Abstract

The aim of this paper is to show the feasibility of the D-bar method for real-time 2-D EIT reconstructions. A fast implementation of the D-bar method for reconstructing conductivity changes on a 2-D chest-shaped domain is described. Cross-sectional difference images from the chest of a healthy human subject are presented, demonstrating what can be achieved in real time. The images constitute the first D-bar images from EIT data on a human subject collected on a pairwise current injection system.

1 Introduction

The generalized Laplace equation serves as a model for the electric field u(x) propagating in living tissue from a low frequency, low amplitude applied current density on the surface of a body. Denoting the conductivity by σ(x) and a bounded 2-D domain by Ω, the governing equation is

| (1) |

The ideal data is the Dirichlet-to-Neumann (DN) map, or voltage-to-current density map Λσ, defined by

| (2) |

where u is a solution to (1) and ν is the unit normal vector to the surface. Equation (1) serves as the governing equation for the electric field in electrical impedance tomography (EIT), and has a rich mathematical history dating back to the problems posed by Calderón [9]: (1) when does the inverse problem of determining σ from knowledge Λσ have a unique solution, and (2) how can it be determined? Historical reviews of the answers to these questions can be found in [5, 34], and the reader will find that most of the uniqueness proofs have utilized complex geometrical optics (CGO) solutions. Some have also been formulated as constructive proofs [36, 7, 2], and most of these include PDEs known as D-bar, or ∂̄, equations for the CGO solutions. These works have given rise to a new class of direct (noniterative) reconstruction algorithms known as D-bar methods.

D-bar equations are of the form ∂̄w = f, where f may depend on w, and the ∂̄ operator is defined by , where z = x + iy. The common threads in these methods are (1) a direct relationship between the CGO solutions and the unknown conductivity, (2) a nonlinear Fourier transform, also known as the scattering transform, providing a link between the data and the CGO solution, and (3) a D-bar equation to be solved for the CGO solutions with respect to a complex-frequency variable. These steps can be expressed in general terms by

To briefly review the history of D-bar methods for the inverse conductivity problem in dimension 2, we begin with the constructive global uniqueness proof for twice differentiable conductivities [36]. The fast method implemented in this paper is based on that work and subsequent theory and implementations including [37, 24, 33, 22, 23, 35, 12, 25]. The regularity conditions on the conductivity in [36] were relaxed to once-differentiable in [7], and a reconstruction method based on this work can be found in [26, 27, 28]. A nearly constructive proof for complex conductivities of the form σ+iωε with σ, ε ∈ W2,∞(Ω), with ω small was presented in [14], and a direct algorithm and implementations can be found in [19, 20, 21]. A non-constructive proof that applies to complex admittivities with no smallness assumption is found in [8]. Astala and Päivärinta provide a CGO-based constructive proof for real conductivities σ ∈ L∞(Ω), and numerical results related to this work can be found in [3, 4].

Electrical Impedance Tomography holds great promise as a bedside imaging tool for patients in intensive care. In the 2-D geometry, EIT is clinically useful for chest imaging. Acquisition and computation of time-dependent image sequences is known as functional Electrical Impedance Tomography (f-EIT). Functional conductivity images have been used for monitoring pulmonary perfusion [6, 17, 38], determining regional ventilation in the lungs [18, 16, 41], detecting extravascular lung water [31], and evaluating shifts in lung fluid in congestive heart failure patients [15]. Regional results have been validated with CT images [17, 18, 11, 38] and radionuclide scanning [30] in the presence of pathologies such as atelectasis, pleural effusion, and pneumothorax. However, the solution of the inverse problem in real-time poses a significant challenge. D-bar methods have been generally regarded as computationally intensive, but in this work, we show that through parallelization and careful optimization of the computational routines, a fast implementation is capable of providing real-time difference images from the pairwise current injection system at CSU.

In this work, we chose to optimize the D-bar method based on the uniqueness proof [36] and subsequent results and implementations [37, 35]. Many features of the fast implementation also apply to numerical solution methods of other D-bar reconstruction algorithms.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 contains a brief mathematical description of the D-bar method implemented here. Section 3 describes the fast implementation, parallelized in two different ways. Section 4 contains tables of runtimes and reconstructions on three different meshes from a set of data collected on a human subject. The final two sections contain conclusions and acknowledgments.

2 Background

We begin with an overview of the D-bar method implemented here, both for the reader’s convenience and to place the fast implementation in its mathematical context. For further details, see [36, 34].

The method begins with a transformation of the generalized Laplace equation with conductivity σ ∈ W2,p(Ω), for some p > 1, to the Schrödinger equation through the change of variables and , where the point z = (x, y) lies in Ω, a bounded, simply connected Lipschitz domain in ℝ2. This results in

| (3) |

Under the assumption that σ is constant in a neighborhood of the boundary of Ω, one can extend (3) to the whole plane, taking q = 0 outside Ω. Without loss of generality, we will assume σ ≡ 1 in a neighborhood of the boundary.

The existence of CGO solutions to (3) in the plane was established by Faddeev [13] in the context of quantum physics and shown by Nachman [36] to always exist for q of the form . Introducing the complex parameter k = k1 + ik2, and identifying the spatial variable z = x + iy with the corresponding point in the complex plane, the CGO solution ψ(z, k) satisfies [36]

| (4) |

| (5) |

The CGO solution closely related to ψ is μ(z, k), defined by μ(z, k) ≡ e−ikzψ(z, k). The conductivity can be obtained directly from μ or ψ through the formula [36]

| (6) |

and so the key steps in the method are to link the data Λσ to the function μ(z, k).

These links are provided by the scattering transform t(k) and the D-bar equation for μ. The scattering transform is defined by

| (7) |

and can be regarded as a nonlinear Fourier transform of q in light of the asymptotic behavior of ψ. The D-bar equation satisfied by μ is

| (8) |

where ez(k) ≡ ei(kz+k̄z̄). The scattering transform is related to the DN data through an equation that requires knowledge of ψ on the boundary of Ω:

| (9) |

Here Λ1 denotes the DN map corresponding to the homogeneous conductivity distribution σ ≡ 1. For the fast implementation, we utilize a linearized approximation to the scattering transform, denoted by texp, which is defined by replacing ψ|∂Ω by its asymptotic behavior:

| (10) |

This approximation was first introduced in [37] and was later studied in [24] where it was shown that the D-bar equation (8) with t(k) replaced by texp truncated to a disk of radius R in the k-plane has a unique solution which is smooth with respect to z, and the reconstruction is smooth and stable. Further, it was shown that no systematic artifacts are introduced when the method with texp is applied to piecewise continuous conductivities.

In summary, the mathematical steps of the algorithm implemented here are (1) compute texp(k) on a disk of radius R in the k-plane, (2) solve the D-bar equation (8) for each z in the region of interest on the disk |k| ≤ R, and (3) compute σ from (6).

3 Fast implementation

A fast implementation in Matlab on a 12 core Mac Pro with two 2.66 GHz 6 core Intel Xeon processors and Mat-lab’s Parallel Computing Toolbox is capable of computing reconstructions at less than the data acquisition rate of 16 frames/s, or 0.0625 s/frame, of the ACE 1 pairwise current injection EIT system at CSU [32]. This demonstrates the feasibility of CGO methods for real-time reconstructions.

In fact, we consider two options for the parallel computations. Ideally, in real-time reconstructions, data is collected, demodulated, and fed directly to the reconstruction algorithm, one frame at a time. In this configuration, only the loop over the z-values in the solution of the D-bar equation is trivially parallelizable. This accounts for over 95% of the computation time and can be used to obtain real-time reconstructions at a rate of 0.0621 s/frame on 7 cores on a coarse mesh of 562 elements, as reported in Section 4. This approach is structured as shown in Algorithm 1.

If a time delay of approximately one second is acceptable to the user, the algorithm can be parallelized over the frames. In this configuration, the data is collected and sent to a buffer from which multiple frames are sent to the reconstruction algorithm in batch. This approach results in an algorithm that is over 99% parallelizable, and the frame rate is even faster. As shown in Section 4, reconstructions were computed at a rate of 0.0215 s/frame on 64 cores or 0.0578 s/frame on 12 cores on a mesh of 1931 elements. The computational method for this approach is shown in Algorithm 2.

We now discuss the computational steps in detail, including numerical approximations of various functions and operations, and numerical solution of the D-bar equation. The computation of the matrix approximation to the DN map Λσ can be accomplished efficiently with inner products, as explained in [34]. For bipolar current patterns, as applied by ACE 1, the current pattern matrix is first transformed to an orthonormal basis { }, m = 1, …, N and l = 1, …, L, where N is the number of linearly independent current patterns, and L is the number of electrodes. The number of linearly independent current patterns depends on the particular choice of current pattern. For a bipolar current pattern that skips α electrodes between injection electrodes, N = L − gcd(L, α + 1). The voltages are transformed accordingly through the change-of-basis formula to the set denoted by { }. The discrete ND map Rσd for a given data set σd is approximated by

| (11) |

where A is the area of an electrode, sl is the arclength function s(θ) for the boundary evaluated at the angle θl corresponding to the center of the lth electrode, and Δθl = θl − θl−1 (where θ−1 = θL). Since the voltages sum to zero, we can then compute the matrix approximation Lσd to Λσd from Lσd = (Rσd)−1.

Algorithm 1.

Fast Parallelized D-bar Implementation for Matlab - Approach 1

| 1: | Setup Phase. Define parameters and compute functions independent of the dynamic DN data, including:

|

| 2: | Load a single frame of the measured data and demodulate |

| 3: | Compute matrix approximation to DN map, Lσd |

| 4: | Compute texp simultaneously for all k using vector operations |

| 5: | Compute the pointwise multiplication operator TR simultaneously for all z using vector operations |

| 6: | parfor all z in domain do |

| 7: | Solve D-bar equation for |

| 8: | |

| 9: | end parfor |

The scattering transform is computed for |k| ≤ R, where R is chosen empirically. While better reconstructions can often be obtained by considering a non-uniform truncation radius R, we consider a disk for simplicity. Non-uniform truncation would not result in appreciable loss of computational speed since over 95% of the computation time is spent in the solution of the D-bar equation. Since difference images from a reference frame are being reconstructed here, we implement the scattering transform , introduced in [23], in which the DN map for the conductivity σ = 1 is replaced by that of a reference frame Λσref. Then

| (12) |

The functions eikz and eik̄z̄ are expanded in the orthonormalized current pattern basis. The coefficients of the expansions of the functions eik̄z̄|∂Ω and eikz|∂Ω in the orthonormalized current pattern basis vectors are computed in the setup phase of the algorithm, and are denoted by c⃗(k) = [c1(k), … cL(k)]T and d⃗(k), respectively, where

Then, denoting the discrete inner product over two vectors u and v of length L by (u, v)L,

The fast evaluation of this formula is accomplished using inner products and vector operations.

A single grid and multigrid (2-grid) method were introduced in [29] for the fast computation of Lippmann-Schwinger type equations that arise in D-bar methods for EIT, closely based on the method of Vainikko [40]. The convolutions are computed as FFTs, and the solution of the resulting linear system by a matrix-free method, such as GMRES. For difference images, and in particular the data sets considered here, the frame-to-frame change in the data is sufficiently small that the method nearly always converges in one inner and one outer iteration of GMRES. In such cases, the 1-grid method is significantly faster than the 2-grid method described in [29].

Algorithm 2.

Fast Parallelized D-bar Implementation for Matlab - Approach 2

| 1: | Setup Phase. Define parameters and compute functions independent of the dynamic DN data, including:

|

| 2: | Load a batch of frames of the measured data and domain boundary points |

| 3: | Demodulate the reference data set and form the DN matrix for the reference data set Lσref |

| 4: | parfor all frames do |

| 5: | Demodulate the voltage data |

| 6: | Compute matrix approximation to DN map, Lσd |

| 7: | Compute texp simultaneously for all k using vector operations |

| 8: | Compute the pointwise multiplication operator TR simultaneously for all z using vector operations |

| 9: | for all z in domain do |

| 10: | Solve D-bar equation for |

| 11: | |

| 12: | end for |

| 13: | end parfor |

To apply this method, the D-bar equation (8) is formulated as an integral equation

| (13) |

To construct the computational k-grid, we define the square [−D, D]2 where D ≥ R, and we choose M = 2n for some positive integer n. The step-size for the k-grid is defined to be h = 2D/(M − 1), and the final size of the grid is then M × M. We further choose a computational z-grid of domain points, which need not be equally spaced. Equation (13) can be written compactly as the linear system

| (14) |

where TR is the pointwise multiplication operator defined by

| (15) |

and the action of the operator

is given by

is given by

| (16) |

In our fast implementation, we compute TR simultaneously for all z-values in the computational grid using vector operations, which in Matlab is more efficient than computing each TR separately inside the z-loop shown in step 6 of Algorithm 1 and step 9 of Algorithm 2. The action of the operator

can be approximated by

can be approximated by

| (17) |

where β(k) = (πk)−1 is the Green’s function for the ∂̄ operator, and 3 denotes element-wise multiplication. In Matlab, this operation can be performed efficiently using IFFTN and FFTN.

Once the solution to the D-bar equation has been found, the conductivity is given by . Note that the D-bar equation requires the solution of the linear system (14) for all k values in the computational grid, even though we are ultimately only interested in k = 0. It is also to be noted that this method allows for the reconstruction of σ pointwise in Ω, independent from any other z value, and so it is trivially parallelizable over the values in the computational z-grid.

For maximum computational speed, we invoked Matlab with the flag-singleCompThread, which limits Matlab to a single computational thread. This choice is compatible with the Parallel Computing Toolbox, and will restrict each parallel computation to a single core, which proved to be advantageous in the runtimes. Several choices of numerical solvers for the linear system (14) were compared for the fast implementation. Here, we use a customized GMRES, as opposed to the built-in Matlab routine, which greatly increases speed and computational efficiency. Specifically, we eliminated significant overhead due to repeated function calls and unnecessary option-checking and error-checking that is incurred when using Matlab’s GMRES routine. Moreover, each iteration of Matlab’s GMRES requires multiple function calls to the user-specified subroutine which computes the action of the linear operator [I −

TR(·̄)]. By embedding the GMRES code and its necessary subroutines directly within the D-bar code, these function calls were also eliminated.

TR(·̄)]. By embedding the GMRES code and its necessary subroutines directly within the D-bar code, these function calls were also eliminated.

4 Results and discussion

To demonstrate the feasibility of clinically useful real-time reconstructions using the D-bar method, we present reconstructions from data collected on the ACE 1 (Active Complex Electrode) EIT system at CSU. The ACE 1 system is a bipolar current injection system with 32 active electrodes operating at a user-specified frequency up to 125 kHz. Details of the hardware can be found in [32]. For the results presented here, difference images of perfusion in a cross-section of the chest of a healthy male subject sitting upright and holding his breath are presented. 360 frames of data were collected at 16 frames/s at 125 kHz and current amplitude 0.823 mA. One frame was chosen as a reference data set and 359 difference images were computed using the fast implementation in Section 3 on a uniform k-mesh of size 16 by 16 (256 elements) and a truncation radius of R = 3.8. Numerical experiments indicate that this size of k-mesh is sufficient, and also the minimal acceptable k-mesh of size 2m × 2m for these data sets. In the appendix is a comparison of reconstructions on k-meshes with m = 3, 4, 5, and 6, as well as error tables in the L2 and L∞ norms. All programming was in Matlab and utilized the Parallel Computing Toolbox for the parallel solution of the D-bar equation.

In Tables 1a and 2a we compare the performance for each version of the algorithm with various numbers of cores in parallel on a 12 core Mac Pro with two 2.66 GHz 6 core Intel Xeon processors using three different spatial grids consisting of a coarse mesh with 562 elements, a medium mesh with 1931 elements, and a fine mesh with 5,916 elements. In Tables 1b and 2b we compare the performance on a 64 core Linux system with four 2.3 GHz 16 core processors and 512 GB of RAM on the same three spatial grids.

Table 1a.

Runtimes in seconds for Algorithm 1 (parallelization over mesh points) over 359 frames on a 12 core Mac Pro with two 2.66 GHz 6 core Intel Xeon processors. Here, the loop runtimes refer to the runtime for the parallelized loop over z-values. The fastest per-frame runtime for each mesh has been highlighted.

| Coarse grid (562 z-values) | Medium grid (1931 z-values) | Fine grid (5,916 z-values) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Cores | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame |

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | 60.1527 | 57.1906 | 0.1676 | 200.1049 | 193.7054 | 0.5574 | 2449.0000 | 2397.3000 | 6.8217 |

| 2 | 49.0169 | 45.0331 | 0.1365 | 119.8318 | 113.8120 | 0.3338 | 1450.8000 | 1384.0000 | 4.0412 |

| 4 | 26.2268 | 23.1675 | 0.0731 | 69.2834 | 62.6818 | 0.1930 | 793.1958 | 719.3565 | 2.2095 |

| 6 | 23.3147 | 20.3212 | 0.0649 | 55.8466 | 47.2439 | 0.1556 | 581.6291 | 508.4273 | 1.6201 |

| 7 | 22.2798 | 19.2730 | 0.0621 | 49.0180 | 41.6290 | 0.1365 | 516.3475 | 442.8791 | 1.4383 |

| 8 | 23.2349 | 20.2471 | 0.0647 | 46.8985 | 38.7851 | 0.1306 | 465.2694 | 393.8668 | 1.2960 |

| 9 | 25.0864 | 22.0817 | 0.0699 | 45.4834 | 37.2894 | 0.1267 | 423.6890 | 352.4819 | 1.1802 |

| 10 | 26.6466 | 23.6232 | 0.0742 | 44.8317 | 36.8733 | 0.1249 | 393.7915 | 322.4939 | 1.0969 |

| 11 | 26.3834 | 23.3987 | 0.0735 | 44.8993 | 36.9119 | 0.1251 | 371.5604 | 300.3748 | 1.0350 |

| 12 | 28.2897 | 25.3129 | 0.0788 | 46.2567 | 38.1605 | 0.1288 | 355.7963 | 283.7342 | 0.9911 |

Table 2a.

Runtimes in seconds for Algorithm 2 (parallelization over frames) over 359 frames on a 12 core Mac Pro with two 2.66 GHz 6 core Intel Xeon processors. Here, the loop runtimes refer to the runtime for the parallelized loop over the frames. The fastest per-frame runtime for each mesh has been highlighted.

| Coarse grid (562 z-values) | Medium grid (1931 z-values) | Fine grid (5,916 z-values) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Cores | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame |

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | 63.5468 | 63.4370 | 0.1770 | 206.1180 | 205.9474 | 0.5741 | 623.0107 | 622.7078 | 1.7354 |

| 2 | 33.5405 | 33.4232 | 0.0934 | 106.1961 | 106.0467 | 0.2958 | 326.5889 | 326.2849 | 0.9097 |

| 4 | 17.5768 | 17.4568 | 0.0490 | 55.9864 | 55.8287 | 0.1560 | 173.0110 | 172.6940 | 0.4819 |

| 8 | 9.5713 | 9.4459 | 0.0267 | 29.8543 | 29.7101 | 0.0832 | 89.9303 | 89.6408 | 0.2505 |

| 11 | 7.0793 | 6.9545 | 0.0197 | 21.2018 | 21.0424 | 0.0591 | 63.5926 | 63.2956 | 0.1771 |

| 12 | 6.7303 | 6.6036 | 0.0187 | 20.7440 | 20.5766 | 0.0578 | 61.7965 | 61.4933 | 0.1721 |

Table 1b.

Runtimes in seconds for Algorithm 1 (parallelization over mesh points) over 359 frames on a 64 core Linux system with four 2.3 GHz 16 core processors and 512 GB of RAM. Here, the loop runtimes refer to the runtime for the parallelized loop over the frames. The fastest per-frame runtime for each mesh has been highlighted.

| Coarse grid (562 z-values) | Medium grid (1931 z-values) | Fine grid (5,916 z-values) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Cores | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame |

|

| |||||||||

| 1 | 70.6320 | 66.6039 | 0.1967 | 239.3496 | 231.0972 | 0.6667 | 767.5243 | 742.7878 | 2.1380 |

| 2 | 41.4227 | 38.4427 | 0.1154 | 146.6424 | 137.5511 | 0.4085 | 460.4769 | 435.7931 | 1.2827 |

| 4 | 33.5734 | 28.9639 | 0.0935 | 85.1865 | 75.0827 | 0.2373 | 248.8144 | 229.7575 | 0.6931 |

| 6 | 29.3667 | 24.9876 | 0.0818 | 62.8336 | 55.3416 | 0.1750 | 184.0372 | 164.8297 | 0.5126 |

| 7 | 28.1477 | 24.1555 | 0.0784 | 60.9286 | 51.3155 | 0.1697 | 159.8174 | 142.7302 | 0.4452 |

| 8 | 28.0048 | 24.1189 | 0.0780 | 56.1551 | 46.3121 | 0.1564 | 150.0559 | 127.9969 | 0.4180 |

| 11 | 31.5985 | 26.9765 | 0.0880 | 50.0699 | 42.1989 | 0.1395 | 121.6363 | 99.6636 | 0.3388 |

| 12 | 34.3986 | 30.1875 | 0.0958 | 53.0852 | 40.8174 | 0.1479 | 109.3473 | 91.8146 | 0.3046 |

| 16 | 47.7978 | 43.7131 | 0.1331 | 59.5714 | 50.6782 | 0.1659 | 111.0096 | 83.2492 | 0.3092 |

| 24 | 77.3859 | 72.0929 | 0.2156 | 89.5173 | 80.3598 | 0.2494 | 129.2778 | 104.2357 | 0.3601 |

| 32 | 120.9989 | 116.1762 | 0.3370 | 125.9324 | 115.8191 | 0.3508 | 156.2232 | 131.1057 | 0.4352 |

Table 2b.

Runtimes in seconds for Algorithm 2 (parallelization over frames) over 359 frames on a 64 core Linux system with four 2.3 GHz 16 core processors and 512 GB of RAM. Here, the loop runtimes refer to the runtime for the parallelized loop over the frames. The fastest per-frame runtime for each mesh has been highlighted.

| Coarse grid (562 z-values) | Medium grid (1931 z-values) | Fine grid (5,916 z-values) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Cores | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame |

| 1 | 83.0041 | 82.8420 | 0.2312 | 261.7762 | 261.5257 | 0.7292 | 837.1351 | 836.5582 | 2.3319 |

| 2 | 49.8535 | 49.5505 | 0.1389 | 145.1565 | 145.9066 | 0.4043 | 510.6861 | 510.2197 | 1.4225 |

| 4 | 25.3656 | 25.1796 | 0.0707 | 80.8684 | 80.6215 | 0.2253 | 262.7161 | 262.2612 | 0.7318 |

| 8 | 13.8435 | 13.6768 | 0.0386 | 42.7368 | 42.4592 | 0.1190 | 106.2459 | 105.8588 | 0.2959 |

| 12 | 9.3821 | 9.1925 | 0.0261 | 29.1641 | 28.8975 | 0.0812 | 70.7996 | 70.4057 | 0.1972 |

| 16 | 7.6005 | 7.3360 | 0.0212 | 26.5531 | 26.3019 | 0.0740 | 54.4559 | 54.0610 | 0.1517 |

| 24 | 5.4611 | 5.2730 | 0.0152 | 16.4534 | 16.1881 | 0.0458 | 38.2854 | 37.8909 | 0.1066 |

| 32 | 4.3561 | 4.1731 | 0.0121 | 13.9393 | 13.6828 | 0.0388 | 30.0064 | 29.5878 | 0.0836 |

| 48 | 2.9294 | 2.7678 | 0.0082 | 8.5636 | 8.3324 | 0.0239 | 24.9113 | 24.4925 | 0.0694 |

| 60 | 2.7924 | 2.6435 | 0.0078 | 7.7249 | 7.4911 | 0.0215 | 22.1673 | 21.7229 | 0.0617 |

| 64 | 2.7781 | 2.6219 | 0.0077 | 7.7157 | 7.4769 | 0.0215 | 21.9644 | 21.5439 | 0.0612 |

Comparing all four tables, it is immediately clear that all runtimes utilizing the same number of cores were faster on the Mac Pro than on the Linux system, which is likely due in part to the difference in processor speed. It is also evident that while adding increasing numbers of parallel cores continues to improve runtimes for Algorithm 2 in Table 2, the runtimes for Algorithm 1 in Table 1 reach maximum efficiency with a smaller number of cores, after which adding additional parallel cores actually slows the computation. This optimum number of cores increases as the z-mesh size increases.

It is well-known in parallel computing that the efficiency gained by adding additional parallel processors follows a “law of diminishing returns,” embodied by Amdahl’s law [1], which states that the maximum theoretical speedup s obtainable when using n processors in parallel is given by

| (18) |

where p is the proportion of the program that is parallelizable. One can see that as we increase n to ∞, the maximum theoretical speedup goes to 1/(1 − p). To compute the actual speedup obtained using n processors, we use sactual(n) = T(1)/T(n), where T(n) is the runtime with n cores in parallel.

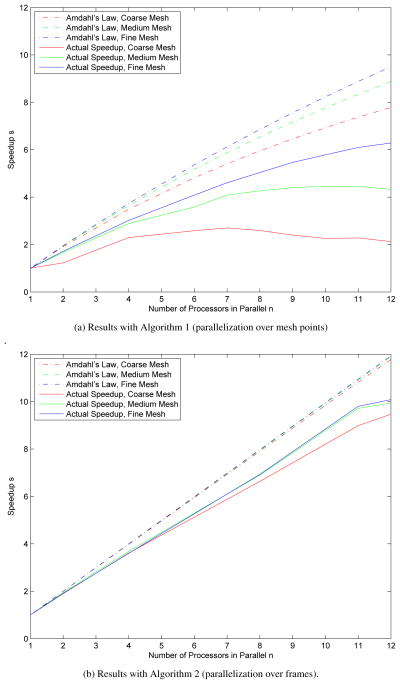

In Figure 1, the actual speedups obtained on the Mac Pro using both versions of the parallel algorithm are shown along with the theoretical maximum speedups predicted by (18). One can see that the results obtained using Algorithm 2 are much closer to Amdahl’s ideal values than the results obtained using Algorithm 1. We can also see that the larger the size of the z-mesh, the more efficient the parallelization becomes; this is predicted by (18) since increasing the number of elements in the z-mesh also increases p, the parallelizable portion of the program. In Figure 2 the same plots are included for the 64 core Linux system. It is evident that the additional cores do not provide speedup for Algorithm 1, and the divergence from the theoretically predicted speedup by Amdahl’s Law increases with the number of cores, but Amdahl’s Law also predicts the leveling off of speedup at around 20 to 25 cores; in fact, this happens at around 10 to 12 cores for parallelization over mesh values (Algorithm 1). However, for Algorithm 2, the speedup continues for all 64 cores, although it is clearly starting to level out at around 60 cores.

Figure 1.

A comparison of Amdahl’s law for maximum theoretical speedup (dashed lines) when using multiple cores with actual speedup obtained on a 12 core Mac Pro with two 2.66 GHz 6 core Intel Xeon processors (solid lines) using Algorithms 1 and 2.

Figure 2.

A comparison of Amdahl’s law for maximum theoretical speedup (dashed lines) when using multiple cores with actual speedup obtained on 64 core Linux system with four 2.3 GHz 16 core processors and 512 GB of RAM (solid lines) using Algorithms 1 and 2.

Figure 3 contains four frames in the reconstruction of the human chest data displayed in the three z-meshes to illustrate the resolution provided by these mesh choices. The figure depicts changes due to perfusion. The heart is at the top, and red represents high conductivity and blue low conductivity. The images are displayed on the same scale. While the topmost mesh is quite coarse, the lungs and heart are clearly visible, and changes are evident. The medium mesh is significantly better, and probably provides the best compromise for real-time imaging, but this implementation comes with the price of an approximately 1 second delay. The very fine mesh is included to illustrate highly desirable spatial resolution and the associated runtimes, given in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 3.

Reconstructions on the three z-meshes timed in this work of four frames in the sequence of 360 frames showing changes due to perfusion in the chest of a healthy human subject. The heart is at the top, and red represents high conductivity and blue low conductivity with respect to the reference frame. The images are displayed on the same scale.

From the clinical perspective, difference images are sufficient for some applications, such as real-time detection of a pneumothorax or atelectasis. For other applications, such as distinguishing between blood, water, and mucus in the lung, absolute images may be required, which may require longer computation times. Some applications may also require finer spatial resolution than that presented here. However, the data is preserved for off-line or delayed reconstruction, and improvements such as the use of additional cores in parallel, faster FFTs, and faster processors are likely to yield improved runtimes in the future.

5 Conclusions

The results presented here show for the first time the D-bar method applied to human chest data collected on a pairwise current injection system. Conductivity changes due to perfusion are clearly visible in the images. The fast implementation demonstrates the clinical potential of the D-bar algorithm as a reconstruction algorithm for real-time bedside imaging.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number 1R21EB016869-01A1 from the National Institute Of Biomedical Imaging And Bioengineering. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institute Of Biomedical Imaging And Bioengineering or the National Institutes of Health.

7 Appendix

Numerical computations were performed to study the effect of the choice of m when solving the D-bar equation on a k-mesh of size 2m × 2m. Computations were performed with m = 3, 4, 5, and 6. Very little change is evident in the reconstruction between reconstructions from k-meshes of sizes m = 4, 5, and 6; see Figure 4. Choosing the image with m = 6, that is a 64 × 64 k-mesh as “truth”, relative errors were computed in the L2 and L∞ norms for each frame. This choice of k-mesh is justifiable as a reference in the relative error computations because no further improvement is visibly seen by choosing a still finer mesh, and the lengths of computation time then become quite long for m = 7 and larger. In Table 3 the mean relative error, the maximum relative error, and the standard deviation over the 359 frames is reported. In Table 4 the effect of the size of the k-mesh on the runtime for Algorithm 2 is provided. From the table of relative errors and reconstructions in Figure 4, it is evident that at least for this data set, the 16 × 16 k-mesh is sufficient. For general difference image reconstructions, we would also expect this to be sufficient, but recommend testing this parameter first.

Figure 4.

Reconstructions of the rightmost frame in Figure 3 computed by solving the D-bar equation on a k-grid of size 2m × 2m with m = 3, 4, 5, and 6, left to right. The images are displayed on the same scale.

Table 3.

Comparison of the mean, maximum, and standard deviation over the 359 frames in the relative errors in the reconstructions computed by solving the D-bar equation on three sizes of k-mesh. The relative errors for each frame were computed by treating the reconstruction on a k-mesh of size 64 × 64 as truth.

| Relative Errors in L∞ norm | Relative Errors in L2 norm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k-Mesh Size | Mean Error | Std Dev. | Max Error | Mean Error | Std Dev. | Max Error |

| 8 × 8 | 2.29E-03 | 5.27E-04 | 4.13E-03 | 8.93E-04 | 1.76E-04 | 1.48E-03 |

| 16 × 16 | 7.24E-04 | 1.36E-04 | 1.20E-03 | 3.08E-04 | 6.12E-05 | 5.16E-04 |

| 32 × 32 | 2.43E-04 | 5.65E-05 | 4.21E-04 | 1.01E-04 | 2.15E-05 | 1.74E-04 |

Table 4.

Runtimes in seconds for Algorithm 2 parallelized over 12 cores on a Mac Pro on the coarse and medium z-meshes, for various k-mesh sizes. The loop runtimes refer to the runtime for the parallelized loop over the frames. These results show that we can still easily achieve real-time results on the 32×32 k-mesh with an appropriately coarse z-mesh.

| Coarse grid (562 z-values) | Medium grid (1931 z-values) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k-Mesh Size | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame | Total runtime (s) | Loop runtime (s) | s/frame |

| 8 × 8 | 4.7477 | 4.6552 | 0.0132 | 14.1798 | 14.0664 | 0.0395 |

| 16 × 16 | 6.7303 | 6.6036 | 0.0187 | 20.7440 | 20.5766 | 0.0578 |

| 32 × 32 | 16.1720 | 15.9394 | 0.0450 | 51.3855 | 51.0080 | 0.1431 |

| 64 × 64 | 68.8607 | 68.1446 | 0.1918 | 253.6598 | 252.1337 | 0.7066 |

References

- 1.Amdahl GM. Validity of the single-processor approach to achieving large scale computing capabilities. AFIPS Conference Proceedings. 1967;30:483–485. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Astala K, Päivärinta L. Calderón’s inverse conductivity problem in the plane. Annals of Math. 2006;163:265–99. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Astala K, Mueller JL, Päivärinta L, Siltanen S. Numerical computation of complex geometrical optics solutions to the conductivity equation. Applied and Computational Harmonic Analysis. 2010;29:2–17. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Astala K, Mueller JL, Perämäki A, Päivärinta L, Siltanen S. Direct electrical impedance tomography for nonsmooth conductivities. Inverse Problems and Imaging. 2011;5:531–549. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borcea L. Electrical impedance tomography. Inverse Problems. 2002;18:99–136. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown BH, Barber DC, Morice AH, Leathard A, Sinton A. Cardiac and respiratory related electrical impedance changes in the human thorax. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1994;41:729–734. doi: 10.1109/10.310088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown RM, Uhlmann G. Uniqueness in the inverse conductivity problem for nonsmooth conductivities in two dimensions. Comm Partial Differential Equations. 1997;22:1009–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bukhgeim AL. Recovering a potential from Cauchy data in the two-dimensional case. Inverse Problems. 2007;15:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calderón AP. On an inverse boundary value problem, in “Seminar on Numerical Analysis and its Applications to Continuum Physics”. Soc Brasileira de Matemàtica. 1980:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costa ELV, Chaves CN, Gomes S, Beraldo MA, Volpe MS, Tucci MR, Schettino IAL, Bohm SH, Carvalho CRR, Tanaka H, Lima RG, Amato MBP. Real-time detection of pneumothorax using electrical impedance tomography. Crit Care Med. 2006;36:1230–1238. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31816a0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa ELV, Gonzalez Lima R, Amato MBP. Electrical impedance tomography. Current Opinion in Crit Care. 2009;15:18–24. doi: 10.1097/mcc.0b013e3283220e8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeAngelo M, Mueller JL. D-bar reconstructions of human chest and tank data using an improved approximation to the scattering transform. Physiol Meas. 2010;31:221–232. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/31/2/008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Faddeev LD. Increasing solutions of the Schrödinger equation. Sov Phys Dokl. 1966;10:1033–1035. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francini E. Recovering a complex coefficient in a planar domain from the Dirichlet-to-Neumann map. Inverse Problems. 2000;6:107–119. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freimark D, Arad M, Sokolover R, Zlochiver S, Abboud S. Monitoring lung fluid content in CHF patients under intravenous diuretics treatment using bio-impedance measurements. Physiol Meas. 2007;28:S269–S277. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/28/7/S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frerichs I, Hinz J, Herrmann P, Weisser G, Hahn G, Dudykevych T, Quintel M, Hellige G. Detection of local lung air content by electrical impedance tomography compared with electron beam CT. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:660–666. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00081.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frerichs I, Hinz J, Herrmann P, Weisser G, Hahn G, Quintel M, Hellige G. Regional lung perfusion as determined by electrical impedance tomography in comparison with electron beam CT imaging. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2002;21:646–652. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2002.800585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frerichs I, Schmitz G, Pulletz S, Schädler D, Zick G, Scholz J, Weiler N. Reproducibility of regional lung ventilation distribution determined by electrical impedance tomography during mechanical ventilation. Physiol Meas. 2007;28:261–267. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/28/7/S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton SJ, Mueller JL. Direct EIT reconstructions of complex conductivities on a chest-shaped domain in 2-D. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2013;32:757–769. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2012.2237389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton SJ, Herrera CNL, Mueller JL, Von Herrmann A. A direct D-bar reconstruction algorithm for recovering a complex conductivity in 2-D. Inverse Problems. 2012;28:095005. doi: 10.1088/0266-5611/28/9/095005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrera CNL, Vallejo MFM, Mueller JL, Lima R. Direct 2-D reconstructions of conductivity and permittivity from EIT data on a human chest. 2014 doi: 10.1109/TMI.2014.2354333. in review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isaacson D, Mueller JL, Newell JC, Siltanen S. Reconstructions of chest phantoms by the D-bar method for electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Trans Med Im. 2004;23:821–828. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2004.827482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isaacson D, Mueller JL, Newell JC, Siltanen S. Imaging cardiac activity by the D-bar method for electrical impedance tomography. Physiol Meas. 2006;27:S43–S50. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/27/5/S04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knudsen K, Lassas M, Mueller JL, Siltanen S. D-bar method for electrical impedance tomography with discontinuous conductivities. SIAM J Appl Math. 2007;67:893–913. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Knudsen K, Lassas M, Mueller JL, Siltanen S. Regularized D-bar method for the inverse conductivity problem. Inverse Problems and Imaging. 2009;3:599–624. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knudsen K. PhD thesis. Department of Mathematical Sciences, Aalborg University; Denmark: 2002. On the Inverse Conductivity Problem. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knudsen K. A new direct method for reconstructing isotropic conductivities in the plane. Physiol Meas. 2003;24:391–401. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/24/2/351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knudsen K, Tamasan A. Reconstruction of less regular conductivities in the plane. Comm Partial Differential Equations. 2004;29:361–381. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knudsen K, Mueller JL, Siltanen S. Numerical solution method for the dbar-equation in the plane. J Comp Phys. 2004;198:500–517. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunst PW, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Hoekstra OS, Postmus PE, de Vries PM. Ventilation and perfusion imaging by electrical impedance tomography: a comparison with radionuclide scanning. Physiol Meas. 1998;19:481–490. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/19/4/003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunst PW, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Raaijmakers E, Bakker J, Groeneveld AB, Postmus PE, de Vries PM. Electrical impedance tomography in the assessment of extravascular lung water in noncardiogenic acute respiratory failure. Chest. 1999;116:1695–1702. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mellenthin M, de Camargo EL, de Moura F, Santos T, Mueller JL, Lima RG. Complex Voltage Measurements With Active Electrodes in Electrical Impedance Tomography. in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mueller JL, Siltanen S. Direct reconstructions of conductivities from boundary measurements. SIAM J Sci Comp. 2003;24:1232–1266. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mueller JL, Siltanen S. Linear and nonlinear inverse problems with practical applications. SIAM. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murphy EK, Mueller JL. Effect of domain-shape modeling and measurement errors on the 2-D D-bar method for electrical impedance tomography. IEEE Trans Med Im. 2009;28:1576–1584. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2021611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nachman A. Global uniqueness for a two-dimensional inverse boundary value problem. Annals of Math. 1996;143:71–96. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siltanen S, Mueller JL, Isaacson D. An implementation of the reconstruction algorithm of A. Nachman for the 2D inverse conductivity problem. Inverse Problems. 2000;16:681–699. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smit H, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Marcus JT, Boonstra A, de Vries PM, Postmus PE. Determinants of pulmonary perfusion measured by electrical impedance tomography. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2004;92:45–49. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saad Y, Schultz MH. GMRES: a generalized minimal residual algorithm for solving nonsymmetric linear systems. SIAM J Sci Stat Comp. 1986;7:856–869. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vainikko G. Fast solvers of the Lippmann-Schwinger equation. In: Gilbert RP, Kajiwara J, Xu YS, editors. Direct and Inverse Problems of Mathematical Physics. Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Victorino JA, Borges JB, Okamoto VN, Matos GFJ, Tucci MR, Caramez MPR, Tanaka H, Santos DCB, Barbas CSV, Carvalho CRR, Amato MBP. Imbalances in regional lung ventilation: a validation study on electrical impedance tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:791–800. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-133OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vonk Noordegraaf A, Faes TJC, Janse A, Marcus JT, Bronzwaer JGF, Postmus PE, de Vries M. Noninvasive assessment of right ventricular diastolic function by electrical impedance tomography. Chest. 1997;111:1222–1228. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.5.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vonk Noordegraaf A, Kunst PW, Janse A, Marcus JT, Postmus PE, Faes TJ, de Vries PM. Pulmonary perfusion measured by means of electrical impedance tomography. J Electron Imaging. 1998;10:608–619. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/19/2/013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]