Abstract

Receptor levels are a key mechanism by which cells regulate their response to stimuli. The levels of estrogen receptor-α (ERα) impact breast cancer cell proliferation and are used to predict prognosis and sensitivity to endocrine therapy. Despite the clinical application of this information, it remains unclear how different cellular processes interact as a system to control ERα levels. To address this question, experimental results from the ERα-positive human breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) treated with 17-β-estradiol or vehicle control were used to develop a mass-action kinetic model of ERα regulation. Model analysis determined that RNA dynamics could be captured through phosphorylated ERα (pERα)-dependent feedback on transcription. Experimental analysis confirmed that pERα-S118 binds to the estrogen receptor-1 (ESR1) promoter, suggesting that pERα can feedback on ESR1 transcription. Protein dynamics required a separate mechanism in which the degradation rate for pERα was 8.3-fold higher than nonphosphorylated ERα. Using a model with both mechanisms, the root mean square error was 0.078. Sensitivity analysis of this combined model determined that while multiple mechanisms regulate ERα levels, pERα-dependent feedback elicited the strongest effect. Combined, our computational and experimental results identify phosphorylation of ERα as a critical decision point that coordinates the cellular circuitry to regulate ERα levels.—Tian, D., Solodin, N. M., Rajbhandari, P., Bjorklund, K., Alarid, E. T., Kreeger, P. K. A kinetic model identifies phosphorylated estrogen receptor-α (ERα) as a critical regulator of ERα dynamics in breast cancer.

Keywords: systems biology, mathematical modeling, nuclear receptor, feedback

Estrogen receptor-α (ERα) is a key regulator in normal physiology, as well as disease development and progression (1–3). It is the primary biologic mediator of 17-β-estradiol (E2), the most potent human estrogen, and plays a critical role in breast development with impacts on cell cycle, proliferation, and apoptosis (4, 5). Approximately 70% of all breast cancers are ERα positive (6, 7); as a result, ERα is the most important and predictive biomarker used to classify breast cancer patients and recommend therapy options (8, 9). In addition to surgery, radiation, and cytotoxic therapies, endocrine therapy is commonly used to treat ERα-positive breast cancer. Endocrine therapy consists of either directly targeting ERα through selective estrogen receptor modulators (e.g., tamoxifen) or inhibiting E2 production through aromatase inhibitors or ovarian suppression (10). Although endocrine therapy has improved the prognosis for ERα-positive breast cancers, ∼30–50% of patients will fail to respond to initial therapy or develop resistance over time (11–15). ERα expression is a reliable predictor of response to tamoxifen therapy (16, 17), with intrinsic tamoxifen resistance resulting from tumors with <1% of cells expressing ERα (18). However, ERα expression in human tumors varies over 2 orders of magnitude (19), and evidence suggests that tumors with low and extremely high levels of ERα can exhibit a more aggressive phenotype with increased proliferation and decreased recurrence-free survival (20–22). Therefore, an improved understanding of the control system regulating ERα levels may identify key determinants of ERα expression and impact treatment of breast cancer.

Cellular levels of ERα are autologously controlled through both posttranslational and transcriptional mechanisms. ERα levels are dynamically regulated and fluctuate inversely with circulating estrogen levels (23–26). As a member of the nuclear receptor family of transcription factors, ligand binding activates a genomic pathway where ERα undergoes a series of events including phosphorylation (27), dimerization (28), binding to estrogen response elements in target genes (29), and ultimately the recruitment of coregulator complexes and the basal transcriptional machinery to activate or repress gene expression (30). More than 400 genes, including the ERα gene, estrogen receptor-1 (ESR1) (31), are regulated by estrogen treatment in breast cancer cells, highlighting the broad cellular impact of ERα activation. Ligand activation induces ERα protein recruitment to the ESR1 proximal promoter and recruits chromatin remodeling enzymes associated with gene repression. In parallel, ERα protein is ubiquitinated and targeted for destruction by the 26S proteasome. Although the molecular details of these pathways have been investigated individually, it remains unclear how these pathways are coordinated (32, 33).

Therefore, in this study, we used a systems biology approach to investigate the regulation of ESR1 and ERα levels in response to treatment with E2. Specifically, we used experimental data collected in the ERα-positive human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 (34, 35) to fit a mass-action kinetic model and examine potential mechanisms for the observed system dynamics. As ERα is phosphorylated in response to E2 binding and this phosphorylation is an early event in receptor activation, we focused on the potential role of this posttranslational modification in regulating both ESR1 and ERα levels following E2 treatment. Model analysis suggested and experimental results confirmed key roles for phosphorylated ERα (pERα) in regulating system dynamics, demonstrating the power of using computational modeling to study the complexities of networks such as the ERα system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

MCF-7 cells were maintained at 37°C and 10% CO2 in DMEM (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Prior to estrogen treatment, cells were estrogen-starved for 3 days in phenol red-free medium with 10% charcoal/dextran-stripped fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 4 mM l-glutamine. For steroid treatment, cells were incubated with 10 nM E2 (Steraloids, Newport, RI, USA). Ethanol vehicle at 0.1% was used as a control, and cells were harvested at times ranging from 0 to 8 h as indicated in the figures.

Experimental analysis of E2-treated cells

Western analysis was conducted on whole cell lysates as previously described (36). Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and lysed directly in sample buffer consisting of 6.5 nM Tris (pH 6.8), 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 10 min. Protein was quantified using RC/DC protein assay (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Protein lysate (90 μg) was diluted in sample buffer and boiled for 5 min, loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel, separated by gel electrophoresis, transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), and detected with anti-ERα (HC-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) or anti-pS118ERα (#2511; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). Bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare, Logan, UT, USA) and measured by densitometry using BioRad Quantity One Software. To quantify ERα and pERα, a standard was generated for each experiment using serial dilutions of control samples. Only exposures where the standard curve r value was >0.9 were used in the analysis of protein values. Linear regression analysis was performed to determine the amounts of ERα and pERα protein relative to the control sample.

Nascent ESR1 RNA (nRNA) (34), ESR1 (34), and total ERα (tERα) time courses (35) were obtained from published experimental results performed with identical clones of ERα-positive breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) and under the experimental conditions described above.

Model structure

Two mass-action kinetic models were developed to examine regulation of ERα RNA and protein levels after E2 treatment, incorporating the processes of transcription, splicing, translation, phosphorylation, and degradation. First, an empirical model was developed with essential features of these processes represented as first-order processes with effective rates and without any feedback

|

|

|

|

where Ci is the concentration of component i and the subscripts nRNA, mRNA, ER, and pER refer to nRNA, mRNA, nonphosphorylated ERα, and pERα, respectively. For these reactions, SnRNA is the transcription rate of nascent ESR1, k1 is the rate coefficient of processing into mRNA, k2 is the translation rate coefficient of ERα, k3 is the phosphorylation rate coefficient, k-3 is the dephosphorylation rate coefficient, kd,1 is the rate coefficient of mRNA degradation, kd,2 is the rate coefficient of degradation of nonphosphorylated ERα protein, and kd,3 is the rate coefficient of pERα degradation. To reduce complexity related to units, concentrations of nRNA, mRNA, and nonphosphorylated ERα were defined as fractions relative to their steady-state concentrations prior to E2 treatment. The concentration of pERα was a fraction relative to the level of ERα present before E2 treatment, and was calculated based on previous reports that demonstrated that 50% of the ERα still present at 30 min after E2 treatment was phosphorylated (37). tERα was calculated as the sum of nonphosphorylated ERα and pERα to fit the model to the available experimental data, which does not distinguish between the 2 forms.

In the second model, a feedback coefficient F was incorporated into Eq. 1a to examine feedback by pERα as a possible mechanism, resulting in Eq. 1a′

|

Feedback was assumed to be proportional to pERα concentration such that the feedback mechanism was inactivated before treatment with E2, when pERα levels were 0. Although pERα has not been shown previously to impact ESR1 transcription, it does participate in transcriptional regulation of many different genes (38). The feedback coefficient term F was defined by

|

As such, F will equal 1 when the concentration of pERα is 0 (prior to E2 treatment) and will decrease with increasing concentration of pERα. The strength of feedback was controlled by a feedback tuning parameter, a.

Several assumptions were used in the development of these models. First, in the absence of E2, the concentration of pERα was assumed to be 0. Second, processing of nRNA into mRNA was assumed to be irreversible. Third, the degradation rate of nRNA was assumed to be negligible because the majority of nRNAs are rapidly spliced into mRNA and the rapid 5′ capping of nRNA functions to protect, stabilize, and prevent the degradation of nRNA (39–42). Fourth, based on the classic kinetic approach of transcription and translation, mRNA was assumed not to be destroyed during translation (43–46). Fifth, it was assumed that ERα and pERα do not necessarily degrade at the same rate. Last, the phosphorylation rate and dephosphorylation rate were assumed to have a ratio of 100:1, based on epidermal growth factor receptor phosphorylation and dephosphorylation rate measurements (47–49). Although this ratio is approximate, the best-fit model results were not strongly sensitive to the value of this ratio (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Model parameterization

Eqs. 1a–d were numerically integrated using the ode45 solver in MATLAB v7.14, which uses a variable step Runge-Kutta method (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Values for parameters of the empirical model are listed in Table 1. In the empirical model, all 8 rate parameters in Eqs. 1a–d were treated as adjustable fitting parameters, and the model was fit to the experimental data (Fig. 1A) using the lsqcurvefit routine that minimizes the sum of the squares of the residual error between the model calculations and the experimental data.

TABLE 1.

Rate coefficients of the empirically fit model, the steady-state solution in the absence of E2, and the best-fit solution for the feedback model with increased pERα degradation

| Rate | Description | Empirical fit (h−1) | Steady-state values (h−1) | Feedback model (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SnRNA | Transcription rate of RNA | 0.179 | 0.422a | 0.422a |

| k1 | Rate coefficient of mRNA splicing from nascent RNA | 0.500 | 0.422a | 0.422a |

| k2 | Translation rate coefficient of ERα protein | 0.119 | 0.198b | 0.198b |

| k3 | Phosphorylation rate coefficient of ERα | 1.940 | 0 | 2.002 |

| k-3 | Dephosphorylation rate coefficient of ERα | 0 | — | 0.020 |

| kd,1 | Degradation rate coefficient of mRNA | 0.473 | 0.422a | 0.422a |

| kd,2 | Degradation rate coefficient of non-phosphorylated ERα | 0.100 | 0.198b | 0.198b |

| kd,3 | Degradation rate coefficient of phosphorylated ERα | 1.661 | — | 1.652 |

| a | Feedback tuning parameter | — | — | 20.232 (unitless) |

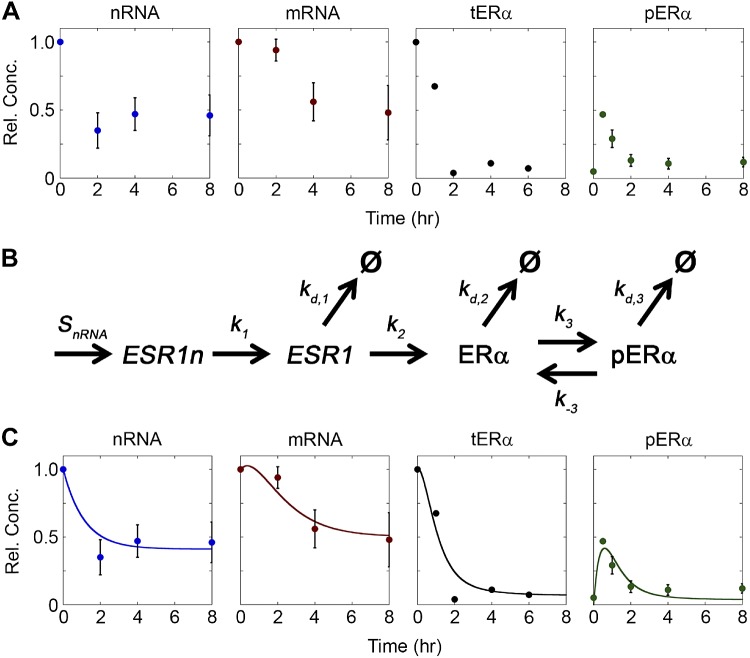

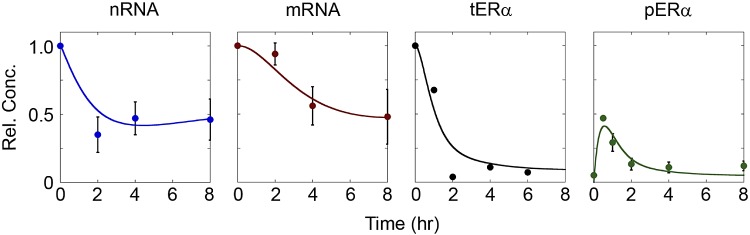

Figure 1.

An empirically fit model of ERα dynamics captured experimental data trends. A) ESR1 and ERα levels were dynamic after E2 treatment. qRT-PCR was used to analyze the expression of nascent ESR1 (nRNA) and fully processed messenger ESR1 (mRNA) in MCF-7 cells following treatment with 10 nM E2 (34). tERα was measured by pulse-chase analysis (35), and pERα was measured by Western blot as described in the Materials and Methods. Data for nRNA, mRNA, and tERα were normalized to levels of EtOH-treated controls. Because of the experimental method used, tERα measurements included both nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated forms of ERα. Data for pERα were normalized to the initial concentration of tERα. n = 3 for nRNA, mRNA, and pERα; n = 1 for tERα. B) Diagram of reactions included in the empirically fit model of ESR1 and ERα following E2 treatment. C) Comparison of the empirically fit model to experimental data. In all figures, model results are represented by solid lines and experimental data are represented by circles.

To fit the feedback model and examine ERα behavior before and after treatment with E2, it was desirable that parameters were consistent between these 2 states. Therefore, several kinetic parameters were inferred from published data and an analysis of steady-state ERα behavior prior to treatment with E2. kd,2 was determined using the basal half-life of endogenous ERα, which was determined to be ∼3.5 h by pulse-chase analysis (35, 50). Determining kd,2 allowed for other basal rates to be determined from the pre-estrogen steady-state solution of the model, where phosphorylation has not occurred and Eq. 1c reduces to

Because concentrations are fractions relative to before E2 treatment and are therefore both equal to 1 in the untreated steady state, Eq. 3 implies k2 = kd,2. The parameters SnRNA, k1, and kd,1 were determined from further analysis of the untreated steady state, where steady-state solutions of Eqs. 1a′ and 1b lead to the following relationship between SnRNA, k1, and kd,1:

Thus, the values of SnRNA, k1, and kd,1 are linked. To determine kd,1, a least squares fit of the numerical solution of Eqs. 1a and 1b was performed using ESR1 mRNA levels after treatment with the RNA synthesis inhibitor actinomycin D (34). This resulted in a value of 0.422 h−1 for kd,1, and hence, for SnRNA and k1. Following this analysis, the feedback model had 3 adjustable fitting parameters: k3, kd,3, and a. As with the empirical model, adjustable fitting parameters were determined using the lsqcurvefit routine for the numerical solution of Eqs. 1a′–d and experimental measurements of the concentrations of nRNA, mRNA, tERα, and pERα (Fig. 1A) with the ode45 solver in MATLAB v7.14. Values of all parameters for the feedback model are listed in Table 1.

To determine the sensitivity of tERα levels to parameters specific to processes after E2 treatment, simulations using the feedback model were performed with variable parameter values for k3, kd,3, and a. In each case, all parameters other than those being varied were fixed at their best-fit value, and the impact on steady-state tERα concentration was calculated. Model sensitivity for parameter i was calculated for individual parameters [log(tERαi/tERαi,0)] and then for a in combination with another model parameter.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was carried out as previously detailed (34). Briefly, MCF-7 cells were treated with 0.1% EtOH or 10 nM E2 for 30 min, and ChIP was performed using pS118ERα antibody or mouse IgG (sc-2025; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as an immunoprecipitation (IP) control. Quantitative RT-PCR on the ESR1 promoter was carried out as previously described using 1 μl of input, 4 μl of IP sample, and 200 nM of forward (TCCTCCAGCACCTTTGTAATG) and reverse (AAGTGCAGC-TCCCAGGAC) primers (34). Data were analyzed based on the percent input: [100 × 2(Ctinput – CtIP)]/z, where z = IP [(μl loaded qRT-PCR/μl eluted during DNA purification) × (μl in IP/total lysate)]/input [(μl loaded qPCR/µl eluted during DNA purification) × (μl in input/total lysate)].

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± se. Statistical significance was evaluated using Student paired t test analysis, with P < 0.05. Statistical calculations were performed using JMP 4.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

An empirically fit model suggests ESR1 transcription is altered by E2 treatment

A quantitative model analyzing ERα dynamics would provide a means to understand conditions that lead to elevated or suppressed levels of ERα. As a first step toward developing such a framework, we constructed a mass-action kinetic model describing ERα behavior after E2 treatment and fit this model to experimental data collected in MCF-7 cells (34, 35). This model form relies on the law of mass action, which states that for an elementary chemical reaction, the rate is proportional to the product of the concentrations of the reactants (51). To apply mass-action kinetics to a biologic network, the different mechanistic steps (e.g., transcription, phosphorylation, degradation) are thought of as chemical reactions with associated rates and then transformed into a system of differential equations (52). The experimental data set (Fig. 1A) demonstrated that after treatment with E2, there was a rapid decrease in ESR1 and ERα before a new lower steady-state was reached. Estrogen binding to ERα resulted in the phosphorylation of ERα, which was observed in the MCF-7 cells as a transient induction of pERα-S118 (Fig. 1A). To examine this system, our model (Eqs. 1a–d; Fig. 1B) incorporated transcription, translation, and receptor activation and followed 4 distinct ERα species: nascent ESR1 (nRNA), ESR1 mRNA (mRNA), nonphosphorylated ERα, and pERα.

This model was first empirically fit to the experimental data in Fig. 1A, where tERα is the sum of nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated ERα. All rate coefficients were allowed to be independent adjustable parameters (Fig. 1C). The empirically fit model showed a strong agreement with the experimental data, capturing the magnitude and timing of the decreases in RNA and tERα, the transient increase in pERα, and the lower steady-state achieved by the different species after several hours of E2 treatment. However, it is important to note that these rate coefficients do not allow for the system to maintain the initial steady state in the absence of E2 treatment (Supplemental Fig. S2). Therefore, the rate coefficients for the empirically fit model were compared with the steady-state values that maintain this initial state to determine which mechanisms were potentially altered in response to E2 treatment (Table 1). Obviously, the phosphorylation rate was different between the 2 cases, as this was set to 0 in the untreated condition and must not be 0 in the treated condition to allow for the phosphorylation of ERα. Although several additional parameters showed small variation, the parameter that changed the most substantially was the transcription rate (SnRNA), which decreased >2-fold for nRNA and mRNA to drop following E2 treatment. Although this empirically fit model showed good agreement with the experimental data and suggested that E2 treatment reduces ESR1 transcription, it did not provide any insight into the underlying mechanisms regulating ERα levels. Therefore, we next examined whether modifications to the model structure that incorporated potential feedback mechanisms impacting transcription could capture this behavior and maintain consistent parameters between steady-state and E2-treated conditions.

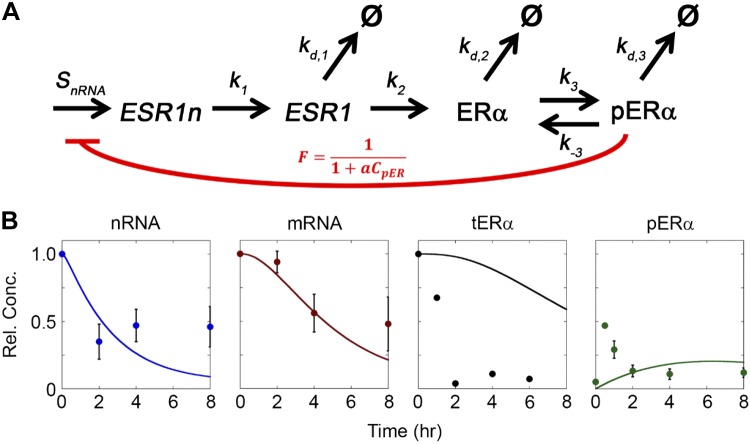

pERα-dependent negative feedback on transcription qualitatively captures RNA dynamics

We hypothesized that transcription could be suppressed by feedback from pERα, because receptor phosphorylation is the earliest signaling event following E2 treatment (Fig. 1A). Mathematically, feedback was incorporated into the model in the form of a feedback coefficient F applied to the transcription rate, with F defined to be inversely proportional to pERα concentration multiplied by a tuning parameter a (Fig. 2A; Eq. 2). The inclusion of this tuning parameter a allows for pERα-dependent feedback to be modulated by elements that are not specifically included in the model, such as the availability of coregulators. To determine whether this feedback mechanism alone could account for the behavior of the system after E2 treatment, the transcription rate (SnRNA), rate coefficient of mRNA processing from nRNA (k1), translation rate coefficient (k2), mRNA degradation rate coefficient (kd,1), and degradation rate coefficient of nonphosphorylated ERα (kd,2) were assumed to be fixed at their untreated steady-state values (Table 1). Further, as a first approximation and in an effort to minimize the total number of fitting parameters, the degradation rate coefficient of pERα (kd,3) was set equal to kd,2, leaving the phosphorylation rate coefficient (k3) and the feedback tuning parameter (a) to fit the feedback model to the experimental data.

Figure 2.

Inclusion of pERα negative feedback captured RNA trends qualitatively. A) Diagram of the reactions included in the feedback model of ERα regulation, where the red arc represents pERα-dependent negative feedback on ESR1 transcription. B) Comparison of the feedback model fit to experimental data with kd,3 equal to kd,2.

As seen in Fig. 2B, the incorporation of this feedback mechanism allowed the model to fit early RNA dynamics without changes to the steady-state parameters. As the underlying transcription rate did not change, this mechanism implied that pERα led to less transcription. Additionally, although the rate for processing mRNA from nRNA was unchanged in this new model, the feedback model captured both the drop in mRNA levels and the dynamics, which lag behind the decrease in nRNA. In contrast, the dynamics of the decrease in tERα was too slow and the peak in pERα activation was not captured. As a result, the level of feedback was too strong at later times, such that transcription did not keep up with degradation and there was excessive RNA depletion relative to the experimental data.

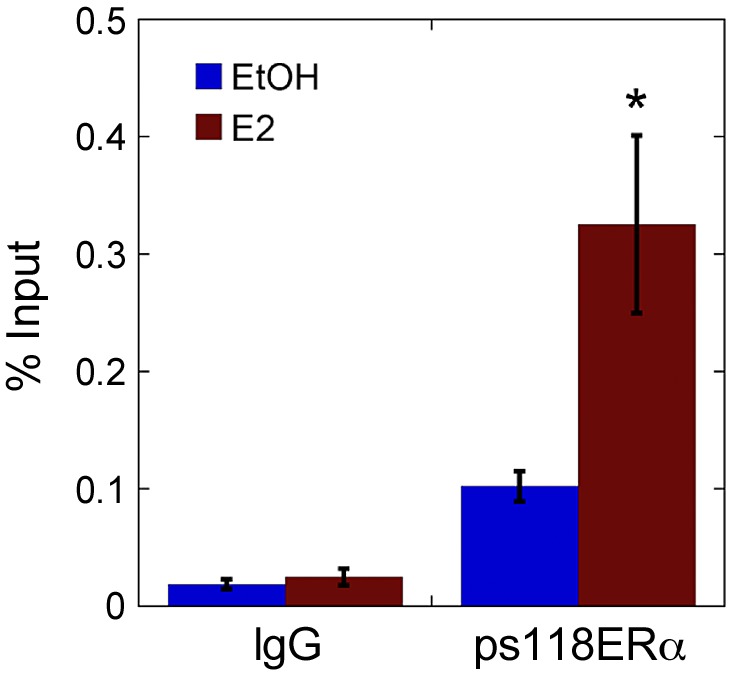

To determine whether the proposed feedback mechanism can occur directly (i.e., pERα binds to the ESR1 promoter) or indirectly (i.e., pERα interacts with other factors that inhibit transcription), we used ChIP to probe protein-DNA interactions at the ESR1 promoter. ChIP analysis showed that ERα phosphorylated at S118 bound to the ESR1 promoter (Fig. 3), which suggests that pERα can regulate expression of ERα and corroborated model analysis that pERα provides feedback to transcription.

Figure 3.

ChIP confirmed the possibility of pERα-dependent negative feedback. Experimental analysis by ChIP demonstrated that pERα-S118 bound directly to the ESR1 promoter, and this interaction significantly increased after 30 min of E2 treatment. *Significantly different (P < 0.05) from EtOH-treated vehicle control, n = 5.

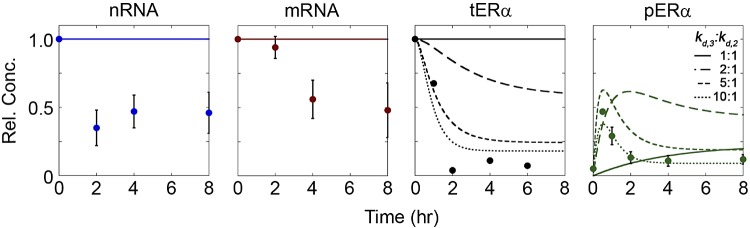

Elevated degradation of pERα is necessary to explain protein dynamics

Although some qualitative experimental trends were captured by the inclusion of pERα-dependent feedback, we next examined whether changes to parameters involved in processes that occur after E2 treatment could better capture the experimentally observed dynamics. As pERα degradation cannot occur prior to E2 treatment and therefore cannot be determined from the steady-state analysis of the untreated state, we specifically examined how a range of values of kd,3 impacted model behavior, using the original model structure without feedback (Fig. 1B). From these results (Fig. 4), it was evident that an increased rate of pERα degradation could contribute to the observed decrease in tERα. Because the experimental data for tERα incorporated both nonphosphorylated and phosphorylated forms of ERα, the increase in kd,3 provided a stronger mechanism to remove tERα from the system. As kd,3 increased from 1 to 5 times kd,2, this also resulted in increased flux through the pathway, leading to both a higher peak in pERα and a faster timeframe in which this peak was reached. However, as kd,3 increased further (to 10 times kd,2), the degradation rate reached the same order of magnitude as the phosphorylation rate, which resulted in a decrease in the peak level of pERα. Although this parameter change could be used to better capture protein dynamics, it could not capture the observed drop in RNA because of the irreversibility of transcription and processing.

Figure 4.

Increasing pERα degradation rate (kd,3) captured protein dynamics. Model simulated time courses of nRNA, mRNA, tERα, and pERα following E2 treatment for increasing values of kd,3 (1–10 times greater than kd,2).

Model with both mechanisms captures RNA and protein dynamics

As the feedback mechanism qualitatively captured RNA dynamics and increased degradation was able to explain protein dynamics, we next examined if inclusion of both mechanisms could describe the full system. The feedback model (Fig. 2A) was evaluated again, with kd,3 included as a free parameter with k3 and a. The best-fit model combining these 2 potential mechanisms (Fig. 5) showed excellent agreement with both qualitative and quantitative experimental trends. The empirically fit and constrained feedback models exhibited nearly identical values of root mean square error (0.082 and 0.078, respectively) and were significantly better than models with only the feedback mechanism (0.42) or increased degradation rate (0.44 for kd,3:kd,2 of 10:1). Additionally, the values for kd,3 were similar between the 2 models (Table 1). In contrast to the empirically fit model (Supplemental Fig. S2), if the feedback model was analyzed in the absence of E2, all species remain at their untreated steady-state values as the parameters central to those processes remain unchanged. Additionally, when the effect of removing E2 treatment on the system was simulated by setting k3 equal to 0 after 4 h of treatment, all system components returned to their untreated steady-state levels (Supplemental Fig. S3). The combined model can therefore represent the behavior of the ERα system both with and without E2 while using the same set of model parameters.

Figure 5.

Incorporating both negative feedback and increased kd,3 captured qualitative and quantitative data trends. Comparison of the feedback model to experimental data, with kd,3 included as a free parameter in model fitting.

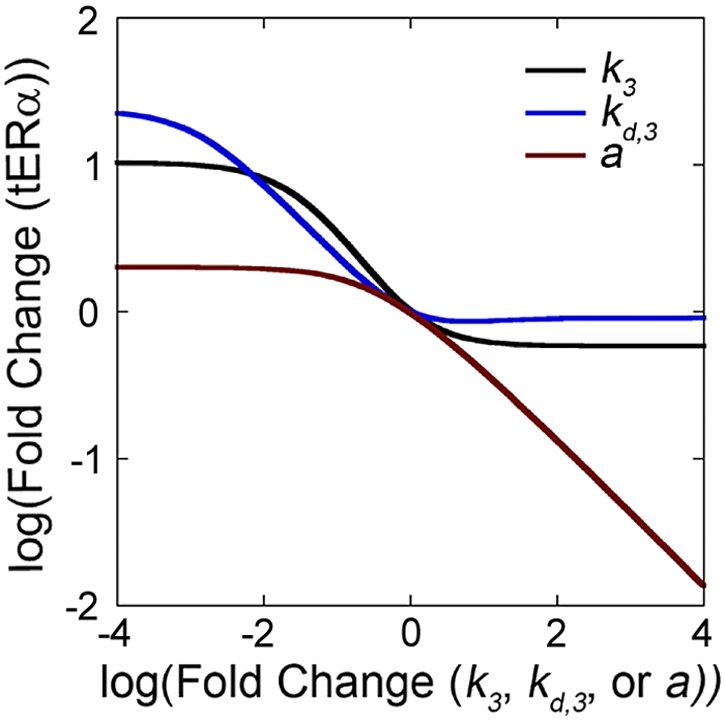

We next analyzed the combined model to determine which processes are optimal therapeutic targets to regulate ERα. In this analysis, we examined the effect that changes to model parameters had on steady-state tERα concentration after E2 exposure, as tERα levels correlate to predicted therapeutic response clinically (53). We first focused our analysis on k3, kd,3, and a, as these variables regulate the system’s response to E2. Increases in k3 and kd,3 resulted in a decrease in steady-state tERα, but reached a constant value where further changes in parameter value no longer affected tERα levels (Fig. 6). Conversely, decreasing k3 and kd,3 resulted in an increase in steady-state tERα that reached a constant value where further changes to the parameter also no longer affected tERα levels. Although k3 and kd,3 behaved similarly, a higher value of tERα was reached by decreasing kd,3, whereas increasing k3 was more effective at decreasing tERα. Similar to k3 and kd,3, decreasing the feedback tuning parameter a resulted in an increase in tERα that reached a constant value so that further decreases to a no longer affected tERα. However, in contrast with k3 and kd,3, increasing a resulted in continuously decreasing tERα; therefore, the feedback tuning parameter a appeared to be the most effective mechanism to lower tERα.

Figure 6.

Increases in a were predicted to have the greatest impact on decreasing ERα levels. Sensitivity analysis demonstrated that increasing k3, kd,3, and a resulted in a decrease in steady-state tERα, whereas decreasing these parameters resulted in an increase in steady-state tERα.

DISCUSSION

Investigations of ERα expression in breast cancer cells have revealed that E2 regulates ERα levels by multiple mechanisms; however, a single model detailing the coordinated control of ERα expression has not been developed. We hypothesized that a quantitative systems biology model analyzing ERα dynamics could provide novel insights and developed a mass-action kinetic model of ERα transcription, processing, translation, activation, and degradation in ERα-positive MCF-7 cells that was able to account for how ERα levels are regulated in response to E2. Although this model does not address the magnitude of ERα-mediated responses such as gene expression and cell proliferation, ERα levels in breast cancer tumors are a strong predictor of response to endocrine therapies (8, 9). Analysis of this model identified 2 potential regulatory roles of pERα in this system—negative feedback control of transcription and accelerated degradation of pERα—which were both needed to capture the experimentally observed trends in RNA and protein levels. ChIP analysis demonstrated that pERα-S118 bound directly to the ESR1 promoter, validating the model prediction that pERα directly inhibits transcription. Model analysis indicated that increasing the feedback tuning parameter (a) was the most effective at decreasing steady-state tERα concentration after E2 exposure, whereas decreasing the degradation rate of pERα (kd,3) was the most effective at increasing tERα. The importance of the feedback mechanism was further underscored by our multivariate sensitivity analysis that demonstrated that increases in a can suppress the effect of certain parameter variations (Supplemental Fig. S4). Thus, our relatively simple quantitative model of the ERα system provided new insights into how the different components interact to regulate network-level behavior.

As an initial approach, we used a purely empirical fit to the experimental data and a simplified model structure with no feedback. This analysis indicated that the transcription rate of nRNA (SnRNA) must undergo a significant decrease after E2 treatment for the model to capture the experimentally observed drop in nRNA and mRNA (Fig. 1). Based on this and the knowledge that ERα is phosphorylated at S118 in response to the binding of E2 (54, 55), we hypothesized that incorporation of a potential feedback mechanism that decreased the value of SnRNA in proportion to the concentration of pERα could capture this behavior while maintaining self-consistency between parameters for E2-treated and untreated conditions. Incorporating this feedback mechanism into the model structure allowed the model to capture observed trends in nRNA and mRNA (Fig. 2). E2-induced genomic repression of ESR1 expression was previously shown to require ERα binding to the ESR1 promoter and chromatin modification (34), but studies to establish the events in estrogen signaling required for transcriptional regulation have been hindered by the complexity of the endogenous promoter. Using our model prediction of a role for pERα-S118, we rationally designed a ChIP experiment and corroborated that pERα-S118 can bind to the ESR1 promoter (Fig. 3). This interaction has not, to the best of our knowledge, been shown before and establishes a novel role for ERα phosphorylation in transcriptional regulation of ESR1. The conditions used for this ChIP analysis were identical to those we previously used to demonstrate that E2 treatment leads to recruitment of ERα to the proximal promoter of ESR1, repressive chromatin marks, and loss of Pol II (34). Combined, these experimental studies support the model-proposed mechanism of pERα-dependent repression of ESR1 transcription. It will be interesting to determine if phosphorylation at other sites on ERα contributes to additional tuning capacity (37), but this awaits availability of phospho-specific reagents.

In the ERα genomic pathway, coregulators are recruited by ERα to form multiprotein complexes that stimulate or repress gene expression (56); therefore, it is likely that the binding of pERα-S118 to the ESR1 promoter also recruits coregulators. To account for this possibility, the model uses the feedback tuning parameter a, where the magnitude of a impacts how strongly a given amount of pERα affects ESR1 transcription. Sensitivity analysis revealed that the most effective mechanism to lower steady-state tERα was to increase a (Fig. 6), suggesting that the feedback mechanism could represent a therapeutic target. It will therefore be important in future studies to identify these coregulators and the kinetics of their interactions with pERα and the ESR1 promoter. However, it is important to recognize that our model was trained on data from a single cell line; in contrast, we would expect variation in multiple parameters between different patients. The results from a multivariate sensitivity analysis (Supplemental Fig. S4) suggest that increasing a will remain an effective method to decrease ERα in conditions with elevated k1 or decreased kd,2 or kd,3 but not elevated k2 or decreased k3 or kd,1.

Although the negative feedback at nascent RNA transcription was necessary to capture ESR1 behavior, an increased pERα degradation rate was essential to capture protein dynamics (Fig. 4), with the fit for kd,3 greater than kd,2 by nearly an order of magnitude in both the empirically fit model and the combined mechanism model (Table 1). This elevated degradation rate contributed strongly to the rapid decrease in tERα following E2 treatment. An increase in degradation as a result of phosphorylation is qualitatively consistent with what is currently known about the mechanisms responsible for ERα degradation (57). Our sensitivity analysis (Fig. 6) demonstrated that kd,3 had a nonsymmetric effect on tERα protein levels, with the small decreases in kd,3 resulting in larger increases in tERα levels. The multivariate sensitivity analysis suggested that this asymmetry is a result of the specific dependence of the feedback mechanism on pERα and not tERα levels (Supplemental Fig. S4). This is in agreement with previous studies that showed that mutation of the S118 site disrupted estrogen-induced decreases in tERα protein in a system of exogenously expressed ERα where control of ESR1 is not a variable (58). Additional studies showed that pS118 is specifically recognized by the ubiquitination complexes, E6AP and COP9 signalosome, which specifically target the phosphorylated receptor for degradation (59, 60). Together with the latter studies, our analysis supports the notion that components of the ubiquitination machinery that target pERα could provide novel avenues to decrease tERα levels in patients that are ERα positive, but tamoxifen resistant (61).

The value of mathematical modeling has not been fully recognized in studies of ERα (62). Mass-action kinetics such as those used in our study have been previously used to study ERα cross-talk with growth factor receptors (63). In this model, phosphorylation of ERα occurs independently of E2 treatment, providing a mechanism to examine E2-independent cell proliferation such as that seen in the development of endocrine therapy resistance in breast cancer. ERα-dependent gene regulation in response to E2 has also been modeled by a mass-action kinetic model of E2 binding to ERα, dimer formation, and transcription of target genes (45). A key assumption of this model is that the rate of gene transcription will be proportional to the level of active E2-ERα complexes. However, neither of these studies incorporated regulation of ERα levels in response to E2 treatment, which could significantly alter model predictions.

Our results demonstrate the ability of even simple models to identify new facets of cellular network regulation. An important biologic finding revealed through our model is the orchestration of multiple regulatory pathways governing receptor expression via phosphorylation. Although multiple sites of phosphorylation have been identified in ERα (37), phosphorylation at S118 is the best documented (64). Phosphorylation of S118 is primarily associated with increased transcriptional activity of the ligand-independent transactivation function, AF1. Additionally, E2-induced phosphorylation of S118 is necessary for full transcriptional activity of ERα, and phosphorylation-deficient mutation of this site significantly impairs E2-regulated transcription. Therefore, it appears that phosphorylation of S118 plays a unique role in balancing estrogen’s actions by promoting ERα-dependent transcriptional activity while simultaneously suppressing ERα levels through genomic control of ESR1 transcription and nongenomic, proteolytic control of ERα degradation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (Grant CBET-0951613; to P.K.K.) and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (Director's New Innovator Award Program, Grant 1DP2CA195766-01; to P.K.K.) and (National Cancer Institute, Grant CA-159578; to E.T.A.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- E2

17-β-estradiol

- ERα

estrogen receptor-α

- ESR1

estrogen receptor-1

- nRNA

nascent RNA

- pERα

phosphorylated ERα

- qRT-PCR

quantitative RT-PCR

- tERα

total ERα

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shanle E. K., Xu W. (2010) Selectively targeting estrogen receptors for cancer treatment. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 62, 1265–1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zwart W., Theodorou V., Carroll J. S. (2011) Estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: a multidisciplinary challenge. Systems Biol Med. 3, 216–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giuliano M., Schifp R., Osborne C. K., Trivedi M. V. (2011) Biological mechanisms and clinical implications of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Breast 20(Suppl 3), S42–S49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deroo B. J., Korach K. S. (2006) Estrogen receptors and human disease. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 561–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couse J. F., Korach K. S. (1999) Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr. Rev. 20, 358–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jozwik K. M., Carroll J. S. (2012) Pioneer factors in hormone-dependent cancers. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 381–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musgrove E. A., Sutherland R. L. (2009) Biological determinants of endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 631–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patani N., Martin L. A., Dowsett M. (2013) Biomarkers for the clinical management of breast cancer: international perspective. Int. J. Cancer 133, 1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bordeaux J. M., Cheng H., Welsh A. W., Haffty B. G., Lannin D. R., Wu X., Su N., Ma X. J., Luo Y., Rimm D. L. (2012) Quantitative in situ measurement of estrogen receptor mRNA predicts response to tamoxifen. PLoS ONE 7, e36559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lumachi F., Brunello A., Maruzzo M., Basso U., Basso S. M. (2013) Treatment of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Curr. Med. Chem. 20, 596–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barone I., Brusco L., Fuqua S. A. (2010) Estrogen receptor mutations and changes in downstream gene expression and signaling. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 2702–2708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Leeuw R., Neefjes J., Michalides R. (2011) A role for estrogen receptor phosphorylation in the resistance to tamoxifen. Int. J. Breast Cancer 2011, 232435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clarke R., Leonessa F., Welch J. N., Skaar T. C. (2001) Cellular and molecular pharmacology of antiestrogen action and resistance. Pharmacol. Rev. 53, 25–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ring A., Dowsett M. (2004) Mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 11, 643–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García-Becerra R., Santos N., Díaz L., Camacho J. (2012) Mechanisms of resistance to endocrine therapy in breast cancer: focus on signaling pathways, miRNAs and genetically based resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 108–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osborne C. K. (1998) Steroid hormone receptors in breast cancer management. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 51, 227–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams C., Lin C. Y. (2013) Oestrogen receptors in breast cancer: basic mechanisms and clinical implications. Ecancermedicalscience 7, 370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammond M. E., Hayes D. F., Dowsett M., Allred D. C., Hagerty K. L., Badve S., Fitzgibbons P. L., Francis G., Goldstein N. S., Hayes M., Hicks D. G., Lester S., Love R., Mangu P. B., McShane L., Miller K., Osborne C. K., Paik S., Perlmutter J., Rhodes A., Sasano H., Schwartz J. N., Sweep F. C., Taube S., Torlakovic E. E., Valenstein P., Viale G., Visscher D., Wheeler T., Williams R. B., Wittliff J. L., Wolff A. C. (2010) American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for immunohistochemical testing of estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 134, 907–922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Welsh A. W., Moeder C. B., Kumar S., Gershkovich P., Alarid E. T., Harigopal M., Haffty B. G., Rimm D. L. (2011) Standardization of estrogen receptor measurement in breast cancer suggests false-negative results are a function of threshold intensity rather than percentage of positive cells. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 2978–2984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoker B. S., Jarvis C., Clarke R. B., Anderson E., Hewlett J., Davies M. P., Sibson D. R., Sloane J. P. (1999) Estrogen receptor-positive proliferating cells in the normal and precancerous breast. Am. J. Pathol. 155, 1811–1815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan S. A., Rogers M. A., Khurana K. K., Meguid M. M., Numann P. J. (1998) Estrogen receptor expression in benign breast epithelium and breast cancer risk. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 90, 37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorpe S. M., Christensen I. J., Rasmussen B. B., Rose C. (1993) Short recurrence-free survival associated with high oestrogen receptor levels in the natural history of postmenopausal, primary breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 29A, 971–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fabris G., Marchetti E., Marzola A., Bagni A., Querzoli P., Nenci I. (1987) Pathophysiology of estrogen receptors in mammary tissue by monoclonal antibodies. J. Steroid Biochem. 27, 171–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markopoulos C., Berger U., Wilson P., Gazet J. C., Coombes R. C. (1988) Oestrogen receptor content of normal breast cells and breast carcinomas throughout the menstrual cycle. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 296, 1349–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ricketts D., Turnbull L., Ryall G., Bakhshi R., Rawson N. S., Gazet J. C., Nolan C., Coombes R. C. (1991) Estrogen and progesterone receptors in the normal female breast. Cancer Res. 51, 1817–1822 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romain S., Chinot O., Guirou O., Soulliere M., Martin P. M. (1994) Biological heterogeneity of ER-positive breast cancers in the post-menopausal population. Int. J. Cancer 59, 17–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Denton R. R., Koszewski N. J., Notides A. C. (1992) Estrogen receptor phosphorylation. Hormonal dependence and consequence on specific DNA binding. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 7263–7268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar V., Chambon P. (1988) The estrogen receptor binds tightly to its responsive element as a ligand-induced homodimer. Cell 55, 145–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gronemeyer H. (1991) Transcription activation by estrogen and progesterone receptors. Annu. Rev. Genet. 25, 89–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tremblay G. B., Giguère V. (2002) Coregulators of estrogen receptor action. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 12, 1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Read L. D., Greene G. L., Katzenellenbogen B. S. (1989) Regulation of estrogen receptor messenger ribonucleic acid and protein levels in human breast cancer cell lines by sex steroid hormones, their antagonists, and growth factors. Mol. Endocrinol. 3, 295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cidlowski J. A., Muldoon T. G. (1978) The dynamics of intracellular estrogen receptor regulation as influenced by 17beta-estradiol. Biol. Reprod. 18, 234–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan S. A., Sachdeva A., Naim S., Meguid M. M., Marx W., Simon H., Halverson J. D., Numann P. J. (1999) The normal breast epithelium of women with breast cancer displays an aberrant response to estradiol. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prevent. 8, 867–872 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ellison-Zelski S. J., Solodin N. M., Alarid E. T. (2009) Repression of ESR1 through actions of estrogen receptor alpha and Sin3A at the proximal promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 4949–4958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valley C. C., Solodin N. M., Powers G. L., Ellison S. J., Alarid E. T. (2008) Temporal variation in estrogen receptor-alpha protein turnover in the presence of estrogen. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 40, 23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alarid E. T., Bakopoulos N., Solodin N. (1999) Proteasome-mediated proteolysis of estrogen receptor: a novel component in autologous down-regulation. Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 1522–1534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atsriku C., Britton D. J., Held J. M., Schilling B., Scott G. K., Gibson B. W., Benz C. C., Baldwin M. A. (2009) Systematic mapping of posttranslational modifications in human estrogen receptor-alpha with emphasis on novel phosphorylation sites. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 8, 467–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Björnström L., Sjöberg M. (2005) Mechanisms of estrogen receptor signaling: convergence of genomic and nongenomic actions on target genes. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 833–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maniatis T., Reed R. (2002) An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature 416, 499–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neugebauer K. M. (2002) On the importance of being co-transcriptional. J. Cell Sci. 115, 3865–3871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khodor Y. L., Rodriguez J., Abruzzi K. C., Tang C. H., Marr M. T. II, Rosbash M. (2011) Nascent-seq indicates widespread cotranscriptional pre-mRNA splicing in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 25, 2502–2512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beyer A. L., Osheim Y. N. (1988) Splice site selection, rate of splicing, and alternative splicing on nascent transcripts. Genes Dev. 2, 754–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ben-Tabou de-Leon S., Davidson E. H. (2009) Modeling the dynamics of transcriptional gene regulatory networks for animal development. Dev. Biol. 325, 317–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen A. A., Kalisky T., Mayo A., Geva-Zatorsky N., Danon T., Issaeva I., Kopito R. B., Perzov N., Milo R., Sigal A., Alon U. (2009) Protein dynamics in individual human cells: experiment and theory. PLoS ONE 4, e4901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lebedeva G., Yamaguchi A., Langdon S. P., Macleod K., Harrison D. J. (2012) A model of estrogen-related gene expression reveals non-linear effects in transcriptional response to tamoxifen. BMC Syst. Biol. 6, 138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schwanhäusser B., Busse D., Li N., Dittmar G., Schuchhardt J., Wolf J., Chen W., Selbach M. (2011) Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen W. W., Schoeberl B., Jasper P. J., Niepel M., Nielsen U. B., Lauffenburger D. A., Sorger P. K. (2009) Input-output behavior of ErbB signaling pathways as revealed by a mass action model trained against dynamic data. Mol. Syst. Biol. 5, 239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoeberl B., Eichler-Jonsson C., Gilles E. D., Müller G. (2002) Computational modeling of the dynamics of the MAP kinase cascade activated by surface and internalized EGF receptors. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 370–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kholodenko B. N., Demin O. V., Moehren G., Hoek J. B. (1999) Quantification of short term signaling by the epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30169–30181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alarid E. T. (2006) Lives and times of nuclear receptors. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1972–1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matthias Ruth B. H. (1997) Modeling Dynamic Biological Systems, Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aldridge B. B., Burke J. M., Lauffenburger D. A., Sorger P. K. (2006) Physicochemical modelling of cell signalling pathways. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1195–1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harvey J. M., Clark G. M., Osborne C. K., Allred D. C. (1999) Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 17, 1474–1481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ali S., Metzger D., Bornert J. M., Chambon P. (1993) Modulation of transcriptional activation by ligand-dependent phosphorylation of the human oestrogen receptor A/B region. EMBO J. 12, 1153–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen D., Riedl T., Washbrook E., Pace P. E., Coombes R. C., Egly J. M., Ali S. (2000) Activation of estrogen receptor alpha by S118 phosphorylation involves a ligand-dependent interaction with TFIIH and participation of CDK7. Mol. Cell 6, 127–137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.May F. E. (2014) Novel drugs that target the estrogen-related receptor alpha: their therapeutic potential in breast cancer. Cancer Manage. Res. 6, 225–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marsaud V., Gougelet A., Maillard S., Renoir J. M. (2003) Various phosphorylation pathways, depending on agonist and antagonist binding to endogenous estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha), differentially affect ERalpha extractability, proteasome-mediated stability, and transcriptional activity in human breast cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 17, 2013–2027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Valley C. C., Métivier R., Solodin N. M., Fowler A. M., Mashek M. T., Hill L., Alarid E. T. (2005) Differential regulation of estrogen-inducible proteolysis and transcription by the estrogen receptor alpha N terminus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 5417–5428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rajbhandari P., Schalper K. A., Solodin N. M., Ellison-Zelski S. J., Ping Lu K., Rimm D. L., Alarid E. T. (2014) Pin1 modulates ERα levels in breast cancer through inhibition of phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination and degradation. Oncogene 33, 1438–1447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Calligé M., Kieffer I., Richard-Foy H. (2005) CSN5/Jab1 is involved in ligand-dependent degradation of estrogen receptor alpha by the proteasome. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 4349–4358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou W., Slingerland J. M. (2014) Links between oestrogen receptor activation and proteolysis: relevance to hormone-regulated cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 14, 26–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tyson J. J., Baumann W. T., Chen C., Verdugo A., Tavassoly I., Wang Y., Weiner L. M., Clarke R. (2011) Dynamic modelling of oestrogen signalling and cell fate in breast cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11, 523–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen C., Baumann W. T., Clarke R., Tyson J. J. (2013) Modeling the estrogen receptor to growth factor receptor signaling switch in human breast cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 587, 3327–3334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Le Romancer M., Poulard C., Cohen P., Sentis S., Renoir J. M., Corbo L. (2011) Cracking the estrogen receptor’s posttranslational code in breast tumors. Endocr. Rev. 32, 597–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.