Abstract

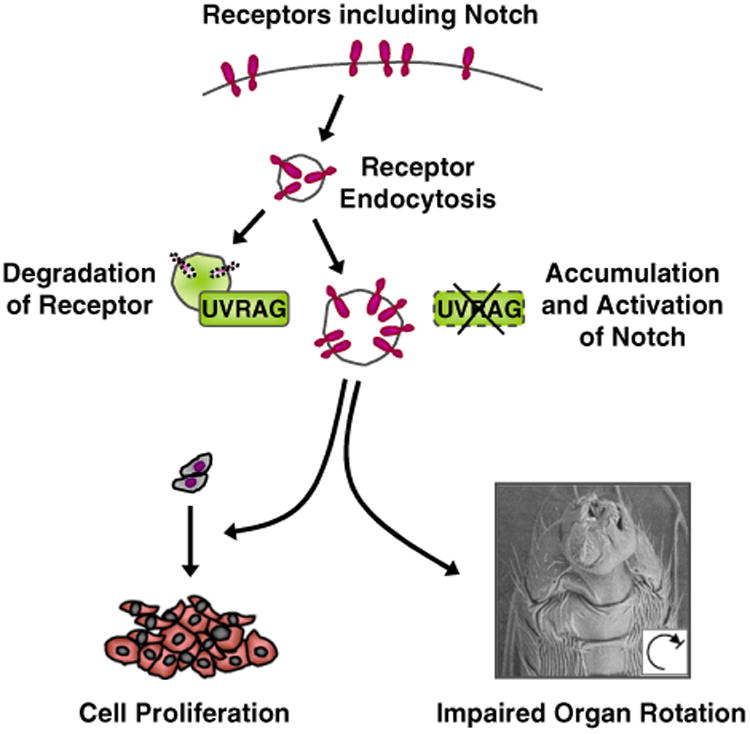

Heterotaxy characterized by abnormal left–right body asymmetry causes diverse congenital anomalies. Organ rotation is a crucial developmental process to establish the left–right patterning during animal development. However, the molecular basis of how organ rotation is regulated is poorly understood. Here we report that Drosophila UV-resistance associated gene (UVRAG), a tumor suppressor that regulates autophagy and endocytosis, plays unexpected roles in controlling organ rotation. Loss-of-function mutants of UVRAG show seriously impaired organ rotation phenotypes, which are associated with defects in endocytic trafficking rather than autophagy. Blunted endocytic degradation by UVRAG deficiency causes endosomal accumulation of Notch, resulting in abnormally enhanced Notch activity. Knockdown of Notch itself or expression of a dominant negative form of Notch transcriptional co-activator Mastermind is sufficient to rescue the rotation defect in UVRAG mutants. Consistently, UVRAG-mutated heterotaxy patient cells also display highly increased Notch protein levels. These results suggest evolutionarily conserved roles of UVRAG in organ rotation by regulating Notch endocytic degradation.

Keywords: UVRAG, Organ rotation, Vesicle trafficking, Notch endocytosis, Left – right body asymmetry

Introduction

Internal organs such as heart, liver and gut undergo a directional rotation process to establish left–right body asymmetry during animal development (Palmer, 2004). For example, in humans, the heart undergoes dextral rotation to be ultimately located in the left side of the body. Heterotaxy, which involves non-rotation, reverse rotation and mal-rotation of internal organs, leads to various syndromes and pathologies including asplenia, polysplenia, congenital heart defects and early fetal death, indicating importance of the rotation process in organ development and function (Belmont et al., 2004; Bisgrove et al., 2003).

The organ rotation around a longitudinal body axis is an evolutionarily conserved process from worms to humans (Speder et al., 2007). In Drosophila melanogaster, the looping of embryonic gut and 360° dextral rotation of adult male genitalia with spermiduct looping are the two representative organ rotation programs (Coutelis et al., 2008; Okumura et al., 2008). Previous studies in Drosophila have discovered several genes involved in organ rotation such as Fasciclin II (Adam et al., 2003), JNK (Macias et al., 2004; McEwen and Peifer, 2005; Taniguchi et al., 2007), Myosin ID (Hozumi et al., 2006; Speder et al., 2006) and single-minded (Maeda et al., 2007). For instance, in the mutants of Fasciclin II that regulates juvenile hormone metabolism in central nervous system, the genitalia rotation is incomplete while the direction of rotation is normal (Adam et al., 2003). On the other hand, mutations of the actin-based motor protein Myosin ID lead to complete reversion of the looping direction (Hozumi et al., 2006; Speder et al., 2006). The molecular mechanisms of how all these seemingly divergent genes orchestrate organ rotation remain to be elucidated.

UVRAG was initially identified for its complementary effect on UV sensitivity in xeroderma pigmentosum cells (Perelman et al., 1997). Genetic association studies have shown that the human chromosomal region containing UVRAG is closely associated with the pathogenesis of various human cancers and heterotaxy syndromes (Bekri et al., 1997; Goi et al., 2003; Iida et al., 2000; Ionov et al., 2004; Kosaki and Casey, 1998). Recent biochemical and cell biological studies in mammalian cells have demonstrated that UVRAG interacts with Atg6 and class C vacuolar protein sorting complexes, thereby regulating both autophagy and vesicle trafficking (Itakura et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2006, 2008). Despite these advances inour understanding of UVRAG functions at the molecular level, physiological and developmental roles of UVRAG have not been investigated yet.

Vesicle trafficking controls a variety of intracellular processes including protein turnover and protein targeting to different organelles. In particular, endocytic trafficking pathway modulates localization of membrane signaling proteins to specific intracellular vesicle compartments as well as their lysosomal degradation to achieve the fine tuning of extracellular signals and cell homeostasis (Deretic, 2005; Gonzalez-Gaitan, 2003; Seto et al., 2002; Sorkin and von Zastrow, 2009). In fact, several loss-of-function mutants of endocytic trafficking genes have been shown to exhibit dysregulated cell survival and proliferation (Gonzalez-Gaitan and Stenmark, 2003; Herz and Bergmann, 2009; Vaccari and Bilder, 2009). Recently, endocytic trafficking has also emerged as a crucial regulatory mechanism for animal body development. Expression levels of numerous endocytic trafficking genes are dynamically altered during Drosophila metamorphosis (Lee et al., 2003; Li and White, 2003; Martin et al., 2007), and mutations of endocytic trafficking genes cause severe developmental defects in mammals (Cheng et al., 2006; Dell'Angelica, 2009; Sato et al., 2007). However, it is still unknown whether endocytic trafficking plays important roles in organ rotation.

In this study, we have generated Drosophila UVRAG loss-of-function mutants and identified unexpected roles of UVRAG in regulating organ rotation. We found that UVRAG is important for organ rotation by regulating receptor endocytosis and subsequent degradation rather than autophagy induction. Moreover, our results show that Notch is the key downstream target regulated by UVRAG in both Drosophila and human cells, implicating an evolutionarily conserved role of UVRAG in Notch signaling regulation and organ rotation.

Results

Identification of UVRAG as a novel cell growth regulator

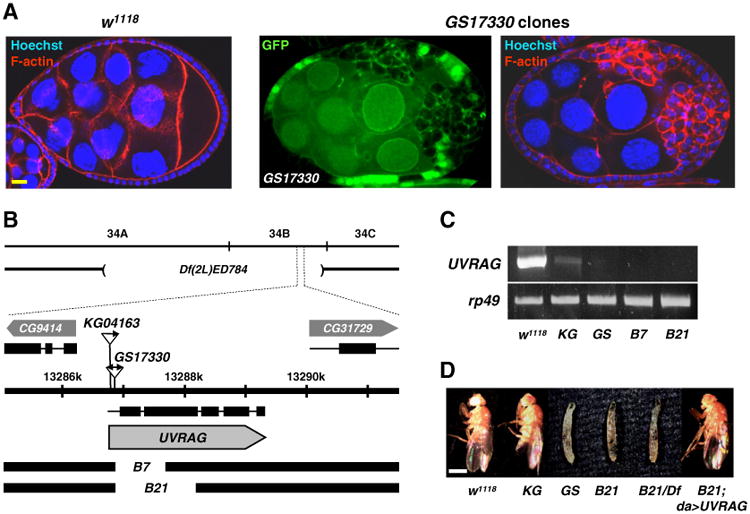

We performed a Drosophila genetic screen using P-element lines that show homozygous lethality to identify novel cell growth regulators. By generating mosaic clones (Xu and Rubin, 1993) of P-element lines in adult ovaries, we identified GS17330 allele which showed highly increased number of follicle cells. In contrast to the typical cuboidal and monolayered wild type follicle cells (Fig. 1A, left), GFP-negative GS17330 mosaic clones were mostly round-shaped and multilayered (Fig. 1A, right), suggesting that the GS17330 allele affects a potential cell growth regulator gene (Bilder et al., 2000; Goode and Perrimon, 1997; Tepass et al., 2001).

Fig. 1.

UVRAG is identified as a novel cell growth regulator. (A) Wild type (w1118) ovary (left) and GS17330 clone-containing ovary (right) were stained with TRITC-phalloidin (F-actin) and Hoechst 33258 (blue). Absence of GFP marks GS17330 clones. (B) A schematic representation of the UVRAG genomic locus and deletion regions of UVRAGB7(B7) and UVRAGB21(B21). (C) RT-PCR analyses of UVRAG in wild type, UVRAG P-element insertion [UVRAGKG (KG) and UVRAGGS (GS)] and deletion (B7 and B21) mutants. rp49 was used as a loading control. (D) The lethality of UVRAG null mutants was rescued by transgenic expression of UVRAG.Df,Df(2L)ED784. Scale bars: yellow, 10 μm; white, 0.5 mm. Genotype: (A) Right: hsFLP/+; GS17330 FRT40A/FRT40A UbiGFP.

The P-element of GS17330 was inserted in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of a previously uncharacterized gene, CG6116 (FlyBase ID; FBgn0032499) (Fig. 1B). BLAST search analyses indicated that CG6116 is a Drosophila ortholog of UVRAG (Supplemental Fig. S1). Using imprecise excision of the P-element of another UVRAG mutant KG04163, we generated two deletion mutants of UVRAG, UVRAGB7 and UVRAGB21 (Fig. 1B), in which UVRAG transcripts were not detected by RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). The deletion mutants and their trans-heterozygotes combined with a deficiency line covering UVRAG were all larval lethal (Fig. 1D), but the lethality was rescued by transgenic expression of UVRAG under ubiquitous daughterless (da)-Gal4 driver (Fig. 1D). Similar to the GS17330 clones (Fig. 1A), UVRAG null mutant clones also showed active cell proliferation (Supplemental Fig. S2). These results demonstrate that Drosophila UVRAG is required for normal fly development and cell growth regulation.

UVRAG is required for organ rotation

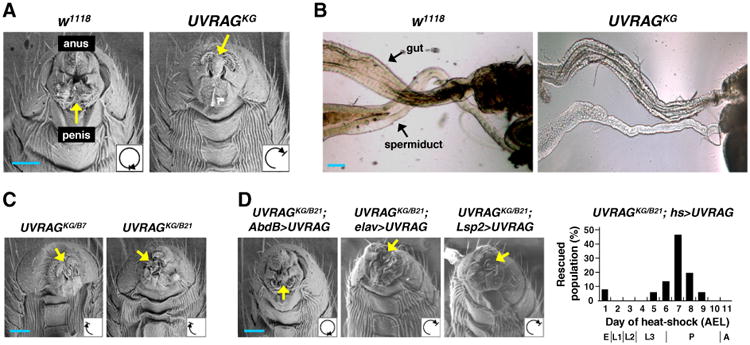

Since UVRAG null mutant is early larval lethal, we employed an adult-viable UVRAG hypomorphic allele KG04163 (Figs. 1B–D) to investigate the roles of UVRAG in later development. Strikingly, compared to wild type, ∼50% of KG04163 males showed abnormal genitalia orientation (Fig. 2A and Table 1). In wild type flies, genitalia undergoes a complete 360° dextral rotation and induces looping of the spermiduct around the gut (Figs. 2A and B, left panels), which is comparable to the directional looping of internal organs in vertebrates (Speder et al., 2007). The spermiduct of KG04163 did not coil around the gut (Fig. 2B, right), suggesting that the failure in genitalia rotation leadsto impaired gut looping. The incomplete rotation phenotype was severed by lowering UVRAG gene dosage, as shown by a much lower rotation degree of KG04163 trans-heterozygotes with UVRAG null alleles (UVRAGKG/B7 and UVRAGKG/B21) compared to that of KG04163 homozygotes (Fig. 2C compared to Fig. 2A and Table 1). However, the direction of rotation in UVRAG mutants was constantly dextral (Fig. 2 and data not shown), indicating that UVRAG is not involved in the determination of organ rotation direction.

Fig. 2.

UVRAG is required for the adult organ rotation. (A, C, D) Ventral side views of adult male genitalia were visualized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM; posterior is upward). Yellow arrows indicate the location of penis. A schematic diagram for the direction and extent of genitalia rotation is indicated by the looping arrow (lower right inlets). The effect of tissue-specific or developmental stage-specific expression of transgenic UVRAG on the UVRAGKG/B21 rotation phenotype was visualized by SEM (D, left three panels) or quantified throughout the development (D, graph in the right panel): embryo (E), first, second and third instar larva (L1, L2, L3), pupa (P) and adult (A). N >50 male flies for each genotype. AEL, after egg laying. (B) Dissected adult abdominal organs were visualized by light microscopy. Wild type shows the rightward looping of the spermiduct around the gut (left), while UVRAG mutant displays impaired looping (right). The strongest phenotype is shown. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Table 1.

Quantification of genitalia rotation phenotypes. Numbers show the percentage of male flies with the indicated genitalia rotation phenotypes: =360° (normal), complete rotation; ≥180° (mild phenotype) and <180° (severe phenotype), incomplete rotation. The direction of rotation is all dextral. N>50 for each genotype. Interestingly, the presence of AbdB-Gal4 itself enhances the UVRAG mutant phenotype. The reason for this is unknown. NotchICD, Constitutive active form; NotchECN, Dominant negative form for receptor interaction activity; Mastermind-N, Dominant negative form for transcription co-activator activity

| = 360° | ≥180° | <180° | |

|---|---|---|---|

| w1118 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| UVRAGKG04163 | 50 | 50 | 0 |

| UVRAGKG04163/B7 | 26 | 36 | 38 |

| UVRAGKG04163/B21 | 26 | 38 | 36 |

| AbdB-Gal4/+ | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| AbdB>UVRAGRNAi | 40 | 60 | 0 |

| AbdB>Rab5RNAi | 30 | 25 | 44 |

| AbdB>vps25RNAi | 70 | 30 | 0 |

| AbdB>EGFRRNAi | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| AbdB>NotchRNAi | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| AbdB>PVRRNAi | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| AbdB>PtcRNAi | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| AbdB>Notch | 46 | 54 | 0 |

| AbdB>NotchICD | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| AbdB>NotchECN | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| AbdB>Mastermind-N | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Rescue experiments (UVRAGKG04163/B21 background) | |||

|

| |||

| AbdB-Gal4/+ | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| AbdB>UVRAG | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| AbdB>EGFRRNAi | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| AbdB>NotchRNAi | 36 | 44 | 20 |

| AbdB>PVRRNAi | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| AbdB>PtcRNAi | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| AbdB>NotchECN | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| AbdB>Mastermind-N | 30 | 42 | 28 |

Interestingly, transgenic expression of UVRAG (Supplemental Fig. S3A) using genitalia-specific Abdominal B (AbdB)-Gal4 (de Navas et al., 2006; Speder et al., 2006) was sufficient to rescue the rotation defect in UVRAG mutants while central nervous system (elav-Gal4)- or fat body (Lsp2-Gal4)-specific expression did not (Fig. 2D, left and Table 1). These results showed a tissue-specific role of UVRAG in regulating organ rotation.

Quantitative RT-PCR analyses revealed that UVRAG expression is highest at the pupa stage (Supplemental Fig. S3B), and transient expression of UVRAG from late larval to early pupa stage (7±2 days after egg laying, AEL) sufficiently rescued the rotation defect in UVRAG mutants (Fig. 2D, right). This developmental stage-selective UVRAG function in organ rotation is consistent with the previously described Drosophila looping morphogenesis (Adam et al., 2003; Speder et al., 2006). Collectively, these results indicate that UVRAG plays crucial roles in organ rotation process during Drosophila development.

Autophagy may not be involved in the organ rotation process

Since mammalian UVRAG is known to regulate autophagy (Itakura et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2006, 2008; Zhong et al., 2009), we examined whether the organ rotation defect in UVRAG mutants is caused by impaired autophagy. We observed that the lysotracker staining and localization of Atg8, autophagy markers which localize to autophagosomes, showed punctuate patterns in wild type cells but not in UVRAG null cells in starved larval fat body in which autophagy occurs actively (Supplemental Fig. S4A) (Chang and Neufeld, 2009; Levine and Klionsky, 2004; Rusten et al., 2007). However, both wild type and UVRAG mutant larval genital discs showed dispersed Atg8 localization in the cytoplasm (Supplemental Fig. S4B), suggesting that autophagy does not actively occur in genital discs. Moreover, the cleavage of Atg8, which occurs during autophagy process (Klionsky et al., 2008; Rusten et al., 2004), was observed in wandering larva fat body while that was not observed in the pupa genitalia of both wild type and UVRAG mutant flies (Supplemental Fig. S4B).

We then examined whether the mutations of critical autophagy regulators cause rotation defects. Interestingly, loss-of-function mutants of Atg1 (Lee et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2004), Atg5 (Scott et al., 2004), Atg6 (Scott et al., 2004) and Atg7 (Juhasz et al., 2007) exhibited normal organ looping and genitalia orientation in contrast to UVRAG mutants (Supplemental Fig. S4C and Table S1). Collectively, these results suggest that autophagy does not account for the organ rotation defect in UVRAG mutants.

UVRAG mutant cells show defective endocytic degradation of signaling proteins

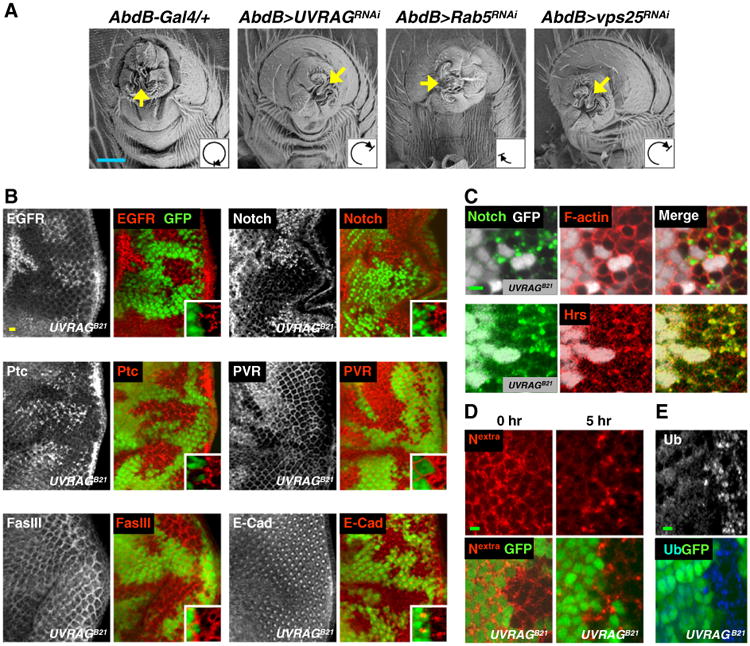

We next examined whether the organ rotation defects in UVRAG mutants is related to endocytic trafficking since UVRAG is also known to function in endocytosis (Itakura et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2008). Surprisingly, loss-of-function mutants of the genes for endocytic trafficking such as Rab5 (Lu and Bilder, 2005) and vps25 (Herz et al., 2006, 2009; Thompson et al., 2005; Vaccari and Bilder, 2005) showed incomplete genitalia rotation phenotypes similar to UVRAG mutants (Fig. 3A, Table 1 Supplemental Fig. S5A), strongly suggesting that the rotation defect in UVRAG mutants is due to impaired endocytosis.

Fig. 3.

Impaired receptor endocytic degradation in UVRAG-deficient cells. (A) Ventral side views of adult male genitalia were visualized by SEM. (B, C, E) Larval eye discs containing UVRAG null (UVRAGB21) clones were immunostained with antibodies against the indicated proteins and/or stained with TRITC-phalloidin (C). Inlets in (A) show the magnified images. (D) Endocytosis assay in live larval eye discs using anti-Notch extracellular domain antibody (Nextra, red). Scale bars: blue, 50 μm; yellow, 10 μm; green, 3 μm. Absence of GFP marks UVRAGB21 clones. Genotype: (B–E) eyFLP/+; UVRAGB21FRT40A/FRT40A UbiGFP.

To assess this possibility, we examined the cellular localization of several membrane proteins known to be regulated by endocytic trafficking. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Notch, Patched (Ptc) and PDGF/VEGF receptors (PVR) showed much stronger signals in GFP-negative UVRAG null clones than those in surrounding GFP-positive control cells (Fig. 3B, upper and middle). However, this was not the case for Fasciclin III (FasIII) and E-Cadherin (E-Cad) (Shilo, 1992; Tepass et al., 2001) (Fig. 3B, lower), implying that UVRAG primarily functions in stimulating endocytic trafficking of signaling receptors rather than cell adhesion proteins.

The enhanced signals of the receptors in UVRAG null clones showed irregular punctate structures (inlets in the upper and middle panels of Fig. 3B). By co-staining with organelle markers, we observed that the accumulated Notch was barely co-localized to the actin-enriched plasma membrane (Fig. 3C, upper) but markedly co-localized with the endosome marker Hrs (Jekely and Rorth, 2003; Lloyd et al., 2002) (Fig. 3C, lower). These data indicate that Notch is abnormally accumulated in endosomes in the absence of UVRAG. To further investigate the mechanism of receptor accumulation in UVRAG null cells, we performed time-course experiments in live larval discs using an antibody against the extracellular domain of Notch (Le Borgne and Schweisguth, 2003). In GFP-positive control cells, the cell surface-localized Notch proteins were internalized and disappeared within 5 h after chasing (Fig. 3D). On the other hand, Notch proteins in UVRAG null clones were internalized normally but trapped in vesicular structures even at 5 h of chasing (Fig. 3D). Consistently, ubiquitin known to be conjugated to the membrane receptors for lysosomal targeting and degradation (Jekely and Rorth, 2003; Katzmann et al., 2002) was also highly accumulated in UVRAG null clones (Fig. 3E). Collectively, these data show that UVRAG is required for the endocytic degradation of membrane-localized receptor proteins.

Notch is the key downstream target of UVRAG

We next examined genetic interactions between UVRAG and the receptors accumulated in UVRAG null cells (Fig. 3). While wing-specific UVRAG knockdown induced ruffling of wings (Supplemental Figs. 6A and B) (Hipfner and Cohen, 2003; Morrison et al., 2008), downregulation of Notch (Presente et al., 2002) alone was sufficient to suppress this phenotype (Supplemental Figs. 6A and B). However, downreglation of EGFR, Ptc or PVR (Supplemental Fig. S5B) (Rosin et al., 2004) was not (Supplemental Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the semi-lethality and increased number of wing hair cells in UVRAG-deficient flies were considerably relieved by Notch downregulation but enhanced by Notch over expression (Supplemental Figs. 6 and 7). Consistent with these genetic interaction data, UVRAG knockdown strongly enhanced the expression of Notch reporter, Notch Response Element (NRE)-EGFP (Saj et al., 2010) (Supplemental Fig. S6C), implying that Notch signaling is highly activated in UVRAG-deficient cells. Furthermore, the follicle cell proliferation and degenerated eyes of UVRAG null clones were also significantly rescued by Notch knock down (Supplemental Fig.S8). These specific and strong genetic interactions between UVRAG and Notch suggest that Notch is the key downstream target of UVRAG.

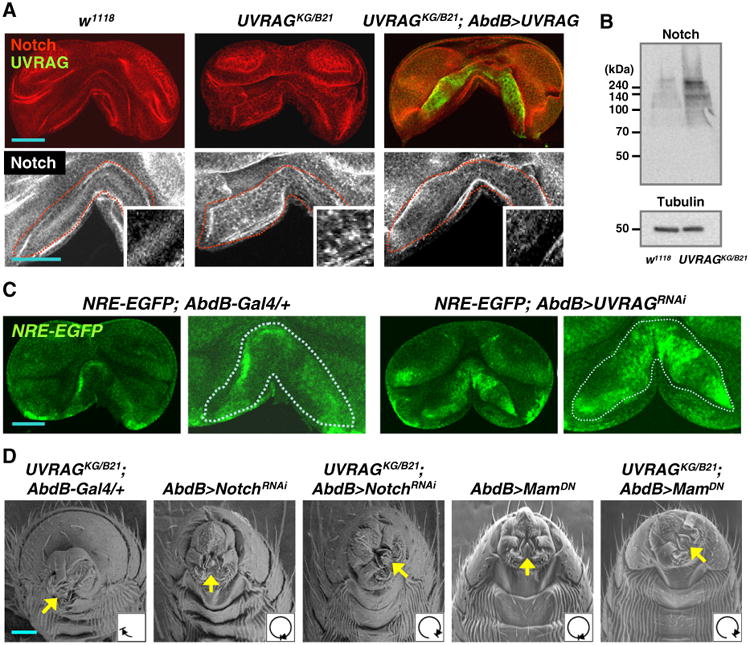

UVRAG regulates organ rotation by inhibiting Notch activity

We then assessed whether the organ rotation defect in UVRAG mutants is also caused by deregulated Notch signaling. We observed that downregulation of Notch rescued the rotation defect in UVRAG mutants, whereas downregulation of EGFR, Ptc or PVR did not (Table 1 and Fig. 4). In addition, the genital discs of UVRAG mutant showed much stronger punctate Notch signals and increased Notch protein level than that of wild type (Figs. 4A and B) (Acar et al., 2008; Vaccari et al., 2008). Transgenic UVRAG expression suppressed Notch accumulation (Fig. 4A) and rescued the rotation defect in UVRAG mutants (Fig. 2D and Table 1). The genital discs in UVRAG mutant exhibited increased expression of Notch reporter (NRE-EGFP) (Fig. 4C), indicating enhanced Notch activity in UVRAG mutant's genitalia.

Fig. 4.

Enhanced Notch activity is associated with the impaired genitalia rotation in UVRAG mutants. (A) Larval genital discs were immunostained with anti-Notch (red and white in upper and lower panels, respectively) and anti-UVRAG (green in upper panels) antibodies. Lower panels show the magnified images of the upper panels. Inlets in the lower panels show the highly magnified images. Red lines in the lower panels show the AbdB-Gal4-specific region. (B) Immunoblot analyses using anti-Notch intracellular domain antibody in the male pupa genital discs from wild type (w1118) and UVRAG mutant (UVRAGKG/B21). Full-length Notch is observed around 300 kDa and cleaved Notch is observed around 120 kDa. Tubulin was used as a loading control. (C) Comparison of the Notch activity using the NRE-EGFP reporter in larval genital discs expressing Gal4 control (left) or Gal4-driven UVRAG RNAi (right). Right panels show the magnified images of the left panels. White lines in the right panels show the AbdB-Gal4-specific region. (D) Ventral side views of the adult male genitalia from the indicated genotypes. MamDN, Matermind-N (Dominant negative form for transcription co-activator activity). Scale bars: 50 μm.

Furthermore, inhibition of Notch activity by expression of a dominant negative form of Mastermind, the Notch transcription co-activator (Kankel et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2000), rescued the genitalia rotation defect in UVRAG mutant (Fig. 4D and Table 1). Collectively, these data indicate that UVRAG regulates organ rotation by inhibiting Notch signaling.

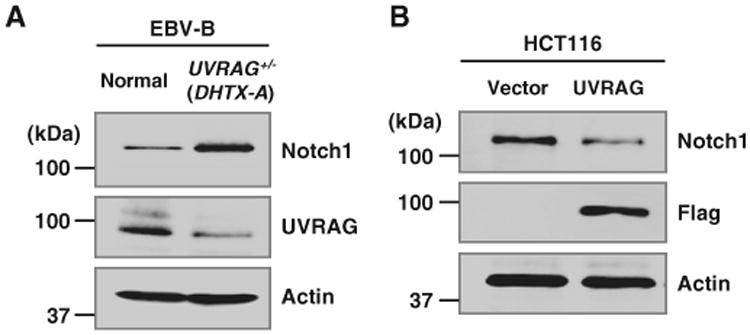

To examine whether the UVRAG's function in Notch regulation and organ rotation is also conserved in humans, we compared the amount of endogenous Notch1 proteins in human cells isolated from a normal patient and a heterotaxy patient with a monoallelic disruption of UVRAG (Iida et al., 2000). As observed in Drosophila (Figs. 3 and 4), UVRAG-deficient heterotaxy patient's cells showed a significantly increased level of Notch1 (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the amount of Notch1 was highly detected in human colon cancer HCT116 cells with a monoallelic loss of UVRAG (Liang et al., 2006) (Fig. 5B), but it was reduced upon the complementation of UVRAG expression (Fig. 5B). These data strongly suggest an evolutionarily conserved role of UVRAG to keep Notch signaling at appropriate levels in human cells as in Drosophila (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

UVRAG-deficient human cells show increased Notch level. (A, B) Immunoblot analyses using anti-Notch1, anti-UVRAG or anti-Flag antibodies in EBV-B cells from a normal patient or a heterotaxy patient with monoallelic disruption of UVRAG (UVRAG+/−; DHTX-A) (A) or UVRAG-mutated HCT116 cancer cell lines stably expressing empty vector or Flag-human UVRAG (B). Actin was used as a loading control.

Fig. 6.

The proposed action model of UVRAG. UVRAG-mediated endocytosis promotes degradation of Notch. In the absence of UVRAG, Notch is abnormally accumulated. The accumulation and activation of Notch lead to hyper cell proliferation and failure of left– right body patterning.

Discussion

Genetic analyses in human patients have indicated that UVRAG is encoded in one of the 17 chromosomal loci linked with heterotaxy (Iida et al., 2000; Kosaki and Casey, 1998), a condition showing defective pattern of typical left–right asymmetry for internal organs. In the present study, we found organ rotation defects in Drosophila UVRAG mutants, suggesting the evolutionarily conserved function of UVRAG in left–right body asymmetry formation from flies to humans.

Mammalian UVRAG has been known for regulating autophagy and vesicle trafficking (Itakura et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2006, 2008). Interestingly, our data showed that UVRAG's role in organ rotation was regulated specifically by endocytic trafficking rather than autophagy. Loss-of-function mutants of critical autophagy-regulating genes such as Atg1, Atg5, Atg6 and Atg7 showed normal organ rotation (Supplemental Fig. S4). In contrast, disruption of endocytic trafficking process by a loss-of-function mutation of Rab5 or vps25 caused incomplete organ rotation similar to UVRAG mutants (Fig. 3). As the mutations in these different components of vesicle trafficking pathway result in similar organ rotation failures in Drosophila, we strongly believe that some specific molecules delivered by cytosolic vesicles play crucial roles in the formation of left–right body asymmetry. Indeed, Myosin ID, the molecular motor protein, has been also suggested to control the direction of organ rotation by delivering specific intracellular cargos or vesicles (Hozumi et al., 2006; Speder et al., 2006).

The specific genetic interaction of UVRAG with Notch among several signaling proteins indicates that Notch is the key physiological target regulated by UVRAG. As shown by the receptor chasing assay in live imaginal discs, Notch was sufficiently removed from the plasma membrane to intracellular vesicles but constantly trapped in endosomes in UVRAG null cells (Fig. 3). Consistently, ubiquitin that labels membrane proteins destined for lysosomal degradation was also highly accumulated in UVRAG null cells (Fig. 3). These data suggest that UVRAG is required for the late endocytic trafficking or subsequent targeting of Notch to lysosomes.

Intriguingly, Notch signaling is increased in UVRAG-deficient cells (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Fig. S6). One possibility is that the endosome-accumulated Notch is activated via the increased accessibility of γ-secretase, which cleaves and releases an active form of Notch (Fortini, 2002; Pasternak et al., 2004). Nullifying the interaction of Notch with its extracellular ligands by expression of an extracellular domain of Notch (NotchECN) (Acar et al., 2008) did not rescue the rotation defect in UVRAG mutants (Table 1). On the other hand, inhibiting Notch activity by expressing a dominant negative form of Notch transcription co-activator, Mastermind (Kankel et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2000), did rescue the UVRAG mutant phenotype (Fig. 4 and Table 1). This is also in agreement with the previous studies suggesting that the endosomal activation of Notch occurs in a ligand-independent manner (Baron, 2003; Fortini, 2009; Vaccari et al., 2008).

The organ rotation defect in UVRAG mutants was rescued by Notch knockdown (Fig. 4 and Table 1). Conversely, expression of transgenic Notch impaired the genitalia rotation similar to UVRAG mutants (Table 1), and expression of a constitutively active form of Notch (NotchICD) (Acar et al., 2008) caused a much more severe phenotype (Table 1). In line with these data, mutations of Notch signaling in C. elegans, zebrafish, chicken and mouse have also been reported to cause defects in left–right patterning (Hermann et al., 2000; Krebs et al., 2003; Przemeck et al., 2003; Raya et al., 2003, 2004). Thus, the precise regulation of Notch signaling might be an evolutionarily conserved factor for the left–right body asymmetry formation (Lai, 2004).

Then how does Notch control body asymmetry formation? Since UVRAG regulates tissue growth via Notch signaling (Supplemental Figs. S6–S8), it is possible that the tissue enlargement nonspecifically caused organ rotation defect. However, we observed that expression of other cell growth regulators caused no or mild effect on the rotation even though they showed the increased tissue size similar to or even more seriously than UVRAG mutant (Supplemental Table S1 and Fig. S9). Meanwhile, Notch directly controls the expression of left–right patterning genes in other species; mouse (nodal; TGF-beta-like protein) (Krebs et al., 2003; Raya et al., 2003), zebrafish (charon; BMP antagonist protein) (Lopes et al., 2010) and Xenopus (pitx2; homeobox protein) (Sakano et al., 2010). In the similar manner, we examined the transcriptional profiles of several genes related to organ rotation in Drosophila such as JNK signaling molecules (puckered and scarface) (Macias et al., 2004; Rousset et al., 2010), apoptosis-related genes (dronc, hid and DIAP) (Abbott and Lengyel, 1991; Krieser et al., 2007; Suzanne et al., 2010) and actin cytoskeleton regulating genes (drac1 and cdc42) (Speder et al., 2006). Unfortunately, we could not observe significant changes in their expression levels both in UVRAG and Notch mutants (Supplemental Fig. S10). However, we still believe that there must be direct Notch downstream target genes regulating left–right body patterning in Drosophila.

In conclusion, the first knockout animexpression levels both in al model of UVRAG in this study recapitulates important aspects of UVRAG-mutated heterotaxy syndrome such as failure in the rotation of left–right asymmetric organs and severe developmental defects. Mechanistically, we also firstly demonstrated that UVRAG negatively regulates Notch activity by endocytic degradation in both flies and humans. Our findings suggest that Notch signaling can be a potential therapeutic target for treating UVRAG-mutated heterotaxy syndrome.

Material and methods

Drosophila genetics

UVRAGB7 and UVRAGB21 were generated by imprecise excisions of the P-element in KG04163 allele (Bloomington Stock Center). Genomic lesions were determined by genomic PCR and sequencing using primers: 5′-GCAGCTGTTGCCATTCTCCGAATAGG-3′ and 5′-GTTATGCTC-CAGTCGCGGGCG-3′. The following stocks were kindly provided by other groups: AbdB-Gal4 (a gift from Dr. Ernesto Sanchez-Herrero, Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, Spain), UAS-Notch and UAS-NotchECN (gifts of Dr. Hugo Bellen, Baylor College of Medicine, USA; originally generated by Dr. Gary Struhl, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, USA), hsFLP; ck13FRT40A (a gift from Dr. Kyung-Ok Cho, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology; originally generated by Dr. Hugo Bellen, Baylor College of Medicine, USA), hh-Gal4 (a gift from Dr. Masayuki Miura, University of Tokyo, Japan; originally generated by Dr. Tetsuya Tabata, University of Tokyo, Japan), UAS-GFPAtg8 (a gift from Dr. Harald Stenmark, University of Oslo, Norway), Atg7d14, Atg7d77, UAS-Atg5RNAi, UAS-mCherryAtg8 and hsFLP; UAS-2XeGFP FRT40A fb-Gal4 (gifts of Dr. Thomas Neufeld, University of Minnesota, USA), UAS-PvrRNAi (a gift of Dr. Ben-Zion Shilo, Weizmann Institute of Science, Israel), UAS-NotchICD (a gift of Dr. Jaeseob Kim, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology), UAS-UVRAGRNAi and UAS-PtcRNAi (National Institute of Genetics, Japan), GS17330 (Drosophila Genetic Resource Center, Kyoto Institute of Technology, Japan), UAS-Rab5RNAi, UAS-vps25RNAi and UAS-EGFRRNAi (VDRC Stock Center, Vienna Drosophila Research Center, Austria). Other stocks were obtained from Bloomington Stock Center (Indiana University, USA) or described elsewhere (Kim et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007; Lee and Chung, 2007).

GS17330 and UVRAGB21 were recombined with FRT40A to generate mosaic clones. For generating clones in adult ovary, flies were heat-shocked in 37 °C water bath for 1 h to stimulate the heat-shock inducible flippase at the second day after eclosion and dissected on the fifth day after eclosion. To generate clones in fat body, eggs were collected for 8 h and followed by heat-shock for 2 h. Wing mosaic clones were generated by 1 h heat-shock at the second day after egg laying. Mosaic eye clones were generated by flippase expressed by eyeless gene promoter (Tapon et al., 2001). For rescue experiments using hs-Gal4, eggs were collected for 4 h everyday for subsequent 11 day and heat-shocked for 1 h at the 11th day (Adam et al., 2003). For amino acid starvation, early third instar larvae were incubated for 4 h in wet kimwipes containing 20% (w/v) sucrose in PBS. Flies were raised at 25 °C on standard cornmeal/sucrose/yeast/agar media unless otherwise indicated.

Cell culture

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-immortalized human B cells (gifts from Dr. Hirofumi Ohashi, Saitama Children's Medical Center, Japan) and HCT116 and HEK293T cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Sigma-Aldrich) and Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Sigma-Aldrich), respectively, supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS (Invitrogen), 2 mM l-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco-BRL) at 37 °C under 5% CO2. HCT116 stable cell lines expressing an empty vector and Flag-human UVRAG are previously described (Liang et al., 2006).

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: Anti-Hrs (a gift from Dr. Hugo Bellen, Baylor College of Medicine, USA), anti-EGFR (a gift from Dr. Pernille Rorth, Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, Singapore), anti-PVR (a gift from Dr. Denise Montell, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, USA), anti-mono and poly ubiquitinylated proteins (clone No. FK2 and PW8810; Biomol), anti-beta-Tubulin, anti-Notch intracellular domain, anti-Notch extracellular domain, anti-Patched, anti-Fasciclin III, anti-E-Cadherin (E7, C17.9C6, C458.2H, APA1, 7G10, DCAD2; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, The University of Iowa, USA), anti-Flag, anti-human UVRAG, anti-Actin (F1804, U7508, A-3853; Sigma-Aldrich), anti-Notch1 (C-20), anti-GFP (sc-6014, sc-8334; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies. Anti-Drosophila UVRAG antibody was generated by immunizing rabbits with the peptide, CRYIERTQRDEVDERDGT-NH2 (Peptron, Korea).

Histology

Immunostaining analyses for tissues and cells were performed as previously described (Kim et al., 2006; Liang et al., 2008). TRITC-labeled phalloidin (Sigma-Aldrich) and Hoechst 33258 (Sigma-Aldrich) were used to visualize filamentous actin and DNA, respectively. For endocytic trafficking assays, larval eye imaginal discs were incubated with anti-Notch extracellular domain antibody in M3 medium at 4 °C for 5 min and chased for 5 h at 25 °C as previously described (Le Borgne and Schweisguth, 2003; Vaccari et al., 2008). LysoTracker staining was conducted as previously described (Juhasz et al., 2008; Scott et al., 2004). Briefly, fat body was fixed for 3 min in 2% paraformaldehyde in PBS, rinsed with PBS, incubated with 100 nM LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen) for 2 min, and then mounted using PBS. For mCherry-Atg8 or GFP-Atg8 detection, fat body or imaginal discs were mounted using 3% DABCO (Sigma-Aldrich) in 90% (v/v) glycerol in PBS. Adult wings were mounted in Canada balsam (Sigma-Aldrich):Methyl salicylate (Sigma Aldrich) (2:1).

Statistical analyses were performed using the Student's t test. Values are expressed as mean s.e.m. of at least three independent experiments.

Molecular biology

To generate transgenic flies, the full-length UVRAG (CG6116) cDNA (LD05963; Drosophila Genomics Resource Center) was cloned into Flag-tagged pUAST vector, and microinjected into w1118 embryos as previously described (Kim et al., 2006).

Immunoblot analyses for tissues and cells were performed as previously described (Kim et al., 2006; Liang et al., 2008). For immunoblot analyses of Notch in flies, samples were incubated for 20 min on ice in the buffer containing 10 mM KCl, 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 0.1% mercaptoethanol,1 mM EDTA with complete protease inhibitor cocktail. For immunoblot analyses of GFP-LC3 in flies, samples were lysed directly in SDS sample buffer.

RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR analyses were performed as previously described (Lee et al., 2007). The following primers were used for PCR:

| Forward | Reverse | |

|---|---|---|

| rp49 | 5′-GCTTCAAGATGACCATCCGCCC-3′ | 5′-GGTGCGCTTGTTCGATCCGTAAC-3′ |

| Actin | 5′-CGTCTTCCCATCGATTGTG-3′ | 5′-GATGCCAGGGTACATGGTG-3′ |

| UVRAG (RT-PCR) | 5′-CCAACGGCAGGAGATTCGGCGAAGC-3′ | 5′-GAGGTCGATCCATAATGATGGCTAAC-3′ |

| UVRAG (qRT-PCR) | 5′-CGTCTGGAGCTACGAACCCTGG-3′ | 5′-GCTCCATGTGGGGGAAGGCG-3′ |

| Rab5 | 5′-GAAGCAATATGCCGAGGAGA-3′ | 5′-CAAATGAAATTCGTCCCCTG-3′ |

| vps25 | 5′-CACCTTCCCACCCTTCTTT-3′ | 5′-CATCTCGATCAGCTCACAC-3′ |

| EGFR | 5′-GAGCTGGAGCAGATCACT-3′ | 5′-AGTGCAACCGTTGCATTC-3′ |

| Ptc | 5′-ATCGTAATGTGCTCCAATTTG-3′ | 5′-GAGCCGAGTTTGAGCATC-3′ |

| dronc | 5′-CTGGCTTTGGTGCCGTCAATTATCC-3′ | 5′-TTGCGCTGGACCGCAGAAGC-3′ |

| hid | 5′-ACCACCTCGTCGGCCACGCAGA-3′ | 5′-GGGTGCGCGGATGGGGATTC-3′ |

| diap | 5′-GATGGTCGCCCAACTGTCCACTG-3′ | 5′-ACACTGCCTGCCGCATTTACTGC-3′ |

| puckered | 5′-ACAACAACAATCGCATTGGTGCCAATC-3′ | 5′-CCATTGCCCAGCAATAGATGCGG-3′ |

| scarface | 5′-ACGGCGAAATTAGCGCCATAAACTACG-3′ | 5′-GAAGCTGGCACAGCAGTCGTAGG-3′ |

| drac1 | 5′-GCCACTGTCTTATCCCCAGACCG-3′ | 5′-GTGATGGGCGCCAGTTTCTTGTC-3′ |

| cdc42 | 5′-CGGTGGTCAGTCCCAGTTCCTT-3′ | 5′-CACTCCACGTACTTGACGGCCTT-3′ |

Microscopy

Confocal images were acquired using a LSM 510 or 710 confocal microscopes with LSM image browser v.3.2 SP2 software (Carl Zeiss). Other microscopy images were acquired using a digital camera (AxioCam) with AxioVS40AC v.4.4 software (Carl Zeiss) and a light microscopy (Leica). Scanning electron microscopy images were obtained by LEO1455VP (Carl Zeiss) or SUPRA55VP (Carl Zeiss) in a variable pressure secondary electron mode. Images were processed in Photoshop v.7.0 (Adobe).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ben-Zion Shilo, Denise Montell, Ernesto Sanchez-Herrero, Gary Struhl, Harald Stenmark, Hirofumi Ohashi, Hugo Bellen, Jaeseob Kim, Masayuki Miura, Pernille Rorth, Tetsuya Tabata and Thomas Neufeld for reagents and Drosophila lines. We are grateful to Drs. Kyung-Ok Cho, Kwang-Wook Choi and Young-YunKong for helpful discussion and kind support. We thank Bloomington Stock Center, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Drosophila Genetic Resource Center, Drosophila Genomics Resource Center, National Institute of Genetics and VDRC Stock Center for Drosophila stocks and antibodies, and Korea Basic Science Institute and National Instrumentation Center for Environmental Management (Seoul National University) for electron microscopic analysis. This work was supported by the National Creative Research Initiatives Program (2010-0018291) to J.C. and the Priority Research Centers Program (2009-0094022) to G.L. from the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (MEST) of Korea. J.J. was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants CA82057, CA91819, CA31363, CA115284, AI073099, the Fletcher Jones Foundation, the Hastings Foundation and the Korean GRL Program (K20815000001). C.L. was supported by AI083841, CA140964, the Lymphoma and Leukemia Society of USA, the Wright Foundation and the Baxter Foundation.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10. 1016/j.ydbio.2011.06.024.

Contributor Information

Jae U. Jung, Email: jaeujung@usc.edu.

Jongkyeong Chung, Email: jkc@snu.ac.kr.

References

- Abbott MK, Lengyel JA. Embryonic head involution and rotation of male terminalia require the Drosophila locus head involution defective. Genetics. 1991;129:783–789. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.3.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acar M, Jafar-Nejad H, Takeuchi H, Rajan A, Ibrani D, Rana NA, Pan H, Haltiwanger RS, Bellen HJ. Rumi is a CAP10 domain glycosyltransferase that modifies Notch and is required for Notch signaling. Cell. 2008;132:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam G, Perrimon N, Noselli S. The retinoic-like juvenile hormone controls the looping of left–right asymmetric organs in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:2397–2406. doi: 10.1242/dev.00460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron M. An overview of the Notch signalling pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2003;14:113–119. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(02)00179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekri S, Adelaide J, Merscher S, Grosgeorge J, Caroli-Bosc F, Perucca-Lostanlen D, Kelley PM, Pebusque MJ, Theillet C, Birnbaum D, Gaudray P. Detailed map of a region commonly amplified at 11q13→q14 in human breast carcinoma. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1997;79:125–131. doi: 10.1159/000134699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont JW, Mohapatra B, Towbin JA, Ware SM. Molecular genetics of heterotaxy syndromes. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:216–220. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilder D, Li M, Perrimon N. Cooperative regulation of cell polarity and growth by Drosophila tumor suppressors. Science. 2000;289:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgrove BW, Morelli SH, Yost HJ. Genetics of human laterality disorders: insights from vertebrate model systems. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2003;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.070802.110428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang YY, Neufeld TP. An Atg1/Atg13 complex with multiple roles in TOR-mediated autophagy regulation. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2004–2014. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-12-1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JM, Ding M, Aribi A, Shah P, Rao K. Loss of RAB25 expression in breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2957–2964. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutelis JB, Petzoldt AG, Speder P, Suzanne M, Noselli S. Left–right asymmetry in Drosophila. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2008;19:252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Navas L, Foronda D, Suzanne M, Sanchez-Herrero E. A simple and efficient method to identify replacements of P-lacZ by P-Gal4 lines allows obtaining Gal4 insertions in the bithorax complex of Drosophila. Mech Dev. 2006;123:860–867. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell'Angelica EC. AP-3-dependent trafficking and disease: the first decade. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V. Ay, there's the Rab: organelle maturation by Rab conversion. Dev Cell. 2005;9:446–448. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortini ME. Gamma-secretase-mediated proteolysis in cell-surface-receptor signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:673–684. doi: 10.1038/nrm910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortini ME. Notch signaling: the core pathway and its posttranslational regulation. Dev Cell. 2009;16:633–647. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goi T, Kawasaki M, Yamazaki T, Koneri K, Katayama K, Hirose K, Yamaguchi A. Ascending colon cancer with hepatic metastasis and cholecystolithiasis in a patient with situs inversus totalis without any expression of UVRAG mRNA: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:702–706. doi: 10.1007/s00595-002-2567-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gaitan M. Signal dispersal and transduction through the endocytic pathway. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:213–224. doi: 10.1038/nrm1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gaitan M, Stenmark H. Endocytosis and signaling: a relationship under development. Cell. 2003;115:513–521. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00932-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode S, Perrimon N. Inhibition of patterned cell shape change and cell invasion by discs large during Drosophila oogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2532–2544. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.19.2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermann GJ, Leung B, Priess JR. Left–right asymmetry in C. elegans intestine organogenesis involves a LIN-12/Notch signaling pathway. Development. 2000;127:3429–3440. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.16.3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz HM, Bergmann A. Genetic analysis of ESCRT function in Drosophila: a tumour model for human Tsg101. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:204–207. doi: 10.1042/BST0370204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz HM, Chen Z, Scherr H, Lackey M, Bolduc C, Bergmann A. vps25 mosaics display non-autonomous cell survival and overgrowth, and autonomous apoptosis. Development. 2006;133:1871–1880. doi: 10.1242/dev.02356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz HM, Woodfield SE, Chen Z, Bolduc C, Bergmann A. Common and distinct genetic properties of ESCRT-II components in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipfner DR, Cohen SM. The Drosophila sterile-20 kinase slik controls cell proliferation and apoptosis during imaginal disc development. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E35. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozumi S, Maeda R, Taniguchi K, Kanai M, Shirakabe S, Sasamura T, Speder P, Noselli S, Aigaki T, Murakami R, Matsuno K. An unconventional myosin in Drosophila reverses the default handedness in visceral organs. Nature. 2006;440:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nature04625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida A, Emi M, Matsuoka R, Hiratsuka E, Okui K, Ohashi H, Inazawa J, Fukushima Y, Imai T, Nakamura Y. Identification of a gene disrupted by inv(11)(q13.5; q25) in a patient with left–right axis malformation. Hum Genet. 2000;106:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s004390051038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ionov Y, Nowak N, Perucho M, Markowitz S, Cowell JK. Manipulation of nonsense mediated decay identifies gene mutations in colon cancer cells with microsatellite instability. Oncogene. 2004;23:639–645. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N. Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5360–5372. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekely G, Rorth P. Hrs mediates downregulation of multiple signalling receptors in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:1163–1168. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz G, Erdi B, Sass M, Neufeld TP. Atg7-dependent autophagy promotes neuronal health, stress tolerance, and longevity but is dispensable for metamorphosis in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3061–3066. doi: 10.1101/gad.1600707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz G, Hill JH, Yan Y, Sass M, Baehrecke EH, Backer JM, Neufeld TP. The class III PI(3)K Vps34 promotes autophagy and endocytosis but not TOR signaling in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:655–666. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200712051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kankel MW, Hurlbut GD, Upadhyay G, Yajnik V, Yedvobnick B, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Investigating the genetic circuitry of mastermind in Drosophila, a notch signal effector. Genetics. 2007;177:2493–2505. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.080994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann DJ, Odorizzi G, Emr SD. Receptor downregulation and multi-vesicular-body sorting. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:893–905. doi: 10.1038/nrm973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Lee JH, Koh H, Lee SY, Jang C, Chung CJ, Sung JH, Blenis J, Chung J. Inhibition of ERK-MAP kinase signaling by RSK during Drosophila development. EMBO J. 2006;25:3056–3067. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H, Agostinis P, Agrawal DK, Aliev G, Askew DS, Baba M, Baehrecke EH, Bahr BA, Ballabio A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy. 2008;4:151–175. doi: 10.4161/auto.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosaki K, Casey B. Genetics of human left–right axis malformations. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:89–99. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs LT, Iwai N, Nonaka S, Welsh IC, Lan Y, Jiang R, Saijoh Y, O'Brien TP, Hamada H, Gridley T. Notch signaling regulates left–right asymmetry determination by inducing nodal expression. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1207–1212. doi: 10.1101/gad.1084703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieser RJ, Moore FE, Dresnek D, Pellock BJ, Patel R, Huang A, Brachmann C, White K. The Drosophila homolog of the putative phosphatidylserine receptor functions to inhibit apoptosis. Development. 2007;134:2407–2414. doi: 10.1242/dev.02860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC. Notch signaling: control of cell communication and cell fate. Development. 2004;131:965–973. doi: 10.1242/dev.01074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Borgne R, Schweisguth F. Unequal segregation of neuralized biases Notch activation during asymmetric cell division. Dev Cell. 2003;5:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G, Chung J. Discrete functions of rictor and raptor in cell growth regulation in Drosophila. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:1154–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Clough EA, Yellon P, Teslovich TM, Stephan DA, Baehrecke EH. Genome-wide analyses of steroid- and radiation-triggered programmed cell death in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2003;13:350–357. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SB, Kim S, Lee J, Park J, Lee G, Kim Y, Kim JM, Chung J. ATG1, an autophagy regulator, inhibits cell growth by negatively regulating S6 kinase. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:360–365. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6:463–477. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TR, White KP. Tissue-specific gene expression and ecdysone-regulated genomic networks in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2003;5:59–72. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Feng P, Ku B, Dotan I, Canaani D, Oh BH, Jung JU. Autophagic and tumour suppressor activity of a novel Beclin1-binding protein UVRAG. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:688–699. doi: 10.1038/ncb1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Lee JS, Inn KS, Gack MU, Li Q, Roberts EA, Vergne I, Deretic V, Feng P, Akazawa C, Jung JU. Beclin1-binding UVRAG targets the class C Vps complex to coordinate autophagosome maturation and endocytic trafficking. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:776–787. doi: 10.1038/ncb1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd TE, Atkinson R, Wu MN, Zhou Y, Pennetta G, Bellen HJ. Hrs regulates endosome membrane invagination and tyrosine kinase receptor signaling in Drosophila. Cell. 2002;108:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes SS, Lourenco R, Pacheco L, Moreno N, Kreiling J, Saude L. Notch signalling regulates left–right asymmetry through ciliary length control. Development. 2010;137:3625–3632. doi: 10.1242/dev.054452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Bilder D. Endocytic control of epithelial polarity and proliferation in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1232–1239. doi: 10.1038/ncb1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias A, Romero NM, Martin F, Suarez L, Rosa AL, Morata G. PVF1/PVR signaling and apoptosis promotes the rotation and dorsal closure of the Drosophila male terminalia. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:1087–1094. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041859am. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda R, Hozumi S, Taniguchi K, Sasamura T, Murakami R, Matsuno K. Roles of single-minded in the left–right asymmetric development of the Drosophila embryonic gut. Mech Dev. 2007;124:204–217. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DN, Balgley B, Dutta S, Chen J, Rudnick P, Cranford J, Kantartzis S, DeVoe DL, Lee C, Baehrecke EH. Proteomic analysis of steroid-triggered autophagic programmed cell death during Drosophila development. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:916–923. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen DG, Peifer M. Puckered, a Drosophila MAPK phosphatase, ensures cell viability by antagonizing JNK-induced apoptosis. Development. 2005;132:3935–3946. doi: 10.1242/dev.01949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison HA, Dionne H, Rusten TE, Brech A, Fisher WW, Pfeiffer BD, Celniker SE, Stenmark H, Bilder D. Regulation of early endosomal entry by the Drosophila tumor suppressors Rabenosyn and Vps45. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4167–4176. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-07-0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura T, Utsuno H, Kuroda J, Gittenberger E, Asami T, Matsuno K. The development and evolution of left–right asymmetry in invertebrates: lessons from Drosophila and snails. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3497–3515. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AR. Symmetry breaking and the evolution of development. Science. 2004;306:828–833. doi: 10.1126/science.1103707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak SH, Callahanm JW, Mahuranm DJ. The role of the endosomal/lysosomal system in amyloid-beta production and the pathophysiology of Alzheimer's disease: reexamining the spatial paradox from a lysosomal perspective. J Alzheimers Dis. 2004;6:53–65. doi: 10.3233/jad-2004-6107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelman B, Dafni N, Naiman T, Eli D, Yaakov M, Feng TL, Sinha S, Weber G, Khodaei S, Sancar A, Dotan I, Canaani D. Molecular cloning of a novel human gene encoding a 63-kDa protein and its sublocalization within the 11q13 locus. Genomics. 1997;41:397–405. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presente A, Shaw S, Nye JS, Andres AJ. Transgene-mediated RNA interference defines a novel role for notch in chemosensory startle behavior. Genesis. 2002;34:165–169. doi: 10.1002/gene.10149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przemeck GK, Heinzmann U, Beckers J, Hrabe de Angelis M. Node and midline defects are associated with left–right development in Delta1 mutant embryos. Development. 2003;130:3–13. doi: 10.1242/dev.00176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raya A, Kawakami Y, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Buscher D, Koth CM, Itoh T, Morita M, Raya RM, Dubova I, Bessa JG, de la Pompa JL, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Notch activity induces Nodal expression and mediates the establishment of left– right asymmetry in vertebrate embryos. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1213–1218. doi: 10.1101/gad.1084403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raya A, Kawakami Y, Rodriguez-Esteban C, Ibanes M, Rasskin-Gutman D, Rodriguez-Leon J, Buscher D, Feijo JA, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Notch activity acts as a sensor for extracellular calcium during vertebrate left–right determination. Nature. 2004;427:121–128. doi: 10.1038/nature02190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosin D, Schejter E, Volk T, Shilo BZ. Apical accumulation of the Drosophila PDGF/VEGF receptor ligands provides a mechanism for triggering localized actin polymerization. Development. 2004;131:1939–1948. doi: 10.1242/dev.01101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset R, Bono-Lauriol S, Gettings M, Suzanne M, Speder P, Noselli S. The Drosophila serine protease homologue Scarface regulates JNK signalling in a negative-feedback loop during epithelial morphogenesis. Development. 2010;137:2177–2186. doi: 10.1242/dev.050781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusten TE, Lindmo K, Juhasz G, Sass M, Seglen PO, Brech A, Stenmark H. Programmed autophagy in the Drosophila fat body is induced by ecdysone through regulation of the PI3K pathway. Dev Cell. 2004;7:179–192. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusten TE, Vaccari T, Lindmo K, Rodahl LM, Nezis IP, Sem-Jacobsen C, Wendler F, Vincent JP, Brech A, Bilder D, Stenmark H. ESCRTs and Fab1 regulate distinct steps of autophagy. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1817–1825. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saj A, Arziman Z, Stempfle D, van Belle W, Sauder U, Horn T, Durrenberger M, Paro R, Boutros M, Merdes G. A combined ex vivo and in vivo RNAi screen for notch regulators in Drosophila reveals an extensive notch interaction network. Dev Cell. 2010;18:862–876. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakano D, Kato A, Parikh N, McKnight K, Terry D, Stefanovic B, Kato Y. BCL6 canalizes Notch-dependent transcription, excluding Mastermind-like1 from selected target genes during left–right patterning. Dev Cell. 2010;18:450–462. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato T, Mushiake S, Kato Y, Sato K, Sato M, Takeda N, Ozono K, Miki K, Kubo Y, Tsuji A, Harada R, Harada A. The Rab8 GTPase regulates apical protein localization in intestinal cells. Nature. 2007;448:366–369. doi: 10.1038/nature05929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott RC, Schuldiner O, Neufeld TP. Role and regulation of starvation-induced autophagy in the Drosophila fat body. Dev Cell. 2004;7:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto ES, Bellen HJ, Lloyd TE. When cell biology meets development: endocytic regulation of signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1314–1336. doi: 10.1101/gad.989602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo BZ. Roles of receptor tyrosine kinases in Drosophila development. FASEB J. 1992;6:2915–2922. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.11.1322852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin A, von Zastrow M. Endocytosis and signalling: intertwining molecular networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:609–622. doi: 10.1038/nrm2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speder P, Adam G, Noselli S. Type ID unconventional myosin controls left– right asymmetry in Drosophila. Nature. 2006;440:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature04623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speder P, Petzoldt A, Suzanne M, Noselli S. Strategies to establish left/right asymmetry in vertebrates and invertebrates. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzanne M, Petzoldt AG, Speder P, Coutelis JB, Steller H, Noselli S. Coupling of apoptosis and L/R patterning controls stepwise organ looping. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1773–1778. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K, Hozumi S, Maeda R, Ooike M, Sasamura T, Aigaki T, Matsuno K. D-JNK signaling in visceral muscle cells controls the laterality of the Drosophila gut. Dev Biol. 2007;311:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapon N, Ito N, Dickson BJ, Treisman JE, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila tuberous sclerosis complex gene homologs restrict cell growth and cell proliferation. Cell. 2001;105:345–355. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepass U, Tanentzapf G, Ward R, Fehon R. Epithelial cell polarity and cell junctions in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet. 2001;35:747–784. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BJ, Mathieu J, Sung HH, Loeser E, Rorth P, Cohen SM. Tumor suppressor properties of the ESCRT-II complex component Vps25 in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2005;9:711–720. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccari T, Bilder D. The Drosophila tumor suppressor vps25 prevents nonauto-nomous overproliferation by regulating notch trafficking. Dev Cell. 2005;9:687–698. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccari T, Bilder D. At the crossroads of polarity, proliferation and apoptosis: the use of Drosophila to unravel the multifaceted role of endocytosis in tumor suppression. Mol Oncol. 2009;3:354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccari T, Lu H, Kanwar R, Fortini ME, Bilder D. Endosomal entry regulates Notch receptor activation in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:755–762. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Aster JC, Blacklow SC, Lake R, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Griffin JD. MAML1, a human homologue of Drosophila mastermind, is a transcriptional co-activator for NOTCH receptors. Nat Genet. 2000;26:484–489. doi: 10.1038/82644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T, Rubin GM. Analysis of genetic mosaics in developing and adult Drosophila tissues. Development. 1993;117:1223–1237. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.4.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Wang QJ, Li X, Yan Y, Backer JM, Chait BT, Heintz N, Yue Z. Distinct regulation of autophagic activity by Atg14L and Rubicon associated with Beclin 1-phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:468–476. doi: 10.1038/ncb1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.