Abstract

The Wnt/β-catenin pathway has been known to play a role in induction of immune tolerance, but its role in the induction and maintenance of NKT cell anergy is unknown. We found that activation of the Wnt pathway(s) in the liver microenvironment is important for induction of NKT cell anergy. We identified a number of stimuli triggering Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation, including exogenous NKT cell activator, glycolipid α-GalCer, and endogenous PGE2. Glycolipid α-GalCer treatment of mice induced the expression of wnt3a and wnt5a in the liver, and subsequently resulted in a liver microenvironment that induced NKT cell anergy to α-GalCer restimulation. We also found that circulating PGE2 carried by nanoparticles is stable, and that these nanoparticles are A33+. A33+ is a marker of intestinal epithelial cells, which suggests that the nanoparticles are derived from the intestine. Mice treated with PGE2 associated with intestinal mucus-derived exosome-like nanoparticles (IDEN) induced NKT cell anergy. PGE2 treatment leads to activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by inactivation of GSK-3β of NKT cells. IDEN-associated PGE2 also induces NKT cell anergy through modification of the ability of DCs to induce IL-12 and IFN-β in the context of both glycolipid presentation and TLR-mediated pathways. These findings demonstrate that IDEN associated PGE2 serves as an endogenous immune modulator between the liver and intestines and maintains liver NKT cell homeostasis and this finding has implications for development of NKT cell–based immunotherapies.

Keywords: Intestinal mucus-derived nanoparticles, Exosomes, Wnt and PGE2 signaling, liver NKT anergy

Introduction

Unlike T cells, NKT cells respond to lipid-based antigens including self and foreign glycolipid and phospholipid antigens (1) presented by CD1d restricted APCs. Among these lipid-based antigens, alpha-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer) is a synthetic glycosphingolipid derived from the marine sponge, Agelas mauritianus, and is commonly used in mice and human NKT studies as a potent activator of NKT cells in vivo or in vitro (2). A single injection of the exogenous α-GalCer leads to NKT cell activation followed, by long-term anergy, thereby limiting its therapeutic use(3). A number of potential endogenous glycolipids derived from dietary metabolic products and lipids derived from some intestinal bacteria migrate constantly into the liver(4–6) and these lipids can activate liver NKT cells in vitro(7). It is, therefore, remarkable that liver NKT cells are normally quiescent even though they are constantly exposed to intestinal-derived products. The molecular mechanisms that underlie induction of liver NKT cell anergy regulated by either exogenous α-GalCer or endogenous lipids are largely unknown.

The gut communicates extensively with the liver(8) through a number of gut derived molecules that are constantly migrating into the liver. PGE2 and Wnt ligands are enriched in the gut, and whether they migrate into the liver and subsequently contribute to induction of liver NKT anergy has not been fully investigated. Both PGE2 (9) and Wnt (10) regulated pathways are known to play a crucial role in immune tolerance; however, a direct link between these two key pathways remains to be identified although recent studies have proposed involvement of the Wnt pathway in regulating T cells (11, 12) and DC(10) activation.

In this study, we demonstrate that preconditioning of the Wnt pathway for activation in the liver microenvironment is essential for induction of NKT cell anergy regardless of whether the NKT cells are naïve or educated. We further identified a previously undescribed mechanism in which the carriage of PGE2 by intestinal mucus-derived exosome-like nanoparticles (IDEN) into the liver created an environment in which activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is induced.

Material and Methods

Adoptive transfer

NKT cells were enriched by negative magnetic sorting (Miltenyi Biotec) using anti-CD11b, B220, CD8α, Gr-1, CD62L and CD11c antibodies. Enriched NKT cells (5 × 106 per mouse) were then injected i.v. into irradiated NOD-SCID mice. In some case, NK1.1+CD5+ surface stained cells (NKT) were sorted using a FACSVantage. Sorted NKT cells were 85–90% pure as determined by tetramer staining. To determine the effects of the liver microenvironment created by Wnt signaling on liver NKT cells, Tcf/LEF1-reporter mice as recipients were treated with α-GalCer (3μg, Avanti polar Lipids, Inc., Birmingham, AL) or lithium chloride (Sigma, 200 mg/kg) every three days for 12 days. Recipients were then irradiated (750 rads) before i.v. administering enriched NKT cells (10 × 106 per mouse) from C57BL/6 CD45.1+ mice. 24 h after cell transfer the mice were injected i.v. with α-GalCer (5μg/mouse).

Details of other methods used in this study are described in the supplemental experimental procedures.

Results

Wnt activation creates a microenvironment that causes NKT cell anergy to α-GalCer stimulation in vitro and in vivo

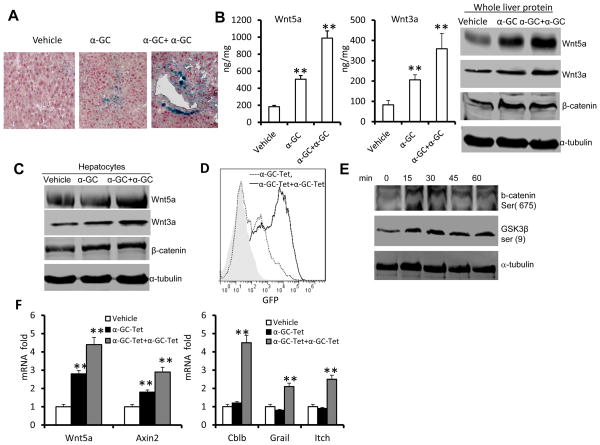

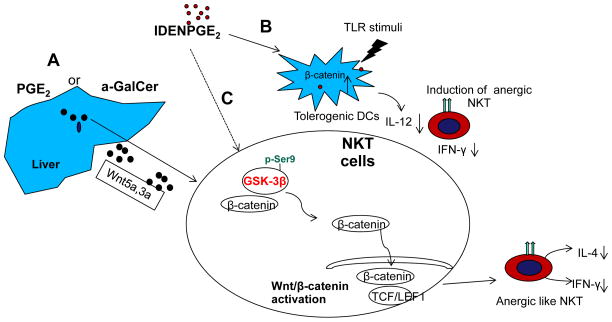

We first tested whether activation of Wnt/β-catenin modulates the activity of liver NKT cells. Sorted liver NKT cells that were transfected with constitutively activated β-catenin (Ctnnb1) exhibited a reduction in α-GalCer tetramer-stimulated NKT-cell proliferation (Fig. 1A) and production of IFN-γ and IL-4 (Fig. 1B). Because of this result we tested whether the wnt/β-catenin pathway was activated when mice are treated with α-GalCer. We found that a single injection of α-GalCer caused an increase in β-catenin/Tcf/LEF1 signaling throughout the liver of mice, as indicated by β-galactosidase activity. Multiple injections of α-GalCer resulted in much stronger β-catenin/Tcf/LEF1 signaling than a single injection (Fig. 2A). The α-GalCer treatment modulated the levels of expression of genes encoding multiple components of the Wnt pathway, including LEF1, Tcf7, Wnt5a, Wnt3a, Wnt7a, Wnt7b and Wnt10a, as determined by qRT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. 1). The results from both ELISA ((Fig. 2B, left panel) and western blot analysis (Fig. 2B, right panel) indicate that a significant increase in the levels of Wnt5a and Wnt3a proteins and β–catenin protein was observed during liver recovery following α-GalCer restimulation. Since the α-GalCer stimulation or α-GalCer/α-GalCer restimulation did not affect β-catenin transcription (Supplementary Fig. 1), the α-GalCer stimulation most likely influences the levels of β-catenin through non-transcriptional mechanisms. To determine whether activation of Wnt signaling occurs after α-GalCer stimulation in vivo, hepatocytes were isolated and cultured with liver leukocytes. Repeated addition of α-GalCer resulted in higher expression of Wnt5a and Wnt3a (Fig. 2C). In addition, treatment of a stably transfected, Tcf-driven-GFP NKT hybridoma with an α-GalCer tetramer led to an increase in the numbers of GFP+ cells, with restimulation leading to a further increase in the numbers of GFP+ cells (Fig. 2D). Consistent with the FACS analysis data, treatment of the NKT hybridoma with α-GalCer tetramer resulted in enhancement of phosphorylation of β-catenin and GSK3β (Fig. 2E) as well as induction of expression of the genes encoding Wnt5a and Axin2 (Fig. 2F). Unlike the induction of expression of the genes encoding Wnt5a and Axin2, restimulation was required for induction of the genes encoding Cbl-b, Grail and Itch (Fig. 2F), which are known to be associated with the development of the anergic state after stable expression of β-catenin in T cells(13–15). Furthermore, knockdown of LEF1 in the NKT hybridoma led to a partial reversing of the α-GalCer restimulation did not elicit IL-2 production (supplemental Fig. 2), suggesting that LEF1 is a critical transcriptional factor that regulates α-GalCer mediated anergy of NKT cells.

Figure 1. Stable expression of β-catenin gene induces anergy in liver NKT cells.

Sorted β-catenin-GFP+ or control vector-GFP+ retroviral transduced NKT cells were co-cultured with BMDCs in the presence of α-GalCer. (A) Cell proliferation measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation assay; (B) Levels of IFN-γ and IL-4 in the supernatant 24 h after α-GalCer treatment of cultures. **p <0.01 (Student’s t-test). Data are the mean SEM of three experiments.

Figure 2. α-GalCer simulation leads to the activation of Wnt signaling in the liver.

(A–C) TCF/LEF1-reporter mice were given a single-dose of α-GalCer (5μg, α-GC), multiple doses α-GalCer (5μg, every 3 d for 3 times, α-GC+ α-GC), or vehicle by intravenous injection and assessed 24 h after the last injection (n=7). (A) X-gal staining of sections of paraffin-embedded liver tissue. Magnification = ×20. (B) Expression of Wnt 3a and Wnt 5a in whole liver extracts from treated mice as assessed using an ELISA (left two panels) and immunoblot analysis (right panel). (C) Immunoblot analysis of proteins of primary hepatocytes co-cultured with liver leucocytes in the presence of α-GalCer for 24 h. (D) FACS analysis of GFP expression on Tcf-GFP-NKT hybridoma 1.2 after stimulation with a single dose of α-GalCer-tetramer (α-GC-Tet) or after restimulation with α-GalCer-tetramer (-α-GC-Tet+α-GC-Tet). (E) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated β-catenin ser (675) and GSK3β ser (9) in NKT cell hybridoma 1.2 stimulated with α-GalCer tetramer. (F) Changes in mRNA abundance in NKT cell hybridoma 1.2 treated with α-GalCer tetramer for 24 h, washed with PBS, and then restimulated with α-GalCer tetramer (α-GC-Tet+α-GC-Tet), or untreated NKT cell hybridoma 1.2 stimulated by α-GalCer (α-GC-Tet) or vehicle (vehicle) for 5h. Data are the mean ± SEM of three experiments (B,F) or representative of three experiments (A, B, right panel, C, D, E).

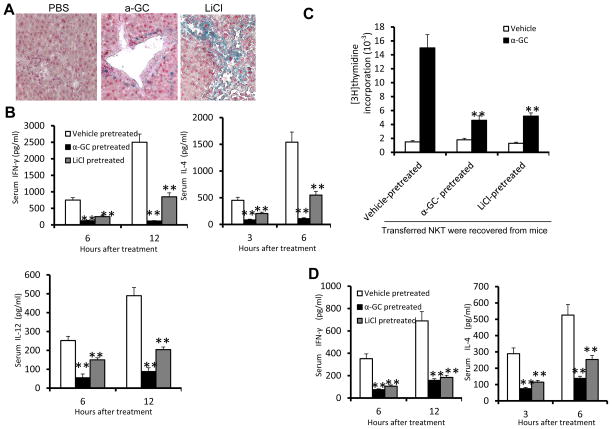

To directly assess whether the liver microenvironment created by α-GalCer stimulation has functional significance in the induction of NKT cell anergy, we used an adoptive transfer approach in which NKT cells from naïve mice were transferred into γ irradiated Tcf/LEF1-reporter mice that had been preinjected with α-GalCer, LiCl, or vehicle (PBS) as a control. The reconstituted mice were then injected with α-GalCer. Staining of liver sections from the Tcf/LEF1-reporter mice for β-galactosidase showed that Wnt signaling in the liver is indeed activated by α-GalCer or LiCl treatment (Fig. 3A). The production of IFN-γ and IL-4 was significantly lower in the recipient mice that had been pretreated with α-GalCer or LiCl than in PBS-treated animals (Fig. 3B). The α-GalCer or LiCl treatments had a similar effect on the production of IL-12 (Fig. 3B), suggesting that anergy of IL-12-producing cells, including dendritic cells, is induced. To confirm whether the anergy of adoptive transferred NKT cells from naïve mice is induced, NKT cells were recovered from the liver of α-GalCer or LiCl treated recipient mice and cocultured with liver DCs from naïve mice. NKT cells re-isolated from the livers of recipient mice pretreated with α-GalCer or LiCl were not responsive to treatment with α-GalCer ex vivo (Fig. 3C); whereas, the NKT cells reisolated from the livers of recipient mice pretreated with vehicle control were responsive. To confirm these findings, we also adoptively transferred NKT cells recovered from vehicle, α-GalCer, or LiCi-injected mice to Rag1KO mice. The production of IFN-γ and IL-4 was significantly lower in the Rag1KO mice that received NKT cells from α-GalCer or LiCl-treated mice when compared to Rag1KO mice that received NKT cells from PBS-treated mice (Fig. 3D). Collectively, these results indicate that the liver microenvironment plays a key role in the induction of anergy in NKT cells because irrespective of whether the NKT cells had been pretreated with α-GalCer or not, they lost their responsiveness to α-GalCer as long as a Wnt-enriched liver environment was established.

Figure 3. Activation of Wnt signaling in the liver led to NKT cell anergy.

Recipient TCF/LEF1-reporter mice were treated with α-GalCer (3μg, i.v.), LiCl (200 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle as a control every three days for 12 days then irradiated (750 rads). After 5d, they were injected i.v. with enriched liver NKT cells (10 × 106 per mouse) from naïve C57BL/6 CD45.1+ mice. (A) X-gal staining of sections of paraffin-embedded liver tissue obtained 24 h after the last injection of LiCl. (B) Serum cytokine levels in the reconstituted mice at different time points after α-GalCer injection. (C) Proliferation of NKT cell recovered from recipient mice 3 days after cell transfer as described above and co-cultured with liver DCs from naïve mice in the presence of α-GalCer. (D) The recovered NKT cells were transferred into Rag1 KO mice for 9h, and the mice were then administered α-GalCer (intravenously); the serum cytokine levels assessed were examined at the indicated time points after the α-GalCer injection. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test (B), one-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test (A, C, D). Data are the mean ± SEM of at least 3 experiments (n=5) (A, C,D), or are representative of at least three independent experiments (D).

PGE2 plays a role in the induction of liver NKT cell anergy by activation of Wnt/β-catenin

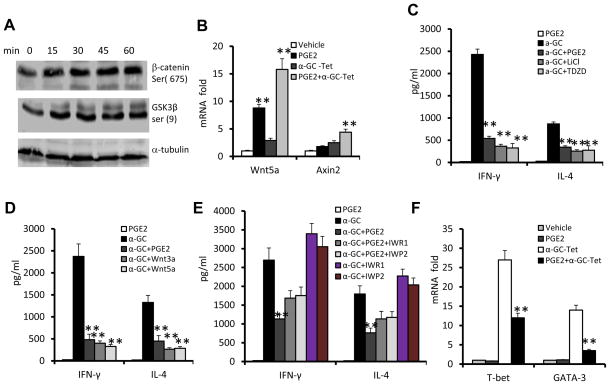

PGE2 is known to modulate Wnt/β-catenin activity in cancer cells. However, the role of PGE2 in terms of regulating NKT cell activation is not known. Treatment of wild-type NKT cells with PGE2 led to increased phosphorylation of β-catenin, as well as prompting phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) in a time dependent manner (Fig. 4A) and induction of the expression of the genes encoding the Wnt ligands, Wnt5a and Axin2 (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, treatment with PGE2 together with α-GalCer had a synergistic effect on the induction of expression of the gene encoding Wnt 5a (Fig. 4B),

Figure 4. PGE2 cross-talk with Wnt signaling leads to NKT cell anergy.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated β-catenin ser (675) and GSK3β ser (9) in sorted liver NKT cells stimulated with PGE2. (B) Changes in mRNA abundance in NKT cell hybridoma 1.2 stimulated with α-GalCer-tetramer (α-GC-Tet) and/or PGE2 for 5 h. (C–E) Levels of IFN-γ and IL-4 in the supernatants of liver NKT cells co-cultured with BMDCs that had been pretreated with PGE2 or the following inhibitors/ligands for 3h and then stimulated with α-GalCer or vehicle (DMSO) for 24 h. (C) TDZD (10 μM), LiCl (10 mM); (D) Wnt3a (0.5 μg/ml), wnt5a (0.5 μg/ml); and/or (E) IWR1 (5 μM), IWP2 (5 μM). (F) Changes in mRNA abundance in NKT cell hybridoma 1.2 stimulated with α-GalCer-tetramer (α-GC-Tet) and/or PGE2 for 5 h. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (one-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test). Data (B–F) are the mean ± SEM of at least 4 experiments (n=5) or representative of three independent experiments (A).

To further determine whether PGE2 mediated inactivation of GSK-3β plays an essential role in induction of NKT cell anergy, NKT cells were treated with two GSK-3β specific inhibitors. Liver NKT cells were stimulated with the α-GalCer in thiadiazolidinone (TDZD), a non-ATP competitive inhibitor of GSK-3β that binds to the active site of GSK-3β. The addition of the non-ATP competitive GSK3β inhibitor suppressed the production of IFN-γ and IL-4 in the α-GalCer-stimulated NKT cells (Fig. 4C). Similar results were obtained upon treatment of NKT cells with another non-ATP competitive GSK3β inhibitor, lithium chloride (LiCI) (Fig. 4C). Treatment of the α-GalCer-stimulated NKT cells with Wnt3a or Wnt5a ligands resulted in effects similar with those obtained for treatment of NKT cells with GSK3β inhibitors (Fig. 4D). Reduced IFN-γ production was not due to an intrinsic defect as there was no difference in the intracellular stained IFN-γ in the PMA and ionomycin stimulated NKT cells that had been treated with PGE2 or PGE2 vehicle (supplemental Fig. 3) Furthermore, blocking of the canonical Wnt activation pathways using IWR1 or IWP2 led to a partial reversal of PGE2-mediated inhibition of production of IFN-γ and IL-4 (Fig. 4E). The results from real-time PCR analysis also indicate that the PGE2 mediated reduction in IFN-γ and IL-4 correlated with the inhibition of expression of T-bet and GATA-3 (Fig. 4F), key transcription factors regulating IFN-γ and IL-4 expression and maturation of NKT cells(16, 17). Furthermore, knockdown of LEF1 in the NKT hybridoma led to partial reversing of PGE2 mediated inhibition of IL-2 production (supplemental Fig. 4), suggesting that LEF1 is a critical transcriptional factor that regulates PGE2 mediated anergy of NKT cells. Collectively, PGE2 stimulation led to activation of Wnt/β-catenin and subsequently the induction of NKT cell anergy.

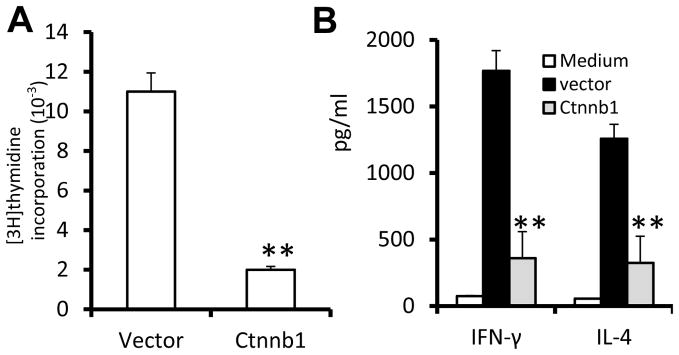

Intestinal mucus-derived exosome-like nanoparticle (IDEN)-associated PGE2 plays a role in induction of liver NKT cell anergy

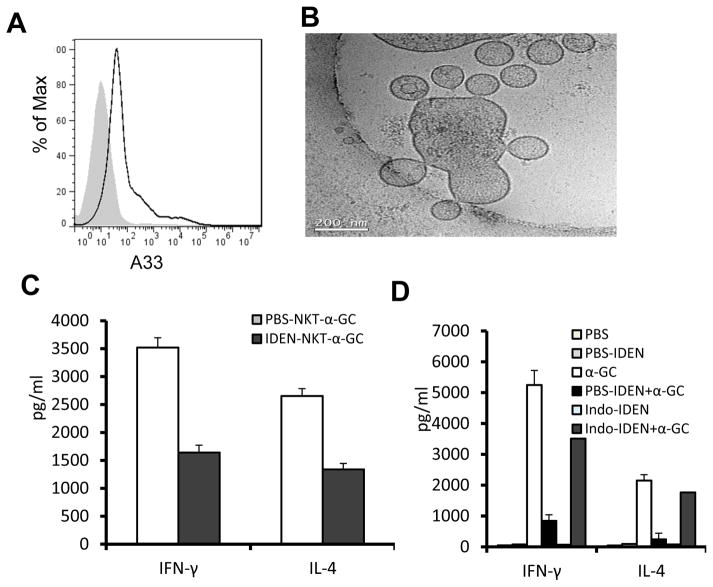

Exosome-like nanoparticles have a high capacity for binding PGE2 (18) and maintaining its stability and thus activity. ELISA analysis of circulating exosome-like nanoparticles indicates that the circulating nanoparticles carry PGE2 (Supplementary Fig. 5). FACS analysis of these circulating nanoparticles further indicates that they are also A33+ (Fig. 5A). A33+ is an intestinal epithelial marker, suggesting that these PGE2+ nanoparticles are derived from the intestine.

Figure 5. PGE2 associated with intestinal mucus derived exosome-like nanoparticles (IDEN) induces liver NKT cell anergy.

(A) FACS analysis was performed to determine expression of A33 on the surface of exosomes derived from peripheral blood. (B) Characterization of nanosized nanoparticles isolated from intestinal mucus. Intestine from B6 mice was used for isolation of nanosized nanoparticles by differential centrifugation as described previously(44). Sucrose-purified nanosized nanoparticles were examined by electron microscopy (Bar = 200 nm). (C) Cytokine production by liver NKT cells co-cultured with BMDCs in the presence of α-GalCer (100ng/ml) for 24h. NKT cells isolated from mice were i.v. injected along with IDEN or PBS every 2 days for 14 days. (D) Cytokine production by liver NKT cells from naïve mice cultured with BMDCs in the presence of PBS-IDEN, Indo-IDEN or PBS for 3h, and then stimulated by α-GalCer (100ng/ml) for 24h. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test). Data are representative of three experiments (A, B) or are the mean ± SEM of five independent experiments (C, D).

Nanosized particles in the gut migrate into the liver (19, 20) where the majority of the NKT cells reside. We tested whether intestinal mucus derived exosome-like nanoparticles (IDEN) can induce liver NKT cell anergy. The results from electron microscopy examination showed that they are nanoparticles in size (Fig. 5B). The nanoparticles were enriched for PGE2 (Supplemental Fig. 5). We then tested whether IDEN associated PGE2 plays a role in the induction of NKT cell anergy. NKT cells were purified from the livers of mice that had been administered IDEN or vehicle intravenously. NKT cells were cocultured in vitro with dendritic cells from the livers of untreated mice in the presence of α-GalCer. The results show that the NKT cells purified from the mice that had been administered IDEN had significantly lower production of both IFN-γ and IL-4 of NKT cells to α-GalCer stimulation (Fig. 5C). Liver NKT cells pretreated with circulating exosomes also produce less IFN-γ and IL-4 in response to α-GalCer stimulation (Supplemental Fig. 6), suggesting that EDEN PGE2 mediated induction of NKT cell anegy is physiological relevant.

To further determine whether the IDEN-associated PGE2 played a role in the induction of NKT cell anergy, mice were treated with indomethacin, a cyclo-oxygenase 2 inhibitor that blocks the generation of PGE2. The effects of IDEN isolated from indomethacin treated mice, on the induction of NKT cell anergy were then evaluated. Indomethacin treatment reduced significantly the amounts of PGE2 associated with the IDEN (Supplementary Fig. 5), which ultimately led to the attenuation of the IDEN-mediated anergy induction in NKT cells to α-GalCer stimulation (Fig. 5D).

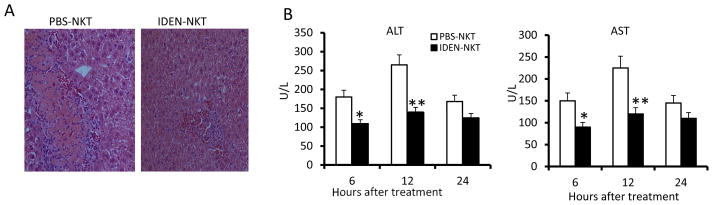

To further demonstrate the role of IDEN mediated anergy induction of liver NKT cells in vivo, we used a ConA-induced hepatitis mouse model. ConA-induced hepatitis is dependent on NKT cell activity (21). Using an adoptive transfer approach, we found, as expected, that SCID mice that received liver NKT cells from PBS-treated mice exhibited the typical liver necrosis (Fig. 6A) and elevation of serum ALT and AST (Fig. 6B). In marked contrast, the histologic evidence of necrosis in the liver (Fig. 6A) and the ConA-induced elevation of the levels of serum ALT and AST (Fig. 6B) were reduced significantly in the SCID mice that received liver NKT cells from IDEN-treated mice, indicating that the IDEN has a direct effect on induction of anergy in liver NKT cells.

Figure 6. Intestinal mucus derived exosome-like nanoparticles (IDEN)-protect mice against ConA induced hepatitis.

Effects of adoptive transfer of NKT cells isolated from mice treated with IDEN (100μg/mouse) or vehicle control (PBS) given i.v. every 3 d for 15 d into irradiated NOD-SCID mice on ConA-induced liver damage (25 mg ConA/kg, by intravenous injection 2 d after the last injection of IDEN) (n = 10). (A) H&E-staining of liver sections. (B) Levels of serum ALT and AST.

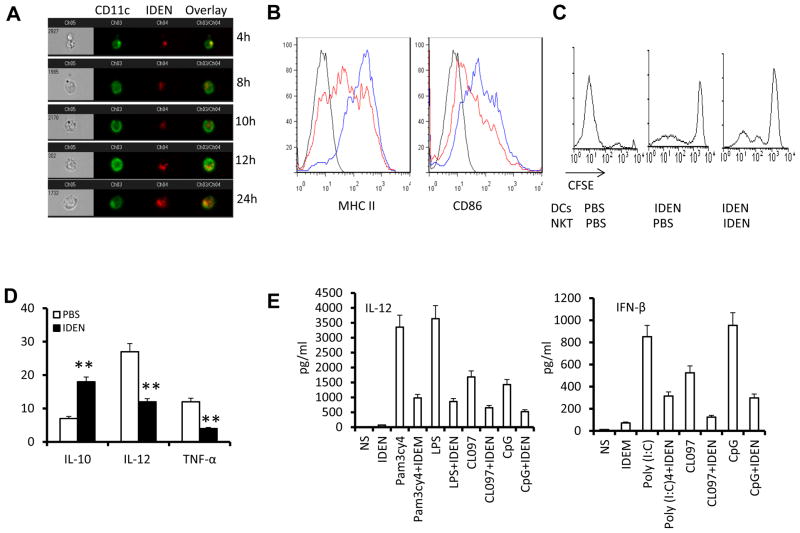

Intestinal mucus-derived exosome-like nanoparticles (IDEN) also induce NKT cell anergy in the context of both glycolipid presentation and TLR-mediated pathways

Antigen presenting cells play an essential role in liver NKT cell activation by presenting lipid related antigen on an APCs CD1d molecule dependent and independent manner(22). First, we tested whether DCs take up IDEN. Both CD11c+ DCs and F4/80+ macrophages from the livers of naïve mice took up IDEN rapidly (as early as 2 h) and continued to take up IDEN over 24 h (Fig. 7A, Supplementary Fig. 7). We then tested whether IDEN treatment has an effect on NKT cell activation of mice. FACS analysis of liver leukocytes suggested that the expression of MHCII and CD86 by the DCs (Fig. 7B) was reduced in mice that had been administered IDEN. On co-culture of DCs purified from the livers of mice that had been administered IDEN or vehicle with CFSE-labeled liver NKT cells isolated from mice that had been administered IDEN or vehicle in the presence of α-GalCer, DCs from the livers of mice that had been administered IDEN exhibited a reduced ability to stimulate the proliferation of NKT cells, regardless of the source of the NKT cells (Fig. 7C). RT-PCR analysis further indicated that the expression of IL-12 and TNFα, which are critical for activation of DCs and DC-mediated activation of NKT cells, was significantly lower in DCs sorted from the livers of α-GalCer-injected mice that had been administered IDEN (Fig. 7D). Additionally the levels of the immunosuppressive cytokine IL-10 were higher. DCs also can activate NKT cells in a CD1d-independent manner through Toll-like receptor (TLR)-induced release of soluble mediators, including IL-12 and type I interferons (IFNs)(23, 24). We found that IDEN suppressed the expression of IL-12 and IFN-β in TLR-stimulated DCs (Fig. 7E) and that IFN-γ release was reduced greatly when TLR ligand-treated DCs were co-cultured with liver NKT cells in the presence of IDEN (Fig. 7F). Thus, IDEN can also induce NKT cell anergy through modification of the ability of DCs to stimulate NKT cell anergy in the context of both glycolipid presentation and TLR-mediated pathways. To further determine whether IDEN-associated PGE2 plays a role in the inhibition of production of IL-12, the effects of IDEN isolated from indomethacin treated mice on the production of TLR stimulated DCs was evaluated. ELISA results (Fig. 7G) indicate that IDEN isolated from indomethacin treated mice have a reduced potency to inhibit IL-12 production, suggesting that IDEN associated PGE2 plays a role in inhibiting the production of IL-12 of TLR stimulated DCs.

Figure 7. Wnt signaling plays a role in Intestinal mucus-derived exosome-like microparticle (IDEN) induced NKT cell anergy in the context of both glycolipid presentation and TLR-mediated pathways.

(A) CD11c+ DCs take up IDEN. Hepatic MNCs (5 × 105) were cultured with PKH26-labeled IDEN (10 μg/ml) for 4-24 h at 37°C. IDEN positive cells are positive for: CD11c (green) and PKH26+ IDEN (red). At least 104 total events were collected for each sample. Data are representative of three independent experiments done in triplicate. (B–D) C57BL/6 mice were injected i.v. with PBS or IDEN (100 μg/mouse, every 2 d for 14 d. (B) Expression of MHC II and CD86 on CD11c+ DCs from the livers of mice pretreated with IDE (red) or PBS (blue) 24 h after being i.v. injected with α-GalCer (5μg/ml). (C) Liver NKT cells and DCs were sorted from mice pretreated with IDEN or PBS. The division of CFSE labeled liver NKT cells co-cultured with liver DCs for 3 d in the presence of α-GalCer was FACS analyzed. (D) Analysis of IL-10, IL-12 and TNF-α mRNA in DCs sorted from the livers of PBS or IDEN-treated mice 5 h after injection of α-GalCer. (E) Levels of IL-12 and IFN-β in supernatants of BMDCs cultured for 24 h in the presence of IDEN (50 μg/ml) with pam3cy4, LPS, poly(I:C), CL097 or CpG. (F) Presence of IFN-γ in supernatants of BMDCs cultured with sorted hepatic NKT cells in the presence of IDEN for 3 h, and then stimulated for 24 h with different TLR ligands indicated in the figure. (G) Levels of IL-12 in supernatants of BDMCs cultured for 24 h in the presence of IDEN (50 μg/ml) with LPS or CL097. IDEN were derived from mice treated with PBS or indomethacin. (H–J) IDEN mediated Wnt/β-catenin BMDC activation. (H) IDEN treatment leads to transactivation of TCF/LEF1 reporter. BMDCs from transgenic TCF/LEF1 reporter mice were treated by PBS or IDEN, and β-galactosidase activity was measured by flow cytometry with fluorescein di-β-D-galactosidase (FDG) as a substrate. Data are representative of three independent experiments. (I) Levels of IL-12 in supernatants of BCMCs cultured for 24 h in the presence of IWR1, IWP2 and/or IDEN (50 μg/ml) with LPS or CpG. (J) Presence of IFN-γ in supernatants of BMDCs co-cultured with sorted hepatic NKT cells in the presence of IWR1, IWP2 and/or IDEN for 3 h, and then stimulated by LPS or CpG for 24 h. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test). Data are representative of three esperiments (A, B, C, H) or are the mean SEM of three independent experiments (D, E, F, G, I, J).

We further tested whether IDEN mediated Wnt/β-catenin activation also plays a role in TLR stimulated DC activation. BMDCs derived from B6.Cg-Tg(BAT-lacZ)3Picc/J mice have a remarkable increase in β-galactosidase activity, where the β-galactosidase gene expression is driven by a Tcf/LEF1 promoter in the presence of IDEN (Fig. 7H).

Paradoxically, IDEN treatment also led to a reduction in IL-12 from BMDCs stimulated with TLR ligands as listed in figure 7I. The addition of canonical Wnt inhibitors, IWR1 and IWP2, led to the partial reversing of IDEN mediated inhibition of IL-12 production (Fig. 7J). Collectively, these results suggest that IDEN mediated activation of the Wnt pathway in DCs also plays a role in induction of NKT cell anergy.

Discussion

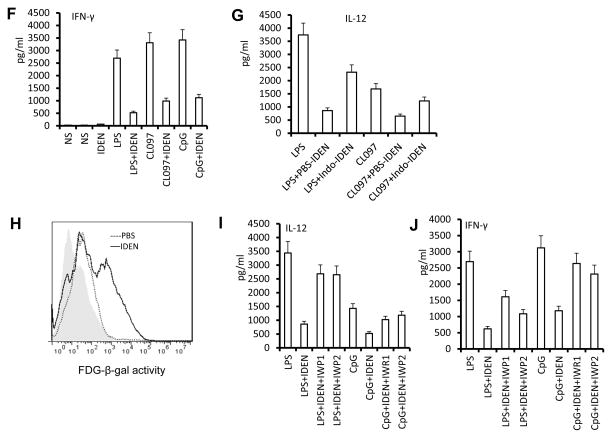

The results presented in this study suggest a model (Fig. 8) in which PGE2 or α-GalCer stimulation leads to induction and releasing Wnt ligands in the liver where NKT cells reside. NKT Wnt signaling activation mediated by PGE2, α-GalCer induced Wnt ligands, or PGE2 via inactivation of GSK-3β (a β-catenin inactivator), eventually activate β-catenin/LEF1 mediated transcriptional machinery which causes induction of NKT cell anergy. Alternatively, PGE2 mediated activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway in DCs leads to prevention of TLR stimuli induced production of IL-12 that is required for CD1d independent NKT cell activation. In this study, we provide for the first time evidence that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway leads to anergy of NKT cells. We also provide evidence for PGE2 cross-talk with the Wnt signaling pathway, which can occur through regulation of β-catenin/GSK3β activity. The evidence for PGE2 cross-talk with the Wnt signaling pathway is consistent with the literature in which a role for PGE2 in regulation of Wnt signaling at the level of β-catenin stability has been demonstrated in zebrafish hematopoietic stem cells(25).

Figure 8.

We propose three possible pathways that could lead to liver NKT cell anergy. (A). Repeated α-GalCer stimulation or PGE2 carried by IDEN leads to induction of Wnt ligands in the liver. Released Wnt 3a and Wnt 5a subsequently bind to liver NKT cells and activate β-catenin mediated TCF/LEF1 activation, which results in induction of NKT cell anergy. (B) Up take of IDEN-PGE2 by hepatic DCs results in activation of the β-catenin mediated pathway which then prevents the secretion of IL-12 induced by TLR stimuli. (c) IDEN-PGE2 could also directly bind to PGE2 receptors and subsequently activate the β-catenin mediated pathway by inactivation of GSK-3β.

It has also been reported that some factors through ubiquitin-mediated proteasome degradation may induce NKT cell anergy(26). The inhibition of α-GalCer-induced phosphorylation of ERK tyrosine kinase in NKT cells plays a role in induction of NKT cell anergy(27). Lacking co-stimulatory signals and cytokines provided by dendritic cells may also lead to NKT cell anergy(28–30). Whether these factors also cross-talk with PGE2/Wnt/β-catenin we identified in this study and lead to NKT cell anergy, will require further investigation to discern.

Recent studies suggest that exosome-like nanoparticles play a critical role in cell-cell communication(31, 32). Intestinal epithelial cells are known to release nanosized microvesicles(33, 34), and the nanoparticles have been shown to migrate into liver(19, 35). Our study further demonstrated that the gastrointestinal tract communicates directly with the liver via IDEN that carry PGE2. PGE2 carried by IDEN has at least two unique characteristics in comparison with the free form of PGE2. 1) The stability of PGE2 carried by IDEN is increased significantly as shown by the fact that the half-life of PGE2 is approximately 30 second in the circulator system (36, 37), and intravenous injection of chemically synthesized PGE2 did not have any effect on the induction of IFN-γ and IL-4 of mice treated with α-GalCer (Data not shown) and therefore could have no effect on activation of Wnt signaling in NKT cells. Besides the stability of PGE2 regulated by the local balance between the COX2-driven synthesis and 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH)-mediated degradation of PGE2 (38, 39), in this study, we demonstrated that amount of PGE2 carried by IDEN is also associated with the potency of induction of liver NKT cell anergy as the data presented in supplementary Figs. 5, 6. It is conceivable that the factors regulating the amount available and the affinity of IDEN binding to PGE2 may also contribute to PGE2 mediated Wnt signaling. The role of ceramide (40) and others factors that affect COX2/15-PGDH mediated PGE2 synthesis and degradation warrants further study. In addition, factors regulating gut permeability which are critical factors in regulating the amount of nanoparticle trafficking from the gut to the liver (41–43) needs further study to. Caution should be exercised when drawing conclusions regarding the biological effect of PGE2 on IDENs. Effects on the Wnt signaling pathway may be different when comparing PGE2 on IDENs to that of free form of PGE2 since miRNAs and other lipids are packed in the IDEN and may also contribute to the PGE2 mediated Wnt signaling pathway. Identifying whether IDEN miRNAs and/or lipids have a role in PGE2 mediated Wnt signaling pathway needs further study. 2) PGE2 carried by IDEN induces anergy of NKT cells not only through direct targeting of NKT cells but also through DCs activation via a TLR mediated pathway. The finding that IDENs can carry a number of therapeutic agents(44) and target antigen presenting cells may provide an avenue to pursue IDEN modulation of antigen presenting cell function and their role in gut immune tolerance.

These findings also open up a new avenue for investigating further the possible role of IDEN carrying other molecules released in gut that could induce both gut and liver immune tolerance. Furthermore, from therapeutic standard point, IDEN from intestines of other species may also be a useful vehicle for delivering therapeutic reagents(44, 45) to treat gastrointestinal diseases as well as diseases such as liver diseases treated by oral administration.

In this study, the finding that IDEN PGE2 activated the Wnt pathway and suppressed cytokine expression via inactivation of the GSK3/β-catenin pathway raises a number of important questions that need to be addressed in future studies. PGE2 binds and activates four G-protein-coupled E receptors (EP1–EP4). Unlike Ep1 and EP3, EP2 and EP4 have been shown to activate the GSK3/β-catenin pathway, as well as the adenylate cyclase-triggered cAMP/PKA/EPAC pathway(46–48). Whether IDEN PGE2 also suppresses IFN-γ and IL-4 expression via cAMP/PKA/CREB dependent pathway is unknown. If IDEN PGE2 does suppress cytokine production, also it needs to be determined if there is cross-talk with the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway at unidentified points to ultimately regulate the production these cytokines.

Finally, the Wnt signaling pathway is known to play a crucial role in prevention of autoimmune responses and in promotion of tumor growth. PGE2 is a potent signaling molecule that regulates immune tolerance and promotes tumor growth in addition to having a role in hematopoiesis, regulation of blood flow, renal filtration and blood pressure, regulation of mucosal integrity, and vascular permeability(49). Our findings provide a basis for further studies regarding the biological effects of PGE2 cross-talk with the Wnt/β-catenin pathway on these systems as well.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank The NIH Tetramer Facility for providing PBS-57 ligand complexed to CD1d monomers or tetramers, and Dr. Mitchell Kronenberg who provided the NKT1.2 hybridomas. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (RO1CA137037, R01CA107181, RO1AT004294, and RO1CA116092); the Louisville Veterans Administration Medical Center (VAMC) Merit Review Grants (H.-G.Z.); and a grant from the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. We thank Drs. Jerald Ainsworth and Fiona Hunter for editorial assistance

References

- 1.Venkataswamy MM, Porcelli SA. Lipid and glycolipid antigens of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells. Seminars in immunology. 2010;22:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawano T, Cui J, Koezuka Y, Toura I, Kaneko Y, Motoki K, Ueno H, et al. CD1d-restricted and TCR-mediated activation of valpha14 NKT cells by glycosylceramides. Science. 1997;278:1626–1629. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5343.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parekh VV, Wilson MT, Olivares-Villagomez D, Singh AK, Wu L, Wang CR, Joyce S, et al. Glycolipid antigen induces long-term natural killer T cell anergy in mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115:2572–2583. doi: 10.1172/JCI24762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crispe IN. The liver as a lymphoid organ. Annual review of immunology. 2009;27:147–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crispe IN. Hepatic T cells and liver tolerance. Nature reviews Immunology. 2003;3:51–62. doi: 10.1038/nri981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scanlon ST, Thomas SY, Ferreira CM, Bai L, Krausz T, Savage PB, Bendelac A. Airborne lipid antigens mobilize resident intravascular NKT cells to induce allergic airway inflammation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2011;208:2113–2124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pellicci DG, Clarke AJ, Patel O, Mallevaey T, Beddoe T, Le Nours J, Uldrich AP, et al. Recognition of beta-linked self glycolipids mediated by natural killer T cell antigen receptors. Nature immunology. 2011;12:827–833. doi: 10.1038/ni.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bousso P, Albert ML. Signal 0 for guided priming of CTLs: NKT cells do it too. Nature immunology. 2010;11:284–286. doi: 10.1038/ni0410-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinen T, Komai K, Muto G, Morita R, Inoue N, Yoshida H, Sekiya T, et al. Prostaglandin E2 and SOCS1 have a role in intestinal immune tolerance. Nature communications. 2011;2:190. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manicassamy S, Reizis B, Ravindran R, Nakaya H, Salazar-Gonzalez RM, Wang YC, Pulendran B. Activation of beta-catenin in dendritic cells regulates immunity versus tolerance in the intestine. Science. 2010;329:849–853. doi: 10.1126/science.1188510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeannet G, Boudousquie C, Gardiol N, Kang J, Huelsken J, Held W. Essential role of the Wnt pathway effector Tcf-1 for the establishment of functional CD8 T cell memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:9777–9782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914127107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gattinoni L, Zhong XS, Palmer DC, Ji Y, Hinrichs CS, Yu Z, Wrzesinski C, et al. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nature medicine. 2009;15:808–813. doi: 10.1038/nm.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding Y, Shen S, Lino AC, Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lafaille JJ. Beta-catenin stabilization extends regulatory T cell survival and induces anergy in nonregulatory T cells. Nature medicine. 2008;14:162–169. doi: 10.1038/nm1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ioannidis V, Beermann F, Clevers H, Held W. The beta-catenin--TCF-1 pathway ensures CD4(+)CD8(+) thymocyte survival. Nature immunology. 2001;2:691–697. doi: 10.1038/90623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu Q, Sharma A, Oh SY, Moon HG, Hossain MZ, Salay TM, Leeds KE, et al. T cell factor 1 initiates the T helper type 2 fate by inducing the transcription factor GATA-3 and repressing interferon-gamma. Nature immunology. 2009;10:992–999. doi: 10.1038/ni.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cen O, Ueda A, Guzman L, Jain J, Bassiri H, Nichols KE, Stein PL. The adaptor molecule signaling lymphocytic activation molecule-associated protein (SAP) regulates IFN-gamma and IL-4 production in V alpha 14 transgenic NKT cells via effects on GATA-3 and T-bet expression. Journal of immunology. 2009;182:1370–1378. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim PJ, Pai SY, Brigl M, Besra GS, Gumperz J, Ho IC. GATA-3 regulates the development and function of invariant NKT cells. Journal of immunology. 2006;177:6650–6659. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiang X, Poliakov A, Liu C, Liu Y, Deng ZB, Wang J, Cheng Z, et al. Induction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells by tumor exosomes. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 2009;124:2621–2633. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bu Q, Yan G, Deng P, Peng F, Lin H, Xu Y, Cao Z, et al. NMR-based metabonomic study of the subacute toxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in rats after oral administration. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:125105. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/12/125105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussain N. Fluorometric method for the simultaneous quantitation of differently-sized nanoparticles in rodent tissue. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2001;214:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(00)00631-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halder RC, Aguilera C, Maricic I, Kumar V. Type II NKT cell-mediated anergy induction in type I NKT cells prevents inflammatory liver disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:2302–2312. doi: 10.1172/JCI31602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beilke JN, Kuhl NR, Van Kaer L, Gill RG. NK cells promote islet allograft tolerance via a perforin-dependent mechanism. Nature medicine. 2005;11:1059–1065. doi: 10.1038/nm1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subleski JJ, Hall VL, Wolfe TB, Scarzello AJ, Weiss JM, Chan T, Hodge DL, et al. TCR-dependent and -independent activation underlie liver-specific regulation of NKT cells. Journal of immunology. 2011;186:838–847. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyznik AJ, Tupin E, Nagarajan NA, Her MJ, Benedict CA, Kronenberg M. Cutting edge: the mechanism of invariant NKT cell responses to viral danger signals. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:4452–4456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.7.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goessling W, North TE, Loewer S, Lord AM, Lee S, Stoick-Cooper CL, Weidinger G, et al. Genetic interaction of PGE2 and Wnt signaling regulates developmental specification of stem cells and regeneration. Cell. 2009;136:1136–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kojo S, Elly C, Harada Y, Langdon WY, Kronenberg M, Liu YC. Mechanisms of NKT cell anergy induction involve Cbl-b-promoted monoubiquitination of CARMA1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:17847–17851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904078106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lombardi V, Stock P, Singh AK, Kerzerho J, Yang W, Sullivan BA, Li X, et al. A CD1d-dependent antagonist inhibits the activation of invariant NKT cells and prevents development of allergen-induced airway hyperreactivity. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:2107–2115. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kremer M, Thomas E, Milton RJ, Perry AW, van Rooijen N, Wheeler MD, Zacks S, et al. Kupffer cell and interleukin-12-dependent loss of natural killer T cells in hepatosteatosis. Hepatology. 2010;51:130–141. doi: 10.1002/hep.23292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortaldo JR, Young HA. IL-18 as critical co-stimulatory molecules in modulating the immune response of ITAM bearing lymphocytes. Seminars in immunology. 2006;18:193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brigl M, Bry L, Kent SC, Gumperz JE, Brenner MB. Mechanism of CD1d-restricted natural killer T cell activation during microbial infection. Nature immunology. 2003;4:1230–1237. doi: 10.1038/ni1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang GJ, Liu Y, Qin A, Shah SV, Deng ZB, Xiang X, Cheng Z, et al. Thymus exosomes-like particles induce regulatory T cells. Journal of immunology. 2008;181:5242–5248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.8.5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang HG, Liu C, Su K, Yu S, Zhang L, Zhang S, Wang J, et al. A membrane form of TNF-alpha presented by exosomes delays T cell activation-induced cell death. Journal of immunology. 2006;176:7385–7393. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Niel G, Mallegol J, Bevilacqua C, Candalh C, Brugiere S, Tomaskovic-Crook E, Heath JK, et al. Intestinal epithelial exosomes carry MHC class II/peptides able to inform the immune system in mice. Gut. 2003;52:1690–1697. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.12.1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heyman M. Symposium on ‘dietary influences on mucosal immunity’. How dietary antigens access the mucosal immune system. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 2001;60:419–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarlo K, Blackburn KL, Clark ED, Grothaus J, Chaney J, Neu S, Flood J, et al. Tissue distribution of 20 nm, 100 nm and 1000 nm fluorescent polystyrene latex nanospheres following acute systemic or acute and repeat airway exposure in the rat. Toxicology. 2009;263:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghodgaonkar RB, Dubin NH, Blake DA, King TM. 13, 14-dihydro-15-keto-prostaglandin F2alpha concentrations in human plasma and amniotic fluid. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1979;134:265–269. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)33031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bygdeman M. Pharmacokinetics of prostaglandins. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2003;17:707–716. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6934(03)00043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phipps RP, Stein SH, Roper RL. A new view of prostaglandin E regulation of the immune response. Immunology today. 1991;12:349–352. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(91)90064-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tai HH, Ensor CM, Tong M, Zhou H, Yan F. Prostaglandin catabolizing enzymes. Prostaglandins & other lipid mediators. 2002;68–69:483–493. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, Rajendran L, Wenzel D, Wieland F, Schwille P, et al. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes. Science. 2008;319:1244–1247. doi: 10.1126/science.1153124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vllasaliu D, Fowler R, Garnett M, Eaton M, Stolnik S. Barrier characteristics of epithelial cultures modelling the airway and intestinal mucosa: a comparison. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2011;415:579–585. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siew A, Le H, Thiovolet M, Gellert P, Schatzlein A, Uchegbu I. Enhanced oral absorption of hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs using quaternary ammonium palmitoyl glycol chitosan nanoparticles. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2012;9:14–28. doi: 10.1021/mp200469a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bimbo LM, Makila E, Laaksonen T, Lehto VP, Salonen J, Hirvonen J, Santos HA. Drug permeation across intestinal epithelial cells using porous silicon nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2625–2633. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhuang X, Xiang X, Grizzle W, Sun D, Zhang S, Axtell RC, Ju S, et al. Treatment of brain inflammatory diseases by delivering exosome encapsulated anti-inflammatory drugs from the nasal region to the brain. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2011;19:1769–1779. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun D, Zhuang X, Xiang X, Liu Y, Zhang S, Liu C, Barnes S, et al. A novel nanoparticle drug delivery system: the anti-inflammatory activity of curcumin is enhanced when encapsulated in exosomes. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2010;18:1606–1614. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang SK, Wettlaufer SH, Chung J, Peters-Golden M. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits specific lung fibroblast functions via selective actions of PKA and Epac-1. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2008;39:482–489. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0080OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, Daaka Y. PGE2 promotes angiogenesis through EP4 and PKA Cgamma pathway. Blood. 2011;118:5355–5364. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-350587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oberprieler NG, Lemeer S, Kalland ME, Torgersen KM, Heck AJ, Tasken K. High-resolution mapping of prostaglandin E2-dependent signaling networks identifies a constitutively active PKA signaling node in CD8+CD45RO+ T cells. Blood. 2010;116:2253–2265. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalinski P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin E2. Journal of immunology. 2012;188:21–28. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.