Abstract

Importance

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic illness of childhood.

Objective

The goal of this study was to evaluate the association between Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) variation and the persistence of skin symptoms of AD.

Design

Prospective cohort study

Setting

General community

Participants

Children enrolled in the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry.

Exposures

Evaluation of TSLP variation.

Main outcomes and measures: Self-reported outcome of whether or not a child’s skin was AD symptom-free for 6-months at 6 month intervals.

Results

We evaluated 14 variants of TSLP. TSLP variant rs1898671 was significantly associated with the outcome in white subjects (p = 0.014). As measured by overlapping confidence intervals, similar ORs were noted among whites (1.72 (1.11, 2.65)) and African-American (1.34(0.51, 3.51)). Further within the subcohort of individuals with a FLG loss of function mutation, those with TSLP variation were more likely to have less persistent disease ((4.92 (2.04, 11.86)).

Conclusions and relevance

With respect to the clinical persistence of AD, TSLP variation is associated with less persistent disease. Therefore, TSLP may be a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of AD, especially in those with diminished barrier function due to FLG mutations. This is an attractive hypothesis that can be tested in clinical trials.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic relapsing inflammatory disease of the skin that is most often seen in childhood1. The development of AD has been associated with genetic polymorphisms, skin barrier dysfunction, environmental exposures, and host immune dysregulation2;3. Conceptually, the pathophysiology of AD may be due to a child’s sensitization to specific environmental or food allergens in association with skin barrier dysfunction, which is hypothesized to result from defects in the production of filaggrin protein (FLG), a key constituent of the granular cell layer3. In 2006, loss-of-function mutations in the FLG gene were shown to be associated with AD4–6. Ultimately, FLG proteolysis results in the creation of natural moisturizing factors that are part of the skin barrier. Animal models have shown that a defect in the production of FLG creates a more porous skin surface resulting in epi-cutaneous sensitization to environmental allergens, activating the host immune system, thereby resulting in local inflammation, pruritus, and visible skin lesions7.

In 2010 Gao et al reported an association between thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) and AD as well as a decreased susceptibility to an infectious inflammatory complication of atopic dermatitis called eczema herpeticum8;9. TSLP promotes the differentiation of naïve T- cells into T helper type 2 (TH2) cells, a cell type associated with and thought to be pathogenic in atopic diseases10;11. Increased expression of TSLP has been strongly associated with AD as well as other allergic diseases including asthma, allergic rhinitis, and food allergy9;11–14. Furthermore, a report by Beck et al revealed that those who developed eczema herpeticum had more severe AD as well as biomarkers consistent with increased allergic inflammation15. This leads to our hypothesis that genetic variations that result in increased or decreased TSLP activity could be associated with either more severe or milder skin disease.

More specifically, alterations in the activity of TSLP should directly influence the association between FLG and AD persistence. As noted, FLG mutations result in skin barrier dysfunction and are associated with an increased risk of developing AD and persistence of skin symptoms4;16;17. Since TSLP acts to promote TH2 cell responses, it is conceivable that those with diminished TSLP expression, even in the setting of skin barrier dysfunction due to a FLG loss-of-function mutation, would be less likely to exhibit active symptoms of AD. The goal of this study was to first evaluate the association between TSLP variation and the persistence of skin symptoms of AD and then to determine if TSLP variation alters the known association between FLG loss-of-function mutations and the persistence of AD.

Methods

The Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER), www.thepeerprogram.com, is an ongoing prospective 10-year observational registry that is part of a post-marketing commitment originally by Novartis and now Valeant to the FDA and the European Drug Agency. The goal of this longitudinal safety study is to determine if there is a long-term risk of malignancy associated with the use of pimecrolimus cream 1% in a real-world setting. To be eligible for enrollment, a subject must be more than 2-years of age, not currently have cancer, have AD, and have used at least 6 weeks of pimecrolimus (cumulative) in the previous 6 months. In most cases, the parent of the enrolled participant completes the biannual questionnaire. All individuals completed an additional informed consent approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania and provided a saliva sample from which DNA was extracted.

We recently published our findings on FLG associations with AD in the Pediatric Eczema Elective Registry (PEER)16. In light of the findings from Gao et al, we extended our study of PEER participants to evaluate the 14 tag SNPs, selected by Gao et al, in TSLP using a custom Ilumina Goldengate SNP chip (Illumina, San Diego, CA)9;16. Tag SNPs are SNPs that are believed to represent a region of a candidate gene thereby making it possible to investigate a gene without evaluating every known polymorphism of that gene. FLG mutations were assessed via TaqMan® assay and were evaluated for the presence or absence of any FLG null mutation16. The call rate for all assays exceeded 90% unless otherwise noted. Ancestry was determined using a panel of previously described ancestral informative markers (AIMS) and was estimated using clustering techniques as implemented in STRUCTURE16;18–20. Genetically derived ancestry was highly correlated with self-reported race (i.e. white-those of European ancestry and African-American, those of African Ancestry) in this cohort16.

We investigated the self-reported outcome of whether or not a child’s skin was AD symptom-free for 6-months while not requiring the use of topical medication (e.g., steroids or calcineurin inhibitors to treat their AD). The symptom-based question was, “During the last 6 months, would you say your child’s skin disease has shown: complete disease control, good disease control, limited disease control, or uncontrolled disease control”. In order to be “symptom-free” the child had to have complete disease control for the preceding 6-month period. Our evaluation of “symptoms” was likely primarily based on pruritus and skin breakdown and may not include other symptoms or signs of AD such as lichenification, pityriasis alba, xerosis, keratosis pilaris, etc. Since individuals in this study were followed longitudinally and surveyed every six months, this outcome was reported on more than one occasion. We assessed the statistical association between the repeated measures of the binary outcome and each SNP assuming an additive genetic model within a mixed effects framework called a generalized linear latent and mixed model (GLLAMM). Because our outcome is binary, the logistic link function was used with a binomial family with an adaptive quadrature. The GLLAMM model has both random effects and fixed effects terms, allowing for subject-specific regression coefficients or subject-specific estimates of the association of a risk factor and the outcome. In other words, the GLLAMM models can be more useful if relationships between an outcome and an individual are more important than inferences about the population21;22. The decision to correct or not correct for multiplicity is a complex and complicated issue. There is no universal solution because the decision to adjust a p-value depends on the study design and hypothesis. The primary question in our study was the confirmation of previously described SNPs by Gao et al with respect to a new outcome (i.e., persistence of AD) and a pre-specified hypothesis; therefore, we did not correct for multiple testing23. All SNP association tests were conducted separately within the two sub-groups based on race, whites and African-Americans. In addition, a pooled analysis that combined whites and African-Americans (with adjustment for principal components derived from ancestry informative markers)24 as well as stratified analyses based on FLG and asthma status were also conducted. Finally, a meta-analysis was also conducted to combine SNP association results across races. This was implemented in METAL and included a test for heterogeneity using Cochran’s Q statistic25.

All analyses were conducted using STATA 12.1 (College Park, TX).

Results

DNA for genotyping was available from as many as 796 PEER subjects. We have previously published a description of PEER participants who provided DNA and those who did not showing that no clinically important differences exist26. With respect to our current study cohort, 51.9% were female, 46.1% were African-American (n=367), the average age at PEER enrollment was 7.1 (±3.7) years, and participants were followed for an average of 5.7 (±1.4) years or approximately 4,799 person-years. At the time of enrollment, 3.2% of the children had complete disease control, 43.9% noted good disease control, 42.2% noted limited disease control, and 10.7% noted uncontrolled disease.

Table 1 presents the unadjusted association of TSLP tagging SNPs with the persistence of AD over time by race. One SNP, rs10213865, was not evaluated further because the genotyping call rate was less than 90% and thus considered inadequate. Rs1898671 was significantly associated with the outcome in white subjects (p = 0.014). As measured by overlapping confidence intervals, similar ORs were noted among whites (1.72 (1.11, 2.65)) and African-Americans (1.34(0.51, 3.51)). Rs764916 also attained statistical significance in whites (p = 0.031). However, the ORs were in opposite directions within the white and African-American sub-groups, and the SNP was not significant in the pooled analysis (white and African-Americans analyzed together as a single group) with adjustment for covariates.

Table 1.

Association of TSLP SNPs with outcome (symptom free for 6-months while not requiring the use of topical medication)

| SNP | Minor allele | Major allele | White OR (95% CI) N |

MAF | African-American OR (95% CI) N |

MAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1837253 | A | G | 0.64(0.40,1.01) p=0.054 N=393 |

0.288 | 1.16(0.58,2.32) p=0.673 N=334 |

0.250 |

| rs17551370 | A | G | 0.70(0.39,1.26) p=0.236 N=393 |

0.147 | 2.15(0.84,5.49) p=0.112 N=334 |

0.097 |

| rs3806933 | A | G | 0.82(0.53,1.26) p=0.364N=393 |

0.430 | 1.42(0.74,2.71) p=0.293 N=334 |

0.277 |

| rs2289276 | A | G | 0.96(0.60,1.54) p=0.862 N=393 |

0.278 | 0.99(0.46,2.10) p=0.972 N=333 |

0.191 |

| rs1898671 | A | G | 1.72(1.11,2.66) p=0.014 N=398 |

0.333 | 1.33(0.52,3.45) p=0.553 N=334 |

0.100 |

| rs10062929 | A | C | 0.65(0.38,1.10) p=0.107 N=386 |

0.165 | 1.90(0.78,4.60) p=0.157 N=330 |

0.097 |

| rs11466750 | A | G | 0.84(0.50,1.43) p=0.528 N=390 |

0.165 | 0.94(0.46,1.92) p=0.872 N=334 |

0.232 |

| rs2289277 | C | G | 0.84(0.55,1.29) p=0.426 N=393 |

0.440 | 1.26(0.68,2.33) p=0.465 N=335 |

0.412 |

| rs10035870 | G | A | 0.54(0.06,5.17) p=0.592 N=391 |

0.009 | 0.51(0.19,1.33) p=0.166 N=335 |

0.119 |

| rs11466749 | G | A | 0.96(0.57,1.64) p=0.528 N=393 |

0.174 | 2.02(0.83,4.90) p=0.119 N=334 |

0.112 |

| rs2416259 | G | A | 0.88(0.48,1.59) p=0.664 N=393 |

0.144 | 1.35(0.32,5.64) p=0.687 N=335 |

0.048 |

| rs764916 | C | G | 0.44(0.20,0.93) p=0.031 N=387 |

0.074 | 1.02(0.49,2.11) p=0.954 N=332 |

0.202 |

| rs11466741 | A | G | 1.01(0.64,1.60) p=0.956 N=393 |

0.291 | 0.76(0.40,1.44) p=0.397 N=334 |

0.310 |

| rs10043985 | C | A | 1.49(0.87,2.55)* p=0.150 N=392 |

0.073 | 1.09(0.62,1.91)* p=0.768 N=335 |

0.197 |

N= maximum available for assessment * not in Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium; OR = Odds Ratio; N=sample size; CI = Confidence Intervals; MAF = Minor allele frequency

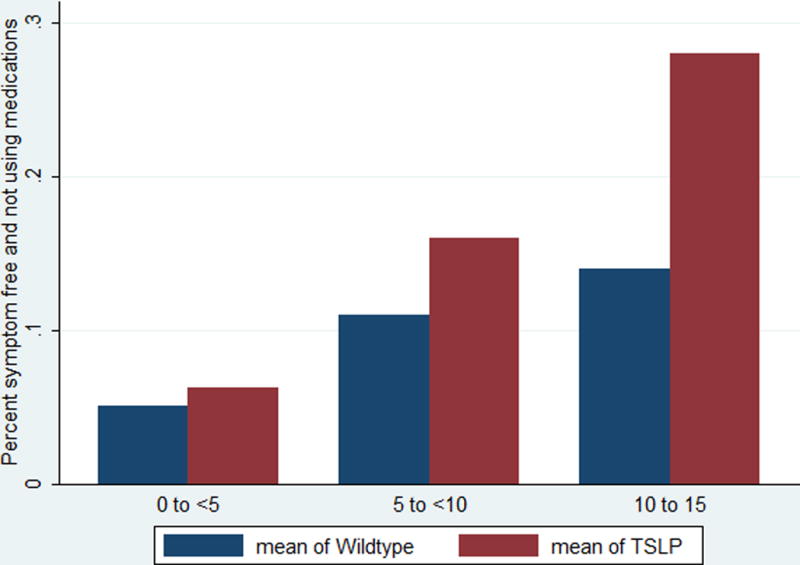

Figure 1 shows the frequency of reporting that an individual’s AD was not persistent based on their age in categories at the time of reporting and stratified by the presence or absence of variation in rs1898671. As expected persistence of AD symptoms decrease as the PEER population got older but within each age category those with rs1898671 variation were less likely to have persistent AD. Further analysis of rs1898671 after adjustment for multiple covariates are presented in Table 2. Similar p-values were noted for the pooled approach and the meta-analysis approach (p= 0.027 and p=0.029, respectively). Results presented in Table 2 for the combined population are the ones from the pooled approach. Rs1898671 was the only SNP that was statistically significant after appropriate adjustments based on gender, ancestry, presence of a FLG mutation, and age of onset of AD in the combined population (1.55 (1.01, 2.30)). The results from the adjusted sub-group analyses were almost identical with the unadjusted analyses. FLG loss-of- function mutations were present in 69 individuals with rs1898671 variation. The association between TSLP rs1898671 variation and the persistence of AD in the presence (N=134) or absence (N=598) of FLG loss-of-function mutation is also presented separately for these two subgroups in Table 2. The strength of the association was influenced by the absence (i.e., FLG wildtype) or presence of a FLG loss- of-function mutation (1.52 (1.01, 2.29) and 4.92 (2.04, 11.86), respectively for the the subgroups of children without or with FLG mutation). In the PEER cohort, rs1898671 was not associated with the risk of asthma.

Figure 1.

Age by category and the absences of symptoms- The the actual age at the time a survey was received in three age categories of the percent of subjects reporting no symptoms and not using medication for those with the rs1988671 TSLP variant and without (wildtype). As noted, individuals were followed over time and provided more than one survey.

Table 2.

Association of rs1898671 with outcome (symptom-free for 6-months while not requiring the use of topical medication)

| Adjusted* | FLG wildtype | FLG loss-of-function mutation | Asthma ‡ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | |

| Combined white and African-American | 732 | 1.55 1.01, 2.30) p=0.029 |

598 | 1.52 (1.01, 2.29) p=0.046 |

134 | 4.92 (2.04,11.86) p=0.00039 |

732 | 1.02 (0.81,1.30) p=0.837 |

| white | 398 | 1.72 (1.12,2.63) p=0.013 |

284 | 1.18 (0.73,1.91) p=0.485 |

114 | 5.68 (2.18, 14.82) p=0.00038 |

398 | 1.11 (0.81,1.50) p=0.515 |

| African-American | 334 | 1.32 (0.52,3.34) p=0.555 |

314 | 1.53 (0.58,4.05) p=0.390 |

20 | Not estimated † | 334 | 1.07 0.64,1.80) p=0.777 |

adjusted for age of onset of AD, presence of FLG mutation, gender, and ancestry.

not estimated because only 5 individuals had FLG loss of function mutations and the TSLP variant.

Logistic regression model evaluating rs1898671 as a risk for asthma diagnosis. OR = Odds Ratio; CI = Confidence Intervals.

Discussion

TSLP has been shown to be a master initiator of allergic inflammation11;14. While FLG protein contributes to the skin barrier, TSLP expression occurs after antigen sensitization through a disrupted skin barrier and subsequently promotes the immune responses that result in inflammation that leads to AD4;11;14. Recently, siRNA-mediated knockdown of FLG expression was shown to induce TSLP expression in epidermal keratinocytes27. Gao et al had evaluated TSLP variation as a risk factor for developing AD and for the diagnosis of eczema herpeticum (ADEH) among those with AD and noted that rs1898671 was associated with a decreased risk of ADEH9. We found that this variant was also associated with decreased likelihood of having persistent AD (i.e., more likely to report an AD symptom-free state not requiring topical medication). Taken together, these findings can be explained by the presence of a genetic variant (or variants) resulting in diminished TSLP protein activity that is protective in terms of development of cutaneous inflammation and allergy11;28. This hypothesis is further substantiated by the effect of rs1898671 on FLG loss-of-function mutations. Individuals who have FLG loss-of-function mutation are more likely to have persistent AD16; however, within the subcohort of individuals with a FLG loss-of-function mutation, those who also had an rs1898671 variant were nearly 5 times less likely to have persistent AD as compared to those without the variant. Further, previous findings have shown that those with increased TSLP activity are more prone to asthma3. However, in our AD cohort, the rs1898671 variant (e.g., less active TSLP) did not confer any additional risk for asthma.

FLG loss-of-function mutations are most commonly found in individuals of European and Asian ancestry but not in those of African ancestry4. The FLG mutations assayed in this study are most commonly noted in those of European ancestry and are very rarely seen in those of African ancestry4;16. For example, in our previous study of this cohort, 27% of whites carried a FLG loss-of-function mutation (MAF = 0.16), compared to only 5.7% of African-Americans (MAF=0.03)16. As a result, many studies have focused solely on individuals of European ancestry in order to diminish concerns about population stratification, which is a form of bias that can result when genetic variation is associated with ancestry24. In this study, differing rates of carriage of rs1898671 does occur based on ancestry but not to the extreme noted for FLG. In addition, our ultimate question was based on the interaction of TSLP and FLG. We therefore have presented results from a pooled analysis as well as from analysis carried out separately in whites and African-Americans.

As is true of all studies, there are limitations to the interpretation of our results. First, those enrolled in the PEER must have been treated with at least 6 weeks of pimecrolimus (cumulative) in the 6 months prior to entry into PEER. Most children, however, do not continue with this therapy while in PEER29. Pimecrolimus is approved for the use in those with mild to moderate AD. It is therefore possible that the results of our study will not generalize to everyone with AD. However, it is important to remember that rs1898671 was identified in a cohort of individuals with AD9. The primary interest of that investigation was to study eczema herpecticum; so it is likely that those individuals may have had more severe AD9. However, an important contribution of our study is the potential confirmation of the interplay between barrier dysfunction and immune activation and it is likely that this observation is generalizable. It is also important to realize that we tested the four most common European FLG mutations. These FLG mutations have been found only rarely in those of African ancestry. It is possible that mutations also exist in other barrier proteins30–32. Interactions between these yet to be identified mutations and the TSLP variation described in our study could potentially influence the outcome in a different manner than described in the current study. This concern, however, can only be addressed as additional mutations are found. Because all children enrolled in PEER had to have used pimecrolimus prior to entry into the study, it may be possible that rs1898671 variation interacts with pimecrolimus therapy resulting in an improved outcome. However, by the third year of enrollment more than 45%of PEER participants were no longer using pimecrolimus so we think that this is explanation is unlikely29.

We choose to not correct our p-values for multiple comparisons. This was based on the notion that our study was guided by a hypothesis established from previously published data9. Our hypothesis was that diminished TSLP activity would lead to less persistent AD even in the setting of FLG loss of function mutation. Our initial interest in diminished protein activity parallels the assumptions used by those who originally investigated FLG4. Because TSLP is a master inducer of inflammation, diminishing the function of the TSLP protein should diminish the inflammatory component of AD10;11. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation noted in Gao et al with respect to eczema herpecticum and is also consistent with our observations (e.g. diminished inflammation due to diminished TSLP activity resulted in fewer cases of eczema herpecticum and less persistent AD, respectively)9–11;15. A statistical observation more pertinent to this observation would be the probability that in two independent studies evaluating 14 SNPs only the same one was statistically significant in both. The probability of finding this observation is 0.009.

It is important to realize that rs1898671 is a tag SNPof the TSLP gene. Further investigations, including fine-mapping and functional investigations of the TSLP protein, need to be conducted in order to determine the causal variant with respect to the persistence of AD. We also did not evaluate whether rs1898671 is associated with the onset of AD. As with many illnesses, agents that cause a disease or affect its severity/ persistence are often not the same. Further, we did not study TSLP protein levels in our subjects. It is, however, noteworthy that rs1898671 has now been validated in at least two different cohorts, by different investigators (Gao et al9 and us). Based on our evaluation of the persistence of AD, inhibition of or diminution of the effect of TSLP may be a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of AD, especially in those with diminished barrier function due to FLG mutations. This is an attractive hypothesis that could be tested in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by R01-AR0056755 from the National Institute of Arthritis Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. The PEER study is funded by a grant from Valeant Pharmaceuticals. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection of genetic data, analysis or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript. All authors had access to the data in the study. All authors approve the final version of the manuscript. DJM, AJA, OH, JG, and NM take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design and acquisition: DJM, OH, MP, JG, and NM. Analysis and interpretation of the data: All authors. Drafting of manuscript: All authors. Critical revision of the manuscript: All authors. Statistical analysis: DJM, JG, OH, and NM. Obtaining funding: DJM. Administrative, technical and material support: OH and MP. Study supervision: DJM and NM. Content presented in this manuscript was previously presented as an oral abstract at the International Investigative Dermatology Meeting in Edinburgh Scotland 2012.

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest regarding this manuscript.

References

- 1.Leung DY, Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. [Review] [100 refs] Lancet. 2003;361:151–160. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramovits W, Abramovits W. Atopic dermatitis. [Review] [72 refs] Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2005;53:S86–S93. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kabashima K. New concept of the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis: Interplay among the barrier, alelrgy, and pruritius as a trinity. Journal of Dermatological Science. 2013;70:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown SJ, McLean WH. One remarkable molecule: filaggrin. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2012;132:751–762. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith FJ, Irvine AD, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the gene encoding filaggrin cause ichthyosis vulgaris. Nature Genetics. 2006;38:337–342. doi: 10.1038/ng1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irvine AD, McLean WH, Leung DY. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. [Review] New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:1315–1327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fallon P, Sasaki T, Sandilands A, et al. A homozygous frameshift mutation in the mouse Flg gene facilitates enhanced percutaneous allergen priming. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:602–608. doi: 10.1038/ng.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnes KC. An update on the genetics of atopic dermatitis: scratching the surface in 2009. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2010;125:16–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao PS, Rafaels NM, Mu D, et al. Genetic variants in thymic stromal lymphopoietin are associated with atopic dermatitis and eczema herpeticum. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2010;125:1403–1407. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demehri S, Morimoto M, Holtzman MJ, Kopan R. Skin-derived TSLP triggers progression from epidermal-barrier defects to asthma. Plos Biology. 2009;7:e1000067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esnault S, Rosenthal LA, Wang DS, Malter JS. Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin (TSLP) as a Bridge between Infection and Atopy. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2008;1:325–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherrill JD, Gao PS, Stucke EM, et al. Variants of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and its receptor associate with eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2010;126:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li M, Hener P, Zhang Z, Ganti KP, Metzger D, Chambon P. Induction of thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression in keratinocytes is necessary for generating an atopic dermatitis upon application of the active vitamin D3 analogue MC903 on mouse skin. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2009;129:498–502. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soumelis V, Reche PA, Kanzler H, et al. Human epithelial cells trigger dendritic cell mediated allergic inflammation by producing TSLP. Nature Immunology. 2002;3:673–680. doi: 10.1038/ni805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck LA, Boguniewicz M, Hata T, et al. Phenotype of atopic dermatitis subjects with a history of eczema herpecticum. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2009;124:260–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margolis DJ, Apter AJ, Gupta J, et al. The persistence of atopic dermatitis and Filaggrin mutations in a US longitudinal cohort. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2012;130:912–917. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandilands A, Terron-Kwiatkowski A, Hull PR, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the gene encoding filaggrin uncovers prevalent and rare mutations in ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic eczema. Nature Genetics. 2007;39:650–654. doi: 10.1038/ng2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Rosenberg NA, et al. Association mapping in structured populations. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2000;67:170–181. doi: 10.1086/302959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiner AP, Carlson CS, Ziv E, et al. Genetic ancestry, population sub-structure, and cardiovascular disease-related traits among African-American participants in the CARDIA Study. Human Genetics. 2007;121:565–575. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0350-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stefflova K, Dulik MC, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Pai AA, Walker AH, Rebbeck TR. Dissecting the within-Africa ancestry of populations of African descent in the Americas. PLoSOne. 2011;6:e14495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabe-Hesketh S, Pickles A, Skrondal A. GLLAMM Manual. 2001/01, 1–138 10-28-2001. Institute of Psychiatry, Kiing’s College, University of London; [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, Pickles A. Reliable estimation of generalized linear mixed models using adaptive quadrature. The Stata Journal. 2002;2:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bender R, Lange S. Adjusting for multiple testing-when and how? Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2001;54:343–349. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00314-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bouaziz M, Ambroise C, Guvedj M. Accounting for population stratificaion in practice: A comparison of the main strategies dedicated to genome-wide associations studies. PLoSOne. 2011;6:e28845. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willer C, Li Y, Avecasis G. METAL: Fast and efficient meta-analysis of genome-wide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Margolis DJ, Papadopoulos M, Apter AJ, McLean WH, Mitra N, Rebbeck TR. Obtaining DNA in the mail from a national sample of children with a chronic non-fatal illness. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2011;131:1765–1767. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee KH, Cho KA, Kim JY, et al. Filaggrin knockdown and toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) stimulation enchanced the production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) from epidermal layers. Experimental Dermatology. 2011;20:145–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2010.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. Atopic dermatitis: a disease of altered skin barrier and immune dysregulation. Immunological Reviews. 2011;242:233–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01027.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kapoor R, Hoffstad O, Bilker W, Margolis DJ. The frequency and intensity of topical pimecrolimus treatment in children with physician-confirmed mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. Pediatric Dermatology. 2009;26:682–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marenholz I, Rivera VA, Esparza-Gordillo J, et al. Association screening in the Epidermal Differentiation Complex (EDC) identifies an SPRR3 repeat number variant as a risk factor for eczema. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2011;131:1644–1649. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Z, Hansmann B, Meyer-Hoffert U, Glaser R, Schroder JM. Molecular identification and expression analysis of filaggrin-2, a member of the S100 fused-type protein family. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellerin L, Henry J, Hsu CY, et al. Defects in filaggrin-like proteins in both lesional and nonlesional atopic skin. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 2013;131:1094–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]