Abstract

We recently reported that a DNA plasmid coding p62-SQSTM1 acts as an effective anti tumor vaccine against both transplantable mouse tumors and canine spontaneous mammary neoplasms. Here we report the unexpected finding that intramuscular delivery of p62 DNA exerts a powerful anti-osteoporotic activity in a mouse model of inflammatory bone loss (i.e, ovariectomy) by combining bone-sparing and osteo-synthetic effects. Notably, the suppression of osteoporosis by p62DNA was associated with a sharp down-regulation of master inflammatory cytokines, and up-regulation of endogenous p62 protein by bone-marrow stromal cells. The present data provide a solid rational to apply p62 DNA vaccine as a safe, new therapeutic for treatment of inflammatory related bone loss diseases.

Keywords: p62/SQSTM1, chronic inflammation, osteoporosis, immunotherapy

INTRODUCTION

The adapter protein p62 (also known as sequestosome1/SQSTM1) is a multifunctional molecule involved in a myriad of cellular processes that modulate proliferation, cell death, inflammation and immune response [1]. Further studies demonstrated that p62 plays an important role in patho-physiology of human diseases including neurodegenerative diseases, lung disease, obesity, insulin resistance, cancer, and Paget's disease of bone [2]. Since p62 holds a key role in innate immunity by regulating inflammatory signaling cascades, the hypothesis that deregulated p62 is linked to the chronic allostasis that foster dreadful inflammatory disorders is gaining ground [3, 4]. Accordingly, p62 has been envisaged as a potential target in cancer, infectious and inflammatory diseases [5].

We first reported that p62 could be a target for cancer immunotherapy. Indeed, we provide evidence that DNA plasmid-encoded human p62 triggered effective anti-tumor/antimetastatic activities in four models of allogenic mouse tumors (i.e. melanoma, lung carcinoma, sarcoma, and breast cancer) [6]. We also demonstrated that p62 DNA plasmid when administered in neo-adjuvant (pre-operative) setting decreased and/or stabilized growth of advanced lesions in canine mammary tumors [7].

Although there are no in vivo data regarding the role of exogenous p62 in inflammation, there are some in vitro evidence suggesting that p62 may act as an important regulator of cytokine expression [8–11]. In example, in activated macrophages p62 overexpression and underexpression clearly lead to opposite effects pointing to the inhibitory role of p62 in cytokine expression, thus providing a mechanism by which p62 controls excessive inflammatory responses [11]. Of much interest, is a recent report that highlights the anti-inflammatory tumor suppressor potential of p62, as its down-regulation in the tumor stroma fosters an inflammatory response that enhances tumorigenesis both in vitro and in vivo [12].

The existence of a causal link between inflammation and p62 is further supported by the observation that the lack of a p62 (or macroautophagy) contributes to inflammation in aging [4]. The term “inflammaging” was coined at the beginning of this century by Franceschi et al. [13] to refer to a low-grade pro-inflammatory phenotypes which accompany aging in mammals and that predispose the organism to develop several age-related diseases.

Osteoporosis is, by far, the leading age-related disease affecting mostly women after onset of menopause. Because estrogens contribute to bone-sparing activity by inhibition of bone remodeling (coupled with a balancing effect on bone formation and resorption), decreased levels of circulating estrogen at menopause results in a rapid bone loss [14]. Further observations indicate that the estroprivic bone loss reflects increased number of T cells, that in concert with macrophages and bone marrow-derived stromal cells promote the release of pro inflammatory cytokines (e.g TNF-α and IL-1β beta, IL-6, and RANK-L) that propel osteoclastogenesis, and thereby bone erosion [15] (See Supplementary Figure 1). Finally, the strong link between inflammation and osteoporosis is further evidenced by clinical studies showing that chronic inflammatory diseases of almost any cause, are associated with bone loss (osteopenia) [16].

Based on the putative anti-inflammatory role of p62, together with the fact that p62 physiologically controls osteoclastogenesis and bone remodeling [17], we hypothesized that p62 DNA vaccine could compensate for osteoporosis. To test the hypothesis we carried out experiments by injecting p62 DNA in ovariectomized (OVX) mice. Since ovariectomy induces chronic inflammation in mice and in humans [18], this animal model is widely utilized to study premature aging [19], and to test experimental anti-osteoporotic drugs and biologicals [20].

The results shown below are representative of those obtained by in independent trials carried out both in preventive and therapeutic settings.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

p62 DNA administration prevents osteoporosis in OVX mice

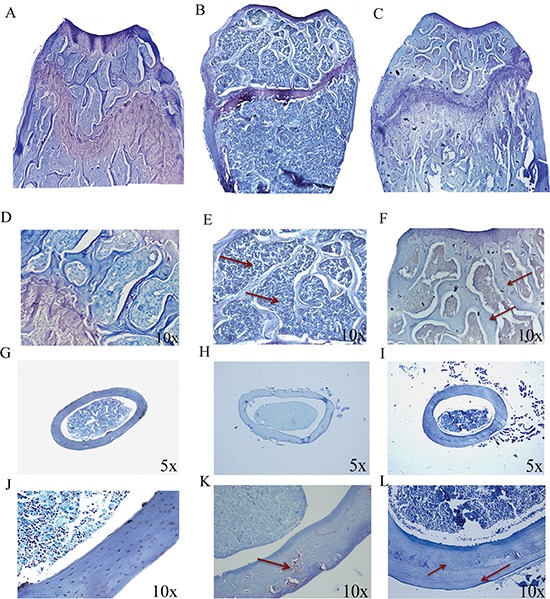

To evaluate whether p62 vaccine was able to prevent osteoporosis, groups of mice were first injected either with experimental (p62DNA) or reference plasmids (pcDNA 3.1) and then ovariectomized (OVX). For each trial a control group of sham operated (SO) mice was included (see M&M for details). Two months after surgery mice were sacrificed, and the collected long bones subjected to histological examination. As expected, the metaphyseal regions of the distal femurs from pcDNA3.1-OVX mice displayed classical osteoporotic features characterized by significant bone loss and thinned disconnected trabecular structure (Figure 1B, 1E). On the other hand, p62-OVX bones (Figure 1C, 1F) showed a micro-architecture essentially indistinguishable to that seen in SO mice (Figure 1A, 1D). Moreover, examination of cross sections femur diaphysis from p62DNA-OVX mice revealed (at variance of those obtained from reference plasmids treated mice) an enhanced anabolic - osteoblastic activity as evidenced by new cortical bone apposition suggesting an anabolic action of p62 treatment. (Figure 1G–1L).

Figure 1. p62 DNA prevents osteoporosis.

Representative reconstructions of metaphyseal regions of the distal femurs from sham operated (A, D), pcDNA3.1-OVX (B, E) and p62 DNA-OVX mice (C, F). Arrows indicated the thinner and reduced trabecular network in pcDNA3.1-OVX mice (E) compared with that observed in p62 DNA-OVX mice (F) Representative section of femur mid diaphysis from sham operated (G, J), pcDNA3.1-OVX (H, K) and p62 DNA-OVX mice (I, L). Arrows indicated cortical bone porosity in pcDNA3.1-OVX mice (K) and the new bone apposition in p62 DNA-OVX mice (L) Magnifications: 10 × (D, E, F, J, K, L), 5 × (G, H. I).

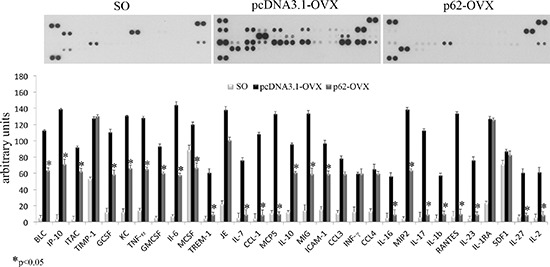

Fully consistent with the morphological findings are the biochemical results obtained by utilizing bone marrow stromal cells (BMCs) retrieved from plasmids pre-treated mice. In these experiments BMCs were flushed from the bone cavities, and cultured for 3 days. Afterwards, both supernatants and cells were collected and analyzed respectively either for the release of inflammatory cytokines, or for expression of osteogenic markers. As illustrated in Figure 2, we observed that the marked up-regulation and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by BMCs from OVX compare to SO operated mice was drastically suppressed by p62-DNA pretreatment. The inhibitory effect of p62 DNA extended to an array of cytokines such as TNFα, IL-6, IL-1b IL-17, all known to be essential inducers of inflammatory diseases and bone loss [21]. As far as the capability of p62DNA to induce new bone formation is concerned, western blotting analysis of p62-OVX BMCs extracts indicated a strong and selective increase of osteogenic markers, such as Runx2 and Osterix transcription factors [22]. An increase of Runx2 and Osterix, although weaker, was also found in p62 SO mice (Figure 3).

Figure 2. p62 DNA pretreatment decreases pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines release in OVX mice.

Cytokines and chemokines release was analyzed in medium from bone marrow cultures obtained by sham operated, p62 or pcDNA 3.1 pre-treated OVX mice. (*p < 0.05).

Figure 3. p62 DNA increases osteogenic markers.

Total bone marrow cell populations were obtained from long bones of sham operated, pcDNA3.1-OVX and p62 DNA-OVX mice and were examined by Western blotting for Runx2 and osterix expression. (*p < 0.05).

p62 DNA as an anti-osteoporosis therapeutic

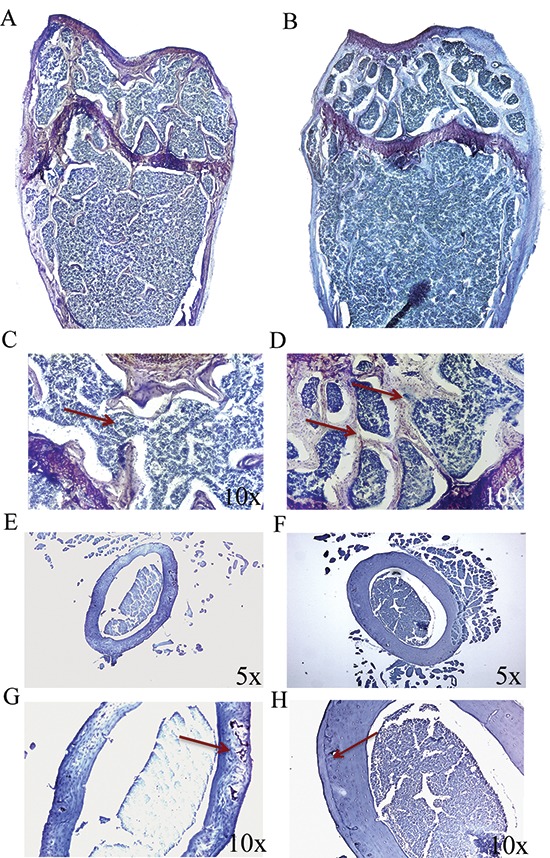

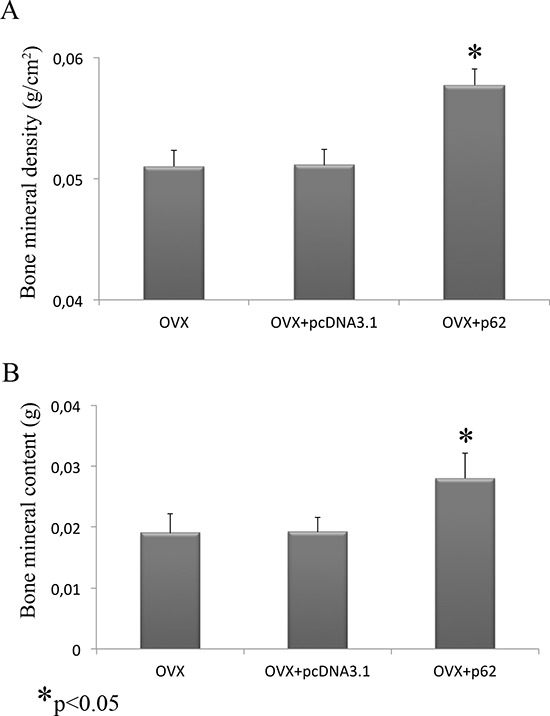

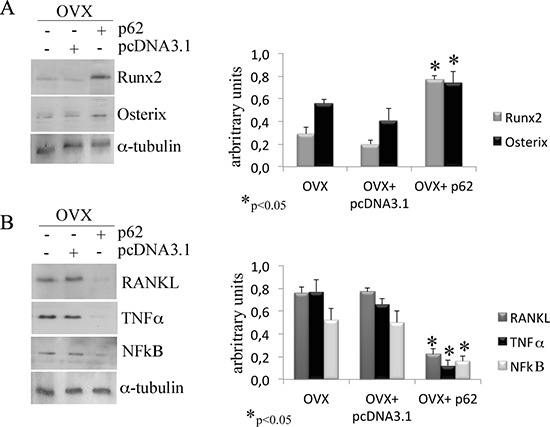

After establishing that p62 DNA vaccine demonstrates robust effects not only in preventing osteoporosis but also in inducing new bone formation, we assessed the therapeutic potential of p62 DNA in case of established osteoporosis. In these trials, mice were ovariectomized and, after two months, injected either with p62-DNA or reference plasmids (see M&M for details). Two months after last plasmids injections, bones were collected and histologically evaluated. In this set of experiments we reproducibly found that OVX-p62 treated mice group (at variance of control groups) showed a restored trabecular microarchitecture at metaphyseal regions of the distal femurs and a decreased porosity in cortical bone (Figure 4A–4H). In addition, p62-DNA treatment proved to increase both bone mineral density (BMD) and content (BMC) as judged by DEXA analysis (Figure 5A–5B). Finally, coupled with marked up-regulation of osteoblastogenic Runx2 and Osterix (Figure 6A), a strong inhibition of two majors bone resorptive factors such as TNFα and RANKL was also observed in BMCs from OVX-p62 mice. It is worth noting that RANKL is a key mediator of inflammation that, by binding to its receptor RANK on osteoclast precursors, fosters osteoclastogenesis via intracellular NF-kB signaling [23]. In our experimental setting, a down-regulation of NF-kB in OVX-p62 BMCs was also observed (Figure 6B).

Figure 4. p62 DNA rescues osteoporosis.

Representative reconstructions of metaphyseal regions of distal femurs from OVX-pcDNA3.1 (A, C) and OVX-p62DNA mice (B, D). Arrows indicated the trabecular bone loss (C) and the restored trabecular microarchitecture (D) Representative sections of femur mid diaphysis from OVX-pcDNA3.1 (E, G) and OVX-p62 DNA mice (F, H). Note the expansion of the medullary cavity and the resorption cavities within the cortex (Arrow, G). Arrows indicated the reconstitute cortical bone structure (H) Magnifications: 10 × (C, D, G, H), 5 × (E, F).

Figure 5. BMD and BMC evaluation after p62 treatment.

Bone mineral density (A) and bone mineral content (B) were increased in OVX mice treated with p62-encoding plasmid. (*p < 0.05).

Figure 6. p62 vaccine decreases pro-inflammatory markers.

Total bone marrow cell population was obtained from long bones of OVX, OVX-pcDNA3.1 and OVX-p62 DNA. Note the statistically significant increase of Runx2 and osterix (A) as well as the decrease of RANKL, TNFα and NFkB (B) protein levels only after p62 treatment. (*p < 0.05).

A unexpected ring: exo-p62 up-regulates endo-p62 expression

As anticipated, although there are reports in the literature suggesting that in vitro overexpression of p62 may dull the production of inflammatory cytokines [11], there are no in vivo data about a putative role of exogenous p62 DNA in inflammation. While not wishing to be held by theory, we evaluated the expression levels of p62 in BMCs retrieved from plasmids injected in mice before ovariectomy. With much of our surprise, we found that while p62 expression in BMCs was down-regulated by ovariectomy, BMCs from p62 DNA pre-injected mice demonstrated a sturdy and selective up-regulation of p62 (Figure 7A). Consistently, an increased p62-immune labeling was observed at the epiphyseal region of femurs of p62-OVX mice (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. p62 encoding plasmid up-regulates the endogenous p62 protein synthesis.

p62 protein levels were detected in total bone marrow population (A) and in the epiphyseal areas of femur sections (B) by Western blotting and immunofluorescence, respectively. Note the increase of p62 synthesis in samples from p62-OVX mice. Evaluation of p62 levels in BMCs by a specific mouse/human antibody or by a specific human antibody. Note the lack of human p62 detection, and the increase of mouse p62 protein in BMCs from p62-OVX mice (C) (*p < 0.05).

Next we asked whether this enhanced p62 immune-reactivity refers to exogenous human p62DNA or to endogenous mouse p62. In order to distinguish between these two possibilities we utilized two types of anti-p62 antibodies for western blotting analysis of BMCs extracts: a polyclonal rabbit Ab that recognized both human and mouse p62, and a monoclonal Ab that recognize only human p62 [24]. A human p62 recombinant protein was loaded as positive control. As depicted in (Figure 7C), we found that p62DNA administration clearly up-regulates endogenous p62 protein in bone marrow resident cells.

A growing understanding of the bone remodeling processes suggest that factor involved in inflammation are linked with those critical for bone physiology and remodeling, supporting the theory that inflammation significantly contributes to the aetiopathogenesis of osteoporosis. Indeed, our results provide for the first time evidences that in this model (OVX) of inflammation-mediated osteopenia, p62DNA, by exerting powerful anti-inflammatory effects, counteracts bone loss, and as consequence, promotes new bone formation [25]. Importantly, the dramatic effects of p62 DNA on bone homeostasis were not associated with any side effects as demonstrated by previous long-term toxicological studies [26]. In this context it has to be underlined that the major pharmacological interventions for osteoporosis, so far proposed, evidenced a long list of worrisome side effects [27, 28].

Taken together, our data can be viewed as proof of concept for pre-clinical and clinical development of an unprecedented strategy based on p62-DNA to counteract osteoporosis [29]. More broadly, we hypothesize that the administration of p62 DNA may quench chronic inflammatory reactions underpinning a variety of age-related diseases.

MATERIALS & METHODS

DNA Plasmids

Human p62 (SQSTM, isoform 1) was cloned in pcDNA3.1 (InVitrogene) vector as previously described [6]. Large scale preparations of the endotoxin-free plasmids were routinely performed by alkaline lysis using either Endo Free Plasmid Kit (Qiagen) or Gen Elute HPSelect Plasmid Giga Prep columns (SIGMA # NA0800). For intramuscular injections (femoral quadriceps), mice were anesthetized and injected with 100 μg DNA (1 mg/ml) in saline solutions. All groups were subjected to three injections at one week intervals.

Animals and treatments

Thee-month old female FVB and Balb/c mice (Harlan Italy SrL, Correzzana Milano, Italy) were used. Mice were kept in laminar-flow cage in a standardized environmental condition. In prevention trials mice were randomly distributed in three groups (G1–G3) and injected intramuscularly at week 0, 1, 2 with only saline (G1, n = 12), with pcDNA3.1 (G2, n = 12), or with hp62 DNA (G3 n = 12). At day forty-five after the last injection, mice from each group were randomly divided in two subgroups and were sham operated (SO; n = 6) or ovariectomized (OVX n = 6). After two months mice were sacrificed by CO2 narcosis according to the recommendation of the Italian Ethical Committee. For therapeutic trials mice were ovariectomized (OVX) and left untreated for 2 months. Afterwards, mice were randomized in 3 groups, and injected with plasmids as described above. After 2 months mice were sacrificed for analysis.

Histological bone analysis and immuflourescence

Femurs, dissected of adhering tissue, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24 h, decalcified in 14% EDTA solution for 3 days and soaked in 30% sucrose overnight. Samples, embedded with Tissue-Tek OCT compound, were sectioned (8 μm thick sections) by a rotatory −30°C microtome cryostat (Ames Cryostat Miles) and stained with toluidine blue.

Other sections, after permeabilization with 0.3% Triton X-100 were incubated with rabbit anti-p62 diluted 1: 800 (Enzo Life Sciences; Vinci-Biochem s.r.l., Firenze, Italy) diluted 1:400. After rinsing, sections were incubated with chicken anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated (Molecular Probes; Invitrogen, Milano Italy) diluted 1:100. Control experiments were performed by omitting the appropriate primary antibody or by neutralizing the primary antibodies with the relative blocking peptide. Slides were imaged using a Leica DM 2500 fluorescent microscopy. Fluorescence analysis was performed by a fluorimeter Tecan Infinite [30].

Ex vivo dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) analyses

Femurs were dissected and fixed as above described. Bone mineral density (BMD) and bone mineral content (BMC) were measured using a PIXImus DEXA [31].

Bone marrow cell (BMCs) preparation

Long bones (femurs, tibiae and humeri) from the above mouse groups were dissected free of adhering tissue. The ends were removed and the marrow cavity was flushed and cultured in DMEM as previously described [32].

Cytokines and chemokines assay

The cytokine/chemokine profiles of BMCs supernatants were assessed by ELISA-based cytokine array by using Mouse Cytokine Array Panel A kit (R&D Systems, Milano, Italy) accordingly to the manufacturer's instructions. Immunoreactive dots were visualized using LiteAblot Turbo luminol reagents (Euroclone, Milano, Italy) and Hyperfilm-ECL film (Euroclone, Milano, Italy) and quantitated densitometrically.

Western blotting

Proteins from total bone marrow cells population were extracted in Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Euroclone, Milano, Italy) immediately after flushing the bone marrow cavity, and the concentration was determined by the BCA protein assay reagent (Pierce, Euroclone Milano, Italy). Western blotting was performed as previously described [33]. Human recombinant p62 was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences; Vinci-Biochem s.r.l., Firenze, Italy. Membranes were immunoblotted in blocking buffer with specific antibodies: rabbit anti-mouse p62 (1: 800 dilution, Enzo Life Sciences; Vinci-Biochem s.r.l., Firenze, Italy); mouse anti-human p62 (1:800 dilution, BD Transduction Laboratories, Milano, Italy); mouse anti-Receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) antibody (1:250 dilution, Abcam, Prodotti Gianni, Milano, Italy); rabbit anti-Runx-2 antibody (1:800 dilution, Cell Signaling, Euroclone, Milano, Italy); rabbit anti-Osterix antibody (1:600 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Italy); rabbit anti-NF-kB (1:500 dilution, BioLegend, Microtech Srl, Napoli, Italy). After washing blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG or with HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling, Euroclone Milano, Italy). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using luminol reagents/ECL film as described above. To normalize the bands, filters were stripped and re probed with a monoclonal anti-α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, Milano, Italy). Bands density was quantified densitometrically.

Statistical analysis

All in vitro and in vivo experiments were repeated at least three times. t-student was used to test for significant differences between two groups, and differences were considered significant at (*p < 0.05).

SUPPLEMENTARY FIGURE

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by Pharma 2020 Technology Transfer grant to A.S., by Strategic University FAR Project (Unicam) Grant to FM.V, and by FAR (Unicam) to M.G.S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. p62: a versatile multitasker takes on cancer. Trends Biochem. Scie. 2012;37:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geetha T, Vishwaprakash N, Sycheva M, Babu JR. Sequestosome 1/p62: across diseases. Biomarkers. 2012;17:99–103. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2011.653986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park S, Ha S-D, Coleman M, Meshkibaf S, Kim SO. p62/SQSTM1 Enhances NOD2-mediated signaling and cytokine production through stabilizing NOD2 oligomerization. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:1–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salminen A, Kaarniranta K, Kauppinen A. Inflammaging: disturbed interplay between autophagy and inflammasomes. Aging. 2012;4:166–175. doi: 10.18632/aging.100444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu HB, Kielczewska A, Rozek A, Takenaka S, Li Y, Thorson L, Hancock RE, Guarna MM, North JR, Foster LJ, Donini O, Finlay BB. Sequestosome-1/p62 is the key intracellular target of innate defense regulator peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:36007–36011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.073627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venanzi F, Shifrin V, Sherman M, Gabai V, Kiselev O, Komissarov A, Grudinin M, Shartukova M, Romanovskaya-Romanko EA, Kudryavets Y, Bezdenezhnykh N, Lykhova O, Semesyuk N, Concetti A, Tsyb A, Filimonova M, Makarchuk V, Yakubovsky R, Chursov A, Shcherbinina V, Shneider A. Broad-spectrum anti-tumor and anti-metastatic DNA vaccine based on p62-encoding vector. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1829–1835. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabai V, Venanzi FM, Bagashova E, Rud O, Mariotti F, Vullo C, Catone G, Sherman MY, Concetti A, Chursov A, Latanova A, Shcherbinina V, Shifrin V, Shneider A. Pilot study of p62 DNA vaccine in dogs with mammary tumors. Oncotarget. 2014;25 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2516. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yip KHM, Feng H, Pavlos NJ, Zheng MH, Xu J. p62 Ubiquitin binding-associated domain mediated the receptor activator of nuclear factor-B ligand-induced osteoclast formation a new insight into the pathogenesis of Paget's disease of bone. Amer. J. Pathology. 2006;169:503–514. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rea SL, Walsh JP, Ward L, Yip K, Ward BK, Kent GN, Steer JH, Xu J, Ratajczak T. A novel mutation (K378X) in the sequestosome 1 gene associated with increased NF-B signaling and Paget's disease of bone with severe phenotype. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2006;21:1136–1145. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Najat DE, Thomas T, Hagen T, Shaw B, Sheppard PW, Falchetti A, Marini F, Brandi ML, Long JE, Cavey JR, Searle MS, Layfield R. Characterization of a non-UBA domain missense mutation of sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) in Paget's disease of bone. J. Bone Min. Res. 2009;24:632–642. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.081204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim JY, Ozato K. The Sequestosome 1/p62 Attenuates Cytokine Gene Expression in Activated Macrophagesby Inhibiting IFN Regulatory Factor 8 and TNF Receptor-Associated Factor 6/NF-kB. J. Immunol. 2009;182:2131–2140. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valencia T, Kim JY, Abu-Baker S, Moscat-Pardos J, Ahn CS, Reina-Campos M, Duran A, Castilla EA, Metallo CM, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. Metabolic reprogramming of stromal fibroblasts through p62-mTORC1 signaling promotes inflammation and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2014;26:121–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franceschi C, Bonafe M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, De Benedictis G. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann. NY. Acad. Sci. 2000;908:244–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riggs BL, Khosla S, Melton LJ. Sex steroids and the construction and conservation of the adult skeleton. Endocr. Rev. 2002;23:279–302. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.3.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakashima T, Takayanagi H. Osteoimmunology: crosstalk between the immune and bone systems. J. Clin. Immunol. 2009;29:555–67. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9316-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pacifici R. Role of T Cells in Ovariectomy Induced Bone Loss-Revisited. J. Bone Min. Res. 2012;27:231–239. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duran A, Serrano M, Leitges M, Flores JM, Picard S, Brown JP, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. The atypical PKC-interacting protein p62 is an important mediator of RANK activated osteoclastogenesis. Dev. Cell. 2004;6:303–309. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abu-Taha M1, Rius C, Hermenegildo C, Noguera I, Cerda-Nicolas JM, Issekutz AC, Jose PJ, Cortijo J, Morcillo EJ, Sanz MJ. Menopause and ovariectomy cause a low grade of systemic inflammation that may be prevented by chronic treatment with low doses of estrogen or losartan. J Immunol. 2009;183:1393–402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baeza I, De Castro NM, Giménez-Llort L, De la Fuente M. Ovariectomy, a model of menopause in rodents, causes a premature aging of the nervous and immune systems. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010;219:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jee WSS, Yao W. Overview: animal models of osteopenia and osteoporosis. Musculoskel. Neuron. Interact. 2001;1:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goswami J, Hernández-Santos N, Zuniga LA, Gaffen SL. A bone-protective role for IL-17 receptor signaling in ovariectomy-induced bone loss. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:2831–2839. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sabbieti MG, Agas D, Marchetti L, Coffin JD, Xiao L, Hurley MM. BMP-2 differentially modulates FGF-2 isoform effects in osteoblasts from newborn transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154:2723–33. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu M, Qi X, Moreno JL, Farber DL, Keegan AD. NF-κB signaling participates in both RANKL- and IL-4–induced macrophage fusion: receptor cross talk leads to alterations in NF-κB pathways. J. Immunol. 2011;187:1797–806. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seibenhener ML, Zhao T, Du Y, Calderilla-Barbosa L, Yan J, Jiang J, Wooten MW. Behavioral effects of SQSTM1/p62 overexpression in mice: support for a mitochondrial role in depression and anxiety. Behav Brain Res. 2013;248:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishikawa K, Nakashima T, Takeda S, Isogai M, Hamada M, Kimura A, Kodama T, Yamaguchi A, Owen MJ, Takahashi S, Takayanagi H. Maf promotes osteoblast differentiation in mice by mediating the age-related switch in mesenchymal cell differentiation. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:3455–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI42528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gabai VL, Shifrin VI. Feasibility analysis of p62 (SQSTM1)-encoding DNA vaccine as a novel cancer immunotherapy. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2014;33:375–82. doi: 10.3109/08830185.2014.954699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martino S, Cauley JA, Barrett-Connor E, Powles TJ, Mershon J, Disch D, Secrest RJ, Cummings SR CORE Investigators. Continuing outcomes relevant to Evista: breast cancer incidence in postmenopausal osteoporotic women in a randomized trial of raloxifene. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1751–61. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrett-Connor E, Mosca L, Collins P, Geiger MJ, Grady D, Kornitzer M, McNabb MA, Wenger NK. Effects of raloxifene on cardiovascular events and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:125–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lippuner K. The future of osteoporosis treatment - a research update. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13624. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabbieti MG, Agas D, Marchetti L, Santoni G, Amantini C, Xiao L, Menghi G, Hurley MM. Signaling pathways implicated in PGF2α effects on Fgf 2+/+ and Fgf 2−/− osteoblasts. J. Cell. Physiol. 2010;224:465–474. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopez Franco GE, Tyriina TK, Litscher SJ, Urban-Piette M, Robert D, Blank RD. Accuracy and Precision of PIXImus Densitometry for Ex Vivo Mouse Long Bones. J. Clin. Dens. 2004;7:326–333. doi: 10.1385/jcd:7:3:326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montero A, Okada Y, Tomita M, Ito M, Tsurukami H, Nakamura T, Doetschman T, Coffin JD, Hurley MM. Disruption of the fibroblast growth factor-2 gene results in decreased bone mass and bone formation. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:1085–1093. doi: 10.1172/JCI8641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agas D, Sabbieti MG, Marchetti L, Xiao L, Hurley MM. FGF-2 enhances Runx-2/Smads nuclear localization in BMP-2 canonical signaling in osteoblasts. J. Cell. Physiol. 2013;228:2149–2158. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.