Abstract

About 50 % or more of heart failure (HF) patients living in the community have preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF), and the proportion is higher among women and the very elderly. A cardinal feature of HFpEF is reduced aerobic capacity, measured objectively as peak exercise pulmonary oxygen uptake (peak VO2), that results in decreased quality of life. Specifically, peak VO2 of HFpEF patients is 30–70 % lower than age-, sex-, and comorbidity-matched control patients without HF. The mechanisms for the reduced peak VO2 are due to cardiovascular and skeletal muscle dysfunction that results in reduced oxygen delivery to and/or utilization by the active muscles. Currently, four randomized controlled exercise intervention trials have been performed in HFpEF patients. These studies have consistently demonstrated that 3–6 months of aerobic training performed alone or in combination with strength training is a safe and effective therapy to increase aerobic capacity and endurance and quality of life in HFpEF patients. Despite these benefits, the physiologic mechanisms underpinning the improvement in peak exercise performance have not been studied; therefore, future studies are required to determine the role of physical training to reverse the impaired cardiovascular and skeletal muscle function in HFpEF patients.

Keywords: Heart failure and preserved ejection fraction, Aerobic capacity, Physical training, Exercise, Pathophysiology, Nonpharmacologic therapy

Introduction

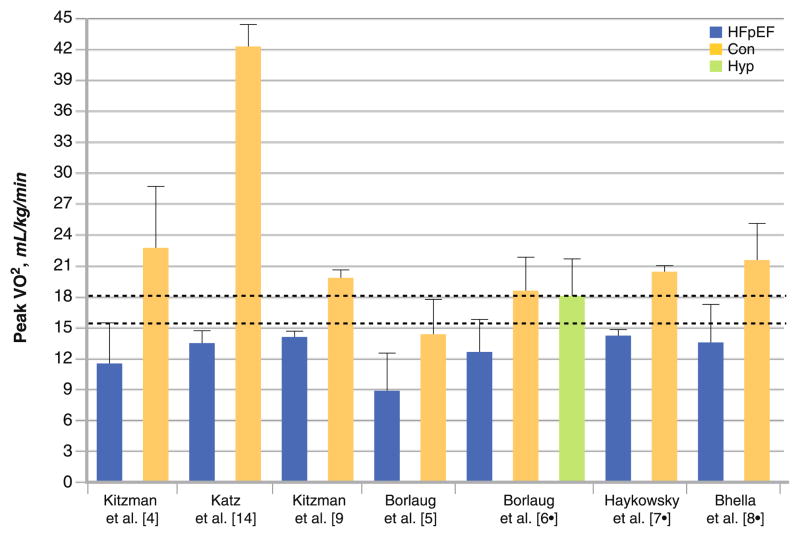

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) occurs in about 50 % or more of heart failure (HF) patients in the community, and the proportion is higher among women and the very elderly [1–3]. A cardinal feature of HFpEF is reduced aerobic capacity, measured objectively as peak exercise pulmonary oxygen uptake (peak VO2) [4, 5, 6•, 7•, 8•, 9], that results in decreased quality of life (Fig. 1) [9]. Although many studies have examined the pathophysiology of exercise intolerance in HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) [10–18], much less is known regarding the underlying determinants of the marked exercise intolerance in HFpEF [19, 20]. This review will provide an overview of the physiologic mechanisms underpinning the reduced aerobic capacity in HFpEF patients and the role of physical training to improve peak VO2 and quality of life (QOL) in this group.

Fig. 1.

Aerobic capacity in heart failure and preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and control patients (Con) matched for age, sex, or comorbidities without heart failure. Peak VO2 peak oxygen uptake; Hyp hypertensive age-matched control patients

Decreased Aerobic Capacity in HFpEF

The paucity of studies performed to date have shown that peak VO2 is 30–70 % lower in HFpEF patients compared to age-, sex-, and comorbidity-matched control patients (Fig. 1) [4, 5, 6•, 7•, 8•, 9, 14]. Of greater concern, aerobic capacity of HFpEF patients is below the threshold range required for full and independent living, and as a result, many of these patients are at increased risk for functional dependence (Fig. 1) [4, 5, 6•, 7•, 8•, 9, 14, 21, 22]. The underlying mechanisms for the reduced aerobic capacity may be due to cardiovascular and skeletal muscle dysfunction and concomitant reduction in oxygen delivery to and/or utilization by the active muscles (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mechanisms responsible for the decreased peak exercise pulmonary oxygen uptake in HFpEF patients

| Kitzman et al. [4] | Katz et al. [14] | Borlaug et al. [5] | Ennezat et al. [23] | Borlaug et al. [6•]

|

Haykowsky et al. [7•] | Bhella et al. [8•] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFpEF vs AC | HFpEF vs AC | HFpEF vs ACC | HFpEF vs HYP | HFpEF vs AC | HFpEF vs HYP | HFpEF vs AC | HFpEF vs AC | |

| VO2 Peak | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ND | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| CO Peak | ↓ | ND | ↓ | ↔ | ||||

| Reserve | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| HR Peak | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| Reserve | ↓ | ↔ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |||

| SV | ND | ND | ND | |||||

| Peak | ↓ | ↔ | ↔ | |||||

| Reserve | ↔ | ↓ | ↔ | |||||

| EDV Peak | ↓ | ND | ↓ | ND | ||||

| Reserve | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | |||

| ESV Peak | ↔ | ND | ND | ↔ | ND | |||

| Reserve | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ||||

| EF Peak | ↔ | ND | ↔ | ND | ||||

| Reserve | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↔ | |||

| SVR Peak | ND | ND | ↔ | ND | ||||

| Reserve | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↔ | |||

| A-VO2 DIFF Peak | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ↓ | ↓ |

| Reserve | ND | ↓ | ||||||

| FVO2C Peak | ND | ↓ | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

HFpEF heart failure and preserved ejection fraction; AC age-matched control; ACC Age-sex and co-morbidity matched controls; HYP hypertensive age-matched controls; VO2 peak pulmonary oxygen uptake; lower in HFpEF vs comparison group; ND no data; CO cardiac output; no difference between HFpEF and comparison group; HR heart rate; SV stroke volume; EDV end-diastolic volume; ESV end-systolic volume; EF ejection fraction; SVR systemic vascular resistance A-VO2DIFF arterial-venous oxygen difference; FVO2C femoral vein oxygen content

To date, seven studies have examined the pathophysiology of peak exercise intolerance in HFpEF [4, 5, 6•, 7•, 8•, 14, 23]. The early study by Kitzman et al. [4], using invasive hemodynamic and radionuclide angiography assessments during incremental cycle exercise, found that the reduced aerobic capacity in HFpEF patients was primarily due to lower cardiac output (CO) and, to a lesser extent, to a lower arterial venous oxygen difference (A-VO2DIFF; Table 1). In turn, the lower CO was secondary to a blunted heart rate (HR) and stroke volume (SV) reserve. The blunted SV was due to an inability to utilize the Frank-Starling mechanism as the 2.6-fold increase in pulmonary capillary wedge pressure from rest to peak exercise occurred without a change in end-diastolic volume (EDV). Although the mechanism for the reduced A-VO2DIFF was not studied, it is likely due, in part, to skeletal muscle hypoperfusion because Katz et al. [14] found that peak exercise femoral venous oxygen content was nearly twofold lower in HFpEF patients compared to age-matched control patients (Table 1). Thus, a consequence of impaired peak and reserve CO is that there is increased capillary transit time and greater oxygen extraction by the active muscles [14].

In a follow-up study from the Kitzman laboratory, Haykowsky et al. [7•] confirmed that the reduced aerobic capacity in HFpEF patients versus healthy control patients was the result of both a decreased peak CO and A-VO2DIFF. Moreover, multivariate analysis revealed that the change from rest to peak exercise in A-VO2DIFF was the strongest independent predictor of peak VO2 [7•]. In contrast to the original Kitzman et al. [4] study, the reduced peak VO2 was not due to a failure of the left ventricle (LV) to dilate as the absolute change in EDV from rest to peak exercise was not significantly different between HFpEF patients and control patients. This discrepancy is due to the different types of patients studied in the two studies. In particular, the original Kitzman et al. [4] study included HF patients (amyloid or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) who have limited use of the Frank-Starling mechanism during exercise [24], while these patients were excluded in the Haykowsky et al. [7•] study.

A series of studies by Borlaug et al. [5, 6•] compared cardiovascular reserve function in HFpEF patients and age-, sex-, and comorbidity-matched control patients. The major finding of both studies was that the decreased peak VO2 in HFpEF patients was due to impaired inotropic, chronotropic, and vasodilator reserve. Similar to Haykowsky et al. [7•], EDV reserve was not different between HFpEF patients and control patients [5, 6•]. In a similar study design, Ennezat et al. [23] found that the reduced CO reserve in HFpEF patients versus hypertensive control patients was secondary to blunted inotropic and vasodilator reserve.

A recent study by Bhella et al. [8•] examined the acute hemodynamic responses during incremental cycle exercise in elderly HFpEF patients versus age-matched healthy control patients. The major finding was that the decreased aerobic capacity in HFpEF patients was solely due to a lower A-VO2DIFF as peak exercise SV, stroke work, CO, and cardiac power output were not significantly different between groups. Further, preliminary analysis (two HFpEF patients and two control patients), using 31Phosphate magnetic resonance spectroscopy during and after performing static leg lifts, revealed impaired skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism in HFpEF patients. Notably, the finding of this study that peak cycle exercise CO is not significantly different between HFpEF patients and age-matched healthy control patients reinforces the finding by Haykowsky et al. [7•] that peripheral ”non-cardiac” factors play a greater role in limiting exercise performance in HFpEF.

In summary, the severe and marked exercise intolerance in HFpEF patients versus age-, sex-, and comorbidity-matched control patients without HF is due to decreased CO and/or A-VO2DIFF that results in a lower oxygen delivery to and/or utilization by the active muscles (Table 1).

Physical Training in Patients with HFpEF

Currently, four randomized controlled exercise intervention trials have assessed the role of physical training on aerobic capacity or aerobic endurance (distance walked in 6 min [6MWD]) and QOL in HFpEF patients [25, 26••, 27••, 28]. In the first published randomized trial, Gary et al. [25] compared the effects of a 12-week combined walking (light to moderate intensity) and HF-management education program versus an HF-management education program alone on aerobic endurance and QOL in 28 older elderly women with HFpEF (Table 2). The investigators reported that the 12-week walking and education program improved aerobic endurance and QOL compared to control patients.

Table 2.

Randomized controlled exercise intervention trials in HFpEF patients

| Study | Group (n) | Age, y | EF,% | Mode | Frequency, d/wk | Intensity | Duration, min | Length of program, wks | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gary et al. [25] | ET (15) CNT (13) |

67 69 |

54 57 |

Walk | 3 | 40 %–60 % | 30 | 12 | ↑ 6MWD, QOL |

| Kitzman et al. [26••] | ET (24) CNT (22) |

70 69 |

61 60 |

Walk/cycle | 3 | 40 %–70 % HRR | 60 | 16 | ↑ peak VO2, ventilation threshold, 6MWD, and physical QOL |

| Edelmann et al. [27••] | ET (44) CNT (20) |

64 65 |

67 66 |

Cycle + RT (UE/LE) | 2–3 2 |

HR 50 %–70 % peak VO2 60 %–65 % 1RM |

20–40 15 REPS |

12 Wks 5–12 |

↑ peak VO2, 6MWD, physical function, ↓ rest LAV, E/e′, and procollagen type I |

| Alves et al. [28] | ET (20) CNT (11) |

63* | 56* | Cycle/treadmill | 3 | 5–7 intervals (3- to 5-min duration) at 70 %–75 % HRmax with 1 min active recovery at 45 %–55 % HRmax | 15–35 | 24 | ↑ peak MET, rest LVEF, E/A ratio, DT |

HFpEF heart failure and preserved ejection fraction; EF ejection fraction; ET exercise training; CNT control; increased; 6MWD distance walked in 6 min; QOL quality of life; HRR heart rate reserve; peak VO2 peak oxygen uptake; RT resistance training; UE upper extremity; LE lower extremity; HR heart rate; 1RM one-repetition maximum; REPS repetitions; decreased; LAV left atrial volume; HRmax maximal heart rate; MET metabolic rate; LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction; E/A early to late mitral inflow velocity; DT deceleration time; E/e′ early transmitral inflow velocity to early diastolic mitral annulus velocity ratio

Mean of whole group

In the first medically supervised, single-center, randomized, controlled, single-blind exercise trial in HFpEF, Kitzman et al. [26••] compared 16 weeks of endurance exercise training with attention control on aerobic capacity and endurance, LV morphology and function, biomarkers, and QOL in 46 elderly patients with HFpEF. The major new finding was that endurance training increased peak VO2, ventilation threshold, 6MWD, and improved physical QOL without altering LV morphology or neuroendocrine function (Table 2). Importantly, the improvement in aerobic capacity was clinically meaningful because baseline peak VO2 in patients randomly assigned to endurance training was below the minimal VO2 value required for full and independent living and was above this value after 16 weeks of endurance training.

Edelmann et al. [27••], in a multicenter trial of exercise training in HFpEF, evaluated the effects of 12 weeks of endurance training with supplemental strength training (initiated in week 5 of the program) with a usual care control on aerobic capacity and endurance, LV systolic and diastolic function, biomarkers, and QOL in 64 HFpEF patients. The authors reported that combined training was associated with a significant increase in peak VO2, aerobic endurance, and self-reported physical dimension of QOL (Table 2). Combined training also significantly decreased resting left atrial volume and early transmitral inflow velocity to early diastolic mitral annulus velocity (E/e′) ratio and procollagen type 1 levels. Finally, the improvement in peak VO2 was inversely related to the change in resting E/e′ ratio and suggests that favorable changes in rest diastolic function may result in increased aerobic capacity [27••].

Lastly, Alves et al. [28] recently reported that 6 months of moderate-intensity aerobic interval training significantly increased estimated metabolic equivalents during peak treadmill exercise and improved resting LV ejection fraction and diastolic function in HFpEF with no change in the usual care control group (Table 2). Despite the small sample size, this study reported improvements in resting LV systolic and diastolic function after physical training in HFpEF (Table 2) [28].

In summary, the few randomized controlled exercise intervention trials performed to date in HFpEF consistently demonstrate that endurance training performed alone or in combination with strength training is a safe and effective intervention to increase aerobic capacity (16 %) and endurance (13 %) and improves QOL (Table 2). Moreover, two recent studies have shown that combined moderate-intensity continuous aerobic and strength training or moderate-intensity interval training can improve resting diastolic function in HFpEF patients.

Safety of Physical Training in HFpEF

The safety of exercise training was reported in the four randomized exercise intervention trials discussed above. Gary et al. [25] reported no adverse events during a 12-week partially supervised (full supervision during the first week followed by weekly supervision) walking program performed in local shopping malls, grocery stores, or gymnasiums. Also, no adverse events occurred with exercise testing or endurance training in the 16-week single-center trial by Kitzman and associates [26••]. Similarly, no serious adverse events occurred in HFpEF patients who participated in the multicenter exercise intervention trial by Edelmann et al. [27••]. Of note, nine (20 %) of the combined aerobic and strength-trained patients reported mild musculoskeletal discomfort during exercise. Finally, Alves et al. [28] reported no adverse events during exercise testing or moderate-intensity aerobic interval training in HFpEF patients. Taken together, the studies performed to date suggest that well-screened HFpEF patients can safely perform physical training in a partially supervised or supervised setting.

Exercise Prescription Recommendations for HFpEF Patients

A supervised maximal exercise test with monitoring for ischemia should be performed before HFpEF patients beginning a physical training program. The exercise training program for clinically stable HFpEF patients should consist of continuous large muscle mass endurance exercise (ie, walking, treadmill, cycling, combined arm and leg ergometry) performed at an intensity between 40 % and 80 % peak VO2 (40–70 % heart rate reserve or Borg rate of perceived exertion between 10 and 14 out of 20) for 20–60 min per session, 3–5 days per week [29]. The intensity and duration of exercise may need to be lower and gradually progressed (ie, “start low and go slow”) for severely debilitated elderly HFpEF patients. In addition, supplemental strength training should be considered, ranging from 40 % to 60 % of maximal strength for 1 set, 2–3 days per week [29]. The exercise program should be initiated in a supervised setting with direct supervision and monitoring. Depending on individual progress and safety during monitored exercise, patients usually should be able to be transitioned to a home exercise maintenance training program.

Conclusions and Future Considerations

Individuals with HFpEF have severe and marked exercise intolerance that is due, in part, to impaired cardiovascular and skeletal muscle function that results in decreased oxygen delivery or utilization by the active muscles. The few randomized controlled exercise intervention trials performed to date show that physical training (aerobic training alone or combined with strength training) is a safe and effective intervention to increase aerobic capacity and endurance and self-reported QOL in HFpEF patients. The underlying mechanisms for the improvement in aerobic capacity remain unknown; therefore, future studies are required to determine if regular physical training can reverse the impaired cardiovascular and skeletal muscle that occurs in HFpEF patients. Finally, future trials are required to determine if newer training modalities (ie, high-intensity aerobic interval exercise [30] or isolated muscle mass training [31]) are effective forms of training to improve aerobic capacity in HFpEF patients [20].

Acknowledgments

Dr. Mark Haykowsky is the exercise physiology section leader for the Alberta Heart Study funded by Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (Alberta Innovates). This work was also supported in part by NIH Grants R37AG18915 and P30AG21332.

Contributor Information

Mark Haykowsky, Email: mark.haykowsky@ualberta.ca, Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2 G4, Canada.

Peter Brubaker, Department of Health and Exercise Sciences, Wake Forest University, PO Box 7868, Winston-Salem, NC 27109, USA.

Dalane Kitzman, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Kitzman DW, Gardin JM, Gottdiener JS, Arnold A, Boineau R, Aurigemma G, Marino EK, Lyles M, Cushman M, Enright PL. Importance of heart failure with preserved systolic function in patients > or = 65 years of age. CHS Research Group. Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(4):413–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01393-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Evans JC, Reiss CK, Levy D. Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: prevalence and mortality in a population-based cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(7):1948–55. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatia RS, Tu JV, Lee DS, Austin PC, Fang J, Haouzi A, Gong Y, Liu PP. Outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(3):260–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitzman DW, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR, Sheikh KH, Sullivan MJ. Exercise intolerance in patients with heart failure and preserved left ventricular systolic function: failure of the Frank-Starling mechanism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(5):1065–72. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90832-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borlaug BA, Melenovsky V, Russell SD, Kessler K, Pacak K, Becker LC, Kass DA. Impaired chronotropic and vasodilator reserves limit exercise capacity in patients with heart failure and a preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2006;114(20):2138–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Borlaug BA, Olson TP, Lam CS, Flood KS, Lerman A, Johnson BD, Redfield MM. Global cardiovascular reserve dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(11):845–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.077. This study showed that the reduced exercise tolerance in HFpEF patients versus age and sex-matched healthy or hypertensive control patients without heart failure was the result of impaired chronotropic, inotropic, and vascular reserve. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7•.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, John JM, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Kitzman DW. Determinants of Exercise Intolerance in Elderly Heart Failure Patients with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(3):265–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.055. This study found that the reduced peak VO2 in elderly HFpEF patients versus age-matched healthy control patients was the result of a reduced cardiac output and arterial-venous oxygen difference. Further, the strongest independent predictor of peak VO2 was the change in arterial-venous oxygen difference from rest to peak exercise for both HFpEF patients and healthy control patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8•.Bhella PS, Prasad A, Heinicke K, Hastings JL, Arbab-Zadeh A, Adams-Huet B, Pacini EL, Shibata S, Palmer MD, Newcomer BR, et al. Abnormal hemodynamic response to exercise in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Hear Fail. 2011;13:1296–304. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr133. This study demonstrated that the reduced peak VO2 in elderly HFpEF patients versus age-matched sedentary control patients was due to a lower peak arterial-venous oxygen difference as peak cardiac output was not significantly different between groups. In addition, preliminary analysis also revealed impaired skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism in HFpEF patients. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitzman DW, Little WC, Brubaker PH, Anderson RT, Hundley WG, Marburger CT, Brosnihan B, Morgan TM, Stewart KP. Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison to systolic heart failure. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2144–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson JR, Mancini DM, Dunkman WB. Exertional fatigue due to skeletal muscle dysfunction in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1993;87(2):470–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.2.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esposito F, Mathieu-Costello O, Shabetai R, Wagner PD, Richardson RS. Limited maximal exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure: partitioning the contributors. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55 (18):1945–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan MJ, Knight JD, Higginbotham MB, Cobb FR. Relation between central and peripheral hemodynamics during exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. Muscle blood flow is reduced with maintenance of arterial perfusion pressure. Circulation. 1989;80(4):769–81. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.4.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mancini DM, Walter G, Reichek N, Lenkinski R, McCully KK, Mullen JL, Wilson JR. Contribution of skeletal muscle atrophy to exercise intolerance and altered muscle metabolism in heart failure. Circulation. 1992;85(4):1364–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.4.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz SD, Maskin C, Jondeau G, Cocke T, Berkowitz R, LeJemtel T. Near-maximal fractional oxygen extraction by active skeletal muscle in patients with chronic heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88(6):2138–42. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber KT, Kinasewitz GT, Janicki JS, Fishman AP. Oxygen utilization and ventilation during exercise in patients with chronic cardiac failure. Circulation. 1982;65(6):1213–23. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.65.6.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higginbotham MB, Morris KG, Conn EH, Coleman RE, Cobb FR. Determinants of variable exercise performance among patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51(1):52–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz SD, Zheng H. Peripheral limitations of maximal aerobic capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. J Nucl Cardiol. 2002;9(2):215–25. doi: 10.1067/mnc.2002.123183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poole DC, Hirai DM, Copp SW, Musch TI. Muscle oxygen transport and utilization in heart failure: implications for exercise (In) tolerance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00943.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitzman DW. Understanding results of trials in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: remembering forgotten lessons and enduring principles. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(16):1687–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitzman DW. Exercise training in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: beyond proof-of-concept. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(17):1792–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paterson DH, Cunningham DA, Koval JJ. St Croix CM: aerobic fitness in a population of independently living men and women aged 55–86 years. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(12):1813–20. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199912000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warburton DER, Taylor A, Bredin SSD, Esch BTA, Scott JM, Haykowsky MJ. Central haemodynamics and peripheral muscle function during exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. Appl Physiol Nutr Me. 2007;32(2):318–31. doi: 10.1139/h06-085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ennezat PV, Lefetz Y, Marechaux S, Six-Carpentier M, Deklunder G, Montaigne D, Bauchart JJ, Mounier-Vehier C, Jude B, Neviere R, et al. Left ventricular abnormal response during dynamic exercise in patients with heart failure and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction at rest. J Card Fail. 2008;14(6):475–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lele SS, Thomson HL, Seo H, Belenkie I, McKenna WJ, Frenneaux MP. Exercise capacity in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Role of stroke volume limitation, heart rate, and diastolic filling characteristics. Circulation. 1995;92(10):2886–94. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gary R. Exercise self-efficacy in older women with diastolic heart failure: results of a walking program and education intervention. J Gerontol Nurs. 2006;32(7):31–9. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20060701-05. quiz 40–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26••.Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Little WC. Exercise training in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3(6):659–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.958785. This was the first randomized controlled trial to compare the effects of 16 weeks of supervised endurance exercise training versus attention control on aerobic capacity and endurance, left ventricular morphology, neurohormones, and quality of life in 46 elderly HFpEF patients. Endurance exercise training was a safe and effective intervention that resulted in a significant improvement in aerobic capacity and endurance and physical quality of life. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27••.Edelmann F, Gelbrich G, Dungen HD, Frohling S, Wachter R, Stahrenberg R, Binder L, Topper A, Lashki DJ, Schwarz S, et al. Exercise Training Improves Exercise Capacity and Diastolic Function in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction Results of the Ex-DHF (Exercise training in Diastolic Heart Failure) Pilot Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(17):1780–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.054. This was the first multicenter exercise intervention trial to compare the effects of 12 weeks of supervised endurance and strength training versus usual care on aerobic capacity and endurance, diastolic function, bio-markers, and quality of life in 64 HFpEF patients. Combined training for 12 weeks was a safe and effective intervention that resulted in favorable improvements in aerobic capacity and endurance, diastolic function, and physical quality of life. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alves AJ, Ribeiro F, Goldhammer E, Rivlin Y, Rosenschein U, Viana JL, Duarte JA, Sagiv M, Oliveira J. Exercise training improves diastolic function in heart failure patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31823cd16a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piepoli MF, Conraads V, Corra U, Dickstein K, Francis DP, Jaarsma T, McMurray J, Pieske B, Piotrowicz E, Schmid JP, et al. Exercise training in heart failure: from theory to practice. A consensus document of the Heart Failure Association and the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13(4):347–57. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfr017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wisloff U, Stoylen A, Loennechen JP, Bruvold M, Rognmo O, Haram PM, Tjonna AE, Helgerud J, Slordahl SA, Lee SJ, et al. Superior cardiovascular effect of aerobic interval training versus moderate continuous training in heart failure patients: a randomized study. Circulation. 2007;115(24):3086–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Esposito F, Reese V, Shabetai R, Wagner PD, Richardson RS. Isolated quadriceps training increases maximal exercise capacity in chronic heart failure: the role of skeletal muscle convective and diffusive oxygen transport. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58 (13):1353–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]