Summary

Background

Despite the importance of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in China, no nationally representative studies have characterised the clinical profiles, management, and outcomes of this cardiac event during the past decade. We aimed to assess trends in characteristics, treatment, and outcomes for patients with STEMI in China between 2001 and 2011.

Methods

In a retrospective analysis of hospital records, we used a two-stage random sampling design to create a nationally representative sample of patients in China admitted to hospital for STEMI in 3 years (2001, 2006, and 2011). In the first stage, we used a simple random-sampling procedure stratified by economic–geographical region to generate a list of participating hospitals. In the second stage we obtained case data for rates of STEMI, treatments, and baseline characteristics from patients attending each sampled hospital with a systematic sampling approach. We weighted our findings to estimate nationally representative rates and assess changes from 2001 to 2011. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01624883.

Findings

We sampled 175 hospitals (162 participated in the study) and 18 631 acute myocardial infarction admissions, of which 13 815 were STEMI admissions. 12 264 patients were included in analysis of treatments, procedures, and tests, and 11 986 were included in analysis of in-hospital outcomes. Between 2001 and 2011, estimated national rates of hospital admission for STEMI per 100 000 people increased (from 3·5 in 2001, to 7·9 in 2006, to 15·4 in 2011; ptrend<0·0001) and the prevalence of risk factors—including smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidaemia—increased. We noted significant increases in use of aspirin within 24 h (79·7% [95% CI 77·9–81·5] in 2001 vs 91·2% [90·5–91·8] in 2011, ptrend<0·0001) and clopidogrel (1·5% [95% CI 1·0–2·1] in 2001 vs 82·1% [81·1–83·0] in 2011, ptrend<0·0001) in patients without documented contraindications. Despite an increase in the use of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (10·6% [95% CI 8·6–12·6] in 2001 vs 28·1% [26·6–29·7] in 2011, ptrend<0·0001), the proportion of patients who did not receive reperfusion did not significantly change (45·3% [95% CI 42·1–48·5] in 2001 vs 44·8% [43·1–46·5] in 2011, ptrend=0·69). The median length of hospital stay decreased from 12 days (IQR 7–18) in 2001 to 10 days (6–14) in 2011 (ptrend<0·0001). Adjusted in-hospital mortality did not significantly change between 2001 and 2011 (odds ratio 0·82, 95% CI 0·62–1·10, ptrend=0·07).

Interpretation

During the past decade in China, hospital admissions for STEMI have risen; in these patients, comorbidities and the intensity of testing and treatment have increased. Quality of care has improved for some treatments, but important gaps persist and inhospital mortality has not decreased. National efforts are needed to improve the care and outcomes for patients with STEMI in China.

Introduction

As China has grown economically, it has experienced an epidemiological transition, with mortality due to ischaemic heart disease more than doubling during the past two decades to more than 1 million deaths per year.1,2 This trend is expected to accelerate, with the World Bank estimating that the number of individuals with myocardial infarction in China will increase to 23 million by 2030.3 Concurrent with this changing epidemiology, the Chinese medical care system has developed rapidly, implementing policies that have improved access by reducing financial barriers and increasing the numbers of hospitals and physicians.4,5

Despite the importance of acute myocardial infarction in China—particularly ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), which accounts for more than 80% of such events in the country6,7 —no nationally representative studies have defined the clinical profiles, management, and outcomes of patients with this disorder during the past decade. The scarcity of contemporary national estimates and data for changes in burden of disease, quality of care (including use of recommended treatments and inappropriate use of non-evidence-based treatments), and treatment outcomes are important barriers to implementation of interventions to improve care and outcomes. In particular, little information is available about acute myocardial infarction in rural areas, where most of the Chinese population lives.8–10

In the China Patient-centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events Retrospective Study of Acute Myocardial Infarction (China PEACE-Retrospective AMI Study), we aimed to assess trends in STEMI management and outcomes in China during the past decade in a retrospective analysis of hospital records. We selected representative hospitals from 2011 to assess present practices and traced this cohort of hospitals backwards to 2006 and 2001 to describe temporal changes.

Methods

Study design

The design of the China PEACE-Retrospective AMI Study has been described previously.11 Briefly, we used a two-stage random sampling design to create a nationally representative sample of patients in China admitted to hospital for acute myocardial infarction in 3 years (2001, 2006, and 2011). In the first stage, we assessed all non-military hospitals in China and excluded prison hospitals, specialised hospitals without a division for cardiovascular disease, and hospitals for traditional Chinese medicine. We stratified the remaining hospitals into five economic–geographical regions (eastern rural, central rural, western rural, eastern urban, and central-western urban). We used these groups because hospital volumes and clinical capacities differ between urban and rural areas and the three official economic–geographical regions (eastern, central, and western) of mainland China. We grouped the central and western urban regions together because incomes and health services capacity per person are much the same. We randomly sampled all highest-level hospitals in urban regions and all central hospitals in rural regions, and excluded hospitals that did not admit patients with acute myocardial infarction or that declined to participate, to give the sample of participating hospitals.

In the second stage, we used systematic random sampling procedures to select for patients with acute myocardial infarction from the local hospital database of each sampled hospital in each study year. Patients with acute myocardial infarction were identified according to International Classification of Diseases—Clinical Modification codes, including versions 9 (410.xx) and 10 (I21.xx) when available, or through principal diagnosis terms noted at discharge. We collected data by central abstraction of medical charts with use of standardised data definitions. We used rigorous monitoring at each stage to ensure data quality.11 Data abstraction quality was monitored by random auditing of 5% of the medical records, with overall variable accuracy exceeding 98%.

Participants

Only patients with a definite discharge diagnosis of STEMI were included in the study sample. The diagnosis of STEMI was determined by the combination of clinical discharge diagnosis terms and electrocardiogram (ECG) results. If the local diagnosis was not definitive, cardiologists at the coordinating centre reviewed the medical record and ECG to establish diagnosis. We treated left bundle branch block as a STEMI equivalent. The type of acute myocardial infarction was validated by review of ECGs from randomly selected records by a cardiologist not involved in data abstraction (appendix 2). We excluded all patients whose STEMI occurred during the course of the hospital admission.

The central ethics committee at the China National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases approved the China PEACE-Retrospective AMI Study. All collaborating hospitals accepted the central ethics approval except for five hospitals, which obtained local approval by internal ethics committees.

Procedures

We abstracted data for the following patient characteristics: age, sex, cardiovascular risk factors, medical history, and clinical characteristics at admission. Information about the medical record abstraction has been described in detail previously.11 Briefly, comorbidities (including hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidaemia) were defined as documented history in the admission notes, discharge diagnosis, or positive laboratory test results (total cholesterol >5·18 mmol/L or LDL ≥3·37 mmol/L, or HDL <1·04 mmol/L in men or <1·30 mmol/L in women).

We assessed clinical severity at admission from information collected at admission about systolic blood pressure, heart rate, estimated glomerular filtration rate, cardiac arrest, and cardiogenic shock. We also used the mini-Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (mini-GRACE) risk score—a modified version of the GRACE risk score including age, systolic blood pressure, ST-segment deviation, cardiac arrest at admission, elevated cardiac enzymes, and heart rate—which has been validated as a means of predicting 6-month mortality for STEMI.12

We assessed use of treatments recommended by the 2010 China National Guideline for STEMI,13 which are consistent with those recommended by guidelines in the USA.14 These treatments included reperfusion therapy, aspirin within 24 h of admission, clopidogrel within 24 h of admission, β blockers within 24 h of admission, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers during hospital admission, and statins during hospital admission. We assessed rates of use only in patients thought to be ideal for treatment, defined (consistent with previously studies) as patients without documented contraindications (appendix 2).15 We also assessed the use of magnesium sulfate (a treatment that is ineffective),16,17 traditional Chinese medicine, other procedures, and tests. We included the seven main categories of traditional Chinese medicine used for coronary heart disease (appendix 2). We did not include some care processes (eg, counselling for smoking cessation) because of inadequate documentation.

We compared patients’ in-hospital outcomes with four measures: death, death or withdrawal from treatment because of terminal status at discharge (referred to as treatment withdrawal), composite complications (including death, treatment withdrawal, reinfarction, cardiogenic shock, ischaemic stroke, or congestive heart failure [defined in appendix 2]), and major bleeding. Treatment withdrawal is common in China because of reluctance by many patients to die in hospital. The Chinese Government uses in-hospital death or treatment withdrawal as a quality measure for hospitals.18,19 Cardiologists in the coordinating study centre adjudicated the clinical status of patients who withdrew from treatment on the basis of medical records. Major bleeding included any intracranial bleeding, absolute haemoglobin decrease of at least 50 g/L, bleeding resulting in hypovolaemic shock, or fatal bleeding (bleeding that resulted directly in death within 7 days). For the main analysis of in-hospital outcomes, we excluded patients who were transferred in from another hospital because we sought to characterise patients admitted directly to the hospital. We also excluded patients who were transferred out, because their admissions were truncated. We further excluded patients who were discharged alive within 24 h because they probably left against medical advice and there was very little time for treatment. For the analysis of treatments, procedures, and tests, we excluded patients who had transferred in from other hospitals, or who had a length of stay of 24 h or shorter.

Statistical analysis

To estimate nationally representative rates for each study year, we applied weights proportional to the inverse sampling fraction of hospitals within each stratum and the sampling fraction of patients within each hospital to account for differences in the sampling fraction for each period in all analyses. We examined patient characteristics, treatments, tests, procedures, and crude rate of outcomes across different study years using the Cochran-Armitage trend test for the trend of binary variables, and the Mann-Kendall trend test for trends of continuous variables. All trend tests were based on three timepoints (2001, 2006, and 2011). We used percentages with 95% CIs to describe categorical variables and medians with IQRs to describe continuous variables. We calculated the rate of hospital admissions due to STEMI in China in each study year by estimating the number of patients admitted to hospital for STEMI and dividing by the total population in the corresponding year; 1·27 billion people lived in China in 2001, 1·31 billion in 2006, and 1·34 billion in 2011. 8–10 We imputed missing age values as the median age of the known set.

We constructed two indicator variables representing years 2006 and 2011, leaving 2001 as the reference. We did logistic regressions including these indicators for time as key explanatory variables, while adjusting for patients’ demographics (age and sex), risk factors or medical history (hypertension, diabetes, current smoker, previous myocardial infarction, previous coronary heart disease, and previous stroke), and clinical characteristics at admission (chest discomfort, cardiac arrest, acute stroke, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and symptom onset to admission time). To account for clustering of patients within hospitals, we established multilevel logistic regression models with use of generalised estimating equations. The dependent variables were in-hospital death, in-hospital death or treatment withdrawal, and in-hospital composite complications, respectively. We transformed continuous variables (eg, age, heart rate, and systolic blood pressure) into categorical variables according to clinically meaning-ful cutoff values (appendix 2). We also tested the linear trend over time in the models. We report odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs from the multilevel logistic regression related to the year indicators.

We did a sensitivity analysis with adjustment according to mini-GRACE risk score. To account for patients without a mini-GRACE risk score because of missing measurement of cardiac enzymes, we used two methods. The first method was to exclude these patients. Our other technique was to use the multiple imputation method to impute the variable (yes or no) for missing elevated cardiac enzymes so that the mini-GRACE risk score could be calculated.20,21 We also did a sensitivity analysis in the entire study sample. In view of the small decrease in length of hospital stay over time, we compared the results with the results with 7-day outcomes instead of the original outcomes.

All comparisons were two-sided, with statistical significance defined as p less than 0·05. All p values are for trend. Statistical analysis was done with SAS software, version 9.2, and R software, version 3.0.2. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT01624883.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author has full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

According to government documents, China had 6623 non-military hospitals in 2011 (figure 1). We excluded 23 prison hospitals, 687 specialised hospitals without divisions for cardiovascular disease, and 1692 hospitals for traditional Chinese medicine. The sampling framework comprised 2010 central hospitals in 2010 rural regions in three rural strata, and 833 highest-level hospitals in 287 urban regions in two urban strata.

Figure 1. Study profile.

AMI=acute myocardial infarction. STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. NSTEMI=non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

We sampled 175 hospitals and invited them to participate in the study. Seven hospitals (two rural and five urban) were excluded because they did not admit patients with acute myocardial infarction and six (four rural, two urban) declined to participate. Examination of patient databases from the 162 remaining hospitals yielded 31 601 hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction (3859 in 2001, 8863 in 2006, and 18 879 in 2011). We sampled 18 631 cases and acquired medical records for 18 110 (97·2%) cases (figure 1). We excluded 4295 cases that did not meet the study criteria to create the study sample of 13 815 patients admitted to hospital for STEMI.

2127 patients were sampled in 2001, 3992 in 2006, and 7696 in 2011. On the basis of these data, we estimate the number of patients admitted to hospital for STEMI in China nationwide to be 45 279 in 2001, 103 743 in 2006, and 207 928 in 2011. Hospital admissions for STEMI per 100 000 people increased during the study period from 3·5 in 2001 to 7·9 in 2006 and 15·4 in 2011 (ptrend <0·0001; figure 2).

Figure 2. Hospital admissions for STEMI in China.

STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Between 2001 and 2011, the age and sex of patients admitted to hospital for STEMI did not change (table 1). Information about age was missing for 18 (0·1%) patients. In 2011, the median age was 65 years (IQR 55–74), and 2247 of 7696 patients (weighted rate 29·5%, 95% CI 28·4–30·5) were women. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease and previous atherosclerotic events increased in prevalence over time (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with STEMI in 2001, 2006, and 2011

| 2001 (n = 2127) | 2006 (n = 3992) | 2011 (n = 7696) | ptrend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Demographic

| ||||

| Age (years) | 65 (56–72) | 66 (55–74) | 65 (55–74) | 0·14 |

| Women | 614 (28·9% [27·0–30·8]) | 1137 (28·7% [27·3–30·1]) | 2247 (29·5% [28·4–30·5]) | 0·47 |

|

| ||||

|

Cardiovascular risk factors

| ||||

| Hypertension | 866 (41·5% [39·4–43·6]) | 1894 (49·3% [47·8–50·9]) | 3890 (51·7% [50·6–52·8]) | <0·0001 |

| Diabetes | 296 (13·9% [12·4–15·4]) | 747 (20·2% [19·0–21·5]) | 1558 (21·2% [20·3–22·1]) | <0·0001 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 908 (42·7% [40·6–44·8]) | 2101 (54·1% [52·6–55·7]) | 4843 (64·6% [63·5–65·6]) | <0·0001 |

| Current smoker | 629 (30·4% [28·5–32·4]) | 1306 (35·1% [33·6–36·5]) | 2854 (39·5% [38·4–40·6]) | <0·0001 |

| Number of risk factors | ||||

| ≥3 | 214 (10·4% [9·1–11·7]) | 658 (18·8% [17·5–20·0]) | 1612 (22·8% [21·9–23·8]) | <0·0001 |

| 2 | 609 (29·1% [27·2–31·0]) | 1308 (33·5% [32·1–35·0]) | 2878 (38·3% [37·2–39·3]) | <0·0001 |

| 1 | 822 (38·5% [36·4–40·5]) | 1390 (33·4% [31·9–34·8]) | 2357 (29·3% [28·3–30·3]) | <0·0001 |

| None | 482 (22·1% [20·3–23·8]) | 636 (14·3% [13·3–15·4]) | 849 (9·7% [9·0–10·3]) | <0·0001 |

|

| ||||

|

Medical history

| ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 218 (10·3% [9·0–11·6]) | 374 (10·0% [9·1–11·0]) | 814 (11·2% [10·5–11·9]) | 0·10 |

| Coronary heart disease | 503 (23·7% [21·9–25·5]) | 790 (20·4% [19·2–21·7]) | 1568 (20·7% [19·8–21·6]) | 0·020 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 14 (0·8% [0·4–1·2]) | 40 (1·2% [0·8–1·5]) | 180 (2·7% [2·3–3·0]) | <0·0001 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 10 (0·6% [0·3–0·9]) | 9 (0·3% [0·2–0·5]) | 21 (0·2% [0·1–0·3]) | 0·012 |

| Stroke | 198 (9·5% [8·3–10·8]) | 421 (11·2% [10·2–12·2]) | 897 (12·1% [11·4–12·9]) | 0·0008 |

|

| ||||

|

Clinical characteristic

| ||||

| Symptom onset to admission (h) | 15 (3–72) | 15 (3–72) | 13 (4–72) | 0·22 |

| Chest discomfort | 1970 (93·1% [92·0–94·2]) | 3680 (92·7% [91·9–93·5]) | 7118 (93·0% [92·4–93·6]) | 0·95 |

| Left bundle branch block | 31 (1·5% [1·0–2·0]) | 74 (1·7% [1·3–2·1]) | 97 (1·1% [0·9–1·4]) | 0·043 |

| Cardiac arrest | 21 (0·9% [0·5–1·3]) | 49 (1·5% [1·1–1·9]) | 125 (1·7% [1·4–2·0]) | 0·0075 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 94 (4·6% [3·7–5·4]) | 245 (5·9% [5·2–6·6]) | 508 (6·2% [5·7–6·7]) | 0·0085 |

| Acute stroke | 18 (0·8% [0·4–1·2]) | 69 (1·7% [1·3–2·1]) | 83 (0·9% [0·7–1·1]) | 0·31 |

| Heart rate (beats per min) | ||||

| <50 | 109 (5·2% [4·2–6·1]) | 221 (5·2% [4·5–5·9]) | 384 (4·9% [4·4–5·4]) | 0·53 |

| 50–110 | 1888 (88·7% [87·3–90·0]) | 3494 (87·9% [86·9–88·9]) | 6917 (90·2% [89·6–90·9]) | 0·0021 |

| >110 | 130 (6·1% [5·1–7·2]) | 277 (6·9% [6·1–7·7]) | 395 (4·9% [4·4–5·4]) | 0·0004 |

| Heart rate (beats per min) | 78 (67–90) | 78 (66–90) | 76 (65–89) | <0·0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | ||||

| <90 | 154 (7·1% [6·0–8·2]) | 264 (6·2% [5·4–6·9]) | 408 (4·7% [4·2–5·2]) | <0·0001 |

| 90–139 | 1281 (60·0% [57·9–62·1]) | 2399 (60·5% [59·0–62·0]) | 4658 (60·8% [59·7–61·9]) | 0·47 |

| ≥140 | 692 (33·0% [31·0–34·9]) | 1329 (33·3% [31·8–34·8]) | 2630 (34·5% [33·4–35·5]) | 0·12 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 125 (109–143) | 125 (110–143) | 128 (110–145) | <0·0001 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min per 1·73 m2)* | ||||

| <30 | 67 (5·3% [4·0–6·5]) | 140 (4·3% [3·6–5·0]) | 232 (3·2% [2·8–3·7]) | <0·0001 |

| 30–59 | 317 (24·6% [22·2–26·9]) | 756 (22·1% [20·6–23·5]) | 1263 (16·8% [15·9–17·7]) | <0·0001 |

| ≥60 | 910 (70·2% [67·7–72·7]) | 2300 (73·7% [72·1–75·2]) | 5583 (80·0% [79·0–80·9]) | <0·0001 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/min per 1·73 m2)* | 72 (56–91) | 75 (58–96) | 86 (66–107) | <0·0001 |

| Troponin concentration (multiple of upper limit of normal)* | 18 (2–89) | 24 (6–106) | 32 (6–202) | <0·0001 |

| Haematocrit (proportion of 1·0)* | 0·39 (0·35–0·43) | 0·39 (0·36–0·43) | 0·40 (0·37–0·44) | <0·0001 |

| Ejection fraction ≤0·40* | 72 (17·6% [14·0–21·2]) | 284 (17·7% [15·7–19·6]) | 568 (12·6% [11·6–13·5]) | <0·0001 |

| Mint-GRACE risk score* | 139 (120–158) | 142 (123–160) | 140 (120–160) | 0·42 |

|

| ||||

|

Transfer status

| ||||

| Transferred in | 37 (1·7% [1·1–2·2]) | 103 (3·1% [2·6–3·7]) | 419 (7·1% [6·5–7·7]) | <0·0001 |

| Transferred out | 144 (6·7% [5·7–7·8]) | 275 (7·0% [6·2–7·8]) | 752 (8·3% [7·7–8·9]) | 0·0028 |

GRACE=Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Data are median (IQR) or n (weighted % [95% CI]), for which n is the number of patients in the study sample and weighted % is a nationally representative rate. STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Among patients with measurements available.

The median time between symptom onset and hospital admission did not change between 2001 and 2011 (table 1). Between 2001 and 2011, patients became less likely to present with hypotension, tachycardia, ejection fraction of 0·40 or less, or low estimated glomerular filtration rate (table 1). The prevalence of cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock increased slightly. The median troponin concentration increased over time. Mini-GRACE scores did not differ across the study period.

After exclusion of 559 patients transferred in from other facilities (37 in 2001, 103 in 2006, and 419 in 2011) and 992 patients whose length of stay was 24 h or shorter (95 in 2001, 263 in 2006, and 634 in 2011), 12 264 patients were included in analysis of trends in treatments, procedures, and tests (table 2, figure 1). The proportion of patients classified as ideal candidates did not change substantially over time for all recommended treatments (appendix 2).

Table 2.

Use of treatments, procedures, and tests among patients with STEMI

| 2001 (n = 1995)

|

2006 (n = 3626)

|

2011 (n = 6643)

|

ptrend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative frequency | Weighted % | Relative frequency | Weighted % | Relative frequency | Weighted % | ||

|

Reperfusion therapies*

| |||||||

| No reperfusion | 425/917 | 45·3% (42·1–48·5) | 786/1689 | 45·5% (43·1–47·9) | 1509/3278 | 44·8% (43·1–46·5) | 0·69 |

| Primary PCI | 74/917 | 10·6% (8·6–12·6) | 218/1689 | 17·4% (15·6–19·2) | 691/3278 | 28·1% (26·6–29·7) | <0·0001 |

| Fibrinolytic therapy | 418/917 | 44·1% (40·8–47·3) | 685/1689 | 37·1% (34·8–39·4) | 1078/3278 | 27·0% (25·5–28·6) | <0·0001 |

|

| |||||||

|

Acute drugs

| |||||||

| Aspirin within 24 h* | 1559/1953 | 79·7% (77·9–81·5) | 3089/3545 | 86·8% (85·7–87·9) | 5904/6490 | 91·2% (90·5–91·8) | <0·0001 |

| Clopidogrel within 24 h* | 24/1832 | 1·5% (1·0–2·1) | 1490/3551 | 47·4% (45·7–49·0) | 5069/6498 | 82·1% (81·1–83·0) | <0·0001 |

| β blockers within 24 h* | 422/840 | 51·3% (47·9–54·7) | 1037/1624 | 63·7% (61·4–66·0) | 1846/3106 | 57·3% (55·6–59·0) | 0·58 |

| Statins*† | 573/1995 | 30·2% (28·2–32·2) | 2675/3626 | 75·9% (74·5–77·3) | 6045/6642 | 92·5% (91·9–93·1) | <0·0001 |

| ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers*† | 1177/1932 | 61·7% (59·5–63·8) | 2429/3513 | 70·7% (69·2–72·2) | 4224/6440 | 66·4% (65·2–67·5) | 0·26 |

| Traditional Chinese medicine within 24 h | 903/1995 | 43·6% (41·5–45·8) | 2003/3626 | 49·7% (48·1–51·3) | 4200/6643 | 57·4% (56·2–58·6) | <0·0001 |

| Traditional Chinese medicine† | 1181/1995 | 57·2% (55·0–59·4) | 2420/3626 | 61·9% (60·4–63·5) | 4827/6643 | 68·8% (67·7–69·9) | <0·0001 |

| Magnesium sulfate† | 656/1995 | 33·1% (31·0–35·1) | 719/3626 | 18·6% (17·4–19·9) | 1159/6643 | 16·1% (15·2–17·0) | <0·0001 |

|

| |||||||

|

Procedures†

| |||||||

| Cardiac catheterisation | 209/1995 | 12·7% (11·3–14·2) | 736/3626 | 25·8% (24·3–27·2) | 2204/6643 | 41·9% (40·7–43·1) | <0·0001 |

| PCI (non-primary) | 60/1995 | 3·4% (2·6–4·2) | 368/3626 | 12·3% (11·2–13·4) | 1077/6643 | 20·3% (19·4–21·3) | <0·0001 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 14/1995 | 1·1% (0·6–1·5) | 21/3626 | 0·9% (0·6–1·3) | 30/6643 | 0·6% (0·4–0·8) | 0·019 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 8/1995 | 0·5% (0·2–0·8) | 32/3626 | 1·0% (0·7–1·3) | 137/6643 | 2·5% (2·1–2·9) | <0·0001 |

|

| |||||||

|

Stents†‡

| |||||||

| Drug-eluting stents only | 37/89 | 39·7% (29·6–49·9) | 354/442 | 80·7% (77·1–84·4) | 1306/1329 | 98·6% (98·0–99·3) | <0·0001 |

| Bare-metal stents only | 44/89 | 50·0% (39·6–60·4) | 71/442 | 15·5% (12·1–18·9) | 23/1329 | 1·4% (0·7–2·0) | <0·0001 |

| Both | 8/89 | 10·3% (4·0–16·6) | 17/442 | 3·8% (2·0–5·6) | 0/1329 | 0 | <0·0001 |

|

| |||||||

|

Tests†

| |||||||

| Troponin | 385/1995 | 22·3% (20·5–24·1) | 1560/3626 | 46·9% (45·3–48·5) | 4195/6643 | 68·6% (67·5–69·7) | <0·0001 |

| Cardiac enzymes | 1732/1995 | 87·3% (85·9–88·8) | 3344/3626 | 93·1% (92·3–93·9) | 6443/6643 | 97·2% (96·8–97·6) | <0·0001 |

| Creatinine | 1241/1995 | 63·8% (61·7–65·9) | 2981/3626 | 84·7% (83·5–85·9) | 6253/6643 | 94·9% (94·4–95·5) | <0·0001 |

| Echocardiogram | 572/1995 | 30·1% (28·1–32·1) | 1581/3626 | 47·6% (46·0–49·2) | 4191/6643 | 67·7% (66·6–68·8) | <0·0001 |

PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention. ACE=angiotensin-converting enzyme. STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Data are n/N or weighted % (95% CI), for which n is the number of patients in the study sample and weighted % is a nationally representative rate, unless otherwise stated.

Only among ideal patients for the treatment (ie, patients with no documented contraindications).

During hospital admission.

Among patients who received at least one stent.

Among ideal candidates for reperfusion therapy, the weighted rate of primary percutaneous coronary intervention increased between 2001 and 2011 (from 10·6% to 28·1%, ptrend <0·0001; table 2). Meanwhile, the use of fibrinolytic therapy concurrently decreased, from 44·1% to 27·0% (ptrend <0·0001). Overall, use of reperfusion therapy, β blockers, angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers did not change between 2001 and 2011 (table 2). From 2001 to 2011, the treatment rate for all other recommended therapies increased among ideal patients (table 2). Use of magnesium sulfate decreased (table 2). By contrast, the use of traditional Chinese medicine within 24 h and at any time during hospital admission increased (table 2).

The weighted proportion of patients that underwent cardiac catheterisation, underwent non-primary percutaneous coronary intervention, or received drug-eluting stents also increased between 2001 and 2011 (table 2). The proportion of patients that underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery was very small (14 of 1995 patients in 2001 vs 30 of 6643 patients in 2011). Substantial increases occurred in the use of diagnostic tests, such as troponin measurement and echocardiography.

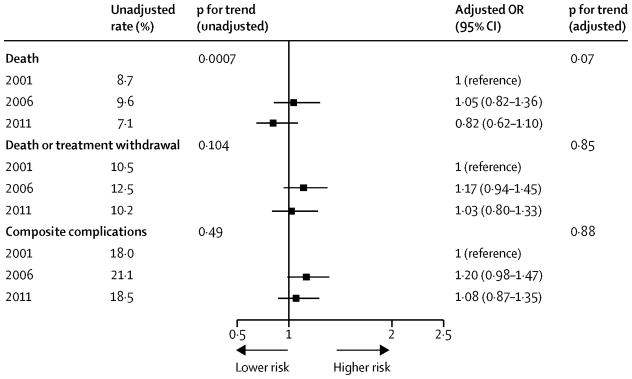

After exclusion of 559 patients transferred in from other facilities, 1148 patients transferred out to other facilities (142 in 2011, 270 in 2006, and 736 in 2011), and 122 patients discharged alive within 24 h (15 in 2001, 38 in 2006, and 69 in 2011), 11 986 patients were included in the analysis of trends in length of hospital stay and in-hospital outcomes (figure 1). The median hospital length of stay was 12 days (IQR 7–18) in 2001, 10 days (6–15) in 2006, and 10 days (6–14) in 2011 (ptrend <0·0001). 165 of 1933 patients died in hospital in 2001 (unadjusted weighted mortality rate 8·4%, 95% CI 7·1–9·8), 351 of 3581 died in 2006 (9·4%, 8·5–10·4), and 496 of 6472 died in 2011 (7·0%, 6·4–7·6). After adjustment for patient demographic and clinical characteristics in the multilevel logistic regression, the risk of in-hospital mortality did not significantly decrease over time (figure 3). Similarly, the adjusted risk of death or treatment withdrawal and complications did not change over time (figure 3). Adjusted outcomes calculated with a 7-day timeframe were much the same as the primary analyses using the entire hospital stay (figure 4). A sensitivity analysis compared the results of the entire cohort with those of the population excluding transferred patient. The results of these two analyses did not differ (appendix 2).

Figure 3. Adjusted in-hospital outcomes for patients with STEMI.

Adjusted odds ratio of 1 shows no difference from year 2001. We included 11 986 patients (1933 in 2001, 3581 in 2006, and 6472 in 2011); 559 patients transferred in from other facilities, 1148 patients transferred out, and 122 patients discharged alive within 24 h were excluded. C=0·76 for mortality, C=0·78 for death or treatment withdrawal, and C=0·68 for composite complications. STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Figure 4. Adjusted 7-day outcomes among patients with STEMI.

Adjusted odds ratio of 1 shows no difference from year 2001. We included 12 421 patients (2010 in 2001, 3696 in 2006, and 6715 in 2011); 559 patients transferred in from other facilities, 713 patients transferred out within 7 days, and 122 patients discharged alive within 24 h were excluded. C=0·76 for mortality and C=0·79 for death or treatment withdrawal. STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

1038 (7·5%) of 13 815 patients (308 in 2001, 373 in 2006, and 357 in 2011) with missing data for cardiac enzymes were excluded from mini-GRACE risk score calculations. The risk of in-hospital death or treatment withdrawal, adjusted by mini-GRACE risk score, was 1·16 (95% CI 0·92–1·47) in 2006 and 0·94 (0·74–1·21) in 2011 (appendix 2). The risk of in-hospital mortality adjusted for mini-GRACE risk score was 1·07 (95% CI 0·80–1·42) in 2006 and 0·77 (0·57–1·03) in 2011. The results of these analyses were much the same as those of imputation for missing data and use of a 7-day timeframe (appendix 2). Six of 1933 patients in 2001 (weighted rate 0·3%, 95% CI 0·1–0·6), 34 of 3581 patients in 2006 (1·1%, 0·7–1·4), and 62 of 6472 patients in 2011 (0·9%, 0·7–1·1) had major bleeding (ptrend =0·08). Only four fatal bleeding events occurred, three in 2006 and one in 2011.

Discussion

In the China PEACE-Retrospective AMI Study we aimed to document changes in the clinical profiles, treatment patterns, quality of care, and in-hospital mortality of patients admitted to hospital for STEMI in China during the past decade. This study, funded by the Chinese Government, was designed to generate the knowledge to support future national initiatives to improve STEMI care and patient outcomes in China.

Our study of a nationally representative sample of patients between 2001 and 2011 characterises the trends in the epidemiology, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI. We identified substantial increases in the estimated national rate of hospital admission for STEMI. Furthermore, we identified a growing burden of prevalent coronary risk factors, persistent delays in admission to hospital, increasing use of procedures and tests, relatively long hospital stays, and gaps in quality of care with the underuse of guideline-recommended therapies and the use of therapies of unknown effectiveness. Concurrent with these trends, outcomes have not improved. To our knowledge, the China PEACE-Retrospective AMI Study is the first large study with rigorous random sampling of a hospital cohort to study national trends in STEMI in China (panel), and identifies important opportunities for quality improvement and policy making.11

Because of the random sampling strategy used to identify hospitals and patients in our study, we believe that the results represent practice in China in general—a large country with great variations across regions and hospitals.23 The experience in China, with the growth in admissions for STEMI, the gaps in treatment, and the growing complexity of patients is similar to previous experience in the USA. This study, like the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project (CCP)24 undertaken 20 years ago in the USA, provides important information about opportunities for improvement. Since the CCP, the USA has invested substantially in quality improvement for cardiovascular disease and has had marked improvements in admission rates, and process of care and outcomes for acute myocardial infarction.25–28

The economic transition in China is resulting in more non-communicable diseases such as STEMI, which has substantial implications for the strategies needed to develop the health-care system. The growing needs for inpatient STEMI care will create pressure for Chinese hospitals to increase capacity, adequately train health-care professionals, develop infrastructure, and improve care. The striking increases in hospital admissions for STEMI noted in our study show that important improvements in capacity have been made; however, national STEMI mortality5 suggests that further growth will be necessary to ensure adequate access for patients with the disorder in China. Furthermore, our study underlines that access to care does not ensure the delivery of the highest-quality care; suggesting that in addition to improvements in capacity, hospitals in China must simultaneously strive to improve care.

The quality of care has improved during the past decade, but substantial gaps still persist. Increases in the use of aspirin, clopidogrel, and statins are encouraging. However, β blockers and angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, which reduce mortality in patients with STEMI, remain very underused. Only half of ideal candidates for reperfusion therapy received treatment, a proportion that did not improve over time. This finding suggests that obstacles persist—eg, difficulty in identification of ideal patients, balancing of the risks and benefits of treatment, and the growing proportion of comorbidities—that render treatment more challenging. Gaps in care might also result from inadequate provider knowledge, structural inadequacies of the systems of care, or concern about potential patient disputes and litigation due to risk of treatment.29–31 Our findings underscore the need for national initiatives to understand the reasons for persistent gaps in care and improve the use of evidence-based care for STEMI in China.32,33

Importantly, our results raise a particular concern that the increased intensity of treatment, procedure use, and testing has not been associated with major decrements in mortality between 2001 and 2011. Moreover, this change occurred in the context of a decrease in length of stay over time. The reported in-hospital mortality in our representative study is consistent with a large trial of 46 000 Chinese patients, but is higher than that reported in two prospective studies with non-randomly selected patients admitted to hospital between 2004 and 2006.6,7,22 By contrast with the improvement achieved in a similar period in the USA and the UK, the lack of change in mortality in China suggests an opportunity for quality improvement.27,34 If the in-hospital mortality of STEMI could be reduced by 1% in China, at least 2100 lives could be saved every year. The number of lives saved would rise rapidly if the number of STEMI increases, as is anticipated. Our data do not show significant improvement in mortality between 2001 and 2011, but we cannot exclude a meaningful effect in view of the point estimates and confidence intervals. Comparison of mini-GRACE-adjusted mortality rates between 2001 and 2011 suggested a borderline-significant reduction in in-hospital mortality, but when treatment withdrawal was included the results were not significant and the point estimate did not suggest a benefit. In China, many patients withdraw from treatment at terminal status, which could be attributed to culture or affordability. Therefore, a focus on in-hospital mortality alone, without accounting for these patients, could result in an underestimate of actual short-term mortality rates. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that a modest benefit occurred based on the confidence intervals.

Several factors could account for why mortality did not improve significantly. First, we noted little improvement in the time from symptom onset to hospital admission, which is much longer than that reported in other national databases.35,36 Second, rates of reperfusion therapies, which were much lower than are those in the USA or Europe, did not improve.28,37 Third, the rate of primary percutaneous coronary intervention was still low in 2011 despite an increase during the past decade.28,37 This rate, in particular, might be able to be increased in some settings but not others. Improvement of these three factors alone could substantially reduce mortality.38 Fourth, we did detect increasing rates of cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock, which is a concern, but they did not account for the lack of substantial improvement in mortality.

We also noted that several therapies that are known to be ineffective, or lack strong evidence, are often given in China. About a sixth of patients received magnesium sulfate, despite a large body of evidence that this therapy is either ineffective or could cause harm.16,17 Traditional Chinese medicine is increasingly used, despite little evidence of its efficacy and safety for treatment of STEMI.39 Further research is needed to elucidate the clinical benefit of traditional Chinese medicine for the management of STEMI.

The findings of this study should be interpreted in view of several limitations. First, the lack of regular biomarker measurement, particularly in 2001, precludes a gold-standard diagnosis of STEMI. Increasing use of biomarker-based diagnosis would likely increase the number of less severe cases in our cohort in 2006 and 2011.13,40,41 This change would be expected to bias towards improvements in outcomes in 2006 and 2011, but we noted no difference. The early years of our cohort might have included more patients without STEMI, but we collected detailed information about clinical condition and no evidence suggested that the risk based on the initial vital signs and clinical condition changed importantly over time. Second, we measured clinical characteristics on the basis of documentation in medical records. Definitions of some disorders and completeness of documentation can differ across hospitals and over time. Third, we could only measure in-hospital outcomes, which might vary from those measured with use of a standardised timeframe (eg, 30 days),42 because we were unable to link patient-level data to a national registry of deaths. Nevertheless, the long length of stay in China permits a fairly long observation period for patients admitted to hospital. Furthermore, analysis with a standardised 7-day timeframe did not provide different results from the primary analysis. Fourth, the use of laboratory tests, including measurement of cardiac biomarkers and creatinine, is inconsistent in China, which might have affected our findings. However, the risk factors that were available for all patients predicted mortality very well and were probably sufficient for comparisons over time.12 Fifth, the study was not powered to detect trends in mortality and our study cannot exclude the possibility of a meaningful improvement in mortality during the study period. However, we detected no strong indication of improvement, especially when we took into account patients who had treatment withdrawn. Finally, we cannot comment on patients with STEMI who were not admitted to hospital during the study period, and we cannot establish whether the increase in the number of patients admitted to hospital with STEMI over time represented increased access to health care or an increasing prevalence of STEMI in the population (or both). Nevertheless, to our knowledge this study is the most comprehensive of patients admitted to hospital with STEMI during the past decade in China.

Our study showed that, among patients admitted to hospital with STEMI, persistent gaps are present between practice and recommended care and outcomes have not significantly improved during the past decade. Although China has launched health-care reform and recently doubled annual expenditures for health care to improve access, challenges exist in optimisation of the use of scarce resources to provide the highest-quality care. Our findings provide evidence for policy makers and health professionals in China and other countries with a rapidly growing burden of STEMI to inform future strategies for medical resource allocation, system improvement, and disease management.

Panel: Research in context.

Systematic review

We searched PubMed for articles published in English and Chinese between Jan 1, 2000, and March 12, 2014, with the terms “ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction”, “acute myocardial infarction”, “acute coronary syndrome”, and “China”. We identified three large nationwide studies, one a clinical trial undertaken in 1999–2005,6 and the other two observational studies. Both observational studies used a convenience sample of hospitals. One studied 2973 patients with acute coronary syndrome from 51 hospitals between 2004 and 2005.7 The other study included 3323 patients with acute coronary syndrome from 65 hospitals in 2006.22

Interpretation

To our knowledge, this study, which included 13815 patients from 162 randomly selected hospitals across China, is the first nationally representative investigation of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). We studied the trends in admissions, the clinical profiles, quality of care, and outcomes of STEMI between 2001 and 2011, a period of epidemiological transition. We noted that hospital admissions for STEMI have become increasingly common, patients are more likely to have comorbidities, and the intensity of testing and treatment has increased. Quality of care has improved for some treatments, but important gaps persist and in-hospital mortality has not significantly improved. Policy makers and health professionals in China have opportunities to improve quality care and outcomes for patients with STEMI and to work to slow the rise in these events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding National Health and Family Planning Commission of China.

We appreciate the multiple contributions made by study teams at the China Oxford Centre for International Health Research and the Yale-New Haven Hospital Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation in the realms of study design and operations, particularly data collection by Yi Pi, Jiamin Liu, Wuhanbilige Hundei, Haibo Zhang, Lihua Zhang, Xue Du, Wenchi Guan, Xin Zheng, and Yuanlin Guo. We appreciate the advice by Xiao Xu, Nihar R Desai, Joseph S Ross, Khurram Nasir, Zhenqiu Lin, Shuxia Li, Haiqun Lin, and Brian Wayda. We appreciate the editing by Sudhakar V Nuti and Sisi Wang. We are grateful for the support provided by the Chinese Government. This project was partly supported by the Research Special Fund for Public Welfare Industry of Health (201202025) from National Health and Family Planning Commission of China. HMK is supported by grant U01 HL105270-03 (Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Contributors

HMK and LJ conceived of the China PEACE-Retrospective AMI Study and take responsibility for all aspects of it. JL, XL, FAM, JAS, HMK, and LJ designed the study. JL, XL, FAM, HMK, and LJ conceived of this Article. JL wrote the first draft of the Article, with further contributions from XL, YW, FAM, JAS, HMK, and LJ. QW and SH did the statistical analysis, with support from XL and YW. All authors interpreted data and approved the final version of the article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yang G, Wang Y, Zeng Y, et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;381:1987–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omran AR. The epidemiologic transition: a theory of the epidemiology of population change. Milbank Q Dec. 1971;49:509–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The World Bank. [accessed Nov 27, 2013];Toward a healthy and harmonious life in China: stemming the rising tide of non-communicable diseases. http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/NCD_report_en.pdf.

- 4.Chen Z. Launch of the health-care reform plan in China. Lancet. 2009;373:1322–24. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60753-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health of People’s Republic of China. China public health statistical yearbook 2012. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College Publishing House; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.COMMIT (ClOpidogrel and Metoprolol in Myocardial Infarction Trial) collaborative group. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45 852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1607–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67660-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao R, Patel A, Gao W, et al. Prospective observational study of acute coronary syndromes in China: practice patterns and outcomes. Heart. 2008;94:554–60. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.119750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. [accessed Dec 9, 2013];China statistical yearbook. 2007 http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2007/indexch.htm. in Chinese.

- 9. [accessed Dec 9, 2013];China Statistical Yearbook. 2012 http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2012/indexch.htm. in Chinese.

- 10. [accessed Dec 9, 2013];Fifth census data by county. 2000 http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/renkoupucha/2000fenxian/fenxian.htm. in Chinese.

- 11.Dharmarajan K, Li J, Li X, Lin Z, Krumholz HM, Jiang L. The China Patient-Centered Evaluative Assessment of Cardiac Events (China PEACE) Retrospective Study of Acute Myocardial Infarction: study design. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6:732–40. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simms AD, Reynolds S, Pieper K, et al. Evaluation of the NICE mini-GRACE risk scores for acute myocardial infarction using the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) 2003–2009: National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research (NICOR) Heart. 2012;99:35–40. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.China Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2010;38:675–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antman EM, Hand M, Armstrong PW, et al. 2007 focused update of the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Group to Review New Evidence and Update the ACC/AHA 2004 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) Circulation. 2008;117:296–329. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krumholz HM, Radford MJ, Wang Y, Chen J, Heiat A, Marciniak TA. National use and effectiveness of β-blockers for the treatment of elderly patients after acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1998;280:623–29. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ISIS-4 (Fourth International Study of Infarct Survival) Collaborative Group. ISIS-4: a randomised factorial trial assessing early oral captopril, oral mononitrate, and intravenous magnesium sulphate in 58 050 patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1995;345:669–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li J, Zhang Q, Zhang M, Egger M. Intravenous magnesium for acute myocardial infarction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD002755. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002755.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. [accessed March 6, 2014];The qualification standard of tertiary general hospital (version 2011) http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/zhuzhan/wsbmgz/201304/b98329ec713a4e8d812b23a56d13f94f.shtml. in Chinese.

- 19.Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic of China. [accessed March 6, 2014];The qualification standard of secondary general hospital (version 2012) http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/yzygj/s3586q/201201/b8dda05b1d23413c94150b5c17b5cc6f.shtml. in Chinese.

- 20.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 21.SAS Institute. [accessed May 5, 2014];The MI procedure. http://support.sas.com/rnd/app/papers/miv802.pdf.

- 22.Liu Q, Zhao D, Liu J, Wang W. Current clinical practice patterns and outcome for acute coronary syndromes in China: results of BRIG project. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2009;37:213–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang S, Meng Q, Chen L, Bekedam H, Evans T, Whitehead M. Tackling the challenges to health equity in China. Lancet. 2008;372:1493–501. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61364-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marciniak TA, Ellerbeck EF, Radford MJ, et al. Improving the quality of care for Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project. JAMA. 1998;279:1351–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masoudi FA, Ponirakis A, Yeh RW, et al. Cardiovascular care facts: a report from the national cardiovascular data registry: 2011. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1931–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, Drye EE, Schreiner GC, Krumholz HM. Recent declines in hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction for Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries: progress and continuing challenges. Circulation. 2010;121:1322–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.862094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Chen J, Drye EE, Spertus JA, Ross JS, et al. Reduction in acute myocardial infarction mortality in the United States: risk-standardized mortality rates from 1995–2006. JAMA. 2009;302:767–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roe MT, Messenger JC, Weintraub WS, et al. Treatments, trends, and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:254–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Du X, Gao R, Turnbull F, et al. Hospital quality improvement initiative for patients with acute coronary syndromes in China: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:217–26. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ranasinghe I, Rong Y, Du X, et al. System barriers to the evidence-based care of acute coronary syndrome patients in China: qualitative analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:209–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Lancet. . Chinese doctors are under threat. Lancet. 2010;376:657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehta RH, Montoye CK, Faul J, et al. Enhancing quality of care for acute myocardial infarction: shifting the focus of improvement from key indicators to process of care and tool use. The American College of Cardiology Acute Myocardial Infarction Guidelines Applied in Practice Project in Michigan: Flint and Saginaw Expansion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2166–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradley EH, Herrin J, Mattera JA, et al. Quality improvement efforts and hospital performance: rates of beta-blocker prescription after acute myocardial infarction. Med Care. 2005;43:282–92. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200503000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gale CP, Cattle B, Woolston A, et al. Resolving inequalities in care? Reduced mortality in the elderly after acute coronary syndromes. The Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project 2003–2010. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:630–39. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibson CM, Pride YB, Frederick PD, et al. Trends in reperfusion strategies, door-to-needle and door-to-balloon times, and in-hospital mortality among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction enrolled in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J. 2008;156:1035–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chung SC, Gedeborg R, Nicholas O, et al. Acute myocardial infarction: a comparison of short-term survival in national outcome registries in Sweden and the UK. Lancet. 2014;383:1305–12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62070-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J, et al. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe: description of the current situation in 30 countries. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:943–57. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gershlick AH, Banning AP, Myat A, Verheugt FW, Gersh BJ. Reperfusion therapy for STEMI: is there still a role for thrombolysis in the era of primary percutaneous coronary intervention? Lancet. 2013;382:624–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu T, Ni J, Wei J. Danshen (Chinese medicinal herb) preparations for acute myocardial infarction (Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16:CD004465. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004465.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2525–38. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.China Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology, Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Circulation. . Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Chin J Circ. 2001;16:407–22. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drye EE, Normand S-LT, Wang Y, et al. Comparison of hospital risk-standardized mortality rates calculated by using in-hospital and 30-day models: an observational study with implications for hospital profiling. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:19–26. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-1-201201030-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.