Abstract

Background

Whole-exome sequencing has shown that lung adenocarcinoma (LAC) can be driven by mutant genes, including TP53, P16, and Smad4. The aim of this study was to clarify protein alterations of P53, P16, and Smad4 and to explore their correlations between the protein alterations and clinical outcome.

Methods

We investigated associations among P53 mutant (P53Mut) expression, and P16 and Smad4 loss-of-expression, with clinical outcome in 120 LAC patients who underwent curative resection, using immunohistochemical (IHC) methods.

Results

Of the 120 patients, 76 (63.3%) expressed P53Mut protein, whereas 54 (45.0%) loss of P16 expressed and 75 (62.5%) loss of Smad4 expressed. P53Mut expression was associated with tumor size (P = 0.041) and pathological stage (P = 0.025). Loss of P16 expression was associated with lymph node metastasis (P = 0.001) and pathological stage (P < 0.001). Loss of Smad4 expression was associated with tumor size (P = 0.033), lymph node metastasis (P = 0.014), pathological stage (P = 0.017), and tumor differentiation (P = 0.022). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that tumor size (P = 0.031), lymph node metastasis (P < 0.001), pathological stage (P < 0.001), P53Mut protein expression (P = 0.038), and loss of p16 or Smad4 expression (P < 0.001) were significantly associated with shorter overall survival(OS), whereas multivariate analysis indicated that lymph node metastasis (P = 0.014) and loss of p16 or Smad4 expression (P < 0.001) were independent prognostic factors. Analysis of protein combinations showed patients with more alterations had poorer survival (P < 0.001). Spearman correlation analysis showed that loss of Smad4 expression inversely correlated with expression of P53Mut (r = −0.196, P = 0.032) and positively with lost P16 expression (r =0.182, P = 0.047).

Conclusions

The findings indicate that IHC status of P53Mut, P16, and Smad4 may predict patient outcomes in LAC.

Keywords: Lung adenocarcinoma, Mutant P53, P16, Smad4, Immunohistochemistry, Prognosis

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1], and the proportion of lung cancer patients with lung adenocarcinoma (LAC) is reportedly increasing [2]. Survival rates for LAC have improved dramatically in the last decade, owing to identification of driver mutations in LAC [3]. For example, EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor have been approved for treatment of LACs that carry EGFR gene mutations, which has greatly improved the prognosis of such patients [4,5]. Discovery of genetic biomarkers for cancers is expected to rapidly expand [6]. Identified driver gene alteration for LAC currently includes mutations of EGFR, KRAS, PIK3CA, BRAF, STK11, DDR2, TP53, Smad4, P16, RET, and ALK, among others [7-11]. As driver genes are found, their relationships to each other and to patients’ prognoses must be verified.

Genetic alterations of P53, P16, and Smad4 have been found in pancreatic cancer, and appear to be strongly associated with its malignant behavior [12-14]. In our previous study with a genetically engineered mouse model, we found P53Mut’s potentially malignant gain-of-function was promoted by inactivating the inhibitory actions of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), caused by downregulation of smad4, which in turn was synergistically caused by P53Mut and deficient P16/P19. Although these three genes have been studied individually in LAC, little is known about how they interact, or their combined effect on prognosis. Here, we investigated mutant P53, P16, and Smad4 in LAC by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining and correlated these mutations with clinicopathological features and patients’ OS.

Methods

Patients and tissue samples

This study included 120 patients with LAC who underwent surgical resection between January 2007 and March 2009 at the Nanjing Medical University-Affiliated Cancer Hospital, Nanjing, China. All patients had complete medical records and complete follow-up data. The last follow-up date was March 2014. Patients who died of causes other than LAC before this date were excluded. Their clinicopathological data were collected from medical records and follow-up data were obtained through telephone interviews or by consulting the police population information system. These patients’ mean age was 59.4 years (range: 35 to 85 years), including 58 men and 62 women. Before their surgeries, all patients underwent CT scans or B-ultrasonic examinations to exclude locoregional or widespread metastases. All patients underwent radical resections; no patients received radiotherapy or chemotherapy before surgery. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University.

IHC analyses

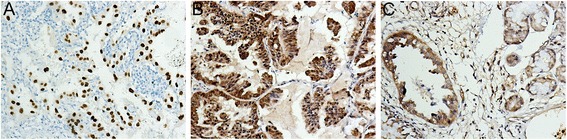

Specimens of primary LAC from 120 patients were cut into 5-μm tissue sections and deparaffinized by routine methods. The slides were steamed for 20 min in sodium citrate buffer. After cooling for 5 min, the slides were IHC stained for P53Mut, P16 and Smad4. At least five different distinct regions of the primary tumor were IHC-labeled for each case to evaluate for potential heterogeneity. IHC labeling was carried out using P53Mut mouse monoclonal antibody (clone SC126 diluted 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, USA), CDKN2A/P16 rabbit monoclonal antibody (clone SC468 diluted 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and Smad4/Dpc4 mouse monoclonal antibody (clone SC-7966, diluted 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as reported [15]. Labeling was detected by adding biotinylated secondary antibodies. Positive controls were taken from sections known to be positive from pancreatic carcinoma specimens. For the negative controls, 1% PBS was used in place of primary antibodies. Results were evaluated independently by two experienced pathologists. P53Mut was considered positive when ≥10% of tumor cell nuclei showed strong staining with a dark brown color. P16 and Smad4 were considered positive when ≥ 20% of tumor cell cytoplasm and nuclei showed staining with a brown color (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

P53 Mut , P16, and Smad4 expression in lung adenocarcinoma, shown immunohistochemically (SP × 200). (A) P53Mut positive staining detected in nucleus. (B) P16 positive staining detected in cytoplasm and nucleus. (C) Smad4 positive staining detected in cytoplasm and nucleus.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of group differences was performed using χ2 tests. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates were estimated using life tables; OS was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the differences were assessed by the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were generated for multivariate analysis. Correlation analysis used the Spearman test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 17.0, SPSS).

Results

Clinicopathological features and outcome

Of the 120 patients (58 men and 62 women), 47 (39.2%) were older than 60 years at the time of surgery; their mean and median ages were 59.4 and 58 years, respectively. At the last follow-up date (March 2014), 25 (20.8%) patients were still alive. Median OS was 35.14 months, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates of 61.0%, 39.0%, and 33.0%, respectively. In all 120 patients, 24 (20.0%) had T1 tumors, 73 (60.8%) had T2 tumors, and 23 (19.2%) had T3/4 tumors. Lymph node metastases were present in 49/120 (40.8%). We found 26.7% of tumors were well differentiated, 34.1% were moderately differentiated, and 39.2% were poorly differentiated. Only 13 (10.8%) patients had pleural invasion. Of the 120 patients, 37 (30.8%), 47 (39.2%), 36 (30.0%), and 0 (0%) presented with the Union for International Cancer Control stage I, II, III and IV disease, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mutant P53 , P16 , and Smad4 expression in relation to clinicopathological parameters ( n = 120)

| Mutant P53 expression | P | P16 expression | P | Smad4 expression | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (%) | Positive (%) | Negative (%) | Positive (%) | Negative (%) | Positive (%) | ||||

| Age ≤60 year | 26 (35.6%) | 47 (64.4%) | 0.766 | 34 (46.6%) | 39 (53.4%) | 0.666 | 47 (64.4%) | 26 (35.6%) | 0.595 |

| Age >60 year | 18 (38.3%) | 29 (61.7%) | 20 (42.6%) | 27 (57.4%) | 28 (59.6%) | 19 (40.4%) | |||

| Male | 25 (43.1%) | 33 (56.9%) | 0.157 | 27 (46.6%) | 31 (53.4%) | 0.741 | 32 (55.2%) | 26 (44.8%) | 0.109 |

| Female | 19 (30.6%) | 43 (69.4%) | 27 (43.5%) | 35 (56.5%) | 43 (69.4%) | 19 (30.6%) | |||

| Tumor size (cm) | |||||||||

| T1 (≤3) | 14 (58.3%) | 10 (41.7%) | 0.041 | 8 (33.3%) | 16 (66.7%) | 0.392 | 11 (45.8%) | 13 (54.2%) | 0.033 |

| T2 (>3 ≤ 7) | 24 (32.9%) | 49 (67.1%) | 34 (46.6%) | 39 (53.4%) | 45 (61.6%) | 28 (38.4%) | |||

| T3/4 (>7) | 6 (26.1%) | 17 (73.9%) | 12 (52.2%) | 11 (47.8%) | 19 (82.6%) | 4 (17.4%) | |||

| Lymph nodes | |||||||||

| Negative | 27 (38.0%) | 44 (62.0%) | 0.709 | 23 (32.4%) | 48 (67.6%) | 0.001 | 38 (53.5%) | 33 (46.5%) | 0.014 |

| Positive | 17 (34.7%) | 32 (65.3%) | 31 (63.3%) | 18 (36.7%) | 37 (75.5%) | 12 (24.5%) | |||

| Differentiation | |||||||||

| Well | 16 (50.0%) | 16 (50.0%) | 0.188 | 13 (40.6%) | 19 (59.4%) | 0.077 | 15 (46.9%) | 17 (53.1%) | 0.022 |

| Moderate | 13 (31.7%) | 28 (68.3%) | 14 (34.1%) | 27 (65.9%) | 24 (58.5%) | 17 (41.5%) | |||

| Poor | 15 (31.9%) | 32 (68.1%) | 27 (57.4%) | 20 (42.6%) | 36 (76.6%) | 11 (23.4%) | |||

| Pleural invasion | |||||||||

| Negative | 39 (36.4%) | 68 (63.6%) | 0.887 | 47 (43.9%) | 60 (56.1%) | 0.497 | 66 (61.7%) | 41 (38.3%) | 0.596 |

| Positive | 5 (38.5%) | 8 (61.5%) | 7 (53.8%) | 6 (46.2%) | 9 (69.2%) | 4 (30.8%) | |||

| Pathological stage | |||||||||

| Stage I | 20 (54.1%) | 17 (45.9%) | 0.025 | 11 (29.7%) | 26 (70.3%) | <0.001 | 18 (48.6%) | 19 (51.4%) | 0.017 |

| Stage II | 15 (31.9%) | 32 (68.1%) | 17 (36.2%) | 30 (63.8%) | 28 (59.6%) | 19 (40.4%) | |||

| Stage III | 9 (25.0%) | 27 (75.0%) | 26 (72.2%) | 10 (27.8%) | 29 (80.6%) | 7 (19.4%) | |||

The italicized values indicate P values less than 0.05.

Protein alterations in LAC

Using IHC labeling, we detected positive P53Mut in 76 patients (63.3%), negative P16 in 54 patients (45.0%), negative Smad4 in 75 patients (62.5%) (Table 1), alterations of all three proteins (P53mut+/P16-/Smad4-) in 28 (23.3%) patients, and normal expression of the three proteins (P53mut-/P16+/Smad4+) in 17 (14.2%) patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinicopathological parameters and overall survival in 120 patients

| Mean (month) | Median (month) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | P | |

| Age (year) | ||||||

| ≤60 | 73 | 41.520 | 35.148 to 47.892 | 37.000 | 24.907 to 49.093 | 0.883 |

| >60 | 47 | 40.396 | 32.890 to 47.902 | 30.000 | 17.931 to 42.069 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| M | 58 | 41.563 | 34.672 to 48.454 | 36.000 | 18.585 to 53.415 | 0.917 |

| F | 62 | 40.535 | 33.685 to 47.385 | 30.000 | 17.461 to 42.539 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||

| T1 (≤3) | 24 | 49.125 | 40.950 to 57.300 | 45.000 | 31.797 to 58.203 | 0.031 |

| T2 (3 to 7) | 73 | 41.959 | 35.673 to 48.245 | 35.000 | 17.325 to 52.675 | |

| T3/4 (>7) | 23 | 28.587 | 17.986 to 39.188 | 15.000 | 10.340 to 19.660 | |

| Lymph nodes | ||||||

| Negative | 71 | 50.437 | 44.488 to 56.387 | 49.000 | 39.870 to 58.130 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 49 | 27.497 | 20.990 to 34.003 | 17.000 | 13.571 to 20.429 | |

| Differentiation | ||||||

| Well | 32 | 48.869 | 40.548 to 57.190 | 49.000 | 33.785 to 64.215 | 0.067 |

| Moderate | 41 | 43.975 | 35.538 to 52.412 | 35.000 | 16.180 to 53.820 | |

| Poor | 47 | 33.009 | 25.461 to 40.556 | 21.000 | 14.283 to 27.717 | |

| Pleural invasion | ||||||

| Negative | 107 | 42.446 | 37.213 to 47.680 | 37.000 | 25.020 to 48.980 | 0.091 |

| Positive | 13 | 31.385 | 18.335 to 44.434 | 23.000 | 15.954 to 30.046 | |

| Stage | ||||||

| I | 37 | 57.224 | 49.411 to 65.036 | 55.000 | 42.364 to 67.636 | <0.001 |

| II | 47 | 39.400 | 31.965 to 46.836 | 30.000 | 20.613 to 39.387 | |

| III | 36 | 27.111 | 19.609 to 34.613 | 16.000 | 11.296 to 20.704 | |

| Mutant P53 | ||||||

| Negative | 44 | 47.794 | 39.707 to 55.881 | 47.000 | 29.665 to 64.335 | 0.038 |

| Positive | 76 | 37.172 | 31.317 to 43.027 | 30.000 | 20.511 to 39.487 | |

| P16 | ||||||

| Negative | 54 | 28.352 | 22.689 to 34.014 | 20.000 | 14.399 to 25.601 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 66 | 51.359 | 44.929 to 57.788 | 56.000 | 40.849 to 71.151 | |

| Smad4 | ||||||

| Negative | 75 | 30.185 | 25.074 to 35.297 | 21.000 | 15.346 to 26.654 | <0.001 |

| Positive | 45 | 59.678 | 52.491 to 66.866 | 66.000 | 50.912 to 81.088 | |

| Gene expression combinations | <0.001 | |||||

| P53mut−/P16+/Smad4− | 11 | 43.364 | 27.766 to 58.961 | 47.000 | 13.553 to 80.447 | |

| P53mut−/P16+/Smad4+ | 17 | 63.824 | 54.411 to 73.236 | 74.000 | 44.191 to 103.809 | |

| P53mut−/P16−/Smad4+ | 5 | 53.800 | 33.542 to 74.058 | 49.000 | 38.265 to 59.735 | |

| P53mut−/P16−/Smad4− | 11 | 22.000 | 14.791 to 29.209 | 21.000 | 14.746 to 27.254 | |

| P53mut+/P16+/Smad4− | 25 | 41.451 | 31.906 to 50.997 | 32.000 | 12.416 to 51.584 | |

| P53mut+/P16+/Smad4+ | 13 | 58.011 | 44.148 to 71.874 | 66.000 | 38.979 to 93.021 | |

| P53mut+/P16−/Smad4+ | 10 | 52.100 | 38.216 to 65.984 | 54.000 | 27.658 to 80.342 | |

| P53mut+/P16−/Smad4− | 28 | 18.185 | 14.057 to 22.313 | 15.000 | 12.976 to 17.024 | |

The italicized values indicate P values less than 0.05.

Protein alterations and clinicopathological features

Positive IHC labeling of P53Mut was significantly linked to tumor size (P = 0.041) and pathological stage (P = 0.025). Negative P16 IHC labeling was significantly associated with lymphatic metastasis (P = 0.001) and pathological stage (P < 0.001). Negative Smad4 IHC labeling was associated with tumor size (P = 0.033), lymph node metastasis (P = 0.014), differentiation (P = 0.022), and pathological stage (P = 0.017) (Table 1).

Clinicopathological features and OS

Univariate analysis results were based on log-rank tests of clinicopathological characteristics in relation to OS. Tumor size (P = 0.031), lymph node metastasis (P < 0.001), and pathological stage (P < 0.001) were significantly associated with shorter OS (Table 2).

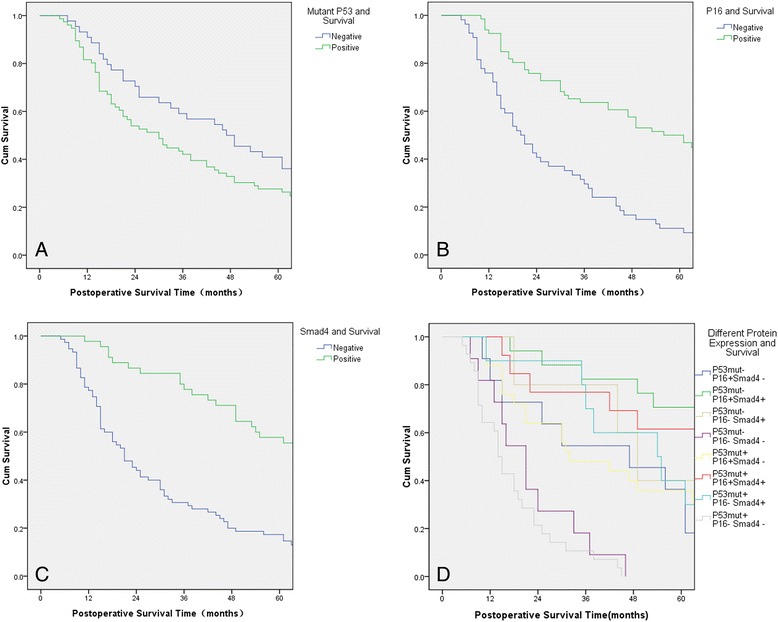

Protein alterations and OS

Loss of P16 and Smad4 IHC labeling was associated with a significantly shorter OS (P < 0.001). There were significant differences in positive labeling of P53Mut with regard to OS (P = 0.038). Next, based on the number of altered proteins, we classified the patients into eight groups: P53mut−/P16+/Smad4− (n = 11); P53mut−/P16+/Smad4+ (n = 17); P53mut−/P16−/Smad4+ (n = 5); P53mut−/P16−/Smad4− (n = 11); P53mut+/P16+/Smad4− (n = 25); P53mut+/P16+/Smad4+ (n = 13); P53mut+/P16−/Smad4+ (n = 10); and P53mut+/P16−/Smad4− (n = 28). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that the P53mut−/P16+/Smad4+ group had the longest OS and the P53 mut+/P16−/Smad4- group had the shortest OS (P < 0.001). The higher number of altered proteins robustly reflected major differences in survival outcome. The results showed patients with more protein alterations had poorer survival rates (Table 2, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Changes in protein expression and overall survival (OS). (A) Patients’ postoperative OS curves by P53 Mut expression. (B) Patients’ postoperative OS curves by P16 expression. (C) Patients’ postoperative OS curves by Smad4 expression. (D) Patients’ postoperative OS curves by different protein expression combinations.

Multivariate analyses of factors affecting OS

Multivariate models using Cox proportional hazards analysis were conducted with the parameters that were significant at the P < 0.05 level on univariate analysis using log-rank tests. Multivariate analysis showed that lymph node metastasis (relative risk (RR): 2.222, P = 0.014), negative Smad4 IHC labeling (RR: 0.269, P < 0.001) and negative P16 IHC labeling (RR: 0.360, P < 0.001) were independent predictors of OS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors for overall survival ( n = 120)

| Factors | Relative risk | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size | 1.423 | 0.990 to 2.044 | 0.056 |

| Status of lymph nodes metastasis | 2.222 | 1.172 to 4.210 | 0.014 |

| Pathological stage | 1.075 | 0.706 to 1.636 | 0.735 |

| Positive P53 Mut labeling | 1.320 | 0.834 to 2.091 | 0.236 |

| Negative P16 labeling | 0.360 | 0.226 to 0.572 | <0.001 |

| Negative Smad4 labeling | 0.269 | 0.165 to 0.441 | <0.001 |

The italicized values indicate P values less than 0.05.

Correlation analysis of P53mut, P16 and Smad4 expression

Spearman analysis indicated that Smad4 expression was negatively correlated with P53mut expression (r = −0.196, P = 0.032) and positively correlated with P16 expression (r = 0.182, P = 0.047), whereas P16 expression and P53mut expression showed no correlation (Table 4).

Table 4.

Relationships among mutant P53 , P16 , and Smad4

| TP53 | P16 | Smad4 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutant P53 | |||

| r | 1.000 | −0.132 | −0.196 |

| P | - | 0.150 | 0.032 |

| P16 | |||

| r | −0.132 | 1.000 | 0.182 |

| P | 0.150 | - | 0.047 |

| Smad4 | |||

| r | −0.196 | 0.182 | 1.000 |

| P | 0.032 | 0.047 | - |

The italicized values indicate P values less than 0.05; r, Pearson correlation.

Discussion

The molecular basis of lung cancer is complex and heterogeneous. Over the last decades, identification of driver mutations in LAC has led to the development of targeted agents, several of which are in clinical trials and are already approved for clinical use [6].

Recent whole-exome sequencing studies of numerous human cancers have conclusively shown TP53 to be the most frequently mutated gene in human cancers [15,16]. The P53 protein and its downstream pathways are important in preventing tumor formation, but TP53 mutation is common in cancers. Moreover, unlike other tumor-suppressor genes that only lose their tumor-suppressor functions, the P53Mut gene may endow its mutant protein with new activities that actively promote tumor progression and increased resistance to anticancer treatments [17]. Because P53Mut proteins have longer half-life than wild-type P53, which can accumulate in the nucleus, we only can detect P53Mut proteins by IHC. Although Ding et al. found that 45% of LAC patients had TP53 mutations [18], the clinical implications of mutant P53 in LAC may still be conflicting. P53 alterations are reported to predict poor survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [19-22]. However, Ahn et al. reported that P53Mut protein expression did not correlate with OS in NSCLC [23]. In our study, the P53Mut frequency was 63.3%, which was higher than that previously reported. The results of univariate analyses showed that higher P53Mut IHC expression predicted shorter OS. However, the multivariate analysis indicated that higher P53Mut expression did not independently predict poorer OS. Furthermore, mice that express P53Mut reportedly have a more aggressive and metastatic tumor profile than that of mice with null or wild-type P53 [24,25]. Conversely, Jackson et al. reported that P53Mut protein in lung showed no detectable gain-of-function activity [26]. Although the present study found no relationship between P53Mut and lymph node metastasis, P53Mut expression was linked to tumor size and pathological stage. The role of TP53 mutations as a prognostic marker in NSCLC were reported conflicting. This may be due to the molecular heterogeneity and differing functional effects specific to various TP53 genotypes, methodological issues related to the assessment of mutation status, and design issues related to small sample size and nonhomogeneous groups of patients. Furthermore, the context in which these mutations occur, the initiating events and other secondary molecular alterations, may matter as well. Hence, a larger sample size and more complete experiment methods will be required in the future to obtain reliable and consistent results.

P16 is an important tumor-suppressor gene that has been found to affect cell-cycle by inactivating the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor [27-29]. P16 alterations in NSCLC were mainly homozygous deletions, promoter hypermethylation and point mutations [30]. The relationship between P16 expression and lung cancer is still unclear. Although some studies reported that P16 expression increased in NSCLC [31,32], another found the P16 gene to be a commonly inactivated tumor-suppressor gene in NSCLC, and altered P16 and P53 genes to be frequently found in the same tumors [30]. In this study, loss of P16 was linked to lymph node metastasis and pathological stage, which accords with the study that found complete P16 inactivation in advanced NSCLC [30].

Smad4 is a tumor-suppressor gene with a key role in the TGF-β signaling pathway [33]. Because of its mediatory role in the growth-inhibitory effects of TGF-β in normal cells and its loss in some tumors, Smad4 is considered a tumor-suppressor gene [34]. Alterations of Smad4 gene were reported in pancreatic, colorectal, gastric, esophageal, and breast tumors; its loss is associated with tumorigenesis and progression [35-39]. However, the role of Smad4 in LAC is unclear. NSCLC reportedly features low Smad4 expression, which is closely correlated with lymph node metastasis but not with histological type or differentiation [40]. Our study found the loss of Smad4 was key to LAC occurrence and development; our IHC results showed a 62.5% loss rate for Smad4 in patients with LAC. Negative Smad4 labeling was associated with tumor size, lymph node metastasis, differentiation, and pathological stage, and patients with Smad4 negative specimens had worse OS. Thus, reduced Smad4 expression in LAC may predict poor prognosis.

We also found that patients with more protein alterations had worse OS. Possibly, accumulated protein alterations greatly influence LAC development; this would also indicate that combinations of protein alterations are more accurate predictors for patient outcome than single alterations.

We used Spearman correlation analysis to investigate the relationship among smad4, P53Mut, and P16. Although expressions of Smad4 and P53Mut were inversely correlated, Smad4 expression was positively correlated with P16 expression. A previous study revealed that in SMMC-7221 hepatocellular carcinoma cells, TGF-β inhibited proliferation by upregulating P16 expression and increased apoptosis by activating caspase 3 in a Smad4-dependent manner [41]. Another study showed that low Smad4 expression is related to the high p53 expression in breast tumors [42]. As these results are similar to ours, we speculated that LAC could have a similar mechanism. In another study with results that accorded with ours, knocked-down P53 (using siRNA) reportedly increased Smad4 activity and promoted apoptosis in MCF-7 breast cancer cells [39]. Montserrat et al. found that P16 was a commonly inactivated tumor-suppressor gene in NSCLC and that P16 alterations and P53 mutations were frequently found in the same tumor [30]. However, in this paper, we found no correlation between P16 expression and TP53 expression.

Conclusions

In conclusion, alterations of the P53, P16, and Smad4 proteins were strongly associated with LAC malignancy of LAC. Their IHC assessment at the time of diagnosis may provide a new prognostic method, assisting in deciding optimal treatment strategies for patients with LAC.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81372321),China; Jiangsu Provincial Special Program of Medical Science (No. BL2012030), China.

Abbreviations

- IHC

immunohistochemical

- LAC

lung adenocarcinoma

- NSCLC

non-small cell lung cancer

- OS

overall survival

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor β

Footnotes

Chunan Bian and Zhongyou Li contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

CAB did the research planning, IHC operations, statistical analysis, collection of patients’ information, manuscript drafting. ZYL performed the research planning and IHC operations. LX and HBS did the research planning, surgery, and maintenance of patients’ database. JW and YTX performed data sorting and processing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Chunan Bian, Email: 117822663@qq.com.

Zhongyou Li, Email: leeezy999@163.com.

Youtao Xu, Email: 68136939@qq.com.

Jie Wang, Email: 1117821502@qq.com.

Lin Xu, Email: xulin83cn@hotmail.com.

Hongbing Shen, Email: hbshen@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohno M, Okamoto T, Suda K, Shimokawa M, Kitahara H, Shimamatsu S, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of aromatase expression in lung adenocarcinomas with EGFR mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:3613–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakashita S, Sakashita M, Sound Tsao M. Genes and pathology of non-small cell lung carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2014;41:28–39. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raso MG, Behrens C, Herynk MH, Liu S, Prudkin L, Ozburn NC, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors identifies a subset of NSCLCs and correlates with EGFR mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5359–68. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegelin MD, Borczuk AC. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung adenocarcinoma. Lab Invest. 2014;94:129–37. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2013.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scarpa A, Sikora K, Fassan M, Rachiglio AM, Cappellesso R, Antonello D, et al. Molecular typing of lung adenocarcinoma on cytological samples using a multigene next generation sequencing panel. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An SJ, Chen ZH, Su J, Zhang XC, Zhong WZ, Yang JJ, et al. Identification of enriched driver gene alterations in subgroups of non-small cell lung cancer patients based on histology and smoking status. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammerman PS, Sos ML, Ramos AH, Xu C, Dutt A, Zhou W, et al. Mutations in the DDR2 kinase gene identify a novel therapeutic target in squamous cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:78–89. doi: 10.1158/2159-8274.CD-11-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imielinski M, Berger AH, Hammerman PS, Hernandez B, Pugh TJ, Hodis E, et al. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell. 2012;150:1107–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohno T, Otsuka A, Girard L, Sato M, Iwakawa R, Ogiwara H, et al. A catalog of genes homozygously deleted in human lung cancer and the candidacy of PTPRD as a tumor suppressor gene. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:342–52. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipson D, Capelletti M, Yelensky R, Otto G, Parker A, Jarosz M, et al. Identification of new ALK and RET gene fusions from colorectal and lung cancer biopsies. Nat Med. 2012;18:382–4. doi: 10.1038/nm.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oshima M, Okano K, Muraki S, Haba R, Maeba T, Suzuki Y, et al. Immunohistochemically detected expression of 3 major genes (CDKN2A/p16, TP53, and SMAD4/DPC4) strongly predicts survival in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2013;258:336–46. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182827a65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin SH, Kim SC, Hong SM, Kim YH, Song KB, Park KM, et al. Genetic alterations of K-ras, p53, c-erbB-2, and DPC4 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their correlation with patient survival. Pancreas. 2013;42:216–22. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31825b6ab0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yachida S, White CM, Naito Y, Zhong Y, Brosnan JA, Macgregor-Das AM, et al. Clinical significance of the genetic landscape of pancreatic cancer and implications for identification of potential long-term survivors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6339–47. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yachida S, Vakiani E, White CM, Zhong Y, Saunders T, Morgan R, et al. Small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas of the pancreas are genetically similar and distinct from well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:173–84. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182417d36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kandoth C, McLellan MD, Vandin F, Ye K, Niu B, Lu C, et al. Mutational landscape and significance across 12 major cancer types. Nature. 2013;502:333–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oren M, Rotter V. Mutant p53 gain-of-function in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001107. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–75. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciancio N, Galasso MG, Campisi R, Bivona L, Migliore M, Di Maria GU. Prognostic value of p53 and Ki67 expression in fiberoptic bronchial biopsies of patients with non small cell lung cancer. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2012;7:29. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-7-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei B, Liu S, Qi W, Zhao Y, Li Y, Lin N, et al. PBK/TOPK expression in non-small-cell lung cancer: its correlation and prognostic significance with Ki67 and p53 expression. Histopathology. 2013;63:696–703. doi: 10.1111/his.12215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitsudomi T, Hamajima N, Ogawa M, Takahashi T. Prognostic significance of p53 alterations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4055–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steels E, Paesmans M, Berghmans T, Branle F, Lemaitre F, Mascaux C, et al. Role of p53 as a prognostic factor for survival in lung cancer: a systematic review of the literature with a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:705–19. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00062201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahn HK, Jung M, Ha SY, Lee JI, Park I, Kim YS, et al. Clinical significance of Ki-67 and p53 expression in curatively resected non-small cell lung cancer. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:5735–40. doi: 10.1007/s13277-014-1760-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doyle B, Morton JP, Delaney DW, Ridgway RA, Wilkins JA, Sansom OJ. p53 mutation and loss have different effects on tumourigenesis in a novel mouse model of pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma. J Pathol. 2010;222:129–37. doi: 10.1002/path.2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morton JP, Timpson P, Karim SA, Ridgway RA, Athineos D, Doyle B, et al. Mutant p53 drives metastasis and overcomes growth arrest/senescence in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:246–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908428107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson EL, Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Bronson R, Crowley D, Brown M, et al. The differential effects of mutant p53 alleles on advanced murine lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10280–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baldi A, De Luca A, Esposito V, Campioni M, Spugnini EP, Citro G. Tumor suppressors and cell-cycle proteins in lung cancer. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:605042. doi: 10.4061/2011/605042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall M, Bates S, Peters G. Evidence for different modes of action of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors: p15 and p16 bind to kinases, p21 and p27 bind to cyclins. Oncogene. 1995;11:1581–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson JL, Pillai S, Chellappan SP. Genetic and biochemical alterations in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochem Res Int. 2012;2012:940405. doi: 10.1155/2012/940405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanchez-Cespedes M, Reed AL, Buta M, Wu L, Westra WH, Herman JG, et al. Inactivation of the INK4A/ARF locus frequently coexists with TP53 mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 1999;18:5843–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong J, Sun X, Cheng H, Zhao D, Ma J, Zhen Q, et al. Expression of p16 in non-small cell lung cancer and its prognostic significance: a meta-analysis of published literatures. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:155–63. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao W, Huang CC, Otterson GA, Leon ME, Tang Y, Shilo K, et al. Altered p16(INK4) and RB1 expressions are associated with poor prognosis in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Oncol. 2012;2012:957437. doi: 10.1155/2012/957437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jazag A, Ijichi H, Kanai F, Imamura T, Guleng B, Ohta M, et al. Smad4 silencing in pancreatic cancer cell lines using stable RNA interference and gene expression profiles induced by transforming growth factor-beta. Oncogene. 2005;24:662–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–84. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyaki M, Iijima T, Konishi M, Sakai K, Ishii A, Yasuno M, et al. Higher frequency of Smad4 gene mutation in human colorectal cancer with distant metastasis. Oncogene. 1999;18:3098–103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Natsugoe S, Xiangming C, Matsumoto M, Okumura H, Nakashima S, Sakita H, et al. Smad4 and transforming growth factor beta1 expression in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1838–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takaku K, Taketo M. Gastrointestinal tumorigenesis in Smad4 mutant mice. Tanpakushitsu Kakusan Koso. 2001;46:117–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamura G, Sakata K, Nishizuka S, Maesawa C, Suzuki Y, Terashima M, et al. Allelotype of adenoma and differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach. J Pathol. 1996;180:371–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199612)180:4<371::AID-PATH704>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu B, Li W, Qian C, Zhou Z, Xu W, Wu J. Down-regulated P53 by siRNA increases Smad4’s activity in promoting cell apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:1243–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ke Z, Zhang X, Ma L, Wang L. Expression of DPC4/Smad4 in non-small-cell lung carcinoma and its relationship with angiogenesis. Neoplasma. 2008;55:323–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang X, Huang S, Zhang F, Han X, Miao L, Liu Z, et al. Lentiviral-mediated Smad4 RNAi promotes SMMC-7721 cell migration by regulation of MMP-2, VEGF and MAPK signaling. Mol Med Rep. 2010;3:295–9. doi: 10.3892/mmr_00000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lacroix M, Leclercq G. Relevance of breast cancer cell lines as models for breast tumours: an update. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;83:249–89. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000014042.54925.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]