Abstract

Jasmonates, plant stress hormones, have been demonstrated to be effective in killing various types of cancer cells. We therefore tested if methyljasmonate (MJ) has activity against multiple myeloma (MM) in vitro and in vivo. MM cell lines and primary MM tumour cells responded to MJ in vitro at concentrations that did not significantly affect normal haematopoietic cells, without stroma-mediated resistance. Brief MJ exposures of MM cells caused release of Hexokinase 2 (HK2) from mitochondria, rapid ATP depletion, perturbation of major intracellular signalling pathways, and ensuing mainly apoptotic cell death. Sensitivity to MJ correlated with cellular glucose consumption and lactate production, as well as intracellular protein levels of HK2, phosphorylated Voltage-dependent anion channel 2/3 (pVDAC2/3) and Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C1 (AKR1C1), which represent potential biomarkers of responsiveness to MJ treatment, especially as AKR1C1 transcript levels also correlate with clinical outcome in bortezomib- or dexamethasone-treated MM patients. Interestingly, MJ synergized with bortezomib in vitro and prolonged survival of immunocompromised mice harbouring diffuse lesions of MM.1S cells compared to vehicle-treated mice (p=0.0046). These studies indicate that jasmonates represent a new, promising strategy to treat MM.

Keywords: Multiple Myeloma, Jasmonates, ATP Depletion, Metabolic Activity, Aldo-Keto Reductases

Introduction

Methyljasmonate (MJ), a small molecular weight organic molecule normally produced by plants in response to different stresses, has been demonstrated to be active in preclinical models from diverse types of neoplasias, including melanoma, prostate and breast cancer, as well as lymphoblastic leukaemia (Fingrut and Flescher 2002). The mechanism by which the compound induces killing of cancer cells has not finally been determined to date, or might vary between different cell types. Kim et al (2004) found that the molecule induces BCL2-associated X protein (BAX) as well as BCL2-like 1 (BCL2L1) and activates Caspase 3 (CASP3) via reactive oxygen species production in A549 cells. Goldin et al 2008) later similarly demonstrated that MJ acts at the mitochondria, but attribute the cell killing to detachment of mitochondria-bound Hexokinase. Other studies reported that MJ downregulates expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen in human neuroblastoma cell lines (Tong, et al 2008). In addition, Davies et al (2009) recently reported that MJ can also bind to members of the Aldo-keto reductase family 1, which are involved in steroid metabolism and repeatedly identified as potential biomarkers for various types of cancer cells (Hsu, et al 2001, Ji, et al 2003, Tai, et al 2007, Vihko, et al 2005).

Similarly, various forms of MJ-induced cell death have been reported. Most researchers found that MJ induces apoptosis in cancer cells (Fingrut and Flescher 2002, Kim, et al 2004, Tong, et al 2008, Yeruva, et al 2006). Others reported MJ-induced cell death with mixed characteristics of apoptosis and necrosis in cervical cancer cells (Kniazhanski, et al 2008), and, in contrast, nonapoptotic death has been demonstrated in B-lymphoma cells (Fingrut, et al 2005). Despite all these mechanistically different reports, jasmonates have repeatedly been documented to be active against preclinical models of haematological malignancies. Following the initial report (Fingrut & Flescher 2002), Ishii, et al (2004) demonstrated induction of differentiation of human myeloid leukaemia cells, and Fingrut et al (2005) found that jasmonates are even capable of killing high-resistance mutant tumour protein p53 (TP53) expressing B-lymphoma cells.

Despite the recent introduction of new agents, such as the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Velcade™, PS-341) or thalidomide and its immunomodulatory derivatives (IMiDs), multiple myeloma (MM) still remains an incurable haematological disease. Given its preclinical activity in other haematological malignancies, we evaluated the effect of MJ on MM cells. The compound displayed in vitro and in vivo anti-MM activity, which was associated with release of Hexokinase 2 (HK2) from mitochondria, rapid intracellular ATP depletion, and major perturbation of several major signalling pathways, ultimately leading to apoptosis. Furthermore, MJ exhibited synergistic effects with bortezomib. In an attempt to identify potential biomarkers for MJ treatment, we identified a correlation of sensitivity to MJ with cellular glucose consumption and lactate production, as well as intracellular protein levels of HK2, phosphorylated Voltage-dependent anion channel 2/3 (pVDAC2/3) and Aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C1 (AKR1C1). Interestingly, AKR1C1 transcript levels also correlated with clinical outcome in bortezomib- or dexamethosone-treated MM patients.

Materials & Methods

Tissue Culture (TC) and Cell Lines

Cell lines were provided by: a) MM.1S: Dr. S. Rosen (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL), b) RPMI-8226/S, RPMI-8226/Dox40 & RPMI-8226/LR5: Dr. W. Dalton (Lee Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL), c) OCI-My5: Dr. Meissner (University of Ontario, Toronto, Canada), d) OPM1: T. Hideshima (DFCI, Boston, MA), e) INA-6: Dr R. Burger (University of Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany), f) NCI-H929, U266 & HS-5: American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), g) KMS1, KMS11, KMS18 (Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (JCRB) cell line bank, Japan), h) MOLP-8, OPM2: DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany), i) ANBL-6: Robert Z. Orlowski (The University of Texas, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX), and, j) UTMC-2: Dr R. Carrasco (Dana Farber Cancer Institute [DFCI], Boston, MA). MM.1S-GL & OPM2-GL were generated by stable transduction of the parental MM cell lines with a retroviral vector encoding a GFP-Luciferase fusion protein.

All MM cell lines, except for INA-6 and ANBL-6, were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Cellgro®, Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS; Biowhittaker®, Lonza, Walkersville, MD), 10 iu/ml penicillin and 10 mg/ml streptomycin (Cellgro®). INA-6 and ANBL-6 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20 % FBS, 10 iu/ml penicillin, 10 mg/ml streptomycin and 5 ng/ml recombinant human interleukin 6 (IL6) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). HS-5 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (Cellgro®) supplemented with 10 % FBS (Biowhittaker®), 10 iu/ml penicillin and 10 mg/ml streptomycin (Cellgro®). All cells were kept in humidified incubators at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC) and Primary Patient Samples

Peripheral blood samples were collected from healthy volunteers using sodium heparin-coated BD Vacutainers® (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated by Ficoll-Paque™Plus (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) gradient centrifugation. For T cell activation, PBMC were stimulated 16 h before drug exposure with 5 μg/ml phytohaemagglutinin (PHA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Bone marrow samples from MM patients, who had provided informed consent according to DFCI Institutional Review Board approved protocols, were harvested using heparin-coated blood collection tubes. PBMC were isolated by Ficoll gradient centrifugation and MM cells were purified by immunomagnetic cell separation using microbead conjugated anti-hCD138 antibodies (MACS®, Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA).

Colourimetric Survival Assays for Single-Agent and Combination treatments

The impact of methyljasmonate (Sigma-Aldrich) on cell viability in vitro was determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Millipore, Billerica, MA) colourimetic survival assays. Briefly, 5,000 – 10,000 cells were plated in 200 μl of appropriate medium in 96-well plates and cultured under standard tissue culture conditions overnight to allow cells to accommodate. The next day drugs were added at the indicated concentrations and plates were incubated in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5 % CO2 for the indicated times. For analysis, 20 μl of MTT reagent were added. After 4 h of incubation, formazan precipitates were collected by centrifugation (5 min, 1600 rpm) and dissolved in 200 μl dimethyl sulphoxide. Colourimetric signals were measured at 540 nm wavelength using a “Spectra-max PLUS” absorbance reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) with a background read at 690 nm.

Z-IETD-fmk (MBL, Woburn, MA), Z-LEHD-fmk (Imgenex, San Diego, CA), Ac-DEVD-CHO, and Z-VAD (both Promega, Madison, WI) were added to cells in the indicated concentrations 1 h prior to MJ exposure.

Bortezomib (Millennium, Cambridge, MA), lenalidomide (Celgene, Summit, NJ), 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG), doxorubicin, dexamethasone and rapamycin (all Sigma-Aldrich) were applied at the concentrations indicated for 24 h, either alone or in combination with a MJ concentration, killing about 50% of MM cell line cells.

Stromal Cell Co-Culture / Compartment-specific bioluminescence imaging (CS-BLI Assay)

CS-BLI assays were conducted as described (McMillin, et al, 2010). Briefly, luc-negative HS-5 human stromal cells were plated in 96-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. GFP-luciferase fusion protein-expressing MM cells were then added and treated with the drug for 24 h at the indicated doses. After adding luciferin substrate (Xenogen Corp., San Francisco, CA) to the cultures MM cell survival was analysed using a Luminoskan luminometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Cell Death Commitment Assay

MM cells were exposed to MJ for the times indicated. The compound was then removed by washing the cells, which were maintained then for a total of 24 h under standard tissue culture conditions in the absence of drug. Results were measured by MTT assays, as described above.

Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) - Flow Cytometry and Flow Cytometry-based Cell Cycle Analysis

Annexin V/PI

∼5 × 105 cells were incubated with the drug as indicated, collected by centrifugation (700 × g at room temperature for 5 min), and resuspended in 100 μl binding buffer (Annexin V-FLUOS staining kit, Roche Diagnostics, Penzberg, Germany). 5 μl Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and PI (1 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) were added and the cells were incubated at room temperature for 15 min in the dark. Fluorescence was recorded using a Cytomics Canto (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) flow cytometer. Final data analysis was conducted using WinMDI version 2.8 software (J.Trotter, Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA).

Cell Cycle Analysis

Cells were treated and collected as described above. They were resuspended in 300 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.05 % Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.3 μg/ml RNAse and incubated at 37 °C for 20 min. 20 μl of PI reagent were added and flow cytometry analyses were performed immediately, as described for the Annexin V/PI combination experiment.

Immunoblots

The indicated antibodies were purchased from a) Abcam® (Cambridge, MA): VDAC1 [Cat. No. 14734], pVDAC2/3 [47104], AKR1C1 [72576]; AKR1C2 [54807]; AKR1C3 [84327], b) Cell Signaling Technology® (Danvers, MA): v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 (AKT1) [9272], phosphorylated AKT1 [4051], Caspase 8 (CASP8) [9746], Caspase 9 (CASP9) [9508], HK2 [2867], phosphorylated Jun proto-oncogene (pJUN) [9164S], Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 (MAP2K1/2) [9122], phosphorylated MAP2K1/2 [9121], Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor (CDKN1A) [2947], Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) [9542], Retinoblastomal 1 (RB1) [9309], Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) [9176], Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) [9139], d) Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA): Actin, beta (ACTB) [sc 8432], ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) [sc30538], Glyceralaldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) [sc47724], Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1 (NFKB1) [sc372-G], phosphorylated CDKN1A [sc20220 R], and e) Upstate / Millipore: phosphorylated Insulin receptor substrate 1 (pIRS1) [07-247], Jun proto-oncogene (JUN) [06-225], TP53 [05-224].

Cells were exposed to drugs as indicated, washed, and harvested by centrifugation (1200 rpm, 5 min). Cell pellets were lysed with Western blot lysis buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0; 120 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% Igepal, Complete Proteinase Inhibitors Cocktail (Roche Diagnostics), Phosphatase Inhibitors Cocktail Set II (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA)). Protein concentrations of lysates were determined with Bradford reagent (Sigma-Aldrich). 20 μg of total protein extract per sample were separated by 4% stacking and 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Nupage, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for ∼2 h at 120V, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon P, Millipore) for 1.25 h at 0.4 Amp. All membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5% skimmed milk powder in Tris-buffered saline and Tween 20 (TBST) and washed with TBST for 20 min. Immunodetections were carried overnight at 4 °C using the antibodies in concentrations as recommended by the manufacturers. Immunocomplexes were visualized using SuperSignal West Pico Luminol Enhancer Solution (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and locations of signals were preserved on BioMax XAR films (Kodak, New Haven, CT) and HyBlot CL™ Autoradiography films (Denville Scientific, Metuchen, NJ).

Isolation of Mitochondria from TC Cells

Cells were homogenized in a 10 mM Tris/HCl buffer, pH 7.8, containing 0.32 M sucrose and 1 mM EDTA using a Dounce glass homogenizer (Wheaton, Millville, NJ). After separation of nuclei, mitochondria were collected by centrifugation at 13 000g, 4 °C for 20 min. The mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in a trehalose buffer (Yamaguchi, et al 2007) to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. 30 μl of isolated mitochondria were incubated with drugs as indicated and HXK II protein levels in suspension supernatant were analysed by immunoblot.

CellTiter-Glo® Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (CTG; Promega)

5,000 cells in 200 μl growth medium per well were exposed to MJ as indicated in optical 96-well plates (Corning, Lowell, MA). ATP depletion was measured by CTG assay according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, CellTiter-Glo® buffer and CellTiter-Glo® substrate were mixed to form CellTiter-Glo® reagent. 20 μl of reagent were added to the cells, mixed for 2 min on an orbital shaker, incubated for 10 min at room temperature, and the luminescence signal was recorded using a Luminoskan luminometer.

In Vivo Experiments

30 non-obese diabetic severe combined immunodeficient (nod/scid) mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were irradiated with 150 rads and injected in the tail vein with 0.5 × 106 MM1.S cells in 100 μl PBS the following day. After 25 days mice were randomly divided into two groups of equal size. One group received 100 μl of 1000 mg/kg MJ in vegetable oil per intraperitoneal (IP) injection 5 days a week over the next 8 weeks, the other group an equal volume of vehicle only. Animals were monitored for weight, tumour growth, as well as overall survival for 179 days after MM cell injection. In compliance with animal research guidelines, mice were sacrificed when displaying hind limb paralysis or excessive visible tumour growth.

MitoTracker® Green (MTG) Based Determination of Cellular Mitochondria Content

MTG reagent was purchased from Invitrogen (Eugene, OR) and MM cells were stained and analysed following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 5 × 105 cells of each cell line were stained with 100 nM MTG reagent in 1 ml of normal growth medium for 20 min at 37 °C. Then the mitochondrial content of the cells was determined by flow cytometry; the cell line with the highest content was set to 100 % and all others as a relative proportion.

Determination of Glucose Consumption and Lactate Production, respectively, in MM Cell Line Cells

EnzyChrom™ Glucose Assay Kit and L-Lactate Assay Kit were purchased from BioAssay Systems (Hayward, CA), and MM cells were analysed following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, for each analysis 1 × 105 cells were starved in 500 μl of glucose-free RPMI medium supplemented with 10 % FBS for 1 h. Then exogenous glucose was added to a final concentration of 200 mg/l, and samples were incubated at 37 °C. After the times indicated, samples were harvested and supernatants obtained by centrifugation (1600 rpm, 5 min). 20 μl of each sample were mixed with 80 μl of the appropriate working reagent. For glucose determination, samples were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, optical densities measured at 570 nm and glucose concentrations calculated using a previously established standard curve. For lactate production, optical densities at 565 nm were determined immediately (OD0) and after 20 min of incubation at room temperature (OD20). OD0 was subtracted from OD20, and lactate production calculated using a previously established standard curve. For both assays medium enzymatic activity for the experimental setting was calculated.

Transcriptional Signature of AKR1C Transcripts and Relationship with Clinical Outcome

We analysed the log2-transformed and median-centered gene expression dataset of tumour cells from bortezomib-treated MM patients enrolled in the Assessment of Proteasome Inhibition for Extending Remissions (APEX) clinical trial of relapsed/refractory MM (Mulligan, et al 2007, Richardson, et al 2005). We specifically evaluated the patterns of expression of probes for AKR1C isoforms and patients were classified as having high (>30th percentile) vs. low (<30th percentile) expression of these probes. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses comparing the resulting groups were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA).

Results

Effect of MJ on MM cells in vitro

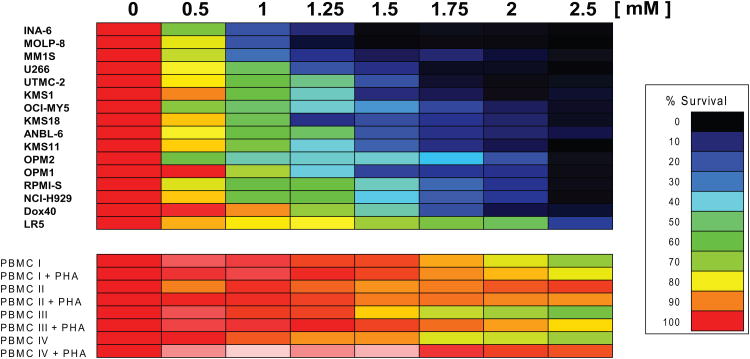

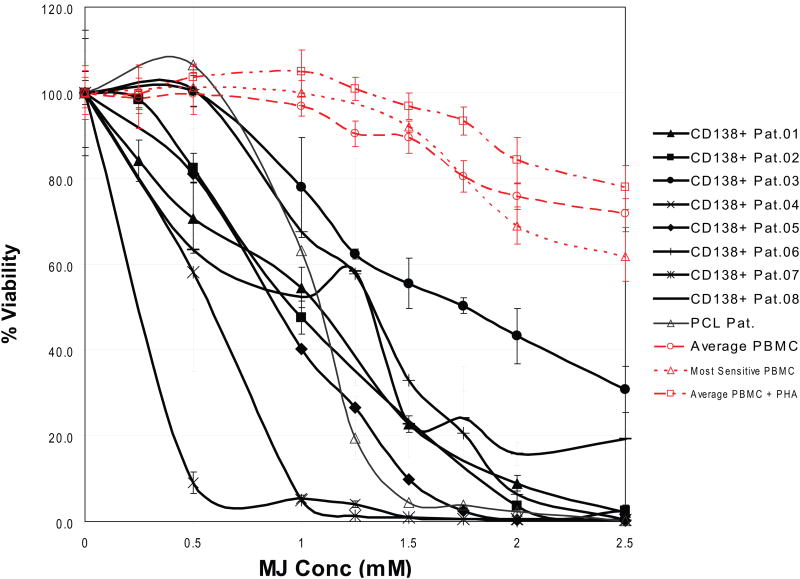

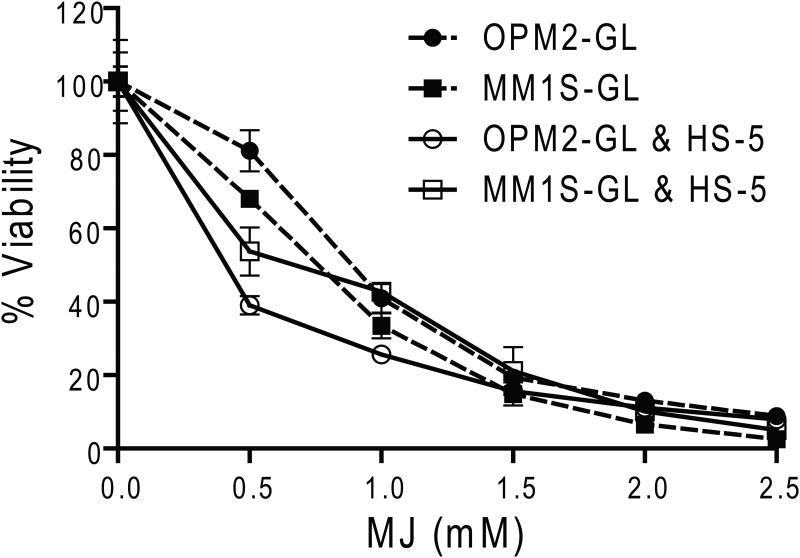

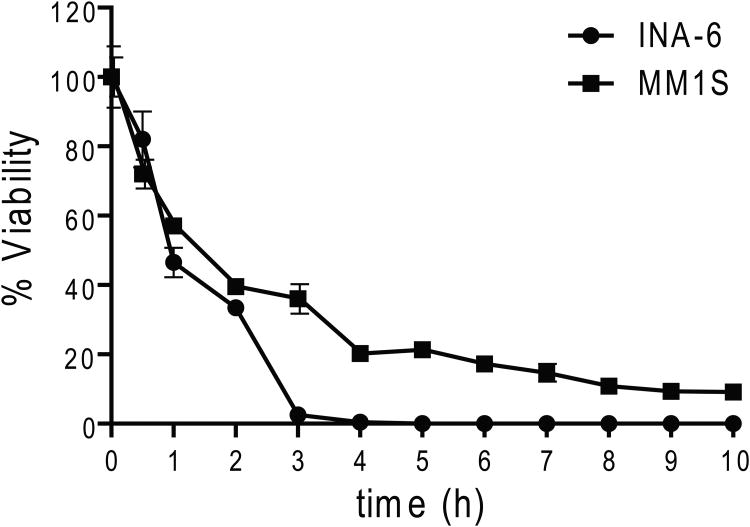

MTT assays were employed to examine how treatment with MJ affected the viability of different MM cell lines. In concordance with previously reported results (Fingrut & Flescher 2002), we used doses of 0.5 - 2.5 mM for 24 h in these experiments. We observed 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of ≤ 1.5 mM for 15/16 (94 %) cell lines tested and >90% reduction in viability of all MM cell lines at the highest tested concentration (Fig. 1A). In contrast, PBMC of healthy donors, with or without PHA stimulation, were not affected by 1.5 mM MJ and displayed >65% viability at even 2.5 mM. In the presence of exogenous IL6, INA-6 cells were very sensitive to MJ, indicating that IL6 does not confer protection against MJ-mediated MM cell death. We next tested the in vitro response of purified CD138+ tumour cells from 8 MM patients. All samples were sensitive to MJ, with IC50 values at or below 1.5 mM, similar to the previously tested MM cell lines (Fig. 1B). Accordingly, the sensitivity of all primary MM samples was also significantly higher than the average of the response of the PHA-stimulated PBMCs reported in Fig 1A. Additionally, primary cells from a patient with Plasma Cell Leukaemia (PCL), a MM-related plasma cell neoplasia, were exposed to MJ. These cells also reacted comparably to the primary MM samples. Given that bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) protect MM cells against anti-MM therapeutics, such as glucocorticoids, alkylating agents or anthracyclines (Damiano, et al 1999, Nefedova, et al 2003), we examined if the effects of MJ were impaired by MM cell – stromal cell interactions. Using the CS-BLI assay, we did not detect any decrease in the sensitivity of the MM cell lines, OPM2 and MM.1S to MJ in the presence or absence of HS-5 BMSCs. Interestingly, at low MJ concentrations, interaction with stroma was even associated with a statistically significant increase in sensitivity of MM cells to MJ. Therefore, interaction with stromal cells confered no protection for MM cells to MJ (Fig. 1C). HS-5 cells, when tested alone, were not killed by MJ concentrations up to 2.5 mM (data not shown), indicating a selective anti-MM effect of MJ. To evaluate the minimal duration of drug exposure necessary to induce cell death, we performed cell death commitment assays and found that 1-h of exposure to 1.5 mM MJ was sufficient to induce cell death in ∼50% of INA-6 and MM.1S cells (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1A. Effect of Methyljasmonate (MJ) on Multiple Myeloma (MM) Cell Lines & peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).

MM cell lines as well as PBMCs (with or without phytohaemagglutinin [PHA] stimulation) were exposed to different concentrations of MJ for 24 h, and cell viability was determined by MTT (3-(4,5- dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay.

Figure 1B. Effect of MJ on CD138+ Cells from MM Patients.

CD138+ cells were purified from primary samples of patients with MM or plasma cell leukaemia (PCL) and exposed to the indicated MJ concentrations. After 24 h, cell viability was assayed by MTT. For comparison, the average viability of untreated and PHA-stimulated PBMCs as well as the most sensitive PBMC out of 7 samples tested, are shown to illustrate the selective nature of anti-MM activity of MJ. Pat., patient.

Figure 1C. Effect of MJ on MM Cells in the Presence of Stroma.

GFP & Luciferase expressing OPM2 and MM.1S cells were tested for MJ sensitivity, either alone or in co-culture with HS-5 stroma cells. Cell viability was analysed after 24 h of drug exposure by compartment-specific bioluminescence imaging.

Figure 1D. MJ Cell Death Commitment Assay.

INA-6 and MM.1S cells were exposed to 1.5 mM MJ for the times indicated. Then the drug was washed out and cell viability was determined by MTT assay after a total culture of 24 h.

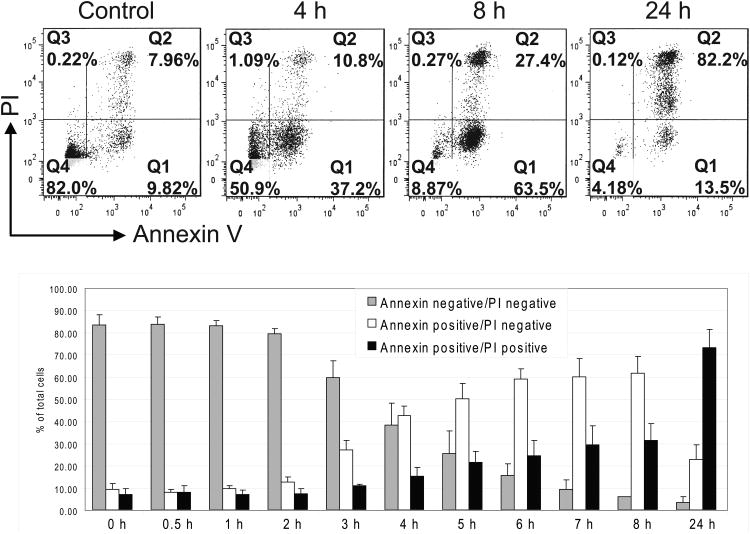

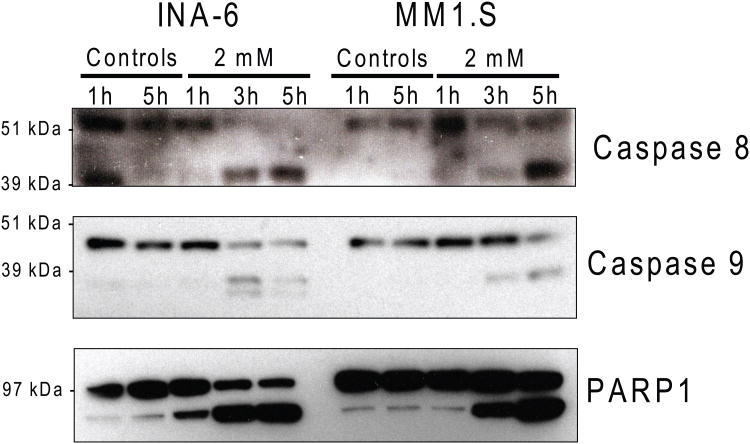

MJ induces apoptosis in MM cells

Next, we examined whether MJ induces apoptosis of MM cells by Annexin-V/PI based flow cytometry analysis. We observed a significant increase of Annexin-V+/PI- cells during the early hours of exposure to 1.5 mM MJ, followed by a shift to an Annexin-V+/PI+ population (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that MJ induces apoptosis early, followed by secondary necrosis of tumour cells. Immunoblot analyses showed that CASP8, CASP9 as well as PARP1 are cleaved in MM.1S and INA-6 cells after 3 or more hours of MJ exposure (Fig. 2B). Pretreatment with inhibitors against individual caspases and pan-caspase inhibitors did not protect INA-6 cells against MJ completely, indicating that caspase-independent events participate in MJ-mediated killing of MM cells (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2A. Flow Cytometry Analysis of Methyljasmonate (MJ)-Induced Cell Death.

INA-6 cells were exposed to MJ for the times indicated, and cell death was analysed by Annexin V/propidium iodide (PI)-based flow cytometry. The bar graphs summarize results of 4 independent experiments.

Figure 2B. MJ Exposure Triggers Apoptotic Cascades.

INA-6 and MM.1S cells were exposed to 2 mM MJ for 1, 3 and 5 h. Caspase 8 and 9, as well as PARP1 cleavage was measured by Immunoblot.

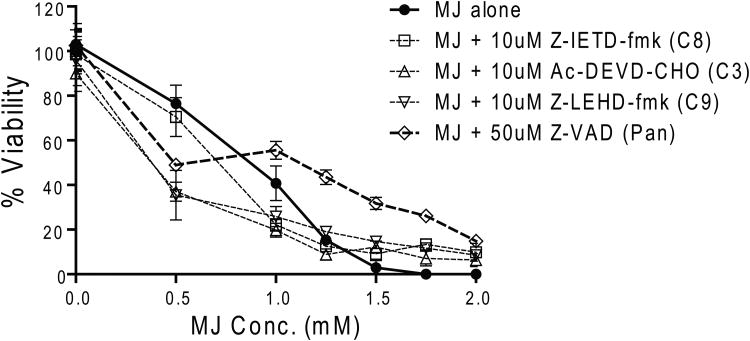

Figure 2C. Caspase Inhibitors Do Not Protect Against MJ-Induced Cell Death.

INA-6 cells were pretreated with the specific caspase 3 inhibitor, Ac-DEVD-CHO, the caspase 8 inhibitor, Z-IETD-fmk, the caspase 9 inhibitor, Z-LEHD-fmk, or the pan-caspase inhibitor, Z-VAD, at the concentrations indicated, and then exposed to different concentrations of MJ. After 24 h, cell viability was assayed by MTT.

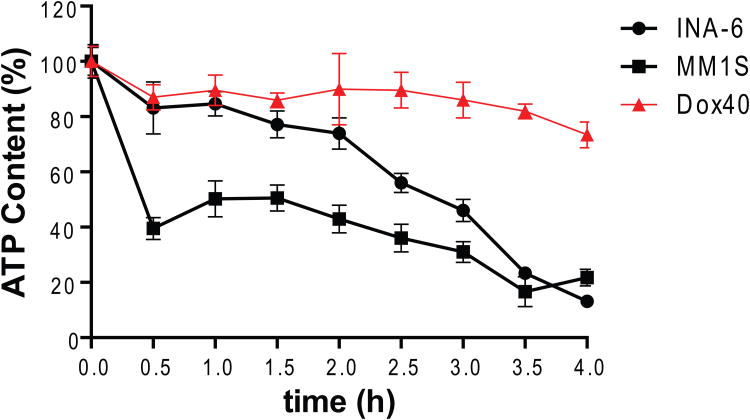

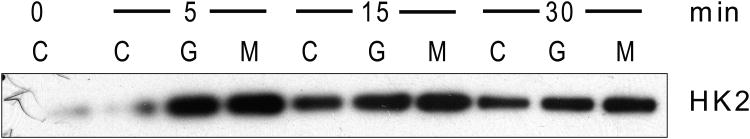

MJ exposure causes a rapid release of HK2 from mitochondria of MM cells and loss of intracellular ATP

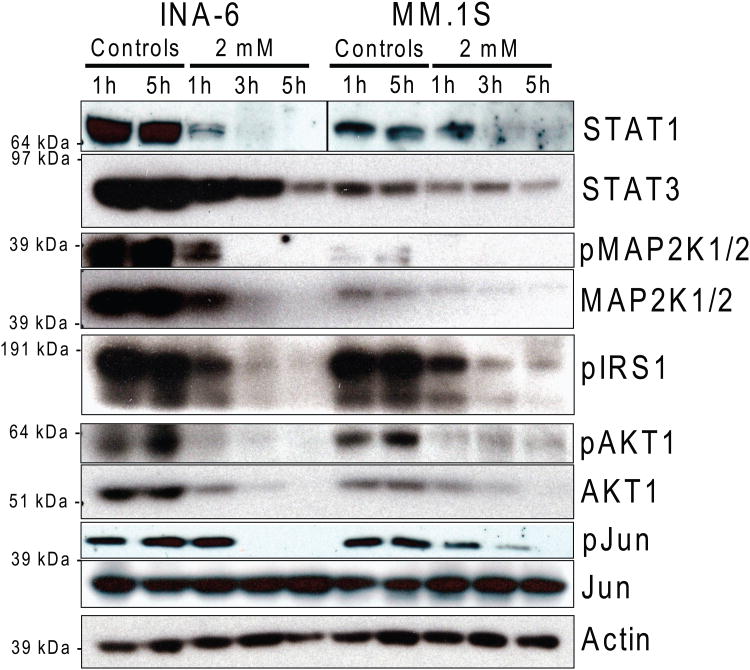

MJ causes a rapid detachment of HK2 from mitochondria in MM cells (Fig 3A), consistent with previously reported data (Goldin, et al 2008) for CT-26 colon carcinoma cells. Using CTG assays, we observed ATP depletion in MJ-sensitive MM.1S and INA-6 cells within 4 h of drug exposure, while the ATP loss was less pronounced in the less sensitive RPMI-8226/Dox40 MM cells (Fig. 3B). Given that loss of ATP should impair intracellular phosphorylation events, we next evaluated how MJ impacted important intracellular signalling pathways. After short exposure to MJ, INA-6 as well as MM.1S cells exhibited decreased phosphorylation of MAP2K1/2, IRS1, AKT1 and JUN. Decreased levels of total STAT1, STAT3, MAP2K1/2 and AKT1 protein were observed with slightly slower kinetics (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3A. Release of HK2 from Mitochondria after Methyljasmonate (MJ) Exposure.

Mitochondria freshly isolated from MM1.S cells were incubated with 1.5 mM MJ (M), phosphate-buffered saline (C), or 0.5 mM Glucose-6-phosphate (G) at 37°C for the times indicated. HK2 protein was detected in the supernatant by Immunoblot.

Figure 3B. ATP Depletion by MJ Exposure.

INA-6 as well as MM.1S cells were exposed to 1.5 mM MJ and intracellular ATP content was determined by CellTiter-Glo® assay after the times indicated.

Figure 3C. Impact of MJ on Key Molecules of Signalling Pathways.

INA-6 and MM.1S cells were exposed to 2 mM MJ for 1, 3 and 5 h. Changes in phosphorylation status and total protein levels were analysed by Immunoblot.

MJ exposure does not cause a distinct pattern of cell cycle block in MM

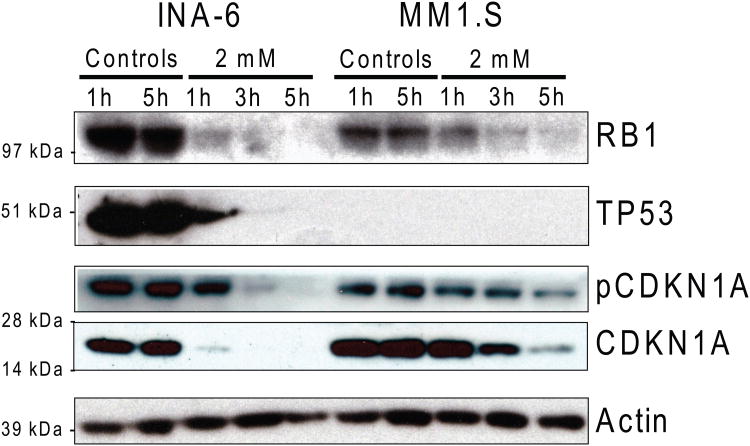

We next analysed the effect of MJ on cell cycle in MM cells by PI-based flow cytometry analysis (Table I). No arrest of MM cells was detected in a specific phase of the cell cycle. However, already after 3 h of MJ exposure MM cells accumulated in the sub G1 region indicating nuclear DNA degradation. Interestingly, induction of cell death was preceded by suppression of intracellular levels of RB1, TP53, and CDKN1A (Fig. 4) suggesting that MJ triggers commitment to cell death despite decreased levels of proteins with known anti-proliferative or pro-apoptotic role.

Table I. Cell Cycle Analysis of multiple myeloma cells exposed to methyljasmonate.

INA-6 and MM.1S cells were exposed to 1.5 mM methyljasmonate for the times indicated. Changes in cell cycle were examined by propidium iodide-based flow cytometric analysis.

| INA-6 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| time (h) | sub G1 (%) | in cell cycle (%) | G0/G1 (%) | S (%) | G2/M (%) |

| 0 | 7.2 | 58.5 | 15.3 | 29.8 | 13.4 |

| 1 | 6.9 | 58.3 | 16.1 | 29.6 | 12.6 |

| 3 | 12.2 | 35.4 | 12.7 | 22.7 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 31.7 | 29.5 | 8.3 | 18.8 | 2.4 |

| 7 | 39.5 | 29.7 | 10.4 | 19.3 | 0.0 |

| 24 | 46.9 | 10.9 | 0.4 | 5.1 | 5.4 |

| MM1.S | |||||

| time (h) | sub G1 (%) | in cell cycle (%) | G0/G1 (%) | S (%) | G2/M (%) |

| 0 | 9.9 | 70.0 | 32.6 | 32.7 | 4.8 |

| 1 | 8.0 | 73.6 | 36.5 | 32.4 | 4.7 |

| 3 | 9.0 | 70.9 | 38.2 | 28.7 | 3.9 |

| 5 | 13.3 | 62.4 | 35.7 | 23.1 | 3.7 |

| 7 | 12.0 | 65.3 | 39.2 | 22.0 | 4.1 |

| 24 | 65.8 | 17.6 | 14.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

Figure 4. Immunoblot Analysis of Key Proteins for Cell Cycle & Survival.

INA-6 and MM.1S cells were exposed to 2 mM methyljasmonate for 1, 3 and 5 h. Changes in phosphorylation status and total protein level were determined.

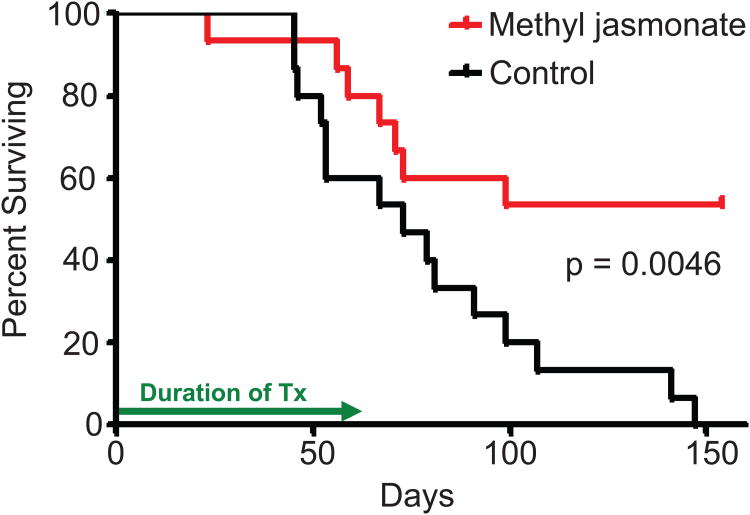

Effect of MJ on MM cells in vivo

We next evaluated the potential of MJ as a new anti-MM agent in vivo. We treated 15 nod/scid mice previously injected with MM.1S cells with 1000 mg/kg MJ for 8 weeks. Tumour growth was monitored by physical parameters (weight loss, visible tumour masses, hind limb paralysis), and overall survival was used as end point of the study. As illustrated in Fig. 5, after 150 days, 15/15 vehicle-treated control mice had died, while 8/15 MJ-treated mice were still alive. Statistical analysis proved a significant difference (p = 0.0046, log-rank test) for single agent administration of MJ in vivo.

Figure 5. In Vivo Activity of Methyljasmonate (MJ).

30 NOD/SCID mice were irradiated with 150 rads, and 5× 105 MM1.S cell were injected into the tail vein the next day. After 25 days, mice were split into 2 equal groups and treated by IP injections with either control vehicle alone or 1000 mg/kg MJ on a “5 days on/2 days off” schedule for the next 8 weeks. Overall survival is illustrated.

Correlation of MJ sensitivity and molecular markers

As not all MM cell lines responded equally to MJ, we attempted to identify cellular markers that correlate with in vitro MJ sensitivity and thus could serve as predictive biomarkers. We focused on previously described key mechanisms, cellular compartments and proteins affected by MJ.

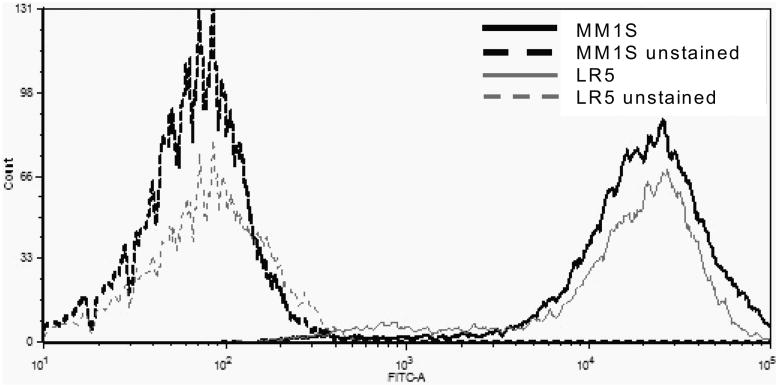

First, the relative number of mitochondria per cell were determined in 10 different MM cell lines using Mitotracker-Green based flow cytometry analysis. There was no correlation of MJ sensitivity (expressed in terms of IC50 values) with the relative numbers of mitochondria in each cell line (p = 0.7775, R2 = 0.01056) (Fig. 6A, Table II).

Figure 6A. Determination of Relative Number of Mitochondria.

Identical numbers of cells of 10 different MM cell lines were stained with Mitotracker Green reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol. Mean intensities of fluorescence were determined by flow cytometry. A representative overlay in histogram form of MM.1S and LR5 cells, which contain similar numbers of mitchondria but have a significantly different IC50, is shown.

Table II. Methyljasmonate Sensitivity & Relative Number of Mitochondria.

Results obtained as illustrated in Figure 5A were normalized to the cell line with the highest mitochondria content and compared to the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50).

| Cell line | IC50 (mM) | Number of Mitochondria/cell (% of highest cell line) |

|---|---|---|

| INA-6 | 0.70 | 74.5 |

| MM.1S | 0.70 | 68.3 |

| OPM2 | 0.80 | 62.8 |

| OCI-MY5 | 1.00 | 81.5 |

| KMS18 | 1.00 | 57.1 |

| ANBL-6 | 1.25 | 100.0 |

| KMS11 | 1.25 | 96.4 |

| OPM1 | 1.25 | 63.6 |

| RPMI-S | 1.35 | 85.2 |

| LR5 | 2.05 | 61.1 |

Next, we determined the glycolytic activity of 6 MM cell lines by measuring glucose consumption as well as lactate production over 24 h. We restricted this analysis to lines growing under identical conditions and therefore did not include INA-6 in this study. As can be seen in Table III, there was a statistically significant correlation of decreased MJ sensitivity with higher glucose consumption and lactate production (p = 0.0127, R2 = 0.8218 and p = 0.0155, R2 = 0.8037, respectively).

Table III.

Methyljasmonate Sensitivity & Glycolytic Activity. Identical numbers of cells of 6 different multiple myeloma cell lines were starved for 2 h in glucose-free medium. Glucose was then added, and its utilization as well as the production of lactate was analysed over time. Results were compared to the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50), as determined previously. Results of correlation coefficient analysis for IC50 vs glucose consumption and lactate production are outlined.

| Cell line | IC50 | Glucose Consumption (uM/h) | Lactate Production (mM/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MM.1S | 0.70 | 8.321 | 0.023 |

| OCI-MY5 | 1.00 | 19.308 | 0.076 |

| KMS18 | 1.00 | 36.734 | 0.035 |

| KMS11 | 1.25 | 78.442 | 0.125 |

| OPM1 | 1.25 | 84.968 | 0.155 |

| LR5 | 2.05 | 114.160 | 0.195 |

Correlation coefficient analysis for IC50 vs Glucose Consumption: R2 = 0.8218, p = 0.0127*

Correlation coefficient analysis for IC50 vs Lactate Production: R2 = 0.8037, p = 0.0155*

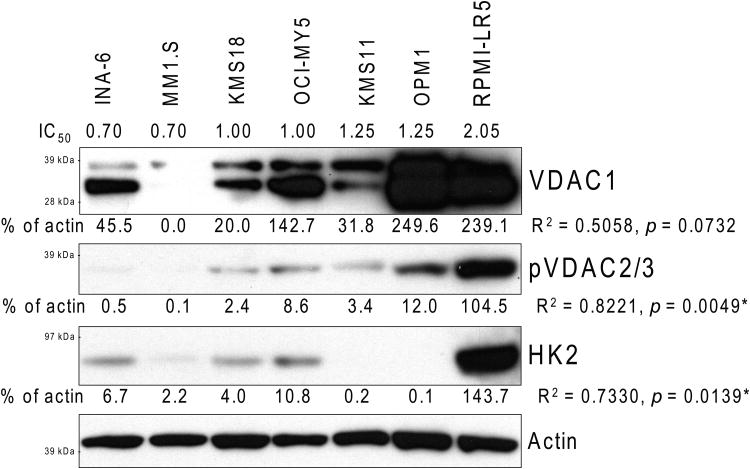

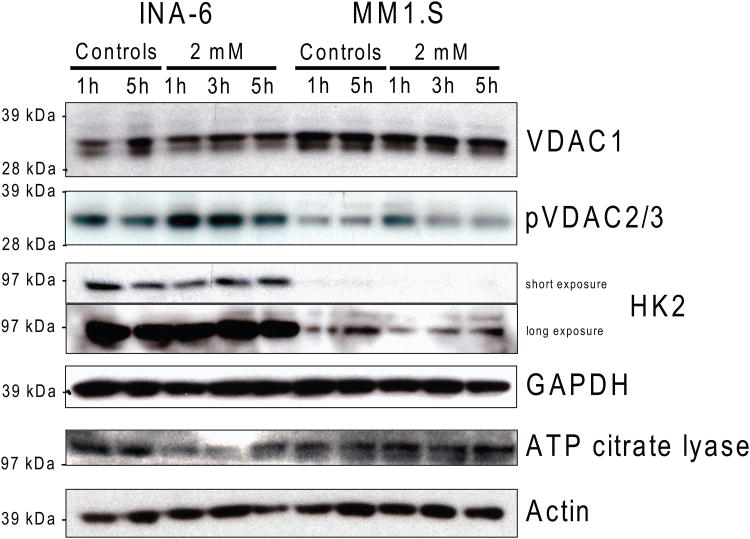

We also determined the baseline protein levels of VDACs and HK2 by immunoblot in 7 different MM lines. We observed a trend for correlation between decreased MJ sensitivity and higher VDAC1 protein levels (p = 0.0732, R2 = 0.5058), and a statistically significant correlation between MJ IC50 values and pVDAC2/3 (p = 0.0049, R2 = 0.8221) as well as HK2 (p = 0.0139, R2 = 0.7330) protein levels (Fig. 6B). We also investigated how levels of those enzymes changed over time in MJ-sensitive INA-6 and MM.1S cells after MJ exposure. While other proteins involved in energy production, namely VDAC1, GAPDH and ACLY were not or only minimally changed, pVDAC2/3 was up-regulated early. HK2 protein levels initially decreased, but then similarly increased again in those MM cell lines (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6B. Methyljasmonate (MJ) Sensitivity and VDACs & HK2 Protein Levels.

Total cell extracts of different untreated multiple myeloma cell lines were analysed by Immunoblot for VDAC1, pVDAC2/3 and HK2 levels. Bands on films were quantified with ImageJ software and normalized to the corresponding Actin control; relative intensities are indicated. The values were then analysed for correlation with the IC50 as determined in Fig. 1A. Correlation coefficients and p-values are outlined.

Figure 6C. Impact of MJ on VDACs and Selected Molecules of Intracellular Energy Production.

INA-6 and MM.1S cells were exposed to 2 mM MJ for 1, 3 and 5 h. Changes in VDAC1, pVDAC2/3, HK2, GAPDH and ATP citrate lyase were measured by Immunoblot.

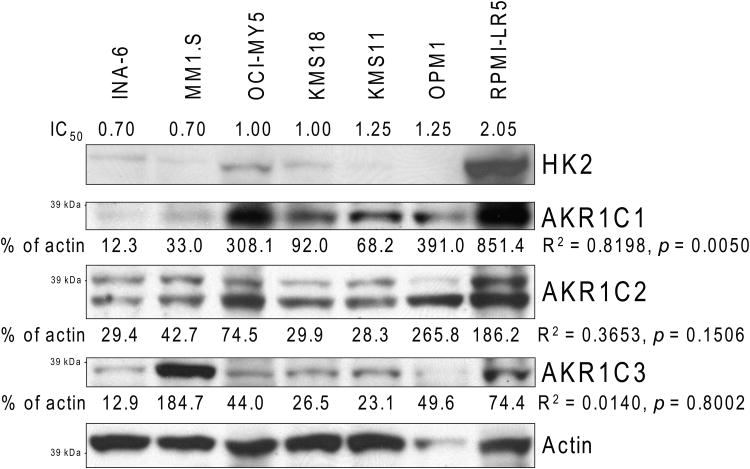

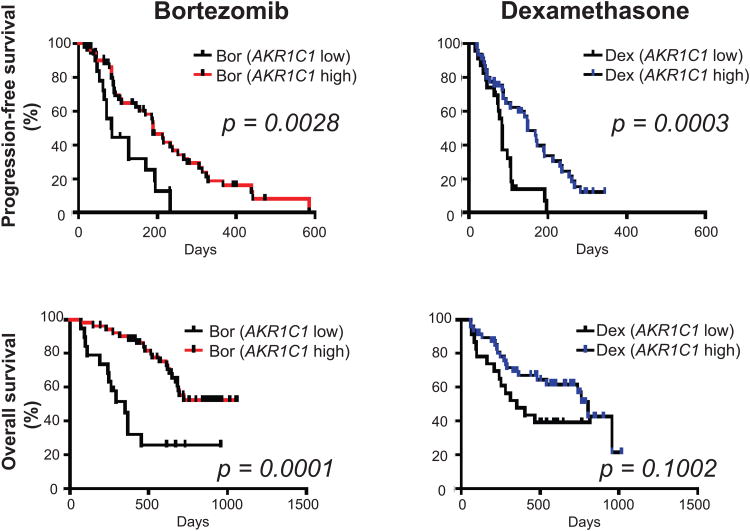

AKR1C family members are proven biomarkers for various types of cancers (Hsu, et al 2001, Ji, et al 2003, Tai, et al 2007, Vihko, et al 2005), and Davies, et al (2009) recently reported binding of MJ to these proteins. We therefore also analysed the protein levels of AKR1C1, AKR1C2 and AKR1C3 in our 7 MM cell line panel. As with HK2 and pVDAC2/3, there was a statistically significant correlation of MJ sensitivity and AKR1C1 protein levels (p = 0.005, R2 = 0.8198) (Fig. 7A). However, our results did not indicate a correlation of AKR1C2 (p = 0.1506, R2 = 0.3653) or AKR1C3 (p = 0.8002, R2 = 0.014) with MJ sensitivity. As low levels of AKR1C1 in MM cells correlates with MJ sensitivity, we sought to evaluate the clinical relevance of low AKR1C1 expression. We specifically evaluated whether low AKR1C1 levels correlate with clinical outcome in MM patients who participated in the randomized phase III trial APEX and who were treated with either bortezomib or dexamethasone. Patients with low levels of AKR1C1 had significantly shorter progression-free (p=0.0028 and p=0.0003, for bortezomib- and dexamethasone-treated patients, respectively) and overall (p=0.0001 and p=0.1002, for bortezomib- and dexamethasone-treated patients, respectively) survival (Fig. 7B). The observation that low levels of AKR1C1 are associated with adverse clinical outcome in MM, combined with the observation that low levels of AKR1C1 are associated with increased responsiveness to MJ, suggests that MJ treatment may be useful for a subset of MM patients who do not obtain maximal benefit from currently available treatments, such as proteasome inhibitors (specifically bortezomib) or dexamethasone.

Figure 7A. Methyljasmonate (MJ) Sensitivity & AKR1C Protein Levels.

Total cell protein extracts of different untreated MM cell lines were analysed by immunobloting for AKR1C1, AKR1C2 and AKR1C3. HK2 levels were determined to allow comparison with Fig. 6C. Bands on films were quantified with ImageJ software and normalized to the corresponding Actin control. Relative intensities are indicated. The values were analysed for correlation with the IC50 of the multiple myeloma cell lines as determined in Fig. 1A. Correlation coefficients and p-values are outlined.

Figure 7B. Correlation of AKR1C1 Transcript Expression in MM Patient Samples With Clinical Outcome.

We analysed the gene expression data of tumour cells from relapsed MM patients enrolled in the bortezomib (Bort)- or dexamethasone (Dex)-treated arms of the APEX clinical trial. Patients with low signal (<30th percentile of expression) for the AKR1C1 (204151_x_at) probe had shorter progression-free and overall survival in both the Bort- and the Dex-treated arm of the trial, compared to patients with high signal (>30th percentile of AKR1C1 expression).

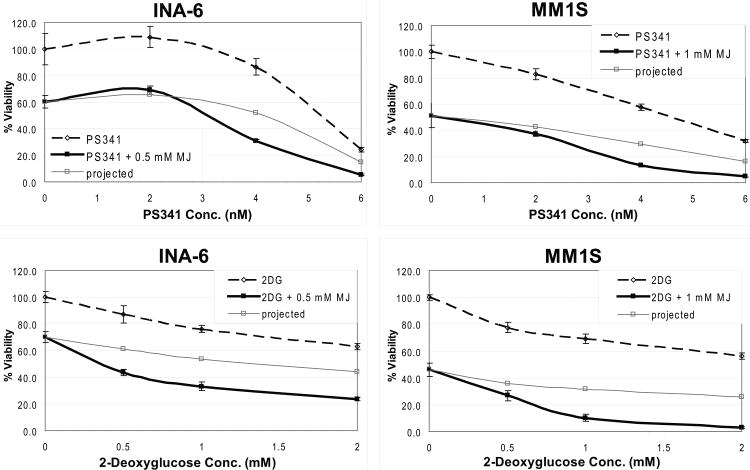

MJ a potential co-treatment with established MM drugs

Finally, we analysed how the drug affected other established compounds for treatment of MM patients. We detected additive killing and no antagonistic effects when MJ was used in combination with dexamethasone, lenalidomide (CC-5013), doxorubicin, or rapamycin (data not shown). When tested in combination with bortezomib (PS-341) the compound even exhibited synergy, similarly to the combination with 2-deoxyglucose, which was used in concordance with a previous report (Heyfets & Flescher 2007) as a positive control (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Methyljasmonate (MJ) Synergizes With Bortezomib.

MJ was tested in combination with established anti-multiple myeloma agents. INA-6 and MM.1S cells were exposed to the drugs as indicated for 24 h, and cell viability was analysed by MTT (3-(4,5- dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay. Combination with 2-Deoxyglucose served as a positive control for synergy, and “projected” lines illustrate additive killing.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to evaluate whether jasmonates could have the potential to be an active new class of drugs for the treatment of MM. We decided to use MJ in our experiments because this compound is easily commercially available. Moreover, we used MJ at concentrations in the mM range, which are pharmacologically relevant (Fingrut and Flescher 2002). This compound was found to exhibit a therapeutic window, as MJ doses of 0.5 – 2.5 mM were active against all tested MM cell lines and MM primary patient samples cells in vitro, without effect on non-malignant cells. Our in vivo results showed that effective concentrations could be achieved without major side effects.

Our mechanistic studies showed that MJ could induce killing in MM cells through pleiotropic intracellular mechanisms. It has been previously reported that the compound leads to apoptosis in most cancer cells tested (Fingrut and Flescher 2002, Kim, et al 2004, Kniazhanski, et al 2008, Yeruva, et al 2006), and we also observed that MJ induced apoptosis of MM cells associated with rapid loss of ATP. Additionally, we observed an enhanced release of HK2 from these cell organelles after MJ exposure. This suggests that anti-MM activity of MJ may be linked, at least in part, to its binding to mitochondria-bound HK2 inside the target cells, leading to detachment of that enzyme from the mitochondria membrane and in consequence to loss of cellular ATP, a mechanism also recently reported for the compound in CT-26 tumour cells (Goldin, et al 2008). More than 80 years ago, Warburg, et al (1927) demonstrated that tumour cells produce more energy by glycolysis than normal cells, a phenomenon today known as the “Warburg effect”. More recent research indicates that glycolysis is important for tumour cells to maintain a dysregulated metabolic state characterized by accumulation of oncometabolites, which in turn alter the activity of diverse cell signalling pathways and impair cellular differentiation (Ward & Thompson 2012). Thus, it is plausible that glycolysis plays a similar role in MM cell survival. These results would explain why MM and many other cancer cells are affected by MJ at significantly lower concentrations than normal cells, like PBMCs. Additionally, our studies indicate that MM cells with low baseline glycolytic activity as well as low levels of intracellular HK2 and pVDAC2/3 protein are most effectively targeted by MJ. Thus, an important determinant of the responsiveness of tumour cells to MJ may be the robustness of their glycolytic metabolism and possible oncometabolites associated with it. It is notable that exposure of MM cells to MJ was accompanied by significant impact on several major intracellular signalling pathways. Whether these changes are directly caused by the binding of MJ to key molecules in these signalling pathways or are simply a consequence of the rapid loss of intracellular ATP is under further investigation.

Given that prior studies indicated that members of the AKR1C family of enzymes can bind to MJ and be inhibited by it (Davies, et al 2009), we also evaluated whether the levels of AKR1C1, -2 and -3 enzymes in MM cells are correlated with MJ sensitivity. We observed that the protein levels of AKR1C1 in MM cell lines with low vs. high responsiveness to MJ followed a pattern of expression similar to HK2 or pVDAC2/3. There are conflicting reports in the literature about the role of AKR1Cs in cancer. Multiple studies characterize the role of AKR1Cs in breast and prostate tumours. Some state that AKR1C2 is impaired (Ji, et al 2004, Ji, et al 2007, Ji, et al 2003), while others postulate that AKR1Cs, especially AKR1C3, are over-expressed in those tumours, thereby supporting rapid cancer cell proliferation by producing tissue specific growth stimuli, such as androgens and estrogen (Penning and Byrns 2009, Stanbrough, et al 2006). Our results illustrate that myeloma cells with a high glycolytic activity also tend to contain higher levels of these AKR1Cs; however, more studies are needed to elucidate whether the AKR1C1 levels are merely a marker of increased dependence on glycolytic activity or whether they are etiologically associated with it. Interestingly, we observed that patient MM cells with low AKR1C1 transcript levels have shorter progression-free and overall survival when treated with bortezomib or dexamethasone in the phase III APEX trial in relapsed MM. Thus, the subset of patients that does not derive maximal benefit from bortezomib exhibits the same pattern of AKR1C1 expression as MM cells that are highly sensitive to MJ in vitro. Future studies will hopefully further evaluate the role of AKR1C1 transcript levels, as well as other parameters (e.g. cytogenetic profiles), as candidate markers of MM cell sensitivity to MJ.

In summary, our results show that MJ has anti-tumour activity in preclinical MM models. We identified a candidate marker, namely AKR1C1, of high in vitro responsiveness to MJ. The fact that this marker defines a subpopulation of MM patients with adverse prognosis to existing therapies raises the interesting possibility that jasmonates and agents with similar molecular characteristics may overcome clinical drug resistance. Moreover, our observation that MJ exhibits in vitro synergy with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib, further provides the framework for clinical evaluation of this new class of compounds, alone and in combination to improve patient outcome in MM.

Acknowledgments

Supported by “Dunkin Donuts Rising Stars” Program at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (to C.S.M), the Chambers Medical Foundation (P.G.R and C.S.M.), the Paul Stepanian Fund (C.S.M, P.G.R.), the Richard Corman Fund (P.G.R., C.S.M.) and National Institutes of Health Grants RO1-50947 (C.S.M and K.C.A).

Footnotes

Author's Contributions: SK: designed research, performed research, contributed vital new reagents, analysed data, and wrote the paper. JJ: performed research, and analysed data. JD, MO, EK: performed research, DM: contributed reagents and analytical tools. JL, PGR: contributed reagents and provided comments for the write-up of the paper. KCA: provided comments for the write-up of the paper. CSM: designed research and wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest: CSM has received in the past honoraria from Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck & Co., Centrocor, Celgene, Arno Therapeutics; licensing royalties from PharmaMar; and research funding from OSI Pharmaceuticals, Amgen Pharmaceuticals, AVEO Pharma, EMD Serono, Sunesis, Gloucester Pharmaceuticals, Genzyme and Johnson & Johnson. PGR is on Advisory Boards of Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Celgene, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Johnson & Johnson. KCA is on Advisory Boards of Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck, and Onyx.

References

- Damiano JS, Cress AE, Hazlehurst LA, Shtil AA, Dalton WS. Cell adhesion mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR): role of integrins and resistance to apoptosis in human myeloma cell lines. Blood. 1999;93:1658–1667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies NJ, Hayden RE, Simpson PJ, Birtwistle J, Mayer K, Ride JP, Bunce CM. AKR1C isoforms represent a novel cellular target for jasmonates alongside their mitochondrial-mediated effects. Cancer Research. 2009;69:4769–4775. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingrut O, Flescher E. Plant stress hormones suppress the proliferation and induce apoptosis in human cancer cells. Leukemia. 2002;16:608–616. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingrut O, Reischer D, Rotem R, Goldin N, Altboum I, Zan-Bar I, Flescher E. Jasmonates induce nonapoptotic death in high-resistance mutant p53-expressing B-lymphoma cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2005;146:800–808. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin N, Arzoine L, Heyfets A, Israelson A, Zaslavsky Z, Bravman T, Bronner V, Notcovich A, Shoshan-Barmatz V, Flescher E. Methyl jasmonate binds to and detaches mitochondria-bound hexokinase. Oncogene. 2008;27:4636–4643. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyfets A, Flescher E. Cooperative cytotoxicity of methyl jasmonate with anti-cancer drugs and 2-deoxy-D-glucose. Cancer Letters. 2007;250:300–310. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu NY, Ho HC, Chow KC, Lin TY, Shih CS, Wang LS, Tsai CM. Overexpression of dihydrodiol dehydrogenase as a prognostic marker of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Research. 2001;61:2727–2731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii Y, Kiyota H, Sakai S, Honma Y. Induction of differentiation of human myeloid leukemia cells by jasmonates, plant hormones. Leukemia. 2004;18:1413–1419. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Q, Chang L, VanDenBerg D, Stanczyk FZ, Stolz A. Selective reduction of AKR1C2 in prostate cancer and its role in DHT metabolism. Prostate. 2003;54:275–289. doi: 10.1002/pros.10192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Q, Aoyama C, Nien YD, Liu PI, Chen PK, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Stolz A. Selective loss of AKR1C1 and AKR1C2 in breast cancer and their potential effect on progesterone signaling. Cancer Research. 2004;64:7610–7617. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Q, Chang L, Stanczyk FZ, Ookhtens M, Sherrod A, Stolz A. Impaired dihydrotestosterone catabolism in human prostate cancer: critical role of AKR1C2 as a pre-receptor regulator of androgen receptor signaling. Cancer Research. 2007;67:1361–1369. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Lee SY, Oh SY, Han SI, Park HG, Yoo MA, Kang HS. Methyl jasmonate induces apoptosis through induction of Bax/Bcl-XS and activation of caspase-3 via ROS production in A549 cells. Oncology Reports. 2004;12:1233–1238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kniazhanski T, Jackman A, Heyfets A, Gonen P, Flescher E, Sherman L. Methyl jasmonate induces cell death with mixed characteristics of apoptosis and necrosis in cervical cancer cells. Cancer Letters. 2008;271:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillin DW, Delmore J, Weisberg E, Negri JM, Geer DC, Klippel S, Mitsiades N, Schlossman RL, Munshi NC, Kung AL, Griffin JD, Richardson PG, Anderson KC, Mitsiades CS. Tumor cell-specific bioluminescence platform to identify stroma-induced changes to anticancer drug activity. Nature Medicine. 2010;16:483–489. doi: 10.1038/nm.2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan G, Mitsiades C, Bryant B, Zhan F, Chng WJ, Roels S, Koenig E, Fergus A, Huang Y, Richardson P, Trepicchio WL, Broyl A, Sonneveld P, Shaughnessy JD, Jr, Bergsagel PL, Schenkein D, Esseltine DL, Boral A, Anderson KC. Gene expression profiling and correlation with outcome in clinical trials of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Blood. 2007;109:3177–3188. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-044974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nefedova Y, Landowski TH, Dalton WS. Bone marrow stromal-derived soluble factors and direct cell contact contribute to de novo drug resistance of myeloma cells by distinct mechanisms. Leukemia. 2003;17:1175–1182. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penning TM, Byrns MC. Steroid hormone transforming aldo-keto reductases and cancer. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1155:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, Irwin D, Stadtmauer EA, Facon T, Harousseau JL, Ben-Yehuda D, Lonial S, Goldschmidt H, Reece D, San-Miguel JF, Blade J, Boccadoro M, Cavenagh J, Dalton WS, Boral AL, Esseltine DL, Porter JB, Schenkein D, Anderson KC. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:2487–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, Golub TR, Rubin MA, Penning TM, Febbo PG, Balk SP. Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Research. 2006;66:2815–2825. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai HL, Lin TS, Huang HH, Lin TY, Chou MC, Chiou SH, Chow KC. Overexpression of aldo-keto reductase 1C2 as a high-risk factor in bladder cancer. Oncology Reports. 2007;17:305–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong QS, Jiang GS, Zheng LD, Tang ST, Cai JB, Liu Y, Zeng FQ, Dong JH. Methyl jasmonate downregulates expression of proliferating cell nuclear antigen and induces apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cell lines. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19:573–581. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3282fc46b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihko P, Herrala A, Harkonen P, Isomaa V, Kaija H, Kurkela R, Li Y, Patrikainen L, Pulkka A, Soronen P, Torn S. Enzymes as modulators in malignant transformation. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2005;93:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. The Metabolism of Tumors in the Body. Journal of General Physiology. 1927;8:519–530. doi: 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic Reprogramming: A Cancer Hallmark Even Warburg Did Not Anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi R, Andreyev A, Murphy AN, Perkins GA, Ellisman MH, Newmeyer DD. Mitochondria frozen with trehalose retain a number of biological functions and preserve outer membrane integrity. Cell Death Differentiation. 2007;14:616–624. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeruva L, Pierre KJ, Carper SW, Elegbede JA, Toy BJ, Wang RC. Jasmonates induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in non-small cell lung cancer lines. Experimental Lung Research. 2006;32:499–516. doi: 10.1080/01902140601059604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]