Abstract

Adolescents’ beliefs about family obligation often reflect cultural variations in their family context, and thus are important for understanding development among diverse youth. In this study, we test hypotheses about the role of family obligation values in risk behavior and mental health in a sample of 194 low-income adolescent girls (Mean age = 15.2; 58% Latina, 28% African-American/Black). We hypothesized that family obligation values can be both a protective and vulnerability factor, depending on the type of outcome and the presence of other risk factors. Across the sample, higher family obligation values tended to occur with indicators of positive family functioning (e.g., more frequent communication, less maternal hostility) based on mother and adolescent reports. As hypothesized, family obligation values moderated the relationship between established risk factors and adjustment in distinct ways, such that high family obligation values decreased risk in some domains (i.e., a protective factor) but increased risk in other domains (i.e., a vulnerability factor). Specifically, high family obligation values diminished the relationship between peer norms for risky behavior (sex and substance use) and individual engagement in those behaviors. At the same time, high family obligation values magnified the relationship between exposure to negative life events and poor mental health (PTSD and depressive symptoms). The results suggest that family obligation is an important but complex aspect of development among diverse adolescent girls.

Keywords: Family obligation, risk behavior, emotional adjustment, low-income adolescents

Introduction

By 2020, it is estimated that more than half of American youth will be members of racial or ethnic minority groups, and approximately 20% of families will include a parent born outside of the United States (Frey, 2012). In response to increasing diversity, developmental researchers have sought to understand similarities and differences between youth from various racial, ethnic and national backgrounds. Within this broad body of literature, there is evidence of many common developmental themes and challenges during adolescence, including greater autonomy from parents, increased focus on peer and romantic relationships, exposure to more negative life events, and heightened vulnerability to certain forms of maladjustment (Arnett, 2009). These tasks and challenges may be navigated in different ways, however, reflecting group-level variations in how cultural values are infused into family life within a pluralistic society (Edwards, Knocke, Aukrust, Kumre & Kim, 2006). For example, in cultural groups that emphasize interdependence, values and expectations related to family relationships, such as family obligation, influence adolescent behaviors and outcomes (Greenfield, Keller, Fuligni, & Maynard, 2003). Based on these theoretical models (i.e., Edwards et al., 2013; Greenfield et al., 2006), research on constructs such as family obligation can further our understanding of adolescent development in an increasingly diverse society.

Family obligation reflects a sense of duty to support, respect, and provide assistance to family members. Implicit and explicit expectations about these obligations often serve as a guide to relational behaviors within the family. Family obligation first emerged as an important construct in research on adult behavior towards aging adults (Stein, 1992); however, research by Fuligni and colleagues (e.g., Fuligni, Tseng & Lam, 1999) has demonstrated its relevance during adolescence and early adulthood, particularly among youth of color. Early research on adolescent family obligation demonstrated group differences by race, ethnicity and immigrant status (e.g., Fuligni et al., 1999; Hughes, 2001), and linked family obligation to educational outcomes (e.g., Fuligni, 2007; Sy & Brittian, 2008) and emotional and behavioral adjustment (e.g., Juang & Cookston, 2009; Yau, Taspoulos-Chan & Smetana, 2009) among diverse youth. More recent studies have extended our understanding of family obligation in two important ways. First, researchers have shown the importance of distinguishing between family obligation values (e.g., respect for elders) and family obligation behaviors (e.g., actual time spent helping family members) because their impact may differ (e.g., Telzer, Gonzales, & Fuligni, 2014; Tseng, 2004). Second, recent studies highlight the need to move beyond main effects models to consider how family obligation values and behaviors interact with other factors in shaping adolescent development (e.g., Kiang et al., 2013; Telzer et al., 2014).

Drawing from this body of literature, we test hypotheses about how family obligation values may act as both a vulnerability and protective factor in the emotional and behavioral adjustment of adolescent girls. We hypothesized that family obligation values would moderate associations between well-established risk factors and maladjustment in differing ways, such that a high sense of family obligation decreases the likelihood of some negative outcomes (i.e., family obligation as a protective factor), yet increases the likelihood of other negative outcomes (i.e., family obligation as a vulnerability factor).

Family obligation values as a protective factor

Adolescence involves an increase in potentially risky behaviors, including sexual activity and substance use. While some engagement in sexual activity and substance use is normative, higher levels can be problematic and result in long-term consequences, including unplanned pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, cognitive impairment, accidental injury, and involvement with the legal system. As a result, sexual activity and substance use can become developmental snares that keep adolescents from reaching their adult potential.

One of the most widely documented risk factors for risky sexual behavior and substance use is peer engagement. Adolescents who believe their peers are engaged in certain activities are more likely to engage in these activities themselves, even if these perceptions are not accurate (for review, see Wolfe, Jaffe & Crooks, 2006). Perceived peer engagement determines what an adolescent believes is normative, and these norms can then shape decisions about whether or not to engage in a specific activity. High levels of perceived peer engagement may also indicate that an adolescent has more frequent opportunities to engage in potential risky behavior.

Plausibly, family obligation values may moderate the link between peer norms for risky behaviors and individual engagement in those behaviors. Specifically, adolescents with high family obligation values may be less influenced by perceived peer norms, even when they believe that peers are involved in risky behaviors. For example, adolescents who feel strong respect for familial authority figures may be less likely to go against parental expectations or rules. Similarly, adolescents with a heightened sense of future familial responsibilities may be less likely to engage in behaviors that could impede future plans (e.g., unprotected sex). Consistent with this view, there is preliminary evidence that self-reported family obligation values are associated with measures of neurocognitive activity believed to reflect greater cognitive control and planning (Telzer, Fuligni, Lieberman & Galvan, 2013).

To test the possibility that family obligation values act as a protective factor, we examine whether family obligation moderates the relationship between perceived peer engagement in sexual activity and substance use and adolescent's own engagement in these behaviors. We expected that adolescents who viewed these behaviors as more normative among their peers would report engaging in more risky behavior themselves, but that the magnitude of this relationship would diminish for youth who report high family obligation values. In other words, among youth who feel risky behaviors are more normative, those reporting strong family obligation values will be less likely to engage in such behaviors themselves.

Family obligation values as a vulnerability factor

The teenage years bring increased exposure to negative or potentially traumatizing life events. Adolescents of color and immigrant adolescents may be especially prone to these experiences because they more often live in low-income families and communities, where these events disproportionately occur (Evans & Kim, 2013). Experiencing negative life events or potentially traumatizing events is associated with greater depressive, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms, particularly among girls (Zona & Milan, 2012). There is, however, considerable variation in this link because many individual, family, and environmental characteristics contribute to differential vulnerability.

In previous studies, family obligation has been associated with positive indicators of family functioning (e.g., Telzer et al., 2014; Yau et al., 2009), and either unrelated or inversely related to emotional distress (Fuligni & Pederson, 2002; Juang & Cookston, 2009). Although these findings highlight the potential benefits of family obligation values, we hypothesized that family obligation can incur some cost to adolescent well-being based on studies of caregiving burden among low-income youth (e.g., Burton, 2007; McMahon & Luthar, 2007) and qualitative work with adolescent girls in this community (e.g., Hannay et al., 2013). Specifically, a strong sense of family obligation may, for some youth or at some times, become a source of stress rather than providing a sense of purpose or belonging. In particular, adolescents who feel strong family obligations and experience many negative life events, may have depleted psychological and coping resources, and thus develop more symptoms of emotional distress (e.g., allostatic overload or caregiving burden). In at least one study examining how family obligation interacts with other risk factors, higher family obligation was associated with worse outcomes when it occurred in the context of family conflict (Telzer et al., 2014). In this study, however, it was family obligation behaviors that increased risk; thus, it is unclear if family obligation values may act in the same way. In light of these findings, we examine whether family obligation values moderate the relationship between exposure to recent negative events and symptoms of depression and PTSD. We hypothesized that having high family obligation values would magnify the association between negative events and symptoms, such that adolescents endorsing strong family obligation values and many negative life events would report the most symptoms.

Current study

Family obligation is an important construct for understanding development among diverse adolescents. In this study, we examine whether family obligation values can act as both a protective and vulnerability factor in emotional and behavioral adjustment in a sample of 194 low-income adolescent girls, the majority of whom are racial/ethnic minorities or growing up in a first or second generation immigrant family. We focus specifically on girls because of the gendered nature of several areas of potential risk during adolescence (e.g., increased depressive symptoms, unplanned pregnancy) and because culturally rooted values about gender roles within the family (e.g., responsibilities to care for siblings) may be more salient during the teenage years. For youth from all backgrounds, adolescence involves physical maturation and increases in autonomy (Greenfield et al., 2003). These changes may trigger parents’ culturally rooted values regarding independent versus interdependent goals, and how these differ for boys versus girls (Chuang & Tamis-LeMonda, 2009).

First, we examine whether adolescents’ sense of family obligation relates to other measures of family relationships, including maternal warmth and hostility, relational style, communication, and parental monitoring using reports from adolescents and mothers. Based on existing research, we expected that family obligation would be correlated with other indicators of positive family functioning from adolescent and parental report. However, because the demographic makeup of this sample is distinct from other studies of family obligation, we first tested for these expected correlations. Second, we test whether family obligation values moderate associations between well-established risk factors and maladjustment. We hypothesized that high family obligation would act as a protective factor in the association between perceived peer risky behaviors and individual risky behavior (sexual activity and substance use), but as a vulnerability factor in the association between potentially traumatizing events (PTEs) and mental health symptoms (PTSD and depressive symptoms).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Study participants included 194 adolescent girls and their mothers (or primary female caretaker) residing in a mid-sized, low-income city in the Northeast US. In 92% of dyads, the caretaker was the biological mother. These families were participating in a larger NIH-funded study aimed at understanding the cultural and relational context of health disparities among adolescent girls. All adolescent girls entering 9th through 11th grade within the city were eligible for participation, with the average age at 15.4 years (SD=1.05; Range = 13-17). Fifty-eight percent of participants identified as Latina (primarily Puerto Rican), 26% as African-American/Black, and 16% as non-Hispanic, White. In 27% of families, at least one parent was born outside the U.S., and another 18% were born in Puerto Rico. Of the adolescents, 8% were born outside the U.S. and 11% in Puerto Rico. Thirty percent of homes included both biological parents at the time of participation. Educationally, 22% of mothers had not completed high school, 67% had a high school degree, and 11% had a bachelor's degree. The majority of adolescents (87%) qualified for free or reduced lunch at school. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic characteristics of the sample are consistent with public data about the city and high school demographics.

Participants were recruited from city schools, community centers, health centers, YWCA, local media outlets, and word-of-mouth. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish (20%) based on participant preference. Interviews were available in Polish to accommodate one of the largest immigrant groups in the area, although no mothers chose this option. When possible, measures were selected that have been validated with Spanish-speaking populations in previous studies. All measures were translated and backtranslated and then piloted with local residents in an iterative process, following recommendations by the World Health Organization. Mothers and daughters participated separately in a semi-structured interview, which was audiotaped and later transcribed verbatim, and then completed survey instruments privately using Audio Computer Assisted Survey Instruments (ACASI) programmed in their preferred language. Next, mothers and daughters participated in a videotaped dyadic interaction task. Interviews took approximately 2 hours, and participants were paid $40 each for their time. All procedures were approved by the University of Connecticut Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographic

Mothers provided detailed demographic information. Maternal education, marital status, receipt of public assistance housing, receipt of free/reduced lunch, and food insecurity were used to reflect socioeconomic differences. Mothers and daughters indicated all of the racial/ethnic groups they identified with, and mothers also reported on birth place for their daughter, themselves, and their parents. For the current purposes, the primary race/ethnicity selected by the daughter was used for analysis comparing racial/ethnic groups. However, because 12% of girls identified with more than one racial/ethnic group, all racial/ethnic comparisons were conducted using race/ethnicity as mutually exclusive groups and then with dummy coded variables that allowed for multiple racial/ethnic identifications to ensure consistent results.

Family obligation values

Family obligation values were assessed using 14 items from the Fuligni et al. (1999) family obligation measure reflecting attitudes about providing assistance (e.g., how often should you help take care of your brothers and sisters), respect for family (e.g., how important do you think it is to treat your parents with great respect), and future support (e.g., how important do you think it is to help your parents financially in the future). Items are responded to on a 1 to 5 scale, with higher scores reflecting stronger endorsement of the item. The three domains (current assistance, respect for family, future support) were initially derived from factor analysis (Fuligni et al., 1999). Previous studies including this measure have used either a total composite score (e.g., Telzer, Fuligni, Lieberman & Galván, 2013) or separate domain scores (e.g., Hardway & Fuligni, 2006) in analyses. In this study, we chose to use the total mean score for conceptual and empirical reasons. Conceptually, we believed that adolescents’ general sense of family obligation would be influential for the outcomes under investigation, but did not have reason to expect one domain to be particularly important. Empirically, a three factor model did not provide a good fit to data from this sample using CFA, χ2 = 162.49, df=74, CFI = .84, RMSEA = .08 (95% CI = .06-.09). The lack of fit resulted because several items loaded on different factors then initially conceptualized (e.g., future financial assistance was more strongly related with the respect for family factor than the future obligation factor). Consistent with a high alpha reliability coefficient for the total score (α = .85), a one-factor model with several correlated error terms provided a good fit to the data, χ2 = 95.31, df=66, CFI = .94, RMSEA = .05 (95% CI = .02-.07). Thus, a composite score (mean of all items) was used for analysis.

Maternal warmth and hostility

Adolescents reported on mother-daughter relationship quality using the Quality of Parental Relationships Inventory (Conger, Ge, Elder, Lorenz & Simons, 1994) as adapted for use by the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. The measure includes 17 items reflecting support/warmth (9 items, α = .92) and hostility (8 items, α = .83). Responses are on a 5-point scale with higher scores reflecting greater warmth or hostility.

Mother-daughter communication

Mothers and adolescents answered parallel items about the frequency of communication in seven areas, including school, college, jobs/career, friends, dating, sex, and substance use (adapted from Wills et al., 2003). Frequency items are on a 1-4 scale, with higher values reflecting more frequent communication. Mean scores for mothers (α = .75) and adolescents were used (α = .76) in analysis.

Parental monitoring

Mothers and adolescents answered parallel items from Stattin and Kerr (2000) widely used measure of parental monitoring, which assesses parental knowledge of the adolescent's whereabouts, activities, and associations from both the parent and adolescent perspective (e.g., “How much do your parents know what you do during your free time?”). Response scales range from 1 (nothing) to 5 (everything). In the current sample, alpha estimates for responses from mothers (6 items, α = .78) and adolescents (6 items, α = .80) were good.

Preoccupied and dismissive relationship style

Domains from the Behavioral Systems Questionnaire (BSQ; Furman & Wehner, 1999) were used to reflect adolescents’ preoccupied and dismissive relationship style with parents. The concept of relational styles is conceptually similar to adult attachment anxiety and avoidance in reflecting attitudes towards intimacy and closeness within close relationships. Preoccupation reflects overinvolvement and ongoing concerns about maintaining closeness; dismissiveness reflects avoidance of intimacy and minimization of the importance of relationships (Furman & Wehner, 1999). An example of a dismissing item is, “I rarely turn to my mother when upset”; an example of a preoccupied item is, “I get too wrapped up in my mother's worries”. In previous studies, these domains relate to mother and child reports of relationship characteristics in ways consistent with attachment theory (e.g., Branstetter, Fuman & Cottrell, 2009), with higher scores increasing the risk for psychopathology (e.g., Milan, Zona & Snow, 2013). Adolescents responded separately for maternal preoccupation (5 items, α = .69), paternal preoccupation (5 items, α =.72), maternal dismissiveness (5 items, α = .68), and paternal dismissiveness (5 items, α = .74). Higher scores reflect more preoccupation and dismissiveness.

Perceived peer engagement in risky behavior

Adolescents were asked to report how common they believed certain behaviors were of other youth their age in the school and community using a 1-5 response scale with a visual percentage analog. Responses on the 1-5 scale reflect increasing, equal percentages (e.g., 0-20%, 21-40%). They were asked the items separately for males and females. For the current purposes, female peer involvement in regular alcohol consumption and sexual activity (oral and vaginal sex average) were used separately as measures of perceived peer behavior in each domain.

Negative life events

Adolescents were asked to indicate whether they had experienced ten events (e.g., witnessing an assault, being in a serious accident) selected from several PTSD Criterion A events list (e.g. Foa et al., 2001; Ford et a., 2000). Events deemed very uncommon in this population (e.g., exposure to war) were eliminated. For each item, adolescents reported whether the event had ever occurred to them and, if so, if it happened in the last year. A total count of events in the last year was used to reflect recent exposure to negative life events.

Individual risky behavior

Adolescents were asked five yes/no questions about sexual activity from the Student Health Questionnaire (Coyle et al., 2004) and six yes/no questions about sexual activity and substance use from the CDC Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBS; Eaton et al., 2011). Sexual items asked whether the adolescent had yet engaged in specific acts (e.g. vaginal sex) and about sexual history (e.g., number of partners). For the current purposes, a count of nine potentially risky sexual activities (e.g., performed oral sex, sex without protection, sex with more than one partner) was computed, with higher scores reflecting more sexual activity. One yes/no item from the YRBS, drinking alcohol in the last 30 days, was used as an indicator of recent substance use.

Mental health

Adolescents completed the 17-item Child Post Traumatic Stress Symptoms (PTSS; Foa, Johnson, Feeny & Treadwell, 2001) and the Adolescent Psychopathology Scale-Short Form Major Depression subscale (APS; Reynolds, 2000). The PTSS is a widely used measure that includes all PTSD symptoms based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Responses are on a 5 point likert scale, with higher scores reflecting more frequent symptoms. Chronbach alpha for this sample was high (α=.85). On the APS, the Major Depression subscale includes twelve items that evaluate depressive symptoms based on DSM IV. The measure uses a 3-point Likert scale with scores ranging from (1) “almost never” to (3) “nearly every day” over the last two weeks. Chronbach alpha was high (α=.89).

Data Analytic Plan

Data were first checked for normality using graphical and univariate approaches. Correlation analyses were used to examine bivariate associations. Tests of moderation were conducting following recommendations and macros by Hayes (2013). This approach includes post hoc probing of simple slopes of proposed by Aiken and West (1991), but tests of statistical significance are conducted with heteroscedasticity-consistent standard error terms, a more appropriate approach in OLS regression (Hayes, 2013).

Results

On average, adolescents reported moderate to high level of family obligation values (FO Mean = 3.42, SD =.61, Scale Range = 1-5). FO was not significantly correlated with demographic factors, including age (r = .05), maternal education (r = −.12), public housing (r = .03), free lunch status (r = .12) or generational status (r = .02). Family obligation did differ by race/ethnicity (F(2,190) = 3.78, p < .05), with higher mean scores for Latina (Mean=3.59, SD=.59), compared to African-American/Black (Mean=3.29, SD=.69) or White (Mean = 3.28, SD=.55) adolescents. Race/ethnicity was controlled for in subsequent analyses.

Partial correlations were run to examine associations between family obligation and other commonly measured domains of family functioning, controlling for ethnicity. Family obligation was significantly correlated with adolescent reports of maternal warmth (r = .33, p < .01) and hostility (r =−.17, p < .05), maternal reports of communication (r = .20, p < .01) and monitoring (r = .22, p < .01), adolescent reports of communication (r = .27, p < .01) and monitoring (r = .35, p < .01), and adolescent reports of maternal relational preoccupation (r = .25, p < .05), paternal relational preoccupation (r = .20, p < .05), maternal relational dismissiveness (r =−.27, p < .01), and paternal relational dismissiveness (r = −.30, p < .01). For most variables, higher FO was associated with what is generally considered better family functioning, including greater warmth, less hostility, more communication, more monitoring, and less relational dismissiveness. The one exception to this pattern was that higher FO was associated with a more preoccupied relational style with parents, which has been considered a risk factor (e.g., Milan et al., 2013).

Table 1 presents bivariate correlations between family obligation and the risk factors (perceived peer engagement in risky behavior, negative life events) and adjustment indicators (sexual activity, recent substance use, depressive symptoms, PTSD symptoms) used in subsequent moderation analysis. As expected, perceptions of peer norms were positively correlated with individual risky behaviors in respective domains, and negative life events were positive correlated with depressive and PTSD symptoms (i.e., the expected relations between established risk factors and adjustment indicators). Across the sample, the average score on the sexual risk behavior scale was 1.4 (Range 0-7, SD=2.18), with 28% of girls indicating they were sexually active (i.e., engaging in vaginal sex in the last year). Twenty-one percent reported recent drinking in the last month, and 54% reported ever drinking. On mental health indicators, 11% of girls were above the recommended clinical cutoff on the depressive symptom scale (Mean = 7.3, SD = 5.6) and 16% reported sufficient criteria for PTSD diagnosis on the PTSS scale (Mean = 13.93, SD = 11.9). As shown, FO was not associated with most risk factors or adjustment indicators at the bivariate level. In other words, there was little evidence that adolescent girls who reported greater family obligation were exposed to fewer risk factors or had better behavioral or emotional adjustment overall.

Table 1.

Correlations between family obligation values, risk factors, and adjustment indicators

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family obligation values | .11 | .08 | −.04 | −.14* | .01 | −.06 | −.10 |

| 2. Peer alcohol use norms | -- | .41** | .10 | .13* | .17** | .04 | .03 |

| 3. Peer sex norms | -- | .11 | .09 | .25** | .13 | .12 | |

| 4. Recent negative life events | -- | .21** | .18* | .33** | .44** | ||

| 5. Individual recent alcohol use | -- | .36** | .12* | .20** | |||

| 6. Individual sexual risk behavior | -- | .11 | .14* | ||||

| 7. Depressive symptoms | -- | .69** | |||||

| 8. PTSD symptoms | -- |

p<.05

p<.01

Note: Analyses controlled for race/ethnicity

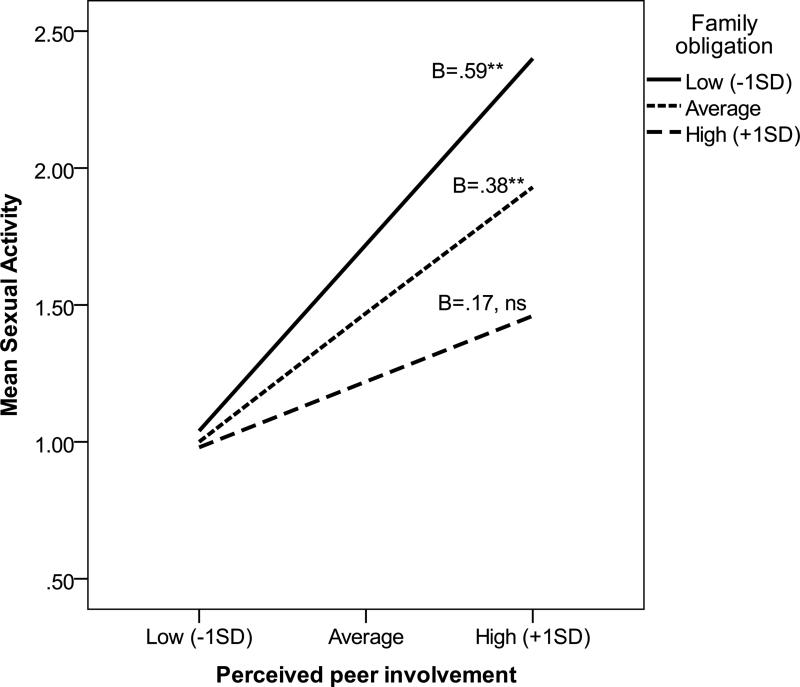

Next, hierarchical linear (for sexual activity) and logistic (for recent alcohol use) regressions were used to test hypotheses that family obligation acts as a protective factor in the relationship between perceived peer norms for sexual activity or substance use and adolescent's individual engagement in the same behavior. As shown in Table 2, the interaction between perceived peer engagement and family obligation on individual risky behavior was significant for both outcomes. Figure 1 presents follow-up post hoc probing for sexual activity. As shown, perceived peer involvement in sexual activity predicted adolescent sexual risk behavior for youth reporting low (B = .59, p < .01) or moderate (B = .38, p < .01) FO, but not for those high in FO (B = .17, p = .20). A very similar pattern emerged for substance use, with perceived peer use predicting individual drinking only at low levels of family obligation. Unstandardized beta coefficients for adolescents at low, moderate, and high FO were B = .70, p < .05, B = .27, p = .18, B = −.15, p = .59, respectively. Among those who believed that over half of their peers were involved in regular drinking, 29% of those with low FO had engaged in recent drinking themselves compared to 16% of those with high FO. These findings indicate that the magnitude of the relationship between perceptions of peer risky behaviors and individual engagement in those behaviors depends on levels of family obligation. In particular, although FO is not associated with perceptions of peer norms, it may diminish the effect of these perceptions of individual risky behavior.

Table 2.

Hierarchical regressions predicting individual risk behavior from family obligation values and peer norms

| Outcome = Sexual Risk | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor: | B (SE) | F | R2 |

| Age | .80 (.12)** | ||

| Latina ethnicity | −.32 (.32) | ||

| Peer norms for sex | .41 (.13)** | ||

| Family obligation values | −.41 (.21)* | ||

| Peer norms × family obligation | −.33 (.16)* | ||

| Overall Model | 8.38** | .25 | |

| Outcome = Alcohol Use | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor: | B (SE) | χ 2 | Nagelkrk R2 |

| Age | .12 (.18) | ||

| Latina ethnicity | −.43 (.38) | ||

| Peer norms for substance use | .28 (.21) | ||

| Family obligation values | −.52 (.31) | ||

| Peer norms × family obligation | −.70 (.36)* | ||

| Overall Model | 11.25* | .09 | |

p<.05

p<.01

Figure 1.

Relation between perceived norms and individual sexual behavior for adolescents with low, moderate, or high levels of family obligation values

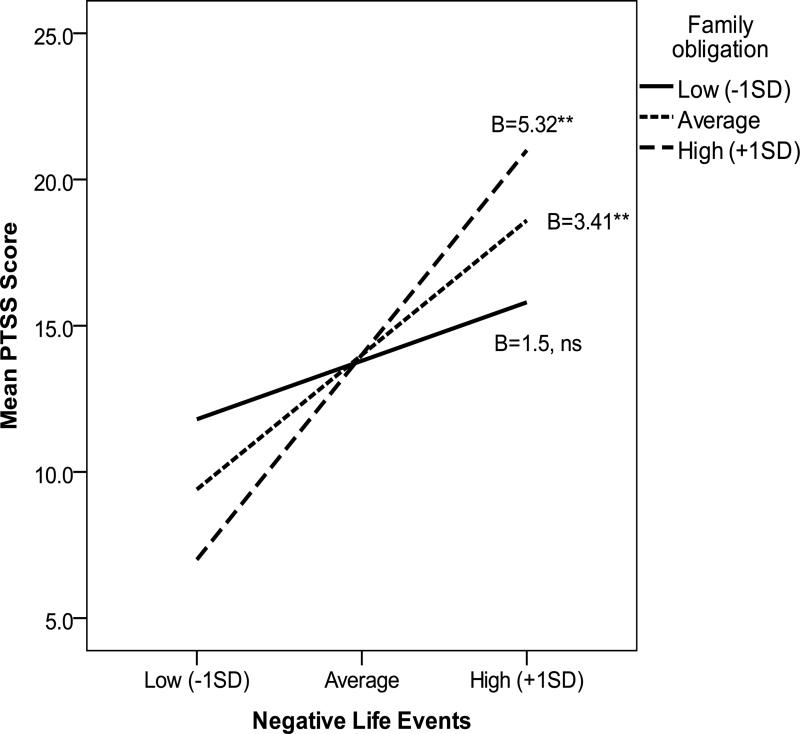

A similar approach was used to test whether family obligation values moderate the association between negative life events and mental health symptoms. As shown in Table 3, the interaction between negative life events and FO was a significant predictor of both PTSD and depressive symptoms. Follow-up post hoc probing of simple slopes for PTSD symptoms is graphed in Figure 2. Unstandardized beta coefficients for adolescents at low, moderate, and high FO were B = 1.50, p =.19, B = 3.41, p < .01, B = 5.32, p <.01, respectively. The same pattern emerged in post hoc probing of depressive symptoms (not graphed), with the strongest relationship between negative events and depressive symptoms for those at high levels of FO (B = 2.28, p < .01), a smaller but statistically significant effect at moderate FO (B = 1.34, p < .01) and no significant relationship at low levels of FO (B = .48, p = .30). Across both mental health outcomes, FO moderated the relationship between negative life events and symptoms, such that girls with the highest level of family obligation and the most negative life events reported the most distress.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regressions predicting mental health from negative events in the last year and family obligation values

| Outcome = Depressive symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor: | B (SE) | F | R2 |

| Age | −.03 (.05) | ||

| Latina ethnicity | −.03 (.10) | ||

| Negative events in the last year | 1.34 (.30)** | ||

| Family obligation values | −.45 (.59) | ||

| Negative events x family obligation | 1.40 (.50)** | ||

| Overall Model | 7.14** | .16 | |

| Outcome = PTSD symptoms | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| B (SE) | F | R2 | |

| Age | −.02 (.03) | ||

| Latina ethnicity | −.03 (.06) | ||

| Negative events in the last year | 3.41 (.63)** | ||

| Family obligation values | .22 (1.4) | ||

| Negative events x family obligation | 3.10 (1.15)** | ||

| Overall Model | 8.86** | .21 | |

* p<.05

p<.01

Figure 2.

Relationship between recent negative life events and PTSD symptoms for adolescents with low, moderate, or high levels of family obligation values

As a follow-up analysis, we reran the above tests of moderating effects controlling for correlated family functioning indicators. The results remained significant. We also tested whether any family factors acted similarly to FO in moderating relations between risk factors and adjustment. None of the interactions were significant. These findings suggest that the role of family obligation values is distinct from other correlated measures of family functioning.

Discussion

The changing face of America requires that adolescent researchers seek to understand similarities and differences in the development of diverse youth. The work of Fuligni and colleagues (1999) has highlighted the importance of understanding family obligation in this effort. The results from this study suggest that family obligation values may play a complex role in the adjustment of adolescent girls, with implications depending on other risk factors and the type of outcome under investigation.

Family obligation values were not related to most indicators of socioeconomic and demographic differences in this sample, with the exception of race/ethnicity. As has been found in other studies, Latinas in this sample reported higher family obligation values than their White or African-American/Black peers (Tseng, 2004). These findings are consistent with the view that interdependence and relatedness may be particularly salient values infused into daily life among Latino families (Halgunseth, Ipsa & Rudy, 2007). In contrast to other studies (e.g., Tseng, 2004), we did not find differences in family obligation values by nativity or generational level. One difference in this study is that the largest group of participants identified as Puerto Rican. Although not considered immigrants, Puerto Ricans may share similar culturally rooted values or experiences as many of the first and second- generation immigrant families within this sample. Given the unique status of Puerto Rico as an American commonwealth, measures of generational status and nativity may not adequately capture important within-group differences in acculturation, particularly in Northeastern cities where mobility between the mainland and island is common.

Family obligation values were associated with several indicators of family functioning, as has been reported in other studies. Our findings expand previous research by including parental report of relationship characteristics, and by including domains that are particularly salient in the teenage years (e.g., parent-adolescent communication, parental monitoring). Although the pattern of correlations indicates that higher family obligation values occur with other indicators of “positive” family functioning, there was one exception: higher family obligation was associated with more preoccupation with maternal and paternal relationships. In the adult attachment style literature, preoccupation reflects relational overinvolvement and insecurity, and thus is generally viewed in a negative way. Consistent with the view, studies of adolescent preoccupation with parental relationships using the same measure have found higher preoccupation predicts negative outcomes (e.g., Milan et al., 2013). Most of this research is based on middle-class, White families, however. Plausibly, greater preoccupation may have a different meaning among youth of color or from immigrant families. As has been highlighted in research on Latino families, it is important not to pathologize a seemingly high level of parental involvement without understanding the functional meaning and implications of these behaviors (e.g., parental control; Halgunseth et al., 2007). Among Latina adolescents, high family obligation values may co-occur with factors such as parental preoccupation that reflect relational insecurity in other populations, without having the same meaning.

Family obligation values were not directly associated with risk factors (peer norms, negative life events) or most measures of behavioral or emotional adjustment (sexual activity, substance use, PTSD, or depressive symptoms), with the exception of a small negative correlation with recent alcohol use. Thus, our results do not support the notion that a sense of strong family obligation values is a marker of a generally less risky environment or better overall adjustment. Rather, its meaning may depend on the presence of other risk factors and the type of outcome under investigation. As elaborated below, family obligation may simultaneously act as both a protective and vulnerability factor among teenage girls.

High family obligation values diminished the strength of the relationship between perceptions of peer norms for risky behavior and adolescents own involvement in these activities. Across the sample, over half of adolescents rated peer alcohol use and sexual activity as normative (i.e., occurring in at least 50% of peers). Adolescents who reported high family obligation values did not differ in how they perceived peer norms compared to other adolescents, suggesting that they were not judging peer norms differently or using a different set of peers as a reference. However, believing peer alcohol use or sexual activity was common was associated with more individual drinking or sexual activity for girls at low or moderate levels of family obligation values but not those at high levels. Teenage girls who report high family obligation values may be “protected” from peer risk factors in several ways. For example, adolescents who feel greater respect towards adult family members may be less concerned with the opinions and behaviors of peers, or may implicitly or explicitly use beliefs about parental reactions (e.g., anger or disappointment) to deal with any felt peer pressure. Although we did not measure actual family obligation behaviors, it is also possible that adolescents who report feeling responsible to assist family members may have less actual time to spend with peers. More broadly, the potential effect of risky behavior on family members or family responsibilities may be more salient for adolescent girls who report high family obligation values, and thus play a larger role in their decision-making about these behaviors.

Although family obligation may have benefits to the individual and family, we hypothesized that it can incur some cost to adolescent well-being in certain circumstances. Consistent with this possibility, we found that endorsing strong family obligation values increased, rather than decreased, the relationship between negative life events and mental health indicators. Adolescent girls with high family obligation values and many recent negative events were the most symptomatic, while adolescents with high family obligation values and low negative life events reported the fewest symptoms. It is important to again note that there was no bivariate association between family obligation values and mental health symptoms; that is, higher family obligation was not consistently associated with better or worse mental health across the sample. The subjective meaning of family obligation may therefore depend on other stressors. For adolescent girls who experience few negative life events, high family obligation values may provide a sense of belonging, significance, and connection to others. In contrast, for adolescent girls who experience many negative events, high family obligation values could contribute to feelings of stress or burden.

Given the intersectionality of race/ethnicity, gender, and SES, adolescent girls like the ones participating in this study often have multiple responsibilities (e.g., working part time to earn money, caring for younger siblings, helping with household chores) and feel strong affiliation commitments (e.g., providing emotional support to a parent, meeting parents academic expectations). Thus, they may be especially prone to becoming overwhelmed when other life events occur. Adolescent girls who have experienced recent negative events also may be less able to fulfill certain family obligations they value, which in turn could contribute to poorer mental health by affecting their sense of purpose and relational worth. Because this study is cross-sectional, it is also possible that increased family obligation is a response to specific types of negative life events that affect the family, such as an increased desire to financially help a parent in the future after witnessing domestic violence. In this case, increases in feelings of family obligation and mental health symptoms may both be reactions to family stressors.

Clinical and practice implications

Given the complex but important role of the family context in adolescent development, researchers and practitioners who work with diverse youth must be thoughtful in how to incorporate family obligation into prevention and intervention. The goal should be to enhance positive aspects of family obligation while decreasing any potential negative aspects. In prevention programs aimed at decreasing risky sexual activity and substance use, for example, this may involve making explicit connections between the potential impact of risk behavior on family members, family responsibilities, and future obligations. Often times, substance use and pregnancy/STD prevention programs focus on the risk to individual health. Many of these programs are based on health behavior theories that emphasize the individual; however, there is growing evidence that health interventions for low-income females may be most beneficial when they are relationally focused (Logan, Cole & Leukefeld, 2002). Further, it is important to incorporate awareness of family obligation in program planning, for example by allowing for flexibility in attendance because of familial responsibilities and incorporating important family members when possible (Hannay et al., 2013).

It also may be beneficial for those who work with adolescents and families to directly address family obligation during times of greater stress. This could be achieved by more consideration of family systems within programs that target low-income adults (e.g., providing childcare for the younger children of mothers in treatment or work promotion programs so as to reduce adolescent caregiving responsibilities). In mental health settings, this may involve dyadic or family sessions addressing adolescent girls’ perceptions of familial obligation during times of heightened stress, while ensuring pragmatic family needs are met. Although there have been efforts to understand how certain cultural values impact mental health (e.g. Cespedes & Huey, 2008), less work has been done to determine how these constructs can be effectively incorporated into culturally tailored intervention efforts.

Study limitations and strengths

The findings from this study should be understood in the context of study limitations. First, this study is cross-sectional, which limits how tests of protective and vulnerability factors can be examined. In particular, it is not possible to establish temporal precedence or how processes might unfold over time. Second, we examined family obligation values as reported by adolescents, and therefore do not know how well this matches parental expectations and beliefs. Adolescent and parent agreement on many domains is moderate at best. Finally, this study focused exclusively on adolescent girls. Given gender differences in many aspects of adolescent development, it is important for researchers to consider the intersectionality of gender with race, ethnicity, and immigration status on family obligation values and behaviors. In previous research, gender differences in familial obligations have been found in some samples but not others; consequently, studies that can make direct comparisons of whether family obligation values interact with risk factors in similar ways for adolescent boys and girls are needed. Similarly, because of the limited sample size, we cannot examine differences within racial, ethnic, or generational group. Although the pattern of correlations between family obligation values and other variables within each racial/ethnic group were very similar, we did not have the power to formally examine important within-group variability.

Despite these shortcomings, there are several strengths to this study. In particular, we have extended the study of family obligation to a different population, included relationship measures from the perspective of mothers and daughters, and collected data on multiple outcomes. Perhaps most importantly, this study links family obligation values to the domains in which low-income adolescent girls and young women are at elevated risk (e.g., trauma and depressive symptoms, risky sexual activity), and thus can inform targeted intervention efforts.

Conclusions

Despite a rich literature on how cultural variations in interdependence values may shape family life and child development, empirical tests of how relevant constructs operate are still rather limited (Greenfield et al., 2003). Our results suggest that family obligation values are correlated with other, widely studied aspects of family relationships (e.g., maternal warmth), yet may have a distinct and more nuanced role in the emotional and behavioral adjustment of adolescent girls. In particular, having a strong sense of obligation towards family members may be simultaneously beneficial and harmful, depending on other risk factors in girls’ lives. Although we did not investigate underlying mechanisms, our findings coupled with existing research highlight how and when these values may be influential. Specifically, family obligation values may diminish the potential impact of risk factors in the peer domain by influencing decision-making processes about risky behaviors (e.g., Telzer et al., 2013). At the same time, feeling strong obligations and responsibilities towards family members may contribute to depleted psychological resources when adolescent girls are exposed to multiple negative events (e.g., McMahon & Luthar, 2007). These findings build on a larger body of research documenting that family obligation values differ by race, ethnicity, and immigration status among American adolescents (Fuligni et al., 1999). In an increasingly multicultural society, studying when and how family obligation values are influential can enhance our understanding of the different ways adolescents navigate the challenges of this developmental period, and contribute to efforts to promote the well-being of youth from diverse backgrounds.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with support from National Institute of Health (NICHD R21HDO65185) to the lead author. Several research assistants and community collaborators gave invaluable assistance, particularly Kate Zona, Viana Turcios-Cotto, and Jenna Acker.

Biography

Stephanie Milan is an Associate Professor within the Clinical Division of the Department of Psychology at University of Connecticut. She received her Ph.D. from Vanderbilt University. Her research focuses on developmental psychopathology in the context of economic disadvantage, and specifically the cultural and relational context of disparities in the physical and mental health of adolescent girls.

Sanne Wortel is a graduate student in Clinical Psychology at the University of Connecticut-Department of Psychology. She received her B.A. from Ithaca University. Her research and clinical interests focus on high risk adolescent girls, and particularly the links between sexual development and mental health in this population.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: SM conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, oversaw analysis, and drafted the manuscript; SW participated in the conceptualization of the paper, statistical analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett J. Adolescence and emerging adulthood: 4th Edition. Pearson Publishers; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Branstetter S, Furman W, Cottrell L. The influence of representations of attachment, maternal–adolescent relationship quality, and maternal monitoring on adolescent substance use: A 2-year longitudinal examination. Child Development. 2009;80:1448–1462. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01344.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton L. Childhood adultification in economically disadvantaged families: A conceptual model. Family Relations. 2007;56:329–345. [Google Scholar]

- Cespedes Y, Huey S. Depression in Latino adolescents: A cultural discrepancy perspective. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:168–172. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SS, Tamis-LeMonda C. Gender roles in immigrant families: Parenting views, practices, and child development. Sex Roles. 2009;60:451–455. [Google Scholar]

- Conger R, Ge X, Elder G, Lorenz F, Simons R. Economic stress, cooercie family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development. 1994;65:541–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle K, Kirby D, Marín B, Gómez C, Gregorich S. Draw the Line/Respect the Line: A randomized trial of a middle school intervention to reduce sexual risk behaviors. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:843–851. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries. 61:1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards CP, Knocke L, Aukrusk V, Kumru A, Kim M. Parental ethnotheories of child development: Looking beyond independence and individualism in American belief systems. In: Kim, Yang, Hwang, editors. Indigenous and Cultural Psychology: Understanding People in Context. Springer Publishers; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Evans G, Kim P. Childhood poverty, chornic stress, self-regulation, and coping. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7:43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Foa E, Johnson K, Feeny N, Treadwell K. The child PTSD symptom scale (CPSS): A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:376–384. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3003_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Racusin R, Ellis CG, Daviss WB, Reiser J, Fleischer A, et al. Child maltreatment, other trauma exposure, and posttraumatic symptomatology among children with ODD and ADHD. Child Maltreatment. 2000;5:205–218. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005003001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey W. Analysis of US Census Bureau population projections. Brookings Institute; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ, Tseng V, Lam M. Attitudes toward family obligations among American adolescents with Asian, Latin American, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 1999;70(4):1030–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. Family obligation, college enrollment, and emerging adulthood in Asian and Latin American families. Child Development Perspectives. 2007;1:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Wehner E. The Behavioral Systems Questionnaire-Revised. The Behavioral Systems Questionnaire-Revised. University of Denver; 1999. Unpublished document. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield P, Keller H, Fuligni A, Maynard A. Cultural pathways through universal development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:461–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halgunseth L, Ispa J, Rudy D. Parental control in Latino families: An integrated review of the literature. Child Development. 2006;77:1282–1297. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00934.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannay J, Dudley R, Milan S, Leibovitz P. Combining photovoice and focus groups: Engaging Latina teens in community assessment. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44:215–224. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardway C, Fuligni AJ. Dimensions of family connectedness among adolescents with Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(6):1246–1258. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional processes: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D. Cultural and contextual correlates of obligation to family and community among urban Black and Latino adults. In: Rossi AS, editor. Caring and doing for other: Social responsibility in the domains of family, work, and community. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL US: 2001. pp. 179–224. [Google Scholar]

- Juang LP, Cookston JT. A longitudinal study of family obligation and depressive symptoms among Chinese American adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(3):396–404. doi: 10.1037/a0015814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang L, Andrews K, Stein GL, Supple AJ, Gonzalez LM. Socioeconomic stress and academic adjustment among asian american adolescents: The protective role of family obligation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013;42:837–847. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9916-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan T, Cole J, Leukefeld C. Women, sex, and HIV: Social and contextual factors, meta analysis of published interventions, and implications for practice and research. Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:851–885. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon T, Luthar S. Defining characteristics and potential consequences of caretaking burden among children living in poverty. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:267–281. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan S, Zona K, Snow S. Pathways to adolescent internalizing: Early attachment insecurity as a lasting source of vulnerability. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42:371–383. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.736357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Adolescent Psychopathology Scale- Short Form Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Lutz, FL: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stein C. Ties that bind: three studies of obligation in adult relationships with family. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1992;9:25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sy S, Brittian A. The impact of family obligations on young women's decisions during the transition to college: A comparison of Latina, European American, and Asian American students. Sex Roles. 2008;58:729–737. [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Fuligni AJ, Lieberman MD, Galván A. Meaningful family relationships: Neurocognitive buffers of adolescent risk taking. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2013;25(3):374–387. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, Gonzales N, Fuligni AJ. Family obligation values and family assistance behaviors: Protective and risk factors for Mexican–American adolescents’ substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43:270–283. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9941-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng V. Family interdependence and academic adjustment in college youth from immigrant and U.S. born families. Child Development. 2004;75:966–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills T, Gibbons F, Gerrard M, Murry V, Brody G. Family communication and religiosity related to substance use and sexual behavior in early adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:312–320. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D, Jaffe P, Crooks C. Adolescent risk behaviors: Why teens experiment and strategies to keep them safe. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yau J, Taspoulos-Chan M, Smetana J. Discloure to parents about everyday activities among American adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Child Development. 2009;80:1481–1498. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zona K, Milan S. Gender differences in the longitudinal impact of exposure to violence on mental health in urban youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:1674–1690. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9649-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]