Abstract

Blepharophimosis-Ptosis-Epicanthus Inversus Syndrome (BPES) is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in FOXL2. We identified an individual with BPES and additional phenotypic features who did not have a FOXL2 mutation. We used whole exome sequencing to identify a de novo mutation in KAT6B (lysine acetyltransferase 6B) in this individual. The mutation was a 2 bp insertion leading to a frameshift which resulted in a premature stop codon. The resulting truncated protein does not have the C-terminal serine/methionine transcription activation domain necessary for interaction with other transcriptional and epigenetic regulators. This mutation likely has a dominant-negative or gain-of-function effect, similar to those observed in other genetic disorders resulting from KAT6B mutations, including Say-Barber-Biesecker-Young-Simpson (SBBYSS) and Genitopatellar syndrome (GTPTS). Thus, our subject’s phenotype broadens the spectrum of clinical findings associated with mutations in KAT6B. Furthermore, our results suggest that individuals with BPES without a FOXL2 mutation should be tested for KAT6B mutations. The transcriptional and epigenetic regulation mediated by KAT6B appears crucial to early developmental processes, which when perturbed can lead to a wide spectrum of phenotypic outcomes.

Keywords: Blepharophimosis, Ptosis, Epicanthus Inversus, BPES, KAT6B, Whole exome sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Blepharophimosis-Ptosis-Epicanthus Inversus Syndrome (BPES, [OMIM 110100]) is a rare genetic disorder with clinical features including dysplasia of the eyelids and palpebral fissures, low nasal bridge, and ptosis [Johnson et al., 1964; Oley et al., 1988]. It has two forms: Type I with premature ovarian failure, and Type II without ovarian failure [Zlotogora et al., 1983]. Mutations in FOXL2 (OMIM 605597) have been found in the majority (88%) of individuals with Type I and II BPES. [Crisponi et al., 2001; Beysen et al., 2005]. Causative mutations detected in FOXL2 range in size from single nucleotide point mutations [Ramírez-Castro et al., 2002; Dollfus et al., 2003; Udar et al., 2003] to deletions and copy number variations (CNV) encompassing FOXL2 [Crisponi et al., 2001; De Baere et al., 2003; Beysen et al., 2005]. While 81% of mutations were intragenic within FOXL2, 12% were microdeletions affecting FOXL2 and its neighboring genes, the remaining 5% were deletions apparently affecting regulatory regions [Beysen et al., 2009]. Microdeletions encompassing a larger genomic region around FOXL2 were found in individuals referred to as BPES plus, who in addition to BPES have additional features, such as developmental delay, speech delay and genital anomaly [Costa et al., 1998; D’haene et al., 2009; D’haene et al., 2010; Zahanova et al., 2012]. Further, a subset of BPES plus individuals (33%) was found to have other pathogenic CNVs not affecting FOXL2 [Gijsbers et al., 2008; D’haene et al., 2010].

Besides FOXL2, several genes have also been associated with blepharophimosis-mental retardation (BMR) syndromes [Verloes et al., 2006], such as UBE3B (OMIM 608047) in blepharophimosis-ptosis-intellectual disability syndrome (BPIDS, [OMIM 615057]) and MED12 (OMIM 300188) in X-linked Ohdo syndrome (OHDOX, [OMIM 300895]), demonstrating genetic heterogeneity of this group of disorders [Basel-Vanagaite et al., 2012; Vulto-van Silfhout et al., 2013]. In recent studies, pathogenic mutations in KAT6B (OMIM 605880), a histone acetyl transferase gene, have been observed in individuals with phenotypic features that overlap with BPES plus, including an individual initially diagnosed with Noonan syndrome (NS1, [OMIM 163950]) and individuals with Say-Barber-Biesecker-Young-Simpson syndrome (SBBYSS, [OMIM 603736]) and Genitopatellar syndrome (GTPTS, [OMIM 606170]) [Kraft et al., 2011; Clayton-Smith et al., 2011; Simpson et al., 2012; Campeau et al., 2012; Szakszon et al., 2013]. Noonan syndrome is characterized by reduced growth, cardiac defects, and facial dysmorphism, including hypertelorism, ptosis, downslanting palpebral fissures and low-set, posteriorly angulated ears [Noonan, 1994; Shah et al., 1999; Tartaglia et al., 2010]. SBYSS, a variant of Ohdo syndrome, is associated with intellectual disability and has a distinctive facial appearance including severe blepharophimosis, immobile face, bulbous nasal tip and a small mouth with a thin upper lip [Clayton-Smith et al., 2011], while individuals with GTPTS may exhibit microcephaly, broad nose, a small or retracted chin, flexion contractures of lower limbs, abnormal or missing patellae, and urogenital anomalies [Penttinen et al., 2009].

We report an individual with clinical features typically associated with BPES with additional findings including global developmental delay, syndactyly, and cryptorchidism, but who did not have a FOXL2 mutation. Whole exome sequencing (WES) of the subject and his unaffected parents identified a rare, de novo 2 bp insertion in exon 18 of KAT6B. The mutation resulted in frameshift leading to a premature stop codon. Our subject’s clinical presentation broadens the phenotypic spectrum seen in individuals with mutations in KAT6B, further suggesting that FOXL2-negative BPES individuals with a complex clinical presentation should be tested for KAT6B mutations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subject Enrollment and Sample Collection

The patient and his parents were enrolled into an IRB approved research protocol at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). High quality, unamplified, and unfragmented genomic DNA (A260/A280 ≥ 1.8 and A260/A230 ≥ 1.9) was extracted from whole blood obtained from the subject and his parents using Puregene Blood kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA).

FOXL2 Mutation Screening

Genomic DNA samples from the patient and his parents (100 ng) were amplified by using two sets of primers specific to FOXL2 (NM_023067.3). Forward primer 1: 5′-GAGCTTAGGAAAGCGAAAAAGCAC AGAGGG-3′, reverse primer1: 5′-GAAGACATGTTCGAGAAGGGCAACTACCG-3′, forward primer 2: 5′-GTTGAGGAAGCCAGACTGCAGGTACTTGGG-3′, and reverse primer 2: 5′-TCTCCAGAAGTTTGAGACTTGGCCGTAAGC-3′. PCR reaction and conditions were as follows: Promega (Madison, WI) GoTaq Hot Start kit with 1× Master Mix and 400 nM of each primer. PCR began with an initial cycle at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 30 second and 72°C for 1 minute, finishing with extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. Amplified PCR products were sequenced using the PCR primers as sequencing primers on an ABI (Carlsbad, CA) PRISM 3730xl at a commercial sequencing facility. High resolution copy number analysis was performed using Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA) SNP 500K arrays as previously described [Haldeman-Englert et al., 2010].

Exome Sequencing and Data Analysis

Whole exome sequencing was performed on the subject and his parents using Nimblegen (Madison, WI) SeqCap EZ Exome v2.0 followed by sequencing on an Illumina (San Diego, CA) HiSeq 2000. Details of data analysis were similar to the procedure as previously described [Yu et al., 2013]. Approximately 50 million, 90 bp, paired-end reads (>50×) were obtained and mapped to the reference human genome (NCBI build 37) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) [Li et al., 2009a]. Variants were determined by the utilities in the SAMtools [Li et al., 2009b] and further annotated using SeattleSeq (http://snp.gs.washington.edu/SeattleSeqAnnotation134/). Filtering and test of inheritance model were done using tools in Galaxy [Goecks et al., 2010]. Subject’s Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) were filtered to retain calls that met the following criteria; bases with PHRED-scaled score > 20, SNP and consensus scores > 50, read coverage > 8 with > 25% of the reads containing the variant call. For homozygous/hemizygous variant calls, > 80% reads were required to contain the variant, while for heterozygous variant calls, the number of reads containing the variant call ranged between 25%–80%. Insertions and deletions of <50 bp (InDels) were filtered based on similar criteria except that the SNP and consensus score was required to be >100. Variants found in segmental duplications, simple- or low-complexity repeats were removed due to the higher likelihood of mapping errors. Sequence data from parental samples were used as an additional filter to confirm variant calls in the subject. The filtering criteria for variant calling in parental data were less stringent than in the subject in order to minimize erroneous classification of variants as unique to the subject. Thus, the criteria for parental data included SNP score >5 for SNVs and SNP score >10 for InDels, and required that at least two reads contain the variant call. Variants were filtered against dbSNP build 135 and 1000 Genomes (November 23, 2010 release version). The sequence data from the family was then used to test for causal variants under different inheritance models, including de novo mutation in a dominant model and compound heterozygous, homozygous and X-linked hemizygous mutations in recessive models.

PCR and Sanger Sequencing Verification

Validation of mutation was by PCR amplification followed by Sanger sequencing using forward primer of 5′-ATACGAGCGAATGGGTCAGAGTGATTTTGG-3′ and reverse primer of 5′-GTTCACAGAGTTGACATTGTAGGCTGGCG-3′. Amplification and sequencing conditions were the same as described above. Mutations detected in KAT6B were named using cDNA accession number NM_012330.3.

RESULTS

Clinical Report

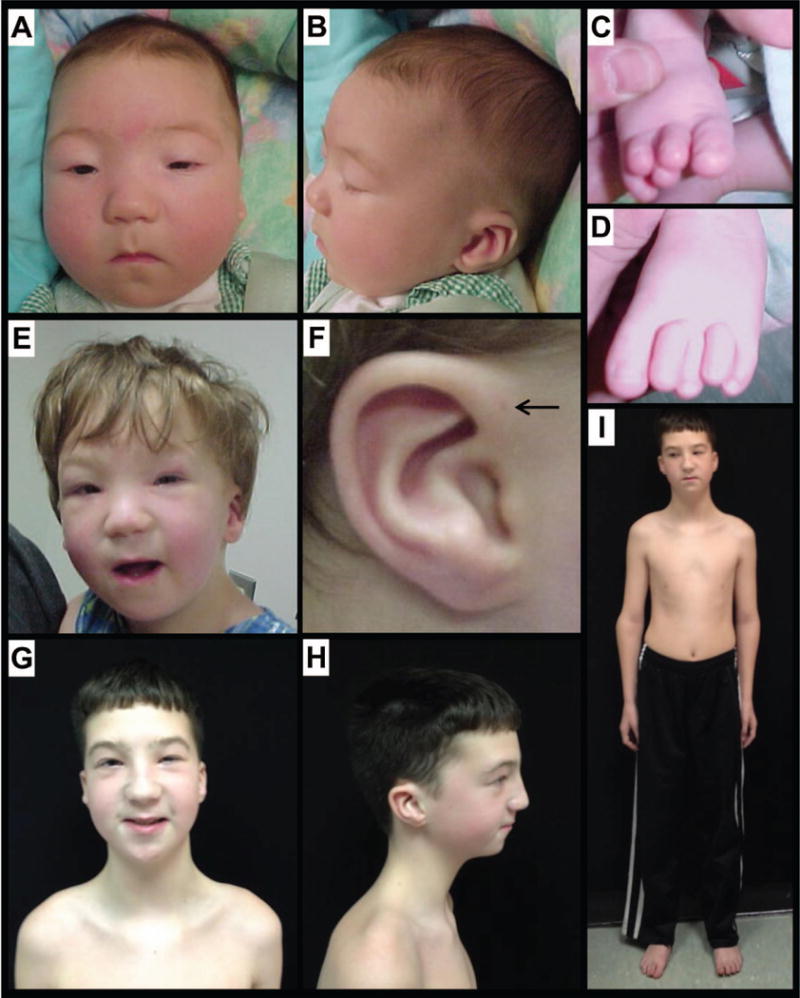

The patient was a 7-month-old boy when first evaluated at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). He was diagnosed with BPES by a pediatric ophthalmologist. In addition to blepharophimosis, ptosis and epicanthus inversus normally associated with BPES, he had cryptorchidism, right hydrocele, wide-spaced nipples, and slight 2–3 syndactyly of toes (Fig. 1). Clinical testing demonstrated a normal karyotype (46, XY), and normal FISH studies for 22q11.2 deletion, Cri-du-Chat syndrome. Thyroid function was normal (thyroxine=4.9 mcg/dL, normal range=4.7–9.9 mcg/dL; TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone=3.58 ulU/mL, normal range=0.5–3.8 ulU/mL). Further, normal 7-dehydrocholesterol level was used to rule out Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Sanger sequencing and high-resolution CNV analysis with Affymetrix SNP 500K arrays did not identify a FOXL2 mutation.

FIG 1.

Clinical features of the subject. A–D: subject at 2 months of age; note blepharophimosis, ptosis, epicanthus inversus (A), posteriorly angulated ears with thickened superior helix and prominent antihelix (B), and slight 2–3 syndactyly of toes in addition to overlapping toes (C, D). E,F: subject at 3.5 years of age following oculoplastic surgery to correct ptosis; note right-sided preauricular ear pit (F, indicated by arrow). G–I: subject at 12 years of age; note the recurrence of ptosis (L>R), arched eyebrows, abnormal ears, thin upper lip vermilion, small pointed chin, downsloping shoulders and wide-spaced and low-set nipples.

Whole Exome Sequencing

Whole exome sequencing analysis was performed on the subject and his unaffected parents to obtain over 50× coverage of targeted exome in each sample. A large number of variants (77,525 variants) were detected in the subject after applying appropriate quality measures (Table I). Our downstream analyses was focused on nonsynonymous coding variants, coding InDels (insertions/deletions <50 bp) and variants affecting splice sites as they are likely to have a functional impact on the gene product, and hence likely pathogenic (9,024 variants). We first filtered out common variants seen in dbSNP and 1000 genomes. This resulted in the identification of 183 rare variants in the subject that were considered for further analysis. Parental WES data was used to detect the pathogenic variant under various inheritance models including dominant (de novo mutations) and recessive (compound heterozygous, homozygous, and X-linked hemizygous mutations) models.

Table I.

Summary of Exome Variants and Test of Inheritance Models

| Subject | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total variants | 77,525 | |||

| Coding variants | 18,604 | |||

| Nonsynonymous, splice-site, InDel variants | 9,024 | |||

| Rare variants | 183 | |||

|

| ||||

| Test of inheritance model | Dominant model

|

Recessive models

|

||

| de novo | Compound heterozygous | Homozygous | X-linked hemizygous | |

| 1 (KAT6B) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

There was no strong candidate in the recessive models, but under a dominant model we identified a candidate gene with a potentially pathogenic mutation. The candidate, KAT6B, carried a de novo heterozygous 2 base-pair insertion/duplication c.5623_5624dupCA in exon 18. The number of variants in each filtering step and the final expected number of rare and de novo mutations (<1 per trio) were in accordance with previous studies [Vissers et al., 2010; O’Roak et al., 2011; Sanders et al., 2012; Neale et al., 2012].

Validation by Sanger Sequencing

The mutation in the subject was verified by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 2A). Both parents had normal alleles, but the subject had a heterozygous 2 bp insertion (or CA duplication) in KAT6B (NM_012330.2) located on chromosome 10q22.2. The subjects mutation, c.5623_5624dupCA, was located in the largest and the last exon (exon 18) of KAT6B, and resulted in frameshift and a premature stop codon, p.Gln1875Hisfs*5, interrupting the C-terminal of KAT6B which has a serine/methionine-rich transcription activation domain (Fig. 2B). KAT6B is a histone acetyltransferase believed to be an epigenetic and transcriptional regulator for a broad range of cellular processes [Yang et al., 2007].

FIG. 2.

Pathogenic mutations in KAT6B. A: Chromatograph showing Sanger sequencing results of the subject shows a rare de novo heterozygous c.5623_5624dupCA (p.Gln1875Hisfs*5) frameshift mutation while parents have two normal alleles. The 2 bp CA duplication in the subject results in mixed peaks after the duplication site. B: In the top panel, protein domains of KAT6B are shown. It has a histone binding domain consisting of H15 (linker histones H1- and H5-like module) and PHD (plant homeodomain zink fingers) domains, a histone acetylation HAT (histone acetyltransferase) domain, an acidic glutamate/aspartate-rich domain, and a transcription activation serine/methionine-rich domain [Champagne et al., 1999; Pelletier et al., 2002]. The second panel shows KAT6B coding exons as gray boxes with exon number indicated. Locations of pathogenic mutations identified in our subject and other recently identified genetic disorders are indicated by arrows. Mutations found in our subject (red), SBBYSS (brown and orange), and GTPTS (green and blue) are always nonsense or frameshift truncating mutations.

DISCUSSION

We used whole exome sequencing in a trio-based (proband and his unaffected, biological parents) approach to identify a de novo mutation in a histone acetyltransferase gene, KAT6B, in a patient with BPES and additional features. KAT6B, also known as MYST4, MORF, MOZ2 or qkf, belongs to a 5-membered MYST family of genes also consisting of Moz, Ybf2/Sas3, Sas2 and Tip60 [Champagne et al., 1999]. KAT6B is proposed to function either as a transcription factor or an epigenetic regulator on a broad range of genes and cellular functions [Yang et al., 2007]. KAT6B interacts with other proteins like BRPFs (bromodomain-PHD finger proteins), ING5 (inhibitor of growth 5), and EAF6 (Esa1-associated factor 6 ortholog) [Pelletier et al., 2002; Ullah et al., 2008]. This multi-protein complex then interacts with RUNX transcription factors for transcriptional activation of downstream genes [Champagne et al., 1999; Pelletier et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2007]. The interaction with its protein partners also stimulates the histone acetyltransferase activity of KAT6B allowing it to acetylate nucleosomal histone H3, which is an activating histone mark [Yang et al., 2007; Ullah et al., 2008; Kraft et al., 2011]. Our subject’s mutation, c.5623_5624dupCA is located in exon 18 and truncates the serine/methionine-rich transcription activation domain at the C-terminus. Thus, it is expected that the mutated protein cannot interact with RUNX transcription factors necessary for its function in transcriptional activation.

Mutations in KAT6B have been associated with several other disorders associated with a wide variety of phenotypic features. Haploinsufficiency of KAT6B resulting from a balanced, de novo translocation t(10;13)(q22.3;q34) interrupting the gene has been observed in an individual with a Noonan syndrome-like phenotype [Kraft et al., 2011]. However, the phenotype observed in our subject appears to be more complex (Table II). Clayton-Smith et al. [2011] found pathogenic KAT6B mutations in 13 individuals with Say-Barber-Biesecker-Young-Simpson syndrome through exome sequencing [Clayton-Smith et al., 2011]. Two additional SBBYSS individuals were later reported by Szakszon et al. [2013]. Whole exome sequencing also identified pathogenic KAT6B mutations in 11 individuals with genitopatellar syndrome [Simpson et al., 2012; Campeau et al., 2012]. The presence of genital anomalies in our patient is consistent with similar findings in SBBYSS and genitopatellar syndrome. Thus, based on the available literature [Day et al., 2008; Clayton-Smith et al., 2011], our patient’s phenotype most closely resembles SBBYSS.

Table II.

Comparison of Phenotypic Features

| This study, BPES Plus | Noonan-likea | SBBYSSb,e | GTPTSc,d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological anomalies | Global developmental delay | Microcephaly, ADHD, IQ 75–80, no structural defects | Developmental or intellectual delay, microcephaly in minority, hypotonia, no structural defects | Developmental or intellectual delay, microcephaly in all, agenesis of the corpus callosum, colpocephaly |

| Facial anomalies | Blepharophimosis, ptosis, epicanthus inversus | Blepharophimosis, ptosis, arched eyebrows, abnormal ears, smooth philtrum, retrognathia, high palate | Blepharophimosis, ptosis, broad and flat nasal bridge, bulbous nose, full cheeks, abnormal ears, small mouth, expressionless facies | Broad or prominent nasal bridge, bulbous nose in minority, full cheeks in minority |

| Musculo-skeletal anomalies | Widely-spaced nipples, slight 2–3 syndactyly | Short stature, delayed bone age, ligamentous laxity | Long thumbs and toes, patellar anomalies in minority | Absent or hypoplastic patellae in majority, flexion contractures, club feet, costo-vertebral anomalies, pelvic anomalies |

| Genital anomalies | Cryptorchidism, right hydrocele | Cryptorchidism and hypospadias | Anal anomalies, hypoplastic labia, clitoromegaly, scrotal hypoplasia, cryptorchidism |

Adapted from Campeau et al., 2012a.

Campeau et al., 2012a

KAT6B mutations identified in individuals with the above diseases are de novo, nonsense or frameshift mutations resulting in truncated protein (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, most of the mutations in SBBYSS cluster within exon 18 of KAT6B lead to a truncated KAT6B with intact N-terminal domains, but missing C-terminal serine/methionine-rich transcription activation domain. These authors concluded that the loss of serine/methionine-rich transcription activation domain has either dominant-negative or gain-of-function effects. Alternatively, in a majority of individuals with GTPTS, the mutations are more centrally located within the acidic region of the protein (Fig.2B).

Although the truncated KAT6B has an intact histone acetyltransferase (HAT) domain, there was a significant reduction of histone H3 and H4 acetylation in the affected individuals, apparently due to its lower histone acetylation activity [Kraft et al., 2011; Simpson et al., 2012]. Yet, the effect of reduced histone acetylation activity of KAT6B on its interaction with RUNX transcription factors remains unclear [Simpson et al., 2012]. Recently, mutations in MLL2 (OMIM 602113) and KDM6A (OMIM 300128) were identified in individuals with Kabuki syndrome 1 (KABUK1, [OMIM 147920]) and Kabuki syndrome 2 (KABUK2, [OMIM 300867]), respectively [Hannibal et al., 2011; Lederer et al., 2012; Miyake et al., 2013]. Kabuki syndrome is a multiple congenital anomaly (MCA) syndrome including distinctive facial features, intellectual disability along with cardiac, skeletal and immunological defects [Niikawa et al., 1981]. Interestingly, MLL2 and KDM6A are histone methyltransferases, involved in histone modification just like KAT6B. This suggests that epigenetic regulation in the form of histone modification plays an important role in early human development, and mutations that perturb these processes can result in genetic disorders leading to MCA.

In summary, the simultaneous exome sequencing of a proband and his unaffected parents has enabled us to identify the causative mutation underlying the MCA. This underscores the efficacy of whole exome and whole genome sequencing technologies in identifying the genetic mutations underlying a majority of Mendelian disorders, especially in one-off cases in which multiple individuals with an overlapping phenotype or syndrome are not available. The candidate gene, KAT6B, has been implicated previously in a wide spectrum of disorders with partially overlapping but not characteristic phenotypes. Our findings extend the phenotypic spectrum observed in individuals with KAT6B mutations and highlight KAT6B as a strong candidate gene in individuals with BPES who present with additional, atypical congenital anomalies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (GM081519 to T.H.S). We are very grateful to the subject and his family for participating in this study.

Footnotes

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Basel-Vanagaite L, Dallapiccola B, Ramirez-Solis R, Segref A, Thiele H, Edwards A, Arends MJ, Miró X, White JK, Désir J, Abramowicz M, Dentici ML, Lepri F, Hofmann K, Har-Zahav A, Ryder E, Karp NA, Estabel J, Gerdin AKB, Podrini C, Ingham NJ, Altmüller J, Nürnberg G, Frommolt P, Abdelhak S, Pasmanik-Chor M, Konen O, Kelley RI, Shohat M, Nürnberg P, Flint J, Steel KP, Hoppe T, Kubisch C, Adams DJ, Borck G. Deficiency for the ubiquitin ligase UBE3B in a blepharophimosis-ptosis-intellectual-disability syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:998–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beysen D, Raes J, Leroy BP, Lucassen A, Yates JRW, Clayton-Smith J, Ilyina H, Brooks SS, Christin-Maitre S, Fellous M, Fryns JP, Kim JR, Lapunzina P, Lemyre E, Meire F, Messiaen LM, Oley C, Splitt M, Thomson J, Van de Peer Y, Veitia RA, De Paepe A, De Baere E. Deletions involving long-range conserved nongenic sequences upstream and downstream of FOXL2 as a novel disease-causing mechanism in blepharophimosis syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:205–218. doi: 10.1086/432083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beysen D, De Paepe A, De Baere E. FOXL2 mutations and genomic rearrangements in BPES. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:158–169. doi: 10.1002/humu.20807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campeau PM, Kim JC, Lu JT, Schwartzentruber JA, Abdul-Rahman OA, Schlaubitz S, Murdock DM, Jiang M-M, Lammer EJ, Enns GM, Rhead WJ, Rowland J, Robertson SP, Cormier-Daire V, Bainbridge MN, Yang XJ, Gingras MC, Gibbs RA, Rosenblatt DS, Majewski J, Lee BH. Mutations in KAT6B, encoding a histone acetyltransferase, cause Genitopatellar syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:282–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne N, Bertos NR, Pelletier N, Wang AH, Vezmar M, Yang Y, Heng HH, Yang XJ. Identification of a human histone acetyltransferase related to monocytic leukemia zinc finger protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28528–28536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton-Smith J, O’Sullivan J, Daly S, Bhaskar S, Day R, Anderson B, Voss AK, Thomas T, Biesecker LG, Smith P, Fryer A, Chandler KE, Kerr B, Tassabehji M, Lynch SA, Krajewska-Walasek M, McKee S, Smith J, Sweeney E, Mansour S, Mohammed S, Donnai D, Black G. Whole-exome-sequencing identifies mutations in histone acetyltransferase gene KAT6B in individuals with the Say-Barber-Biesecker variant of Ohdo syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:675–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa T, Pashby R, Huggins M, Teshima IE. Deletion 3q in two patients with blepharophimosis-ptosis-epicanthus inversus syndrome (BPES) J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1998;35:271–276. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19980901-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisponi L, Deiana M, Loi A, Chiappe F, Uda M, Amati P, Bisceglia L, Zelante L, Nagaraja R, Porcu S, Ristaldi MS, Marzella R, Rocchi M, Nicolino M, Lienhardt-Roussie A, Nivelon A, Verloes A, Schlessinger D, Gasparini P, Bonneau D, Cao A, Pilia G. The putative forkhead transcription factor FOXL2 is mutated in blepharophimosis/ptosis/epicanthus inversus syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;27:159–166. doi: 10.1038/84781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day R, Beckett B, Donnai D, Fryer A, Heidenblad M, Howard P, Kerr B, Mansour S, Maye U, McKee S, Mohammed S, Sweeney E, Tassabehji M, de Vries BBA, Clayton-Smith J. A clinical and genetic study of the Say/Barber/Biesecker/Young-Simpson type of Ohdo syndrome. Clin Genet. 2008;74:434–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Baere E, Beysen D, Oley C, Lorenz B, Cocquet J, De Sutter P, Devriendt K, Dixon M, Fellous M, Fryns JP, Garza A, Jonsrud C, Koivisto PA, Krause A, Leroy BP, Meire F, Plomp A, Van Maldergem L, De Paepe A, Veitia R, Messiaen L. FOXL2 and BPES: mutational hotspots, phenotypic variability, and revision of the genotype-phenotype correlation. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:478–487. doi: 10.1086/346118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’haene B, Attanasio C, Beysen D, Dostie J, Lemire E, Bouchard P, Field M, Jones K, Lorenz B, Menten B, Buysse K, Pattyn F, Friedli M, Ucla C, Rossier C, Wyss C, Speleman F, De Paepe A, Dekker J, Antonarakis SE, De Baere E. Disease-causing 7.4 kb cis-regulatory deletion disrupting conserved non-coding sequences and their interaction with the FOXL2 promotor: implications for mutation screening. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’haene B, Nevado J, Pugeat M, Pierquin G, Lowry RB, Reardon W, Delicado A, García-Miñaur S, Palomares M, Courtens W, Stefanova M, Wallace S, Watkins W, Shelling AN, Wieczorek D, Veitia RA, De Paepe A, Lapunzina P, De Baere E. FOXL2 copy number changes in the molecular pathogenesis of BPES: unique cohort of 17 deletions. Hum Mutat. 2010;31:E1332–1347. doi: 10.1002/humu.21233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollfus H, Stoetzel C, Riehm S, Lahlou Boukoffa W, Bediard Boulaneb F, Quillet R, Abu-Eid M, Speeg-Schatz C, Francfort JJ, Flament J, Veillon F, Perrin-Schmitt F. Sporadic and familial blepharophimosis -ptosis-epicanthus inversus syndrome: FOXL2 mutation screen and MRI study of the superior levator eyelid muscle. Clin Genet. 2003;63:117–120. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goecks J, Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R86. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijsbers ACJ, D’haene B, Hilhorst-Hofstee Y, Mannens M, Albrecht B, Seidel J, Witt DR, Maisenbacher MK, Loeys B, van Essen T, Bakker E, Hennekam R, Breunin MH, De Baere E, Ruivenkamp CAL. Identification of copy number variants associated with BPES-like phenotypes. Hum Genet. 2008;124:489–498. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldeman-Englert CR, Chapman KA, Kruger H, Geiger EA, McDonald-McGinn DM, Rappaport E, Zackai EH, Spinner NB, Shaikh TH. A de novo 8.8-Mb deletion of 21q21.1–q21.3 in an autistic male with a complex rearrangement involving chromosomes 6, 10, and 21. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:196–202. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannibal MC, Buckingham KJ, Ng SB, Ming JE, Beck AE, McMillin MJ, Gildersleeve HI, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, Mefford HC, Cook J, Yoshiura K, Matsumoto T, Matsumoto N, Miyake N, Tonoki H, Naritomi K, Kaname T, Nagai T, Ohashi H, Kurosawa K, Hou JW, Ohta T, Liang D, Sudo A, Morris CA, Banka S, Black GC, Clayton-Smith J, Nickerson DA, Zackai EH, Shaikh TH, Donnai D, Niikawa N, Shendure J, Bamshad MJ. Spectrum of MLL2 (ALR) mutations in 110 cases of Kabuki syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:1511–1516. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CC. Surgical repair of the syndrome of epicanthus inversus, blepharophimosis and ptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1964;71:510–516. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1964.00970010526015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft M, Cirstea IC, Voss AK, Thomas T, Goehring I, Sheikh BN, Gordon L, Scott H, Smyth GK, Ahmadian MR, Trautmann U, Zenker M, Tartaglia M, Ekici A, Reis A, Dörr HG, Rauch A, Thiel CT. Disruption of the histone acetyltransferase MYST4 leads to a Noonan syndrome-like phenotype and hyperactivated MAPK signaling in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3479–3491. doi: 10.1172/JCI43428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederer D, Grisart B, Digilio MC, Benoit V, Crespin M, Ghariani SC, Maystadt I, Dallapiccola B, Verellen-Dumoulin C. Deletion of KDM6A, a histone demethylase interacting with MLL2, in three patients with Kabuki syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009a;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009b;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake N, Mizuno S, Okamoto N, Ohashi H, Shiina M, Ogata K, Tsurusaki Y, Nakashima M, Saitsu H, Niikawa N, Matsumoto N. KDM6A point mutations cause Kabuki syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:108–110. doi: 10.1002/humu.22229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale BM, Kou Y, Liu L, Ma’ayan A, Samocha KE, Sabo A, Lin CF, Stevens C, Wang LS, Makarov V, Polak P, Yoon S, Maguire J, Crawford EL, Campbell NG, Geller ET, Valladares O, Schafer C, Liu H, Zhao T, Cai G, Lihm J, Dannenfelser R, Jabado O, Peralta Z, Nagaswamy U, Muzny D, Reid JG, Newsham I, Wu Y, Lewis L, Han Y, Voight BF, Lim E, Rossin E, Kirby A, Flannick J, Fromer M, Shakir K, Fennell T, Garimella K, Banks E, Poplin R, Gabriel S, DePristo M, Wimbish JR, Boone BE, Levy SE, Betancur C, Sunyaev S, Boerwinkle E, Buxbaum JD, Cook EH, Jr, Devlin B, Gibbs RA, Roeder K, Schellenberg GD, Sutcliffe JS, Daly MJ. Patterns and rates of exonic de novo mutations in autism spectrum disorders. Nature. 2012;485:242–245. doi: 10.1038/nature11011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niikawa N, Matsuura N, Fukushima Y, Ohsawa T, Kajii T. Kabuki make-up syndrome: a syndrome of mental retardation, unusual facies, large and protruding ears, and postnatal growth deficiency. J Pediatr. 1981;99:565–569. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(81)80255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan JA. Noonan syndrome. An update and review for the primary pediatrician. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1994;33:548–555. doi: 10.1177/000992289403300907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Roak BJ, Deriziotis P, Lee C, Vives L, Schwartz JJ, Girirajan S, Karakoc E, Mackenzie AP, Ng SB, Baker C, Rieder MJ, Nickerson DA, Bernier R, Fisher SE, Shendure J, Eichler EE. Exome sequencing in sporadic autism spectrum disorders identifies severe de novo mutations. Nat Genet. 2011;43:585–589. doi: 10.1038/ng.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oley C, Baraitser M. Blepharophimosis, ptosis, epicanthus inversus syndrome (BPES syndrome) J Med Genet. 1988;25:47–51. doi: 10.1136/jmg.25.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier N, Champagne N, Stifani S, Yang XJ. MOZ and MORF histone acetyltransferases interact with the Runt-domain transcription factor Runx2. Oncogene. 2002;21:2729–2740. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penttinen M, Koillinen H, Niinikoski H, Mäkitie O, Hietala M. Genitopatellar syndrome in an adolescent female with severe osteoporosis and endocrine abnormalities. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149A:451–455. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Castro JL, Pineda-Trujillo N, Valencia AV, Muñetón CM, Botero O, Trujillo O, Vásquez G, Mora BE, Durango N, Bedoya G, Ruiz-Linares A. Mutations in FOXL2 underlying BPES (types 1 and 2) in Colombian families. Am J Med Genet. 2002;113A:47–51. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders SJ, Murtha MT, Gupta AR, Murdoch JD, Raubeson MJ, Willsey AJ, Ercan-Sencicek AG, DiLullo NM, Parikshak NN, Stein JL, Walker MF, Ober GT, Teran NA, Song Y, El-Fishawy P, Murtha RC, Choi M, Overton JD, Bjornson RD, Carriero NJ, Meyer KA, Bilguvar K, Mane SM, Sestan N, Lifton RP, Günel M, Roeder K, Geschwind DH, Devlin B, State MW. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature. 2012;485:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah N, Rodriguez M, Louis DS, Lindley K, Milla PJ. Feeding difficulties and foregut dysmotility in Noonan’s syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1999;81:28–31. doi: 10.1136/adc.81.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson MA, Deshpande C, Dafou D, Vissers LELM, Woollard WJ, Holder SE, Gillessen-Kaesbach G, Derks R, White SM, Cohen-Snuijf R, Kant SG, Hoefsloot LH, Reardon W, Brunner HG, Bongers EMHF, Trembath RC. De novo mutations of the gene encoding the histone acetyltransferase KAT6B cause Genitopatellar syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:290–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szakszon K, Salpietro C, Kakar N, Knegt AC, Oláh E, Dallapiccola B, Borck G. De novo mutations of the gene encoding the histone acetyltransferase KAT6B in two patients with Say-Barber/Biesecker/Young-Simpson syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:884–888. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia M, Zampino G, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome: clinical aspects and molecular pathogenesis. Mol Syndromol. 2010;1:2–26. doi: 10.1159/000276766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udar N, Yellore V, Chalukya M, Yelchits S, Silva-Garcia R, Small K. Comparative analysis of the FOXL2 gene and characterization of mutations in BPES patients. Hum Mutat. 2003;22:222–228. doi: 10.1002/humu.10251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah M, Pelletier N, Xiao L, Zhao SP, Wang K, Degerny C, Tahmasebi S, Cayrou C, Doyon Y, Goh SL, Champagne N, Côté J, Yang XJ. Molecular architecture of quartet MOZ/MORF histone acetyltransferase complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6828–6843. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01297-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verloes A, Bremond-Gignac D, Isidor B, David A, Baumann C, Leroy MA, Stevens R, Gillerot Y, Héron D, Héron B, Benzacken B, Lacombe D, Brunner H, Bitoun P. Blepharophimosis-mental retardation (BMR) syndromes: A proposed clinical classification of the so-called Ohdo syndrome, and delineation of two new BMR syndromes, one X-linked and one autosomal recessive. Am J Med Genet A. 2006;140A:1285–1296. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vissers LELM, de Ligt J, Gilissen C, Janssen I, Steehouwer M, de Vries P, van Lier B, Arts P, Wieskamp N, del Rosario M, van Bon BWM, Hoischen A, de Vries BBA, Brunner HG, Veltman JA. A de novo paradigm for mental retardation. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1109–1112. doi: 10.1038/ng.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulto-van Silfhout AT, de Vries BBA, van Bon BWM, Hoischen A, Ruiterkamp-Versteeg M, Gilissen C, Gao F, van Zwam M, Harteveld CL, van Essen AJ, Hamel BCJ, Kleefstra T, Willemsen MAAP, Yntema HG, van Bokhoven H, Brunner HG, Boyer TG, de Brouwer APM. Mutations in MED12 cause X-linked Ohdo syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;92:401–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XJ, Ullah M. MOZ and MORF, two large MYSTic HATs in normal and cancer stem cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:5408–5419. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HC, Sloan JL, Scharer G, Brebner A, Quintana AM, Achilly NP, Manoli I, Coughlin CR, 2nd, Geiger EA, Schneck U, Watkins D, Suormala T, Van Hove JLK, Fowler B, Baumgartner MR, Rosenblatt DS, Venditti CP, Shaikh TH. An X-linked cobalamin disorder caused by mutations in transcriptional coregulator HCFC1. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahanova S, Meaney B, Łabieniec B, Verdin H, De Baere E, Nowaczyk MJM. Blepharophimosis-ptosis-epicanthus inversus syndrome plus: deletion 3q22.3q23 in a patient with characteristic facial features and with genital anomalies, spastic diplegia, and speech delay. Clin Dysmorphol. 2012;21:48–52. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e32834977f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlotogora J, Sagi M, Cohen T. The blepharophimosis, ptosis, and epicanthus inversus syndrome: delineation of two types. Am J Hum Genet. 1983;35:1020–1027. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]