Abstract

African American male adolescents’ involvement with multiple sexual partners has important implications for public health as well as for their development of ideas regarding masculinity and sexuality. The purpose of this study was to test hypotheses regarding the pathways through which racial discrimination affects African American adolescents’ involvement with multiple sexual partners. We hypothesized that racial discrimination would engender psychological distress, which would promote attitudes and peer affiliations conducive to multiple sexual partnerships. The study also examined the protective influence of parenting practices in buffering the influence of contextual stressors. Participants were 221 African American male youth who provided data at ages 16 and 18; their parents provided data on family socioeconomic disadvantages. Of these young men, 18.5% reported having 3 or more sexual partners during the past 3 months. Structural equation models indicated that racial discrimination contributed to sexual activity with multiple partners by inducing psychological distress, which in turn affected attitudes and peer affiliations conducive to multiple partners. The experience of protective parenting, which included racial socialization, closeness and harmony in parent-child relationships, and parental monitoring, buffered the influence of racial discrimination on psychological distress. These findings suggest targets for prevention programming and underscore the importance of efforts to reduce young men’s experience with racial discrimination.

Keywords: racial discrimination, male, African Americans, multiple sexual partners

During adolescence, an individual’s sense of personal efficacy to achieve goals in life and perceptions of the world as fair, equitable, and just are significantly influenced by his or her social experiences and environment. Unfortunately, the social environments of many minority youth include experiences with racial discrimination that have the potential to foster emotional distress and a sense of powerlessness. In turn, these perceptions may influence youth health outcomes and racial/ethnic disparities by promoting psychological distress (e.g., frustration, anger, low sense of personal agency) that can affect health behavior and the development of personal relationships (Sanders-Phillips, Settles-Reaves, Walker, & Brownlow, 2009). An emerging body of empirical research documents the pernicious influence of racial discrimination on adolescent adjustment and health-related behavior, among minority youth in general and African American youth in particular (Mays, Cochran, & Barnes, 2007). Exposure to racial discrimination has been associated with increases in adjustment problems among African American youth, including depressive symptoms, substance use, and externalizing behavior (Brody et al., 2006; Gibbons et al., 2010; Gibbons et al., 2012; Lambert, Herman, Bynum, & Ialongo, 2009). Several recent studies have linked exposure to racial discrimination to African American youth’s engagement in sexual risk behaviors involving numbers of sexual partners, condom use, and concurrent substance use and sexual activity (Kogan et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2011; Stevens-Watkins, Brown-Wright, & Tyler, 2011). Studies also suggest that, compared with African American female youth, racial discrimination may have more profound effects on African American male youth’s involvement in risk behaviors such as substance use (Brody, Kogan, & Chen, 2012) and risky sex (Kogan et al., 2010).

In the present study, we investigated the association between male African American adolescents’ reported exposure to racial discrimination at age 16 and their involvement with multiple sexual partners at age 19. We focused on youth’s having multiple sexual partners for several reasons. Epidemiological surveillance indicates that, compared with other racial/ethnic and gender subgroups, African American adolescent men are more likely to report high numbers of sexual partners (Eaton et al., 2012; Laumann & Youm, 1999). Multiple sexual partnerships pose a significant health threat to young men and to African American communities because they are linked to elevated rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including HIV (Adimora, Schoenbach, & Doherty, 2006). African American youth and young adults experience disproportionately high rates of STIs compared with those in other racial/ethnic groups. Involvement with multiple sexual partners also increases the likelihood that young men will become fathers during adolescence outside of committed relationships (Kogan et al., 2013). From developmental and gender studies perspectives, the pursuit of multiple sexual partners in adolescence may reflect the adoption of a masculine ideal characterized by sexual conquest rather than intimacy (Bowleg, 2004).

Although several studies suggest a link between exposure to racial discrimination and African American adolescents’ involvement with multiple sexual partners, this research base is significantly limited. First, little research has documented prospectively the effects of discrimination specifically with male youth. Well-designed longitudinal studies that can account for multiple confounding factors are required to increase researchers’ confidence in identifying discrimination as a risk factor for having multiple sexual partners. Second, given the hypothesized link between exposure to racial discrimination and having multiple sexual partners, little is known about the mechanisms of action responsible for this association. Studies are needed that specify how racial discrimination affects young men in ways that encourage multiple partnerships. Third, male adolescents’ development is influenced by multiple risk and protective processes. Discrimination does not influence all young men equally, and the moderators of this effect can provide important clues about protecting young men from discrimination-associated risks. Thus, the present research was designed to test hypotheses regarding risk and protective mechanisms associated with the link between male African American adolescents’ exposure to racial discrimination and their involvement with multiple sexual partners.

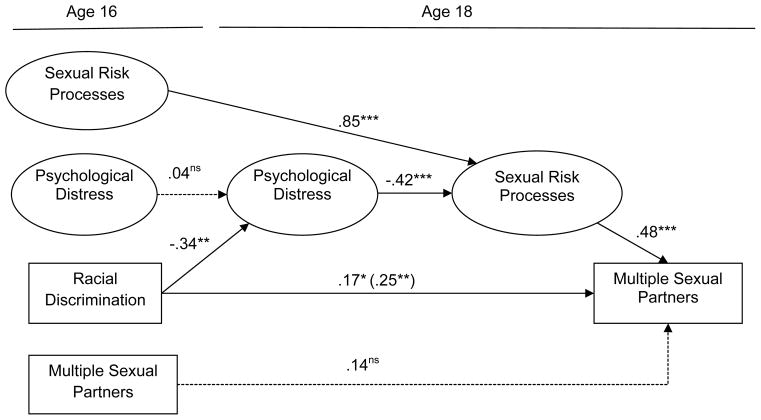

Figure 1 presents a conceptual model that summarizes specific study hypotheses. This model was informed by Vandello and colleagues’ research on “precarious manhood” (Bosson & Vandello, 2011; Bosson, Vandello, Burnaford, Weaver, & Wasti, 2009; Vandello & Bosson, 2013; Vandello, Bosson, Cohen, Burnaford, & Weaver, 2008) and by Anderson’s (1989, 1990) research on the mechanisms linking challenging social environments to hypermasculine displays of sexuality. The notion of precarious manhood suggests that the assertion, safeguarding, and maintenance of masculinity requires a continual display of role-typical behavior. When a man detects a threat to his masculine status, he seeks to reestablish that status both in his own and others’ regard. Having multiple sexual partners is one means of reestablishing threatened masculine status. We conceptualize racial discrimination as a potential threat to young African American men’s sense of masculine status that affects the personal and contextual mediating factors that Anderson suggested.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

The model in Figure 1 specifies an initial link between male African American youth’s exposure to racial discrimination and psychological distress. Studies document that psychological distress induced by racial discrimination commonly includes a sense of frustration and powerlessness (Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000). Given that a sense of personal efficacy and mastery of one’s circumstances is central to many conceptualizations of masculine gender role expression (Goff, Di Leone, & Kahn, 2012), young men were hypothesized to cope with discrimination-induced distress by adopting two interrelated sexual risk processes: attitudes that support having multiple sexual partners and affiliations with peers who endorse those attitudes. These sexual risk processes were expected to predict proximally young men’s reports of involvement with multiple sexual partners. The model in Figure 1 also includes the proposal that not all young men exposed to racial discrimination will report having multiple sexual partners. We considered protective parenting practices as a buffer against the negative influence of racial discrimination on youth’s psychological distress. In the following sections, we review the empirical support for each path presented in Figure 1.

The Psychological Consequences of Racial Discrimination

Racial discrimination refers to unfair treatment because of minority status by individuals from a dominant group (Feagin & Eckberg, 1980). Harrell (2000) described a type of discrimination involving “microstressors,” everyday experiences with racism that include being ignored, overlooked, or mistreated in ways that lead to feelings of demoralization and dehumanization. These experiences are often minimized and not considered serious enough to address, but their accumulation has significant consequences for both mental (Brody et al., 2006) and physical (Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003) health. During adolescence, young people experience rapid development in their self-concepts and ethnic identities, while their cognitive development increases their awareness of unjust treatment (Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000; Gibbons et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2011). Discriminatory experiences thus become increasingly recognizable to young people and have the potential to affect their developing sense of personal efficacy.

In the model presented in Figure 1, we hypothesized that racial discrimination affects men’s sexual behavior indirectly by engendering psychological distress. Multiple studies document the psychological distress that racial discrimination induces among African Americans, both adults (Brown et al., 2000; Carter & Forsyth, 2010; Utsey, Ponterotto, Reynolds, & Cancelli, 2000) and adolescents (Gibbons et al., 2007, 2010; Roberts, 2011). Racially induced psychological distress integrates aspects of negative emotionality with behavioral control, including self-efficacy and optimism (Bowman, 1984; Uomoto, 1986; Williams et al., 2012). The close links between negative affect and self-regulation or self-efficacy are apparent in “learned helplessness” models of stress reactions (Maier and Seligman, 1976). Success in setting goals, striving to attain them, and achieving them is reciprocally associated with positive affect in adolescents (Buckner, Mezzacappa, & Beardslee, 2009; Scott et al., 2008). Conversely, adolescents are particularly vulnerable to cycles of negative affect when goals seem unattainable or simply not worth setting.

Racial Discrimination and Masculinity

The psychological distress induced by racial discrimination is thought to affect sexual behavior by posing a threat to masculinity. Although masculinity is a multidimensional construct, many conceptualizations of masculine gender role expression, including those that focus specifically on African American men (Hammond & Mattis 2005), include a sense of confidence, optimism, and mastery as central components (Choi, 2004; Goff, Di Leone, & Kahn, 2012; Long, 1989; Robins, 1986). When young men are confronted with the frustration and sense of helplessness that discrimination occasions, we expect that some will seek ways to reassert status and a sense of personal esteem. The notion of racial discrimination as a threat to masculinity was recently investigated experimentally with African American and Caucasian men. Goff and colleagues (2012) found that exposure to race-based insults in a laboratory situation increased hypermasculine behavior among African American, but not Caucasian, men. Goff et al. reasoned that the pervasiveness of racial discrimination differentially affected men’s responses to specific instances of discrimination. Caucasian men were buffered from discrimination-associated masculinity threat by their social status, in which discrimination was relatively rare and posed far less of an overall barrier to achieving life goals.

Consistent with these findings, in the conceptual model presented in Figure 1 we hypothesized that experiences with racial discrimination would be linked to increases in psychosocial distress that, in turn, would encourage young men to adopt attitudes that encourage involvement with multiple sexual partners and to affiliate with peers who hold the same values. Anderson (1989, 1990) elaborated the mechanisms linking psychological distress to male sexuality. He maintained that many young men who experience discrimination and other threats to personal esteem are drawn to identify and affiliate with peers who hold negative attitudes towards intimacy-promoting relationship qualities such as love and commitment. These highly influential peer groups promote a view of sex as a game, in which women are tokens and men compete with each other to gain social status (Giordano, Longmore, Manning, & Northcutt, 2009). According to Anderson (1989), peers constitute a critical component in the adoption of these attitudes, as youth come to care more about the opinions of male peers than those of female romantic partners. Peer groups become the primary referent for evaluating behavior in sexual relationships and one’s own status and esteem. We thus hypothesized that, when confronted with discrimination-induced psychological distress, young men may simultaneously adopt attitudes that condone multiple sexual partners and affiliate with peers who reinforce these attitudes. Other research has also indicated that adolescents’ acceptance of risky behaviors and affiliation with risk-taking peer groups are proximal, robust predictors of sexual behavior (Kogan et al., 2011).

The Protective Influence of Parenting

Powerful factors that protect rural African American adolescents from high-risk behaviors originate in the family environment, particularly in parents’ caregiving practices (Brody, Dorsey, Forehand, & Armistead, 2002; Brody et al., 2001; Murry & Brody, 1999). Based upon patterns of family life established in African societies and modified in response to enslavement in America (Sudarkasa, 1988), reliance on family and extended kin networks has supported African Americans through multiple social transitions (Boyd-Franklin, 2003; McLoyd et al. 2007). African Americans’ family-centered orientation has been found to protect adolescents from the influences of economic distress (Wills, Gibbons, Gerrard, Murry, & Brody, 2003) and racial discrimination (Brody et al., 2006) on youth development. In studies of rural African American families, Brody and colleagues (Brody, Kim, Murry, & Brown, 2004; Brody, Kogan, & Grange, 2012) identified a cluster of protective parenting practices that includes close, involved relationships, parental monitoring, communication, and a sense of pride in being African American that includes preparation for handling discrimination. These parenting practices protect African American youth from dangerous surroundings, hazardous experiences, and involvement in antisocial activity (Brody et al., 2004; Brody, Kim, Murry, & Brown, 2005; Simons, Chen, Stewart, & Brody, 2003) while decreasing their likelihood of developing depressive symptoms (Kim et al., 2003; Simons et al., 2002). Therefore, we expect that, for youth who receive high levels of protective parenting, the influence of racial discrimination on psychological distress will be attenuated, thus preventing the development of sexual risk processes.

Racial Discrimination and Confounding Processes

The experience of racial discrimination is most commonly assessed via self-report. A person’s perception of discrimination and the effects of a given interaction depend greatly on individual differences. Sources of variability in perceived discrimination may provide alternative explanations for its effects. Researchers who investigate the effects of racial discrimination, however, seldom consider the personality and behavioral factors that can influence youth’s likelihood of noting, attending to, and reporting experiences with discrimination. We consider two such factors in our study. First, discriminatory experiences can induce anger and hostility; in turn, these emotions can heighten recognition and salience of future experiences with discrimination (Brondolo et al., 2008). When considering the influence of racial discrimination as an effect on health and development, it is thus useful to disentangle state anger or hostility from daily experiences. From the standpoint of behavioral processes, discrimination covaries with youth’s involvement in delinquent behaviors (Simons et al., 2003). Youth who are involved in delinquency may elicit hostility from authority figures and distrust from community members. Effects of reported discrimination on outcomes may thus be, in part, a product of involvement with delinquent behavior. Thus, co-occurring hostility or delinquency render difficult discernment of the effects of self-reported discriminatory experiences per se versus confounding variables. In our investigation, we account for the potential of youth’s self-reported hostility and delinquent behavior to inflate reports of discrimination, permitting a more refined analysis of the predictive salience of perceived discrimination for sexual partnerships. We also considered the potential influence of socioeconomic disadvantage, a robust risk factor for having multiple sexual partners (McLoyd, 1990; Wickrama, Merten, & Wickrama, 2012).

Methods

Study hypotheses were tested with data from 221 African American male adolescents recruited randomly from lists provided by public high schools in six rural Georgia counties. Youth were enrolled in the study when they were 16.0 (SD = .60) years of age; they provided self-report data at ages 16 and 18 (M =17.56, SD = .57) years. Data were collected in the context of a family-based prevention study (Kogan, Brody, et al., 2012). Among the participants, 112 participated in the index intervention and 109 participated in an attention control. Neither intervention assignment nor intervention dose was associated with any study variable. For the present study, assignment to the prevention or attention-control condition was controlled in all data analyses. At age 16, among youth’s families, median household gross monthly income was $2,016.00 (SD = $4,353.86) and mean monthly per capita gross income was $887.54 (SD = 1,578.98). Although youth’s caregivers worked an average of 38.5 hours per week, 42% of the families lived below federal poverty standards and another 15% lived within 150% of the poverty threshold; they could be described as working poor (Boatright, 2009).

Procedures

Community liaisons, African American community members who resided in the counties where the participants lived, contacted families and enrolled them in the study. Selected on the basis of their social contacts and standing in the neighborhood, community liaisons worked with the researchers on participant recruitment and retention. At each data collection, caregivers gave written consent to minor youth’s participation, and youth gave written assent or consent to their own participation. To enhance rapport and cultural understanding, African American university students and community members served as field researchers to collect data. During each assessment, each family had one home visit that lasted 2 hours. At the home visit, self-report questionnaires were administered privately via audio computer-assisted self-interviewing technology on a laptop computer. After each assessment, youth were paid $50 and parents were paid $100. All study protocols were approved by the university IRB.

Measures

Multiple sexual partners

At ages 16 and 18, participants reported the numbers of partners with whom they had engaged in sexual activity during the past 3 months. To distinguish youth who were likely to be involved with multiple sexual partners from those who transitioned from one monogamous relationship to another, the count variable was dichotomized, with 1 = 3 or more partners and 0 = less than 3 partners.

Racial discrimination

Perceived racial discrimination was assessed at age 16 and age 18 with a 9-item scale adapted from Williams’s (Williams & Williams-Morris, 2000) research on racially based microstressors. Focus groups of community members identified microstressors that occurred most frequently and suggested wording changes to increase clarity (Murry & Brody, 2004). Youth reported how often in the past 12 months each stressor occurred, from 1 (never) to 4 (frequently). Example items included, “How often have you been treated rudely or disrespectfully because of your race?” “How often have you been watched or followed while in public because of your race?” and “How often have your ideas or opinions been put down, ignored, or belittled because of your race?” Cronbach’s alpha was .90.

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was operationalized at ages 16 and 18 as a latent construct composed of two measures: the State Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1996) and the Negative Affect subscale of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression (CES–D; Radloff, 1977) scale. The State Hope Scale assesses the extent to which participants had formed goals and felt efficacious in pursuing them. Participants rated six items on a scale ranging from 1 (really false) to 5 (really true); example items include, “At the present time I am energetically pursuing my goals,” and “I can think of many ways to reach my current goals.” Cronbach’s alpha was .80 at age 16 and .87 at age 18. The CES–D is a well-validated assessment of depressive symptoms that is strongly linked with optimism and negative affectivity (Lincoln, Taylor, Watkins, & Chatters, 2011; Sultan & Fisher, 2010). The Negative Affect subscale includes 7 items; respondents use a scale ranging from 1 (rarely or none of the time) to 5 (most or all of the time) to indicate the extent to which they experienced each symptom during the past week. Sample items included, “How often did you feel fearful?” “How often did you feel sad?” and “How often did you think your life was a failure?”

Sexual risk processes

The sexual risk processes construct was operationalized at ages 16 and 18 using items that reflected youth’s attitudes towards risky sexual behavior and their perceptions of their peers’ behaviors and attitudes. Youth responded to three items adapted from the Tolerance for Deviance Measure: “How often is it okay for someone your age to have sex?” “How often is it okay for someone your age to have sex with someone you do not know well?” and “How often is it okay is it for someone your age to have sex without a condom?” The response scale ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Cronbach’s alpha was .79 at age 16 and .78 at age 18. Youth also responded to five items regarding their close friends’ behaviors and attitudes. Two items began with the stem, “How many of your close friends in the last 3 months:” followed by “had sex with someone they did not know well?” and “have gotten a girl pregnant?” The response scale ranged from 1 (none of them) to 3 (all of them). The other three items began with the stem, “How many of your friends believe:” followed by “it’s okay to be abstinent, that is, choose not to have sex?” (reverse coded), “it’s okay to have sex with someone you just met?” and “cheating on your partner is okay?” The response scale ranged from 1 (none of them) to 5 (all of them). The five items were standardized and summed. Cronbach’s alpha was .66 at age 16 and .65 at age 18.

Protective parenting

At age 16, youth completed a protective parenting instrument (Brody et al., 2006), which was composed of summed and standardized scores from scales that assess caregiver-youth interaction quality (6 items), racial socialization practices (11 items), and parental monitoring (5 items). Interaction quality items were adapted from the Interactional Behavior questionnaire (Prinz, Foster, Kent, & O’Leary, 1979); they included, “You and your caregiver reach an agreement during arguments,” and “You are well behaved in your discussions with your caregiver.” Racial socialization items were derived from Hughes’ (2003) measure and included items about preparing for discrimination (e.g., “How often did your caregiver talk with you about the possibility that some people might treat you badly or unfairly because of your race?”) and instilling cultural pride (e.g., “How often did your caregiver talk with you about important people or events in the history of your racial group?”). Monitoring items (Brody et al., 2006) included, “How often does your caregiver know when you get in trouble at school or someplace else away from home?” and “How often does your caregiver know when you do not do the things s/he asked you to do?” Each item was rated on a response set that ranged from 1 (always) to 4 (never). Alpha for the 22-item scale was .81.

Control variables

Control variables were assessed at age 16. Hostility was assessed with an eight-item scale (Joe, Broome, Rowan-Szal, & Simpson, 2002). On a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), participants responded to items that included, “You have a hot temper,” and “You feel a lot of anger inside you.” Cronbach’s alpha was .86. Youth also completed a checklist indicating the number of times in the past 6 months they had engaged in each of 13 delinquent behaviors. The checklist was based on Elliot’s (Elliott, Ageton, & Huizinga, 1985) National Youth Survey and comprised items that demonstrated the greatest variability in our prior studies with rural African American youth. Example behaviors included, “taken something worth $25 or more that didn’t belong to you,” and “purposefully damaged or destroyed property that didn’t belong to you.” The frequency of each behavior was summed across the 13 items to form the conduct problems score. Cronbach’s alpha was .71.

At the age 16 time point, a socioeconomic disadvantage index was formed from the combination of six dichotomous variables based on parents’ reports of household demographic information and experience of economic hardship; this index has been used in previous studies (Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012). The variables were family poverty based on federal guidelines, caregiver unemployment, receipt of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, caregiver single-parent status, caregiver education level less than high school graduation, and caregiver-reported inadequacy of family income. The number of variables a parent reported constituted the family’s score on the index; scores ranged from 0 to 6 (M = 2.56, SD = 1.57).

Plan of Analysis

Study hypotheses were tested with logistic structural equation modeling using Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Models were estimated using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedures, which test the model against all available data. Thus, data missing due to attrition do not produce missing cases; the interview protocols rendered nonresponse to individual items negligible. The measurement model was examined with a confirmatory factor analysis prior to hypothesis testing. The model presented in Figure 1 was then estimated with protective parenting excluded; the significance of indirect pathways was tested with bootstrapping. We specified an autoregressive model controlling for age 16 levels of sexual partners and mediating factors; this design, which controls for residual variability at age 18, indexes change over time. Baseline reports of socioeconomic disadvantage, hostility, and peer delinquency were also controlled. We then executed a second model that included protective parenting and a protective parenting × discrimination interaction term as predictors of psychological distress. Model fit was assessed using chi-square, χ2/df < 2.0, comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

Results

Of the 221 youth who provided data at age 16, 205 were retained at age 18. Analyses were conducted comparing youth who left or remained in the study on all study variables. No differences emerged. This analysis supports the use of FIML estimation in the structural models. At age 18, most young men (81.5%) reported fewer than 3 partners in the last 3 months; the remaining youth (18.5%) reported having 3 or more sexual partners.

We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis of the measurement model composed of two latent variables: psychological distress (indicators, State Hope Scale and CES–D Negative Affect subscale) and sexual risk processes (indicators, attitudes scale and peer scale). The data fit the measurement model well: χ2 (14) = 13.89, p = ns; χ2/df = .99; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00 (0, .06). All factor loadings were significant and in the expected direction, λ > .4. Associations among study variables, with means and standard deviations, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SES disadvantage (16) | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 2. Conduct problems (16) | .10 | -- | |||||||||||||

| 3. Hostility (16) | −.02 | .39*** | -- | ||||||||||||

| 4. Racial discrimination (16) | −.03 | .08 | .25*** | -- | |||||||||||

| 5. Protective parenting (16) | −.21** | −.19** | −.30*** | .06 | -- | ||||||||||

| 6. State hope (16) | −.15* | −.17* | −.17* | −.04 | .27*** | -- | |||||||||

| 7. State hope (18) | −.13 | −.17* | −.20** | −.17* | .24** | .33*** | -- | ||||||||

| 8. Negative affect (16) | .09 | .30*** | .35*** | .23** | −.12 | −.18** | −.16* | -- | |||||||

| 9. Negative affect (18) | .06 | .15* | .14* | .25*** | −.02 | −.08 | −.22** | .30*** | -- | ||||||

| 10. Attitude toward sex (16) | −.02 | .03 | .29*** | .09 | −.05 | −.10 | −.07 | .03 | −.05 | -- | |||||

| 11. Attitude toward sex (18) | −.02 | .13 | .15* | .14* | −.05 | −.03 | −.11 | .00 | .17* | .45*** | -- | ||||

| 12. Peers’ sexual behaviors (16) | −.17* | .12 | .38*** | .16* | −.16* | −.10 | −.09 | .17* | .05 | .51*** | .34*** | -- | |||

| 13. Peers’ sexual behaviors (18) | −.08 | .09 | .14* | .11 | −.16* | −.03 | −.09 | .11 | .26*** | .35*** | .56*** | .49*** | -- | ||

| 14. Multiple sexual partners (16) | −.04 | .16* | .20** | .05 | −.16* | −.08 | −.12 | −.08 | .01 | .09 | .06 | .24*** | .19** | -- | |

| 15. Multiple sexual partners (18) | .11 | .11 | .18* | .23** | −.11 | −.02 | −.17* | .05 | .12 | .20** | .29*** | .26*** | .29*** | .20** | -- |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Mean | 2.56 | 7.37 | 14.96 | 13.46 | 0 | 24.42 | 24.53 | 2.18 | 2.20 | 1.95 | 2.07 | 0 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.18 |

| SD | 1.57 | 15.06 | 5.35 | 5.32 | 9.81 | 3.26 | 3.73 | 3.12 | 3.50 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.25 | 0.39 |

Note. Numbers in parentheses refer to age in years.

p≤.05.

p≤.01.

p≤0.001.

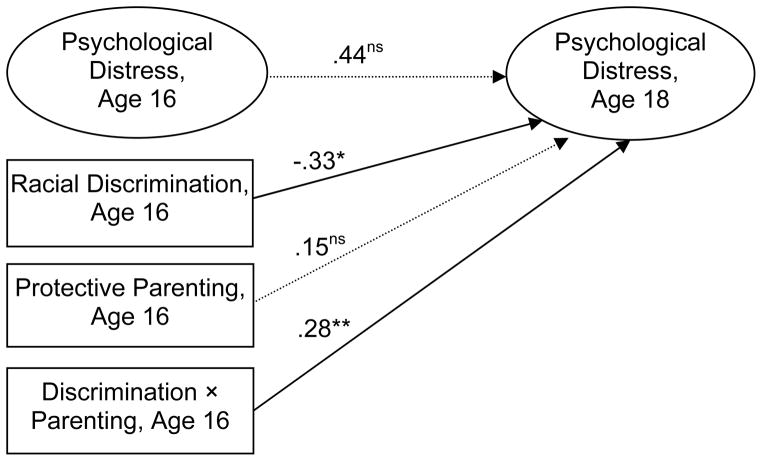

Figure 2 presents the indirect effects model. The data fit the model well: χ2(44) = 54.00, p = .144; χ2/df = .81; CFI = .98; RMSEA = .032 (0, .06). As hypothesized, racial discrimination at age 16 predicted, negatively, changes in psychological distress from age 16 to age 18, β = −.25, p < .01. Psychological distress predicted, negatively, change in youth’s sexual risk processes from age 16 to age 18, β = −.44, p < .001. Changes in sexual risk processes constituted a proximal predictor of multiple sexual partnerships, β = .48, p < .001. The indirect effect of racial discrimination on multiple sexual partnerships via changes in psychological distress and sexual risk processes was .053, SE = .024, p = .028. Partial mediation also was indicated by a comparison of the age 16 estimate of racial discrimination on multiple sexual partners without mediators, β = .25, p < .01, versus the direct effect in the mode with mediators present, β = .17, p <.05.

Figure 2.

Indirect effects model predicting sexual partners. Socioeconomic disadvantage, risk behavior, and hostility are controlled. Dotted lines indicate nonsignificant pathways. *p≤.05. **p≤.01. ***p≤.001.

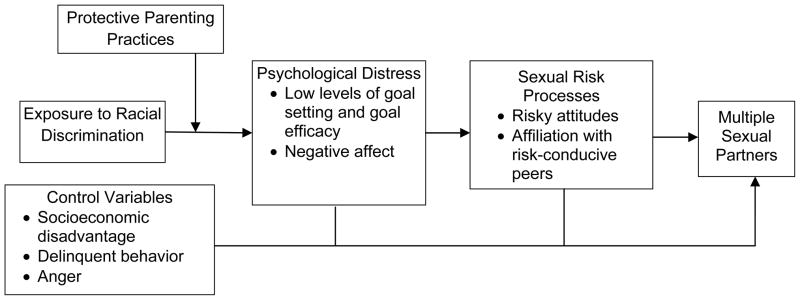

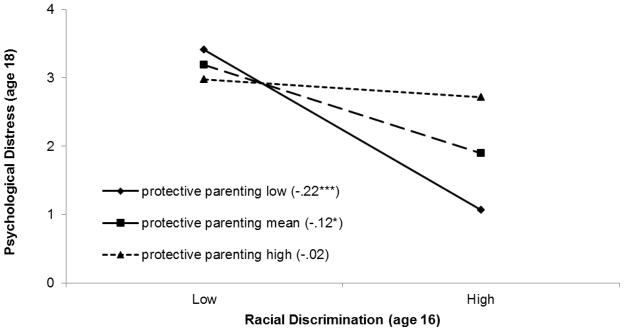

Figure 3 presents the results of the test of the moderating influence of protective parenting on the association between racial discrimination and psychological distress. The interaction term combining racial discrimination and protective parenting significantly predicted changes in psychological distress, β = .25, p < .01. This interaction is described in Figure 4. For youth with high levels of protective parenting, the influence of racial discrimination was negligible. In contrast, racial discrimination was particularly pernicious for youth who experienced low levels of protective parenting.

Figure 3.

Effect of the interaction between discrimination and protective parenting on changes in psychological distress. Dotted lines indicate nonsignificant pathways. *p≤.05. **p≤.01. *** p≤.001.

Figure 4.

The effect of racial discrimination on psychological distress by levels of protective parenting. Numbers in parentheses refer to simple slopes for low (1 standard deviation below the mean), mean, and high (1 standard deviation above the mean) levels of protective parenting. **p≤.01. *** p≤.001.

Discussion

Research and theory suggest that racial discrimination during adolescence is stressful and demeaning, with the potential to undermine young African American men’s sense of psychological distress. For young men, stressors that threaten their sense of competence may be interpreted in terms of threats to masculinity. This is particularly challenging for adolescent men due to multiple developmental changes that can result in heightened self-consciousness and increased anxiety regarding gender identity and self-presentation. Research has identified a link between masculinity threats and men’s engagement in behaviors to enhance their sense of status and efficacy through exaggerated displays of masculinity, such as involvement with multiple sexual partners. We tested a model specifying the pathways through which racial discrimination was associated with having multiple sexual partners among African American men during late adolescence. Study findings supported our hypotheses. Experiences with discrimination predicted psychological distress, which in turn predicted the development of attitudes and peer affiliations supportive of having multiple sexual partners.

Our results are consistent with Anderson’s (1989) and Spencer’s (Spencer, Fegley, Harpalani, & Seaton, 2004) perspectives regarding young men’s development of sexuality in adverse circumstances. These researchers proposed that the sense of frustration and helplessness that racial discrimination induces may lead some youth to adopt risky attitudes and peer affiliations. From a precarious manhood perspective, the findings suggest that racial discrimination may constitute a threat to masculinity that led some men to cope by seeking “sexual conquests.” According to Anderson and Spencer, the transformation of intrapersonal distress into a heightened focus on and pursuit of sexual conquests represents a coping mechanism intended to establish status and esteem in the face of a threat to one’s sense of personhood. To the extent that racial discrimination poses a threat to a young man’s sense of masculinity and status, sexual conquest may become an avenue for affirming his right to esteem and status. Wolfe (2003) postulated that such “hypermasculine” displays and behaviors play a largely compensatory role, providing a show of masculinity as a reaction against the negative messages about themselves that young African American men receive.

Although racial discrimination was associated with increased psychological distress, not all young men who experienced racial discrimination reported multiple sexual partnerships. Studies indicate that parenting practices that include racial socialization, involved/supportive relationships, and close parental monitoring can protect youth from the influences of racial discrimination on psychological functioning (Brody et al., 2006) and substance use (Gibbons et al., 2010). Consistent with these studies, we found that protective parenting practices also protected male adolescents from the influence of racial discrimination on psychological distress. When youth received high levels of protective parenting, racial discrimination had no discernable influence on their levels of psychological distress. The validation of family protective processes suggests the importance of targeting parenting practices in interventions designed to protect African American male adolescents from the consequences of racial discrimination. Specifically, interventions should focus on the enrichment of parent-youth interactions, parents’ provision of racial socialization, and parental monitoring. A number of evidence-based programs have proven effective in enhancing these processes (Coatsworth, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2002; Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012; Stormshak, Dishion, Light, & Yasui, 2005). For example, the Strong African American Families–Teen program for youth age 14–16 years affects family relationships processes (Kogan, Brody, et al., 2012) and has been shown to increase safer sex (Kogan, Yu, et al., 2012). The identified risk mechanisms in this study also point to the importance of programs designed to augment young men’s sense of personal agency to meet valued life goals and counteract discrimination-induced psychological distress. The importance of same-sex peers in sustaining and reinforcing attitudes that celebrate multiple sexual partners suggests the value of developing ways to change peer norms in these groups or encouraging selection of peers with more flexible norms for masculine behavior.

The present study requires important caveats regarding interpretation. First, although the results document an important pathway that accounts for within-group variability in multiple sexual partnerships, it is important to note that the vast majority of African American youth in this sample did not report multiple partners. Second, behaviors and attitudes focused on sexual conquest are by no means limited to African American youth. Due to the public health significance of multiple sexual partnerships and their prevalence among minority youth, little attention has been given to this behavior among Caucasian youth. This omission can perpetuate stereotypes about African American men and Latinos by stigmatizing their sexual behavior as problematic while similar behavior among Caucasian men is virtually unacknowledged and unexamined. Such a view also minimizes the critical importance of inequities in the social contexts that create the conditions under which such behaviors are most likely to be pursued. The present study, along with other work (Bowleg, 2004; Hammond, 2012), highlights the power of contextual factors such as discrimination to alter personal well-being in ways that later become public health problems.

Several limitations in the present study should be noted. Although theory regarding masculinity ideologies informed our predictions, and pursuit of multiple sexual partners is extensively accepted as an expression of certain masculine ideologies (Chu, Porche, & Tolman, 2005; Noar & Morokoff, 2002), data on young men’s ideologies concerning masculinity were not available. Future research that provides a more in-depth view of men’s self-reported conformity to specific masculine roles and ideological orientations would complement and extend the present study. We conceptualized psychological distress as a combination of negative affect and low levels of state hope. It is also plausible that discrimination-induced changes in hopefulness and efficacy could lead to problems with affect regulation. Research that includes laboratory and physiological designs is indicated to characterize more precisely the effects of discrimination.

In the present study, we focused on protective parenting as factor buffering youth from the influence of discrimination. Optimism, self-regulation, and racial identity processes have also been identified as important protective factors. These processes may have affected heterogeneity in response to discrimination in the present study, suggesting plausible alternative hypotheses for additional research. We also focused on one primary caregiver, almost always a mother. To date, little is known about the ways in which socialization from fathers and father figures may function to protect young men from the effects of discrimination. This is an understudied area that warrants attention in the future. Although this study was novel in its focus on rural youth, the results cannot be assumed to generalize to youth in other environments. Replication with urban and suburban samples may detect effects of poverty on youth sexual behavior. Finally, studies in which both attitudes and behaviors are self-reported are subject to reporter bias that can inflate associations. The use of multiple measures operationalized as latent variables can ameliorate to some extent concerns regarding measurement bias. These caveats notwithstanding, the present research provides evidence of a theoretically derived pathway linking racial discrimination to multiple sexual partnerships among a distinct sample of African American male youth. These findings provide valuable insights for intervention development and policy aimed at deterring sexually transmitted infections and enhancing relationship development among young men.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number R01 DA029488 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Steven M. Kogan, University of Georgia

Tianyi Yu, University of Georgia.

Kimberly A. Allen, Florida State University

Alexandra M. Pocock, Teach for America, Atlanta, Georgia

Gene H. Brody, University of Georgia

References

- Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: Sexual networks and social context. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2006;33:S39–S45. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000228298.07826.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Sex codes and family life among poor inner-city youths. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1989;501:59–78. doi: 10.1177/0002716289501001004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Streetwise: Race, class, and change in an urban community. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Boatright SR. The Georgia County Guide. 28. Athens, GA: Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bosson JK, Vandello JA. Precarious manhood and its links to action and aggression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2011;20:82–86. doi: 10.1177/0963721411402669. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosson JK, Vandello JA, Burnaford RM, Weaver JR, Wasti SA. Precarious manhood and displays of physical aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2009;35:623–634. doi: 10.1177/0146167208331161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L. Love, sex, and masculinity in sociocultural context: HIV concerns and condom use among African American men in heterosexual relationships. Men and Masculinities. 2004;7:166–186. doi: 10.1177/1097184X03257523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman PJ. A discouragement-centered approach to studying unemployment among Black youth: Hopelessness, attributions, and psychological distress. International Journal of Mental Health. 1984;13(1–2):68–91. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Black families in therapy: Understanding the African American experience. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y-f, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Dorsey S, Forehand R, Armistead L. Unique and protective contributions of parenting and classroom processes to the adjustment of African American children living in single-parent families. Child Development. 2002;73:274–286. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Conger R, Gibbons FX, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Simons RL. The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children’s affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development. 2001;72:1231–1246. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kim S, Murry VM, Brown AC. Protective longitudinal paths linking child competence to behavioral problems among African American siblings. Child Development. 2004;75:455–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kim S, Murry VM, Brown AC. Longitudinal links among parenting, self-presentations to peers, and the development of externalizing and internalizing symptoms in African American siblings. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:185–205. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kogan SM, Chen Y-f. Perceived discrimination and increases in adolescent substance use: Gender differences and mediational pathways. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:1006–1011. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kogan SM, Grange CM. Translating longitudinal, developmental research with rural African American families into prevention programs for rural African American youth. In: Maholmes V, King RB, editors. Oxford handbook of poverty and child development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press-USA; 2012. pp. 551–565. [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, Brady N, Thompson S, Tobin JN, Cassells A, Sweeney M, Contrada RJ. Perceived racism and negative affect: Analyses of trait and state measures of affect in a community sample. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2008;27:150–173. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2008.27.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN, Williams DR, Jackson JS, Neighbors HW, Torres M, Sellers SL, Brown KT. “Being Black and feeling blue”: The mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race and Society. 2000;2:117–131. doi: 10.1016/S1090-9524(00)00010-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JC, Mezzacappa E, Beardslee WR. Self-regulation and its relations to adaptive functioning in low income youths. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:19–30. doi: 10.1037/a0014796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter RT, Forsyth J. Reactions to racial discrimination: Emotional stress and help-seeking behaviors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2:183–191. doi: 10.1037/a0020102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E, Miller GE. “Shift-and-persist” strategies: Why low socioeconomic status isn’t always bad for health. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7:135–158. doi: 10.1177/1745691612436694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi N. Sex role group differences in specific, academic, and general self-efficacy. Journal of Psychology. 2004;138:149–159. doi: 10.3200/jrlp.138.2.149-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu JY, Porche MV, Tolman DL. The adolescent masculinity ideology in relationships scale: Development and validation of a new measure for boys. Men and Masculinities. 2005;8:93–115. doi: 10.1177/1097184x03257453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Familias Unidas: A family-centered ecodevelopmental intervention to reduce risk for problem behavior among Hispanic adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5:113–132. doi: 10.1023/A:1015420503275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Wechsler H. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries. 2012 Jun 8;61(SS–4):1–162. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss6104.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Ageton SS, Huizinga D. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills, CA: Siegel; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR, Eckberg DL. Discrimination: Motivation, action, effects, and context. Annual Review of Sociology. 1980;6:1–20. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.06.080180.000245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CB, Wallace SA, Fenton RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:679–695. doi: 10.1023/A:1026455906512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Etcheverry PE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, Kiviniemi M, O’Hara RE. Exploring the link between racial discrimination and substance use: What mediates? What buffers? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99:785–801. doi: 10.1037/a0019880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, O’Hara RE, Stock ML, Gerrard M, Weng CY, Wills TA. The erosive effects of racism: reduced self-control mediates the relation between perceived racial discrimination and substance use in African American adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102:1089–1104. doi: 10.1037/a0027404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons FX, Yeh HC, Gerrard M, Cleveland MJ, Cutrona C, Simons RL, Brody GH. Early experience with racial discrimination and conduct disorder as predictors of subsequent drug use: A critical period hypothesis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:S27–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC, Longmore MA, Manning WD, Northcutt MJ. Adolescent identities and sexual behavior: An examination of Anderson’s player hypothesis. Social Forces. 2009;87:1813–1843. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff PA, Di Leone BAL, Kahn KB. Racism leads to pushups: How racial discrimination threatens subordinate men’s masculinity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2012;48:1111–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP. Taking it like a man: Masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination-depressive symptoms association among African American men. Amerian Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:S232–S241. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP, Mattis JS. Being a man about it: Manhood meaning among African American men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2005;6:114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Britt A, Valrie CR, Kurtz-Costes B, Rowley SJ. Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in African American youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:669–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Sherrill MR. Future orientation in the self-system: Possible selves, self-regulation, and behavior. Journal of Personality. 2006;74:1673–1696. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31:15–34. doi: 10.1023/A:1023066418688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joe GW, Broome KM, Rowan-Szal GA, Simpson DD. Measuring patient attributes and engagement in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2002;22:183–196. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IJ, Ge X, Brody GH, Conger RD, Gibbons FX, Simons RL. Parenting behaviors and the occurrence and co-occurrence of depressive symptoms and conduct problems among African American children. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:571–583. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Berkel C, Chen Y-f, Brody GH, Murry VM. Metro status and African-American adolescents’ risk for substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:454–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Brody GH, Chen Y-f, Grange CM, Slater LM, DiClemente RJ. Risk and protective factors for unprotected intercourse among rural African American young adults. Public Health Reports. 2010;125:709–717. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500513. Retrieved from http://www.publichealthreports.org/issueopen.cfm?articleID=2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Brody GH, Gibbons FX, Chen Y-f, Grange C, Simons R, Cutrona C. Mechanisms of family impact on African American adolescents’ HIV-related behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21:361–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Brody GH, Molgaard VK, Grange C, Oliver DAH, Anderson TN, Sperr MC. The Strong African American Families–Teen trial: Rationale, design, engagement processes, and family-specific effects. Prevention Science. 2012;13:206–217. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0257-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Cho J, Allen K, Lei MK, Beach SRH, Gibbons FX, Brody GH. Avoiding adolescent pregnancy: A longitudinal analysis of African American youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;53:14–20. doi: 10.1016/jadohealth.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Yu T, Brody GH, Chen YF, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Corso PS. Integrating condom skills into family-centered prevention: Efficacy of the Strong African American Families–Teen program. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SF, Herman KC, Bynum MS, Ialongo NS. Perceptions of racism and depressive symptoms in African American adolescents: The role of perceived academic and social control. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:519–531. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9393-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Youm Y. Racial/ethnic group differences in the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States: A network explanation. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 1999;26:250–261. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199905000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, Watkins DC, Chatters LM. Correlates of psychological distress and major depressive disorder among African American men. Research on Social Work Practice. 2011;21:278–288. doi: 10.1177/1049731510386122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long BC. Sex-role orientation, coping strategies, and self-efficacy of women in traditional and nontraditional occupations. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1989;13:307–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1989.tb01004.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SF, Seligman ME. Learned helplessness: Theory and evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1976;105(1):3–46. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.105.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW. Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Hill NE, Dodge KA. African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity. In: Dodge KA, Putallaz M, editors. Duke Series in Child Development and Public Policy. Vol. 3. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Milhausen RR, Crosby R, Yarber WL, DiClemente RL, Wingood GM, Ding K. Rural and nonrural African American high school students and STD/HIV sexual-risk behaviors. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27:373–379. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.27.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RB, Brickman SJ. A model of future-oriented motivation and self-regulation. Educational Psychology Review. 2004;16:9–33. doi: 10.1023/B:EDPR.0000012343.96370.39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brody GH. Partnering with community stakeholders: Engaging rural African American families in basic research and the Strong African American Families preventive intervention program. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2004;30:271–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2004.tb01240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murry VM, Brody GH. Self-regulation and self-worth of Black children reared in economically stressed, rural, single mother-headed families: The contribution of risk and protective factors. Journal of Family Issues. 1999;20:456–482. doi: 10.1177/019251399020004003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus version 7: User’s guide (Version 5) Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Noar SM, Morokoff PJ. The relationship between masculinity ideology, condom attitudes, and condom use stage of change: A structural equation modeling approach. International Journal of Men’s Health. 2002;1:43–58. doi: 10.3149/jmh.0101.43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara RE, Gibbons FX, Weng CY, Gerrard M, Simons RL. Perceived racial discrimination as a barrier to college enrollment for African Americans. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2012;38:77–89. doi: 10.1177/0146167211420732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell W, Mattis JS. Being a man about it: Constructions of masculinity among African American men. Psychology of Men and Masculinities. 2005;6:114–126. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz RJ, Foster S, Kent RN, O’Leary KD. Multivariate assessment of conflict in distressed and nondistressed mother-adolescent dyads. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1979;12:691–700. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1979.12-691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES–D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts ME, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Weng CY, Murry VM, Simons LG, Lorenz FO. From racial discrimination to risky sex: Prospective relations involving peers and parents. Developmental Psychology. 2011;48:89–102. doi: 10.1037/a0025430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins CJ. Sex role perceptions and social anxiety in opposite-sex and same-sex situations. Sex Roles. 1986;14:383–395. doi: 10.1007/bf00288423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders-Phillips K, Settles-Reaves B, Walker D, Brownlow J. Social inequality and racial discrimination: Risk factors for health disparities in children of color. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 3):S176–S186. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1100E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid KL, Phelps E, Kiely MK, Napolitano CM, Boyd MJ, Lerner RM. The role of adolescents’ hopeful futures in predicting positive and negative developmental trajectories: Findings from the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. Journal of Positive Psychology. 2011;6:45–56. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2010.536777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott WD, Dearing E, Reynolds WR, Lindsay JE, Baird GL, Hamill S. Cognitive self-regulation and depression: Examining academic self-efficacy and goal characteristics in youth of a Northern Plains Tribe. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2008;18:379–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00564.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Chen Y-f, Stewart EA, Brody GH. Incidents of discrimination and risk for delinquency: A longitudinal test of strain theory with an African American sample. Justice Quarterly. 2003;20:827–854. doi: 10.1080/07418820300095711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Murry V, McLoyd V, Lin KH, Cutrona C, Conger RD. Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: A multilevel analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:371–393. doi: 10.1017/S0954579402002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Sympson SC, Ybasco FC, Borders TF, Babyak MA, Higgins RL. Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:321–335. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Fegley S, Harpalani V, Seaton G. Understanding hypermasculinity in context: A theory-driven analysis of urban adolescent males’ coping responses. Research in Human Development. 2004;1:229–257. doi: 10.1207/s15427617rhd0104_2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens-Watkins D, Brown-Wright L, Tyler K. Brief report: The number of sexual partners and race-related stress in African American adolescents: Preliminary findings. Journal of Adolescence. 2011;34:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Dishion TJ, Light J, Yasui M. Implementing family-centered interventions within the public middle school: Linking service delivery to change in student problem behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:723–733. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-7650-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarkasa N. Interpreting the African heritage in Afro-American family organization. In: McAdoo HP, editor. Black families. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan S, Fisher L. Depression as a proxy of negative affect? A critical examination of the use of the CES–D in type 2 diabetes. European Review of Applied Psychology. 2010;60:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.erap.2009.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Psychosocial resources and the SES–health relationship. In: Adler NE, Marmot M, McEwen BS, Stewart J, editors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences: Vol. 896. Socioeconomic status and health in industrial nations: Social, psychological, and biological pathways. New York, NY: New York Academy of Sciences; 1999. pp. 210–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uomoto JM. Examination of psychological distress in ethnic minorities from a learned helplessness framework. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1986;17:448–453. [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Ponterotto JG, Reynolds AL, Cancelli AA. Racial discrimination, coping, life satisfaction, and self-esteem among African Americans. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2000;78:72–80. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.2000.tb02562.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandello JA, Bosson JK. Hard won and easily lost: A review and synthesis of theory and research on precarious manhood. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2013;14:101–113. doi: 10.1037/a0029826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandello JA, Bosson JK, Cohen D, Burnaford RM, Weaver JR. Precarious manhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:1325–1339. doi: 10.1037/a0012453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama T, Merten MJ, Wickrama KAS. Early socioeconomic disadvantage and young adult sexual health. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2012;36:834–848. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.36.6.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willer R, Rogalin CL, Conlon B, Wojnowicz MT. Overdoing gender: A test of the masculine overcompensation thesis. American Journal of Sociology. 2013;118:980–1022. doi: 10.1086/668417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, John DA, Oyserman D, Sonnega J, Mohammed SA, Jackson JS. Research on discrimination and health: An exploratory study of unresolved conceptual and measurement issues. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:975–978. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Williams-Morris R. Racism and mental health: The African American experience. Ethnicity & Health. 2000;5:243–268. doi: 10.1080/135578500200009356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Murry VM, Brody GH. Family communication and religiosity related to substance use and sexual behavior in early adolescence: A test for pathways through self-control and prototype perceptions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:312–323. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe WA. Overlooked role of African-American males’ hypermasculinity in the epidemic of unintended pregnancies and HIV/AIDS cases with young African-American women. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2003;95:846–852. Retrieved from http://proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu:80/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/214050116?accountid=14537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CA, Eccles JS, Sameroff A. The influence of ethnic discrimination and ethnic identification on African American adolescsents’ school and socioemotional adjustment. Journal of Personality. 2003;71:1197–1232. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.7106012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]