Abstract

Pediatric-onset ataxias often present clinically with developmental delay and intellectual disability, with prominent cerebellar atrophy as a key neuroradiographic finding. Here we describe a novel clinically distinguishable recessive syndrome in 12 families with cerebellar atrophy together with ataxia, coarsened facial features and intellectual disability, due to truncating mutations in sorting nexin 14 (SNX14), encoding a ubiquitously expressed modular PX-domain-containing sorting factor. We found SNX14 localized to lysosomes, and associated with phosphatidyl-inositol (3,5)P2, a key component of late endosomes/lysosomes. Patient cells showed engorged lysosomes and slower autophagosome clearance rate upon starvation induction. Zebrafish morphants showed dramatic loss of cerebellar parenchyma, accumulated autophagosomes, and activation of apoptosis. Our results suggest a unique ataxia syndrome due to biallelic SNX14 mutations, leading to lysosome-autophagosome dysfunction.

The hereditary cerebellar ataxias are a group of clinical conditions presenting with imbalance, poor coordination, and atrophy/hypoplasia of the cerebellum, most often with deterioration of neurological function. A common hallmark of cerebellar ataxias is a progressive cerebellar neurodegeneration due to Purkinje cell loss. A combination of dominant, recessive and X-linked forms of disease, including the spinocerebellar ataxias, Friedreich ataxia, and ataxia telangectasia contribute to the estimated prevalence of 8.9 per 100,0001. In addition to the dominant trinucleotide repeat disorders that lead to toxic accumulation of unfolded protein2, 3, the recessive forms of disease are associated with inactivating mutations and early-onset presentations. The genes implicated to date suggest defects in neuronal survival pathways4, 5, but many mechanisms are still lacking and most patients elude genetic diagnosis.

Recessive ataxias often show clinical overlap with lysosomal disorders, and in fact, many lysosomal diseases such as Niemann-Pick, Tay-Sachs, and I-cell disease show evidence of Purkinje cell loss and clinical features of ataxia, in addition to the well established features of enlarged organs and coarsening of facial features6–8. These overlaps suggest that cerebellar cells are exquisitely sensitive to otherwise generalized perturbations of lysosomal function.

Autophagy is the major pathway for intracellular catabolic degradation of most long-lived proteins and organelles, thus providing nutrients during starvation9. When core components are impaired, the result is multisystem organ involvement that includes neurodegeneration9–13. In the major pathway, termed macroautophagy, the autophagosome fuses with multivesicular body (MVB) or the lysosome, and the contents are degraded via acidic hydrolases. The fusion events are at least partially regulated by the phosphatidyl-inositol (PI) lipid components of the respective membranes, with PI(3)P associated with autophagosomes and PI(3,5)P2 associated with MVBs and lysosomes14. Yet the proteins regulating these relatively late-stage fusion events are mostly unknown.

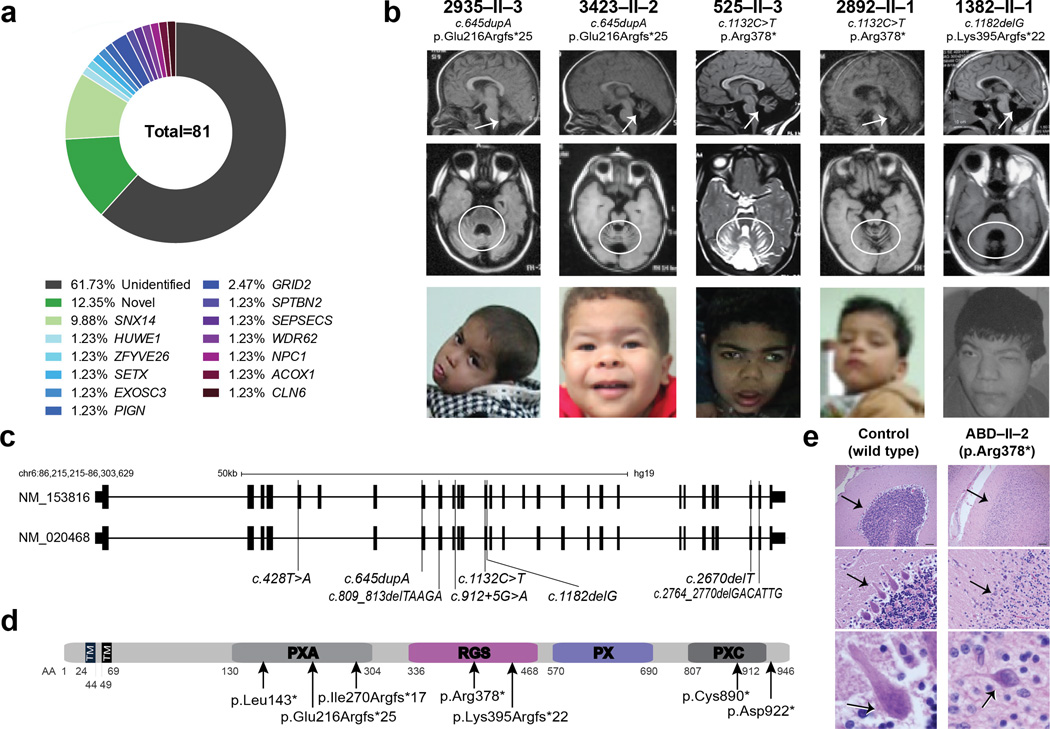

We studied a cohort of 96 families presenting with likely autosomal childhood-onset recessive cerebellar atrophy with ataxia, 81 of which had a history of parental consanguinity, and 76 of which had two or more affected members without congenital malformations or environmental risk factors. We performed whole exome sequencing (WES) on at least one member of each of the families, according to published protocols15. For families with documented consanguinity, we prioritized homozygous, rare (<0.2% allele frequency in our in-house exome database of 3000 individuals) and potentially damaging variants (Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profile (GERP) score >4 or phastCons (genome conservation) >0.9). Many of the families displayed damaging mutations in genes already implicated in cerebellar atrophy, including NPC1, and GRID2. Overall, 15% of cases showed mutations in genes that fully explained their presentation (Supplementary Table 1), 60% of families showed no obvious candidates, and 25% displayed putative mutation in a gene or genes not previously implicated in human disease (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1. SNX14 mutations cause a syndromic form of severe cerebellar atrophy and coarsened facial features.

(a) Summary of exome results from 81 families with cerebellar atrophy. SNX14 accounted for 9.88% of the total families, with other genes making individual contributions. (b) Midline sagittal (top) or axial (middle) MRI and facies of affected individuals from representative families. Prominent atrophy of cerebellum evidenced by reduced volume and apparent folia (arrows and circles). Facies show prominent forehead, epicanthal folds, long philtrum and full lips. Consent to publish images of the subject was obtained. (c) SNX14 exons as ticks and location of mutations indicated. Scale bar 50 kb. (d) Truncating mutations relative to predicted protein domains. TM: Transmembrane, PXA: Phox homology associated, RGS: Regulator of G protein signaling, PX: Phox homology, PXC: Sorting Nexin, C-terminal. (e) ABD-II-2 (p.Arg378*) hematoxylin-eosin stained cerebellum compared with control showing reduction in internal granule cell layer (arrow, top), near complete depletion of Purkinje cells (arrow, middle), and dystrophic degenerating remnant Purkinje cell (arrow, bottom). Scale bar 100 µm.

To identify causative mutations, we focused on Family 468, with three similarly affected and one healthy child, which allowed for parametric linkage analysis, defining a single major locus between chr6:55153677-91988281 (hg19) (LOD = 2.528) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Alignment of all LOD > -2 loci with WES from two affecteds highlighted a single c.1132C>T variant in the SNX14 gene predicting a p.Arg378*. Turning our attention to this gene from the remaining WESed patients, we identified a total of 16 patients from 8 families with truncating variants throughout the coding region, nearly all in constitutively spliced exons, and predicted as loss of function (Fig. 1b-d, Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2). All patients displayed a block of homozygosity on chromosome 6, containing the SNX14 gene (Supplementary Fig. 1) and mutations segregated according to a recessive mode of inheritance. Variants in other genes in these patients were either previously described SNPs in other populations or were of unknown significance (Supplementary Table 3). Three families shared the same p.Arg378* mutation and analysis confirmed a common 1.5 mb haplotype, supportive of a founder mutation (Supplementary Fig. 1). Overall, patients with SNX14 variants accounted for 10% of families, making it the single most commonly mutated gene in our cohort. Furthermore, while preparing this manuscript, WES from an additional consanguineous family with 4 children with cerebellar atrophy independently identified a homozygous truncating mutation in SNX14 (Supplementary Fig. 2).

SNX14 encodes 946 amino acids, and contains two transmembrane domains, a regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) domain, predicted to act as a GTPase activating protein (GAP) and a phox homology (PX) domain predicted to bind phosphoinositide lipids and function in intracellular trafficking. Alternate splicing results in transcript variants encoding distinct isoforms. Patient SNX14 variants predicted both early and late truncating events, suggesting loss of function as the disease mechanism (Fig. 1c-d).

Patients showed several common features in addition to the age-dependent atrophy of the cerebellum, with evidence of cerebral cortical atrophy in about half (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 4). One deceased patient studied neuropathologically showed near absence of Purkinje cells. The few Purkinje cells remaining were ectopically located and atrophic with enlarged apical neurites. Bergmann gliosis was prominent in the depopulated Purkinje cell layer and neurofilament immunostaining revealed radially oriented bundles of distended axons located on the superficial part of the internal granule layer. Forebrain also presented neuronal loss although less severe than in the cerebellum (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Clinical findings in SNX14 mutated individuals. (See Supplemental Table 4 for detailed clinical information).

| Development | Percent of patients displaying feature |

|---|---|

| Delayed gross motor | 22/22 |

| Delayed fine motor | 22/22 |

| Delayed or absent language | 22/22 |

| Delayed or absent social | 22/22 |

| Autistic-like behavior | 12/22 |

| Neurological Findings | |

| Epileptic Seizures | 8/22 |

| Hypotonia | 22/22 |

| Nystagmus | 11/22 |

| Gait wide based or absent | 22/22 |

| Cerebellar atrophy on brain MRI | 22/22 |

| Storage disorder phenotype | |

| Coarse facies | 22/22 |

| Hearing loss (SNHL) | 5/22 |

| Kyphoscoliosis, clinodactyly | 10/22 |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | 5/22 |

| Hypertrichosis | 12/22 |

| Macroglossia | 12/22 |

| Atrial septal defect or patent ductus | 2/22 |

| Urine oligosaccharides or glycosylaminoglycans | 5/22 |

Most patients presented between birth and 1 year of age with global developmental delay and hypotonia. Seizures developed in half by 2 years, and were well controlled with anticonvulsant medication. Nystagmus, difficulty ambulating and reduced deep tendon reflexes were seen in most children, and sensorineural hearing loss was seen in about one third. Coarsened facial features with prominent forehead, epicanthal folds, upturned nares, long philtrum, and full lips were seen in all, features approximating mucopolysaccharidosis or other lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs) (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Likewise, ultrastructural analysis of spinal cord tissue found axonal spheroids filled with membranous structures reminiscent of cytoplasmic membranous bodies in LSDs16 (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Palpable liver or spleen edge was detected in 5 of 18 patients, but no evidence of abnormal liver, urine or hematological chemistries were apparent. Urine oligosaccharides showed an abnormal pattern in one affected, and two patients showed elevated urinary glycosoaminoglycans. However detailed lysosomal enzyme analysis in plasma and leukocytes from two affected members proved unremarkable (Supplemental Note). Although initially WES was required to identify patients, as the clinical presentation clarified, we were able to predict mutations with 100% certainty, identifying an additional 4 patients from 3 families with homozygous SNX14 mutations, suggesting a, heretofore unknown, clinically recognizable condition (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 2).

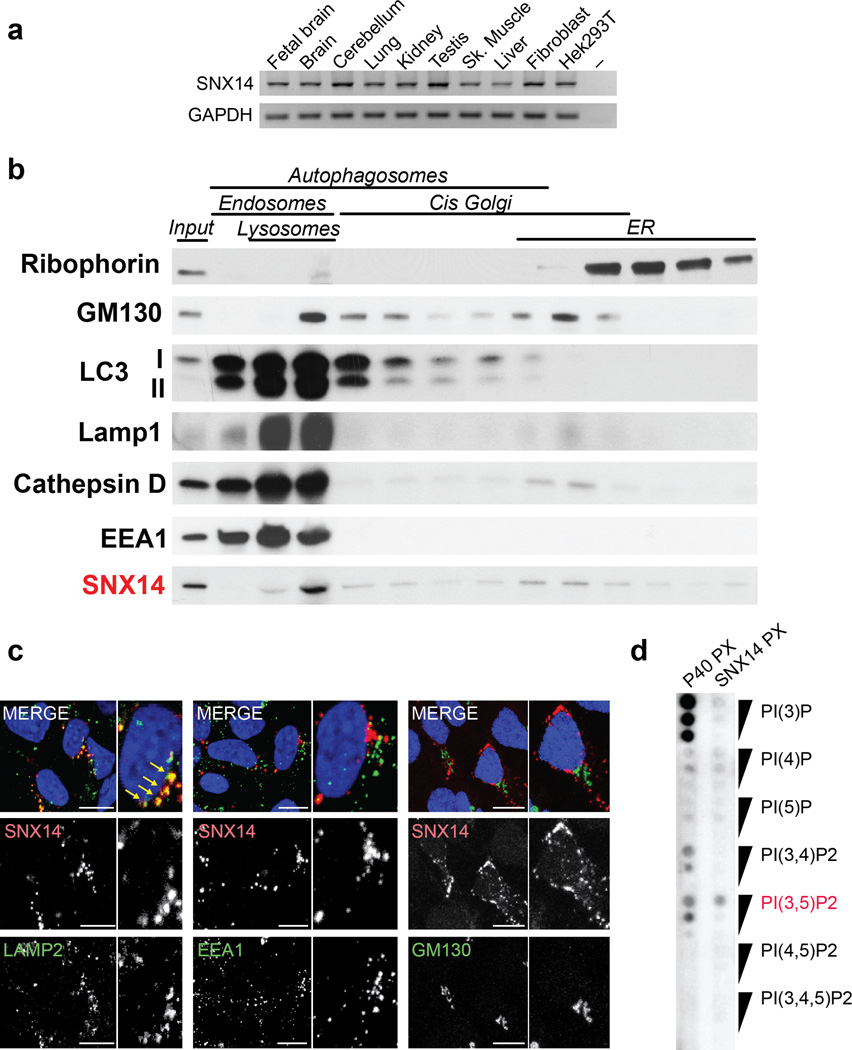

SNX14 mRNA showed nearly uniformly even expression in human fetal and adult tissue (Fig. 2a). Cellular fractionation aimed to distinguish the major membrane-bound pools in wildtype human neural precursor cells identified SNX14 predominantly associated with a lysosomal rich fraction (Fig. 2b). Tagged SNX14 overexpression confirmed overlapping localization with lysosomes (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 4), but not with other endosomal or Golgi markers that were present in the SNX14 fraction, suggesting a role in lysosomal function. Furthermore, lipid binding assay with the recombinant PX domain from SNX14 showed specific albeit relatively weak direct binding with PI(3,5)P2, the predominant phosphoinositide (PI) associated with lysosomes (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. SNX14 localizes to late endosome/lysosome compartments.

(a) RT-PCR expression pattern of human SNX14 showing ubiquitous expression in representative fetal and adult human tissues. GAPDH: loading control. (b) Cell fractionation from human neural progenitor cells (NPCs). SNX14 was enriched in lysosomal-endosomal compartments (red). (c) LAMP2, EEA1 and GM130 (green) in dsRED tagged SNX14 expressing NPCs. SNX14 overlapped in localization with LAMP2 lysosomal marker (arrows). Scale bar 10 µm. (d) Lipid binding assay with SNX14 PX domain on phosphoinositides-spotted membrane, showed preferential binding to PI(3,5)P2 (red), compared with p40phox PX domain control.

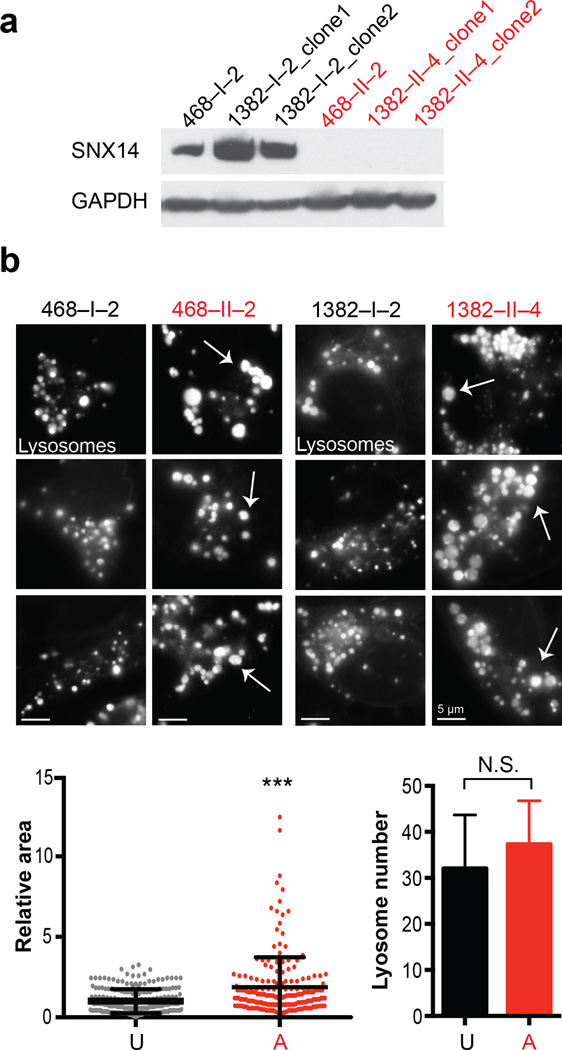

To identify lysosomal defects associated with SNX14 mutations, we generated induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs) and then differentiated neural precursor cells (NPCs) through reprograming of SNX14 patients and control fibroblasts from families 468 and 138217, 18. Like the patient fibroblasts, SNX14 protein was absent from patient NPCs (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 5). While we noted no difference in reprogramming, differentiation or cellular survival in culture (Supplementary Fig. 5), lysosomes appeared increased in size in patient NPCs (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 6). To quantitate this effect, we performed flow cytometric analysis to gate for fluorescent signal upon Lysotracker labeling, and found about twice the number of patient cells falling outside of the normalized intensity distribution (Supplementary Fig. 6a).

Figure 3. Patient-derived SNX14 mutant neural progenitor cells display enlarged lysosomes.

(a) Immunoblot of IPSC-derived neural progenitor cells (NPCs) from families 468 (p.Arg378*) and 1382 (p.Lys395Argfs*22), with affected (A, red) and unaffected (U, black) labeled. Affecteds showed undetectable SNX14 protein. GAPDH: loading control. (b) Lysotracker Green DND-26 staining with engorged lysosomes in affecteds NPCs (arrows). Scale bar 5 um. Dot plot shows relative area for individual LysoTracker positive lysosomes (n = 223 and 194 lysosomes from 2 families unaffected and affected NPCs respectively, N = 2). Graph bars represent average number of LysoTracker-positive lysosomes per cell (n = 17 and 18 from 2 families unaffected and affected NPCs respectively, N = 2). Error bars, S.D. *** p < 0.0005, N.S. not significant (two tiled t-test).

In order to assess if this lysosomal enlargement affected lysosomal activity, we tested NPCs for active Cathepsin D (which depends upon both lysosomal localization of the enzyme and acidification), using Bodipy FL Pepstatin A19 and found no obvious differences in intensity of stained lysosomes (Supplementary Fig. S6d). However immunoblot analysis detected slight but significant reduction in Cathepsin D levels in affected compared to unaffected NPCs (Supplementary Fig. 7c), suggesting that a fraction of lysosomes may be defective for Cathepsin D. Although defects in other lysosomal enzyme activities were not tested in NPCs, our findings are reminiscent of lysosomal storage disorders (LSDs).

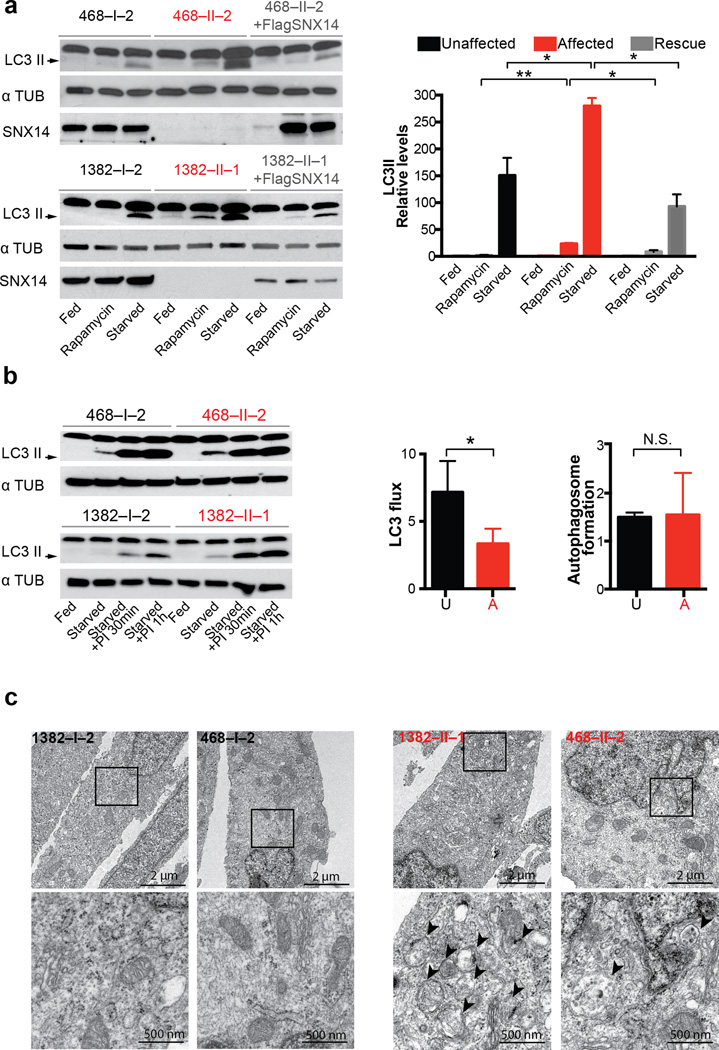

Autophagy requires fusion of lysosomes with autophagosomes, so lysosomal abnormalities could result in autophagic defects such as those observed in LSDs6–8. In order to test for potential autophagic defects, patient NPCs were cultured under starvation conditions, then assessed for lipidated LC3 (i.e. LC3 II) levels, which marks autophagosomes. While all lines showed increased LC3 II levels upon serum starvation, patient cells showed a more dramatic response, which was reproduced by an alternative induction of autophagy through mTOR pathway inhibition with rapamycin. Importantly, the increased LC3 II levels were recovered to basal rates by forced expression of tagged SNX14 into patient cells (Fig. 4a). By LC3 flux analysis in nutrient deprived conditions, where LC3II ratios in the presence and absence of lysosomal inhibitors (Leupeptin and NH4Cl) were calculated20, we identified slower LC3 flux in patient cells compared to controls. This, together with no differences observed in autophagosome formation (assessed as the increase in LC3-II levels at two time points after inhibition of lysosomal proteolysis, Fig. 4b), suggests that SNX14 mutant neural progenitors are defective in autophagosome clearance. To confirm, we performed electron microscopy and found that patient cells show autophagosome accumulation (Fig. 4c), consistent with disrupted autophagosome clearance.

Figure 4. Patient-derived SNX14 mutant neural progenitor cells display abnormal starvation-induced autophagic response.

(a) Immunoblot analysis of LC3 II in affected (red), unaffected and affected transduced with SNX14 (grey) NPCs upon induction of autophagy by starvation with 1 hr 30 min EBSS (Eagle’s Balanced Salt Solution) or rapamycin (1 µM for 2 hr). Graph bars represent average LC3II/αTubulin levels relative to feeding condition. Error bars S.D. (N = 3 clones) * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, N.S. not significant (two tiled t-test). Affected cells display an accumulation of LC3 II levels upon autophagic induction, partially rescued by exogenous SNX14 expression. (b) LC3 immunoblot (left) for quantification of autophagic flux measured by LC3 II ratio in lane 3 vs. lane 2 for unaffected and lane 7 vs. lane 6 for affected (red) (middle), and quantification of autophagosome formation (left) assessed as the increase in LC3-II levels at two time points (lane 4 vs. lane 3 for control, and lane 8 vs. lane 7 for affected) after inhibition of lysosomal proteolysis with Leupeptin 200 µM and NH4Cl 20 mM (PI 30 min/PI 1 hr). Graph represent mean ± S.D. (N = 3 clones) * p < 0.05, N.S. not significant (two tailed t-test) (c) Transmission electron microscopic analysis of 2 hr EBSS treated unaffected (black) and affected (red) NPCs showing autophagic structures in affecteds (arrowheads). Data represents results from one NPC clones from each affected or unaffected.

We thus repeated the cell fractionation analysis upon serum starvation to induce autophagy, and observed SNX14 enriched in the most heavily LC3-lipidated fractions (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Furthermore, upon serum starvation, SNX14 showed overlapping immunofluorescence localization with LC3 (Supplementary Fig. 7b), suggesting at least some fraction of SNX14 associates with autophagic structures, consistent with a role in autophagosome clearance.

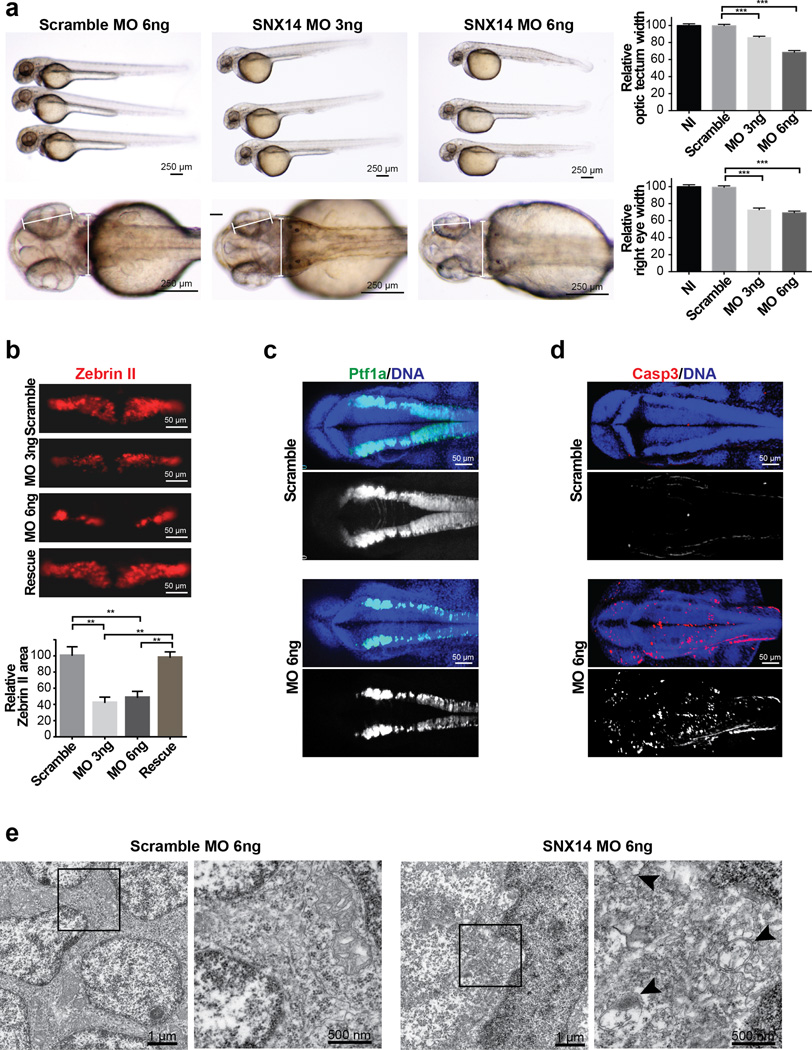

In order to demonstrate the role of SNX14 in cerebellar function, we established an in vivo zebrafish model, where we found a single snx14 ortholog (NM_001044793), with strong neural expression (Supplementary Fig. 8). Injection of a specific snx14 translation blocking morpholino resulted in loss of neural tissue volume (Fig. 5a). Immunostaining of these embryos for Zebrin II, an early Purkinje cell marker, showed significantly reduced cellular area, an effect that was quantifiably rescued by co-injection with the human SNX14 ortholog (Fig. 5b). Morpholino injection into the Tg(ptf1a:EGFP) zebrafish line, which expresses GFP in the hindbrain21, confirmed overall reduction in GFP intensity (Fig. 5c) and suggested SNX14 is required for hindbrain and Purkinje cell generation or survival. To distinguish between these possibilities, we performed staining for activated caspase 3, and found a dramatic increase in signal throughout the assessed neural tissue. Transmission electron microscopy analysis of neural cells demonstrated accumulation of autophagic structures in snx14 morphants. These data suggests that SNX14 mutations leads to neuronal cell death associated with impaired autophagic degradation.

Figure 5. Morphant snx14 zebrafish show apoptosis, excessive autophagic vesicles, and loss of neural tissue including cerebellar primordium.

(a) Comparison of scrambled (6ng) and snx14 (3ng and 6ng) morphant zebrafish 48 hours postfertilization (hpf). Calipers: measured distance. Scale bar 250 µm. Graphs: Reduced optic tectum and right eye width in morphants. Mean ± SEM (n = 15 embryos for NI, 16 for Scramble, 31 for MO 3ng and 18 for MO 6ng, N = 2). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005 (two tiled t-test). (b) Scramble or snx14 morphants for Zebrin II (Purkinje cell marker), rescued with human SNX14 (50 pg). Scale bar 50 µm. Graph: Zebrin II compartment area relative to scramble MO injected embryos. Mean ±SEM (n = 10 embryos for Scramble, 6 for MO 3ng, 9 for MO 6ng and 9 for rescue) *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005 (two tiled t-test). (c) Maximum confocal projection from 36 hpf Tg(ptf1a:eGFP) (green) zebrafish with scramble or snx14 MO showing reduced Purkinje cell progenitors. (d) Maximum confocal projection with increased caspase 3 (red) positive cells in 36 hpf snx14 morphants. Blue: DAPI. Scale bar 50 µm. (e) Transmission electron microscopy showing autophagic structures in 48 hpf snx14 and scrambled morphant neurons residing between the optic lobes. Box: Highlighted areas. Arrowheads: autophagic structures.

In summary, we have characterized a cerebellar ataxia syndrome (SCAR17), caused by null mutations in SNX14. Our paper adds to the recent report of cerebellar atrophy with intellectual disability and coarse facies also showing homozygous SNX14 mutations22. Our work, with the addition of a larger cohort, helps identify clinical features that are variable, such as camptodactyly, macrocephaly, and epilepsy and delineate the common pathology clearly distinguishable from other ataxias confirming this as a novel syndrome as suggested23.

Our study identifies the association of SNX14 with autophagy and neurodegeneration. Currently, of the 30 or so SNX genes in humans, only SNX10 is linked to human Mendelian disease, with a homozygous mutation in a single family with malignant infantile osteopetrosis24. Other SNX proteins are suggested to play roles in synaptic function25, 26, and neuronal survival especially relevant in Alzheimer’s disease27–30 through their function in cargo sorting, but SNX14 is the first to be genetically implicated. We propose a role for SNX14 mediating fusion of lysosomes with autophagosomes, an area of intense research, and through manipulation of autophagy, may provide a promising therapeutic target currently under investigation for other degenerative conditions31.

ONLINE METHODS

Patient Ascertainment

Patients were enrolled and sampled according to standard local practice in approved human subject protocols at the University of California. Patients were recruited from developmental child neurology clinics throughout the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia presenting with features of neurodevelopmental delay or regression, ataxia, intellectual disability, autism, epilepsy or structural brain malformations between 2004 and 2012. Recruitment was focused in the major population centers of the Middle East including Morocco, Libya, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, UAE, Oman, Jordan, Pakistan, Turkey and Iran, with consanguinity rates (i.e. rate of marriage between first or second cousins) of approximately 50% compared with <1% is US and Western Europe. Among the recruited cohort, consanguinity was present in 63% of parents, suggesting some bias in sampling towards those with affected children due to recessive disease. Sampling was performed on both parents and all available genetically informative siblings to include affected and unaffected members, as well as extended family members if appropriate, upon informed consent approval and consistent with IRB guidelines. General and neurological examination, clinical records, radiographs, photographs, videos documenting movement, and past history were reviewed and patients were examined by one or more of the authors. Analysis of all patients presenting with a presumptive diagnosis of Cerebellar Atrophy were included in the analysis, based upon the finding of reduced cerebellar volume, and excessively prominent interfolial spaces on axial or sagittal sections. Patients with MRI showing pronounced pontine atrophy, severe peripheral neuropathy, white matter disease, telangiectasias, retinal blindness, or major cortical malformations such as cobblestone lissencephaly, were excluded. Patients with evidence of mitochondrial disease, abnormal transferrin isoelectric focusing, lysosomal storage such as mucolipidosis or ceroid were excluded. All patients were excluded for the common Friedreich ataxia expansion, and tested normal for alpha-fetoprotein and albumin. Blood and/or saliva was collected on all consenting potentially informative family members, DNA extracted with the Qiagen AutoPure instrument, and subject to quality control measures to measure concentration/purity and to confirm inheritance, and subject to subsequent genetic investigation.

Whole exome sequencing

WES was performed on two affected members per family when available, or both parents and affected member from singleton cases. Genomic DNA was subject to Agilent Human All Exon 50Mb kit library preparation, then paired-end sequencing (2x150bp) on Illumina HiSeq 2000 instrument. For each patient sample, >96% of the exome was covered at >12x. GATK1 was used for variant identification. We tested for segregating rare structural variants using XHMM2. We then prioritized homozygous variants using custom Python scripts (available upon request), to remove alleles with >0.1% frequency in the sequenced population, not occurring in homozygous intervals at least 2 cM in size or linkage intervals with more than -2 LOD score, or without high scores for likely damage to protein function. All variants were prioritized by allele frequency in publically available databases, conservation, and predicted effect on protein function, and were tested for segregation with disease.

Sanger sequencing

Primers were designed using the Primer3 program and tested for specificity using NIH BLAST software. PCR products were treated with Exonuclease I (Fermentas) and Shrimp Alkaline Phosphatase (USB Corporation) and sequenced using BigDye terminator cycle sequencing Kit v.3.1 on an ABI 3100 DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Sequence data was analyzed by Sequencher 4.9 (Gene Codes) to test segregation of the mutation with the disorder under a recessive mode of inheritance, taking advantage of all informative meioses in each family.

Cloning of human SNX14

The human SNX14 from adult brain cDNA was amplified and cloned into pdsRED2-C1 vector, and subcloned into doxycycline inducible lentiviral pINDUCER20 vector3. For N terminal Flag, SNX14 was amplified from adult brain cDNA using a 5’ primer containing Flag sequence and cloned into pINDUCER20 vector. SNX14 PX domain was amplified and cloned into pGEX-6P-1 vector for purified protein expression.

Human brain histology, oligosaccharide and glycosaminoglycan measurement

Sections were deparaffinized, and stained with 0.1% Luxol fast blue, 0.1% Cresyl violet or hematoxylin-eosin. Immunohistochemistry was performed with primary dilution of 1:200 antibody (Calbindin ABCAM ab11426, Neurofilament Pierce MIC-N18) and visualized with secondary HRP antibody (Jackson Labs). Control tissue corresponds to biobank identification number BB-0033-00082. Oligosaccharide and glycosaminoglycan measurements were performed as described4.

Fibroblast, IPSC and Neural Progenitor Cell culture

Fibroblasts were generated from explants of dermal biopsies collected from affected and unaffected volunteers, previously genotyped, and cultured in MEM (Gibco)/20% FBS (Gemini). IPSCs were generated as previously described from5. Briefly, three micrograms of expression plasmid mixtures (OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, L-MYC, LIN28 and p53 shRNA) were electroporated into 6X105 of cell, trypsinized 7d afterwards, and 1.5X105 cells were re-plated onto 100-mm dishes with 1.5X105 irradiated CF-1 mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) feeder layer. The culture medium was replaced the next day with standard hESC/IPSC medium, DMEM:F12 supplemented with 20% KOSR and 20 ng/ml bFGF (Invitrogen) 1X nonessential amino acids, 110 µM 2-Mercaptoethanol. Colonies were selected for further cultivation and evaluation. After 3 passages IPSCs cells were transferred to MEFs free plates and growth in mTeSr medium (Stem Cells Technologies). Neural progenitors cells (NPCs) were obtained as previously described6. Briefly, embryoid bodies (EBs) were formed by mechanical dissociation of cell clusters and plated in suspension in differentiation medium (DMEM F12, 1X N2, 1µM Dorsomorphin (Tocris), 2 µM A8301 (Tocris)) and kept shaking at 95 rpm for 7 days. Resultant EBs were plated onto Matrigel (BD Biosciences) coated dishes in NBF medium (DMEM F12, 0.5X N2, 0.5X B27, 20ng/ul bFGF). Rosettes were collected after 5–7 days, dissociated with Accutase (Millipore), and resultant NPCs plated onto poly-ornithine/laminin (Sigma) dishes with NPC medium. Medium was replaced every 2 days. Cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma. All experiments were performed with NPCs at passage 5–8.

For the genetic replacement experiments, patient NPCs were transduced with lentivirus containing Flag or dsRED tagged SNX14 (NM_153816) in pINDUCER20 vector3 in the presence of 8 µg/mL polybrene. Following one-week selection with 200 µg/ml G418, NPCs were treated with 50 ng/ml doxycyline for the transgene expression. Bright field images were taken in Olympus IX51 inverted microscope or in EVO microscope and processed with Photoshop CS5 (Adobe Systems). For autophagic induction cells were cultured in EBSS (Earl’s balanced salt solution) for 1.5–2 hr and treated with Leupeptin 200 µM and NH4Cl 20 mM for experiments performed to quantify LC3 II flux and autophagosome formation.

Cell fractionation assay

Cell fractionation was carried out as described previously7. Proteins in each fraction were precipitated with methanol-chloroform and resuspended in 60 µl of protein loading buffer from which 20 µl was processed for immunoblot analysis.

Lipid binding assay

The lipid blots were performed essentially as described previously8 with minor modifications. Briefly, 180, 60 and 20 pmol lipids were spotted on PVDF membranes and probed with 0.75ug of bacterially expressed GST-tagged PX domains. Proteins were detected by blotting with an anti-GST antibody.

Cellular Immunofluorescence and biochemical assays

Cells were fixed in 4% PFA for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton in PBS or methanol, blocked for 1 hr in PBS containing 0.05% and 2% donkey serum, then incubated with primary antibody (LC3, 1:200, Cell Signaling (2775), Lamp1, 1:200, DSHB (H4A3), Lamp2, 1:200, Abcam (Ab25631), EEA1, 1:200, BD (610456), GM130 1:200, Cell Signaling (2296)), overnight at 4°C, washed, and incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch) for 2 hr. Imaging was on an Olympus IX51, Leica SP5, or Nikon A2, processed with Photoshop CS5 (Adobe Systems). Cathepsin D activity was assessed with 2µg/ml Bodipy FL Pepstatin A for 45 min at 37°C, then fixed in 4% PFA before imaging.

For immunoblot assays fibroblasts or NPCs were lysed with ice-cold RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails (Roche). Proteins were separated in 10% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to PVDF membrane, blocked with 5% milk in 1x TBS-T, and blotted with primary antibody (mouse anti-SNX14, 1:1000, Sigma (SAB1304492), rabbit anti-LC3, 1:5000, Novus Biological (NB600-1384), mouse anti-Tubulin, 1:1000, Sigma (T6074), mouse anti-GAPDH, 1:1000, Millipore (MAB347), anti-Ribophorin, 1:1000, Abcam (ab38451), p62, 1:1000 Progen Biotechnik (GP62-C), Cathepsin D, 1:1000, Santa Cruz (C20), EEA1, 1:500, BD (610456), Lamp1, 1:500, DSHB (H4A3), GM130 1:500, Cell Signaling (2296)) overnight at 4°C. Detection used a peroxidase-coupled anti-IgG antibody (Pierce) and an enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Scientific Pierce ECL). Experiments were replicated three times.

For RT-PCR, total RNA was extracted with RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), a total of 2 µg RNA was transcribed to cDNA using the SuperScript (Invitrogen) with oligodT. Specific primers were used for PCR.

Flow cytometry for Lysotracker intensity analysis

Neural progenitor cells were harvested, brought to 10x5 cells/ml and incubated with 100 nM Lysotracker Green DND-26 for 15 min at 37°C. Live cells were analyzed for Lysotracker fluorescence intensity levels by first gating on all cell material except small debris in the origin of a FSC versus SSC dot-plot. Lysotracker signal from samples were then compared by dot plot and histogram analysis.

Zebrafish In situ hybridization, knockdown and immunofluorescence

Adult male and female zebrafish (<18 months old) from wild-type (AB Tübingen) and transgenic strains were maintained under standard laboratory conditions. At least three adult pairs were used to generate embryos at 0–5 d.p.f. for each experiment, with embryos from the same pair used both for control and snx14 morpholino injections. No randomization was performed. Translational blocking antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MO) for snx14 or scrambled sequence MO were injected into one-cell stage embryos. Full-length human wild-type SNX14 mRNA (50 ng) was co-injected with the MO as described9. Optic tectum and right eye width was measured digitally to assess neural affectation. Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed on 24 and 48 hours post fertilization (hpf) zebrafish embryos using snx14 RNA probes generated by PCR. Experiments followed NIH guidelines and were performed in compliance with IACUC at University of California San Diego.

Transmission electron microscopy

Samples were immersed in modified Karnovsky’s fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.15 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4) for at least 4 hours, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.15 M cacodylate buffer for 1 hour and stained en bloc in 2% uranyl acetate for 1 hour. Samples were dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in Durcupan epoxy resin (Sigma-Aldrich), sectioned at 50 to 60 nm on a Leica UCT ultramicrotome, and picked up on Formvar and carbon-coated copper grids. Sections were stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 5 min and Sato's lead stain for 1 min. Grids were viewed using a Tecnai G2 Spirit BioTWIN transmission electron microscope equipped with an Eagle 4k HS digital camera (FEI).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were replicated at least twice. Data are expressed as means with variance as s.e.m. or s.d. For all quantitative measurements a normal distribution was assumed and we used the two-tailed Student t-test to perform between group comparisons. p-value <0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, which were determined empirically from previous experimental experience with similar assays and/or from sizes generally employed in the field. Data collection and analysis were not performed with blinding. Raw values used to generate plots is available as source data.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health P01HD070494, R01NS048453 and HHMI (to J.G.G.), National Institues of Health K99NS089859-01 (to N.A.), Broad Institute grant U54HG003067, the Yale Center for Mendelian Disorders U54HG006504 (to M.G.), Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, University Paris Descartes, the St. Giles Foundation, and the Candidoser Association and HHMI (to J-LC), The Scientific and Technology Research Council of Turkey (Grant TÜ;BİTAK-SBAG, 111S217, Grant TÜBİTAK-BİLGEM-UEKAE, K030-T439) and Turkey Republic Ministry of Development (Grant TRMOD, 108S420) (to A.D.), Yuval Itan and Bertrand Boisson for sequencing, Timo Meerloo for electron microscopy support, Sanford Burnham Institute for IPSC reprogramming, Ana Maria Cuervo and Marilyn Farquhar for comments and suggestions. Analysis was performed by the UCSD Glycotechnology Core and the UCSD Microscopy Imaging Core.

Footnotes

ACCESSION CODES. The whole exome sequencing data from individuals in this study have been deposited to dbGaP under accession number phs000288.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Patient recruitment and phenotyping: M.S.Z., L.A-G., R.O.R., E.D., A.B.G., R.K.O., M.S.S., M.A., L.S., I.G., S.A-H., M.A., S.I., A.E.B., A.A.S., F.M., H.K., A.M., L.B., S.T., I. D., A.D., K.K.V., J.G.G. Genetic sequencing and interpretation: N.A., V.C., X.W., J.L.S., J.S., E.M.S., B.C., J-L.C., M.G., S.B.G., P.d.L., A.D. Cell biology: N.A., V.C., J.D.E., M.D.B., S.J.F., G.N., P.G., U.M., Zebrafish: B.R., N.A., X.W. Cell culture: A.E.S., N.A., Histology: A.B.G., I.D.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coutinho P, et al. Hereditary ataxia and spastic paraplegia in Portugal: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:746–755. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim J, et al. Opposing effects of polyglutamine expansion on native protein complexes contribute to SCA1. Nature. 2008;452:713–718. doi: 10.1038/nature06731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor JP, Hardy J, Fischbeck KH. Toxic proteins in neurodegenerative disease. Science. 2002;296:1991–1995. doi: 10.1126/science.1067122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roda RH, Rinaldi C, Singh R, Schindler AB, Blackstone C. Ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2 fibroblasts exhibit increased susceptibility to oxidative DNA damage. J Clin Neurosci. 2014;21:1627–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2013.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilguvar K, et al. Recessive loss of function of the neuronal ubiquitin hydrolase UCHL1 leads to early-onset progressive neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3489–3494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222732110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deik A, Saunders-Pullman R. Atypical presentation of late-onset Tay-Sachs disease. Muscle Nerve. 2014;49:768–771. doi: 10.1002/mus.24146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ko DC, et al. Cell-autonomous death of cerebellar purkinje neurons with autophagy in Niemann-Pick type C disease. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:81–95. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paton L, et al. A Novel Mouse Model of a Patient Mucolipidosis II Mutation Recapitulates Disease Pathology. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:26709–26721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.586156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong E, Cuervo AM. Autophagy gone awry in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:805–811. doi: 10.1038/nn.2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batlevi Y, La Spada AR. Mitochondrial autophagy in neural function, neurodegenerative disease, neuron cell death, and aging. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;43:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cullup T, et al. Recessive mutations in EPG5 cause Vici syndrome, a multisystem disorder with defective autophagy. Nat Genet. 2013;45:83–87. doi: 10.1038/ng.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hara T, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komatsu M, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dall'Armi C, Devereaux KA, Di Paolo G. The role of lipids in the control of autophagy. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R33–R45. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dixon-Salazar TJ, et al. Exome sequencing can improve diagnosis and alter patient management. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:138ra178. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bargal R, Goebel HH, Latta E, Bach G. Mucolipidosis IV: novel mutation and diverse ultrastructural spectrum in the skin. Neuropediatrics. 2002;33:199–202. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchetto MC, et al. A model for neural development and treatment of Rett syndrome using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okita K, et al. A more efficient method to generate integration-free human iPS cells. Nat Methods. 2011;8:409–412. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen CS, Chen WN, Zhou M, Arttamangkul S, Haugland RP. Probing the cathepsin D using a BODIPY FL-pepstatin A: applications in fluorescence polarization and microscopy. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2000;42:137–151. doi: 10.1016/s0165-022x(00)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pampliega O, et al. Functional interaction between autophagy and ciliogenesis. Nature. 2013;502:194–200. doi: 10.1038/nature12639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin JW, et al. Differential requirement for ptf1a in endocrine and exocrine lineages of developing zebrafish pancreas. Dev Biol. 2004;270:474–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas AC, et al. Mutations in SNX14 Cause a Distinctive Autosomal-Recessive Cerebellar Ataxia and Intellectual Disability Syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:611–621. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sousa SB, et al. Intellectual disability, coarse face, relative macrocephaly, and cerebellar hypotrophy in two sisters. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:10–14. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aker M, et al. An SNX10 mutation causes malignant osteopetrosis of infancy. J Med Genet. 2012;49:221–226. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2011-100520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang HS, et al. Snx14 regulates neuronal excitability, promotes synaptic transmission, and is imprinted in the brain of mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, et al. Loss of sorting nexin 27 contributes to excitatory synaptic dysfunction by modulating glutamate receptor recycling in Down's syndrome. Nat Med. 2013;19:473–480. doi: 10.1038/nm.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallon M, et al. A unique PDZ domain and arrestin-like fold interaction reveals mechanistic details of endocytic recycling by SNX27-retromer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E3604–E3613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410552111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heiseke A, et al. The novel sorting nexin SNX33 interferes with cellular PrP formation by modulation of PrP shedding. Traffic. 2008;9:1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y, et al. Sorting nexin 12 interacts with BACE1 and regulates BACE1-mediated APP processing. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:30. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J, et al. Adaptor protein sorting nexin 17 regulates amyloid precursor protein trafficking and processing in the early endosomes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11501–11508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800642200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raben N, et al. Suppression of autophagy permits successful enzyme replacement therapy in a lysosomal storage disorder--murine Pompe disease. Autophagy. 2010;6:1078–1089. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.8.13378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

METHODS-ONLY REFERENCES

- 1.DePristo MA, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fromer M, et al. Discovery and statistical genotyping of copy-number variation from whole-exome sequencing depth. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meerbrey KL, et al. The pINDUCER lentiviral toolkit for inducible RNA interference in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3665–3670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019736108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clements PR. Determination of sialylated and neutral oligosaccharides in urine by mass spectrometry. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg1710s72. Chapter 17, Unit17 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okita K, et al. A more efficient method to generate integration-free human iPS cells. Nat Methods. 2011;8:409–412. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchetto MC, et al. A model for neural development and treatment of Rett syndrome using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordts PL, et al. Impaired LDL receptor-related protein 1 translocation correlates with improved dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dippold HC, et al. GOLPH3 bridges phosphatidylinositol-4- phosphate and actomyosin to stretch and shape the Golgi to promote budding. Cell. 2009;139:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hegarty JM, Yang H, Chi NC. UBIAD1-mediated vitamin K2 synthesis is required for vascular endothelial cell survival and development. Development. 2013;140:1713–1719. doi: 10.1242/dev.093112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.