Abstract

Background

Norepinephrine (NE) is one of the primary catecholamines of the sympathetic nervous system released during a stress response and plays an important role in modulating immune function. NE binds to the adrenergic receptors on immune cells, including T cells, resulting in either suppressed or enhanced function depending on the type of cell, activation status of the cell, duration of NE exposure and concentration of NE. Here, we aim to analyze the effects of NE on the functionality of naïve (Tn), central memory (Tcm) and effector memory (Tem) CD8 T cells.

Methods

We isolated CD8 T cell subsets from healthy human adults and treated cells in vitro with NE (1×10−6 M) for 16 hours; we then stimulated NE treated and untreated CD8 T cell subsets with antibodies for CD3 and CD28 for 24 and 72 hours. We assessed the level of beta-2 adrenergic receptor (ADRB2) expression in these cells as well as global gene expression changes in NE treated Tcm cells by microarray analysis. Altered expressed genes after NE treatment were identified and further confirmed by RT-qPCR, and by ELISA for protein changes. We further determined whether the observed NE effects on memory CD8 T cells are mediated by ADRB2 using specific adrenergic receptor agonist and antagonists. Finally, we examined the levels of mRNA and protein of the NE-induced genes in healthy adults with high serum levels of NE (>150 pg/mL) compared to low levels (<150 pg/mL).

Results

We found that memory (Tcm and Tem) CD8 T cells expressed a significantly higher level of ADRB2 compared to naïve cells. Consequently, memory CD8 T cells were significantly more sensitive than naïve cells to NE induced changes in gene expressions in vitro. Global gene expression analysis revealed that NE induced an elevated expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in resting and activated memory CD8 T cells in addition to a reduced expression of growth-related cytokines. The effects of NE on memory CD8 T cells were primarily mediated by ADRB2 as confirmed by the adrenergic receptor agonist and antagonist assays. Finally, individuals with high serum levels of NE had similar elevated gene expressions observed in vitro compared to the low NE group.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that NE preferentially modulates the functions of memory CD8 T cells by inducing inflammatory cytokine production and reducing activation-induced memory CD8 T cell expansion.

Keywords: norepinephrine, CD8 T cells, stress, inflammation

1. Introduction

A growing body of evidence indicates that the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) modulates functions of the immune system (Elenkov, Wilder, Chrousos, and Vizi, 2000; Kin and Sanders, 2006; Sanders and Straub, 2002). This nervous-immune communication is illustrated during a stress response as the SNS releases catecholamines, such as norepinephrine (NE), which interact with surface receptors on lymphocytes and modulate their functions (Khan, Sansoni, Silverman, Engleman, and Melmon, 1986; Kohm and Sanders, 2000; Sanders, 2012). Chronic stress has detrimental effects on the immune system and to some degree resembles the immune changes seen in aging (Gouin, Hantsoo, and Kiecolt-Glaser, 2008; Hu, Wan, Chen, Caudle, LeSage, Li, and Yin, 2014; Kiecolt-Glaser, Glaser, Gravenstein, Malarkey, and Sheridan, 1996).

NE is the primary catecholamine released by the SNS and has been previously found to significantly impact lymphocytes, including T cells, natural killer (NK) cells and B cells (Kin et al., 2006; Kohm and Sanders, 2001; Lang, Drell, Niggemann, Zanker, and Entschladen, 2003; Sanders et al., 2002; Wahle, Hanefeld, Brunn, Straub, Wagner, Krause, Hantzschel, and Baerwald, 2006). The effect of NE on immune cells appears complex as NE can have either a stimulatory or inhibitory effect depending on the type of immune cell, activation status of the cell, duration of exposure, and dosage (Kalinichenko, Mokyr, Graf, Jr., Cohen, and Chambers, 1999; Kin et al., 2006; Kohm et al., 2001; Levite, 2000). For example, NE simulates the migratory activity of naïve CD8 T cells but inhibits the migration of activated CD8 T cells (Strell, Sievers, Bastian, Lang, Niggemann, Zanker, and Entschladen, 2009). Furthermore, NE exposure reduces IL-2 production and upregulates chemokine receptors such as CXCR1 and CXCR2 during CD8 T cell activation (Strell et al., 2009).

CD8 T cells are a heterogeneous population consisting of naïve (Tn) cells and two major memory cell populations: central memory (Tcm), which provide a memory reservoir for the rapid response to stimulation, and effector memory (Tem), which provide immediate effector functions and protective immunity (Sallusto, Geginat, and Lanzavecchia, 2004). It is unknown if the effect of NE is similar or different across the CD8 T cell subsets (Tn, Tcm and Tem), which may have in different implications on one’s overall immune function.

NE binds to the adrenergic receptors expressed on the surface of a variety of immune cells. The beta-2 adrenergic receptor (ADRB2) is believed to be the primary receptor on T and B cells through which NE directly modulates cellular activity (Padgett and Glaser, 2003; Sanders, 2012; Sanders, Kasprowicz, Swanson-Mungerson, Podojil, and Kohm, 2003; Sanders et al., 2002). Signaling through the ADRB2 on lymphocytes is one way the nervous system regulates the immune system (Nakai, Hayano, Furuta, Noda, and Suzuki, 2014). Previous studies have shown the heterogeneous expression of the ADRB2 within peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (Anstead, Hunt, Carlson, and Burki, 1998; Khan et al., 1986; Van Tits, Michel, Grosse-Wilde, Happel, Eigler, Soliman, and Brodde, 1990), as well as the expression of the ADRB2 on Th1 cells but not on Th2 CD4 T cells (Kohm et al., 2001; Ramer-Quinn, Baker, and Sanders, 1997; Sanders, 2012). However, it is unknown whether the expression of the ADRB2 is also heterogeneous within CD8 T cell subsets (Tn, Tcm, and Tem), or if NE signals mainly through the ADRB2 on CD8 T cells.

To determine whether NE has a similar or different effect on CD8 T cell subsets and to identify the specific changes that occur in CD8 T cells, we compared the ADRB2 expression on CD8 T cell subsets (Tn, Tcm and Tem cells) of healthy human donors. In addition, we examined the consequences of NE exposure on isolated CD8 T cell subsets’ gene expressions and corresponding protein levels, as well as functional changes. To verify these changes were a result of NE binding with the ADRB2, we isolated ADRB2 positive and negative memory CD8 T cells to examine the impact of NE on cytokine gene expression. We also utilized adrenergic receptor agonist and antagonists to determine if the NE effect on gene expression changes in memory CD8 T cells are mediated by ADRB2. Finally, we examined this phenomenon in adults with either high or low levels of NE in their serum by measuring changes in gene expressions and intracellular cytokines of memory CD8 T cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Human subjects and blood collection

Peripheral blood was collected at the clinic of the National Institute on Aging (NIA), National Institutes of Health (NIH) from healthy adult donors (N=63) (Supplementary Table 1). PBMCs were isolated from the blood and used for the experiment immediately or stored at −80°C for later experimental use. To examine potential differences in individuals with either high or low levels of NE, we utilized frozen PBMCs from an investigation at the NIH Clinical Center examining physiological changes in family caregivers compared to age-, gender- and ethnicity-matched normal volunteers (N=32) (Supplementary Table 2) under an Internal Review Board approved protocol at the NIH.

2.2 Flow cytometry analysis

For the ADRB2 cell surface staining, freshly isolated PBMCs were incubated with either an unlabeled monoclonal antibody against ADRB2 (Abnova) followed by a secondary goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with FITC, or by using the same anti-ADRB2 mAb by custom conjugation with PerCP/Cy5.5 using a kit (Lightning-Link, Innova Biosciences) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. When the secondary goat anti-mouse IgG was used, a non-specific mouse IgG was used as a control. Other antibodies used for flow cytometry staining included CD8a (APC), CD45RA (PE) and CD62L (FITC) (Biolegend). Samples were analyzed on the BD Accuri™ C6 Flow Cytometer. An example of the flow cytometry staining and gating strategy can be found in Supplementary Fig. 1.

For intracellular cytokine staining, frozen PBMCs were thawed and incubated for 3 hours in an incubator containing 5% O2. Next, PMA (50ng/mL, Sigma), Ionomycin (80ng/mL, EMD), and a Golgi Blocker (Monensin, 1 μg/million cells, BD Biosciences) were added to the cells and incubated for 4 hours. Cells were stained with a viability dye (e506) and antibodies, including CD8 (PeCy7), CD4 (Pacific Blue), CD3 (ApcCy7), CD28 (APC), CD45RA (FITC) and isotype matching control antibodies from Biolegend and ADRB2 (PerCP/Cy5.5) from Abnova. Cells were washed and then 0.5 ml of fixation buffer (Biolegend) was added for overnight incubation at 4°C in the dark. The next day, cells were washed with 1 ml permealization buffer (Biolegend). Intracellular staining for IL-1A (PE) and TNF (PerCP/Cy5.5) from Biolegend were completed in one tube, and IL-2 (PerCP/Cy5.5, Biolegend) and CCL-2 (PE, eBioscience) in a separate tube. Isotype and fluorescent dye matched non-specific mouse IgG were used as controls for cytokine staining. Samples were collected on the Canto II Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). Data and mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) were further analyzed using FloJo V10 software.

We used an antibody against Annexin V and a DNA binding dye, 7-AAD (Biolegend), staining to assess cell death and apoptosis at 24 and 72 hours after activation. Samples were analyzed on the BD Accuri™ C6 Flow Cytometer, as previously described.

2.3 Isolation and culture of human CD8 T cell subsets from adults with NE

The procedure for isolating naïve and memory CD8 T cells was described previously (Araki, Wang, Zang, Wood, III, Schones, Cui, Roh, Lhotsky, Wersto, Peng, Becker, Zhao, and Weng, 2009). Briefly, PBMCs were isolated by the Ficoll (GE Healthcare) gradient centrifugation. Enrichment of CD8 T cells (naïve and memory) was followed by a negative immunomagnetic separation process. Briefly, the removal of other cell types in PBMCs through incubation with a panel of mouse mAbs including: CD4, CD11b, CD19, CD14, CD16, MHC class II, erythrocytes, platelets, and CD45RO (for naïve cell enrichment) or CD45RA (for memory cell enrichment). The antibody bound cells were subsequently removed by the anti-mouse IgG magnetic beads (BioMag Goat Anti-Mouse IgG beads, Qiagen). Isolated CD8 T cells were incubated in the presence or absence of 1×10−6 M NE (catalog #A7256, Sigma-Aldrich), which was dissolved in PBS before being immediately added into human culture media (RPMI1640 with 10% FBS and penicillin (10 U/ml)/streptomycin (10 μg/ml)) (Life Technologies) for 16 hours. A NE concentration of 1×10−6 M is considered physiologically relevant (Sanders, 2012; Strell et al., 2009; Torres, Antonelli, Souza, Teixeira, Dutra, and Gollob, 2005; Wahle et al., 2006). The next day, NE-treated or untreated CD8 T cells were further sorted into naïve (CD45RA+, CD62L+), central memory cells (CD45RA−, CD62L+) and effector memory cells (CD62L−, CD45RA−) by a cell sorter (MoFlo, Dako Cytomation). The purity of sorted naïve and memory CD8 T cells was >96%. Isolated CD8 T cell subsets were either used for gene expression analysis immediately or incubated at 5% O2, with anti-CD3/28-coupled beads at a cell:bead ratio of 1:1 in human culture media, and harvested at the indicated time for analyses of mRNA. In addition, the culture supernatant was collected for cytokine protein analysis.

For isolation of naïve and memory CD8 T cells from cryopreserved PBMCs of human adults, PBMCs were thawed in a 37°C water bath, washed and resuspended in RPMI. Naïve and memory (Tcm+Tem) CD8 T cells were isolated by a cell sorter (MoFlo, Dako Cytomation) using the following staining: Viability dye (e506), CD8+, Naive (CD45RA+, CD28+), and memory (CD28+ −). The purity of sorted naïve and memory CD8 T cells was >96%.

2.4 Gene expression analysis by microarray

Genome-wide gene expression analysis was performed on NE-treated and untreated CD8 Tcm cells before and after anti-CD3/CD28 beads stimulation (24 and 72 hours) using Agilent’s whole genome array (SurePrint G3 Human GE 8×60K V2 Microarray Kit, Agilent Technologies). Three biological repeated samples were used for the resting and 24 hour time points, and two biological repeated samples for 72 hours were used. Each sample consisted of pooled RNA from 3 different donors, based on the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, RNA was isolated from cells (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen) and the integrity and quality of the RNA was tested using the Bioanalyzer Chip (Agilent).

Next, a two-color microarray-based gene expression analysis of ~60,000 genes/transcripts was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We started with 100 ng of total RNA of the sample and human universal reference RNA for labeling using the Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit based on the manufacturer’s instructions. The labeled probes were quantified by NanoDrop ND-1000 UV-VIS Spectrophotometer version 3.2.1 (G4851B, Agilent). Samples were hybridized onto whole human genome 8×60K array slides for 17 hours at 65°C in a rotator oven, followed by washing with appropriate Wash Buffers (Agilent). Hybridization signals were extracted via the Agilent Feature Extraction Software.

Two-color microarray data was first extracted from the Agilent reader, and was log-normalized relative to the reference color. Data was batch normalized and significant outliers were filtered using custom ‘perl’ scripts. Determination of the most significantly different gene ontology (GO) groups was done through Broad Institute’s Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) tool (Mootha, Lindgren, Eriksson, Subramanian, Sihag, Lehar, Puigserver, Carlsson, Ridderstrale, Laurila, Houstis, Daly, Patterson, Mesirov, Golub, Tamayo, Spiegelman, Lander, Hirschhorn, Altshuler, and Groop, 2003; Subramanian, Tamayo, Mootha, Mukherjee, Ebert, Gillette, Paulovich, Pomeroy, Golub, Lander, and Mesirov, 2005). We utilized the Biological Processes sub-category of the GO groups provided by Broad Institutes’ Molecular Signature Database. Groups were deemed significant at a FDR q-value of 0.25 or below. Genes of interest for each group were extracted based on the core enrichment value provided by GSEA. The pre-activation time point was studied alone; however, the post-activation 24-hour and 72-hour time points were combined into a single group during GSEA analysis. The entire microarray data set was deposited in the GEO database (GSE64635).

2.5 Quantitative RT-PCR of mRNA of human donors

The procedure for real time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was described previously (Araki et al., 2009). Briefly, RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit with Qiacube (Qiagen) and cDNA was synthesized with oligo-dT and random hexamers (Life Technologies) with 60ng of RNA. Primer sequences can be found in the Supplementary material (Supplementary Table 3). The mRNA levels were determined by quantitative RT-PCR using 2x SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Fisher Scientific) and normalized to a lymphocyte housekeeping gene, acyl-Coenzyme A oxidase 1 (ACOX1), as described previously (Araki et al., 2009). PCR was performed on 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

2.6 Measurement of cytokine protein by ELISA

Culture supernatants from CD8 T cell subsets were collected before, 24 hours, and 72 hours after anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation. The amount of cytokine proteins was determined by an ELISA kit (ELISA Max Deluxe Set Human: IL-2, IL-6, MCP-1, IL-1A, TNF, IFN-γ, Biolegend) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Concentrations were calculated according to the standard, and normalized to the number of cells among different samples.

2.7 Assay for Adrenergic Receptor agonist and antagonists

To verify if the ADRB2 is the primary receptor for NE on memory CD8 T cells, we isolated ADRB2+ and ADRB2− memory CD8 T cells by a cell sorter using anti-ADRB2 mAb by custom conjugation with PerCP/Cy5.5, as described in the above section. We also isolated memory CD8 T cells via a negative immunomagnetic separation described in Methods 2.3 for testing the ADRB2 agonist and antagonists. The purity of isolated memory CD8 T cells was ~82% (no detectable naïve CD8 or CD4 T cells) and had comparable changes in cytokine expression by NE and its agonist and antagonists when memory CD8 T cells were isolated by a cell sorter (data not shown).

To further determine that ADRB2 is the primary receptor for NE, we added Terbutaline (ADRB2 agonist, catalog #T2528, Sigma-Aldrich) at a concentration of 10−5 M and incubated for 16 hours before activation. For the antagonist experiments, Nadolol (beta-adrenergic receptor antagonist (ADRB), catalog #N1892, Sigma-Aldrich) or Phentalomine (alpha-adrenergic receptor (ADRA) antagonist, catalog #P7547 Sigma-Aldrich) were added at 10−5 M at the same time as NE. We did serial dilutions (10−3, 10−5 and 10−8 M) of the agonist and antagonists based on previous reports and found 10−5 M to be the most effective dose after titrating the agonist and antagonists (data not shown). The treated CD8 T cells were stimulated with CD3/CD28 antibodies. Treated cells were harvested and the culture supernatants were collected before and 24 hours after activation for RT-qPCR and ELISA analyses, respectively.

2.8 NE measurements in serum

NE was measured in the serum of all donors as described previously (Eisenhofer, Goldstein, Stull, Keiser, Sunderland, Murphy, and Kopin, 1986). Briefly, peripheral blood was collected after a 15 minute rest period and placed on ice until processed and stored at −80°C (Eisenhofer et al., 1986). When thawed, NE was measured using standard high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection that has been previously established for simultaneous measurement of the concentrations of catecholamines; quantification of NE was detected with a triple-electrode system. The designation of 150 pg/mL for the high or low NE level in serum was reached by averaging the 3 time points donors had their NE levels measured during a 3 month timeframe and finding the approximate median among the donors. NE levels of three measurements were quite stable as determined by the Spearmen’s rank correlation coefficient (0.735 for time point 1 vs. 2, 0.620 for time point 1 vs. 3, and 0.694 for time point 2 vs. 3) and by a Kruskal-Wallis test for the differences between the three time points (p=0.815). Utilization of these samples and the primary investigation where the samples originated was approved by the Internal Review Board at the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), NIH and the University of Pennsylvania.

2.9 Statistics

Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM and significance was assessed using the paired Student’s t-test. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1 ADRB2 is highly expressed in the memory subsets compared to the naïve subset of CD8 T cells

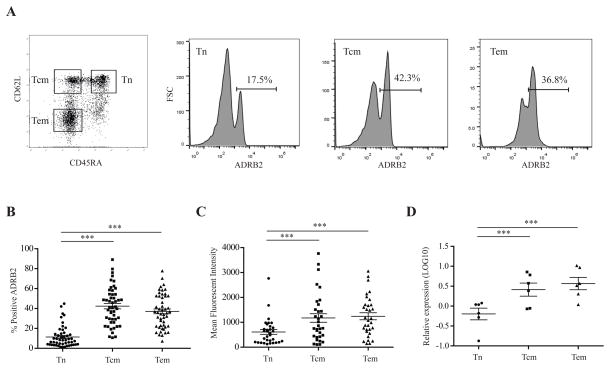

Previous studies have found that ADRB2 is heterogeneously expressed on different immune cells (Anstead et al., 1998; Kohm et al., 2001; Sanders, 2012), yet the expression of ADRB2 on CD8 T cell subsets is not known. We first assessed the surface expression of ADRB2 by flow cytometry on the 3 subsets of CD8 T cells (Tn, Tcm and Tem) in the PBMCs of healthy human adults (Fig. 1A). We found that the memory populations (Tcm and Tem) of CD8 T cells expressed a significantly higher percentage (~40%) of ADRB2 compared to the Tn population (~10%) (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, memory CD8 T cells also expressed significantly more ADRB2 on average compared to Tn cells as measured by MFI with flow cytometry (Fig. 1C). To further determine if ADRB2 expression is regulated by transcription, we assessed the mRNA level of ADRB2 in Tn, Tcm and Tem and found greater expression (0.61 fold higher) in memory CD8 T cells (Tcm and Tem) compared to Tn cells (Fig. 1D). Together, our findings show that ADRB2 is highly expressed in memory CD8 T cell populations compared to the Tn population.

Figure 1. The beta-2 adrenergic receptor is highly expressed in the memory subsets compared to the naïve subset of CD8 T cells.

(A) Representative figures of the flow cytometry staining for ADRB2 expression on CD8 T cell subsets. Lymphocytes were gated from the peripheral mononuclear cell (PBMC) sample followed by a CD8+ T cell (APC) gate. CD8 T cell subsets, naïve (CD45RA+CD62L+), central memory (CD45RA−CD62L+) and effector memory (CD45RA−CD62L−) cells were gated for measure of ADRB2 expression. Representative histograms of Tn, Tcm and Tem percentage of ADRB2 expression is presented. Staining for ADRB2 was described in the Methods. (B) ADRB2 expression in individual CD8 T cell subsets. ADRB2 expression is presented as a percentage for each CD8 T cell subset: naïve (Tn), central memory (Tcm) and effector memory (Tem). There was a significant difference in the percentage of ADRB2 expression between Tn and memory (Tcm and Tem) T cells (N=50, p<0.001). (C) Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of ADRB2 expression in CD8 T cell subsets. The MFI of each CD8 T cell subset was measured to examine the average expression of ADRB2 on each type of cell. Per subject, memory CD8 T cells expressed significantly more ADRB2 compared to naïve cells (N=50, p<0.001). (D) ADRB2 expression on the mRNA level of Tn, Tcm and Tem subsets in healthy human adults by RT-qPCR. Data is presented as the relative mRNA expression in the LOG10 value (N=6). Figures throughout this manuscript illustrated the results with the mean and SEM. Significance is identified as follows: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001

3.2 NE induces expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in memory CD8 cells

The effect of NE on the expression of several cytokines in CD8 T cells has been reported (Kalinichenko et al., 1999; Sanders, 2012; Strell et al., 2009), but a genome-scale assessment of NE-induced changes in CD8 T cells has not been conducted. We focused on Tcm cells because of their critical role in the recall response for adaptive immunity and their high level of ADRB2 expression. To determine the overall impact of NE on human CD8 T cells, we conducted a genome-wide analysis of gene expression changes in CD8 Tcm cells after NE exposure using a microarray. CD8 Tcm cells were isolated from healthy adults and treated with NE for 16 hours before stimulation with antibodies against CD3 and CD28 (anti-CD3/CD28), and harvested before and 24, 72 hours after stimulation for gene expression analyses. Genes with the greatest degree of changes after NE treatment were identified (Supplemental Table 4).

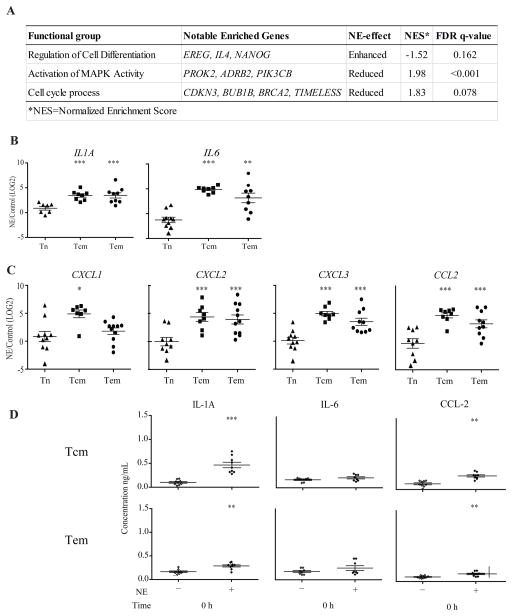

A functional assessment using GSEA of altered gene expressions by NE treatment revealed important biological and immunological functions, including regulation of cell differentiation, cell cycle process and MAPK activity (Fig. 2A). Among the NE induced genes that were identified based on GSEA and fold changes, we focused on the inflammatory cytokines and relied on RT-qPCR method to confirm and extend our analysis to other inflammatory cytokines in all CD8 T cell subsets (Tn, Tcm and Tem). We found that Tcm and Tem exhibited a similar upregulation of IL1A and IL6, while Tn cells did not show a significant difference in expression between NE treated and untreated cells (Fig. 2B). Both IL1A and IL6 have multiple, important functions in inflammation (Ershler and Keller, 2000). In addition, several chemokines related to the inflammatory and chemoattraction processes were also upregulated in the NE treated cells, including CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL3 and CCL2, as determined by the RT-qPCR method (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. Increased gene expression of inflammatory cytokines in CD8 Tcm cells treated with norepinephrine.

(A) Relevant Gene Ontology (GO) groups extracted from GSEA comparison between NE treated and untreated CD8 Tcm cells before activation. These groups had significant FDR q-values (<0.25), and representative genes were chosen from the set of core enriched genes, also derived from GSEA. (B) and (C) Significantly increased inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (mRNA) after NE treatment. RT-qPCR was done based on the microarray results for the selected cytokine genes significantly increased by NE treatment. Results are presented as a ratio (NE/Control) on the Log2 scale for the naïve (Tn), central memory (Tcm) and effector memory (Tem) subsets of CD8 T cells (N=7–11). (D) Protein levels of the selected cytokines and chemokines altered by NE treatment examined via ELISA. Results are presented as the concentration (ng/mL) of the cytokine or chemokine in the controls (untreated) and NE treated central memory (Tcm) and effector memory (Tem) cells at 0 hours (N=6–14).

Next, we assessed whether the NE induced changes observed at the mRNA level correlate with the protein level. We then measured protein levels of selected cytokines and chemokines in the culture supernatant of the memory CD8 T cells by ELISA. Since NE treated Tn cells did not show any significant gene expression changes, we did not further investigate this population. A similar increase in the protein levels of IL-1A and CCL-2, but not IL-6 were observed (Fig. 2D). Together, these results demonstrate that memory CD8 T cells were more susceptible to the effects of NE than the naïve CD8 T cell subset, and suggest that NE exposure induces a pro-inflammatory state in memory CD8 T cells.

3.3 Activation induces greater expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in NE treated memory CD8 cells

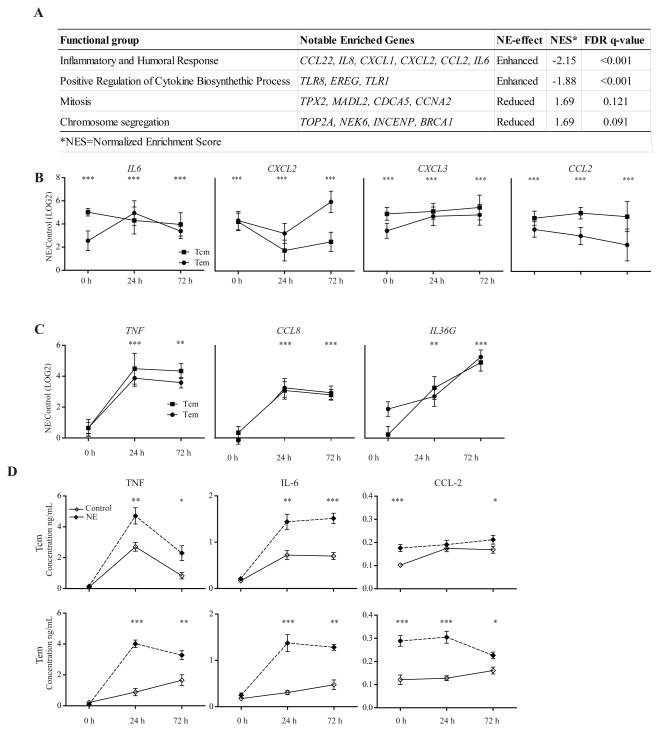

We next asked what impact NE would have on memory CD8 T cells in response to activation and again found several cytokines and chemokines significantly upregulated (top 100 most altered genes after activation are identified in Supplemental Table 5). Using GSEA, we identified the altered biological and immunological functions in NE-treated Tcm CD8 cells (Fig. 3A). We again focused on the inflammatory cytokines and relied on RT-qPCR method to confirm and extend our analyses to other inflammatory cytokines in memory CD8 T cells (Tcm and Tem).

Figure 3. Activation induces greater expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in norepinephrine treated memory CD8T cells.

(A) Relevant Gene Ontology (GO) groups extracted from GSEA comparison between treated and untreated CD8 Tcm cells after activation. These groups had significant FDR q-values (<0.25), and representative genes were chosen from the set of core enriched genes, also derived from GSEA. (B) Significantly increased inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (mRNA) in NE treated CD8 T cells before and activation. Results are presented as a ratio (NE/Control) on a LOG2 scale for 0, 24, and 72 hours in Tcm and Tem cells (N=6–14). (C) Significantly increased inflammatory cytokines and chemokines (mRNA) in NE treated CD8 T cells only after activation. Data is presented as a ratio (NE/Control) on a LOG2 scale for 0, 24, 72 hours in Tcm and Tem cells (N=6–14). (D) Protein level expression of selected cytokines and chemokines at 0, 24, 72 hours after activation in untreated (control) and NE treated Tcm and Tem cells. Data is presented as the concentration (ng/mL) (N=6–12).

Among the altered expressed genes, IL6, CXCL2, CXCL3, and CCL2 were upregulated with NE treatment before activation and remained upregulated after activation compared to controls (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, two pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF and IL36G) and a chemokine (CCL8) were upregulated in NE treated memory CD8 T cells only after activation (Fig. 3C). We examined TNF specifically since it is a well-known pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in inflammatory-related diseases. CCL8, a chemokine involved in several immune-regulatory and inflammatory processes, exhibited a similar enhanced expression pattern to TNF, whereas IL36G, participating in local inflammatory responses, showed an increased enhancement of expression from 24 to 72 hours compared to the control (Fig. 3C).

Protein levels of TNF, IL-6 and CCL-2 in the culture supernatant correlated with the gene expression changes at 24 and 72 hours after activation (Fig. 3D). We observed an average four-fold increase in the protein level of TNF compared to a two-fold difference in IL-6 and CCL-2. In 5 of the 6 cases, the most significant difference in protein levels between untreated and treated memory CD8 T cells was observed at 24 hours.

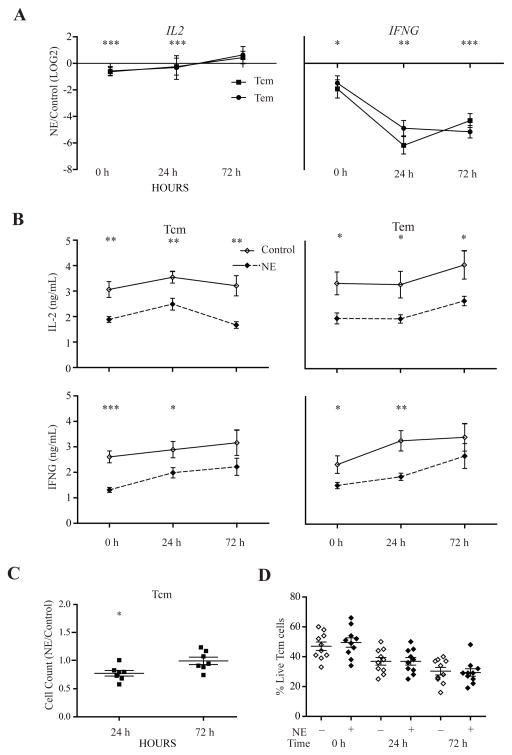

3.4 Activation induces lower expression of growth-related genes in NE treated memory CD8 T cells and consequently reduces activation-induced expansion of CD8 T cells

In contrast to the enhanced expression of inflammatory cytokines in NE-treated memory CD8 T cells before and after stimulation, we also identified two growth-related cytokines (IL2 and IFNG) whose expression levels were reduced in NE-treated memory but not naïve CD8 T cells after stimulation. IL2 met both criteria of the altered gene expression by the microarray and RT-qPCR; however, IFNG did not meet the criteria of our microarray, but was confirmed by RT-qPCR as significantly altered with NE treatment (Fig. 4A). IL2 is an important growth factor and IFNG has been previously shown to promote the growth of memory T cells (Asao and Fu, 2000; Kryczek, Wei, Gong, Shu, Szeliga, Vatan, Chen, Wang, and Zou, 2008; Zhang, Sun, Hwang, Tough, and Sprent, 1998). The reduced expressions of IL2 and IFNG were further confirmed at the protein levels in the culture supernatant of stimulated memory CD8 T cells (Fig. 4B). These findings suggest that NE has an immunosuppressive effect on memory CD8 T cells by significantly down-regulating cytokines critical for the proliferation of CD8 T cells.

Figure 4. Activation of NE treated memory CD8 T cells led to decreased expression of IL2 and IFNG in the memory subsets resulting in a reduced activation-induced expansion.

(A) Decrease in proliferation-related cytokines, IL2 and IFNG, at the mRNA level in memory CD8 T cells. RT-qPCR was used for confirmation of microarray results as well as examining gene expression changes in the naïve (Tn) and effector memory (Tem) subsets. Results are presented as a ratio (NE/Control) in the LOG2 value from baseline to 24 and 72 hours after activation (N=6–14). (B) Protein levels of memory subsets (Tcm and Tem) as measured by ELISA at baseline, 24 and 72 hours after activation in control and NE treated cells. Data is presented as the concentration (ng/mL) (N=7–12). (C) Cell counts of Tcm cells at 24 and 72 hours after activation. Results are presented as the ratio (NE/Control) at 24 and 72 hours after activation in central memory (Tcm) cells (N=15). (D) Viability of Tcm cells was examined by viability dye (7AAD) and apoptosis dye (Annexin V) at 0, 24 and 72 hours after activation. Data is presented as the percentage of live cells which was determined by the gated Tcm cells followed by 7AAD− and Annexin V− gated cells in flow cytometry of the NE treated and untreated cells (N=10).

To determine the impact of the reduced expression of growth-related cytokines such as IL-2 and IFN-γ, we assessed the activation-induced expansion of memory CD8 T cells and observed a significant reduction in the cell number of NE treated CD8 Tcm cells 24 hours after activation compared to the NE untreated CD8 Tcm cells (Fig. 4C). To rule out the potential role of cell death in the differences in activation-induced expansion, we analyzed cell viability and found no significant difference in the viability of Tcm cells between NE treated and untreated Tcm cells at baseline, 24 or 72 hours after activation (Fig. 4D).

3.5 NE effect on memory CD8 T cells is mediated by ADRB2

NE can bind to other adrenergic receptors aside from the ADRB2 (Ramer-Quinn et al., 1997). To determine if ADRB2 was responsible for the observed NE effects on memory CD8 T cells, we isolated ADRB2+ and ADRB2− CD8 memory T cells with a cell sorter. The effects of NE on the expression of IL1A and IL6 (before activation), and IL2 and TNF (after 24 hour activation) were significantly greater in the ADRB2+ than in the ADRB2− memory CD8 T cells (Fig. 5A). To further determine whether the effects of NE were through ADRB2 but not ADRB1, we treated resting memory CD8 T cells with an ADRB2 agonist, Terbutaline, and found it induced an indistinguishable level of changes in mRNA and protein levels of IL1A and IL6 compared to the NE treated memory CD8 T cells (Fig. 5B and 5C). We also determined if NE stimulates the ADRB2 specifically by exposing memory CD8 T cells to NE in the presence or absence of either the beta-adrenergic receptor (ADRB) antagonist (Nadolol) or the alpha adrenergic receptor (ADRA) antagonist (Phentalomine). Blocking ADRB with Nadolol abolished the NE effect on IL1A and IL6 but blocking ADRA with Phentalomine did not have an obvious impact on NE’s effect on IL1A and IL6 expression (Fig. 5B and C), suggesting NE’s effect on memory CD8 T cells is primary mediated by ADRB2, but not by ADRA. We extended the antagonist analysis to activation-induced changes in gene expression affected by NE and observed a similar response: Terbutaline mimicked NE’s effect; Nadolol blocked NE’s effect, and Phentalomine did not block NE’s effect on IL2 and TNF expression (Fig. 5D and E).

Figure 5. NE action in memory CD8 T cells is mediated by ADRB2.

(A) ADRB2+ CD8 Tcm cells respond to NE treatment. We isolated ADRB2+ and ADRB2− CD8 Tcm cells from the blood of human donors. Relative mRNA levels of cytokines in the ADRB2+ cells compared to ADRB2− cells before (IL1A and IL6) and 24 hours after activation (IL2 and TNF) are presented (N=6). (B) The effect of ADRB2 agonist and antagonists on NE-induced cytokine expression (mRNA) before activation. Memory CD8 T cells were isolated and cultured with NE or an ADRB2 agonist (Terbutaline) alone or NE plus an antagonist (either an ADRB antagonist (Nadolol) or an ADRA antagonist (Phentalomine)). Relative expression changes of IL1A and IL6 under these treatments are presented (N=12). (C) The effect of the adrenergic receptor agonist and antagonists on NE-induced cytokine expression (protein) before activation. Similar changes of IL-1A and IL-6 protein concentration levels (ng/ml) in the culture supernatant under the treatments of the agonist (Terbutaline) and antagonists (Nadolol or Phentalomine) are presented (N=8). (D) The effect of the adrenergic receptor agonist and antagonists on NE induced cytokine expression (mRNA) after activation. Relative levels of IL2 and TNF mRNA changes after 24 hours of activation under NE alone, Terbutaline alone, NE plus Nadolol, and NE plus Phentalomine are presented (N=12). (E) The effect of the adrenergic receptor agonist and antagonists on NE induced cytokine expression (protein) after activation. IL-2 and TNF protein concentration levels (ng/ml) in the culture supernatant under the treatment of the agonist (Terbutaline) and antagonists (Nadolol or Phentalomine) are presented (N=8).

3.6 High blood NE levels are associated with enhanced expression of inflammatory cytokines in memory CD8 T cells

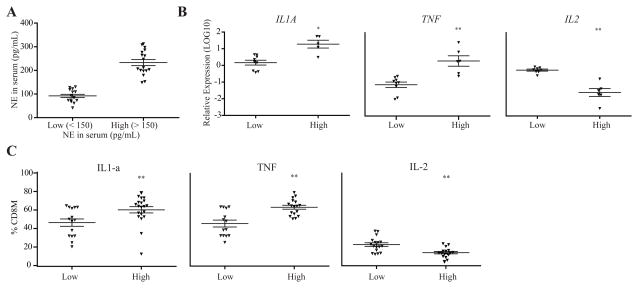

Our in vitro experiments illustrate a previously unknown effect of NE inducing greater expression of inflammatory cytokines in memory CD8 T cells. We next asked if these findings would exist in an in vivo model by analyzing the relationship of blood NE levels and inflammatory cytokine expressions in memory CD8 T cells in 32 adults participating in a primary investigation examining the effects of chronic stress on health outcomes. Subjects who participated in this study had their serum NE level measured at each visit with a total of 3 measurements over approximately 3 months. Based on the approximate median of the blood NE levels, we grouped subjects into two groups: high (>150 pg/mL) and low NE levels (<150 pg/mL) (Fig. 6A). We isolated memory and naïve CD8 T cells from frozen PBMCs of these subjects by a cell sorter and analyzed the expression of inflammatory cytokines identified from our in vitro work with RT-qPCR and flow cytometry.

Figure 6. Altered inflammatory cytokines in adults with higher levels of norepinephrine.

(A) Blood NE levels in study subjects. Blood NE levels are separated into two groups based on the approximate median: low NE levels (<150 pg/mL) (N=18) and high NE levels (>150 pg/mL) (N=14). Data is shown as NE levels measured in the serum (pg/mL) in the two groups (low and high) in which the following analyses were conducted. (B) Gene expression changes between the low NE group and the high NE group examined using RT-qPCR. Data is presented as the LOG10 value (N=9 for high and N=6 for the low blood NE group). (C) Cytokine protein levels (IL-2, IL1-α, TNF) in memory CD8 T cells measured by intracellular staining between the low and high NE groups. Data is presented as the percentage of cells in each group (N=14–17 for high and N=17–22 for the low NE group).

We found that IL1A and TNF were significantly higher in memory CD8 T cells of the high NE group than the low NE group, whereas IL2 was significantly lower in memory CD8 T cells of the high NE group compared to the low NE group (Fig. 6B). We then measured the protein levels of these 3 cytokines via intracellular staining with flow cytometry. We found adults in the high NE group had significantly higher percentages of memory CD8 T cells expressing IL-1A and TNF, but a significantly lower percentage of memory CD8 T cells expressing IL-2 (Fig. 6C).

4. Discussion

Here we conducted a comprehensive assessment of how NE modulates CD8 T cell subsets by examining ADRB2 expression, transcriptional and protein level alterations, and activation-induced expansion in both an in vitro condition using a physiological relevant concentration of NE, and in an in vivo setting using a study cohort with known serum NE levels. Our results demonstrate that ADRB2 is highly expressed in memory CD8 T cells, revealing the preferential effect of NE on memory CD8 T cells. Furthermore, we found that NE induces inflammatory cytokine production while simultaneously reducing production of growth-related cytokines, leading to a reduced activation-induced expansion of memory CD8 T cells. Ultimately, this indicates a two-sided effect of NE on memory CD8 T cells. Finally, we show that a high serum concentration of NE is associated with a high expression of inflammatory cytokines and a low expression of growth-related cytokines in the memory CD8 T cells of stressed adults. NE’s preferential impact on memory CD8 T cells may help improve our understanding of the mechanisms of NE in chronic stress-associated immune-related disorders such as viral and bacterial infections (Farias, Teixeira, Moreira, Oliveira, and Pereira, 2011; Kemeny and Schedlowski, 2007).

ADRB2 is known to be expressed differently in different type of cells within PBMCs and believed to be the main receptor for NE (Sanders, 2012). Our study extends these findings by showing ADRB2 is differentially expressed on naïve and memory CD8 T cells. Fewer naïve CD8 T cells express ADRB2, but significantly more antigen-experienced memory CD8 T cells express ADRB2. Furthermore, ADRB2 is significantly more abundant on memory than naïve CD8 T cells. Previous studies also show that ADRB2 plays a critical role in regulating the immune function of lymphocytes (Anstead et al., 1998; Bonneau, Kiecolt-Glaser, and Glaser, 1990; Khan et al., 1986; Mills, Adler, Dimsdale, Perez, Ziegler, Ancoli-Israel, Patterson, and Grant, 2004; Mills, Ziegler, Patterson, Dimsdale, Hauger, Irwin, and Grant, 1997). Here, we demonstrate memory CD8 T cells expressing ADRB2 respond to NE, but memory CD8 T cells that are ADRB2 negative do not respond to NE. The effect of NE on memory CD8 T cells is primarily through ADRB2, as supported by the results from the receptor agonist and antagonists assays. The ADRB2 agonist was able to mimic the changes induced by NE at the mRNA and protein level. The alpha antagonist showed no effect on NE-induced changes in expression of the four cytokines tested, while the beta adrenergic antagonist almost completely blocked NE’s effect on these cytokines. Our findings suggest that ADRB2 is the primary receptor for NE, and ADRA does not play a measurable role in NE-induced memory CD8 T cell changes. Our findings demonstrate for the first time that ADRB2 expression in CD8 T cells is differentially regulated and the impact of NE is preferentially on memory CD8 T cells. Further studies need to be conducted to provide further insight into the mechanisms behind altered cytokine production in memory CD8 T cells following NE binding to the ADRB2.

Chronic stress and inflammation is intricately linked via a network of interactions mediated by neurotransmitters and hormones (Carlson, Brooks, and Roszman, 1989; Levite, 2000; Straub, Westermann, Scholmerich, and Falk, 1998). NE is also implicated in the inflammatory response through a variety of pathways, one of them being the regulation of IFN-γ production in immune cells (Dhabhar, Malarkey, Neri, and McEwen, 2012; Dimsdale, Mills, Patterson, Ziegler, and Dillon, 1994; Mausbach, Dimsdale, Ziegler, Mills, Ancoli-Israel, Patterson, and Grant, 2005; Sperner-Unterweger, Kohl, and Fuchs, 2014). However, the global scope and the type of T cell subsets that respond to NE have not been previously addressed. Our global gene expression analysis of memory CD8 T cells before and after activation reveals some unexpected and rich findings of NE-induced production of a large panel of inflammatory cytokines by memory CD8 T cells. Interestingly, we found NE induced an inflammatory state in memory CD8 T cells even before the cells were activated. Cytokines genes such as IL6 and TNF play an important role in the pro-inflammatory response as well as a variety of other immune responses. Chemokines discussed such as CCL2, CXCL1 and CXCL3 also mediate inflammatory responses as well as having important chemotactic activity for lymphocyte and monocyte migration. After activation, some of the same inflammatory cytokines and chemokines were still significantly increased as well as some new inflammatory markers.

Previous studies have shown the inhibitory impact of NE on immune cells (Kalinichenko et al., 1999; Kohm et al., 2000; Kohm et al., 2001; Lang et al., 2003; Malarkey, Wang, Cheney, Glaser, and Nagaraja, 2002; Ramer-Quinn, Swanson, Lee, and Sanders, 2000; Swanson, Lee, and Sanders, 2001), including CD8 T cells and the alteration in IFN-γ and IL-2 production (Strell et al., 2009; Torres et al., 2005; Wahle et al., 2006). Our study supports these findings by showing a reduction in the expression of IFN-γ and IL-2 in NE treated memory CD8 T cells. The decrease in IL-2 and IFN-γ production may contribute to the modest decrease in cell number found in NE treated cells after stimulation, which may play a role in altering the proliferation of NE treated compared to untreated memory CD8 T cells. However, the precise intracellular pathways leading to these transcriptional and protein changes requires further investigation.

Findings from our study of CD8 T cell subsets may help explain the conflicting findings of previous studies looking at the effect of NE on immune cells to be immune suppressive, immune-enhancing, or null (Dhabhar et al., 2012; Kin et al., 2006; Strell et al., 2009). By studying immune cells in PBMCs rather than specific cell types, or even subsets (naïve or memory), the actual effects of NE on a subset of lymphocytes can be masked by the larger group of other types of immune cells. Future studies will benefit from utilizing defined types of immune cells and their subsets to draw out the impact of NE on these cells. Memory CD8 T cell sensitivity to NE may have clinical relevance since memory cells are responsible for recall immune responses as opposed to naïve cells that fight off new challenges. An individual with high levels of NE may be more compromised in terms of fighting off recall infections rather than new antigenic challenges.

Compared to our in vitro findings under controlled conditions, in vivo changes are likely influenced by multiple factors. It is therefore reassuring to find that some inflammatory-related cytokines and chemokines in adults with high blood levels of NE are also elevated in memory CD8 T cells compared to adults with low blood levels of NE; these findings are similar to the inflammatory response we observed in vitro. We also examined other cytokines and chemokines (CCL2, IFNG, IL6, CXCL1, and CCL8) but did not find significant differences between the high and low NE groups. There was also no difference in ADRB2 expression between the high or low NE groups in lymphocytes, Tn, or Tm cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). It is important to note that the effects observed in vivo could be a result of a combined influence from hormones and neurotransmitters including NE directly or indirectly (Straub, Schaller, Miller, von, Jessop, Falk, and Scholmerich, 2000; Straub et al., 1998). Nevertheless, NE appears to play an important role in modulating CD8 T cell function, particularly in memory cells.

The impact of chronic stress on immune function is undoubtedly complex. More work needs to be done to better understand the impact of NE on CD8 T cells as well as on other types of lymphocytes such as CD4 and B cells. Investigating the effect of NE under defined in vitro conditions and some suitable in vivo settings will help to elucidate the role of NE in modulating immune function. Future work should also focus on the clinical implications of high NE levels, particularly on immune health outcomes as well as interventions to alleviate the effects of stress on the immune system.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Memory CD8 T cells express more beta 2 adrenergic receptors than naïve cells

NE treated memory CD8 T cells produce more inflammatory cytokines

NE treated memory CD8 T cells produce less growth-related cytokines

Memory CD8 T cells from adults with high NE have more inflammatory cytokine expression

Acknowledgments

This research work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Graduate Partnership Program Fellowship of the National Institute for Nursing Research, and Clinical Center National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Funding Sources

The Intramural Program at the National Institute on Aging and National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and the Graduate Partnership Program with the National Institute on Nursing Research.

We thank Dr. Robert Wersto and staff at the NIA Flow Cytometry Unit for cell sorting, NIA Apheresis Unit for collecting blood samples, Dr. Karel Pacak at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH for the norepinephrine measurements, and Drs. Connie Ulrich, Bruce Levine and Ranjan Sen for critically reading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anstead MI, Hunt TA, Carlson SL, Burki NK. Variability of peripheral blood lymphocyte beta-2-adrenergic receptor density in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:990–992. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.3.9704071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araki Y, Wang Z, Zang C, Wood WH, III, Schones D, Cui K, Roh TY, Lhotsky B, Wersto RP, Peng W, Becker KG, Zhao K, Weng NP. Genome-wide analysis of histone methylation reveals chromatin state-based regulation of gene transcription and function of memory CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:912–925. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asao H, Fu XY. Interferon-gamma has dual potentials in inhibiting or promoting cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:867–874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonneau RH, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Stress-induced modulation of the immune response. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;594:253–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb40485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson SL, Brooks WH, Roszman TL. Neurotransmitter-lymphocyte interactions: dual receptor modulation of lymphocyte proliferation and cAMP production. J Neuroimmunol. 1989;24:155–162. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(89)90109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhabhar FS, Malarkey WB, Neri E, McEwen BS. Stress-induced redistribution of immune cells--from barracks to boulevards to battlefields: a tale of three hormones--Curt Richter Award winner. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:1345–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimsdale JE, Mills P, Patterson T, Ziegler M, Dillon E. Effects of chronic stress on beta-adrenergic receptors in the homeless. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:290–295. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenhofer G, Goldstein DS, Stull R, Keiser HR, Sunderland T, Murphy DL, Kopin IJ. Simultaneous liquid-chromatographic determination of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol, catecholamines, and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine in plasma, and their responses to inhibition of monoamine oxidase. Clin Chem. 1986;32:2030–2033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elenkov IJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP, Vizi ES. The sympathetic nerve--an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain and the immune system. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:595–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ershler WB, Keller ET. Age-associated increased interleukin-6 gene expression, late-life diseases, and frailty. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:245–270. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farias SM, Teixeira OL, Moreira W, Oliveira MA, Pereira MO. Characterization of the physical symptoms of stress in the emergency health care team. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2011;45:722–729. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342011000300025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gouin JP, Hantsoo L, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. Immune dysregulation and chronic stress among older adults: a review. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2008;15:251–259. doi: 10.1159/000156468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu D, Wan L, Chen M, Caudle Y, LeSage G, Li Q, Yin D. Essential role of IL-10/STAT3 in chronic stress-induced immune suppression. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2014;36:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalinichenko VV, Mokyr MB, Graf LH, Jr, Cohen RL, Chambers DA. Norepinephrine-mediated inhibition of antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocyte generation involves a beta-adrenergic receptor mechanism and decreased TNF-alpha gene expression. J Immunol. 1999;163:2492–2499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kemeny ME, Schedlowski M. Understanding the interaction between psychosocial stress and immune-related diseases: a stepwise progression. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:1009–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan MM, Sansoni P, Silverman ED, Engleman EG, Melmon KL. Beta-adrenergic receptors on human suppressor, helper, and cytolytic lymphocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35:1137–1142. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, Malarkey WB, Sheridan J. Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3043–3047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kin NW, Sanders VM. It takes nerve to tell T and B cells what to do. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:1093–1104. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohm AP, Sanders VM. Norepinephrine: a messenger from the brain to the immune system. Immunol Today. 2000;21:539–542. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohm AP, Sanders VM. Norepinephrine and beta 2-adrenergic receptor stimulation regulate CD4+ T and B lymphocyte function in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:487–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kryczek I, Wei S, Gong W, Shu X, Szeliga W, Vatan L, Chen L, Wang G, Zou W. Cutting edge: IFN-gamma enables APC to promote memory Th17 and abate Th1 cell development. J Immunol. 2008;181:5842–5846. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.5842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang K, Drell TL, Niggemann B, Zanker KS, Entschladen F. Neurotransmitters regulate the migration and cytotoxicity in natural killer cells. Immunol Lett. 2003;90:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levite M. Nerve-driven immunity. The direct effects of neurotransmitters on T-cell function Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;917:307–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malarkey WB, Wang J, Cheney C, Glaser R, Nagaraja H. Human lymphocyte growth hormone stimulates interferon gamma production and is inhibited by cortisol and norepinephrine. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;123:180–187. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00489-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, Ziegler MG, Mills PJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Patterson TL, Grant I. Depressive symptoms predict norepinephrine response to a psychological stressor task in Alzheimer’s caregivers. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:638–642. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000173312.90148.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mills PJ, Adler KA, Dimsdale JE, Perez CJ, Ziegler MG, Ancoli-Israel S, Patterson TL, Grant I. Vulnerable caregivers of Alzheimer disease patients have a deficit in beta 2-adrenergic receptor sensitivity and density. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:281–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills PJ, Ziegler MG, Patterson T, Dimsdale JE, Hauger R, Irwin M, Grant I. Plasma catecholamine and lymphocyte beta 2-adrenergic receptor alterations in elderly Alzheimer caregivers under stress. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:251–256. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199705000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstrale M, Laurila E, Houstis N, Daly MJ, Patterson N, Mesirov JP, Golub TR, Tamayo P, Spiegelman B, Lander ES, Hirschhorn JN, Altshuler D, Groop LC. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakai A, Hayano Y, Furuta F, Noda M, Suzuki K. Control of lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes through beta2-adrenergic receptors. J Exp Med. 2014 doi: 10.1084/jem.20141132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Padgett DA, Glaser R. How stress influences the immune response. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:444–448. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramer-Quinn DS, Baker RA, Sanders VM. Activated T helper 1 and T helper 2 cells differentially express the beta-2-adrenergic receptor: a mechanism for selective modulation of T helper 1 cell cytokine production. J Immunol. 1997;159:4857–4867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramer-Quinn DS, Swanson MA, Lee WT, Sanders VM. Cytokine production by naive and primary effector CD4+ T cells exposed to norepinephrine. Brain Behav Immun. 2000;14:239–255. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2000.0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders VM. The beta2-adrenergic receptor on T and B lymphocytes: do we understand it yet? Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders VM, Kasprowicz DJ, Swanson-Mungerson MA, Podojil JR, Kohm AP. Adaptive immunity in mice lacking the beta(2)-adrenergic receptor. Brain Behav Immun. 2003;17:55–67. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(02)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders VM, Straub RH. Norepinephrine, the beta-adrenergic receptor, and immunity. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:290–332. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sperner-Unterweger B, Kohl C, Fuchs D. Immune changes and neurotransmitters: possible interactions in depression? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014;48:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Straub RH, Schaller T, Miller LE, von HS, Jessop DS, Falk W, Scholmerich J. Neuropeptide Y cotransmission with norepinephrine in the sympathetic nerve-macrophage interplay. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2464–2471. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Straub RH, Westermann J, Scholmerich J, Falk W. Dialogue between the CNS and the immune system in lymphoid organs. Immunol Today. 1998;19:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strell C, Sievers A, Bastian P, Lang K, Niggemann B, Zanker KS, Entschladen F. Divergent effects of norepinephrine, dopamine and substance P on the activation, differentiation and effector functions of human cytotoxic T lymphocytes. BMC Immunol. 2009;10:62. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swanson MA, Lee WT, Sanders VM. IFN-gamma production by Th1 cells generated from naive CD4+ T cells exposed to norepinephrine. J Immunol. 2001;166:232–240. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Torres KC, Antonelli LR, Souza AL, Teixeira MM, Dutra WO, Gollob KJ. Norepinephrine, dopamine and dexamethasone modulate discrete leukocyte subpopulations and cytokine profiles from human PBMC. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;166:144–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Tits LJ, Michel MC, Grosse-Wilde H, Happel M, Eigler FW, Soliman A, Brodde OE. Catecholamines increase lymphocyte beta 2-adrenergic receptors via a beta 2-adrenergic, spleen-dependent process. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:E191–E202. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.1.E191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wahle M, Hanefeld G, Brunn S, Straub RH, Wagner U, Krause A, Hantzschel H, Baerwald CG. Failure of catecholamines to shift T-cell cytokine responses toward a Th2 profile in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R138. doi: 10.1186/ar2028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang X, Sun S, Hwang I, Tough DF, Sprent J. Potent and selective stimulation of memory-phenotype CD8+ T cells in vivo by IL-15. Immunity. 1998;8:591–599. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.