Abstract

Objectives

To determine for females with childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) who require cyclophosphamide the dose of triptorelin that suffices to maintain complete ovarian suppression (COS); measure the time needed to achieve ovarian suppression after triptorelin initiation, and explore the safety of triptorelin.

Methods

In this randomized double-blind placebo-controlled dose-escalation study females (< 21 years) were randomized 4:1 to receive triptorelin or placebo (25 triptorelin, 6 placebo). Starting doses of triptorelin between 25 and 100 microgram/kg/dose were used. Triptorelin dosage was escalated until COS was maintained. The primary outcome was the weight-adjusted dose of triptorelin that for at least 90% of the patients provides COS based on Gonadotropin-releasing-hormone Agonist Stimulation Testing. Secondary outcomes were time to ovarian suppression measured by unstimulated FSH and LH levels after study drug initiation.

Results

Triptorelin dosed at 120 microgram/kg bodyweight led to sustained COS in 90% of the patients. After the initial dose of triptorelin 22 days were needed for achieve COS. Rates of adverse events (AE) and serious adverse events (SAE) per 100 patient-month of follow-up were not higher in the triptorelin group as compared to the placebo group (triptorelin vs. placebo; AE: 189 vs. 362; SAE: 2.05 vs. 8.48).

Conclusions

For achieving and maintaining COS high doses of triptorelin are needed but appear to be well tolerated in adolescent females with cSLE. Our data suggest that a lag time of 22 days after triptorelin initiation is required before starting or continuing cyclophosphamide-therapy.

Trial Registration Number

clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00124514

Key Terms: SLE, Gonadotoxicity, children, cyclophosphamide, Triptorelin, lupus, adolescents

INTRODUCTION

Alongside corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide is among the standard therapies for severe organ manifestations of childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) (1–3). Cyclophosphamide has been associated with gonadotoxicity, and there are reports of premature ovarian failure in adults and some children after treatment with cyclophosphamide. Previous research proposes that the risk of premature ovarian failure is influenced by patient age and sexual maturation stage at the time of cyclophosphamide-therapy, as well as the cumulative amount of cyclophosphamide used (4). Reports from women with SLE suggest that the frequency of premature ovarian failure is less than 50% among those younger than 30 years but around 60% among females age 30 to 40 years (5). Based in small open-labels studies, reduction of ovarian reserves can occur in cSLE, and an estimated 11% of girls who are treated with cyclophosphamide for cSLE can develop premature ovarian failure (6, 7).

Gonadotropin-releasing-hormone agonists (GnRH-a), such as triptorelin, offer ovarian protection during cyclophosphamide-therapy (8). The basis of gonadoprotection includes decreased oocyte maturation, which appears to render the germinal epithelium less susceptible to gonadotoxic insults. GnRH-a may act via desensitization and down-regulation of pituitary GnRH receptors, so that gonadotropin release is gradually inhibited after an initial stimulation phase. Hence, use of GnRH-a is associated with an initial surge of sex hormones and ovarian stimulation, followed by inhibition of the pituitary-gonadal axis and complete ovarian suppression (COS), if dosed appropriately. GnRH-a are part of the standard treatment of children with precocious puberty, women undergoing in-vitro fertilization, and for certain malignancies. Without known long-term side effects, some children with precocious puberty have been treated with weight-based doses of triptorelin exceeding 125 microgram/kg/bodyweight (BW) (9). Comparatively smaller doses of triptorelin have been used successfully in adult SLE patients for ovarian protection (10, 11). Given differences in growth and sexual maturation changes, and larger ovarian reserves in younger as compared to older females, the optimal dosing regimen of triptorelin to reliably provide COS is yet unknown (12).

The objectives of this study were to determine the dose of triptorelin that is sufficient to maintain COS between 4-weekly injections, and measure the time needed to achieve ovarian suppression after triptorelin initiation. We also strived to explore the safety of triptorelin when used in adolescent females with SLE.

METHODS

Study design and Participants

A multicenter double blinded randomized dose-escalation trial was conducted in seven tertiary pediatric rheumatology in the United States and one center in Brazil between September 2004 and July 2012. Patients were randomized 4: 1 to receiving either triptorelin (triptorelin pamoate; Trelstar®) or placebo in 4-weekly intervals intramuscularly during the 24-week cyclophosphamide induction therapy (Part 1), followed by cyclophosphamide in 6 to 12-weekly intervals during maintenance therapy or until cyclophosphamide was discontinued by the treating rheumatologist (Part 2). Only the first patient received triptorelin prior to CTX. Thereafter the protocol was changed to facilitate enrollment. For all other patients, the first dose of study drug (placebo, triptorelin) was given 4–6 days after the initial dose of cyclophosphamide. In Part 1, the triptorelin group was randomized to four different starting doses between 25 and 100 micrograms/kg BW. Subsequently, the triptorelin dose of individual females was escalated until COS or the maximum dose 150 microgram/kg BW (or 20 gram/dose) were reached. Patients were assessed with each study drug injection and cyclophosphamide infusion.

To be included in the trial, patients had to be female and fulfill ACR Classification Criteria for SLE before age 18 years (13), have entered puberty (as per Tanner breast stage 2 or higher) and be younger than 21 years at the time of enrollment. All patients had to have severe SLE organ involvement requiring cyclophosphamide-therapy as per the treating physician. Systemic contraceptives were prohibited as they influence hormonal measurements. Excluded were pregnant women or those who had received more than one dose of cyclophosphamide prior to enrollment, or with bone mineral density (BMD) at the lumbar spine at an age-adjusted z-score of less than −2.0 as measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA). Likewise, males with cSLE and pre-pubertal females were excluded from the study as GnRH-a do not seem to provide gonadal protection in such patients (also see supplemental Table 1) (14, 15).

Study proceedings were monitored by an independent data safety monitoring board. Ethics and human subjects’ approval was obtained from the individual Institutional Review Boards. All patients provided informed consent or, if under the age of consent, assent to participate in this study with permission by a legal guardian.

Randomization

Patients were randomized in a 4:1 fashion to receive either triptorelin or placebo. The starting doses of triptorelin (in microgram/kg BW) were at 25 (T1), 50 (T2), 75 (T3), 100 (T4) and based on prior use of triptorelin for precocious puberty and ovarian protection in adult women (16, 17). Randomization occurred by the Investigational Pharmacy at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital according to an independently developed randomization table with access only to the study pharmacists. Constructed by an independent epidemiologist who was excluded from any subsequent study activities, the randomization table allowed only for enrollment of patients to triptorelin in T1, followed by T2, T3 and T4.

Intervention

Both triptorelin and placebo (0.9% normal saline) were injected intramuscularly in a blinded fashion. Patients, study nurse, treating rheumatologists and investigators were all blinded to towards the group assignment and were not involved in study drug administration. Blinding of the patients and the nurse administering the study drug was achieved by covering the syringes in the pharmacy with an opaque foil.

All patients were treated using a standardized infusion protocol that featured cyclophosphamide starting doses at 500 mg/ m2body surface area (BCS) with the option for escalation up to 1,000 mg/m2BSA. Changes in cyclophosphamide dosage and background therapies were managed by the treating rheumatologist.

Study drug injections occurred every four weeks during cyclophosphamide-induction therapy. The triptorelin starting doses (T1–T4) were maintained if COS was achieved as determined by standard GnRH-stimulation test 27 days after injection (see Outcomes below). Otherwise, triptorelin dosing was increased by 25% or at least 20 microgram/kg every 4 weeks until COS was achieved (by GnRH-stimulation test) or the absolute maximum dose of 20 mg/dose was reached. Once COS was confirmed by GnRH-stimulation test, the weight-adjusted dose of triptorelin was kept stable during cyclophosphamide-therapy. Patients in the placebo group underwent GnRH-stimulation test after the initial dose of study drug only.

The study endocrinologist (SR), blinded to cSLE specific information but unblinded to the treatment arms, determined the presence of COS and communicated necessary changes in weight-based triptorelin dosing to the central investigational pharmacy.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was the dose of triptorelin that maintained COS confirmed by GnRH-stimulation test in at least 90% of the patients on day 27 following study drug injection. Based on GnRH-stimulation test, COS was considered to be present if levels of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) were less than 3 mIU/mL and 2 mIU/ml, respectively, when measured at 30 minutes after injection of 500 microgram subcutaneous leuprolide acetate (18). Secondary endpoints included time to ovarian suppression after the initial dose of triptorelin as assessed by unstimulated FSH and LH levels on days 7, 10, 15, 20, and 27 after study drug administration.

Unstimulated levels of FSH at less than 2 mIU/ml and LH at less than 1 mIU/ml were deemed reflective of ovarian suppression (19). In the setting of prior exposure to a gonadoxtoxin (first dose of cyclophosphamide), especially LH levels were deemed indicative of low ovarian function.

Ovarian function following cyclophosphamide-therapy

A menstruation diary was completed during the study. Ovarian reserve and function were assessed by serum levels of FSH, LH, estradiol and inhibin B at baseline and 3 or more months after discontinuation of triptorelin (20). These measurements were obtained on days 3–5 of the menstrual cycle or randomly in premenstrual females.

The serum levels of inhibin B during the early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (day 3–5) directly reflect the number of ovarian follicles with higher levels indicative of higher follicle numbers. Levels of FSH at 23 mIU/mL or higher; of LH at 15.9 mIU/mL or higher; and of estradiol lower than 37 pgram/mL were considered compatible with a postmenopausal state (21).

Safety

Safety assessments included serious adverse events (SAEs) and adverse events (AE) grade 3 or higher as per the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (Version 2), disease activity (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity 2k; SLEDAI-2k), damage (Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics Damage Index) (22); presence of depression (Child Depression Index, Beck’s Depression Index) (23, 24), and bone health (DEXA) was measured at screening and after induction therapy.

Statistical Analysis

The trial followed the recommendation of the CONSORT statement, and results are reported for all subjects who received at least one dose of study drug. Demographics and disease characteristics at baseline were summarized using descriptive statistics. Comparability of treatment groups with respect to the demographic and baseline characteristics were assessed by Student t-test for continuous variables, and a Fisher exact or Chi-square test for categorical variables, respectively.

The dose of triptorelin (weight-based and total) that was sufficient to maintain COS at day 27 post-injection in at least 90% of patients was determined by ranking triptorelin requirements for COS in the triptorelin group. In exploratory analyses, the relevance of renal function (creatinine, BUN), liver function (albumin, AST, ALT), cyclophosphamide dose, Tanner breast stage, and prednisone for the maintenance of COS was assessed using multivariate models.

We planned to enroll up to 50 patients. Based on data in adults (25) we assumed that none of the T2 patients but 75% of the T3 patients would achieve COS, Two-sided p-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were done using SAS (version 9.3; Cary, NC) and Microsoft Excel (version 2010; Redmond, WA).

Role of the Funding Source

Study medication and monitoring of the site in Brazil by a clinical trials organization were provided by Watson Pharmaceuticals. Funding was provided by a grant of the Office of Orphan Product Development at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA-R-00-2369; IND 64,520). The data management of the project was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number UL1TR000077.

RESULTS

Study Population

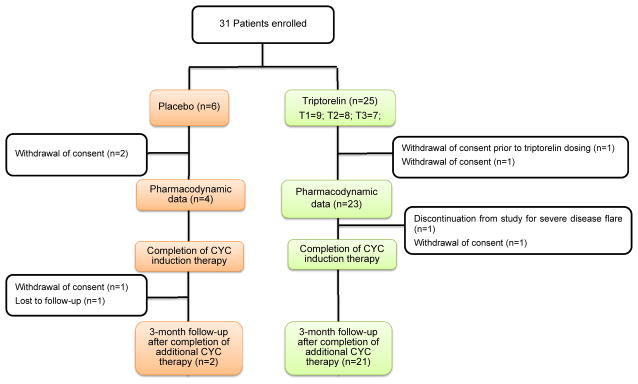

Figure 1 depicts the patient disposition. One patient randomized to triptorelin (T4) who withdrew consent prior to having received study drug was excluded from the statistical analysis. Serial unstimulated and stimulated serum levels of FSH and LH were available in 27 patients for assessing the pharmacodynamics of triptorelin, and 25 of the 30 patients completed cyclophosphamide induction-therapy (25/30=83%). The triptorelin and placebo groups were similar with respect to the baseline characteristics (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics of Patients with Follow-up Data

| Descriptors | Triptorelin | Placebo | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 23 | 6 | |

|

| |||

| Disease duration (years), mean ± SD | 1.3 ± 2.02 | 1.1 ± 2.05 | |

|

| |||

| Age (years); mean ± SD | 15.4 ± 2.70 | 17.8 ± 2.11 | |

|

| |||

| Race; n (% of N) | |||

| Black | 7 | 1 | |

| White | 14 | 5 | |

| Asian | 1 | - | |

| Other^ | 1 | - | |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity; n (% of N) | |||

| Hispanic | 10 | 4 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 13 | 2 | |

|

| |||

| Maturation Rating (Tanner); n (% of N) | |||

| Breast * (B2, B3, B4, B5) | 5,5,4,9 | -,-,1,5 | |

| Pubic * (P2, P3, P4, P5) | 6,4,5,8 | -,-,1,5 | |

|

| |||

| Disease Activity (SLEDAI); mean ± SD | 12.8 ± 5.56 | 10.7 ± 6.15 | |

|

| |||

| Disease Damage (SDI); mean ± SD | 0.3 ± 0.66 | 0.2 ± 0.45 | |

|

| |||

| Prednisone (mg/day); mean ± SD | 46.5 ± 24.3 | 50.0 ± 16.75 | |

|

| |||

| Indication for cyclophosphamide; n (% of N) | |||

| Renal Disease | 22 | 6& | |

| Neuropsychiatric Disease | 2 | ||

Biracial White and Black;

one patient also had both renal and neuropsychiatric disease requiring cyclophosphamide

Females with Tanner breast stage B1 were excluded from participation; pubarche had occurred in all subjects;

SLEDAI: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index;

SDI: Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/ American College of Rheumatology Damage Index.

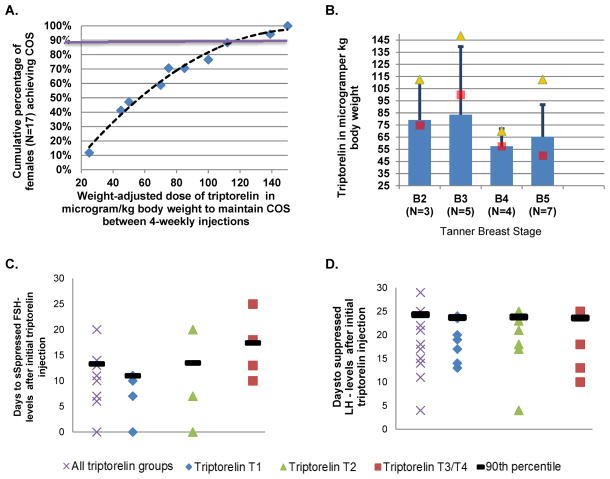

Dose to achieve COS

None of the patients in the placebo group achieved COS. Two patients randomized to receiving triptorelin discontinued the study before reaching COS (triptorelin dose: patient 1: 50 microgram/kg; patient 2 85 microgram/kg). Weight-adjusted (range 25 - 150 micrograms) and absolute (1.25 mg to 7.8 mg) triptorelin dosages needed for COS differed widely among patients. A weight-adjusted dose of 120 micrograms/kg BW resulted in sustained COS in 90% of the patients (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Triptorelin Dosages for achieving Complete Ovarian Suppression (COS)

Panel A. Weight-adjusted triptorelin dose for COS: To achieve COS pubertal girls with cSLE require widely varying dosages of triptorelin. To achieve COS in 90% of the girls 125 microgram/kg body weight were needed in the study population (purple line).

Panel B. Weight-adjusted dose of triptorelin dose by Sexual Maturation. There is a large variation in weight-adjusted triptorelin dosing among girls with cSLE.

■ Bar shows average weight-adjusted dose of triptorelin for COS

■ Median weight-adjusted dose of triptorelin needed for COS

▲ Maximum weight-adjusted dose of triptorelin needed for COS

Panel C. Days to COS as measured using suppressed FSH levels. Some females (n=3) maintained much suppressed FSH levels even after injection of triptorelin (Day 1). There may a trend of higher FSH levels after T3+4 dosing. When considering the entire population, 90% achieved suppressed unstimulated FSH levels (FSH < 2 mIU/mL) by Day 15, e.g. 2 weeks after the triptorelin injection

Panel D. Days to COS as measured using suppressed LH levels. The number of days needed to achieve suppressed unstimulated levels of LH after injection of triptorelin (Day 1) does not seem to differ based on the dose of triptorelin. When considering the entire population, 90% achieved suppressed unstimulated LH levels (LH <1 mIU/mL) by Day 24, e.g. 23 days after the triptorelin injection.

Human pharmacokinetic data suggest that triptorelin is either degraded completely within tissues, rapidly degraded in plasma, or cleared by the kidneys. Differences in triptorelin dosages needed to achieve COS were unrelated to patient body mass index, liver function status, kidney function, proteinuria, age, prednisone usage, or Tanner Stage (Figure 2b).

Time to COS after the initial dose of triptorelin

Initiation of GnRH-a is associated with transient ovarian activation prior to inhibiting ovarian function. Figures 2C/D depict the time to achieve suppressed levels of unstimulated FSH and LH, respectively. This was achieved in 90% of the triptorelin group with available data on day 14 and 22 days after the initial dose of triptorelin, without differences based on triptorelin starting dosages (T1-4).

Safety of triptorelin

During the study, the placebo and triptorelin groups were similar for cyclophosphamide-exposure (duration, cumulative dose) and prednisone usage (online supplemental Table 2). However, the average time-adjusted disease activity (SLEDAI-2k) was higher in the triptorelin group as compared to the placebo group (mean ± SD; 7.68±3.71 vs. 2.76±1.86; p=0.0165). No increases in SLEDAI-2k scores were noted after triptorelin discontinuation (data not shown).

A summary of AEs and SAEs are provided in Table 2. None of the AEs or SAEs led to study discontinuation. As expected in immunosuppressed patients, infections were common in both groups. Based on the limited information available for the placebo group, triptorelin was not associated with higher rates of AEs or SAEs. Additional details are provided in eTable 3.

Table 2.

Adverse Events, Grade III or higher & Serious Adverse Events

| Triptorelin (n=24) | Placebo (N=6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient months of follow-up | 439.9 | 47.1 |

|

| ||

| Number of patients with AE | 19 | 4 |

| Number of AE | 83 | 15 |

| AE per 100 patient month of follow-up | 189 | 362 |

|

| ||

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 4 | 1 |

| Infections & Infestations | 12 | 3 |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 1 | |

| Investigations | 8 | |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 2 | |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 7 | 1 |

| Nervous system disorders | 7 | 3 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 5 | 2 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 5 | 1 |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 5 | |

| Cardiac disorders | 1 | |

| Eye disorder | 1 | |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 5 | 1 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 10 | 1 |

| Vascular disorders | 10 | 2 |

|

| ||

| Number of patients with SAE | 8 | 3 |

| Number of SAE | 9 | 4 |

| SAE per 100 patient month of follow-up | 2.1 | 8.5 |

|

| ||

| General disorders and administration site conditions | Edema bilateral legs; Chest pain | |

| Infections & Infestations | Herpes zoster (2); Gastroenteritis (2); Cellulitis | Herpes zoster; Viral illness |

| Nervous system disorders | Organic brain syndrome | |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | Neutropenia | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | Cutaneous vasculitis | |

| Vascular disorders | Hypertension | |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | SLE Flare | |

Triptorelin therapy in the setting of high-dose corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide-therapy was associated with a decrease in DEXA at the lumbar spine in Z-score at −0.59 ± 0.56 and a decrease in BMD (in mg/cm2) of −0.19 ± 0.56 over a 9-month period. Change in BMD and Z-score were moderately associated with patient age, the cumulative dose of prednisone and triptorelin, respectively (Pearson correlation coefficients all 0.46 > |r| > 0.28; p = 0.039). Based on exploratory analysis of variance, younger age (standardized beta coefficient [STB] +0.41) and triptorelin cumulative dose (STB = −0.24) were the most important predictors of the decrease in Z-score as compared to the cumulative dose of prednisone (STB = −0.052).

We did not observe differences in depression summary scores at baseline or over time between groups nor any worsening of depression after initiation of triptorelin. There was no clear association between the dose of triptorelin and the frequency of AEs or SAEs.

Preliminary efficacy

The study was not powered to show efficacy of triptorelin for ovarian protection. Follow-up data post discontinuation of cyclophosphamide and triptorelin were available for 21 females. Ovarian function preservation in these females is based on several surrogate measures (Table 3). Menses resumed in all patients who had been menstruating prior to cyclophosphamide initiation. None of the females had FSH, LH or E2 levels compatible with post-menopause. Inhibin B levels were supportive of maintained ovarian reserve.

Table 3.

Ovarian Function 3 months post completion of the study in 21 patients on triptorelin†

| Baseline | End of study visit | |

|---|---|---|

| Days after last triptorelin injection | 246 ± 233 | |

| Tanner Breast Stage (B2, B3, B4, B5) | 5,5,4,9 | -,4,3,14 |

| LH levels (in mIU/mL) | 5.2 ± 7.58 | 7.5 ± 16.23 |

| FSH levels (in mIU/mL) | 4.1 ± 3.59 | 6.1 ± 1.73 |

| FSH levels > 40 IU/L | 0 | 0 |

| Inhibin B (in pgram/mL) | 125.1 ± 188.04 | 179.5 ± 190.86 |

| Estradiol (in pgram/mL) | 65.8 ± 45.46 | 99.7 ± 179.83 |

| Menses present (yes/no) | Present: 16; Premenstrual:5 | Present: 16; Premenstrual:5 |

| SDI‡ | 0.3 ± 0.66 | 0.4 ± 1.16 |

Values are means (standard deviations) unless state otherwise

SDI: Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/ American College of Rheumatology Damage Index

DISCUSSION

In this double blind placebo-controlled dose escalation trial we showed that higher doses of triptorelin than previously suggested for adult women are needed to induce COS in adolescent females with cSLE. Indeed, intramuscular triptorelin at 120 microgram/kg induce and maintain COS between injections given every 28 days in almost all females, and thus likely provide ovarian protection. Triptorelin in this study was well tolerated. Notably, 22 days are needed to induce COS in most young females with cSLE after an initial dose of triptorelin.

cyclophosphamide crosslinks DNA, damaging the chromosomes of rapidly dividing cells. cyclophosphamide primarily affects the function of granulosa cells of primordial follicles, suppressing estrogen production and stimulating gonadotropin release (FSH, LH), which initiates the recruitment of a new cohort of follicles to develop (26). This process greatly increases the number of follicles vulnerable to the toxic effects of cyclophosphamide, ultimately resulting in accelerated maturation and depletion of the ovaries (26). The GnRH-a triptorelin can induce COS and has been found effective to preserve ovarian function in older females requiring cyclophosphamide (8), with the exact mechanisms still being investigated (14).

Our study suggests that adolescent and young adults often need high doses of triptorelin to maintain COS. This observation is in line with reports from children with precocious puberty who frequently require similar doses as those given in this study (27).

The wide variation in the dose of triptorelin needed to achieve COS and the association of higher doses of triptorelin with higher loss of bone, support that individualized dosing should be considered, based on GnRH-stimulation test. Associations of triptorelin or other GnRH-a with increased bone loss are widely described in the literature (28). Sufficiently high dosing of triptorelin seems essential for its gonadoprotective effect. This is supported by the results of a recent trial where 11.25 mg of the 3-month depot preparation of triptorelin was given to females randomized to the active treatment arm. This study found no difference in the frequency of premature ovarian failure 1-year post completion of cyclophosphamide between the triptorelin group and the placebo group (29).

Besides adequate dosing of triptorelin, avoidance of cyclophosphamide administration during times of ovarian stimulation appears important. Based on limited experience in adult women, COS can be induced within about 2 weeks using 1.9 – 7.5 mg of triptorelin (25). Little is known about the time to suppress ovarian function in children treated with triptorelin. To the best of our knowledge, we newly provide data that suggest that 22 days are required to yield ovarian suppression in the vast majority of adolescents after an initial dose of triptorelin. Thus consideration should be given to inject the initial dose of triptorelin 4–6 days after cyclophosphamide infusion, i.e., at a time the medication has been eliminated.

Patients participating in this study tolerated often high doses of triptorelin well. Based on limited placebo data, triptorelin was not associated with higher rates of AEs or SAEs. Interestingly, we found that the disease activity in the triptorelin group was higher than that in the placebo which was unexpected as low estrogen-states as present with COS, are thought to be associated with lower SLE activity (30).

A shortcoming of our study is limitation in sample size and limited data available from the placebo group. Double-blind placebo controlled studies are difficult to perform in pediatrics in general and in a group of adolescents with severe SLE requiring cyclophosphamide in particular. Furthermore, the primary objective of the study was to establish a triptorelin dosing regimen that results in COS with cSLE seems achieved. Overt ovarian failure with cyclophosphamide is rare among young females with and without cSLE. Our study does not provide direct evidence about the degree of ovarian protection with triptorelin compared to placebo. However, GnRH-a have been found beneficial for ovarian protection with various disease requiring cyclophosphamide, and the ovarian reserve of the triptorelin group seemed preserved upon completion of cyclophosphamide (14, 17).

The patients enrolled in the study were typical in a sense that cyclophosphamide is most commonly used in cSLE for induction therapy of proliferative lupus nephritis. Hence, we believe that the results of this study are generalizable to other cSLE populations and probably applicable to other adolescent females requiring intravenous cyclophosphamide-therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number UL1TR000077.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

None of the authors perceive to have a conflict of interest relevant to the conduct of this study.

Drs. Brunner and Rose had fully access to all data in the study and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Denise Lagory for her services as Director of the CCHMC Investigational Pharmacy

Cathy McGraw for the development of the database

Ms. Anne Johnson and Dr. Patricia Vega-Martinez for data cleaning

Neusa Keiko Sakita co-investigator of Pediatric Rheumatology Unit and Rheumatology Division, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil for data collection and management

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Contributor Information

Hermine I. Brunner, Email: hermine.brunner@cchmc.org, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, USA.

Clovis A Silva, Email: clovis.silva@hc.fm.usp.br, Pediatric Rheumatology Unit and Rheumatology Division, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Andreas Reiff, Email: areiff@chla.usc.edu, Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA.

Gloria C. Higgins, Email: gloria.higgins@nationwidechildrens.org, Nationwide Children’s Hospital and The Ohio State University, Columbus, USA.

Lisa Imundo, Email: lfi1@columbia.edu, New York Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University Medical Center, New York, USA.

Calvin B. Williams, Email: cbwillia@mcw.edu, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, USA.

Carol A Wallace, Email: cwallace@u.washington.edu, Seattle Children’s Hospital, University of Washington; Seattle, USA.

Nadia E. Aikawa, Email: nadia.aikawa@gmail.com, Pediatric Rheumatology Unit and Rheumatology Division, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil, São Paulo.

Shannen Nelson, Email: Shannen.Nelson@gmail.com, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, USA.

Marisa S. Klein-Gitelman, Email: klein-gitelman@northwestern.edu, Ann and Robert Lurie Hospital, Northwestern University, Chicago, USA.

Susan R. Rose, Email: susan.rose@cchmc.org, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, USA.

References

- 1.Fernandes Moca Trevisani V, Castro AA, Ferreira Neves Neto J, Atallah AN. Cyclophosphamide versus methylprednisolone for treating neuropsychiatric involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013;2:CD002265. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002265.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mina R, von Scheven E, Ardoin SP, Eberhard BA, Punaro M, Ilowite N, et al. Consensus treatment plans for induction therapy of newly diagnosed proliferative lupus nephritis in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis care & research. 2012;64(3):375–383. doi: 10.1002/acr.21558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koo HS, Kim YC, Lee SW, Kim DK, Oh KH, Joo KW, et al. The effects of cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate on end-stage renal disease and death of lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2011;20(13):1442–1449. doi: 10.1177/0961203311416034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ioannidis JP, Katsifis GE, Tzioufas AG, Moutsopoulos HM. Predictors of sustained amenorrhea from pulsed intravenous cyclophosphamide in premenopausal women with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(10):2129–2135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manger K, Wildt L, Kalden JR, Manger B. Prevention of gonadal toxicity and preservation of gonadal function and fertility in young women with systemic lupus erythematosus treated by cyclophosphamide: the PREGO-Study. Autoimmunity reviews. 2006;5(4):269–272. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva CA, Brunner HI. Gonadal functioning and preservation of reproductive fitness with juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2007;16(8):593–599. doi: 10.1177/0961203307077538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Isgro J, Nurudeen SK, Imundo LF, Sauer MV, Douglas NC. Cyclophosphamide exposure in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus is associated with reduced serum anti-mullerian hormone levels. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(6):1029–1031. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.130017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenfeld Z, Mischari O, Schultz N, Boulman N, Balbir-Gurman A. Gonadotropin releasing hormone agonists may minimize cyclophosphamide associated gonadotoxicity in SLE and autoimmune diseases. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2011;41(3):346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Gool SA, Kamp GA, Visser-van Balen H, Mul D, Waelkens JJ, Jansen M, et al. Final height outcome after three years of growth hormone and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment in short adolescents with relatively early puberty. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2007;92(4):1402–1408. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blumenfeld Z, Shapiro D, Shteinberg M, Avivi I, Nahir M. Preservation of fertility and ovarian function and minimizing gonadotoxicity in young women with systemic lupus erythematosus treated by chemotherapy. Lupus. 2000;9(6):401–405. doi: 10.1191/096120300678828596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somers EC, Marder W, Christman GM, Ognenovski V, McCune WJ. Use of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog for protection against premature ovarian failure during cyclophosphamide therapy in women with severe lupus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2005;52(9):2761–2767. doi: 10.1002/art.21263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinha R, Dionne JM. Should gonadotropin releasing hormone analogue be administered to prevent premature ovarian failure in young women with systemic lupus erythematosus on cyclophosphamide therapy? Archives of disease in childhood. 2008;93(5):444–445. doi: 10.1136/adc.2007.131334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1997;40(9):1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva CA, Bonfa E, Ostensen M. Maintenance of fertility in patients with rheumatic diseases needing antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62(12):1682–1690. doi: 10.1002/acr.20323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahlou N. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of triptorelin. Annales d’urologie. 2005;39 (Suppl 3):S78–84. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4401(05)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Magiakou MA, Manousaki D, Papadaki M, Hadjidakis D, Levidou G, Vakaki M, et al. The efficacy and safety of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog treatment in childhood and adolescence: a single center, long-term follow-up study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2010;95(1):109–117. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blumenfeld Z, Dann E. GnRH agonist for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure in lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3721. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.8222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sathasivam A, Garibaldi L, Shapiro S, Godbold J, Rapaport R. Leuprolide stimulation testing for the evaluation of early female sexual maturation. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2010;73(3):375–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2010.03796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenfield RL, Bordini B, Yu C. Comparison of detection of normal puberty in girls by a hormonal sleep test and a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist test. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2013;98(4):1591–1601. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Randolph JF, Jr, Harlow SD, Helmuth ME, Zheng H, McConnell DS. Updated assays for inhibin B and AMH provide evidence for regular episodic secretion of inhibin B but not AMH in the follicular phase of the normal menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(3):592–600. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.ACM Medical Laboratory Reference Manual. [ http://referencemanual.acmlab.com/]

- 22.Brunner H, Silverman E, To T, Bombardier C, Feldman BM. Risk Factors for Damage in Childhood-Onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Cumulative Disease Activity and Medication Use Predict Disease Damage. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2002;45 doi: 10.1002/art.10072. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression, Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21(4):995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. J Pers Assess. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Leudsen H. Dose response of decapeptyl depot using three dosage regimens in gynecological patients (Study 45 CO2/PR/15) Ferring Internat Report. 1993 Jul 30;1993 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harward LE, Mitchell K, Pieper C, Copland S, Criscione-Schreiber LG, Clowse ME. The impact of cyclophosphamide on menstruation and pregnancy in women with rheumatologic disease. Lupus. 2013;22(1):81–86. doi: 10.1177/0961203312468624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Partsch CJ, Sippell WG. Treatment of central precoccious puberty. Best Pract Res Endocrinol. 2002;16(1):165–189. doi: 10.1053/beem.2002.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasquino AM, Pucarelli I, Accardo F, Demiraj V, Segni M, Di Nardo R. Long-term observation of 87 girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty treated with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs: impact on adult height, body mass index, bone mineral content, and reproductive function. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;93(1):190–195. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demeestere I, Brice P, Peccatori FA, Kentos A, Gaillard I, Zachee P, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure in patients with lymphoma: 1-year follow-up of a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(7):903–909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mok CC, Wong RW, Lau CS. Ovarian failure and flares of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(6):1274–1280. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199906)42:6<1274::AID-ANR26>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.