Abstract

To reduce racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes care and outcomes, it is critical to integrate health care and community approaches. However, little work describes how to expand and sustain such partnerships and initiatives. We outline our experience creating and growing an initiative to improve diabetes care and outcomes in the predominantly African American South Side of Chicago. Our project involves patient education and activation, a quality improvement collaborative with six clinics, provider education, and community partnerships. We aligned our project with the needs and goals of community residents and organizations, the mission and strategic plan of our academic medical center, various strengths and resources in Chicago, and the changing health care marketplace. We use the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change conceptual model and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research to elucidate how we expanded and sustained our project within a shifting environment. We recommend taking action to integrate health care with community projects, being inclusive, building partnerships, working with the media, and understanding vital historical, political, and economic contexts.

Keywords: diabetes, disparities, quality of care, race, intervention, equity

Introduction

The causes of diabetes disparities are multifactorial and complex, and thus solutions need to target different drivers (Peek, Cargill, & Huang, 2007). Patients need access to care, health care must be tailored to the individual needs of each patient, and providers have to prescribe the right therapies to get glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol under control (American Diabetes Association, 2014). But diabetes care is largely self-management by patients in their homes and communities (American Association of Diabetes Educators, 2011). Healthy lifestyle is crucial, including good nutrition, physical activity, and actively implementing treatment regimens. Thus, diabetes is a classic model for chronic disease management and presents a prime case study of how to integrate care in the health care system with patients' lives in their homes and communities (Peek, Ferguson, Bergeron, Maltby, & Chin, 2014).

There are new incentives to integrate health care and community approaches to diabetes treatments. Health care policy and market forces are evolving and include population management, global payment systems, new delivery systems, and tax laws requiring nonprofit health care organizations to demonstrate community benefit. For example, as part of the Affordable Care Act, accountable care organizations (ACOs) are responsible for caring for a defined population within a geographic area, reaching budgetary goals to share savings, and meeting performance standards (Fisher & Shortell, 2010). ACOs have incentives to partner with community-based organizations in order to improve chronic care management and prevent costly hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

Background

Although several initiatives have integrated individual health care and community interventions to reduce diabetes disparities (Peek, Ferguson, Bergeron, et al., 2014), few papers discuss how such projects can expand and spread. One comprehensive example is the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health Program's Charleston and Georgetown Diabetes Coalition in South Carolina (Jenkins et al., 2010; Jenkins, Myers, Heidari, Kelechi, & Buckner-Brown, 2011). The coalition educated patients, providers, and community members; implemented quality improvement strategies within health systems; and promoted sustainability with media and social organizing. Community health advisors followed up with patients who missed appointments, linked them to medication assistance and diabetic supplies, and provided grocery store tours and support groups in the community. The Coalition increased healthy food options, developed walking pathways, and advocated for policies that promote good health.

Another example is the translation of the Diabetes Prevention Program from academic medical centers into YMCAs. A modified Diabetes Prevention Program was successfully implemented in YMCAs across 46 communities in 23 states at a lower cost per participant compared to the original intervention. The investigators attributed this successful translation and expansion to collaboration, community-based delivery, health information technology, and payment systems that align incentives (Vojta, Koehler, Longjohn, Lever, & Caputo, 2013).

Given the limited number of prior papers and the evolution toward caring for populations such as with ACOs, there is a great need for more case studies of how initiatives that integrate health care and community approaches to reduce diabetes disparities can expand and spread. The factors and context that lead to successful expansion and sustainability of integrated diabetes disparities reduction efforts are not well known (Peek et al., 2007; Peek, Ferguson, Bergeron, et al., 2014). Therefore, we describe our experience implementing a collaborative effort to reduce diabetes disparities on the South Side of Chicago and how we connected with others to expand and sustain these efforts.

Method

Overview

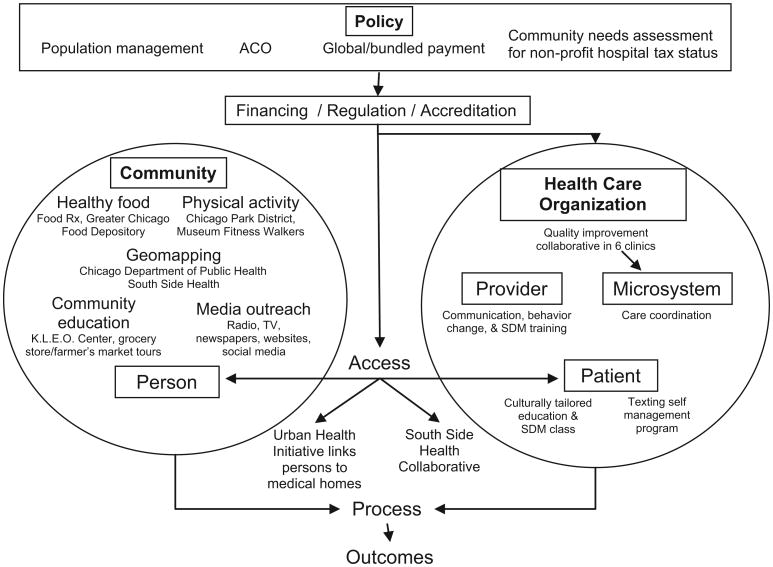

We describe our initiative and then map its components to the six-level conceptual model for reducing disparities of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change Program (Figure 1; Chin & Goldmann, 2011; Chin, Walters, Cook, & Huang, 2007) and the domains of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR; Table 1; (Damschroder et al., 2009). As a validity check, we asked 16 stakeholders to review the article, including leadership at the University of Chicago, providers and staff of participating clinics, and directors of community organizations. The stakeholders confirmed the narrative and suggested minor editorial changes that have largely been incorporated.

Figure 1. Components of the Intervention to Improve Diabetes Care and Outcomes on the South Side of Chicago.

NOTE: ACO = accountable care organization; SDM = shared decision making. Components superimposed on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change conceptual framework for reducing disparities and a model for six levels of intervention: patient, provider, micro system, organization, community, and policy (Chin & Goldmann, 2011; Chin, Walters, Cook, & Huang, 2007)

Table 1. Factors Influencing Implementation, Expansion, and Sustainability of Initiative to Improve Diabetes Care and Outcomes on the South Side of Chicagoa.

| Intervention characteristics | |

| Source |

|

| Relative advantage |

|

| Adaptability |

|

| Complexity |

|

| Costs |

|

| Outer setting | |

| External policy and incentives |

|

| Peer pressure |

|

| Cosmopolitanism |

|

| Patient needs and resources |

|

| Inner setting | |

| Culture |

|

| Implementation climate |

|

| Readiness for implementation |

|

| Individuals | |

| Common goal |

|

| Self-efficacy |

|

| Combined efforts |

|

| Process | |

| Planning |

|

| Engaging |

|

| Reflecting and evaluating |

|

Domains based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (Damschroder et al., 2009)

Results

Demographic and Institutional Context

The Challenge of Diabetes on the South Side of Chicago

The South Side of Chicago bears a high burden of diabetes. For example, residents of predominantly African American neighborhoods in Chicago such as the South Side have 5 times the rate of amputation as people living in primarily White neighborhoods (Feinglass, Abadin, Thompson, & Pearce, 2008). The South Side has many challenges, including food deserts (Illinois Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights, 2011) and neighborhoods where violent crime often deters recreational physical activity (Evenson et al., 2012). The health care system is relatively unintegrated.

Urban Health as a Priority of the University of Chicago

The Dean of the Biological Sciences Division and Michelle Obama, the former Vice President for Community and External Affairs at the University of Chicago Medical Center, created an Urban Health Initiative (UHI) in 2005 whose mission was to improve the health of South Side residents through better integration and collaboration among the University of Chicago and other South Side health resources. The initiative built what is now called the South Side Healthcare Collaborative (SSHC), a network of currently more than 30 health centers, clinics, doctor's offices, and hospitals. The network aimed to improve access to care and target the right level of care for individual patients. For example, the initiative hoped to link patients who visited the emergency department, who did not have a primary care physician to one of the clinics in the SSHC. The strategic initiative aimed to integrate care within the existing financial incentives (Hill & Madara, 2005). For example, Medicaid is the best payor for federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), whereas academic medical centers would receive approximately one fourth the reimbursement if the same patient sought primary care there. Thus, the current public reimbursement system incentivizes Medicaid patients to receive primary care in FQHCs. In 2007, President Robert Zimmer of the University of Chicago announced that urban health and urban education would be the two top community priorities of the University of Chicago (Thompson, 2007).

Diabetes Disparities Research at the University of Chicago

Our investigative team at the University of Chicago had previously engaged in multiple lines of research that provided a broad and deep foundation for subsequent ambitious partnerships. This research includes quality improvement collaboratives with diabetes such as the Health Resources and Services Administration's Health Disparities Collaboratives (Chin, 2010), formative work guiding tailoring of diabetes education and shared decision-making programs for African Americans (Peek et al., 2008; Peek et al., 2009, 2010), and a series of lifestyle modification programs for African Americans (Burnet et al., 2011; McNabb, Quinn, Kerver, Cook, & Karrison, 1997). In addition, team members had extensive experience in community-based participatory research and community collaborations (Choudhry et al., 2011). Team members had also recently completed a systematic review of interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes (Peek et al., 2007). Thus, the team was poised for the right opportunity.

The Funding Opportunity and Match With Institutional Priorities

In 2008, the Merck Foundation released a call for proposals (CFP) for an Alliance to Reduce Diabetes Disparities. The Foundation would fund five sites that would attempt to reduce diabetes disparities by integrative approaches involving patient, provider, system, and community interventions (Clark et al., 2011). The CFP's goals closely matched the interests of the research team and UHI. In addition, although the UHI had begun some research projects, most notably the South Side Health and Vitality Studies (Lindau et al., 2011), it was seeking to support additional projects that combined research, service, and education. Also, several University research centers have community engagement and disparities reduction as priorities, including the Institute for Translational Medicine and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research. These two centers have subcontracts with the ACCESS Community Health Network, a network of FQHCs that would eventually participate in the project. Staff from the UHI helped us identify four clinics from the SSHC that were potentially interested in participating in the project along with two clinics at the University of Chicago. The CFP asked for in-kind support, and the Dean of the Biological Sciences Division supported part of a project manager who would interface with the community as well as UHI staff that would assist the project. In addition, a newly recruited Director of a Center for Community Health and Vitality within the UHI had extensive experience with chronic disease quality improvement collaboratives involving clinics and became a member of our team. The UHI's effort to link patients who did not have regular medical homes to a primary care clinic or provider also fit the project. We were awarded the Merck Foundation grant and later received NIDDK funding.

Implementation of the Initiative

We have previously described the early experiences and outcomes of our project (Peek, Harmon, et al., 2012; Peek, Wilkes, et al., 2012). In brief, we partnered with six clinics and engaged in a quality improvement collaborative with integrative care management (Figure 1). Some patients received culturally tailored diabetes education and instruction in shared decision making. Providers received training in cultural competency, behavioral change, and shared decision making. Community partnerships were initially the least developed component of the project but rapidly expanded in exciting ways. Patients taking the culturally tailored diabetes education classes have improved their A1c (hemoglobin A1c) levels (Peek, Harmon, et al., 2012), clinics have improved their ability to provide chronic illness care (Peek, Wilkes, et al., 2012), and more persons in the community are aware of healthy lifestyles (Peek, Ferguson, Roberson, & Chin, 2014). Ongoing evaluations will assess longitudinal clinical outcomes (e.g., A1c, blood pressure, cholesterol), program costs, and reach into the community.

Expansion of the Initiative

Integration of Health Care and Community

Our community activities have focused on healthy lifestyle (Peek, Ferguson, Roberson, et al., 2014), and we have connected those efforts to our health care interventions (Peek, Wilkes, et al., 2012). Healthy eating is a priority. For example, we have partnered with the K.L.E.O. Community Family Life Center, a community-based organization that runs a monthly food pantry with the Chicago Greater Food Depository. We helped expand the pantry incorporate health education, health screening, and sharing of culturally tailored recipes using food items distributed that day (Peek, Harmon, et al., 2012). Patients in our diabetes education and empowerment classes are encouraged to go to the K.L.E.O. food pantry, and vice versa, community residents at the pantry without a regular doctor are referred to the SSHC to establish primary care. Another example of health care/community integration is the Food Rx program, a collaboration that we developed with Walgreens pharmacy and the 61st Street Farmer's Market to increase access to healthy foods on the South Side of Chicago in food desert areas (Goddu, Roberson, Raffel, Chin, & Peek, in press). Physicians can prescribe “food prescriptions” that recommend specific dietary goals (e.g., low fat, low carbohydrate) and have a redeemable cash value (coupon or voucher) for healthy food at participating Walgreens locations or the farmer's market (Walgreens, 2011).

In addition, our Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research is partnering with the Chicago Department of Public Health on collaborative efforts to improve diabetes outcomes in the city. The Chicago Department of Public Health and our team have developed methods to generate diabetes hospitalization rate estimates at the Chicago neighborhood level from data that are geocoded only at the level of U.S. postal zip code (Jones, Maene, Peek, & Huang, 2013). These results and the ability to map estimates for small areas will help target interventions to reduce diabetes disparities.

Dissemination, Media Outreach, and Social Media

We have used multiple venues to inform people about our project and disseminate lessons learned. Traditional dissemination methods have included academic articles and presentations at national academic meetings, as well as community venues such as local community newspapers, community presentations, and other community-based health events (e.g., Chicago Black Women's Expo). Once we had early successes, the University of Chicago communications team then used many of its internal publications (e.g., magazines, newsletters) and websites to get the word out about our project as a strong example of university–community partnership. Further outreach and word of mouth led to dissemination on local cable television and South Side radio stations. For example, for a modest fee we purchased a time slot for a 13-part diabetes education and viewer call-in show on Chicago CAN-TV, a local cable television station that reaches 1 million viewers. We invited clinicians from our participating clinics and the University of Chicago to give television talks, thus getting them more involved. We connected with a popular local African American television talk show host, Jacinda Lockett, and appeared on her show (http://thejacindashow.com/Home.html). Jacinda subsequently did a feature on one of our events, the Diabetes Cook-Off that highlights community-created healthy recipes. We have appeared numerous times on health interview and call-in shows on WVON, a popular radio station on the South Side. In addition, we created a website (www.southsidediabetes.org) for multiple audiences, including patients, researchers, and new potential partners. Over the past 12 months, our website has had 5,229 visits from 3,100 unique visitors. We also cross-linked the website to our partners (e.g., participating clinics, UHI, Finding Answers, SouthSideHealth. org, and DondeEsta.org) to highlight and celebrate the network we helped build, and created a project logo and brand to enhance the community's awareness of our work. We also shared information about our project on the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research website (www.chicagodiabetesresearch.org). We have used social media, including Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/improvingdiabetes), Twitter (https://twitter.com/SSide_Diabetes), and several blogs. Our project was recently highlighted in the American Diabetes Association's Diabetes Forecast magazine for the lay public (Schugam, 2013).

Sustainability

Becoming Part of Standard Operating Procedure

We have continuously tried to transition the coordination and implementation of successful project components to community members and staff at our participating health centers, with the goal of incorporating these resources into their standard operating procedures. Our clinic sites are assuming increasing administrative responsibility with each round of our patient empowerment classes, and one of our sites is now implementing the class without support from our research team. One way our team has helped clinics incorporate these programs into standard operating procedure is by using quality improvement methods. For example, some clinics have tried adding referral to the patient class via their electronic medical record, and some have attempted to increase class retention by assigning medical assistants to keep in touch with a small group of patients about attendance.

We have collaborated with a certified diabetes educator to lead monthly tours at Save-A-Lot grocery stores on budget-friendly healthy eating, and over the past year we have trained more than 30 community members to lead nutrition-focused educational tours in South Side community settings (i.e., Save-A-Lot, farmer's markets, etc.). We are also creating infrastructure and protocols to support expansion. For example, we are collaborating with an alliance of churches on the South Side to write a guide that will help them set up food pantry and health education events similar to the ones we created at K.L.E.O.

Infusion of New Talent and People

The project attracts many students and volunteers. We have hosted students in nursing, public health, the culinary arts, and medicine, including trainees from college students to research fellows. They hail from diverse institutions, including Chicago State University (which graduates the largest number of minority health students in Illinois), Kennedy-King Community College, Malcolm X Community College, the University of Illinois at Chicago, and medical colleges from around the country. Most of the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine first-year medical students participate in the National Institutes of Health–funded Summer Research Program after their first year of school, and many students have been eager to engage in community projects. The medical school also requires students to complete a longitudinal scholarly project throughout medical school, and community health is represented as one of the five scholarly pathways that students can choose to participate in. Even the legal team at the University of Chicago has been very enthusiastic and helpful, using our project to develop legal templates and approaches for other community research and service collaborations.

Synergy With Other Disparity Programs

Our project shared several staff members with the RWJF Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change National Program Office at the University of Chicago (www.solvingdisparities.org). Finding Answers has a national scope funding evaluations of disparities interventions, performing systematic reviews of the disparities intervention literature, and providing technical assistance to organizations attempting to reduce disparities. This collaboration allowed our local work to be informed by national trends and findings, while also helping the Finding Answers staff understand better the real-world challenges of implementing disparities interventions.

Finding Answers also provided a national venue to disseminate our lessons. For example, our project was one of the case studies in Finding Answers' training webinars for organizations attempting to reduce disparities. During one webinar, a group from Memphis became intrigued with our Food Rx program, and we helped them contact their local Walgreens representative. In the summer-fall of 2012, Finding Answers embarked on a media campaign to disseminate information about its Roadmap to Reduce Disparities (Chin et al., 2012), and the South Side diabetes project was highlighted as one example of integrating health care and community approaches to reduce disparities (Chin, 2012; Devi, 2012). In addition, Finding Answers and members of our diabetes project team collaborated with the American Association of Medical Colleges to provide a workshop on reducing disparities by integrating equity into quality improvement at the national American Association of Medical Colleges Integrating Quality meeting. Finding Answers and our diabetes project have informed each other and created new opportunities for dissemination and shared learning.

Evolving Policy Trends and Financial Incentives

We focused on population management of a defined catchment area based on community needs assessments, scientific evidence, and prior experience. Serendipitously, our integration of health care and community approaches dovetailed with increasing national interest in global payment models and ACOs. An article describing our project's early experiences was accepted into a special diabetes issue of Health Affairs (Peek, Wilkes, et al., 2012), and our project's policy relevance has been one of the themes highlighted in the Merck Alliance's webinars on addressing diabetes disparities (Alliance to Reduce Disparities in Diabetes, 2013). We were invited to speak to the Commonwealth Fund Board of Directors about our project for this reason.

Like many academic medical centers, most of the University of Chicago's financial profit has historically come from providing tertiary and quarternary fee-for-service care and procedures. However, senior medical center leadership changed in 2011. Subsequently the organization's strategic and operating plans have been updated to prepare for an environment that incentivizes optimization of provider delivery models, population health, community benefit, and care coordination and that will include innovative payment models that promote value. In addition, consistent with increasing national efforts in the Affordable Care Act and private sector to reduce racial and socioeconomic disparities in care, the University of Chicago has embarked on an aggressive Diversity and Inclusion initiative to improve equity in quality of care, patient outcomes and experience, and workforce diversity. Our team is actively involved in this local equity initiative.

The goals and content of our South Side Diabetes Project align well with the University of Chicago's new strategic and operating plans. For example, the six clinics in our project became a focal point of a proposal the University of Chicago submitted in response to a request for applications from the state of Illinois Medicaid agency for care coordination programs. The medical director of the participating university Primary Care Group clinic took the lead in writing the proposal, and she helped rally the clinics around this common vision. Medical Center leadership chose diabetes as the focus and used our collaborative team structure as the proposal's core given the experience, relationships, infrastructure, and groundwork that had been built.

Our project also aligned with the increasing national priority on patient-centered care. The University of Chicago Health Plan (UCHP) is a capitated health plan of university and medical center employees and dependents, many of whom live on the South Side. UCHP seeks to improve patient satisfaction and thus adopted a component of our project that used mobile phone texting technology to aid patients with diabetes self-management (Dick et al., 2011; Nundy et al., 2012; Nundy et al., 2014). UCHP assumed the full financial and administrative responsibility of the texting program after seeing the results of a pilot study involving 18 patients (Dick et al., 2011). This buy-in facilitated true integration of the program into clinical operations (e.g., using UCHP staff as care managers), increased scale (i.e., the program was made available to all UCHP members with diabetes), and enhanced sustainability. In addition, the University is aligning the priorities it identifies through its required community needs assessment with its community benefit and service efforts. Obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome are significant health problems on the South Side, and thus our project fits well with the University's vision for community benefit programs. Finally, the University of Chicago maintains the multifactorial mission of patient care, research, education, and community service. Our project works in each of these four areas and provides trainees multiple ways to serve and improve their skills.

Mapping Project to the RWJF Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change Conceptual Model for Reducing Disparities (Figure1) and the CFIR (Table 1)

The Finding Answers Reducing Disparities model highlights that the causes of disparities are multifactorial, and thus the solutions need to address these different areas to be most effective (Chin et al., 2012). Persons with diabetes spend most of their time living in the community. Therefore, we have attempted to increase access to healthy food and safe physical activity and educated the community and engaged in media outreach. Within the health care system, we have implemented culturally tailored diabetes education for patients, behavioral change training for providers, and a quality improvement collaborative for clinics to improve their care management. Policy makers will need to implement payment reform to make preventive medicine, primary care, and public health efforts to reduce disparities financially viable.

Whereas the Finding Answers model provides targets for intervention, the complementary CFIR implementation framework has five domains to help identify and understand key drivers that can expand and spread an intervention (Damschroder et al., 2009): (a) intervention characteristics (e.g., adaptable with cultural tailoring), (b) outer setting (e.g., aligning with policy and financial trends toward population management and accountability to communities), (c) inner setting (e.g., supporting the mission of the Medical Center's UHI), (d) individuals (e.g., providing a venue for enthusiastic trainees eager for community-based service and research), and (e) process (e.g., using principles of community-engaged research and rapid-cycle quality improvement). The table also includes the CFIR subdomains that are most relevant for our project. Successful expansion does not follow a simple linear process. A framework like CFIR helps highlight where a project has strengths for implementation and what gaps need attention.

Discussion

Our project arose from community needs, our prior diabetes disparities reduction efforts, the local institutional environment, and the priorities of the Merck Foundation and NIDDK. Over time the project expanded, particularly in the integration of community partnerships and health care components. We designed our project to integrate health care and community because it was the right thing to do in order to effectively tackle diabetes disparities. However, over time we further aligned our specific interventions with major policy and financial trends in the health care marketplace and the evolving strategic priorities of the University of Chicago. We also explored multiple ways of expanding the project and invested in partnerships when we received positive feedback and found collaborative partners with shared goals and interests. The alignment of interests between community and University of Chicago across research, education, patient care, and community service has enabled us to expand and sustain our integrated diabetes disparities reduction initiative with the hopes of significantly improving the health of the South Side of Chicago.

We have encountered several challenges. The project has required significant investments of time, resources, and staff from our team. For example, team members have spent substantial time establishing and cultivating relationships with community organizations, local businesses, and politicians and participating in university meetings with stakeholders in the medical center and broader university and have expended much effort in overseeing and coordinating volunteers and trainees. We were fortunate to receive grant funding and institutional support from the University and our partners, and some responsibilities for implementing the project have transitioned to the community and health centers. Realistically, however, financial incentives will need to align if integrated health care and community solutions to reduce diabetes disparities are to spread nationally.

Many staff, champions, and leaders have turned over in clinics, and that has required us to rebuild relationships and teams and navigate participants' shifting clinical and personal priorities. Expansion is difficult. Much of our work is successful because of the many personal touch-points we have, but that limits our expansion regarding depth and breadth. We have extended our reach with human capital (e.g., training community members) and technology (e.g., texting patients), but it is a challenge nonetheless.

Conclusions

We have learned many key lessons:

Take action and do something (Clark et al., 2011; Fawcett, Collie-Akers, Schultz, & Cupertino, 2013; Grigg-Saito et al., 2010; McCann, 2009). It is hard to get things going. Aspirational words are common but actual projects rare. People are happy to latch on to a moving train, even if it is slow at first. It may feel difficult to align so many stakeholders and set things up perfectly, but do not let that stop you. Start something, even if on your own. Expansion can build off small successes.

Be inclusive. Be open to different partners and collaborations (Clark et al., 2011; Jenkins et al., 2010; Jenkins et al., 2011; Spencer et al., 2011). We have developed collaborations with local, nonprofit organizations such as the 61st Street Farmer's Market, K.L.E.O. Community Family Life Center, and the Greater Chicago Food Depository, as well as national, for-profit companies such as Walgreens and the Save-a-Lot grocery chain. We have engaged undergraduates and the legal and communications departments. Keep an eye out for unlikely partners you might not have imagined, and actively search for unanticipated opportunities. Interests can align around improving community health.

Include partnerships with established organizations with wide reach (Clark et al., 2011; Grigg-Saito et al., 2010; Jenkins et al., 2010; Jenkins et al., 2011; Rice, Bain, & Collinsworth, 2012; Vojta et al., 2013). For example, our partnership with the RWJF Finding Answers program provided opportunities to disseminate our findings regionally and nationally.

Gain skills in working with media and use local public relations staff (Clark et al., 2011; Jenkins et al., 2010; Jenkins et al., 2011). Researchers usually have no or minimal training in media relations and often want to avoid any perception of self-aggrandizement. However, it is important to get the word out about your project to highlight key health issues and share your lessons. Opportunities often develop from there. Most academic centers have professionally trained public relations staff whose job it is to help researchers craft messages and work with media sources. Scientific journals are primarily read by scientists; expanding the reach of your work to ordinary citizens and policy makers can exponentially increase the real-world impact of your science.

Understand historical, policy, and economic contexts (Clark et al., 2011; Grigg-Saito et al., 2010; Jenkins et al., 2010; Jenkins et al., 2011; Rice et al., 2012). Understanding local and national contexts is critical for recognizing where interests align and what types of tailored programs best fit mutual partners. Participate on community committees, stay in the loop with your organization's strategic planning, and connect with policy makers and advisors.

Do not be afraid to create an action-oriented, integrated health care–community project (Clark et al., 2011; Fawcett et al., 2013; Grigg-Saito et al., 2010; McCann, 2009; Walton, Snead, Collinsworth, & Schmidt, 2012). Integrated projects are ambitious and require significant investment, but people are enthusiastic to support and work with a project that is doing the right thing. Such projects are good for the community, fit the missions of most organizations, and are the types of initiatives that people like to celebrate when an event goes well. These projects speak to the heart as well as mind. The new health care environment provides tremendously exciting opportunities to reduce disparities in care and improve community and population outcomes. Go for it!

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Merck Foundation, NIDDK R18 DK083946-01A1, and Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (P30 DK092949). Dr. Chin was also supported by a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 DK071933).

References

- Alliance to Reduce Disparities in Diabetes. Policy webinars. 2013 http://ardd.sph.umich.edu/policy-webinar.html.

- American Association of Diabetes Educators. Guidelines for the practice of diabetes education. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.diabeteseducator.org/export/sites/aade/_resources/pdf/general/PracticeGuidelines2011.pdf.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:S14–S80. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnet DL, Plaut AJ, Wolf SA, Huo D, Solomon MC, Dekayie G, et al. Chin MH. Reach-out: Pilot study of a family-based diabetes prevention program for African American youth. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2011;103:269–277. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Atlanta, GA: Author; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Chin M. End health-care disparities. Philadelphia Inquirer. 2012 Sep 5;:A2. Retrieved from http://www.philly.com/philly/health/20120905_End_health-care_disparities.html.

- Chin MH. Quality improvement implementation and disparities: The case of the Health Disparities Collaboratives. Medical Care. 2010;48:668–675. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e3585c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, Casey AA, Goddu AP, Keesecker NM, Cook SC. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27:992–1000. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MH, Goldmann D. Meaningful disparities reduction through research and translation programs. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;305:404–405. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin MH, Walters AE, Cook SC, Huang ES. Interventions to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64:7S–28S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhry S, Solomon M, Davis D, Lipton R, Darukhanavala A, Steenes A, Burnet DL, et al. Power-up: A collaborative after-school program to prevent obesity in African American children. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2011;5:363–373. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark NM, Brenner J, Johnson P, Peek M, Spoonhunter H, Walton J, Nelson B, et al. Reducing disparities in diabetes: The alliance model for health care improvements. Diabetes Spectrum. 2011;24:226–230. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi S. Getting to the route of America's racial health inequalities. Lancet. 2012;380:1043–1044. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick J, Nundy S, Solomon M, Bishop K, Chin MH, Peek ME. The feasibility and usability of a text-message-based program for diabetes self-management in an urban African American population. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. 2011;5:1246–1254. doi: 10.1177/193229681100500534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenson KR, Block R, Diez Roux AV, McGinn AP, Wen F, Rodriguez DA. Associations of adult physical activity with perceived safety and police-recorded crime: The Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2012;9:146. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett SB, Collie-Akers V, Schultz JA, Cupertino P. Community-based participatory research within the Latino Health for All coalition. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2013;41:142–154. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2013.788341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinglass J, Abadin S, Thompson J, Pearce WH. A census-based analysis of racial disparities in lower extremity amputation rates in Northern Illinois, 1987-2004. Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2008;47:1001–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher ES, Shortell SM. Accountable care organizations: Accountable for what, to whom, and how. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;304:1715–1716. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddu AP, Roberson TS, Raffel KE, Chin MH, Peek ME. Food Rx: A community-university partnership to prescribe healthy eating on the south side of Chicago. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2014.973251. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigg-Saito D, Toof R, Silka L, Liang S, Sou L, Najarian L, Och S, et al. Long-term development of a “whole community” best practice model to address health disparities in the Cambodian refugee and immigrant community of Lowell, Massachusetts. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:2026–2029. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill LD, Madara JL. Role of the urban academic medical center in US health care. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:2219–2220. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.17.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights. Food deserts in Chicago. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.usccr.gov/pubs/IL-FoodDeserts-2011.pdf.

- Jenkins C, Myers P, Heidari K, Kelechi TJ, Buckner-Brown J. Efforts to decrease diabetes-related amputations in African Americans by the racial and ethnic approaches to community health Charleston and Georgetown diabetes coalition. Family &Community Health. 2011;34(Suppl. 1):S63–S78. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318202bc0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C, Pope C, Magwood G, Vandemark L, Thomas V, Hill K, et al. Zapka J. Expanding the Chronic Care Framework to improve diabetes management: The REACH case study. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2010;4:65–79. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RC, Maene C, Peek M, Huang ES. Use of dasymetric areal interpolation to estimate the burden of diabetes hospitalization in Chicago neighborhoods; Paper presented at The Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists conference; Pasadena, CA. 2013. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- Lindau ST, Whitaker E, Miller D, Johnson W, Robinson C, Chin MH, Wolfe M, et al. Building community-engaged health research and discovery infrastructure on the south side of Chicago: Science in service to community priorities. Preventive Medicine. 2011;52:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann E. Building a community-academic partnership to improve health outcomes in an underserved community. Public Health Nursing. 2009;27:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNabb W, Quinn M, Kerver J, Cook S, Karrison R. The PATHWAYS church-based weigh loss program for urban African American women at risk for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1518–1523. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.10.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nundy S, Dick D, Goddu A, Hogan P, Lu E, Solomon M, Peek ME, et al. Using mobile health to support the chronic care model: Developing an institutional initiative. International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/871925. Article ID 871925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nundy S, Hogan P, Dick J, Goddu AP, Solomon MC, Chin MH, Peek ME. Mobile phone diabetes project led to improved glycemic control and net savings for Chicago plan participants. Health Affairs. 2014;33:2265–2272. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Cargill A, Huang ES. Diabetes health disparities: A systematic review of health care interventions. Medical Care Research and Review. 2007;64(5 Suppl):101S–156S. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Ferguson M, Bergeron N, Maltby D, Chin MH. Integrated community-healthcare diabetes interventions to reduce disparities. Current Diabetes Reports. 2014;14:467. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0467-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Ferguson MJ, Roberson TS, Chin MH. Putting theory into practice: A case study of diabetes-related behavioral change interventions in Chicago's south side. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1524839914532292. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Harmon S, Scott S, Eder M, Roberson T, Tang H, Chin MH. Culturally tailoring patient education and communication skills training to empower African-Americans with diabetes. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2012;2:296–308. doi: 10.1007/s13142-012-0125-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Wilson ST, Chin MH. Barriers and facilitators to shared decision-making in African Americans with diabetes. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24:1135–1139. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1047-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Wilson ST, Chin MH. Race and shared decision-making: Perspectives of African Americans with diabetes. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Odoms-Young A, Wilson ST, Chin MH. How is shared decision-making defined among African-Americans with diabetes? Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;72:450–458. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Wilkes AE, Roberson T, Goddu A, Nocon R, Tang H, Chin MH, et al. Early lessons from an initiative on Chicago's South Side to reduce disparities in diabetes care and outcomes. Health Affairs. 2012;31:177–186. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D, Bain TM, Collinsworth A. Effective strategies to improve the management of diabetes: Case illustration from the Diabetes Health and Wellness Institute. Primary Care. 2012;39:363–379. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schugam J. People to know 2013: Marshall Chin, MD, MPH, and Monica Peek, MD, MPH. Diabetes Forecast. 2013 Oct 38; [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MS, Rosland AM, Kieffer E, Sinco BR, Valerio M, Palmisano G, Heisler M, et al. Effectiveness of a community-health worker intervention among African American and Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101:2253–2260. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. Being Robert Zimmer: Sitting down with the UofC president, one year in. Chicago Weekly. 2007 Sep 27; Retrieved from http://chicagoweekly.net/2007/09/27/being-robert-zimmer-sitting-down-with-the-uofc-president-one-year-in/

- Vojta D, Koehler TB, Longjohn M, Lever JA, Caputo NF. A coordinated national model for diabetes prevention: Linking health systems to an evidence-based community program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2013;44(4 Suppl):S301–S306. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walgreens. Walgreens commits to converting or opening at least 1,000 food oasis stores over the next five years. 2013 Jul 20; [Press release] Retrieved from http://news.walgreens.com/article_display.cfm?article_id=5451.

- Walton HW, Snead CA, Collinsworth AW, Schmidt KL. Reducing diabetes disparities through the implementation of a community-health worker-led diabetes self-management education program. Family & Community Health. 2012;25:161–171. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31824651d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]