Abstract

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of non-surgical abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) treatments for bleeding control, quality of life, pain, sexual health, patient satisfaction, additional treatments needed, and adverse events.

Data Sources

MEDLINE and Cochrane databases from inception to May 2012. We included randomized controlled trials of non-surgical treatments for AUB. Interventions included the levonorgestrel intrauterine system, combined oral contraceptives, progestins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antifibrinolytics. Gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists, danazol, and placebo were allowed as comparators.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened the 5846 citations and extracted eligible trials. Studies were assessed for quality and strength of evidence.

Tabulation, Integration, and Results

Twenty-six trials of eight different interventions met inclusion criteria. For the reduction of menstrual bleeding in women with AUB-E, the levonorgestrel intrauterine system, combined oral contraceptives, extended cycle oral progestins, tranexamic acid, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were all effective treatments. The levonorgestrel intrauterine system, combined oral contraceptives, and antifibrinolytics were all superior to luteal phase progestins. The levonorgestrel intrauterine system was superior to combined oral contraceptives and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Antifibrinolytics were superior to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for menstrual bleeding reduction. Data were limited on other important outcomes for women with AUB-E and on women with AUB-O.

Conclusion

Many non-surgical treatments for AUB are effective for reducing menstrual bleeding in women with AUB-E. Additional research is necessary to determine the effectiveness of treatments for other essential quality of life outcomes, and for other populations, including women with AUB-O.

INTRODUCTION

Women with AUB suffer diminished quality of life[1], lose work productivity[2], and utilize expensive medical resources.[2] AUB is a symptom of several different underlying conditions, which have been newly classified by the Menstrual Disorders Working Group of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO).[3] Although hysterectomy is considered the “definitive” treatment for both AUB-O (ovulatory dysfunction) and AUB-E (presumed endometrial dysfunction), many non-surgical options are also available and allow a woman to retain her ability to bear children and avoid a surgical intervention. Better characterization of the relative efficacy of commonly used non-surgical therapies will allow for improved patient counseling, facilitate informed decision-making, and reduce the burden of unnecessary procedures for both the patient and the health care system.

The Systematic Review Group of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS SRG) conducted this systematic review with the goal of producing an evidence-based guideline on non-surgical treatment decision-making for AUB-O and AUB-E. We specifically sought to compare the effectiveness of non-surgical abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) treatments for bleeding control, quality of life, pain, sexual health, patient satisfaction, additional treatments needed, and adverse events.

DATA SOURCES

The SGS SRG, including gynecologic surgeons and systematic review methodologists, performed a systematic search to identify RCTs comparing treatments for AUB. A working document defining parameters for a literature search was created.[4] We searched MEDLINE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from inception to May 14, 2012 for English language human studies. Details of the full search were reported in a previous publication.[5]

STUDY SELECTION

Participants of interest were defined as women receiving non-surgical interventions for AUB secondary to presumed endometrial dysfunction (AUB-E) or ovulatory dysfunction (AUB-O). Non-surgical interventions of interest included oral synthetic progestin (luteal phase and extended treatments), depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), combined oral contraceptives (OCPs), the levonorgestrel intrauterine system, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (mefenamic acid and naproxyn sodium), and antifibrinolytic treatment (tranexamic acid). Comparators of interest included all of the interventions of interest listed above plus placebo, danazol, gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists, and ethamsylate. Studies were excluded if they were not a RCT, if the study included a surgical comparator, or if the study included participants with AUB attributed to leiomyomata (AUB-L). Outcomes of interest for this review (bleeding, quality of life, pain, sexual health, patient satisfaction, additional treatment, and adverse events) were defined according to a structured process which has previously been published by the SGS SRG.[5]

Titles, abstracts, and full texts (when necessary) were screened for eligibility by two reviewers and any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. Data from studies were extracted by members of the SRG, most of whom had experience from prior systematic reviews. Individual extractions were confirmed by a second member and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. We collected data on study characteristics, participant characteristics, details on the interventions, length of follow-up, outcomes of interest measured, and how these outcomes were assessed. The classification of a study population (as AUB-E, AUB-O, or mixed/uncertain) was based on description of the study population within the individual manuscripts.

We assessed the methodological quality of each study using predefined criteria from a three-category system modified from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[6] Studies were graded as good (A), fair (B), or poor (C) quality based on the likelihood of biases and completeness of reporting. Grades for different outcomes could vary within the same study.

For each intervention, we generated an “evidence profile” by grading the quality of evidence for each outcome according to the Grades for Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system. The process considered the methodologic quality, consistency of results across studies, directness of the evidence, and imprecision or sparseness of evidence to determine an overall quality of evidence. Four quality rating categories were possible: high (A), moderate (B), low (C), and very low (D).[7]

We developed guideline statements incorporating the balance between benefits and harms of the compared interventions when the data were sufficient to support these statements. Each guideline statement was assigned an overall level of strength of the recommendation (1=“strong”, 2= “weak”) based on the quality of the supporting evidence and the size of the net benefit. The strength of a recommendation indicates the extent to which one can be confident that adherence to the recommendation will do more good than harm. The wording and its implications for patients, physicians, and policymakers are detailed in the Conclusions.

RESULTS

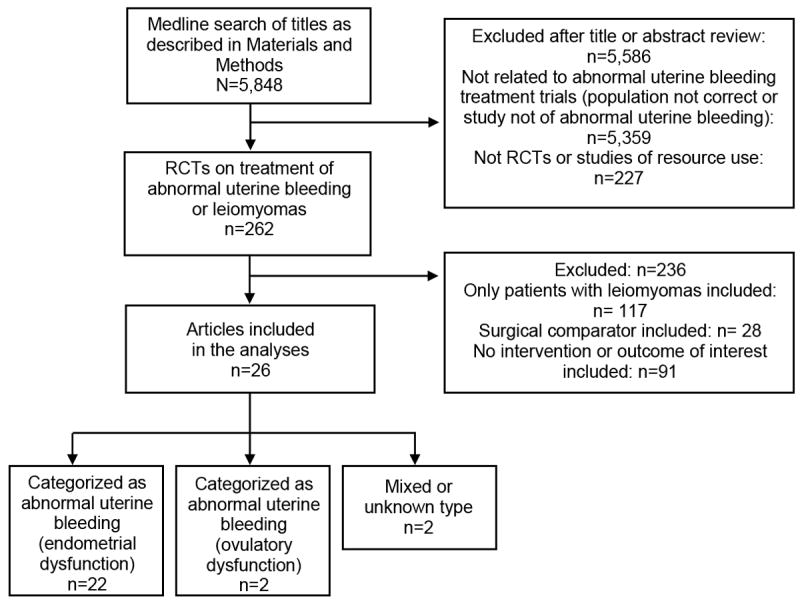

The search identified 5846 citations. Data were extracted and analyzed from the 26 studies that met all inclusion criteria for the systematic review. (Figure 1, Table 1),

Fig. 1.

Study selection process. Articles searched published between 1950 to May 14, 2012. RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Table 1.

Summary of studies, comparators, primary outcomes, sample size and power – Nonsurgicala

| Study (Author, year) Study Qualityb, N | Intervention and Comparator(s) | Primary Outcome (bolded) (Number of months/cycles treatment); List of other outcomes assessed (italics) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| POPULATION: AUB-E | |||

| Endrikat 2009[24] B, 42 | LNG-IUS versus OCPs | MBLc, d (12 months): LNG-IUS with greater reduction in MBL compared to OCP (83% versus 68%, p=0.002); Other: QOL | |

| Irvine 1998[29] B, 44 | LNG-IUS versus oral progestin (extended) | MBLc, d (3 months): No difference in MBL reduction detected between LNG-IUS and NET groups (94% versus 87%, NS, underpowered); Other: QOL, satisfaction, adverse events | |

| Kaunitz 2010[31] B, 165 | LNG-IUS versus oral progestin (luteal) | MBLc, e (6 months): LNG-IUS with greater reduction in MBL compared to MPA (71% versus 22%, p<0.001); Other: adverse events | |

| Reid 2005[35] B, 51 | LNG-IUS versus MFA | MBLc, e (6 cycles): LNG-IUS with greater reduction in MBL compared to MFA (95% versus 23%, p<0.001); Other: adverse events | |

| Shabaan 2011[36] B, 112 | LNG-IUS versus OCPs | MBLc, e (12 months): LNG-IUS with greater reduction in MBL compared to OCP (87% versus 35%, p=0.013); Other: QOL | |

| Fraser 1991[25] C, 45 | Cross-over study involving MFA, Naproxen, OCPs, and danazol | MBLd (2 cycles of MFA, 2 cycles no treatment, 2 cycles other treatment): Significant reduction in MBL seen with OCPs (43%, p<0.001) and danazol (49%, p=0.006). No within group differences seen when comparing MFA to the other treatment. Comparisons between groups not made; Other: none | |

| Fraser 2011[38] A, 231 | OCPs versus Placebo | “Complete response” to therapyc, e, f (7 cycles): 40.7% of OCP group and 1.6% of placebo group with “complete response”. OCPs greater MBL reduction. (69.4% versus 5.8%, p<0.0001); Other: adverse events | |

| Jensen 2011[30]g A, 190 | OCPs versus Placebo | “Complete response” to therapyc, e, f (7 cycles): 43.8% of the OCP group and 4.2% of placebo group with “complete response”. OCPs greater reduction in MBL. (64.2% versus 7.8%, p<0.001); Other: adverse events | |

| Bonduelle 1991[17] C, 30 | Oral progestin (luteal) versus Danazol | Bleeding intensity scored (3 cycles): Danazol with greater improvements in bleeding intensity score than NET. (p<0.02) No significant improvement in bleeding intensity seen in NET group; Other: pain, adverse events | |

| Cameron 1990[20] B, 32 | Oral progestin (luteal) versus MFA | MBLc, d (2 cycles): Significant reduction in MBL in both groups - 67% with NET and 52% with MFA. (difference NS); Other: pain, adverse events | |

| Higham 1993[28] B, 54 | Oral progestin (luteal) versus Danazol | MBLc, d (3 cycles): NET with a lesser reduction in MBL than either Danazol regimen (14% versus 40% and 26%, p=0.043 and p=0.017, respectively); Other: none | |

| Preston 1995[34] A, 46 | Oral progestin (luteal) versus TXA | MBLc, e (2 cycles): NET resulted in an increase in MBL and TXA resulted in a decrease in MBL (20% increase versus 45% decrease, p<0.0001);Other: QOL, sexual function, pain, adverse events | |

| Bonnar 1996[18] A, 76 | TXA versus MFA versus Ethamsylate | MBLe (3 cycles): TXA with greater reduction in MBL than MFA (54% versus 20%, p<0.001), both better than ethamsylate (p<0.001). No reduction in bleeding seen with ethamsylate; Other: pain, adverse events | |

| Calendar 1970[19] B, 16 | TXA versus Placebo | MBLc, d (3 cycles per treatment – cross-over study): TXA with greater reduction in MBL compared to placebo (38% versus 6%, p<0.05); Other: adverse events | |

| Edlund 1995[23] B, 91 | TXA (2 types) versus Placebo | MBLc, d (3 months): Reductions in MBL with BID dosing (41%) and QID dosing (33%) (difference NS), better than placebo (p<0.001); Other: adverse events | |

| Freeman 2011[37] A, 304 | TXA (2 doses) versus Placeb | MBLc, e (3 cycles): Greater reduction in MBL with 1.3 g TID and 0.65 g TID (38.6% and 26.1%) compared to placebo (1.9%, P<0.0001); Other: QOL, adverse events | |

| Lukes 2010[32] A, 196 | TXA versus Placebo | MBLc, e (6 cycles): Greater reduction in MBL in TXA group (40.4%) than placebo (8.2%, p<0.001); Other: QOL, adverse events | |

| Nilsson 1965[33] B, 37 | Epsilon Amino Caproic Acid versus Placebo | MBLd (2 cycles of each treatment, crossover): Participants experienced a 62% decrease in MBL when treated with EACA when compared to placebo. (p<0.001); Other: adverse events | |

| Chamberlain 1991[21] B, 44 | MFA versus Ethamsylate | MBLc, d (3 cycles): No difference detected between treatments. Reduction in MBL of 24% with MFA and 20% with ethamsylate; Other: adverse events | |

| Dockeray 1989[22] A, 40 | MFA versus Danazol | MBLc, d (2 cycles): Greater reduction in MBL in danazol group than MFA group (60% versus 20%, p<0.001); Other: pain, adverse events | |

| Hall 1987[27] B, 40 | MFA versus Naproxen | MBLd (2 cycles per treatment – cross-over study): Both treatments with significant reduction in MBL from baseline (MFA 46-47%, Naproxen 44-48%). No difference between groups; Other: adverse events | |

| Fraser 1981[26] h C, 85 | MFA versus Placebo | MBLd (2 cycles per treatment, cross-over study): Significantly lower MBL seen with MFA when compared to MBL with placebo (MBL 28% lower, p<0.001); Other: pain, adverse events | |

| POPULATION: AUB-O, Mixed, Uncertain | |||

| Davis 2000[39] B, 201 (AUB-O) | OCP versus Placebo | “Resolution of abnormal bleeding”e (3 cycles): “Investigator assessment of resolution” and “patient assessment of resolution” greater in OCP group (81% and 87%, respectively) than placebo (36% and 45%, respectively). (p<0.001 for both); Other: bleeding, QOL, sexual function | |

| Cetin 2009[40] C, 58 (AUB-O) | OCP versus OCP plus GnRH agonist | Primary outcome uncleard (6 months): GnRH plus group used fewer sanitary products than OCP alone group (47 versus 52, p<0.05); Other: bleeding, satisfaction, additional treatment, adverse events | |

| Kucuk 2008[41] B, 132 (Mixed) | LNG-IUS versus oral progestin (continuous) versus DMPA IM | PBAC scored and Mean duration of menses in daysd (2 cycles): No difference in duration of bleeding between groups. LNG-IUS with greater reduction in MBL (73%) compared to MPA (33%) and DMPA (49%), p <0.01 for both. Difference between MPA and DMPA NS; Other: adverse events | |

| Lahteenmaki 1998[42] C, 56 (Uncertain) | LNG-IUS versus “Control” (not specified) | Decision to continue current therapy versus hysterectomye (6 months): Greater proportion in LNG-IUS group cancelled hysterectomy (64% versus 14%, p<0.001); Other: Bleeding, QOL, sexual function | |

Abbreviations used in the table: OCP = combined oral contraceptive; QOL= quality of life; DMPA = Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; LNG-IUS = Levonorgestrel intrauterine system; MBL = mean blood loss; MFA = Mefenamic acid; PBAC = pictorial blood loss assessment chart; TXA = tranexamic acid; GnRH: Gonadotropin releasing hormone; NS= Not significant

Study Quality Rating - Determined by rating the quality of the study, the quality of the assessment of the particular outcome, the consistency of results across studies, the directness (applicability of results to population of interest), imprecision, and sparseness of evidence. A - Good quality: no obvious biases or reporting errors, complete reporting of data. B - Fair quality: problems with study/paper unlikely to cause major bias. C - Poor quality: cannot exclude possible significant biases, poor methods, incomplete data, reporting errors.

Greater than 80 ml mean blood loss at baseline required for study eligibility

Study either not powered to detect a difference in the outcome or no power calculation described

Study powered to detect difference in this outcome

Outcome: complete response to therapy defined by a composite of absence of all qualifying conditions

Mixed population with mean blood loss greater than 80 ml. 95% with “regular menses” therefore included in the AUB-E group for analyses

Mixed population with 82% AUB-E and 18% AUB-O, included in the AUB-E group for analyses

AUB-E

Twenty-two studies included women predominantly with AUB-E. [8-29] Three studies [16, 19, 21] included both AUB-E (82%, 95%, 86%) and AUB-O (18%, 5%, 14%) patients; these studies were included in the AUB-E category as the majority of patients fit this description. Seventeen of these studies required that patients objectively lose greater than 80 milliliters menstrual blood loss per cycle in order to be eligible for study participation.[10-15, 18-23, 25-29] Five studies included a levonorgestrel intrauterine system arm [15, 20, 22, 26, 27], 5 studies included a OCP arm [15, 16, 21, 27, 29], 5 studies included a luteal progestin arm[8, 11, 19, 22, 25], 1 study included an extended oral progestin arm[20], 8 studies included an NSAID arm[9, 11-13, 16-18, 36], 7 studies included an antifibrinolytic arm (tranexamic acid, tranexamic acid prodrug, or epsilon amino caproic acid) [9, 10, 14, 23-25, 28]. Studies ranged in quality, and the quality of individual studies are noted in Table 1. Sample sizes ranged from 16 to 304 participants.[10, 28]

Bleeding

All 22 AUB-E studies reported on bleeding outcomes in terms of menstrual blood loss. All but one [8, 34]calculated the change in menstrual blood loss quantitatively using the objective alkaline-hematin method [18-23, 25-38] and/or the semi-objective pictorial blood assessment chart [15, 26, 27, 35]. Data are presented in Table 1.

Five AUB-E studies investigated the effectiveness of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. All of these studies required participants to lose ≥80 milliliters menstrual blood loss per cycle at baseline in order to be eligible. Two of these compared the levonorgestrel intrauterine system to OCPs and found that at 12 months, decrease in menstrual blood loss was significantly greater using the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. (83% versus 68%, p=0.002 and 87% versus 35%, p=0.013) [15, 27] The levonorgestrel intrauterine system resulted in significantly greater blood loss reduction than luteal phase oral progestin[22] and the NSAID, mefenamic acid[26]. Irvine et al compared the levonorgestrel intrauterine system to extended oral progestin; both treatment groups showed significant reductions in menstrual blood loss at 3 months (94% versus 87%) but no difference was detected between groups.[20] However, based on the sample size calculation, the study was underpowered.

In addition to being compared to the levonorgestrel intrauterine system, OCPs were also directly compared to mefenamic acid [16] and to placebo [21, 29]. Both mefenamic acid and OCPs reduced menstrual blood loss (38% and 42%, respectively) but the difference between groups was not significant.[25] Two similar trials showed that OCPs resulted in a greater reduction in menstrual blood loss compared with placebo.[21, 29]

Luteal phase oral progestins (administered for 10 days per month) have been compared to the levonorgestrel intrauterine system[22], tranexamic acid[25], and NSAIDs[11]. While tranexamic acid use resulted in a 45% reduction in menstrual blood loss over 2 cycles, luteal phase oral progestins resulted in a 20% increase in menstrual blood loss (p<0.0001). When this same regimen of oral progestin was compared to mefenamic acid, both treatment groups demonstrated significant reductions in blood loss from baseline over 2 cycles (67% and 52%, respectively) but were not significantly different from each other (n=32).[11]

In addition to head-to-head comparison with luteal phase oral progestin (above)[34], tranexamic acid (an antifibrinolytic) has been compared to mefenamic acid and to placebo.[9, 10, 14, 23, 24, 28] Tranexamic acid had a superior reduction in menstrual blood loss over 3 cycles compared to mefenamic acid (54% versus 10%, p<0.001). [9] Antifibrinolytics were compared to placebo and in studies cases were superior for the reduction of blood loss.[10, 14, 23, 24, 28]

Comparisons of NSAIDs to other relevant interventions are described above.[ 9, 11-13, 16,20, 25, 35] Mefenamic acid was also compared to placebo [17] and another NSAID (naproxen sodium) [18]. Mefenamic acid use resulted in significantly greater reduction in blood loss than placebo. [17] While both mefanamic acid and naproxen sodium demonstrated reductions in blood loss compared to baseline, there were no significant differences between the two. [18]

Synthesizing these studies, we found net benefits for levonorgestrel intrauterine system when compared to OCPs, luteal phase progestins, and mefanamic acid for the reduction in menstrual blood loss in women with AUB-E (moderate quality evidence). Moderate quality evidence also suggested net benefits to the use of OCPs and antifibrinolytics over placebo. Low quality evidence suggested net benefits to the use of NSAIDs over placebo. We also found net benefits for the use of antifibrinololytics over luteal phase oral progestins (very low quality evidence) and NSAIDs (moderate quality evidence) for the reduction of menstrual bleeding. Based on the available literature, we could not determine whether there was a difference between OCPs and NSAIDS or luteal progestins and NSAIDs.

Quality of life, Sexual Function, Satisfaction, Pain, and Additional treatment

Other outcomes of interest for this systematic review were either reported infrequently or inconsistently across 11 studies. Quality of life (QOL) was measured in 6 studies[15, 20, 23, 25, 27, 28], sexual function in 1 study[25], satisfaction in 1 study[20], pain in 6 studies[8, 9, 11, 13, 16, 25], and additional treatment in no studies. For these studies, evidence profiles were generated and data were summarized. Because of the limited number of studies and the limited quality of the outcomes, clinical practice guidelines for these outcomes were not generated.

Treatment with both the levonorgestrel intrauterine system and OCPs was associated with QOL improvement. While treatment with levonorgestrel intrauterine system resulted in greater QOL improvements initially, this difference was not observed at 1 year.[15] Tranexamic acid was shown to improve both physical function and social function QOL outcomes.[23, 25, 28] No QOL improvements were reported for luteal phase progestins.[25] With respect to pain, significant improvement was reported for patients with dysmennorhea using NSAIDs and tranexamic acid.[14, 17], while luteal phase progestin and tranexamic acid did not reach significance in one study[25]. Luteal phase progestin, tranexamic acid and NSAIDs may favorably impact on abdominal pain and back ache.[8, 11, 25]

Other Populations of women with AUB: AUB-O, mixed etiologies, uncertain etiologies

Only 2 studies included women predominantly with AUB-O [30,31] and 2 studies had “mixed or uncertain” etiologies of AUB [32,33]. Therefore, evidence profiles were not generated for these populations. The main results of these four studies are summarized in Table 1.

Adverse events

Twenty of the 26 studies reported on adverse events. Adverse events were inconsistently ascertained, recorded, and reported and therefore could not be tabulated or compared between interventions or studies. To highlight the inconsistency in reporting across studies, for the adverse event “bloating or weight gain”, one study reported a prevalence of 67% among participants using luteal oral progestin[8] while two other studies using the same intervention reported a prevalence that ranged from 0-6%.[22, 24]

Conclusion

Abnormal uterine bleeding is a prevalent symptom among women seeking gynecologic care. Based on available RCTs, we found that the levonorgestrel intrauterine system, OCPs, extended cycle oral progestins, tranexamic acid, and NSAIDs were all effective treatments for the reduction of menstrual blood loss in women with AUB-E and that the levonorgestrel intrauterine system, OCPs, and antifibrinolytics were all superior to luteal phase progestins. We were unable to make other definitive conclusions on the effectiveness of these commonly used treatments relative to one another for other essential outcomes (quality of life, sexual function, pain, satisfaction, additional treatment, or adverse events) or for other populations (AUB-O or mixed populations) because of limited RCTs, limited reporting on these outcomes, or suboptimal data quality obtained within available studies.

Based on the evidence, the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons’ Systematic Review Group developed Clinical Practice Guidelines for non-surgical treatment for AUB. Guidelines were only developed for the outcome of “reduction in menstrual bleeding” for populations of women with AUB-E (heavy and regular bleeding), as this was the only population and outcome for which there was enough good quality data to generate meaningful guidelines. (Table 2) Each Clinical Practice Guideline received a “grade” in two parts: 1) The strength of the recommendation (1=“we recommend” or 2=“we suggest”), and 2) The quality of the evidence (A, B, C, D). Based on the quality of the evidence for individual comparisons, some of our guideline statements are presented as recommendations and others are presented as suggestions.

Table 2.

Medical management of abnormal uterine bleeding. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the reduction in menstrual bleeding: For the reduction in mean blood loss in women with heavy menstrual bleeding presumed secondary to AUB-E a who desire medical therapy and have no contraindications nor objection to the use of interventions A or B…

| Intervention A | Intervention B | Preferred intervention (level of evidence) | Clinical Practice Guideline Statements |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| LNG-IUS | OCP | LNG-IUS (1B) | We recommend the use of LNG-IUS over OCPs, luteal phase progestins, and NSAIDs. |

| Luteal oral progestin | LNG-IUS (1B) | ||

| Extended oral progestin | Either (2C) | ||

| Antifibrinolytics | No direct comparisonb | ||

| NSAID | LNG-IUS (2C) | ||

|

| |||

| OCP | LNG-IUS | LNG-IUS (1B) | We recommend the use of LNG-IUS over OCPs. We suggest the use of OCPs over luteal phase progestins. |

| Luteal oral progestin | No direct comparisonb | ||

| Extended oral progestin | No direct comparisonb | ||

| Antifibrinolytics | No direct comparisonb | ||

| NSAID | Insufficient datac (2D) | ||

|

| |||

| Luteal phase oral progestin | LNG IUS | LNG-IUS (1B) | We recommend the use of LNG IUS over luteal phase progestins. We suggest the use of OCPs and antifibrinolytics over luteal phase progestins. |

| OCPs | No direct comparisonb | ||

| Extended oral progestin | No direct comparisonb | ||

| Antifibrinolytics | Antifibrinolytic (2D) | ||

| NSAID | Insufficient datac (2C) | ||

|

| |||

| Extended cycle oral progestin | LNG IUS | Either (2C) | There are insufficient data upon which to make suggestions |

| OCPs | No direct comparisonb | ||

| Luteal oral progestin | No direct comparisonb | ||

| Antifibrinolytics | No direct comparisonb | ||

| NSAID | No direct comparisonb | ||

|

| |||

| Antifibrinolytics | LNG IUS | No direct comparisonb | We suggest the use of antifibrinolytics over luteal phase progestins and NSAIDs. |

| OCPs | No direct comparisonb | ||

| Extended oral progestin | Antifibrinolytic (2D) | ||

| Luteal oral progestin | No direct comparisonb | ||

| NSAID | Antifibrinolytic (1B) | ||

AUB-E defined by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics classification system (ref) as heavy and regular bleeding secondary to hemostatic dysfunction

No studies reviewed included a direct comparison of treatment A vs. B

Data are available for these comparisons (A vs. B) but are insufficient to recommend A or B for control of bleeding.

LNG-IUS, Levonorgestrel intrauterine system; OCP, combined oral contraceptive; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

The strengths of this study are the comprehensive nature of the literature review and the clear and standardized methodology used for guideline development. Since the Guidelines on Heavy Menstrual Bleeding published by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom five years ago, [36] 9 new RCTs on non- surgical treatments for AUB have been published and were included in our review, therefore providing new evidence towards clinical practice guidelines.[15, 21-23, 27-29, 31, 32] A national survey of U.S. gynecologists suggested that obstetricians and gynecologists in the United States may not be accessing lengthy evidence based reviews, such as the ones conducted by NICE and the Cochrane collaboration.[37] Additionally in that study, only 23% of respondents were aware that luteal phase progestins were ineffective treatments for AUB-E. [37] It is our hope that our more concise review will further disseminate the evidence on effective treatments for AUB and help to improve the management of women with this symptom.

In clinical practice, the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding are based upon “patient experience”, the woman’s personal assessment of her blood loss and its impact on her life. [38] A limitation of our study is that it falls short for making suggestions and guidelines for the outcomes likely most meaningful for women: “patient experience” and bleeding-related quality of life because, traditionally, research on heavy menstrual bleeding has focused on measured menstrual blood loss as the main study outcome. [39] Other limitations include difficulty determining the exact study population and the effect of sponsorship and publication bias on the body of literature. Nineteen of the 26 studies were sponsored or conducted by the treatment’s manufacturer.

We reviewed RCTs on seven different nonsurgical treatments for AUB-E and AUB-O. A limitation of our conclusions is that they are based on relatively few RCTs and that women who participate in RCTs may differ from the population of women suffering from AUB. Despite the number of treatments available and the prevalence of AUB, we identified only 26 RCTs comparing these treatments, resulting in sparse comparisons between most interventions, and only two of these studies specifically addressed women with AUB-O. Given the prevalence of AUB and the possibility that treatments which are effective for AUB-E may not be effective for AUB-O, more research on this population is necessary. In addition, of these 26 studies, 17 (65%) included menstrual blood loss greater than 80 milliliters as an eligibility criteria for participation in the study which may not be applicable to the general population of women seeking treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding.[38] Including women who self-report AUB in studies and measurement of bleeding-related quality of life as a main outcome should be high priorities of research in this area. Also, some treatments have not yet been compared in head-to-head clinical trials, so it is unknown which treatments are most effective.

AUB is a prevalent symptom that has an enormous impact on the quality of life of women and healthcare costs. This review provides a concise distillation of the available evidence on non-surgical treatment for this important problem that gynecologists treat on a regular basis. Although there are limitations to the body of literature on this symptom, this review and clinical practice guidelines provide up-to-date information on the relative effectiveness of AUB treatments commonly used in clinical practice and will assist with clinical decision-making and setting priorities for research on this important symptom.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Supported by the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, who provided administrative and financial support for the Systematic Review Group’s meetings and consultants, including Dr. Balk (www.sgsonline.org). Other support: Dr. Matteson is supported by K23HD057957, Dr. Vivian Sung is supported by K23HD060665

Footnotes

Author Conflicts of Interest: none

References

- 1.Jenkinson C, Peto V, Coulter A. Making sense of ambiguity: evaluation in internal reliability and face validity of the SF 36 questionnaire in women presenting with menorrhagia. Qual Health Care. 1996;5(1):9–12. doi: 10.1136/qshc.5.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Z, Doan QV, Blumenthal P, Dubois RW. A systematic review evaluating health-related quality of life, work impairment, and health care costs and utilization in abnormal uterine bleeding. Value Health. 2007;10(3):173–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munro MG, Critchley HO, Fraser IS. The FIGO classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding: Malcolm G. Munro, Hilary O.D. Crithcley, Ian S. Fraser, for the FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2011;113(1):1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(5):380–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahn DD, Abed H, Sung VW, Matteson KA, Rogers RG, Morrill MY, et al. Society of Gynecologic Surgeons-Systematic Review Group. Systematic review highlights difficultyinterpreting diverse clinical outcomes in abnormal uterine bleeding trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(3):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, Treadwell JR, Reston JT, Bass EB, et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(5):513–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkins D, Eccles M, Flottorp S, Guyatt GH, Henry D, Hill S, et al. GRADE Working Group. Systems for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations I: critical appraisal of existing approaches The GRADE Working Group. BMC Health Serv Res. 2004;4(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonduelle M, Walker JJ, Calder AA. A comparative study of danazol and norethisterone in dysfunctional uterine bleeding presenting as menorrhagia. Postgrad Med J. 1991;67(791):833–6. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.67.791.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonnar J, Sheppard BL. Treatment of menorrhagia during menstruation: randomised controlled trial of ethamsylate, mefenamic acid, and tranexamic acid. Brit Med J. 1996;313(7057):579–82. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7057.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callender ST, Warner GT, Cope E. Treatment of menorrhagia with tranexamic acid. A double-blind trial. Brit Med J. 1970;4(5729):214–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5729.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron IT, Haining R, Lumsden MA, Thomas VR, Smith SK. The effects of mefenamic acid and norethisterone on measured menstrual blood loss. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76(1):85–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamberlain G, Freeman R, Price F, Kennedy A, Green D, Eve L. A comparative study of ethamsylate and mefenamic acid in dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;98(7):707–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1991.tb13460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dockeray CJ, Sheppard BL, Bonnar J. Comparison between mefenamic acid and danazol in the treatment of established menorrhagia. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96(7):840–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1989.tb03325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edlund M, Andersson K, Rybo G, Lindoff C, Astedt B, von Schoultz B. Reduction of menstrual blood loss in women suffering from idiopathic menorrhagia with a novel antifibrinolytic drug (Kabi 2161) Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102(11):913–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb10881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Endrikat J, Shapiro H, Lukkari-Lax E, Kunz M, Schmidt W, Fortier M. A Canadian, multicentre study comparing the efficacy of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system to an oral contraceptive in women with idiopathic menorrhagia. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31(4):340–7.16. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser IS, McCarron G. Randomized trial of 2 hormonal and 2 prostaglandin- inhibiting agents in women with a complaint of menorrhagia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;31(1):66–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1991.tb02769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser IS, Pearse C, Shearman RP, Elliott PM, McIlveen J, Markham R. Efficacy of mefenamic acid in patients with a complaint of menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58(5):543–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall P, Maclachlan N, Thorn N, Nudd MW, Taylor CG, Garrioch DB. Control of menorrhagia by the cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors naproxen sodium and mefenamic acid. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1987;94(6):554–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb03150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higham JM, Shaw RW. A comparative study of danazol, a regimen of decreasing doses of danazol, and norethindrone in the treatment of objectively proven unexplained menorrhagia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(5):1134–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(93)90269-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irvine GA, Campbell-Brown MB, Lumsden MA, Heikkilä A, Walker JJ, Cameron IT. Randomised comparative trial of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system and norethisterone for treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105(6):592–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen JT, Parke S, Mellinger U, Machlitt A, Fraser IS. Effective treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding with estradiol valerate and dienogest: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):777–87. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182118ac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaunitz AM, Bissonnette F, Monteiro I, Lukkari-Lax E, Muysers C, Jensen JT. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or medroxyprogesterone for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(3):625–32. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ec622b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, Gersten JK, Hecht BR, Edlund M, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):865–75. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f20177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson L, Rybo G. Treatment of menorrhagia with epsilon aminocaproic acid. A double blind investigation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1965;44(3):467–73. doi: 10.3109/00016346509155880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Preston JT, Cameron IT, Adams EJ, Smith SK. Comparative study of tranexamic acid and norethisterone in the treatment of ovulatory menorrhagia. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1995;102(5):401–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb11293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reid PC, Virtanen-Kari S. Randomised comparative trial of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system and mefenamic acid for the treatment of idiopathic menorrhagia: a multiple analysis using total menstrual fluid loss, menstrual blood loss and pictorial blood loss assessment charts. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112(8):1121–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaaban MM, Zakherah MS, El-Nashar SA, Sayed GH. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system compared to low dose combined oral contraceptive pills for idiopathic menorrhagia: a randomized clinical trial. Contraception. 2011;83(1):48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman EW, Lukes A, VanDrie D, Mabey RG, Gersten J, Adomako TL. A dose-response study of a novel, oral tranexamic formulation for heavy menstrual bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(4):319.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraser IS, Römer T, Parke S, Zeun S, Mellinger U, Machlitt A, et al. Effective treatment of heavy and/or prolonged menstrual bleeding with an oral contraceptive containing estradiol valerate and dienogest: a randomized, double-blind Phase III trial. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(10):2698–708. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis A, Godwin A, Lippman J, Olson W, Kafrissen M. Triphasic norgestimate-ethinyl estradiol for treating dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96(6):913–20. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cetin NN, Karabacak O, Korucuoglu U, Karabacak N. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog combined with a low-dose oral contraceptive to treat heavy menstrual bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009;104(3):236–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Küçük T, Ertan K. Continuous oral or intramuscular medroxyprogesterone acetate versus the levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system in the treatment of perimenopausal menorrhagia: a randomized, prospective, controlled clinical trial in female smokers. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2008;35(1):57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lähteenmäki P, Haukkamaa M, Puolakka J, Riikonen U, Sainio S, Suvisaari J, et al. Open randomised study of use of levonorgestrel releasing intrauterine system as alternative to hysterectomy. Brit Med J. 1998;316(7138):1122–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7138.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haynes P, Hodgson H, Anderson AB, Turnbull AC. Measurement of menstrual blood loss in patients complaining of menorrhagia. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1977;84(10):763–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1977.tb12490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higham JM, O’Brien PM, Shaw RW. Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart. Brit J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97(8):734–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb16249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Institute of Clinical Excellence. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Clinical Guidelines on Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matteson KA, Anderson BL, Pinto SB, Lopes V, Schulkin J, Clark MA. Practice patterns and attitudes about treating abnormal uterine bleeding: a national survey of obstetricians and gynecologists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(4):321 e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warner PE, Critchley HO, Lumsden MA, Campbell-Brown M, Douglas A, Murray GD. Menorrhagia II: is the 80-mL blood loss criterion useful in management of complaint of menorrhagia? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(5):1224–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hallberg L, Hogdahl AM, Nilsson L, Rybo G. Menstrual blood loss--a population study. Variation at different ages and attempts to define normality. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1966;45(3):320–51. doi: 10.3109/00016346609158455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]