Abstract

Protein kinase A (PrkA), also known as AMP-activated protein kinase, functions as a serine/threonine protein kinase (STPK), has been shown to be involved in a variety of important biologic processes, including pathogenesis of many important diseases in mammals. However, the biological functions of PrkA are less known in prokaryote cells. Here, we explored the function of PrkA as well as its underlying molecular mechanisms using the model bacterium Bacillus subtilis168. When PrkA is inhibited by 9-β-D-arabinofuranosyladenine (ara-A) in the wild type strain or deleted in the ΔprkA mutant strain, we observed sporulation defects in B. subtilis 168, suggesting that PrkA functions as a sporulation-related protein. Transcriptional analysis using the lacZ reporter gene demonstrated that deletion of prkA significantly reduced the expression of the transcriptional factor σK and its downstream genes. Complementation of sigK gene in prkA knockout mutant partially rescued the phenotype of ΔprkA, further supporting the hypothesis that the decreased σK expression should be one of the reasons for the sporulation defect resulting from prkA disruption. Finally, our data confirmed that Hpr (ScoC) negatively controlled the expression of transcriptional factor σK, and thus PrkA accelerated sporulation and the expression of σK by suppression of Hpr (ScoC). Taken together, our study discovered a novel function of the eukaryotic-like STPK PrkA in spore development as well as its underlying molecular mechanism in B. subtilis.

Keywords: PrkA, serine/threonine protein kinase, sporulation, B. subtilis, the transcription factor σK, transcriptional regulation

Introduction

Protein phosphorylation is the principal mechanism by which extracellular signals are translated into cellular responses. A variety of protein kinases are responsible for the reversible phosphorylation at specific amino acid residues, including serine/threonine protein kinases (STPKs) that phosphorylate serine or threonine of the target proteins. Contrary to the signaling pathways predominantly carried out by STPKs in eukaryotes, two-component systems, consisting of His-kinase sensors and their associated response regulators, are the most common signal transduction system in prokaryotes. Therefore, serine, threonine, and tyrosine kinases had been previously thought to be unique to eukaryotes until phosphorylation at Ser residues was identified in bacteria (Deutscher and Saier, 1988; Reizer et al., 1993). Recent data from genomic sequencing has further illustrated that the eukaryote-like STPKs exist widely in bacteria, suggesting that this well-characterized protein phosphorylation is also distributed in prokaryotes along with two-component systems (Bakal and Davies, 2000). For example, the genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis contains 11 STPKs (Cole et al., 1998; Av-Gay and Everett, 2000). These STPKs are involved in a variety of processes such as development, cell growth, stress responses, primary and secondary metabolism, biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance, and virulence (Cozzone, 2005; Kristich et al., 2007; Wehenkel et al., 2008; Molle and Kremer, 2010; Ohlsen and Donat, 2010).

The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), also called protein kinase A (PrkA), is an important type of STPK. In eukaryotic cells, AMPK is a highly conserved heterotrimeric protein consisting of a catalytic α subunit and regulatory β and γ subunits, and it is regulated by the intracellular ratio of AMP to ATP (Osler and Zierath, 2008). AMPK is activated under conditions of low cellular ATP and high cellular AMP. Therefore, AMPK functions as an energy sensor in cells, and a likely metabolic master switch to coordinate global metabolic response involving cellular uptake of glucose, glycogen synthesis and decomposition, β-oxidation of fatty acids, and mitochondrial biogenesis. At the meantime, AMPK also participates in pathogenesis of important diseases such as ischemic heart, diabetes, cancer, and even viral infection. As a result, it has become a research focus in recent years (Spasic et al., 2009; Kuznetsov et al., 2011).

Comparing to the well-described functions of AMPK in eukaryotic cells, few investigations of AMPK have been reported in prokaryotes. The first gene encoding a prokaryotic PrkA was cloned in Bacillus subtilis. Though the sequence of this PrkA exhibited distant homology to eukaryotic proteins, it phosphorylated a 60-kDa target protein at a Ser residue. However, the biological functions of PrkA remained unclear because no phenotypic change was obtained when the prkA gene was deleted (Fischer et al., 1996). Later, it has been demonstrated that the transcription of prkA was regulated by the spore-specific sigma factor σσE (Eichenberger et al., 2003; Steil et al., 2005). Its role was also involved in spore formation because of its localization of spore coat and the decreased sporulation efficiency in prkA knockout mutant (Eichenberger et al., 2003). However, how PrkA works requires further elucidation. Additionally, another prokaryotic STPK PrkA was identified in a Gram-positive rod-shaped bacterium Listeria monocytogenes (Lima et al., 2011). Analysis of its potential interaction partners through proteomic approaches suggested that the signal transduction pathways mediated by PrkA in L. monocytogenes may affect a variety of fundamental functions, such as protein synthesis, cell wall metabolism, and carbohydrates metabolism (Lima et al., 2011). Since the relatively poor understanding on prokaryotic PrkA, we investigate STPK PrkA in B. subtilis strain 168 and demonstrate its roles in sporulation as well as the underlying molecular mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Media

The strains of B. subtilis and Escherichia coli as well as the plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All B. subtilis strains were derivatives of B. subtilis 168, and those constructed in this work were prepared via transformation with plasmid DNA, confirmed by PCR analysis, and sequenced to ensure that the targeted changes were made. The oligonucleotides primers used for PCR amplification in this study are listed in Table 2>.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype/description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| Bacillus subtilis 168 | Wild type (WT) | From Bacillus Genetic Stock Center |

| PRKA5E | prkA::cat | This work(pPRKA5E, 168) |

| SPOIVBBS | spoIVB (σF)::pDG1728, reporter, control | This work(pSPOIVB, 168) |

| GERDBS | gerD (σG)::pDG1728, reporter, control | This work(pGERD, 168) |

| GEREBS | gerE (σK)::pDG1728, reporter, control | This work(pGERE,168) |

| SPOIVBPRKA5E | spoIVB (σF)::pDG1728, reporter | This work(pSPOIVB, PRKA5E) |

| GERDPRKA5E | gerD (σG)::pDG1728, reporter | This work(pGERD, PRKA5E) |

| GEREPRKA5E | gerE (σK)::pDG1728, reporter | This work(pGERE, PRKA5E) |

| SIGKPRKA5E | spoIVCB and spoIIIC::pDG148 | This work(pSIGKPRKA5E, PRKA5E) |

| PDG148PRK5E | pDG148, control | This work(pDG148, PRKA5E) |

| RSIGKBS | sigK::pDG1728, reporter, control | This work(pRSIGK, 168) |

| RSIGEBS | sigE::pDG1728, reporter, control | This work(pRSIGE, 168) |

| RHPRBS | hpr::pDG1728, reporter, control | This work(pRHPR, 168) |

| RGLNRBS | glnR::pDG1728, reporter, control | This work(pRGLNR, 168) |

| RSIGDBS | sigD::pDG1728, reporter, control | This work(pRSIGD,168) |

| RSIGKPRKA5E | sigK::pDG1728, reporter | This work(pRSIGK, PRKA5E) |

| RSIGEPRKA5E | sigE::pDG1728, reporter | This work(pRSIGE, PRKA5E) |

| RHPRPRKA5E | hpr::pDG1728, reporter | This work(pRHPR, PRKA5E) |

| RGLNRPRKA5E | glnR::pDG1728, reporter | This work(pRGLNR, PRKA5E) |

| RSIGDPRKA5E | sigD::pDG1728, reporter | This work(pRSIGD, PRKA5E) |

| Escherichia coli DH5 |

lacZYA-argF, endA1, recA1, hsdR17, supE44λ-thi-1, gyrA96, rel A1, phoA |

TaKaRa |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMD19-T | Amp | TaKaRa |

| pDG1728 | Bla, emr, spc, spoVG-lacZ, amyE, Pspac | Bacillus Genetic Stock Center |

| pDG148 | kanR, ampR, lacI, ph1R, Ppen, Pspac | Bacillus Genetic Stock Center |

| pPRKA5E | Amp, cat, prkA | This work |

| pSPOIVB | Amp, spc, spoIVB-lacZ | This work |

| pGERD | Amp, spc, gerD-lacZ | This work |

| pGERE | Amp, spc, gerE-lacZ | This work |

| pSIGKPRKA5E | kanR, ampR, sigK | This work |

| pRSIGK | Amp, spc, SigK-lacZ | Synthesized by Shanghai General Co. |

| pRSIGE | Amp, spc, SigE-lacZ | Synthesized by Shanghai General Co. |

| pRHPR | Amp, spc, Hpr-lacZ | Synthesized by Shanghai General Co. |

| pRGLNR | Amp, spc, GlnR-lacZ | Synthesized by Shanghai General Co. |

| pRSIGD | Amp, spc, SigD-lacZ | Synthesized by Shanghai Generaly Co. |

Table 2.

The oligonucleotide primers used in this study.

| Name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Function and Source |

|---|---|---|

| PRKA1F | GACAGCGGGATAGAGGAGA | pPRKA5E |

| PRKA1R | CCAACCCGTTCCATGTGCTCCAAT ACTCCCCGTCAAATCG |

pPRKA5E |

| CATF | CGATTTGACGGGGAGTATTGGAGCAC ATGGAACGGGTTGG |

pPRKA5E |

| CATR | ATATCGTCATATTCCTTGCTTCCGAGGCTCAACGTCAAT | pPRKA5E |

| PRKA2F | ATTGACGTTGAGCCTCGGAAGC AAGGAATATGACGATAT |

pPRKA5E |

| PRKA2R | CCGACATATTTCAGCAGCTC | pPRKA5E |

| SPOIVBF | GAATTCATTTTTTTCGTGCACATCCA | pSPOIVB |

| SPOIVBR | GGATCCTCTCATTTGCGTTGGAATCA | pSPOIVB |

| GERDF | GAATTCATTCATCCCCTCAAAAATCG | pGERD |

| GERDR | GGATCCTAACAAAAAACAGCTCATCA | pGERD |

| GEREF | GAATTCACTAATTATCTTGTAAACGTCAC | pGERE |

| GERER | GGATCCACGGTTTTCTCACTGATAAA | pGERE |

| RTSPOIVBF | CTGGTGAATCTTTAGACTTACTG | Realtime-PCR |

| RTSPOIVBR | GATTCTGTATTTGCCTTCTCCTT | Realtime-PCR |

| RTSPOIVCBF | GATGAACATGCCAGAAACAT | Realtime-PCR |

| RTSPOIVCBR | AAGTCCTCTGCATCCTCAC | Realtime-PCR |

| RTSPOIIICF | GATAGATACGATCCAGCTCAAT | Realtime-PCR |

| RTSPOIIICR | AAACCGCCCGACAATCACTT | Realtime-PCR |

| RTGEREF | GATAAGACAACAAAGGAGATTGC | Realtime-PCR |

| RTGERER | CCTTTCACACCCAATTTCTGCAT | Realtime-PCR |

| RTMMGBF | GCGGACATTGTGATTGAGGC | Realtime-PCR |

| RTMMGBR | ATCGTATGAGGCGGGCAAAT | Realtime-PCR |

| RTSPOIIDF | ACGTACAACAACCAGCCGAT | Realtime-PCR |

| RTSPOIIDR | CCATGGGCTTTTGACGCT | Realtime-PCR |

| RTSPOVBF | TATCGAGTGTGCTGAGGGGA | Realtime-PCR |

| RTSPOVBR | CGAGTGAAATGCGGACAACC | Realtime-PCR |

| SIGK1F | AAGCTTATGGTGACAGGTGTTTTCG | pSIGKPRKA5E |

| SIGK1R | CATTACAAAAAGGGGGGGCATAC TCTTGAAGATAAA |

pSIGKPRKA5E |

| SIGK2F | TTTATCTTCAAGAGTATGCCCCCC CTTTTTGTAATG |

pSIGKPRKA5E |

| SIGK2R | GCATGCTTATTTCCCCTTCGCCTTCTTCCG | pSIGKPRKA5E |

The strains were grown in Luria–Bertani medium, and sporulation was induced in 2x SG medium, a modified Schaeffer’s medium containing beef extract 0.3 g/L, peptone 0.5 g/L, MgSO4.7H2O 0.5 g/L, KCl 2.0 g/L, 10-4 M MnCl2, 10-3 M Ca(NO3)2, 10-6 M FeSO4. 7H2O and 0.1% glucose (Leighton and Doi, 1971). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: chloramphenicol 5 μg/ml, kanamycin 5 μg/ml, and spectinomycin 100 μg/ml.

Genetic Manipulation

The double crossover of homologous recombination method was used to construct ΔprkA mutant (PRKA5E), Δhpr mutant (HPR5E), and ΔprkAΔhpr mutant (PRKA5E HPR5E) of B. subtilis. Two homologous fragments of the prkA gene, chloramphenicol resistant gene were amplified via PCR. The three fragments were linked by overlapping PCR and inserted into a pMD19-T vector to obtain plasmid pPRKA5E. B. subtilis 168 was transformed with plasmid pPRKA5E to generate the ΔprkA mutant strain PRKA5E. For the construction of Δhpr mutant (HPR5E) and ΔprkAΔhpr mutant (PRKA5E HPR5E), two homologous fragments of the hpr gene and erythromycin resistant gene were amplified via PCR, connected by overlap PCR, and inserted into a pEASY-T5 vector to obtain plasmid pHPR5E. The plasmid pHPR5E was finally transformed into B. subtilis 168 and ΔprkA mutant (PRKA5E) to obtain the Δhpr mutant (HPR5E) and ΔprkAΔhpr mutant (PRKA5E HPR5E), respectively.

The encoding gene of the transcriptional factor σK is formed due to a developmental DNA rearrangement of the two separate coding regions (spoIVCB and spoIIIC). To complement the expression of SigK, spoIVCB, and spoIIIC were amplified via PCR, linked together by overlapping PCR. The linked PCR product was digested with HindIII and SphI at primer-incorporated restriction sites, and inserted into a HindIII/SphI -digested pDG148 vector to obtain plasmid pSIGKPRKA5E. The recombinant plasmids pSIGKPRKA5E and the blank vector pDG148 were, respectively, transformed into the ΔprkA mutant strain to obtain the bacterial strain SIGKPRKA5E that complement the expressions of the sigK genes and the corresponding control strain PDG148PRK5E.

Sporulation Assays

The bacterial strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani medium and shaken overnight at 37°C. The overnight cultures were transferred to 2x SG medium to induce sporulation. Spores were assayed at 12 , 24, and 36 h. The spore numbers per milliliter were measured by plating onto LB agar medium after applying a heat treatment (80°C for 15 min). The number of viable cells per milliliter was counted, both before and after the heat treatment, as total CFU on LB plates. Sporulation frequency is determined as the ratio of the number of spores per milliliter to the number of viable cells per milliliter (LeDeaux and Grossman, 1995). Data for each strain is from at least three independent experiments.

For the experiment of PrkA inhibitor, 250 μM 9-β-D-arabinofuranosyladenine (ara-A) from Sigma Co. was added into the 2x SG medium before adding overnight culture.

β-Galactosidase Assays

Plasmid pDG1728 containing the lacZ gene, obtained from the Bacillus Genetic Stock Center (BGSC), was used for constructing reporter vectors for transformation. Segments of the reporter of spoIVB, gerD, and gerE genes were amplified via PCR, digested with EcoRI and BamHI at the corresponding primer-incorporated restriction sites, and inserted into the EcoRI/BamHI-digested pDG1728 vector to obtain plasmids pSPOIVB, pGERD, and pGERE.

To analyze the regulation of gene expression for the transcriptional factor σK, five nested fragments that contained the truncated promoter region of σK were designed to fuse to pDG1728. Those five fragments above were sent to Shanghai Generay Biological Engineering Co. Ltd for synthesis. All the reporter plasmids, including pSIGK, pSIGE, pHPR, pGLINR, and pSIGD, were successfully constructed. Those constructed reporter plasmids were then transformed into wild type (WT) strain B. subtilis 168 and the mutant ΔprkA, respectively.

After the strains harboring lacZ fusions were cultured at 37°C in 2x SG medium to induce sporulation, they were assayed for β-galactosidase activity as previously described (Ferrari et al., 1988). β-galactosidase was assayed using o-nitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside as the substrate and is reported in Miller units. Three repeats were performed at each time point.

Real-Time PCR Assays

The cells of strains B. subtilis 168, PRKA5E, HPR5E, and PRKA5E HPR5E were grown for 12 h at 37°C in 2x SG medium, respectively, and 5 ml cultures were harvested by centrifugation. The total RNA was isolated using RNA extracting kit (Tiangen, China) following the treatment of DNaseI to avoid DNA contaminant. RNAclean Kit (BioTech, China) was then employed to further purify the total RNA. RNA concentration was determined by measuring absorbance at 260 nm using a UV spectrophotometer. After random-primed cDNAs were generated, qPCR analysis was performed with SYBR Green JumpStart Taq Ready Mix for qPCR kit (Sigma–Aldrich Co.) following manufacturer’s instructions. The partial sequence of 16S rRNA was used as an internal control. The PCR amplification used 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, 72°C for 40 s on ABI PRISM 7000 Real-Time PCR.

The real-time PCR experiments were repeated three times for each reaction using independent RNA sample.

Statistical Analysis

All the data were expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons were performed by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s t-test.

Results

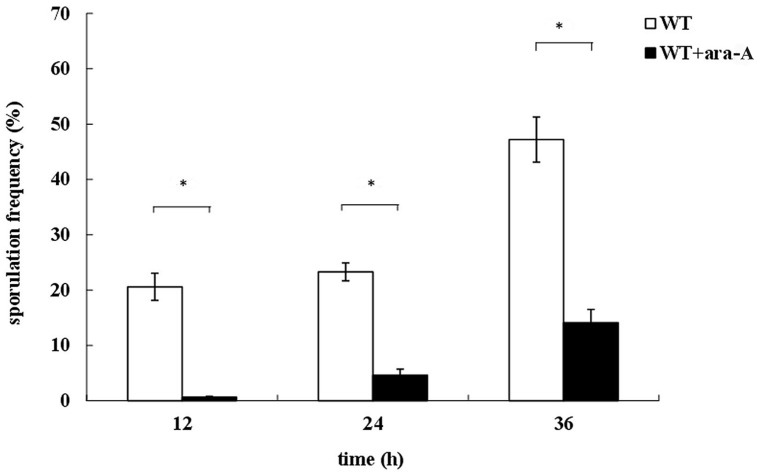

Effect of PrkA Inhibitor ara-A on Sporulation

To determine a possible role of PrkA in B. subtilis, the PrkA inhibitor ara-A was added to decrease the activity of PrkA, and then a series of phenotypes, such as vegetative growth, cell morphology, and sporulation were assayed. Our results showed that the addition of ara-A significantly affected the spore numbers. Specifically, statistical analysis revealed that the sporulation frequencies in the ara-A-treatment groups reduced to 0.65 ± 0.14%, 4.61 ± 1.13%, and 14.1 ± 2.42% at 12, 24, or 36 h, respectively, compared to 20.6 ± 2.45%, 23.3 ± 1.60%, and 47.2 ± 4.09% in the negative controls at the same time points (P < 0.01; Figure 1). Therefore, the significant differences between ara-A-treatment groups and the negative controls suggested that STPK PrkA in B. subtilis might be involved in sporulation. However, no obvious differences were observed in vegetative growth and cell morphology between the cultures treated and not treated with PrkA inhibitor ara-A (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Defects of sporulation with the treatment of PrkA inhibitor ara-A. The strain Bacillus subtilis168 was cultured in 2x SG medium to induce sporulation. Sporulation frequencies of wild type (WT) strain without ara-A or with addition of ara-A were determined at 12, 24, and 36 h, respectively. The white histogram bar represents the WT strain, and the black bar represents ara-A-treatment group. ∗P < 0.01.

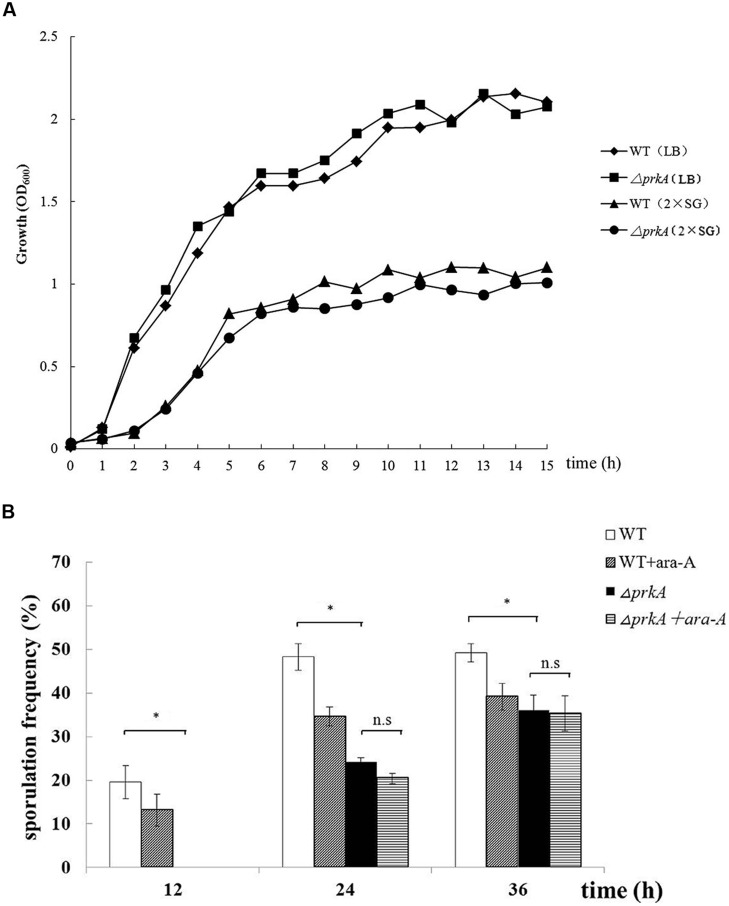

Disruption of Gene prkA Results in Decreased Sporulation

To confirm the roles of PrkA in sporulation, the prkA deletion strain (PRKA5E) was successfully constructed and its phenotypes were determined. The vegetative growth of ΔprkA mutant in either LB medium or 2x SG medium was similar to that of the WT strain (Figure 2A), illustrating that the PrkA protein has no effect on the vegetative growth on B. subtilis. However, the sporulation frequencies in ΔprkA mutant strain decreased significantly with 0%, 24.08 ± 1.16%, and 36.09 ± 3.44%, respectively, at 12, 24 or 36 h; while the WT strain had about 19.63 ± 3.83%, 48.31 ± 3.07%, and 49.26 ± 1.20% of the sporulation frequencies at these time points, respectively, (P < 0.01; Figure 2B). Compared the two sets of data between the ΔprkA mutant and the WT strain, it was also suggested the sporulation was postponed by the deletion of gene prkA since no spores were available in ΔprkA at the time point of 12 h. Moreover, to determined whether the inhibitor ara-A could affect the sporulation through some other pathways besides inhibition of PrkA, we added the ara-A in the ΔprkA mutant strain again. It was found that ara-A had little inhibitory activity in sporulation when the gene prkA was knockout, and the sporulation frequencies in ΔprkA mutant with the treatment of ara-A were 0%, 20.43 ± 2.61%, 35.28 ± 4.04%, respectively, at 12, 24, 36 h (P > 0.05; Figure 2B). Our data from the ΔprkA mutant confirmed the previous report that PrkA is a sporulation-related protein (Eichenberger et al., 2003).

FIGURE 2.

Disruption of the gene prkA decreases sporulation in B. subtilis 168. (A) The vegetative growth rates of ΔprkA mutant and B. subtilis 168 strain in either LB medium or 2x SG medium. ΔprkA mutant (■) and B. subtilis 168 in LB medium (◆); ΔprkA mutant (•) and B. subtilis 168 in 2x SG medium (▲). (B) Sporulation frequencies in WT strain B. subtilis 168, strain with ara-A, ΔprkA mutant strain, and ΔprkA mutant with ara-A. ∗P < 0.01; n.s represented no statistical significance.

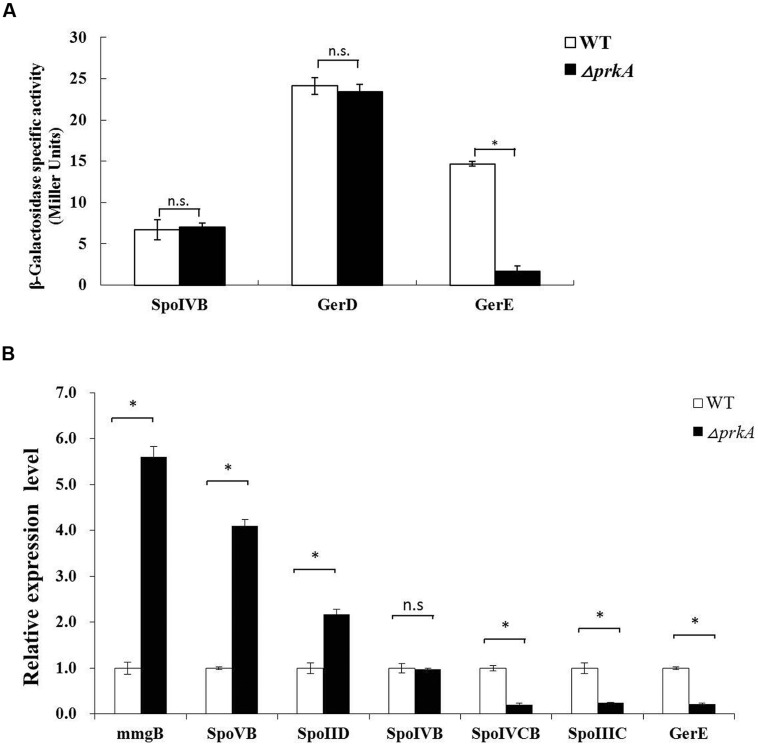

PrkA Regulates the Expression of the Transcriptional Factor σK and its Target Genes

Endospore formation is a very complex multi-stages process, in which many cell type-specific, compartmentalized programs of gene expression are controlled by the cell type-specific activity of RNA polymerase sigma factors (Hilbert and Piggot, 2004). Meanwhile, the promoter region of prkA contains a cis-acting element of the spore specific sigma factor σE and it has also been reported to be transcribed by σE (Eichenberger et al., 2003; Steil et al., 2005). To define the specific stages that PrkA protein was involved during sporulation, three sporulation-related genes that are controlled by three sigma factors of later stages were selected to construct the reporter plasmids to examine transcription by assaying β-galactosidase activities. Those three sporulation-related genes included spoIVB (controlled by σF), gerD (controlled by σG), and gerE (controlled by σK).

The promoter regions of those three genes were cloned and fused to the reporter plasmid pDG1728 to drive the expression of β-galactosidase. Altogether, six strains, including SPOIVBPRKA5E, GERDPRKA5E, GEREPRKA5E as well as the corresponding control strains SPOIVBBS, GERDBS, GEREBS, were successfully constructed by transforming those three recombinant plasmids into the parent strains of ΔprkA and B. subtilis 168, respectively. After analyzing their β-galactosidase activities, we found that the expression level of gene gerE, one of the target genes of the transcriptional factor σK, decreased significantly in the ΔprkA mutant strain compared to that in the corresponding control strains (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3.

PrkA decreases the expression of the transcriptional factor σK and its target genes. (A) Assay to β-galactosidase activity in the reporter gene fusion expression strains. The white histogram bar represents the WT strain, and the black bar represents ΔprkA mutant. (B) Real-time PCR to detect the relative expressional level of the typical sporulation-related genes, including mmgB, spoIID, spoVB, spoIVB, gerD, and gerE. The white histogram bar represents the WT strain B. subtilis 168, and the black bar represents ΔprkA mutant. ∗P < 0.01; n.s represented no statistical significance.

To further verify our experimental results from the assay of β-galactosidase activity, we compared the expressional levels of spoIVB, sigK, and gerE using real time-PCR between B. subtilis 168 and ΔprkA mutant strain. At the same time, we also assayed the transcription of those genes mmgB, spoVB, and spoIID that are known to be under the control of σE. The encoding gene for the sigma factor of σK includes two separate coding regions of spoIVCB and spoIIIC as mentioned above. It was found that the disruption of gene prkA led to decreased expressions of the encoding genes of σK (spoIVCB and spoIIIC). The expressional level of gerE, which is controlled by σK, showed a reduction similar to the result from β-galactosidase assay. In contrast, compared to the WT strain, the transcriptions of mmgB, spoVB, and spoIID were differentially increased in the ΔprkA mutant. The gene spoIVB controlled by σF had the similar mRNA level to WT strain (Figure 3B). Thus our results suggested that PrkA was likely involved in regulating the synthesis of transcriptional factor σK, affected the expression of its downstream target genes, and finally caused the deficient sporulation.

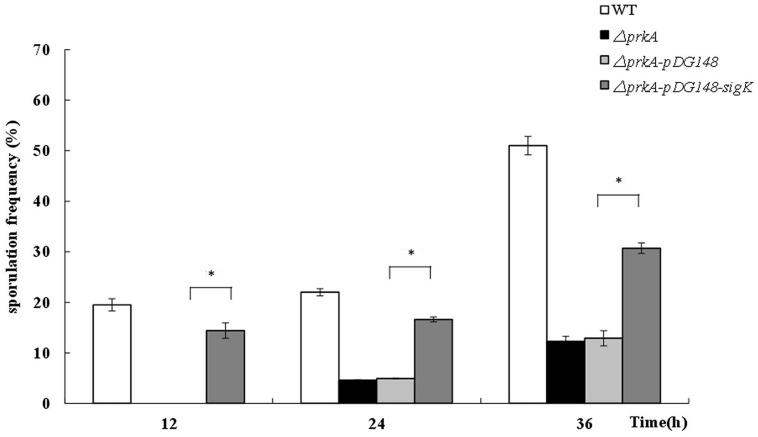

The Complementary Expression of sigK Genes Rescued the Defect of Sporulation in ΔprkA Mutant Strain

Based on the above hypothesis that the decreased sporulation level of ΔprkA mutant strain was caused by the reduced expressions of the transcriptional factor σK, we designed an experiment to elevate the expression of sigK in ΔprkA mutant strain. After the recombinant plasmid pSIGKPRKA5E and the blank vector pDG148 were transformed into ΔprkA mutant, the spore numbers and sporulation frequencies were determined. Compared to the ΔprkA mutant strain, the sporulation of SIGKPRKA5E strain significantly improved to about 60% of sporulation capability in WT B. subtilis 168 (Figure 4). Thus, the data is consistent with the hypothesis that elevated expression of σK-regulated genes could partially improve the sporulation defect in ΔprkA mutant.

FIGURE 4.

The complement of sigK gene in ΔprkA mutant strain partially rescues the effect of sporulation. Sporulation frequencies were detected in WT strain B. subtilis 168, ΔprkA mutant, the blank vector pDG148 in ΔprkA mutant, and the strain with σK complement in ΔprkA mutant. ∗P < 0.01.

PrkA Positively Controls the Transcriptional Factor σK Mediated by the Motif of Hpr (ScoC)

To understand how PrkA positively control the expression of the transcriptional factor σK that is required at the later stage during sporulation, we performed investigation on the regulation of gene expression for the transcriptional factor σK. DBTBS (Database of Transcriptional Regulation in B. subtilis) was firstly employed to identify the potential cis-activating elements within the promoter region of sigK, and four potential transcription factor binding motifs of SigE, Hpr (ScoC), GlnR, and SigD were found at the 5% significance level. Then, a series of reporter fusions containing the truncated sigK promoter regions to lacZ were successfully constructed. Specifically, five nested fragments with a common downstream end and variable upstream ends were fused to promoter-less lacZ gene in pDG1728, respectively (Figure 5A,B). Those constructed plasmids were transformed into the ΔprkA mutant strain and the WT B. subtilis 168. The β-galactosidase activity in each strain was measured.

FIGURE 5.

PrkA changes the expression of sigK via negatively regulating the transcription factor of Hpr (ScoC). (A) The sequence of the sigK promoter regions by 5′ deletions. The rectangle boxes indicate the binding motifs in the promoter of sigK including SigE, Hpr(ScoC), GlnR, and SigD. (B) Mapping of the sigK promoter regions by 5′ deletions. Schematic representation of the different sigK::lacZ fusions used in this study. The filled arrows indicate the primers used for generating the various reporter fusions (P1–P5). The blocks also indicate the binding motifs in the promoter of sigK including SigE, Hpr(ScoC), GlnR, and SigD, whereas the 5′ and 3′ end termini of the motifs are denoted with their nucleotide position relative to the initiator codon. The derivative strains of WT B. subtilis 168 or ΔprkA mutant carry the respective fusions are shown the below. (C) Expression of the series of sigK::lacZ fusions, respectively. Cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C, and β-galactosidase activities were determined at 36 h. The left histograms represent the derivative strains of the WT background; the right histograms represent the derivative strains of the ΔprkA mutant background. ∗P < 0.01; n.s represented no statistical significance.

In the five strains containing the reporter plasmids transformed into the WT B. subtilis 168, we found that strain WT-P2 had an obviously lower β-galactosidase activity than WT-P1 (P < 0.01). Strain WT-P1 contained an additional transcriptional motif of SigE than strain WT-P2. However, WT-P2 had much lower β-galactosidase activity than WT-P3 that missed the cis-activating element of Hpr (ScoC; P < 0.01; Figure 5C). The β-galactosidase activities in WT-P4 and WT-P5 had no statistical differences (P> 0.05). Based on the experimental data, we confirmed that, in WT strain B. subtilis 168, the expression of sigK was under the transcription factor of SigE that had been described previously (Kroos et al., 1989). However, it was firstly shown in our study that the transcription factor Hpr (ScoC) negatively regulated the expression of sigK.

In the analysis of strains with plasmids transformed into ΔprkA mutant, the β-galactosidase activity in prkA-P2 was much lower than in prkA-P1 (P < 0.01), while prkA-P1 was similar to that in the corresponding strain transformed from WT B. subtilis 168. However, no significant difference was observed between prkA-P2 and prkA-P3 (P> 0.05; Figure 5C,B). Since the reporter plasmids prkA-P2 had an additional binding motif of Hpr (ScoC) that potentially controlled sigK expression negatively in the WT strain, the absence of PrkA inhibited Hpr (ScoC) to regulate the expression of sigK anymore, suggesting that PrkA increased the expression of sigK via the transcription factor binding motif of Hpr (ScoC).

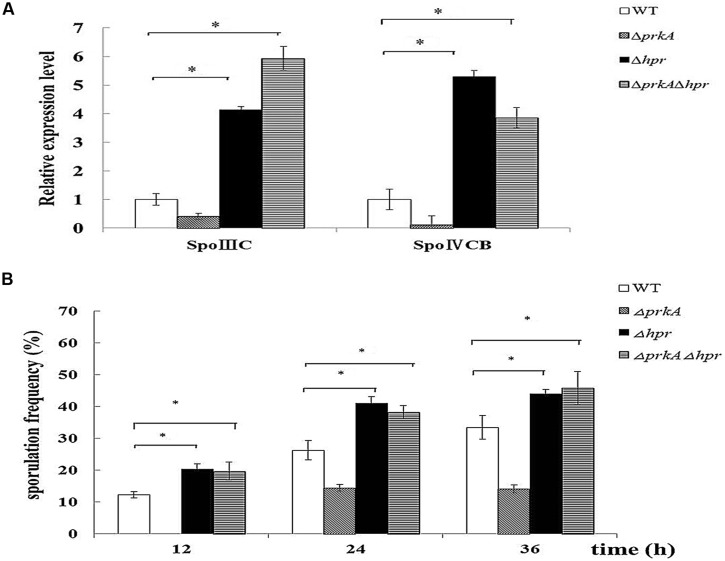

Hpr (ScoC) Functions Epistatic to PrkA in the Spore Development

It was been shown in our β-galactosidase assay that the motif Hpr (ScoC) negatively regulated the expression of sigK in the WT B. subtilis 168. To further confirm such a conclusion, we assessed if the mRNA levels of spoIIIC and spoIVCB were influenced by the gene hpr. In Δhpr mutant, the mRNA levels of both spoIIIC and spoIVCB increased about 4.5-fold compared to the WT B. subtilis 168 (P < 0.01; Figure 6A), suggesting that Hpr indeed negatively controls the expression of sigK. Moreover, we also constructed the double mutant ΔprkAΔhpr and detected the expression of sigK again. It was shown that ΔprkAΔhpr had the similarly higher mRNA levels than the WT (P < 0.01; Figure 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Hpr (ScoC) negatively regulates the expression of sigK in B. subtilis 168, and functions epistatic to PrkA in sporulation. (A) Hpr (ScoC) increases the expression of the transcriptional factor σK. Real-time PCR was employed to detect the relative expression levels of the transcriptional factor σK, which included spoIIIC and spoIVCB. (B) Effect of the gene hpr on sporulation. Sporulation frequencies in WT strain B. subtilis 168, ΔprkA mutant, Δhpr mutant, and ΔprkAΔhpr mutant were determined at 12, 24, 36 h, respectively. ∗P < 0.01.

Then, we examined whether Hpr functioned in the spore development. Our result showed that the sporulation frequencies in Δhpr strain were 20.22 ± 2.02%, 41.04 ± 2.11%, 43.97 ± 0.90% at 12, 24, 36 h, respectively, which were obviously higher than that of the WT strain (12.25 ± 1.01%, 26.24 ± 3.00%, and 33.43 ± 3.72% at these time points; P < 0.01; Figure 6B). Likewise, the double mutant ΔprkAΔhpr had the comparable sporulation frequencies as Δhpr mutant (P> 0.05; Figure 6B). Together, these experiments confirmed that Hpr (ScoC) negatively regulated the expression of sigK in B. subtilis 168, and functioned epistatic to PrkA in the spore development.

Discussion

Under starvation or other environmental stress, Gram-positive bacterium initiates a series of sporulation-related events to generate dormant endospores. The endospores can survive treatments that would otherwise rapidly and efficiently kill other bacterial forms. Such conditions include high temperatures, ionizing radiation, chemical solvents, detergents, and hydrolytic enzymes (Nicholson et al., 2000). Thus, the abilities to form tough, resistant endospores in bacteria have become an important factor in influencing the pathogenesis in pathogenic bacterium or agricultural application in biocontrol agents (Nicholson, 2002; Spencer, 2003). Furthermore, the process of sporulation involves in an unusually mechanism of asymmetric cell division, and attracts much attentions in biological research (Harry, 2001; Ben-Yehuda and Losick, 2002). As a kind of typical pattern of microorganisms, the best-studied paradigm of spore-forming is B. subtilis.

During sporulation in B. subtilis, a strict program of sigma factors activation, including σH, σF, σE, σG, and σK, has been demonstrated as one of the most important events to ensure that sporulation gene expressions occur at the right time and place (Driks, 1999; Errington, 2003). The cascade of those four sigma factors (σF, σE, σG, and σK) is triggered in a sequential order and their biological functions are involved in the engulfment of the smaller cell by the larger sibling, the formation of forespore and the mother cell, and final the assembly of spore coat (Piggot and Hilbert, 2004). Their roles are mainly compartment specific, but also interactional. The sigma factors σF and σG function in the forespores, where the transcription of spoIIIG gene (encoding σG) depends on the RNA polymerase containing σF-subunit. Meanwhile, it has also been suggested that the σE-directed signals from the mother cell are necessary for the formation and activation of σG (Piggot and Hilbert, 2004). The activities of σE and σK are confined within the mother cells, where the synthesis of σK is under the control of σE. But after translation, σK will remain as an inactive precursor in the mother cell until its activation by a proteolysis event, in which the σG -controlled gene spoIVB plays an important role (Wakeley et al., 2000; Campo and Rudner, 2007). Because sporulation itself is a complex multi-gene regulation process, a gene regulatory network should exist to accurately control the expression of sigma factor.

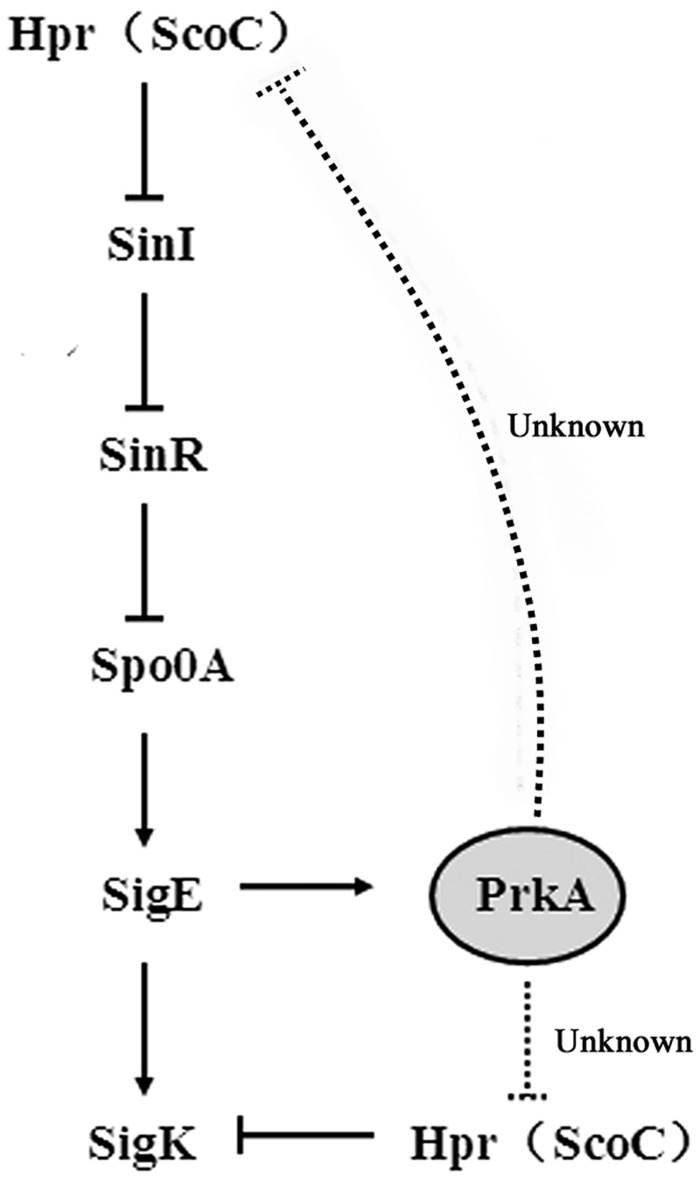

Our current investigation suggested that though the expression of σK was controlled by the well-known sigma factor of σE, PrkA can also negatively regulated Hpr (ScoC) to induce the expression of sigK. In mammalian cells, STPK PrkA belongs to AMPK superfamily, and acts as a master regulator of the main energy metabolism pathway. However, few investigations of PrkA have been reported in prokaryotic cells and thus its function requires further elucidated. Our results here demonstrated that the absence of PrkA significantly reduced the sporulation in B. subtilis 168 that is also consistent with the results previously reported (Eichenberger et al., 2003). The addition of PrkA inhibitor ara-A or the deletion of the gene prkA both showed a similar pattern, confirming the biological function of PrkA as a sporulation-related protein. To analyze the specific stages of sporulation that PrkA influences, the expressional levels of the important sigma factors as well as their downstream genes were assayed using reporter gene of lacZ and qPCR. Our data further suggested that the decreased expression of the transcriptional factor σK and its downstream genes caused by the absence of PrkA were the main reason of reduced sporulation. This hypothesis was confirmed by the complementary expression of sigK in ΔprkA mutant. Combining the results from bioinformatics analysis and reporter gene activity assay, our study revealed that PrkA controls the expression of σK via the transcription factor binding motifs of Hpr (ScoC). Meanwhile, we have also noticed an indirect pathway described in previous literature: Hpr (ScoC) influencing σE expression by negatively regulating SinI, SinR, and Spo0A (Koide et al., 1999; Kodgire and Rao, 2009), and ultimately decreasing σK (Figure 7). In our transcriptional analysis, it consistently illustrated that prkA-P1 strain (ΔprkA mutant with the reporter fusion containing SigE binding motif) had lower β-galactosidase activity than that WT-P1 (WT strain with the reporter fusion containing SigE binding motif; Figure 5).

FIGURE 7.

A proposed model of PrkA regulating the expression of sigK in B. subtilis 168.

Conclusion

Our current investigation confirms the biological role of PrkA in sporulation. In addition, we revealed the underlying mechanism of how PrkA influenced the expression of sigma factor σK by the negative regulation of Hpr (ScoC).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Jianping Xu of McMaster University in Canada and Zhiqiang An of University of Texas Health Science Center for their comments and revisions. This work is supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (grant no. 2011AA10A203 and no. 2013CB127500), the National Natural Science Foundation Program of China (grant no. 31460024).

References

- Av-Gay Y., Everett M. (2000). The eukaryotic-like Ser/Thr protein kinases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 8 238–244 10.1016/S0966842X(00)01734-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakal C. J., Davies J. E. (2000). No longer an exclusive club: eukaryotic signaling domains in bacteria. Trends Cell Biol. 10 32–38 10.1016/S0962-8924(99)01681-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yehuda S., Losick R. (2002). Asymmetric cell division in B. subtilis involves a spiral-like intermediate of the cytokinetic protein FtsZ. Cell 109 257–266 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00698-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campo N., Rudner D. Z. (2007). SpoIVB and CtpB are both signals in the activation of the sporulation transcription factor δK in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 189 6021–6027 10.1128/JB.00399-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole S. T., Brosch R., Parkhill J., Garnier T., Churcher C., Harris D., et al. (1998). Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393 537–544 10.1038/31159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cozzone A. J. (2005). Role of protein phosphorylation on serine/threonine and tyrosine in the virulence of bacterial pathogens. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 9 198–213 10.1159/000089648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutscher J., Saier M. H. (1988). Protein phosphorylation in bacteria-regulation of gene expression, transport functions, and metabolic processes. Angcw. Chem. Int. Ed. 27 1040–1049 10.1002/anie.198810401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Driks A. (1999). Bacillus subtilis spore coat. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichenberger P., Jensen S. T., Conlon E. M., Ooij C., Silvaggi J., Gonzalez-Pastor J. E., et al. (2003). The σE regulon and the identification of additional sporulation genes in Bacillus subtilis. J. Mol. Biol. 327 945–972 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00205-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Errington J. (2003). Regulation of endospore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1 117–126 10.1038/nrmicro750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari R., Henner D. J., Perego M., Hoch J. A. (1988). Transcription of Bacillus subtilis subtilisin and expression of subtilisin in sporulation mutants. J. Bacteriol. 170 298–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer C., Geourjon C., Bourson C., Deutscher J. (1996). Cloning and characterization of the Bacillus subtilis prkA gene encoding a novel serine protein kinase. Gene 168 55–60 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00758-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harry E. J. (2001). Bacterial cell division: regulating Z-ring formation. Mol. Microbiol. 40 795–803 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02370.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert D. W., Piggot P. J. (2004). Compartmentalization of gene expression during Bacillus subtilis spore formation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68 234–262 10.1128/MMBR.68.2.234-262.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodgire P., Rao K. K. (2009). hag expression in Bacillus subtilis is both negatively and positively regulated by ScoC. Microbiology 155 142–149 10.1099/mic.0.021899-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide A., Perego M., Hoch J. A. (1999). ScoC regulates peptide transport and sporulation initiation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 181 4114–4117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristich C. J., Wells C. L., Dunny G. M. (2007). A eukaryotic-type Ser/Thr kinase in Enterococcus faecalismediates antimicrobial resistance and intestinal persistence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 3508–3513 10.1073/pnas.0608742104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroos L., Kunkel B., Losick R. (1989). Switch protein alters specificity of RNA polymerase containing a compartment-specific sigma factor. Science 243 526–529 10.1126/science.2492118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsov J. N., Leclerc G. J., Leclerc G. M., Barredo J. C. (2011). AMPK and Akt determine apoptotic cell death following perturbations of one-carbon metabolism by regulating ER Stress in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mol. Cancer Ther. 10 437–447 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeDeaux B. A., Grossman A. D. (1995). Isolation and characterization of kinC, a gene that encodes a sensor 2. kinase homologous to the sporulation sensor kinases KinB in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 177 166–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leighton T. J., Doi R. H. (1971). The stability of messenger ribonucleic acid during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 252 268–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima A., Durán R., Schujman G. E., Marchissio M. J., Portela M. M., Obal C., et al. (2011). Serine/threonine protein kinase PrkA of the human pathogen Listeria monocytogenes: biochemical characterization and identification of interacting partners through proteomic approaches. J. Proteomics 74 1720–1734 10.1016/j.jprot.201103.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molle V., Kremer L. (2010). Division and cell envelope regulation by Ser/Thr phosphorylation: Mycobacterium shows the way. Mol. Microbiol. 75 1064–1077 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson W. L. (2002). Roles of Bacillus endospores in the environment. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59 410–416 10.1007/s00018-002-8433-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson W. L., Munakata N., Horneck G., Melosh H. J., Setlow P. (2000). Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64 548–572 10.1128/MMBR.64.3.548-572.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsen K., Donat S. (2010). The impact of serine/threonine phosphorylation in Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300 137–141 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osler M. E., Zierath J. R. (2008). Minireview: adenosine 5-monophosphate-activated protein kinase regulation of fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle. Endocrinology 149 935–941 10.1210/en.2007-1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggot P. J., Hilbert D. W. (2004). Sporulation of Bacillus subtilis Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7 579–586 10.1016/j.mib.2004.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reizer J., Romano A. H., Deutscher J. (1993). The role of phosphorylation of HPr, a phosphocarrier protein of the phosphotransferase system, in the regulation of carbon metabolism in Gram-positive bacteria. J. Cell. Biochem. 51 19–24 10.1002/jcb.240510105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spasic M. R., Callaerts P., Norga K. K. (2009). AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) molecular crossroad for metabolic control and survival of neurons. Neuroscientist 15 309–317 10.1177/1073858408327805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer R. C. (2003). Bacillus anthracis. J. Clin. Pathol. 56 182–187 10.1136/jcp.56.3.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steil L., Serrano M., Henriques A. O., Völker U. (2005). Genome-wide analysis of temporally regulated and compartment-specific gene expression in sporulating cells of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 151 399–420 10.1099/mic.0.27493-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeley P., Hoa N. T., Cutting S. (2000). BofC negatively regulates SpoIVB-mediated signaling in the Bacillus subtilis δK-checkpoint. Mol. Microbiol. 36 1415–1424 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01962.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehenkel A., Bellinzoni M., Grana M., Duran R., Villarino A., Fernandez P., et al. (2008). Mycobacterial Ser/Thr protein kinases and phosphatases: physiological roles and therapeutic potential. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1784 193–202 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]