (crackers, chips, popcorn, and pretzels) snacks.

Prior studies identifying declines in SSB consumption or increases in snack consumption examine differences by sex, age, or race-ethnicity groups, but do not consider differences by body weight category or by body weight category and race/ethnicity. Because population averages may mask important differences among sub-populations, it is possible that the observed changes in SSB or snack consumption are not uniformly occurring among healthy weight and overweight children or among specific race/ethnicity groups, as they have demonstrated marked differences in consumption of calories from SSBs and snacks in earlier studies among children ages 2 to 19 (9-11). Understanding differences among these sub-populations is also important given that obesity prevalence and many of its risk factors (e.g., type 2 diabetes, hypertension) are considerably higher among blacks and Hispanics compared to whites (12, 13). Even though obesity appears to be leveling, these signs of progress are absent for the black and Hispanic populations (12). In addition, it is unknown whether snack consumption has begun to decline similar to the observed trends in SSBs. Up-to-date trends in consumption of discretionary calories from SSBs and snacks which examine differences by youth body weight overall and among specific race/ethnicity groups are critical for identifying concrete and appropriately tailored behavioral targets for children who could benefit most from interventions. Knowledge in this area may also inform public health and clinical interventions designed to reduce consumption of these discretionary calories from SSBs and snacks.

The primary purpose of this study is to describe national trends in consumption of discretionary calories from SSBs and snacks by age-specific body weight categories among children ages 2 to 19. We additionally examined variations in these national trends by age- and weight-specific race/ethnicity groups.

Methods

Data and Design

Data was obtained from the nationally representative continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 2003-2010). We focus on the time frame from 2003 to 2010 (rather than 1999-2010) in order to focus on more recent data and to combine smaller blocks of time (i.e., we compare 2003-2006 to 2007-2010). The NHANES is a population-based survey designed to collect information on the health and nutrition of the U.S. population. Participants were selected based on a multi-stage, clustered, probability sampling strategy. Our analysis combined the continuous NHANES data collection (2003–2010) to look at overall trends during that time period (comparing 2003 to 2006 with 2007 to 2010). A complete description of data-collection procedures and analytic guidelines are available elsewhere (www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm).

Study Sample

The study sample consists of children with completed 24-hour dietary recalls. Survey respondents were excluded if they had diabetes (n=60) or were pregnant (n=105) at the time of data collection or if their dietary recall was incomplete or unreliable (as determined by the NHANES staff). The final analytical sample included 14,092 children aged 2 to 19, who were divided into three groups.

Measures

Beverages and Snacks

Survey respondents self-reported all food and beverages consumed in a prior 24-hour period (midnight to midnight) and reported type, quantity and time of each food and beverage consumption occasion. The main meal planner/preparer was asked to report intake information for any children under the age of 12. Following the dietary interview, all reported food and beverage items were systemically coded using the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Food and Nutrient Database. Caloric content and other nutrients derived from each consumed food or beverage item were calculated based on the quantity of food and beverages reported and the corresponding nutrient contents by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

We identified SSBs (from 162 beverage items) including the following drink types: soda, sport drinks, fruit drinks and punches, low-calorie drinks, sweetened tea, and other sweetened beverages. See Appendix A for more details.

We based our categorization of snacks off of a modified version of the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill food grouping system, described in detail elsewhere (14) and used in prior publications examining trends in snacking (10). We identified two mutually exclusive snack categories in the NHANES 2003-2010 (from 772 snack items): 1) salty snacks (including hush puppies, all type of chips, popcorn, pretzels, party mixes, french fries, and potato skins (76 items) and 2) sweet snacks, including ice cream, other desserts (custards, puddings, mousse, etc.), sweet rolls, cakes, pastries (crepes, cream puffs, strudels, croissants, muffins, sweet breads, etc.), cookies, pies, candy (696 items). The sweet snack category did not include solid foods with naturally occurring sugar such as fruit. See Appendix B for more details.

Throughout, discretionary refers to calories from the SSBs and snacks described above and non-discretionary refers to calories from all other sources.

Body Weight Status

In the NHANES, weight and height were measured using standard procedures in a mobile examination center. Weight categories were based on BMI-for-age percentiles where healthy weight was the 5th percentile to less than the 85th percentile; overweight was the 85th percentile to less than the 95th percentile; and obese is equal to or greater than the 95th percentile.(15)

Other Measures

Sociodemographic measures were categorized as follows: age (2-5 years, 6-11 years, 12-19 years), sex (male, female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic other), and household income. Household income was based on the poverty income ratio (PIR) – the ratio of self-reported household income to a family's appropriate poverty threshold. We dichotomized the PIR into lower and higher income groups based on eligibility for food assistance programs (i.e. ≤ 130% of the poverty level).

Analysis

All analyses were weighted to be representative of the general population and conducted using STATA, version 12 (StataCorp, L.P., College Station, TX) to account for the complex sampling structure, and the day of the week the dietary recall was collected. For each of the outcome variables – percent drinkers/snackers and energy intake (overall, and from SSBs, sweet snacks, and salty snacks) – multiple regressions were used to adjust for potential differences in sociodemographic characteristics. For the binary outcomes (percent drinkers/snackers), we used Logit models. For continuous outcomes (calories from sweet snack, salty snacks, and total calories), we used ordinary least squares models. We stratified all analyses by age group and used the same analytic approach for each. First, to examine time and weight trends, we included an interaction term between weight status (healthy vs. overweight/obese) and time period (2003-2006 vs. 2007-2010). Second, to identify sub-population trends, we stratified these models by race/ethnicity as well as age. In all models significance was determined at p < 0.05. Using post-estimation commands, we calculated the predicted percent of SSB drinkers and sweet/salty snackers as well as the predicted number of calories for energy intake overall, from SSBs, sweet snacks, and salty snacks, among consumers. Consumers refer to those individuals who reported intake of the SSB or snack on the prior day. The analysis of calories was restricted to those who consumed any SSBs (to estimate calories from SSBs), to those who consumed salty snacks (to estimate calories from salty snacks), and to those who consumed sweet snacks (to estimate calories from sweet snacks).

Results

The characteristics of the NHANES 2003-2010 sample are presented in Table 1, by age group and body weight category.

Table 1.

Characteristics of US children and adolescents in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-20101 overall and by weight status2, N (%)

| 2003-2006 (N=7,730) | 2007-2010 (N=6,362) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Age 2-5 (N=1,663) |

Age 6-11y (N=1,906) |

Age 12-19y (N=4,161) |

Age 2-5 (N=1,696) |

Age 6-11y (N=2,265) |

Age 12-19y (N=2,401) |

||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| Healthy Weight |

Overweight /Obese |

Healthy Weight |

Overweight /Obese |

Healthy Weight |

Overweight /Obese |

Healthy Weight |

Overweight /Obese |

Healthy Weight |

Overweight /Obese |

Healthy Weight |

Overweight /Obese |

||

| Total | 1,193 (74) |

409 (26) |

1,196 (68) |

698 (32) |

2,602 (65) |

1,516 (35) |

1,273 (78) |

423 (22) |

1,431 (66) |

834 (34) |

1,516 (67) |

885 (33) |

|

| Sex | |||||||||||||

| Female | 606 (77) |

203 (23) |

628 (68) |

361 (32) |

1,236 (66) |

752 (34) |

601 (78) |

187 (22) |

715 (68) |

416 (32) |

713 (70) |

423 (30) |

|

| Male | 587 (72) |

206 (28) |

568 (68) |

337 (32) |

1,366 (65) |

764 (35) |

672 (77) |

236 (23) |

716 (65) |

418 (35) |

803 (64) |

462 (36) |

|

| Race-ethnicity | |||||||||||||

| NH white3 | 353 (74) |

117 (26) |

351 (68) |

156 (32) |

723 (66) |

375 (34) |

477 (81) |

124 (19) |

490 (69) |

215 (31) |

537 (71) |

242 (29) |

|

| NH black3 | 337 (77) |

106 (23) |

378 (65) |

231 (35) |

898 (61) |

549 (39) |

242 (72) |

90 (28) |

311 (62) |

210 (38) |

350 (61) |

227 (39) |

|

| Hispanic | 423 (72) |

165 (28) |

385 (61) |

278 (39) |

852 (62) |

545 (38) |

458 (71) |

184 (29) |

537 (59) |

369 (41) |

536 (59) |

372 (41) |

|

| NH Other | 80 (83) |

21 (17) |

80 (82) |

20 (33) |

124 (78) |

47 (22) |

96 (81) |

25 (19) |

93 (66) |

40 (27) |

93 (72) |

44 (28) |

|

| Household income | |||||||||||||

| Lower income4 | 561 (73) |

205 (27) |

468 (65) |

292 (35) |

975 (60) |

640 (40) |

596 (74) |

216 (26) |

598 (65) |

357 (35) |

571 (62) |

364 (38) |

|

| Higher income4 | 581 (76) |

184 (24) |

692 (69) |

383 (31) |

1,502 (67) |

802 (33) |

588 (81) |

167 (19) |

743 (68) |

407 (32) |

808 (70) |

437 (30) |

|

Percentage of US pediatric population estimated with survey weights to adjust for unequal probability of sampling

Weight categories are based on BMI-for-age percentiles where healthy weight is the 5th percentile to less than the 85th percentile; overweight is the 85th percentile to less than the 95th percentile; and obese is equal to or greater than the 95th percentile

NH = Non-Hispanic

Income level was dichotomized based on the poverty index ratio (ratio of annual family income to federal poverty line). Lower income refers to persons below 130% of poverty, which represents eligibility threshold for the federal food stamp program.

Trends in SSB and snack consumption among consumers by age-specific body weight category

Table 2 reports typical daily consumption of SSBs and snacks among children who consumed those items by age-specific body weight categories. Overall, the number of calories from SSBs declined significantly over the study period for all ages and each body weight category with the exception of overweight and obese children aged 6 to 11 (age 2 to 5 – healthy weight: 163 kcal vs. 127 kcal, overweight/obese: 189 kcal vs. 139 kcal; age 6 to 11 – healthy weight: 203 kcal vs. 176 kcal; aged 12 to 19 – healthy weight: 337 kcal vs. 298 kcal, overweight/obese: 347 kcal vs. 290 kcal). Each of the groups which experienced significant declines in SSB calories also demonstrated significant declines in total caloric intake. Among children 6 to 11, the number of calories from SSBs consumed by those who were overweight or obese was significantly higher at each time point than the number of calories from SSBs consumed by healthy weight children (2003 – 2006: 234 kcal vs. 203 kcal; 2007 – 2010: 220 kcal vs. 176 kcal). The percentage of SSB drinkers declined over the study period among one group – overweight and obese adolescents aged 12 to 19 (82% vs. 76%). Also among overweight and obese adolescents, the percentage consuming sweet snacks declined significantly over the study period (59% vs. 50%) and was significantly lower than the healthy weight adolescents in both time periods (2003 – 2006: 59% vs. 65%; 2007 – 2010: 50% vs. 64%). Overweight and obese adolescents were also the only group to demonstrate significant declines in total caloric intake overtime (2119 kcal vs. 1964 kcal) and as compared to their healthy weight counterparts in the most recent survey year (1964 kcal vs. 2245 kcal). We observed no significant declines in calories from salty and sweet snacks over the period; however in the most recent survey year, overweight/obese adolescents consumed significantly fewer calories from salty snacks than healthy weight adolescents (253 kcal vs. 295 kcal).

Table 2. SSB and snack consumption among consumers by age and weight status, NHANES 2003-2010.

| Age 2-5 | Age 6-11y | Age 12-19y | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Healthy Weight | Overweight/Obese | Healthy Weight | Overweight/Obese | Healthy Weight | Overweight/Obese | ||||||||

| 03-06 | 07-10 | 03-06 | 07-10 | 03-06 | 07-10 | 03-06 | 07-10 | 03-06 | 07-10 | 03-06 | 07-10 | ||

| Consumers, %(SE) | |||||||||||||

| SSBs | 67.5 (2.1) |

61.5 (1.4)* |

67.5 (4.1) |

62.6 (3.5) |

78.0 (1.9) |

72.1 (2.2) |

78.2 (2.6) |

74.2 (2.5) |

81.0 (2.1) |

76.3 (1.5) |

82.2 (1.6) |

75.6 (2.0)* |

|

| Salty snacks | 58.1 (2.3) |

53.0 (2.3) |

61.8 (3.8) |

53.1 (3.2) |

61.5 (2.5) |

55.4 (2.2) |

61.2 (2.4) |

56.9 (2.8) |

59.7 (1.6) |

50.9 (1.9)* |

54.0 (1.7)† |

54.3 (3.8) |

|

| Sweet snacks | 72.2 (1.7) |

70.2 (1.8) |

79.3 (2.7)† |

73.1 (3.0) |

77.8 (2.2) |

73.1 (1.8) |

67.9 (2.6)† |

72.0 (2.6) |

64.7 (2.2) |

64.3 (2.0) |

58.9 (1.9)† |

50.2 (2.8)*† |

|

| Calories, kcal(SE) | |||||||||||||

| Total | 1585.4 (23.7) |

1521.0 (19.0)* |

1804.1 (50.2)† |

1594.4 (54.4)* |

2047.7 (34.1) |

1859.7 (24.7)* |

2059.7 (45.7) |

1988.2 (39.9)† |

2440.3 (44.8) |

2244.5 (36.6)* |

2119.2 (32.8)† |

1964.4 (45.1)*† |

|

| SSBs | 163.0 (7.5) |

127.1 (4.6)* |

189.4 (9.8)† |

138.6 (15.1)* |

202.5 (9.4) |

175.8 (5.6)* |

234.0 (12.5)† |

219.8 (8.2)† |

337.3 (13.6) |

297.9 (11.2)* |

347.0 (11.6) |

289.5 (15.4)* |

|

| Salty snacks | 171.2 (10.4) |

152.3 (7.4) |

185.6 (16.3) |

152.8 (15.9) |

234.4 (10.5) |

207.3 (9.5) |

250.9 (19.4) |

225.1 (12.0) |

299.8 (8.2) |

295.1 (15.6) |

285.9 (14.7) |

252.7 (14.7)† |

|

| Sweet snacks | 215.0 (6.6) |

198.5 (7.2) |

224.7 (13.4) |

211.1 (14.2) |

334.9 (14.2) |

303.0 (15.5) |

329.4 (18.5) |

309.9 (15.4) |

369.4 (10.2) |

251.2 (11.4) |

303.4 (19.7)† |

325.7 (18.9) |

|

Note: Multivariate regression was used to adjust for sex, race/ethnicity, and household income. Consumers refer to those individuals who reported intake of the SSB or snack on the prior day. The analysis of calories was restricted to those who consumed any SSBs (to estimate calories from SSBs), to those who consumed salty snacks (to estimate calories from salty snacks), and to those who consumed sweet snacks (to estimate calories from sweet snacks).

Difference between 2003-2006 and 2007-2010 within weight and age categories significant at p<0.05.

Difference between healthy weight and overweight/obese within age categories and time periods significant at p<0.05.

Trends in SSB and snack consumption among consumers by age, body weight category and race/ethnicity

Table 3 reports typical daily consumption of SSBs and snacks among children who consumed those items by age- and body weight-specific race/ethnicity groups. Declines in the number of calories from SSBs observed in Table 2 differed considerably among the race/ethnicity sub-populations. Among children aged 2 to 5, significant declines in the number of calories from SSBs were observed among white (159 kcal vs. 124 kcal) and Hispanic (179 kcal vs. 128 kcal) children at a healthy weight and Hispanic children who were overweight or obese (174 kcal vs. 117 kcal). Among children aged 6 to 11, significant declines in the number of calories from SSBs were observed among white children at a healthy weight (208 kcal vs. 172 kcal). Among adolescents aged 12 to 19, declines in the number of calories from SSBs were observed among black children at a healthy weight (342 vs. 264 kcal) and white children who were overweight and obese (365 kcal vs. 299 kcal).

Table 3. SSB and snack consumption among consumers by race, age and weight status, NHANES 2003-2010, kcal (SE).

| Age 2-5 | Age 6-11y | Age 12-19y | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Healthy weight | Overweight/Obese | Healthy weight | Overweight/Obese | Healthy weight | Overweight/Obese | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||

| 03-06 | 07-10 | 03-06 | 07-10 | 03-06 | 07-10 | 03-06 | 07-10 | 03-06 | 07-10 | 03-06 | 07-10 | ||

| Total | |||||||||||||

| NH white | 1559.7 (38.5) |

1477.9 (27.4) |

1853.5 (72.8)† |

1631.3 (89.2) |

2087.4 (45.3) |

1848.2 (31.7)* |

2116.5 (58.5) |

2076.2 (67.8)† |

2486.5 (63.0) |

2288.1 (55.2)* |

2141.7 (45.2)† |

1967.6 (67.6)*† |

|

| NH black | 1657.9 (45.8) |

1569.1 (55.9) |

1688.7 (93.7) |

1631.2 (92.3) |

1991.1 (65.8) |

1949.3 (47.4) |

1915.8 (63.1) |

1981.2 (41.9) |

2448.1 (75.1) |

2091.3 (72.4)* |

2033.9 (56.6)† |

2017.7 (77.2) |

|

| Hispanic | 1631.6 (46.9) |

1586.5 (46.8) |

1645.0 (87.4) |

1550.2 (32.8) |

2067.3 (76.9) |

1857.7 (38.6)* |

2016.6 (61.8) |

1820.2 (59.9)* |

2402.6 (58.0) |

2229.0 (55.8)* |

2119.6 (76.1)† |

1917.6 (69.2)† |

|

| SSB | |||||||||||||

| NH white | 159.3 (10.1) |

124.1 (6.9)* |

196.7 (19.7) |

146.6 (20.6) |

207.7 (15.0) |

172.4 (8.6)* |

239.1 (18.1) |

236.3 (13.8)† |

351.4 (21.1) |

313.0 (17.8) |

365.0 (16.0) |

299.0 (27.5)* |

|

| NH black | 161.5 (13.8) |

147.2 (12.8) |

196.8 (20.0) |

179.9 (45.3) |

209.9 (11.3) |

183.2 (12.4) |

246.4 (21.8) |

249.2 (21.3)† |

341.8 (18.4) |

264.4 (17.8)* |

315.1 (29.9) |

251.7 (12.0) |

|

| Hispanic | 179.0 (13.0) |

128.2 (7.9)* |

174.0 (14.6) |

117.1 (7.7)* |

192.9 (9.9) |

184.3 (10.5) |

217.7 (21.7) |

170.9 (11.5) |

308.8 (15.8) |

296.7 (12.7) |

318.0 (20.4) |

294.4 (18.0) |

|

| Salty snacks | |||||||||||||

| NH white | 168.7 (16.6) |

133.9 (9.8) |

192.3 (22.8) |

134.1 (17.5)* |

220.0 (14.3) |

203.4 (14.3) |

273.4 (29.3) |

199.6 (14.6)* |

291.4 (12.3) |

307.0 (23.3) |

277.6 (21.1) |

237.3 (15.2)† |

|

| NH black | 206.4 (12.1) |

180.4 (12.8) |

201.2 (23.3) |

214.1 (30.2) |

258.8 (187.9) |

228.0 (16.6) |

240.5 (17.4) |

278.0 (14.8)† |

342.9 (14.1) |

282.5 (20.4)* |

282.8 (21.7) |

287.2 (34.2) |

|

| Hispanic | 165.8 (11.3) |

184.9 (17.6) |

155.8 (19.4) |

139.6 (12.5)† |

272.0 (15.1) |

201.0 (8.1)* |

205.8 (21.7)† |

231.7 (20.5) |

309.2 (17.9) |

269.2 (14.4) |

310.0 (18.9) |

277.1 (27.0) |

|

| Sweet snacks | |||||||||||||

| NH white | 217.1 (10.3) |

183.8 (11.5)* |

214.7 (21.6) |

205.0 (23.6) |

340.9 (20.1) |

308.5 (23.0) |

343.9 (26.5) |

323.9 (24.6) |

382.1 (17.6) |

351.7 (16.8) |

313.8 (25.8) |

328.6 (27.2) |

|

| NH black | 210.7 (18.7) |

210.8 (9.7) |

230.0 (25.1) |

222.5 (38.8) |

316.9 (23.7) |

301.4 (18.2) |

310.8 (41.4) |

326.4 (26.7) |

412.4 (23.4) |

388.6 (27.3) |

305.6 (17.6)† |

394.8 (41.6) |

|

| Hispanic | 210.9 (14.8) |

223.6 (16.5) |

226.8 (27.4) |

215.0 (20.0) |

329.9 (31.3) |

303.0 (15.8) |

292.0 (18.8) |

267.4 (17.0) |

313.1 (16.2) |

311.7 (21.7) |

286.1 (34.5) |

272.6 (28.0) |

|

Note: Multivariate regression was used to adjust for sex and household income; NH = Non-Hispanic. Consumers refer to those individuals who reported intake of the SSB or snack on the prior day. The analysis of calories was restricted to those who consumed any SSBs (to estimate calories from SSBs), to those who consumed salty snacks (to estimate calories from salty snacks), and to those who consumed sweet snacks (to estimate calories from sweet snacks).

Difference between 2003-2006 and 2007-2010 within weight and age categories significant at p<0.05.

Difference between healthy weight and overweight within age, race and time categories significant at p<0.05.

While no differences in calories consumed from salty and sweet snacks were observed in Table 2, we did observe a few notable trends in Table 3 after further stratifying by race/ethnicity. Among white children aged 2 to 5 and 6 to 11 who were overweight/obese, calories from salty snacks declined significantly (age 2 to 5: 192 kcal vs. 134 kcal; aged 6 to 11: 273 kcal vs. 200 kcal). Among black children aged 12 to 19 who were at a healthy weight, calories from salty snacks also declined significantly (343 kcal vs. 283 kcal). With respect to sweet snacks, significant declines in calories consumed were observed among white children aged 2 to 5 who were at a healthy weight (217 kcal vs. 184 kcal).

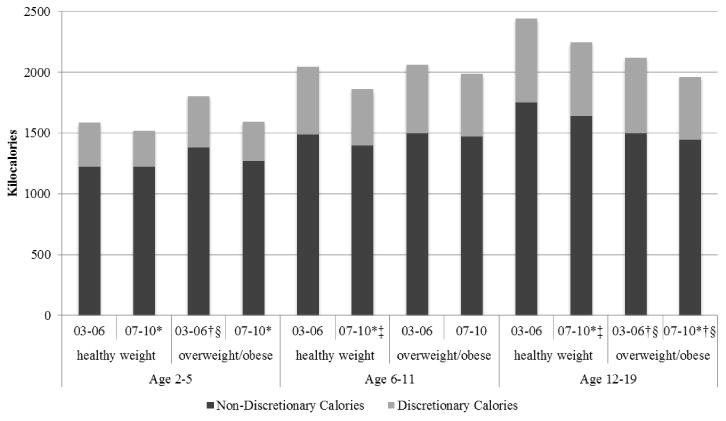

Trends in per capita discretionary versus non-discretionary calories by age and body weight category

Figure 1 illustrates trends in per capita consumption of discretionary versus non-discretionary calories by age- and body weight-specific categories. The discretionary category combines calories from SSBs, salty snacks and sweet snacks. The non-discretionary category is all other calories. Together they are equivalent to total caloric intake, which declined significantly for all groups except children aged 6 to 11 at a healthy weight (Table 2). Significant declines in discretionary calories from SSBs and snacks were observed for the following groups: children aged 2-5 (both weight groups), 6-11 year olds (healthy weight only), and adolescents aged 12-19 (both weight categories). Significant declines in non-discretionary calories were observed for children aged 6-11 and adolescents aged 12-19 who were at a healthy weight. Across the study period overweight/obese adolescents consumed fewer non-discretionary calories than their healthy weight peers (2003-2006: 1499 kcal vs. 1749 kcal; 2007-2010: 1446 kcal vs. 1642 kcal).

Figure 1.

Per capita discretionary and non-discretionary calorie intake, NHANES 2003-2010.

Note: Discretionary calories are from SSBs, salty and sweet snacks.

*Difference in discretionary calories between 2003-2006 and 2007-2010 within weight and age categories significant at p<0.05.

† Difference in discretionary calories between healthy weight and overweight within age categories and time periods significant at p<0.05.

‡ Difference in non-discretionary calories between 2003-2006 and 2007-2010 within weight and age categories significant at p<0.05.

§ Difference in non-discretionary calories between healthy weight and overweight within age categories and time periods significant at p<0.05.

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper examined trends in consumption of discretionary calories – SSBs, salty snacks and sweet snacks, which comprise a considerable portion children's diet – by age, body weight category and race/ethnicity (excluding individuals with diabetes or who were pregnant at the time of the survey). We found that the number of calories from SSBs declined significantly from 2003 to 2010 for nearly all age groups regardless of body weight and that the number of calories from salty and sweet snacks remained constant for all groups over the period. Still, levels of SSB and snack consumption from 2003-2010 are unacceptably high.

Interestingly, further stratification by race/ethnicity within each age and body weight category presents a more complicated story for the trends in SSB and snack consumption. The near uniform declines in calories from SSBs appear to be driven by different race/ethnicity groups, depending on the age of the children. For example, among overweight or obese children, significant declines in the number of calories from SSBs were only observed among Hispanic children aged 2 to 5 and white adolescents aged 12 to 19 while significant declines in the number of calories from salty snacks were only observed among overweight or obese white children aged 2 to 5 and aged 6 to 11.

Also notable is the finding that white adolescents aged 12 to 19 who were overweight or obese were the only sub-group to demonstrate a significant decline in total calories over the study period and lower caloric intake than their healthy weight counterparts in the most recent study period. In other words, heavier white adolescents appear to be eating fewer calories overtime and currently eat fewer calories than healthy weight white adolescents, suggesting that messages about reducing SSB consumption may be reaching this group most effectively.

The findings related to trends in discretionary (SSBs and snacks) versus non-discretionary (all else) calories are also interesting. The results suggests that healthy weight children age 6 and older are reducing calories from all calorie sources (discretionary and non-discretionary) whereas most overweight/obese children are concentrating their dietary changes on discretionary calories from SSBs and snacks. Generally, the implication is that messages about reducing consumption of SSBs and other discretionary calories from snacks appear to be reaching the nation's youth.

Like other studies (5, 7-9, 16), these results also indicate declines in calories from SSB overtime. However, unlike prior estimates which did not include age-specific body weight categories or age and body weight-specific race/ethnicity groups, we observed considerable variation in the trends of SSB consumption. Also unlike earlier work which suggests that calories from salty and sweet snack consumption has increased considerably overtime (10), we did not observe a positive trend among any sub-group included in the analysis. In fact, we observed declines in consumption of calories from salty snacks among overweight and obese children aged 2 to 5 and 6 to 11 as well as healthy weight children aged 12 to 19. This may, in part, be related to differences in the definitions of snacks and time frame of our analysis compared to prior ones.

Considerable attention has focused on policy and environmental changes which may have contributed to the recent decline in calories from SSB and flattening of calories from snacks from 2003 to 2010. Consumption of snacks and beverages may also be influenced by changes in the school setting. Namely, from 2000 to 2006, the percentage of school districts prohibiting vending machines offering high-calorie, low-nutrition foods and beverages increased; schools selling water in vending machines or school stores increased; and schools selling cookies, cake, or other high-fat baked goods in vending machines or school stores decreased (17). In addition, USDA requires that schools participating in the National School Lunch Program make plain drinking water available to students at no cost during the lunch meal periods at the locations where meals are served (18). Generally, research shows that schools are making some progress in in improving the school food environment (19). In addition, the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004 (Public Law 108-265) “strongly discourages” marketing of low-nutrition foods and beverages at school (20). With respect to SSBs, there has been a significant reduction in exposure to SSB advertising on television among children from 2003 to 2009 (21) as well as in students' access to soda in schools (22). In addition, dozens of advocacy organizations and health departments around the country have had very active media campaigns to discourage SSB consumption (23).

Because we use cross-sectional data, the drivers of the observed declines in SSB consumption, leveling of the trends in snacking, and how these patterns differ among the sub-populations included in this analyses are unknowable from these data. More research is needed to understand whether policies or environmental changes are differentially impacting certain groups as well as other important drivers of these patterns among age, body weight and race/ethnicity –specific sub-populations.

The present study has several limitations. First, our reliance on single 24-hour dietary recalls may introduce inaccuracy and bias to our analyses due to: underreporting, unreliability, and conversion error. Previous research indicates that adults underreport their dietary consumption by approximately 25% (24, 25). A single 24-hour dietary recall may not accurately represent usual dietary intake for an individual. Lack of reliability of the dietary recall, with respect to overall eating habits, will reduce the precision of our estimates but it will not bias our regression estimates where total energy intake is the dependent variable (26). Inaccuracy exists in the conversion of reported beverage consumption to energy intake because the assumptions on serving size and food composition are defined by the food and nutrient database. Second, the NHANES data are cross-sectional, which only allows us to address associations rather than causality. Third, our inclusion of low calorie beverages in the SSB category may bias our results related to energy intake towards zero. However, only a small fraction of all the beverages in the SSBs category are low calorie, so we do not expect this to significantly impact the results. Fourth, our use of age and body weight-specific race/ethnicity groups may have reduced the power to detect differences overtime. Fifth, there may be differences in the reporting of dietary intake among various age or weight sub-populations. Sixth, dietary recall for children under 12 is reported by main meal planner which may lead to some under-reporting for this group.

To conclude, the uniform or near uniform declines in SSB consumption observed in prior research are not consistent when children are examined within smaller sub-groups which account for their age, body weight and race/ethnicity, suggesting that averages may be masking important differences among sub-populations. Also unlike prior research, these results suggest a leveling (rather than increase) in calories from snacks among children. Even with declines in SSB consumption observed among some groups and a leveling of snack consumption among most children groups, efforts to reduce youth consumption of discretionary calories from SSBs and snacks should remain at the forefront of obesity-related policy efforts as current levels remain unacceptably high among all children.

What's Known on This Subject.

Discretionary calories from sugar-sweetened beverages and snacks make up a considerable portion of children's diet and are associated with increased body weight.

Consumption of SSBs appears to be declining and consumption of snacks appears to be increasing.

What This Study Adds:

This study provides up-to-date trends on SSB and snack consumption by age-specific weight categories and by age- and weight-specific race/ethnicity categories.

The decline in SSB and leveling of snack consumption are not uniform; for example, among overweight or obese children, significant declines in the number of calories from SSBs were only observed among Hispanic children aged 2 to 5 and white adolescents aged 12 to 19.

Efforts to reduce youth consumption of SSBs and snacks should remain at the forefront of obesity-related policy efforts as current levels are unacceptably high among all children.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This work was supported by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (5K01HL096409).

Abbreviations

- SSBs

sugar-sweetened beverages

Appendix A – Coding Definition for Beverage Categories: NHANES 2003-2010

-

Sugar Sweetened Beverages (SSB) – includes all sodas, fruit drinks, sport drinks, low-calorie drinks, and other beverages (sweetened tea, rice drinks, bean beverages, sugar cane beverages, horchata, non-alcoholic wines/malt beverages). (162 items)

Sport Drink – includes all drinks labeled Gatorade, Powerade or thirst quencher (4 items).

Fruit Drink – includes all fruit drinks, fruit juices and fruit nectars with added sugar (59 items).

Soda – includes all carbonated beverages with added sugar (22 items).

Low-caloric SSB– includes all beverages described as “low-calorie.” This includes fruit juices, teas and fruit drinks. (25 items)

Other SSB – includes sweetened tea, rice drinks, bean beverages, sugar cane beverages, horchata, non-alcoholic wines/malt beverages, etc. (52 items).

Diet beverages – includes all diet sodas and sugar-free carbonated soda water (14 items).

Milk – includes all whole, low-fat, skim milk and flavored milk (86 items). Flavored Milk includes fruit-flavored milk and chocolate milk (24 items).

100 % Juice (FJ) – includes all 100% juices (e.g. apple and orange) and all unsweetened juices (27 items).

Alcohol – includes all alcoholic beverages (71 items)

Note: The number of items were calculated from NHANES 2007-2010, but should include all items from 1999-2010.

Appendix B – Coding Definition for Salty and Sweet Snack Categories: NHANES 2003-2010

Salty snacks, including hush puppies, all type of chips, popcorn, pretzels, party mixes, french fries, and potato skins (76 items)

Sweet snacks, including ice cream, other desserts (custards, puddings, mousse, etc.), sweet rolls, cakes, pastries (crepes, cream puffs, strudels, croissants, muffins, sweet breads, etc.), cookies, pies, candy (696 items)

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: All authors have no financial disclosures relevant to this article.

Conflict of Interest: All authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose

References

- 1.Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. 2013;14:606–619. doi: 10.1111/obr.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nicklas TA, Yang SJ, Baranowski T, Zakeri I, Berenson G. Eating patterns and obesity in children. The Bogalusa Heart Study. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Circulation. 2010;121:1356–1364. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.876185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tahmassebi JF, Duggal MS, Malik-Kotru G, Curzon ME. Soft drinks and dental health: a review of the current literature. J Dentistry. 2006;34:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kit BK, Fakhouri TH, Park S, Nielsen SJ, CL O. Trends in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth and adults in the United States: 1999-2010. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013 doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.057943. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular H, Risk Reduction in C, Adolescents, National Heart L, Blood I. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128(Suppl 5):S213–256. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2107C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon PA, Lightstone AS, Baldwin S, Kuo T, Shih M, Fielding JE. Declines in Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption Among Children in Los Angeles County, 2007 and 2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10 doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi L, van Meijgaard J. Substantial decline in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among California's children and adolescents. Int J Gen Med. 2010;3:221–224. doi: 10.2147/ijgm.s12464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han E, Powell LM. Consumption patterns of sugar-sweetened beverages in the United States. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piernas C, Popkin BM. Trends in snacking among U.S. children. Health Aff. 2010;29:398–404. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang YC, Bleich SN, Gortmaker SL. Increasing caloric contribution from sugar-sweetened beverages and 100% fruit juices among US children and adolescents, 1988-2004. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1604–1614. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Bowman BA, Dietz WH, Vinicor F, Bales VS, et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Popkin BM, Haines PS, Siega-riz AM. Dietary patterns and trends in the United States: the UNC-CH approach. Appetite. 1999;32:8–14. doi: 10.1006/appe.1998.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic—report of a WHO consultation on obesity. WHO; Geneva: 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welsh JA, Sharma AJ, Grellinger L, Vos MB. Consumption of added sugars is decreasing in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:726–734. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.018366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Toole TP, Anderson S, Miller C, Guthrie J. Nutrition services and foods and beverages available at school: results from the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006. J School Health. 2007;77:500–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increasing Access to Drinking Water in Schools. US Dept. of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Story M, Nanney MS, Schwartz MB. Schools and obesity prevention: creating school environments and policies to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Milbank Q. 2009;87:71–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004. Congress t (ed) No 108-265. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell LM, Schermbeck RM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ, Braunschweig CL. Trends in the nutritional content of television food advertisements seen by children in the United States: analyses by age, food categories, and companies. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:1078–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terry-McElrath YM, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Factors affecting sugar-sweetened beverage availability in competitive venues of US secondary schools. J School Health. 2012;82:44–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yale Rudd Center for Food and Obesity Policy. Sugar-Sweetened Beverages: Public Health Campaigns. Yale University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bingham SA, Gill C, Welch A, Day K, Cassidy A, Khaw KT, et al. Comparison of dietary assessment methods in nutritional epidemiology: weighed records v. 24 h recalls, food-frequency questionnaires and estimated-diet records. Br J Nutr. 1994;72:619–643. doi: 10.1079/bjn19940064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briefel RR, Sempos CT, McDowell MA, Chien S, Alaimo K. Dietary methods research in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: underreporting of energy intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1203S–1209S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/65.4.1203S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox J. Applied Regression Analysis, Linear Models and Related Methods. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]